Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Karamanids

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

Key Information

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

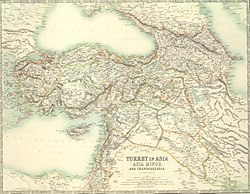

The Karamanids (Turkish: Karamanoğulları or Karamanoğulları Beyliği), also known as the Emirate of Karaman and Beylik of Karaman (Turkish: Karamanoğulları Beyliği), was a Turkish Anatolian beylik (principality) of Salur tribe origin, descended from Oghuz Turks, centered in South-Central Anatolia around the present-day Karaman Province. From the mid 14th century until its fall in 1487, the Karamanid dynasty was one of the most powerful beyliks in Anatolia.[3]

History

[edit]

The Karamanids traced their ancestry from Hodja Sad al-Din and his son Nure Sufi Bey, who emigrated from Arran (roughly encompassing modern-day Azerbaijan) to Sivas because of the Mongol invasion in 1230.

The Karamanids were members of the Salur tribe of Oghuz Turks.[4] According to others, they were members of the Afshar tribe,[5] which participated in the revolt led by Baba Ishak and afterwards moved to the western Taurus Mountains, near the town of Larende, where they came to serve the Seljuks. Nure Sofi worked there as a woodcutter. His son, Kerîmeddin Karaman Bey, gained tenuous control over the mountainous parts of Cilicia in the middle of the 13th century. A persistent but spurious legend, however, claims that the Seljuq Sultan of Rum, Kayqubad I, instead established a Karamanid dynasty in these lands.[5]

Karaman Bey expanded his territories by capturing castles in Ermenek, Mut, Ereğli, Gülnar, and Silifke. The year of the conquests is reported as 1225,[6] during the reign of Ala al-Din Kaykubadh I (1220–1237), which seems excessively early. Karaman Bey's conquests were mainly at the expense of the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia (and perhaps at the expense of Rukn al-Din Kilij Arslan IV, 1248–1265); in any case it is certain that he fought against the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia (and probably even died in this fight) to such extent that King Hethum I (1226–1269) had to place himself voluntarily under the sovereignty of the great Khan, in order to protect his kingdom from Mamluks and Seljuks (1244).

The rivalry between Kilij Arslan IV and Izz al-Din Kaykaus II allowed the tribes in the border areas to live virtually independently. Karaman Bey helped Kaykaus, but Arslan had the support of both the Mongols and Pervâne Sulayman Muin al-Din (who had the real power in the sultanate).

The Mongolian governor and general Baiju was dismissed from office in 1256 because he had failed to conquer new territories. Still, he continued to serve as a general and appeared, the same year, fighting the Sultan of Rum, who had not paid the tax, and he managed to defeat the sultan a second time. Rukn al-Din Kilidj Arslan IV got rid of almost all hostile begs and amirs except Karaman Bey, to whom he gave the town of Larende (now Karaman, in honour of the dynasty) and Ermenek (c. 1260) in order to win him to his side. In the meantime, Bunsuz, brother of Karaman Bey, was chosen as a Candar, or bodyguard, for Kilij Arslan IV. Their power rose as a result of the unification of Turkish clans that lived in the mountainous regions of Cilicia with the new Turkish population transferred there by Kayqubad.

Good relations between the Seljuqs and the Karamanids did not last. In 1261, on the pretext of supporting Kaykaus II, who had fled to Constantinople as a result of the intrigues of the chancellor Mu'in al-Din Suleyman, the Pervane, Karaman Bey and his two brothers, Zeynül-Hac and Bunsuz, marched toward Konya, the Seljuq capital, with 20,000 men. A combined Seljuq and Mongol army, led by the Pervane, defeated the Karamanid army and captured Karaman Bey's two brothers.

After Karaman Bey died in 1262, his older son, Mehmet I of Karaman, became the head of the house. He immediately negotiated alliances with other Turkmen clans to raise an army against the Seljuqs and Ilkhanids. During the 1276 revolt of Hatıroğlu Şemseddin Bey against Mongol domination in Anatolia, Karamanids also defeated several Mongol-Seljuq armies. In the Battle of Göksu in 1277 in particular, the central power of the Seljuq was dealt a severe blow. Taking advantage of the general confusion, Mehmed Bey captured Konya on 12 May and placed on the throne a pretender called Jimri, who claimed to be the son of Kaykaus. In the end, however, Mehmed was defeated by Seljuq and Mongol forces and executed with some of his brothers in 1278.

