Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gymnastics

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Gymnastics is a group of sport that includes physical exercises requiring balance, strength, flexibility, agility, coordination, artistry and endurance.[1] The movements involved in gymnastics contribute to the development of the arms, legs, shoulders, back, chest, and abdominal muscle groups. Gymnastics evolved from exercises used by the ancient Greeks that included skills for mounting and dismounting a horse.[2]

The most common form of competitive gymnastics is artistic gymnastics (AG); for women, the events include floor, vault, uneven bars, and balance beam; for men, besides floor and vault, it includes rings, pommel horse, parallel bars, and horizontal bar.

The governing body for competition in gymnastics throughout the world is the Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG). Eight sports are governed by the FIG, including gymnastics for all, men's and women's artistic gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics (women's branch only), trampolining (including double mini-trampoline), tumbling, acrobatic, aerobic, parkour and para-gymnastics.[3] Disciplines not currently recognized by FIG include wheel gymnastics, aesthetic group gymnastics, TeamGym, men's rhythmic gymnastics (both the Spanish form which is identical to the women's version and the Japanese version which is a different sport) and mallakhamba.

Participants in gymnastics-related sports include young children, recreational-level athletes, and competitive athletes at all skill levels.

Etymology

[edit]The word gymnastics derives from the common Greek adjective γυμνός (gymnos),[4] by way of the related verb γυμνάζω (gymnazo), whose meaning is to "train naked", "train in gymnastic exercise", generally "to train, to exercise".[5] The verb had this meaning because athletes in ancient times exercised and competed without clothing.

History

[edit]Gymnastics can be traced to exercises performed in Ancient Greece, specifically in Sparta and Athens. Exercise of that time was documented by Philostratus'[6] work Gymnastics: The Ethics of an Athletic Aesthetic. The original term for the practice of gymnastics is from the related Greek verb γυμνάζω (gumnázō), which translates as "to train naked or nude," because young men exercised without clothing. In ancient Greece, physical fitness was highly valued among both men and women. It was not until after the Romans conquered Greece in 146 BC that gymnastics became more formalized and was used to train men in warfare.[7] On Philostratus' claim that gymnastics is a form of wisdom, comparable to philosophy, poetry, music, geometry, and astronomy,[6] the people of Athens combined this more physical training with the education of the mind. At the Palestra, a physical education training center, the disciplines of educating the body and the mind were combined, allowing for a form of gymnastics that was more aesthetic and individual and that left behind the focus on strictness, discipline, the emphasis on defeating records, and a focus on strength.[8]

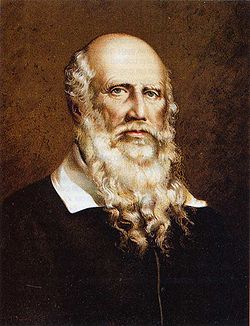

Don Francisco Amorós y Ondeano—a Spanish colonel born on 19 February 1770, in Valencia, who died on 8 August 1848, in Paris—was the first person to introduce educative gymnastics in France. The German Friedrich Ludwig Jahn began the German gymnastics movement in 1811 in Berlin, which led to the invention of the parallel bars, rings, the horizontal bar, the pommel horse and the vault horse.[9]

Germans Charles Beck and Charles Follen and American John Neal brought the first wave of gymnastics to the United States in the 1820s. Beck opened the first gymnasium in the US in 1825 at the Round Hill School in Northampton, Massachusetts.[10] Follen opened the first college gymnasium and the first public gymnasium in the US in 1826 at Harvard University and in Boston, Massachusetts, respectively.[11] Neal was the first American to open a public gymnasium in the US, in Portland, Maine, in 1827.[12] He also documented and promoted these early efforts in the American Journal of Education[13] and The Yankee, helping to establish the American branch of the movement.[14]

The Federation of International Gymnastics (FIG) was founded in Liege in 1881.[15] By the end of the nineteenth century, men's gymnastics competition was popular enough to be included in the first modern Olympic Games, in 1896.[16] From then until the early 1950s, both national and international competitions involved a changing variety of exercises gathered under the rubric, gymnastics, which included, for example, synchronized team floor calisthenics, rope climbing, high jumping, running, and horizontal ladder. During the 1920s, women organized and participated in gymnastics events. Elin Falk revolutionized how gymnastics was taught in Swedish schools between 1910 and 1932.[17] The first women's Olympic competition was limited, involving only synchronized calisthenics and track and field. These games were held in 1928 in Amsterdam.

By 1954, Olympic Games apparatus and events for men and women had been standardized in a modern format, and uniform grading structures (including a point system from 1 to 15) had been agreed upon. In 1930, the first UK mass movement organization of women in gymnastics, the Women's League of Health and Beauty, was founded by Mary Bagot Stack in London.[18] At this time, Soviet gymnasts astounded the world with highly disciplined and difficult performances, setting a precedent that continues. Television has helped publicize and initiate a modern age of gymnastics. Both men's and women's gymnastics now attract considerable international interest, and excellent gymnasts can be found on every continent.

In 2006, a new points system for Artistic gymnastics was put into play. An A Score (or D score) is the difficulty score, which as of 2009 derives from the eight highest-scoring elements in a routine (excluding Vault), in addition to the points awarded for composition requirements; each vault has a difficulty score assigned by the FIG. The B Score (or E Score), is the score for execution and is given for how well the skills are performed.[19]

FIG-recognized disciplines

[edit]The following disciplines are governed by FIG.

Artistic gymnastics

[edit]

Artistic gymnastics is usually divided into men's and women's gymnastics. Men compete on six events: floor exercise, pommel horse, still rings, vault, parallel bars, and horizontal bar, while women compete on four: vault, uneven bars, balance beam, and floor exercise. In some countries, women at one time competed on the rings, horizontal bar, and parallel bars (for example, in the 1950s in the USSR).

In 2006, FIG introduced a new point system for artistic gymnastics.[19] Unlike the old code of points, in which there was a maximum 10.0 score, there are two separate scores that are added to produce the final score. The first is the execution score, which starts at 10 and has deductions taken for execution mistakes, and the second is the difficulty score, which is open-ended and based on what elements the gymnasts perform. It may be lower than the intended difficulty score if the gymnast does not perform or complete all the skills, or they do not connect a skill meant to be connected to another. Scoring for national developmental levels or outside of the FIG competition system may continue to use the 10.0 system; for example, US women's collegiate gymnastics still uses the 10.0 system.[21]

Competitive events for women in artistic gymnastics

[edit]

Vault

[edit]In the vaulting events, gymnasts sprint down a 25 metres (82 ft) runway, to take off onto a vault board (or perform a roundoff or handspring entry onto a vault board). They then land momentarily inverted on the hands-on the vaulting horse or vaulting table (pre-flight segment) and propel themselves forward or backward off that platform to a two-footed landing (post-flight segment). The post-flight segment may include one or more saltos, or twisting movements. A round-off entry vault, called a Yurchenko, is a commonly performed vault in the higher levels of women's gymnastics. Other vaults include taking off from the vault board with both feet at the same time and either doing a front handspring or round-off onto the vaulting table.

In 2001, the traditional vaulting horse was replaced with a new apparatus, sometimes known as a tongue, horse, or vaulting table. The new apparatus is more stable, wider, and longer than the older vaulting horse, approximately 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length and 1 metre (3.3 ft) in width, giving gymnasts a larger blocking surface. This apparatus is thus considered safer than the vaulting horse used in the past. With the addition of this new, safer vaulting table, gymnasts are attempting more difficult vaults.[22]

Uneven bars

[edit]On the uneven bars, gymnasts perform a timed routine on two parallel horizontal bars set at different heights. These bars are made of fiberglass covered in wood laminate to prevent them from breaking. In the past, bars were made of wood, but the bars were prone to breaking, providing an incentive to switch to newer technologies. The height of the bars may be adjusted by 5 centimetres (2.0 in) to the size needed by individual gymnasts, although the distance between bars cannot be changed for individual gymnasts in elite competition.

