Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Genome

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism or cell.[1] It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as regulatory sequences (see non-coding DNA), and often a substantial fraction of junk DNA with no evident function.[2][3] Almost all eukaryotes have mitochondria and a small mitochondrial genome.[2] Algae and plants also contain chloroplasts with a chloroplast genome.

The study of the genome is called genomics. The genomes of many organisms have been sequenced and various regions have been annotated. The first genome to be sequenced was that of the virus φX174 in 1977;[4] the first genome sequence of a prokaryote (Haemophilus influenzae) was published in 1995;[5] the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) genome was the first eukaryotic genome to be sequenced in 1996.[6] The Human Genome Project was started in October 1990, and the first draft sequences of the human genome were reported in February 2001.[7]

Origin of the term

[edit]The term genome was created in 1920 by Hans Winkler,[8] professor of botany at the University of Hamburg, Germany. The website Oxford Dictionaries and the Online Etymology Dictionary suggest the name is a blend of the words gene and chromosome.[9][10][11][12] However, see omics for a more thorough discussion. A few related -ome words already existed, such as biome and rhizome, forming a vocabulary into which genome fits systematically.[13]

Definition

[edit]

The term "genome" usually refers to the DNA (or sometimes RNA) molecules that carry the genetic information in an organism, but sometimes it is uncertain which molecules to include; for example, bacteria usually have one or two large DNA molecules (chromosomes) that contain all of the essential genetic material but they also contain smaller extrachromosomal plasmid molecules that carry important genetic information. In the scientific literature, the term 'genome' usually refers to the large chromosomal DNA molecules in bacteria.[14]

Nuclear genome

[edit]Eukaryotic genomes are even more difficult to define because almost all eukaryotic species contain nuclear chromosomes plus extra DNA molecules in the mitochondria. In addition, algae and plants have chloroplast DNA. Most textbooks make a distinction between the nuclear genome and the organelle (mitochondria and chloroplast) genomes so when they speak of, say, the human genome, they are only referring to the genetic material in the nucleus.[2][15] This is the most common use of 'genome' in the scientific literature.

Ploidy

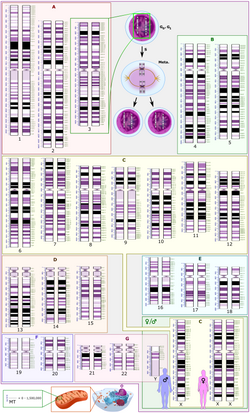

[edit]Most eukaryotes are diploid, meaning that there are two of each chromosome in the nucleus but the 'genome' refers to only one copy of each chromosome. Some eukaryotes have distinctive sex chromosomes, such as the X and Y chromosomes of mammals, so the technical definition of the genome must include both copies of the sex chromosomes. For example, the standard reference genome of humans consists of one copy of each of the 22 autosomes plus one X chromosome and one Y chromosome.[16]

Sequencing and mapping

[edit]A genome sequence is the complete list of the nucleotides (A, C, G, and T for DNA genomes) that make up all the chromosomes of an individual or a species. Within a species, the vast majority of nucleotides are identical between individuals, but sequencing multiple individuals is necessary to understand the genetic diversity.

In 1976, Walter Fiers at the University of Ghent (Belgium) was the first to establish the complete nucleotide sequence of a viral RNA-genome (Bacteriophage MS2). The next year, Fred Sanger completed the first DNA-genome sequence: Phage X174, of 5386 base pairs.[17] The first bacterial genome to be sequenced was that of Haemophilus influenzae, completed by a team at The Institute for Genomic Research in 1995. A few months later, the first eukaryotic genome was completed, with sequences of the 16 chromosomes of budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae published as the result of a European-led effort begun in the mid-1980s. The first genome sequence for an archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii, was completed in 1996, again by The Institute for Genomic Research.[18]

The development of new technologies has made genome sequencing dramatically cheaper and easier, and the number of complete genome sequences is growing rapidly. The US National Institutes of Health maintains one of several comprehensive databases of genomic information.[19] Among the thousands of completed genome sequencing projects include those for rice, a mouse, the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, the puffer fish, and the bacteria E. coli. In December 2013, scientists first sequenced the entire genome of a Neanderthal, an extinct species of humans. The genome was extracted from the toe bone of a 130,000-year-old Neanderthal found in a Siberian cave.[20][21]

Viral genomes

[edit]Viral genomes can be composed of either RNA or DNA. The genomes of RNA viruses can be either single-stranded RNA or double-stranded RNA, and may contain one or more separate RNA molecules (segments: monopartit or multipartit genome). DNA viruses can have either single-stranded or double-stranded genomes. Most DNA virus genomes are composed of a single, linear molecule of DNA, but some are made up of a circular DNA molecule.[22]

Prokaryotic genomes

[edit]Prokaryotes and eukaryotes have DNA genomes. Archaea and most bacteria have a single circular chromosome,[23] however, some bacterial species have linear or multiple chromosomes.[24][25] If the DNA is replicated faster than the bacterial cells divide, multiple copies of the chromosome can be present in a single cell, and if the cells divide faster than the DNA can be replicated, multiple replication of the chromosome is initiated before the division occurs, allowing daughter cells to inherit complete genomes and already partially replicated chromosomes. Most prokaryotes have very little repetitive DNA in their genomes.[26] However, some symbiotic bacteria (e.g. Serratia symbiotica) have reduced genomes and a high fraction of pseudogenes: only ~40% of their DNA encodes proteins.[27][28]

Some bacteria have auxiliary genetic material, also part of their genome, which is carried in plasmids. For this, the word genome should not be used as a synonym of chromosome.

Eukaryotic genomes

[edit]

Eukaryotic genomes are composed of one or more linear DNA chromosomes. The number of chromosomes varies widely from Jack jumper ants and an asexual nemotode,[29] which each have only one pair, to a fern species that has 720 pairs.[30] It is surprising the amount of DNA that eukaryotic genomes contain compared to other genomes. The amount is even more than what is necessary for DNA protein-coding and noncoding genes because eukaryotic genomes show as much as 64,000-fold variation in their sizes.[31] However, this special characteristic is caused by the presence of repetitive DNA, and transposable elements (TEs).

A typical human cell has two copies of each of 22 autosomes, one inherited from each parent, plus two sex chromosomes, making it diploid. Gametes, such as ova, sperm, spores, and pollen, are haploid, meaning they carry only one copy of each chromosome. In addition to the chromosomes in the nucleus, organelles such as the chloroplasts and mitochondria have their own DNA. Mitochondria are sometimes said to have their own genome often referred to as the "mitochondrial genome". The DNA found within the chloroplast may be referred to as the "plastome". Like the bacteria they originated from, mitochondria and chloroplasts have a circular chromosome.

Unlike prokaryotes where exon-intron organization of protein coding genes exists but is rather exceptional, eukaryotes generally have these features in their genes and their genomes contain variable amounts of repetitive DNA. In mammals and plants, the majority of the genome is composed of repetitive DNA.[32]

DNA sequencing

[edit]High-throughput technology makes sequencing to assemble new genomes accessible to everyone. Sequence polymorphisms are typically discovered by comparing resequenced isolates to a reference, whereas analyses of coverage depth and mapping topology can provide details regarding structural variations such as chromosomal translocations and segmental duplications.

Coding sequences

[edit]DNA sequences that carry the instructions to make proteins are referred to as coding sequences. The proportion of the genome occupied by coding sequences varies widely. A larger genome does not necessarily contain more genes, and the proportion of non-repetitive DNA decreases along with increasing genome size in complex eukaryotes.[32]

Noncoding sequences

[edit]Noncoding sequences include introns, sequences for non-coding RNAs, regulatory regions, and repetitive DNA. Noncoding sequences make up 98% of the human genome. There are two categories of repetitive DNA in the genome: tandem repeats and interspersed repeats.[33]

Tandem repeats

[edit]Short, non-coding sequences that are repeated head-to-tail are called tandem repeats. Microsatellites consisting of 2–5 basepair repeats, while minisatellite repeats are 30–35 bp. Tandem repeats make up about 4% of the human genome and 9% of the fruit fly genome.[34] Tandem repeats can be functional. For example, telomeres are composed of the tandem repeat TTAGGG in mammals, and they play an important role in protecting the ends of the chromosome.

