Recent from talks

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Contribute something

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Linux kernel.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Linux kernel

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

| Linux Kernel | |

|---|---|

| |

Linux kernel 6.1.0 kernel booting, under Debian | |

| Original author | Linus Torvalds |

| Developers | Community contributors Linus Torvalds |

| Initial release | 0.02 (5 October 1991) |

| Stable release | |

| Preview release | 6.18-rc4[4] |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C (with GNU extensions;[5] C11 (gnu11)[6] since 5.18, C89 (gnu89) before),[7] Assembly language |

| Available in | English |

| License | GPL-2.0-only with Linux-syscall-note[8][9][10][a] |

| Website | kernel |

The Linux kernel is a free and open-source[14]: 4 Unix-like kernel that is used in many computer systems worldwide. The kernel was created by Linus Torvalds in 1991 and was soon adopted as the kernel for the GNU operating system (OS) which was created to be a free replacement for Unix. Since the late 1990s, it has been included in many operating system distributions, many of which are called Linux. One such Linux kernel operating system is Android which is used in many mobile and embedded devices.

Most of the kernel code is written in C as supported by the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) which has extensions beyond standard C.[14]: 18 [15] The code also contains assembly code for architecture-specific logic such as optimizing memory use and task execution.[14]: 379–380 The kernel has a modular design such that modules can be integrated as software components – including dynamically loaded. The kernel is monolithic in an architectural sense since the entire OS kernel runs in kernel space.

Linux is provided under the GNU General Public License version 2, although it contains files under other compatible licenses.[13]

History

[edit]

In 1991, Linus Torvalds was a computer science student enrolled at the University of Helsinki. During his time there, he began to develop an operating system as a side-project inspired by UNIX, for a personal computer.[16] He started with a task switcher in Intel 80386 assembly language and a terminal driver.[16] On 25 August 1991, Torvalds posted the following to comp.os.minix, a newsgroup on Usenet:[17]

I'm doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won't be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones. This has been brewing since April, and is starting to get ready. I'd like any feedback on things people like/dislike in minix, as my OS resembles it somewhat (same physical layout of the file-system (due to practical reasons) among other things).

I've currently ported bash(1.08) and gcc(1.40), and things seem to work. This implies that I'll get something practical within a few months [...]

Yes - it's free of any minix code, and it has a multi-threaded fs. It is NOT protable [sic] (uses 386 task switching etc), and it probably never will support anything other than AT-harddisks, as that's all I have :-(.

On 17 September 1991, Torvalds prepared version 0.01 of Linux and put on the "ftp.funet.fi" – FTP server of the Finnish University and Research Network (FUNET). It was not even executable since its code still needed Minix to compile and test it.[18]

On 5 October 1991, Torvalds announced the first "official" version of Linux, version 0.02.[19][18]

[As] I mentioned a month ago, I'm working on a free version of a Minix-lookalike for AT-386 computers. It has finally reached the stage where it's even usable (though may not be depending on what you want), and I am willing to put out the sources for wider distribution. It is just version 0.02...but I've successfully run bash, gcc, gnu-make, gnu-sed, compress, etc. under it.

Linux grew rapidly as many developers, including the MINIX community, contributed to the project.[citation needed] At the time, the GNU Project had completed many components for its free UNIX replacement, GNU, but its kernel, the GNU Hurd, was incomplete. The project adopted the Linux kernel for its OS.[20]

Torvalds labeled the kernel with major version 0 to indicate that it was not yet intended for general use.[21] Version 0.11, released in December 1991, was the first version to be self-hosted; compiled on a computer running the Linux kernel.

When Torvalds released version 0.12 in February 1992, he adopted the GNU General Public License version 2 (GPLv2) over his previous self-drafted license, which had not permitted commercial redistribution.[22] In contrast to Unix, all source files of Linux are freely available, including device drivers.[23]

The initial success of Linux was driven by programmers and testers across the world. With the support of the POSIX APIs, through the libC that, whether needed, acts as an entry point to the kernel address space, Linux could run software and applications that had been developed for Unix.[24]

On 19 January 1992, the first post to the new newsgroup alt.os.linux was submitted.[25] On 31 March 1992, the newsgroup was renamed comp.os.linux.[26]

The fact that Linux is a monolithic kernel rather than a microkernel was the topic of a debate between Andrew S. Tanenbaum, the creator of MINIX, and Torvalds.[27] The Tanenbaum–Torvalds debate started in 1992 on the Usenet group comp.os.minix as a general discussion about kernel architectures.[28][29]

Version 0.96 released in May 1992 was the first capable of running the X Window System.[30][31] In March 1994, Linux 1.0.0 was released with 176,250 lines of code.[32] As indicated by the version number, it was the first version considered suitable for a production environment.[21] In June 1996, after release 1.3, Torvalds decided that Linux had evolved enough to warrant a new major number, and so labeled the next release as version 2.0.0.[33][34] Significant features of 2.0 included symmetric multiprocessing (SMP), support for more processors types and support for selecting specific hardware targets and for enabling architecture-specific features and optimizations.[24] The make *config family of commands of kbuild enable and configure options for building ad hoc kernel executables (vmlinux) and loadable modules.[35][36]

Version 2.2, released on 20 January 1999,[37] improved locking granularity and SMP management, added m68k, PowerPC, Sparc64, Alpha, and other 64-bit platforms support.[38] Furthermore, it added new file systems including Microsoft's NTFS read-only capability.[38] In 1999, IBM published its patches to the Linux 2.2.13 code for the support of the S/390 architecture.[39]

Version 2.4.0, released on 4 January 2001,[40] contained support for ISA Plug and Play, USB, and PC Cards. Linux 2.4 added support for the Pentium 4 and Itanium (the latter introduced the ia64 ISA that was jointly developed by Intel and Hewlett-Packard to supersede the older PA-RISC), and for the newer 64-bit MIPS processor.[41] Development for 2.4.x changed a bit in that more features were made available throughout the series, including support for Bluetooth, Logical Volume Manager (LVM) version 1, RAID support, InterMezzo and ext3 file systems.

Version 2.6.0 was released on 17 December 2003.[42] The development for 2.6.x changed further towards including new features throughout the series. Among the changes that have been made in the 2.6 series are: integration of μClinux into the mainline kernel sources, PAE support, support for several new lines of CPUs, integration of Advanced Linux Sound Architecture (ALSA) into the mainline kernel sources, support for up to 232 users (up from 216), support for up to 229 process IDs (64-bit only, 32-bit architectures still limited to 215),[43] substantially increased the number of device types and the number of devices of each type, improved 64-bit support, support for file systems which support file sizes of up to 16 terabytes, in-kernel preemption, support for the Native POSIX Thread Library (NPTL), User-mode Linux integration into the mainline kernel sources, SELinux integration into the mainline kernel sources, InfiniBand support, and considerably more.