In the past, the uneven parallel bars were closer together. The bars have been moved increasingly further apart, allowing gymnasts to perform swinging, circling, transitional, and release moves that may pass over, under, and between the two bars. At the elite level, movements must pass through the handstand. Gymnasts often mount the uneven bars using a springboard or a small mat, and they may use chalk (MgCO3) and grips (a leather strip with holes for fingers to protect hands and improve performance) when performing this event. The chalk helps take the moisture out of gymnasts' hands to decrease friction and prevent rips (tears to the skin of the hands); dowel grips help gymnasts grip the bar.

Balance beam

[edit]

The gymnast performs a choreographed routine of up to 90 seconds in length consisting of leaps, acrobatic skills, somersaults, turns, and dance elements on a padded beam. The beam is 125 centimetres (4 ft 1 in) above the ground, 5 metres (16 ft 5 in) long, and 10.16 centimetres (4.00 in) wide.[23] It can also be adjusted, to be raised higher or lower.

Floor

[edit]

The event in gymnastics performed on the floor is called floor exercise. In the past, the floor exercise event was executed on the bare floor or mats such as wrestling mats. The floor event now occurs on a carpeted 12 metres (39 ft) x 12 metres (39 ft) square, usually consisting of hard foam over a layer of plywood, which is supported by springs generally called a spring floor. This provides a firm surface that provides extra bounce or spring when compressed, allowing gymnasts to achieve greater height and a softer landing after the composed skill. Gymnasts perform a choreographed routine to music (without words) for up to 90 seconds. The routine should consist of tumbling passes, series of jumps, leaps, dance elements, acrobatic skills, and turns, or pivots, on one foot. A gymnast can perform up to four tumbling passes, each of which usually includes at least one flight element without hand support.[24]

Competitive events for men in artistic gymnastics

[edit]Floor

[edit]Male gymnasts also perform on a 12 metres (39 ft) x 12 metres (39 ft) spring floor. A series of tumbling passes are performed to demonstrate flexibility, strength, and balance. Strength skills include circles, scales, and press handstands. Men's floor routines usually have multiple passes that have to total between 60 and 70 seconds and are performed without music, unlike the women's event. Rules require that male gymnasts touch each corner of the floor at least once during their routine.

Pommel horse

[edit]The pommel horse consists of a horizontal body with two pommels, or handles. Gymnasts perform by using their hands to support themselves on the horse. A typical pommel horse exercise involves both single-leg and double-leg work. Single-leg skills are generally found in the form of scissors, an element often done on the pommels. Double leg work, however, is the main staple of this event. The gymnast swings both legs in a circular motion (clockwise or counterclockwise depending on preference) and performs such skills on all parts of the apparatus. To make the exercise more challenging, gymnasts often include variations on a typical circling skill by turning (moores and spindles) or by straddling their legs (flares). Routines end when the gymnast performs a dismount, either by swinging his body over the horse or landing after a handstand variation.

Still rings

[edit]

The rings are suspended on wire cable from a point 5.75 metres (18.9 ft) from the floor. The gymnast grips the rings and must perform a routine demonstrating balance, strength, power, and dynamic motion while preventing the rings themselves from swinging. At least one static strength move is required, but some gymnasts may include two or three. A routine ends with a dismount.

Vault

[edit]Gymnasts sprint down a runway, which is a maximum of 25 metres (82 ft) runway in length, before hurdling onto a springboard. They then land momentarily inverted on the hands-on the vaulting horse or vaulting table (pre-flight segment) and propel themselves forward or backward off that platform to a two-footed landing (post-flight segment). In advanced gymnastics, multiple twists and somersaults may be added in the post-flight segment before landing. Successful vaults depend on the speed of the run, the length of the hurdle, the power the gymnast generates from the legs and shoulder girdle, the kinesthetic awareness in the air, how well they stuck the landing, and the speed of rotation in the case of more difficult and complex vaults.

Parallel bars

[edit]Men perform on two bars set in parallel by executing a series of swings, balances, and releases that require great strength and coordination. The width between the bars is adjustable depending upon the actual needs of the gymnasts, and the bars are usually 2 metres (6.6 ft) high.

Horizontal bar

[edit]A 2.8 centimetres (1.1 in) thick steel bar raised 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) is raised the landing area. The gymnast holds on to the bar and performs giant swings or giants (forward or backward revolutions around the bar in the handstand position), release skills, twists, and changes of direction. By using the momentum from giants and then releasing at the proper point, enough height can be achieved for spectacular dismounts, such as a triple-back salto. Leather grips are usually used to help maintain a grip on the bar, and to prevent rips. While training for this event, straps are often used to ensure that the gymnasts do not fall off the bar as they are learning new skills.

Rhythmic gymnastics

[edit]

According to FIG rules, only women compete in rhythmic gymnastics. This is a sport that combines elements of ballet, gymnastics, dance, and apparatus manipulation, with a much greater emphasis on the aesthetic rather than the acrobatic.[25] Gymnasts compete either as individuals or in groups. Individuals perform four separate routines, each using one of the four apparatuses—ball, ribbon, hoop, clubs, and formerly, rope—on a floor area. Groups consist of five gymnasts who perform two routines together, one with five of the same apparatus and one with three of one apparatus and two of another; the FIG defines which apparatuses groups use each year.

Routines are given three sub-scores: difficulty, execution, and artistry. Difficulty is open-ended and based on the value given to the elements performed in the routine, and execution and artistry start at ten points and are lowered for specific mistakes made by the gymnasts. The three sub-scores are added together for the final score for each routine.[26]

International competitions are split between Juniors, under sixteen by their year of birth, and Seniors, for women sixteen and over. Gymnasts in Russia and Europe typically start training at a very young age and those at their peak are typically in their late teens (15–19) or early twenties. The largest events in the sport are the Olympic Games, World Championships, European Championships, World Cup and Grand Prix series. The first World Championships were held in 1963, and rhythmic gymnastics made its first appearance at the Olympics in 1984.[27]

Rhythmic gymnastics apparatus

[edit]

- Ball

- The ball may be made of rubber or a similar synthetic material, and it can be of any color. It should rest in the gymnast's hand and not be pressed against the wrist or grasped with the fingers, which incurs a penalty. Fundamental elements of a ball routine include bouncing or rolling the ball.

- Hoop

- The hoop comes up to about the gymnast's hip. It may be made of plastic or wood, and it may be covered with adhesive tape either of the same or different color as the hoop, which may be in decorative patterns. Fundamental requirements of a hoop routine include rotation of the hoop around the hand or body, rolling the hoop on the body or floor, and the gymnast passing through the hoop.

- Ribbon

- The ribbon consists of a handle, which may be made of wood, bamboo, or synthetic materials such as fiberglass, and the ribbon itself, which is made of satin. The ribbon is six meters long, and due to its length, it can easily become tangled or knotted; knots must be undone or the gymnast will be penalized. Fundamental elements of a ribbon routine consist of making continuous shapes with the length of the fabric, such as tight circles (spirals) or waves (snakes), and elements called boomerangs, in which the gymnast tosses the handle, then pulls it back by the end of the ribbon and catches it.

- Clubs

- The clubs may be made of wood or synthetic materials, and they are always used in a pair. They may be connected together by inserting the end of one club into the head of the other. The handles and bodies are typically wrapped with decorative tapes. Fundamental elements of a clubs routine including swinging the heads of the clubs in circles, small throws in which the clubs rotate in the air, and asymmetrical movements.

- Rope

- The rope is made from hemp or a similar synthetic material; it can be knotted and have anti-slip material at the ends, but it does not have handles. The fundamental requirements of a rope routine include leaping and skipping. In 2011, the FIG decided to eliminate the use of rope in senior individual rhythmic gymnastics competitions. It is still sometimes seen in junior group competition.

