Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

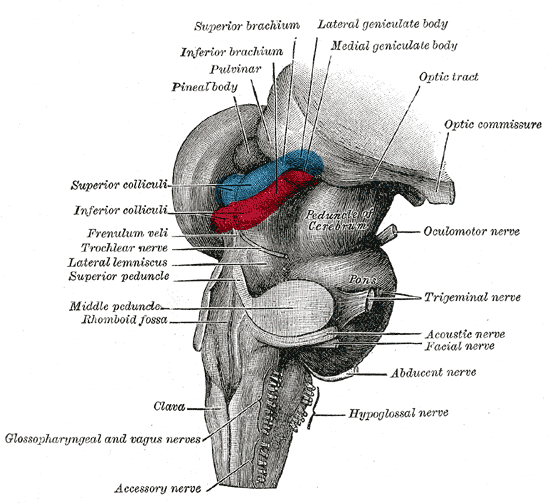

Lateral geniculate nucleus

View on Wikipedia| Lateral geniculate nucleus | |

|---|---|

Hind- and mid-brains; postero-lateral view. (Lateral geniculate body visible near top.) | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Thalamus |

| System | Visual |

| Artery | Anterior choroidal and Posterior cerebral |

| Vein | Terminal vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | corpus geniculatum laterale |

| Acronym | LGN |

| NeuroNames | 352 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1662 |

| TA98 | A14.1.08.302 |

| TA2 | 5666 |

| FMA | 62209 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral projection of the thalamus where the thalamus connects with the optic nerve. There are two LGNs, one on the left and another on the right side of the thalamus. In humans, both LGNs have six layers of neurons (grey matter) alternating with optic fibers (white matter).

The LGN receives information directly from the ascending retinal ganglion cells via the optic tract and from the reticular activating system. Neurons of the LGN send their axons through the optic radiation, a direct pathway to the primary visual cortex. In addition, the LGN receives many strong feedback connections from the primary visual cortex.[1] In humans as well as other mammals, the two strongest pathways linking the eye to the brain are those projecting to the dorsal part of the LGN in the thalamus, and to the superior colliculus.[2]

Structure

[edit]

Both the left and right hemispheres of the brain have a lateral geniculate nucleus, named after its resemblance to a bent knee (genu is Latin for "knee"). In humans as well as in many other primates, the LGN has layers of magnocellular cells and parvocellular cells that are interleaved with layers of koniocellular cells.

In humans the LGN is normally described as having six distinctive layers. The inner two layers, (1 and 2) are magnocellular layers, while the outer four layers, (3, 4, 5 and 6), are parvocellular layers. An additional set of neurons, known as the koniocellular layers, are found ventral to each of the magnocellular and parvocellular layers.[3]: 227ff [4] This layering is variable between primate species, and extra leafleting is variable within species.

The average volume of each LGN in an adult human is about 118mm. (This is the same volume as a 4.9mm-sided cube.) A study of 24 hemispheres from 15 normal individuals with average age 59 years at autopsy found variation from about 91 to 157mm.[5] The same study found that in each LGN, the magnocellular layers comprised about 28mm in total, and the parvocellular layers comprised about 90mm in total.

M, P, K cells

[edit]

| Type | Size* | RGC Source | Type of Information | Location | Response | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M: Magnocellular cells | Large | Parasol cells | perception of movement, depth, and small differences in brightness | Layers 1 and 2 | rapid and transient | ? |

| P: Parvocellular cells (or "parvicellular") | Small | Midget cells | perception of color (red-green)[6] and form (fine details) | Layers 3, 4, 5 and 6 | slow and sustained | ? |

| K: Koniocellular cells (or "interlaminar") | Very small cell bodies | Bistratified cells | color (yellow-blue)[6] | Between each of the M and P layers |

*Size describes the cell body and dendritic tree, though also can describe the receptive field

The magnocellular, parvocellular, and koniocellular layers of the LGN correspond with the similarly named types of retinal ganglion cells. Retinal P ganglion cells send axons to a parvocellular layer, M ganglion cells send axons to a magnocellular layer, and K ganglion cells send axons to a koniocellular layer.[7]: 269