In other cases, expansions in the number of tandem repeats in exons or introns can cause disease.[35] For example, the human gene huntingtin (Htt) typically contains 6–29 tandem repeats of the nucleotides CAG (encoding a polyglutamine tract). An expansion to over 36 repeats results in Huntington's disease, a neurodegenerative disease. Twenty human disorders are known to result from similar tandem repeat expansions in various genes. The mechanism by which proteins with expanded polygulatamine tracts cause death of neurons is not fully understood. One possibility is that the proteins fail to fold properly and avoid degradation, instead accumulating in aggregates that also sequester important transcription factors, thereby altering gene expression.[35]

Tandem repeats are usually caused by slippage during replication, unequal crossing-over and gene conversion.[36]

Transposable elements

[edit]Transposable elements (TEs) are sequences of DNA with a defined structure that are able to change their location in the genome.[34][26][37] TEs are categorized as either as a mechanism that replicates by copy-and-paste or as a mechanism that can be excised from the genome and inserted at a new location. In the human genome, there are three important classes of TEs that make up more than 45% of the human DNA; these classes are The long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), The interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), and endogenous retroviruses. These elements have a big potential to modify the genetic control in a host organism.[31]

The movement of TEs is a driving force of genome evolution in eukaryotes because their insertion can disrupt gene functions, homologous recombination between TEs can produce duplications, and TE can shuffle exons and regulatory sequences to new locations.[38]

Retrotransposons

[edit]Retrotransposons[39] are found mostly in eukaryotes but not found in prokaryotes. Retrotransposons form a large portion of the genomes of many eukaryotes. A retrotransposon is a transposable element that transposes through an RNA intermediate. Retrotransposons[40] are composed of DNA, but are transcribed into RNA for transposition, then the RNA transcript is copied back to DNA formation with the help of a specific enzyme called reverse transcriptase. A retrotransposon that carries reverse transcriptase in its sequence can trigger its own transposition but retrotransposons that lack a reverse transcriptase must use reverse transcriptase synthesized by another retrotransposon. Retrotransposons can be transcribed into RNA, which are then duplicated at another site into the genome.[41] Retrotransposons can be divided into long terminal repeats (LTRs) and non-long terminal repeats (Non-LTRs).[38]

Long terminal repeats (LTRs) are derived from ancient retroviral infections, so they encode proteins related to retroviral proteins including gag (structural proteins of the virus), pol (reverse transcriptase and integrase), pro (protease), and in some cases env (envelope) genes.[37] These genes are flanked by long repeats at both 5' and 3' ends. It has been reported that LTRs consist of the largest fraction in most plant genome and might account for the huge variation in genome size.[42]

Non-long terminal repeats (Non-LTRs) are classified as long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), and Penelope-like elements (PLEs). In Dictyostelium discoideum, there is another DIRS-like elements belong to Non-LTRs. Non-LTRs are widely spread in eukaryotic genomes.[43]

Long interspersed elements (LINEs) encode genes for reverse transcriptase and endonuclease, making them autonomous transposable elements. The human genome has around 500,000 LINEs, taking around 17% of the genome.[44]

Short interspersed elements (SINEs) are usually less than 500 base pairs and are non-autonomous, so they rely on the proteins encoded by LINEs for transposition.[45] The Alu element is the most common SINE found in primates. It is about 350 base pairs and occupies about 11% of the human genome with around 1,500,000 copies.[38]

DNA transposons

[edit]DNA transposons encode a transposase enzyme between inverted terminal repeats. When expressed, the transposase recognizes the terminal inverted repeats that flank the transposon and catalyzes its excision and reinsertion in a new site.[34] This cut-and-paste mechanism typically reinserts transposons near their original location (within 100 kb).[38] DNA transposons are found in bacteria and make up 3% of the human genome and 12% of the genome of the roundworm C. elegans.[38]

Genome size

[edit]

Genome size is the total number of the DNA base pairs in one copy of a haploid genome. Genome size varies widely across species. Invertebrates have small genomes, this is also correlated to a small number of transposable elements. Fish and Amphibians have intermediate-size genomes, and birds have relatively small genomes but it has been suggested that birds lost a substantial portion of their genomes during the phase of transition to flight. Before this loss, DNA methylation allows the adequate expansion of the genome.[31]

In humans, the nuclear genome comprises approximately 3.1 billion nucleotides of DNA, divided into 24 linear molecules, the shortest 45 000 000 nucleotides in length and the longest 248 000 000 nucleotides, each contained in a different chromosome.[46] There is no clear and consistent correlation between morphological complexity and genome size in either prokaryotes or lower eukaryotes.[32][47] Genome size is largely a function of the expansion and contraction of repetitive DNA elements.

Since genomes are very complex, one research strategy is to reduce the number of genes in a genome to the bare minimum and still have the organism in question survive. There is experimental work being done on minimal genomes for single cell organisms as well as minimal genomes for multi-cellular organisms (see developmental biology). The work is both in vivo and in silico.[48][49]

Genome size differences due to transposable elements

[edit]

There are many enormous differences in size in genomes, specially mentioned before in the multicellular eukaryotic genomes. Much of this is due to the differing abundances of transposable elements, which evolve by creating new copies of themselves in the chromosomes.[31] Eukaryote genomes often contain many thousands of copies of these elements, most of which have acquired mutations that make them defective.

Genomic alterations

[edit]All the cells of an organism originate from a single cell, so they are expected to have identical genomes; however, in some cases, differences arise. Both the process of copying DNA during cell division and exposure to environmental mutagens can result in mutations in somatic cells. In some cases, such mutations lead to cancer because they cause cells to divide more quickly and invade surrounding tissues.[50] In certain lymphocytes in the human immune system, V(D)J recombination generates different genomic sequences such that each cell produces a unique antibody or T cell receptors.

During meiosis, diploid cells divide twice to produce haploid germ cells. During this process, recombination results in a reshuffling of the genetic material from homologous chromosomes so each gamete has a unique genome.

Genome-wide reprogramming

[edit]Genome-wide reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells involves epigenetic imprint erasure leading to totipotency. Reprogramming is facilitated by active DNA demethylation, a process that entails the DNA base excision repair pathway.[51] This pathway is employed in the erasure of CpG methylation (5mC) in primordial germ cells. The erasure of 5mC occurs via its conversion to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) driven by high levels of the ten-eleven dioxygenase enzymes TET1 and TET2.[52]

Genome evolution

[edit]Genomes are more than the sum of an organism's genes and have traits that may be measured and studied without reference to the details of any particular genes and their products. Researchers compare traits such as karyotype (chromosome number), genome size, gene order, codon usage bias, and GC-content to determine what mechanisms could have produced the great variety of genomes that exist today (for recent overviews, see Brown 2002; Saccone and Pesole 2003; Benfey and Protopapas 2004; Gibson and Muse 2004; Reese 2004; Gregory 2005).

Duplications play a major role in shaping the genome. Duplication may range from extension of short tandem repeats, to duplication of a cluster of genes, and all the way to duplication of entire chromosomes or even entire genomes. Such duplications are probably fundamental to the creation of genetic novelty.

Horizontal gene transfer is invoked to explain how there is often an extreme similarity between small portions of the genomes of two organisms that are otherwise very distantly related. Horizontal gene transfer seems to be common among many microbes. Also, eukaryotic cells seem to have experienced a transfer of some genetic material from their chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes to their nuclear chromosomes. Recent empirical data suggest an important role of viruses and sub-viral RNA-networks to represent a main driving role to generate genetic novelty and natural genome editing.

In fiction

[edit]Works of science fiction illustrate concerns about the availability of genome sequences.

Michael Crichton's 1990 novel Jurassic Park and the subsequent film tell the story of a billionaire who creates a theme park of cloned dinosaurs on a remote island, with disastrous outcomes. A geneticist extracts dinosaur DNA from the blood of ancient mosquitoes and fills in the gaps with DNA from modern species to create several species of dinosaurs. A chaos theorist is asked to give his expert opinion on the safety of engineering an ecosystem with the dinosaurs, and he repeatedly warns that the outcomes of the project will be unpredictable and ultimately uncontrollable. These warnings about the perils of using genomic information are a major theme of the book.

