Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Minimum wage

View on Wikipedia

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century.[1] Because minimum wages increase the cost of labor, companies often try to avoid minimum wage laws by using gig workers, by moving labor to locations with lower or nonexistent minimum wages, or by automating job functions.[2] Minimum wage policies can vary significantly between countries or even within a country, with different regions, sectors, or age groups having their own minimum wage rates. These variations are often influenced by factors such as the cost of living, regional economic conditions, and industry-specific factors.[3]

| Country | Dollars per hour |

|---|---|

| Luxembourg | |

| Germany | |

| United Kingdom | |

| France | |

| Australia | |

| New Zealand | |

| Netherlands | |

| Belgium | |

| Spain | |

| Ireland | |

| Canada | |

| Slovenia | |

| Poland | |

| South Korea | |

| Japan | |

| Lithuania | |

| Portugal | |

| Turkey | |

| Israel | |

| Czechia | |

| Greece | |

| Hungary | |

| Slovakia | |

| Estonia | |

| United States | |

| Latvia | |

| Costa Rica | |

| Chile | |

| Colombia | |

| Mexico |

The movement for minimum wages was first motivated as a way to stop the exploitation of workers in sweatshops, by employers who were thought to have unfair bargaining power over them. Over time, minimum wages came to be seen as a way to help lower-income families. Modern national laws enforcing compulsory union membership which prescribed minimum wages for their members were first passed in New Zealand in 1894.[5] Although minimum wage laws are now in effect in many jurisdictions, differences of opinion exist about the benefits and drawbacks of a minimum wage. Additionally, minimum wage policies can be implemented through various methods, such as directly legislating specific wage rates, setting a formula that adjusts the minimum wage based on economic indicators, or having wage boards that determine minimum wages in consultation with representatives from employers, employees, and the government.[6]

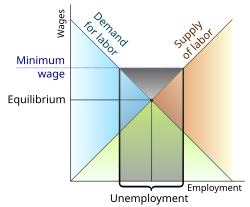

Supply and demand models suggest that there may be employment losses from minimum wages; however, minimum wages can increase the efficiency of the labor market in monopsony scenarios, where individual employers have a degree of wage-setting power over the market as a whole.[7][8][9] Supporters of the minimum wage say it increases the standard of living of workers, reduces poverty, reduces inequality, and boosts morale.[10] In contrast, opponents of the minimum wage say it increases poverty and unemployment because some low-wage workers "will be unable to find work ... [and] will be pushed into the ranks of the unemployed".[11][12][13]

History

[edit]"It is a serious national evil that any class of his Majesty's subjects should receive less than a living wage in return for their utmost exertions. It was formerly supposed that the working of the laws of supply and demand would naturally regulate or eliminate that evil ... [and] ... ultimately produce a fair price. Where ... you have a powerful organisation on both sides ... there you have a healthy bargaining .... But where you have what we call sweated trades, you have no organisation, no parity of bargaining, the good employer is undercut by the bad, and the bad employer is undercut by the worst ... where those conditions prevail you have not a condition of progress, but a condition of progressive degeneration."

Modern minimum wage laws trace their origin to the Ordinance of Labourers (1349), which was a decree by King Edward III that set a maximum wage for laborers in medieval England.[14][15] Edward, who was a wealthy landowner, was dependent, like his lords, on serfs to work the land. In the autumn of 1348, the Black Plague reached England and decimated the population.[16] The severe shortage of labor caused wages to soar and encouraged King Edward III to set a wage ceiling. Subsequent amendments to the ordinance, such as the Statute of Labourers (1351), increased the penalties for paying a wage above the set rates.[14]

While the laws governing wages initially set a ceiling on compensation, they were eventually used to set a living wage. An amendment to the Statute of Labourers in 1389 effectively fixed wages to the price of food. As time passed, the Justice of the Peace, who was charged with setting the maximum wage, also began to set formal minimum wages. The practice was eventually formalized with the passage of the Act Fixing a Minimum Wage in 1604 by King James I for workers in the textile industry.[14]

By the early 19th century, the Statutes of Labourers was repealed as the increasingly capitalistic United Kingdom embraced laissez-faire policies which disfavored regulations of wages (whether upper or lower limits).[14] The subsequent 19th century saw significant labor unrest affect many industrial nations. As trade unions were decriminalized during the century, attempts to control wages through collective agreement were made.

It was not until the 1890s that the first modern legislative attempts to regulate minimum wages were seen in New Zealand and Australia.[17] The movement for a minimum wage was initially focused on stopping sweatshop labor and controlling the proliferation of sweatshops in manufacturing industries.[18] The sweatshops employed large numbers of women and young workers, paying them what were considered to be substandard wages. The sweatshop owners were thought to have unfair bargaining power over their employees, and a minimum wage was proposed as a means to make them pay fairly. Over time, the focus changed to helping people, especially families, become more self-sufficient.[19]

In the United States, the late 19th-century ideas for favoring a minimum wage also coincided with the eugenics movement. As a consequence, some economists at the time, including Royal Meeker and Henry Rogers Seager, argued for the adoption of a minimum wage not only to support the worker, but to support their desired semi- and skilled laborers while forcing the undesired workers (including the idle, immigrants, women, racial minorities, and the disabled) out of the labor market. The result, over the longer term, would be to limit the nondesired workers' ability to earn money and have families, and thereby, remove them from the economists' ideal society.[20]

Minimum wage laws

[edit]"It seems to me to be equally plain that no business which depends for existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country."

The first modern national minimum wages were enacted by the government recognition of unions which in turn established minimum wage policy among their members, as in New Zealand in 1894, followed by Australia in 1896 and the United Kingdom in 1909.[17] In the United States, statutory minimum wages were first introduced nationally in 1938,[23] and they were reintroduced and expanded in the United Kingdom in 1998.[24] There is now legislation or binding collective bargaining regarding minimum wage in more than 90 percent of all countries.[25][1] In the European Union, 21 out of 27 member states currently have national minimum wages.[26] Other countries, such as Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, and Italy, have no minimum wage laws, but rely on employer groups and trade unions to set minimum earnings through collective bargaining.[27][28]

Minimum wage rates vary greatly across many different jurisdictions, not only in setting a particular amount of money—for example $7.25 per hour ($14,500 per year) under certain US state laws (or $2.13 for employees who receive tips, which is known as the tipped minimum wage), $16.28 per hour in the U.S. state of Washington,[29] or £11.44 (for those aged 21+) in the United Kingdom[30]—but also in terms of which pay period (for example Russia and China set monthly minimum wages) or the scope of coverage. Currently the United States federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour, though most states have a higher minimum wage. However, some states do not have a minimum wage law, such as Louisiana and Tennessee, and other states have minimum wages below the federal minimum wage such as Georgia and Wyoming, although the federal minimum wage is enforced in those states.[31] Some jurisdictions allow employers to count tips given to their workers as credit towards the minimum wage levels. India was one of the first developing countries to introduce minimum wage policy in its law in 1948. However, it is rarely implemented, even by contractors of government agencies. In Mumbai, as of 2017, the minimum wage was Rs. 348/day.[32] India also has one of the most complicated systems with more than 1,200 minimum wage rates depending on the geographical region.[33]

Informal minimum wages

[edit]Customs, tight labor markets, and extra-legal pressures from governments or labor unions can each produce a de facto minimum wage. So can international public opinion, by pressuring multinational companies to pay Third World workers wages usually found in more industrialized countries. The latter situation in Southeast Asia and Latin America was publicized in the 2000s, but it existed with companies in West Africa in the middle of the 20th century.[34]

Setting minimum wage

[edit]Among the indicators that might be used to establish an initial minimum wage rate are ones that minimize the loss of jobs while preserving international competitiveness.[35] Among these are general economic conditions as measured by real and nominal gross domestic product; inflation; labor supply and demand; wage levels, distribution and differentials; employment terms; productivity growth; labor costs; business operating costs; the number and trend of bankruptcies; economic freedom rankings; standards of living and the prevailing average wage rate.

