Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Korean language

View on Wikipedia

| Korean | |

|---|---|

| 한국어 (Hanguk-eo) (South Korea) 조선어 (Chosŏnŏ) (North Korea) | |

Hangugeo written (left) vertically in Korean alphabet for South Korean and Chosŏnŏ written (right) for North Korean when referring to the language | |

| Region | Korea |

| Ethnicity | Koreans, formerly Jaegaseung |

Native speakers | 81 million (2019–2022)[1] |

Koreanic

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects | See Korean dialects |

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ko |

| ISO 639-2 | kor |

| ISO 639-3 | kor |

| Glottolog | kore1280 |

| Linguasphere | 45-AAA-a |

| |

| South Korean name | |

| Hangul | 한국어 |

| Hanja | 韓國語 |

| Revised Romanization | Hangugeo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Han'gugŏ |

| IPA | [ha(ː)n.ɡu.ɡʌ] |

| North Korean name | |

| Chosŏn'gŭl | 조선어 |

| Hancha | 朝鮮語 |

| Revised Romanization | Joseoneo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chosŏnŏ |

| IPA | [tso.sɔ.nɔ][3][4] |

Korean is the native language for about 81 million people, mostly of Korean descent.[a] It is the national language of both North Korea and South Korea. In the south, the language is known as Hangugeo (South Korean: 한국어) and in the north, it is known as Chosŏnŏ (North Korean: 조선어).[4] Since the turn of the 21st century, aspects of Korean popular culture have spread around the world through globalization and cultural exports.[5]

Beyond Korea, the language is recognized as a minority language in parts of China, namely Jilin, and specifically Yanbian Prefecture, and Changbai County. It is also spoken by Sakhalin Koreans in parts of Sakhalin, the Russian island just north of Japan, and by the Koryo-saram in parts of Central Asia.[6] The language has a few extinct relatives which—along with the Jeju language (Jejuan) of Jeju Island and Korean itself—form the compact Koreanic language family. Even so, Jejuan and Korean are not mutually intelligible. The linguistic homeland of Korean is suggested to be somewhere in contemporary Manchuria.[6] The hierarchy of the society from which the language originates deeply influences the language, leading to a system of speech levels and honorifics indicative of the formality of any given situation.

Modern Korean is written in the Korean script (한글; Hangeul in South Korea, 조선글; Chosŏn'gŭl in North Korea), an alphabet system developed during the 15th century for that purpose, although it did not become the primary script until the mid 20th century (Hanja and mixed script were the primary script until then).[7] The script uses 24 basic letters (jamo) and 27 complex letters formed from the basic ones.

Interest in Korean language acquisition (as a foreign language) has been generated by longstanding alliances, military involvement, and diplomacy, such as between South Korea–United States and China–North Korea since the end of World War II and the Korean War. Along with other languages such as Chinese and Arabic, Korean is ranked at the top difficulty level for English speakers by the United States Department of Defense.

History

[edit]Modern Korean descends from Middle Korean, which in turn descends from Old Korean, which descends from the Proto-Koreanic language, which is generally suggested to have its linguistic homeland somewhere in Manchuria.[8][9] Whitman (2012) suggests that the proto-Koreans, already present in northern Korea, expanded into the southern part of the Korean Peninsula at around 300 BC and coexisted with the descendants of the Japonic Mumun cultivators (or assimilated them). Both had influence on each other and a later founder effect diminished the internal variety of both language families.[10]

Since the establishment of two independent governments, North–South differences have developed in standard Korean, including variations in pronunciation and vocabulary chosen. While there tends to be strong political conflict between North and South Korea regarding these linguistic "differences," regional dialects within each country actually display greater linguistic variations than those found between North and South Korean standards. Nevertheless, these dialects remain largely mutually intelligible.

Writing systems

[edit]

The Chinese language, written with Chinese characters and read with Sino-Xenic pronunciations, was first introduced to Korea in the 1st century BC, and remained the medium of formal writing and government until the late 19th century.[11] Korean scholars adapted Chinese characters (known in Korean as Hanja) to write their own language, creating scripts known as idu, hyangchal, gugyeol, and gakpil.[12][13] These systems were cumbersome, due to the fundamental disparities between the Korean and Chinese languages, and accessible only to those educated in classical Chinese. Most of the population was illiterate.[citation needed]

In the 15th century King Sejong the Great personally developed an alphabetic featural writing system, known today as Hangul, to promote literacy among the common people.[14][15][16] Introduced in the document Hunminjeongeum, it was called eonmun ('colloquial script') and quickly spread nationwide to increase literacy in Korea.

The Korean alphabet was denounced by the yangban aristocracy, who looked down upon it for being too easy to learn.[17][18] However, it gained widespread use among the common class[19] and was widely used to print popular novels which were enjoyed by the common class.[20] Since few people could understand official documents written in classical Chinese, Korean kings sometimes released public notices entirely written in Hangul as early as the 16th century for all Korean classes, including uneducated peasants and slaves. By the 17th century, the yangban had exchanged Hangul letters with slaves, which suggests a high literacy rate of Hangul during the Joseon era.[21]

In the context of growing Korean nationalism in the 19th century, the Kabo Reform of 1894 abolished the Confucian examinations and decreed that government documents would be issued in Hangul instead of literary Chinese.[22][23] Some newspapers were published in Hangul, but other publications used Korean mixed script, with Hanja for Sino-Korean vocabulary and Hangul for other elements.[24] North Korea abolished Hanja in writing in 1949, but continues to teach them in schools.[24] Their usage in South Korea is mainly reserved for specific circumstances such as newspapers, scholarly papers and disambiguation. Today Hanja is largely unused in everyday life but is still important for historical and linguistic studies.[citation needed]

Names

[edit]The Korean names for the language are based on the names for Korea used in both South Korea and North Korea. The English word "Korean" is derived from Goryeo, which is thought to be the first Korean dynasty known to Western nations. Korean people in the former USSR refer to themselves as Koryo-saram or Koryo-in (literally, 'Koryo/Goryeo people'), and call the language Koryo-mar. Some older English sources also use the spelling "Corea" to refer to the nation, and its inflected form for the language, culture and people, "Korea" becoming more popular in the late 1800s.[25]

In South Korea the Korean language is referred to by many names including hangugeo ('Korean language'), hangungmal ('Korean speech') and urimal ('our language'); "hanguk" is taken from the name of the Korean Empire (대한제국; 大韓帝國; Daehan Jeguk). The "han" (韓) in Hanguk and Daehan Jeguk is derived from Samhan, in reference to the Three Kingdoms of Korea (not the ancient confederacies in the southern Korean Peninsula),[26][27] while "-eo" and "-mal" mean "language" and "speech", respectively. Korean is also simply referred to as gugeo, literally "national language". This name is based on the same Han characters (國語 'nation' + 'language') that are also used in Taiwan and Japan to refer to their respective national languages.[citation needed]

In North Korea and China, the language is most often called Joseonmal, or more formally, Joseoneo. This is taken from the North Korean name for Korea (Joseon), a name retained from the Joseon period until the proclamation of the Korean Empire, which in turn was annexed by the Empire of Japan.[citation needed]

In mainland China, following the establishment of diplomatic relations with South Korea in 1992, the term Cháoxiǎnyǔ or the short form Cháoyǔ has normally been used to refer to the standard language of North Korea and Yanbian, whereas Hánguóyǔ or the short form Hányǔ is used to refer to the standard language of South Korea.[citation needed][28]

Classification

[edit]Korean is a member of the Koreanic family along with the Jeju language. Some linguists have included it in the Altaic family, but the core Altaic proposal itself has lost most of its prior support.[29] The Khitan language has several vocabulary items similar to Korean that are not found in other Mongolian or Tungusic languages, suggesting a Korean influence on Khitan.[30]

The hypothesis that Korean could be related to Japanese has had some supporters due to some overlap in vocabulary and similar grammatical features that have been elaborated upon by such researchers as Samuel E. Martin[31] and Roy Andrew Miller.[32] Sergei Starostin (1991) found about 25% of potential cognates in the Japanese–Korean 100-word Swadesh list.[33] Some linguists concerned with the issue between Japanese and Korean, including Alexander Vovin, have argued that the indicated similarities are not due to any genetic relationship, but rather to a sprachbund effect and heavy borrowing, especially from Ancient Korean into Western Old Japanese.[34] A good example might be Middle Korean sàm and Japanese asá, meaning 'hemp'.[35] This word seems to be a cognate, but although it is well attested in Western Old Japanese and Northern Ryukyuan languages, in Eastern Old Japanese it only occurs in compounds, and it is only present in three dialects of the Southern Ryukyuan language group. Also, the doublet wo meaning 'hemp' is attested in Western Old Japanese and Southern Ryukyuan languages. It is thus plausible to assume a borrowed term.[36]

Hudson & Robbeets (2020) suggested that there are traces of a pre-Nivkh substratum in Korean. According to the hypothesis, ancestral varieties of Nivkh (also known as Amuric) were once distributed on the Korean Peninsula before the arrival of Koreanic speakers.[37]

Phonology

[edit]구매자는 판매자에게 제품 대금으로 20달러를 지급하여야 한다.

gumaejaneun panmaejaege jepum daegeumeuro isip dalleoreul ($20) jigeuphayeoya handa.