The 1997 film Gattaca is set in a futurist society where genomes of children are engineered to contain the most ideal combination of their parents' traits, and metrics such as risk of heart disease and predicted life expectancy are documented for each person based on their genome. People conceived outside of the eugenics program, known as "In-Valids" suffer discrimination and are relegated to menial occupations. The protagonist of the film is an In-Valid who works to defy the supposed genetic odds and achieve his dream of working as a space navigator. The film warns against a future where genomic information fuels prejudice and extreme class differences between those who can and cannot afford genetically engineered children.[53]

See also

[edit]- Bacterial genome size

- Cryoconservation of animal genetic resources

- DNA methylation

- Genome Browser

- Genome Compiler

- Genome topology

- Genome-wide association study

- List of sequenced animal genomes

- List of sequenced archaeal genomes

- List of sequenced bacterial genomes

- List of sequenced eukaryotic genomes

- List of sequenced fungi genomes

- List of sequenced plant genomes

- List of sequenced plastomes

- List of sequenced protist genomes

- Metagenomics

- Microbiome

- Molecular epidemiology

- Molecular pathological epidemiology

- Molecular pathology

- Nucleic acid sequence

- Pan-genome

- Precision medicine

- Regulator gene

- Whole genome sequencing

References

[edit]- ^ Roth, Stephanie Clare (1 July 2019). "What is genomic medicine?". Journal of the Medical Library Association. 107 (3). University Library System, University of Pittsburgh: 442–448. doi:10.5195/jmla.2019.604. ISSN 1558-9439. PMC 6579593. PMID 31258451.

- ^ a b c Graur, Dan; Sater, Amy K.; Cooper, Tim F. (2016). Molecular and Genome Evolution. Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 9781605354699. OCLC 951474209.

- ^ Brosius, J (2009). "The Fragmented Gene". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1178 (1): 186–93. Bibcode:2009NYASA1178..186B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05004.x. PMID 19845638. S2CID 8279434.

- ^ Sanger F, Air GM, Barrell BG, Brown NL, Coulson AR, Fiddes CA, et al. (February 1977). "Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage phi X174 DNA". Nature. 265 (5596): 687–95. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..687S. doi:10.1038/265687a0. PMID 870828. S2CID 4206886.

- ^ Fleischmann RD, Adams MD, White O, Clayton RA, Kirkness EF, Kerlavage AR, et al. (July 1995). "Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd". Science. 269 (5223): 496–512. Bibcode:1995Sci...269..496F. doi:10.1126/science.7542800. PMID 7542800. S2CID 10423613.

- ^ Goffeau A, Barrell BG, Bussey H, Davis RW, Dujon B, Feldmann H, Galibert F, Hoheisel JD, Jacq C, Johnston M, Louis EJ, Mewes HW, Murakami Y, Philippsen P, Tettelin H, Oliver SG (1996). "Life with 6000 genes". Science. 274 (5287): 546, 563–67. Bibcode:1996Sci...274..546G. doi:10.1126/science.274.5287.546. PMID 8849441. S2CID 16763139.

- ^ Olson MV (2002). "The Human Genome Project: A Player's Perspective". Journal of Molecular Biology. 319 (4): 931–942. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00333-9. PMID 12079320.

- ^ Winkler HL (1920). Verbreitung und Ursache der Parthenogenesis im Pflanzen- und Tierreiche. Jena: Verlag Fischer.

- ^ "definition of Genome in Oxford dictionary". Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "genome". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "genome". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 24 August 2022.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "genome". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Lederberg J, McCray AT (2001). "'Ome Sweet 'Omics – A Genealogical Treasury of Words" (PDF). The Scientist. 15 (7).

- ^ Kirchberger PC, Schmidt ML, and Ochman H (2020). "The ingenuity of bacterial genomes". Annual Review of Microbiology. 74: 815–834. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115822. PMID 32692614. S2CID 220699395.

- ^ Brown, TA (2018). Genomes 4. New York, NY, USA: Garland Science. ISBN 9780815345084.

- ^ "Ensembl Human Assembly and gene annotation (GRCh38)". Ensembl. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "All about genes". beowulf.org.uk.

- ^ "TIGR Scientists Complete the First Genome Sequence of an Oral Pathogen Associated with Severe Adult Periodontal Disease". 12 June 2001.

- ^ "Genome Home". 8 December 2010. Archived from the original on 9 March 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ Zimmer C (18 December 2013). "Toe Fossil Provides Complete Neanderthal Genome". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Prüfer K, Racimo F, Patterson N, Jay F, Sankararaman S, Sawyer S, et al. (January 2014). "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–49. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235.

- ^ Gelderblom, Hans R. (1996). Structure and Classification of Viruses (4th ed.). Galveston, TX: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 9780963117212. PMID 21413309.

- ^ Samson RY, Bell SD (2014). "Archaeal chromosome biology". Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 24 (5–6): 420–27. doi:10.1159/000368854. PMC 5175462. PMID 25732343.

- ^ Chaconas G, Chen CW (2005). "Replication of Linear Bacterial Chromosomes: No Longer Going Around in Circles". The Bacterial Chromosome. pp. 525–540. doi:10.1128/9781555817640.ch29. ISBN 9781555812324.

- ^ "Bacterial Chromosomes". Microbial Genetics. 2002.

- ^ a b Koonin EV, Wolf YI (July 2010). "Constraints and plasticity in genome and molecular-phenome evolution". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 11 (7): 487–98. doi:10.1038/nrg2810. PMC 3273317. PMID 20548290.

- ^ McCutcheon JP, Moran NA (November 2011). "Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 10 (1): 13–26. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2670. PMID 22064560. S2CID 7175976.

- ^ Land M, Hauser L, Jun SR, Nookaew I, Leuze MR, Ahn TH, Karpinets T, Lund O, Kora G, Wassenaar T, Poudel S, Ussery DW (March 2015). "Insights from 20 years of bacterial genome sequencing". Functional & Integrative Genomics. 15 (2): 141–61. doi:10.1007/s10142-015-0433-4. PMC 4361730. PMID 25722247.

- ^ "Scientists sequence asexual tiny worm whose lineage stretches back 18 million years". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ Khandelwal S (March 1990). "Chromosome evolution in the genus Ophioglossum L.". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 102 (3): 205–17. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1990.tb01876.x.

- ^ a b c d Zhou, Wanding; Liang, Gangning; Molloy, Peter L.; Jones, Peter A. (11 August 2020). "DNA methylation enables transposable element-driven genome expansion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 117 (32): 19359–19366. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11719359Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921719117. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 7431005. PMID 32719115.

- ^ a b c Lewin B (2004). Genes VIII (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-143981-8.

- ^ Stojanovic N, ed. (2007). Computational genomics : current methods. Wymondham: Horizon Bioscience. ISBN 978-1-904933-30-4.

- ^ a b c Padeken J, Zeller P, Gasser SM (April 2015). "Repeat DNA in genome organization and stability". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 31: 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2015.03.009. PMID 25917896.

- ^ a b Usdin K (July 2008). "The biological effects of simple tandem repeats: lessons from the repeat expansion diseases". Genome Research. 18 (7): 1011–19. doi:10.1101/gr.070409.107. PMC 3960014. PMID 18593815.

- ^ Li YC, Korol AB, Fahima T, Beiles A, Nevo E (December 2002). "Microsatellites: genomic distribution, putative functions and mutational mechanisms: a review". Molecular Ecology. 11 (12): 2453–65. Bibcode:2002MolEc..11.2453L. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01643.x. PMID 12453231. S2CID 23606208.

- ^ a b Wessler SR (November 2006). "Transposable elements and the evolution of eukaryotic genomes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (47): 17600–01. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317600W. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607612103. PMC 1693792. PMID 17101965.

