Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

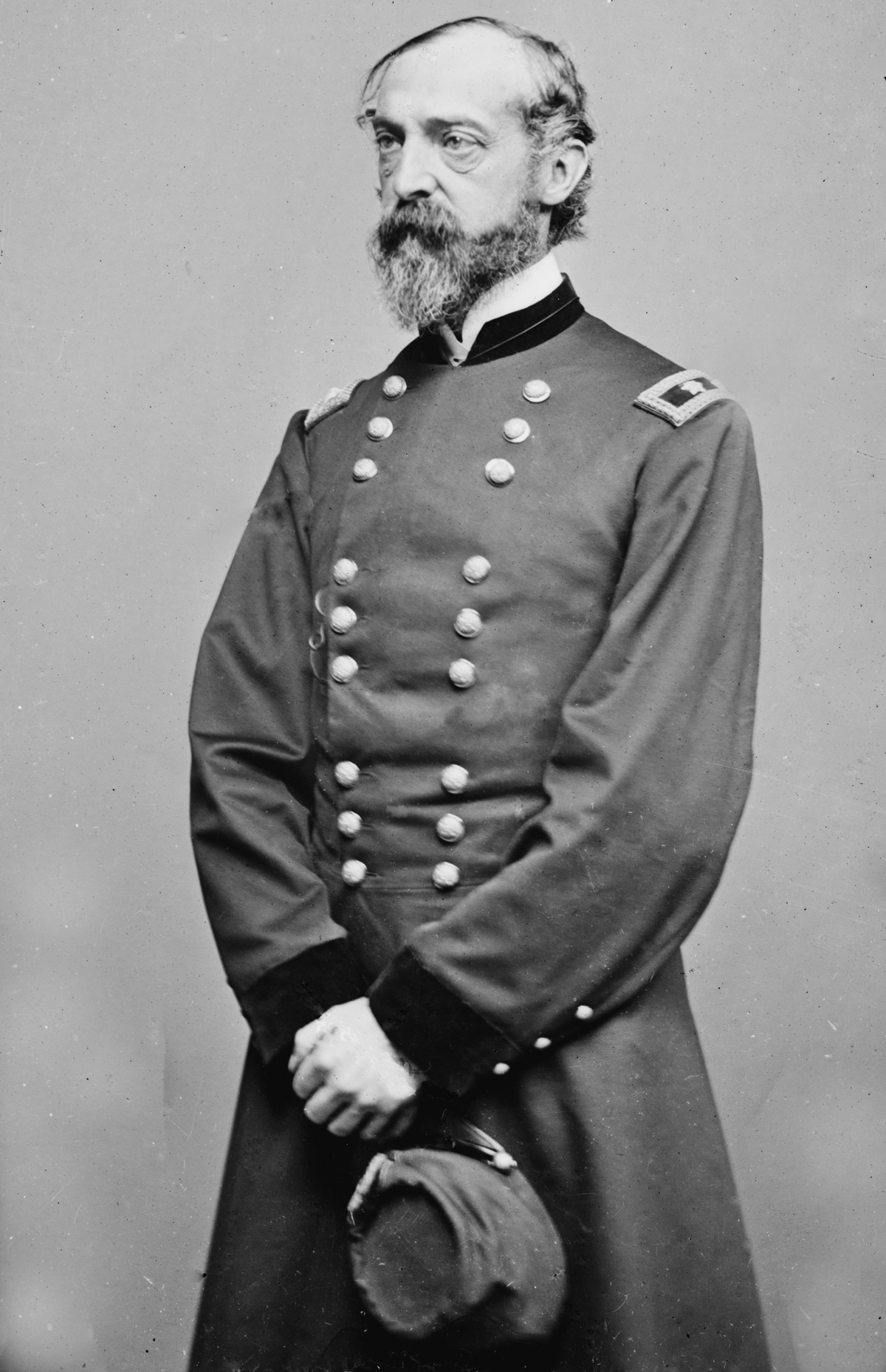

George Meade

View on Wikipedia

George Gordon Meade (December 31, 1815 – November 6, 1872) was an American military officer who served in the United States Army and the Union army as a major general in command of the Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War from 1863 to 1865. He fought in many of the key battles of the eastern theater and defeated the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia led by General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Key Information

He was born in Cádiz, Spain, to a wealthy Philadelphia merchant family and graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1835. He fought in the Second Seminole War and the Mexican–American War. He served in the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers and directed construction of lighthouses in Florida and New Jersey from 1851 to 1856 and the United States Lake Survey from 1857 to 1861.

His Civil War service began as brigadier general with the Pennsylvania Reserves, building defenses around Washington, D.C. He fought in the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days Battles. He was severely wounded at the Battle of Glendale and returned to lead his brigade at the Second Battle of Bull Run. As a division commander, he won the Battle of South Mountain and assumed temporary command of the I Corps at the Battle of Antietam. Meade's division broke through the lines at the Battle of Fredericksburg but were forced to retreat due to lack of support. Meade was promoted to major general and commander of the V Corps, which he led during the Battle of Chancellorsville.

He was appointed to command the Army of the Potomac just three days before the Battle of Gettysburg and arrived on the battlefield after the first day's action on July 1, 1863. He organized his forces on favorable ground to fight an effective defensive battle against Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and repelled a series of massive assaults throughout the next two days. While elated about the victory, President Abraham Lincoln was critical of Meade due to his perception of an ineffective pursuit during the retreat, which allowed Lee and his army to escape back to Virginia. That fall, Meade's troops had a minor victory in the Bristoe Campaign but a stalemate at the Battle of Mine Run. Meade's cautious approach prompted Lincoln to look for a new commander of the Army of the Potomac.

In 1864–1865, Meade continued to command the Army of the Potomac through the Overland Campaign, the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign, and the Appomattox Campaign, but he was overshadowed by the direct supervision of the general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who accompanied him throughout these campaigns. Grant conducted most of the strategy during these campaigns, leaving Meade with significantly less influence than before. After the war, Meade commanded the Military Division of the Atlantic from 1865 to 1866 and again from 1869 to 1872. He oversaw the formation of the state governments and reentry into the United States for five southern states through his command of the Department of the South from 1866 to 1868 and the Third Military District in 1872. Meade was subjected to intense political rivalries within the Army, notably with Major Gen. Daniel Sickles, who tried to discredit Meade's role in the victory at Gettysburg. He had a notoriously short temper which earned him the nickname of "Old Snapping Turtle".

Early life and education

[edit]Meade was born on December 31, 1815, in Cádiz, Spain,[1] the eighth of ten children of Richard Worsam Meade and Margaret Coats Butler.[2] His grandfather Irishman George Meade was a wealthy merchant and land speculator in Philadelphia.[3] His father was wealthy due to Spanish-American trade and was appointed U.S. naval agent.[2] He was ruined financially because of his support of Spain in the Peninsular War; his family returned to the United States in 1817, in precarious financial straits.[4]

Meade attended elementary school in Philadelphia[5] and the American Classical and Military Lyceum, a private school in Philadelphia modeled after the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.[6] His father died in 1828 when George was 12 years old[4] and he was taken out of the Germantown military academy. George was placed in a school run by Salmon P. Chase in Washington, D.C.; however, it closed after a few months due to Chase's other obligations. He was then placed in the Mount Hope Institution in Baltimore, Maryland.[7]

Meade entered the United States Military Academy at West Point on July 1, 1831.[8] He would have preferred to attend college and study law and did not enjoy his time at West Point.[9] He graduated 19th in his class of 56 cadets in 1835.[10] He was uninterested in the details of military dress and drills and accumulated 168 demerits, only 32 short of the amount that would trigger a mandatory dismissal.[11]

Topographical Corps and Mexican-American War

[edit]

Meade was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 3rd Artillery.[12] He worked for a summer as an assistant surveyor on the construction of the Long Island Railroad and was assigned to service in Florida.[13] He fought in the Second Seminole War[14] and was assigned to accompany a group of Seminole to Indian territory in the West.[13] He became a full second lieutenant by year's end, and in the fall of 1836, after the minimum required one year of service,[11] he resigned from the army. He returned to Florida and worked as a private citizen for his brother-in-law, James Duncan Graham, as an assistant surveyor to the United States Army Corps of Topographical Engineers on a railroad project.[15] He conducted additional survey work for the Topographical Engineers on the Texas-Louisiana border, the Mississippi River Delta[16] and the northeastern boundary of Maine and Canada.[17]

