Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Konya

View on WikipediaKonya[a] is a major city in central Turkey, on the southwestern edge of the Central Anatolian Plateau, and is the capital of Konya Province. During antiquity and into Seljuk times it was known as Iconium. In 19th-century accounts of the city in English its name is usually spelt Konia or Koniah. In the late medieval period, Konya was the capital of the Seljuk Turks' Sultanate of Rum, from where the sultans ruled over Anatolia.

Key Information

As of 2024, the population of the Metropolitan Province was 2 330 024 of whom 1 433 861 live in the three urban districts (Karatay, Selcuklu, Meram), making it the sixth most populous city in Turkey, and second most populous of the Central Anatolia Region, after Ankara. City has Konya is served by TCDD high-speed train (YHT) services from Istanbul, Ankara and Karaman. The local airport (Konya Havalimanı, KYA) is served by frequent flights from Istanbul whereas flights to and from İzmir are offered few times a week.

Name

[edit]Konya is believed to correspond to the Late Bronze Age toponym Ikkuwaniya known from Hittite records.[3][4] This placename is regarded as Luwian in origin.[5] During classical antiquity and the medieval period it was known as Ἰκόνιον (Ikónion) in Greek and as Iconium in Latin.[6][7]

A folk etymology holds that the name Ikónion was derived from εἰκών ('icon'), referring to an ancient Greek legend according to which the hero Perseus vanquished the native population with an image of the "Gorgon Medusa's head" before founding the city.[8]

Konya was known as Dârülmülk to the Rum Seljuks.[9]

History

[edit]Overview

[edit]The Konya region has been inhabited since the third millennium BC and fell at different times under the rule of the Hittites, the Phrygians, the Greeks, the Persians and the Romans. In the 11th century the Seljuk Turks conquered the area and began ruling over its Rûm (Byzantine Greek) inhabitants, making Konya the capital of their new Sultanate of Rum. Under the Seljuks, the city reached the height of its wealth and influence. Following their demise, Konya came under the rule of the Karamanids, before being taken over by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century. After the Turkish War of Independence the city became part of the modern Republic of Turkey.

Ancient history

[edit]

Excavations have shown that the region was inhabited during the Late Copper Age, around 3000 BC.[8]

The Phrygians established their kingdom in central Anatolia in the eighth century BC and Xenophon describes Iconium (as the city was originally called) as the last city of Phrygia. The region was overwhelmed by Cimmerian invaders c. 690 BC. Later it formed part of the Persian Empire, until Darius III was defeated by Alexander the Great in 333 BC. Alexander's empire broke up shortly after his death and the town came under the rule of Seleucus I Nicator.

During the Hellenistic period the town was ruled by the kings of Pergamon. As Attalus III, the last king of Pergamon, was about to die without an heir, he bequeathed his kingdom to the Roman Republic. Once incorporated into the Roman Empire, under emperor Claudius, the city's name was changed to Claudiconium. During the reign of emperor Hadrianus it was known as Colonia Aelia Hadriana.

Saint Paul and Iconium

[edit]Paul and Silas probably visited Konya during Paul's Second Missionary Journey in about AD 50,[10][11] as well as near the beginning of his Third Missionary Journey several years later.[12]

According to the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla, Iconium was also the birthplace of Saint Thecla, who saved the city from attack by the Isaurians in 354.[13]

Byzantine Era

[edit]Under the Byzantine Empire, the city became the seat of a bishop, and in c. 370 was raised to the status of a metropolitan see for Lycaonia, with Saint Amphilochius as the first metropolitan bishop.[13] In the 7th century it became part of the Anatolic Theme and was, together with the nearby (Caballa) Kaballah Fortress (Turkish: Gevale Kalesi) (location) a frequent target of Arab attacks during the Arab–Byzantine wars in the eighth to tenth century,[13] being captured by Arabs in 723–724.[14] The rebellious general Andronikos Doukas used the Kaballah fortress as his base in 905–906.[15] During the tenth or eleventh century the church of Saint Amphilochius was constructed inside the citadel of Kaballa, housing the tomb of the saint which the Turks later believed to be the tomb of Plato, renaming the church to Eflâtun Mescidi (mosque of Plato).[16] The monastery of Saint Chariton, another local from Iconium, was located a few miles away in Sylata.[17]

The Seljuk Turks first raided the area in 1069, but a period of chaos overwhelmed Anatolia after the Seljuk victory in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and the Norman mercenary leader Roussel de Bailleul rose in revolt at Iconium. The city was finally conquered by the Seljuks in 1084.[13]

Seljuk and Karamanid eras

[edit]

Iconium became the second capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum after the fall of Nicaea until 1243.[18] It was briefly occupied by the army of the First Crusade (August 1097) and Frederick Barbarossa (May 18, 1190) after the Battle of Iconium (1190). The area was reoccupied by the Turks after the Crusaders left.

Konya reached the height of its wealth and influence in the second half of the 12th century when the Seljuk sultans of Rum also subdued the Anatolian beyliks to their east, especially that of the Danishmends, thus establishing their rule over virtually all of eastern Anatolia,. They also acquired several port towns along the Mediterranean (including Alanya) and the Black Sea (including Sinop) and even gained a brief foothold in Sudak, Crimea. This golden age lasted until the first decades of the 13th century.[citation needed]

Many Persians and Persianised Turks from Persia and Central Asia migrated to Anatolian cities either to flee the invading Mongols or to benefit from the opportunities for educated Muslims in a newly established kingdom.[19]

Following the fall of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate in 1307, Konya became the capital of the Eshrefids, a Turkish beylik, which lasted until 1322 when the city was captured by the neighbouring Beylik of Karamanoğlu. In 1420, the Beylik of Karamanoğlu fell to the Ottoman Empire and, in 1453, Konya was made the provincial capital of the Karaman Eyalet.

Ottoman Empire

[edit]Under Ottoman rule, Konya was administered by the Sultan's sons (Şehzade), starting with Şehzade Mustafa and Şehzade Cem (the sons of Sultan Mehmed II), and continuing with the future Sultan Selim II.

Between 1483 and 1864, Konya was the administrative capital of the Karaman Eyalet. During the reforming Tanzimat period, it became the seat of the larger Vilayet of Konya which replaced the Karaman Eyalet, as part of the new vilayet system introduced in 1864.

In 1832 Anatolia was invaded by Mehmed Ali Paşa of Kavala whose son, İbrahim Paşa, occupied Konya. Although he was driven out with the help of the European powers, Konya went into a decline after this, as described by the British traveller, William Hamilton, who visited in 1837 and found a scene 'of destruction and decay', as he recorded in his Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia, published in 1842.[20]

Konya's textile and mining industries flourished under the Ottomans.[21]

Turkish Republic

[edit]

During the Turkish War of Independence (1919–1922) Konya was a major air base. In 1922, the air force, renamed as the Inspectorate of Air Forces,[b] was headquartered in Konya.[22][23] Before 1923, 4,000 Orthodox, Turkish-speaking and Greek-speaking Christians lived there. The Greek community numbered approximately 2,500 people who maintained, at their own expense, a church, a boys' school and a girls' school. In 1923 during the population exchange between Greece and Turkey, the Greeks of the nearby village of Sille were forced to leave as refugees and resettle in Greece.[24]

Government

[edit]

The first local administration in Konya was founded in 1830 and converted into a municipality in 1876.[c] In March 1989, the municipality became a Metropolitan Municipality. As of that date, Konya had three central district municipalities (Meram, Selçuklu, Karatay) and a Metropolitan Municipality.

Economy

[edit]Home to several industrial parks. The city ranks among the Anatolian Tigers.[25][26][27][28] In 2012 exports from Konya reached 130 countries.[28] A number of Turkish industrial conglomerates, such as Bera (ex Kombassan) Holding, have their headquarters in Konya.[29]

While agriculture-based industries play a role, the city's economy has evolved into a center for the manufacturing of components for the automotive industry; machinery manufacturing; agricultural tools; casting; plastic paints and chemicals; construction materials; paper and packaging; processed foods; textiles; and leather.[28]

Turkey's largest solar farm is located 20 miles east of the city, near Karapınar.[30]

Geography

[edit]Konya sits in the center of the largest province, in the largest plain (Konya Plain), and is the seventh most heavily populated city in Turkey.[31]

The city is in the southern part of the Central Anatolia Region with the southernmost side of the province hemmed in by the Taurus Mountains.