Starting with 2.6.x releases, the kernel supported a large number of file systems; some designed for Linux, like ext3, ext4, FUSE, Btrfs,[44] and others native to other operating systems like JFS, XFS, Minix, Xenix, Irix, Solaris, System V, Windows and MS-DOS.[45]

Though development had not used a version control system thus far, in 2002, Linux developers adopted BitKeeper, which was made freely available to them even though it was not free software. In 2005, because of efforts to reverse-engineer it, the company which owned the software revoked its support of the Linux community. In response, Torvalds and others wrote Git. The new system was written within weeks, and in two months the first official kernel made using it was released.[46]

In 2005 the stable team was formed as a response to the lack of a kernel tree where people could work on bug fixes, and it would keep updating stable versions.[47] In February 2008 the linux-next tree was created to serve as a place where patches aimed to be merged during the next development cycle gathered.[48][49] Several subsystem maintainers also adopted the suffix -next for trees containing code which they mean to submit for inclusion in the next release cycle. As of January 2014[update], the in-development version of Linux is held in an unstable branch named linux-next.[50]

The 20th anniversary of Linux was celebrated by Torvalds in July 2011 with the release of version 3.0.0.[33] As 2.6 had been the version number for 8 years, a new uname26 personality that reports 3.x as 2.6.40+x had to be added to the kernel so that old programs would work.[51]

Version 3.0 was released on 22 July 2011.[52] On 30 May 2011, Torvalds announced that the big change was "NOTHING. Absolutely nothing." and asked, "...let's make sure we really make the next release not just an all new shiny number, but a good kernel too."[53] After the expected 6–7 weeks of the development process, it would be released near the 20th anniversary of Linux.

On 11 December 2012, Torvalds decided to reduce kernel complexity by removing support for i386 processors—specifically by not having to emulate[54] the atomic CMPXCHG instruction introduced with the i486 to allow reliable mutexes—making the 3.7 kernel series the last one still supporting the original processor.[55][56] The same series unified support for the ARM processor.[57]

The numbering change from 2.6.39 to 3.0, and from 3.19 to 4.0, involved no meaningful technical differentiation; the major version number was increased simply to avoid large minor numbers.[52][58] Stable 3.x.y kernels were released until 3.19 in February 2015. Version 3.11, released on 2 September 2013,[59] added many new features such as new O_TMPFILE flag for to reduce temporary file vulnerabilities, experimental AMD Radeon dynamic power management, low-latency network polling, and zswap (compressed swap cache).[60]

In April 2015, Torvalds released kernel version 4.0.[33] By February 2015, Linux had received contributions from nearly 12,000 programmers from more than 1,200 companies, including some of the world's largest software and hardware vendors.[61] Version 4.1 of Linux, released in June 2015, contains over 19.5 million lines of code contributed by almost 14,000 programmers.[62]

Linus Torvalds announced that kernel version 4.22 would instead be numbered 5.0 in March 2019, stating that "'5.0' doesn't mean anything more than that the 4.x numbers started getting big enough that I ran out of fingers and toes."[63] It featured many major additions such as support for the AMD Radeon FreeSync and NVIDIA Xavier display, fixes for F2FS, EXT4 and XFS, restored support for swap files on the Btrfs file system and continued work on the Intel Icelake Gen11 graphics and on the NXP i.MX8 SoCs.[64][65] This release was noticeably larger than the rest, Torvalds mentioning that "The overall changes for all of the 5.0 release are much bigger."[63]

A total of 1,991 developers, of whom 334 were first-time collaborators, added more than 553,000 lines of code to version 5.8, breaking the record previously held by version 4.9.[66]

Popularity

[edit]According to the Stack Overflow's annual Developer Survey of 2019, more than 53% of all respondents have developed software for Linux and about 27% for Android,[67] although only about 25% develop with Linux-based operating systems.[68]

Most websites run on Linux-based operating systems,[69][70] and all of the world's 500 most powerful supercomputers run on Linux.[71]

Linux distributions bundle the kernel with system software (e.g., the GNU C Library, systemd, and other Unix utilities and daemons) and a wide selection of application software, but their usage share in desktops is low in comparison to other operating systems.

Android, which runs on a modified Linux kernel, accounts for the majority of mobile device operating systems,[72][73][74] and is increasingly being used in embedded devices, making it a significant driver of Linux adoption.[24]

Value

[edit]

The cost to redevelop version 2.6.0 of the Linux kernel in a traditional proprietary development setting has been estimated to be US$612 million (€467M, £394M) in 2004 prices using the COCOMO person-month estimation model.[75] In 2006, a study funded by the European Union put the redevelopment cost of kernel version 2.6.8 higher, at €882M ($1.14bn, £744M).[76]

This topic was revisited in October 2008 by Amanda McPherson, Brian Proffitt, and Ron Hale-Evans. Using David A. Wheeler's methodology, they estimated redevelopment of the 2.6.25 kernel now costs $1.3bn (part of a total $10.8bn to redevelop Fedora 9).[77] Again, Garcia-Garcia and Alonso de Magdaleno from University of Oviedo (Spain) estimate that the value annually added to kernel was about €100M between 2005 and 2007 and €225M in 2008, it would cost also more than €1bn (about $1.4bn as of February 2010) to develop in the European Union.[78]

As of 7 March 2011[update], using then-current LOC (lines of code) of a 2.6.x Linux kernel and wage numbers with David A. Wheeler's calculations it would cost approximately $3bn (about €2.2bn) to redevelop the Linux kernel as it keeps getting bigger. An updated calculation as of 26 September 2018[update], using then-current 20,088,609 LOC (lines of code) for the 4.14.14 Linux kernel and the current US national average programmer salary of $75,506 show that it would cost approximately $14,725,449,000 (£11,191,341,000) to rewrite the existing code.[79]

Distribution

[edit]Most who use Linux do so via a Linux distribution. Some distributions ship the vanilla or stable kernel. However, several vendors (such as Red Hat and Debian) maintain a customized source tree. These are usually updated at a slower pace than the vanilla branch, and they usually include all fixes from the relevant stable branch, but at the same time they can also add support for drivers or features which had not been released in the vanilla version the distribution vendor started basing its branch from.

Developers

[edit]Community

[edit]Graph of the sizes of Linux Kernel versions in millions of lines of code[80]. View source data.

The community of Linux kernel developers comprises about 5000–6000 members. According to the "2017 State of Linux Kernel Development", a study issued by the Linux Foundation, covering the commits for the releases 4.8 to 4.13, about 1500 developers were contributing from about 200–250 companies on average. The top 30 developers contributed a little more than 16% of the code. For companies, the top contributors are Intel (13.1%) and Red Hat (7.2%), Linaro (5.6%), IBM (4.1%), the second and fifth places are held by the 'none' (8.2%) and 'unknown' (4.1%) categories.[81]

"Instead of a roadmap, there are technical guidelines. Instead of a central resource allocation, there are persons and companies who all have a stake in the further development of the Linux kernel, quite independently from one another: People like Linus Torvalds and I don’t plan the kernel evolution. We don’t sit there and think up the roadmap for the next two years, then assign resources to the various new features. That's because we don’t have any resources. The resources are all owned by the various corporations who use and contribute to Linux, as well as by the various independent contributors out there. It's those people who own the resources who decide..."