Men's rhythmic gymnastics

[edit]There are two versions of rhythmic gymnastics for men, neither of which is currently recognized by the FIG. One was developed in Japan in the 1940s and was originally practiced by both boys and girls for fitness, with women still occasionally participating on the club level today. Gymnasts either perform in groups with no apparatus, or individually with apparatus (stick, clubs, rope, or double rings). Unlike women's rhythmic gymnastics, it is performed on a sprung floor, and the gymnasts perform acrobatic moves and flips.[28] The first World Championships was held in 2003. The other version was developed in Europe and uses generally the same rules as the women and the same set of apparatus. It is most prominent in Spain, which has held national men's competitions since 2009 and mixed-gender group competitions since 2021, and France.[29][30] There currently is no World Championships for this form of Men's Rhythmic Gymnastics.

Trampolining

[edit]

Trampolining

[edit]Trampolining and tumbling consists of four events, individual and synchronized trampoline, double mini trampoline, and tumbling (also known as power tumbling or rod floor). Since 2000, individual trampoline has been included in the Olympic Games. The first World Championships were held in 1964.

Individual trampoline

[edit]Individual routines in trampolining involve a build-up phase, during which the gymnast jumps repeatedly to achieve height, followed by a sequence of ten bounces without pause during which the gymnast performs a sequence of aerial skills. Routines are marked out of a maximum score of 10 points. Additional points (with no maximum at the highest levels of competition) can be earned depending on the difficulty of the moves and the length of time taken to complete the ten skills which is an indication of the average height of the jumps. In high level competitions, there are two preliminary routines, one which has only two moves scored for difficulty and one where the athlete is free to perform any routine. This is followed by a final routine, which is again optional (that is, the gymnast is allowed to perform whichever skills they choose). Some competitions restart the score from zero for the finals, while others add the final score to the preliminary results.

Synchronized trampoline

[edit]Synchronized trampoline is similar except that both competitors must perform the routine together and marks are awarded for synchronization as well as the form and difficulty of the moves.

Double-mini trampoline

[edit]Double mini trampoline involves a smaller trampoline with a run-up; two scoring moves are performed per routine. Moves cannot be repeated in the same order on the double-mini during a competition. Skills can be repeated if a skill is competed as a mounter in one routine and a dismount in another. The scores are marked in a similar manner to individual trampoline.

Tumbling

[edit]In tumbling, athletes perform an explosive series of flips and twists down a sprung tumbling track. Scoring is similar to trampolining. Tumbling was originally contested as one of the events in Men's Artistic Gymnastics at the 1932 Summer Olympics, and in 1955 and 1959 at the Pan American Games. From 1974 to 1998 it was included as an event for both genders at the Acrobatic Gymnastics World Championships. The event has also been contested since 1976 at the Trampoline and Tumbling World Championships.

Tumbling is competed along a 25-metre sprung tack with a 10-metre run up. A tumbling pass or run is a combination of 8 skills, with an entry skill, normally a round-off, to whips (similar to a handspring without hand support) and into an end skill. Usually the end skill is the hardest skill of the pass. At the highest level, gymnasts perform transitional skills. These are skills which are not whips, but are double or triple somersaults (usually competed at the end of the run), but now competed in the middle of the run connected before and after by either a whip or a flick.

Competition is made up of a qualifying round and a finals round. There are two different types of competition in tumbling, individual and team. In the team event three gymnasts out of a team of four compete one run each, if one run fails the final member of the team is allowed to compete with the three highest scores being counted. In the individual event qualification, the competitor will compete two runs, one a straight pass (including double and triple somersaults) and a twisting pass (including full twisting whips and combination skills such as a full twisting double straight 'full in back'). In the final of the individual event, the competitor must compete two different runs which can be either twisting or straight but each run normally uses both types (using transition skills).

Acrobatic gymnastics

[edit]

Acrobatic gymnastics (formerly sport acrobatics), often referred to as acro, acrobatic sports or simply sports acro, is a group gymnastic discipline for both men and women. Acrobats perform to music in groups of two, three and four.

There are four international age categories: 11–16, 12–18, 13–19, and Senior (15+), which are used in the World Championships and many other events around the world, including the European Championships and the World Games.

All levels require a balance routine, which focuses on held balance skills, and a dynamic routine, which focuses on flipping elements; 12–18, 13–19, and Seniors are also required to perform a final (combined) routine.

Currently, acrobatic gymnastics scores are marked out of 30.00 for juniors, and they can be higher at the Senior FIG level based on difficulty:

- Difficulty – An open score, which is the sum of the difficulty values of elements (valued from the tables of difficulties) successfully performed in an exercise, divided by 100. This score is unlimited in senior competitions.

- Execution – Judges give a score out of 10.00 for technical performance (how well the skills are executed), which is then doubled to emphasize its importance.

- Artistic – Judges give a score out of 10.00 for artistry (the overall performance of the routine, namely choreography).

There are five competitive event categories:

- Women's Pairs

- Mixed Pairs

- Men's Pairs

- Women's Groups (3 women)

- Men's Groups (4 men)

The World Championships have been held since 1974.

Aerobic gymnastics

[edit]

Aerobic gymnastics (formally sport aerobics) involves the performance of routines by individuals, pairs, trios, groups with 5 people, and aerobic dance and aerobic step (8 people). Strength, flexibility, and aerobic fitness rather than acrobatic or balance skills are emphasized. Seniors perform routines on a 10 m (33 ft) x 10 m (33 ft) floor, with a smaller 7 m (23 ft) x 7 m (23 ft) floor used for younger participants. Routines last 70–90 seconds depending on the age of the participants and the routine category.[31] The World Championships have been held since 1995.

The events consist of:

- Individual Women

- Individual Men

- Mixed Pairs

- Trios

- Groups

- Dance

- Step

Parkour

[edit]On 28 January 2018, parkour, also known as freerunning, was given the go-ahead to begin development as a FIG sport.[32][33] The FIG was planning to run World Cup competitions from 2018 onwards.[needs update] The first Parkour World Championships were planned for 2020, but were delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic,[34][35][36] and instead took place from 15 to 16 October 2022 in Tokyo, Japan.[37]

The events consist of:

- Speedrun

- Freestyle

Para-gymnastics

[edit]Para-gymnastics, gymnastics for disabled athletes with para-athletics classifications, was recognized as a new FIG discipline in October 2024.[38] As an FIG discipline, it currently only covers artistic gymnastics.[39]

Other disciplines

[edit]The following disciplines are not currently recognized by the Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique.

Aesthetic group gymnastics

[edit]

Aesthetic Group Gymnastics (AGG) was developed from the Finnish "naisvoimistelu". It differs from rhythmic gymnastics in that body movement is large and continuous and teams are larger, and athletes do not use apparatus in international AGG competitions. The sport requires physical qualities such as flexibility, balance, speed, strength, coordination and sense of rhythm where movements of the body are emphasized through the flow, expression and aesthetic appeal. A good performance is characterized by uniformity and simultaneity. The competition program consists of versatile and varied body movements, such as body waves, swings, balances, pivots, jumps and leaps, dance steps, and lifts. The International Federation of Aesthetic Group Gymnastics (IFAGG) was established in 2003.[40] The first Aesthetic Group Gymnastics World Championships was held in 2000.[41]

TeamGym

[edit]

TeamGym is a form of competition created by the European Union of Gymnastics, originally named EuroTeam. The first official competition was held in Finland in 1996. TeamGym events consist of three sections: women, men and mixed teams. Athletes compete in three different disciplines: floor, tumbling and trampette. Teams require effective teamwork and tumbling technique.[42] There is no World Championships; however, there has been a European Championships held since 2010.[43]

Wheel gymnastics

[edit]

Wheel gymnasts do exercises in a large wheel known as the Rhönrad, gymnastics wheel, gym wheel, or German wheel. It has also been known as the ayro wheel, aero wheel, and Rhon rod.

There are four core categories of exercise: straight line, spiral, vault and cyr wheel. The first World Championships was held in 1995.[44]

Mallakhamba

[edit]

Mallakhamba (Marathi: मल्लखम्ब) is a traditional Indian sport in which a gymnast performs feats and poses in concert with a vertical wooden pole or rope. The word also refers to the pole used in the sport.

