Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Needlepoint

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

Needlepoint is a type of canvas work, a form of embroidery in which yarn is stitched through a stiff open weave canvas. Traditionally needlepoint designs completely cover the canvas.[1] Although needlepoint may be worked in a variety of stitches, many needlepoint designs use only a simple tent stitch and rely upon color changes in the yarn to construct the pattern. Needlepoint is the oldest form of canvas work.[2]

The degree of detail in needlepoint depends on the thread count of the underlying mesh fabric. Due to the inherent lack of suppleness of needlepoint, common uses include eyeglass cases, holiday ornaments, pillows, purses, upholstery, and wall hangings.[3]

History

[edit]The roots of needlepoint go back thousands of years to the ancient Egyptians, who used small slanted stitches to sew up their canvas tents. Howard Carter, of Tutankhamen fame, found some needlepoint in the cave of a Pharaoh who had lived around 1500 BC.[2]

Modern needlepoint descends from the canvas work in tent stitch, done on an evenly woven open ground fabric that was a popular domestic craft in the 16th century.[4]

Further development of needlepoint was influenced in the 17th century by Bargello[5] and in the 19th century by shaded Berlin wool work in brightly colored wool yarn. Upholstered furniture became fashionable in the 17th century, and this prompted the development of a more durable material to serve as a foundation for the embroidered works of art. In 18th century America, needlepoint was used as a preparatory skill to train young women to sew their own clothing.[6]

Terminology

[edit]- Differences between needlepoint and other types of embroidery

-

Needlepoint is worked upon specialized types of stiff canvas that have openings at regular intervals.

-

Embroidery that is not needlepoint often uses soft cloth and requires an embroidery hoop.

When referring to handcrafted textile arts which a speaker is unable to identify, the appropriate generalized term is "needlework". The first recorded use of the term needlepoint is in 1869, as a synonym for point-lace.[7] Mrs Beeton's Beeton's Book of Needlework (1870) does not use the term "needlework", but rather describes "every kind of stitch which is made upon canvas with wool, silk or beads" as Berlin Work (also spelled Berlinwork). Berlin Work refers to a subset of needlepoint, popular in the mid-19th century that was stitched in brightly colored wool on needlepoint canvas from hand-colored charts.[8]

"Needlepoint" refers to a particular set of stitching techniques worked upon stiff openwork canvas.[9][10][11] However, "needlepoint" is not synonymous with all types of embroidery. Because it is stitched on a fabric that is an open grid, needlepoint is not embellishing a fabric, as is the case with most other types of embroidery, but literally the making of a new fabric. It is for this reason that many needlepoint stitches must be of sturdier construction than other embroidery stitches.

Needlepoint is often referred to as "tapestry"[12] in the United Kingdom and sometimes as "canvas work". However, needlepoint—which is stitched on canvas mesh—differs from true tapestry—which is woven on a vertical loom. When worked on fine weave canvas in tent stitch, it is also known as "petit point". Additionally, "needlepoint lace" is also an older term for needle lace, an historic lace-making technique.

Contemporary techniques

[edit]Materials

[edit]The thread used for stitching may be wool, silk, cotton or combinations, such as wool-silk blend. Variety fibers may also be used, such as metallic cord, metallic braid, ribbon, or raffia. Stitches may be plain, covering just one thread intersection with a single orientation, or fancy, such as in bargello or other counted-thread stitches. Plain stitches, known as tent stitches, may be worked as basketweave, continental or half cross. Basketweave uses the most wool, but does not distort the rectangular mesh and makes for the best-wearing piece.

Several types of embroidery canvas are available: single thread and double thread embroidery canvas are open even-weave meshes, with large spaces or holes to allow heavy threads to pass through without fraying. Canvas is sized by mesh sizes, or thread count per inch. Sizes vary from 5 threads per inch to 24 threads per inch; popular mesh sizes are 10, 12, 14, 18, and 24. The different types of needlepoint canvas available on the market are interlock, mono, penelope, plastic, and rug.[13]

- Interlock Mono Canvas is more stable than the others and is made by twisting two thin threads around each other for the lengthwise thread and "locking" them into a single crosswise thread. Interlock canvas is generally used for printed canvases. Silk gauze is a form of interlock canvas, which is sold in small frames for petit-point work. Silk gauze most often comes in 32, 40 or 48 count, although some 18 count is available and 64, 128 and other counts are used for miniature work.