In 1842, a congressional measure was passed that excluded civilians from working in the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers[18] and Meade reentered the army as a second lieutenant in order to continue his work with them.[19] In November 1843, he was assigned to work on lighthouse construction under Major Hartman Bache. He worked on the Brandywine Shoal lighthouse in the Delaware Bay.[20]

Meade served in the Mexican–American War and was assigned to the staffs of Generals Zachary Taylor[21] and Robert Patterson.[22] He fought at the Battle of Palo Alto,[23] the Battle of Resaca de la Palma[24] and the Battle of Monterrey.[25] He served under General William Worth at Monterrey and led a party up a hill to attack a fortified position.[26] He was brevetted to first lieutenant[25] and received a gold-mounted sword for gallantry from the citizens of Philadelphia.[27]

In 1849, Meade was assigned to Fort Brooke in Florida to assist with Seminole attacks on settlements.[28] In 1851, he led the construction of the Carysfort Reef Light in Key Largo.[29] In 1852, the Topographical Corps established the United States Lighthouse Board and Meade was appointed the Seventh District engineer with responsibilities in Florida. He led the construction of Sand Key Light in Key West;[30] Jupiter Inlet Light in Jupiter, Florida; and Sombrero Key Light in the Florida Keys.[31] When Bache was reassigned to the West Coast, Meade took over responsibility for the Fourth District in New Jersey and Delaware[32] and built the Barnegat Light on Long Beach Island,[33] Absecon Light in Atlantic City, and the Cape May Light in Cape May. He also designed a hydraulic lamp that was used in several American lighthouses. Meade received an official promotion to first lieutenant in 1851,[32] and to captain in 1856.[34]

In 1857, Meade was given command of the Lakes Survey mission of the Great Lakes. Completion of the survey of Lake Huron and extension of the surveys of Lake Michigan down to Grand and Little Traverse Bays were done under his command.[35] Prior to Captain Meade's command, Great Lakes' water level readings were taken locally with temporary gauges; a uniform plane of reference had not been established. In 1858, based on his recommendation, instrumentation was set in place for the tabulation of records across the basin.[36] Meade stayed with the Lakes Survey until the 1861 outbreak of the Civil War.[37]

American Civil War

[edit]Meade was appointed brigadier general of volunteers on August 31, 1861,[38] a few months after the start of the American Civil War, based on the strong recommendation of Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin.[39] He was assigned command of the 2nd Brigade of the Pennsylvania Reserves under General George A. McCall.[40] The Pennsylvania Reserves were initially assigned to the construction of defenses around Washington, D.C.[25]

Peninsula campaign

[edit]In March 1862, the Army of the Potomac was reorganized into four corps,[41] Meade served as part of the I Corps under Maj. Gen Irvin McDowell.[25] The I Corps was stationed in the Rappahannock area, but in June, the Pennsylvania Reserves were detached and sent to the Peninsula to reinforce the main army.[42] With the onset of the Seven Days Battles on June 25, the Reserves were directly involved in the fighting. At Mechanicsville and Gaines Mill, Meade's brigade was mostly held in reserve,[43] but at Glendale on June 30, the brigade was in the middle of a fierce battle. His brigade lost 1,400 men[44] and Meade was shot in the right arm and through the back.[45] He was sent home to Philadelphia to recuperate.[46] Meade resumed command of his brigade in time for the Second Battle of Bull Run, then assigned to Major General Irvin McDowell's corps of the Army of Virginia. His brigade made a heroic stand on Henry House Hill to protect the rear of the retreating Union Army.[47]

Maryland campaign

[edit]The division's commander John F. Reynolds was sent to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to train militia units and Meade assumed temporary division command at the Battle of South Mountain[48] and the Battle of Antietam.[49] Under Meade's command, the division successfully attacked and captured a strategic position on high ground near Turner's Gap held by Robert E. Rodes' troops which forced the withdrawal of other Confederate troops.[50] When Meade's troops stormed the heights, the corps commander Joseph Hooker, exclaimed, "Look at Meade! Why, with troops like those, led in that way, I can win anything!"[51]

On September 17, 1862,[52] at Antietam, Meade assumed temporary command of the I Corps and oversaw fierce combat after Hooker was wounded and requested Meade replace him.[53] On September 29, 1862, Reynolds returned from his service in Harrisburg. Reynolds assumed command of the I Corps and Meade assumed command of the Third Division.[54]

Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville

[edit]

On November 5, 1862, Ambrose Burnside replaced McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside gave command of the I Corps to Reynolds, which frustrated Meade as he had more combat experience than Reynolds.[55]

Meade was promoted to major general of the Pennsylvania Reserves on November 29, 1862, and given command of a division in the "Left Grand Division" under William B. Franklin.[55] During the Battle of Fredericksburg, Meade's division made the only breakthrough of the Confederate lines, spearheading through a gap in Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's corps at the southern end of the battlefield. However, his attack was not reinforced, which resulted in the loss of much of his division.[56] He led the Center Grand Division through the Mud March and stationed his troops on the banks of the Rappahanock.[57]

On December 22, 1862, Meade replaced Daniel Butterfield in command of the V Corps which he led in the Battle of Chancellorsville. On January 26, 1863, Joseph Hooker assumed command of the Army of the Potomac.[55] Hooker had grand plans for the Battle of Chancellorsville, but was unsuccessful in execution, allowing the Confederates to seize the initiative. After the battle, Meade wrote to his wife that, "General Hooker has disappointed all his friends by failing to show his fighting qualities in a pinch."[58]

Meade's corps was left in reserve for most of the battle, contributing to the Union defeat. Meade was among Hooker's commanders who argued to advance against Lee, but Hooker chose to retreat.[59] Meade learned afterward that Hooker misrepresented his position on the advance and confronted him. All of Hooker's commanders supported Meade's position except Dan Sickles.[60]

Gettysburg campaign

[edit]In June 1863, Lee took the initiative and moved his Army of Northern Virginia into Maryland and Pennsylvania.[61] Hooker responded rapidly and positioned the Army of the Potomac between Lee's army and Washington D.C. However, the relationship between the Lincoln administration and Hooker had deteriorated due to Hooker's poor performance at Chancellorsville.[62] Hooker requested additional troops be assigned from Harper's Ferry to assist in the pursuit of Lee in the Gettysburg Campaign. When Lincoln and General in Chief Henry Halleck refused, Hooker resigned in protest.[63]

Command of the Army of the Potomac

[edit]In the early morning hours of June 28, 1863, a messenger from President Abraham Lincoln arrived to inform Meade of his appointment as Hooker's replacement.[64] Upon being woken up, he'd assumed that army politics had caught up to him and that he was under arrest, only to find that he'd been given leadership of the Army of the Potomac.

He had not actively sought command and was not the president's first choice. John F. Reynolds, one of four major generals who outranked Meade in the Army of the Potomac, had earlier turned down the president's suggestion that he take over.[65] Three corps commanders, John Sedgwick, Henry Slocum, and Darius N. Couch, recommended Meade for command of the army and agreed to serve under him despite outranking him.[66] While his colleagues were excited for the change in leadership, the soldiers in the Army of the Potomac were uncertain of Meade since his modesty and lack of theatrical and scholarly demeanor did not match their expectations for a General.[67]

Meade assumed command of the Army of the Potomac on June 28, 1863.[68] In a letter to his wife, Meade wrote that command of the army was "more likely to destroy one's reputation then to add to it."[69]

Battle of Gettysburg

[edit]

Meade rushed the remainder of his army to Gettysburg and deployed his forces for a defensive battle.[70] Meade was only four days into his leadership of the Army of the Potomac and informed his corps commanders that he would provide quick decisions and entrust them with the authority to carry out those orders the best way they saw fit. He also made it clear that he was counting on the corps commanders to provide him with sound advice on strategy.[70]

Since Meade was new to high command, he did not remain in headquarters but constantly moved about the battlefield, issuing orders and ensuring that they were followed. Meade gave orders for the Army of the Potomac to move forward in a broad front to prevent Lee from flanking them and threatening the cities of Baltimore and Washington, D.C. He also issued a conditional plan for a retreat to Pipe Creek in Maryland in case things went poorly for the Union. By 6 pm on the evening of July 1, 1863, Meade sent a telegram to Washington informing them of his decision to concentrate forces and make a stand at Gettysburg.[71]

