Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

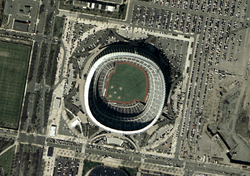

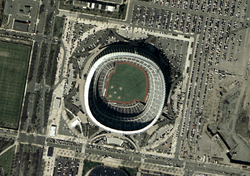

Veterans Stadium

View on Wikipedia

Veterans Stadium was a multi-purpose stadium in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, at the northeast corner of Broad Street and Pattison Avenue, part of the South Philadelphia Sports Complex. The seating capacities were 65,358 for football, and 56,371 for baseball.

Key Information

It hosted the Philadelphia Phillies of Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1971 to 2003 and the Philadelphia Eagles of the National Football League (NFL) from 1971 to 2002. The 1976 and 1996 Major League Baseball All-Star Games were held at the venue. It also hosted the annual Army-Navy football game between 1980 and 2001.

In addition to professional baseball and football, the stadium hosted other amateur and professional sports, large entertainment events, and other civic affairs. It was demolished by implosion in March 2004, being replaced by the adjacent Citizens Bank Park and Lincoln Financial Field. A parking lot now sits on its former site.

History

[edit]Plans and construction

[edit]

In 1959, Phillies owner R. R. M. Carpenter Jr. proposed building a new ballpark for the Philadelphia Phillies on 72 acres (290,000 m2) adjacent to the Garden State Park Racetrack in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. The Phillies' were playing at Connie Mack Stadium, a stadium built in 1909 that was beginning to show its age. Connie Mack Stadium also had inadequate parking, and was located in a declining section of the city. The same year, alcohol sales at sporting events were banned in Pennsylvania but were still legal across the Delaware River in neighboring South Jersey.

The stadium proposed by Carpenter would have seated 45,000 fans but would be expandable to 60,000, and would have 15,000 parking spaces.[4]

The American League's Philadelphia Athletics moved to Kansas City following the 1954 season, while the NBA's Philadelphia Warriors moved to San Francisco to become the Golden State Warriors in 1962, and Philadelphians were not going to allow losing another professional sports franchise.

Financing

[edit]In 1964, Philadelphia voters approved a US$25-million-bond issue for a new stadium to serve as the home of both the Eagles, who played at the University of Pennsylvania's Franklin Field, and the Phillies. Because of cost overruns, the voters had to go to the polls again in 1967 to approve another $13 million. At a total cost of $60 million[clarification needed], it was at the time one of the most expensive stadiums ever constructed.[5]

Naming

[edit]In 1968, the Philadelphia City Council named the stadium Veterans Stadium in honor of veterans. In December 1969, the Phillies announced that they anticipated that they would play the first month of the 1970 season at Connie Mack Stadium before moving to the new venue.[6] However, the opening was delayed a year because of a combination of bad weather and cost overruns.

Structure and design

[edit]The stadium's design was nearly circular, and was known as an octorad design, which attempted to facilitate both football and baseball. San Diego Stadium in San Diego had been similarly designed. As was the case with other cities where this dual approach was used, such as RFK Stadium in Washington, D.C., Shea Stadium in New York City, the Astrodome in Houston, Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium in Atlanta, Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, and Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, the fundamentally different sizes and shapes of the playing fields made the stadium inadequate to the needs of either sport.

Opening

[edit]The stadium opened with a $3 million scoreboard complex that at the time was the most expensive ever installed.[7]

Prior to its opening, the stadium was blessed by Marine Corps chaplain veteran Francis "Father Foxhole" Kelly.[8]

Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]The Philadelphia Phillies played their first game at the stadium on April 10, 1971, beating the Montreal Expos, 4–1, before an audience of 55,352. The first ball was dropped by helicopter to Phillies back-up catcher Mike Ryan.[7]

Jim Bunning, who was named to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1996, was the winning pitcher, and Bill Stoneman of the Expos took the loss. Entertainer Mike Douglas, whose daily talk show was taped in Philadelphia, sang "The Star-Spangled Banner" before the game. The emcee for the opening ceremonies was Harry Kalas, the new Phillies play-by-play announcer.