— Andrew Morton, 2005

Conflict

[edit]Notable conflicts among Linux kernel developers:

- In July 2007, Con Kolivas announced that he would cease developing for the Linux kernel.[82][83]

- In July 2009, Alan Cox quit his role as the TTY layer maintainer after disagreement with Torvalds.[84]

- In December 2010, there was a discussion between Linux SCSI maintainer James Bottomley and SCST maintainer Vladislav Bolkhovitin about which SCSI target stack should be included in the Linux kernel.[85] This made some Linux users upset.[86]

- In June 2012, Torvalds made it very clear that he did not agree with NVIDIA releasing its drivers as closed.[87]

- In April 2014, Torvalds banned Kay Sievers from submitting patches to the Linux kernel for failing to deal with bugs that caused systemd to negatively interact with the kernel.[88]

- In October 2014, Lennart Poettering accused Torvalds of tolerating the rough discussion style on Linux kernel related mailing lists and of being a bad role model.[89]

- In March 2015, Christoph Hellwig filed a lawsuit against VMware for infringement of the copyright on the Linux kernel.[90] Linus Torvalds made it clear that he did not agree with this and similar initiatives by calling lawyers a festering disease.[91]

- In April 2021, a team from the University of Minnesota was found to be submitting "bad faith" patches to the kernel as part of its research. This resulted in the immediate reversion of all patches ever submitted by a member of the university. In addition, a warning was issued by a senior maintainer that any future patch from the university would be rejected on sight.[92][93]

Prominent Linux kernel developers have been aware of the importance of avoiding conflicts between developers.[94] For a long time there was no code of conduct for kernel developers due to opposition by Torvalds.[95] However, a Linux Kernel Code of Conflict was introduced on 8 March 2015.[96] It was replaced on 16 September 2018 by a new Code of Conduct based on the Contributor Covenant. This coincided with a public apology by Torvalds and a brief break from kernel development.[97][98] On 30 November 2018, complying with the Code of Conduct, Jarkko Sakkinen of Intel sent out patches replacing instances of "fuck" appearing in source code comments with suitable versions focused on the word 'hug'.[99]

Developers who feel treated unfairly can report this to the Linux Foundation Technical Advisory Board.[100] In July 2013, the maintainer of the USB 3.0 driver Sage Sharp asked Torvalds to address the abusive commentary in the kernel development community. In 2014, Sharp backed out of Linux kernel development, saying that "The focus on technical excellence, in combination with overloaded maintainers, and people with different cultural and social norms, means that Linux kernel maintainers are often blunt, rude, or brutal to get their job done".[101] At the linux.conf.au (LCA) conference in 2018, developers expressed the view that the culture of the community has gotten much better in the past few years. Daniel Vetter, the maintainer of the Intel drm/i915 graphics kernel driver, commented that the "rather violent language and discussion" in the kernel community has decreased or disappeared.[102]

Laurent Pinchart asked developers for feedback on their experiences with the kernel community at the 2017 Embedded Linux Conference Europe. The issues brought up were discussed a few days later at the Maintainers Summit. Concerns over the lack of consistency in how maintainers responded to patches submitted by developers were echoed by Shuah Khan, the maintainer of the kernel self-test framework. Torvalds contended that there would never be consistency in the handling of patches because different kernel subsystems have, over time, adopted different development processes. Therefore, it was agreed upon that each kernel subsystem maintainer would document the rules for patch acceptance.[103]

Development

[edit]Linux is evolution, not intelligent design!

Codebase

[edit]The kernel source code, a.k.a. source tree, is managed in the Git version control system – also created by Torvalds.[107]

As of 2021[update], the 5.11 release of the Linux kernel had around 30.34 million lines of code. Roughly 14% of the code is part of the "core," including architecture-specific code, kernel code, and memory management code, while 60% is drivers.

Contributions

[edit]Contributions are submitted as patches, in the form of text messages on the Linux kernel mailing list (LKML) (and often also on other mailing lists dedicated to particular subsystems). The patches must conform to a set of rules and to a formal language that, among other things, describes which lines of code are to be deleted and what others are to be added to the specified files. These patches can be automatically processed so that system administrators can apply them in order to make just some changes to the code or to incrementally upgrade to the next version.[108] Linux is distributed also in GNU zip (gzip) and bzip2 formats.

A developer who wants to change the Linux kernel writes and tests a code change. Depending on how significant the change is and how many subsystems it modifies, the change will either be submitted as a single patch or in multiple patches of source code. In case of a single subsystem that is maintained by a single maintainer, these patches are sent as e-mails to the maintainer of the subsystem with the appropriate mailing list in Cc. The maintainer and the readers of the mailing list will review the patches and provide feedback. Once the review process has finished the subsystem maintainer accepts the patches in the relevant Git kernel tree. If the changes to the Linux kernel are bug fixes that are considered important enough, a pull request for the patches will be sent to Torvalds within a few days. Otherwise, a pull request will be sent to Torvalds during the next merge window. The merge window usually lasts two weeks and starts immediately after the release of the previous kernel version.[109] The Git kernel source tree names all developers who have contributed to the Linux kernel in the Credits directory and all subsystem maintainers are listed in Maintainers.[110]

As with many large open-source software projects, developers are required to adhere to the Contributor Covenant, a code of conduct intended to address harassment of minority contributors.[111][112] Additionally, to prevent offense the use of inclusive terminology within the source code is mandated.[113]

Programming language

[edit]Linux is written in a special C programming language supported by GCC, a compiler that extends the C standard in many ways, for example using inline sections of code written in the assembly language (in GCC's "AT&T-style" syntax) of the target architecture.

In September 2021, the GCC version requirement for compiling and building the Linux kernel increased from GCC 4.9 to 5.1, allowing the potential for the kernel to be moved from using C code based on the C89 standard to using code written with the C11 standard,[114] with the migration to the standard taking place in March 2022, with the release of Linux 5.18.[115]

Initial support for the Rust programming language was added in Linux 6.1[116] which was released in December 2022,[117] with later kernel versions, such as Linux 6.2 and Linux 6.3, further improving the support.[118][119]

Coding style

[edit]Since 2002, code must adhere to the 21 rules of the Linux Kernel Coding Style.[120][121]

Versioning

[edit]As for most software, the kernel is versioned as a series of dot-separated numbers.

For early versions, the version consisted of three or four dot-separated numbers called major release, minor release and revision.[14]: 9 At that time, odd-numbered minor releases were for development and testing, while even numbered minor releases for production. The optional fourth digit indicated a patch level.[21] Development releases were indicated with a release candidate suffix (-rc).