- ^ a b c d e Kazazian HH (March 2004). "Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution". Science. 303 (5664): 1626–32. Bibcode:2004Sci...303.1626K. doi:10.1126/science.1089670. PMID 15016989. S2CID 1956932.

- ^ "Transposon | genetics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Sanders, Mark Frederick (2019). Genetic Analysis: an integrated approach third edition. New York: Pearson, always learning, and mastering. p. 425. ISBN 9780134605173.

- ^ Deininger PL, Moran JV, Batzer MA, Kazazian HH (December 2003). "Mobile elements and mammalian genome evolution". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 13 (6): 651–58. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2003.10.013. PMID 14638329.

- ^ Kidwell MG, Lisch DR (March 2000). "Transposable elements and host genome evolution". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 15 (3): 95–99. Bibcode:2000TEcoE..15...95K. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01817-0. PMID 10675923.

- ^ Richard GF, Kerrest A, Dujon B (December 2008). "Comparative genomics and molecular dynamics of DNA repeats in eukaryotes". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 72 (4): 686–727. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00011-08. PMC 2593564. PMID 19052325.

- ^ Cordaux R, Batzer MA (October 2009). "The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 10 (10): 691–703. doi:10.1038/nrg2640. PMC 2884099. PMID 19763152.

- ^ Han JS, Boeke JD (August 2005). "LINE-1 retrotransposons: modulators of quantity and quality of mammalian gene expression?". BioEssays. 27 (8): 775–84. doi:10.1002/bies.20257. PMID 16015595. S2CID 26424042.

- ^ Nurk, Sergey; et al. (31 March 2022). "The complete sequence of a human genome" (PDF). Science. 376 (6588): 44–53. Bibcode:2022Sci...376...44N. doi:10.1126/science.abj6987. PMC 9186530. PMID 35357919. S2CID 235233625. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2022.

- ^ Gregory TR, Nicol JA, Tamm H, Kullman B, Kullman K, Leitch IJ, Murray BG, Kapraun DF, Greilhuber J, Bennett MD (January 2007). "Eukaryotic genome size databases". Nucleic Acids Research. 35 (Database issue): D332–38. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl828. PMC 1669731. PMID 17090588.

- ^ Glass JI, Assad-Garcia N, Alperovich N, Yooseph S, Lewis MR, Maruf M, Hutchison CA, Smith HO, Venter JC (January 2006). "Essential genes of a minimal bacterium". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (2): 425–30. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..425G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0510013103. PMC 1324956. PMID 16407165.

- ^ Forster AC, Church GM (2006). "Towards synthesis of a minimal cell". Molecular Systems Biology. 2 (1) 45. doi:10.1038/msb4100090. PMC 1681520. PMID 16924266.

- ^ Martincorena I, Campbell PJ (September 2015). "Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells". Science. 349 (6255): 1483–89. Bibcode:2015Sci...349.1483M. doi:10.1126/science.aab4082. PMID 26404825. S2CID 13945473.

- ^ Hajkova P, Jeffries SJ, Lee C, Miller N, Jackson SP, Surani MA (July 2010). "Genome-wide reprogramming in the mouse germ line entails the base excision repair pathway". Science. 329 (5987): 78–82. Bibcode:2010Sci...329...78H. doi:10.1126/science.1187945. PMC 3863715. PMID 20595612.

- ^ Hackett JA, Sengupta R, Zylicz JJ, Murakami K, Lee C, Down TA, Surani MA (January 2013). "Germline DNA demethylation dynamics and imprint erasure through 5-hydroxymethylcytosine". Science. 339 (6118): 448–52. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..448H. doi:10.1126/science.1229277. PMC 3847602. PMID 23223451.

- ^ "Gattaca (movie)". Rotten Tomatoes. 24 October 1997.

Further reading

[edit]- Benfey P, Protopapas AD (2004). Essentials of Genomics. Prentice Hall.

- Brown TA (2002). Genomes 2. Oxford: Bios Scientific Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85996-029-5.

- Gibson G, Muse SV (2004). A Primer of Genome Science (Second ed.). Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Assoc. ISBN 978-0-87893-234-4.

- Gregory TR (2005). The Evolution of the Genome. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-301463-4.

- Reece RJ (2004). Analysis of Genes and Genomes. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-84379-6.

- Saccone C, Pesole G (2003). Handbook of Comparative Genomics. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-39128-9.

- Werner E (December 2003). "In silico multicellular systems biology and minimal genomes". Drug Discovery Today. 8 (24): 1121–27. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02918-0. PMID 14678738.

External links

[edit]- UCSC Genome Browser – view the genome and annotations for more than 80 organisms.

- genomecenter.howard.edu (archived 9 August 2013)

- Build a DNA Molecule (archived 9 June 2010)

- Some comparative genome sizes

- DNA Interactive: The History of DNA Science

- DNA From The Beginning

- All About The Human Genome Project—from Genome.gov

- Animal genome size database

- Plant genome size database (archived 1 September 2005)

- GOLD:Genomes OnLine Database

- The Genome News Network

- NCBI Entrez Genome Project database

- NCBI Genome Primer

- GeneCards—an integrated database of human genes

- BBC News – Final genome 'chapter' published

- IMG (The Integrated Microbial Genomes system)—for genome analysis by the DOE-JGI

- GeKnome Technologies Next-Gen Sequencing Data Analysis—next-generation sequencing data analysis for Illumina and 454 Service from GeKnome Technologies (archived 3 March 2012)

Genome

View on GrokipediaHistory and Terminology

Origin of the Term

The term "genome" was coined in 1920 by German botanist Hans Winkler, professor of botany at the University of Hamburg, as a portmanteau blending the German words Gen (gene) and Chromosom (chromosome).[15][16] In his treatise Verbreitung und Ursache der Parthenogenesis im Pflanzen- und Tierreiche, Winkler introduced the concept to describe the fundamental units of heredity in the context of plant and animal reproduction.[17] Winkler defined the genome specifically as "the haploid number of chromosomes with the associated protoplasm," emphasizing its role as the material foundation of a species' essential characteristics, particularly in relation to phenomena like parthenogenesis and polyploidy.[18] This coinage emerged within early 20th-century botanical and cytological research, where it was used to analyze chromosome sets in plants, such as in studies of hybrid formation and reproductive abnormalities in species like hawkweeds (Hieracium) and dandelions (Taraxacum).[19] Initially confined to plant genetics, the term's usage expanded in the post-1940s era with the rise of molecular biology, shifting toward a more general designation for the complete hereditary apparatus across organisms.[20] This broader adoption occurred through applications in microbial and viral genetics. By the mid-20th century, "genome" had become integral to understanding the full complement of genetic material, paving the way for its modern interpretation as the entirety of an organism's DNA.[18]Definition and Scope

The genome is defined as the complete set of an organism's genetic material, which includes all of its genes and noncoding regions, serving as the blueprint for building and maintaining the organism. In most cellular life forms, this genetic material consists of DNA organized into chromosomes within the cell nucleus, though it also encompasses DNA in organelles. This comprehensive repository encodes the instructions necessary for development, functioning, reproduction, and response to the environment.[21][1] In organisms with sexual reproduction, genomes are distinguished by ploidy: the haploid genome represents a single complete set of chromosomes (typically found in gametes), while the diploid genome contains two such sets (as in most somatic cells of animals and plants). For eukaryotic organisms, the full genomic scope extends beyond the nuclear DNA to include the genomes of organelles, such as the mitochondrial genome in animals, plants, and fungi, and the chloroplast genome in plants and algae, which collectively contribute to cellular energy production and photosynthesis. These organelle genomes, though smaller and more conserved, are integral to the organism's total genetic complement.[21][22] Viral genomes differ markedly from those of cellular organisms, as viruses are acellular and their genetic material can be either DNA or RNA, existing in single-stranded or double-stranded forms, often enclosed in a protein coat rather than chromosomes. These compact genomes, ranging from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands of nucleotides, encode viral proteins essential for replication within host cells but lack the complexity of cellular genomes.[23][24]Fundamental Concepts