Climate

[edit]Konya has a cold semi-arid climate (BSk) under the Köppen classification[32] and a temperate continental (Dc) climate under the Trewartha classification.

Summer daytime temperatures average 30 °C (86 °F), although summer nights are cool. The highest temperature recorded in Konya was 40.9 °C (106 °F) on 14 August 2023, closely beating the former record of 40.6 °C (105 °F) on 30 July 2000. Winters average −4.2 °C (24 °F), and the lowest temperature recorded was −26.5 °C (−16 °F) on 6 February 1972. Precipitation levels are low and happen mainly in winter (mostly as snow), spring and autumn.

| Climate data for Konya (1991–2020, extremes 1929–2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.3 (66.7) |

23.8 (74.8) |

28.9 (84.0) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.7 (98.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

40.9 (105.6) |

38.8 (101.8) |

32.3 (90.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

21.8 (71.2) |

40.9 (105.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

12.7 (54.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

1.3 (34.3) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.2 (−18.8) |

−26.5 (−15.7) |

−16.4 (2.5) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

6.0 (42.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−28.2 (−18.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 35.9 (1.41) |

23.1 (0.91) |

27.4 (1.08) |

34.2 (1.35) |

38.2 (1.50) |

27.8 (1.09) |

6.5 (0.26) |

6.5 (0.26) |

15.9 (0.63) |

29.7 (1.17) |

34.5 (1.36) |

45.6 (1.80) |

325.3 (12.81) |

| Average precipitation days | 10.53 | 8.97 | 9.80 | 10.83 | 12.47 | 8.10 | 3.00 | 2.63 | 4.40 | 7.27 | 7.13 | 10.10 | 95.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79.8 | 73.3 | 63.4 | 58.7 | 56.1 | 47.5 | 38.9 | 39.4 | 44.2 | 57.6 | 70.1 | 79.9 | 59.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 105.4 | 138.4 | 195.3 | 216.0 | 269.7 | 309.0 | 344.1 | 334.8 | 291.0 | 235.6 | 159.0 | 102.3 | 2,700.6 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 3.4 | 4.9 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 10.3 | 11.1 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 7.6 | 5.3 | 3.3 | 7.4 |

| Source 1: Turkish State Meteorological Service[33] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity)[34] | |||||||||||||

Culture

[edit]

Konya has a reputation for being one of the more religiously conservative metropolitan centres in Turkey.[35]

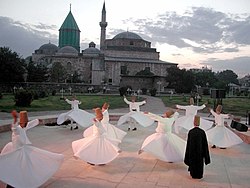

Konya was the final home of Rumi (Mevlana), whose turquoise-domed tomb in the city is its primary tourist attraction. In 1273, Rumi's followers established the Mevlevi Sufi order of Islam and became known as the Whirling Dervishes.

Every Saturday, there are Whirling Dervish performances (semas) at the Mevlana Cultural Centre. Unlike some of the commercial performances staged in cities like Istanbul, these are genuinely spiritual sessions.

Expensive, richly patterned Konya carpets were exported to Europe during the Renaissance[36] and were draped over furniture to show off the wealth and status of their owners. They often crop up in contemporary oil paintings as symbols of the wealth of the painter's clients.[37]

Attractions

[edit]

- Mevlâna Museum

- Alaaddin Mosque

- Ince Minaret Medrese—Museum[38]

- Karatay Medrese—Museum[38]

- Sırçalı Medrese

- Sahib-i Ata Mosque complex

- Konya Archaeological and Ethnography Museum[39]

- Koyunoğlu Museum

- Atatürk House Museum[38]

- Mevlana Cultural Centre[40]

- Mevlana Festival

- Selimiye Mosque

- Aziziye Mosque

- Konya Science Centre (Turkish: Konya Bilim Merkezi)

- Konya Tropical Butterfly Garden

- Meram, suburb with popular waterside picnicking facilities

- Sille, 8 kilometres (5.0 miles) northwest from Mevlana Museum: antique village, mosques, churches, cave churches and catacombs

- Çatalhöyük

Food

[edit]One of the city's best-known dishes, etli ekmek consists of slices of lamb served on flaps of soft white bread.[41] Konya is also known for unfeasibly long pides (Turkish pizzas) intended to be shared, and tirit, a traditional rice dish made from meat and assorted vegetables.

Konya is also known for its sweets, including cezerye, an old Turkish sweet made from carrots, and pişmaniye, which is similar to American cotton candy.

Sports

[edit]

The city's football team Konyaspor is part of the Turkish Professional Football League. On May 31, 2017, they won their first national trophy, beating İstanbul Başakşehir to the Türkiye Kupası in a penalty shootout. They repeated this success on August 6, 2017, defeating Beşiktaş to win the Türkiye Süper Kupası (Turkish Super Bowl).

Konya Metropolitan Stadium (Konya Büyükşehir Stadyumu) is in the Selçuklu neighbourhood and can seat up to 42,000 spectators.

The city hosted the 2022 Islamic Solidarity Games in August 2022.

Education

[edit]Founded in 1975, Selçuk University had the largest number of students (76,080) of any public university in Turkey during the 2008–09 academic year.[42][better source needed] The other public university, Necmettin Erbakan University, was established in Konya in 2010.[43][better source needed]

Private colleges in Konya include the KTO Karatay University.[44][better source needed]

Konya hosts the Anatolian Eagle Tactical Training Centre for training NATO Allies and friendly Air Forces.[45][better source needed]

Transportation

[edit]

Intercity buses

[edit]The central bus station has connections to a range of destinations, including Istanbul, Ankara and İzmir. It is connected to the town centre by a tram.

Inner-city public transport

[edit]The Konya Tram network is 41 km (25 mi) long and has two lines with 41 stations. Opened in 1992, it was expanded in 1996 and 2015. The Konya Tram uses Škoda 28 T vehicles.[46]

Work began on building a Konya Metro in 2020 and is expected to be completed in 2024 and will have 22 stations.[47]

Konya also has an extensive inner-city bus network.

Railway

[edit]Konya is connected to Ankara, Eskişehir, Istanbul and Karaman via the high-speed railway services of the Turkish State Railways.[48][49]

Airport and airbase

[edit]Konya Airport (KYA) is a public airport but also a military airbase used by NATO. The Third Air Wing[d] of the 1st Air Force Command[e] is based at the Konya Air Base. The wing controls the four Boeing 737 AEW&C Peace Eagle aircraft of the Turkish Air Force.[50][51]

Notable people

[edit]- Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi, also called Mawlana or Mevlana, the inspiration behind the Sufi Mevlevi order (known for the Whirling Dervishes and Masnavi). He died and was buried in Konya in 1273.[52]

- Amphilochius of Iconium, fourth century Christian bishop.[53]

- Nevin Halıcı, writer, cultural anthropologist and lecturer

- Prokopios Lazaridis, Greek Orthodox metropolitan bishop of the Metropolis of Iconium[54][55]

- Murat Yıldırım (actor), actor and presenter

- Hilmi Şenalp (1957-), architect.[56]

- Kemal Şahin, Turkish–German entrepreneur

- Metin Şahin, taekwondo practitioner

- Saliha Scheinhardt, writer and lecturer.

- Husam al-Din Chalabi, muslim Sufi

- İsmail Güzel, wrestler

- Nur Banu Özpak, sport shooter

- Hazal Kaya, actress

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Konya is twinned with:

See also

[edit]- Mevlâna Museum

- Anatolian Tigers

- Konya Carpets and Rugs

- Theodosius the Cenobiarch (c. 423–529 AD), monk, abbot, and saint born in Iconium; a founder and organiser of the cenobitic way of monastic life

- Thecla or Tecla, first-century virgin saint of the early Christian Church, born in Iconium

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Turkey: Administrative Division (Provinces and Districts) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map".

- ^ City Mayor: Ugur Ibrahim Altay(AKP) Elected in 2024 "Statistics by Theme > National Accounts > Regional Accounts". www.turkstat.gov.tr. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ Forlanini, Massimo (2017). "South Central: The Lower Land and Tarḫuntašša". In Weeden, Mark; Ullmann, Lee (eds.). Hittite Landscape and Geography. Brill. p. 244. doi:10.1163/9789004349391_022. ISBN 978-90-04-34939-1.

- ^ Bryce, Trevor (2006). The Trojans and their neighbours. London: Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 9780415349550.

- ^ Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (2017). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. de Gruyter. p. 239. ISBN 978-3-11-026128-8.