- Mono canvas comes in the widest variety of colors (especially 18 mesh) and is plain woven, with one weft thread going over and under one warp thread. This canvas has the most possibilities for manipulation and open canvas. It is used for hand-painted canvases as well as counted thread canvaswork.

- Penelope canvas has two threads closely grouped together in both warp and weft. Because these threads can be split apart, penelope sizes are often expressed with two numbers, such as 10/20.

- Plastic canvas is a stiff canvas that is generally used for smaller projects and is sold as "pre-cut pieces" rather than by the yard. Plastic canvas is an excellent choice for beginners who want to practice different stitches.[14]

- Rug canvas is a mesh of strong cotton threads, twisting two threads around each other lengthwise forms the mesh and locking them around a crosswise thread made the same way; this cannot be separated. Canvases come in different gauges, and rug canvas is 3.3 mesh and 5 mesh, which is better for more detailed work.

Frames and hoops

[edit]Needlepoint canvas is stretched on a scroll frame or tacked onto a rectangular wooden frame to keep the work taut during stitching. Petit point is sometimes worked in a small embroidery hoop rather than a scroll frame.

Patterns

[edit]Commercial designs for needlepoint may be found in different forms: hand-painted canvas, printed canvas, trammed canvas, charted canvas, and free-form.

In hand-painted canvas, the design is painted on the canvas by the designer, or painted to their specifications by an employee or contractor. Canvases may be stitch-painted, meaning each thread intersection is painstakingly painted so that the stitcher has no doubts about what color is meant to be used at that intersection. Alternatively, they may be hand-painted, meaning that the canvas is painted by hand but the stitcher will have to use their judgment about what colors to use if a thread intersection is not clearly painted. Hand-painted canvases allow for more creativity with different threads and unique stitches by not having to pay attention to a separate chart. In North America this is the most popular form of needlepoint canvas.

Printed canvas is when the design is printed by silk screening or computer onto the needlepoint canvas. Printing the canvas in this means allows for faster creation of the canvas and thus has a lower price than Hand-Painted Canvas. However, care must be taken that the canvas is straight before being printed to ensure that the edges of the design are straight. Designs are typically less involved due to the limited color palette of this printing method. The results (and the price) of printed canvas vary extensively. Often printed canvases come as part of kits, which also dramatically vary in quality, based on the printing process and the materials used. This form of canvas is widely available outside North America.

On a trammed canvas the design is professionally stitched onto the canvas by hand using horizontal stitches of varying lengths of wool of the appropriate colours. The canvas is usually sold together with the wool required to stitch the trammed area. The stitcher then uses tent stitch over the horizontal lines with the trame stitches acting as an accurate guide as to the colour and number of stitches required. This technique is particularly suited to designs with a large area of mono-colour background as such areas do not require tramming, reducing the cost of the canvas and allowing the stitcher to choose the background colour themselves. The Portuguese island of Madeira is the historic centre for the manufacture of trammed canvases.

Charted canvas designs are available in book or leaflet form. They are available at book stores and independent needlework stores. Charted Canvas designs are typically printed in two ways: either in grid form with each thread intersection being represented with a symbol that shows what color is meant to be stitched on that intersection, or as a line drawing where the stitcher is to trace the design onto his canvas and then fill in those areas with the colors listed. Books typically include a grouping of designs from a single designer such as Kaffe Fassett or Candace Bahouth, or may be centered on a theme such as Christmas or Victorian Needlepoint. Leaflets usually include one to two designs and are usually printed by the individual designer.

Free-form needlepoint designs are created by the stitcher. They may be based around a favorite photograph, stitch, thread color, etc. The stitcher just starts stitching! Many interesting pieces are created this way. It allows for the addition of found objects, appliqué, computer-printed photographs, goldwork, or specialty stitches.

While traditionally needlepoint has been done to create a solid fabric, more modern needlepoint incorporates colored canvas, a variety of fibers and beadwork. Different stitching techniques also allow some of the unstitched, or lightly stitched, canvas to show through, adding an entirely new dimension to needlepoint work. Some of these techniques include "shadow" or "light" stitching, blackwork on canvas, and pattern darning.

Needlepoint continues to evolve as stitchers use new techniques and threads, and add appliqué or found materials. The line between needlepoint and other forms of embroidery is becoming blurred as stitchers adapt techniques and materials from other forms of embroidery to needlepoint.

