Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

German wine

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2023) |

German wine is primarily produced in the west of Germany, along the river Rhine and its tributaries, with the oldest plantations going back to the Celts[1] and Roman eras. Approximately 60 percent of German wine is produced in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, where 6 of the 13 regions (Anbaugebiete) for quality wine are situated. Germany has about 104,000 hectares (252,000 acres or 1,030 square kilometers) of vineyard, which is around one tenth of the vineyard surface in Spain, France or Italy.[2] The total wine production is usually around 10 million hectoliters annually, corresponding to 1.3 billion bottles, which places Germany as the ninth-largest wine-producing country and seventh by export market share in the world. White wine accounts for almost two thirds of the total production.

As a wine country, Germany has a mixed reputation internationally, with some consumers on the export markets associating Germany with the world's most elegant and aromatically pure white wines while other see the country mainly as the source of cheap, mass-market semi-sweet wines such as Liebfraumilch.[3] Among enthusiasts, Germany's reputation is primarily based on wines made from the Riesling grape variety, which at its best is used for aromatic, fruity and elegant white wines that range from very crisp and dry to well-balanced, sweet and of enormous aromatic concentration. While primarily a white wine country, red wine production surged in the 1990s and early 2000s, primarily fuelled by domestic demand, and the proportion of the German vineyards devoted to the cultivation of dark-skinned grape varieties has now stabilized at slightly more than a third of the total surface. For the red wines, Spätburgunder, the domestic name for Pinot noir, is in the lead.

Wine styles

[edit]Germany produces wines in many styles:[4] dry, semi-sweet and sweet white wines, rosé wines, red wines and sparkling wines, called Sekt. (The only wine style not commonly produced is fortified wine.) Due to the northerly location of the German vineyards, the country has produced wines quite unlike any others in Europe, many of outstanding quality. Between the 1950s and the 1980s German wine was known abroad for cheap, sweet or semi-sweet, low-quality mass-produced wines such as Liebfraumilch.

The wines have historically been predominantly white, and the finest made from Riesling. Many wines have been sweet and low in alcohol, light and unoaked. Historically many of the wines (other than late harvest wines) were probably dry (trocken), as techniques to stop fermentation did not exist. Recently much more German white wine is being made in the dry style again. Much of the wine sold in Germany is dry, especially in restaurants. However most exports are still of sweet wines, particularly to the traditional export markets such as the United States, the Netherlands and Great Britain, which are the leading export markets both in terms of volume and value.[2]

Red wine has always been hard to produce in the German climate, and in the past was usually light-colored, closer to rosé or the red wines of Alsace. However recently there has been greatly increased demand and darker, richer red wines (often barrique-aged) are produced from grapes such as Dornfelder and Spätburgunder, the German name for Pinot noir.[5]

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of German wines is the high level of acidity in them, caused both by the lesser ripeness in a northerly climate and by the selection of grapes such as Riesling, which retain acidity even at high ripeness levels.

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]Viticulture in present-day Germany dates back to Ancient Roman times, to sometime from 70 to 270 CE/AD (Agri Decumates). In those days, the western parts of today's Germany made up the outpost of the Roman empire against the Germanic tribes on the other side of Rhine. What is generally considered Germany's oldest city, Trier, was founded as a Roman garrison and is situated directly on the river Moselle (Mosel) in the eponymous wine region. The oldest archeological finds that may indicate early German viticulture are curved pruning knives found in the vicinity of Roman garrisons, dating from the 1st century AD.[6] However, it is not absolutely certain that these knives were used for viticultural purposes. Emperor Probus, whose reign can be dated two centuries later than these knives, is generally considered the founder of German viticulture, but for solid documentation of winemaking on German soil, we must go to around 370 AD, when Ausonius of Bordeaux wrote Mosella, where he in enthusiastic terms described the steep vineyards on the river Moselle.[6]

The wild vine, the forerunner of the cultivated Vitis vinifera is known to have grown on upper Rhine back to historic time, and it is possible (but not documented) that Roman-era German viticulture was started using local varieties. Many viticultural practices were however taken from other parts of the Roman empire, as evidenced by Roman-style trellising systems surviving into the 18th century in some parts of Germany, such as the Kammertbau in the Palatinate.[6]

Almost nothing is known of the style or quality of "German" wines that were produced in the Roman era, with the exception of the fact that the poet Venantius Fortunatus mentions red German wine around AD 570.

From Medieval times to today

[edit]Before the era of Charlemagne, Germanic viticulture was practiced primarily, although not exclusively, on the western side of Rhine. Charlemagne is supposed to have brought viticulture to Rheingau. The eastward spread of viticulture coincided with the spread of Christianity, which was supported by Charlemagne. Thus, in Medieval Germany, churches and monasteries played the most important role in viticulture, and especially in the production of quality wine. Two Rheingau examples illustrate this: archbishop Ruthard of Mainz (reigning 1089–1109) founded a Benedictine abbey on slopes above Geisenheim, the ground of which later became Schloss Johannisberg. His successor Adalbert of Mainz donated land above Hattenheim in 1135 to Cistercians, sent out from Clairvaux in Champagne, who founded Kloster Eberbach.[6]

Many grape varieties commonly associated with German wines have been documented back to the 14th or 15th century. Riesling has been documented from 1435 (close to Rheingau), and Pinot noir from 1318 on Lake Constance under the name Klebroth, from 1335 in Affenthal in Baden and from 1470 in Rheingau, where the monks kept a Clebroit-Wyngart in Hattenheim.[7][8] The most grown variety in medieval Germany was however Elbling, with Silvaner also being common, and Muscat, Räuschling and Traminer also being recorded.[6]

For several centuries of the Medieval era, the vineyards of Germany (including Alsace) expanded, and is believed to have reached their greatest extent sometime around 1500, when perhaps as much as four times the present vineyard surface was planted. Basically, the wine regions were located in the same places as today, but more lands around the rivers, and land further upstream Rhine's tributaries, was cultivated. The subsequent decline can be attributed to locally produced beer becoming the everyday beverage in northern Germany in the 16th century, leading to a partial loss of market for wine, to the Thirty Years' War ravaging Germany in the 17th century, to the dissolution of the monasteries, where much of the winemaking know-how was concentrated, in those areas that accepted the Protestant reformation, and to the climatic changes of the Little Ice Age that made viticulture difficult or impossible in marginal areas.[6]

An important event took place in 1775 at Schloss Johannisberg in Rheingau, when the courier delivering the harvest permission was delayed for two weeks, with the result that most of the grapes in Johannisberg's Riesling-only vineyard had been affected by noble rot before the harvest began. Unexpectedly, these "rotten grapes" gave a very good sweet wine, which was termed Spätlese, meaning late harvest. From this time, late harvest wines from grapes affected by noble rot have been produced intentionally. The subsequent differentiation of wines based on harvested ripeness, starting with Auslese in 1787, laid the ground for the Prädikat system. These laws, introduced in 1971, define the designations still used today.

