Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vampyrellida

View on Wikipedia

| Vampyrellida | |

|---|---|

| |

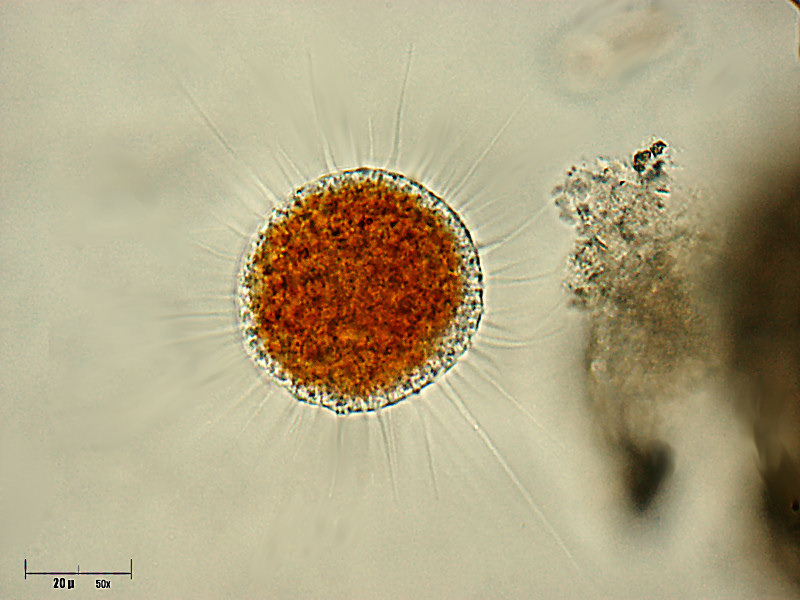

| Vampyrella lateritia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Sar |

| Clade: | Rhizaria |

| Phylum: | Endomyxa |

| Superclass: | Proteomyxia |

| Class: | Vampyrellidea Cavalier-Smith 2018[2] |

| Order: | Vampyrellida West 1901, emend. Hess et al. 2012[1] |

| Clades[3] | |

| Diversity[3] | |

| 48 species | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

|

Aconchulinida De Saedeleer 1934 | |

The vampyrellids (order Vampyrellida, class Vampyrellidea), colloquially known as vampire amoebae, are a group of free-living predatory amoebae classified as part of the lineage Endomyxa. They are distinguished from other groups of amoebae by their irregular cell shape with propensity to fuse and split like plasmodial organisms, and their life cycle with a digestive cyst stage that digests the gathered food. They appear worldwide in marine, brackish, freshwater and soil habitats. They are important predators of an enormous variety of microscopic organisms, from algae to fungi and animals.[3] They are also known as aconchulinid amoebae (order Aconchulinida).[4]

Cell morphology and movement

[edit]Vampyrellids are traditionally considered filose amoebae, i.e. they generate slender pseudopodia (filopodia). They are naked, devoid of external structures such as scales, cell coats or a glycocalyx, although there may be a temporary mucilage coat in the trophozoite stage. The trophozoites vary greatly in shape, size and color between species, but can be grouped into three cell states or 'morphotypes': isodiametric, expanded, and 'filoflabellate'.[1][3]

- Isodiametric (spherical) morphotype, common in algivorous Vampyrella and Lateromyxa, with radiating filopodia. Some species float in the water column, resembling heliozoa in shape. Others crawl on the surface by concentrating stiff filopodia at the anterior region of the cell, attaching them to the surface, retracting and moving them towards the posterior region.[3]

- Expanded morphotype, the most common, bound to the surface, with a variety of shapes (for example, either fan-shaped or branched in Leptophrys; with large, hyaline lamellae with thread-like filopodia in Sericomyxa; highly branched or reticulate, in Platyreta and Thalassomyxa).[3]

- Filoflabellate morphotype, only found in Placopus, with flattened elliptical, spherical or fan-shaped cells that exhibit a clear separation between the granuloplasmic cell hump and the hyaloplasmic lamellae, sometimes called 'lamellipodia'. There are numerous filopodia on the ventral side of the cell. Some of these trophozoites resemble amoebozoans such as vannellids, except for the presence of filopodia. They move by rolling over the filopodia that are anchored to the substrate.[3]

Life cycle

[edit]