"The buyer must pay the seller $20 for the product."

lit. [the buyer] [to the seller] [the product] [in payment] [twenty dollars] [have to pay] [do]

Korean syllable structure is (C)(G)V(C), consisting of an optional onset consonant, glide /j, w, ɰ/ and final coda /p, t, k, m, n, ŋ, l/ surrounding a core vowel.

Consonants

[edit]| Bilabial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | ㅁ /m/ | ㄴ /n/ | ㅇ /ŋ/[A] | |||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

plain | ㅂ /p/ | ㄷ /t/ | ㅈ /t͡s/ or /t͡ɕ/ | ㄱ /k/ | |

| tense | ㅃ /p͈/ | ㄸ /t͈/ | ㅉ /t͡s͈/ or /t͡ɕ͈/ | ㄲ /k͈/ | ||

| aspirated | ㅍ /pʰ/ | ㅌ /tʰ/ | ㅊ /t͡sʰ/ or /t͡ɕʰ/ | ㅋ /kʰ/ | ||

| Fricative | plain | ㅅ /s/ or /ɕ/ | ㅎ /h/ | |||

| tense | ㅆ /s͈/ or /ɕ͈/ | |||||

| Approximant | /w/[B] | /j/[B] | ||||

| Liquid | ㄹ /l/ or /ɾ/ | |||||

Assimilation and allophony

[edit]The IPA symbol ⟨◌͈⟩ (U+0348 ◌͈ COMBINING DOUBLE VERTICAL LINE BELOW) is used to denote the tensed consonants /p͈/, /t͈/, /k͈/, /t͡ɕ͈/, /s͈/. Its official use in the extensions to the IPA is for "strong" articulation, but is used in the literature for faucalized voice. The Korean consonants also have elements of stiff voice, but it is not yet known how typical this is of faucalized consonants. They are produced with a partially constricted glottis and additional subglottal pressure in addition to tense vocal tract walls, laryngeal lowering, or other expansion of the larynx.

/s/ is aspirated [sʰ] and becomes an alveolo-palatal [ɕʰ] before [j] or [i] for most speakers (but see North–South differences in the Korean language). This occurs with the tense fricative and all the affricates as well. At the end of a syllable, /s/ changes to /t/ (example: beoseot (버섯) 'mushroom').

/h/ may become a bilabial [ɸ] before [o] or [u], a palatal [ç] before [j] or [i], a velar [x] before [ɯ], a voiced [ɦ] between voiced sounds, and a [h] elsewhere.

/p, t, t͡ɕ, k/ become voiced [b, d, d͡ʑ, ɡ] between voiced sounds.

/m, n/ frequently denasalize at the beginnings of words.

/l/ becomes alveolar flap [ɾ] between vowels, and [l] or [ɭ] at the end of a syllable or next to another /l/. A written syllable-final 'ㄹ', when followed by a vowel or a glide (i.e., when the next character starts with 'ㅇ'), migrates to the next syllable and thus becomes [ɾ].

Traditionally, /l/ was disallowed at the beginning of a word. It disappeared before [j], and otherwise became /n/. However, the inflow of western loanwords changed the trend, and now word-initial /l/ (mostly from English loanwords) are pronounced as a free variation of either [ɾ] or [l].

All obstruents (plosives, affricates, fricatives) at the end of a word are pronounced with no audible release, [p̚, t̚, k̚].

Plosive sounds /p, t, k/ become nasals [m, n, ŋ] before nasal sounds.

Hangul spelling does not reflect these assimilatory pronunciation rules, but rather maintains the underlying, partly historical morphology. Given this, it is sometimes hard to tell which actual phonemes are present in a certain word.

The traditional prohibition of word-initial /ɾ/ became a morphological rule called "initial law" (두음법칙) in the pronunciation standards of South Korea, which pertains to Sino-Korean vocabulary. Such words retain their word-initial /ɾ/ in the pronunciation standards of North Korea. For example,

- "labor" (勞動) – north: rodong (로동), south: nodong (노동)

- "history" (歷史) – north: ryeoksa (력사), south: yeoksa (역사)

- "female" (女子) – north: nyeoja (녀자), south: yeoja (여자)

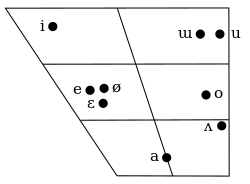

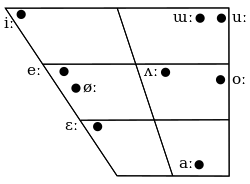

Vowels

[edit]

The standard Korean monophthongs and their pronunciation principles[38] are as follows:

| Monophthongs | ㅏ /a/[A] ㅓ /ʌ/ or /ə/[B] ㅗ /o/ ㅜ /u/ ㅡ /ɯ/ ㅣ /i/ /e/ ㅔ, /ɛ/ ㅐ, /ø/ ㅚ, /y/ ㅟ |

|---|---|

| Vowels preceded by intermediaries, or diphthongs |

ㅑ /ja/ ㅕ /jʌ/ or /jə/ ㅛ /jo/ ㅠ /ju/ /je/ ㅖ, /jɛ/ ㅒ, /we/ ㅞ, /wɛ/ ㅙ, /wa/ ㅘ, /ɰi/ ㅢ, /wʌ/ ㅝ |

^[A] ㅏ is closer to a near-open central vowel ([ɐ]), though ⟨a⟩ is still used for tradition.

^[B] ㅓ is generally pronounced as [ə] when it becomes a long vowel.

However, in Korea, with the exception of older generations in certain regions, most people neither pronounce nor distinguish clearly between the two monophthongs 'ㅐ' (ae) and 'ㅔ' (e). Similarly, 'ㅟ' and 'ㅚ' are sometimes pronounced as [wi] and [we] respectively.[38] The demographic that maintains monophthongal realizations of 'ㅟ' and 'ㅚ' is reportedly limited to elderly speakers in the Gyeonggi, Gangwon, and Chungcheong provinces. The official standard pronunciation guidelines acknowledge this variation by permitting both monophthongal and diphthongal pronunciations of these vowels.[39]

In South Korea, while the distinction between long and short vowels is not clearly pronounced in contemporary speech, this distinction is maintained in standard language norms for reasons of tradition and semantic differentiation.[38]

Morphophonemics

[edit]Grammatical morphemes may change shape depending on the preceding sounds. Examples include -eun/-neun (-은/-는) and -i/-ga (-이/-가).

Sometimes sounds may be inserted instead. Examples include -eul/-reul (-을/-를), -euro/-ro (-으로/-로), -eseo/-seo (-에서/-서), -ideunji/-deunji (-이든지/-든지) and -iya/-ya (-이야/-야).

- However, -euro/-ro is somewhat irregular, since it will behave differently after a ㄹ (rieul consonant).

| After a consonant | After a ㄹ (rieul) | After a vowel |

|---|---|---|

| -ui (-의) | ||

| -eun (-은) | -neun (-는) | |

| -i (-이) | -ga (-가) | |

| -eul (-을) | -reul (-를) | |

| -gwa (-과) | -wa (-와) | |

| -euro (-으로) | -ro (-로) | |

Some verbs may also change shape morphophonemically.

Grammar

[edit]Korean is an agglutinative language. The Korean language is traditionally considered to have nine parts of speech. Modifiers generally precede the modified words, and in the case of verb modifiers, can be serially appended. The sentence structure or basic form of a Korean sentence is subject–object–verb (SOV), but the verb is the only required and immovable element and word order is highly flexible, as in many other agglutinative languages.

Question

가게에

gage-e

store-LOC

가셨어요?

ga-syeoss-eo-yo

go-HON.PAST-CONJ-POL

'Did [you] go to the store?'

Response

예/네.

ye/ne

AFF

'yes.'

The relationship between a speaker/writer and their subject and audience is paramount in Korean grammar. The relationship between the speaker/writer and subject referent is reflected in honorifics, whereas that between speaker/writer and audience is reflected in speech level.