At one point the Church controlled most of the major vineyards in Germany. Quality instead of quantity become important and spread quickly down the river Rhine. In the 1800s, Napoleon took control of all the vineyards from the Church, including the best, and divided and secularized them. In 1801, all German states west of the Rhine river were incorporated into the French state. This included the wine regions Ahr, Mosel, Nahe, Rheinhessen, and Pfalz, i.e., the vast majority of German wine production. Since then the Napoleonic inheritance laws in Germany broke up the parcels of vineyards further, leading to the establishment of many cooperatives. However, many notable and world-famous wineries in Germany have managed to acquire or hold enough land to produce wine not only for domestic consumption, but also export. After the battle of Waterloo and Napoleon’s final defeat, the Rhineland (which encompasses the viticultural regions Mosel, Mittelrhein, Nahe and Ahr) fell to Prussia, while the Palatinate (Pfalz) fell to Bavaria. Hesse Darmstadt received what is today known as Rheinhessen. Many of the best vineyards were transferred to the new states, where they were wrapped up as state domains.

Custom-free access to the vast Prussian markets in the east and the growing industrial clusters on the Ruhr and protection from non-Prussian competitors, including from southern German regions such Baden, Württemberg, Palatinate and Rheinhessen, fostered Mosel, Rhine, Nahe and Ahr winemakers, due to high tariff barriers for all other producers.

Geography and climate

[edit]The German wine regions are some of the most northerly in the world.[9] The main wine-producing climate lies below the 50th parallel, which runs through the regions Rheingau and Mosel. Above this line the climate becomes less conducive to wine production, but there are still some vineyards above this line and the effects of climate change on wine production are growing.

Because of the northerly climate, there has been a search for suitable grape varieties (particularly frost resistant and early harvesting ones), and many crosses have been developed, such as Müller-Thurgau in the Geisenheim Grape Breeding Institute. Since several years ago[when?] there has been an increase in plantings of Riesling as local and international demand has been demanding high quality wines.

The wines are all produced around rivers, mainly the Rhine and its tributaries, often sheltered by mountains. The rivers have significant microclimate effects to moderate the temperature. The soil is slate in the steep valleys, to absorb the sun's heat and retain it overnight. On the rolling hills the soil is lime and clay dominated. The great sites are often extremely steep so they catch the most sunlight, but they are difficult to harvest mechanically. The slopes are also positioned facing the south or south-west to angle towards the sun.

The vineyards are extremely small compared to New World vineyards and wine making is dominated by craft rather than industry wines. This makes the lists of wines produced long and complex, and many wines hard to obtain as production is so limited.

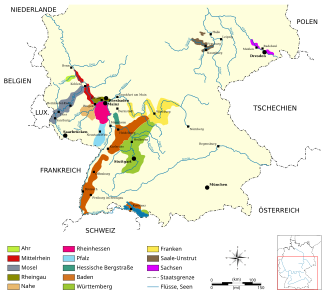

Regions

[edit]

The wine regions in Germany usually referred to are the 13 defined regions for quality wine. The German wine industry has organised itself around these regions and their division into districts. However, there are also a number of regions for the insignificant table wine (Tafelwein) and country wine (Landwein) categories. Those regions with a few exceptions overlap with the quality wine regions. To make a clear distinction between the quality levels, the regions and subregions for different quality levels have different names on purpose, even when they are allowed to be produced in the same geographical area.

German wine regions

[edit]There are 13 defined regions ("Anbaugebiete") in Germany:[5][10]

- Ahr – a small region along the river Ahr, a tributary of Rhine, that despite its northernly location primarily produces red wine from Spätburgunder.

- Baden – Germany's southernmost, warmest and sunniest winegrowing region, in Germany's southwestern corner, across river Rhine from Alsace, and the only German wine region situated in European Union wine growing zone B rather than A, which results in higher minimum required maturity of grapes and less chaptalisation allowed.[11] Most of the land is cultivated with Pinot family. That include Pinot Noir (Spätburgunder), Pinot Gris (Grauburgunder) and Pinot Blanc (Weissburgunder).[12]

- Franconia or Franken – around portions of Main river, and the only wine region situated in Bavaria. Noted for growing many varieties on chalky soil and for producing powerful dry Silvaner wines. In Germany, only Franconia and certain small parts of the Baden region are allowed to use the distinctive flattened Bocksbeutel bottle shape.

- Hessische Bergstraße (Hessian Mountain Road) – a small region in the state Hesse dominated by Riesling.

- Mittelrhein – along the middle portions of river Rhine, primarily between the regions Rheingau and Mosel, and dominated by Riesling.

- Mosel – along the river Moselle (Mosel) and its tributaries, the rivers Saar and Ruwer, and was previously known as Mosel-Saar-Ruwer. The Mosel region is dominated by Riesling grapes and slate soils, and the best wines are grown in dramatic-looking steep vineyards directly overlooking the rivers. This region produces wine that is light in body due to lower alcohol levels, crisp, of high acidity and with pronounced mineral character. The only region to stick to Riesling wine with noticeable residual sweetness as the "standard" style, although dry wines are also produced.

- Nahe – around the river Nahe where volcanic origins give very varied soils. Mixed grape varieties but the best-known producers primarily grow Riesling, and some of them have achieved world reputation in recent years.

- Palatinate or Pfalz – the second largest producing region in Germany, with production of very varied styles of wine (especially in the southern half), where red wine has been on the increase. The northern half of the region is home to many well-known Riesling producers with a long history, which specialize in powerful Riesling wines in a dry style. Until 1995, it was known in German as Rheinpfalz.[13]

- Rheingau – a small region at a bend in the Rhine that provide excellent conditions for winegrowing. The oldest documented references to Riesling come from the Rheingau region[14] and it is the region where many German winemaking practices have originated, such as the use of Prädikat designations. Dominated by Riesling with some Spätburgunder. The Rheingau Riesling style is in-between Mosel and the Palatinate and other southern regions, and at its finest combines the best aspects of both.

- Rheinhessen or Rhenish Hesse – the largest production area in Germany. Once known as Liebfraumilch land, but a quality revolution has taken place since the 1990s. Mixed wine styles and both red and white wines. The best Riesling wines are similar to Palatinate Riesling – dry and powerful. Despite its name, it lies in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, not in Hesse.

- Saale-Unstrut – one of two regions in former East Germany along the rivers Saale and Unstrut, and Germany's northernmost winegrowing region.

- Saxony or Sachsen – one of two regions in former East Germany, in the southeastern corner of the country, along the river Elbe in the state of Saxony.

- Württemberg – a traditional red wine region, where grape varieties Trollinger (the region's signature variety), Schwarzriesling and Lemberger outnumber the varieties that dominate elsewhere. One of two wine regions in the state of Baden-Württemberg.

These 13 regions (Anbaugebiete) are broken down into 39 districts (Bereiche) which are further broken down into collective vineyard sites (Großlagen) of which there are 167. The individual vineyard sites (Einzellagen) number 2,658.