Ploidy Levels

Ploidy refers to the number of complete sets of chromosomes in the cells of an organism. A haploid (n) genome contains one set of chromosomes, typically found in gametes or certain unicellular organisms, while a diploid (2n) genome has two sets, one inherited from each parent, which is the standard in most multicellular animals and many plants. Polyploidy describes genomes with more than two sets (e.g., triploid 3n or tetraploid 4n), a condition prevalent in plants but rarer in animals. For instance, the human genome is diploid, comprising 46 chromosomes (23 pairs) in somatic cells.[25][26][27][28] Ploidy levels play crucial roles in reproduction, speciation, and disease. In sexual reproduction, meiosis reduces the diploid state to haploid gametes, ensuring that fertilization restores the diploid condition in offspring. Polyploidy can drive speciation by creating instant reproductive barriers, as polyploid individuals often cannot successfully mate with diploid progenitors due to chromosome mismatch during meiosis, leading to hybrid inviability or sterility. In disease contexts, deviations from balanced ploidy, such as aneuploidy (abnormal chromosome numbers), contribute to genomic instability and are a hallmark of cancer, where they promote tumor progression by altering gene dosage and cellular physiology.[29][30][31] Ploidy is measured using the C-value, which quantifies the amount of DNA in a haploid genome, typically in picograms (pg) or base pairs. The 1C-value specifically denotes the DNA content of a unreplicated haploid genome, providing a standardized metric for comparing genome sizes across species regardless of ploidy. This notation helps distinguish DNA content from chromosome number, as polyploid cells contain multiple copies of the haploid set.[32] Polyploidy offers evolutionary advantages in plants, including increased genetic redundancy that buffers against deleterious mutations, enhanced vigor through gene dosage effects, and greater adaptability to environmental stresses like drought or cold. These benefits have contributed to the diversification of angiosperms, with estimates indicating that 30-80% of species have undergone polyploidy events in their evolutionary history, either recently or ancestrally. Such duplications enable subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization of genes, fostering novel traits and ecological niches.[33][34][35]Nuclear Genome

The nuclear genome constitutes the primary repository of genetic information in eukaryotic cells, housed within a membrane-bound nucleus and organized into multiple linear chromosomes. This organization distinguishes it from the circular DNA typical of prokaryotic and mitochondrial genomes, enabling complex regulation and packaging to accommodate large sizes. In diploid eukaryotes, such as humans, the nuclear genome comprises two homologous sets of chromosomes inherited from each parent, influencing the total genetic content through ploidy levels.[36] Structurally, each nuclear chromosome consists of a single, long DNA double helix tightly associated with histone proteins to form chromatin, the fundamental unit of DNA packaging. Histones organize DNA into nucleosomes—bead-like structures where approximately 147 base pairs of DNA wrap around an octamer of histone proteins—allowing further compaction into higher-order chromatin fibers, loops, and domains that fit within the nucleus while permitting access for replication and transcription. Essential functional elements include centromeres, specialized regions that serve as attachment sites for spindle fibers during mitosis and meiosis to ensure accurate chromosome segregation; telomeres, repetitive DNA sequences at chromosome ends that protect against enzymatic degradation and fusion; and multiple origins of replication distributed along each chromosome, typically spaced every 30,000 to 300,000 base pairs, to facilitate the timely duplication of the extensive DNA during the cell cycle. In humans, for instance, up to 100,000 origins may operate across the genome to replicate the ~6 billion base pairs present in a diploid cell.[37][38] Genes within the nuclear genome are organized as discrete units interspersed with non-gene sequences, featuring coding regions (exons) interrupted by non-coding introns that are spliced out during mRNA processing, alongside regulatory elements such as promoters, enhancers, and silencers that modulate gene expression in response to cellular signals. This modular arrangement allows for alternative splicing and fine-tuned regulation, contributing to the diversity of proteins from a limited gene set. Gene density varies across chromosomes but is generally low, with human chromosomes averaging one gene per million base pairs. The human nuclear genome, fully sequenced by the Telomere-to-Telomere Consortium in 2022, spans approximately 3.05 billion base pairs in its haploid form and encodes around 20,000 protein-coding genes, a figure refined from initial Human Genome Project estimates through improved annotation and gap-filling.[14][39] In contrast to the compact, circular mitochondrial genome—which encodes only 37 genes and is maternally inherited—the nuclear genome is vastly larger, biparentally inherited, and integrates most cellular functions, including those supporting organelle operation. This separation underscores the endosymbiotic origins of mitochondria while highlighting the nucleus as the central hub for eukaryotic genetic complexity.[40]Genomes Across Organisms

Viral Genomes

Viral genomes exhibit remarkable diversity in structure, composition, and size, distinguishing them from the cellular genomes of prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Unlike prokaryotic genomes, which are typically double-stranded DNA organized within cells, viral genomes can consist of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), single-stranded RNA (ssRNA), or double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), and they lack the cellular machinery for independent replication.[41] This nucleic acid core encodes the viral proteins necessary for infection and propagation, with genome sizes ranging from approximately 3.6 kb in the ssRNA bacteriophage MS2 to over 2.4 Mb in certain giant dsDNA viruses of the Mimiviridae family, such as those identified in soil metagenomes.[42][43] For instance, the mimivirus, a well-studied giant virus, possesses a dsDNA genome of about 1.2 Mb, encoding over 1,000 genes that blur the line between viral and cellular complexity.[44] Replication strategies among viruses vary significantly, often tailored to their genome type and host interaction. Retroviruses, such as HIV, employ an integration strategy where their ssRNA genome is reverse-transcribed into dsDNA and incorporated into the host cell's genome via the viral integrase enzyme, allowing latent persistence and propagation during host cell division.[45] In contrast, many dsDNA viruses and some RNA viruses follow independent lytic cycles, hijacking host resources to produce viral components and lyse the cell to release progeny virions, as seen in bacteriophages.[46] All viruses depend entirely on host cellular machinery for transcription and translation, lacking ribosomes, polymerases, and other organelles; for example, ssRNA viruses use host ribosomes to translate their genomic RNA directly into proteins upon entry.[47] Certain viruses, like influenza A, feature segmented genomes—eight separate ssRNA segments in this case—each encoding specific proteins, which facilitates genetic reassortment and rapid adaptation during co-infections.[48] The evolutionary dynamics of viral genomes are driven by exceptionally high mutation rates, particularly in RNA viruses, which lack proofreading mechanisms during replication. This results in error rates of about 10^{-4} to 10^{-5} substitutions per site per replication cycle, far exceeding those of DNA-based organisms, fostering immense genetic diversity.[49] Such variability has propelled viral evolution, enabling emergence of pandemics; the SARS-CoV-2 genome, an ssRNA molecule of approximately 30 kb, has accumulated mutations that influence transmissibility and immune evasion since its identification in 2019.[50][51] These traits underscore viruses' role as key drivers of genetic innovation across the tree of life.Prokaryotic Genomes

Prokaryotic genomes, found in bacteria and archaea, are typically compact and organized as a single circular chromosome housed in the nucleoid region of the cell. This structure contrasts with the linear chromosomes of eukaryotes and enables efficient replication and transcription without the need for telomeres or centromeres. For instance, the genome of Escherichia coli, a model bacterium, consists of a 4.6 megabase pair (Mb) circular chromosome containing approximately 4,400 genes.[4][52] Gene regulation in prokaryotes often occurs through operons, clusters of functionally related genes that are transcribed together as a single polycistronic mRNA, allowing coordinated expression in response to environmental cues. This organization facilitates rapid adaptation, such as in the lac operon of E. coli, which regulates lactose metabolism. Prokaryotic genomes also feature high gene density, with 85–90% of the DNA typically coding for proteins, and a general absence of introns, meaning pre-mRNA processing is unnecessary. Transcription initiation relies on sigma factors, dissociable subunits of RNA polymerase that recognize promoter sequences and direct the enzyme to specific genes.[53][54][55][56] Accessory genetic elements like plasmids, which are extrachromosomal circular DNA molecules, play a crucial role in horizontal gene transfer, enabling the spread of traits such as antibiotic resistance across bacterial populations. Genome sizes vary widely, from about 0.58 Mb in Mycoplasma genitalium to the expansive 14.8 Mb of Sorangium cellulosum, the largest sequenced bacterial genome, reflecting diverse metabolic and ecological demands. These genomes are significantly smaller than those of eukaryotes, underscoring their streamlined architecture.[57][58][59] Prokaryotes exhibit adaptive features like CRISPR arrays, which function as an acquired immune system against viruses and plasmids by storing short sequences from invaders and using them to guide Cas proteins for targeted DNA cleavage. In synthetic biology, efforts to define essential genes have produced minimal genomes, such as JCVI-syn3.0, a 0.53 Mb synthetic Mycoplasma mycoides genome with only 473 genes, created in 2016 to support self-replication while stripping non-essential elements.[60][61]Eukaryotic Genomes