The current versioning conventions are different. The odd/even number implying dev/prod has been dropped, and a major version is indicated by the first two numbers together. While the time-frame is open for the development of the next major, the -rcN suffix is used to identify the n'th release candidate for the next version.[122] For example, the release of the version 4.16 was preceded by seven 4.16-rcN (from -rc1 to -rc7). Once a stable version is released, its maintenance is passed to the stable team. Updates to a stable release are identified by a three-number scheme (e.g., 4.16.1, 4.16.2, ...).[122]

Toolchain

[edit]The kernel is usually built with the GNU toolchain. The GNU C compiler, GNU cc, part of the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), is the default compiler for mainline Linux. Sequencing is handled by GNU make. The GNU Assembler (often called GAS or GNU as) outputs the object files from the GCC generated assembly code. Finally, the GNU Linker (GNU ld) produces a statically linked executable kernel file called vmlinux. Both as and ld are part of GNU Binary Utilities (binutils).

GNU cc was for a long time the only compiler capable of correctly building Linux. In 2004, Intel claimed to have modified the kernel so that its C compiler was also capable of compiling it.[123] There was another such reported success in 2009, with a modified 2.6.22 version.[124][125] Support for the Intel compiler has been dropped in 2023.[126]

Since 2010, effort has been underway to build Linux with Clang, an alternative compiler for the C language;[127] as of 12 April 2014, the official kernel could almost be compiled by Clang.[128][129] The project dedicated to this effort is named LLVMLinux after the LLVM compiler infrastructure upon which Clang is built.[130] LLVMLinux does not aim to fork either Linux or the LLVM, therefore it is a meta-project composed of patches that are eventually submitted to the upstream projects. By enabling Linux to be compiled by Clang, developers may benefit from shorter compilation times.[131]

In 2017, developers completed upstreaming patches to support building the Linux kernel with Clang in the 4.15 release, having backported support for X86-64 and AArch64 to the 4.4, 4.9, and 4.14 branches of the stable kernel tree. Google's Pixel 2 shipped with the first Clang built Linux kernel,[132] though patches for Pixel (1st generation) did exist.[133] 2018 saw ChromeOS move to building kernels with Clang by default,[134] while Android made Clang[135] and LLVM's linker LLD[136] required for kernel builds in 2019. Google moved its production kernel used throughout its datacenters to being built with Clang in 2020.[137] The ClangBuiltLinux group coordinates fixes to both Linux and LLVM to ensure compatibility, both composed of members from LLVMLinux and having upstreamed patches from LLVMLinux.

Debugging

[edit]

As with any software, problems with the Linux kernel can be difficult to troubleshoot. Common challenges relate to userspace vs. kernel space access, misuse of synchronization primitives, and incorrect hardware management.[14]: 364

An oops is a non-fatal error in the kernel. After such an error, operations continue with suspect reliability.[138]

A panic (generated by panic()) is a fatal error. After such an error, the kernel prints a message and halts the computer.[14]: 371

The kernel provides for debugging by printing via printk() which stores messages in a circular buffer (overwriting older entries with newer). The syslog(2) system call provides for reading and clearing the message buffer and for setting the maximum log level of the messages to be sent to the console.[139] Kernel messages are also exported to userland through the /dev/kmsg interface.[140]

The ftrace mechanism allow for debugging by tracing. It is used for monitoring and debugging Linux at runtime and it can analyze user space latencies due to kernel misbehavior.[141][142][143][144] Furthermore, ftrace allows users to trace Linux at boot-time.[145]

kprobes and kretprobes can break into kernel execution (like debuggers in userspace) and collect information non-disruptively.[146] kprobes can be inserted into code at (almost) any address, while kretprobes work at function return. uprobes have similar purposes but they also have some differences in usage and implementation.[147]

With KGDB Linux can be debugged in much the same way as userspace programs. KGDB requires an additional machine that runs GDB and that is connected to the target to be debugged using a serial cable or Ethernet.[148]

Change process

[edit]The Linux kernel project integrates new code on a rolling basis. Standard operating procedure is that software checked into the project must work and compile without error.

Each kernel subsystem is assigned a maintainer who is responsible for reviewing patches against the kernel code standards and keeping a queue of patches that can be submitted to Torvalds within a merge window that is usually several weeks.

Patches are merged by Torvalds into the source code of the prior stable Linux kernel release, creating the release candidate (-rc) for the next stable release. Once the merge window is closed, only fixes to the new code in the development release are accepted. The -rc development release of the kernel goes through regression testing and once it is considered stable by Torvalds and the subsystem maintainers, a new version is released and the development process starts over again.[149]

Mainline Linux

[edit]

The Git tree that contains the Linux kernel source code is referred to as mainline Linux. Every stable kernel release originates from the mainline tree,[150] and is frequently published on kernel.org. Mainline Linux has only solid support for a small subset of the many devices that run Linux. Non-mainline support is provided by independent projects, such as Yocto or Linaro, but in many cases the kernel from the device vendor is needed.[151] Using a vendor kernel likely requires a board support package.

Maintaining a kernel tree outside of mainline Linux has proven to be difficult.[152]

Mainlining refers to the effort of adding support for a device to the mainline kernel,[153] while there was formerly only support in a fork or no support at all. This usually includes adding drivers or device tree files. When this is finished, the feature or security fix is considered mainlined.[154]

Linux-like kernel

[edit]The maintainer of the stable branch, Greg Kroah-Hartman, has applied the term Linux-like to downstream kernel forks by vendors that add millions of lines of code to the mainline kernel.[155] In 2019, Google stated that it wanted to use the mainline Linux kernel in Android so the number of kernel forks would be reduced.[156] The term Linux-like has also been applied to the Embeddable Linux Kernel Subset, which does not include the full mainline Linux kernel but a small modified subset of the code.[157]

Linux forks

[edit]

There are certain communities that develop kernels based on the official Linux. Some interesting bits of code from these forks that include Linux-libre, Compute Node Linux, INK, L4Linux, RTLinux, and User-Mode Linux (UML) have been merged into the mainline.[158] Some operating systems developed for mobile phones initially used heavily modified versions of Linux, including Google Android, Firefox OS, HP webOS, Nokia Maemo and Jolla Sailfish OS. In 2010, the Linux community criticised Google for effectively starting its own kernel tree:[159][160]

This means that any drivers written for Android hardware platforms, can not get merged into the main kernel tree because they have dependencies on code that only lives in Google's kernel tree, causing it to fail to build in the kernel.org tree. Because of this, Google has now prevented a large chunk of hardware drivers and platform code from ever getting merged into the main kernel tree. Effectively creating a kernel branch that a number of different vendors are now relying on.[161]

— Greg Kroah-Hartman, 2010

Today Android uses a customized Linux[162] where major changes are implemented in device drivers, but some changes to the core kernel code is required. Android developers also submit patches to the official Linux that finally can boot the Android operating system. For example, a Nexus 7 can boot and run the mainline Linux.[162]

At a 2001 presentation at the Computer History Museum, Torvalds had this to say in response to a question about distributions of Linux using precisely the same kernel sources or not:

They're not... well they are, and they're not. There is no single kernel. Every single distribution has their own changes. That's been going on since pretty much day one. I don't know if you may remember Yggdrasil was known for having quite extreme changes to the kernel and even today all of the major vendors have their own tweaks because they have some portion of the market they're interested in and quite frankly that's how it should be. Because if everybody expects one person, me, to be able to track everything that's not the point of GPL. That's not the point of having an open system. So actually the fact that a distribution decides that something is so important to them that they will add patches for even when it's not in the standard kernel, that's a really good sign for me. So that's for example how something like ReiserFS got added. And the reason why ReiserFS is the first journaling filesystem that was integrated in the standard kernel was not because I love Hans Reiser. It was because SUSE actually started shipping with ReiserFS as their standard kernel, which told me "ok." This is actually in production use. Normal People are doing this. They must know something I don't know. So in a very real sense what a lot of distribution houses do, they are part of this "let's make our own branch" and "let's make our changes to this." And because of the GPL, I can take the best portions of them.[163]

— Linus Torvalds, 2001

Long-term support

[edit]

The latest version and older versions are maintained separately. Most of the latest kernel releases were supervised by Torvalds.[164]

The Linux kernel developer community maintains a stable kernel by applying fixes for software bugs that have been discovered during the development of the subsequent stable kernel. Therefore, www.kernel.org always lists two stable kernels. The next stable Linux kernel is released about 8 to 12 weeks later.

Some releases are designated for long-term support as longterm with bug fix releases for two or more years.[165]

Size

[edit]Some projects have attempted to reduce the size of the Linux kernel. One of them is TinyLinux. In 2014, Josh Triplett started the -tiny source tree for a reduced size version.[166][167][168][169]

Architecture and features

[edit]

Even though seemingly contradictory, the Linux kernel is both monolithic and modular. The kernel is classified as a monolithic kernel architecturally since the entire OS runs in kernel space. The design is modular since it can be assembled from modules that in some cases are loaded and unloaded at runtime.[14]: 338 [170] It supports features once only available in closed source kernels of non-free operating systems.

The rest of the article makes use of the UNIX and Unix-like operating systems convention of the manual pages. The number that follows the name of a command, interface, or other feature specifies the section (i.e. the type of the OS' component or feature) it belongs to. For example execve(2) refers to a system call, and exec(3) refers to a userspace library wrapper.

The following is an overview of architectural design and of noteworthy features.

- Concurrent computing and (with the availability of enough CPU cores for tasks that are ready to run) even true parallel execution of many processes at once (each of them having one or more threads of execution) on SMP and NUMA architectures.

- Selection and configuration of hundreds of kernel features and drivers (using one of the make *config family of commands before building),[171][36][35] modification of kernel parameters before boot (usually by inserting instructions into the lines of the GRUB2 menu), and fine tuning of kernel behavior at run-time (using the sysctl(8) interface to /proc/sys/).[172][173][174]

- Configuration (again using the make *config commands) and run-time modifications of the policies[175] (via nice(2), setpriority(2), and the family of sched_*(2) syscalls) of the task schedulers that allow preemptive multitasking (both in user mode and, since the 2.6 series, in kernel mode[176][177]); the earliest eligible virtual deadline first scheduling (EEVDF) scheduler,[178] is the default scheduler of Linux since 2023 and it uses a red-black tree which can search, insert and delete process information (task struct) with O(log n) time complexity, where n is the number of runnable tasks.[179][180]

- Advanced memory management with paged virtual memory.

- Inter-process communications and synchronization mechanism.

- A virtual filesystem on top of several concrete filesystems (ext4, Btrfs, XFS, JFS, FAT32, and many more).

- Configurable I/O schedulers, ioctl(2)[181] syscall that manipulates the underlying device parameters of special files (it is a non standard system call, since arguments, returns, and semantics depends on the device driver in question), support for POSIX asynchronous I/O[182] (however, because they scale poorly with multithreaded applications, a family of Linux specific I/O system calls (io_*(2)[183]) had to be created for the management of asynchronous I/O contexts suitable for concurrent processing).

- OS-level virtualization (with Linux-VServer), paravirtualization and hardware-assisted virtualization (with KVM or Xen, and using QEMU for hardware emulation);[184][185][186][187][188][189] On the Xen hypervisor, the Linux kernel provides support to build Linux distributions (such as openSUSE Leap and many others) that work as Dom0, that are virtual machine host servers that provide the management environment for the user's virtual machines (DomU).[190]

- I/O Virtualization with VFIO and SR-IOV. Virtual Function I/O (VFIO) exposes direct device access to user space in a secure memory (IOMMU) protected environment. With VFIO, a VM Guest can directly access hardware devices on the VM Host Server. This technique improves performance, if compared both to Full virtualization and Paravirtualization. However, with VFIO, devices cannot be shared with multiple VM guests. Single Root I/O Virtualization (SR-IOV) combines the performance gains of VFIO and the ability to share a device with several VM Guests (but it requires special hardware that must be capable to appear to two or more VM guests as different devices).[191]

- Security mechanisms for discretionary and mandatory access control (SELinux, AppArmor, POSIX ACLs, and others).[192][193]

- Several types of layered communication protocols (including the Internet protocol suite).

- Asymmetric multiprocessing via the RPMsg subsystem.

Most device drivers and kernel extensions run in kernel space (ring 0 in many CPU architectures), with full access to the hardware. Some exceptions run in user space; notable examples are filesystems based on FUSE/CUSE, and parts of UIO.[194][195] Furthermore, the X Window System and Wayland, the windowing system and display server protocols that most people use with Linux, do not run within the kernel. Differently, the actual interfacing with GPUs of graphics cards is an in-kernel subsystem called Direct Rendering Manager (DRM).

Unlike standard monolithic kernels, device drivers are easily configured as modules, and loaded or unloaded while the system is running and can also be pre-empted under certain conditions in order to handle hardware interrupts correctly and to better support symmetric multiprocessing.[177] By choice, Linux has no stable device driver application binary interface.[196]

Linux typically makes use of memory protection and virtual memory and can also handle non-uniform memory access,[197] however the project has absorbed μClinux which also makes it possible to run Linux on microcontrollers without virtual memory.[198]

The hardware is represented in the file hierarchy. User applications interact with device drivers via entries in the /dev or /sys directories.[199] Process information is mapped into the /proc directory.[199]

Interfaces

[edit]

Linux started as a clone of UNIX, and aims toward POSIX and Single UNIX Specification compliance.[201] The kernel provides system calls and other interfaces that are Linux-specific. In order to be included in the official kernel, the code must comply with a set of licensing rules.[8][13]

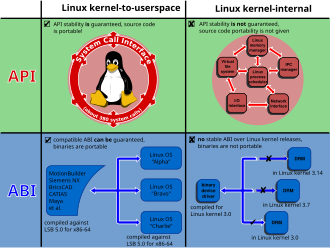

The Linux application binary interface (ABI) between the kernel and the user space has four degrees of stability (stable, testing, obsolete, removed);[202] The system calls are expected to never change in order to preserve compatibility for userspace programs that rely on them.[203]

Loadable kernel modules (LKMs), by design, cannot rely on a stable ABI.[196] Therefore, they must always be recompiled whenever a new kernel executable is installed in a system, otherwise they will not be loaded. In-tree drivers that are configured to become an integral part of the kernel executable (vmlinux) are statically linked by the build process.