Mallakhamba derives from the terms malla which denotes a wrestler and khamba which means a pole. Mallakhamba can therefore be translated to English as "pole gymnastics".[45] On 9 April 2013, the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh declared mallakhamba as the state sport. In February 2019 the first Mallahkhamb World Championship was held in Mumbai

Non-competitive gymnastics

[edit]General gymnastics, also known as "gymnastics for all", enables people of all ages and abilities to participate in performance groups of 6 to more than 150 athletes. Unlike other forms of gymnastics General Gymnastics is more of a sports program or performing art than a sport. Any "event" from any discipline of gymnastics can be performed and it's not uncommon to see for example still rings event followed by synchronized trampolone followed by step from aerobic gymnastics or even events not currently recognized in gymnastics like aerial silk. They can perform synchronized, choreographed routines. Troupes may consist of both genders and are separated into age divisions. The largest general gymnastics exhibition is the quadrennial World Gymnaestrada, which was first held in 1939. In 1984 gymnastics for all was officially recognized first as a sport program by the FIG (International Gymnastic Federation), and subsequently by national gymnastic federations worldwide with participants that now number 30 million. Non-competitive gymnastics is considered useful for its health benefits.[46]

Scoring (code of points)

[edit]An artistic gymnast's score comes from deductions taken from the start value of a routine's elements. The start value of a routine is based on the difficulty of the elements the gymnast attempts and whether or not the gymnast meets composition requirements. The composition requirements are different for each apparatus. This score is called the D score.[47] Deductions in execution and artistry are taken from a maximum of 10.0. This score is called the E score.[48] The final score is calculated by adding the D and E score.[49]

The current method of scoring, by adding D and E score to give the final score has been in place since 2006.[50] The current method is called "open-end" scoring because there is no theoretical cap (although there is practical cap) to the D-score and hence the total possible score for a routine.[51] Before 2006, a gymnast's final score is deducted from a possible maximum of 10 for a routine.

A Code of Points or guidelines of scoring a routine's difficulty and execution is slightly revised for each quadrennium, or period of four years culminating in the Olympics year.

Former apparatus and events

[edit]Rope climbing

[edit]Generally, competitors climbed either a 6 m (20 ft) or an 8 m (26 ft) long, 38 mm (1.5 in) diameter natural fiber rope for speed, starting from a seated position on the floor and using only the hands and arms. Kicking the legs was normally permitted. Many gymnasts can do this in the straddle or pike position, which eliminates the help generated from the legs, though it can be done with legs as well.

Flying rings

[edit]Flying rings was an event similar to still rings, but with the performer executing a series of stunts while swinging. It was a gymnastic event sanctioned by both the NCAA and the AAU until the early 1960s.

Club swinging

[edit]Club swinging, a.k.a. Indian clubs, was an event in men's artistic gymnastics sometime up until the 1950s. It was similar to the clubs in both women's and men's rhythmic gymnastics, but much simpler, with few throws allowed. It was included in the 1904 and 1932 Summer Olympic Games.

Other (men's artistic)

[edit]- Team horizontal bar and parallel bar in the 1896 Summer Olympics

- Team free and Swedish system in the 1912 and 1920 Summer Olympics

- Combined and triathlon in the 1904 Summer Olympics

- Side horse vault in 1924 Summer Olympics

- Tumbling in the 1932 Summer Olympics

Other (women's artistic)

[edit]- Team exercise at the 1928, 1936, and 1948 Summer Olympics

- Parallel bars at the 1938 World Championships

- Team portable apparatus at the 1952 and 1956 Summer Olympics

Health and safety

[edit]Gymnastics is one of the most dangerous sports, with a very high injury rate seen in girls age 11 to 18.[52]

Some gymnastic movements which were allowed in past competitions are now banned for safety reasons; for example, the Thomas salto, a twisting salto landed with a forward roll on the floor, was banned after several injuries. Elena Mukhina, the 1978 World all-around champion, broke her neck while practicing the skill in an exhausted state and became quadriplegic.[53] The vaulting table replaced the old vaulting horse in the early 2000s and an additional mat was added around the springboard for safety reasons after several female gymnasts, such as Julissa Gomez, became paralyzed during vaulting attempts.[54]

Landing

[edit]In a tumbling pass, dismount, or vault, landing is the final phase, following take-off and flight.[55] This is a critical skill in terms of execution in competition scores, general performance, and injury occurrence. Without the necessary magnitude of energy dissipation during impact, the risk of sustaining injuries during somersaulting increases. These injuries commonly occur at the lower extremities such as cartilage lesions, ligament tears, and bone bruises/fractures.[56] To avoid such injuries, and to receive a high-performance score, proper technique must be used by the gymnast. "The subsequent ground contact or impact landing phase must be achieved using a safe, aesthetic, and well-executed double foot landing."[57] A successful landing in gymnastics is classified as soft, meaning the knee and hip joints are at greater than 63 degrees of flexion.[55]

A higher flight phase results in a higher vertical ground reaction force. Vertical ground reaction force (vGRF) represents an external force which the gymnasts have to overcome with their muscle force and affects the gymnasts' linear and angular momentum. Another important variable that affects linear and angular momentum is the time the landing takes. Gymnasts can decrease the impact force by increasing the time taken to perform the landing. Gymnasts can achieve this by increasing hip, knee and ankle amplitude.[55]

Podium training

[edit]Podium training refers to the official practice session before a gymnastics competition begins. The purpose of this is to enable competing gymnasts to get a feel for the competition equipment inside the arena in which they will be competing,[58] primarily for reasons of safety.

Physical injuries

[edit]Compared to athletes who play other sports, gymnasts are at higher than average risk of overuse injuries and injuries caused by early sports specialization among children and young adults.[59][60] Gymnasts are at particular risk of foot and wrist injuries.[61][62] Strength training can help prevent injuries.

Abuse

[edit]There have been recorded cases of emotional and sexual abuse in gymnastics in many different countries.[63] The USA Gymnastics sex abuse scandal is considered one of the largest abuse scandals in sports history.[64] In 2022, the Whyte Review was published, criticizing extensive abusive practices by British Gymnastics that included sexual and emotional abuse and excessive weight management of athletes.[65]

Height concerns

[edit]Gymnasts tend to have short stature, but it is unlikely that the sport affects their growth. Parents of gymnasts tend also to be shorter than average.[52]

See also

[edit]- Acro dance

- Acrobatics

- Cheerleading

- Fitkid

- Glossary of gymnastics terms

- Gymnasium (ancient Greece)

- International Gymnastics Hall of Fame

- List of acrobatic activities

- List of gymnastics competitions

- List of gymnastics terms

- List of gymnasts

- Major achievements in gymnastics by nation

- Majorettes

- NCAA Men's Gymnastics championship (US)

- NCAA Women's Gymnastics championship (US)

- Trampolining

- Tricking

- Turners

- Uniform (gymnastics)

- World Gymnastics Championships

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Gymnastics | Events, Equipment, Types, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 22 December 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Solly, Meilan. "A History of Gymnastics, From Ancient Greece to Tokyo 2020". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "About the FIG". FIG. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ γυμνός, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- ^ γυμνάζω, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- ^ a b Reid, Heather L. (2016). "Philostratus's "gymnastics": The Ethics of an Athletic Aesthetic". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 61: 77–90. ISSN 0065-6801. JSTOR 44988074.

- ^ "A History of Gymnastics: From Ancient Greece to Modern Times | Scholastic". www.scholastic.com. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ Judd, Leslie; De Carlo, Thomas; Kern, René (1969). Exhibition Gymnastics. New York: Association Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8096-1704-3.

- ^ Goodbody, John (1982). The Illustrated History of Gymnastics. London: Stanley Paul & Co. ISBN 0-09-143350-9.

- ^ Leonard, Fred Eugene (1923). A Guide to the History of Physical Education. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and New York, New York: Lea & Febiger. pp. 232–233.