- ^ Bryce, Trevor (2006). The Trojans and their neighbours. London: Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 9780415349550.

- ^ Klein, Jared; Joseph, Brian; Fritz, Matthias (2017). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics. de Gruyter. p. 239. ISBN 978-3-11-026128-8.

- ^ a b "Konya". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "KONYA İç Anadolu bölgesinde şehir ve bu şehrin merkez olduğu il". TDV Encyclopedia of Islam (44+2 vols.) (in Turkish). Istanbul: Turkiye Diyanet Foundation, Centre for Islamic Studies. 1988–2016.

- ^ Ramsay, William Mitchell (1908). The Cities of St. Paul. A.C. Armstrong. pp. 315–384.

- ^ Bruce, Frederick Fyvie (1977). Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free. Eerdmans. p. 475. ISBN 978-0-8028-3501-7.

- ^ Bruce, Frederick Fyvie (1977). Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free. Eerdmans. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-8028-3501-7.

- ^ a b c d Foss, Clive (1991). "Ikonion". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. London and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 985. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^ Whittow, Mark (1996). The Making of Byzantium, 600-1025. University of California Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780520204966. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ Heald Jenkins, Romilly James (1987). Byzantium The Imperial Centuries, AD 610–1071. University of Toronto Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780802066671. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- ^ Tekinalp, V. Macit (2009). "Palace churches of the Anatolian Seljuks: tolerance or necessity?". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 332 (2): 148–167. doi:10.1179/174962509X417645.

- ^ Breytenbach, Cilliers; Zimmermann, Christiane (2017). Early Christianity in Lycaonia and Adjacent Areas From Paul to Amphilochius of Iconium. Brill. ISBN 9789004352520.

- ^ Hiro, Dilip (2011). Inside Central Asia. Gerald Duckworth & Company. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-7156-4038-8.

- ^ Mango, Andrew (1972). Discovering Turkey. Hastings House. p. 61. ISBN 0-8038-7111-2. OCLC 309327.

- ^ Freely, John (1998). The Western Interior of Turkey (1st ed.). Istanbul: SEV. pp. 235–36. ISBN 9758176226.

- ^ Chen, Yuan Julian (2021-10-11). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History. 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. S2CID 244587800.

- ^ "Bir Hata Oluştu". Hvkk.tsk.tr. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Kocatürk, Utkan (1983). Atatürk ve Türkiye Cumhuriyeti tarihi kronolojisi, 1918–1938 (in Turkish). Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. p. 634.

- ^ "IFMSA Exchange Portal". Exchange.ifmsa.org. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ "Financial Times: Reports — Anatolian tigers: Regions prove plentiful". Ft.com. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ root. "Anatolian Tigers". Investopedia. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Zaman: Anatolian tigers conquering the world". Archived from the original on 2013-08-21. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ^ a b c "General Overview Of The Konya Economy". En.kto.org.tr. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Anasayfa | Bera Holding". beraholding.com.tr. Retrieved 2022-07-21.

- ^ "The World's Largest Solar Power Plant in Konya". TR Dergisi. 2017-05-15. Retrieved 2022-07-21.

- ^ "Turkey: Provinces & Major Cities – Statistics & Maps on City Population". Archived from the original on 2017-01-14. Retrieved 2013-12-31.

- ^ "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences Discussions. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ "Resmi İstatistikler: İllerimize Ait Mevism Normalleri (1991–2020)" (in Turkish). Turkish State Meteorological Service. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Konya" (CSV). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "'Islam problem' baffles Turkey". BBC News. 2004-12-03. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ^ Campbell, Gordon (2006). "Carpet II: History". The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-19-518948-3.

- ^ "Carpets of the Ottoman Period". Old Turkish Carpets. 2019-06-19. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ^ a b c "Konya Museums and Ruins". www.ktb.gov.tr.

- ^ McLean, B. Hudson (2018). Greek and Latin Inscriptions in the Konya Archaeological Museum. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara. ISBN 978-1-898249-14-6. Retrieved 7 August 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Mevlâna Culture Centre | Konya, Turkey | Entertainment - Lonely Planet".

- ^ "Konya Büyükşehir Belediyesi". Konya.bel.tr (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ^ "Small Ruminant Congress". kucukbas2014.com. 2014-10-18. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ^ "Konya Necmettin Erbakan Üniversitesi". Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "KTO Karatay Üniversitesi". Karatay.edu.tr. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ^ Official Web Site

- ^ "Škoda Transportation wins Konya tram contract". Railway Gazette. 2013-03-04. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ^ Uysal, Onur (2020-10-01). "Last status of metro and tram projects of Turkey". Rail Turkey En. Retrieved 2022-07-22.

- ^ "Opening of Ankara – Konya fast line completes strategic link". Railway Gazette. 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- ^ "Invensys commissions ERTMS solution on Turkish High Speed Line". European Railway Review. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Mehmet Kayhan YILDIZ- Hasan BÖLÜKBAŞ- Serdar ÖZGÜR- Tolga YANIK- Hasan DÖNMEZ/ KONYA,(DHA) (21 February 2014). "TSK yeni yıldızı Barış Kartalı'na kavuştu". HÜRRİYET – TÜRKİYE'NİN AÇILIŞ SAYFASI. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Turkey takes delivery of military aircraft". TodaysZaman. Archived from the original on February 22, 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 106, 309. ISBN 978-0-330-41879-9.

- ^ Thonemann, Peter (2011-05-04). "Amphilochius of Iconium and Lycaonian Asceticism". Journal of Roman Studies. 101: 185–205. doi:10.1017/s0075435811000037. ISSN 0075-4358. S2CID 162127197.

- ^ Savramis, Demosthenes (1968). Die soziale Stellung des Priesters in Griechenland [Social position of the priest in Greece] (in German). E. J. Brill.

- ^ Kiminas, Demetrius (2009). The ecumenical patriarchate : a history of its metropolitanates with annotated hierarch catalogs. San Bernardino, CA: Borgo Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-4344-5876-6.

- ^ Rizvi, Kishwar (2015). The Transnational Mosque: Architecture and Historical Memory in the Contemporary Middle East. UNC Press Books. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4696-2117-3. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "Rumi Remembered in Birthplace of Shams". Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ Kyoto İle Kardeş Şehir Protokolü İmzalandı, Heyet Japon Parkı'nı Gezdi Archived 2014-10-16 at the Wayback Machine, Konya Büyükşehir Belediyesi (2010)

- ^ "Turkish FM's speech to Kirkuk's Turkmen community". ekurd.net. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "UNPO: Iraqi Turkmen: Turkey Promises Protection Of Turkmen". unpo.org. 2 November 2009. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

General

- "About Konya/ Geography and Transportation". Konya Sanayi Odasi. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- Gould, Kevin (9 April 2010). "Konya, In a Whirl of its Own". The Guardian. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- "7 Good Eats in Konya". My Traveling Joys. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]Published in the 19th century

- "Konia". Handbook for Travellers in Turkey (3rd ed.). London: J. Murray. 1854. OCLC 2145740.

- Clément Huart (1897). Konia, la ville des derviches tourneurs (in French). Paris: Leroux. ISBN 9780524077849.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

Published in the 20th century

- Hogarth, David George (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). p. 893.

- E. Broadrup (1995). "Konya/Catal Huyuk". International Dictionary of Historic Places. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn.

Published in the 21st century

- C. Edmund Bosworth, ed. (2007). "Konya". Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- "Konya". Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2009.

External links

[edit] Konya travel guide from Wikivoyage

Konya travel guide from Wikivoyage- Britannica.com: Konya

- More information about Konya Archived 2017-12-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Emporis: Database of highrises and other structures in Konya

- Detailed Pictures of Mevlana Museum

- Pictures of the city, including Mevlana Museum and several Seljuk buildings

- 600 Pictures of the city and sights

- Extensive collection of pictures of the Mevlana museum in Konya

- Ramsay, William Mitchell (1908). The Cities of St. Paul. A.C. Armstrong. pp. 315–384.

- Konya Hava Durumu

- Konya Hava Durumu 15 günlük

- ArchNet.org. "Konya". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- "Konya". Islamic Cultural Heritage Database. Istanbul: Organization of Islamic Cooperation, Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013.

