Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Volhynia

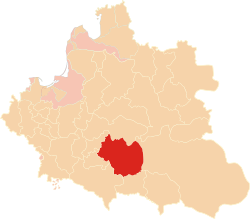

View on WikipediaVolhynia or Volynia (/voʊˈlɪniə/ voh-LIN-ee-ə; see #Names and etymology) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in Ukraine it is roughly equivalent to Volyn Oblast, Rivne Oblast, and the northern part of the Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Ternopil Oblast. The territory that still carries the name is Volyn Oblast.

Key Information

Volhynia has changed hands numerous times throughout history and been divided among competing powers. For centuries it was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. After the Russian annexation during the Partitions of Poland, all of Volhynia was made part of the Pale of Settlement on the southwestern border of the Russian Empire. Important cities include Rivne, Lutsk, Zviahel, and Volodymyr.

Names and etymology

[edit]- Ukrainian: Волинь, romanized: Volynʹ, pronounced [woˈlɪnʲ] ⓘ;

- Polish: Wołyń [ˈvɔwɨɲ] ⓘ;

- Russian: Волынь, romanized: Volynʹ, pronounced [vɐˈlɨnʲ];

- Lithuanian: Voluinė or Volynė;

- Slovak: Volyňa;

- Czech: Volyň [ˈvolɪɲ];

- Romanian: Volhînia;

- Hungarian: Volhínia or Lodoméria;

- German: Wolhynien or Wolynien (both [voˈlyːni̯ən] ⓘ); Volhynian German: Wolhynien, Wolhinien, Wolynien or Wolinien (all [voˈliːni̯ən]);

- Yiddish: װאָהלין, romanized: Vohlin, or װאָלין, Volin.

The alternative name for the region is Lodomeria after the city of Volodymyr, which was once a political capital of the medieval Volhynian Principality.

According to some historians, the region is named after a semi-legendary city of Volin or Velin, said to have been located on the Southern Bug River,[1] whose name may come from the Proto-Slavic root *vol/vel- 'wet'. In other versions, the city was located over 20 km (12 mi) to the west of Volodymyr near the mouth of the Huczwa River, a tributary of the Western Bug.

Geography

[edit]

Geographically it occupies northern areas of the Volhynian-Podolian Upland and western areas of Polesian Lowland along the Pripyat valley as part of the vast East European Plain, between the Western Bug in the west and upper streams of Uzh and Teteriv rivers.[2] Before the partitions of Poland, the eastern edge stretched a little west along the right-banks of the Sluch River or just east of it. Within the territory of Volhynia is located Little Polisie, a lowland that actually divides the Volhynian-Podolian Upland into separate Volhynian Upland and northern outskirts of Podolian Upland, the so-called Kremenets Hills. Volhynia is located in the basins of the Western Bug and Pripyat, therefore most of its rivers flow either in a northern or a western direction.

Relative to other historical regions, it is northeast of Galicia, east of Lesser Poland and northwest of Podolia. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, and it is often considered to overlap a number of other regions, among which are Polesia and Podlasie.

The territories of historical Volhynia are now part of the Volyn, Rivne and parts of the Zhytomyr, Ternopil and Khmelnytskyi oblasts of Ukraine, as well as parts of Poland (see Chełm). Major cities include Lutsk, Rivne, Kovel, Volodymyr, Kremenets (Ternopil Oblast) and Starokostiantyniv (Khmelnytskyi Oblast). Before World War II, many Jewish shtetls (small towns), such as Trochenbrod and Lozisht, were an integral part of the region.[3]: 770 At one time all of Volhynia was part of the Pale of Settlement designated by Imperial Russia on its southwesternmost border.[4]

History

[edit]The first records can be traced to the Ruthenian chronicles, such as the Primary Chronicle, which mentions tribes of the Dulebes, Buzhans and Volhynians. The land was mentioned in the works of Al-Masudi and Abraham ben Jacob that in ancient times the Walitābā and king Mājik, which some read as Walīnānā and identified with the Volhynians, were "the original, pure-blooded Saqaliba, the most highly honoured" and dominated the rest of the Slavic tribes, but due to "dissent" their "original organization was destroyed" and "the people divided into factions, each of them ruled by their own king", implying existence of a Slavic federation which perished after the attack of the Pannonian Avars.[5][6]: 37

Volhynia may have been included in (or was in the sphere of influence of) the Grand Duchy of Kiev (Ruthenia) as early as the tenth century. At that time Princess Olga sent a punitive raid against the Drevlians to avenge the death of her husband Grand Prince Igor (Ingvar Röreksson); she later established pogosts along the Luha River. In the opinion of the Ukrainian historian Yuriy Dyba, the chronicle phrase «и оустави по мьстѣ. погосты и дань. и по лузѣ погосты и дань и ѡброкы» (and established in place pogosts and tribute along Luha), the path of pogosts and tribute reflects the actual route of Olga's raid against the Drevlians further to the west, up to the Western Bug's right tributary Luha River.