Honorifics

[edit]When talking about someone superior in status, a speaker or writer usually uses special nouns or verb endings to indicate the subject's superiority. Generally, someone is superior in status if they are an older relative, a stranger of roughly equal or greater age, or an employer, teacher, customer, or the like. Someone is equal or inferior in status if they are a younger stranger, student, employee, or the like. Nowadays, there are special endings which can be used on declarative, interrogative, and imperative sentences, and both honorific or normal sentences.

Honorifics in traditional Korea were strictly hierarchical. The caste and estate systems possessed patterns and usages much more complex and stratified than those used today. The intricate structure of the Korean honorific system flourished in traditional culture and society. Honorifics in contemporary Korea are now used for people who are psychologically distant. Honorifics are also used for people who are superior in status, such as older people, teachers, and employers.[40]

Speech levels

[edit]There are seven verb paradigms or speech levels in Korean, and each level has its own unique set of verb endings which are used to indicate the level of formality of a situation.[41] Unlike honorifics—which are used to show respect towards the referent (the person spoken of)—speech levels are used to show respect towards a speaker's or writer's audience (the person spoken to). The names of the seven levels are derived from the non-honorific imperative form of the verb 하다 (hada, "do") in each level, plus the suffix 체 (che, Hanja: 體), which means "style".

The three levels with high politeness (very formally polite, formally polite, casually polite) are generally grouped together as jondaesmal (존댓말), whereas the two levels with low politeness (formally impolite, casually impolite) are banmal (반말) in Korean. The remaining two levels (neutral formality with neutral politeness, high formality with neutral politeness) are neither polite nor impolite.

Nowadays, younger-generation speakers no longer feel obligated to lower their usual regard toward the referent. It is common to see younger people talk to their older relatives with banmal. This is not out of disrespect, but instead it shows the intimacy and the closeness of the relationship between the two speakers. Transformations in social structures and attitudes in today's rapidly changing society have brought about change in the way people speak.[40][page needed]

Gender

[edit]In general, Korean lacks grammatical gender. As one of the few exceptions, the third-person singular pronoun has two different forms: 그 geu (male) and 그녀 geunyeo (female). Before 그녀 was invented in need of translating 'she' into Korean, 그 was the only third-person singular pronoun and had no grammatical gender. Its origin causes 그녀 never to be used in spoken Korean but appearing only in writing.

To have a more complete understanding of the intricacies of gender in Korean, three models of language and gender that have been proposed: the deficit model, the dominance model, and the cultural difference model. In the deficit model, male speech is seen as the default, and any form of speech that diverges from that norm (female speech) is seen as lesser than. The dominance model sees women as lacking in power due to living within a patriarchal society. The cultural difference model proposes that the difference in upbringing between men and women can explain the differences in their speech patterns. It is important to look at the models to better understand the misogynistic conditions that shaped the ways that men and women use the language. Korean's lack of grammatical gender makes it different from most European languages. Rather, gendered differences in Korean can be observed through formality, intonation, word choice, etc.[42]

However, one can still find stronger contrasts between genders within Korean speech. Some examples of this can be seen in: (1) the softer tone used by women in speech; (2) a married woman introducing herself as someone's mother or wife, not with her own name; (3) the presence of gender differences in titles and occupational terms (for example, a sajang is a company president, and yŏsajang is a female company president); (4) females sometimes using more tag questions and rising tones in statements, also seen in speech from children.[43]

Between two people of asymmetric status in Korean society, people tend to emphasize differences in status for the sake of solidarity. Koreans prefer to use kinship terms, rather than any other terms of reference.[44] In traditional Korean society, women have long been in disadvantaged positions. Korean social structure traditionally was a patriarchically dominated family system that emphasized the maintenance of family lines. That structure has tended to separate the roles of women from those of men.[45]

Cho and Whitman (2019) explore how categories such as male and female and social context influence Korean's features. For example, they point out that usage of jagi (자기 you) is dependent on context. Among middle-aged women, jagi is used to address someone who is close to them, while young Koreans use jagi to address their lovers or spouses regardless of gender.

Korean society's prevalent attitude towards men being in public (outside the home) and women living in private still exists today. For instance, the word for husband is bakkannyangban (바깥양반 'outside nobleman'), but a husband introduces his wife as ansaram (안사람 an 'inside' 'person'). Also in kinship terminology, oe (외 'outside' or 'wrong') is added for maternal grandparents, creating oeharabeoji and oehalmeoni (외할아버지, 외할머니 'grandfather and grandmother'), with different lexicons for males and females and patriarchal society revealed. Further, in interrogatives to an addressee of equal or lower status, Korean men tend to use haennya (했냐? 'did it?')' in aggressive masculinity, but women use haenni (했니? 'did it?')' as a soft expression.[46] However, there are exceptions. Korean society used the question endings -ni (니) and -nya (냐), the former prevailing among women and men until a few decades ago. In fact, -nya (냐) was characteristic of the Jeolla and Chungcheong dialects. However, since the 1950s, large numbers of people have moved to Seoul from Chungcheong and Jeolla, and they began to influence the way men speak. Recently, women also have used the -nya (냐). As for -ni (니), it is usually used toward people to be polite even to someone not close or younger. As for -nya (냐), it is used mainly to close friends regardless of gender.

Like the case of "actor" and "actress", it also is possible to add a gender prefix for emphasis: biseo (비서 'secretary') is sometimes combined with yeo (여 'female') to form yeobiseo (여비서 'female secretary'); namja (남자 'man') often is added to ganhosa (간호사 'nurse') to form namja ganhosa (남자 간호사 'male nurse').[47]

Another crucial difference between men and women is the tone and pitch of their voices and how they affect the perception of politeness. Men learn to use an authoritative falling tone; in Korean culture, a deeper voice is associated with being more polite. In addition to the deferential speech endings being used, men are seen as more polite as well as impartial, and professional. While women who use a rising tone in conjunction with -yo (요) are not perceived to be as polite as men. The -yo (요) also indicates uncertainty since the ending has many prefixes that indicate uncertainty and questioning while the deferential ending has no prefixes to indicate uncertainty. The -hamnida (합니다) ending is the most polite and formal form of Korea, and the -yo (요) ending is less polite and formal, which reinforces the perception of women as less professional.[46][48]

Hedges and euphemisms to soften assertions are common in women's speech. Women traditionally add nasal sounds neyng, neym, ney-e in the last syllable more frequently than men. Often, l is added in women's for female stereotypes and so igeolo (이거로 'this thing') becomes igeollo (이걸로 'this thing') to communicate a lack of confidence and passivity.[40][page needed]

Women use more linguistic markers such as exclamation eomeo (어머 'oh') and eojjeom (어쩜 'what a surprise') than men do in cooperative communication.[46]

Vocabulary

[edit]

The core of the Korean vocabulary is made up of native Korean words. However, a significant proportion of the vocabulary, especially words that denote abstract ideas, are Sino-Korean words.[49] To a much lesser extent, some words have also been borrowed from Mongolian and other languages.[50] More recent loanwords are dominated by English.

In South Korea, it is widely believed that North Korea wanted to emphasize the use of unique Korean expressions in its language and eliminate the influence of foreign languages. However, according to researchers such as Jeon Soo-tae, who has seen first-hand data from North Korea, the country has reduced the number of difficult foreign words in a similar way to South Korea.[51]

In 2021, Moon Sung-guk of Kim Il Sung University in North Korea wrote in his thesis that Kim Jong Il had said that vernacularized Sino-Korean vocabulary should be used as it is, not modified. "A language is in constant interaction with other languages, and in the process it is constantly being developed and enriched," he said. According to the paper, Kim Jong Il argued that academic terms used in the natural sciences and engineering, such as 콤퓨터 (k'omp'yut'ŏ; 'computer') and 하드디스크 (hadŭdisŭk'ŭ; 'hard disk') should remain in the names of their inventors, and that the word 쵸콜레트 (ch'ok'ollet'ŭ; 'chocolate') should not be replaced because it had been used for so long.[52]

South Korea defines its vocabulary standards through the 표준국어대사전 (Standard Korean Language Dictionary), and North Korea defines its vocabulary standards through the 조선말대사전 (Korean Language Dictionary).

Sino-Korean

[edit]| Number | Sino-Korean cardinal numbers | Native Korean cardinal numbers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangul | Hanja | Romanization | Hangul | Romanization | |

| 1 | 일 | 一 | il | 하나 | hana |

| 2 | 이 | 二 | i | 둘 | dul |

| 3 | 삼 | 三 | sam | 셋 | set |

| 4 | 사 | 四 | sa | 넷 | net |

| 5 | 오 | 五 | o | 다섯 | daseot |

| 6 | 육, 륙 | 六 | yuk, ryuk | 여섯 | yeoseot |

| 7 | 칠 | 七 | chil | 일곱 | ilgop |

| 8 | 팔 | 八 | pal | 여덟 | yeodeol |

| 9 | 구 | 九 | gu | 아홉 | ahop |

| 10 | 십 | 十 | sip | 열 | yeol |

Sino-Korean vocabulary consists of:

- words directly borrowed from written Chinese, and

- compounds coined in Korea or Japan and read using the Sino-Korean reading of Chinese characters.