Nutrition stages

[edit]All known vampyrellids are heterotrophic amoebae with a free-living (non-parasitic) life cycle that lacks flagellate stages, except for Lateromyxa gallica, and is characterized by an alternation between mobile and immobile cellular stages:[3]

- The mobile, amoeboid cells, called 'trophozoites' or 'swarmers'[a] in old literature. Their main activity is to disperse, search and gather food through phagocytosis.[3]

- The immobile but highly metabolically active 'digestive cyst' stage, that appears after the feeding. In some species it is called a 'resting phase', but it is different from a true resting cyst (or spore) that is metabollically inactive to survive adverse conditions. To reach this stage, the trophozoite retracts its filopodia, secretes a layered cell wall, and strongly attaches itself to the substrate or floats freely. Either a central main vacuole or multiple separate vacuoles appear to digest the food. The cytoplasm color may change to a bright red, orange or yellow color, or remain colorless. When the digestive phase is finished, one or multiple trophozoites hatch from the cyst through holes in the cell wall.[3]

Reproduction

[edit]In some species, near the end of the digestive cyst stage, asexual reproduction takes place inside the cyst through a cell division (called 'internal plasmotomy'), resulting in 2–4 daughter cells. These cells are released as young trophozoites through the holes. Other species do not divide inside the closed cyst, and instead divide during or after the hatching process ('external plasmotomy'). Lateromyxa gallica shows an unusual mode of reproduction: while feeding on the inside of algal cells, the plasmodia shed and develop into digestive cysts.[3]

There is a lack of evidence for sexual reproduction in vampyrellids, except for some meiotic stages in resting cysts revealed in Lateromyxa gallica through ultrastructural studies.[5]

Plasmodial behavior

[edit]Many vampyrellid species have more than one nucleus and behave like plasmodia. They can fuse their cells upon contact, and split apart when moving in opposite directions. Some species readily grow plasmodia as large as a Petri dish under laboratory conditions, while others only fuse when the cell density is high and the food availability is low. It is uncertain to what extend this can happen in the natural environment. In contrast, Placopus species are rarely ever seen with more than two nuclei.[3]

Resting stages

[edit]Under adverse environmental conditions, vampyrellids can transform into several types of resting stages:[3]

- Hypnocysts, thin-walled and devoid of food content, formed when the trophozoite is disturbed by external stress.[3]

- Secondary cysts, thin-walled and devoid of food content, formed as a result of starvation.[3]

- True resting cysts, also called 'sporocysts' or 'spores' in old literature. They form in natural samples and old cultures, when there is no food or the conditions are unfavorable. They build several cyst walls and condense their cellular contents. They can survive events of desiccation or freezing, up to at least three years.[3]

Ecology

[edit]Distribution

[edit]Vampyrellids have a cosmopolitan distribution: they appear in all continents except Antarctica and all marine ecosystems. They inhabit a wide range of marine, brackish and freshwater habitats, and are frequently isolated from soil samples.[3] Marine ecosystems hold a surprisingly high diversity,[6] and they are found mostly in benthic habitats (e.g. tidal pools, diatom lawns, associated with red algae...). There is a significant positive correlation between the diversity of Vampyrellida and the nutrient availability in the sediment.[7] According to environmental sequencing vampyrellids colonize neotropical soil,[8] glacial cryoconite systems,[9] Brassicaceae leaves,[10] Sphagnum-inhabited peat bogs,[11] hydrothermal sediments[6] and the deep sea.[12]

Trophic diversity

[edit]

Vampyrellids display a great trophic diversity. They are predators of a long list of organisms of diverse evolutionary affinities, structures and sizes, including chlorophyte and streptophyte green algae, diatoms, chrysophytes, cryptophytes, euglenids, heterotrophic flagellates, ciliate cysts, fungal hyphae and spores, yeasts, and even micrometazoa such as nematodes and rotifer eggs. Bacterivory is rare and mostly involves filamentous cyanobacteria. Though there are generalist omnivorous predators such as Leptophrys, some vampyrellid species are specialized predators; for example, the algivorous Vampyrella and Placopus are restricted to few species of hard-walled green algae, while Arachnomyxa and Planctomyxa prefer Volvocales and euglenids.[3]

Feeding strategies

[edit]