Sorted by size

[edit]Data from 2023.[2]

| Region | Vineyard area (ha) | % White | % Red | Districts | Collective sites | Individual sites | Most grown varieties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheinhessen | 27499 | 74 | 26 | 3 | 24 | 442 | Riesling (19.6%), Müller-Thurgau (13.9%), Dornfelder (11.0%), Pinot gris (8.8%), Silvaner (6.8%), Pinot blanc (6.0%), Pinot Noir (5.5%), Chardonnay (4.0%), Portugieser 3.2%), Scheurebe (2.7%) |

| Palatinate | 23793 | 68 | 32 | 2 | 25 | 330 | Riesling (25.2%), Dornfelder (10.3%), Pinot gris (9.4%), Pinot noir (7.3%), Müller-Thurgau (6.7%), Pinot blanc (6.3%), Portugieser (4.4%), Chardonnay (4.1%), Sauvignon blanc (3.3%) |

| Baden | 15727 | 62 | 38 | 9 | 15 | 315 | Pinot noir (32.1%), Pinot gris (15.3%), Müller-Thurgau (13.8%), Pinot blanc (10.6%), Gutedel (6.5%), Riesling (5.6)% |

| Württemberg | 11392 | 36 | 64 | 6 | 20 | 207 | Riesling (62.4%), Trollinger (8.7%), Lemberger (5.2%), Pinot noir (5.1%), Pinot Meunier (4.4%) |

| Mosel | 8536 | 91 | 9 | 6 | 20 | 507 | Riesling (62.4%), Müller-Thurgau (9.0%), Elbling (5.0%), Pinot noir (5.0%), Pinot blanc (4.4%) |

| Franconia | 6173 | 83 | 17 | 3 | 22 | 211 | Silvaner (25.3%), Müller-Thurgau (22.3%), Bacchus (11.9%), Riesling (5.5%), Domina (4.8%), Pinot noir (4.5%) |

| Nahe | 4249 | 77 | 23 | 1 | 7 | 312 | Riesling (29.3%), Müller-Thurgau (11.0%); Pinot gis (9.3%), Dornfelder (8.9%), Pinot blanc (7.8%), Pinot noir (7.0%) |

| Rheingau | 3207 | 85 | 15 | 1 | 11 | 120 | Riesling (76.1%), Pinot noir (12.6%), Pinot blanc (2.1%); Pinot gis (1.1%) |

| Saale-Unstrut | 853 | 77 | 23 | 2 | 4 | 20 | Müller-Thurgau (14.3%), Pinot blanc (13.7%), Riesling (9.4%), Dornfelder (6.4%), Bacchus (6.4%) |

| Ahr | 531 | 21 | 79 | 1 | 1 | 43 | Pinot noir (64.7%), Riesling (8.2%), Pinot Noir Précoce (5.8%), Pinot blanc (4.1%), Regent (2.8%) |

| Saxony | 522 | 81 | 19 | 2 | 4 | 16 | Riesling (14.2%), Müller-Thurgau (11.4%), Pinot blanc (11.5%), Pinot gris (9.2%) |

| Mittelrhein | 460 | 84 | 16 | 2 | 11 | 111 | Riesling (63.3%), Pinot noir (10.7%), Pinot blanc (5.2%) |

| Hessische Bergstraße | 461 | 79 | 21 | 2 | 3 | 24 | Riesling (35.6%), Pinot gris (12.8%), Pinot noir (10.8%), Pinot blanc (5.6%) |

Tafelwein and Landwein regions

[edit]There are seven regions for Tafelwein (Weinbaugebiete für Tafelwein), three of which are divided into two or three subregions (Untergebiete) each, and 21 regions for Landwein (Landweingebiete).[15] These regions have the following relationship to each other, and to the quality wine regions:[16]

| Tafelwein region | Tafelwein subregion | Landwein region | Corresponding quality wine region | Number on map |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhein-Mosel | Rhein | Ahrtaler Landwein | Ahr | 1 |

| Rheinburgen-Landwein | Mittelrhein | 5 | ||

| Rheingauer Landwein | Rheingau | 9 | ||

| Nahegauer Landwein | Nahe | 7 | ||

| Rheinischer Landwein | Rheinhessen | 10 | ||

| Pfälzer Landwein | Palatinate | 8 | ||

| Starkenburger Landwein | Hessische Bergstraße | 4 | ||

| Moseltal | Landwein der Mosel | Mosel | 6 | |

| Landwein der Saar | ||||

| Saarländischer Landwein | ||||

| Landwein der Ruwer | ||||

| Bayern | Main | Landwein Main | Franconia | 3 |

| Donau | Regensburger Landwein | |||

| Lindau | Bayerischer Bodensee-Landwein | Württemberg | 13 | |

| Neckar | – | Schwäbischer Landwein | ||

| Oberrhein | Römertor | Badischer Landwein | Baden | 2 |

| Burgengau | Taubertäler Landwein | |||

| Albrechtsburg | – | Sächsischer Landwein | Saxony | 12 |

| Saale-Unstrut | Mitteldeutscher Landwein | Saale-Unstrut | 11 | |

| Niederlausitz | – | Brandenburger Landwein | In the state of Brandenburg, outside the quality wine regions | |

| Stargarder Land | – | Mecklenburger Landwein | In the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, outside the quality wine regions |

Grape varieties

[edit]Overall nearly 135 grape varieties may be cultivated in Germany – 100 are released for white wine production and 35 for red wine production. According to the international image, Germany is still considered a region for white wine production. Since the 1980s, demand for German red wine has constantly increased, and this has resulted in a doubling of the vineyards used for red wine. Nowadays, over 35% of the vineyards are cultivated with red grapes. Some of the red grapes are also used to produce rosé.

Out of all the grape varieties listed below, only 20 have a significant market share.

| Most common grape varieties in Germany (2022 situation, all varieties >1%)[17] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variety | Color | Synonym(s) | Area (%) | Area (hectares) | Trend | Major regions (with large plantations or high proportion) |

| 1. Riesling | white | 23.6 | 24 410 | increasing | Mosel, Palatinate, Rheingau, Rheinhessen, Nahe, Mittelrhein, Hessische Bergstraße | |

| 2. Müller-Thurgau | white | Rivaner | 10.6 | 10 970 | decreasing | Rheinhessen, Baden, Franconia, Mosel, Saale-Unstrut, Sachsen |

| 3. Spätburgunder | red | Pinot noir | 11.1 | 11 512 | constant | Baden, Palatinate, Rheinhessen, Württemberg, Rheingau, Ahr |

| 4. Grauburgunder | white | Pinot gris, Grauer Burgunder Ruländer | 7.8 | 8 094 | increasing | Rheinhessen, Palatinate, Mosel |

| 5. Dornfelder | red | 6.6 | 6 812 | decreasing | Rheinhessen, Palatinate, Nahe | |

| 6. Weißburgunder | white | Pinot blanc, Weißer Burgunder, Klevner | 6.0 | 6 181 | increasing | - bgcolor="FFA07A" |

| 7. Silvaner | white | Grüner Silvaner | 4.3 | 4 419 | decreasing | Rheinhessen, Franconia, Saale-Unstrut, Ahr |

| 8. Chardonnay | white | 2.6 | 2 731 | increasing | ||

| 9. Blauer Portugieser | red | 2.2 | 2 295 | decreasing | Palatinate, Rheinhessen, Ahr | |

| 10. Kerner | white | 2.0 | 2 032 | decreasing | Rheinhessen, Palatinate, Mosel, Württemberg | |

| 11. Trollinger | red | 1.9 | 1 940 | constant | Württemberg | |

| 12. Lemberger | red | Blaufränkisch | 1.9 | 1 929 | increasing | Württemberg |

| 13. Sauvignon blanc | white | 1.9 | 1 923 | increasing | ||

| 14. Schwarzriesling | red | Müllerrebe, Pinot Meunier | 1.6 | 1 698 | decreasing | Württemberg |

| 15. Regent | red | 1.6 | 1 618 | constant | ||

| 16. Bacchus | white | 1.5 | 1 558 | decreasing | Franconia | |

| 17. Scheurebe | white | 1.4 | 1 483 | increasing | Rheinhessen | |

| 18. Traminer | white | Gewürztraminer | 1.1 | 1 120 | increasing | |

| 19. Gutedel | white | Chasselas | 1.0 | 1 065 | constant | Baden |

| Grand total | 100.0 | 103 391 | constant | |||

Grape variety trends over time

[edit]