Despite these blows, the Karamanids continued to increase their power and influence, largely aided by the Mamluks of Egypt, especially during the reign of Baybars. Karamanids captured Konya on two more occasions at the beginning of the 14th century but were driven out the first time by emir Chupan, the Ilkhanid governor of Anatolia, and the second time by Chupan's son and successor Timurtash. An expansion of Karamanoğlu power occurred after the fall of the Ilkhanids in the 1330s. A second expansion coincided with Karamanoğlu Alâeddin Ali Bey's marriage to Nefise Hatun, the daughter of the Ottoman sultan Murat I, the first important contact between the two dynasties.

As Ottoman power expanded into the Balkans, Aleaddin Ali Bey captured the city of Beyşehir, which had been an Ottoman city. However, it did not take much time for the Ottomans to react and march on Konya, the Karamanoğlu capital city. A treaty between the two kingdoms was formed, and peace existed until the reign of Bayezid I.

Timur gave control of the Karamanid lands to Mehmet Bey, the oldest son of Aleaddin Ali Bey. After Bayezid I died in 1403, the Ottoman Empire went into a political crisis as the Ottoman family fell prey to internecine strife. It was an opportunity not only for Karamanids but also for all of the Anatolian beyliks. Mehmet Bey assembled an army to march on Bursa. He captured the city and damaged it; this would not be the last Karamanid invasion of Ottoman lands. However, Mehmet Bey was captured by Bayezid Pasha and sent to prison. He apologized for what he had done and was forgiven by the Ottoman ruler.

Ramazanoğlu Ali Bey captured Tarsus while Mehmet Bey was in prison. Mustafa Bey, son of Mehmet Bey, retook the city during a conflict between the Emirs of Sham and Egypt. After that, the Egyptian sultan Sayf ad-Din Inal sent an army to retake Tarsus from the Karamanids. The Egyptian Mamluks damaged Konya after defeating the Karamanids, and Mehmet Bey retreated from Konya. Ramazanoğlu Ali Bey pursued and captured him; according to an agreement between the two leaders, Mehmet Bey was exiled to Egypt for the rest of his life.

During the Crusade of Varna against the Ottomans in 1443–44, Karamanid İbrahim Bey marched on Ankara and Kütahya, destroying both cities. In the meantime, the Ottoman sultan Murad II was returning from Rumelia with a victory against the Hungarian Crusaders. Like all other Islamic emirates in Anatolia, the Karamanids were accused of treason. Hence, İbrahim Bey accepted all Ottoman terms. The Karamanid state was eventually terminated by the Ottomans in 1487, as the power of their Mameluke allies was declining. Some were resettled in various parts of Anatolia. Large groups were accommodated in northern Iran on the territory of present-day Azerbaijan.[citation needed] The main part was brought to the newly conquered territories in north-eastern Bulgaria – the Ludogorie region, another group – to what is now northern Greece and southern Bulgaria— present-day Kardzhali region and Macedonia. Ottomans founded Karaman Eyalet from former territories of Karamanids.

Power of the Karamanid state in Anatolia

[edit]According to Mesâlik-ül-Ebsâr, written by Şehâbeddin Ömer, the Karamanid army had 25,000 riders and 25,000 saracens. They could also rely on some Turkmen tribes and their warriors.

Their economic activities depended mostly on control of strategic commercial areas such as Konya, Karaman and the ports of Lamos, Silifke, Anamur, and Manavgat.

Karamanid architecture

[edit]

66 mosques, 8 hammams, 2 caravanserais and 3 medreses built by the Karamanids survived to the present day. Notable examples of Karamanid architecture include:

- Hasbey Medrese (1241)

- Şerafettin Mosque (13th century)

- İnce Minare (Dar-ül Hadis) Medrese (1258–1279)

- Hatuniye Medrese (Karaman)