There is no guarantee of stability of source-level in-kernel API[196] and, because of this, device driver code, as well as the code of any other kernel subsystem, must be kept updated with kernel evolution. Any developer who makes an API change is required to fix any code that breaks as the result of their change.[204]

Kernel-to-userspace API

[edit]The set of the Linux kernel API that regards the interfaces exposed to user applications is fundamentally composed of UNIX and Linux-specific system calls.[205] A system call is an entry point into the Linux kernel.[206] For example, among the Linux-specific ones there is the family of the clone(2) system calls.[207] Most extensions must be enabled by defining the _GNU_SOURCE macro in a header file or when the user-land code is being compiled.[208]

System calls can only be invoked via assembly instructions that enable the transition from unprivileged user space to privileged kernel space in ring 0. For this reason, the C standard library (libC) acts as a wrapper to most Linux system calls, by exposing C functions that, if needed,[209] transparently enter the kernel which will execute on behalf of the calling process.[205] For system calls not exposed by libC, such as the fast userspace mutex,[210] the library provides a function called syscall(2) which can be used to explicitly invoke them.[211]

Pseudo filesystems (e.g., the sysfs and procfs filesystems) and special files (e.g., /dev/random, /dev/sda, /dev/tty, and many others) constitute another layer of interface to kernel data structures representing hardware or logical (software) devices.[212][213]

Kernel-to-userspace ABI

[edit]Because of the differences existing between the hundreds of various implementations of the Linux OS, executable objects, even though they are compiled, assembled, and linked for running on a specific hardware architecture (that is, they use the ISA of the target hardware), often cannot run on different Linux distributions. This issue is mainly due to distribution-specific configurations and a set of patches applied to the code of the Linux kernel, differences in system libraries, services (daemons), filesystem hierarchies, and environment variables.

The main standard concerning application and binary compatibility of Linux distributions is the Linux Standard Base (LSB).[214][215] However, the LSB goes beyond what concerns the Linux kernel, because it also defines the desktop specifications, the X libraries and Qt that have little to do with it.[216] The LSB version 5 is built upon several standards and drafts (POSIX, SUS, X/Open, File System Hierarchy (FHS), and others).[217]

The parts of the LSB more relevant to the kernel are the General ABI (gABI),[218] especially the System V ABI[219][220] and the Executable and Linking Format (ELF),[221][222] and the Processor Specific ABI (psABI), for example the Core Specification for X86-64.[223][224]

The standard ABI for how x86_64 user programs invoke system calls is to load the syscall number into the rax register, and the other parameters into rdi, rsi, rdx, r10, r8, and r9, and finally to put the syscall assembly instruction in the code.[225][226][227]

In-kernel API

[edit]

There are several internal kernel APIs between kernel subsystems. Some are available only within the kernel subsystems, while a somewhat limited set of in-kernel symbols (i.e., variables, data structures, and functions) is exposed to dynamically loadable modules (e.g., device drivers loaded on demand) whether they're exported with the EXPORT_SYMBOL() and EXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL() macros[229][230] (the latter reserved to modules released under a GPL-compatible license).[231]

Linux provides in-kernel APIs that manipulate data structures (e.g., linked lists, radix trees,[232] red-black trees,[233] queues) or perform common routines (e.g., copy data from and to user space, allocate memory, print lines to the system log, and so on) that have remained stable at least since Linux version 2.6.[234][235][236]

In-kernel APIs include libraries of low-level common services used by device drivers:

- SCSI Interfaces and libATA – respectively, a peer-to-peer packet based communication protocol for storage devices attached to USB, SATA, SAS, Fibre Channel, FireWire, ATAPI device,[237] and an in-kernel library to support [S]ATA host controllers and devices.[238]

- Direct Rendering Manager (DRM) and Kernel Mode Setting (KMS) – for interfacing with GPUs and supporting the needs of modern 3D-accelerated video hardware,[239] and for setting screen resolution, color depth and refresh rate[240]

- DMA buffers (DMA-BUF) – for sharing buffers for hardware direct memory access across multiple device drivers and subsystems[241][242][243]

- Video4Linux – for video capture hardware

- Advanced Linux Sound Architecture (ALSA) – for sound cards

- New API – for network interface controllers

- mac80211 and cfg80211 – for wireless network interface controllers[244][245]

In-kernel ABI

[edit]The Linux developers chose not to maintain a stable in-kernel ABI. Modules compiled for a specific version of the kernel cannot be loaded into another version without being recompiled.[196]

Process management

[edit]Linux, as other kernels, has the ability to manage processes including creating, suspending, resuming and terminating. Unlike other operating systems, the Linux kernel implements processes as a group of threads called tasks. If two tasks share the same TGID, then they are called in the kernel terminology a task group. Each task is represented by a task_struct data structure. When a process is created it is assigned a globally unique identifier called PID and cannot be shared[246][247]

A new process can be created by calling clone[248] family of system calls or fork system call. Processes can be suspended and resumed by the kernel by sending signals like SIGSTOP and SIGCONT. A process can terminate itself by calling exit system call, or terminated by another process by sending signals like SIGKILL, SIGABRT or SIGINT.

If the executable is dynamically linked to shared libraries, a dynamic linker is used to find and load the needed objects, prepare the program to run and then run it.[249]

The Native POSIX Thread Library (NPTL)[250] provides the POSIX standard thread interface (pthreads) to userspace. The kernel isn't aware of processes nor threads but it is aware of tasks, thus threads are implemented in userspace. Threads in Linux are implemented as tasks sharing resources, while if they aren't sharing called to be independent processes.

The kernel provides the futex(7) (fast user-space mutex) mechanisms for user-space locking and synchronization.[251] The majority of the operations are performed in userspace but it may be necessary to communicate with the kernel using the futex(2) system call.[210]

As opposed to userspace threads described above, kernel threads run in kernel space.[252] They are threads created by the kernel itself for specialized tasks; they are privileged like the kernel and aren't bound to any process or application.

Scheduling

[edit]The Linux process scheduler is modular, in the sense that it enables different scheduling classes and policies.[253][254] Scheduler classes are plugable scheduler algorithms that can be registered with the base scheduler code. Each class schedules different types of processes. The core code of the scheduler iterates over each class in order of priority and chooses the highest priority scheduler that has a schedulable entity of type struct sched_entity ready to run.[14]: 46–47 Entities may be threads, group of threads, and even all the processes of a specific user.

Linux provides both user preemption as well as full kernel preemption.[14]: 62–63 Preemption reduces latency, increases responsiveness,[255] and makes Linux more suitable for desktop and real-time applications.