Boots Day opened the game by grounding out to Bunning. Larry Bowa had the stadium's first hit, and Don Money hit the first home run in the stadium.[9]

Philadelphia Eagles

[edit]On September 26, 1971, the Philadelphia Eagles played their first game at Veterans Stadium, hosting the Dallas Cowboys in a game the Eagles lost 42–7. The first Eagles touchdown at the stadium, and the Eagles only points during the game, came from Al Nelson's then-record 102-yard return of a missed field goal by Mike Clark in the fourth quarter.[10]

Stadium deterioriation

[edit]As the stadium aged, its condition deteriorated. A hole in the wall allowed visiting teams' players to peep into the dressing room of the Eagles Cheerleaders.[11] So many mice infested the stadium that the security force employed cats as mousers.[12]

Final games

[edit]Philadelphia Eagles

[edit]The final Eagles game played at Veterans Stadium was the Eagles' 27–10 loss to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in the 2002 NFC Championship Game on January 19, 2003. The Eagles moved into Lincoln Financial Field in August 2003.[13]

Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]The final game ever played at the stadium was the afternoon of September 28, 2003, a 5–2 Phillies loss to the Atlanta Braves.[14]

The final win at the stadium was recorded by Greg Maddux of the Braves; the final loss at the stadium was recorded by the Phillies' Kevin Millwood. The final Phillies run was scored by Marlon Byrd in the bottom of the 3rd inning, and the final run altogether by the Braves' Andruw Jones on a double by Robert Fick, who also had the last hit at Tiger Stadium while with the Detroit Tigers four years earlier in the top of the 5th.

The final hit at Veterans Stadium was a single by the Phillies' Pat Burrell in the bottom of the 9th inning. The next batter, Chase Utley, grounded into a double play to end the game and Veterans Stadium. A ceremony at Veterans Stadium following the final Phillies game at the stadium pulled at the heartstrings of the sellout crowd. Paul Owens, a former Phillies general manager, and Tug McGraw, a former Phillies pitcher, made their final public appearances at the park that day; both men died that winter.[15][16]

The last publicly broadcast words uttered at Veterans Stadium came from Harry Kalas, who helped open the facility on April 10, 1971, who paraphrased his trademark home run call: "It's on a looooooong drive…IT'S OUTTA HERE!!!"

The following seasons, the Phillies played their first game at the newly constructed Citizens Bank Park on April 12, 2004.

Demolition and commemoration

[edit]On March 21, 2004, the 32-year-old stadium was imploded in 62 seconds. Frank Bardonaro, President of Philadelphia-based AmQuip Crane Rental Company, pressed the "charge" button and then he and Nicholas T Peetros Sr., Project Manager for Driscoll/Hunt Construction Company, pressed the "fire" button to trigger the implosion[17] while Greg Luzinski and the Phillie Phanatic, the Phillies' mascot, pressed a ceremonial plunger for the fans, which did not set off any explosives.[18] A parking lot for the current sporting facilities was constructed in 2004 and 2005 at the site.

On June 6, 2005, the anniversary of World War II's D-Day, a plaque and monument to commemorate the spot where the stadium stood and a memorial for all veterans was dedicated by the Phillies before their game against the Arizona Diamondbacks. On September 28, 2005, the second anniversary of the stadium's final game, a historical marker commemorating where the ballpark once stood was dedicated. In April 2006, granite spaces marking the former locations of home plate, the pitcher's mound, and the three bases for baseball, as well as the goalpost placements for football, were added in Citizens Bank Park's Western Parking Lot U.

Before the stadium's implosion, The Vet's Liberty Bell replica was removed from its perch and placed in storage. In 2019, the bell was installed outside the third base entrance of Citizens Bank Park.

Health concerns

[edit]In the years following demolition, an apparent cancer cluster has emerged among several former Phillies players who played at Veterans Stadium who later developed glioblastoma, a form of brain cancer.[19] Six former Phillies who played while the team called Veterans Stadium home have died of the cancer.[20]

According to a 2013 analysis by The Philadelphia Inquirer, the brain cancer rate of Phillies players while the team was at Veterans Stadium was three times higher than that of the general population.[21] Some of the speculation centers around the possibility that chemicals in the stadium's AstroTurf field may have played a role, but there has been no research to support that theory definitively.[21]

Seating capacity

[edit]

|

|

Stadium features

[edit]

The stadium was a complicated structure with its seating layered in seven separate levels in its final configuration. The lowest, or "100 Level", extended only part way around the structure, between roughly the 25-yard lines for football games and near the two dugouts for baseball. The "200 Level" comprised field-level boxes, and the "300 Level" housed what were labeled "Terrace Boxes". These three levels collectively made up the "Lower Stands". The "400 Level" was reserved for the press and dignitaries; the upper level began with "500 Level" (or "loge boxes"), the "600 Level" (upper reserved, or individual seats), and finally, the highest, the "700 Level" (general admission for baseball). Originally, the seats were in shades of brown, terra cotta, orange and yellow, to look like an autumn day, but in 1995 and 1996, blue seats replaced the fall-hued ones.