Therefore, just like other words, Korean has two sets of numeral systems. English is similar, having native English words and Latinate equivalents such as water-aqua, fire-flame, sea-marine, two-dual, sun-solar, star-stellar. However, unlike English and Latin which belong to the same Indo-European languages family and bear a certain resemblance, Korean and Chinese are genetically unrelated and the two sets of Korean words differ completely from each other. All Sino-Korean morphemes are monosyllabic as in Chinese, whereas native Korean morphemes can be polysyllabic. The Sino-Korean words were deliberately imported alongside corresponding Chinese characters for a written language and everything was supposed to be written in Hanja, so the coexistence of Sino-Korean would be more thorough and systematic than that of Latinate words in English.

The exact proportion of Sino-Korean vocabulary is a matter of debate. Sohn (2001) stated 50–60%.[49] In 2006 the same author gives an even higher estimate of 65%.[53] Jeong Jae-do, one of the compilers of the dictionary Urimal Keun Sajeon, asserts that the proportion is not so high. He points out that Korean dictionaries compiled during the colonial period include many unused Sino-Korean words. In his estimation, the proportion of Sino-Korean vocabulary in the Korean language might be as low as 30%.[54]

Western loanwords

[edit]The vast majority of loanwords other than Sino-Korean come from modern times, approximately 90% of which are from English.[49] Many words have also been borrowed from Western languages such as German via Japanese (e.g. 아르바이트 (areubaiteu) 'part-time job', 알레르기 (allereugi) 'allergy', 기브스 (gibseu or gibuseu) 'plaster cast used for broken bones'). Some Western words were borrowed indirectly via Japanese during the Japanese occupation of Korea, taking a Japanese sound pattern, for example "dozen" > ダース dāsu > 다스 daseu. However, most indirect Western borrowings are now written according to current "Hangulization" rules for the respective Western language, as if borrowed directly. In South Korean official use, a number of other Sino-Korean country names have been replaced with phonetically oriented "Hangeulizations" of the countries' endonyms or English names.[55]

Because of such a prevalence of English in modern South Korean culture and society, lexical borrowing is inevitable. English-derived Korean, or "Konglish" (콩글리시), is increasingly used. The vocabulary of the South Korean dialect of the Korean language is roughly 5% loanwords (excluding Sino-Korean vocabulary).[56] However, due to North Korea's isolation, such influence is lacking in North Korean speech.

Writing system

[edit]

Modern Korean is written with an alphabet script, known as Hangul in South Korea and Chosŏn'gŭl in North Korea. The Korean mixed script, combining Hanja and Hangul, is still used to a certain extent in South Korea, but that method is slowly declining in use even though students learn Hanja in school.[57]

Below are charts of the letters of the Korean alphabet and their Revised Romanization (RR) and canonical International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) values:

| Hangul | ㄱ | ㄲ | ㄴ | ㄷ | ㄸ | ㄹ | ㅁ | ㅂ | ㅃ | ㅅ | ㅆ | ㅇ | ㅈ | ㅉ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅌ | ㅍ | ㅎ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | g | kk | n | d | tt | r (initial), l (final) | m | b | pp | s | ss | silent (initial), ng (final) | j | jj | ch | k | t | p | h |

| IPA | k | k͈ | n | t | t͈ | ɾ (initial), l (final) | m | p | p͈ | s | s͈ | ∅ (initial), ŋ (final) | t͡ɕ | t͡ɕ͈ | t͡ɕʰ | kʰ | tʰ | pʰ | h |

| Hangul | ㅣ | ㅔ | ㅚ | ㅐ | ㅏ | ㅗ | ㅜ | ㅓ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅖ | ㅒ | ㅑ | ㅛ | ㅠ | ㅕ | ㅟ | ㅞ | ㅙ | ㅘ | ㅝ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | i | e | oe | ae | a | o | u | eo | eu | ui | ye | yae | ya | yo | yu | yeo | wi | we | wae | wa | wo |

| IPA | i | e | ∅, we | ɛ | a | o | u | ʌ | ɯ | ɰi | je | jɛ | ja | jo | ju | jʌ | ɥi, wi | we | wɛ | wa | wʌ |

The letters of the Korean alphabet are not written linearly like most alphabets, but instead arranged into blocks that represent syllables. So, while the word bibimbap (Korean rice dish) is written as eight characters in a row in the Latin alphabet, in Korean it is written 비빔밥, as three "syllabic blocks" in a row. Mukbang (먹방 'eating show') is seven characters after romanization but only two "syllabic blocks" before.

Modern Korean is written with spaces between words, a feature not found in Chinese or Japanese (except when Japanese is written exclusively in hiragana, as in children's books). The marks used for Korean punctuation are almost identical to Western ones. Traditionally, Korean was written in columns, from top to bottom, right to left, like traditional Chinese. However, the syllabic blocks are now usually written in rows, from left to right, top to bottom, like English.

Dialects

[edit]

Korean has numerous small local dialects (called mal (말; lit. 'speech'), saturi (사투리), or bangeon (방언; 方言)). South Korean authors claim that the standard language (pyojuneo or pyojunmal) of both South Korea and North Korea is based on the dialect of the area around Seoul (which, as Hanyang, was the capital of Joseon-era Korea for 500 years), but since 1966, North Korea officially states that its standard is based on the Pyongyang speech.[58][59] All dialects of Korean are similar to one another and largely are mutually intelligible (with the exception of dialect-specific phrases or nonstandard vocabulary unique to dialects) though the dialect of Jeju Island is divergent enough to be generally considered a separate language.[60][61] The Yukjin dialect in the far northeast is also quite distinctive.[62]

One of the more salient differences between dialects is the use of tone: speakers of the Seoul dialect make use of vowel length, but speakers of the Gyeongsang dialect maintain the pitch accent of Middle Korean. Some dialects are conservative, maintaining Middle Korean sounds (such as z, β, ə), which have been lost from the standard language, and others are highly innovative.

Kang Yoonjung & Han Sungwoo (2013), Kim Mi-Ryoung (2013), and Cho Sunghye (2017) suggest that the modern Seoul dialect is currently undergoing tonogenesis based on the finding that in recent years lenis consonants (ㅂㅈㄷㄱ), aspirated consonants (ㅍㅊㅌㅋ) and fortis consonants (ㅃㅉㄸㄲ) were shifting from a distinction via voice onset time to that of pitch change;[63][64][65] however, Choi Jiyoun, Kim Sahyang & Cho Taehong (2020) disagree with the suggestion that the consonant distinction shifting away from voice onset time is due to the introduction of tonal features, and instead proposes that it is a prosodically conditioned change.[66]

There is substantial evidence for a history of extensive dialect levelling or even convergent evolution or intermixture of two or more originally-distinct linguistic stocks, within the Korean language and its dialects. Many Korean dialects have a basic vocabulary that is etymologically distinct from vocabulary of identical meaning in Standard Korean or other dialects. For example, "garlic chives" translated into Gyeongsang dialect is /t͡ɕʌŋ.ɡu.d͡ʑi/ (정구지; jeongguji), but in Standard Korean, it is /puːt͡ɕʰu/ (부추; buchu). This suggests that the Korean Peninsula may have at one time been much more linguistically diverse than it is today.[67] See also the Japanese–Koreanic languages hypothesis.

North–South differences

[edit]The language used in the North and the South exhibit differences in pronunciation, spelling, grammar and vocabulary.[68]

Pronunciation

[edit]In North Korea, palatalization of /si/ is optional, and /t͡ɕ/ can be pronounced [z] between vowels.

Words that are written the same way may be pronounced differently (such as the examples below). The pronunciations below are given in Revised Romanization, McCune–Reischauer and modified Hangul (what the Korean characters would be if one were to write the word as pronounced).

| Word | RR | Meaning | Pronunciation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | South | |||||||

| RR | MR | Chosŏn'gŭl | RR | MR | Hangul | |||

| 읽고 | ilgo | to read (continuative form) | ilko | ilko | (일)코 | ilkko | ilkko | (일)꼬 |

| 압록강 | amnokgang | Amnok River | amrokgang | amrokkang | 암(록)깡 | amnokkang | amnokkang | 암녹깡 |

| 독립 | dongnip | independence | dongrip | tongrip | 동(립) | dongnip | tongnip | 동닙 |

| 관념 | gwannyeom | idea / sense / conception | gwallyeom | kwallyŏm | 괄렴 | gwannyeom | kwannyŏm | (관)념 |

| 혁신적* | hyeoksinjeok | innovative | hyeoksinjjeok | hyŏksintchŏk | (혁)씬쩍 | hyeoksinjeok | hyŏksinjŏk | (혁)씬(적) |

* In the North, similar pronunciation is used whenever the Hanja "的" is attached to a Sino-Korean word ending in ㄴ, ㅁ or ㅇ.