Konya

View on GrokipediaKonya is a city in the Central Anatolian Plateau of Turkey, serving as the capital of Konya Province, the country's largest province by land area. As of 2024, the metropolitan population of Konya is 2,330,024, ranking it as Turkey's sixth-most populous city.[1] The city spans a vast plain conducive to agriculture and has developed into a hub of small and medium-sized enterprises, with over 50,000 such firms driving local manufacturing and exports.[2] Historically, Konya emerged as a pivotal center during the Seljuk era, functioning as the capital of the Sultanate of Rum from the 12th to the 13th centuries, a period marked by architectural and cultural advancements in Anatolia.[3][4] This legacy is evident in surviving monuments like madrasas and mosques that exemplify Seljuk stonework and tile decoration. Konya gained enduring spiritual prominence as the adopted home of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī (1207–1273), the Persian Sufi mystic and poet whose family settled there amid Mongol invasions; his mausoleum remains a focal point for devotees of his teachings on ecstatic union with the divine.[5] Rūmī's influence birthed the Mevlevi order, whose ritual whirling dances symbolize spiritual ascent and continue to define Konya's cultural identity.[6] In the modern era, Konya sustains its economic vitality through agriculture, earning the moniker "granary of Turkey" as the leading producer of wheat, barley, sugar beets, and other staples like flour, sugar, and milk.[2] The province's agro-industrial base supports machinery manufacturing, particularly agricultural equipment, where it holds dominant national shares, alongside exports reaching over 190 countries and generating a trade surplus.[2] Despite its conservative social fabric rooted in Anatolian traditions, Konya exemplifies Turkey's blend of historical depth, religious heritage, and pragmatic economic growth.

Etymology

Historical names and derivations

The ancient name of Konya was Iconium (Greek: Ikónion, Ἰκόνιον), attested in classical sources as a city in Lycaonia, Asia Minor. This designation persisted from Hellenistic times through the Roman era, during which the city was also known as Colonia Aelia Hadriana following Emperor Hadrian's reign in the 2nd century CE.[7] Under Emperor Claudius in the 1st century CE, it briefly appeared as Claudiconium in some records.[8] The etymology traces to a pre-Greek substrate, specifically the Luwian form Ikkuwaniya, adapted into Ancient Greek as Ikónion.[9] A folk etymology, rooted in Greek legend, derives Ikónion from eikón (εἰκών, "image" or "icon"), associating the name with Perseus slaying Medusa and placing her head (an "image" of the Gorgon) on the site, though this lacks linguistic substantiation and reflects mythological rationalization rather than historical philology.[10] Byzantine sources rendered it as Tokonion, evolving into medieval forms such as Icconium, Ycconium, Conium, Stancona, Conia, Cogne, Cogna, Konien, and Konia in Latin and European texts.[8] The modern Turkish Konya emerged from these phonetic shifts, solidified after the Seljuk conquest in the 11th century, reflecting Turkic adaptation of the Byzantine pronunciation without altering the core stem.[11]History

Prehistoric and ancient Iconium

Archaeological investigations at the site of Iconium reveal evidence of continuous human occupation beginning in the third millennium BCE, during the Early Bronze Age.[12] Excavations indicate settlement layers from this period, predating more extensive urban development. Further traces from the Late Chalcolithic era, around 3000 BCE, suggest proto-urban activity in the broader Konya plain, though distinct to the Iconium mound itself.[13] During the second millennium BCE, the region came under Hittite imperial control, likely as part of a Luwian-influenced periphery. Hittite texts may reference the locale as Ikkuwaniya, attesting to administrative or strategic importance amid Bronze Age Anatolian networks.[12] Post-Hittite collapse around 1200 BCE, Phrygian migrants from western Anatolia established dominance, transforming Iconium into a frontier settlement marking Phrygia's southeastern extent toward the Lycaonian plateau. Phrygian cultural markers, including linguistic persistence evidenced by inscriptions, endured locally into the early Common Era.[14] By the sixth century BCE, Iconium integrated into the Achaemenid Persian Empire as part of the satrapy of Cappadocia or Greater Phrygia, serving as a regional hub. Conquest by Alexander the Great in 333 BCE initiated Hellenistic rule, followed by Seleucid oversight until Pergamon's influence in the second century BCE. Roman expansion incorporated Iconium into Galatia by 25 BCE, elevating its status amid provincial reorganizations.[12] The city's strategic position facilitated trade and military transit, with early coinage and fortifications reflecting growing autonomy under local dynasts.[15]Roman and Byzantine periods

Iconium, the ancient name of Konya, was situated in the region of Lycaonia in Asia Minor and served as its principal city during the Roman period. Incorporated into the Roman province of Galatia in 25 BC, the city benefited from its position on major trade routes connecting Ephesus to Syria.[16] Under Emperor Claudius (r. 41–54 AD), Iconium was elevated to the status of a Roman colony, known as Claudiconium, granting it self-governing privileges and Latin rights to its inhabitants.[16] [17] This status fostered economic prosperity, evidenced by archaeological finds such as intricately carved sarcophagi in the Konya Archaeological Museum, reflecting Roman cultural and artistic influences. Early Christianity took root in Iconium during the mid-1st century AD, with the Apostle Paul and Barnabas preaching there around 47 AD, establishing one of the earliest Christian communities in Asia Minor despite local opposition.[14] The city's Christian significance grew, hosting a synod circa 235 AD that ruled baptisms performed by heretics invalid, a decision aligning with contemporaneous North African councils and underscoring Iconium's role in early doctrinal debates.[16] By the late 3rd century, Iconium had become an episcopal see, with fortifications likely constructed around this time to defend against invasions, laying the groundwork for its enduring urban structure.[18] In the Byzantine era, Iconium continued as a key administrative and ecclesiastical center, functioning as the capital of the province of Lycaonia.[19] The city maintained its metropolitan status within the Byzantine church hierarchy, flourishing amid the empire's eastern Roman continuity after the 5th century.[16] It withstood pressures from Arab incursions in the 7th–8th centuries and later Seljuk threats, as seen in the failed siege of 1069 AD, preserving its Byzantine character until the Turkish conquests. Archaeological evidence, including museum-held artifacts, attests to sustained Roman-Byzantine cultural layers, with the city's strategic plateau location aiding defense and trade.[20]Seljuk Sultanate as capital

The Sultanate of Rum, founded by Suleiman ibn Qutalmish in 1077 following the Seljuk victory at Manzikert in 1071, initially established its capital at Nicaea before transferring it to Konya in 1097 after the city's loss to the First Crusade.[21][22] Konya then served as the primary political, administrative, and cultural center of the sultanate until its effective end in 1308 with the murder of the last sultan, Mesud II.[23] As capital, the city hosted the royal court and became a focal point for Turco-Persian governance, blending nomadic Turkish traditions with settled Islamic administration under Sunni orthodoxy.[24] During the reigns of key sultans such as Kilij Arslan II (1156–1192), who consolidated power after internal strife, and Alaeddin Kayqubad I (1220–1237), who oversaw a golden age of expansion and prosperity, Konya emerged as a thriving metropolis.[25] The sultanate under these rulers controlled central Anatolia, fostering economic growth through control of Silk Road trade routes passing through the city, which supported artisanal production, agriculture in the surrounding plains, and international commerce.[24] Kayqubad I's era saw military successes, including the conquest of Sinop in 1214 and Alanya in 1227, enhancing Konya's strategic importance and wealth, with the population likely exceeding 100,000 by the 13th century amid urban development.[23] Konya flourished as a center of learning and architecture, exemplified by monumental constructions like the Alaeddin Mosque, completed in 1220 on the citadel hill as the sultan's principal congregational mosque, featuring a hypostyle plan with six domes and intricate stone carvings.[26] Other key structures included the Karatay Medrese (built 1251) for theological education and the Ince Minareli Medrese (1260–1265), a mausoleum-madrasa complex showcasing turquoise-tiled minarets and geometric ornamentation typical of Anatolian Seljuk style.[27] The period also witnessed cultural patronage, including the settlement of Persian scholars and Sufis; Jalal ad-Din Rumi arrived in Konya around 1228 and established the Mevlevi order, contributing to the city's spiritual legacy under Seljuk tolerance.[28] However, the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 resulted in Mongol dominance, reducing the sultanate to a vassal state under Ilkhanate oversight, with Konya enduring tribute payments and periodic raids while remaining the nominal capital amid rising factionalism and beylik fragmentation.[23] Internal conflicts and Mongol interference eroded central authority, culminating in the sultanate's collapse by 1308, after which Konya transitioned to Karamanid control.[6]Karamanid and Ottoman eras