As early as 983, Vladimir the Great appointed his son Vsevolod as the ruler of the Volhynian principality. In 988, he established the city of Volodymer (Володимѣръ).

Volhynia's early history coincides with that of the duchies or principalities of Galicia and Volhynia. These two successor states of the Kievan Rus formed Galicia–Volhynia between the 12th and the 14th centuries.

After the disintegration of the Galicia–Volhynia circa 1340, the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania divided the region, Poland taking western Volhynia and Lithuania taking eastern Volhynia (1352–1366). During this period many Poles and Jews settled in the area. The Roman and Greek Catholic churches became established in the province. In 1375, a Roman Catholic Diocese of Lodomeria was established, but it was suppressed in 1425. Many Orthodox churches joined the latter organization in order to benefit from a more attractive legal status. Records of the first agricultural colonies of Mennonites, religious refugees of Dutch, Frisian and German background, date from 1783. After 1569, Volhynia was organized as a voivodeship within the larger Lesser Poland Province of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Future Polish King Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki spent a part of childhood in Volhynia.

Late modern period

[edit]A small south-western part of Volhynia was annexed by Austria in the First Partition of Poland in 1772.

In 1783, a porcelain factory was founded in Korzec by Józef Klemens Czartoryski.

After the Third Partition of Poland in 1795, the remainder of Volhynia was annexed as the Volhynian Governorate of the Russian Empire. It covered an area of 71,852.7 square kilometres. Following this annexation, the Russian government greatly changed the religious make-up of the area: it forcibly liquidated the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, transferring all of its buildings to the ownership and control of the Russian Orthodox Church. Many Roman Catholic church buildings were also given to the Russian Church. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Lutsk was suppressed by order of Empress Catherine II.

Several battles of the Polish 1863 January Uprising against Russia were fought in the region, including the Battle of Salicha.

In 1897, the population amounted to 2,989,482 people (41.7 per square kilometre). It consisted of 73.7 percent East Slavs (predominantly Ukrainians), 13.2 percent--400,000 Jews, 6.2 percent Poles, and 5.7 percent Germans.[7] Most of the German settlers had immigrated from Congress Poland. A small number of Czech settlers also had migrated here. Their main regional center was Kwasiłów. Although economically the area was developing rather quickly, upon the eve of the First World War it was still the most rural province in Western Russian Empire.

World War I

[edit]During World War I, Volhynia was the place of several battles, fought by the Austrians, Germans and the Polish Legions against Russia, eg. the Battle of Kostiuchnówka. (The village of Kostiuchnówka is known for the Battle of Kostiuchnówka, in which the Poles defeated the Russians, (and as the place of establishment of the accomplished Legia Warsaw football club, relocated to Warsaw only in 1920.))

After the 1917 February Revolution and the formation of the Russian Provisional Government, Ukrainian nationalists declared the autonomous Ukrainian People's Republic. The territory of Volhynia was split in half by a frontline just west of the city of Lutsk. Due to an invasion of the Bolsheviks, the government of Ukraine was forced to retreat to Volhynia after the sack of Kyiv. Military aid from the Central Powers as a result of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk brought peace in the region and some degree of stability. Until the end of the war, the area saw a revival of Ukrainian culture after years of Russian oppression and the denial of Ukrainian traditions. After German troops were withdrawn, the whole region was engulfed by a new wave of military actions by Poles and Russians competing for control of the territory. The Ukrainian People's Army was forced to fight on three fronts: Bolsheviks, Poles and a Volunteer Army of Imperial Russia.

Interwar period

[edit]

In 1919, Volhynia became part of the Polish-controlled Volhynian District. In 1921, after the end of the Polish–Soviet War, the treaty known as the Peace of Riga divided Volhynia between Poland and the Soviet Union, with Poland retaining the larger part, in which the Volhynian Voivodeship was established with the capital in Łuck, and the largest city being Równe.

Most of eastern Volhynian Governorate became part of the Ukrainian SSR, eventually being split into smaller districts. During that period, a number of the Marchlewszczyzna Polish national districts was formed in the Soviet-controlled part of Volhynia. In 1931, the Vatican of the Roman Catholic Church established a Ukrainian Catholic Apostolic Exarchate of Volhynia, Polesia and Pidliashia, where the congregation practiced the Byzantine Rite in Ukrainian language.

From 1935 to 1938, the government of the Soviet Union deported numerous nationals from Volhynia in a population transfer to Siberia and Central Asia, as part of the dekulakization, an effort to suppress peasant farmers in the region. These people included Poles of Eastern Volhynia (see Population transfer in the Soviet Union).

