Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Israeli Ground Forces

View on Wikipedia| Israeli Ground Forces | |

|---|---|

| זרוע היבשה | |

Emblem of the Israeli Ground Forces | |

| Founded | 26 May 1948 |

| Country | |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Size | |

| Part of | Israel Defense Forces |

| Headquarters | GOC Army Headquarters (Bar-Lev Camp) |

| Nickname | The Greens (הירוקים) |

| Equipment | List of equipment |

| Engagements | |

| Website | Official website |

| Commanders | |

| Commander of the Ground Forces | Major General Tamir Yadai[2] |

| Insignia | |

| Flag |  |

The Israeli Ground Forces (Hebrew: זרוע היבשה, romanized: z'róa hibshá, lit. 'Land arm') are the ground forces of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). The commander is the General Officer Commanding with the rank of major general (Aluf), subordinate to the Chief of General Staff.

An order from Defense Minister David Ben-Gurion on 26 May 1948 officially set up the Israel Defense Forces as a conscript army formed out of the paramilitary group Haganah, incorporating the militant groups Irgun and Lehi. The Ground Forces have served in all the country's major military operations—including the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, 1956 Suez Crisis, 1967 Six-Day War, 1973 Yom Kippur War, 1976 Operation Entebbe, 1982 Lebanon War, 1987–1993 First Intifada, 2000–2005 Second Intifada, 2006 Lebanon War, and the Gaza War (2008–09). While originally the IDF operated on three fronts—against Lebanon and Syria in the north, Jordan and Iraq in the east, and Egypt in the south—after the 1979 Egyptian–Israeli Peace Treaty, it has concentrated in southern Lebanon and the Palestinian territories, including the First and the Second Intifada.

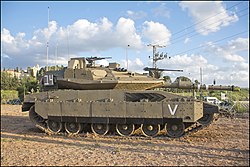

The Ground Forces uses several technologies developed in Israel such as the Merkava main battle tank, Achzarit armoured personnel carrier, the Iron Dome missile defense system, Trophy active protection system for vehicles, and the Galil and Tavor assault rifles. The Uzi submachine gun was invented in Israel and used by the Ground Forces until December 2003, ending a service that began in 1954. Since 1967, the IDF has had close military relations with the United States,[3] including development cooperation, such as on the THEL laser defense system, and the Arrow missile defense system.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

The IDF traces its roots to Jewish paramilitary organizations in the New Yishuv, starting with the Second Aliyah (1904 to 1914).[4] The first such organization was Bar-Giora, founded in September 1907. Bar-Giora was transformed into Hashomer in April 1909, which operated until the British Mandate of Palestine came into being in 1920. Hashomer was an elitist organization with narrow scope, and was mainly created to protect against criminal gangs seeking to steal property. The Zion Mule Corps and the Jewish Legion, both part of the British Army of World War I, further bolstered the Yishuv with military experience and manpower, forming the basis for later paramilitary forces.[5]

After the 1920 Palestine riots against Jews in April 1920, the Yishuv leadership realised the need for a nationwide underground defense organization, and the Haganah was founded in June of the same year.[5] The Haganah became a full-scale defense force after the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine with an organized structure, consisting of three main units—the Field Corps, Guard Corps, and the Palmach. During World War II, the Yishuv participated in the British war effort, culminating in the formation of the Jewish Brigade. These would eventually form the backbone of the Israel Defense Forces, and provide it with its initial manpower and doctrine.

Following Israel's Declaration of Independence, prime minister and defense minister David Ben-Gurion issued an order for the formation of the Israel Defense Forces on 26 May 1948. Although Ben-Gurion had no legal authority to issue such an order, the order was made legal by the cabinet on 31 May. The same order called for the disbandment of all other Jewish armed forces.[6] The two other Jewish underground organizations, Irgun and Lehi, agreed to join the IDF if they would be able to form independent units and agreed not to make independent arms purchases.

This was the background for the Altalena Affair, a confrontation surrounding weapons purchased by the Irgun resulting in a standoff between Irgun members and the newly created IDF. The affair came to an end when Altalena, the ship carrying the arms, was shelled by the IDF. Following the affair, all independent Irgun and Lehi units were either disbanded or merged into the IDF. The Palmach, a leading component of the Haganah, also joined the IDF with provisions. Ben Gurion responded by disbanding its staff in 1949, after which many senior Palmach officers retired, notably its first commander, Yitzhak Sadeh.

The new army organized itself when the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine escalated into the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, which saw neighbouring Arab states attack. Twelve infantry and armored brigades formed: Golani, Carmeli, Alexandroni, Kiryati, Givati, Etzioni, the 7th, and 8th armored brigades, Oded, Harel, Yiftach, and Negev.[7] After the war, some of the brigades were converted to reserve units, and others were disbanded. Directorates and corps were created from corps and services in the Haganah. This basic structure in the IDF still exists today.

Immediately after the 1948 war, the Israel-Palestinian conflict shifted to a low intensity conflict between the IDF and Palestinian fedayeen. In the 1956 Suez Crisis, the IDF's first serious test of strength after 1949, the new army captured the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, which was later returned. In the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel conquered the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Golan Heights from the surrounding Arab states, changing the balance of power in the region as well as the role of the IDF. In the following years leading up to the Yom Kippur War, the IDF fought in the War of Attrition against Egypt in the Sinai and a border war against the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in Jordan, culminating in the Battle of Karameh.

The surprise of the Yom Kippur War and its aftermath completely changed the IDF's procedures and approach to warfare. Organizational changes were made and more time was dedicated to training for conventional warfare. In the following years the army's role slowly shifted again to low-intensity conflict, urban warfare and counter-terrorism. An example of the latter was the successful 1976 Operation Entebbe commando raid to free hijacked airline passengers being held captive in Uganda. During this era, the IDF also mounted a successful bombing mission in Iraq to destroy its nuclear reactor.

It was involved in the Lebanese Civil War, initiating Operation Litani and later the 1982 Lebanon War, where the IDF ousted Palestinian guerilla organizations from Lebanon. Palestinian militancy has been the main focus of the IDF ever since, especially during the First and Second Intifadas, Operation Defensive Shield, the Gaza War, Operation Pillar of Defense, and Operation Protective Edge, causing the IDF to change many of its values and publish the IDF Spirit. The Lebanese Shia organization Hezbollah has also been a growing threat,[8] against which the IDF fought an asymmetric conflict between 1982 and 2000, as well as a full-scale war in 2006.

Organization

[edit]

The IDF is an integrated military force, without a separate ground arm from 1948 to 1998, when the Ground Forces were formally brought under a single command now known as GOC Army Headquarters (Hebrew: מפקדת זרוע היבשה, Mifkedet Zro'a HaYabasha, abbreviated Mazi). The Ground Forces are not yet a formal arm of the IDF, in the same way that the Israeli Air Force and Israeli Navy are.

Structure

[edit]The Ground Forces include the following Corps:

|

|

|

Units

[edit]| Ground Forces | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hebrew | English | Commander |

| חֻלְיָה Hulya |

Fire Team | Mashak Hulya ("Fire Team Leader") Corporal or Sergeant |

| כִּתָּה Kita |

Squad / Section | Mashak Kita ("Squad / Section Leader") Staff Sergeant |

| מַחְלָקָה Mahlaka |

Platoon | Mefaked Mahlaka ("Platoon Commander") Lieutenant |

| פְּלֻגָּה Pluga |

Company | Mefaked Pluga ("Company Commander") Captain |

| סוֹלְלָה Solela |

Artillery Battery | Captain or Major |

| סַיֶּרֶת Sayeret |

Reconnaissance | Captain or Major |

| גְּדוּד Gdud |

Battalion | Lieutenant-Colonel |

| חֲטִיבָה Hativa |

Brigade | Colonel |

| אֻגְדָּה Ugda |

Division | (1948–1967) Major-General (1968–Present) Brigadier-General |

| גַּיִס Gayis |

Army | Major-General |

Ranks, uniforms and insignia

[edit]Ranks

[edit]

Unlike most militaries, the IDF uses the same rank names in all corps, including the air force and navy. For ground forces' officers, rank insignia are brass on a red background. Officer insignia are worn on epaulets on top of both shoulders. Insignia distinctive to each corps are worn on the cap.