- Mevlana Mosque and Tomb in Konya

- Mader-i Mevlana (Aktekke) mosque in Karaman

- Ibrahim Bey Mosque (Imaret) in Karaman

List of Karamanid Rulers

[edit]| No. | Name | Reign start | Reign end |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nure Sofi | 1250 | 1256 |

| 2. | Karim al-Din Karaman | 1256 | 1263 |

| 3. | Mehmed I | 1263 | 1277 |

| 4. | Güneri Beg | 1277 | 1300 |

| 5.. | Badr al-Din Mahmud | 1300 | 1311 |

| 6. | Yahsi Han Bey | 1311 | 1312 |

| 7. | Haci Sufi Musa | 1st:1312

2nd:1352 |

1st:1318

2nd:1356 |

| 8. | Ibrahim I | 1st:1318

2nd:1340 |

1st:1332

2nd:1349 |

| 9. | Alaeddin Halil | 1332 | 1340 |

| 10. | Ahmed I | 1349 | 1350 |

| 11 | Şemseddin Beg | 1350 | 1352 |

| 12. | Süleyman | 1356 | 1361 |

| 13. | Alaattin Ali | 1361 | 1398 |

| 14. | Mehmed II | 1st:1398

2nd:1421 |

1st:1420

2nd:1423 |

| 15. | Alaatin Ali II | 1420 | 1421 |

| 16. | Ibrahim II | 1423 | 1464 |

| 17. | Ishak Beg | 1464 | 1465 |

| 18. | Pir Ahmed II | 1465 | 1466 |

| 19. | Kasım Beg | 1466 | 1483 |

| 20. | Turgutoglu Mahmut II | 1483 | 1487 |

| 21. | Mustafa Beg | 1487 | 1501 |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "The secondary literature often mentions that Turkish was made the official language by the Karamanid ruler of south-central Anatolia, Mehmed Beg, on his conquest of Konya in 1277. However, this derives from a statement by the Persian historian Ibn Bibi that was probably intended to discredit Mehmed Beg as a barbaric Turkmen. There is no other evidence that the Karamanids ever used Turkish for official purposes or even much for literary ones.” Andrew Peacock, personal communication, May 10, 2017.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Türk Tarih Sitesi, Türk Tarihi, Genel Türk Tarihi, Türk Cumhuriyetleri, Türk Hükümdarlar – Tarih Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Green 2019, p. 62.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce Alan (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 9781438110257.

- ^ Boyacıoğlu, Ramazan (1999). Karamanoğulları'nın kökenleri (The Origin Of The Karamanids) Archived 19 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Language: Turkish. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi C.I S.3 Sivas 1999 s.,27–50

- ^ a b Cahen, Claude, Pre-Ottoman Turkey: A General Survey of the Material and Spiritual Culture and History c. 1071–1330, trans. J. Jones-Williams (New York: Taplinger, 1968), pp. 281–282.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam vol. IV, page 643.

Sources

[edit]- Leiser, Gary (2010). "The Turks in Anatolia before the Ottomans". In Fierro, Maribel (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 2: The Western Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-521-83957-0.

His ally the Qaramanid Muhammad (r. 660–77/1261–78) did capture Konya in 675/1276 and attempted to replace Persian with Turkish as the official government language.

- Green, Nile (2019). "Introduction". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press.

- Mehmet Fuat Köprülü (1992). The Origins of the Ottoman Empire. Translated by Gary Leiser. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-0819-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Jackson, Cailah (2020). "Reframing the Qarāmānids: Exploring Cultural Life through the Arts of the Book". Al-Masāq: Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean. 33 (3): 257–281. doi:10.1080/09503110.2020.1813484. S2CID 229485605.

Karamanids

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Foundation

Tribal Background and Establishment

The Karamanids traced their origins to the Oghuz Turks, a nomadic confederation whose tribes migrated westward into Anatolia amid the disruptions caused by Mongol invasions of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum following the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243.[2] These migrations, intensified by political instability and pressure from Mongol overlords in the 1230s–1260s, displaced Turkmen groups from Central Asia and eastern Iran, leading to the fragmentation of Seljuk authority and the rise of independent beyliks in the power vacuum.[2] The Karamanid lineage specifically belonged to branches of the Oghuz federation, with claims varying between the Salur and Afshar tribes, both of which contributed to the Turkic settlement of the Anatolian plateau.[6] The formal establishment of the Karamanid beylik occurred under Kerîmeddin Karaman Bey (d. c. 1261–1262), who seized control of the town of Larende—ancient Larissa, now modern Karaman—in approximately 1256 during the waning years of Seljuk influence.[7] Karaman Bey, leveraging the clan's nomadic warrior traditions, renamed the settlement after himself and used it as a strategic base amid the region's anarchy, where central Seljuk governance had collapsed under Mongol tribute demands and internal revolts.[2] This foothold marked the transition from tribal raiding bands to a nascent polity, initially semiautonomous under nominal Seljuk suzerainty granted by Sultan Kilij Arslan IV.[8] Early consolidation relied on the ghazi ethos, with Karamanid forces operating as frontier holy warriors (ghazis) against Byzantine remnants in Cappadocia and Cilicia, as well as local Armenian and Greek Christian communities, capitalizing on the ethnic and religious tensions exacerbated by Seljuk decline.[2] These activities, rooted in Turkmen pastoralist mobility and martial culture, secured initial loyalties among disparate Oghuz clans and laid the groundwork for the beylik's identity as defenders of Islam on the marches, distinct from the more urbanized Seljuk elite.[9]Initial Expansion under Karaman Bey