World War II

[edit]

Following the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1939, and the subsequent invasion and division of Polish territories between the Reich and the USSR, the Soviet Union invaded and occupied the Polish part of Volhynia. In the course of the Nazi–Soviet population transfers which followed this (temporary) German-Soviet alliance, most of the ethnic German-minority population of Volhynia were transferred to those Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany. Following the mass deportations and arrests carried out by the NKVD, and repressive actions against Poles taken by Germany, including deportation to the Reich to forced labour camps, arrests, detention in camps and mass executions, by 1943 ethnic Poles constituted only 10–12% of the entire population of Volhynia.

During the German invasion, the Jewish population in Volhynia was approximately 460,000. About 400,000–450,000 Jews[citation needed] and 100,000 Poles (men, women and children) in Volhynia were massacred by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and Ukraine collaborators. The Jews were shot and thousands buried in large pits. The main massacre took place between August and October 1942. It is estimated that about 1.5% survived the Holocaust. The number of Ukrainian victims of Polish retaliatory attacks until the spring of 1945 is estimated at approx. 2,000−3,000 in Volhynia.[8]

The Germans operated the Stalag 346, Stalag 357 and Stalag 360 prisoner-of-war camps in Volhynia.[9]

In 1945, Soviet Ukraine expelled ethnic Germans from Volhynia following the end of the war, claiming that Nazi Germany had used ethnic Germans in eastern Europe as part of its Generalplan Ost. The expulsion of Germans from eastern Europe was part of broader mass population transfers after the war.

The Soviet Union annexed Volhynia to Ukraine after the end of World War II. In 1944, the communists in Volhynia suppressed the Ukrainian Catholic Apostolic Exarchate. Most of the remaining ethnic Polish population were expelled to Poland in 1945. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, Volhynia has been an integral part of Ukraine.

Important relics

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Church of the Intercession in Piddubtsi

-

Korets Castle ruins

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pospelov, E. M. [in Russian] (1998). Ageeva, R. A. [in Russian] (ed.). Географические названия мира. Топонимический словарь [Geographic Names of the World: Toponymic Dictionary] (in Russian). Moscow: Russkiye slovari. p. 104. ISBN 9785892160292.

- ^ Portnov, A. V. (2006). Волинь [Volhynia]. Encyclopedia of Modern Ukraine (in Ukrainian) (Online ed.). Kyiv: NASU Institute of Encyclopaedic Research. ISBN 9789660220744. Archived from the original on 2021-06-30. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Kollmann, Nancy Shields (2000). "The Principalities of Rus' in the Fourteenth Century". In Jones, Michael (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. VI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 764–794. ISBN 9780521362900. Archived from the original on 2021-10-03. Retrieved 2023-02-11 – via Google Books.

- ^ Slutsky, Yehuda (2007). "Pale of Settlement". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.). Macmillan Reference USA. ISBN 9780028660974. Archived from the original on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2021-09-28 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North. Translated by Lunde, Paul; Stone, Caroline. Penguin. 2012. pp. 128, 146, 200. ISBN 9780140455076 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd P. (1953). "Introduction". The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text (PDF). Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America. pp. 3–50. OCLC 268919. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-27 – via MGH-Bibliothek.

- ^ "Wolynien". Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon (in German). Vol. 20 (6th ed.). Leipzig & Vienna: Bibliographisches Institut. 1908. pp. 744–745. OL 7001513M – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Effects of the Volhynian Massacres". Volhynia Massacre. Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2021-05-01. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 346, 359, 363. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

Literature

[edit]- Andriyashev, Alexander (1887). Очерк истории Волынской земли [Essay on the History of Volyn land] (in Russian) at Runivers.ru in Djvu and PDF formats. Kyiv: Imperial University of Saint Vladimir.

- Ciancia, Kathryn (September 2017). "Borderland Modernity: Poles, Jews, and Urban Spaces in Interwar Eastern Poland". The Journal of Modern History. 89 (3): 531–561. doi:10.1086/692992. S2CID 149342133.

- Litwin, Henryk (October 2016). "Central European Superpower". Business Ukraine. pp. 26–29. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. PDF version at the Wayback Machine (archived 2016-11-12).

- Merten, Ulrich (2015). Voices from the Gulag: Oppression of the German Minority in the Soviet Union. Lincoln, NE: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia. ISBN 9780692603376

- Potocki, Jan (1805). Histoire anciènne du gouvernement de Volhynie: pour servir de suite à l'histoire primitive des peuples de la Russie (in French) at Polona. Saint Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences.