On July 2, 1863, Meade continued to monitor and maintain the placement of the troops. He was outraged when he discovered that Daniel Sickles had moved his Corps one mile forward to high ground without Meade's permission and left a gap in the line which threatened Sickles' right flank. Meade recognized that Little Round Top was critical to maintaining the left flank. He sent chief engineer Gouverneur Warren to determine the status of the hill and quickly issued orders for the V Corps to occupy it when it was discovered empty. Meade continued to reinforce the troops defending Little Round Top from Longstreet's advance and suffered the near destruction of thirteen brigades. One questionable decision Meade made that day was to order Slocum's XII Corps to move from Culp's Hill to the left flank, which allowed Confederate troops to temporarily capture a portion of it.[71]

On the evening of July 2, 1863, Meade called a "council of war" consisting of his top generals. The council reviewed the battle to date and agreed to keep fighting in a defensive position.[72]

On July 3, 1863, Meade gave orders for the XII Corps and XI Corps to retake the lost portion of Culp's Hill and personally rode the length of the lines from Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top to inspect the troops. His headquarters were in the Leister House directly behind Cemetery Ridge, which exposed it to the 150-gun cannonade that began at 1 pm. The house came under direct fire from incorrectly targeted Confederate guns; Butterfield was wounded, and sixteen horses tied up in front of the house were killed. Meade did not want to vacate the headquarters and make it more difficult for messages to find him, but the situation became too dire and the house was evacuated.[71]

During the three days, Meade made excellent use of capable subordinates, such as Maj. Gens. John F. Reynolds and Winfield S. Hancock, to whom he delegated great responsibilities.[73] He reacted swiftly to fierce assaults on his line's left and right, which culminated in Lee's disastrous assault on the center, known as Pickett's Charge.[74]

By the end of three days of fighting, the Army of the Potomac's 60,000 troops and 30,000 horses had not been fed in three days and were weary from fighting.[75] On the evening of July 4, 1863, Meade held a second council of war with his top generals, minus Hancock and Gibbon, who were absent due to duty and injury. The council reviewed the status of the army and debated staying in place at Gettysburg versus chasing the retreating Army of Northern Virginia. The council voted to remain in place for one day to allow for rest and recovery and then set out after Lee's army. Meade sent a message to Halleck stating, "I make a reconnaissance to-morrow, to ascertain what the intention of the enemy is … should the enemy retreat, I shall pursue him on his flanks."[76]

Lee's retreat

[edit]On July 4, it was observed that the Confederate Army was forming a new line near the nearby mountains after pulling back their left flank, but by July 5 it was clear that they were making a retreat, leaving Meade and his men to tend to the wounded and fallen soldiers until July 6, when Meade ordered his men to Maryland.[77]

Meade was criticized by President Lincoln and others for not aggressively pursuing the Confederates during their retreat.[78] Meade's perceived caution stemmed from three causes: casualties and exhaustion of the Army of the Potomac, which had engaged in forced marches and heavy fighting for a week, heavy general officer casualties that impeded effective command and control, and a desire to guard a hard-won victory against a sudden reversal.[79] Halleck informed Meade of the president's dissatisfaction, which infuriated Meade that politicians and non-field-based officers were telling him how to fight the war. He wrote back and offered to resign his command, but Halleck refused the resignation and clarified that his communication was not meant as a rebuke but an incentive to continue the pursuit of Lee's army.[80]

At one point, the Army of Northern Virginia was trapped with its back to the rain-swollen, almost impassable Potomac River; however, the Army of Northern Virginia was able to erect strong defensive positions before Meade, whose army had also been weakened by the fighting, could organize an effective attack.[81] Lee knew he had the superior defensive position and hoped that Meade would attack and the resulting Union Army losses would dampen the victory at Gettysburg. By July 14, 1863, Lee's troops built a temporary bridge over the river and retreated into Virginia.[79]

Meade was rewarded for his actions at Gettysburg by a promotion to brigadier general in the regular army on July 7, 1863, and the Thanks of Congress,[82] which commended Meade "... and the officers and soldiers of the Army of the Potomac, for the skill and heroic valor which at Gettysburg repulsed, defeated, and drove back, broken and dispirited, beyond the Rappahannock, the veteran army of the rebellion."[83]

Meade wrote the following to his wife after meeting President Lincoln:

"Yesterday I received an order to repair to Washington, to see the President. ... The President was, as he always is, very considerate and kind. He found no fault with my operations, although it was very evident he was disappointed that I had not got a battle out of Lee. He coincided with me that there was not much to be gained by any farther advance; but General Halleck was very urgent that something should be done, but what that something was he did not define. As the Secretary of War was absent in Tennessee, final action was postponed till his return."[84]

Bristoe and Mine Run campaign

[edit]

During the fall of 1863, the Army of the Potomac was weakened by the transfer of the XI and XII Corps to the western theater.[85] Meade felt pressure from Halleck and the Lincoln administration to pursue Lee into Virginia, but he was cautious due to a misperception that Lee's Army was 70,000 in size when the reality was they were only 55,000 compared to the Army of the Potomac at 76,000. Many of the Union troop replacements for the losses suffered at Gettysburg were new recruits, and it was uncertain how they would perform in combat.[86]

Lee petitioned Jefferson Davis to allow him to take the offensive against the cautious Meade, which would also prevent further Union troops from being sent to the western theater to support William Rosencrans at the Battle of Chickamauga.[87]

The Army of the Potomac was stationed along the north bank of the Rapidan River and Meade made his headquarters in Culpeper, Virginia.[88] In the Bristoe Campaign, Lee attempted to flank the Army of the Potomac and force Meade to move north of the Rappahannock River.[89] The Union forces had deciphered the Confederate semaphore code. This, along with spies and scouts, gave Meade advance notice of Lee's movements.[90] As Lee's troops moved north to the west of the Army of the Potomac, Meade abandoned his headquarters at Culpeper and gave orders for his troops to move north to intercept Lee.[91] Meade successfully outmaneuvered Lee in the campaign and gained a small victory. Lee reported that his plans failed due to the quickness of Meade's redeployment of resources.[92] However, Meade's inability to stop Lee from approaching the outskirts of Washington prompted Lincoln to look for another commander of the Army of the Potomac.[93]

In late November 1863, Meade planned one last offensive against Lee before winter weather limited troop movement. In the Mine Run Campaign, Meade attempted to attack the right flank of the Army of Northern Virginia south of the Rapidan River, but the maneuver failed due to the poor performance of William H. French.[94] There was heavy skirmishing, but a full attack never occurred. Meade determined that the Confederate forces were too strong[95] and was convinced by Warren that an attack would have been suicidal.[96] Meade held a council of war, which concluded to withdraw across the Rapidan River during the night of December 1, 1863.[97]

Overland campaign

[edit]1864 was an election year, and Lincoln understood that the fate of his reelection lay in the Union Army's success against the Confederates. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, fresh off his success in the western theater, was appointed commander of all Union armies in March 1864.[98] In his meeting with Lincoln, Grant was told he could select who he wanted to lead the Army of the Potomac. Edwin M. Stanton, the Secretary of War, told Grant, "You will find a very weak, irresolute man there and my advice to you is to replace him at once."[99]

Meade offered to resign[100] and stated the task at hand was of such importance that he would not stand in the way of Grant choosing the right man for the job and offered to serve wherever placed. Grant assured Meade he had no intentions of replacing him.[101] Grant later wrote that this incident gave him a more favorable opinion of Meade than the great victory at Gettysburg. Grant knew that Meade disapproved of Lincoln's strategy and was unpopular with politicians and the press. Grant was not willing to allow him free command of the Army of the Potomac without direct supervision.[102]

Grant's orders to Meade before the Overland Campaign were direct and to the point. He stated, "Lee's army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also."[103] On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac left its winter encampment and crossed the Rapidan River. Meade and Grant both believed that Lee would retreat to the North Anna River or to Mine Run. Lee had received intelligence about the movements of the Army of the Potomac and countered with a move to the East and met the Union Army at the Wilderness.[104] Meade ordered Warren to attack with his whole Corps and had Hancock reinforce with his II Corps.[105] Meade ordered additional Union troops to join the battle, but they struggled to maintain formation and communicate with each other in the thick woods of the Wilderness.[106] After three days of brutal fighting and the loss of 17,000 men, the Union Army called it a draw, and Meade and Grant moved with their forces south toward Spotsylvania Court House to place the Union Army between Lee's forces and Richmond in the hopes of drawing them out to open field combat.[107]