Eukaryotic genomes encompass the nuclear genome along with the genomes of endosymbiotic organelles, mitochondria and chloroplasts, reflecting the compartmentalized nature of eukaryotic cells. The nuclear genome, housed in the nucleus, varies widely in size across species; for instance, the unicellular yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has a compact nuclear genome of approximately 12 megabases (Mb), while the multicellular human nuclear genome spans about 3.2 gigabases (Gb).[62][63] Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a small, circular molecule typically around 16 kilobases (kb) in humans, encoding essential genes for oxidative phosphorylation.[64] In plants, chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) is larger, averaging about 150 kb, and contains genes for photosynthesis and other plastid functions.[65] This holistic composition integrates nuclear control with organelle-specific genetic elements derived from ancient bacterial symbionts. The increased complexity of eukaryotic genomes compared to prokaryotes stems from adaptations to multicellularity and intricate developmental regulation, which demand sophisticated gene networks for cell differentiation and tissue organization. In unicellular eukaryotes like yeast, the genome supports basic metabolic and replicative functions in a single-celled context, whereas in multicellular organisms like humans, the larger genome accommodates regulatory elements for spatiotemporal gene expression across diverse cell types. Whole-genome duplications (WGDs) have further amplified this complexity; vertebrates experienced two rounds of WGD early in their evolution (the 2R hypothesis), providing genetic redundancy that facilitated the diversification of developmental pathways.[66] Similarly, plants have undergone multiple WGD events, contributing to their morphological and physiological innovations, such as seed production and vascular systems.[67] Organelle genomes exhibit distinct inheritance and evolutionary origins that underscore their endosymbiotic history. Mitochondrial DNA is maternally inherited in humans and most animals, with paternal mtDNA typically degraded shortly after fertilization to ensure uniparental transmission.[68] Both mtDNA and cpDNA trace their origins to endosymbiotic events: mitochondria from alphaproteobacteria and chloroplasts from cyanobacteria, events that occurred over a billion years ago and integrated prokaryotic genomes into the eukaryotic framework.[69] These organelle genomes remain compact and maternally inherited in plants for cpDNA, maintaining a legacy of their bacterial ancestry while functioning under nuclear oversight.Structure and Composition

Coding Sequences

Coding sequences, also known as coding DNA, refer to the segments of the genome that encode functional gene products, including proteins and various non-protein-coding RNAs. For protein-coding genes, these sequences are organized as open reading frames (ORFs), which are continuous stretches of DNA from a start codon (typically ATG) to a stop codon (TAA, TAG, or TGA), translated into polypeptides by ribosomes.[70] Non-protein-coding genes produce essential RNAs such as ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which forms the core of ribosomes; transfer RNA (tRNA), which delivers amino acids during translation; and microRNA (miRNA), which regulates gene expression post-transcriptionally.[71][72] In the human genome, protein-coding sequences account for only about 1-2% of the total DNA, despite encoding approximately 19,000–20,000 genes.[73][74][75] Pseudogenes, which are inactivated copies of functional genes, represent non-functional relics within this landscape, numbering around 20,000 in humans and often arising from gene duplication events followed by mutations that disrupt their coding potential.[76][77] The structure of coding sequences varies between eukaryotes and prokaryotes. In eukaryotes, protein-coding genes are typically interrupted by non-coding introns, with the coding portions residing in exons that are joined during mRNA splicing to form mature transcripts.[6] In contrast, prokaryotic genes lack introns and feature continuous coding sequences, frequently arranged in operons that generate polycistronic mRNAs encoding multiple proteins from a single transcript.[78][79] Coding sequences exhibit functional diversity, with genes classified as housekeeping or tissue-specific based on expression patterns. Housekeeping genes, such as those encoding actin or GAPDH, are constitutively expressed across all cell types to maintain basic cellular functions.[80] Tissue-specific genes, however, are predominantly active in particular organs or cell types, enabling specialized functions like hemoglobin production in erythrocytes. Alternative splicing further enhances this diversity in eukaryotes, allowing a single gene to generate multiple mRNA isoforms—and thus protein variants—through selective inclusion or exclusion of exons, which can alter protein function, localization, or stability.[81][82]Noncoding Sequences

Noncoding sequences, also known as noncoding DNA, encompass the portions of the genome that do not directly encode proteins but are essential for gene regulation, chromatin organization, and genome stability. These sequences include regulatory elements, repetitive regions, and transcripts that modulate cellular processes. In eukaryotes, noncoding DNA often exceeds coding regions in abundance, influencing transcription, RNA processing, and epigenetic modifications. Regulatory noncoding elements include introns, which are intervening sequences within genes that are transcribed but spliced out during mRNA maturation, thereby facilitating alternative splicing and gene expression fine-tuning. Promoters, located upstream of transcription start sites, serve as binding platforms for RNA polymerase and transcription factors to initiate gene expression. Enhancers and silencers act as distal regulatory elements that boost or repress transcription, respectively, by looping interactions with promoters to modulate chromatin accessibility. Untranslated regions (UTRs), comprising 5' and 3' segments flanking coding exons, regulate mRNA stability, localization, and translation efficiency through interactions with RNA-binding proteins and microRNAs.[83][84][85] Tandem repeats consist of short DNA motifs arranged in head-to-tail arrays and are classified into satellite DNA, which forms large blocks at centromeres and telomeres to support chromosome segregation, and microsatellites (short tandem repeats of 1-6 base pairs). Satellite DNA, such as alpha-satellites, is critical for kinetochore assembly and centromere function, ensuring proper mitosis. Microsatellites, however, can expand pathologically; for instance, trinucleotide CAG repeats in the HTT gene expand beyond 36 units in Huntington's disease, leading to toxic protein aggregates and neurodegeneration via altered DNA repair mechanisms.[86][87][88] Transposable elements (TEs), mobile DNA segments that can relocate within the genome, comprise approximately 45% of the human genome and include long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), and retrotransposons. LINEs, such as L1 elements, are autonomous retrotransposons that encode proteins for their own retrotransposition and constitute about 17-20% of the human genome, often inserting into new sites to disrupt genes or create regulatory variants. SINEs, like Alu elements, are non-autonomous and rely on LINE machinery, making up around 11-13% of the genome while influencing splicing and transcription. These elements drive genome evolution by promoting insertions, duplications, and exon shuffling, which can generate genetic diversity and novel functions over time.[89][90][91] Functional noncoding sequences also produce long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that do not code for proteins but regulate epigenetics through chromatin remodeling and gene silencing. LncRNAs act as scaffolds or guides for histone-modifying complexes, such as PRC2, to deposit repressive marks like H3K27me3, influencing X-chromosome inactivation (e.g., via XIST lncRNA) and developmental gene control. They contribute to epigenetic memory and cellular differentiation by modulating DNA methylation and enhancer activity.[92][93]Genome Size Variation