In the business sector, concerns include the expected increased cost of doing business, threats to profitability, rising levels of unemployment (and subsequent higher government expenditure on welfare benefits raising tax rates), and the possible knock-on effects to the wages of more experienced workers who might already be earning the new statutory minimum wage, or slightly more.[36] Among workers and their representatives, political considerations weigh in as labor leaders seek to win support by demanding the highest possible rate.[37] Other concerns include purchasing power, inflation indexing and standardized working hours.

Impact of minimum wage on income inequality and poverty

[edit]Minimum wage policies have been debated for their impact on income inequality and poverty levels. Proponents argue that raising the minimum wage can help reduce income disparities, enabling low-income workers to afford basic necessities and contribute to the overall economy. Higher minimum wages may also have a ripple effect, pushing up wages for those earning slightly above the minimum wage.[38]

However, opponents contend that minimum wage increases can lead to job losses, particularly for low-skilled and entry-level workers, as businesses may be unable to afford higher labor costs and may respond by cutting jobs or hours.[39] They also argue that minimum wage increases may not effectively target those living in poverty, as many minimum wage earners are secondary earners in households with higher incomes.[40] Some studies suggest that targeted income support programs, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) in the United States, may be more effective in addressing poverty.[41] The effectiveness of minimum wage policies in reducing income inequality and poverty remains a subject of ongoing debate and research.

Economic models

[edit]Supply and demand model

[edit]

According to the supply and demand model of the labor market shown in many economics textbooks, increasing the minimum wage decreases the employment of minimum-wage workers.[13] One such textbook states:[9]

If a higher minimum wage increases the wage rates of unskilled workers above the level that would be established by market forces, the quantity of unskilled workers employed will fall. The minimum wage will price the services of the least productive (and therefore lowest-wage) workers out of the market. ... the direct results of minimum wage legislation are clearly mixed. Some workers, most likely those whose previous wages were closest to the minimum, will enjoy higher wages. Others, particularly those with the lowest prelegislation wage rates, will be unable to find work. They will be pushed into the ranks of the unemployed.

A firm's cost is an increasing function of the wage rate. The higher the wage rate, the fewer hours an employer will demand of employees. This is because, as the wage rate rises, it becomes more expensive for firms to hire workers and so firms hire fewer workers (or hire them for fewer hours). The demand of labor curve is therefore shown as a line moving down and to the right.[42] Since higher wages increase the quantity supplied, the supply of labor curve is upward sloping, and is shown as a line moving up and to the right.[42] If no minimum wage is in place, wages will adjust until the quantity of labor demanded is equal to quantity supplied, reaching equilibrium, where the supply and demand curves intersect. Minimum wage behaves as a classical price floor on labor. Standard theory says that, if set above the equilibrium price, more labor will be willing to be provided by workers than will be demanded by employers, creating a surplus of labor, i.e. unemployment.[42] The economic model of markets predicts the same of other commodities (like milk and wheat, for example): Artificially raising the price of the commodity tends to cause an increase in quantity supplied and a decrease in quantity demanded. The result is a surplus of the commodity. When there is a wheat surplus, the government buys it. Since the government does not hire surplus labor, the labor surplus takes the form of unemployment, which tends to be higher with minimum wage laws than without them.[34]

The supply and demand model implies that by mandating a price floor above the equilibrium wage, minimum wage laws will cause unemployment.[43][44] This is because a greater number of people are willing to work at the higher wage while a smaller number of jobs will be available at the higher wage. Companies can be more selective in those whom they employ thus the least skilled and least experienced will typically be excluded. An imposition or increase of a minimum wage will generally only affect employment in the low-skill labor market, as the equilibrium wage is already at or below the minimum wage, whereas in higher skill labor markets the equilibrium wage is too high for a change in minimum wage to affect employment.[45]

Monopsony

[edit]

The supply and demand model predicts that raising the minimum wage helps workers whose wages are raised, and hurts people who are not hired (or lose their jobs) when companies cut back on employment. But proponents of the minimum wage hold that the situation is much more complicated than the model can account for. One complicating factor is possible monopsony in the labor market, whereby the individual employer has some market power in determining wages paid. Thus it is at least theoretically possible that the minimum wage may boost employment. Though single employer market power is unlikely to exist in most labor markets in the sense of the traditional 'company town,' asymmetric information, imperfect mobility, and the personal element of the labor transaction give some degree of wage-setting power to most firms.[46]

Modern economic theory predicts that although an excessive minimum wage may raise unemployment as it fixes a price above most demand for labor, a minimum wage at a more reasonable level can increase employment, and enhance growth and efficiency. This is because labor markets are monopsonistic and workers persistently lack bargaining power. When poorer workers have more to spend it stimulates effective aggregate demand for goods and services.[47][48]

Criticisms of the supply and demand model

[edit]The argument that a minimum wage decreases employment is based on a simple supply and demand model of the labor market. A number of economists, such as Pierangelo Garegnani,[49] Robert L. Vienneau,[50] and Arrigo Opocher and Ian Steedman,[51] building on the work of Piero Sraffa, argue that that model, even given all its assumptions, is logically incoherent. Michael Anyadike-Danes and Wynne Godley argue, based on simulation results, that little of the empirical work done with the textbook model constitutes a potentially falsifiable theory, and consequently empirical evidence hardly exists for that model.[52] Graham White argues, partially on the basis of Sraffianism, that the policy of increased labor market flexibility, including the reduction of minimum wages, does not have an "intellectually coherent" argument in economic theory.[53]

Gary Fields, Professor of Labor Economics and Economics at Cornell University, argues that the standard textbook model for the minimum wage is ambiguous, and that the standard theoretical arguments incorrectly measure only a one-sector market. Fields says a two-sector market, where "the self-employed, service workers, and farm workers are typically excluded from minimum-wage coverage ... [and with] one sector with minimum-wage coverage and the other without it [and possible mobility between the two]," is the basis for better analysis. Through this model, Fields shows the typical theoretical argument to be ambiguous and says "the predictions derived from the textbook model definitely do not carry over to the two-sector case. Therefore, since a non-covered sector exists nearly everywhere, the predictions of the textbook model simply cannot be relied on."[54]

An alternate view of the labor market has low-wage labor markets characterized as monopsonistic competition wherein buyers (employers) have significantly more market power than do sellers (workers). This monopsony could be a result of intentional collusion between employers, or naturalistic factors such as segmented markets, search costs, information costs, imperfect mobility and the personal element of labor markets.[citation needed] Such a case is a type of market failure and results in workers being paid less than their marginal value. Under the monopsonistic assumption, an appropriately set minimum wage could increase both wages and employment, with the optimal level being equal to the marginal product of labor.[55] This view emphasizes the role of minimum wages as a market regulation policy akin to antitrust policies, as opposed to an illusory "free lunch" for low-wage workers.