The Union Army moved ponderously slowly toward its new positions, and Meade lashed out at Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan and his cavalry corps blamed them for not clearing the road and not informing Meade of the enemy's movements.[108] Grant had brought Sheridan with him from the western theater, and he found the Army of the Potomac's cavalry corps run down and in poor discipline. Meade and Sheridan clashed over the use of cavalry since the Army of the Potomac had historically used cavalry as couriers, scouting and headquarters guards.[109] Sheridan told Meade that he could "whip Stuart" if Meade let him. Meade reported the conversation to Grant, thinking he would reprimand the insubordinate Sheridan,[108] but he replied, "Well, he generally knows what he is talking about. Let him start right out and do it."[110] Meade deferred to Grant's judgment and issued orders to Sheridan to "proceed against the enemy's cavalry" and, from May 9 through May 24, sent him on a raid toward Richmond, directly challenging the Confederate cavalry.[111] Sheridan's cavalry had great success, they broke up the Confederate supply lines, liberated hundreds of Union prisoners, mortally wounded Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart and threatened the city of Richmond.[112] However, his departure left the Union Army blind to enemy movements.[113]

Grant made his headquarters with Meade for the remainder of the war, which caused Meade to chafe at the close supervision he received. A newspaper reported the Army of the Potomac was, "directed by Grant, commanded by Meade, and led by Hancock, Sedgwick and Warren."[114] Following an incident in June 1864, in which Meade disciplined reporter Edward Cropsey from The Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper for an unfavorable article, all of the press assigned to his army agreed to mention Meade only in conjunction with setbacks. Meade apparently knew nothing of this arrangement, and the reporters giving all of the credit to Grant angered Meade.[115]

Additional differences caused further friction between Grant and Meade. Waging a war of attrition in the Overland Campaign against Lee, Grant was willing to suffer previously unacceptable losses with the knowledge that the Union Army had replacement soldiers available, whereas the Confederates did not.[116] Meade was opposed to Grant's recommendations to directly attack fortified Confederate positions which resulted in huge losses of Union soldiers.[117] Grant became frustrated with Meade's cautious approach and despite his initial promise to allow Meade latitude in his command, Grant began to override Meade and order the tactical deployment of the Army of the Potomac.[118]

Meade became frustrated with his lack of autonomy, and his performance as a military leader suffered.[119] During the Battle of Cold Harbor, Meade inadequately coordinated the disastrous frontal assault.[120] However, Meade took some satisfaction that Grant's overconfidence at the start of the campaign against Lee had been reduced after the brutal confrontation of the Overland Campaign and stated, "I think Grant has had his eyes opened, and is willing to admit now that Virginia and Lee's army is not Tennessee and [Braxton] Bragg's army."[121]

After the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Grant requested that Meade be promoted to major general of the regular army. In a telegram to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on May 13, 1864, Grant stated that "Meade has more than met my most sanguine expectations. He and [William T.] Sherman are the fittest officers for large commands I have come in contact with."[122][123] Meade felt slighted that his promotion was processed after that of Sherman and Sheridan, the latter his subordinate.[124][125] The U.S. Senate confirmed Sherman and Sheridan on January 13, 1865, and Meade on February 1. Subsequently, Sheridan was promoted to lieutenant general over Meade on March 4, 1869, after Grant became president and Sherman became the commanding general of the U.S. Army. However, his date of rank meant that he was outranked at the end of the war only by Grant, Halleck, and Sherman.[126]

Richmond-Petersburg campaign

[edit]Meade and the Army of the Potomac crossed the James River to attack the strategic supply route centered on Petersburg, Virginia. They probed the defenses of the city, and Meade wrote, "We find the enemy, as usual, in a very strong position, defended by earthworks, and it looks very much as if we will have to go through a siege of Petersburg before entering on a siege of Richmond."[127]

An opportunity opened up to lead the Army of the Shenandoah, to protect Washington D.C. against the raids of Jubal Early. Meade wanted the role to free himself from under Grant; however, the position was given to Sheridan. When Meade asked Grant why it did not go to himself, the more experienced officer, Grant stated that Lincoln did not want to take Meade away from the Army of the Potomac and imply that his leadership was substandard.[128]

During the Siege of Petersburg, he approved the plan of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside to plant explosives in a mine shaft dug underneath the Confederate line east of Petersburg, but at the last minute he changed Burnside's plan to lead the attack with a well-trained African-American division that was highly drilled just for this action, instructing him to take a politically less risky course and substitute an untrained and poorly led white division. The resulting Battle of the Crater was one of the great fiascoes of the war.[129]

Although he fought during the Appomattox Campaign, Grant and Sheridan received most of the credit, and Meade was not present when Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.[115]

With the war over, the Army of the Potomac was disbanded on June 28, 1865, and Meade's command of it ended.[130]

Political rivalries

[edit]Many of the political rivalries in the Army of the Potomac stemmed from opposition to the politically conservative, full-time officers from West Point. Meade was a Douglas Democrat and saw the preservation of the Union as the war's true goal and only opposed slavery as it threatened to tear the Union apart. He was a supporter of McClellan, the previously removed commander of the Army of the Potomac, and was politically aligned with him.[131] Other McClellan loyalists who advocated a more moderate prosecution of the war, such as Charles P. Stone and Fitz John Porter, were arrested and court-martialed.[96] When Meade was awakened in the middle of the night and informed that he was given command of the Army of the Potomac, he later wrote to his wife that he assumed that Army politics had caught up with him and he was being arrested.[132]

Meade's short temper earned him notoriety, and while he was respected by most of his peers and trusted by the men in his army, he did not inspire them.[133][134] While Meade could be sociable, intellectual and courteous in normal times, the stress of war made him prickly and abrasive and earned him the nickname "Old Snapping Turtle".[135] He was prone to bouts of anger and rashness and was paranoid about political enemies coming after him.[136]

His political enemies included Daniel Butterfield, Abner Doubleday, Joseph Hooker, Alfred Pleasonton and Daniel Sickles.[137] Sickles had developed a personal vendetta against Meade because of Sickles's allegiance to Hooker, whom Meade had replaced, and because of controversial disagreements at Gettysburg. Sickles had either mistakenly or deliberately disregarded Meade's orders about placing his III Corps in the defensive line,[138] which led to that corps' destruction and placed the entire army at risk on the second day of battle.[139]

Halleck, Meade's direct supervisor prior to Grant, was openly critical of Meade. Both Halleck and Lincoln pressured Meade to destroy Lee's army, but gave no specifics as to how it should be done.[119] Radical Republicans, some of whom like Thaddeus Stevens were former Know Nothings and hostile to Irish Catholics like Meade's family, in the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War suspected that Meade was a Copperhead and tried in vain to relieve him from command.[115] Sickles testified to the committee that Meade wanted to retreat his position at Gettysburg before the fighting started.[140] The joint committee did not remove Meade from command of the Army of the Potomac.[76]

Reconstruction

[edit]In July 1865, Meade assumed command of the Military Division of the Atlantic headquartered in Philadelphia. On January 6, 1868, he took command of the Third Military District in Atlanta. In January 1868, he assumed command of the Department of the South. The formation of the state governments of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina for reentry into the United States was completed under his direct supervision. When the Governor of Georgia refused to accept the Reconstruction Acts of Congress, Meade replaced him with General Thomas H. Ruger.[141]

After the Camilla massacre in September 1868, caused by anger from white southerners over blacks gaining the right to vote in the 1868 Georgia state constitution, Meade investigated the event and decided to leave the punishment in the hands of civil authorities. Meade returned to command of the Military Division of the Atlantic in Philadelphia.[142]

In 1869, following Grant's inauguration as president and William Tecumseh Sherman's assignment to general-in-chief, Sheridan was promoted over Meade to lieutenant general.[143] Meade effectively served in semi-retirement as the commander of the Military Division of the Atlantic from his home in Philadelphia.[144]