Enlisted grades wear rank insignia on the sleeve, halfway between the shoulder and the elbow. For the ground forces, the insignia are white with blue interwoven threads backed with the appropriate corps color.

From the formation of the IDF until the late 1980s, sergeant major was a particularly important warrant officer rank, in line with usage in other armies. In the 1980s and 1990s the proliferating ranks of sergeant major became devalued, and now all professional non-commissioned officer ranks are a variation on sergeant major (rav samal) with the exception of rav nagad.

Commissioned officer ranks

[edit]The rank insignia of commissioned officers.

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| רב-אלוף Rav aluf |

אלוף Aluf |

תת-אלוף Tat aluf |

אלוף משנה Aluf mishne |

סגן-אלוף Sgan aluf |

רב סרן Rav seren |

סרן Seren |

סגן Segen |

סגן-משנה Segen mishne | ||||||||||||||||

Other ranks

[edit]The rank insignia of non-commissioned officers and enlisted personnel.

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| רב-נגד Rav nagad |

רב-סמל בכיר Rav samal bakhír |

רב-סמל מתקדם Rav samal mitkadem |

רב-סמל ראשון Rav samal rishon |

רב-סמל Rav samal |

סמל ראשון Samal rishon |

סמל Samal |

רב טוראי Rav turai |

טוראי Turai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Uniforms

[edit]

The Israel Defense Forces has several types of uniforms:

- Service dress (מדי אלף Madei Alef – Uniform "A") – the everyday uniform, worn by everybody.

- Field dress ( מדי ב Madei Bet – Uniform "B") – worn into combat, training, work on base.

The first two resemble each other but the Madei Alef is made of higher quality materials in a golden-olive while the madei bet is in olive drab.[10][11] The dress uniforms may also exhibit a surface shine[11][12]

- Officers / Ceremonial dress (מדי שרד madei srad) – worn by officers, or during special events/ceremonies.

- Dress uniform and mess dress – worn only abroad. There are several dress uniforms depending on the season and the branch.

The service uniform for all ground forces personnel is olive green. The uniforms consist of a two-pocket shirt, combat trousers, sweater, jacket or blouse, and shoes or boots. The green fatigues are the same for winter and summer and heavy winter gear is issued as needed. Women's dress parallels the men's but may substitute a skirt for the trousers.

Headgear included a service cap for dress and semi-dress and a field cap or "Kova raful" bush hat worn with fatigues. IDF personnel generally wear berets in lieu of the service cap and there are many beret colors issued to IDF personnel. Paratroopers are issued a maroon beret, Golani brown, Givati purple, Nahal lime green, Kfir camouflage, Combat Engineers gray. Other beret colors are: black for armored corps, turquoise for artillery personnel. For all other ground personnel, except combat units, the beret for men was green and for women, black.

In combat uniforms the Orlite helmet has replaced the British Brodie helmet Mark II/Mark III, RAC Mk II modified helmet with chin web jump harness used by paratroopers and similar to the HSAT Mk II/Mk III paratrooper helmets,[13] US M1 helmet,[14] and French Modèle 1951 helmet – previously worn by Israeli infantry and airborne troops from the late 1940s to the mid-1970s and early 1980s.[15]

Some corps or units have small variations in their uniforms – for instance, military policemen wear a white belt and police hat. Paratroopers are issued a four pocket tunic (yarkit/yerkit) worn untucked with a pistol belt cinched tight around the waist over the shirt.[16]

Most IDF soldiers are issued black leather combat boots, certain units issue reddish-brown leather boots for historical reasons — the paratroopers,[16] combat medics, Nahal and Kfir Brigades, as well as some Special Forces units (Sayeret Matkal, Oketz, Duvdevan, Maglan, and the Counter-Terror School). Women were formerly issued sandals, but this practice has ceased.

Insignia

[edit]

IDF soldiers have three types of insignia, other than rank insignia, which identify their corps, specific unit, and position.

A pin attached to the beret identifies a soldier's corps. Soldiers serving in staffs above corps level are often identified by the General Corps pin, despite not officially belonging to it, or the pin of a related corps. New recruits undergoing tironut (basic training) do not have a pin. Beret colors are also often indicative of the soldier's corps. Most non-combat corps do not have their own beret, and sometimes wear the color of the corps to which the post they're stationed in belongs. Individual units are identified by a shoulder tag attached to the left shoulder strap. Most units in the IDF have their own tags, although those that do not, generally use tags identical to their command's tag (corps, directorate, or regional command).

While one cannot always identify the position/job of a soldier, two optional factors help make this identification: an aiguillette attached to the left shoulder strap and shirt pocket, and a pin indicating the soldier's work type, usually given by a professional course. Other pins may indicate the corps or additional courses taken. An optional battle pin indicates a war that a soldier has fought in.

Service

[edit]The military service is held in three different tracks:

- Regular service (שירות חובה): mandatory military service which is held according to the Israeli security service law.

- Permanent service (שירות קבע): military service which is held as part of a contractual agreement between the IDF and the permanent position-holder.

- Reserve service (שירות מילואים): a military service in which citizens are called for active duty of at most a month every year, in accordance with the Reserve Service Law, for training and ongoing military activities and especially for the purpose of increasing the military forces in case of a war.

Sometimes the IDF would also hold pre-military courses (קורס קדם צבאי or קד"צ) for soon-to-be regular service soldiers.

Women

[edit]

Israel is one of only a few nations that conscript women or deploy them in combat roles. In practice, women can avoid conscription through a religious exemption and over a third of Israeli women do so.[17] As of 2010, 88% of all roles in the IDF are open to female candidates, and women were found in 69% of all IDF positions.[18]

According to the IDF, 535 female Israeli soldiers were killed in combat operations in the period 1962–2016,[19] and dozens before then. The IDF says that fewer than 4 percent of women are in combat positions. Rather, they are concentrated in "combat-support" positions which command a lower compensation and status than combat positions.[20]

Mission

[edit]

The IDF's mission is to "defend the existence, territorial integrity and sovereignty of the state of Israel. To protect the inhabitants of Israel and to combat all forms of terrorism which threaten the daily life."[21]

The Israeli military's primary principles derive from Israel's need to combat numerically superior opponents. One such principle, is the concept that Israel cannot afford to lose a single war. The IDF believes that this is possible if it can rapidly mobilize troops to insure that they engage the enemy in enemy territory.[22] In the 21st century, various nonconventional threats including terrorist organizations, subterranean infrastructure operated by Hamas, etc. have forced the IDF to modify its official defense doctrine.[23]

Field rations

[edit]Field rations, called manot krav, usually consist of canned tuna, sardines, beans, stuffed vine leaves, maize and fruit cocktail and bars of halva. Packets of fruit flavored drink powder are provided along with condiments like ketchup, mustard, chocolate spread and jam. Around 2010, the IDF announced that certain freeze dried MREs served in water-activated disposable heaters like goulash, turkey schwarma and meatballs would be introduced as field rations.[24]

One staple of these rations was loof, a type of Kosher spam made from chicken or beef that was phased out around 2008.[25] Food historian Gil Marks has written that: "Many Israeli soldiers insist that Loof uses all the parts of the cow that the hot dog manufacturers will not accept, but no one outside of the manufacturer and the kosher supervisors actually know what is inside."[26]

Weapons and equipment

[edit]

The Ground Forces possess various domestic and foreign weapons and computer systems. Some equipment is from the United States, modified for IDF use, such as the M4A1 and M16 assault rifles, the M24 SWS 7.62 mm bolt action sniper rifle, the SR-25 7.62 mm semi-automatic sniper rifle, and the AH-1 Cobra and AH-64D Apache attack helicopters.

Israel has a domestic arms industry, which has developed weapons and vehicles such as the Merkava battle tank series, and various small arms such as the Galil and Tavor assault rifles, and the Uzi submachine gun.