* In the South, this rule only applies when it is attached to any single-character Sino-Korean word.

Spelling

[edit]Some words are spelled differently by the North and the South, but the pronunciations are the same.

| Word | Meaning | Pronunciation (RR/MR) | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | South spelling | |||

| 해빛 | 햇빛 | sunshine | haeppit (haepit) | The "sai siot" ('ㅅ' used for indicating sound change) is almost never written out in the North. |

| 벗꽃 | 벚꽃 | cherry blossom | beotkkot (pŏtkkot) | |

| 못읽다 | 못 읽다 | cannot read | modikda (modikta) | Spacing. |

| 한나산 | 한라산 | Hallasan | hallasan (hallasan) | When a ㄴㄴ combination is pronounced as ll, the original Hangul spelling is kept in the North, whereas the Hangul is changed in the South. |

| 규률 | 규율 | rules | gyuyul (kyuyul) | In words where the original Hanja is spelt "렬" or "률" and follows a vowel, the initial ㄹ is not pronounced in the North, making the pronunciation identical with that in the South where the ㄹ is dropped in the spelling. |

Spelling and pronunciation

[edit]Basically, the standard languages of North and South Korea, including pronunciation and vocabulary, are both linguistically based on the Seoul dialect, but in North Korea, words have been modified to reflect the theories of scholars like Kim Tu-bong, who sought a refined language, as well as political needs. Some differences are difficult to explain in terms of political ideas, such as North Korea's use of the word rajio (라지오).:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 력량 | ryeongryang (ryŏngryang) | 역량 | yeongnyang (yŏngnyang) | strength | Initial r's are dropped if followed by i or y in the South Korean version of Korean. |

| 로동 | rodong (rodong) | 노동 | nodong (nodong) | work | Initial r's are demoted to an n if not followed by i or y in the South Korean version of Korean. |

| 원쑤 | wonssu (wŏnssu) | 원수 | wonsu (wŏnsu) | mortal enemy | "Mortal enemy" and "field marshal" are homophones in the South. Possibly to avoid referring to Kim Il Sung, Kim Jong Il or Kim Jong Un as the enemy, the second syllable of "enemy" is written and pronounced 쑤 in the North.[69] |

| 라지오 | rajio (rajio) | 라디오 | radio (radio) | radio | In South Korea, the expression rajio is considered a Japanese expression that was introduced during the Japanese colonial rule and does not properly represent the pronunciation of Korean.[70] |

| 우 | u (u) | 위 | wi (wi) | on; above | |

| 안해 | anhae (anhae) | 아내 | anae (anae) | wife | |

| 꾸바 | kkuba (kkuba) | 쿠바 | kuba (k'uba) | Cuba | When transcribing foreign words from languages that do not have contrasts between aspirated and unaspirated stops, North Koreans generally use tensed stops for the unaspirated ones while South Koreans use aspirated stops in both cases. |

| 페 | pe (p'e) | 폐 | pye (p'ye), pe (p'e) | lungs | In the case where ye comes after a consonant, such as in hye and pye, it is pronounced without the palatal approximate. North Korean orthography reflects this pronunciation nuance. |

In general, when transcribing place names, North Korea tends to use the pronunciation in the original language more than South Korea, which often uses the pronunciation in English. For example:

| Original name | North Korea transliteration | English name | South Korea transliteration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spelling | Pronunciation | Spelling | Pronunciation | ||

| Ulaanbaatar | 울란바따르 | ullanbattareu (ullanbattarŭ) | Ulan Bator | 울란바토르 | ullanbatoreu (ullanbat'orŭ) |

| København | 쾨뻰하븐 | koeppenhabeun (k'oeppenhabŭn) | Copenhagen | 코펜하겐 | kopenhagen (k'op'enhagen) |

| al-Qāhirah | 까히라 | kkahira (kkahira) | Cairo | 카이로 | kairo (k'airo) |

Grammar

[edit]Some grammatical constructions are also different:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 되였다 | doeyeotda (toeyŏtta) | 되었다 | doeeotda (toeŏtta) | past tense of 되다 (doeda/toeda), "to become" | All similar grammar forms of verbs or adjectives that end in ㅣ in the stem (i.e. ㅣ, ㅐ, ㅔ, ㅚ, ㅟ and ㅢ) in the North use 여 instead of the South's 어. |

| 고마와요 | gomawayo (komawayo) | 고마워요 | gomawoyo (komawŏyo) | thanks | ㅂ-irregular verbs in the North use 와 (wa) for all those with a positive ending vowel; this only happens in the South if the verb stem has only one syllable. |

| 할가요 | halgayo (halkayo) | 할까요 | halkkayo (halkkayo) | Shall we do? | Although the Hangul differ, the pronunciations are the same (i.e. with the tensed ㄲ sound). |

Punctuation

[edit]In the North, guillemets (《 and 》) are the symbols used for quotes; in the South, quotation marks equivalent to the English ones (" and ") are standard (although 『 』 and 「 」 are also used).

Vocabulary

[edit]Some vocabulary is different between the North and the South:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North word | North pronun. | South word | South pronun. | ||

| 문화주택 | munhwajutaek (munhwajut'aek) | 아파트 | apateu (ap'at'ŭ) | Apartment | 아빠트 (appateu/appat'ŭ) is also used in the North. |

| 조선어 | joseoneo (chosŏnŏ) | 한국어 | hangugeo (han'gugŏ) | Korean language | The Japanese pronunciation of 조선말 was used throughout Korea and Manchuria during Japanese imperial rule, but after liberation, the government in the South chose the name 대한민국 (daehanminguk) which was derived from the name immediately prior to Japanese imperial rule, and claimed by government-in-exile from 1919. The syllable 한 (han) was drawn from the same source as that name (in reference to the Han people). Read more.

조선어 (joseoneo/chosŏnŏ) is officially used in the North. |

| 곽밥 | gwakbap (kwakpap) | 도시락 | dosirak (tosirak) | lunch box | |

| 동무 | dongmu (tongmu) | 친구 | chingu (ch'in'gu) | Friend | 동무 was originally a non-ideological word for "friend" used all over the Korean peninsula, but North Koreans later adopted it as the equivalent of the Communist term of address "comrade". As a result, to South Koreans today the word has a heavy political tinge, and so they have shifted to using other words for friend like chingu (친구) or beot (벗). Today, beot (벗) is closer to a term used in literature, and chingu (친구) is the widest-used word for friend.

Such changes were made after the Korean War and the ideological battle between the anti-Communist government in the South and North Korea's communism.[71][72] |

Geographic distribution

[edit]Korean is spoken by the Korean people in both South Korea and North Korea, and by the Korean diaspora in many countries including the People's Republic of China, the United States, Japan, and Russia. In 2001, Korean was the fourth most popular foreign language in China, following English, Japanese, and Russian.[73] Korean-speaking minorities exist in these states, but because of cultural assimilation into host countries, not all ethnic Koreans may speak it with native fluency.

Official status

[edit]Korean is the official language of South Korea and North Korea. It, along with Mandarin Chinese, is also one of the two official languages of China's Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture.

In North Korea, the regulatory body is the Language Institute of the Academy of Social Sciences (사회과학원 어학연구소; 社會科學院語學硏究所; Sahoegwahagwŏn ŏhagyŏn'guso). In South Korea, the regulatory body for Korean is the Seoul-based National Institute of Korean Language, which was created by presidential decree on 23 January 1991.

King Sejong Institute

[edit]Established pursuant to Article 9, Section 2, of the Framework Act on the National Language, the King Sejong Institute[74] is a public institution set up to coordinate the government's project of propagating Korean language and culture; it also supports the King Sejong Institute, which is the institution's overseas branch. The King Sejong Institute was established in response to:

- An increase in the demand for Korean language education;

- a rapid increase in Korean language education thanks to the spread of the culture (hallyu), an increase in international marriage, the expansion of Korean enterprises into overseas markets, and enforcement of employment licensing system;

- the need for a government-sanctioned Korean language educational institution;

- the need for general support for overseas Korean language education based on a successful domestic language education program.