External links

[edit]- American Historical Society of Germans from Russia in Lincoln, Nebraska

- GCatholic - Diocese of Lodomeria, Ukraine

- GCatholic - Ukrainian Apostolic Exarchate of Volhynia, Polesia and Pidliashia

- Imperial Russian Volhynia Governorate Map at the Wayback Machine (archived 2014-03-28), from the Roll "Fame" Family Genealogy website

- The Journey to Trochenbrod and Lozisht Aug 2006

- The Society for German Genealogy in Eastern Europe Archived 2019-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- The Swiss Mennonite Cultural & Historical Association

- Volhynia.com

- wolhynien.de (in German)

Volhynia

View on GrokipediaNames and Etymology

Linguistic Origins and Historical Designations

The name Volhynia derives from the Old East Slavic "Volynĭ," denoting a pre-10th-century fortified settlement at the confluence of the Buh and Huchva rivers, supported by archaeological finds of Roman and Arab coins from the 6th–9th centuries.[9] This settlement, identified as the eponymous town of Volyn near modern Volodymyr-Volynskyi, appears in records as early as 1018.[10] The designation is also associated with an extinct city of Volyn or Velyn on the Western Bug River, reflecting one of Europe's earliest Slavic inhabited areas.[11] Early references include the 10th-century Arab geographer Mas’ūdī's "Valinana" for the locale, with locals termed "Dulaba" under a ruler "Vand Slava."[9] Tribal names evolved from the Dulibians—possibly linked to "Dulaba"—to the Buzhanians by the 10th century, alongside emerging Volhynians as regional identifiers.[9] Administrative and linguistic designations shifted with political control: the 12th-century Principality of Volhynia, the 1569–1793 Volhynia Voivodeship under Polish-Lithuanian rule, and the post-1795 Russian Volhynia Governorate (gubernia).[9] Multilingual variants include Polish Wołyń, Russian Волынь (Volyn’), and Ukrainian Волинь (Volyn’), reflecting phonetic adaptations in East Slavic and neighboring tongues without altering the core hydronymic or toponymic root.[11] An alternate historical epithet, Lodomeria, stems from the Slavic name of Volodymyr-Volynskyi, emphasizing key urban centers in medieval nomenclature.[9]Geography

Physical Landscape and Borders

Volhynia encompasses a historical territory primarily in northwestern Ukraine, with portions extending into eastern Poland and southern Belarus, situated between the Prypiat Marshes to the north and the Western Bug River to the west.[1] [12] Its boundaries have fluctuated historically, but the core area aligns roughly with the former Volhynia Governorate established in 1793, which covered approximately 72,900 square kilometers and included 12 counties.[6] [13] The physical landscape features the northern extension of the Volhynian-Podolian Upland, characterized by rolling plains and plateaus with elevations averaging 220–250 meters, rising to maxima around 360 meters in localized ridges. [14] The terrain is underlain by horizontal sedimentary rocks covered by loess deposits, forming undulating watersheds and slopes interspersed with river depressions at 200–220 meters elevation.[14] [15] Major rivers traversing the region include the Styr, Horyn, Ikva, Turiya, and Western Bug, which carve fertile valleys amid forested and marshy lowlands, particularly in the northern Polissia zone.[1] The area hosts over 200 lakes, notably Lake Svitiaz—the largest natural lake in Ukraine at 27.5 square kilometers and up to 58 meters deep—concentrated in the Shatsk Lakes group.[16] These hydrological features contribute to a landscape of mixed woodlands, peat bogs, and alluvial plains suited for agriculture.[17]Climate and Natural Resources

Volhynia's climate is humid continental (Köppen Dfb), featuring cold, snowy winters and warm, humid summers with moderate precipitation throughout the year. In representative locations like Volodymyr-Volynskyi, average January highs reach about -2°C (28°F) and lows -9°C (16°F), while July highs average 24°C (76°F) and lows 13°C (55°F). Annual precipitation totals approximately 650 mm, distributed fairly evenly, supporting lush vegetation but contributing to foggy and overcast conditions, especially in the Polesian Lowland areas. Winters often bring significant snowfall and wind, with occasional thaws prolonging cold periods.[18][19] The region's natural resources emphasize water bodies, forests, and peat deposits rather than abundant minerals. Volhynia contains over 220 lakes, including Lake Svitiaz at 42.5 square kilometers—Ukraine's largest—and spans 130 rivers with 32 reservoirs, enabling fisheries, irrigation, and hydropower potential. Extensive woodlands in the Polesian Lowland provide timber, while peat bogs support extraction for fuel and horticulture across licensed areas exceeding 6,000 hectares. Fertile chernozem and podzol soils in the Volhynian Upland facilitate agriculture, yielding crops such as grains, potatoes, and beets, though amber mining occurs in adjacent areas like Rivne. Limited metallic minerals exist, with emphasis on non-metallic resources like building materials from local quarries.[16][20]History