Famous needlepointers

[edit]Historical and political figures

[edit]Royal needlepointers include: Mary, Queen of Scots,[15] Marie Antoinette,[16] Queen Elizabeth I, Princess Grace[citation needed]. In fact, the American Needlepoint Guild has established a Princess Grace Award (Needlepoint) for needlepoint completed entirely in tent stitch.[17] (This award is not formally associated with the Princess Grace Foundation which presents the "Princess Grace Awards".[18])

An American historical figure who was an avid needlepointer is Martha Washington, the wife of George Washington.[19]

Modern celebrities

[edit]American football player Roosevelt "Rosey" Grier released a book titled Rosey Grier's Needlepoint for Men (1973) that shows Grier stitching and samples of his work.[20]

Actress Mary Martin's book Mary Martin's Needlepoint (1969) catalogues her works and provides needlework tips.[21] The American actress Sylvia Sidney sold needlepoint kits featuring her designs,[22] and she published two popular instruction books: Sylvia Sidney's Needlepoint Book[23] and The Sylvia Sidney Question and Answer Book on Needlepoint.[24]

The MTV documentary 9 Days and 9 Nights with Ed Sheeran (2014)[25] revealed that Taylor Swift made Sheeran a Drake-themed needlepoint as a friendship gesture.[26]

Actress Loretta Swit's book, A Needlepoint Scrapbook (1986), includes a design for Ms. Pac-Man.[27]

Needlepoint stitches

[edit]Most commercial needlework kits recommend one of the variants of tent stitch, although Victorian cross stitch and random long stitch are also used.[28] Authors of books of needlepoint designs sometimes use a wider range of stitches.[29][30] Historically, a very wide range of stitches have been used including:

- Arraiolos stitch for Arraiolos rugs

- Bargello (needlework)

- Old Florentine stitch

- Hungarian ground stitch

- Hungarian point stitch

- Brick stitch

- Cross-stitch – Form of counted-thread embroidery

- Upright cross stitch – This stitch creates an almost crunchy texture and can be used on both single and double canvas. [31]

- (Victorian) cross stitches – X or + shaped embroidery stitch

- Gobelin stitch – A slanting stitch worked over two horizontal threads and one perpendicular.

- Encroaching upright Gobelin stitch

- Long stitch - A pattern of triangles in double rows used on a single canvas.[31]

- Mosaic stitch

- Parisian stitch – Embroidery stitch used in needlepoint and canvas work

- Smyrna stitch – Form of cross stitch used in needlepoint

- Tent stitch – Small, diagonal needlepoint or canvas work embroidery stitches. Variants include:

- Basketweave, Continental and Half cross

- Whipped flower stitch

There are many books that teach readers how to create hundreds, if not thousands, of stitches. Some were written by famous stitchers, such as Mary Martin and Sylvia Sidney. However, the most popular and long-lived[citation needed] is The Needlepoint Book[32] by Jo Ippolito Christensen, Simon & Schuster. First published in 1976 by Prentice-Hall, the widely distributed text has been continuously in print and was revised in 2015. Over 425,000 copies have been sold as of 2023. It contains 436 stitches and 1680 illustrations in 560 pages.

In popular culture

[edit]A needlepoint stitched by Cullen Bohannon's murdered wife, Mary, is referred to repeatedly throughout Hell on Wheels season 1. For example, in episode 2, "Immoral Mathematics" (November 13, 2011), Bohannon flashes back to seeing Mary stitching the needlepoint; in episode 3, "A New Birth of Freedom" (November 20, 2011), Bohannon finds a piece of that finished needlework in the personal effects of the now-deceased foreman, Daniel Johnson (who in the previous episode had admitted to being part of the Union outfit that raped and killed Mary); and in episode 4, "Jamais je ne t'oublierai" (November 27, 2011), the inebriated Bohannon realizes he's lost the needlepoint, and he gets into a fight with Bolan, when the latter tauntingly reveals that he has the swatch.

Needlepoint backgrounds were used most famously on the long running game show, Family Feud from its premiere with Richard Dawson in 1976 to the end of the Ray Combs era in 1994.

Examples

[edit]- Examples

-

The Bradford carpet, completed in the early 17th century, is a famous example of large canvas work. It is currently housed at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

-

From Switzerland, a valance depicting the Binding of Isaac – early 17th century.

-

A fire screen in Rococo style.

-

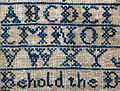

Detail of a sampler of Berlin wool work – middle 19th century.