Israel has installed a variant of the Samson RCWS, a remote controlled weapons platform, which can include machine guns, grenade launchers, and anti-tank missiles on a remotely operated turret, in pillboxes along the Israeli Gaza Strip barrier to prevent Palestinian militants from entering its territory.[27][28] Israel has developed observation balloons equipped with sophisticated cameras and surveillance systems used to thwart terror attacks from Gaza.[29]

The Ground Forces possess advanced combat engineering equipment including the IDF Caterpillar D9 armored bulldozer, IDF Puma combat engineering vehicle, Tzefa Shiryon and CARPET minefield breaching rockets, and a variety of robots and explosive devices.

Future

[edit]

The IDF is planning a number of technological upgrades and structural reforms for the future. Training has been increased with greater cooperation between ground, air, and naval units.[30]

The Ground Forces are phasing out the M-16 rifle in favor of the IWI Tavor variants, most recently the IWI Tavor X95 flat-top ("Micro-Tavor Dor Gimel").[31] The outdated M113 armored personnel carriers are being replaced by the new Namer APCs, with 200 ordered in 2014, as well as obtaining the Eitan AFV, and upgrading the IDF Achzarit APCs.[32][33]

The backbone of the Artillery Corps, the M109 howitzer, will be phased out in favor of a still-undecided replacement, with the ATMOS 2000 and Artillery Gun Module under primary consideration.[34]

The IDF is planning a future tank to replace the Merkava, which will be able to fire lasers and electromagnetic pulses, run on a hybrid engine, with a crew as small as two, will be faster, and will be better-protected, with emphasis on active protection systems such as the Trophy over armor.[35][36]

The Combat Engineering Corps assimilated new technologies, mainly in tunnel detection and unmanned ground vehicles and military robots, such as remote-controlled IDF Caterpillar D9T "Panda" armored bulldozers, Sahar engineering scout robot and improved Remotec ANDROS robots.

See also

[edit]- Israeli Air Force

- Israeli Navy

- Israeli Intelligence Community

- Israel Border Police

- Israel Military Industries

Related subjects

[edit]References and footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b International Institute for Strategic Studies (15 February 2023). The Military Balance 2023. London: Routledge. p. 331. ISBN 9781032508955.

- ^ "General Staff". Israel Defense Forces. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Mahler, Gregory S. (1990). Israel After Begin. SUNY Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7914-0367-9.

- ^ Speedy (12 September 2011). "The Speedy Media: IDF's History". Thespeedymedia.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b "HAGANAH". encyclopedia.com. The Gale Group, Inc. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

The Haganah ("defense") was founded in June 1920...

- ^ Ostfeld, Zehava (1994). Shoshana Shiftel (ed.). An Army is Born (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Israel Ministry of Defense. pp. 104–106. ISBN 978-965-05-0695-7.

- ^ Pa'il, Meir (1982). "The Infantry Brigades". In Yehuda Schiff (ed.). IDF in Its Corps: Army and Security Encyclopedia (in Hebrew). Vol. 11. Revivim Publishing. p. 15.

- ^ "Hezbollah hiding 100,000 missiles that can hit north, army says". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ a b "עושים לכם סדר בדרגות". idf.il (in Hebrew). Israel Defense Forces. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Israeli Defence Forces since 1973, Osprey – Elite Series #8, Sam Katz 1986, ISNC 0-85045-887-8

- ^ a b "Guide to Israeli Militaria, Insignia, Badges, Uniforms & Unit Formations at Historama.com | The Online History Shop". Historama.com. 2 August 1945. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "GarinMahal – Your first day in the IDF". Archived from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Katz & Volstad, Israeli Elite Units since 1948 (1988), pp. 53–54; 56.

- ^ Katz & Volstad, Israeli Elite Units since 1948 (1988), pp. 54–55; 57–59.

- ^ Katz & Volstad, Israeli Elite Units since 1948 (1988), p. 60.

- ^ a b "Paratroopers Brigade". Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Abuse of IDF Exemptions Questioned Archived 10 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Jewish Daily Forward, 16 December 2009

- ^ Statistics: Women's Service in the IDF for 2010 Archived 13 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine IDF, 25 August 2010

- ^ "Israeli woman who broke barriers downed by Hezbollah rocket as 2006 combat volunteer – Israel News". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Gaza: It's a Man's War Archived 8 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Atlantic, 7 August 2014

- ^ "IDF desk – Doctrine, Mission". Dover.idf.il. Archived from the original on 2 November 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ "Israel Defense Forces". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ "Israel Defense Forces Strategy Document". belfercenter.org. Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ Steinberg, Jessica. "The rationale behind the rations". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "6 things you never knew about Spam" (Text.Article). The Daily Meal. 28 September 2016. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Kosher Spam: a Breef history". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 20 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Weaponized Sentry-Tech Towers Protecting Hot Borders". Aviationweek.com. 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Palestine Chronicle (13 July 2010). "Israel's New 'Video Game' Executions". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 8 August 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "IDF observation balloon crashes near Gaza" Archived 6 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Ynet News 5 May 2012

- ^ "Analysis The Israeli Army's New Target: Itself". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Jerusalem Post: IDF phasing out M-16 in favor of Israeli-made Tavor (19 December 2012)

- ^ "Israel to upgrade more Achzarit APCs". Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Yehoshua, Yossi (22 September 2014). "Ya'alon approves addition of 200 advanced APCs for the IDF". ynet. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Administrator. "Israel Army wants to replace old 155mm howitzer M109 with Soltam or AGM artillery system 3010134 – October 2013 defense industry military news UK – Military army defense industry news year 2013". Archived from the original on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Jerusalem Post: The IDF's future tank: Electromagnetic cannon

- ^ "IDF to discharge 100,000 reservists, slash officer corps". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Marcus, Raphael D. Israel's Long War with Hezbollah: Military Innovation and Adaptation under Fire (Georgetown UP, 2018) online review

- Rosenthal, Donna (2003). The Israelis. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-7035-9.

- Ostfeld, Zehava (1994). Shiftel, Shoshana (ed.). An Army is Born (in Hebrew). Israel Ministry of Defense. ISBN 978-965-05-0695-7.

- Gelber, Yoav (1986). Nucleus for a Standing Army (in Hebrew). Yad Ben Tzvi.

- Yehuda Shif, ed. (1982). IDF in Its Corps: Army and Security Encyclopedia (18 volumes) (in Hebrew). Revivim Publishing.

- Ron Tira, ed. (2009). The Nature of War: Conflicting Paradigms and Israeli Military Effectiveness. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-84519-378-2.

- Roislien, Hanne Eggen (2013). "Religion and Military Conscription: The Case of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF)," Armed Forces & Society 39, No. 3, pp. 213–232.

- Country Briefing: Israel, Jane's Defence Weekly, 19 June 1996

External links

[edit]Israeli Ground Forces

View on GrokipediaHistory

Pre-State Origins and Formation (1920s-1948)

The Haganah, the primary Jewish paramilitary organization in Mandatory Palestine, was established in June 1920 following Arab riots in Jerusalem and other areas that targeted Jewish communities, prompting the need for organized self-defense amid British authorities' perceived inability or unwillingness to protect settlers.[5] Initially a loose network of local watch groups in urban centers and agricultural settlements, it coordinated volunteer efforts to guard against sporadic Arab assaults, drawing on prior informal militias like Hashomer.[6] By the early 1920s, these groups had repelled attacks during the 1921 Jaffa riots, where over 40 Jews were killed, underscoring the causal link between unchecked violence and the imperative for autonomous Jewish security forces.[7] The 1929 Palestine riots, incited by rumors of Jewish threats to the Al-Aqsa Mosque and spreading to massacres in Hebron (67 Jews killed) and Safed (18-20 killed), further galvanized Haganah expansion, with its units successfully defending settlements like Motza and Hartuv while British forces focused on containment rather than prevention.[8] During the 1936-1939 Arab Revolt, which involved widespread ambushes, bombings, and killings of over 500 Jews, the Haganah evolved from defensive postures to proactive operations, including the formation of Special Night Squads under British officer Orde Wingate to patrol vulnerable roads and kibbutzim, involving up to 15,000 fighters by the revolt's peak.[9] This period marked a shift toward military professionalization, with training in explosives, intelligence, and fieldcraft, as Arab irregulars—numbering in the thousands—disrupted economic life and targeted Jewish transport, necessitating Haganah countermeasures that preserved community viability without offensive escalation beyond retaliation.[5] In response to fears of Axis invasion during World War II, the Palmach was created on May 19, 1941, as the Haganah's elite mobile strike brigades, comprising full-time volunteers organized into platoons for rapid response and sabotage preparation, funded initially through a clandestine "1:10" levy on Yishuv salaries.[10] Post-war, amid British restrictions on Jewish immigration, the Haganah orchestrated Aliyah Bet operations to smuggle over 100,000 Holocaust survivors into Palestine between 1945 and 1948, defying quotas under the 1939 White Paper that capped Jewish entry at 75,000 over five years despite Europe's displaced persons crisis.[11] The United Nations Partition Plan of November 29, 1947, which proposed Jewish and Arab states, triggered immediate Arab assaults on Jewish areas, prompting Haganah mobilization of 40,000-60,000 personnel into structured field corps and regional commands for perimeter defense and convoy protection, laying the groundwork for territorial defense without yet assuming state-level authority.[12]War of Independence and Early Conflicts (1948-1967)