Koniocellular cells are functionally and neurochemically distinct from M and P cells and provide a third channel to the visual cortex. They project their axons between the layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus where M and P cells project. Their role in visual perception is presently unclear; however, the koniocellular system has been linked with the integration of somatosensory system-proprioceptive information with visual perception[citation needed], and it may also be involved in color perception.[8]

The parvo- and magnocellular fibers were previously thought to dominate the Ungerleider–Mishkin ventral stream and dorsal stream, respectively. However, new evidence has accumulated showing that the two streams appear to feed on a more even mixture of different types of nerve fibers.[9]

The other major retino–cortical visual pathway is the tectopulvinar pathway, routing primarily through the superior colliculus and thalamic pulvinar nucleus onto posterior parietal cortex and visual area MT.

Non-primates

[edit]Other mammals such as cats generally only have L and M cones, hence no red-green differentiation. They also have three cell types denoted as X (magno), Y (parvo), and W (konio). The W type is beyond most doubt homologous to the primate K type. There are some subtle differences between the M and X types as well as the Y and P types to make the correspondence unclear.[6] There is additional evidence of a yellow-blue opponent process in the LGN of mice.[10]

Ipsilateral and contralateral layers

[edit]Both the LGN in the right hemisphere and the LGN in the left hemisphere receive input from each eye. However, each LGN only receives information from one half of the visual field. Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) from the inner halves of each retina (the nasal sides) decussate (cross to the other side of the brain) through the optic chiasma (khiasma means "cross-shaped"). RGCs from the outer half of each retina (the temporal sides) remain on the same side of the brain. Therefore, the right LGN receives visual information from the left visual field, and the left LGN receives visual information from the right visual field. Within one LGN, the visual information is divided among the various layers as follows:[11]

- the eye on the same side (the ipsilateral eye) sends information to layers 2, 3 and 5

- the eye on the opposite side (the contralateral eye) sends information to layers 1, 4 and 6.

This description applies to the LGN of many primates, but not all. The sequence of layers receiving information from the ipsilateral and contralateral (opposite side of the head) eyes is different in the tarsier.[12] Some neuroscientists suggested that "this apparent difference distinguishes tarsiers from all other primates, reinforcing the view that they arose in an early, independent line of primate evolution".[13]

Input

[edit]The LGN receives input from the retina and many other brain structures, especially visual cortex.

The principal neurons in the LGN receive strong inputs from the retina. However, the retina only accounts for a small percentage of LGN input. As much as 95% of input in the LGN comes from the visual cortex, superior colliculus, pretectum, thalamic reticular nuclei, and local LGN interneurons. Regions in the brainstem that are not involved in visual perception also project to the LGN, such as the mesencephalic reticular formation, dorsal raphe nucleus, periaqueuctal grey matter, and the locus coeruleus.[14] The LGN also receives some inputs from the optic tectum (known as the superior colliculus in mammals).[15] These non-retinal inputs can be excitatory, inhibitory, or modulatory.[14]

Output

[edit]Information leaving the LGN travels out on the optic radiations, which form part of the retrolenticular portion of the internal capsule.

The axons that leave the LGN go to V1 visual cortex. Both the magnocellular layers 1–2 and the parvocellular layers 3–6 send their axons to layer 4 in V1. Within layer 4 of V1, layer 4cβ receives parvocellular input, and layer 4cα receives magnocellular input. However, the koniocellular layers, intercalated between LGN layers 1–6 send their axons primarily to the cytochrome-oxidase rich blobs of layers 2 and 3 in V1.[16] Axons from layer 6 of visual cortex send information back to the LGN.

Studies involving blindsight have suggested that projections from the LGN travel not only to the primary visual cortex but also to higher cortical areas V2 and V3. Patients with blindsight are phenomenally blind in certain areas of the visual field corresponding to a contralateral lesion in the primary visual cortex; however, these patients are able to perform certain motor tasks accurately in their blind field, such as grasping. This suggests that neurons travel from the LGN to both the primary visual cortex and higher cortex regions.[17]

Function in visual perception

[edit]The output of the LGN serves several functions.