- ^ Leonard, Fred Eugene (1923). A Guide to the History of Physical Education. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and New York, New York: Lea & Febiger. pp. 235–236.

- ^ Leonard, Fred Eugene (1923). A Guide to the History of Physical Education. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and New York, New York: Lea & Febiger. pp. 227–250.

- ^ Leonard, Fred Eugene (1923). A Guide to the History of Physical Education. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and New York, New York: Lea & Febiger. pp. 235–250. OCLC 561890463.

- ^ Barry, William D. (20 May 1979). "State's Father of Athletics a Multi-Faceted Figure". Maine Sunday Telegram. Portland, Maine. pp. 1D – 2D.

- ^ Artistic Gymnastics History Archived 4 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine at fig-gymnastics.com

- ^ Russell, Keith (2013), "The Evolution of Gymnastics", Gymnastics, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–14, doi:10.1002/9781118357538.ch1, ISBN 978-1-118-35753-8, retrieved 12 December 2024

- ^ "skbl.se - Elin Falk". skbl.se. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ Matthews, Jill Julius (1990). "They had Such a Lot of Fun: The Women's League of Health and Beauty Between the Wars". History Workshop Journal. 30 (1): 22–54. doi:10.1093/hwj/30.1.22. ISSN 1477-4569.

- ^ a b "USA Gymnastics – FIG ×Elite/International Scoring". usagym.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "Lost art: Powerhouse physiques winning out over spellbinding grace". Herald Scotland. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

Unlike Nadia Comaneci and Olga Korbut, modern gymnasts such as Simone Biles are rewarded for their athleticism more than their artistry... the spellbinding artistry that not only gave the sport its name but brought it global fame.

- ^ Grimsley, Elizabeth (5 January 2013). "Gymnastics 101: What to know about scoring, rankings and more before the next GymDog meet". The Red and Black. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Vault: Everything You Need to know about Vault". About.com Sports. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ "Apparatus Norms". FIG. p. II/51. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ "WAG Code of Points 2009–2012". FIG. p. 29. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Tincea, Roxana-Maria (18 June 2019). "The Development of Mobility and Coordination in Rhythmic Gymnastics Performance at Children and Hopes Level". Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov. Series IX: Sciences of Human Kinetics: 145–150. doi:10.31926/but.shk.2019.12.61.19. ISSN 2344-2026.

- ^ "2022–2024 Code of Points Rhythmic Gymnastics" (PDF). International Gymnastics Federation. 25 April 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "FIG - Rhythmic Gymnastics - History". www.gymnastics.sport. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Galofaro, Claire (7 August 2021). "Left out of Olympics, men's rhythmic gymnasts loved in Japan". AP News. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ López, F.; Del Río, P.; Luna, J. (8 July 2020). "Rubén Orihuela: "Pudimos demostrar que estábamos exactamente igual de capacitados"" [Rubén Orihuela: "We were able to show that we were exactly as able"]. RTVE.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "Rhythmic gymnastics: One man's fight for equality". Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ "2022–2024 Code of Points Aerobic Gymnastics" (PDF). International Gymnastics Federation. May 2022.

- ^ "Parkour". We Are Gymnastics FIG GYMNASTICS.COM. FIG/International Gymnastics Federations.

- ^ "Parkour Rules". We Are Gymnastics FIG GYMNASTICS.COM. FIG. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ "Main decisions from the 18th FIG Council in Istanbul". International Gymnastics Federation. Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Hiroshima to host 1st FIG Parkour World Championships in 2020". International Gymnastics Federation. 23 August 2019. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "First FIG Parkour World Championships postponed". www.gymnastics.sport. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Parkour | World Championships | Tokyo". olympics.com. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Para-Gymnastics recognised as official discipline by Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique in 'game changing' vote". www.british-gymnastics.org. 28 October 2024. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "85th FIG Congress concludes in Doha". International Gymnastics Federation. 26 October 2024. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Lajiesittely Archived 21 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Suomen Voimisteluliitto.

- ^ "World Championships | IFAGG". Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "About TeamGym". British Gymnastics. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ "UEG Gymnastics". UEG Gymnastics. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Wheel Gymnastics - rene-heftis Webseite!". Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Indian roots to gymnastics". NDTV – Sports. Mumbai, India. 6 December 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014.

- ^ "Gymnastics For All History". FIG.

- ^ "WAG Code of Points 2009–2012". FIG. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "WAG Code of Points 2009–2012". FIG. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "WAG Code of Points 2009–2012". FIG. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "USA Gymnastics | FIG Elite/International Scoring". usagym.org. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ normile, dwight. "It's Time to Really Make the Code of Points Open-Ended". International Gymnast Magazine Online. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ a b Bergeron, Michael F.; Mountjoy, Margo; Armstrong, Neil; Chia, Michael; Côté, Jean; Emery, Carolyn A.; Faigenbaum, Avery; Hall, Gary; Kriemler, Susi (July 2015). "International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development" (PDF). British Journal of Sports Medicine. 49 (13): 843–851. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094962. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 26084524. S2CID 4984960. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2017.

- ^ Dvora Meyers (2016). The End of the Perfect 10: The Making and Breaking of Gymnastics' Top Score —from Nadia to Now. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-501-10140-3.

- ^ Yan, Holly (13 November 2019). "Gymnastics deaths are rare, but previous disasters have prompted safety changes". CNN. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Marinsek, M. (2010). basic lending. 59–67.

- ^ Yeow, C., Lee, P., & Goh, J. (2009). Effect of landing height on frontal plane kinematics, kinetics, and energy dissipation at lower extremity joints. Journal of Biomechanics, 1967–1973.

- ^ Gittoes, M. J., & Irin, G. (2012). Biomechanical approaches to understanding the potentially injurious demands of gymnastic-style impact landings. Sports Medicine A Rehabilitation Therapy Technology, 1–9.

- ^ Here's Why Podium Training in Gymnastics is Important at the Wayback Machine (archived April 17, 2019)

- ^ Feeley, Brian T.; Agel, Julie; LaPrade, Robert F. (January 2016). "When Is It Too Early for Single Sport Specialization?". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 44 (1): 234–241. doi:10.1177/0363546515576899. ISSN 1552-3365. PMID 25825379. S2CID 15742871.

- ^ Benjamin, Holly J.; Engel, Sean C.; Chudzik, Debra (September–October 2017). "Wrist Pain in Gymnasts: A Review of Common Overuse Wrist Pathology in the Gymnastics Athlete". Current Sports Medicine Reports. 16 (5): 322–329. doi:10.1249/JSR.0000000000000398. ISSN 1537-8918. PMID 28902754. S2CID 4103946.

- ^ Chéron, Charlène; Le Scanff, Christine; Leboeuf-Yde, Charlotte (2016). "Association between sports type and overuse injuries of extremities in children and adolescents: a systematic review". Chiropractic & Manual Therapies. 24: 41. doi:10.1186/s12998-016-0122-y. PMC 5109679. PMID 27872744.

- ^ Wolf, Megan R.; Avery, Daniel; Wolf, Jennifer Moriatis (February 2017). "Upper Extremity Injuries in Gymnasts". Hand Clinics. 33 (1): 187–197. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2016.08.010. ISSN 1558-1969. PMID 27886834.

- ^ Fisher, Leslee A.; Anders, Allison Daniel (3 March 2020). "Engaging with Cultural Sport Psychology to Explore Systemic Sexual Exploitation in USA Gymnastics: A Call to Commitments". Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 32 (2): 129–145. doi:10.1080/10413200.2018.1564944. ISSN 1041-3200. S2CID 149606211.