Vampyrellids have evolved strategies to deal with relatively large bulky prey that are difficult to consume. They display at least four different feeding strategies to engulf entire prey or to devour the contents of other eukaryotic cells. These feeding strategies are not mutually exclusive, and the same species can display each with a different type of prey.[3]

- Free capture. Similarly to amoebae of other supergroups, they catch and enclose their prey within a food vacuole by usual phagocytosis. Some can paralyse their prey before the enclosement. The size of the enveloping is widely varied, from numerous small cells at the same time to entire nematodes or colonial green algae.[3]

- Colony invasion. They attach to the colonies of volvocalean algae, dissolve and penetrate the extracellular gelatinous mucilage matrix, and phagocytose individual cells inside the colony. Possibly for protection against predators, they transform into digestive cysts inside of the colony.[3]

- Protoplast extraction, the most famous strategy. They specifically remove, ingest and digest the cellular contents of their prey, always by dissolving the prey's organic cell wall or simply displacing the prey's siliceous wall, and invading through pseudopodia (called 'calyculopodia') to remove the cell contents . Some species eject the prey cytoplasm by applying pressure, a process known as 'plasmoptysis', which is followed by a rapid formation of a large vacuole. This process resembles a sucking motion, and is likely the reason for their comparison to vampires. In marine species no plasmoptysis is observed, which suggests that the osmotic pressure given by salinity is important for plasmoptysis.[3]

- Prey infiltration. Similarly to protoplast extractors, they perforate the cell wall of an algal prey, but invade the cell itself and completes the cycle within it. Some are able to move laterally from one cell to the next in filamentous prey. They divide into smaller portions that turn into digestive cysts.[3]

History of research

[edit]

Vampyrellids have a long history of research. They are known for the vampire-like feeding habit of several vampyrellid amoebae, which pierce the cell walls of other eukaryotic cells to feed specifically on the cell contents, a feeding mechanism known as protoplast extraction. This similarity lead to the origin of the name for their most popular genus, Vampyrella, and their colloquial name 'vampire amoebae'.[3]

One of the earliest unambiguous reports of a vampyrellid is the mid-19th century description of Amoeba lateritia (now known as Vampyrella lateritia) by the German botanist Georg Fresenius.[13] The first extensive documentation of their life history and feeding behavior was provided in 1865 by the Polish protozoologist Leon Cienkowski, who created the genus Vampyrella and classified it in a subgroup of the 'monads',[14] a polyphyletic assemblage of parasitoid protists. Posterior works and monographs described numerous aquatic vampyrellid species, with important observations of their behaviour and ecology. In 1885, the German mycologist Wilhelm Zopf demonstrated the presence of nuclei in vampyrellids and erected the first family, Vampyrellidae.[15][16][3]

In the mid-20th century the first discoveries of soil-dwelling Vampyrellida were made. The first vampyrellid laboratory culture was established, containing the soil amoeba Theratomyxa weberi that fed on nematodes. Similar soil amoebae were isolated later, and studied as possible pest control against plant-pathogenic nematodes.[17] Other studies identified a giant soil vampyrellid as the organism responsible for perforations found in fungal spores.[18][3]

In the early 1980s the feeding process and life cycle of the algivorous freshwater Vampyrella lateritia was filmed in unsurpassed detail.[19][20] At the same time, the genus of large, plasmodial amoebae Thalassomyxa, was discovered in marine waters from remote parts of the world.[21]

Before genetic analyses, the taxonomic placement of vampyrellids was difficult: they were regarded as relatives of myxomycete slime moulds,[16] heliozoa,[22] proteomyxids,[23] filose rhizopods[24] and even monera.[25] In 2009 the mystery was solved through phylogenies of 18S ribosomal RNA genes, which placed vampyrellids as part of Rhizaria.[26] A revised taxonomy in 2012 reconstituted the order Vampyrellida.[1] In 2013, a huge unexpected diversity of marine vampyrellids was detected.[6][3]