Personal life

[edit]On December 31, 1840 (his birthday), he married Margaretta Sergeant,[145] daughter of John Sergeant, running mate of Henry Clay in the 1832 presidential election.[10] They had seven children together: John Sergeant Meade, George Meade, Margaret Butler Meade, Spencer Meade, Sarah Wise Meade, Henrietta Meade, and William Meade.[146]

His notable descendants include:

- George Meade Easby, great-grandson[147]

- Happy Rockefeller, great-great-granddaughter[148]

- Matthew Fox, great-great-great-grandson[149]

Later life and death

[edit]

Meade was presented with a gold medal from the Union League of Philadelphia in recognition for his success at Gettysburg.[150]

Meade was a commissioner of Fairmount Park in Philadelphia from 1866 until his death. The city of Philadelphia gave Meade's wife a house at 1836 Delancey Place in which he also lived. The building still has the name "Meade" over the door, but is now used as apartments.[151]

Meade received an honorary doctorate in law (LL.D.) from Harvard University,[152] and his scientific achievements were recognized by various institutions, including the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences.[34][115][153]

Having long suffered from complications caused by his war wounds, Meade died on November 6, 1872, in the house at 1836 Delancey Place, from pneumonia.[151] He was buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery.[154][155]

Legacy

[edit]

Meade has been memorialized with several statues including an equestrian statue at Gettysburg National Military Park by Henry Kirke Bush-Brown;[156] the George Gordon Meade Memorial statue by Charles Grafly,[157] in front of the E. Barrett Prettyman United States Courthouse in Washington, D.C.;[158] an equestrian statue by Alexander Milne Calder; and one by Daniel Chester French atop the Smith Memorial Arch, both in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia.[159] A bronze bust of Meade by Boris Blai was placed at Barnegat Lighthouse in 1957.[160]

The United States Army's Fort George G. Meade in Fort Meade, Maryland, is named for him, as are Meade County, Kansas; Fort Meade, Florida; Fort Meade National Cemetery; and Meade County, South Dakota.[161] The Grand Army of the Republic Meade Post #1 founded in Philadelphia in 1866 was named in his honor.[162]

The General Meade Society was created to "promote and preserve the memory of Union Major General George Meade".[163] Members gather in Laurel Hill Cemetery on December 31 to recognize his birthday.[151] The Old Baldy Civil War Round Table in Philadelphia is named in honor of Meade's horse during the war.[164] In World War II, the United States Liberty ship SS George G. Meade was named in his honor.

The one-thousand-dollar Treasury Notes, also called Coin notes, of the Series 1890 and 1891, feature portraits of Meade on the obverse. The 1890 Series note is called the Grand Watermelon Note by collectors because the large zeroes on the reverse resemble the pattern on a watermelon.[165]

The preserved head of Old Baldy, Meade's wartime horse, was donated to the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia by the Grand Army of the Republic Museum in 1979.[166]

Memorials to Meade

[edit]-

George Gordon Meade Memorial, by Charles Grafly, in front of the E. Barrett Prettyman Federal Courthouse in Washington, D.C.

-

In honor of his war service, the city of Philadelphia gifted a house at 1836 Delancey Place to Meade's wife[167]

-

Equestrian statue of Meade by Henry Kirke Bush-Brown, on the Gettysburg Battlefield

-

Equestrian statue of Meade, by Alexander Milne Calder, in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

-

Statue of Meade atop the Smith Memorial Arch in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

In popular culture

[edit]Meade has been portrayed in several films and television shows:

- Alfred Allen portrayed Meade in the 1924 film The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln

- Thurston Hall portrayed Meade in the 1940 film Virginia City

- Rory Calhoun portrayed Meade in the 1982 TV miniseries The Blue and the Gray

- Richard Anderson portrayed Meade in the 1993 film Gettysburg, an adaptation of Michael Shaara's novel The Killer Angels

- Tom Hanks portrayed Meade in the 2021 TV series 1883[168]

Meade is a character in the 2003 alternate history novel Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War, written by Newt Gingrich and William Forstchen.

Dates of rank

[edit]| Insignia | Rank | Date | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| No insignia | Cadet, USMA | September 1, 1831 | Regular Army |

| Second Lieutenant | July 1, 1835 (brevet) December 31, 1835 (permanent) |

Regular Army | |

| First Lieutenant | September 23, 1846 (brevet) August 4, 1851 (permanent) |

Regular Army | |

| Captain | May 19, 1856 | Regular Army | |

| Brigadier General | August 31, 1861 | Volunteers | |

| Major | June 18, 1862 | Regular Army | |

| Major General | November 29, 1862 | Volunteers | |

| Brigadier General | July 3, 1863 | Regular Army | |

| Major General | August 18, 1864 | Regular Army |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Warner 1964, p. 315.

- ^ a b Huntington 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Baltzell, Edward Digby (1958). Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-88738-789-0. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Huntington 2013, p. 12.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 9.

- ^ Sauers 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 13.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 12.

- ^ a b Huntington 2013, p. 13.

- ^ a b Hyde 2003, p. 15.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 12.

- ^ a b Sauers 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 15.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 18.

- ^ Huntington 2013, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Sauers 2003, p. 6.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 19.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 27–28.

- ^ a b c d Warner 1964, p. 316.

- ^ Sauers 2003, p. 9.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 45.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 46.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 47.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 48.

- ^ Dean, Love, Reef Lights: Seaswept Lighthouses of the Florida Keys, The Historic Key West Preservation Board, 1982, ISBN 0-943528-03-8. McCarthy, Kevin M., Florida Lighthouses. University of Florida Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8130-0993-6.

- ^ a b Sauers 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 49.

- ^ a b Eicher & Eicher 2001, p. 385.

- ^ Woodford 1991, p. 37.

- ^ Woodford 1991, p. 40.

- ^ Woodford 1991, p. 41.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 22.

- ^ Hyde 2003, p. 16.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 55.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 61.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 49.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 68.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 69.

- ^ Brown 2021, p. 7.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 70.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 83.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, pp. 71–74.

- ^ Tagg 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Brown 2021, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 91.

- ^ a b c Brown 2021, p. 8.

- ^ Huntington 2013, p. 106.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 108.

- ^ Brown 2021, p. 6.

- ^ Brown 2021, p. 14.

- ^ Gallagher 1999, p. 136.

- ^ Brown 2021, p. 4.

- ^ Brown 2021, p. 25.

- ^ Schroeder, Patrick. "Joseph Hooker (1814-1879)". www.encyclopediavirginia.com. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 130.

- ^ Hyde 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Tagg 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Coddington 1997, p. 210.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 1.

- ^ Chick 2015, p. 10.

- ^ a b Hall 2003, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Tagg 1998.

- ^ Hall 2003, p. 167.

- ^ Gallagher 1999, p. 144.

- ^ Tagg 1998, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Brown 2021, p. 5.

- ^ a b "General George Meade's Forgotten Council of War". www.nps.gov. National Park Service United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 21, 2023.

- ^ "The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ^ Hall 2003, p. 264.

- ^ a b Chick 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Hyde 2003, p. 25.

- ^ Hall 2003, p. 259.

- ^ Warner 1964, pp. 316–317.

- ^ The Centennial of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1904. p. 503. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Meade, George (1913). The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade Major-General United States Army. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 154. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Backus & Orrison 2015, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Backus & Orrison 2015, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Backus & Orrison 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Backus & Orrison 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Backus & Orrison 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Backus & Orrison 2015, p. 16.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 234.

- ^ Backus & Orrison 2015, p. xx.

- ^ Chick 2015, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "Mine Run Payne's Farm". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ a b Chick 2015, p. 16.

- ^ Salmon 2001, p. 226.

- ^ Dunkerly, Pfanz & Ruth 2014, pp. xxi–xxii.

- ^ Chick 2015, p. 17.

- ^ Rafuse, Ethan S. "George Gordon Meade (1815-1872)". www.encyclopediavirginia.com. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Rhea 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Chick 2015, p. 20.

- ^ Dunkerly, Pfanz & Ruth 2014, p. 2.

- ^ Hogan 2014, p. 17.

- ^ Hogan 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Hogan 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Hogan 2014, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Hogan 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Rhea 2000, p. 36.

- ^ Rhea 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Coffey, David (2005). Sheridan's Lieutenants: Phil Sheridan, His Generals, and the Final Year of the Civil War. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 22. ISBN 0-7425-4306-4. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ Rhea 2000, p. 35.