Karaman Bey, the eponymous founder of the Karamanid dynasty from the Afshar tribe of Oghuz Turks, capitalized on the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum's diminished authority after its decisive defeat by Mongol forces at the Battle of Köse Dağ on June 26, 1243.[10] This Mongol victory under Baiju Noyan imposed Ilkhanate suzerainty on the Seljuks, extracting heavy tribute and fragmenting central control, which enabled peripheral Turkmen chieftains to conduct independent raids and consolidate local power in Anatolia's Taurus Mountains.[11] Karaman Bey, operating from tribal bases in the western Taurus, rejected subservience to both weakened Seljuk sultans and Mongol overlords, initiating the beylik's formation as a semi-autonomous entity focused on territorial aggrandizement rather than vassalage. In the 1250s and 1260s, Karaman Bey directed military campaigns that secured core territories through the capture of strategic fortresses, including Ermenek, Mut, Ereğli, and Gülnar, thereby establishing dominance in southern-central Anatolia's mountainous frontiers.[11] These conquests filled the void left by Seljuk garrisons strained by Mongol exactions and internal rebellions, with Ereğli—previously under Seljuk influence—serving as a pivotal gateway for further incursions toward the Cilician plains. Raids extended influence toward Beyşehir, exploiting undefended plains amid the broader Anatolian fragmentation, though full control over such areas solidified only later in the century. By prioritizing defensible highland strongholds, Karaman Bey built a resilient base resilient to retaliatory strikes from Mongol-aligned Seljuk forces. The beylik under Karaman Bey symbolically oriented toward Konya, the historic Seljuk capital, as a nod to Rum's Turkish-Islamic legacy without formal allegiance, fostering claims of continuity that bolstered legitimacy among local Turkmen and Muslim populations.[11] This strategic posturing avoided direct confrontation with the Ilkhanate while enabling opportunistic advances, setting the stage for the dynasty's enduring rivalry with emerging powers in Anatolia. Karaman Bey's death around 1260 marked the transition to his successors, who inherited a consolidated enclave amid ongoing Mongol-Seljuk instability.Rise and Peak of Power

Territorial Growth in Anatolia

The Karamanids' territorial expansion in the 14th century capitalized on the Ilkhanate's disintegration after 1335, enabling absorption of fragmented local powers in central-southern Anatolia. Initial advances under Mehmed Bey I culminated in the seizure of Konya in May 1277, establishing a foothold in the former Seljuk capital and its surrounding plain, though Mongol intervention briefly halted further gains.[12][13] Güneri Bey, succeeding in 1277, pursued aggressive enlargement despite Mongol checks, incorporating castles and districts in the Taurus foothills and toward Cilicia.[14] This phase extended the beylik's reach from the Cilician coast—encompassing ports like Silifke, Anamur, and Lamos—to the Konya interior, rivaling other Anatolian principalities.[15] By mid-century, domains aligned with modern provinces of Konya, Karaman, northern Antalya, and western Mersin, facilitating Mediterranean naval forays for trade and raids. Peaceful annexations via marriage alliances and territorial purchases complemented military absorptions of weaker neighbors like remnants of the Eshrefids.[16] Temporary vassalage to the Ilkhanids secured de facto autonomy amid expansions, as nominal tribute payments averted full-scale reprisals while resources were redirected southward. Post-Ilkhanid vacuum allowed rulers like Alâeddin Ali I to claim sultanic titles, solidifying dominance without immediate Ottoman interference.[16]Key Alliances and Conflicts with Neighbors