- ^ Graham, Bryan Armen (16 December 2017). "Why don't we care about the biggest sex abuse scandal in sports history?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Katie Falkingham (16 June 2022). "Gymnastics abuse: Whyte Review finds physical and emotional abuse issues were 'systemic'". BBC Sport. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

Sources

[edit]- "Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique". www.fig-gymnastics.com. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

External links

[edit]- International Federation of Gymnastics (FIG) official website

- International Federation of Aesthetic Group Gymnastics official website

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Gymnastics". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Gymnastics and Gymnasium". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Gymnastics". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

Gymnastics

View on GrokipediaGymnastics is a sport involving displays of physical prowess through exercises that demand strength, balance, flexibility, agility, coordination, and endurance, often utilizing specialized apparatus or performed on mats and floors.[1][2] Its roots trace to ancient civilizations in Greece and China, where such training emphasized bodily development for warfare and athletics.[1][3] The Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG), established in 1881 as the sport's global governing body, oversees competitions across multiple disciplines, including men's and women's artistic gymnastics, rhythmic gymnastics, trampoline gymnastics (encompassing tumbling and double mini-trampoline), acrobatic gymnastics, aerobic gymnastics, parkour, and gymnastics for all.[1] Modern gymnastics emerged in the early 19th century through the efforts of German educator Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, known as the "father of gymnastics," who invented key apparatus like parallel bars and horizontal bars to foster national fitness and strength amid post-Napoleonic revivalism.[4][5] Gymnastics debuted at the inaugural modern Olympic Games in 1896, initially for men, with women's artistic events introduced in 1928 and rhythmic gymnastics in 1984, yielding iconic feats such as Romanian gymnast Nadia Comăneci's unprecedented perfect scores of 10.0 on the uneven bars and balance beam at the 1976 Montreal Olympics.[6][7] While celebrated for athletic excellence—exemplified by American Simone Biles amassing a record 23 World Championships and Olympic gold medals through superior difficulty and execution—the sport grapples with inherent risks and institutional shortcomings.[8] High training intensities contribute to elevated injury rates, including fractures and chronic conditions from repetitive impacts.[9] Moreover, systemic abuse has persisted, as evidenced by the Larry Nassar scandal in USA Gymnastics, where the former team doctor sexually assaulted over 500 athletes amid organizational negligence, prompting lawsuits, bankruptcy threats, and reforms yet underscoring vulnerabilities in elite youth programs driven by performance imperatives over welfare.[10][11]

Etymology and Fundamentals

Etymology

The term "gymnastics" originates from the Ancient Greek verb γυμνάζω (gymnázō), which means "to exercise naked" or "to train vigorously," derived from the adjective γυμνός (gymnós), signifying "naked."[12][13] This etymology reflects the classical Greek practice of performing physical exercises unclothed in public gymnasia, emphasizing disciplined bodily training to cultivate strength, agility, and endurance for athletic competition and military readiness.[14][15] The concept passed into Latin as gymnasticus, referring to expertise in physical exercises, before entering English in the 1570s as "gymnastic," denoting proficiency in bodily training, and by the 1590s as "gymnastics," denoting the systematic practice itself.[16][17] In its original context, the term connoted holistic rigor integrating physical exertion with intellectual and moral development toward aretē (excellence), distinct from contemporary usages tied to recreational fitness or casual wellness.[18][2]Core Principles and Definitions

Gymnastics constitutes a physical discipline predicated on the controlled application of human biomechanics to execute maneuvers involving rotational dynamics, linear acceleration, and equilibrium maintenance under gravitational and inertial forces. At its core, it demands the integration of muscular force generation—primarily through fast-twitch fiber recruitment for explosive actions—with precise neuromuscular timing to manage joint torques and angular momentum conservation, as evidenced in kinematic analyses of vault and beam routines.[19] These principles derive from fundamental physics: performers must counteract body segment inertia via counter-rotations or leverage adjustments, rendering the sport a direct test of causal chains from intent to kinetic outcome rather than aesthetic abstraction.[20] Key enabling attributes include balance, achieved through vestibular and somatosensory feedback loops to sustain center-of-mass projection within base-of-support boundaries; coordination, via synchronized agonist-antagonist muscle pairings for fluid transitions; agility, enabling rapid kinematic reorientations; and explosive power, quantified by peak ground reaction forces exceeding body weight multiples in dismounts.[21] These are not merely trainable but hinge on biomechanical necessities, such as optimal limb segment ratios for rotational efficiency—shorter torsos relative to extremities facilitating aerial twists—independent of coaching interventions.[22] Competitive gymnastics, standardized under the International Federation of Gymnastics (FIG) since its founding in 1881, prioritizes verifiable metrics like difficulty coefficients (e.g., element values from 0.1 to 1.0+ based on risk and originality) and execution scores deducting for form deviations, fostering objective hierarchies of proficiency.[23] [24] In contrast, recreational variants eschew such quantification, focusing on generalized motor skill acquisition without apparatus-specific scoring or qualification thresholds, often diluting emphasis on precision in favor of inclusive participation.[25] Causal determinants of elite capability extend beyond volition to innate predispositions: genetic variants influencing proprioceptive acuity—enabling subconscious kinesthetic mapping—and myofiber composition favor those with elevated type II fiber densities for power output, as twin studies attribute up to 50-80% heritability to such traits in power-oriented athletics.[26] [27] Body levers, including lower limb-to-trunk ratios, confer mechanical advantages in propulsion yet impose control trade-offs, underscoring that trainable adaptation amplifies but does not originate these foundational enablers.[28]Historical Development

Ancient and Pre-Modern Origins

The practice of gymnastics in ancient Greece centered on physical exercises conducted in the gymnasion, facilities dedicated to nude training (gymnos meaning "naked") aimed at cultivating strength, agility, and endurance primarily for military preparedness.[29] These activities, including running, jumping, throwing, and wrestling, were integral to civic education for free male citizens, fostering the kalokagathia ideal of balanced physical and moral excellence, as evidenced by archaeological remains of palaestrae and textual accounts from historians like Pausanias.[30] The pentathlon, introduced at the Olympic Games in 708 BCE, exemplified this approach through five events: the stadion foot race (approximately 192 meters), long jump (with halteres weights), discus throw, javelin throw, and wrestling bout to submission.[31][30] Vase paintings and victory statues, such as those from Olympia, depict competitors in dynamic poses emphasizing stoic endurance and combat utility, underscoring gymnastics' role in hoplite warfare readiness rather than mere spectacle.[31] Roman adoption of Greek gymnastics integrated it into legionary training, prioritizing functional drills like obstacle vaulting and weapon handling over competitive athletics, with exercises designed to enhance soldier mobility and resilience in formation combat.[32][1] While emperors like Nero constructed public gymnasia in the 1st century CE, senatorial opposition often stemmed from cultural aversion to Greek-style nudity, limiting widespread civilian practice; military texts and reliefs, such as Trajan's Column (c. 113 CE), illustrate coordinated physical maneuvers akin to early gymnastics for cohort discipline.[33] Vitruvius, in De Architectura (c. 15 BCE), outlined canonical human proportions—face one-tenth of height, foot one-sixth—drawing from Greek sculptural ideals to inform architectural symmetry, indirectly preserving metrics for assessing physical symmetry in training contexts. In medieval Europe, formalized gymnastics waned amid feudal fragmentation, yielding to militaristic regimens for knights and squires that echoed ancient elements through wrestling, balance drills on horseback, and strength-building via weighted practice weapons, as chronicled in chivalric manuals like Fiore dei Liberi's Fior di Battaglia (c. 1410).[34][35] Tournament simulations and daily labors—hauling armor (up to 30 kg) or mock sieges—served as de facto conditioning, with sparse records indicating vaulting and tumbling for agility in close-quarters combat, though emphasis shifted to armored endurance over aesthetic form.[36] Parallel traditions existed outside Europe, such as mallakhamba in India, a pole-based regimen traced to the 12th century in Maharashtra for augmenting wrestlers' (malla) grip strength and inversion skills, referenced in the 1135 CE Manasollasa treatise as preparatory for combat sports.[37][38] Practitioners performed rope or wooden-pole (khamba) climbs and locks, fostering core stability and limb control verifiable through temple carvings and regional akharas predating colonial records, distinct from ritual dance yet aligned with martial conditioning.[39]19th-Century Revival and Standardization