Genome size, often measured as the C-value (the amount of DNA in a haploid genome), exhibits vast variation across organisms, spanning several orders of magnitude without a clear correlation to organismal complexity—a phenomenon known as the C-value paradox. For instance, the fork fern Tmesipteris oblanceolata possesses a genome of approximately 160 gigabase pairs (Gb), far exceeding the 3.2 Gb human genome, despite the latter's greater complexity.[94] Similarly, the pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes) has a compact genome of about 0.4 Gb, which is gene-rich relative to its size, while the Australian lungfish (Neoceratodus forsteri) boasts a massive 43 Gb genome.[95] This paradox challenges the expectation that more complex organisms would require proportionally larger genomes to encode additional functions.[96] Key drivers of genome size variation include the proliferation of transposable elements (TEs), which can constitute up to 85% of large plant genomes, contributing to expansions without adding coding capacity.[97] Polyploidy, the multiplication of entire chromosome sets, also significantly increases genome size, as seen in many plants where whole-genome duplications lead to doubled or higher DNA content, influencing traits like cell size and organ development. These mechanisms explain much of the observed variation, particularly in eukaryotes, where neutral accumulation of non-essential DNA plays a central role.[96] C-values are commonly measured using flow cytometry, a technique that quantifies nuclear DNA content by staining and analyzing isolated nuclei, providing rapid and accurate estimates for diverse species.[98] This method has been instrumental in cataloging genome sizes, revealing patterns such as the compact genomes of certain fish versus the bloated ones in amphibians and protists.[98] Beyond TEs and polyploidy, other factors like expanded introns and duplicated genomic regions contribute to size differences, though to a lesser extent.[97] Recent studies in the 2020s have revised views on so-called "junk DNA," demonstrating that much noncoding sequence, once dismissed as functionless, influences gene regulation and disease susceptibility through repetitive elements.[99] These findings underscore how genome size variation reflects a balance of proliferative and selective forces rather than direct ties to phenotypic complexity.[96]Analysis and Techniques

Sequencing Methods

Genome sequencing methods encompass a range of technologies designed to determine the precise order of nucleotides in DNA, evolving from labor-intensive techniques to high-throughput platforms that enable large-scale genomic analysis.[100] The foundational method, Sanger sequencing, was developed by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in 1977, relying on chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides to generate DNA fragments of varying lengths, which are then separated by electrophoresis to read the sequence.[101] This approach achieved high accuracy, with error rates below 0.1%, and became the gold standard for over three decades.[102] It played a pivotal role in the Human Genome Project, where automated capillary electrophoresis variants were used to sequence approximately 92% of the human genome by 2003, at a total cost exceeding $2.7 billion.[100] In the 2000s, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies emerged, revolutionizing throughput and reducing costs. Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis platform, based on reversible terminator chemistry and acquired from Solexa in 2007, produces short reads (typically 100-300 base pairs) with error rates under 0.1%, enabling massive parallelization on flow cells.[103] This method dominated the field, facilitating projects like the 1000 Genomes Project by generating billions of reads per run.[103] The 2010s and 2020s introduced long-read sequencing to address limitations of short reads, such as challenges in resolving repetitive regions and structural variants (SVs). Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) launched single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing in 2010, using zero-mode waveguides to monitor phospholinked fluorescent nucleotides in real time, yielding reads up to 20 kilobases with raw error rates of 10-15%, improved to over 99.9% accuracy via circular consensus sequencing (HiFi reads).[104] Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) released its first device in 2014, employing protein nanopores to detect ionic current changes as DNA translocates, producing ultra-long reads exceeding 100 kilobases, though with higher raw error rates of 5-15%, mitigated by consensus polishing.[105] These long-read methods excel at detecting SVs, such as insertions, deletions, and inversions larger than 50 base pairs, which short-read approaches often miss due to alignment ambiguities in complex genomic regions.[106] Genome sequencing typically begins with library preparation, where DNA is fragmented, end-repaired, and ligated with adapters to enable amplification and sequencing compatibility; for example, Illumina's DNA Prep kit supports flexible input amounts from 10 ng to 1 μg.[107] Sequencing generates raw reads, which are then assembled either de novo—constructing contigs from scratch using overlap-layout-consensus algorithms when no reference is available—or reference-based, aligning reads to a known genome via tools like BWA or minimap2 for variant calling.[108] Coverage depth, the average number of reads spanning each base, is critical for accuracy; human genomes typically require 30x coverage to achieve >99% sensitivity for single-nucleotide variants, balancing cost and reliability.[109] By 2025, advances in single-molecule real-time sequencing, particularly PacBio's HiFi mode, have enhanced resolution of repetitive sequences like segmental duplications, enabling near-complete assemblies of challenging regions such as centromeres.[110] Concurrently, sequencing costs have plummeted, with platforms like Ultima Genomics' UG 100 achieving whole-human-genome sequencing below $100, driven by innovations in wafer-scale parallelization and reduced reagent use.[111]Genome Mapping

Genome mapping involves determining the precise locations of genes, regulatory elements, and other sequence features within a genome, providing a framework for understanding its organization and function. This process is essential for assembling genomes, identifying genetic variants, and studying evolutionary relationships. Mapping techniques vary in resolution and approach, ranging from indirect inference based on inheritance patterns to direct visualization or computational alignment of DNA sequences. Early methods laid the groundwork for modern genomics, while recent advances have addressed longstanding limitations in complex genomes. Genetic mapping, also known as linkage mapping, relies on analyzing recombination frequencies between genetic markers during meiosis to estimate relative positions on chromosomes. Markers such as restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are tracked across generations in pedigrees or mapping populations, with distances measured in centimorgans (cM), where 1 cM corresponds to a 1% recombination rate. This method provides a low-resolution overview, typically at the scale of megabases, but is invaluable for initial gene ordering and quantitative trait locus (QTL) detection. A seminal application was the construction of a comprehensive human genetic linkage map in 1992, incorporating 1,416 loci including genes and expressed sequences, which advanced positional cloning efforts.[112] Physical mapping techniques directly measure nucleotide distances between features, offering higher resolution than genetic mapping. Restriction mapping involves digesting DNA with enzymes that cut at specific sequences, then sizing and ordering the resulting fragments via gel electrophoresis or pulsed-field gel analysis to construct overlapping clone maps. For example, yeast artificial chromosomes (YACs) were used to create large-insert libraries for this purpose. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) complements this by hybridizing fluorescently labeled probes to metaphase chromosomes or interphase nuclei, allowing visualization of specific loci under a microscope with resolutions down to 50-100 kilobases. A key milestone was the physical mapping of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome in the early 1990s, where overlapping cosmid and YAC clones covered all 16 chromosomes by 1995, enabling the first eukaryotic genome sequence in 1996.[113][114] Sequence-based mapping emerged with the advent of high-throughput sequencing, using alignment algorithms to position reads or contigs relative to a reference genome. Tools like BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) identify homologous regions by comparing query sequences against databases, facilitating gene annotation and assembly validation through alignments that reveal syntenic blocks or insertions/deletions. This approach integrates short-read data from sequencing projects to refine maps at the base-pair level. In the human genome project, genetic maps achieved a resolution of less than 1 Mb (approximately 1 cM average spacing) by the mid-1990s, with over 8,000 markers integrated into frameworks that guided physical contig assembly.[115] Comparative mapping extends these techniques across species by aligning genetic or physical maps using shared markers, revealing conserved synteny and chromosomal rearrangements. For instance, alignments between human and mouse genomes have identified over 500 syntenic blocks, aiding in the transfer of functional annotations and evolutionary inference. This tool is particularly useful in non-model organisms where de novo mapping is challenging. Additionally, genome mapping integrates with sequencing data to assemble contigs—overlapping sequence fragments—into scaffolds, using mapping information to order and orient them into chromosome-level structures.[116][113] Despite these advances, challenges persist, particularly from repetitive DNA sequences like transposons and segmental duplications, which cause misalignments and assembly gaps in mapping efforts. Such regions, comprising over 50% of the human genome, often collapse or expand erroneously in maps, leading to incomplete or inaccurate representations. In the 2020s, improvements via Hi-C (high-throughput chromosome conformation capture) have addressed these issues by capturing long-range chromatin interactions, providing spatial proximity data that scaffolds contigs across repeats with resolutions down to 1 kilobase. Protocols like Hi-C 3.0 have enhanced signal-to-noise ratios and applicability to diverse species, significantly reducing gaps in complex assemblies.[117][118]Dynamics and Change