During the last century several changes have taken place with respect to the most planted varieties. Until the early 20th century, Elbling was Germany's most planted variety, after which it was eclipsed by Silvaner during the middle of the 20th century.[20] After a few decades in the top spot, in the late 1960s Silvaner was overtaken by the high-yielding Müller-Thurgau, which in turn started to lose ground in the 1980s. From the mid-1990s, Riesling became the most planted variety, a position it probably had never enjoyed before on a national level. Red grapes in Germany have experienced several ups and downs. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, there was a downward trend, which was reversed around 1980. From mid-1990s and during the next decade, there was an almost explosive growth of plantation of red varieties. Plantings was shared between traditional Spätburgunder and a number of new crossings, led by Dornfelder, while other traditional German red varieties such as Portugieser only held their ground. From around 2005, the proportion of red varieties has stabilized around 37%, about three times the 1980 level.

Common white wine grapes

[edit]White grape varieties account for 66% of the area planted in Germany. Principal varieties are listed below; there are larger numbers of less important varieties too.

- Riesling is the benchmark grape in Germany and covers the most area in German vineyards. It is an aromatic variety with a high level of acidity that can be used for dry, semi-sweet, sweet and sparkling wines. The drawback to Riesling is that it takes 130 days to ripen and, in marginal years, the Riesling crop tends to be poor.

- Müller-Thurgau is an alternative grape to Riesling that growers have been using, and is one of the so-called new crossings. Unlike the long ripening time of Riesling, this grape variety only requires 100 days to ripen, can be planted on more sites, and is higher yielding. However, this grape has a more neutral flavour than Riesling, and as the main ingredient of Liebfraumilch its reputation has taken a beating together with that wine variety. Germany's most planted variety from the 1970s to the mid-1990s, it has been losing ground for a number of years. Dry Müller-Thurgau is usually labeled Rivaner.

- Grauer Burgunder or Ruländer (Pinot gris)

- Weisser Burgunder (Pinot blanc)

- Silvaner is another subtle, fairly neutral, but quite old grape variety that was Germany's most planted until the 1960s and after that has continued to lose ground. It has however remained popular in Franconia and Rheinhessen, where it is grown on chalky soils to produce powerful dry wines with a slightly earthy and rustic but also food-friendly character.[21]

- Chardonnay

- Kerner

- Sauvignon blanc

- Bacchus

- Scheurebe

Common red wine grapes

[edit]Red wine varieties account for 34% of the plantations in Germany but has increased in recent years.

- Spätburgunder (Pinot noir) – a much-appreciated grape variety that demands good sites to produce good wines and therefore competes with Riesling. It is considered to give the most elegant red wines of Germany.

- Dornfelder – a "new crossing" that has become much appreciated in Germany since it is easy to grow and gives dark-coloured, full-bodied, fruity and tannic wines of a style that used to be hard to produce in Germany.

- Portugieser

- Trollinger

- Lemberger (Blaufränkisch)

- Schwarzriesling (Pinot Meunier)

- Regent

- Merlot

- St. Laurent

Permitted varieties

[edit]According to the German wine law, the state governments are responsible for drawing up lists of grape varieties allowed in wine production. The varieties listed below are officially permitted for commercial cultivation.[22] The lists include varieties permitted only for selected experimental cultivation.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Viticultural practices

[edit]

Many of the best vineyards in Germany are steep vineyards overlooking rivers, where mechanisation is impossible and a lot of manual labour is needed to produce the wine.

Since it can be difficult to get ripe grapes in such a northernly location as Germany, the sugar maturity of grapes (must weight) as measured by the Oechsle scale have played a great role in Germany.

German vintners on average crop their vineyards quite high, with yields averaging around 64–99 hl/ha,[17] a high figure in international comparison. Some crossings used for low-quality white wine yield up to 150–200 hl/ha, while quality-conscious producers who strive to produce well-balanced wines of concentrated flavours rarely exceed 50 hl/ha.

Many wines in Germany are produced using organic farming or biodynamic methods. With an average annual growth rate of 25 percent and a cultivated area of more than 7,000 hectares, Germany ranks in place six worldwide. The market share of organic wine is between four and five percent.[23]

Winemaking practices

[edit]Chaptalization is allowed only up to the QbA level, not for Prädikatswein and all wines must be fermented dry if chaptalised. To balance the wine, unfermented grape juice, called Süssreserve, may be added after fermentation.

Classification

[edit]

German wine classification is sometimes the source of confusion. However, to those familiar with the terms used, a German wine label reveals much information about the wine's origin, the minimum ripeness of the grapes used for the wine, as well as the dryness/sweetness of the wine.

In general, the ripeness classifications of German wines reflect minimum sugar content in the grape (also known as "potential alcohol" = the amount of alcohol resulting from fermenting all sugar in the juice) at the point of harvest of the grape. They have nothing to do with the sweetness of the wine after fermentation, which is one of the most common mis-perceptions about German wines.

- Deutscher Tafelwein (German table wine) is mostly consumed in the country and not exported. Generally used for blended wines that can not be Qualitätswein.

- Deutscher Landwein (German country wine) comes from a larger designation and again doesn't play an important role in the export market.

- Qualitätswein bestimmter Anbaugebiete (QbA) wines from a defined appellation with the exception of Liebfraumilch, which can be blended from several regions and still be classified as Qualitätswein.

- Prädikatswein, recently (August 1, 2007) renamed from Qualitätswein mit Prädikat (QmP) wines made from grapes of higher ripeness. As ripeness increases, the fruit characteristics and price increase. Categories within Prädikatswein are Kabinett, Spätlese, Auslese, Beerenauslese, Trockenbeerenauslese and Eiswein. Wines of these categories can not be chaptalized. All these categories within Prädikatswein are solely linked to minimum requirements of potential alcohol. While these may correlate with harvest time, there are no legally defined harvest time restrictions anymore.

- Kabinett wines are made from grapes that have achieved minimum defined potential alcohol levels. Those minimum requirements differ by region and grape variety. Essentially, Kabinett is the first level of reserve grape selection.