King Sejong Institute has 59 in Europe, 15 in Africa, 146 in Asia, 34 in the Americas, and 4 in Oceania.[75]

TOPIK Korea Institute

[edit]The TOPIK Korea Institute is a lifelong educational center affiliated with a variety of Korean universities in Seoul, South Korea, whose aim is to promote Korean language and culture, support local Korean teaching internationally, and facilitate cultural exchanges.

The institute is sometimes compared to language and culture promotion organizations such as the King Sejong Institute. Unlike that organization, however, the TOPIK Korea Institute operates within established universities and colleges around the world, providing educational materials. In countries around the world, Korean embassies and cultural centers (한국문화원) administer TOPIK examinations.[76]

Foreign language

[edit]For native English-speakers, Korean is generally considered to be one of the most difficult foreign languages to master despite the relative ease of learning Hangul. For instance, the United States' Defense Language Institute places Korean in Category IV with Japanese, Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese), and Arabic, requiring 64 weeks of instruction (as compared to just 26 weeks for Category I languages like Italian, French, and Spanish) to bring an English-speaking student to a limited working level of proficiency in which they have "sufficient capability to meet routine social demands and limited job requirements" and "can deal with concrete topics in past, present, and future tense."[77][78] Similarly, the Foreign Service Institute's School of Language Studies places Korean in Category IV, the highest level of difficulty.[79]

The study of the Korean language in the United States is dominated by Korean American heritage language students; in 2007, these students were estimated to form over 80% of all students of the language at non-military universities.[80] However, Sejong Institutes in the United States have noted a sharp rise in the number of people of other ethnic backgrounds studying Korean between 2009 and 2011, which they attribute to rising popularity of South Korean music and television shows.[81] In 2018, it was reported that the rise in K-Pop was responsible for the increase in people learning the language in US universities.[82]

Testing

[edit]There are two widely used tests of Korean as a foreign language: the Korean Language Ability Test (KLAT) and the Test of Proficiency in Korean (TOPIK). The Korean Language Proficiency Test, an examination aimed at assessing non-native speakers' competence in Korean, was instituted in 1997; 17,000 people applied for the 2005 sitting of the examination.[83] The TOPIK was first administered in 1997 and was taken by 2,274 people. Since then the total number of people who have taken the TOPIK has surpassed 1 million, with more than 150,000 candidates taking the test in 2012.[84] TOPIK is administered in 45 regions within South Korea and 72 nations outside of South Korea, with a significant portion being administered in Japan and North America, which would suggest the targeted audience for TOPIK is still primarily foreigners of Korean heritage.[85] This is also evident in TOPIK's website, where the examination is introduced as intended for Korean heritage students.

Example text

[edit]From Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Korean (South Korean standard):[86]

모든

Modeun

인간은

inganeun

태어날

taeeonal

때부터

ttaebuteo

자유로우며

jayuroumyeo

그

geu

존엄과

joneomgwa

권리에

gwollie

있어

isseo

동등하다.

dongdeunghada.

인간은

Inganeun

천부적으로

cheonbujeogeuro

이성과

iseonggwa

양심을

yangsimeul

부여받았으며

buyeobadasseumyeo

서로

seoro

형제애의

hyeongjeaeui

정신으로

jeongsineuro

행동하여야

haengdonghayeoya

한다.

handa.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[87]

See also

[edit]- Korean Wave

- Miracle on the Han River

- Outline of Korean language

- Korean count word

- Korean Cultural Center (KCC)

- Korean dialects

- Korean language and computers

- Korean as a foreign language

- Korean mixed script

- Debate on mixed script and Hangul exclusivity

- Korean particles

- Korean proverbs

- Korean words

- Korean sign language

- Korean romanization

- List of English words of Korean origin

- Vowel harmony

- History of Korean

Notes

[edit]- ^ Measured as of 2020. The estimated 2020 combined population of North and South Korea was about 77 million.

References

[edit]- ^ Korean language at Ethnologue (28th ed., 2025)

- ^ a b Samuel E. Martin, Korean language at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Hermann, Winfred (1994). Lehrbuch der Modernen Koreanischen Sprache. Berlin: Buske. p. 26. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b "국가상징" (in Korean). Naenara. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

조선민주주의인민공화국의 국어는 조선어이다.

- ^ legaltranslations (16 March 2020). "The Korean Language: Key Differences Between North and South - Blog". Legal Translations. Retrieved 11 February 2025.

- ^ a b Hölzl, Andreas (29 August 2018). A typology of questions in Northeast Asia and beyond: An ecological perspective. Language Science Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-3-96110-102-3. Archived from the original on 6 November 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (1 January 2004). "Mixed Script and Literacy in Korea". Korean Linguistics. 12 (1): 161–182. doi:10.1075/kl.12.07ykk. ISSN 0257-3784. Retrieved 14 December 2024.

- ^ Janhunen, Juha (2010). "Reconstructing the Language Map of Prehistorical Northeast Asia". Studia Orientalia (108).

... there are strong indications that the neighbouring Baekje state (in the southwest) was predominantly Japonic-speaking until it was linguistically Koreanized.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2013). "From Koguryo to Tamna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean". Korean Linguistics. 15 (2): 222–240. doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.03vov.

- ^ Whitman, John (1 December 2011). "Northeast Asian Linguistic Ecology and the Advent of Rice Agriculture in Korea and Japan". Rice. 4 (3): 149–158. Bibcode:2011Rice....4..149W. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0. ISSN 1939-8433.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 111, 287–288.

- ^ Hannas, Wm C. (1997). Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. University of Hawaii Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- ^ Cho & Whitman (2020), pp. 41–45.

- ^ Koerner, E. F. K.; Asher, R. E. (28 June 2014). Concise History of the Language Sciences: From the Sumerians to the Cognitivists. Elsevier. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4832-9754-5.

- ^ Kim-Renaud, Young-Key (1997). The Korean Alphabet: Its History and Structure. University of Hawaii Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8248-1723-7.

- ^ 알고 싶은 한글 (in Korean). National Institute of Korean Language. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Montgomery, Charles (19 January 2016). "Korean Literature in Translation – Chapter Four: It All Changes! The Creation of Hangul". KTLit. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

Hangul was sometimes known as the "language of the inner rooms," (a dismissive term used partly by yangban in an effort to marginalize the alphabet), or the domain of women.

- ^ Chan, Tak-hung Leo (2003). One into Many: Translation and the Dissemination of Classical Chinese Literature. Rodopi. p. 183. ISBN 978-90-420-0815-1.

- ^ "Korea Newsreview". Korea News Review. Korea Herald, Incorporated. 1 January 1994. Archived from the original on 6 November 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ Lee, Kenneth B. (1997). Korea and East Asia: The Story of a Phoenix. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-275-95823-7.

- ^ "Archive of Joseon's Hangul letters – A letter sent from Song Gyuryeom to slave Guityuk (1692)". Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Cho & Whitman (2020), p. 49.

- ^ "Korean History". Korea.assembly.go.kr. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

Korean Empire, Edict No. 1 – All official documents are to be written in Hangul, and not Chinese characters.

- ^ a b Sohn (2001), p. 145.

- ^ According to Google's NGram English corpus of 2015, "Google Ngram Viewer".

- ^ 이기환 (30 August 2017). [이기환의 흔적의 역사]국호논쟁의 전말…대한민국이냐 고려공화국이냐. Kyunghyang Shinmun (in Korean). Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ 이덕일. [이덕일 사랑] 대~한민국. 조선닷컴 (in Korean). The Chosun Ilbo. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ 朝鲜语规范化取得新成果《朝鲜语规范集》修订本出版发行. Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (in Simplified Chinese). Retrieved 7 September 2025.

- ^ Cho & Whitman (2020), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (June 2017). "Koreanic loanwords in Khitan and their importance in the decipherment of the latter" (PDF). Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 70 (2): 207–215. doi:10.1556/062.2017.70.2.4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Martin (1966), Martin (1990)

- ^ e.g. Miller (1971), Miller (1996)

- ^ Starostin, Sergei (1991). Altaiskaya problema i proishozhdeniye yaponskogo yazika [The Altaic Problem and the Origins of the Japanese Language] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Vovin (2008).

- ^ Whitman (1985), p. 232, also found in Martin (1966), p. 233

- ^ Vovin (2010), pp. 173–174.

- ^ Hudson, Mark J.; Robbeets, Martine (2020). "Archaeolinguistic Evidence for the Farming/Language Dispersal of Koreanic". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2. e52. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.49. PMC 10427439. PMID 37588366.

- ^ a b c 표준어 규정-표준 발음법. 한국어 어문 규범. National Institute of Korean Language. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ 모음체계. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ a b c Sohn (2006).