Medieval Foundations

The region of Volhynia, located in northwestern Ukraine, was initially settled by East Slavic tribes, including the Dulebes (later referred to as Volhynians or Buzhans), who established agricultural communities amid forested lowlands and river valleys by the 6th–7th centuries CE. These tribes engaged in trade along routes connecting the Baltic to the Black Sea, fostering early urban centers like Volodymyr (founded circa 9th century) and Lutsk. Archaeological evidence from hill forts and pottery indicates continuity with pre-Rus' Slavic material culture, though written records are sparse until the 10th century.[21] Incorporation into Kievan Rus' occurred under Vladimir I (r. 980–1015), who subdued local tribes around 988 during the Christianization of Rus', assigning the area as an appanage to kin and integrating it into the federation's western frontier. The Primary Chronicle records conflicts with neighboring Polabian Slavs and Pechenegs, highlighting Volhynia's strategic role in defending against nomad incursions. By the 11th century, under Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054), the region saw fortified settlements and Orthodox church foundations, such as early monasteries, solidifying its administrative status as a principality with Vladimir-Volynskyi as capital.[22][23] The Principality of Volhynia formalized post-1054 amid Rus' fragmentation, ruled by Rurikid branches including Vsevolod Yaroslavich (1073–1093) and later Mstislav I (1125–1132), who expanded territories through alliances and campaigns against Cumans. Economic growth relied on amber trade, grain, and salt from local deposits, supporting a population of freemen, boyars, and smerds. Dynastic feuds, as chronicled in the Hypatian Codex, weakened central authority, setting the stage for Roman Mstislavich's unification with Galicia in 1199, which created the larger Galicia–Volhynia entity enduring Mongol pressures. This merger marked the culmination of Volhynia's medieval consolidation, blending local Slavic governance with broader Rus' traditions.[24][25]Early Modern Integration

The Union of Lublin, signed on July 1, 1569, established the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and transferred Volhynia's territories from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the Polish Crown, initiating deeper administrative and political integration.[26][27] This shift created the Wołyń Voivodeship as an administrative unit within the Crown's Lesser Poland Province, with Lutsk designated as the provincial capital and key centers including Volodymyr and Ostrog organized into powiats (counties).[28] The voivodeship's sejmiks (local assemblies) convened in Lutsk, enabling noble participation in Commonwealth-wide diets while local starostas managed judicial and fiscal affairs under voivodal oversight. Dominant magnate families, such as the Ostrogskis and Zbaraskis, consolidated control over vast estates, fostering economic expansion through latifundia-based agriculture focused on grain production for export.[29] Prince Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski (c. 1526–1608), a leading Ruthenian Orthodox magnate and hetman, exemplified this era's elite, holding titles like voivode of Kyiv and marshal of Volhynia, and amassing wealth equivalent to providing 426 horses for military campaigns.[30] Under such families, Volhynia saw fortified residences like Ostrog Castle and cultural initiatives, including the Ostrog Academy founded in 1576 as an early higher learning institution promoting Orthodox scholarship amid Catholic pressures. Jewish communities, granted settlement privileges, facilitated trade and estate management, enhancing regional connectivity to Gdańsk markets via overland routes.[31] Integration deepened through the nobility's adoption of Polish legal customs, such as the szlachta privileges extended via the 1569 union's Henrician Articles, though Ruthenian Orthodox peasants faced increasing enserfment and cultural marginalization.[32] By the early 17th century, Polish administrative reforms and magnate patronage had transformed Volhynia from a frontier periphery into a core Commonwealth province, albeit with simmering ethnic-religious tensions exacerbated by Union of Brest (1596) conversions.[33] This period's developments laid groundwork for later conflicts, as Cossack unrest in the 1640s challenged the imposed hierarchical order.Imperial Russian and Austrian Rule

Following the Second Partition of Poland in 1793 and the Third in 1795, the bulk of Volhynia was annexed by the Russian Empire, with western fringes incorporated into the Austrian Empire's Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.[34] [35] The Russian portion was initially administered as the Izyaslav Vicegerency from 1793 to 1796 before being reorganized as the Volhynia Governorate in 1796, encompassing about 71,000 square kilometers with Zhytomyr as its capital.[36] [9] The Volhynia Governorate was divided into 12 uyezds, including Zhytomyr, Novohrad-Volynskyi, Ovruch, and Lutsk, and formed part of the Southwestern Krai, with governance emphasizing centralized control and Russification efforts.[37] [36] Serfdom persisted until its abolition in 1861, after which agricultural reforms and state-sponsored colonization attracted over 200,000 German and Czech settlers between the 1860s and 1890s to develop farming on state lands.[38] The population, predominantly Ukrainian peasants with Polish nobility, Jewish urban dwellers, and growing Russian officials, numbered around 2.9 million by 1897, amid policies suppressing Polish and Ukrainian cultural expressions following the 1830-31 and 1863 uprisings.[6] [9] In the Austrian-controlled western areas, integrated into Galicia, policies were comparatively liberal, with earlier serf emancipation in 1848 and greater tolerance for Ukrainian-language publications and institutions, fostering early national awakening among Ruthenians, though these territories represented a minor portion of historical Volhynia.[34] [39] Economic development focused on agriculture and nascent industry, but the region remained peripheral compared to the Russian core, with administration centered in Lviv rather than local Volhynian sites.[40] By the late 19th century, both empires pursued modernization, yet Russian Volhynia experienced stricter Orthodox proselytization and restrictions on Catholicism and Uniatism, contrasting with Austria's multi-confessional approach.[9]World War I and Revolutionary Upheaval