In early 19th-century Germany, gymnastics experienced a revival led by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, who established the first open-air gymnastic facility, or Turnplatz, at Hasenheide in Berlin in 1811.[40] Jahn, motivated by nationalist sentiments amid Napoleonic occupation, developed the Turnverein system of clubs to foster physical vigor and patriotic unity among youth, introducing apparatus such as parallel bars, the horizontal bar, and rings to simulate military training and build resilience. This approach prioritized collective ideological goals—strengthening German identity against foreign influence—over purely recreational or health-focused exercise, though it drew on empirical observations of physical decline in urbanizing societies; however, the system's emphasis on mass drills often subordinated individual athleticism to state-like regimentation, leading to its suppression by Prussian authorities in 1819 for perceived revolutionary undertones.[40] The Turnverein model spread across Europe, adapting to local contexts while retaining ideological underpinnings. In Sweden, Pehr Henrik Ling founded the Royal Central Institute of Gymnastics in Stockholm in 1813, creating a system divided into pedagogical, medical, military, and aesthetic branches that stressed systematic movements for hygiene, posture correction, and discipline amid rapid industrialization and urbanization.[41] Ling's method, influenced by anatomical studies and Chinese massage techniques he encountered abroad, integrated gymnastics into state education to promote national vitality, yet its rigid, instructor-led formats critiqued for overemphasizing conformity and preventive medicine at the expense of dynamic skill development.[42] In France, similar programs emerged under military reformers like Francisco Amoros, who by the 1820s incorporated gymnastic drills into army training and schools to instill order and physical preparedness, reflecting causal links between exercise routines and societal control in post-Revolutionary Europe.[43] Standardization accelerated in the late 19th century through nascent international organizations, culminating in the founding of the Bureau of the European Gymnastics Federation in Liège, Belgium, in 1881, which evolved into the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG).[2] Early meets, such as those organized by Turnverein networks across German-speaking regions, emphasized codified apparatus routines and team formations over amateur purity, often serving as platforms for national demonstrations that blurred lines between sport and propaganda.[4] These efforts established precedents for uniform rules and equipment, driven by practical needs for comparability in competitions, but state sponsorship frequently infused events with militaristic pageantry, revealing tensions between genuine athletic progress and instrumentalized physical culture.[44]20th-Century Professionalization and Olympic Integration

The Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique (FIG) was founded on July 23, 1881, in Liège, Belgium, by gymnastics federations from Belgium, France, Italy, and Switzerland, establishing the framework for standardized international rules and competitions.[23] Men's artistic gymnastics debuted at the inaugural modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896, with events contested on apparatus including the horizontal bar, parallel bars, pommel horse, rings, and vault, shifting emphasis from general calisthenics toward specialized skills requiring strength, balance, and precision.[6] Women's artistic gymnastics was introduced at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, initially featuring team and individual combined exercises before evolving to include apparatus-specific events like vault, asymmetric bars, and balance beam.[6] This Olympic integration accelerated professionalization, as national federations invested in apparatus training to meet competitive criteria, diverging from 19th-century mass drills and school-based physical education routines.[45] Following World War II, the Soviet Union's Olympic debut at the 1952 Helsinki Games marked a pivotal advancement in training methodologies, with their men's and women's teams securing team gold medals through programs emphasizing flawless execution, amplitude, and difficulty—outcomes directly attributable to state-directed resources enabling year-round, specialized coaching from early ages.[46][47] Soviet dominance persisted across subsequent decades, capturing 37 of 42 possible team titles in artistic gymnastics from 1952 to 1988, facilitated by systematic talent pipelines that screened millions of children annually for biomechanical aptitude and subjected selectees to intensive regimens, contrasting with Western amateur constraints under IOC eligibility rules.[48] These approaches reflected Cold War imperatives, where athletic supremacy served as propaganda for socialist efficiency, with empirical medal tallies underscoring causal advantages from centralized funding over decentralized, part-time Western systems.[49] In the 1970s and 1980s, scoring refinements under the FIG's Code of Points culminated in the first Olympic perfect 10.0 awards at the 1976 Montreal Games, validating decades of incremental difficulty escalations and execution demands that rewarded risk-assessed routines over conservative performances.[50] Gender dynamics evolved amid pushes for parity, with women's programs expanding to mirror men's apparatus variety by the 1950s, yet Eastern Bloc nations maintained disproportionate success—winning over 90% of women's Olympic medals from 1952 to 1988—due to gender-neutral state selection prioritizing physiological potential regardless of ideological Western critiques of intensified female training.[51] This era's innovations, including vault runway extensions and bar height adjustments, further entrenched apparatus specialization, aligning gymnastics with Olympic ideals of measurable excellence while exposing disparities rooted in systemic national investments rather than innate capabilities.Late 20th to 21st-Century Innovations and Global Spread

In 2000, trampoline gymnastics debuted as an Olympic discipline at the Sydney Games, featuring individual men's and women's events and marking the International Gymnastics Federation's (FIG) effort to incorporate dynamic apparatus-based skills into the Olympic program.[52] This addition expanded competitive gymnastics beyond traditional artistic and rhythmic formats, emphasizing height, form, and sequential aerial maneuvers judged on difficulty and execution.[53] A significant rule change occurred in 2006 when the FIG revised the Code of Points for artistic gymnastics, introducing an open-ended scoring system that combined a difficulty score (starting from zero and rewarding complex elements) with an execution score (deducted from 10.0 for errors).[54] This replaced the prior capped "perfect 10" model, aiming to incentivize innovation and higher-risk routines while addressing longstanding criticisms of subjective judging, though it initially sparked debate over inflated scores and reduced emphasis on perfection.[55] The FIG extended similar open-ended elements to other disciplines over subsequent cycles, fostering evolution in routine composition. The FIG further diversified in 2018 by incorporating parkour as a new discipline, complete with judged competitions on obstacle courses emphasizing vaults, flips, and precision landings.[56] However, this move drew criticism from parkour's founding organizations, such as World Freerunning Parkour Federation, who argued it misrepresented the activity's origins in urban free-running and traceur philosophy, potentially diluting its non-competitive, environment-adaptive essence into a sanitized, apparatus-bound format unsuitable for core gymnastics skills.[57] [58] Globalization accelerated in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, with Asia emerging as a powerhouse; China, leveraging state-supported training, dominated the 2008 Beijing Olympics by securing both men's and women's team golds alongside multiple individual titles across apparatus.[59] This shift reflected broader investment in gymnastics infrastructure across the region, contrasting earlier European and North American hegemony. In the United States, the Larry Nassar abuse scandal—exposed in 2016 and culminating in his 2018 life sentence and a $380 million USA Gymnastics settlement with survivors—prompted sweeping reforms in athlete welfare, coaching oversight, and organizational governance.[60] These changes supported resilience, as evidenced by the U.S. women's team earning silver in the 2021 Tokyo team event and individual medals despite high-profile withdrawals.[61] By the mid-2020s, participation surged in non-traditional disciplines; trampoline events at the 2025 World Championships exceeded 250 registered athletes in core categories alone, signaling a boom driven by accessible equipment and youth appeal.[62] The FIG's hosting of the 2025 Artistic Gymnastics World Championships in Jakarta, Indonesia—drawing competitors from over 80 nations to the Indonesia Arena—underscored Southeast Asia's rising role, with events like the all-around finals highlighting diverse global talent amid ongoing code refinements for fairness and spectacle.[63]Governing Organizations

International Federation of Gymnastics (FIG)