At one time, the stadium could seat over 71,000 people for football, but restructuring in the late 1980s—including removal of several rows of the 700 Level around most of the stadium to accommodate construction of the Penthouse Suites—brought capacity down to around 66,000.

The stadium was harshly criticized by baseball purists. Even by multipurpose stadium standards, the upper deck was exceptionally high, and many of the seats in that area were so far from the field that it was difficult to see the game without binoculars. Like most of its contemporaries, foul territory was quite roomy. Approximately 70% of the seats were in fair territory, adding to the stadium's cavernous feel. There was no dirt in the infield except for sliding pits around the bases, and circular areas around the pitcher's mound and home plate. In the autumn, the football markings were clearly visible in the spacious outfield area. While the stadium's size enabled the Phillies to shatter previous attendance records, during the years the Phillies were not doing as well, even crowds of 35,000 looked sparse.

The stadium had been known for providing both the Eagles and the Phillies with great home-field advantage. In particular, the acoustics greatly enhanced the crowd noise on the field, making it nearly impossible for opposing players to hear one another.

In his book The Secret Apartment, author Tom Garvey, who managed parking for the stadium, recalls how he spent two years residing in a space at the stadium where he was storing furniture for Eagles tight end Richard Osborne.[22]

700 Level

[edit]The "700 Level", the highest and cheapest seats at Veterans Stadium, became well known for being home to the loudest, rowdiest fans at Philadelphia Eagles games, and to a lesser extent, Philadelphia Phillies games. In his book If Football's a Religion, Why Don't We Have a Prayer?,[23] Jereé Longman described the 700 Level as having a reputation for "hostile taunting, fighting, public urination and general strangeness." Due to an improvement in public facilities, there is no equivalent in either the current Lincoln Financial Field or Citizens Bank Park. The name has also been the inspiration for websites relating to Philadelphia sports, as well as a weekly "Letters to the Editor" section in the Sunday Sports pages of The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Playing surface

[edit]

The field's surface, originally composed of AstroTurf, contained many gaps and uneven patches. In several places, seams were clearly visible, giving it the nickname "Field of Seams". It perennially drew the ranking of the "NFL's worst field" in player surveys conducted by the NFL Players Association (NFLPA), and visiting players often fell prey to the treacherous conditions resulting in numerous contact and non-contact injuries.[24] The NFLPA reportedly threatened to sue the city for the poor conditions, and many sports agents told the Eagles not to even consider signing or drafting their clients. The Eagles, for their part, complained to the city on numerous occasions about the conditions at the stadium. Baseball players also complained about the surface. It was much harder than other AstroTurf surfaces, and the shock of running on it often caused back pain.

Two of the most-publicized injuries blamed on the playing surface occurred exactly six years apart. On October 10, 1993, Chicago Bears wide receiver Wendell Davis had his cleats caught in a seam while he planted to jump for an underthrown bomb from QB Jim Harbaugh, tearing both of his patella tendons and ending his career, barring a short-lived comeback attempt with the Indianapolis Colts in 1995.[25] On October 10, 1999, Dallas Cowboys wide receiver Michael Irvin suffered a neck injury against the Eagles at Veterans Stadium that proved to be his final play in the NFL and led to his premature retirement.

Long before Davis' and Irvin's injuries, Cleveland Browns standout defensive tackle Jerry Sherk contracted a near-fatal staph infection from the Veterans Stadium turf during a 1979 game. The infection forced him to miss 22 of the Browns' next 23 games and ended a run of nine and a half seasons in the Browns' starting lineup. Sherk never started again and retired in 1981.

In 2001, the original AstroTurf was eventually replaced by a new surface, NexTurf. It was far softer, and reportedly much easier on the knees.[26] However, the city crew that installed the new turf reportedly did not install it properly, resulting in seams being visible in several places.

The first football game on the new turf was scheduled to take place on August 13, 2001, when the Eagles were to play the Baltimore Ravens in a preseason game. However, Ravens coach Brian Billick refused to let the Ravens take the field for warm-ups when he discovered a trench around an area where third base was covered up by a NexTurf cutout. City crews unsuccessfully tried to fix the problem, forcing the game to be canceled. Later, players from both teams reported that they sank into the turf in locations near the infield cutouts. The Eagles' team president Joe Banner was irate after the game, calling the stadium's conditions "absolutely unacceptable" and "an embarrassment to the city of Philadelphia."[27] City officials, however, promised that the stadium would be suitable for play when the regular season started.