- ^ Choo, Miho (2008). Using Korean: A Guide to Contemporary Usage. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-139-47139-8.

- ^ Cho (2006), p. 189.

- ^ Cho (2006), pp. 189–198.

- ^ Kim, Minju (1999). "Cross Adoption of language between different genders: The case of the Korean kinship terms hyeng and enni". Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Women and Language Conference. Berkeley: Berkeley Women and Language Group.

- ^ Palley, Marian Lief (December 1990). "Women's Status in South Korea: Tradition and Change". Asian Survey. 30 (12): 1136–1153. doi:10.2307/2644990. JSTOR 2644990.

- ^ a b c Brown (2015).

- ^ Song, Sooho (2022). "Analysis of Gender Pronoun Errors in Korean Speakers' English Speech" (PDF). English Teaching. 77 (1): 7–8. doi:10.15858/engtea.77.1.202203.21. S2CID 247804299. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Cho (2006), pp. 193–195.

- ^ a b c Sohn (2001), Section 1.5.3 "Korean vocabulary", pp. 12–13

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 6.

- ^ 이장균 (17 April 2004). 남북의 언어. Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on 27 April 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ 위대한 령도자 김정일동지께서 어휘정리사업이 편향없이 진행되도록 이끌어주신 불멸의 령도. Archived from the original on 26 December 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Sohn (2006), p. 5.

- ^ Kim, Jin-su (11 September 2009). 우리말 70%가 한자말? 일제가 왜곡한 거라네 [Our language is 70% hanja? Japanese Empire distortion]. The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2009. The dictionary mentioned is 우리말 큰 사전. Seoul: Hangul Hakhoe. 1992. OCLC 27072560.

- ^ Choo, Sungjae (2016). "The use of Hanja (Chinese characters) in Korean toponyms: Practices and issues". Journal of the International Council of Onomastic Sciences. 51: 13–24. doi:10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/2.

- ^ Sohn (2006), p. 87.

- ^ 현판 글씨들이 한글이 아니라 한자인 이유는?. royalpalace.go.kr (in Korean). Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ 전, 영선. 북한 언어문화의 변화양상과 전망 (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ^ Brown, Lucien; Yeon, Jaehoon (2015). The handbook of Korean linguistics (1st ed.). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 477, 484. ISBN 978-1-118-37100-8.

- ^ Yang, Changyong; O'Grady, William; Yang, Sejung; Hilton, Nanna Haug; Kang, Sang-Gu; Kim, So-Young (2019). "Revising the Language Map of Korea". In Brunn, Stanley D; Kehrein, Roland (eds.). Handbook of the Changing World Language Map. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73400-2_110-1. ISBN 978-3-319-73400-2. S2CID 188565336. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ 김보향 (Kim Bo-hyang) (August 2014). "Osaka Ikuno-ku jiyeok jaeil Jejuinui Jeju bangeon sayong siltaee gwanhan yeongu" 오사카 이쿠노쿠 지역 재일제주인의 제주방언 사용 실태에 관한 연구 [A Study on the Jeju Dialect Used by Jeju People Living in Ikuno-ku, Osaka, Japan]. 영주어문 학술저널 [Yeongju Language and Literature Academic Journal]. 28: 120. ISSN 1598-9011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2000), p. 313.

- ^ Kang Yoonjung; Han Sungwoo (September 2013). "Tonogenesis in early Contemporary Seoul Korean: A longitudinal case study". Lingua. 134: 62–74. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2013.06.002.

- ^ Kim Mi-Ryoung (2013). "Tonogenesis in contemporary Korean with special reference to the onset-tone interaction and the loss of a consonant opposition". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 133 (5 Supplement). 3570. Bibcode:2013ASAJ..133.3570K. doi:10.1121/1.4806535.

- ^ Cho Sunghye (2017). Development of pitch contrast and Seoul Korean intonation (PhD). University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020.

- ^ Choi Jiyoun; Kim Sahyang; Cho Taehong (22 October 2020). "An apparent-time study of an ongoing sound change in Seoul Korean: A prosodic account". PLOS ONE. 15 (10). e0240682. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1540682C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240682. PMC 7580931. PMID 33091043.

- ^ 정(Jeong), 상도(Sangdo) (31 March 2017). 도청도설 부추와 정구지. The Kookje Daily News (in Korean). Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Kanno, Hiroomi; Society for Korean Linguistics in Japan, eds. (1987). 『朝鮮語を学ぼう』 [Chōsengo o manabō] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Sanshūsha. ISBN 4-384-01506-2.

- ^ Sohn (2006), p. 38

- ^ 일본을 거쳐서 들어온 외래 어휘. National Institute of Korean Language. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ Choe, Sang-hun (30 August 2006). "Koreas: Divided by a common language". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Beliefs that bind". Korea JoongAng Daily. 23 October 2007. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Sohn (2001), p. 6.

- ^ 누리-세종학당. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ KSIF Archived 19 February 2024 at the Wayback Machine - KSIF

- ^ "TOPIK". iSeodang Korean Language Center. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Raugh, Harold E. "The Origins of the Transformation of the Defense Language Program" (PDF). Applied Language Learning. 16 (2): 1–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ^ "DLI's language guidelines". AUSA. 1 August 2010. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Languages". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ Lee, Saekyun H.; HyunJoo Han. "Issues of Validity of SAT Subject Test Korea with Listening" (PDF). Applied Language Learning. 17 (1): 33–56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008.

- ^ "Global popularity of Korean language surges". The Korea Herald. 22 July 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ Pickles, Matt (11 July 2018). "K-pop drives boom in Korean language lessons". BBC News. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "Korea Marks 558th Hangul Day". The Chosun Ilbo. 10 October 2004. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- ^ Yun Suh-young (20 January 2013). "Korean language test-takers pass 1 mil". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ 해외시험장. TOPIK 한국어능력시험 (in Korean). Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights – Korean (Hankuko)". OHCHR. Archived from the original on 27 July 2023.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Argüelles, Alexander; Kim, Jong-Rok (2000). A Historical, Literary and Cultural Approach to the Korean Language. Seoul, South Korea: Hollym.

- Argüelles, Alexander; Kim, Jongrok (2004). A Handbook of Korean Verbal Conjugation. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Argüelles, Alexander (2007). Korean Newspaper Reader. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Argüelles, Alexander (2010). North Korean Reader. Hyattsville, Maryland: Dunwoody Press.

- Brown, L. (2015). "Expressive, Social and Gendered Meanings of Korean Honorifics". Korean Linguistics. 17 (2): 242–266. doi:10.1075/kl.17.2.04bro.

- Chang, Suk-jin (1996). Korean. London Oriental and African Language Library. Vol. 4. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-55619-728-4.

- Cho, Young A. (2006). "Gender Differences in Korean Speech". In Sohn, Ho-min (ed.). Korean Language in Culture and Society. University of Hawaii Press. p. 189.

- Cho, Sungdai; Whitman, John (2020). Korean: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51485-9.

- Hulbert, Homer B. (1905). A Comparative Grammar of the Korean Language and the Dravidian Dialects in India. Seoul: Methodist Publishing House.

- Lee, Iksop; Ramsey, S. Robert (2000). The Korean Language. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4831-1.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011). A History of the Korean Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66189-8.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1966). "Lexical Evidence Relating Japanese to Korean". Language. 42 (2): 185–251. doi:10.2307/411687. JSTOR 411687.

- Martin, Samuel E. (1990). "Morphological clues to the relationship of Japanese and Korean". In Baldi, Philip (ed.). Linguistic Change and Reconstruction Methodology. Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs. Vol. 45. pp. 483–509.

- Martin, Samuel E. (2006). A Reference Grammar of Korean: A Complete Guide to the Grammar and History of the Korean Language – 韓國語文法總監. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3771-2.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1971). Japanese and the Other Altaic Languages. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-52719-0.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1996). Languages and History: Japanese, Korean and Altaic. Oslo, Norway: Institute for Comparative Research in Human Culture. ISBN 974-8299-69-4.

- Ramstedt, G. J. (1928). "Remarks on the Korean language". Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 58.

- Rybatzki, Volker (2003). "Middle Mongol". In Janhunen, Juha (ed.). The Mongolic languages. London, England: Routledge. pp. 47–82. ISBN 0-7007-1133-3.

- Starostin, Sergei A.; Dybo, Anna V.; Mudrak, Oleg A. (2003). Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages. Leiden, South Holland: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13153-1. In 3 volumes.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (2001) [1999]. The Korean Language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36943-5.

- Sohn, Ho-Min (2006). Korean Language in Culture and Society. Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8248-2694-9.

- Song, J.-J. (2005). The Korean Language: Structure, Use and Context. London, England: Routledge.