For normal tasks, by default, the kernel uses the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) class[needs update], introduced in version 2.6.23.[179] The scheduler is defined as a macro in a C header as SCHED_NORMAL. In other POSIX kernels, a similar policy known as SCHED_OTHER allocates CPU timeslices (i.e, it assigns absolute slices of the processor time depending on either predetermined or dynamically computed priority of each process). The Linux CFS does away with absolute timeslices and assigns a fair proportion of CPU time, as a function of parameters like the total number of runnable processes and the time they have already run; this function also takes into account a kind of weight that depends on their relative priorities (nice values).[14]: 46–50

With user preemption, the kernel scheduler can replace the current process with the execution of a context switch to a different one that therefore acquires the computing resources for running (CPU, memory, and more). It makes it according to the CFS algorithm (in particular, it uses a variable called vruntime for sorting entities and then chooses the one that has the smaller vruntime, - i.e., the schedulable entity that has had the least share of CPU time), to the active scheduler policy and to the relative priorities.[256] With kernel preemption, the kernel can preempt itself when an interrupt handler returns, when kernel tasks block, and whenever a subsystem explicitly calls the schedule() function.

The kernel also contains two POSIX-compliant[257] real-time scheduling classes named SCHED_FIFO (realtime first-in-first-out) and SCHED_RR (realtime round-robin), both of which take precedence over the default class.[253] An additional scheduling policy known as SCHED DEADLINE, implementing the earliest deadline first algorithm (EDF), was added in kernel version 3.14, released on 30 March 2014.[258][259] SCHED_DEADLINE takes precedence over all the other scheduling classes.

Real-time PREEMPT_RT patches, included into the mainline Linux since version 2.6, provide a deterministic scheduler, the removal of preemption and interrupt disabling (where possible), PI Mutexes (i.e., locking primitives that avoid priority inversion),[260][261] support for High Precision Event Timers (HPET), preemptive read-copy-update (RCU), (forced) IRQ threads, and other minor features.[262][263][264]

In 2023, Peter Zijlstra proposed replacing CFS with an earliest eligible virtual deadline first scheduling (EEVDF) scheduler,[265][266] to prevent the need for CFS "latency nice" patches.[267] The EEVDF scheduler replaced CFS in version 6.6 of the Linux kernel.[178]

Synchronization

[edit]The kernel has different causes of concurrency (e.g., interrupts, bottom halves, preemption of kernel and users tasks, symmetrical multiprocessing).[14]: 167

For protecting critical regions (sections of code that must be executed atomically), shared memory locations (like global variables and other data structures with global scope), and regions of memory that are asynchronously modifiable by hardware (e.g., having the C volatile type qualifier), Linux provides a large set of tools. They consist of atomic types (which can only be manipulated by a set of specific operators), spinlocks, semaphores, mutexes,[268][14]: 176–198 [269] and lockless algorithms (e.g., RCUs).[270][271][272] Most lock-less algorithms are built on top of memory barriers for the purpose of enforcing memory ordering and prevent undesired side effects due to compiler optimization.[273][274][275][276]

PREEMPT_RT code included in mainline Linux provide RT-mutexes, a special kind of Mutex which do not disable preemption and have support for priority inheritance.[277][278] Almost all locks are changed into sleeping locks when using configuration for realtime operation.[279][264][278] Priority inheritance avoids priority inversion by granting a low-priority task which holds a contended lock the priority of a higher-priority waiter until that lock is released.[280][281]

Linux includes a kernel lock validator called Lockdep.[282][283]

Interrupts

[edit]Although the management of interrupts could be seen as a single job, it is divided into two. This split in two is due to the different time constraints and to the synchronization needs of the tasks whose the management is composed of. The first part is made up of an asynchronous interrupt service routine (ISR) that in Linux is known as the top half, while the second part is carried out by one of three types of the so-called bottom halves (softirq, tasklets, and work queues).[14]: 133–137

Linux interrupt service routines can be nested. A new IRQ can trap into a high priority ISR that preempts any other lower priority ISR.

Memory

[edit]The Linux kernel manages both physical and virtual memory. It divides physical memory into zones,[284] each of which has a specific purpose.

- ZONE_DMA: this zone is suitable for DMA.

- ZONE_NORMAL: for normal memory operations.

- ZONE_HIGHMEM: part of physical memory that is only accessible to the kernel using temporary mapping.

Those zones are the most common, but others exist.[284]

Linux implements virtual memory with 4 or 5-level page tables.[285] The kernel is not pageable (meaning it is always resident in physical memory and cannot be swapped to the disk) and there is no memory protection (no SIGSEGV signals, unlike in user space), therefore memory violations lead to instability and system crashes.[14]: 20 User memory is pageable by default, although paging for specific memory areas can be disabled with the mlock() system call family.

Page frame information is maintained in apposite data structures (of type struct page) that are populated immediately after boot and kept until shutdown, regardless of whether they are associated with virtual pages. The physical address space is divided into different zones, according to architectural constraints and intended use. NUMA systems with multiple memory banks are also supported.[286]

Small chunks of memory can be dynamically allocated in kernel space via the family of kmalloc() APIs and freed with the appropriate variant of kfree(). vmalloc() and kvfree() are used for large virtually contiguous chunks. alloc_pages() allocates the desired number of entire pages.

The kernel used to include the SLAB, SLUB and SLOB allocators as configurable alternatives.[288][289] The SLOB allocator was removed in Linux 6.4[290] and the SLAB allocator was removed in Linux 6.8.[291] The sole remaining allocator is SLUB, which aims for simplicity and efficiency,[289] is PREEMPT_RT compatible[292] and was introduced in Linux 2.6.

Virtual filesystem

[edit]Since Linux supports numerous filesystems with different features and functionality, it is necessary to implement a generic filesystem that is independent from underlying filesystems. The virtual file system interfaces with other Linux subsystems, userspace, or APIs and abstracts away the different implementations of underlying filesystems. VFS implements system calls like create, open, read, write and close.

VFS implements a generic superblock[293] and inode block that is independent from the one that the underlying filesystem has.

In this subsystem directories and files are represented by a struct file data structure. When userspace requests access to a file it is returned a file descriptor (non negative integer value) but in kernel space it is a struct file structure. This structure stores all the information the kernel knows about a file or directory.

sysfs and procfs are virtual filesystems that expose hardware information and userspace programs' runtime information. These filesystems aren't present on disk and instead the kernel implements them as a callback or routine which gets called when they are accessed by userspace.