Evolution and systematics

[edit]External relationships

[edit]Vampyrellida represents one of the major groups of free-living amoebae, phylogenetically separate from other groups of amoebae such as Amoebozoa, Heterolobosea and Nucleariidae. Instead, Vampyrellida is an isolated clade within the Rhizaria supergroup.[26] They are the closest relatives of the Phytomyxea, parasites of plants and algae that, unlike vampyrellids, disperse through flagellated stages during their life cycle and spend most of their active life within host cells.[3] Current classifications place both Vampyrellida and Phytomyxea, along with other small groups of Rhizaria, within the phylum Endomyxa.[4] Several phylogenetic analyses have recovered a sister group relationship between Vampyrellida and Phytomyxea and have named their clade Proteomyxia[2] or Phytorhiza.[27]

Internal classification

[edit]| Vampyrellid phylogeny | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny of Vampyrellida published in 2023, inferred from SSU rRNA gene sequences.[28] The lineages B1, B2 and B4 are clades that contain only environmental DNA sequences, with no described species.[3] |

There are currently 48 credible vampyrellid species distributed in 10 genera, scattered across five well-established clades found through genetic data, four of which are families. Despite the advances, most of the vampyrellid diversity is still unknown or undescribed.[3]

- Family Vampyrellidae Zopf 1885 emend. Hess, Sausen et Melkonian 2012[1]

- Vampyrella Cienkowski 1865 (19 species)

- Family Leptophryidae Hess, Sausen & Melkonian 2012[1]

- Arachnomyxa Hess 2017 (1 species)

- Leptophrys Hertwig & Lesser 1874 (3 species)

- Planctomyxa Hess 2017 (1 species)

- Platyreta Cavalier-Smith & Bass 2008 (1 species)

- Pseudovampyrella Suthaus & Hess 2023 (2 species)[28]

- Theratromyxa Zwillenberg 1952 (1 species)

- Vernalophrys Gong et al. 2015 (1 species)

- Family Placopodidae Jahn 1928 = Hyalodiscidae Poche 1913 = lineage B3

- Family Sericomyxidae More, Simpson & Hess 2021

- Sericomyxa More, Simpson & Hess 2021 (1 species)

- 'Thalassomyxa clade' = lineage B5

- Thalassomyxa Grell 1985 (3 species)

- Genera that likely belong to Vampyrellida but for which there is no genetic data, and are thus considered incertae sedis:

- Arachnula Cienkowski 1856 (2 species)

- Asterocaelum Canter 1973 (1 species)

- Gobiella Cienkowski 1881 (2 species)

- Lateromyxa Hülsmann 1993 (1 species)

- Monadopsis Klein 1993 (1 species)

- Penardia Cash 1904 (2 species)

The following taxa have been associated with Vampyrellida, but their placement is uncertain or might not belong to the group.[3]

- Hyalodiscus angelovica Sawyer 1975

- Hyalodiscus caeruleus Schaeffer 1926

- Hyalodiscus foliaceus Lepsi 1931

- Hyalodiscus korotnewi Mereschovsky 1879

- Hyalodiscus macronucleus Lepsi 1931

- Hyalodiscus minimus Lepsi 1960

- Hyalodiscus placopus Hülssmann 1974 [not Paragocevia placopus (Page & Willumsen 1980) Page 1987]

- Hyalodiscus simplex Wohlfarth-Bottermann 1977

- Vampyrella chaetoceratis (Paulsen 1910) Ostenfeld 1913 [Apodinium chaetoceratis Paulsen 1910; Paulsenella chaetoceratis (Paulsen 1910) Chatton 1920]

- Vampyrella labyrinthuloides (Archer 1875) Valkanov 1940 [Chlamydomyxa labyrinthuloides Archer 1875]

- Vampyrella montana (Lankester 1896) Valkanov 1940 [Chlamydomyxa montana Lankester 1896]

- Vampyrellidium perforans Surek & Melkonian 1980 (nucleariid amoeba)

- Vampyrellidium vagans Zopf 1885 (nucleariid amoeba)

- Vampyrellidium roseus (Trichense 1885) Schepotieff 1912 [Protogenes roseus Trichense 1885]

- Vampyrina buetschlii Frenzel 1897

Notes

[edit]- ^ The term 'swarmers' is more specially used for ciliated, swimming cells such as gametes, so trophozoites is a more appropriate term.[3]

- ^ Not to be confused with the diatom genus Hyalodiscus Ehrenberg 1845, which takes preference in the biological nomenclature for being described earlier.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Hess S, Sausen N, Melkonian M (2012). "Shedding light on vampires: the phylogeny of vampyrellid amoebae revisited". PLOS ONE. 7 (2) e31165. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731165H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031165. PMC 3280292. PMID 22355342.