- ^ Hogan 2014, p. 47.

- ^ Dunkerly, Pfanz & Ruth 2014, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d Heidler & Heidler 2002, p. 1296.

- ^ Rhea 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Hess, Earl J. (2007). Trench Warfare Under Grant & Lee - Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8078-3154-0. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Rhea 2000, p. 14.

- ^ a b Chick 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Hogan 2014, pp. 63–65.

- ^ Trudeau 1991, p. 33.

- ^ Huntington 2013, p. 277.

- ^ Grant, chapter LII (vol. II, p. 235). He further stated that "I would not like to see one of these promotions at this time without seeing both."

- ^ Eicher & Eicher 2001, p. 703.

- ^ Warner, p. 644. Sherman was appointed on August 12, 1864, and confirmed on December 12 with date of rank August 12. Sheridan was appointed on November 14, with date of rank November 8. Meade was not appointed until November 26, although his date of rank was established as August 18, meaning he technically outranked Sheridan, but was embarrassed that his name was not put forward first.

- ^ Eicher & Eicher 2001, pp. 701–702.

- ^ Trudeau 1991, p. 48.

- ^ Trudeau 1991, p. 141.

- ^ Wolfe, Brendan. "Crater, Battle of the". www.encyclopediavirginia.com. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ Huntington 2013, p. 350.

- ^ Chick 2015, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Coddington 1997, p. 209.

- ^ Tagg 1998, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Heidler & Heidler 2002, p. 1295.

- ^ "General George Meade Equestrian Statue". www.nps.gov. National Park Service United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- ^ Chick 2015, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Chick 2015, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hall 2003, p. 98.

- ^ Sears, Stephen W. (1999). Controversies & Commanders: Dispatches from the Army of the Potomac. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. pp. 215–222. ISBN 978-0-618-05706-1. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Coddington 1997, p. 339.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 389.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 390.

- ^ Warner 1964, p. 644.

- ^ Cole, Arthur C.; Meade, George; Meade, George Gordon (March 1915). "The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, Major-General United States Army". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 1 (4): 296–301. doi:10.2307/1886971. ISSN 0161-391X. JSTOR 1886971.

- ^ Cleaves 1960, p. 17.

- ^ The Pennsylvania magazine of history and biography. Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. 1900. p. 243. Retrieved February 28, 2023.

- ^ "Visitors didn't stand a 'ghost of a chance': George G. Meade Easby, a one-of-a-kind Hiller" Archived August 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Chestnut Hill Local, December 15, 2005.

- ^ Weaber, Gerald (November 2009). "Fascinating Fitlers among the movers and shakers since Riverton's early days" (PDF). Gaslight News. XXXIX (4). Historical Society of Riverton: 5. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ Sharp, Nathan (July 14, 2020). "10 Things You Didn't Know About the Cast of Lost". www.thethings.com. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Hyde 2003, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Kyriakodis, Harry (August 7, 2015). "Forgotten And Alone: Bring Old Baldy And the General Into Town". www.hiddencityphila.org. Hidden City Philadelphia. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ Pennypacker 1901, p. 391.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Eicher & Eicher 2001, p. 384.

- ^ "The Soldier's Rest.; Obsequies of Gen. Meade in Philadelphia" (PDF). The New York Times. November 11, 1872.

- ^ "Henry Kirke Brown: The Father of American Sculpture". www.library.udel.edu. University of Delaware. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Scott, Gary (September 19, 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form – Civil War Monuments in Washington, D.C." National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ "Major General George Gordon Meade Monument". www.historicsites.dcpreservation.org. DC Preservation League. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Smith Memorial Arch (1897 – 1912)". www.associationforpublicart.org. Association for Public Art. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Huntington 2013, p. 32.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1940). South Dakota place-names, v.1-3. University of South Dakota. p. 38. Archived from the original on June 6, 2016.

- ^ Waskie, Andy (July 7, 2021). "Story of the G.A.R. Post #2 'Army Mule'". www.generalmeadesociety.org. The General Meade Society of Philadelphia, Inc. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "General Meade Society - Mission Statement". www.generalmeadesociety.org. The General Meade Society of Philadelphia, Inc. March 11, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Old Baldy Civil War Round Table of Philadelphia". www.oldbaldycwrt.org. South Bay CWRT. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Grand Watermelon Note". www.atlantafed.org. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Rosenheck, Mabel. "Civil War Museum of Philadelphia". www.philadelphiaencyclopedia.org. The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Nickels, Thom (2014). Legendary Local of Center City Philadelphia Pennsylvania. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4671-0141-7. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ Melas, Chloe (December 27, 2021). "Tom Hanks makes cameo in '1883'". CNN. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ Cullum, George W. (1891). Biographical register of the officers and graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., from its establishment in 1802 to 1890. Vol. I (3rd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 601–609.

- ^ Official Army Register for January 1871. Washington: Adjutant General's Office. 1871. p. 3.

Sources

- Backus, Bill; Orrison, Robert (2015). A Want of Vigilance: The Bristoe Station Campaign October 9-19, 1863. Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-300-3.

- Brown, Kent Masterson (2021). Meade at Gettysburg: A Study in Command. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-6200-8.

- Chick, Sean Michael (2015). The Battle of Petersburg, June 15-18, 1864. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-61234-737-0.

- Cleaves, Freeman (1960). Meade of Gettysburg. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2298-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Coddington, Edwin B. (1997). The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-84569-2.

- Davis, William C. (1986). Death in the Trenches: Grant at Petersburg - Volume 22 of Civil War. Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-809-44777-0.

- Dunkerly, Robert M.; Pfanz, Donald C.; Ruth, David R. (2014). No Turning Back: A Guide to the 1864 Overland Campaign, From the Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May 4 - June 13, 1864. Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-193-1.

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J. (2001). Civil War High Commands. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Gallagher, Gary W. (1999). Three Days at Gettysburg: Essays on Confederate and Union Leadership. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-629-9.

- Grant, Ulysses S. (1885). Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. Charles L. Webster & Company.

- Hall, Jeffrey C. (2003). The Stand of the U.S. Army at Gettysburg. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34258-9.

- Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T. (2002). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-3930-4758-5.

- Hogan, David W. Jr. (2014). The Overland Campaign, 4 May - 15 June 1864. Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 978-0-16-092517-7.

- Huntington, Tom (2013). Searching for George Gordon Meade: The Forgotten Victor of Gettysburg. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0813-5.

- Hyde, Bill (2003). The Union Generals Speak: The Meade Hearings on the Battle of Gettysburg. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2581-4.

- Jaynes, Gregory (1986). The Killing Ground: Wilderness to Cold Harbor - Volume 1 of Civil War. Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-809-44768-8.

- Pennypacker, Isaac Rusling (1901). General Meade. D. Appleton and Company. ISBN 978-0-7222-9257-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Rhea, Gordon C. (2000). To the North Anna River: Grant and Lee, May 13–25, 1864. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-3111-4.

- Salmon, John S. (2001). The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Sauers, Richard A. (2003). Meade: Victor of Gettysburg. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 1-57488-418-2.

- Schmutz, John F. (2009). The Battle of the Crater: A Complete History. McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-3982-9.

- Tagg, Larry (1998). The Generals of Gettysburg - The Leaders of America's Greatest Battle. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81242-2.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre (1991). The Last Citadel - Petersburg June 1864 - April 1865. Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-212-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. (1964). Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Woodford, Arthur M. (1991). Charting the Inland Seas: A History of the U.S. Lake Survey. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2499-1.

Further reading

- Brown, Canter Jr. (1991). "Moving a military road" (PDF). South Florida History Magazine. No. 2. pp. 8–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2017 – via HistoryMiami.

- Hunt, Harrison. Heroes of the Civil War. New York: Military Press, 1990. ISBN 0-517-01739-3.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Stowe, Christopher S. "A Philadelphia Gentleman: the Cultural, Institutional, and Political Socialization of George Gordon Meade". PhD diss., University of Toledo, 2005.