- Spätlese wines ("late harvest") are made from grapes that have achieved minimum defined potential alcohol levels. Those minimum requirements differ by region and grape variety. Essentially, Spatlese is the second level of reserve grape selection.

- Auslese ("select harvest") wines are made from grapes that have achieved minimum defined potential alcohol levels. Those minimum requirements differ by region and grape variety. Essentially, Auslese is the third level of reserve grape selection.

- Beerenauslese wines ("berry selection") are made from grapes that have achieved minimum defined potential alcohol levels. The concentration of the grape juice may have been facilitated by a fungus Botrytis, which perforates the skin of the grape forcing water to drip out and all remaining elements to concentrate. Due to the high potential alcohol level required for this category of ripeness, these wines are generally made into sweet wines and can make good dessert wines.

- Trockenbeerenauslese wines ("dry berries selection") are made from grapes of an even higher potential alcohol level, generally reachable only with the help of Botrytis. The grapes used for Trockenbeerenauslese have reached an even more raisin-like state than those used for Beerenauslese. Due to the high concentration of sugar in the raisin-like grape, these wines can only be made in a sweet style and make extremely sweet, concentrated and usually quite expensive wines.

- Eiswein (ice wine) wine is made grapes that freeze naturally on the vine and have to reach the same potential alcohol level as Beerenauslese. The grapes are harvested and pressed in the frozen state. The ice stays in the press during pressing and hence a concentrated juice flows off the press leading to higher potential alcohol levels, which in turn generally result in sweet wines due to the high potential alcohol. The taste differs from the other high-level wines since Botrytis infection is usually lower, ideally completely absent.

On wine labels, German wine may be classified according to the residual sugar of the wine. Trocken refers to dry wine. These wines have less than 9 grams/liter of residual sugar. Halbtrocken wines are off-dry and have 9–18 grams/liter of residual sugar. Due to the high acidity ("crispness") of many German wines, the taste profile of many halbtrocken wines fall within the "internationally dry" spectrum rather than being appreciably sweet. Feinherb wines are slightly sweeter than halbtrocken wines. Lieblich wines are noticeably sweet; except for the high category Prädikatsweine of type Beerenauslese and above, lieblich wines from Germany are usually of the low Tafelwein category. The number of German wines produced in a lieblich style has dropped markedly since the style went out of fashion in the 1980s.

In recent years, the Verband Deutscher Prädikatsweingüter (VDP), which is a private marketing club founded in 1910, has lobbied for the recognition of a vineyard classification, but its effort have not yet changed national law.

There are also several terms to identify the grower and producers of the wine:

- Weingut refers to a winegrowing and wine-producing estate, rather craft than industry.

- Weinkellerei refers to a maturing and bottling facility, a bottler or shipper.

- Winzergenossenschaft refers to a winemaking cooperative.

- Gutsabfüllung refers to a grower/producer wine that is estate bottled.

- Abfüller refers to a bottler or shipper.

Industry structure

[edit]The German wine scene consists of many small craft oriented vineyard owners. The 2023 viticultural survey counted 14.150 vineyard owners, down from 76 683 in Western Germany in 1989/90. Most of the 2.570 operators of less than 0.5 ha should likely be classified as hobby winemakers. Two digit decreases of operating owners change the structure.[2] Many smaller vineyard owners do not pursue viticulture as a full-time occupation, but rather as a supplement to other agriculture or to hospitality. It is not uncommon for a visitor to a German wine region to find that a small family-owned Gasthaus has its own wine. Smaller grape-growers who do not wish to, or are unable to, commercialise their own wine have several options available: sell the grapes (either on the market each harvest year, or on long-term contract with larger wineries looking to supplement their own production), deliver the grapes to a winemaking cooperative (called Winzergenossenschaft in Germany), or sell the wine in bulk to winemaking firms that use them in "bulk brands" or as a base wine for Sekt. Those who own vineyards in truly good locations also have the option of renting them out to larger producers to operate.

A total of 5,864 vineyard owners owned more than 5 ha each in 2016, accounting for 81% of Germany's total vineyard surface, and it is in this category that the full-time vintners and commercial operations are primarily found.[24] However, truly large wineries, in terms of their own vineyard holdings, are rare in Germany. Hardly any German wineries reach the size of New World winemaking companies, and only a few are of the same size as a typical Bordeaux Grand Cru Classé château. Of the ten wineries considered as Germany's best by Gault Millau Weinguide in 2007,[25] nine had 10,2 — 19 ha of vineyards, and one (Weingut Robert Weil, owned by Suntory) had 70 ha. This means that most of the high-ranking German wineries each only produces around 100,000 bottles of wine per year. That production is often distributed over, say, 10–25 different wines from different vineyards, of different Prädikat, sweetness and so on. The largest vineyard owner is the Hessian State Wineries (Hessische Staatsweingüter), owned by the state of Hesse, with 200 ha vineyards, the produce of which is vinified in three separate wineries.[26] The largest privately held winery is Dr. Bürklin-Wolf in the Palatinate with 85,5 ha.[27]

Largest German wineries

[edit]By April 2014, the ten largest German wine producers were:[28]

- Weingut Lergenmüller Hainfeld (Palatinate), 110 ha; and Schloss Reinhartshausen, 80 ha[29]

- Juliusspital, Würzburg (Franken), 170 ha

- Weingut Heinz Pfaffmann, Walsheim (Palatinate), 150 ha

- Hessische Staatsweingüter Eltville (Rheingau), 140 ha

- Markgraf von Baden Salem (Baden), 140 ha

- Bischöfliche Weingüter Trier (Mosel), 95 ha

- Staatlicher Hofkeller Würzburg (Franconia), 120 ha

- Weingut Anselmann Edesheim (Palatinate), 115 ha

- Bürgerspital zum Heiligen Geist Würzburg (Franconia), 110 ha

- Weingut Friedrich Kiefer Eichstetten am Kaiserstuhl (Baden), 110 ha

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Iron Age Celts bonded over love of wine, suggests study". 24 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d German Wine Institute, German Wine Statistics 2024–2025 (PDF-file; 700 kB). Retrieved 11 January 2025.

- ^ Andrew Ellson, Roll out the riesling, German wines are making a comeback, in: The Times, 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Jason Wilson, How German Wine Found Its Sweet Spot, in: The Washington Post, 5 September 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b The wine regions of Germany.

- ^ a b c d e f Entry on "German History" in J. Robinson (ed) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition, pp. 304-308, Oxford University Press 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ Wein-Plus Glossar: Pinot noir, accessed on February 17, 2008.

- ^ Wein-Plus Glossar: Kloster Eberbach, accessed on February 17, 2008.

- ^ German Wine Institute: Wine growing regions Archived 2008-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on February 17, 2008.

- ^ Wein.de (German Agricultural Society): 13 winegrowing areas in Germany Archived 2007-10-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Entry on "Baden" in J. Robinson (ed) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition, p. 59, Oxford University Press 2006 ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ "Your 2022 guide to Baden Wine Route". www.winetourism.com. 2022-09-02. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ Wein-Plus Glossar: Pfalz, accessed on December 16, 2007.

- ^ http://www.graf-von-katzenelnbogen.de/ All about The History of the County of Katzenelnbogen and the First Riesling of the World.