- ^ a b Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; E. Chao, Ema; Lewis, Rhodri (2018), "Multigene phylogeny and cell evolution of chromist infrakingdom Rhizaria: contrasting cell organisation of sister phyla Cercozoa and Retaria", Protoplasma, 255 (5): 1517–1574, doi:10.1007/s00709-018-1241-1, PMC 6133090, PMID 29666938

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Hess S, Suthaus A (2022). "The Vampyrellid Amoebae (Vampyrellida, Rhizaria)". Protist. 173 (1) 125854. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2021.125854. PMID 35091168.

- ^ a b c Adl SM, Bass D, Lane CE, Lukeš J, Schoch CL, Smirnov A, Agatha S, Berney C, Brown MW, Burki F, Cárdenas P, Čepička I, Chistyakova L, del Campo J, Dunthorn M, Edvardsen B, Eglit Y, Guillou L, Hampl V, Heiss AA, Hoppenrath M, James TY, Karnkowska A, Karpov S, Kim E, Kolisko M, Kudryavtsev A, Lahr DJG, Lara E, Le Gall L, Lynn DH, Mann DG, Massana R, Mitchell EAD, Morrow C, Park JS, Pawlowski JW, Powell MJ, Richter DJ, Rueckert S, Shadwick L, Shimano S, Spiegel FW, Torruella G, Youssef N, Zlatogursky V, Zhang Q (2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Röpstorf P, Hülsmann N, Hausmann K (1993). "Karyological investigations on the vampyrellid filose amoeba Lateromyxa gallica Hülsmann 1993". European Journal of Protistology. 29 (3): 302–310. doi:10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80373-1. PMID 23195644.

- ^ a b c Berney C, Romac S, Mahé F, Santini S, Siano R, Bass D (2013). "Vampires in the oceans: predatory cercozoan amoebae in marine habitats". ISME J. 7 (12): 2387–2399. doi:10.1038/ismej.2013.116. PMC 3834849. PMID 23864128.

- ^ Song H, Zhang Y, Leng X, Zhang Y, Yu Y (2015). "Aconchulinid testate amoebae play an important role in nutrient cycling in freshwater ecosystems". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 82: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.11.009.

- ^ Lentendu G, Mahé F, Bass D, Rueckert S, Stoeck T, Dunthorn M (2018). "Consistent patterns of high alpha and low beta diversity in tropical parasitic and free-living protists". Molecular Ecology. 27 (13): 2846–2857. doi:10.1111/mec.14731. PMID 29851187. S2CID 44119381.

- ^ Vimercati L, Darcy JL, Schmidt SK (2019). "The disappearing periglacial ecosystem atop Mt. Kilimanjaro supports both cosmopolitan and endemic microbial communities". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 10676. Bibcode:2019NatSR...910676V. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46521-0. PMC 6650471. PMID 31337772.

- ^ Ploch S, Rose LE, Bass D, Bonkowski M (2016). "High Diversity Revealed in Leaf-Associated Protists (Rhizaria: Cercozoa) of Brassicaceae". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 63 (5): 635–641. doi:10.1111/jeu.12314. PMC 5031217. PMID 27005328.

- ^ Lara E, Mitchell EAD, Moreira D, García PL (2011). "Highly Diverse and Seasonally Dynamic Protist Community in a Pristine Peat Bog" (PDF). Protist. 162 (1): 14–32. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2010.05.003. PMID 20692868.

- ^ Schoenle A, Hohlfeld M, Hermanns K, Mahé F, de Vargas C, Nitsche F, Arndt H (2021). "High and specific diversity of protists in the deep-sea basins dominated by diplonemids, kinetoplastids, ciliates and foraminiferans". Communications Biology. 4 (1): 501. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02012-5. PMC 8065057. PMID 33893386.

- ^ Fresenius, Georg (1858). "Beiträge zur Kenntniss mikroskopischer Organismen" [Contributions to the Knowledge of microscopic Organisms]. Abhandlungen der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft (in German). 2: 218–219, 241–242.