The International Federation of Gymnastics (FIG), established on July 23, 1881, in Liège, Belgium, as the Bureau des Fédérations Européennes de Gymnastique, serves as the global governing body for gymnastics and is the oldest international federation associated with an Olympic sport.[23] Initially focused on European nations, it expanded to include non-European members by 1921 and was renamed the Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique in 1922, reflecting its broadened scope.[44] Today, the FIG oversees eight disciplines—Gymnastics for All, artistic gymnastics (men’s and women’s), rhythmic gymnastics, trampoline gymnastics (including double mini-trampoline and tumbling), acrobatic gymnastics, aerobic gymnastics, and parkour—and coordinates over 160 national member federations, a significant growth from its original three affiliates.[23][64] The FIG standardizes competition rules across disciplines, sanctions international events to ensure compliance with technical regulations, and organizes major competitions such as world championships and continental events, promoting uniformity in judging, apparatus specifications, and athlete eligibility. In anti-doping efforts, it aligns with the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) through its Anti-Doping Rules, effective January 1, 2021, which mandate testing, education, and sanctions to preserve sport integrity, including cooperation with national anti-doping organizations.[65] However, enforcement gaps have been evident in areas like age verification, where historical discrepancies in documentation and investigations have drawn critiques for inconsistent application, undermining rule standardization despite established eligibility criteria requiring gymnasts to meet minimum ages (e.g., 16 in the Olympic year for senior artistic events).[66] In recent developments, the FIG Executive Committee, on October 10, 2025, approved updates to the qualification rules for the 2026 Youth Olympic Games in Dakar, Senegal, emphasizing performance-based criteria and international technical official selection to enhance competitive merit, while also revising technical regulations for 2025 to refine event structures across disciplines.[67] These measures aim to address prior limitations in quota systems by prioritizing athletic achievement, though ongoing scrutiny persists regarding the federation's ability to uniformly enforce such standards amid past enforcement challenges.[67]National and Regional Bodies

National governing bodies for gymnastics, recognized by the International Federation of Gymnastics (FIG), manage domestic competitions, athlete development, and funding allocation, with efficacy tied to cultural priorities and resource commitment that causally drive elite performance variances. In the United States, USA Gymnastics implemented reforms post-2018 amid the Larry Nassar abuse scandal, including multiple CEO transitions and enhanced athlete safeguards, while settling victim claims for $380 million; these changes coincided with reclaiming women's artistic team gold at the 2024 Paris Olympics, underscoring resilience despite ongoing litigation burdens.[68][10] Eastern models exemplify higher elite outputs through state-directed rigor: China's Gymnastics Association, backed by centralized funding exceeding billions annually across sports, has propelled national medal totals since 1980 Olympic reentry, though gymnastics yielded only two bronzes in Rio 2016 amid talent pipeline strains.[69][70][71] This contrasts with Western approaches prioritizing broad participation and welfare, as in Britain, where adoption of Eastern-inspired specialization boosted outputs but highlighted tensions with inclusivity norms yielding fewer top-tier results per capita.[72][73] Regional confederations bridge national efforts, such as the European Gymnastics (EUG) with its 50 member federations organizing continental championships and youth events for thousands annually, yet data reveal stark participation gaps—EU-wide weekly physical activity hovers at 44%, but gymnastics engagement varies widely, with Eastern European nations like Romania sustaining medal pipelines via disciplined systems while Western counterparts lag in elite conversion despite higher grassroots numbers.[74][75][76] Funding disparities amplify this: state-heavy models in Asia and former Soviet states correlate with 75% of China's Olympic golds from targeted investments, versus decentralized Western reliance on private sponsorships constraining depth.[77][78]Primary Competitive Disciplines

Artistic Gymnastics

Artistic gymnastics constitutes the foundational competitive discipline within gymnastics, characterized by routines performed on specialized apparatus that demand a synthesis of strength, precision, flexibility, and aerial awareness. Competitions feature separate programs for men and women, with events tailored to physiological variances such as greater male upper-body musculature—resulting from higher testosterone levels—and female advantages in hip flexibility and lower center of gravity, which influence leverage and stability on apparatus.[79][80][81] Men's artistic gymnastics encompasses six apparatus: floor exercise, pommel horse, still rings, vault, parallel bars, and horizontal bar. The floor exercise occurs on a 12m x 12m sprung mat, incorporating tumbling passes and static holds to demonstrate power and control. Pommel horse requires continuous circling and leg swings on a leather-covered apparatus 1.15m high, emphasizing core and leg strength without hand support. Still rings, suspended 2.80m above the floor, demand static holds like iron crosses and dynamic swings, exploiting male grip and shoulder strength for elements unattainable by most females due to biomechanical disparities in upper-body power-to-weight ratios. Vault involves a sprint approach to a springboard and table 1.35m high, culminating in flips and twists. Parallel bars, set 3.50m long and adjustable to 1.75-2.30m apart, feature handstands and releases; horizontal bar, 2.40-2.80m high, focuses on giant swings and dismounts. Routines typically last 30-70 seconds, prioritizing explosive strength over endurance.[79][82][83][81] Women's artistic gymnastics comprises four events: vault, uneven bars, balance beam, and floor exercise. Vault shares the men's format but uses a 1.25m table height to accommodate shorter statures and approach velocities, enabling higher relative amplitudes in saltos. Uneven bars consist of two horizontal bars 2.50m and 1.70m high, spaced 1.20-1.60m apart, for kipping swings and transitions that leverage female flexibility for tighter radii and flight elements. Balance beam, a 10cm-wide, 1.25m-high apparatus 5m long, tests equilibrium through acrobatic series, turns, and leaps, where narrower pelvic structures and enhanced proprioception provide stability advantages over males. Floor exercise mirrors the men's but incorporates music and dance, with routines bounded by a 12m x 12m area emphasizing amplitude and artistry. Event durations range from 30-90 seconds, with beam and floor capped at 90 seconds to sustain intensity without fatigue-induced errors.[80][82][84][81] These gendered event distinctions stem from empirical observations of sex-based biomechanics: males' broader shoulders and higher fast-twitch fiber density in upper extremities favor apparatus requiring sustained tension, such as rings, where leverage from longer arms amplifies torque but demands proportional strength absent in females; conversely, women's events like beam exploit joint hypermobility and compact builds for precision on narrow supports, reducing fall risks through optimized center-of-mass control. Vault height differentials ensure equitable challenge, as male faster run-ups generate greater momentum, necessitating a taller apparatus to normalize post-flight trajectories. All apparatus adhere to FIG norms for dimensions and materials, verified through standardized testing to minimize variability in competitive outcomes.[85][81][19]Rhythmic Gymnastics

Rhythmic gymnastics involves performances on a 13m x 13m sprung floor to music, where competitors manipulate apparatus through leaps, balances, pivots, and body waves, integrating elements of dance and flexibility.[86] Individual routines last 75 seconds and feature one of five apparatus—rope, hoop, ball, clubs, or ribbon—while group routines of five gymnasts last 90 seconds using the same apparatus throughout.[87] The discipline debuted as an Olympic event in 1984 for women in the individual all-around, with group competition added in 1996, and has remained exclusive to female participants at that level. Scoring follows the FIG Code of Points, combining Difficulty (D-score for body groups, apparatus elements, and risks), Execution (E-score starting from 10.0 minus deductions for form and technique), and Artistry (A-score evaluating choreography, music interpretation, and manner of execution), with final scores averaged across panels. Emphasis lies on fluid manipulation and harmonious movement rather than explosive power, favoring attributes like amplitude and control in tosses, rotations, and catches.[85] Competitions require FIG-certified apparatus meeting specifications for size, weight, and material to ensure safety and consistency.[85] Empirical data highlight stark gender disparities, with participation overwhelmingly female; for instance, skill achievement studies show women outperforming men in flexibility-dependent elements, while surveys of over 200 practitioners indicate majority female involvement and limited male entry due to cultural and physiological factors.[88] A 2009 international survey of 299 rhythmic gymnastics stakeholders found 76.5% support for male inclusion, yet actual male participation remains marginal, confined to non-FIG events in countries like Japan.[89] Men's rhythmic gymnastics, using similar apparatus and routines, emerged in the 2010s but lacks formal FIG Olympic recognition, reflecting lower institutional priority compared to women's programs.[90]Trampoline Gymnastics and Tumbling