Following the fragmentation of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate in the late 13th century, Konya entered the domain of the Karamanid Beylik around 1277, when Mehmet Bey, son of the beylik's founder Karaman Bey, seized the city from weakened Seljuk remnants under Mongol influence.[6] The Karamanids, a Turkmen dynasty originating from the Salur tribe of Oghuz Turks, established their rule over central Anatolia, with Konya serving as a key stronghold despite intermittent losses to Ilkhanid forces and rival beyliks; they recaptured it multiple times in the early 14th century, using it as a base for expansion toward the Mediterranean coast from Antalya to Silifke.[29] Under rulers like Alâeddin Ali Bey (r. 1361–1397), the beylik promoted Turkish as the administrative and literary language—famously decreed by Mehmet Bey in the 1270s to supplant Persian and Arabic in official use—and positioned itself as heir to Seljuk legitimacy, fostering cultural patronage amid power struggles.[30] The Karamanids' rivalry with the Ottoman beylik intensified from the late 14th century, marked by battles such as the Ottoman victory near Konya in 1386 under Murad I, though Bayezid I's temporary annexation in 1397–1398 was reversed by Timur's invasion in 1402, restoring Karamanid autonomy.[30] Final Ottoman conquest came in 1468, when Mehmed II subdued the principality after defeating its forces, razing the fortress of Gevele, and fortifying Konya to secure central Anatolia up to the Euphrates; this ended Karamanid independence, with surviving princes exiled or integrated into Ottoman service.[30] [31] Under Ottoman administration, Konya became the capital of the Karaman Eyalet from 1483 to 1864, encompassing sanjaks like Niğde, Kayseri, and Akşehir, with a reported area of 30,463 square miles by the 19th century; it functioned as a provincial hub governed initially by Ottoman princes (şehzades) in the sanjak system, emphasizing timar land grants to stabilize rule over former Karamanid territories.[13] [32] The city experienced economic stagnation relative to its Seljuk-era prosperity, relying on agriculture and trade in grains and wool, though it hosted Mevlevi Sufi orders tied to Rumi's legacy.[10] A notable disruption occurred in the 1832 Battle of Konya, where Egyptian forces under Ibrahim Pasha decisively defeated an Ottoman army of 30,000–50,000, advancing Ottoman decline and prompting European intervention to halt Egyptian expansion.[33] Tanzimat reforms in the mid-19th century reorganized the eyalet, but sustained revival awaited the 1896 Istanbul-Baghdad railway, which boosted connectivity and commerce.[10]Republican era and modernization

The establishment of the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923 marked Konya's transition from Ottoman provincial status to integration within the new secular nation-state, where it was designated a province encompassing central Anatolia's agricultural heartland.[6] Early Republican reforms under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk emphasized secular education and infrastructure, leading to the construction of new schools and administrative buildings in Konya, though local conservative resistance to rapid secularization persisted amid broader national efforts to replace religious schooling with state-controlled systems.[34] Urban planning formalized in 1933 with the first master plan drafted by German architect Hermann Jansen, which guided expansion around the historic core, prioritizing radial road networks and green spaces while accommodating agricultural hinterlands; this was succeeded by Henri Prost's 1957 plan, extending controlled growth until 1980.[35] Architectural modernization reflected the First National Architecture style prevalent in the early Republican period (1923–1950), incorporating Ottoman motifs with Western functionalism in public structures such as government offices, post offices, and the Konya Central Bank branch, symbolizing state-driven progress amid limited private investment.[36][37] Economic development initially centered on agriculture, leveraging Konya's plains as Turkey's cereal granary for wheat and barley production, with state-led initiatives like irrigation projects enhancing yields but delaying heavy industrialization until post-1950 import-substitution policies spurred agro-processing facilities, including sugar refineries.[38] Post-1980 liberalization accelerated urbanization, with Konya attaining metropolitan status in 1989, fostering organized industrial zones and technology parks that diversified the economy into manufacturing and exports by the 2000s, supported by proximity to Ankara and improved rail links.[39] Population expansion followed inverse S-shaped urban sprawl patterns, with built-up areas growing from compact historic confines in 1923 to expansive suburbs by 2023, driven by rural migration and annual growth rates averaging 2–3% in recent decades, elevating the metropolitan population to over 2.3 million while straining infrastructure amid conservative social fabrics resistant to unchecked cosmopolitanism.[40]Geography

Location and topography

Konya is situated in the Central Anatolia Region of Turkey, approximately 37.87° N latitude and 32.49° E longitude.[41][42] The city occupies the expansive Konya Plain, an enclosed basin within the high-elevation Anatolian Plateau at roughly 1,000 meters above sea level.[43] This positioning places Konya in a semi-arid highland environment typical of central Anatolia's plateau-like terrain, which varies in elevation from 600 to 1,200 meters across the region.[44] The local topography features flat, steppe landscapes formed by lacustrine sediments and geomorphological processes reflecting past climatic variations.[45] The Konya Plain itself averages around 1,016 to 1,160 meters in elevation, with the urban center at approximately 1,030 meters.[46][47] It is bordered by surrounding mountain ranges, including extensions of the Taurus Mountains to the south and other elevated formations that enclose the basin, contributing to its isolated and arid character.[48]Hydrography and environmental features

Konya Province lies within the Konya Closed Basin, an endorheic drainage system spanning approximately 53,850 km², where surface waters do not reach the sea but instead evaporate or infiltrate local aquifers and lakes.[49] This basin features limited perennial rivers, with hydrology dominated by seasonal streams and intermittent flows, such as those analyzed in the region showing chaotic variability in daily discharge rates from 1968 to 2014.[50] Groundwater plays a critical role, feeding isolated lakes and supporting irrigation, though overextraction has led to progressive declines in aquifer levels.[51] Prominent lakes include Beyşehir Lake, Turkey's largest freshwater body at about 656 km² and 1,121 m elevation, formed by tectonic subsidence and hosting diverse islands from karst dissolution.[52] Lake Tuz, a hypersaline endorheic lake bordering the province, covers up to 1,665 km² seasonally and supplies 63% of Turkey's salt through evaporation, though it has shrunk significantly due to drought and overuse as of 2021.[53] [54] Smaller features encompass sinkhole lakes like Kızören and Timraş, which exhibit declining water levels, and volcanic crater lakes such as Meke in Karapınar district.[55] Beşgöz Lake, uniquely sustained by underground springs, maintains potable water quality amid surrounding aridity.[56] Environmentally, the province combines expansive plains covering 38% of its area with surrounding mountains like the Taurus range, fostering steppe vegetation and oases reliant on irrigation schemes.[57] Karst topography prevails due to soluble limestone, promoting sinkholes and subsidence exacerbated by groundwater depletion from agricultural demands, with nitrate and arsenic contamination detected in aquifers.[58] [59] Lake salinity has risen decennially, impacting biodiversity, while basin-wide droughts amplify groundwater stress over meteorological or surface water deficits.[60] [51]Climate

Classification and seasonal patterns

Konya features a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen-Geiger classification BSk), characterized by low annual precipitation, significant temperature seasonality, and limited moisture availability that constrains vegetation to steppe-like formations. This classification reflects mean annual precipitation of approximately 326 mm, with potential evapotranspiration exceeding rainfall, leading to water deficits year-round despite occasional winter moisture. Summers, from June to September, are hot and arid, with average daily highs reaching 30–32°C in July and August, and nighttime lows around 15–17°C; precipitation drops to minima of 5–10 mm per month, fostering dust-prone conditions and high insolation.[42] Winters, spanning December to February, are cold and relatively snowy, featuring average highs of 5–7°C and lows dipping to -2 to -4°C, with January snowfall accumulations occasionally exceeding 20 cm and precipitation peaking at 40–50 mm monthly due to cyclonic influences from the Mediterranean.[42] Spring (March–May) and autumn (October–November) serve as transitional periods, with moderating temperatures (highs 15–25°C) and higher relative precipitation shares, though totals remain modest at 30–45 mm per month, supporting brief agricultural windows amid variable frosts. The climate's aridity is exacerbated by Konya's inland plateau location at 1,016 m elevation, resulting in continentality with diurnal ranges often exceeding 15°C and infrequent but intense summer thunderstorms.[64] Annual mean temperature hovers at 11.6–12.2°C, underscoring the cold subtype within semi-arid regimes.[65][66]Historical trends and variability

