Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wine fault

View on WikipediaA wine fault is a sensory-associated (organoleptic[1]) characteristic of a wine that is unpleasant, and may include elements of taste, smell, or appearance, elements that may arise from a "chemical or a microbial origin", where particular sensory experiences (e.g., an off-odor) might arise from more than one wine fault.[2] Wine faults may result from poor winemaking practices or storage conditions that lead to wine spoilage.[citation needed]

In the case of a chemical origin, many compounds causing wine faults are already naturally present in wine, but at insufficient concentrations to be of issue, and in fact may impart positive characters to the wine; however, when the concentration of such compounds exceed a sensory threshold, they replace or obscure desirable flavors and aromas that the winemaker wants the wine to express. The ultimate result is that the quality of the wine is reduced (less appealing, sometimes undrinkable), with consequent impact on its value.[3][verification needed]

There are many underlying causes of wine faults, including poor hygiene at the winery, excessive or insufficient exposure of the wine to oxygen, excessive or insufficient exposure of the wine to sulphur, overextended maceration of the wine either pre- or post-fermentation, faulty fining, filtering and stabilization of the wine, the use of dirty oak barrels, over-extended barrel aging and the use of poor quality corks. Outside of the winery, other factors within the control of the retailer or end user of the wine can contribute to the perception of flaws in the wine. These include poor storage of the wine that exposes it to excessive heat and temperature fluctuations as well as the use of dirty stemware during wine tasting that can introduce materials or aromas to what was previously a clean and fault-free wine.[3][verification needed][4][verification needed]

Differences between flaws and faults

[edit]In wine tasting, there is a big distinction made between what is considered a flaw and a fault. Wine flaws are minor attributes that depart from what are perceived as normal wine characteristics. These include excessive sulfur dioxide, volatile acidity, Brettanomyces or "Brett aromas" and diacetyl or buttery aromas. The amount to which these aromas or attributes become excessive is dependent on the particular tastes and recognition threshold of the wine taster. Generally, a wine exhibiting these qualities is still considered drinkable by most people. However, some flaws such as volatile acidity and Brettanomyces can be considered a fault when they are in such an excess that they overwhelm other components of the wine. Wine faults are generally major attributes that make a wine undrinkable to most wine tasters. Examples of wine faults include acetaldehyde (except when purposely induced in wines like Sherry and Rancio), ethyl acetate and cork taint.[3]

Detecting faults in wine tasting

[edit]

The vast majority of wine faults are detected by the nose and the distinctive aromas that they give off. However, the presence of some wine faults can be detected by visual and taste perceptions. For example, premature oxidation can be noticed by the yellowing and browning of the wine's color. The sign of gas bubbles in wines that are not meant to be sparkling can be a sign of refermentation or malolactic fermentation happening in the bottle. Unusual breaks in the color of the wine could be a sign of excessive copper, iron or proteins that were not removed during fining or filtering. A wine with an unusual color for its variety or wine region could be a sign of excessive or insufficient maceration as well as poor temperature controls during fermentation. Tactile clues of potential wine faults include the burning, acidic taste associated with volatile acidity that can make a wine seem out of balance.[3][4]

| Wine fault | Characteristics |

| Acetaldehyde | Smell of roasted nuts or dried out straw. Often described as green apples and emulsion paint. Commonly associated with Sherries where these aromas are considered acceptable |

| Amyl-acetate | Smell of "fake" candy banana flavoring |

| Brettanomyces | Smell of barnyards, fecal and gamey horse aromas |

| Cork taint | Smell of a damp basement, wet cardboard or newspapers and mushrooms |

| Butyric acid | Smell of rancid butter |

| Ethyl acetate | Smell of vinegar, paint thinner and nail polish remover |

| Hydrogen sulfide | Smell of rotten eggs or garlic that has gone bad |

| Iodine | Smell of moldy grapes |

| Lactic acid bacteria | Smell of sauerkraut |

| Mercaptans | Smell of burnt garlic or onion |

| Oxidation | Smell of cooked fruit and walnuts. Also detectable visually by premature browning or yellowing of the wine |

| Sorbic acid plus lactic acid bacteria | Smell of crushed geranium leaves |

| Sulfur dioxide | Smell of burnt matches. Can also come across as a pricking sensation in the nose. |