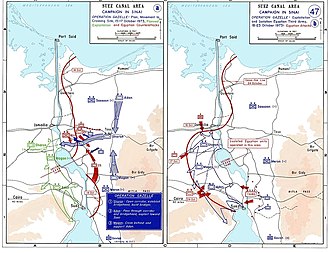

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) ground forces, established on May 26, 1948, immediately faced invasion by Arab armies from Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, which deployed an initial combined strength of approximately 40,000 troops against Israel's roughly 30,000 mobilized personnel, many lacking heavy weapons or formal training.[13] Despite this inferiority in numbers and equipment, IDF units secured improvised victories through rapid mobilization and tactical adaptation, exemplified by Operation Nachshon from April 5 to 20, 1948, in which 1,500 Haganah troops assaulted Arab positions to reopen the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv road, enabling vital supply convoys and breaking the month-long siege of Jerusalem at a cost of 39 Israeli and 31 Arab fatalities in key clashes.[14][15] Subsequent defensive operations halted Egyptian advances in the Negev and repelled assaults on central fronts, culminating in 1949 armistice agreements that established the Green Line demarcation, under which Israel retained control of about 77 percent of the former British Mandate territory, exceeding the UN partition proposal allocations.[16] In the post-armistice period, IDF ground forces contended with persistent fedayeen incursions—guerrilla raids by Palestinian infiltrators backed by Egypt from Gaza and Jordan from the West Bank—resulting in 101 Israeli deaths and 364 injuries from Egyptian-supported actions alone by mid-1956.[17] These cross-border attacks, violating armistice terms, targeted civilians and infrastructure, prompting IDF reprisal operations to deter further aggression and degrade raider capabilities, such as the August 31, 1955, raid on Khan Yunis that eliminated 72 fedayeen.[18] The cumulative threat, exacerbated by Egypt's blockade of Israeli shipping through the Straits of Tiran and Suez Canal, necessitated a sustained military buildup, expanding ground force strength from 190,000 in the early 1950s to 250,000 by 1956.[19][20] This escalation led to the Sinai Campaign, initiated as a preemptive ground offensive on October 29, 1956, when IDF paratroopers dropped at the Mitla Pass and armored brigades overran Egyptian defenses at Abu Ageila, enabling a swift advance across the 200-mile Sinai Peninsula to the Suez Canal in just 100 hours under Chief of Staff Moshe Dayan.[21][22] The operation inflicted disproportionate casualties—231 Israeli soldiers killed and 900 wounded against over 1,000 Egyptian dead and 4,000 wounded—while temporarily securing the peninsula and neutralizing fedayeen bases, though international pressure forced withdrawal by March 1957 in exchange for UN peacekeeping deployment along the border.[19] These engagements underscored the ground forces' reliance on surprise, mobility, and interior positioning to offset encirclement vulnerabilities, yielding empirical advantages in casualty ratios and territorial control despite ongoing Arab numerical edges.[23]Six-Day War and Attrition Period (1967-1973)

The Six-Day War commenced on June 5, 1967, with Israeli ground forces launching offensives following preemptive airstrikes that neutralized much of the Egyptian Air Force, destroying 338 of 425 aircraft.[24] Soviet arms deliveries to Egypt had bolstered Arab military capabilities, eroding Israel's qualitative superiority and prompting heightened mobilization amid intelligence reports of Egyptian troop concentrations in Sinai.[25] In the Sinai theater, three armored divisions under Brigadier Generals Israel Tal, Ariel Sharon, and Avraham Yoffe executed deep penetrations and indirect maneuvers to bypass Egyptian fortifications, with Tal advancing from Rafah in the north, Sharon assaulting the entrenched Abu Ageila position, and Yoffe traversing central dunes to sever retreat routes.[24] [19] These operations exemplified rapid armored blitzkrieg tactics, synchronizing infantry assaults, engineer breaches, and tank envelopments to shatter Egyptian defenses; Sharon's division, for instance, captured Abu Ageila by June 6 after flanking maneuvers and paratrooper drops disrupted artillery support.[24] By June 8, Israeli forces had overrun Sinai, inflicting heavy losses on seven Egyptian divisions, including over 10,000 killed, 1,500 officers, and more than 5,000 captured alongside 11 generals, while defeating an estimated 100,000 troops and 900 tanks through superior maneuver and intelligence on enemy dispositions.[24] [19] Similar ground advances secured the West Bank from Jordanian forces and Golan Heights from Syria by June 10, underscoring the role of preemptive action in averting a multi-front assault amid escalating Arab-Soviet alignments.[25] The ensuing War of Attrition, from mid-1967 to 1970, shifted to static border defense along the Suez Canal, where Egyptian artillery barrages beginning July 1, 1967, targeted Israeli positions, met with reciprocal shelling and armored counter-raids.[26] Israeli ground forces adapted to grinding engagements, constructing fortified lines, security fences, and ambush networks in the Jordan Valley and Golan to counter infiltrations and commando crossings, while conducting cross-canal incursions like Operation Shock in September 1968 against Egyptian infrastructure.[26] Tactics emphasized detection of Egyptian tunneling attempts under the canal for sabotage, artillery duels neutralizing gun emplacements, and limited armored probes, such as the September 1969 Gulf of Suez incursion and May 1970 "Fatahland" operation seizing key terrain.[26] These defensive shifts reflected sustained mobilization to deter renewed Soviet-backed offensives, sustaining Israeli control over captured territories amid persistent low-intensity threats.[25]Yom Kippur War and Operational Shifts (1973-1982)