External links

[edit]- The George G. Meade collection, including papers covering all aspects of his career, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- General Meade Society of Philadelphia

- Photographs of Meade at the Wayback Machine (archived February 8, 2008)

George Meade

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Family Background and Childhood

George Gordon Meade was born on December 31, 1815, in Cádiz, Spain, to American parents Richard Worsam Meade, a successful Philadelphia merchant serving as a U.S. naval agent, and Margaret Coats Butler.[3] [4] He was one of eleven children in the family, which had relocated to Spain for business opportunities amid the Napoleonic Wars.[4] [5] The Meades returned to Philadelphia in Meade's infancy around 1817, following financial losses incurred by Richard Meade's investments and support for the Spanish monarchy against French occupation, which led to debts and legal troubles.[2] The family settled in the city, where young George spent much of his early childhood, though they later resided briefly in Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, D.C.[3] Richard Meade's death on June 25, 1828, exacerbated the family's economic distress, leaving an estate burdened by obligations and forcing reliance on relatives.[6] In Philadelphia, Meade attended local private schools, including the Mt. Airy School, until financial constraints necessitated withdrawal after his father's passing; he later studied at the Mount Hope Institution in Baltimore.[5] [4] These experiences honed his aptitude for mathematics, evident from an early age, amid a household marked by modest means and frequent relocations managed by his mother.[3]West Point and Early Training

Meade received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point on September 1, 1831, at the age of fifteen, facilitated by President Andrew Jackson amid his family's financial difficulties following the father's business failures.[7] [8] The academy's rigorous curriculum, emphasizing mathematics, engineering, fortifications, and infantry tactics, prepared cadets for artillery and engineering branches, though Meade initially viewed military service as a means to a free education rather than a lifelong commitment.[9] He graduated on July 1, 1835, ranking 19th in a class of 56 cadets, earning a brevet commission as second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery.[7] [8] Upon graduation, Meade was promoted to full second lieutenant on December 31, 1835, and assigned to artillery duties, beginning with brief service in New York before deployment to Florida for the Second Seminole War.[7] In Florida from late 1835 to mid-1836, he participated in operations against Seminole forces in swampy terrain, gaining early field experience in irregular warfare, supply logistics, and light artillery maneuvers under challenging tropical conditions.[8] [9] These engagements provided practical training in combat deployment but exposed him to harsh environmental factors, including endemic diseases. Meade's health deteriorated from a severe fever contracted during Florida service, leading to his resignation from the army on October 26, 1836, after brief ordnance duties earlier that year.[7] [10] This early period honed his technical skills in artillery and engineering while revealing the physical demands of frontier military operations, influencing his later preference for staff and topographical roles over frontline command.[9]Antebellum Military Career

Service in the Topographical Engineers

Meade was reinstated in the United States Army as a second lieutenant in the Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1842, following a brief resignation and civilian engineering work.[2] He performed duties centered on hydrographic surveys, coastal fortifications, and infrastructure projects essential for navigation and defense.[9] From 1850, Meade contributed to lighthouse construction in Delaware Bay under Major Hartman Bache, designing and overseeing the innovative screwpile structure for Brandywine Shoal Lighthouse, which featured eight iron pile legs driven into the seabed for stability in shifting sands.[11] He advanced to supervising Florida Reef surveys and lighthouse builds, completing the Carysfort Reef Lighthouse on March 10, 1852, after adapting designs with stabilizing disks for the coral base and securing congressional funding despite delays.[11] Subsequent projects included resuming Sand Key Lighthouse construction post-1852, installing a five-wick hydraulic lamp there that influenced broader adoption; overseeing the 147-foot iron diskpile Sombrero Key Lighthouse before 1856; establishing a beacon at Rebecca Shoal in 1855; and directing masonry towers at Barnegat and Cape May, New Jersey.[11] Meade also selected the site and designed the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse in 1854 and extended the Cape Florida Lighthouse in 1855.[11] Promoted to captain on May 19, 1856, for continuous service, Meade shifted focus in 1857 to commanding the Northern Lakes Survey of the Great Lakes, based in Detroit, where he directed hydrographic charting to support commerce and navigation.[9][12] Under his leadership, the survey produced the first detailed report on the Great Lakes in 1860, including triangulation and depth mappings of Lakes Huron, Michigan, and extensions into others, completing foundational work interrupted by the Civil War in 1861.[13] His geospatial expertise in these roles emphasized precise instrumentation and fieldwork, yielding maps that aided military and civilian applications.[14]Mexican-American War Participation

Meade, serving as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, deployed to Texas in early 1846 amid escalating tensions with Mexico, where he conducted surveys of potential border areas and military routes in preparation for conflict.[9] Following the outbreak of war on May 13, 1846, he joined General Zachary Taylor's army on the Rio Grande, participating in the advance that led to the battles of Palo Alto on May 8 and Resaca de la Palma on May 9, though his primary duties involved topographic reconnaissance rather than direct infantry engagement.[2] [8] In September 1846, Meade accompanied Taylor's forces to Monterrey, where he served on the staff and contributed to engineering assessments during the siege and assault from September 19 to 24. For his gallant conduct under fire while aiding in the positioning of artillery and mapping assault routes amid intense urban fighting, Meade received a brevet promotion to first lieutenant on September 23, 1846, one of several officers recognized for bravery in the costly but successful capture of the city.[15] [9] After Monterrey, illness—likely from exposure and exertion—forcing his return to the United States in late 1846, though he briefly rejoined operations under General Winfield Scott in 1847 for limited surveying before resuming peacetime duties.[2] His Mexican War service, emphasizing geospatial intelligence and staff support over frontline combat, honed skills in rapid terrain analysis that later proved vital in larger-scale operations.[14]American Civil War Campaigns

Peninsula Campaign and Seven Days Battles

In March 1862, Brigadier General George G. Meade's brigade of the Pennsylvania Reserves Division was assigned to Major General George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac for the Peninsula Campaign, an effort to advance on the Confederate capital of Richmond via the Virginia Peninsula.[16] Meade commanded the 2nd Brigade, consisting of the 3rd, 4th, 7th, and 11th Pennsylvania Reserve Infantry Regiments, under the division of Major General George A. McCall, which operated initially as an independent force before attachment to the V Corps during the campaign's critical phase.[17][18] The Pennsylvania Reserves, including Meade's brigade, saw limited action in the early stages of the campaign but became heavily engaged during the Confederate counteroffensive known as the Seven Days Battles from June 25 to July 1, 1862. At the Battle of Mechanicsville on June 26, Meade's brigade helped secure the Union right flank along Beaver Dam Creek, contributing to the repulse of Confederate attacks under Major General Thomas J. Jackson, though it remained largely in reserve.[2] On June 27 at Gaines' Mill, the brigade was committed piecemeal to reinforce the V Corps line east of the Chickahominy River against assaults by elements of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, suffering significant casualties in the heaviest fighting of the day, which forced a Union withdrawal.[8][2] The brigade's most intense combat occurred at the Battle of Glendale (also called Frayser's Farm) on June 30, where McCall's division, including Meade's 2nd Brigade, formed part of the Union rearguard attempting to link the separated wings of McClellan's army during the retreat toward the James River. Positioned on the right flank of the line south of Richmond in Henrico County, Meade's brigade defended against repeated Confederate assaults led by Major General Benjamin Huger and others, with fighting spilling over to support Captain Alanson Randol's artillery battery; the brigade endured heavy losses while holding the position amid close-quarters combat.[2][19] During the battle, Meade sustained multiple severe wounds—a gunshot to the right arm, another passing through his back and hip, and a lung injury—yet refused to leave the field until directly ordered by McClellan, after which subordinates assumed command.[3][20] Evacuated for treatment, Meade recovered at his Philadelphia home by late July, having demonstrated personal bravery that bolstered his reputation among subordinates despite the campaign's overall Union setbacks.[9]Northern Virginia and Maryland Campaigns