Oxidation

[edit]The oxidation of wine is perhaps the most common of wine faults, as the presence of oxygen and a catalyst are the only requirements for the process to occur. Oxidation can occur throughout the winemaking process, and even after the wine has been bottled. Anthocyanins, catechins, epicatechins and other phenols present in wine are those most easily oxidised,[5] which leads to a loss of colour, flavour and aroma - sometimes referred to as flattening. In most cases compounds such as sulfur dioxide or erythorbic acid are added to wine by winemakers, which protect the wine from oxidation and also bind with some of the oxidation products to reduce their organoleptic effect.[6] Apart from phenolic oxidation, the ethanol present within wine can also be oxidised into other compounds responsible for flavour and aroma taints. Some wine styles can be oxidised intentionally, as in certain Sherry wines and Vin jaune from the Jura region of France.

Acetaldehyde

[edit]Acetaldehyde is an intermediate product of yeast fermentation; however, it is more commonly associated with ethanol oxidation catalysed by the enzyme ethanol dehydrogenase. Acetaldehyde production is also associated with the presence of surface film forming yeasts and bacteria, such as acetic acid bacteria, which form the compound by the decarboxylation of pyruvate. The sensory threshold for acetaldehyde is 100–125 mg/L. Beyond this level it imparts a sherry type character to the wine which can also be described as green apple, sour and metallic. Acetaldehyde intoxication is also implicated in hangovers.

Acetic acid

[edit]Acetic acid in wine, often referred to as volatile acidity (VA) or vinegar taint, can be contributed by many wine spoilage yeasts and bacteria. This can be from either a by-product of fermentation, or due to the spoilage of finished wine. Acetic acid bacteria, such as those from the genera Acetobacter and Gluconobacter produce high levels of acetic acid. The sensory threshold for acetic acid in wine is >700 mg/L, with concentrations greater than 1.2-1.3 g/L becoming unpleasant.

There are different opinions as to what level of volatile acidity is appropriate for higher quality wine. Although too high a concentration is sure to leave an undesirable, 'vinegar' tasting wine, some wine's acetic acid levels are developed to create a more 'complex', desirable taste.[7] The renowned 1947 Cheval Blanc is widely recognized to contain high levels of volatile acidity.

Ethyl acetate is formed in wine by the esterification of ethanol and acetic acid. Therefore, wines with high acetic acid levels are more likely to see ethyl acetate formation, but the compound does not contribute to the volatile acidity. It is a common microbial fault produced by wine spoilage yeasts, particularly Pichia anomala or Kloeckera apiculata. High levels of ethyl acetate are also produced by lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria.

Sulfur compounds

[edit]Sulfur is used as an additive throughout the winemaking process, primarily to stop oxidation as mentioned above but also as antimicrobial agent. When managed properly in wine, its presence there is often undetected, however when used recklessly it can contribute to flavour and aroma taints which are very volatile and potent. Sulfur compounds typically have low sensory thresholds.

Sulfur dioxide

[edit]

Sulfur dioxide is a common wine additive, used for its antioxidant and preservative properties. When its use is not managed well it can be overadded, with its perception in wine reminiscent of matchsticks, burnt rubber, or mothballs. Wines such as these are often termed sulfitic.

Hydrogen sulfide

[edit]

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is generally thought to be a metabolic by-product of yeast fermentation in nitrogen limited environments. It is formed when yeast ferments via the sulfate reduction pathway. Fermenting wine is often supplemented with diammonium phosphate (DAP) as a nitrogen source to prevent H2S formation. The sensory threshold for hydrogen sulfide is 8-10 μg/L, with levels above this imparting a distinct rotten egg aroma to the wine. Hydrogen sulfide can further react with wine compounds to form mercaptans and disulfides.

Mercaptans

[edit]

Mercaptans (thiols) are produced in wine by the reaction of hydrogen sulfide with other wine components such as ethanol. They can be formed if finished wine is allowed prolonged contact with the lees. This can be prevented by racking the wine. Mercaptans have a very low sensory threshold, around 1.5 μg/L,[8] with levels above causing onion, rubber, and skunk type odours. Note that dimethyl disulfide is formed from the oxidation of methyl mercaptan.

Dimethyl sulfide

[edit]

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS) is naturally present in most wines, probably from the breakdown of sulfur containing amino acids. Like ethyl acetate, levels of DMS below the sensory threshold can have a positive effect on flavour, contributing to fruityness, fullness, and complexity. Levels above the sensory threshold of >30 μg/L in white wines and >50 μg/L for red wines, give the wine characteristics of cooked cabbage, canned corn, asparagus or truffles.