During World War I, the Volhynia Governorate, administered by the Russian Empire, emerged as a critical sector of the Eastern Front due to its strategic position bordering Austrian Galicia. Russian forces initially advanced into Austrian territory in 1914, but sustained engagements intensified in 1916 amid the broader Brusilov Offensive, launched by General Aleksei Brusilov on June 4 against Austro-Hungarian lines in the Galicia-Volhynia region. This operation, the most successful Russian effort of the war, involved coordinated attacks across a 300-mile front, with Volhynia's terrain of forests, rivers, and marshes complicating logistics for both sides.[41][42] The offensive opened with the Battle of Lutsk from June 4 to 6, 1916, where Russian Eighth and Eleventh Armies overwhelmed Austro-Hungarian defenses, capturing the fortified city of Lutsk—Volhynia's administrative center—after three days of heavy artillery barrages and infantry assaults, resulting in over 30,000 Austro-Hungarian casualties and the encirclement of several divisions. Further clashes, including the Battle of Kostiuchnówka on July 4–6, saw Austro-Hungarian forces, bolstered by Polish Legion units under Józef Piłsudski, mount fierce resistance against Russian probes, inflicting significant losses before the offensive stalled due to supply shortages and German reinforcements. Overall, the campaign yielded Russian territorial gains of up to 75 miles in Volhynia but at the cost of approximately 500,000 to 1 million casualties, exacerbating war weariness and contributing to the empire's internal collapse.[43][44][41] The March 1917 February Revolution in Petrograd triggered the rapid disintegration of Russian military cohesion in Volhynia, as mutinies and desertions spread among frontline troops, leaving a power vacuum amid ethnic Ukrainian majorities in the countryside. Local Ukrainian councils (hromadas) proliferated, aligning with the Central Rada in Kyiv, which on June 23, 1917, proclaimed autonomy for Ukrainian-inhabited territories including Volhynia, fostering cultural revival and land reforms but clashing with Bolshevik agitators promoting class struggle over national self-determination. The November 1917 October Revolution escalated tensions, as Bolshevik forces sought to sovietize the region, prompting the Rada to declare the Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) on January 22, 1918, and sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, which temporarily secured Volhynia's inclusion in an independent Ukraine under German protection.[45][46] Post-Brest-Litovsk occupation by Central Powers forces stabilized Volhynia briefly, but the German defeat in November 1918 unleashed renewed chaos, with UNR armies withdrawing amid Bolshevik incursions and rising Polish irredentist claims to historically Polish-settled areas. In the ensuing Ukrainian-Soviet War (1917–1921), Volhynia served as a contested buffer, witnessing skirmishes between UNR forces, Red Army units, and White Russian remnants, compounded by peasant uprisings against requisitioning. Polish forces, advancing from the west during the Polish-Ukrainian War of late 1918–1919, secured limited footholds in eastern Volhynia despite Ukrainian resistance, though major fighting concentrated in Galicia; by 1920, UNR leader Symon Petliura's alliance with Poland via the Warsaw Pact of April 21 ceded Polish claims to western Volhynia in exchange for joint anti-Bolshevik operations.[45][47] The Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921) culminated in decisive battles across Volhynia, where Polish armies under Józef Piłsudski pushed eastward in May–July 1919, capturing Rivne and surrounding areas from Bolshevik control, only to face counteroffensives that recaptured much of the territory by summer 1920. Ukrainian detachments allied with Poland conducted auxiliary raids but lacked capacity for independent operations in Volhynia, where local Bolshevik committees had consolidated support among Russian-speaking workers and landless peasants. The conflict's resolution via the Treaty of Riga on March 18, 1921, assigned the bulk of Volhynia—approximately 35,000 square kilometers—to the re-established Second Polish Republic, incorporating its mixed Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish populations under Polish administration, while eastern fringes fell to Soviet Ukraine, marking the end of revolutionary fluidity and the onset of interwar border stabilization.[47][45]Interwar Polish Administration