- ^ Cienkowski, Lev (1865). "Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Monaden" [Contributions to the Knowledge of the Monads]. Archiv für mikroskopische Anatomie (in German). 1: 203–232. doi:10.1007/BF02961414. S2CID 84323025.

- ^ Zopf W (1885). "Die Pilzthiere oder Schleimpilze" [The Fungal Animals or Slime Molds]. In Schenk A (ed.). Handbuch der Botanik (Encyklopädie der Naturwissenschaften) [Handbook of Botany (Encyclopedia of Natural Sciences)] (in German). Vol. 3. Trewendt, Breslau. pp. 1–174.

- ^ a b Zopf W (1885). Zur Morphologie und Biologie der niederen Pilzthiere (Monadinen), zugleich ein Beitrag zur Phytopathologie [On the Morphology and Biology of the lower Fungal Animals (Monadins), simultaneously a Contribution to Phytopathology] (in German). Leipzig: Veit and Comp. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.945.

- ^ Winslow RD, Williams TD (1957). "Amoeboid organisms attacking larvae of the potato root eelworm (Heterodera rostochiensis Woll.) in England and the beet eelworm (H. schachtii Schm.) in Canada". Tijdschrift over Plantenziekten. 63 (5): 242–243. doi:10.1007/BF01988794. S2CID 21473045.

- ^ Old KM, Darbyshire JF (1978). "Soil fungi as food for giant amoebae". Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 10 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(78)90077-9.

- ^ Hülsmann N (1983). "On the penetration of algal cell walls during the attacks by vampyrellids". Journal of Protozoology. 30: A50.

- ^ Hülsmann N (1985). "Entwicklung und Ernährungsweise von Vampyrella lateritia (Rhizopoda)" [Development and feeding habits of Vampyrella lateritia (Rhizopoda)]. Publ. Wiss. Film, Sekt. Biol., Ser. 17, Nr. 16/C. 17: 1–23.

- ^ Grell KG (1994). "Thalassomyxa canariensis n. sp. from a tide pool of Tenerife (Canary Islands)". Arch Protistenkd. 144 (3): 319–324. doi:10.1016/S0003-9365(11)80146-6.

- ^ Loeblich AR, Loeblich LA. "Nomenclature and taxonomic position of Pseudosporidae, Vampyrellidae and Acinetactidae". Proc Biol Soc Wash. 78: 115–120.

- ^ Honigberg BM, Balamuth W, Bovee EC, Corliss JO, Gojdics M, Hall RP, Kudo RR, Levine ND, Loeblich AR, Weiser J, Wenrich DH (1964). "A Revised Classification of the Phylum Protozoa". Journal of Protozoology. 11 (1): 7–20. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1964.tb01715.x. PMID 14119564.

- ^ Page FC (1987). "The classification of 'naked' amoebae (Phylum Rhizopoda)". Archiv für Protistenkunde. 133 (3–4): 199–217. doi:10.1016/S0003-9365(87)80053-2.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1869). "Studien über Moneren und andere Protisten, nebst einer Rede über Entwicklungsgang und Aufgabe der Zoologie" [Studies on Monera and other Protists, together with a Speech on the course of Development and the Function of zoology]. Jenaische Zeitschrift (in German). 5. Leipzig: Engelmann: 353.

- ^ a b Bass D, Chao EE, Nikolaev S, Yabuki A, Ishida KI, Berney C, Pakzad U, Wylezich C, Cavalier-Smith T (2009). "Phylogeny of Novel Naked Filose and Reticulose Cercozoa: Granofilosea cl. n. and Proteomyxidea Revised". Protist. 160 (1): 75–109. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2008.07.002. ISSN 1434-4610. PMID 18952499.

- ^ Sierra R, Cañas-Duarte SJ, Burki F, Schwelm A, Fogelqvist J, Dixelius C, González-García LN, Gile GH, Slamovits CH, Klopp C, Restrepo S, Arzul I, Pawlowski J (April 2016). "Evolutionary Origins of Rhizarian Parasites". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 33 (4): 980–983. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv340. PMID 26681153.

- ^ a b Suthaus A, Hess S (2023). "Pseudovampyrella gen. nov.: A genus of Vampyrella-like protoplast extractors finds its place in the Leptophryidae". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 00 e13002. International Society of Protistologists. doi:10.1111/jeu.13002.