-

A needlepoint pattern featured in an 1861 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book.

-

One of the hand-stitched patches for the Apollo–Soyuz mission, created by members of the American Needlepoint Guild.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nicholas, Kristin (2015). The Amazing Stitching Handbook for Kids. Concord, CA: C&T Publishing. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-60705-973-8.

- ^ a b "Canvaswork vs. Needlepoint – Save the Stitches by Nordic Needle". Archived from the original on May 13, 2017. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ "high cost of Needlepoint". Nuts about Needlepoint. 2018-01-27. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ "Needlepoint | canvas work embroidery". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ "Bargello work". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Peck, Amelia (October 2003). "American Needlework in the Eighteenth Century". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1973.

- ^ "Berlin woolwork | art". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Fasset, Kaffe (1989). Glorious Needlepoint\date= 1987. London: Century Hutchinson. ISBN 0-7126-3041-4.

- ^ Lazarus, Carole; Berman, Jennifer (1996). Glorafilia - The Ultimate Needlepoint Collection. London: Elbury Press. ISBN 0-09-180976-2.

- ^ Russell, Beth (1992). Traditional Needlepoint. Devon, David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-9984-5.

- ^ Gordon, Jill (1997). Jill Gordon's Tapestry Collection. London: Merehurst. ISBN 1-85391-636-6.

- ^ "A History of Tapestry | Past Impressions". www.past-impressions.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Nicholas, Kristin (2015). The Amazing Stitch Handbook for Kids. Concord, CA: C&T Publishing. pp. 6. ISBN 978-1-60705-973-8.

- ^ The Marian Hanging, worked by Mary Queen of Scots between 1570 and 1585, an embroidered silk velvet in silks and silver-gilt thread, applied canvaswork, lined with silk. V&A Museum Accession No T.29-1955, (presented by the Art Fund) On display at National Trust, Oxburgh Hall, Norfolk.

- ^ Firescreen Panel embroidered by Marie Antoinette, Queen of France Cotton embroidered with silk ca. 1788 The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Gift of Ann Payne Blumenthal, 1941) Accession No: 41.205.3c

- ^ "Princess Grace Award (Needlepoint)". American Needlepoint Guild Incorporated. Archived from the original on 2009-04-28. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ "Princess Grace Awards". Prince Grace Foundation.

- ^ Wharton, Anne Hollingsworth (1923). Colonial Days & Dames. Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott Co., where it states "Mrs. Washington was a notable needlewoman".

- ^ Grier, Rosey (1973). Rosey Grier's Needlepoint for Men.

- ^ Martin, Mary; Mednick, Sol (1969). Mary Martin's Needlepoint. Galahad Books. ISBN 978-0-88365-092-9.

- ^ "Sylvia Sidney, 30s Film Heroine, Dies at 88". The New York Times. 2 July 1999. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- ^ Sidney, Sylvia (1968). Sylvia Sidney Needlepoint Book. New York: Van Norstrand Reinhold Co.

- ^ Sidney, Sylvia (1974). Question and Answer Book on Needlepoint. New York: Van Norstrand Reinhold Co.

- ^ "'Nine Days and Nights of Ed Sheeran': 9 Things to See in MTV's Docuseries Premiere (Video)". Hollywood Reporter. June 10, 2014.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Made Ed Sheeran A Drake Needlepoint, Because Sometimes Famous BFFs Make Each Other Drake Crafts". MTV. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.

- ^ Swit, Loretta (1986). A Needlepoint Scrapbook. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19905-8.

- ^ "The Tapestry Kit Collection: Recommended Stitches".

- ^ e.g. Gordon, Jill Take Up Needlepoint 1994 London, Merehurst ISBN 1-85391-330-8

- ^ e.g. Russell, Beth Traditional Needlepoint 1992 Devon, David & Charles ISBN 0-7153-9984-5

- ^ a b Thomas, Mary; Eaton, Jan (1998). Mary Thomas's dictionary of embroidery stitches (New ed.). North Pomfret, Vt: Trafalgar Square Pub. ISBN 978-1-57076-118-8.

- ^ Christensen, Jo Ippolito, The Needlepoint Book, 2015, New York, Simon & Schuster ISBN 0-684-83230-5

Further reading

[edit]- Reader's Digest Complete Guide to Needlework. The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. (March 1992). ISBN 0-89577-059-8