Environmental

[edit]Cork taint

[edit]

Cork taint is a wine fault mostly attributed to the compound 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (TCA), although other compounds such as guaiacol, geosmin, 2-methylisoborneol, 1-octen-3-ol, 1-octen-3-one, 2,3,4,6-tetrachloroanisole, pentachloroanisole, and 2,4,6-tribromoanisole are also thought to be involved.[9] TCA most likely originates as a metabolite of mould growth on chlorine-bleached wine corks and barrels. It causes earthy, mouldy, and musty aromas in wine that easily mask the natural fruit aromas, making the wine very unappealing. Wines in this state are often described as "corked". As cork taint has gained a wide reputation as a wine fault, other faults are often mistakenly attributed to it.

Heat damage

[edit]Heat damaged wines are often casually referred to as cooked, which suggests how heat can affect a wine. They are also known as maderized wine, from Madeira wine, which is intentionally exposed to heat. The ideal storage temperature for wine is generally accepted to be 13 °C (55 °F). Wines that are stored at temperatures greatly higher than this will experience an increased aging rate. Wines exposed to extreme temperatures will thermally expand, and may even push up between the cork and bottle and leak from the top. When opening a bottle of wine, if a trace of wine is visible along the length of the cork, the cork is partially pushed out of the bottle, or wine is visible on the top of the cork while it is still in the bottle, it has most likely been heat damaged. Heat damaged wines often become oxidized, and red wines may take on a brick color.

Even if the temperatures do not reach extremes, temperature variation alone can also damage bottled wine through oxidation. All corks allow some leakage of air (hence old wines become increasingly oxidized), and temperature fluctuations will vary the pressure differential between the inside and outside of the bottle and will act to "pump" air into the bottle at a faster rate than will occur at any temperature strictly maintained.

Reputedly, heat damage is the most widespread and common problem found in wines. It often goes unnoticed because of the prevalence of the problem, consumers don't know it's possible, and most often would just chalk the problem up to poor quality, or other factors.

Lightstrike

[edit]Lightstruck wines are those that have had excessive exposure to ultraviolet light, particularly in the range 325 to 450 nm.[10] Very delicate wines, such as Champagnes, are generally worst affected, with the fault causing a wet cardboard or wet wool type flavour and aroma. Red wines rarely become lightstruck because of the phenolic compounds present within the wine that protect it. Lightstrike is thought to be caused by sulfur compounds such as dimethyl sulfide. In France lightstrike is known as "goût de lumière", which translates to a taste of light. The fault explains why wines are generally bottled in coloured glass, which blocks the ultraviolet light, and why wine should be stored in dark environments.

Ladybird (pyrazine) taint

[edit]Some insects present in the grapes at harvest inevitably end up in the press and for the most part are inoffensive. Others, notably the Asian lady beetle, release unpleasant-smelling nitrogen heterocycles as a defensive mechanism when disturbed. In sufficient quantities, these can affect the wine's odor and taste. With an olfactory detection threshold of a few ppb, the principal active compound is isopropyl methoxypyrazine; this molecule is perceived as rancid peanut butter, green bell pepper, urine, or simply bitter. This is also a naturally occurring compound in Sauvignon grapes, and so pyrazine taint has been known to make Rieslings taste like Sauvignon blanc.[citation needed]

Microbiological

[edit]Brettanomyces (Dekkera)

[edit]

The yeast Brettanomyces produces an array of metabolites when growing in wine, some of which are volatile phenolic compounds. Together these compounds are often referred to as phenolic taint, "Brettanomyces character", or simply "Brett". The main constituents are listed below, with their sensory threshold and common sensory descriptors:

- 4-ethylphenol (>140 μg/L): Band-aids, barnyard, horse stable, antiseptic

- 4-ethylguaiacol (>600 μg/L): Bacon, spice, cloves, smoky

- isovaleric acid: Sweaty, cheese, rancidity

Geosmin

[edit]

Geosmin is a compound with a very distinct earthy, musty, beetroot, even turnip flavour and aroma and has an extremely low sensory threshold of down to 10 parts per trillion. Its presence in wine is usually derived as metabolite from the growth of filamentous actinomycetes such as Streptomyces, and moulds such as Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum, on grapes. Wines affected by but not attributed to geosmins are often thought to have earthy properties due to terroir.[11] The geosmin fault occurs worldwide and has been found in recent vintages of red wines from Beaujolais, Bordeaux, Burgundy and the Loire in France. Geosmin is also thought to be a contributing factor in cork taint.