The Karamanids maintained complex relations with neighboring Anatolian beyliks, marked by intermittent cooperation against common threats like Mongol overlords but dominated by territorial rivalries. With the Eretna Beylik, conflicts arose over central Anatolian lands, including a Karamanid defeat of Eretna forces near Ilgın in 1364 amid bids for regional dominance following the fragmentation of Seljuk authority. Relations with the Germiyanids involved occasional alignment on shared interests, such as resistance to external pressures, but were more frequently characterized by border violations, Karamanid expansionism, and competition that drove the Germiyanids to seek Ottoman protection before their absorption circa 1429.[17] Rivalries extended eastward to the Dulkadir Beylik, where competition for influence in the Taurus region and Cilician approaches fueled proxy tensions, often mediated through Mamluk patronage dynamics. Against the remnants of Seljuk authority, the Karamanids asserted independence post-Mongol invasions, capturing Konya—the former Seljuk capital—around 1277 under Mehmed Bey and positioning themselves as heirs to Seljuk legitimacy while resisting Ilkhanid suzerainty.[18] Byzantine relations soured after initial support for the exiled Seljuk claimant Kaykaus II in Constantinople around 1261, evolving into Karamanid raids on Byzantine Anatolian holdings in the late 13th century, though direct confrontations remained limited compared to western beyliks. Tensions with the Mamluk Sultanate intensified in the 15th century as Karamanid rulers challenged Cilician borders; Mehmed Beg seized Tarsus in 1417, and Ibrahim II's rebellion from 1456–1458 involved capturing fortresses like Gülek and Tarsus, prompting Sultan Inal's military expeditions funded at 3,000–4,000 dinars per emir to reassert control.[5] The Timurid invasion provided a temporary respite, enabling the Karamanids under Mehmed II to recover Anatolian territories lost to prior conquests during the Ottoman interregnum following Timur's 1402 victory at Ankara.[19] These engagements underscored the Karamanids' strategic opportunism amid Anatolia's power vacuums, balancing aggression with selective diplomacy to sustain expansion.Governance and Administration

List of Rulers

The Karamanid dynasty's rulers, titled beys or emirs, followed a succession pattern dominated by agnatic primogeniture interspersed with fratricidal conflicts, as brothers vied for control amid external pressures from Mongol Ilkhanids, Mamluks, and later Ottomans; such internal strife, documented in chronicles like those of Şikârî and Neşrī, eroded the beylik's cohesion despite periods of territorial consolidation.[20] Ottoman sources like Neşrī, compiled post-conquest, offer detailed chronologies but exhibit bias by emphasizing Karamanid defeats and portraying them as perennial rebels against Seljuk and Ottoman legitimacy.[20]| Ruler | Reign (approximate) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nūr al-Dīn Ṣūfī | Pre-1256 | Father of Karaman Beg; focused on religious leadership, delegating secular rule; buried in Ermenek.[20] |

| Karaman Beg | c. 1256–1262 | Founder; expanded from Ermenek-Mut region; died from battle wounds against Armenian ruler Hethum I.[20] |

| Şems al-Dīn Mehmed I Beg | c. 1276–1277 | Son of Karaman Beg; captured Konya in 1277 and decreed Turkish as administrative language; killed fighting Mongols.[20] |

| Günerî Beg | c. 1277–1300 | Conducted raids on Konya; died 20 April 1300.[20] |

| Maḥmūd Beg | c. 1300–1307/1308 | Son of Karaman Beg; constructed mosque and mausoleum in Ermenek (1302); died 1307/1308.[20] |

| Yak̲h̲s̲h̲î Beg | c. 1307/1308–1317/1318 | Son of Maḥmūd; seized Konya c. 1314; died 1317/1318.[20] |

| Sulaymān Beg | c. 1317/1318–1361 | Brother of Yak̲h̲s̲h̲î; assassinated in internal plot (1361).[20] |

| ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlî Beg | c. 1361–1397/1398 | Killed nephew Qāsim to usurp throne; expanded holdings before execution by Ottoman Bayezid I.[20] |

| Meḥmed Beg | c. 1402–1423 | Son of ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn; reinstated by Timur post-Ankara (1402); died besieging Antalya (1423).[20] |

| Tāj al-Dīn Ibrāhīm Beg | c. 1423–1464 | Son of Meḥmed; captured Corycus (1448); resisted Ottoman incursions until death.[20] |

| Pîr Aḥmad Beg | c. 1464–1474 | Son of Ibrāhīm; internal disputes with brothers; territory partially vassalized by Ottomans by 1474.[20] |

| Qāsim Beg | c. 1474–1483 | Brother of Pîr Aḥmad; ruled as Ottoman vassal; died 1483 amid final subjugation efforts.[20] |