The problem was caused by heavy rain over the weekend prior to the game, which made the dirt in the sliding pits and pitcher's mound so soft that the cutouts covering them in the football configuration became mushy and uneven. Even when new dirt was shoveled on top, it quickly became just as saturated as the old dirt. The problem was solved by using asphalt hot mix, which allowed for a solid, level playing surface, but required a jackhammer for removal whenever the stadium was converted from football back to baseball (between August and October of each year).

In March 2023, investigative reporters from the Philadelphia Inquirer bought souvenir samples of the old Veterans Stadium AstroTurf used from 1977 to 1981 and commissioned diagnostics through the Eurofins Environmental Testing laboratory. The resulting lab report linked per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS, also known as "forever chemicals") to the turf. Six former Phillies who played at Veterans Stadium have died from glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer: Tug McGraw, Darren Daulton, John Vukovich, Johnny Oates, Ken Brett, and David West.[28]

Fans

[edit]

Fans who attended games at Veterans Stadium, especially for Philadelphia Eagles games, gained a reputation of being among the most vociferous in all of professional sports, especially in the notorious 700 Level, the highest seating level at Veterans Stadium prior to the construction of luxury skyboxes behind that seating area. The stadium became famous for the exuberant rowdiness of Eagles fans.

One of the more well-known examples of the fans' behavior was during the 1989 season at a follow-up game to what many called the "Bounty Bowl". On Thanksgiving day, November 23, 1989, the Eagles had defeated the Dallas Cowboys at Texas Stadium, 27–0.[29] In that game, Cowboys placekicker Luis Zendejas suffered a concussion during a rough block by linebacker Jessie Small after a kickoff. After the game, Cowboys rookie head coach Jimmy Johnson commented that Eagles head coach Buddy Ryan instituted a bounty on Zendejas and Cowboys quarterback Troy Aikman. Two weeks later, on December 10, they played the rematch dubbed "Bounty Bowl II" at the stadium which the Eagles won 20–10.[30] The stadium seats were covered with snow in the stands. The volatile mix of beer, the "bounty" and the intense hatred for "America's Team" (who finished 1–15 that season) led to fans throwing snowballs at Dallas players and coaches.[31] Beer sales were banned after that incident for two games. A similar incident in 1995 at Giants Stadium during a nationally telecast San Diego Chargers–New York Giants game[32] led the NFL to rule that seating areas must be cleared of snow within a certain time period before kickoff.

The Eagles fans' behavior during a 24–12 Monday Night Football loss[33] to the San Francisco 49ers in 1997 and a 34–0 loss to Dallas a year later[34] was such that the City of Philadelphia assigned a Municipal Court Judge, Seamus McCaffery, to the stadium on game days to deal with fans removed from the stands in what was referred to as "Eagles Court". Judge McCaffery would hold court in the stadium until the stadium's closure in 2003; the Eagles' replacement stadium, Lincoln Financial Field, does not have a court, but a holding cell instead.[35][12] Two years later, fans threw D-Cell batteries at St. Louis Cardinals outfielder J. D. Drew after he spurned the Phillies' offer to play with them, and wound up going back into the draft and picked by the Cardinals.[36]

Notable games and incidents

[edit]- On June 25, 1971, Willie Stargell of the Pittsburgh Pirates hit the longest home run in stadium history in a 14–4 Pirates win over the Phillies.[37] The spot where the ball landed was marked with a yellow star with a black "S" inside a white circle until Stargell's 2001 death, when the white circle was painted black.[38][39] The star remained until the stadium's 2004 demolition.

- One of the most notable events in the stadium's history was Game 6 of the 1980 World Series on October 21. In the game, the Phillies clinched their first world championship with a 4–1 victory over the Kansas City Royals in front of 65,838 fans. Tug McGraw's series-ending strikeout of the Royals' Willie Wilson was instrumental in their win.

- One of the most notable Eagles games at the stadium, which occurred less than three months after the Phillies won the 1980 World Series, was Eagles 20–7 victory over the Dallas Cowboys in the 1980 NFC Championship Game, played before 70,696 fans at the stadium on January 11, 1981.[40] As a psychological ploy, the Eagles chose to wear their white jerseys for their home game in order to force the Cowboys into their "unlucky" blue jerseys. At the end of the game, Philadelphia police circled the field with horses and dogs as they had done for the Phillies' World Series victory; despite the police presence, Eagles fans successfully rushed the field.[41]

- Veterans Stadium was host to the latest-finishing game in baseball history, a twinight double-header between the Phillies and San Diego Padres that started on July 2, 1993, at 5:05 pm and ended at 4:40 am the following morning. The two games were interrupted multiple times by rain showers. The Phillies lost the first game, 5–2,[42] and faced a 5–0 deficit in the second game before rallying for a come-from-behind victory in the tenth inning on a walk-off RBI single by closing pitcher Mitch Williams.[42] The second game ended with an estimated 6,000 fans at the ballpark.[18]

- The Phillies clinched the NLCS at the stadium twice: the first in 1983 over area-born Tommy Lasorda and the Los Angeles Dodgers, and the second in the 1993 NLCS over future divisional rivals the Atlanta Braves. The 1993 season was the last LCS under the two-division League format.