Another reason minimum wage may not affect employment in certain industries is that the demand for the product the employees produce is highly inelastic.[56] For example, if management is forced to increase wages, management can pass on the increase in wage to consumers in the form of higher prices. Since demand for the product is highly inelastic, consumers continue to buy the product at the higher price and so the manager is not forced to lay off workers. Economist Paul Krugman argues this explanation neglects to explain why the firm was not charging this higher price absent the minimum wage.[57]

Three other possible reasons minimum wages do not affect employment were suggested by Alan Blinder: higher wages may reduce turnover, and hence training costs; raising the minimum wage may "render moot" the potential problem of recruiting workers at a higher wage than current workers; and minimum wage workers might represent such a small proportion of a business' cost that the increase is too small to matter. He admits that he does not know if these are correct, but argues that "the list demonstrates that one can accept the new empirical findings and still be a card-carrying economist".[58]

Mathematical models of the minimum wage and frictional labor markets

[edit]The following mathematical models are more quantitative in orientation, and highlight some of the difficulties in determining the impact of the minimum wage on labor market outcomes.[59] Specifically, these models focus on labor markets with frictions and may result in positive or negative outcomes from raising the minimum wage, depending on the circumstances.

Welfare and labor market participation

[edit]This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (September 2022) |

Assume that the decision to participate in the labor market results from a trade-off between being an unemployed job seeker and not participating at all. All individuals whose expected utility outside the labor market is less than the expected utility of an unemployed person decide to participate in the labor market. In the basic search and matching model, the expected utility of unemployed persons and that of employed persons are defined by:

Let be the wage, the interest rate, the instantaneous income of unemployed persons, the exogenous job destruction rate, the labor market tightness, and the job finding rate. The profits and expected from a filled job and a vacant one are:where is the cost of a vacant job and is the productivity. When the free entry condition is satisfied, these two equalities yield the following relationship between the wage and labor market tightness :

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labor |

|---|

|

If represents a minimum wage that applies to all workers, this equation completely determines the equilibrium value of the labor market tightness . There are two conditions associated with the matching function:This implies that is a decreasing function of the minimum wage , and so is the job finding rate . A hike in the minimum wage degrades the profitability of a job, so firms post fewer vacancies and the job finding rate falls off. Now let's rewrite to be:Using the relationship between the wage and labor market tightness to eliminate the wage from the last equation gives us: By maximizing in this equation, with respect to the labor market tightness, it follows that:where is the elasticity of the matching function:This result shows that the expected utility of unemployed workers is maximized when the minimum wage is set at a level that corresponds to the wage level of the decentralized economy in which the bargaining power parameter is equal to the elasticity . The level of the negotiated wage is .

If , then an increase in the minimum wage increases participation and the unemployment rate, with an ambiguous impact on employment. When the bargaining power of workers is less than , an increase in the minimum wage improves the welfare of the unemployed – this suggests that minimum wage hikes can improve labor market efficiency, at least up to the point when bargaining power equals .

Job search effort

[edit]This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. (September 2022) |

In the model just presented, the minimum wage always increases unemployment. This result does not necessarily hold when the search effort of workers is endogenous.

Consider a model where the intensity of the job search is designated by the scalar , which can be interpreted as the amount of time and/or intensity of the effort devoted to search. Assume that the arrival rate of job offers is and that the wage distribution is degenerated to a single wage . Denote to be the cost arising from the search effort, with . Then the discounted utilities are given by:Therefore, the optimal search effort is such that the marginal cost of performing the search is equation to the marginal return:This implies that the optimal search effort increases as the difference between the expected utility of the job holder and the expected utility of the job seeker grows. In fact, this difference actually grows with the wage. To see this, take the difference of the two discounted utilities to find:Then differentiating with respect to and rearranging gives us:where is the optimal search effort. This implies that a wage increase drives up job search effort and, therefore, the job finding rate. Additionally, the unemployment rate at equilibrium is given by:A hike in the wage, which increases the search effort and the job finding rate, decreases the unemployment rate. So it is possible that a hike in the minimum wage may, by boosting the search effort of job seekers, boost employment. Taken in sum with the previous section, the minimum wage in labor markets with frictions can improve employment and decrease the unemployment rate when it is sufficiently low. However, a high minimum wage is detrimental to employment and increases the unemployment rate.

Empirical studies

[edit]

Economists disagree as to the measurable impact of minimum wages in practice. This disagreement usually takes the form of competing empirical tests of the elasticities of supply and demand in labor markets and the degree to which markets differ from the efficiency that models of perfect competition predict.

Economists have done empirical studies on different aspects of the minimum wage, including:[19]

- Employment effects, the most frequently studied aspect

- Effects on the distribution of wages and earnings among low-paid and higher-paid workers

- Effects on the distribution of incomes among low-income and higher-income families

- Effects on the skills of workers through job training and the deferring of work to acquire education

- Effects on prices and profits

- Effects on on-the-job training

Until the mid-1990s, a general consensus existed among economists–both conservative and liberal–that the minimum wage reduced employment, especially among younger and low-skill workers.[13] In addition to the basic supply-demand intuition, there were a number of empirical studies that supported this view. For example, Edward Gramlich in 1976 found that many of the benefits went to higher income families, and that teenagers were made worse off by the unemployment associated with the minimum wage.[61]

Brown et al. (1983) noted that time series studies to that point had found that for a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage, there was a decrease in teenage employment of 1–3 percent. However, the studies found wider variation, from 0 to over 3 percent, in their estimates for the effect on teenage unemployment (teenagers without a job and looking for one). In contrast to the simple supply and demand diagram, it was commonly found that teenagers withdrew from the labor force in response to the minimum wage, which produced the possibility of equal reductions in the supply as well as the demand for labor at a higher minimum wage and hence no impact on the unemployment rate. Using a variety of specifications of the employment and unemployment equations (using ordinary least squares vs. generalized least squares regression procedures, and linear vs. logarithmic specifications), they found that a 10 percent increase in the minimum wage caused a 1 percent decrease in teenage employment, and no change in the teenage unemployment rate. The study also found a small, but statistically significant, increase in unemployment for adults aged 20–24.[62]

Wellington (1991) updated Brown et al.'s research with data through 1986 to provide new estimates encompassing a period when the real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) value of the minimum wage was declining, because it had not increased since 1981. She found that a 10% increase in the minimum wage decreased the absolute teenage employment by 0.6%, with no effect on the teen or young adult unemployment rates.[63]

Some research suggests that the unemployment effects of small minimum wage increases are dominated by other factors.[64] In Florida, where voters approved an increase in 2004, a follow-up comprehensive study after the increase confirmed a strong economy with increased employment above previous years in Florida and better than in the US as a whole.[65] When it comes to on-the-job training, some believe the increase in wages is taken out of training expenses. A 2001 empirical study found that there is "no evidence that minimum wages reduce training, and little evidence that they tend to increase training".[66]

The Economist wrote in December 2013: "A minimum wage, providing it is not set too high, could thus boost pay with no ill effects on jobs....America's federal minimum wage, at 38% of median income, is one of the rich world's lowest. Some studies find no harm to employment from federal or state minimum wages, others see a small one, but none finds any serious damage. ... High minimum wages, however, particularly in rigid labour markets, do appear to hit employment. France has the rich world's highest wage floor, at more than 60% of the median for adults and a far bigger fraction of the typical wage for the young. This helps explain why France also has shockingly high rates of youth unemployment: 26% for 15- to 24-year-olds."[67]

A 2019 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics found that minimum wage increases did not have an impact on the overall number of low-wage jobs in the five years subsequent to the wage increase. However, it did find disemployment in 'tradable' sectors, defined as those sectors most reliant on entry-level or low-skilled labor.[68]

A 2018 study published by the university of California agrees with the study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics and discusses how minimum wages actually cause fewer jobs for low-skilled workers. Within the article it discusses a trade-off for low- to high-skilled workers that when the minimum wage is increased GDP is more highly redistributed to high academia jobs.[69]