Temporal and spatial processing

[edit]Computations are achieved to determine the position of every major element in object space relative to the principal plane. Through subsequent motion of the eyes, a larger stereoscopic mapping of the visual field is achieved.[18]

It has been shown that while the retina accomplishes spatial decorrelation through center-surround inhibition, the LGN accomplishes temporal decorrelation.[19] This spatial–temporal decorrelation makes for much more efficient coding. However, there is almost certainly much more going on.

Like other areas of the thalamus, particularly other relay nuclei, the LGN likely helps the visual system focus its attention on the most important information. That is, if you hear a sound slightly to your left, the auditory system likely "tells" the visual system, through the LGN via its surrounding peri-reticular nucleus, to direct visual attention to that part of space.[20] The LGN is also a station that refines certain receptive fields.[21]

Axiomatically determined functional models of LGN cells have been determined by Lindeberg [22][23] in terms of Laplacian of Gaussian kernels over the spatial domain in combination with temporal derivatives of either non-causal or time-causal scale-space kernels over the temporal domain. It has been shown that this theory both leads to predictions about receptive fields with good qualitative agreement with the biological receptive field measurements performed by DeAngelis et al.[24][25] and guarantees good theoretical properties of the mathematical receptive field model, including covariance and invariance properties under natural image transformations.[26][27] Specifically according to this theory, non-lagged LGN cells correspond to first-order temporal derivatives, whereas lagged LGN cells correspond to second-order temporal derivatives.

Color processing

[edit]The LGN is also integral in the early steps of color processing, where opponent channels are created that compare signals between the different photoreceptor cell types: a type of inter-channel decorrelation. The output of P-cells comprises red-green opponent signals. The output of M-cells does not include much color opponency, rather a sum of the red-green signal that evokes luminance. The output of K-cells comprises mostly blue-yellow opponent signals.[6]

Rodents

[edit]In rodents, the lateral geniculate nucleus contains the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN), the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus (vLGN), and the region in between called the intergeniculate leaflet (IGL). These are distinct subcortical nuclei with differences in function.

dLGN

[edit]The dorsolateral geniculate nucleus is the main division of the lateral geniculate body. In the mouse, the area of the dLGN is about 0.48mm. The majority of input to the dLGN comes from the retina. It is laminated and shows retinotopic organization.[28]

vLGN

[edit]The ventrolateral geniculate nucleus has been found to be relatively large in several species such as lizards, rodents, cows, cats, and primates.[29] An initial cytoarchitectural scheme, which has been confirmed in several studies, suggests that the vLGN is divided into two parts. The external and internal divisions are separated by a group of fine fibers and a zone of thinly dispersed neurons. Additionally, several studies have suggested further subdivisions of the vLGN in other species.[30] For example, studies indicate that the cytoarchitecture of the vLGN in the cat differs from rodents. Although five subdivisions of the vLGN in the cat have been identified by some,[31] the scheme that divides the vLGN into three regions (medial, intermediate, and lateral) has been more widely accepted.

IGL

[edit]The intergeniculate leaflet is a relatively small area found dorsal to the vLGN. Earlier studies had referred to the IGL as the internal dorsal division of the vLGN. Several studies have described homologous regions in several species, including humans.[32]

The vLGN and IGL appear to be closely related based on similarities in neurochemicals, inputs and outputs, and physiological properties.

The vLGN and IGL have been reported to share many neurochemicals that are found concentrated in the cells, including neuropeptide Y, GABA, encephalin, and nitric oxide synthase. The neurochemicals serotonin, acetylcholine, histamine, dopamine, and noradrenaline have been found in the fibers of these nuclei.

Both the vLGN and IGL receive input from the retina, locus coreuleus, and raphe. Other connections that have been found to be reciprocal include the superior colliculus, pretectum, and hypothalamus, as well as other thalamic nuclei.

Physiological and behavioral studies have shown spectral-sensitive and motion-sensitive responses that vary with species. The vLGN and IGL seem to play an important role in mediating phases of the circadian rhythms that are not involved with light, as well as phase shifts that are light-dependent.[30]

Additional images

[edit]-

Thalamus

-

Dissection of brain-stem. Lateral view.