- The Phillies pitched two no-hit games at the stadium, the only nine-inning no-hitters in stadium history. Both were against the San Francisco Giants. Terry Mulholland pitched the first[43] on August 15, 1990, in a 6–0[44] Phillies win.[45] Kevin Millwood pitched the second on April 27, 2003, and beat the Giants 1–0,[46] upstaging the Phillie Phanatic's birthday promotion that afternoon. The Montreal Expos' Pascual Pérez pitched a five-inning[47] no-hitter shortened by rain on September 24, 1988. MLB changed its rules in 1991 to require that fully recognized no-hitters—past, present and future—be complete games of at least nine innings.[48]

- Another game that is well-remembered by Eagles fans was known as the "Body Bag Game", which took place on November 12, 1990, when the Washington Redskins visited the stadium for a Monday Night Football game. Eagles' head coach Buddy Ryan was quoted as saying that the Redskins' offense would "have to be carted off in body bags." The Eagles' number-one defense scored two touchdowns in a 28–14 Eagles win[49] in which the Eagles knocked nine players with the Redskins out of the game, including their first and second string quarterbacks.[50] The Redskins were forced to finish the game using running back/returner Brian Mitchell, who would become an Eagles player over a decade later at quarterback.[51]

- During the 1998 Army–Navy Game, a serious accident occurred when a support rail collapsed and eight West Point cadets were injured, which intensified calls for new stadiums for football and baseball in Philadelphia.[52]

- From 1979 into 1981, Tom Garvey, a stadium parking lot supervisor, Vietnam War veteran and friend of Phillies and Eagles players, lived semi-secretly (known to 25-30 people) under 300-level seats at the stadium.[53]

Other stadium events

[edit]Amateur baseball

[edit]From 1970 to 1987, the Cape Cod Baseball League (CCBL) played its annual all-star game at various major league stadiums. The games were interleague contests between the CCBL and the Atlantic Collegiate Baseball League (ACBL). The 1984 game was played at Veterans Stadium. The CCBL won the game 7–3 behind the performance of winning pitcher and future major leaguer Joe Magrane of the University of Arizona.[54]

The Liberty Bell Classic, Philadelphia Division I college baseball tournament, was played at the stadium from its inception in 1992 through 2003. The original eight schools were:

- Drexel University (Drexel Dragons)

- La Salle University (La Salle Explorers)

- Saint Joseph's University (the Hawks)

- Temple University (Temple Owls)

- University of Delaware (Delaware Fightin' Blue Hens)

- University of Pennsylvania (Penn Quakers)

- Villanova University (Villanova Wildcats)

- West Chester University (West Chester Golden Rams)

In the first championship game in 1992, the University of Delaware defeated Villanova 6–2.[55]

The stadium hosted the 1998 Atlantic 10 Conference baseball tournament, won by Fordham.[56]

Minor league baseball

[edit]In November 1987, the new owners of the Phillies AAA franchise, the Maine Guides, considered playing the 1988 season at the Vet because Lackawanna County Stadium would not be ready until the 1989 season. The team would have had to play 12:35 pm day games when the Phillies had night games scheduled at the Vet.[57] Ownership elected to remain in Old Orchard Beach for 1988, renamed the club the 'Maine Phillies', and moved to Moosic, Pennsylvania in 1989 as the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Red Barons.

The Eastern League Trenton Thunder played two home games at the stadium in April 1994. The Thunder beat the Canton–Akron Indians, 10–9, in front of 483 fans on April 20, 1994, and won 9–3 on April 21. Future Phillies broadcaster Tom McCarthy was in the booth for the Thunder during these two games.[58]

Soccer

[edit]The stadium was the home field for the Philadelphia Atoms and the Philadelphia Fury, both North American Soccer League teams. The Fury drew 18,191 fans for their April 1, 1978, opener at the stadium which they lost 3–0 to the Washington Diplomats. The Fury averaged 8,279 per-match in 1978 NASL, 5,624 per-match in 1979 NASL, and 4,778 in the 1980 NASL seasons. The club was moved to Montreal in 1981 NASL season.[59]