In another study, which shared authors with the above, published in the American Economic Review found that a large and persistent increase in the minimum wage in Hungary produced some disemployment, with the large majority of additional cost being passed on to consumers. The authors also found that firms began substituting capital for labor over time.[70]

A 2013 study published in the Science Direct journal agrees with the studies above as it describes that there is not a significant employment change due to increases in minimum wage. The study illustrates that there is not a-lot of national generalisability for minimum wage effects, studies done on one country often get generalised to others. Effect on employment can be low from minimum-wage policies, but these policies can also benefit welfare and poverty.[71]

David Card and Alan Krueger

[edit]In 1992, the minimum wage in New Jersey increased from $4.25 to $5.05 per hour (an 18.8% increase), while in the adjacent state of Pennsylvania it remained at $4.25. David Card and Alan Krueger gathered information on fast food restaurants in New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania in an attempt to see what effect this increase had on employment within New Jersey via a Difference in differences model. A basic supply and demand model predicts that relative employment should have decreased in New Jersey. Card and Krueger surveyed employers before the April 1992 New Jersey increase, and again in November–December 1992, asking managers for data on the full-time equivalent staff level of their restaurants both times.[72] Based on data from the employers' responses, the authors concluded that the increase in the minimum wage slightly increased employment in the New Jersey restaurants.[72]

Card and Krueger expanded on this initial article in their 1995 book Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage.[73] They argued that the negative employment effects of minimum wage laws are minimal if not non-existent. For example, they look at the 1992 increase in New Jersey's minimum wage, the 1988 rise in California's minimum wage, and the 1990–91 increases in the federal minimum wage. In addition to their own findings, they reanalyzed earlier studies with updated data, generally finding that the older results of a negative employment effect did not hold up in the larger datasets.[74] This had major implications on policy, challenging long-held economic views that increasing minimum wage led to deadweight loss.

Research after Card's and Krueger's work

[edit]

In 1996, David Neumark and William Wascher reexamined Card and Krueger's results using payroll records from large fast-food chains, reporting that minimum wage increases led to decreases in employment. Their initial findings did not contradict Card and Krueger, but a later version showed a four percent decrease in employment, with statistically significant disemployment effects in some cases.[76] Card and Krueger rebutted these conclusions in a 2000 paper.[77]

A 2011 paper reconciled differences between datasets, showing positive employment effects for small restaurants but negative effects for large fast-food chains.[78] A 2014 analysis found that minimum wage reduces employment among teenagers.[79]

A 2010 study using Card and Krueger's methodology supported their original findings, showing no negative effects on low-wage employment.[80]

A 2011 study by Baskaya and Rubinstein found that federal minimum wage increases negatively impacted employment, particularly among teenagers.[81] Other studies, including a 2012 study by Sabia, Hansen, and Burkhauser, found substantial adverse effects on low-skilled employment, particularly among young workers.[82]

A 2019 paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics argued that job losses in studies like those of Meer and West, who found that a minimum wage "significantly reduces rates of job growth", are driven by unrealistic assumptions and that minimum wage effects are more complex.[83] Another 2013 study by Fang and Lin found significant adverse effects on employment in China, particularly among women, young adults, and low-skilled workers.[84]

A 2017 study in Seattle found that increasing the minimum wage to $13 per hour led to reduced income for low-wage workers due to decreased hours worked, as businesses adjusted to higher labor costs.[85] A 2019 study in Arizona suggested that smaller minimum wage increases might lead to slight economic growth without significantly distorting labor markets.[86]

In 2019, economists from Georgia Tech found that minimum wage increases could harm small businesses by increasing bankruptcy rates and reducing hiring, with significant impacts on minority-owned businesses.[87]

The Congressional Budget Office's 2019 report on a proposed $15 federal minimum wage predicted modest improvements in take-home pay for those who retained employment but warned of potential job losses, reduced hours, and increased costs of goods and services.[88] Similarly, a 2019 study found that increasing the minimum wage could lead to increased crime among young adults.[89]

Studies from Denmark and Spain further highlighted that significant minimum wage increases could lead to substantial job losses, particularly among young workers.[90][91] A 2021 study on Germany's minimum wage found that while wages increased without reducing employment, there were significant structural shifts in the economy, including reduced competition and increased commuting times for workers.[92]

A 2010 study on the UK minimum wage found that it did not cause immediate price increases but led to faster price rises in sectors with many low-wage workers over the long term.[93] A 2012 UK study (1997–2007) found the minimum wage reduced wage inequality and had neutral to positive effects on employment.[94] Another 2012 UK study found no "spill-over" effects from the minimum wage on higher-earning brackets.[95] A 2016 US study associated the minimum wage with reduced wage inequality and possible spill-over effects, though these might be due to measurement error.[96]

Meta-analyses

[edit]- A 2013 meta-analysis of 16 UK studies found no significant employment effects from the minimum wage.[97]

- A 2007 meta-analysis by Neumark found a consistent, though not always significant, negative effect on employment.[98]

- A 2019 meta-analysis of developed countries reported minimal employment effects and significant earnings increases for low-paid workers.[99]

In 1995, Card and Krueger noted evidence of publication bias in time-series studies on minimum wages, which favored studies showing negative employment effects.[100] A 2005 study by T.D. Stanley confirmed this bias and suggested no clear link between the minimum wage and unemployment.[101] A 2008 meta-analysis by Doucouliagos and Stanley supported Card and Krueger's findings, showing little to no negative association between minimum wages and employment after correcting for publication bias.[102]

Debate over consequences

[edit]

Minimum wage laws affect workers in most low-paid fields of employment[19] and have usually been judged against the criterion of reducing poverty.[103] Minimum wage laws receive less support from economists than from the general public. Despite decades of experience and economic research, debates about the costs and benefits of minimum wages continue today.[19]

Various groups have great ideological, political, financial, and emotional investments in issues surrounding minimum wage laws. For example, agencies that administer the laws have a vested interest in showing that "their" laws do not create unemployment, as do labor unions whose members' finances are protected by minimum wage laws. On the other side of the issue, low-wage employers such as restaurants finance the Employment Policies Institute, which has released numerous studies opposing the minimum wage.[104][105] The presence of these powerful groups and factors means that the debate on the issue is not always based on dispassionate analysis. Additionally, it is extraordinarily difficult to separate the effects of minimum wage from all the other variables that affect employment.[34]

Studies have found that minimum wages have the following positive effects:

- Improves functioning of the low-wage labor market which may be characterized by employer-side market power (monopsony).[106][107]

- Raises family incomes at the bottom of the income distribution, and lowers poverty.[108][109]

- Positive impact on small business owners and industry.[110]

- Encourages education,[111] resulting in better paying jobs.