- ^ Weinverordnung (WeinV 1995), updated until Art. 1 V v. 11.3.2008 I 383, § 1 for Tafelwein and § 2 for Landwein.

- ^ Bird, Owen (2005). Rheingold – The German wine renaissance. Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk: Arima publishing. pp. 259–260. ISBN 1-84549-079-7.

- ^ a b German Wine Institute: German Wine Statistics 2023–2024.

- ^ German Wine Institute: German Wine Statistics 2005–2006 Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German Wine Institute: German Wine Statistics 2006–2007 Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Entry on "Silvaner" in J. Robinson (ed), "The Oxford Companion to Wine", Third Edition, pp. 630-631, Oxford University Press 2006, ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ Silvaner Archived 2017-04-29 at the Wayback Machine subtle, shapely & stylish, retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Walter Hillebrand, Heinz Lott & Franz Pfaff (2003). Taschenbuch der Rebsorten, 13th edition. Mainz: Fachverlag Fraund. ISBN 3-921156-53-X.

- ^ Thomas Brandl, Bio-Wein boomt immer stärker (Organic wine is booming stronger) retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ German Wine Institute, German Wine Statistics 2019–2020 (PDF-file; 700 kB). Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Weinguide.de: Unsere Besten Archived 2007-12-14 at the Wayback Machine, accessed on December 16, 2007.

- ^ Wein-Plus Glossar: Hessische Staatsweingüter, accessed on December 16, 2007.

- ^ Wein-Plus Glossar: Bürklin-Wolf, accessed on December 16, 2007.

- ^ List of wineries indicating the biggest German producers Archived 2015-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, germanwines.de, retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ http://michael-liebert.de/weintipps/schloss-reinhartshausen-lergenmueller-neuer-besitzer/ Archived 2013-04-20 at the Wayback Machine Weingut Lergenmüller – new owner of Schloss Reinhartshausen.

General sources

[edit]- Barr, Andrew (1988). Wine Snobbery: An Insiders Guide to the Booze Business. ISBN 0-571-15060-8. Chapter 8 on history of sweetness in German wines.

- Brook, Stephen (2006). The Wines of Germany. ISBN 978-1840007916.

- Hallgarten, S.F. (1981). German Wines. ISBN 0-9507410-0-0.

- Langenbach, Alfred (1962). German Wines and Vines. Vista Books. OCLC 5530662.

- Reinhardt, Stephan (2012). The Finest Wines of Germany: A Regional Guide to the Best Producers and Their Wines. ISBN 978-0520273221.

External links

[edit]- German Wine Institute

- Weyman, C. S. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

German wine

View on GrokipediaHistory

Ancient and Early History

The earliest indications of viticulture in what is now Germany trace back to pre-Roman times, with archaeological evidence suggesting that Celtic tribes in the region appreciated wine as a luxury beverage around 500 BC along the Mosel River valley. Although definitive proof of organized wine production remains elusive, the presence of wild grapevines (Vitis vinifera sylvestris) and imported wine residues in Celtic settlements points to this appreciation, though no records of local cultivation exist.[8][9] Germanic tribes in the area similarly encountered grape cultivation through trade and cultural exchange, but systematic viticulture awaited external influences.[8][9] The Romans introduced organized viticulture to Germany during their expansion into the region starting around 50 BC, with the first vineyards established along the Rhine and Mosel valleys by the 1st century AD to supply wine for legions and settlers. Archaeological finds, including pruning tools, wine presses, and grape seeds from sites near Trier (founded as Augusta Treverorum in 17 BC), confirm that Roman estates transformed steep riverbank slopes into productive vineyards, marking the Mosel as Germany's oldest wine-growing area. By the 3rd century AD, production facilities proliferated in the Mosel and Neckar regions, integrating wine into the local economy and daily life of the Roman province of Germania Superior. This era laid the cultural foundation for viticulture, as Romans adapted Mediterranean techniques to the cooler climate.[5][10][11] Following the Roman withdrawal around 400 AD, viticulture persisted but declined amid invasions and instability during the Migration Period (5th-8th centuries). Christian monasteries emerged as key preservers of Roman agricultural knowledge, with Benedictine and other orders maintaining vineyards for sacramental wine and self-sufficiency; sites like the Lorsch Abbey, founded in 764 AD, documented early medieval vine cultivation. This monastic stewardship ensured the survival of vines through turbulent times. A pivotal advancement came in the early 9th century under Charlemagne, whose Capitulare de villis (c. 800 AD) mandated the cultivation of vines on royal estates, listing them among essential crops and promoting expansion across Frankish territories, including modern Germany.[5][12][13]Medieval to 19th Century Developments

During the medieval period, monastic orders significantly advanced viticulture in Germany, institutionalizing wine production through systematic vineyard expansion and cultivation techniques. The Benedictines, arriving in German territories around the 8th century, established numerous abbeys and prioritized agricultural self-sufficiency, including the planting of vineyards as part of their rule emphasizing manual labor.[14] By the 12th century, the Cistercians, a reform branch of the Benedictines, further propelled this growth, founding monasteries like Kloster Eberbach in the Rheingau region in 1136, where they developed extensive estates focused on high-quality wine production.[15] These orders not only cleared land for new plantings but also refined pruning, soil management, and fermentation methods, making wine a staple for religious rituals, medicinal use, and trade across the Holy Roman Empire from the 8th to 15th centuries.[16] Wine became integral to the Holy Roman Empire's economy by the late Middle Ages, serving as a key commodity that supported regional prosperity and international commerce. Rhine wines, known as Rhenish, gained prominence for their quality and were exported to England starting in the 13th century, where they were favored by nobility and merchants for their crisp acidity and longevity, often transported via Hanseatic League networks.[17] By the 14th century, the Hanseatic League facilitated the shipment of German wines to Baltic ports, integrating viticulture into broader trade routes that exchanged goods like timber, furs, and salt, thereby elevating wine's status as an economic driver in cities such as Mainz and Frankfurt.[18] The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) severely disrupted this progress, leading to widespread devastation of vineyards through battles, pillaging, and neglect, which reduced Germany's cultivated area by over half and caused a sharp decline in production.[5] Recovery in the 18th century was gradual, aided by Enlightenment-era agricultural reforms that promoted scientific approaches to viticulture, such as improved grafting and site selection, allowing regions like the Mosel and Rheingau to regain prominence with wines commanding premium prices rivaling those from Bordeaux.[19][20] The mid-19th century brought a new crisis with the phylloxera outbreak, which first reached German vineyards around 1868 in Baden and rapidly spread, destroying up to two-thirds of plantings by feeding on roots and causing economic hardship for growers.[21] In response, viticulturists adopted grafting European Vitis vinifera scions onto resistant American rootstocks, a technique that preserved varietals like Riesling while enabling replanting on a large scale.[22] This crisis prompted regulatory advancements, including late 19th-century Prussian vineyard classifications and regulations, which standardized quality controls, site evaluations, and anti-adulteration measures to rebuild trust in German wines leading into unification.[23]20th Century to Modern Era