-

Scheme showing central connections of the optic nerves and optic tracts.

-

Thalamic nuclei

-

3D schematic representation of optic tracts

-

Brainstem. Posterior view.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cudeiro, Javier; Sillito, Adam M. (2006). "Looking back: corticothalamic feedback and early visual processing". Trends in Neurosciences. 29 (6): 298–306. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.328.4248. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.05.002. PMID 16712965. S2CID 6301290.

- ^ Goodale, M. & Milner, D. (2004)Sight unseen.Oxford University Press, Inc.: New York.

- ^ Brodal, Per (2010). The central nervous system: structure and function (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538115-3.

- ^ Carlson, Neil R. (2007). Physiology of behavior (9th ed.). Boston: Pearson/Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-46724-2.

- ^ Andrews, Timothy J.; Halpern, Scott D.; Purves, Dale (1997). "Correlated Size Variations in Human Visual Cortex, Lateral Geniculate Nucleus, and Optic Tract". Journal of Neuroscience. 17 (8): 2859–2868. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02859.1997. PMC 6573115.

- ^ a b c d Ghodrati, Masoud; Khaligh-Razavi, Seyed-Mahdi; Lehky, Sidney R. (September 2017). "Towards building a more complex view of the lateral geniculate nucleus: Recent advances in understanding its role". Progress in Neurobiology. 156: 214–255. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.06.002. hdl:1721.1/120922.

- ^ Purves, Dale; Augustine, George; Fitzpatrick, David; Hall, William; Lamantia, Anthony-Samuel; White, Leonard (2011). Neuroscience (5. ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- ^ White, BJ; Boehnke, SE; Marino, RA; Itti, L; Munoz, DP (Sep 30, 2009). "Color-related signals in the primate superior colliculus". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (39): 12159–66. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1986-09.2009. PMC 6666157. PMID 19793973.

- ^ Goodale & Milner, 1993, 1995.

- ^ Schwartz, Gregory W. (August 2021). "Color vision: More than meets the eye". Current Biology. 31 (15): R948 – R950. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.06.044.

- ^ Nicholls J., et al. From Neuron to Brain: Fourth Edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc. 2001.

- ^ Rosa, MG; Pettigrew, JD; Cooper, HM (1996). "Unusual pattern of retinogeniculate projections in the controversial primate Tarsius". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 48 (3): 121–9. doi:10.1159/000113191. PMID 8872317.

- ^ Collins, CE; Hendrickson, A; Kaas, JH (Nov 2005). "Overview of the visual system of Tarsius". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 287 (1): 1013–25. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20263. PMID 16200648.

- ^ a b Guillery, R; SM Sherman (Jan 17, 2002). "Thalamic relay functions and their role in corticocortical communication: generalizations from the visual system". Neuron. 33 (2): 163–75. doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00582-7. PMID 11804565.

- ^ In Chapter 7, section "The Parcellation Hypothesis" of "Principles of Brain Evolution", Georg F. Striedter (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, USA, 2005) states, "...we now know that the LGN receives at least some inputs from the optic tectum (or superior colliculus) in many amniotes". He cites "Wild, J.M. (1989). "Pretectal and tectal projections to the homolog of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in the pigeon—an anterograde and retrograde tracing study with cholera-toxin conjugated to horseradish-peroxidase". Brain Res. 479 (1): 130–137. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(89)91342-5. PMID 2924142. S2CID 29034684." and also "Kaas, J.H., and Huerta, M.F. 1988. The subcortical visual system of primates. In: Steklis H. D., Erwin J., editors. Comparative primate biology, vol 4: neurosciences. New York: Alan Liss, pp. 327–391.

- ^ Hendry, Stewart H. C.; Reid, R. Clay (2000). "The koniocellular pathway in primate vision". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 23: 127–153. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.127. PMID 10845061.

- ^ Schmid, Michael C.; Mrowka, Sylwia W.; Turchi, Janita; et al. (2010). "Blindsight depends on the lateral geniculate nucleus". Nature. 466 (7304): 373–377. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..373S. doi:10.1038/nature09179. PMC 2904843. PMID 20574422.