- Increases incentives to take jobs, as opposed to other methods of transferring income to the poor that are not tied to employment (such as food subsidies for the poor or welfare payments for the unemployed).[112]

- Increased job growth and creation.[113][114]

- Encourages efficiency and automation of industry.[115]

- Removes low paying jobs, forcing workers to train for, and move to, higher paying jobs.[116][117]

- Increases technological development. Costly technology that increases business efficiency is more appealing as the price of labor increases.[118]

- Encourages people to join the workforce rather than pursuing money through illegal means, e.g., selling illegal drugs[119]

Studies have found the following negative effects:

- Minimum wage alone is not effective at alleviating poverty, and in fact produces a net increase in poverty due to disemployment effects.[120]

- As a labor market analogue of political-economic protectionism, it excludes low cost competitors from labor markets and hampers firms in reducing wage costs during trade downturns. This generates various industrial-economic inefficiencies.[121]

- Reduces quantity demanded of workers, either through a reduction in the number of hours worked by individuals, or through a reduction in the number of jobs.[122][123]

- Wage/price spiral

- Encourages employers to replace low-skilled workers with computers, such as self-checkout machines.[124]

- Increases property crime and misery in poor communities by decreasing legal markets of production and consumption in those communities;[125]

- Can result in the exclusion of certain groups (ethnic, gender etc.) from the labor force.[126]

- Is less effective than other methods (e.g. the Earned Income Tax Credit) at reducing poverty, and is more damaging to businesses than those other methods.[127]

- Discourages further education among the poor by enticing people to enter the job market.[127]

- Discriminates against, through pricing out, less qualified workers (including newcomers to the labor market, e.g. young workers) by keeping them from accumulating work experience and qualifications, hence potentially graduating to higher wages later.[11]

- Slows growth in the creation of low-skilled jobs[128]

- Results in jobs moving to other areas or countries which allow lower-cost labor.[129]

- Results in higher long-term unemployment.[130]

- Results in higher prices for consumers, where products and services are produced by minimum-wage workers[131] (though non-labor costs represent a greater proportion of costs to consumers in industries like fast food and discount retail)[132][133]

A widely circulated argument that the minimum wage was ineffective at reducing poverty was provided by George Stigler in 1949:

- Employment may fall more than in proportion to the wage increase, thereby reducing overall earnings;

- As uncovered sectors of the economy absorb workers released from the covered sectors, the decrease in wages in the uncovered sectors may exceed the increase in wages in the covered ones;

- The impact of the minimum wage on family income distribution may be negative unless the fewer but better jobs are allocated to members of needy families rather than to, for example, teenagers from families not in poverty;

- Forbidding employers to pay less than a legal minimum is equivalent to forbidding workers to sell their labor for less than the minimum wage. The legal restriction that employers cannot pay less than a legislated wage is equivalent to the legal restriction that workers cannot work at all in the protected sector unless they can find employers willing to hire them at that wage.[103] That may be seen as a legal violation of human right to work in its most basic interpretation as "a right to engage in productive employment, and not to be prevented from doing so".

In 2006, the International Labour Organization (ILO) argued that the minimum wage could not be directly linked to unemployment in countries that have suffered job losses.[1] In April 2010, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released a report arguing that countries could alleviate teen unemployment by "lowering the cost of employing low-skilled youth" through a sub-minimum training wage.[134] A study of U.S. states showed that businesses' annual and average payrolls grow faster and employment grew at a faster rate in states with a minimum wage.[135] The study showed a correlation, but did not claim to prove causation.

Although strongly opposed by both the business community and the Conservative Party when introduced in the UK in 1999, the Conservatives reversed their opposition in 2000.[136] Accounts differ as to the effects of the minimum wage. The Centre for Economic Performance found no discernible impact on employment levels from the wage increases,[137] while the Low Pay Commission found that employers had reduced their rate of hiring and employee hours employed, and found ways to cause current workers to be more productive (especially service companies).[138] The Institute for the Study of Labor found prices in minimum wage sectors[a] rose faster than other sectors, especially in the four years after its introduction.[93] Neither trade unions nor employer organizations contest the minimum wage, although the latter had especially done so heavily until 1999.

In 2014, supporters of minimum wage cited a study that found that job creation within the United States is faster in states that raised their minimum wages.[113][139][140] In 2014, supporters of minimum wage cited news organizations who reported the state with the highest minimum-wage garnered more job creation than the rest of the United States.[113][141][142][143][144][145][146]

In 2014, in Seattle, Washington, liberal and progressive business owners who had supported the city's new $15 minimum wage said they might hold off on expanding their businesses and thus creating new jobs, due to the uncertain timescale of the wage increase implementation.[147] However, subsequently at least two of the business owners quoted did expand.[148][149]

With regard to the economic effects of introducing minimum wage legislation in Germany in January 2015, recent developments have shown that the feared increase in unemployment has not materialized, however, in some economic sectors and regions of the country, it came to a decline in job opportunities particularly for temporary and part-time workers, and some low-wage jobs have disappeared entirely.[150] Because of this overall positive development, the Deutsche Bundesbank revised its opinion, and ascertained that "the impact of the introduction of the minimum wage on the total volume of work appears to be very limited in the present business cycle".[151]

A 2019 study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine showed that in the United States, those states that have implemented a higher minimum wage saw a decline in the growth of suicide rates. The researchers say that for every one dollar increase, the annual suicide growth rate fell by 1.9%. The study covers all 50 states for the years 2006 to 2016.[152]

According to a 2020 US study, the cost of 10% minimum wage increases for grocery store workers was fully passed through to consumers as 0.4% higher grocery prices.[153] Similarly, a 2021 study that covered 10,000 McDonald's restaurants in the US found that between 2016 and 2020, the cost of 10% minimum wage increases for McDonald's workers were passed through to customers as 1.4% increases in the price of a Big Mac.[154][155] This results in minimum wage workers getting a lesser increase in their "real wage" than in their nominal wage, because any goods and services they purchase made with minimum-wage labor have now increased in cost, analogous to an increase in the sales tax.[156]

According to a 2019 review of the academic literature by Arindrajit Dube, "overall, the most up to date body of research from US, UK and other developed countries points to a very muted effect of minimum wages on employment, while significantly increasing the earnings of low paid workers."[99]

According to a 2021 study "The Minimum Wage, EITC, and Criminal Recidivism" a minimum wage increase of $0.50 reduces the probability an ex-incarcerated individual returns to prison within 3 years by 2.15%; these reductions come mainly from recidivism of property and drug crimes.[157]

Surveys of economists

[edit]There used to be agreement among economists that the minimum wage adversely affected employment, but that consensus shifted in the early 1990s due to new research findings. According to one 2021 assessment, "there is no consensus on the employment effects of the minimum wage".[158]

According to a 1978 article in the American Economic Review, 90% of the economists surveyed agreed that the minimum wage increases unemployment among low-skilled workers.[159] By 1992 the survey found 79% of economists in agreement with that statement,[160] and by 2000, 46% were in full agreement with the statement and 28% agreed with provisos (74% total).[161][162] The authors of the 2000 study also reweighted data from a 1990 sample to show that at that time 62% of academic economists agreed with the statement above, while 20% agreed with provisos and 18% disagreed. They state that the reduction on consensus on this question is "likely" due to the Card and Krueger research and subsequent debate.[163]

A similar survey in 2006 by Robert Whaples polled PhD members of the American Economic Association (AEA). Whaples found that 47% respondents wanted the minimum wage eliminated, 38% supported an increase, 14% wanted it kept at the current level, and 1% wanted it decreased.[164] Another survey in 2007 conducted by the University of New Hampshire Survey Center found that 73% of labor economists surveyed in the United States believed 150% of the then-current minimum wage would result in employment losses and 68% believed a mandated minimum wage would cause an increase in hiring of workers with greater skills. 31% felt that no hiring changes would result.[165]

Surveys of labor economists have found a sharp split on the minimum wage. Fuchs et al. (1998) polled labor economists at the top 40 research universities in the United States on a variety of questions in the summer of 1996. Their 65 respondents were nearly evenly divided when asked if the minimum wage should be increased. They argued that the different policy views were not related to views on whether raising the minimum wage would reduce teen employment (the median economist said there would be a reduction of 1%), but on value differences such as income redistribution.[166] Daniel B. Klein and Stewart Dompe conclude, on the basis of previous surveys, "the average level of support for the minimum wage is somewhat higher among labor economists than among AEA members."[167]