The stadium hosted an exhibition match on August 2, 1991, between the U.S. National Team and English professional soccer club Sheffield Wednesday F.C. John Harkes played for Wednesday, the first American to play in the English Premier League. 44,261 fans saw the U.S. score two second-half goals to defeat Sheffield Wednesday 2–0.[60]

Philadelphia established a bid committee to host matches for the 1994 World Cup which was to be played in the United States. Phillies president Bill Giles was on the Philadelphia bid committee and hoped to use Veterans Stadium for games. In addition to the challenge of installing a natural grass field for the games, FIFA would have required the Phillies to vacate the stadium for a month to allow for sufficient preparation time prior to the matches. Giles could only offer 17-days.[61] The nine venues eventually chosen to host matches were all stadiums that did not host baseball games.

| Date | Winning Team | Result | Losing Team | Tournament | Spectators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 2, 1991 | 2–0 | International friendly | 44,261 |

Professional softball

[edit]The Philadelphia Athletics of the American Professional Slo-Pitch League (APSPL) played their 1978 seasons at Veterans Stadium.

High school football

[edit]Veterans Stadium hosted Philadelphia's City Title high-school football championship game from 1973 to 1977 and in 1979. The series was suspended in 1980.[62] With the entry of the Philadelphia Catholic League into what is now PIAA District XII (which was formed when the Public League joined the PIAA in 2002), the "City Title Game" was restored in 2008.

Professional wrestling

[edit]The only professional wrestling event held in Veterans Stadium was NWA/Jim Crockett Promotions The Great American Bash on July 1, 1986, with an attendance of 10,900. The event was the start of a 14-city summer tour.

Concerts

[edit]| Date | Artist | Opening act(s) | Tour / Concert name | Attendance | Revenue | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 10, 1974 | Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young | The Band | CSNY 1974 | – | – | |

| August 14, 1985 | Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band | – | Born in the U.S.A. Tour | 108,000 / 108,000 | – | |

| August 15, 1985 | ||||||

| September 8, 1985 | Wham! | Chaka Khan Katrina and the Waves |

Whamamerica! | 43,000 / 50,000 | $698,000 | |

| May 28, 1987 | Genesis | Paul Young | Invisible Touch Tour | – | – | |

| May 29, 1987 | ||||||

| July 11, 1987 | Madonna | Level 42 | Who's That Girl World Tour | 48,182 / 51,500 | $969,815 | |

| July 30, 1987 | David Bowie | Squeeze | Glass Spider Tour | – | – | |

| July 31, 1987 | ||||||

| May 15, 1988 | Pink Floyd | – | A Momentary Lapse of Reason Tour | 88,010 / 95,800 | $1,917,675 | |

| May 16, 1988 | ||||||

| July 9, 1989 | The Who | – | The Who Tour 1989 | – | – | |

| July 10, 1989 | ||||||

| August 31, 1989 | The Rolling Stones | Living Colour | Steel Wheels Tour | 110,556 / 110,556 | $3,181,143 | |

| September 1, 1989 | ||||||

| July 14, 1990 | Paul McCartney | – | The Paul McCartney World Tour | 102,695 / 102,695 | $3,107,980 | |

| July 15, 1990 | ||||||

| September 15, 1990 | MC Hammer | After 7 Michel'le Oaktown's 3.5.7 |

Please Hammer Don't Hurt 'Em World Tour | |||

| May 31, 1992 | Genesis | – | We Can't Dance Tour | 97,774 / 97,774 | $1,518,080 | |

| June 1, 1992 | ||||||

| September 2, 1992 | U2 | Primus The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy |

Zoo TV Tour | 88,684 / 88,684 | $2,691,880 | |

| September 3, 1992 | ||||||

| June 13, 1993 | Paul McCartney | – | The New World Tour | 45,711 / 45,711 | $1,288,394 | |

| June 2, 1994 | Pink Floyd | – | The Division Bell Tour | 152,264 / 152,264 | $5,091,120 | |

| June 3, 1994 | ||||||

| June 4, 1994 | ||||||

| July 8, 1994 | Elton John Billy Joel |

– | Face to Face 1994 | 150,511 / 150,511 | $7,315,495 | |

| July 9, 1994 | ||||||

| July 12, 1994 | ||||||

| September 22, 1994 | The Rolling Stones | Blind Melon | Voodoo Lounge Tour | 80,976 / 80,976 | $3,818,719 | |

| September 23, 1994 | ||||||

| October 12, 1997 | Blues Traveler | Bridges to Babylon Tour | 56,651 / 56,651 | $3,275,572 | ||