Lactic acid bacteria

[edit]Lactic acid bacteria have a useful role in winemaking converting malic acid to lactic acid in malolactic fermentation. However, after this function has completed, the bacteria may still be present within the wine, where they can metabolise other compounds and produce wine faults. Wines that have not undergone malolactic fermentation may be contaminated with lactic acid bacteria, leading to refermentation of the wine with it becoming turbid, swampy, and slightly effervescent or spritzy. This can be avoided by sterile filtering wine directly before bottling. Lactic acid bacteria can also be responsible for other wine faults such as those below.

Bitterness taint

[edit]

Bitterness taint or amertume is rather uncommon and is produced by certain strains of bacteria from the genera Pediococcus, Lactobacillus, and Oenococcus. It begins by the degradation of glycerol, a compound naturally found in wine at levels of 5-8 g/L, via a dehydratase enzyme to 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde. During ageing this is further dehydrated to acrolein which reacts with the anthocyanins and other phenols present within the wine to form the taint.[12] As red wines contain high levels of anthocyanins they are generally more susceptible.

Diacetyl

[edit]

Diacetyl in wine is produced by lactic acid bacteria, mainly Oenococcus oeni. In low levels it can impart positive nutty or caramel characters, however at levels above 5 mg/L it creates an intense buttery or butterscotch flavour, where it is perceived as a flaw. The sensory threshold for the compound can vary depending on the levels of certain wine components, such as sulfur dioxide. It can be produced as a metabolite of citric acid when all of the malic acid has been consumed. Diacetyl rarely taints wine to levels where it becomes undrinkable.[13]

Geranium taint

[edit]

Geranium taint, as the name suggests, is a flavour and aroma taint in wine reminiscent of geranium leaves. The compound responsible is 2-ethoxyhexa-3,5-diene, which has a low sensory threshold concentration of 1 ng/L.[14] In wine it is formed during the metabolism of potassium sorbate by lactic acid bacteria. Potassium sorbate is sometimes added to wine as a preservative against yeast, however its use is generally kept to a minimum due to the possibility of the taint developing. The production of the taint begins with the conversion of sorbic acid to the alcohol sorbinol. The alcohol is then isomerised in the presence of acid to 3,5-hexadiene-2-ol, which is then esterified with ethanol to form 2-ethoxy-3,5-hexadiene. As ethanol is necessary for the conversion, the geranium taint is not usually found in must.

Mannitol

[edit]

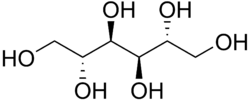

Mannitol is a sugar alcohol, and in wine it is produced by heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactobacillus brevis, by the reduction of fructose. Its perception is often complicated as it generally exists in wine alongside other faults, but it is usually described as viscous, ester-like combined with a sweet and irritating finish.[12] Mannitol is usually produced in wines that undergo malolactic fermentation with a high level of residual sugars still present. Expert winemakers oftentimes add small amounts of sulfur dioxide during the crushing step to reduce early bacterial growth.

Ropiness

[edit]Ropiness is manifested as an increase in viscosity and a slimey or fatty mouthfeel of a wine. In France the fault is known as "graisse", which translates to fat. The problem stems from the production of dextrins and polysaccharides by certain lactic acid bacteria, particularly of the genera Leuconostoc and Pediococcus.

Mousiness

[edit]

tetrahydropyridine

Mousiness is a wine fault most often attributed to Brettanomyces but can also originate from the lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus brevis, Lactobacillus fermentum, and Lactobacillus hilgardii,[12] and hence can occur in malolactic fermentation. The compounds responsible are lysine derivatives, mainly;

- 2-acetyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydropyridine

- 2-acetyl-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyridine

- 2-ethyltetrahydropyridine[15]

- 2-acetyl-1-pyrrolene

The taints are not volatile at the pH of wine, and therefore not obvious as an aroma. However, when mixed with the slightly basic pH of saliva they can become very apparent on the palate,[16] especially at the back of the mouth, as mouse cage or mouse urine.