In 2007, Klein and Dompe conducted a non-anonymous survey of supporters of the minimum wage who had signed the "Raise the Minimum Wage" statement published by the Economic Policy Institute. 95 of the 605 signatories responded. They found that a majority signed on the grounds that it transferred income from employers to workers, or equalized bargaining power between them in the labor market. In addition, a majority considered disemployment to be a moderate potential drawback to the increase they supported.[167]

In 2013, a diverse group of 37 economics professors was surveyed on their view of the minimum wage's impact on employment. 34% of respondents agreed with the statement, "Raising the federal minimum wage to $9 per hour would make it noticeably harder for low-skilled workers to find employment." 32% disagreed and the remaining respondents were uncertain or had no opinion on the question. 47% agreed with the statement, "The distortionary costs of raising the federal minimum wage to $9 per hour and indexing it to inflation are sufficiently small compared with the benefits to low-skilled workers who can find employment that this would be a desirable policy", while 11% disagreed.[168]

Alternatives

[edit]Economists and other political commentators have proposed alternatives to the minimum wage. They argue that these alternatives may address the issue of poverty better than a minimum wage, as it would benefit a broader population of low wage earners, not cause any unemployment, and distribute the costs widely rather than concentrating it on employers of low wage workers.

Basic income

[edit]A basic income (or negative income tax – NIT) is a system of social security that periodically provides each citizen with a sum of money that is sufficient to live on frugally. Supporters of the basic-income idea argue that recipients of the basic income would have considerably more bargaining power when negotiating a wage with an employer, as there would be no risk of destitution for not taking the employment. As a result, jobseekers could spend more time looking for a more appropriate or satisfying job, or they could wait until a higher-paying job appeared. Alternatively, they could spend more time increasing their skills (via education and training), which would make them more suitable for higher-paying jobs, as well as provide numerous other benefits. Experiments on Basic Income and NIT in Canada and the United States show that people spent more time studying while the program[which?] was running.[169][need quotation to verify]

Proponents argue that a basic income that is based on a broad tax base would be more economically efficient than a minimum wage, as the minimum wage effectively imposes a high marginal tax on employers, causing losses in efficiency.[citation needed]

Guaranteed minimum income

[edit]A guaranteed minimum income is another proposed system of social welfare provision. It is similar to a basic income or negative income tax system, except that it is normally conditional and subject to a means test. Some proposals also stipulate a willingness to participate in the labor market, or a willingness to perform community services.[170]

Refundable tax credit

[edit]A refundable tax credit is a mechanism whereby the tax system can reduce the tax owed by a household to below zero, and result in a net payment to the taxpayer beyond their own payments into the tax system. Examples of refundable tax credits include the earned income tax credit and the additional child tax credit in the US, and working tax credits and child tax credits in the UK. Such a system is slightly different from a negative income tax, in that the refundable tax credit is usually only paid to households that have earned at least some income. This policy is more targeted against poverty than the minimum wage, because it avoids subsidizing low-income workers who are supported by high-income households (for example, teenagers still living with their parents).[171]

In the United States, earned income tax credit rates, also known as EITC or EIC, vary by state—some are refundable while other states do not allow a refundable tax credit.[172] The federal EITC program has been expanded by a number of presidents including Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton.[173] In 1986, President Reagan described the EITC as "the best anti-poverty, the best pro-family, the best job creation measure to come out of Congress."[174] The ability of the earned income tax credit to deliver larger monetary benefits to the poor workers than an increase in the minimum wage and at a lower cost to society was documented in a 2007 report by the Congressional Budget Office.[175]

The Adam Smith Institute prefers cutting taxes on the poor and middle class instead of raising wages as an alternative to the minimum wage.[176]

Collective bargaining

[edit]Italy, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Denmark are developed nations where legislation stipulates no minimum wage.[26][28] Instead, minimum wage standards in different sectors are set by collective bargaining.[177] Particularly the Scandinavian countries have very high union participation rates.[178]

Wage subsidies

[edit]Some economists such as Scott Sumner[179] and Edmund Phelps[180] advocate a wage subsidy program. A wage subsidy is a payment made by a government for work people do. It is based either on an hourly basis or by income earned.[181][182] Wage subsidies lack political support from either major political party in the United States.[183][184]

Education and training

[edit]Providing education or funding apprenticeships or technical training can provide a bridge for low skilled workers to move into wages above a minimum wage. For example, Germany has adopted a state funded apprenticeship program that combines on-the-job and classroom training.[185] Having more skills makes workers more valuable and more productive, but having a high minimum wage for low-skill jobs reduces the incentive to seek education and training.[186] Moving some workers to higher-paying jobs will decrease the supply of workers willing to accept low-skill jobs, increasing the market wage for those low skilled jobs (assuming a stable labor market). However, in that solution the wage will still not increase above the marginal return for the role and will likely promote automation or business closure.

By country

[edit]Argentina

[edit]

The minimum wage was introduced in Argentina in 1945, by Juan Domingo Perón, when he was Secretary of Labour during the government of Edelmiro Farrell.[187] When Perón became president, he added it to the Constitutional Reform of 1949, however, the dictatorship that overthrew his government in 1955 eliminated the constitutional hierarchy the minimum wage that obtained.

In 1964, the minimum wage was reincorporated by the Congress in the Law 16.459[188]

In the Constitutional reform of 1994, the minimum wage obtained once again constitutional hierarchy.

The minimum wage is defined by the National Council for Employment, Productivity and Minimum, Vital and Mobile Wage, which is formed by Union representatives, business entities and the government.

Armenia

[edit]The concept of the national minimum wage emerged in Armenia in 1995. Since then, it has been increasing, on average, every couple of years. The longest unchanged streak of the national minimum wage was between 1999 and 2003, when it was set at 5,000 AMD, and between 2015 and 2019 where it was set at 55,000 AMD. In November 2022, the national minimum wage was subject to the latest increase. It was set at 75,000 AMD.[189][190]

Australia

[edit]In Australia, the Fair Work Commission (FWC) is responsible for determining and setting a national minimum wage as well as the minimum wages in awards setting wage rates for particular occupations and industries. The Fair Work Act 2009 establishes an Expert panel tasked with providing and maintaining a safety net of a fair minimum wage. The Expert panel is made up of the president of the panel, three full time commission members, and three part time commission members. All members must have experience in workplace relations, economics, social policy or business, industry and commerce and can inform its decision making through commissioning a range of economic and social research.[191]

The legislative framework requires that, in setting minimum wages, the Expert Panel is required to take into account the current state of the economy, including inflation, business competitiveness, productivity and employment growth. In addition, the Expert panel must also consider the social goals of the promotion of social inclusion, the standard of living of the low paid, equal remuneration for work of equal or comparable value and reasonable wages for junior employees, employees whose jobs have training requirements and employees with disability.[192] See Fair Work Act 2009 for more information.