| May 20, 1999 | Dave Matthews Band | Santana The Roots |

Summer Tour 1999 | – | – | |

| May 21, 1999 | ||||||

| May 22, 1999 | ||||||

| July 15, 2000 | Ozomatli Ben Harper & the Innocent Criminals |

Summer Tour 2000 | – | – | ||

| July 16, 2000 | ||||||

| June 13, 2001 | NSYNC | BBMak | PopOdyssey | 46,005 / 54,212 | $2,534,204 | |

| September 18, 2002 | The Rolling Stones | The Pretenders | Licks Tour | – | – | |

| July 12, 2003 | Metallica | Limp Bizkit Linkin Park Deftones Mudvayne |

Summer Sanitarium Tour | – | – | |

| July 26, 2003 | Bon Jovi | Sheryl Crow Goo Goo Dolls |

Bounce Tour | – | – | The stadium's final concert. |

Other events

[edit]The venue also played host to religious events including annual Jehovah's Witnesses conventions, which was open to the public each year it took place. It also played host to a Billy Graham crusade in 1992; the crusade was held on the same day that the Eagles' Jerome Brown was killed in a vehicular crash and Reggie White, who was invited to speak at the event, broke the news to the gathered crowd.

Photo gallery

[edit]-

Home plate at Veterans Stadium, home to the Philadelphia Phillies for 33 seasons, is remembered with this granite and bronze marker in the parking lot near Citizens Bank Park. (2006)

-

The mounting point for Veterans Stadium's west end zone goalpost, used by the Philadelphia Eagles for 32 seasons, is marked in the same parking lot (the east goalpost is similarly marked). (2011)

-

Veterans Stadium's pitching mound is marked. (2011)

-

A brief history of how the stadium was named and a tribute to veterans of all wars is on display outside where the stadium stood. (2006)

-

The historic marker shows the stadium's major moments. (2007)

-

Dedication plaque that once was attached to The Vet (2007)

References

[edit]- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Index". Ballparks.com. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers Search". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on March 21, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ Bernstein, Ralph (March 1, 1959). "Philadelphia On Verge of Losing Phils". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. p. 2-C.[dead link]

- ^ "Stadium Facts". Lincoln Financial Field. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ "Phillies Card 28 Spring Exhibitions". St. Petersburg Times. December 17, 1969. p. 2-C. Retrieved May 1, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Curtain Up On a Mod New Act". Sports Illustrated. April 17, 1971. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Frank (April 15, 2018). "Saga of Philly's 'Father Foxhole'". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ "April 10, 1971 Montreal Expos at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score and Play by Play". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ "Dallas Cowboys at Philadelphia Eagles – September 26, 1971". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ "Embarrassing Allegations In Philly". CBS News. January 10, 2002.

- ^ a b Anderson, Dave (October 29, 2002). "Sports of The Times; To Eagles, Shockey Is Public Enemy No. 1". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2009.

- ^ "Bucs Stop McNabb to Earn First Super Bowl Berth". ESPN. Associated Press. January 19, 2003. Archived from the original on February 16, 2003. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ "September 28, 2003 Atlanta Braves at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score and Play by Play". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Kevin (December 26, 2003). "Former Phillies GM Owens Dies at 79". USA Today. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ "Former relief pitcher Tug McGraw dead at 59". ESPN. January 6, 2004. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ Guts and Bolts: The Implosion of Veterans Stadium. The History Channel. July 10, 2004.

- ^ a b Westcott, Rich; Daulton, Darren (2005). Veteran's Stadium: Field of Memories. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 78, 204. ISBN 1-59213-428-9.

- ^ Ex-Phillies wonder if stadium is to blame for players' brain cancer

- ^ Brain cancer deaths of six former Phillies players must be investigated, says Dr. Siegel

- ^ a b Longman, Jeré (August 14, 2017). "The Brain Cancer That Keeps Killing Baseball Players (Published 2017)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2023.

- ^ "Tom Garvey of Ridley Park Had a Sweet Apartment at the Vet, and the Rent Was Great". Delco.Today. June 2, 2024. Retrieved January 23, 2025.

- ^ Longman, Jeré (2006). If Football's a Religion, Why Don't We Have a Prayer?. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-084373-1.

- ^ Hooper, Ernest (December 28, 2009). "They Say the Vet Stadium Turf Is Hard as Concrete – Maybe That's Why Last Week It Was Treated Like Piece of Philly Highway". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ Mitchell, Fred (October 10, 1993). "Bears – Yes, Bears – Gain First-Place Tie". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ Williams, Pete (January 15, 2001). "Versatility Wins Southwest Rec's Nexturf a Gig at Veterans Stadium". SportsBusiness Journal. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "N.F.L.: Roundup: Eagles' Turf Unsafe For Ravens' Game". The New York Times. August 14, 2001. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Six former Phillies died from the same brain cancer. We tested the Vet's turf and found dangerous chemicals".