The two World Wars severely disrupted German viticulture, causing widespread destruction of vineyards, labor shortages, and neglect due to wartime priorities and food rationing that diverted resources from wine production. In West Germany after World War II, growers formed and expanded cooperatives to pool resources, improve quality control, and facilitate rebuilding, with many such organizations dating back to the late 19th century but gaining momentum in the postwar economic recovery. In contrast, East Germany's wine sector was fully collectivized under the German Democratic Republic (GDR), where private production was prohibited and state-run cooperatives managed vineyards to prioritize bulk output for domestic consumption and exports to socialist bloc countries. The 1971 Wine Law marked a pivotal reform, introducing a ripeness-based classification system for quality wines (Qualitätswein) and Prädikat levels—ranging from Kabinett (fully ripened grapes) to Trockenbeerenauslese (botrytis-affected, raisined berries)—to emphasize grape maturity over mere volume, while standardizing regional designations and yield controls to elevate overall standards. This legislation addressed earlier overproduction issues by incentivizing selective harvesting and reducing emphasis on sweeter, lower-quality wines that had tarnished Germany's reputation abroad. German reunification in 1990 brought integration challenges, including outdated equipment and hybrid varieties in former East German regions like Saxony and Saale-Unstrut, alongside a sudden influx of Western market competition that initially collapsed state cooperatives. However, EU membership and subsidies facilitated a revival, funding vineyard restructuring and expansion—such as in Saxony, where plantings grew from 200 to 450 hectares through replanting grants and modernization aid—enabling private estates to emerge and focus on premium varieties like Riesling. Successes included rapid quality improvements, with East German wines gaining recognition in fine dining, and boosted tourism along routes like Saxony's Elbe Valley wine trail, which saw visitor numbers double from 1994 to 2018. In recent years, the industry has navigated climate variability with a commitment to quality-driven production. The 2025 harvest totaled 7.3 million hectolitres according to final estimates, a 7% decrease from 2024's 7.8 million hectolitres due to challenging weather conditions including frosts and heavy rain, marking the smallest yield in 15 years and 16% below the 10-year average. Despite the reduced volume, the 2025 vintage is noted for high quality, with healthy grapes preserving acidity and aroma; white varieties continued to dominate the output.[24] Exports surged in volume by 3% to 1.2 million hectolitres in 2024—about 15% of total production—driven by demand in markets like the Netherlands and Poland, while values held steady at €384 million amid stable pricing.Geography and Climate

Topography and Regional Features

Germany's wine-growing regions are situated in the temperate zone between approximately 47° and 55° N latitude, placing them among the northernmost viticultural areas in the world.[25] The country's over 100,000 hectares of vineyards are predominantly concentrated along major river valleys, including the Rhine, Mosel, and Danube, where these waterways provide essential moderation of temperatures and facilitate the transport of grapes.[25] This riverine topography creates sheltered microenvironments conducive to grape ripening in an otherwise cool climate, with vineyards often positioned on south- or southwest-facing slopes to maximize sunlight exposure.[26] Key topographical features vary significantly across regions, influencing the suitability for viticulture. In the Mosel Valley, vineyards cling to exceptionally steep slate slopes, some reaching inclines of up to 65°—as seen at Bremmer Calmont—requiring manual harvesting and terracing to combat erosion and optimize drainage.[25] The Rheingau features more gently terraced hills along the Rhine, providing a balance of elevation and protection from northerly winds.[25] Northern areas, such as Saale-Unstrut, experience cooler conditions due to their higher latitude, while southern regions like Baden and Württemberg benefit from warmer influences, resulting in a north-south gradient that diversifies terroir expressions.[25] Soil diversity further defines these landscapes, contributing to unique terroir profiles without dictating specific varietal outcomes. The Mosel is characterized by blue and gray slate soils that retain heat and minerals, enhancing acidity in wines.[25] In the Pfalz, deep loess deposits offer fertility and water retention suited to expansive plains.[25] The Nahe region showcases volcanic origins, with porphyry and melaphyre soils imparting mineral complexity and promoting root depth.[25] This variety of parent rocks and sediments across Germany's 13 regions underscores the interplay between geology and elevation in shaping viticultural potential.[25] The total vineyard area stood at approximately 103,000 hectares as of 2024, remaining stable with slight fluctuations driven by conversions to organic farming and new plantings.[27]Climatic Conditions

Germany's wine-growing regions lie within a cool continental climate zone, influenced by westerly Atlantic winds and the tempering effects of the Gulf Stream, which moderates winters to prevent excessive cold. The growing season, spanning April to October, experiences average temperatures of 16-18°C, with vegetation periods often reaching 18°C or higher to support ripening. Long sunshine hours—up to 1,300 annually—extend photosynthesis during summer, allowing grapes to develop slowly and retain high acidity, a hallmark of German wines.[26] Annual precipitation ranges from 500-800 mm, concentrated primarily in summer, which can promote fungal diseases but also ensures sufficient water for vine growth. Spring frost poses a significant risk to budding vines, particularly in higher elevations, while autumn often brings harvest rains that challenge pickers to balance ripeness and quality. In river valleys like the Mosel and Rhine, frequent morning fog during cooler nights helps preserve acidity by limiting rapid sugar accumulation, contributing to the crisp profiles of varieties such as Riesling.[28] Microclimates vary notably across regions, enhancing viticultural suitability. The Rhine Valley benefits from the river's heat retention, storing daytime warmth to elevate nighttime temperatures and accelerate ripening in areas like Rheingau. In contrast, the Mosel's steeper, slate-strewn slopes create cooler nights, fostering extended hang times that build complex flavors without losing freshness. These localized conditions, combined with the overall maritime influence, distinguish German cool-climate viticulture from warmer European counterparts.[26][28] Since the 1990s, rising temperatures—averaging an increase of about 1°C in growing season means—have led to earlier, warmer harvests, reducing frost threats but enabling riper fruit for red varieties like Spätburgunder that previously struggled to fully mature. This shift has expanded the potential for fuller-bodied reds while maintaining the acidity-driven elegance of whites.[4][29]Climate Change Impacts