Instrumental meteorological records for Konya, maintained by the Turkish State Meteorological Service since 1929, indicate an average annual temperature of 11.8°C and total precipitation of 327.6 mm, with 82.7 rainy days per year concentrated primarily in winter and spring months.[67] These averages reflect a continental semi-arid regime characterized by marked seasonal contrasts, where summers are hot and dry (July average high 30.2°C) and winters cold (January average low -4.2°C), underscoring inherent variability driven by topographic influences from the surrounding Anatolian Plateau.[67] Long-term temperature data in the Konya Closed Basin reveal increasing trends in annual mean, minimum, and maximum temperatures, with identified change points indicating accelerated warming in recent decades, analyzed via statistical methods such as Mann-Kendall tests and innovative polygon trend analysis.[68] [69] This aligns with broader patterns across Turkey, where significant positive temperature trends have been observed over the 20th and early 21st centuries.[70] Record extremes include a maximum of 40.9°C in August and a minimum of -28.2°C in January, highlighting interannual fluctuations amplified by the region's inland location.[67] Precipitation exhibits high interannual and seasonal variability, with no uniform long-term trend but notable decreases in intensity and spring-month totals (e.g., significant declines in April and May at stations like Karapınar), contributing to recurrent droughts in the endorheic Konya Basin.[71] [72] Historical records document multiple severe drought episodes, exacerbated by low baseline rainfall and groundwater overexploitation, with daily maxima reaching 73.7 mm (22 February 1945) but prolonged dry spells dominating variability.[67] [73] Such patterns, analyzed through indices like standardized precipitation, show extreme droughts persisting over 6–36 months, particularly in winter, rendering the basin highly susceptible to meteorological aridity.[74]Demographics

Population statistics and growth

As of December 31, 2024, the population of Konya Province stood at 2,330,024, comprising 1,157,080 males and 1,172,944 females, according to data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK) via the Address-Based Population Registration System.[75] This figure reflects a net increase of 9,783 residents compared to the end of 2023, when the provincial population was 2,320,241, yielding an annual growth rate of approximately 0.42%.[76] [77] The urban core of Konya, encompassing the three central districts of Karatay, Meram, and Selçuklu, accounted for 1,433,861 inhabitants in 2024, representing over 61% of the provincial total and highlighting significant urbanization within the metropolitan area.[78] Population density across the province, which spans 40,838 km², remains low at roughly 57 persons per square kilometer, though densities in urban districts exceed 2,000 per km² due to concentrated settlement patterns.[79] Historical growth in Konya Province has been steady but moderated in recent decades, driven primarily by internal migration from rural Anatolia and natural increase rather than international inflows. From 2,096,585 in 2010 to the 2024 figure, the province added over 233,000 residents, with average annual growth rates hovering between 1.0% and 1.5% through the 2010s before tapering to below 0.5% post-2020 amid national demographic shifts including aging and lower fertility rates.[77] TÜİK records indicate that net migration contributed positively, with Konya attracting workers tied to its agricultural and manufacturing sectors, though rural districts experienced outflows, contributing to a 4.2‰ provincial net growth rate in some recent years.[79]Ethnic, linguistic, and religious composition

Konya's population is ethnically predominantly Turkish, with a notable Kurdish minority concentrated in districts such as Kulu and Cihanbeyli, where communities have historical roots dating back to Ottoman-era migrations.[80] Other smaller groups include Circassians and Tatars, though they constitute minor proportions without precise official enumeration, as Turkey's national statistics do not systematically track ethnicity.[81] Linguistically, Turkish serves as the dominant and official language, spoken natively by the overwhelming majority, reflecting the region's integration into the broader Turkic linguistic landscape of central Anatolia. Kurdish dialects are spoken among the Kurdish population, primarily in rural and peripheral areas, while other minority languages like Circassian or Tatar are marginal.[82] Religiously, residents are almost entirely Sunni Muslims adhering to the Hanafi school, with the city hosting the historic Mevlevi Sufi order founded by followers of Jalal ad-Din Rumi, which emphasizes mystical practices within orthodox Sunni frameworks. Alevi communities, which blend heterodox Shia elements with folk traditions, maintain a very small and low-visibility presence in Konya, contrasting with higher concentrations in eastern Anatolia.[83] Non-Muslim minorities, such as Christians or Jews, number in the negligible hundreds or fewer, largely urban remnants of pre-republican eras, as national data registers over 99% of Turkey's population as Muslim without provincial religious breakdowns.[84] Konya's demographic profile underscores its reputation for religious homogeneity and conservatism, evidenced by high mosque density—one per approximately 145 residents as of recent assessments.[85]Government and politics

Local administration structure

Konya is governed by the Konya Metropolitan Municipality, which administers the entire province under the framework of Turkey's Law No. 5216 on Metropolitan Municipalities, with expansions via Law No. 6360 effective in 2014 that integrated all provincial territories into the metropolitan jurisdiction. This structure overlays central district municipalities, handling supra-local services including inter-district transportation, regional water and wastewater management, environmental protection, and urban planning, while delegating neighborhood-level operations to 31 district municipalities.[86][87] Executive authority resides with the elected mayor, Uğur İbrahim Altay of the Justice and Development Party, who took office on April 3, 2019, after securing 60.8% of the vote in the March 31, 2019, local elections, and was re-elected with 57.7% on March 31, 2024.[88][89] The mayor oversees daily operations through deputy mayors and a network of directorates, including six principal ones directly attached—such as Transportation, Environment, and Culture—within a total of 28 organizational units responsible for sectors like infrastructure, social services, and public health.[90][91] Legislative functions fall to the Municipal Council (Belediye Meclisi), comprising councilors directly elected from the province's districts in proportion to population during local elections, which convenes to approve annual budgets, development plans, and major policies.[92] An Executive Committee (Encümen), appointed by the mayor from council members and municipal officials, handles procurement, tenders, and administrative approvals.[93] District-level administrations mirror this model on a smaller scale, each with its own elected mayor and council tailored to local needs, ensuring coordinated governance across urban centers like Karatay, Meram, and Selçuklu, and rural peripheries.[94]Political alignment and conservatism

Konya has long served as a stronghold for conservative politics in Turkey, with unwavering support for the Justice and Development Party (AKP), a self-described conservative-democratic movement emphasizing Islamic values, national sovereignty, and traditional family structures. The AKP has controlled the metropolitan mayoralty since its inception in 2004, reflecting the electorate's preference for policies that integrate religious piety with economic development. In the March 31, 2024, local elections, incumbent AKP mayor Uğur İbrahim Altay won re-election with 49.4% of valid votes (586,529 out of 1,186,360), ahead of the Yeniden Refah Party's 23.5% and the secular Republican People's Party (CHP)'s 12.8%.[95] This outcome, amid national losses for the AKP, highlights Konya's resilience as a conservative bastion, where voter turnout reached 76% and loyalty to ruling party governance persists despite economic pressures.[95] The city's political conservatism stems from its status as Turkey's most religiously devout urban area, deeply influenced by the Sufi heritage of Mevlana Rumi and the Mevlevi order, which promotes spiritual discipline and communal ethics over individualistic secularism. Residents prioritize piety in civic life, manifesting in high mosque attendance, advocacy for religious education, and resistance to liberal social reforms such as expanded LGBTQ+ rights or relaxed alcohol regulations.[96] [97] Electoral behavior in Konya correlates strongly with religious observance, with studies tracing voter support to preferences for candidates embodying moral conservatism rather than economic populism alone.[98] This alignment extends to nationalism, as seen in endorsements of policies fortifying Turkish identity against perceived Western cultural erosion. Social conservatism in Konya reinforces political patterns, with family-centric norms, gender roles aligned with Islamic teachings, and low tolerance for public expressions of secular liberalism shaping community discourse. While urban growth and youth migration introduce modest diversification, core institutions like educational and welfare systems under AKP administration sustain traditional values, limiting opposition inroads. Fragmentation within conservatism appeared in 2024, with Yeniden Refah drawing disaffected Islamists critical of AKP compromises on issues like interest rates, yet the overall electorate remains oriented toward governance that privileges faith-based realism over progressive experimentation.[95][96]Economy