- ^ "Philadelphia Eagles at Dallas Cowboys – November 23rd, 1989". Pro Football Reference. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ^ "Dallas Cowboys at Philadelphia Eagles – December 10th, 1989". Pro Football Reference. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ^ Eskenazi, Gerald (December 11, 1989). "Eagles Top Cowboys in an Emotional Contest". The New York Times. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (December 31, 1995). "December 24–30; Icy Reception". The New York Times. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ "San Francisco 49ers at Philadelphia Eagles – November 10th, 1997". Pro Football Reference. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ "Dallas Cowboys at Philadelphia Eagles – November 2nd, 1998". Pro Football Reference. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Peeing in sinks, fights in the stands, a flare gun(!): The awful antics that birthed Eagles Court at the Vet, and why it went away". September 11, 2015.

- ^ "'They Were Throwing Batteries'; Phillies Fans Hurl Insults, Projectiles at J. D. Drew". CNN/Sports Illustrated. Associated Press. August 11, 1998. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ "June 25, 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score and Play by Play". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Mandel, Ken (June 25, 2003). "Stargell's Star a Lasting Tribute; Blast is Marking Point for All Hitters". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on January 20, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Frank (June 30, 2003). "Blast From the Past; Stargell's Upper-Deck Home Run at Veterans Stadium in '71 Still Has Plenty of Clout". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved April 7, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Dallas Cowboys at Philadelphia Eagles – January 11, 1981". Pro Football Reference. Sports Reference. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Wulf, Steve (January 19, 1981). "Eagles That Didn't Need Wings". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ a b "July 2, 1993 San Diego Padres at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score and Play by Play". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ Gennaria, Mike (August 19, 2003). "Mulholland Recalls Vet No-Hitter". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on January 20, 2010. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ "August 15, 1990 San Francisco Giants at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score and Play by Play". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ "Phillies' Mulholland Pitches Season's 8th No-Hitter". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 16, 1990. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ "April 27, 2003 San Francisco Giants at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score and Play by Play". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ "September 24, 1988 Montreal Expos at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score and Play by Play". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ Chass, Murray (September 5, 1991). "Maris's Feat Finally Recognized 30 Years After Hitting 61 Homers". The New York Times. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ "Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles – November 12th, 1990". Pro Football Reference. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ "Ex-Bama Star Fades in Philly". Rome News-Tribune. Associated Press. November 13, 1990. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Didinger, Ray; Lyons, Robert S. (2005). The Eagles Encyclopedia. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 250–251. ISBN 1-59213-449-1. Retrieved April 2, 2009.

- ^ Berger, Ken (December 7, 1998). "Nine Injured in Fall When Railing Breaks at Veterans Stadium". Daily Pennsylvanian. University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Alan Yuhas (March 20, 2021). "Man Says He Lived in Philadelphia's Veterans Stadium for Years". The New York Times. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Class of 2009 Elected to Cape League's Hall of Fame". capecodbaseball.org. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- ^ "At Bat in Our Community: Liberty Bell Classic". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ "Atlantic 10 Conference Baseball Record Book" (PDF). Atlantic 10 Conference. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ "Park Delay May Force Guides back". Lewiston (Maine) Daily Sun. November 19, 1987. p. 21. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ Edwards, Christopher T. (1997). Filling in the Seams: The Story of Trenton Thunder Baseball. B B& A Publishers. pp. 62–65. ISBN 0-912608-97-8.

- ^ Holroyd, Steve. "Remembering the "Pseudo-Atoms" – The Philadelphia Fury, 1978–1980". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ "This May Be the Kick American Soccer Needs". Business Week. September 16, 1991. Archived from the original on December 1, 2004. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ^ Jensen, Mike (June 5, 1991). "World Cup Bid Might Fall Short; Sites Needed for One Month". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. C01. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ "FB City Title Recaps". Ted Sillary. Retrieved April 23, 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- Birker, Paul Arthur (2005). Veterans Stadium: Field of Memories. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-59213-428-9.

- Westcott, Rich (2005). Veterans Stadium: Dismantled. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 1-4134-5915-3.[self-published source]

External links

[edit]| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Home of the Philadelphia Eagles 1971–2002 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Philadelphia Phillies 1971–2003 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Temple Owls 1978–2002 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of the All-Star Game 1976 1996 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of NFC Championship Game 1981 2003 |

Succeeded by |