Climate change has significantly altered German viticulture, with rising temperatures leading to earlier grape harvests by approximately 2-3 weeks compared to the 1980s, driven by accelerated ripening cycles.[30][31] This shift has resulted in reduced acidity and elevated sugar levels in grapes, contributing to higher alcohol content in wines and challenging traditional styles like crisp Rieslings.[32][33] In 2024, severe drought and extreme weather, including late frosts and fungal pressures, caused yield reductions of up to 70-73% in regions like Sachsen and Saale-Unstrut, dropping national production to 7.75 million hectolitres.[34][35] The 2025 harvest yielded approximately 7.3 million hectolitres, a 7% decrease from 2024 and the smallest in 15 years, though with promising quality for fruity, easy-drinking wines due to early ripening, maintained acidity, and late-season rains in many regions.[36][37] Extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change have inflicted substantial damage on German vineyards, including hailstorms, heatwaves, and floods. The 2021 flood in the Ahr Valley destroyed around 10% of the region's vineyards, caused over €1.4 billion in damages, and resulted in more than 130 fatalities, underscoring the vulnerability of steep, river-adjacent sites.[38][39] Heatwaves have intensified drought stress, while projections indicate yield variability could reach 20-30% by 2050 due to increased frequency of such events and shifting precipitation patterns.[40][41] German winegrowers are adapting through viticultural innovations, such as adopting heat-tolerant rootstocks like those derived from Vitis berlandieri hybrids to enhance drought resistance and water efficiency.[42][43] Higher trellising systems are being implemented to elevate vines, reducing heat stress on fruit clusters and improving air circulation.[44] Warmer winters have prompted research into elevated disease pressures, as milder conditions allow pests like phylloxera to overwinter more effectively, necessitating increased monitoring and resistant varieties.[45] Policy responses include EU-funded programs to bolster resilience, such as the LIFE VinEcos project, which enhances biodiversity in Saxony-Anhalt vineyards to mitigate climate impacts.[46] The RESPOnD initiative supports alpine viticulture adaptation through vulnerability assessments and sustainable practices.[47] By 2024, cultivation of PiWi (fungus-resistant) varieties expanded by 10% to 3,500 hectares, with varieties like Solaris showing promise for overall climate resilience, including reduced pesticide needs amid rising disease risks.[48][49]Wine Regions

Major Growing Regions

Germany's 13 Anbaugebiete, or quality wine regions, are defined by their diverse terroirs, which combine unique geological formations, river valleys, and microclimates to produce distinctive wine styles renowned for elegance and minerality. These regions stretch from the northernmost vineyards along the Elbe and Saale rivers to the sun-soaked southwest near the Black Forest, with many hugging river courses that moderate temperatures and reflect sunlight onto steep slopes. The interplay of slate, volcanic, loess, and limestone soils imparts specific flavors, such as the smoky minerality from slate or the aromatic freshness from volcanic origins, fostering wines that reflect their precise origins.[50] The Ahr, Germany's northernmost and smallest red wine-focused region, features steep slate and basalt slopes along a 25-kilometer river stretch, creating a cool-climate terroir ideal for structured Pinot Noir with earthy, red-fruited profiles. Despite the devastating 2021 flood that destroyed much of the infrastructure, the region has shown remarkable resilience, with ongoing recovery efforts rebuilding vineyards and cellars while maintaining its signature spicy, age-worthy reds. Further north, the Mittelrhein boasts dramatic, terraced vineyards on slate cliffs along the Rhine, a UNESCO World Heritage site, yielding tense, mineral-driven Rieslings noted for their vibrant acidity and herbal notes from the steep, wind-exposed sites.[50][51][52] The Mosel, encompassing the Saar and Ruwer tributaries, is famed for its extreme steepness—up to 68% gradients—and blue, gray, and red slate soils covering approximately 8,000 hectares, which retain heat and impart a signature slate-derived petrol and citrus minerality to its filigree Rieslings. These long-ripening wines (100-130 days) develop piercing acidity and ethereal aromas, with sub-regions like the Terrassenmosel showcasing terraced slate hillsides. Adjacent, the Rheingau's Taunus slopes and Rhine River reflections create a balanced terroir of slate and loess, producing elegant, structured Rieslings with orchard fruit and spice, alongside Pinot Noirs from cooler, slate-rich sites near Assmannshausen.[50][53][54] The Nahe, nestled between the Mosel and Rhine, exhibits extraordinary geological diversity with over 180 soil types from volcanic, slate, and quartzite origins, resulting in complex, deep wines that range from flinty Rieslings to full-bodied whites and reds across its hilly sub-regions like the Traisen and Alsenz valleys. Volcanic influences in areas like the Bastei yield aromatic, mineral-edged styles with smoky depth. Nearby, Rheinhessen's expansive, sun-drenched plateaus (1,500 sunshine hours annually) feature varied loess and limestone soils, enabling innovative, versatile wines with ripe fruit and freshness, revitalized by young growers emphasizing terroir-driven expressions. The Pfalz, further south, benefits from a warm, Mediterranean-like climate with 1,800 sunshine hours and a mix of sandstone, limestone, and volcanic soils, crafting grand, dry wines that blend elegance with body, particularly in sub-regions like the Mittelhaardt.[50][55][56] In the southwest, Baden's diverse terroir spans the Black Forest's granite and volcanic Kaiserstuhl volcanoes to Lake Constance's mild lake influences, fostering a wide array of styles with a strong emphasis on Pinot varieties; the 2025 harvest volume increased by 24% in the region, with significant gains in Pinot Noir and Blanc, highlighting its warming climate's potential for fuller, aromatic expressions. Württemberg's calcareous Neckar Valley slopes around Stuttgart yield robust, spicy reds from limestone and Keuper soils, with earthy depth suited to local tastes. The Hessische Bergstraße, a compact Odenwald hillside region, features quartzite and loess over sandstone, producing pure, racy Rieslings with floral and stone-fruit notes from its south-facing, sheltered slopes.[50][57][3] Eastern regions like Franken (Franconia) stand out for their Main River valley's unique geology of shell limestone, marl, and gypsum, bottling dry, mineral whites—especially Silvaner—in the iconic flat, round Bocksbeutel flasks that evoke the area's historic, earthy styles with quince and pepper nuances. Over 40% of Franken's wines use this traditional vessel, underscoring its commitment to regional identity. The northernmost duo, Saale-Unstrut and Sachsen, endure a continental climate with cold winters and hot summers amid limestone cliffs and river terraces; Saale-Unstrut's steep, shell-limestone slopes produce fresh, aromatic whites with herbal vibrancy, while Sachsen's Elbe Valley terraces near Dresden yield filigreed, intense wines from granite and loess, emphasizing the cool-climate finesse of these outlier terroirs.[50][58][59]Regions by Vineyard Area

Germany's 13 wine-growing regions vary significantly in size, with vineyard areas ranging from expansive plains to compact, steeply sloped terrains. The total vineyard area stood at 103,295 hectares in 2024, concentrated primarily in the southwestern and central parts of the country.[2] Rheinhessen leads as the largest region with 27,671 hectares, accounting for approximately 26.8% of the national total, followed closely by Pfalz at 23,787 hectares (23.0%) and Baden at 15,454 hectares (15.0%).[60] These three regions together represent over 64% of Germany's planted vineyards, emphasizing the dominance of the Rhine Valley areas in terms of scale. In contrast, the smallest region, Hessische Bergstraße, covers just 456 hectares (0.4%), highlighting the diversity in regional footprints.[60]| Region | Vineyard Area (2024, ha) | Share of Total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Rheinhessen | 27,671 | 26.8 |

| Pfalz | 23,787 | 23.0 |

| Baden | 15,454 | 15.0 |

| Württemberg | 11,179 | 10.8 |

| Mosel | 8,445 | 8.2 |

| Franken | 6,128 | 5.9 |

| Nahe | 4,234 | 4.1 |

| Rheingau | 3,180 | 3.1 |

| Saale-Unstrut | 858 | 0.8 |

| Sachsen | 529 | 0.5 |

| Ahr | 533 | 0.5 |

| Mittelrhein | 451 | 0.4 |

| Hessische Bergstraße | 456 | 0.4 |

| Total | 103,295 | 100 |