Agriculture and agribusiness

Konya Province ranks as Turkey's leading agricultural contributor, generating approximately 10% of the national agricultural production across 2.6 million hectares of farmland. The sector drives the province's highest agricultural gross domestic product in the country at 60.37 billion Turkish lira, underscoring its economic centrality. Wheat dominates as the primary crop, with Konya producing 2.24 million tons—over 10% of Turkey's total wheat output—despite a 15.4% reduction in cultivated area over the past two decades, achieved through yield improvements.[99][100][101][102] Other key staples include barley, corn, and sugar beets, where Konya holds 22.7% of national corn production and 32.3% of sugar beet output, bolstered by expanded cultivation areas for the latter by 81.4% in recent years. Dryland farming prevails for grains, but irrigation—drawing 80% from groundwater—supports higher-value crops, though this has intensified resource strain. Farmers extensively utilize groundwater for production, with studies indicating near-universal reliance in districts like Altınekin.[102][103][104] Agribusiness thrives through processing and machinery sectors; food industries feature 65% of enterprises in flour and bakery products, complemented by sugar refining via Konya Şeker, which contracts 40,000 farmers on 1 million decares and accounts for 22% of Turkey's sugar production. Konya leads nationally in agricultural machinery manufacturing, capturing significant market shares in metal processing (45%) and related equipment exports.[105][106][2] Sustainability challenges arise from groundwater overuse, causing aquifer depletion exceeding 2 meters in five years and proliferating sinkholes—hundreds reported in the past decade—which endanger farmland and infrastructure in the Konya Closed Basin. Nitrate contamination from agricultural runoff further impairs water quality, while shifts to water-intensive cash crops exacerbate drying river systems and land subsidence. These issues highlight the need for efficient irrigation and resource management to preserve productivity.[107][108][59][109][58]Manufacturing and industry

Konya's manufacturing sector accounts for 31.9% of the province's gross domestic product as of 2023, establishing it as a primary economic driver alongside agriculture and services.[110] The sector emphasizes machinery production, particularly agricultural machinery, in which Konya holds a dominant position within Turkey, alongside metal processing machines (45% national market share) and vehicle-mounted equipment (70% share).[2] Additional strengths include automotive supply components, metal casting, food processing, and shoemaking, with emerging contributions from defense, pharmaceuticals, and renewable energy equipment.[110][2] The province supports industrial activity through 12 organized industrial zones (OIZs) totaling 5,947 hectares, supplemented by three industrial zones, 150 industry sites, and two technology development zones.[111][2] Konya ranks first nationally in total industrial estate area and third in OIZ area, with key facilities like the Konya Organized Industrial Zone (KOS) encompassing 3,084 hectares, 800 parcels, and 738 active operations as of recent records.[110][111] Other notable OIZs include Çumra (980 hectares, 37 active) and Ereğli (258 hectares, 94 active), often focused on specialized manufacturing such as food processing in Akşehir's dedicated zone.[111] These zones facilitate over 1,150 active industrial sites province-wide, bolstered by proximity to high-speed rail links to Ankara (2 hours) and Istanbul (4 hours 20 minutes), as well as Mersin Port (350 km).[110] Employment in manufacturing benefits from targeted incentives, generating 8,331 jobs via 572 certificates in 2023, ranking Konya 12th among Turkish provinces.[2] The sector also drives exports, comprising 94% of Konya's $3.59 billion total in 2024 (12th nationally), with primary destinations Russia, Iraq, Germany, the United States, and Italy; this reflects a 41-fold increase since 2000.[2] Nationally, Konya leads in automotive sub-industry enterprises and ranks fourth in defense exports, underscoring its integration into broader supply chains.[110] Ongoing developments, such as specialized OIZs for agricultural machinery, aim to enhance competitiveness amid Turkey's emphasis on organized zones, which nationally host 68,000 factories contributing 45% of industrial output.[110][112]Services, tourism, and recent expansions

The service sector constitutes 47.7% of Konya's economy, encompassing logistics, education, healthcare, and trade activities that support the city's industrial and agricultural base.[110] Konya hosts major institutions such as Selçuk University, one of Turkey's largest, contributing to higher education services, while its central location facilitates logistics hubs connected to national rail and road networks.[2] Tourism forms a vital subset of services, drawing visitors primarily to cultural and religious sites linked to the legacy of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi and the Mevlevi order. Konya ranks among Turkey's most visited inland destinations, alongside Ephesus, Pamukkale, and Cappadocia, amid the national influx of over 62 million international tourists in 2024, which generated a record $61.1 billion in revenue.[113] Local tourism revenue has risen steadily, with museum visits and Sufi heritage events bolstering the sector's growth.[100] Recent expansions include the development of a new economic hub protocol signed in 2025, emphasizing transportation network upgrades, cultural-recreational spaces, and sustainable urban planning to enhance service accessibility and tourism appeal.[114] Additionally, a tourism roadmap is being prepared under the Mevlana Development Agency (MEVKA) leadership, focusing on health, gastronomy, and emerging trends to diversify offerings.[115] Proposed high-speed rail links, such as the Antalya-Alanya-Konya line, aim to integrate Konya more seamlessly into regional tourism circuits, potentially increasing visitor flows.[116] These initiatives align with 572 investment incentive certificates issued in 2023, supporting service-related job creation and infrastructure.[2]Culture and society

Religious heritage and Sufism

Konya's religious heritage is prominently shaped by its Seljuk-era Islamic architecture, reflecting the city's role as a capital of the Sultanate of Rum from the 11th to 13th centuries. The Alaeddin Mosque, situated on Alaeddin Hill, represents one of the earliest and most significant examples, with construction initiated under Sultan Mesud I in the mid-12th century and completed around 1220-1221 during the reign of Alaeddin Keykubad I.[26][117] This hilltop structure, integrated into the former citadel, served as the principal congregational mosque for Seljuk rulers and features a simple yet enduring design with a large courtyard and minbar crafted from Konya marble.[118] Later Ottoman additions, such as the Selimiye Mosque built in 1567 under Sultan Selim II, further enriched the city's mosque landscape, blending Seljuk foundations with imperial expansions.[119] Sufism holds a central place in Konya's spiritual identity, primarily through the legacy of Jalaluddin Rumi (1207–1273), the Persian poet and mystic who settled in the city around 1228 after his family's migration from Balkh.[120] Rumi's teachings emphasized divine love and spiritual ecstasy, inspiring the Mevlevi Order (Mawlawiyya), formalized by his son Sultan Veled (d. 1312) following Rumi's death on December 17, 1273.[121] The order's distinctive sema ritual, involving whirling dervishes as a form of dhikr (remembrance of God), originated here as a meditative practice symbolizing cosmic rotation and union with the divine.[122] The Mevlana Mausoleum, now the Mevlana Museum, was originally the Mevlevi tekke (dervish lodge) established over Rumi's tomb and converted to a museum in 1926 amid Turkey's secular reforms closing religious orders.[123] This Sufi tradition continues to influence Konya's cultural life, with sema performances preserved as intangible heritage, drawing pilgrims and scholars to study Rumi's Mathnawi and the order's emphasis on inner purification over external ritualism.[124] While the Mevlevi path integrated elements of Persian mysticism with Anatolian Islam, its endurance stems from Rumi's universal poetic appeal rather than institutional power, as evidenced by the order's adaptation post-Ottoman dissolution in 1925.[125]Social conservatism and family structures

Konya maintains a pronounced social conservatism, characterized by widespread adherence to traditional Islamic norms that prioritize familial duty, modesty, and gender-segregated social interactions over individualistic pursuits. This orientation stems from the city's deep-rooted Sunni Muslim identity and the enduring legacy of the Mevlevi Sufi order, fostering community expectations of piety and restraint in public life, such as limited alcohol consumption and emphasis on veiling among women. Empirical indicators include relatively low rates of secular behaviors; for instance, surveys of urban Turkey highlight Central Anatolian provinces like Konya as outliers with higher religious observance compared to coastal or western regions.[126] Family structures in Konya predominantly feature patriarchal nuclear households augmented by strong extended kin networks, where multigenerational living supports childcare and elder care amid economic pressures. Respect for parental authority and arranged or semi-arranged marriages remain normative, with consanguineous unions—particularly first-cousin marriages—prevalent at 23.2% of total marriages, as documented in a 1998 epidemiological survey, serving to reinforce clan cohesion and inheritance patterns.[127] Such practices persist despite national modernization trends, contributing to cultural continuity in a province where 14.6% of marriages involve first cousins specifically.[127] Marriage occurs earlier than the national average, with mean ages at first marriage recorded at 27.6 years for males and 23.6 years for females in provincial data, compared to Turkey's 2023 figures of 28.3 and 25.7, respectively.[128] Qualitative research on early marriages in Konya underscores their role in shaping women's trajectories, often linking them to lower educational attainment and household-centric roles, though participants report mixed satisfaction tied to familial stability.[129] Divorce remains stigmatized and infrequent relative to urban centers, aligning with conservative disincentives against marital dissolution, though exact provincial rates mirror broader Turkish declines amid socioeconomic shifts. Fertility patterns exceed national lows in conservative inland areas, supporting larger family sizes that perpetuate traditional values.[130]Cuisine, festivals, and daily life