- Trask, R. L. (1996). Historical linguistics. Hodder Arnold.

- Vovin, Alexander (2008). "Man'yōshū to Fudoki ni Mirareru Fushigina Kotoba to Jōdai Nihon Retto ni Okeru Ainugo no Bunpu" [Strange Words in the Man'yoshū and the Fudoki and the Distribution of the Ainu Language in the Japanese Islands in Prehistory] (PDF) (paper). International Research Center for Japanese Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Vovin, Alexander (2010). Koreo-Japonica: A Re-evaluation of a Common Genetic Origin. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Whitman, John B. (1985). The Phonological Basis for the Comparison of Japanese and Korean (PhD thesis). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. Unpublished Harvard University PhD dissertation.

- Yeon, Jaehoon; Brown, Lucien (2011). Korean: A Comprehensive Grammar. London, England: Routledge.

External links

[edit]- Linguistic and Philosophical Origins of the Korean Alphabet (Hangul)

- Sogang University free online Korean language and culture course

- Beginner's guide to Korean for English speakers Archived 30 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- U.S. Foreign Service Institute Korean basic course

- asianreadings.com, Korean readings with hover prompts

- Linguistic map of Korea

- dongsa.net, Korean verb conjugation tool

- Hanja Explorer, a tool to visualize and study Korean vocabulary

Korean language

View on GrokipediaNames and Etymology

Historical and Native Names

In the Republic of Korea (South Korea), the Korean language is designated Hangugeo (한국어), a compound term literally meaning "language of Hanguk," where Hanguk serves as the informal native name for the country, derived from historical references to the ancient Samhan confederacies and solidified in usage after 1948.[8] This nomenclature underscores a national identity linked to the peninsula's indigenous heritage, distinct from imperial dynastic titles.[9] In the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) and among ethnic Koreans in China's Yanbian region, the language is termed Chosŏnŏ (조선어) in formal contexts or Chosŏnmal (조선말, "Joseon speech") colloquially, drawing from Chosŏn (Joseon), the name of the dynasty that ruled from 1392 to 1910 and the North Korean state's preferred ethnonym for the Korean ethnicity.[10][9] This naming convention was institutionalized post-1948 to evoke continuity with pre-colonial sovereignty, prioritizing Joseon's legacy over other historical periods.[8] Prior to the 20th-century division of Korea, no standardized native name for the language existed in records, as it functioned primarily as the oral vernacular (aban or common speech) in contrast to Literary Chinese (hanmun), which dominated written discourse until Hangul's wider adoption.[8] Joseon-era texts, such as those promoting Hangul after its 1446 promulgation, referred to the spoken form indirectly as the "sounds of the people" (hunmin), without a dedicated linguistic label, reflecting its status as an unformalized substrate to Sino-centric scholarship.[10] Earlier attestations from the Three Kingdoms period (57 BCE–668 CE) and Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) similarly embed the language in glosses or adaptations like idu script, but yield no distinct native appellation, indicating it was conceived as the inherent speech of Koreanic speakers rather than a named entity.[9]Exonyms and International Designations

The English exonym for the Korean language, "Korean," derives from the name "Korea," which originated as a European adaptation of Goryeo (고려), the name of the dynasty that ruled the Korean Peninsula from 918 to 1392 CE. This term entered Western usage via Portuguese "Corea" in the 16th century, reflecting medieval trade and cartographic records of the region.[11] [9] Under international standards, the language is designated "Korean" with the ISO 639-1 code "ko," a two-letter identifier maintained by the International Organization for Standardization and used in global contexts such as the United Nations, digital encoding (e.g., Unicode), and linguistic classification systems.[12] This unified exonym applies to the language's varieties spoken by over 80 million native speakers, bridging differences between South Korean hangugeo (한국어) and North Korean chosŏnŏ (조선어) for cross-border reference.[12] In neighboring East Asian languages, exonyms frequently incorporate political or historical references to Korea's division. In Mandarin Chinese, the South Korean variety is typically called 韩语 (Hányǔ), while 朝鲜语 (Cháoxiǎn yǔ) denotes the North Korean form or the language in broader historical usage.[13] In Japanese, 韓国語 (Kankokugo) refers to the southern variant, and 朝鮮語 (Chōsengo) to the northern or pre-division form, mirroring terms for the respective states.[14] These distinctions arose post-1945 partition and reflect geopolitical influences rather than linguistic divergence, as the varieties remain mutually intelligible.Linguistic Classification

Status as a Language Isolate

Korean is widely classified as a language isolate, defined as a language with no demonstrable genetic relationship to any other known language family, based on the absence of regular sound correspondences, shared basic vocabulary, and reconstructible proto-forms that meet the comparative method's standards.[15][16] This status stems from extensive comparative linguistic analysis failing to establish convincing cognates or grammatical innovations linking Korean to neighboring language groups, such as Sino-Tibetan, Austronesian, or Dravidian families, despite geographic proximity and historical contact.[16] Within the Korean Peninsula, the Jeju language (spoken on Jeju Island) exhibits mutual unintelligibility with standard Korean and distinct phonological and lexical features, leading some linguists to group them as a small Koreanic family, though this does not alter Korean's isolate status relative to external languages.[17] Proponents of broader affiliations, such as the Altaic hypothesis (encompassing Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Korean, and sometimes Japanese), cite typological similarities like agglutinative morphology and subject-object-verb word order, but these are critiqued as areal convergences rather than genetic evidence, lacking the systematic phonological shifts required for proof.[18][19] The isolate classification prevails in contemporary linguistics due to the failure of proposed affiliations to withstand scrutiny; for instance, early 20th-century Ural-Altaic theories, popular until the mid-1960s, have been largely abandoned for insufficient regular correspondences in core vocabulary.[18] Recent proposals, including a 2021 Bayesian phylogenetic study suggesting a shared ancestor with Japanese, Korean, and Turkic languages around 9,000 years ago originating in ancient northern China, remain fringe and unverified by independent replication or traditional comparative methods.[20] Thus, Korean stands as the world's largest language isolate by native speakers, with over 80 million, underscoring its unique developmental trajectory uninfluenced by proven genetic kin.[16]Hypotheses of Genetic Affiliation

Several hypotheses have proposed genetic affiliations for Korean beyond its classification as an isolate, though most lack robust comparative evidence and are contested by mainstream linguists who attribute observed similarities to prolonged language contact rather than common ancestry. The Altaic hypothesis, originating in the 19th century and popularized through works like Ramstedt's classifications in the early 20th century, posits Korean as part of a family including Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, and sometimes Japonic languages, citing shared agglutinative morphology, vowel harmony, and typological features like subject-object-verb order. However, critics argue these traits represent areal convergence from geographic proximity and historical interactions across Eurasia, not genetic inheritance, with proposed cognates often explainable as loanwords or onomatopoeia; systematic sound correspondences required for proving relatedness are absent or inconsistent.[21] [15] The Koreanic-Japonic hypothesis suggests a closer link between Korean and Japanese (including Ryukyuan varieties), potentially forming a small family diverging around 2,300–4,000 years ago based on grammatical parallels like honorific systems, particle usage, and limited vocabulary matches (e.g., body parts and numerals). Proponents, including some analyses of Proto-Koreanic reconstructions, point to shared innovations absent in broader Altaic proposals, but detractors like Alexander Vovin highlight insufficient basic vocabulary overlap and irregular sound changes, viewing similarities as substrate influences from ancient Korean migrations to Japan rather than shared descent.[22] [17] This view persists in some genetic studies correlating linguistic divergence with population movements, yet linguistic consensus remains skeptical due to the paucity of regular correspondences meeting the comparative method's standards.[23] Fringe proposals include affiliations with Austronesian languages, drawing on southern origin theories with claimed cognates in basic terms and phonological traits like vowel systems, as explored in mid-20th-century works by scholars like Kim Chin-u; evidence includes potential shared roots for numerals and maritime vocabulary, but these are criticized as coincidental or methodologically flawed, with no systematic lexicon supporting deep-time relatedness. Similarly, Dravido-Korean links, first hypothesized by Homer B. Hulbert in 1905, invoke typological parallels with Dravidian languages of India, such as agglutination and retroflex sounds, yet lack verifiable cognates and are dismissed as speculative without archaeological or genetic corroboration.[24] [25] Other suggestions, like ties to Munda or Uralic, have even less empirical backing and are not seriously entertained in contemporary linguistics. Overall, these hypotheses underscore the challenges in reconstructing deep affiliations for Korean, where empirical hurdles like limited early documentation and potential extinct relatives impede verification, reinforcing the isolate classification absent compelling counter-evidence.[26]Historical Development

Origins and Proto-Korean