- ^ Lindstrom, S. & Wrobel, A. (1990) Intracellular recordings from binocularly activated cells in the cats dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus Acta Neurobiol Exp vol 50, pp 61–70

- ^ Dawei W. Dong and Joseph J. Atick, Network–Temporal Decorrelation: A Theory of Lagged and Nonlagged Responses in the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus, 1995, pp. 159–178.

- ^ McAlonan, K.; Cavanaugh, J.; Wurtz, R. H. (2006). "Attentional Modulation of Thalamic Reticular Neurons". Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (16): 4444–4450. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5602-05.2006. PMC 6674014. PMID 16624964.

- ^ Tailby, C.; Cheong, S. K.; Pietersen, A. N.; Solomon, S. G.; Martin, P. R. (2012). "Colour and pattern selectivity of receptive fields in superior colliculus of marmoset monkeys". The Journal of Physiology. 590 (16): 4061–4077. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230409. PMC 3476648. PMID 22687612.

- ^ Lindeberg, T. (2013). "A computational theory of visual receptive fields". Biological Cybernetics. 107 (6): 589–635. doi:10.1007/s00422-013-0569-z. PMC 3840297. PMID 24197240.

- ^ Lindeberg, T. (2021). "Normative theory of visual receptive fields". Heliyon. 7 (1) e05897. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05897. PMC 7820928. PMID 33521348.

- ^ DeAngelis, G. C.; Ohzawa, I.; Freeman, R. D. (1995). "Receptive field dynamics in the central visual pathways". Trends Neurosci. 18 (10): 451–457. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(95)94496-r. PMID 8545912. S2CID 12827601.

- ^ G. C. DeAngelis and A. Anzai "A modern view of the classical receptive field: linear and non-linear spatio-temporal processing by V1 neurons. In: Chalupa, L.M., Werner, J.S. (eds.) The Visual Neurosciences, vol. 1, pp. 704–719. MIT Press, Cambridge, 2004.

- ^ Lindeberg, T. (2013). "Invariance of visual operations at the level of receptive fields". PLOS ONE. 8 (7) e66990. arXiv:1210.0754. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...866990L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066990. PMC 3716821. PMID 23894283.

- ^ T. Lindeberg "Covariance properties under natural image transformations for the generalized Gaussian derivative model for visual receptive fields", Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience, 17:1189949, 2023.

- ^ Grubb, Matthew S.; Francesco M. Rossi; Jean-Pierre Changeux; Ian D. Thompson (Dec 18, 2003). "Abnormal functional organization in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of mice lacking the beta2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor". Neuron. 40 (6): 1161–1172. doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00789-x. PMID 14687550.

- ^ Cooper, H.M.; M. Herbin; E. Nevo (Oct 9, 2004). "Visual system of a naturally microphthalamic mammal: The blind mole rat, Spalax ehrenbergl". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 328 (3): 313–350. doi:10.1002/cne.903280302. PMID 8440785. S2CID 28607983.

- ^ a b Harrington, Mary (1997). "The ventral lateral geniculate nucleus and the intergeniculate leaflet: interrelated structures in the visual and circadian systems". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 21 (5): 705–727. doi:10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00019-x. PMID 9353800. S2CID 20139828.

- ^ Jordan, J.; H. Hollander (1972). "The structure of the ventral part of the lateral geniculate nucleus – a cyto- and myeloarchitectonic study in the cat". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 145 (3): 259–272. doi:10.1002/cne.901450302. PMID 5030906. S2CID 30586321.

- ^ Moore, Robert Y. (1989). "The geniculohypothalamic tract in monkey and man". Brain Research. 486 (1): 190–194. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(89)91294-8. PMID 2720429. S2CID 33543381.

External links

[edit]- Malpeli J. Malpeli Lab Home Page. Retrieved September 1, 2004.

- Stained brain slice images which include the "lateral%20geniculate%20nucleus" at the BrainMaps project

- Atlas image: eye_38 at the University of Michigan Health System – "The Visual Pathway from Below"

- Stained brain slice images which include the "lgn" at the BrainMaps project

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 307 640