Refermentation

[edit]Refermentation, sometimes called secondary fermentation, is caused by yeasts refermenting the residual sugar present within bottled wine. It occurs when sweet wines are bottled in non-sterile conditions, allowing the presence of microorganisms. The most common yeast to referment wine is the standard wine fermentation yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, but has also been attributed to Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Zygosaccharomyces bailii.[12] The main issues associated with the fault include turbidity (from yeast biomass production), excess ethanol production (may violate labelling laws), slight carbonation, and some coarse odours. Refermentation can be prevented by bottling wines dry (with residual sugar levels <1.0g/L), sterile filtering wine prior to bottling, or adding preservative chemicals such as dimethyl dicarbonate. The Portuguese wine style known as "vinhos verdes" used to rely on this secondary fermentation in bottle to impart a slight spritziness to the wine, but now usually uses artificial carbonation.

Bunch rots

[edit]Organisms responsible for bunch rot of grape berries are filamentous fungi, the most common of these being Botrytis cinerea (gray mold) However, there are a range of other fungi responsible for the rotting of grapes such as Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., and fungi found in subtropical climates (e.g., Colletotrichum spp. (ripe rot) and Greeneria uvicola (bitter rot)). A further group more commonly associated with diseases of the vegetative tissues of the vine can also infect grape berries (e.g., Botryosphaeriaceae, Phomopsis viticola). Compounds found in bunch rot affected grapes and wine are typically described as having mushroom, earthy odors and include geosmin, 2-methylisoborneol, 1-octen-3-ol, 2-octen-1-ol, fenchol and fenchone.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Organoleptic. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 26, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/organoleptic.

- ^ Watrelot, Aude; Savits, Jennie & Moroney, Maureen (2020). "Wine Fault Series" (PDF). ISU Extension and Outreach (Extension.IAState.edu). Ames, IA: Iowa State University (ISU). Retrieved June 26, 2023.

This summary document lists the common wine faults including the name of the fault, the type of the fault, the odor characteristics, and the chemical responsible. A wine fault is an unpleasant organoleptic characteristic including look, smell, or taste. Wine faults can come from a chemical or a microbial origin and some off-odors can be the result of multiple faults.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d M. Baldy: "The University Wine Course", Third Edition, pp. 37-39, 69-80, 134-140. The Wine Appreciation Guild 2009 ISBN 0932664695.[verification needed]

- ^ a b D. Bird: "Understanding Wine Technology", pp. 31-82, 155-184, 202-222. DBQA Publishing 2005 ISBN 1891267-914.[verification needed]

- ^ duToit, W.J. (2005). Oxygen in winemaking: Part I. WineLand, accessed on 2 April 2006.

- ^ Goode, Jamie (06/25/19). Oxidation in wine Archived 2021-02-10 at the Wayback Machine. internationalwinechallenge.com, accessed on 10 February 2021.

- ^ Volatile Acidity - article from Wine & Spirit magazine.

- ^ Technical Bulletin - Sulfides in Wine Archived 2007-12-11 at the Wayback Machine. etslabs.com, accessed on 12 March 2006.

- ^ LaMar, Jim (09/25/02). Cork Taint, accessed on 12 March 2006.

- ^ Drouhin, R.J. (01/23/98) Bottle Glass Archived 2007-12-11 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 3 April 2006.

- ^ Kennel, Florence (14/12/05). Bordeaux boffin solves geosmin conundrum. Decanter.com, accessed on 2 April 2006.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d duToit, M., Pretorius, I.S. (2000). "Microbial spoilage and preservation of wine: Using weapons from nature's own arsenal - A review". South African Journal of Enology and Viticulture 21: 74-96.

- ^ Gibson, George; Farkas, Mike Flaws and Faults in Wine, accessed on 12 March 2006.

- ^ "Wine Faults, Flavours, and Taints". The Australian Wine Research Institute. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Marais, Johann Flavourful nitrogen containing wine constituents Archived 2006-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Wynboer.co.za, accessed on 12 March 2006.

- ^ Gawell, Richard Somellier, A Mouse Must Have Wee'd in My Wine!. aromadictionary.com, accessed on 12 March 2006.

- ^ Grapevine bunch rots: impacts on wine composition, quality, and potential procedures for the removal of wine faults. Steel CC, Blackman JW and Schmidtke LM, J Agric Food Chem., 5 June 2013, volume 61, issue 22, pp. 5189-5206, doi:10.1021/jf400641r.

External links

[edit]- Organoleptic defects in wine (PDF document) Link Not Working

- How to Spot Faulty Wine, from The Wine Doctor Link Not Working

- [1] in Enobytes Wine Online