On October 6, 1973, Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal into the Sinai Peninsula with approximately 100,000 troops, 900 tanks, and extensive anti-tank and anti-air defenses, while Syrian forces simultaneously assaulted Israeli positions on the Golan Heights, achieving initial breakthroughs due to the surprise element and Israel's incomplete mobilization.[27][28] Israeli ground forces, caught with minimal active-duty presence—relying heavily on reserves that took 24-48 hours to fully activate—suffered severe early setbacks, losing around 40% of their tank strength by the third day across both fronts.[29][30] In the Golan Heights, the Battle of the Valley of Tears exemplified the intense armored engagements, where a small Israeli tank force under Lt. Col. Avigdor Kahalani, numbering about 40 tanks, repelled waves of Syrian armor over four days starting October 6, destroying an estimated 260-300 Syrian tanks and armored vehicles while losing 60-80 Israeli vehicles, through superior crew training, terrain exploitation, and defensive positioning despite numerical inferiority of roughly 1:12.[31][27] By October 10, Israeli reserves had reinforced sufficiently to counteroffensive, pushing Syrian forces back beyond pre-war lines.[27] In the Sinai, after stabilizing the front, the IDF's 143rd Reserve Armored Division under Maj. Gen. Ariel Sharon executed a daring crossing of the Suez Canal on the night of October 15-16, establishing a bridgehead west of the canal with engineer bridges under fire, advancing northward to encircle the Egyptian Third Army by October 25, cutting key supply lines and forcing a ceasefire.[29][32] This maneuver, involving over 20,000 troops and 200 tanks by the operation's end, demonstrated adaptive ground operations that turned the tide despite initial losses exceeding 2,500 Israeli fatalities overall.[32] The Agranat Commission, established in November 1973 to probe the war's prelude, attributed the surprise primarily to intelligence failures rooted in the "konseptziya"—a doctrinal assumption that Arab states lacked the capability or will for coordinated multi-front war—resulting in insufficient warnings and delayed reserve call-ups, leaving ground forces unprepared with only partial deployments on Yom Kippur.[33][34] While critiquing military leadership for inadequate preparedness, the commission noted the effective operational recovery once reserves mobilized, highlighting causal factors like over-reliance on preemptive deterrence rather than robust active defenses.[34] These findings prompted internal reforms, including enhanced mobilization protocols and decentralized command to mitigate future delays.[33] Post-war operational shifts emphasized a qualitative military edge (QME) to offset persistent numerical disadvantages, accelerated by U.S. Operation Nickel Grass airlift—which delivered 22,500 tons of supplies, including ammunition and replacement tanks during the conflict—and subsequent quadrupling of annual U.S. military aid from pre-1973 levels, enabling procurement of advanced systems over sheer quantity.[35][36] The concurrent 1973 oil embargo exacerbated economic strains, with oil prices quadrupling and causing shortages that underscored vulnerabilities in sustaining prolonged mobilizations, reinforcing a reserve-heavy structure—over 80% of IDF ground strength from reserves—while prioritizing fuel-efficient logistics and high-technology integrations for rapid, decisive engagements.[37][38] This evolution marked a pivot from mass armored doctrines toward precision and initiative-driven tactics, informed by empirical losses where Arab forces inflicted disproportionate early damage through attrition-focused defenses.[36][29]Lebanon Invasions and Intifadas (1982-2005)

In June 1982, the Israeli Defense Forces launched Operation Peace for Galilee to neutralize Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) bases in southern Lebanon, which had launched over 1,392 attacks causing deaths in Israel since 1965.[39] Ground forces, including armored brigades and infantry divisions, advanced up to 40 kilometers from the border to destroy terrorist infrastructure and prevent rocket fire into northern Israeli communities.[40] Key engagements involved rapid maneuvers against PLO fighters and Syrian forces, with IDF casualties totaling 654 killed and 3,887 wounded from 1982 to 1985.[41] The operation expelled PLO leadership from Beirut by late August, though it extended beyond initial limited objectives due to urban combat and Syrian intervention.[42] Following the invasion, IDF maintained a security zone in southern Lebanon until 2000, facing escalating guerrilla warfare from Hezbollah militants who adapted to asymmetric tactics like ambushes and roadside bombs.[43] This low-intensity conflict imposed heavy operational burdens on ground units, including patrols and buffer zone defenses, resulting in 1,216 Israeli soldiers killed between June 1982 and the withdrawal.[44] Hezbollah's attrition strategy exploited terrain and local proxies, straining IDF resources and domestic support amid protests against prolonged occupation.[45] On May 24, 2000, IDF unilaterally withdrew to the international border, dismantling outposts and handing positions to the South Lebanon Army ally, which collapsed shortly after.[46] The First Intifada, erupting on December 9, 1987, in the Gaza Strip and spreading to the West Bank, involved widespread Palestinian riots, stone-throwing, and Molotov cocktails against Israeli civilians and security forces.[47] IDF ground units shifted to counter-riot operations, employing non-lethal measures like tear gas and plastic bullets alongside live fire when troops faced imminent threats from mobs or armed assailants.[48] Over the six-year period ending with the Oslo Accords in 1993, approximately 1,000-1,200 Palestinians were killed by security forces, many during clashes, while 100 Israelis died, including 60 security personnel.[49] Tactics emphasized force protection and area denial, though international reports highlighted excessive force allegations in crowd control.[47] The Second Intifada, beginning September 28, 2000, escalated to coordinated Palestinian militant assaults, including over 130 suicide bombings that killed more than 1,000 Israeli civilians and soldiers by 2005.[50] IDF responded with Operation Defensive Shield in March-April 2002, deploying armored and infantry forces to reoccupy West Bank cities, dismantle bomb-making labs, and arrest thousands of operatives, reducing attack capabilities.[51] To counter infiltrations, construction of the West Bank security barrier commenced in June 2002, featuring fences, ditches, and patrol roads; by 2005, completed segments correlated with a sharp decline in successful terrorist entries, from hundreds monthly pre-barrier to near zero in fenced areas.[52][53] Suicide bombings, peaking at dozens annually in 2002-2003, fell drastically post-barrier phases, with data showing over 90% reduction in West Bank-originated attacks inside Israel proper.[54] Ground forces integrated barrier patrols with intelligence-driven raids, adapting to urban threats while enabling phased Gaza disengagement in 2005.[55]Second Lebanon War and Gaza Operations (2006-2022)

The Second Lebanon War erupted on July 12, 2006, following Hezbollah's cross-border raid that killed eight Israeli soldiers and abducted two others, prompting an initial Israeli air campaign aimed at degrading Hezbollah's rocket infrastructure.[56] Despite airstrikes destroying an estimated 20-30% of Hezbollah's longer-range rocket launchers, the group fired over 4,000 rockets into northern Israel over 34 days, exposing the limitations of air-centric operations against dispersed, mobile guerrilla threats embedded in civilian areas.[57] The Winograd Commission later critiqued IDF ground force hesitancy, attributing it to overreliance on standoff fires and inadequate preparation for close-quarters combat, which allowed Hezbollah to maintain operational tempo.[58] Ground operations commenced on July 18, 2006, with limited incursions escalating to a broader invasion by late July, involving divisions like the 36th and 91st, to dismantle Hezbollah positions in southern Lebanon and establish a security buffer zone.[59] IDF forces encountered intense resistance, including anti-tank guided missiles and improvised explosive devices, resulting in 121 soldier deaths and exposing deficiencies in infantry training and combined arms tactics against hybrid warfare.[56] By the ceasefire on August 14 under UN Resolution 1701, ground advances had cleared key villages and degraded some launch sites, though Hezbollah retained significant rocket stocks and leadership intact, underscoring that aerial precision alone could not neutralize entrenched subterranean and mobile arsenals without boots on the ground.[60] In Gaza, recurrent Hamas rocket barrages—totaling thousands annually—necessitated repeated operations, revealing similar constraints on air power against tunnel-facilitated incursions and smuggling. Operation Cast Lead, from December 27, 2008, to January 18, 2009, began with airstrikes but shifted to a ground phase on January 3, deploying three divisions to dismantle rocket production sites and early tunnel networks amid urban fighting.[61] IDF forces destroyed over 1,000 targets, including rocket manufacturing facilities, and neutralized several smuggling tunnels, though Hamas fired 800+ rockets during the campaign, firing rates temporarily reduced post-operation.[61] Operation Pillar of Defense, November 14-21, 2012, emphasized air strikes and targeted killings, such as that of Hamas military chief Ahmed Jabari, suppressing rocket fire from over 100 daily launches to near zero by ceasefire, without a ground incursion due to assessed risks of tunnel ambushes.[62] This approach achieved short-term deterrence but left underground infrastructure largely untouched, as evidenced by subsequent Hamas rearmament.[63] Operation Protective Edge, July 8 to August 26, 2014, followed Hamas tunnel infiltrations into Israel, initiating with air operations before a ground offensive on July 17 involving multiple brigades to systematically map and demolish the network.[64] IDF engineers and infantry destroyed 32 cross-border attack tunnels—spanning up to 1.5 km each—and over 3,000 rocket launchers, amid 4,500+ projectiles fired by militants, with ground maneuvers enabling direct degradation of subterranean threats that airstrikes could not reliably address.[65][64] These engagements demonstrated that while air power could disrupt surface-level rocket salvos, persistent tunnel and bunker systems demanded ground penetration to achieve verifiable reductions in offensive capabilities.[66]Post-October 7 Conflicts (2023-2025)