Konya's cuisine emphasizes hearty, meat-based dishes influenced by Central Anatolian agricultural traditions and historical Seljuk, Ottoman, and Sufi culinary practices, with staples like wheat, lamb, and seasonal produce. Etliekmek, a thin flatbread topped with finely ground lamb or beef mixed with onions, tomatoes, and peppers, is baked in wood-fired ovens and served in long strips, distinguishing it from similar pide varieties elsewhere in Turkey.[131] [132] Fırın kebabı, slow-cooked lamb sealed in a bread crust and baked in earthen ovens, exemplifies the region's preference for tender, spiced meats, often accompanied by yogurt or pilaf.[133] Desserts include bıçak arası, a layered pastry filled with sweetened ground meat or nuts, and molasses-based halva made from grape or mulberry syrup, reflecting local viticulture.[134] The city hosts prominent cultural festivals tied to its Mevlevi Sufi heritage, including the annual Şeb-i Arûs (Wedding Night) commemoration from December 7 to 17, marking the death anniversary of Jalaluddin Rumi with sema ceremonies featuring whirling dervishes in white robes symbolizing spiritual ascent.[135] [136] Performances occur at the Mevlana Museum and cultural centers, drawing international visitors for music, poetry recitals, and rituals emphasizing divine love over asceticism.[137] In September, the Konya Mystic Music Festival presents open-air concerts blending traditional Sufi sounds with global mystical genres, fostering interfaith dialogue through performances at historic sites.[138] Culinary events like the Konya Gastro Fest highlight regional foods alongside live cooking demonstrations.[139] Daily life in Konya reflects its reputation as one of Turkey's most socially conservative urban centers, with routines structured around Islamic observances such as the five daily prayers broadcast via ezan calls from minarets, influencing pauses in work and commerce.[140] Family remains central, with multi-generational households prioritizing sit-down meals—often featuring homemade breads and stews—over on-the-go eating, and customs like removing shoes upon entering homes underscoring hospitality and cleanliness.[141] During Ramadan, evenings center on iftar gatherings with extended kin, emphasizing communal feasting after sunset fasts.[141] Agricultural rhythms from surrounding plains shape work patterns, with modest dress and gender-segregated social spaces prevalent in public life, though urban youth increasingly blend tradition with modern amenities like high-speed rail commutes.[140]Tourism and attractions

Historical monuments and museums

Konya's historical monuments and museums primarily feature Seljuk-era architecture from the 12th and 13th centuries, reflecting the city's role as the capital of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate. These sites include mosques, madrasas, and mausolea showcasing intricate stone and tile work, alongside museums preserving artifacts from prehistoric to Byzantine periods. The Mevlana Museum, centered on the mausoleum of the 13th-century Sufi poet Jalal ad-Din Rumi, stands as the most prominent, originally constructed as a dervish lodge following Rumi's death in December 1273 by his successor Hüsamettin Çelebi, with the current layout dating to the 16th century and conversion to a museum on March 2, 1927.[142][143] It houses sarcophagi of Rumi and his father, alongside exhibits of Mevlevi order artifacts, and received permission for ritual whirling dervish performances in 1954.[142] The Alaeddin Mosque, perched on Alaeddin Hill, represents the oldest surviving Seljuk mosque in Turkey, with construction initiated around 1155 and completed in 1220 under Sultan Alaeddin Keykubad I.[26][144] Its architecture features a distorted rectangular prayer hall supported by ancient Roman columns, a wide courtyard, and later Ottoman additions including a 19th-century mihrab, serving continuously as a place of worship.[117] Nearby, the Ince Minareli Medrese, built between 1260 and 1265 by architect Keluk bin Abdullah, functions as a museum of Seljuk stone carving, notable for its portal decorations and the remnants of its slender, earthquake-damaged brick minaret, originally over 60 meters tall.[145][146] The Karatay Medrese, constructed in 1251 by vizier Celaleddin Karatay during Sultan II. İzzeddin Keykavus's reign, operates as the Karatay Tile Works Museum since 1955, displaying Seljuk and Ottoman tiles, ceramics, and glassware, including pieces from Kubadabad Palace excavations near Beyşehir Lake.[147][148] Its turquoise-domed tomb chamber and iwans highlight Anatolian Seljuk tile artistry in Persian-influenced styles.[149] The Konya Archaeological Museum, founded in 1901 and relocated to its current site, exhibits artifacts spanning Neolithic to Byzantine eras, with standout Roman-period items including six marble sarcophagi in the primary hall, such as the Hercules Sarcophagus depicting the hero's labors, alongside pottery, mosaics, and statues from local sites.[150][151] These collections underscore Konya's layered history from Hittite and Phrygian influences through Roman and early Christian phases.[150]Cultural events and modern sites

Konya hosts the annual Mevlana Festival, also known as Şeb-i Arûs, from December 7 to 17, commemorating the death anniversary of the 13th-century Sufi poet Jalal ad-Din Rumi, featuring whirling dervish (sema) ceremonies performed by Mevlevi order practitioners as a form of spiritual meditation and devotion.[135][152] These performances, held at venues like the Mevlana Cultural Center, attract thousands of visitors annually and include traditional poetry recitations alongside the ritualistic whirling, which symbolizes union with the divine.[152][153] The International Mystic Music Festival, typically occurring in late September, blends Konya's Sufi heritage with global performances, featuring open-air concerts, exhibitions, and talks at the Mevlana Cultural Center's halls, drawing artists from various countries to explore spiritual themes through music.[138][153] Other events include the Konya Gastro Fest, initiated in 2018, which highlights local cuisine and cultural diversity through food stalls, demonstrations, and performances.[139] Among modern attractions, the Konya Tropical Butterfly Garden, opened in July 2015 in the Selçuklu district, spans 7,600 square meters total with a 1,600-square-meter indoor butterfly flight zone—Europe's largest—housing over 6,000 butterflies from 15 species amid 20,000 tropical plants, and has welcomed nearly 3 million visitors by 2023.[154][155][156] The facility, designed with climate-controlled greenhouses, promotes biodiversity education and serves as a key contemporary draw for families and tourists seeking respite from historical sites.[157][158] The Mevlana Cultural Center, a multifunctional venue completed in recent decades, hosts not only festival events but also year-round sema shows, theater, and concerts, accommodating up to several thousand spectators across its halls and supporting Konya's role as a hub for Sufi-inspired performing arts.[153][159]Infrastructure and transportation

Road and bus networks

Konya's road network includes key state highways such as D.300, which links the city to Aksaray in the east and Afyon in the west, and D.715, connecting it northward to Ankara and southward to Antalya.[160] These routes form part of Turkey's broader divided road system managed by the General Directorate of Highways, facilitating freight and passenger movement across central Anatolia.[161] The city integrates with the national motorway system via connections to the O-21 (Niğde-Aksaray-Konya motorway), which passes through Konya as part of the Ankara-Niğde Otoyolu corridor.[162] A 122-kilometer Konya Ring Road, designed as a 2x3-lane divided highway with bituminous surfacing, encircles the metropolitan area to alleviate congestion and support industrial logistics; it is divided into three sections for phased construction.[163] Additional infrastructure enhancements include the Demirkapı Tunnel, a 5-kilometer structure completed in phases to shorten routes between Konya and Antalya's Mediterranean coast.[164] Public bus services are provided by the ATUS system, operated by Konya Metropolitan Municipality, which maintains 154 routes covering 4,340 stops for intra-city mobility, complementing tram lines in underserved areas.[165] [166] Intercity bus operations center on the Konya Intercity Bus Terminal (Otogar), a modern facility spanning 146,000 square meters with amenities like waiting areas, shops, and zero-waste initiatives, serving carriers such as Metro Turizm, Kamil Koç, and Kontur for nationwide connections.[167] [168] The terminal's integration with local trams enables seamless transfers, handling high volumes of passengers from major Turkish cities.[169]Rail and high-speed connections