Genomic Alterations

Genomic alterations refer to changes in the DNA sequence or structure that can occur within an organism's genome, leading to variations in gene function, expression, or inheritance. These alterations encompass a range of scales, from single nucleotide changes to large-scale chromosomal rearrangements, and can arise spontaneously or due to external factors. They play critical roles in both normal biological processes, such as development and adaptation, and in disease pathogenesis, including cancer and genetic disorders. Understanding these alterations is essential for distinguishing between germline changes, which are heritable and present in all cells, and somatic changes, which occur in specific tissues and are not passed to offspring. The primary types of genomic alterations include point mutations, which involve the substitution of a single nucleotide base; insertions and deletions (indels), which add or remove segments of DNA; inversions, where a segment of a chromosome is reversed end-to-end; and translocations, which exchange genetic material between non-homologous chromosomes. Additionally, copy number variations (CNVs) represent duplications or deletions of larger DNA segments, typically ranging from 1 kilobase to several megabases, altering the dosage of genes in the affected regions. These structural variants collectively account for a significant portion of genomic diversity and can disrupt gene regulation or protein coding.[119][120] Mechanisms driving genomic alterations often stem from errors during DNA replication, where DNA polymerase may incorporate incorrect bases or fail to repair mismatches, leading to point mutations or indels at a rate of approximately 10^{-9} to 10^{-10} per base pair per replication in humans. Environmental mutagens, such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation, induce specific lesions like thymine dimers that, if unrepaired, cause distortions in the DNA helix and subsequent mutations during replication. Other mutagens, including certain chemicals, can alkylate DNA bases, promoting base mispairing. These processes are counteracted by DNA repair pathways, but failures can result in permanent alterations.[121][122] Representative examples illustrate the impact of these alterations. In sickle cell anemia, a point mutation in the beta-globin gene (HBB) on chromosome 11 substitutes adenine for thymine, changing glutamic acid to valine at position 6 of the protein, which causes hemoglobin polymerization and red blood cell sickling. This single nucleotide variant (SNV) demonstrates how a subtle change can lead to a severe monogenic disorder. In leukemia, chromosomal translocations exemplify larger rearrangements; for instance, the t(9;22) translocation in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) creates the Philadelphia chromosome, fusing BCR and ABL1 genes to produce an oncogenic tyrosine kinase. This alteration drives uncontrolled cell proliferation in approximately 95% of CML cases.[123][124] Detection of genomic alterations has advanced significantly with whole-genome sequencing (WGS), which enables comprehensive identification of both somatic and germline variants by comparing tumor or affected tissue DNA to matched normal samples, achieving sensitivity for SNVs down to 5% variant allele frequency. WGS distinguishes somatic mutations, acquired post-zygotically, from germline ones inherited from parents, aiding in personalized medicine. For epigenomic modifications, such as DNA methylation alterations that affect gene expression without changing the sequence, bisulfite sequencing converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while preserving methylated ones, allowing high-resolution mapping in the 2020s through techniques like whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS). These methods have revealed dynamic methylation patterns in diseases like cancer.[125][126]Genome Evolution

Genome evolution encompasses the long-term changes in genetic material driven by natural selection, genetic drift, and neutral processes, resulting in the diversification of species over evolutionary timescales. These changes arise from the accumulation of genomic alterations, which provide the raw material for macroevolutionary trends. Central to this process is the neutral theory of molecular evolution, proposed by Motoo Kimura, which argues that the majority of fixed nucleotide substitutions are selectively neutral and governed by random genetic drift rather than adaptive selection. This theory explains the observed regularity in molecular evolutionary rates across lineages, independent of phenotypic adaptations. Key mechanisms driving genome evolution include gene duplication, horizontal gene transfer, and exon shuffling. Gene duplication creates redundant copies that can diverge, allowing one to acquire novel functions while preserving the original, a process pivotal in expanding gene families and fostering innovation, as detailed in Susumu Ohno's seminal work.[127] In prokaryotes, horizontal gene transfer enables the acquisition of genetic material across species boundaries via mechanisms like conjugation, transduction, and transformation, accelerating adaptive evolution in dynamic environments.[128] Exon shuffling, through recombination events such as illegitimate recombination or transposon-mediated exonization, assembles new multidomain proteins from modular exons, contributing significantly to proteome complexity in eukaryotes.[129] Evidence for genome evolution is prominently derived from comparative genomics, which reveals patterns like conserved synteny—the preservation of gene order and chromosomal segments across species—particularly evident in mammalian lineages where large blocks of ancestral chromosomes remain intact, reflecting slow rates of rearrangement post-speciation.[130] Mutation rates provide quantitative insight into evolutionary tempo; in humans, the germline mutation rate is approximately per nucleotide site per generation, leading to about 50-100 new mutations per diploid genome.[131] Evolutionary bursts, such as those triggered by endosymbiosis, introduce rapid genomic restructuring; the incorporation of an alphaproteobacterial endosymbiont as the mitochondrial ancestor exemplifies how such events profoundly alter cellular energetics and genome organization, spurring eukaryotic diversification.[132] Recent advances in phylogenomics, leveraging whole-genome sequencing and large-scale datasets as of 2025, have resolved contentious deep branches in the tree of life, such as the positioning of phoronids within lophophorates, by integrating thousands of orthologous genes to overcome issues like incomplete lineage sorting.[133] Furthermore, noncoding sequences play a crucial role in adaptation, with regulatory elements evolving under selection to fine-tune gene expression; contrasts between coding and noncoding changes highlight how the latter often drive species-specific traits through cis-regulatory evolution.Applications and Impacts

Synthetic Genomes

Synthetic genomes refer to artificially constructed genetic sequences designed and assembled in laboratories to function within living cells, enabling the creation of novel organisms with specified traits. A landmark achievement occurred in 2010 when researchers at the J. Craig Venter Institute synthesized the 1.08-megabase genome of Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn1.0, which was transplanted into a recipient cell to produce a self-replicating bacterium controlled entirely by the synthetic DNA. This demonstrated the feasibility of de novo genome synthesis from chemical building blocks, marking the first instance of a fully synthetic bacterial cell. Building on this, in 2016, the same team developed JCVI-syn3.0, a minimal synthetic genome with 531 kilobase pairs and 473 genes, representing the smallest known genome capable of sustaining independent life and providing insights into essential genetic requirements.[134][135][136] Key techniques for constructing synthetic genomes include Gibson assembly, an isothermal method that joins multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction using exonuclease, polymerase, and ligase activities, allowing scarless assembly of large constructs without restriction enzymes. This approach was instrumental in assembling the JCVI-syn1.0 genome from overlapping oligonucleotides. Complementing this, CRISPR-based editing enables precise modifications during de novo synthesis, facilitating the integration of synthetic elements into host genomes for iterative refinement. In the 2020s, progress has extended to eukaryotic systems, including the completion of the Sc2.0 project in January 2025, which produced the world's first fully synthetic eukaryotic genome in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, comprising 12 redesigned chromosomes and enabling advanced biotechnological applications such as improved biofuel production.[137] Additionally, synthetic mammalian chromosomes—such as human artificial chromosomes (HACs)—serve as stable vectors for large-scale gene delivery and expression in mammalian cells, advancing toward full synthetic mammalian genomes.[138][134][139][140] Applications of synthetic genomes span bioengineering, where engineered microbes with redesigned genomes produce therapeutics; for instance, recombinant bacteria modified via synthetic DNA principles have enabled large-scale insulin manufacturing since the late 1970s, with modern synthetic approaches enhancing yield and safety. In xenobiology, synthetic genomes incorporate non-natural components, such as alternative genetic codes, to create orthogonal life forms incompatible with natural ecosystems, promoting biosafety in biotechnology. However, these advancements raise ethical concerns, including the potential misuse of synthetic elements in gene drives—CRISPR-enabled systems that bias inheritance to spread modifications rapidly through populations—prompting debates on ecological risks, equitable access, and governance frameworks to prevent unintended environmental impacts.[141][142][143] Recent advances include genome recoding efforts, exemplified in 2025 by the creation of Syn57, a strain of Escherichia coli with a synthetic 4-megabase genome using only 57 codons after replacing occurrences of six sense codons and one stop codon with synonyms, while maintaining viability and demonstrating the robustness of compressed genetic codes for expanded synthetic biology applications.[144]Genomes in Fiction