Following the Hamas-led incursion into southern Israel on October 7, 2023, which killed approximately 1,200 people and resulted in the abduction of over 250 hostages, the Israeli Ground Forces initiated targeted raids into northern Gaza on October 26, using tanks and infantry to prepare for broader operations.[67][68] A full-scale ground invasion commenced on October 27, involving armored brigades and infantry divisions advancing to dismantle Hamas infrastructure, including extensive tunnel networks.[69] By early 2024, operations expanded into central and southern Gaza, with forces from multiple divisions conducting clearance missions in urban areas like Khan Yunis and Rafah to neutralize militant positions.[70] In 2024 and into 2025, ground units refocused on Gaza City, deploying three divisions for systematic advances that severed connections between northern and central sectors, destroying command centers and weapon caches amid dense urban terrain.[71][70] These efforts emphasized subterranean warfare tactics, with engineering units breaching fortified underground facilities, contributing to the degradation of Hamas's operational capacity despite high civilian density and booby-trapped environments.[69] IDF casualty ratios remained favorable, with ground forces reporting over 17,000 militants killed in Gaza by mid-2025, compared to 891 total IDF combat deaths across fronts by January 2025, reflecting advantages in armored protection, precision fires, and intelligence-driven maneuvers.[72][73] Concurrently, escalating rocket fire from Hezbollah prompted a ground incursion into southern Lebanon beginning September 30, 2024, with infantry and armored units crossing the border to dismantle border launch sites and command posts up to several kilometers deep.[74][75] Operations targeted Hezbollah's Radwan Force, involving raids on villages like Ayta al-Shab and Kafr Kila, resulting in the destruction of over 490 targets and the elimination of key operatives, while limiting advances to tactical depths to avoid prolonged occupation.[76] Ground forces sustained around 60 fatalities in these clashes, far outnumbered by Hezbollah losses exceeding 2,000 personnel, underscoring the IDF's edge in combined arms coordination against guerrilla tactics. In the West Bank, the IDF launched Operation Iron Wall on January 21, 2025, deploying battalion-sized task forces into northern camps like Jenin to uproot militant networks, marking the largest such campaign since 2002 with raids on over 40 sites and the arrest or neutralization of hundreds of suspects.[77][78] The operation restored access to restricted areas, demolished explosive manufacturing facilities, and displaced temporary populations for security sweeps, achieving operational dominance in refugee camps previously controlled by armed groups.[79][80] By mid-2025, it had significantly reduced attack launches from the region, with minimal IDF ground casualties relative to disrupted threats.[81]Doctrine and Tactics

Foundational Principles

The foundational principles of the Israeli Ground Forces derive from Israel's geopolitical reality as a small nation confronting existential threats from larger coalitions, necessitating an emphasis on qualitative superiority over quantitative parity. This doctrine prioritizes advanced technological integration, superior training, and operational innovation to maintain an edge against adversaries with vast numerical advantages in manpower and territory. Official IDF assessments underscore that such superiority is essential for compensating inherent disadvantages, enabling the Ground Forces to achieve disproportionate outcomes in land-based conflicts despite limited resources.[82][83] Core tenets, as articulated in the IDF's national security framework, revolve around deterrence, early warning, defense, defeating the enemy, and victory. Deterrence relies on credible displays of resolve and capability to dissuade attacks, while early warning systems facilitate intelligence-driven preemption against gathering threats. Defense entails robust border fortifications and rapid response mechanisms, but transitions aggressively to offensive maneuvers, as "only an assault can achieve decisive victory," per strategic guidelines. These principles underpin the Ground Forces' role in shifting from containment to conquest, ensuring conflicts conclude in Israel's favor rather than stalemate.[84][82][85] Preemption is doctrinally validated by empirical precedents like the 1967 Six-Day War, where anticipatory ground and air operations dismantled Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian forces poised for invasion, averting a multi-front assault, and the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which highlighted the perils of reactive defense against surprise Arab coalitions despite initial setbacks. Rapid mobilization of reserve units—capable of expanding active ground strength from approximately 30,000 to over 400,000 personnel within 48-72 hours—forms the operational backbone, allowing swift concentration of forces for survival against encirclement or invasion. This small-nation realism demands unrelenting focus on speed, initiative, and escalation dominance to neutralize threats before they consolidate.[84][82]Evolution in Asymmetric Warfare

Following the 2006 Second Lebanon War, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) ground forces underwent doctrinal shifts to address hybrid threats posed by non-state actors such as Hezbollah, which combined guerrilla tactics with rocket barrages and embedded operations in civilian areas. The conflict exposed limitations in relying on air power alone against dispersed, resilient adversaries, prompting a reevaluation that emphasized combined arms operations, including ground maneuvers to dismantle command structures and weapon caches. This evolution incorporated the Dahiya Doctrine, articulated by then-Northern Command head Gadi Eisenkot in October 2008, which advocated concentrating overwhelming force on dual-use infrastructure supporting militant activities to deter future aggression and prevent rearmament by disrupting logistical and economic bases.[86][87] In subsequent Gaza operations, IDF ground forces applied these principles during limited incursions to target Hamas rocket production and launch sites integrated into urban environments, complementing aerial strikes on power grids and smuggling routes that facilitated rearmament. Operation Cast Lead (December 2008–January 2009) featured ground advances that destroyed manufacturing facilities and stockpiles, contributing to a sharp decline in rocket fire; prior to the operation, Gaza militants launched approximately 2,000 rockets and mortars in 2008, but post-operation rates fell to around 300 annually through 2010. Similarly, in Operation Protective Edge (July–August 2014), ground troops neutralized an estimated two-thirds of Hamas's 10,000-rocket arsenal and key production nodes, yielding a multi-year reduction in launches from thousands pre-operation to minimal incidents until 2021.[88][89][90] These adaptations reflected a causal understanding that sustained pressure on adversaries' support networks—via ground-enabled destruction of dual-use assets—imposes recovery costs exceeding attack benefits, fostering operational pauses for IDF reconsolidation. Empirical data from post-operation periods confirm diminished threat levels, with rocket fire reductions correlating to degraded militant capabilities rather than voluntary restraint alone, as evidenced by intercepted Hamas communications prioritizing reconstruction over immediate escalation.[91][92]Subterranean and Urban Combat Adaptations

The Israeli Defense Forces' (IDF) Yahalom special engineering unit has spearheaded subterranean combat adaptations since the October 7, 2023, Hamas attacks, focusing on Hamas's estimated 500-800 kilometer Gaza tunnel network used for militant movement, storage, and ambushes. Yahalom, a brigade-sized force dedicated to underground operations, refined tactics for detection via ground-penetrating radar and acoustic sensors, precise mapping with fiber-optic guided robots, and entry-denial through explosive breaching kits tailored for confined spaces. These developments, informed by pre-2023 exercises but accelerated post-invasion, enabled multi-platoon simultaneous entries into tunnel segments, countering the "shape the battlefield from below" advantage insurgents hold by dictating engagement timing.[69][93][94] Neutralization tactics emphasize high-friction methods like controlled demolitions with shaped charges to collapse shafts and galleries, alongside seawater flooding trials initiated in December 2023, which proved effective in inundating isolated tunnel branches and rendering them unusable without full network penetration. By early 2024, these efforts contributed to neutralizing 20-40% of Hamas's subterranean infrastructure, including over 500 of 800 identified tunnels, though challenges persisted from booby-trapped reinforcements and rapid reflooding risks. U.S. Army analyses of IDF operations highlight Yahalom's empirical successes in degrading tunnel utility despite psychological stressors like disorientation and close-quarters threats, informing adaptations such as integrated breather systems and real-time video feeds for safer searches.[95][96][3] Urban combat adaptations integrate subterranean lessons into Gaza's dense, multi-story environments, where tunnels interconnect with booby-trapped buildings, employing non-contiguous battalion boundaries to enable flexible infantry-armor pairings amid rubble. Post-2023 operations in Khan Yunis and Rafah refined "rubblisation" via engineering-led demolitions to expose hidden threats, coupled with drone overwatch for real-time urban mapping, reducing ambush vulnerabilities in hybrid terrains. RUSI assessments note the IDF's emphasis on combined-arms fire support to suppress upper-level fighters during below-ground clears, yielding tactical gains in clearing fortified blocks despite elevated friction from civilian-militant intermingling and improvised explosives. These evolutions, drawn from Gaza and applied to Hezbollah's southern Lebanon tunnels in 2024-2025 cross-border actions, prioritize causal disruption of adversary concealment over minimal-force ideals.[97][98][99]Organization and Structure