Following the Polish-Soviet War, the Treaty of Riga on March 18, 1921, confirmed Polish sovereignty over Volhynia, establishing the Wołyń Voivodeship as a frontier province of the Second Polish Republic with an area of 35,754 square kilometers and capital at Lutsk.) The voivodeship encompassed 22 powiats (counties) and served as a buffer against Soviet influence, prompting centralized administration under appointed voivodes reporting to Warsaw. Henryk Józewski, voivode from 1928 to 1938, implemented the "Volhynian experiment," a policy emphasizing cultural autonomy for Ukrainians, promotion of a distinct "Volhynian" identity separate from Galician Ukrainian nationalism, and cooperation with moderate Ukrainian elites to counter radicalism and Bolshevism. Land reform, initiated under the July 1920 act and intensified in the east, redistributed estates exceeding 180 hectares, prioritizing Polish military veterans known as osadnicy who received plots averaging 10-20 hectares to secure the border and develop agriculture.[48] By the mid-1930s, approximately 15,000 osadnik families settled in Wołyń, often on former Russian state or Ukrainian noble lands, fostering resentment among local Ukrainian peasants who comprised the majority and faced limited access to redistributed parcels.[48] This policy, while boosting Polish demographic presence from about 10% in 1921 to 17% by the 1931 census, exacerbated ethnic tensions, as Ukrainian organizations viewed it as colonization displacing indigenous smallholders. The voivodeship's economy remained predominantly agrarian, with over 80% of the 2.08 million inhabitants in 1931 engaged in farming, though infrastructure investments transformed connectivity.[49] Rail lines expanded from 800 kilometers in 1921 to over 1,200 by 1939, linking Lutsk to Warsaw and facilitating timber and grain exports, while road networks grew to support military mobility and settlement.) Education advanced under Polish auspices, with primary schools increasing to 2,000 by 1938, though Ukrainian-language instruction was curtailed outside Józewski's tenure, contributing to literacy rates lagging at 52% versus the national 77%.[49] These developments modernized the region but prioritized Polish cultural dominance, limiting Ukrainian political expression and sowing seeds for interethnic strife.World War II Ethnic Conflicts

During the Nazi occupation of Volhynia from 1941 to 1944, ethnic tensions between the Polish minority and Ukrainian majority intensified amid wartime chaos, leading to systematic violence primarily perpetrated by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), the armed wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-Bandera faction). The UPA, seeking to establish an ethnically homogeneous Ukrainian state free of Polish presence, initiated targeted killings of Polish civilians starting in late 1942, escalating to coordinated massacres in 1943. These actions were ordered by UPA commander Dmytro Klyachkivsky, who issued directives in March 1943 for the "liquidation of the Polish element" in Volhynia through destruction of Polish settlements and extermination of inhabitants.[50] The violence peaked during "Bloody Sunday" on July 11, 1943, when UPA units simultaneously attacked over 100 Polish villages and settlements, killing thousands, including in localities such as Kisielin (90 killed during Mass) and Wola Ostrowiecka (hundreds mutilated with farm tools).[51][52] The massacres employed brutal methods, including axes, scythes, and firearms, with victims—predominantly women, children, and elderly—often tortured or burned alive; eyewitness accounts document systematic house-to-house searches and communal executions. Estimates place Polish deaths in Volhynia at 40,000 to 60,000 between February 1943 and late 1944, with total casualties across Volhynia and adjacent Eastern Galicia reaching 100,000.[53][50] Ukrainian civilian deaths from Polish self-defense actions and retaliatory operations by the Polish Home Army (AK) and peasant battalions numbered 10,000 to 20,000, though these were largely reactive to UPA offensives and did not match the scale or premeditation of the initial ethnic cleansing campaign.[54] Soviet partisans also clashed with both groups, exacerbating the conflict, while Nazi forces sporadically exploited divisions but did not directly orchestrate the Polish-Ukrainian clashes. The underlying causes stemmed from OUN-B ideology, which viewed Poles as historical oppressors and obstacles to Ukrainian independence, compounded by interwar Polish settlement policies and land expropriations that fueled Ukrainian grievances. However, the UPA's actions represented a deliberate shift to genocide-like ethnic purification rather than mere wartime reprisals, as evidenced by internal orders bypassing military targets in favor of civilian annihilation. By early 1944, as Soviet forces advanced, the violence subsided in Volhynia, but the massacres depopulated Polish communities, forcing survivors to flee eastward or join self-defense units like those in Wolyn, which fortified villages against further attacks.[50] The events strained Polish-Ukrainian relations for decades, with Polish authorities classifying them as genocide, while some Ukrainian narratives frame them as mutual conflict amid broader anti-fascist resistance.[51][54]Postwar Soviet Incorporation and Modern Independence