Following the Peninsula Campaign, Meade's brigade of the Pennsylvania Reserves Division, part of the V Corps under Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, was detached to reinforce Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia during the Northern Virginia Campaign in late August 1862.[21] On August 29–30, 1862, at the Second Battle of Bull Run (also known as Second Manassas), Meade commanded the 1st Brigade of the Pennsylvania Reserves under Brig. Gen. John F. Reynolds, engaging Confederate forces on the Union left flank amid Pope's disorganized retreat; the brigade helped cover the withdrawal but could not prevent the overall Union defeat, which allowed Gen. Robert E. Lee to invade Maryland.[21][3] As Lee's Army of Northern Virginia advanced into Maryland, Meade received promotion to command the 3rd Division (Pennsylvania Reserves) of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's I Corps in the Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan around September 12, 1862.[3] On September 14, 1862, during the Battle of South Mountain, Meade's division spearheaded the assault on Turner's Gap in the South Mountain range, launching relentless uphill charges against entrenched Confederate positions held by Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill's corps; after heavy fighting, the division captured the gap by late afternoon, contributing to the Union breakthrough that forced Lee to abandon his divided forces and consolidate at Sharpsburg.[22][3] Three days later, on September 17, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Meade's division opened the Union attack on Lee's center, advancing through the East Woods and Cornfield against heavy artillery and infantry fire from Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson's corps before wheeling south to assault the Confederate left at the Sunken Road (later called Bloody Lane).[23][24] By approximately 10:00 a.m., Union troops under Meade's command overran and briefly captured the road, inflicting severe casualties on the defenders, but lack of timely reinforcement from other I Corps units allowed Confederate counterattacks under Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood and others to reclaim the position, stalling the breakthrough.[24][3] Early in the battle, with I Corps commander Reynolds killed, Meade assumed temporary command of the corps, coordinating its efforts amid the bloodiest single-day engagement of the war, which ended as a tactical draw but prompted Lee's withdrawal, enabling President Abraham Lincoln to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.[1][3] Meade's division suffered approximately 50 percent casualties, reflecting its central role in the fighting on the Union right and center.[24]Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville Engagements

During the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, George G. Meade commanded the 3rd Division of the I Corps within the Army of the Potomac's Left Grand Division, led by Major General Edwin V. Sumner.[7] His division, consisting of approximately 4,500 men from Pennsylvania regiments, spearheaded the main Union assault against Prospect Hill on the Confederate right flank, defended by Lieutenant General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's corps.[7] [25] Around 1:00 p.m., under intense Confederate artillery fire from multiple directions, Meade's troops advanced across exposed fields, briefly penetrating and disrupting the enemy line near Hamilton's Crossing before enfilading fire and counterattacks forced a retreat due to the absence of reinforcing divisions from adjacent commands.[7] [25] The division incurred heavy losses, with over 2,000 casualties out of its strength, representing one of the few instances of Union troops reaching Confederate positions in the engagement.[9] Meade's bold leadership in this unsupported advance drew commendation from superiors, contributing to his promotion to major general of volunteers effective retroactively from that date.[7] Following Fredericksburg, Meade assumed command of the V Corps in the Army of the Potomac on February 25, 1863, a position he held during the Chancellorsville campaign from late April to early May.[26] [9] Under Major General Joseph Hooker, the Union army crossed the Rappahannock River on April 29–30, with V Corps forming part of the main force positioning south of Fredericksburg to threaten the Confederate right, while Meade's units conducted demonstrations to fix enemy attention.[26] As Confederate General Robert E. Lee divided his forces to counter Hooker's maneuvers, Meade's corps remained on the Union left flank near the Rappahannock, engaging in limited skirmishing but avoiding major combat amid Hooker's cautious posture after initial successes.[10] [26] On May 3, following Hooker's incapacitation by a concussion from artillery debris, Meade—third in seniority—temporarily assumed direction of the army's right wing but deferred broader command decisions, prioritizing withdrawal across the river amid the unfolding Confederate flanking victory by Jackson's corps.[26] V Corps suffered relatively light casualties compared to other units, with Meade later criticizing Hooker's failure to exploit early advantages and press the attack aggressively against Lee's inferior numbers.[9] These engagements highlighted Meade's tactical competence in corps-level operations despite overarching Union strategic setbacks, positioning him for higher responsibility in subsequent campaigns.[7]Gettysburg Campaign

On June 28, 1863, Major General George G. Meade, previously commanding the V Corps, was unexpectedly appointed to lead the Army of the Potomac after President Abraham Lincoln relieved Joseph Hooker due to disagreements over strategy during the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania.[27] [28] Meade received the order late that night from Major General Henry W. Halleck's representative and immediately issued General Order No. 66, assuming command of approximately 90,000 troops while directing a northward concentration to intercept General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, which numbered around 75,000 men advancing toward Harrisburg and the Susquehanna River.[27] [29] Meade's initial directives emphasized rapid marches and pipe-laying for water supply, reflecting his engineering background, though the army's scattered positions across Maryland delayed full assembly.[28] As Confederate forces under Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell and A.P. Hill engaged Union cavalry under Brigadier General John Buford on July 1 near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Meade, still at Taneytown, Maryland, about 35 miles south, reinforced the position with I Corps under Major General John F. Reynolds and XI Corps under Major General Oliver O. Howard, establishing a defensive line along Cemetery Ridge and Culp's Hill.[10] [29] Meade arrived at the battlefield on July 2, coordinating the timely arrival of reinforcements like the VI Corps under Major General John Sedgwick, while directing artillery chief Brigadier General Henry J. Hunt to mass guns on Cemetery Hill; his decisions prevented a Confederate breakthrough during attacks on the Peach Orchard and Little Round Top by Lieutenant General James Longstreet's corps.[30] [31] That evening, Meade convened a council of war at his headquarters in the Leister farmhouse, where seven of eight corps commanders advised holding the defensive line rather than attacking, a consensus he endorsed based on reports of Union casualties exceeding 20,000 and ammunition shortages.[30] On July 3, Confederate assaults, including Pickett's Charge against the Union center, were repulsed with heavy losses, totaling around 28,000 for Lee versus approximately 23,000 for Meade's army, marking a tactical Union victory secured by Meade's emphasis on interior lines and coordinated defense.[32] [33] Following the battle, Meade ordered a pursuit southwestward on July 4 amid torrential rains that turned roads to mud and swelled rivers, advancing his depleted force—now short on supplies, with over 10,000 prisoners to manage and multiple corps commanders wounded or killed—toward the Potomac River to block Lee's retreat.[34] [35] Skirmishes occurred at Monterey Pass and Wapping Heights on July 4–6, where Union forces captured artillery and wagons, but the flooded Potomac delayed Lee's crossing until pontoon bridges were completed near Falling Waters, Maryland.[34] By July 12, Meade concentrated near Williamsport, facing Lee's entrenched army of about 50,000, but a second council of war on July 13–14 voted 13–2 against assaulting the fortifications, citing risks to the exhausted Union troops lacking siege equipment and fresh reinforcements; Lee escaped across the Potomac on July 13–14 without further major engagement.[34] [35] Lincoln expressed frustration in correspondence with Halleck over the perceived lack of aggression, urging Meade to "follow and fight" Lee, though historical analyses note Meade's advance covered 80 miles in adverse conditions and inflicted additional casualties, preserving the Army of the Potomac for future operations despite not achieving Lee's destruction.[36] [34]Assumption of Army Command

Following the Union defeat at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, Major General Joseph Hooker, commander of the Army of the Potomac, faced mounting criticism for his performance and strategic decisions, including his failure to pursue the retreating Confederate forces effectively.[2] On June 27, 1863, Hooker requested either reinforcements or permission to withdraw his army south of the Potomac River amid concerns over Confederate movements under General Robert E. Lee, prompting President Abraham Lincoln to accept his resignation the following day.[2] [3] Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sought a replacement urgently as Lee's army invaded Pennsylvania, initially offering the command to corps commanders such as John F. Reynolds and others, who declined or were unavailable.[26] On the morning of June 28, 1863, near Frederick, Maryland, where Meade commanded the V Corps, he was abruptly informed by Major General Darius N. Couch and Adjutant General Seth Williams of his appointment to lead the 100,000-man Army of the Potomac, a role he accepted with reluctance due to his lack of prior army-level command experience.[37] [38] The decision met with broad approval from the army's senior officers, who respected Meade's competence demonstrated in earlier campaigns.[3] Meade wasted no time in assuming command, issuing General Orders No. 67 that afternoon, which formally announced his leadership and emphasized discipline, rapid movement northward to intercept Lee, and living off the country to avoid supply line vulnerabilities.[39] He reorganized the army's structure slightly, retaining the corps system but directing convergence on Emmitsburg, Maryland, to position for battle, all while navigating incomplete intelligence on Lee's dispersed forces.[1] This sudden transition occurred just three days before the Battle of Gettysburg, thrusting Meade into a pivotal role without prior consultation with Lincoln, who later expressed confidence in the choice based on Meade's reputation for engineering precision and tactical steadiness.[2][38]Battle of Gettysburg