The Expert panel conducts yearly wage reviews, to determine if the minimum wage needs to be adjusted based on the economy's current and projected performance. The annual minimum wage review decisions in 2016–17 found, based on research tendered and submissions to the review, that moderate increases to minimum wages do not inhibit workplace participation or result in disemployment. This position was carried over to the 2017–18 and 2018–19 decisions[192] and informed the decisions including the 2018–19 decision which delivered a minimum wage increase of 3% when the corresponding headline rate of inflation was 1.3%.[193] In the annual minimum wage review decisions of 2019–20 and 2020–21, the FWC was considerably more constrained in setting minimum wages due to uncertain economic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020–21 decision noted the uncertainty of the impact of increases in the minimum wages for youth employment.[194]

Lebanon

[edit]After two years of constant financial meltdown, Lebanon as of 2021 is ranking as one of the 10 countries in the world with the lowest minimum wages because of the collapse of the local pound following the Lebanese financial crisis that started in August 2019.[195]

The minimum monthly wage set at LBP 675,000, which valued USD 450 prior to the crisis, is barely reaching USD 30 nowadays.[196] The currency has lost nearly 90% of its value and drove three quarters of residents into poverty.[197]

Article 44 of the Lebanese Code of Labor states that, "the minimum pay must be sufficient to meet the essential needs of the wage-earner or salary-earner and his family", and according to Article 46, "the minimum pay assessed shall be rectified whenever economic circumstances render such review necessary".[198]

Republic of Ireland

[edit]The national minimum wage was introduced in the Republic of Ireland in April 2000. Prior to this, minimum wages were set by industry-specific Joint Labour Committees. However, coverage for workers was low and the agreements were poorly enforced and moreover, those who were covered by agreements received low wages.

As of April 2000, the government introduced a national minimum wage of €5.58 per hour. The minimum wage increased regularly in the period from 2000 to 2007 and reached €8.65 per hour in July 2007. As the global economic downturn hit the country in 2008, there was no further wage increases until 2016 when the minimum wage was increased to 9.15.

Before the 2019, there existed specific categories of employees that earned sub-minimum wage rates, expressed as a percentage of the full rate of pay. Employees under the age of 18 were eligible to earn 70 per cent of the minimum wage, employees in the first year of employment were eligible to earn 80 per cent, employees in the second year of full employment were eligible to earn 90 per cent and employees in structured training during working hours were eligible to earn 75, 80 or 90 per cent depending on their level of progression. This framework has since been abolished in place of a framework based on the age of the employee.[199]

As of 1 January 2022, the minimum wage is €10.50. Those aged 20 and over are eligible to receive 100 percent of the minimum wage. Those under the age of 18 are eligible to receive 70 percent of the minimum wage, those aged 18 are eligible to receive 80 percent of the minimum wage and those aged 19 are eligible receive 90 percent of the minimum wage.[200]

South Korea

[edit]

The South Korean government enacted the Minimum Wage Act on December 31, 1986. The Minimum Wage System began on January 1, 1988. At this time the economy was booming,[201] and the minimum wage set by the government was less than 30 percent of that of other workers. The Minister of Employment and Labor in Korea asks the Minimum Wage Commission to review the minimum wage by March 31 every year. The Minimum Wage Commission must submit the minimum wage bill within 90 days after the request has been received by the 27 committee members. If there is no objection, the new minimum wage will then take effect from January 1. The minimum wage committee decided to raise the minimum wage in 2018 by 16.4% from the previous year to 7,530 won (US$7.03) per hour. This is the largest increase since 2001 when it was increased by 16.8%.

However, the government officially admitted that the policy of raising the minimum wage to 10,000 won by 2020, which had been the initial target but which the government had been forced to forego, had also caused a great burden on self-employed businesses and deteriorated the job market.[202] In addition, there are opinions from various media that the minimum wage law is not properly applied in Korea.[203][204]Spain

[edit]The Spanish government sets the "Interprofessional Minimum Wage" (SMI) annually, after consulting with the most representative trade unions and business associations, for both permanent and temporary workers, as well as for domestic employees. It takes into account the consumer price index, national average productivity, the increase in labor's share in national income, and the general economic situation.[205][206]

The SMI can be revised semi-annually if the government's predictions about the consumer price index are not met. The amount set is a minimum wage, so it can be exceeded by a collective agreement or individual agreement with the company. The revision of the SMI does not affect the structure or amount of professional salaries being paid to workers when they are superior to the established minimum wage. Finally, the amount of the SMI is non-seizable.

The minimum wage was introduced in Spain in 1963 through Decree 55/1963, proposed by Jesús Romeo Gorría, the Minister of Labor during Francisco Franco's IX Government. The purpose was to ensure fair remuneration for all workers, adjusting wages to labor and economic conditions and advocating for salary equity. It was set at 1,800 pesetas/month (25,200 pesetas/year, 12 monthly payments plus 2 extra payments, as its customary in Spain as to this day), equivalent to 10.80 euros at the time but only 400 euros in today's prices.

In the years following Franco's death in 1975, the minimum wage gradually increased, reaching 50.49 euros (8,400 pesetas) that year, which is equivalent to 657.23 euros in today's currency.[207] Over the years, the minimum wage continued to rise, with several revisions along the way. In 2022, the Spanish government set the minimum wage at 33.33 euros per day or 1,000 euros per month, effective from January 1. This represents a 47% increase from the previous minimum wage set in 2018 at 735.90 euros.[208]

There are several debates around the minimum wage in Spain, which focus on its impact on employment and inflation. While some argue that increasing the minimum wage can be a useful tool to increase the incomes of low-income families and reduce poverty, others have doubts about its effectiveness in achieving these goals.

For instance, an analysis conducted by BCE (Central Bank of Spain, by its initials in spanish) in 2019 on the impact of the 2017 increase in the minimum wage showed a negative effect on the probability of maintaining employment among affected workers, which was particularly significant for older workers.[209]

Additionally, the 2022 raise of the minimum wage revived the debate about the relationship between inflation and the SMI, with some arguing that the increase in the minimum wage could potentially contribute to inflation. The debate centres on whether it's a useful tool to help maintain the purchasing power of those who retain their jobs, or it's not effective because it adds pressure to the growth of prices and increase the likelihood of inflation becoming entrenched.[210]

United Kingdom

[edit]United States

[edit]

In the United States, the minimum wage is set by U.S. labor law and a range of state and local laws.[212] The first federal minimum wage was instituted in the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, but later found to be unconstitutional.[213] In 1938, the Fair Labor Standards Act established it at 25¢ an hour ($5.58 in 2024).[214] Its purchasing power peaked in 1968, at $1.60 ($14.47 in 2024).[214][215][216] In 2009, Congress increased it to $7.25 per hour with the Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2007.[217]

Employers have to pay workers the highest minimum wage of those prescribed by federal, state, and local laws. In August 2022, 30 states and the District of Columbia had minimum wages higher than the federal minimum.[218] As of July 2025, 22 states and the District of Columbia have minimum wages above the federal level, with Washington State ($16.66) and the District of Columbia ($17.95) the highest.[219] In 2019, only 1.6 million Americans earned no more than the federal minimum wage—about ~1% of workers, and less than ~2% of those paid by the hour. Less than half worked full time; almost half were aged 16–25; and more than 60% worked in the leisure and hospitality industries, where many workers received tips in addition to their hourly wages. No significant differences existed among ethnic or racial groups; women were about twice as likely as men to earn minimum wage or less.[220]

In January 2020, almost 90% of Americans earning the minimum wage were earning more than the federal minimum wage due to local minimum wages.[221] The effective nationwide minimum wage (the wage that the average minimum-wage worker earns) was $11.80 in May 2019; this was the highest it had been since at least 1994, the earliest year for which effective-minimum-wage data are available.[222]

In 2021, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that incrementally raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025 would impact 17 million employed persons but would also reduce employment by ~1.4 million people.[223][224] Additionally, 900,000 people might be lifted out of poverty and potentially raise wages for 10 million more workers. Furthermore, the increase would be expected to cause prices to rise and overall economic output to decrease slightly, and increase the federal budget deficit by $54 billion over the next 10 years.[223][224][225][b] An Ipsos survey in August 2020 found that support for a rise in the federal minimum wage had grown substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic, with 72% of Americans in favor, including 62% of Republicans and 87% of Democrats.[226] A March 2021 poll by Monmouth University Polling Institute, conducted as a minimum-wage increase was being considered in Congress, found 53% of respondents supporting an increase to $15 an hour and 45% opposed.[227]Minimum to median wage ratio