Following the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Volhynia was formally incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic within the Soviet Union, with the region's eastern borders adjusted to include former Polish territories east of the Curzon Line.[38] This annexation, building on the 1939 Soviet invasion of eastern Poland, resulted in the establishment of Volyn Oblast as an administrative unit in Soviet Ukraine, encompassing most of historical Volhynia.[6] Soviet authorities implemented rapid collectivization of agriculture starting in the late 1940s, seizing private landholdings and enforcing collective farms, which disrupted traditional farming patterns and led to food shortages in rural areas.[55] A key aspect of postwar consolidation was the forced population exchange mandated by the Soviet-Polish treaty of September 9, 1944, executed between 1944 and 1946.[56] This involved the repatriation of approximately 1.1 million ethnic Poles from Soviet-controlled territories, including Volhynia, to postwar Poland, often under coercive conditions with limited possessions allowed.[57] In exchange, around 480,000 Ukrainians and Lemkos from southeastern Poland were resettled into Volhynia and adjacent areas, fundamentally altering the ethnic composition to a Ukrainian majority of over 95% by 1950.[58] These transfers, framed by Soviet authorities as voluntary but involving NKVD oversight and violence, eliminated significant Polish communities and facilitated homogenization, though they exacerbated local resentments.[55] [57] Soviet security forces conducted anti-insurgent operations against remnants of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in Volhynia, which persisted in guerrilla activities until the mid-1950s.[59] Deportations targeted suspected nationalists, with tens of thousands from western Ukraine, including Volhynia, exiled to Siberia and Central Asia between 1947 and 1952 as part of broader pacification efforts like Operation West in 1947, which displaced over 77,000 individuals.[58] These measures suppressed Ukrainian cultural and religious institutions, including the Greek Catholic Church, which was forcibly merged into the Russian Orthodox Church in 1946, while promoting Russification through education and administration.[59] Ukraine's declaration of independence on August 24, 1991, from the dissolving Soviet Union marked the end of direct Moscow control over Volhynia.[60] This was ratified by a national referendum on December 1, 1991, in which 96.32% of Volyn Oblast voters approved independence, reflecting strong regional support amid economic collapse and Gorbachev's failed reforms.[61] Post-1991, Volyn Oblast transitioned to Ukrainian sovereignty, with gradual de-Russification, including the reestablishment of Ukrainian-language education and local governance, though economic reliance on agriculture persisted amid challenges like rural depopulation.[62]Demographics and Society

Historical Ethnic Composition

In the medieval period, Volhynia was primarily inhabited by East Slavic populations referred to as Ruthenians, who constituted the rural peasantry and formed the demographic core of the principalities. Polish and Lithuanian nobles began settling in significant numbers following the Union of Krewo in 1385 and subsequent unions, establishing a landowning elite amid the predominantly Ruthenian base. Jewish communities emerged in urban centers during this era, often as merchants and artisans under royal privileges granted from the 14th century onward.[35] Under Russian imperial rule in the 19th century, the ethnic composition remained Ukrainian-majority in rural areas, but saw targeted settlement policies attracting ethnic Germans, Czechs, and some Poles to underutilized lands. Approximately 200,000 German, Czech, and Polish farmers settled in Volhynia from the mid-19th century, forming compact colonies focused on agriculture. By 1897, German-speakers totaled 171,331, or 5.73% of the gubernia's population, primarily Lutherans and Baptists from Prussian provinces. Jews comprised a notable urban minority, numbering 174,457 in 1847, concentrated in towns where they often dominated trade and small industry. Poles maintained influence through remaining nobility and clergy, though their share declined relative to the growing Ukrainian peasantry.[63][64][35] The interwar Wołyń Voivodeship, under Polish administration, had a total population of slightly over 2 million according to the 1931 census, with Ukrainians forming the vast majority at around 68%. Poles accounted for approximately 16-18%, primarily in administrative roles, larger towns, and estates; Jews about 9-10% in shtetls and commerce; and smaller minorities including Russians (3-4%), Germans (2%), and Czechs (1%). These figures reflect language and religion as proxies for ethnicity, with Ukrainian speakers (including some classified as Ruthenian) dominant in the countryside.| Group | Approximate Share (1931) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 68% | Rural majority; language-based count |

| Poles | 16-18% | Urban and elite presence |

| Jews | 9-10% | Town dwellers; Yiddish speakers |

| Russians | 3-4% | Often officials or settlers |

| Germans/Czechs | 3% combined | Agricultural colonists |

_башта_замку_Луцьк.jpg/250px-В'їзна_(Надбрамна)_башта_замку_Луцьк.jpg)

_башта_замку_Луцьк.jpg/2000px-В'їзна_(Надбрамна)_башта_замку_Луцьк.jpg)