Command Hierarchy

The Israeli Ground Forces fall under the unified command of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), with the Chief of the General Staff—a Lieutenant General (Rav Aluf)—serving as the supreme military authority, directly subordinate to the Minister of Defense.[100] The Ground Forces Command (Zro'a HaYabasha), headed by a Major General (Aluf) designated as the General Officer Commanding (GOC), focuses on force buildup, training regimens, doctrinal development, and equipment procurement for ground elements.[101] This role, currently held by Aluf Nadav Lotan as of November 2024, ensures alignment with broader IDF operational needs while maintaining specialized oversight of ground capabilities.[101] Operational decision chains bypass a rigid intermediate layer, routing directly from the General Staff Forum to geographic commands—Northern, Central, Southern, and Edelstein Operational Command—each led by a Major General.[102] These commands integrate Ground Forces maneuvers with joint IDF assets, including air strikes and intelligence from the Air Force and Navy, under the Chief of Staff's centralized authority to enable synchronized multi-domain responses.[84] The structure emphasizes mission command principles, delegating tactical initiative to subordinates while preserving strategic control at the top, which supports decentralized execution in fluid environments.[103] In the crises following October 7, 2023, this hierarchy enabled empirical decision speeds, such as the activation of reserve orders yielding over 120% turnout on the attack day itself, facilitating the assembly of division-sized ground formations for Gaza incursions within weeks despite initial force readiness gaps.[104] Subsequent adaptations, including the 2024 Lebanon ground operations, demonstrated accelerated operational tempo, with forces advancing into enemy territory amid real-time joint coordination to counter Hezbollah disruptions.[105]Combat Units and Formations

The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) Ground Forces organize combat units into brigades and divisions aligned with regional commands, enabling flexible combined arms operations that integrate infantry, armored, and supporting elements for offensive maneuvers and defensive postures. Brigades serve as the primary maneuver units, typically comprising 3,000 to 5,000 personnel with multiple battalions, while divisions coordinate brigade-level actions across theaters, as seen in operations since 2023. This structure supports force multipliers through synergistic tactics, where infantry advances under armored cover to exploit breakthroughs, a doctrine refined in conflicts like the Yom Kippur War but adapted for modern hybrid threats.[106][107] The Infantry Corps oversees five core brigades: the Golani Brigade (1st Brigade), focused on northern border defense and mountain warfare since its 1948 founding; the Paratroopers Brigade (35th Brigade), emphasizing airborne insertions and elite assaults under Central Command; the Nahal Brigade (50th Brigade), oriented toward counter-guerrilla operations and settlement security; the Givati Brigade (42nd Brigade), specialized in southern coastal and urban engagements; and the Kfir Brigade, dedicated to anti-terror raids and counter-insurgency in the West Bank with a focus on urban combat training. These brigades employ light to mechanized infantry, enabling rapid deployment and close-quarters effectiveness, with Golani and Paratroopers often leading high-intensity northern operations.[108][109] Armored brigades provide heavy firepower and mobility, exemplified by the 7th Armored Brigade and 188th Armored Brigade under Northern Command, which integrate tank battalions with reconnaissance and engineering elements for breakthrough operations against fortified positions. Additional armored formations, such as the 401st Brigade, support divisional maneuvers in central and southern sectors, contributing to combined arms superiority by shielding infantry advances and disrupting enemy armor concentrations, as demonstrated in Gaza incursions from 2023 onward.[110] Divisions aggregate these brigades for theater-level control; for instance, the 36th Division pairs infantry brigades like Golani and Givati with armored assets for multi-brigade offensives, while the 99th Division in Gaza coordinates the Northern Gaza Brigade, 646th Brigade, and 990th Brigade for sustained urban clearing operations as of July 2025. The 162nd Division similarly integrates reserve armored and infantry units for southern theaters, enhancing operational depth through layered command. Recent expansions post-October 2023 include reserve divisions bolstering Lebanon and Jordan borders with dedicated brigades for rapid response.[106][111] Elite ground forces, such as Sayeret Matkal—the General Staff Reconnaissance Unit—augment conventional units with special reconnaissance, hostage rescue, and deep-strike missions, operating covertly to gather intelligence and disrupt command nodes in enemy rear areas. Though directly under General Staff rather than regional commands, Sayeret Matkal's ground roles integrate with brigade operations for precision targeting, exemplified in cross-border raids, providing asymmetric advantages in intelligence-driven warfare.[112]Support and Specialized Branches

The Combat Engineering Corps, established in 1947, serves as a core enabler for ground maneuver by ensuring mobility through obstacle breaching, minefield clearance, bridge construction, and fortification building under combat conditions.[113] Its units integrate engineering capabilities with infantry tactics to dismantle enemy defenses, deploy counter-mobility measures like mine-laying, and handle explosive ordnance disposal, thereby facilitating armored and infantry advances across varied terrains.[114] In multi-domain operations, the corps has adapted to subterranean threats by incorporating tunnel detection technologies and unmanned ground vehicles for reconnaissance and neutralization.[114] Within the Combat Engineering Corps, the Yahalom special forces unit specializes in high-risk engineering tasks, including precise demolition of structures, sabotage of enemy infrastructure, and counter-tunnel operations using advanced explosives and robotics.[115] Yahalom personnel conduct explosive ordnance disposal, chemical-biological-radiological-nuclear (CBRN) threat mitigation, and breaching of fortified positions, often in coordination with maneuver brigades to enable rapid penetration of defended areas.[116] These capabilities proved critical in operations requiring the destruction of underground networks, with the unit employing specialized tools for locating and collapsing tunnels while minimizing risks to advancing forces.[117] Logistics support for ground forces falls under the IDF's Technological and Logistics Directorate, which manages supply chains, maintenance, and sustainment to sustain prolonged maneuvers, including fuel distribution, ammunition resupply, and vehicle repair in forward areas.[118] Ground-specific logistics units operate embedded within divisions to provide real-time enablers like field workshops and convoy protection, ensuring operational tempo amid multi-front engagements.[119] Recent enhancements include decentralized supply nodes to counter disruptions from asymmetric threats. Field intelligence branches within ground forces, such as operational intelligence units attached to brigades, provide real-time terrain analysis, enemy position mapping, and signals interception to guide engineering and logistics decisions during advances.[120] These enablers integrate with central Military Intelligence Directorate assets for fused data, emphasizing ground-level collection to support breaching and sustainment in denied environments.[121] Border defense units, including dedicated engineering and surveillance formations, fortify perimeter barriers and rapid-response capabilities to deter incursions, with adaptations in 2025 involving expanded deployments along multiple frontiers to address simultaneous threats from Gaza, Lebanon, and Syria.[122] These specialized branches construct anti-tunnel walls, sensor networks, and defensive obstacles, enabling ground forces to maintain interior lines while projecting power outward.[123]Recent Reforms and Expansions (2024-2025)

In April 2024, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) expanded its armored corps by increasing the number of tank companies manned by regular active-duty soldiers, reversing prior reductions in standing tank forces to enhance readiness for prolonged ground operations in Gaza.[124] This adjustment addressed attrition from intense urban combat, where tank units faced high operational tempo and maintenance demands.[124] By December 2024, the IDF established five new reserve brigades, designated the "David Brigades," comprising older reservists aged 38-58 to strengthen border defense and sustain multi-front engagements without over-relying on younger conscripts.[125] These units focused on territorial security, responding to persistent threats from Gaza and Lebanon that depleted existing reserve structures.[125] Announcements in May and June 2025 outlined further expansions, including the reestablishment of armored reconnaissance battalions—dismantled in earlier downsizing efforts—to improve scouting and rapid response in asymmetric warfare environments.[126][127] On June 11, 2025, the IDF detailed structural shifts such as detaching the 261st Brigade from its training role at Bahad 1 to form a dedicated reserve infantry brigade under the 252nd Division, alongside plans for three new regular armored reconnaissance battalions to counter evolving threats from Iran-aligned proxies.[128][127] These reforms prioritized empirical adaptations to battlefield losses, emphasizing scalable combat formations over doctrinal overhauls.[126]Personnel and Service