[edit]| Country | Minimum to median wage ratio in 2024[230] |

|---|---|

| 0.92 | |

| 0.87 | |

| 0.75 | |

| 0.74 | |

| 0.69 | |

| 0.62 | |

| 0.61 | |

| 0.61 | |

| 0.61 | |

| 0.59 | |

| 0.59 | |

| 0.57 | |

| 0.56 | |

| 0.54 | |

| 0.54 | |

| 0.53 | |

| 0.51 | |

| 0.51 | |

| 0.51 | |

| 0.50 | |

| 0.50 | |

| 0.50 | |

| 0.50 | |

| 0.50 | |

| 0.49 | |

| 0.49 | |

| 0.48 | |

| 0.47 | |

| 0.47 | |

| 0.46 | |

| 0.44 | |

| 0.42 | |

| 0.25 |

See also

[edit]- Average worker's wage

- Corporatism

- Cost of living

- Economic inequality

- Employee benefits

- Family wage

- Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority

- Labor law

- Living wage

- Minimum Wage Fixing Convention 1970

- Negative and positive rights

- List of countries by minimum wage

- Price controls

- Salary cap

- Scratch Beginnings

- Thomas Sowell

- Universal basic income

- Youth unemployment

- Walter E. Williams

- Working poor

Notes

[edit]- ^ notably take-away foods, canteen meals, hotel services and domestic services

- ^ See the section on Employment for more detailed findings from this study, including employment estimates on raising the wage to $10 or $12 per hour.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "ILO 2006: Minimum wages policy (PDF)" (PDF). Ilo.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Larsson, Anthony; Teigland, Robin (2020). The digital transformation of labor: Automation, the gig economy and welfare. Routledge, London: Routledge Studies in Labour Economics. doi:10.4324/9780429317866. hdl:10419/213906. ISBN 978-0-429-31786-6. S2CID 213586833. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Neumark, David (2019). "The Econometrics and Economics of the Employment Effects of Minimum Wages: Getting from Known Unknowns to Known Knowns". German Economic Review. 20 (3): e1 – e32. doi:10.1111/geer.12162. S2CID 55558316. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Real minimum wages from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development". OECD. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

- ^ "A brief history of the minimum wage in New Zealand". Newshub. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Dube, Arindrajit (1994). "Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania". American Economic Review. 84 (4): 772–793. JSTOR 2118030. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "$15 Minimum Wage". www.igmchicago.org. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas C. (2000). "The Very Idea of Apply Economics: The Modern Minimum-Wage Controversy and Its Antecedents". In Backhouse, Roger E.; Biddle, Jeff (eds.). Toward a History of Applied Economics. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 117–144. ISBN 978-0-8223-6485-6.

- ^ a b Gwartney, James David; Clark, J. R.; Stroup, Richard L. (1985). Essentials of Economics. New York: Harcourt College Pub; 2 edition. p. 405. ISBN 978-0123110350.

- ^ "Should We Raise The Minimum Wage?". The Perspective. 30 August 2017. Archived from the original on 25 July 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ a b "The Young and the Jobless". The Wall Street Journal. 3 October 2009. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Black, John (18 September 2003). Oxford Dictionary of Economics. Oxford University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-19-860767-0.

- ^ a b c Card, David; Krueger, Alan B. (1995). Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage. Princeton University Press. pp. 1, 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Mihm, Stephen (5 September 2013). "How the Black Death Spawned the Minimum Wage". Bloomberg View. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Wendy V. Cunningham (2007). Minimum wages and social policy: lessons from developing countries (PDF). The World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-7011-7. ISBN 978-0-8213-7011-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (29 March 2014). "Black death was not spread by rat fleas, say researchers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ a b Starr, Gerald (1993). Minimum wage fixing: an international review of practices and problems (2nd impression (with corrections) ed.). Geneva: International Labour Office. p. 1. ISBN 9789221025115.

- ^ Nordlund, Willis J. (1997). The quest for a living wage: the history of the federal minimum wage program. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. xv. ISBN 9780313264122.

- ^ a b c d Neumark, David; William L. Wascher (2008). Minimum Wages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-14102-4. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ^ Thomas C. Leonard, Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics & American Economics in the Progressive Era, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016): 158–167.

- ^ Tritch, Teresa (7 March 2014). "F.D.R. Makes the Case for the Minimum Wage". New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "Franklin Roosevelt's Statement on the National Industrial Recovery Act". Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum Our Documents. 16 June 1933. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Grossman, Jonathan (1978). "Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938: Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage". Monthly Labor Review. 101 (6). Department of Labor: 22–30. PMID 10307721. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Stone, Jon (1 October 2010). "History of the UK's minimum wage". Total Politics. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Williams, Walter E. (June 2009). "The Best Anti-Poverty Program We Have?". Regulation. 32 (2): 62.

- ^ a b "Minimum wage statistics – Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Ehrenberg, Ronald G. Labor Markets and Integrating National Economies, Brookings Institution Press (1994), p. 41

- ^ a b Alderman, Liz; Greenhouse, Steven (27 October 2014). "Fast Food in Denmark Serves Something Atypical: Living Wages". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ "Minimum Wage". Minimum Wage. Washington State Dept. of Labor & Industries. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "National Minimum Wage and National Living Wage rates". Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ "State Minimum Wage Laws". U.S. Department of Labor.

- ^ "Interview with Mr. Milind Ranade (Kachra Vahtuk Shramik Sangh Mumbai)". TISS Wastelines official website. Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ "Most Asked Questions about Minimum Wages in India". PayCheck.in. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Sowell, Thomas (2004). "Minimum Wage Laws". Basic Economics: A Citizen's Guide to the Economy. New York: Basic Books. pp. 163–69. ISBN 978-0-465-08145-5.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Provisional Minimum Wage Commission: Preliminary Views on a Bask of Indicators, Other Relevant Considerations and Impact Assessment" (PDF). Provisional Minimum Wage Commission, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Setting the Initial Statutory Minimum Wage Rate, submission to government by the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ Li, Joseph (16 October 2008). "Minimum wage legislation for all sectors". China Daily. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Card, David (1994). "Minimum Wages and Employment: A Case Study of the Fast-Food Industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania". The American Economic Review. 84 (4). American Economic Association: 772–793. JSTOR 2118030.

- ^ Neumark, David (2006). "Minimum Wages and Employment: A Review of Evidence from the New Minimum Wage Research". NBER Working Paper No. 12663. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w12663.

- ^ MaCurdy, Thomas (2015). "How Effective Is the Minimum Wage at Supporting the Poor?". Journal of Political Economy. 123 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 497–545. doi:10.1086/679626. S2CID 154665585.

- ^ Hotz, V. Joseph (2006). "Examining the Effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit on the Labor Market Participation of Families on Welfare". NBER Working Paper No. 11968. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w11968.

- ^ a b c Ehrenberg, R. and Smith, R. "Modern labor economics: theory and public policy", HarperCollins, 1994, 5th ed.[page needed]

- ^ McConnell, C. R.; Brue, S. L. (1999). Economics (14th ed.). Irwin-McGraw Hill. p. 594. ISBN 9780072898385.

- ^ Gwartney, J. D.; Stroup, R. L.; Sobel, R. S.; Macpherson, D. A. (2003). Economics: Private and Public Choice (10th ed.). Thomson South-Western. p. 97.

- ^ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2011). Principles of Macroeconomics (6th ed.). South-Western Pub. p. 311.