Conscription, Reserves, and Manpower

Israel's conscription system mandates service for most Jewish citizens, as well as Druze and Circassian males, with Jewish females required to serve unless exempted for religious reasons; this applies across IDF branches, including the Ground Forces, where personnel form the core of combat and support units.[129] Males typically serve 32 months, while females serve 24 months, durations that have remained standard as of 2025 despite proposals in early 2024 to extend combat roles to 36 months for males and 30 months for certain female positions amid heightened threats.[130] [131] This model empirically enhances readiness by producing a steady influx of trained personnel who transition directly into reserves, enabling the IDF to maintain a small active force of approximately 126,000 ground troops while accessing experienced reinforcements rapidly, as demonstrated by the mobilization of over 300,000 reservists within days following the October 7, 2023, attacks.[132] The reserve system requires former conscripts to serve periodic annual training and be available for call-up until ages 40-45 for combat roles and up to 52 for others, forming a pool of roughly 465,000 personnel that constitutes the IDF's primary surge capacity for ground operations.[2] This structure has proven causally effective for deterrence and response, allowing the Ground Forces to scale from peacetime levels to wartime divisions—evidenced by historical mobilizations like the 1973 Yom Kippur War, where reserves expanded active strength by over 100,000 in hours—and recent multi-arena conflicts, where reserve integration sustained prolonged engagements without proportional active-duty expansion.[133] However, ongoing debates in 2025 over extending mandatory reserve duty beyond current limits reflect strains from extended operations, with call-up caps raised to 450,000 to address attrition and fatigue.[134] [135] Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) exemptions, historically granted via full-time yeshiva study and affecting about 13% of Israel's population—a group projected to reach 25% by 2040—impose verifiable strategic costs on Ground Forces manpower by shrinking the eligible recruit pool and concentrating deployment burdens on non-exempt sectors.[136] Although a June 2024 Supreme Court ruling ended blanket exemptions, Haredi enlistment remained minimal in 2025 (fewer than 2,000 annually against targets of 4,800+), leading to documented over-reliance on reserves and active personnel, which erodes sustained readiness as measured by deployment rotation limits and unit cohesion metrics during the 2023-2025 wars.[137] [138] Analysts from institutions like INSS argue this dynamic causally undermines force scalability against multi-front threats, as the conscription model's effectiveness hinges on broad participation to distribute training and experience evenly.[139]Training Regimens and Specialization

Basic training for Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) ground forces combat recruits spans approximately four months, focusing on physical fitness, marksmanship, small-unit tactics, and field survival skills.[140] This foundational phase, conducted at dedicated training bases, includes progressive exercises such as long-distance marches—culminating in a multi-day final march—and a ceremonial swearing-in upon completion.[140] Recruits undergo daily routines emphasizing endurance, with requirements like running 3 kilometers in under 17 minutes for males, alongside strength drills involving push-ups, pull-ups, and heavy load carries.[141] Advanced training follows basic tironut, tailoring regimens to specific ground forces roles such as infantry, armor, or engineering, often extending 6-8 months or more for elite units.[142] Infantry programs incorporate live-fire exercises, navigation in varied terrain, and combined arms simulations, preparing soldiers for high-intensity maneuvers.[143] Specialized courses for combat engineers include explosives handling and obstacle breaching, while armored units emphasize vehicle operations and crew coordination under simulated combat conditions.[142] Post-2014 adaptations intensified focus on urban and subterranean warfare, prompted by Hamas tunnel networks exposed during Operation Protective Edge.[93] The IDF's Yahalom unit, within the Combat Engineering Corps, delivers specialized training in tunnel detection, ventilation mapping, and close-quarters combat in confined spaces, using mock underground facilities replicating Gaza's subterranean systems.[144] Instructors complete a seven-week course on tunnel tactics, enabling brigade-level proficiency in neutralizing threats below ground.[145] Urban combat drills at facilities like the Lotar counter-terrorism school simulate dense environments, integrating breaching, room-clearing, and drone-assisted reconnaissance.[146] These regimens contribute to operational proficiency, evidenced by improved survival outcomes for wounded personnel in 2023 Gaza operations compared to 2014, with higher rates of soldiers returning to duty post-evacuation due to enhanced tactical discipline and medical integration in training.[147] Regular exercises like "Rescue Under Fire" and multi-domain war weeks test adaptations for asymmetric threats, maintaining readiness for multi-front scenarios.[148]Ranks, Uniforms, and Insignia

The Israeli Ground Forces utilize a unified rank system consistent with the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), dividing personnel into commissioned officers, non-commissioned officers (NCOs), and enlisted ranks to maintain hierarchical discipline and command clarity in ground operations. Officer ranks ascend from Segen (Second Lieutenant, equivalent to NATO OF-1) to Rav Aluf (Lieutenant General, OF-9), with insignia featuring gold bars for junior officers (one for Segen, two for Segen Mishne, three for Seren), oak leaves for field-grade officers, and stars within laurel wreaths for general officers (one star for Aluf, two for Tat Aluf, three for Rav Aluf).[149] [150] Enlisted ranks begin at Turai (Private, OR-1) and progress to Rav Samal Rishon (Chief Warrant Officer, OR-8), denoted by chevrons on sleeves: single chevron for Rav Turai (Corporal), multiple angled bars for sergeants (Samal to Rav Samal), and combined bars with chevrons for senior NCOs.[149] [150] This structure, established post-1948 and refined through operational experience, aligns hierarchically with NATO standards while incorporating Hebrew terminology rooted in biblical and historical military traditions, ensuring rapid recognition in multi-branch exercises.[150] Standard uniforms for Ground Forces personnel consist of olive green fatigues, selected for durability, cost-effectiveness, and high visibility in urban and mixed-unit environments prevalent in Israeli operations, where distinguishing friendly forces amid civilian settings reduces fratricide risks.[151] [152] Headgear includes unit-specific berets—brown for infantry, black for armored corps, and maroon for paratroopers—secured with corps pins (e.g., crossed rifles for infantry), while shoulder tabs in colored cloth denote branches like logistics (blue) or engineering (red) for identification during joint maneuvers.[153] [151] Uniform evolutions have been incremental; post-2000 conflicts prompted additions like flame-resistant fabrics and modular vests, but trials of multi-terrain digital camouflage patterns in 2018–2019 were halted in favor of retaining solid olive due to logistical simplicity and empirical effectiveness in close-quarters combat, as validated by field tests emphasizing uniformity over adaptive patterning.[154] [152]| Category | Rank (English/Hebrew) | NATO Equivalent | Insignia Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Officers | Second Lieutenant / Segen | OF-1 | One gold bar on shoulder |

| Officers | First Lieutenant / Segen Mishne | OF-1 | Two gold bars on shoulder |

| Officers | Captain / Seren | OF-2 | Three gold bars on shoulder |

| Officers | Major / Rav Seren | OF-3 | Single gold oak leaf |

| Officers | Lieutenant Colonel / Sgan Aluf | OF-4 | Two gold oak leaves |

| Officers | Colonel / Aluf Mishne | OF-5 | Silver star in laurel wreath |

| Officers | Brigadier General / Aluf | OF-6 | One silver star in laurel wreath |

| Officers | Major General / Tat Aluf | OF-7 | Two silver stars in laurel wreath |

| Officers | Lieutenant General / Rav Aluf | OF-9 | Three silver stars in laurel wreath |

| Enlisted/NCO | Private / Turai | OR-1 | No insignia |

| Enlisted/NCO | Corporal / Rav Turai | OR-3 | Single chevron |

| Enlisted/NCO | Sergeant / Samal | OR-4 | Two angled bars |

| Enlisted/NCO | Staff Sergeant / Rav Samal | OR-6 | Three angled bars |

| Enlisted/NCO | Master Sergeant / Rav Samal Rishon | OR-8 | Bars with chevrons |

.svg/250px-IDF_GOC_Army_Headquarters_From_2020_(Alternative).svg.png)

.svg/1994px-IDF_GOC_Army_Headquarters_From_2020_(Alternative).svg.png)