Supported architectures

[edit]

While not originally designed to be portable,[17][294] Linux is now one of the most widely ported operating system kernels, running on a diverse range of systems from the ARM architecture to IBM z/Architecture mainframe computers. The first port was performed on the Motorola 68000 platform. The modifications to the kernel were so fundamental that Torvalds viewed the Motorola version as a fork and a "Linux-like operating system".[294] However, that moved Torvalds to lead a major restructure of the code to facilitate porting to more computing architectures. The first Linux that, in a single source tree, had code for more than i386 alone, supported the DEC Alpha AXP 64-bit platform.[295][296][294]

Linux runs as the main operating system on IBM's Summit; as of October 2019[update], all of the world's 500 fastest supercomputers run some operating system based on the Linux kernel,[71] a big change from 1998 when the first Linux supercomputer got added to the list.[297]

Linux has also been ported to various handheld devices such as Apple's iPhone 3G and iPod.[298]

Supported devices

[edit]In 2007, the LKDDb project has been started to build a comprehensive database of hardware and protocols known by Linux kernels.[299] The database is built automatically by static analysis of the kernel sources. Later in 2014, the Linux Hardware project was launched to automatically collect a database of all tested hardware configurations with the help of users of various Linux distributions.[300]

Live patching

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (September 2023) |

Rebootless updates can even be applied to the kernel by using live patching technologies such as Ksplice, kpatch and kGraft. Minimalistic foundations for live kernel patching were merged into the Linux kernel mainline in kernel version 4.0, which was released on 12 April 2015. Those foundations, known as livepatch and based primarily on the kernel's ftrace functionality, form a common core capable of supporting hot patching by both kGraft and kpatch, by providing an application programming interface (API) for kernel modules that contain hot patches and an application binary interface (ABI) for the userspace management utilities. However, the common core included into Linux kernel 4.0 supports only the x86 architecture and does not provide any mechanisms for ensuring function-level consistency while the hot patches are applied.

Security

[edit]Kernel bugs present potential security issues. For example, they may allow for privilege escalation or create denial-of-service attack vectors. Over the years, numerous bugs affecting system security were found and fixed.[301] New features are frequently implemented to improve the kernel's security.[302][303]

Capabilities(7) have already been introduced in the section about the processes and threads. Android makes use of them and systemd gives administrators detailed control over the capabilities of processes.[304]

Linux offers a wealth of mechanisms to reduce kernel attack surface and improve security which are collectively known as the Linux Security Modules (LSM).[305] They comprise the Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) module, whose code has been originally developed and then released to the public by the NSA,[306] and AppArmor[193] among others. SELinux is now actively developed and maintained on GitHub.[192] SELinux and AppArmor provide support to access control security policies, including mandatory access control (MAC), though they profoundly differ in complexity and scope.

Another security feature is the Seccomp BPF (SECure COMPuting with Berkeley Packet Filters) which works by filtering parameters and reducing the set of system calls available to user-land applications.[307]

Critics have accused kernel developers of covering up security flaws, or at least not announcing them; in 2008, Torvalds responded to this with the following:[308][309]

I personally consider security bugs to be just "normal bugs". I don't cover them up, but I also don't have any reason what-so-ever to think it's a good idea to track them and announce them as something special...one reason I refuse to bother with the whole security circus is that I think it glorifies—and thus encourages—the wrong behavior. It makes "heroes" out of security people, as if the people who don't just fix normal bugs aren't as important. In fact, all the boring normal bugs are way more important, just because there's[sic] a lot more of them. I don't think some spectacular security hole should be glorified or cared about as being any more "special" than a random spectacular crash due to bad locking.

Linux distributions typically release security updates to fix vulnerabilities in the Linux kernel. Many offer long-term support releases that receive security updates for a certain Linux kernel version for an extended period of time.

In 2024, researchers disclosed that the Linux kernel contained a serious vulnerability, CVE-2024-50264, located in the AF_VSOCK subsystem. This bug is a use-after-free flaw, a class of memory corruption issue that occurs when a program continues to use memory after it has been freed.[310][311] Such flaws are particularly dangerous in the kernel, as they can allow attackers to escalate privileges. The bug was resolved in May 2025.[312]

Legal

[edit]Licensing terms

[edit]Initially, Torvalds released Linux under a license which forbade any commercial use.[313] This was changed in version 0.12 by a switch to the GNU General Public License version 2 (GPLv2).[22] This license allows distribution and sale of possibly modified and unmodified versions of Linux but requires that all those copies be released under the same license and be accompanied by - or that, on request, free access is given to - the complete corresponding source code.[314] Torvalds has described licensing Linux under the GPLv2 as the "best thing I ever did".[313]

The Linux kernel is licensed explicitly under GNU General Public License version 2 only (GPL-2.0-only) with an explicit syscall exception (Linux-syscall-note),[8][11][12] without offering the licensee the option to choose any later version, which is a common GPL extension. Contributed code must be available under GPL-compatible license.[13][204]

There was considerable debate about how easily the license could be changed to use later GPL versions (including version 3), and whether this change is even desirable.[315] Torvalds himself specifically indicated upon the release of version 2.4.0 that his own code is released only under version 2.[316] However, the terms of the GPL state that if no version is specified, then any version may be used,[317] and Alan Cox pointed out that very few other Linux contributors had specified a particular version of the GPL.[318]

In September 2006, a survey of 29 key kernel programmers indicated that 28 preferred GPLv2 to the then-current GPLv3 draft. Torvalds commented, "I think a number of outsiders... believed that I personally was just the odd man out because I've been so publicly not a huge fan of the GPLv3."[319] This group of high-profile kernel developers, including Torvalds, Greg Kroah-Hartman and Andrew Morton, commented on mass media about their objections to the GPLv3.[320] They referred to clauses regarding DRM/tivoization, patents, "additional restrictions" and warned a Balkanisation of the "Open Source Universe" by the GPLv3.[320][321] Torvalds, who decided not to adopt the GPLv3 for the Linux kernel, reiterated his criticism even years later.[322]

Loadable kernel modules

[edit]It is debated whether some loadable kernel modules (LKMs) are to be considered derivative works under copyright law, and thereby whether or not they fall under the terms of the GPL.

In accordance with the license rules, LKMs using only a public subset of the kernel interfaces[229][230] are non-derived works, thus Linux gives system administrators the mechanisms to load out-of-tree binary objects into the kernel address space.[13]

There are some out-of-tree loadable modules that make legitimate use of the dma_buf kernel feature.[323] GPL compliant code can certainly use it. However, a different possible use case would be Nvidia Optimus that pairs a fast GPU with an Intel integrated GPU, where the Nvidia GPU writes into the Intel framebuffer when it is active. But, Nvidia cannot use this infrastructure because it necessitates bypassing a rule that can only be used by LKMs that are also GPL.[231] Alan Cox replied on LKML, rejecting a request from one of Nvidia's engineers to remove this technical enforcement from the API.[324] Torvalds clearly stated on the LKML that "[I] claim that binary-only kernel modules ARE derivative "by default"'".[325]

On the other hand, Torvalds has also said that "[one] gray area in particular is something like a driver that was originally written for another operating system (i.e., clearly not a derived work of Linux in origin). THAT is a gray area, and _that_ is the area where I personally believe that some modules may be considered to not be derived works simply because they weren't designed for Linux and don't depend on any special Linux behaviour".[326] Proprietary graphics drivers, in particular, are heavily discussed.

Whenever proprietary modules are loaded into Linux, the kernel marks itself as being "tainted",[327] and therefore bug reports from tainted kernels will often be ignored by developers.

Firmware binary blobs

[edit]The official kernel, that is, Torvalds's git branch at the kernel.org repository, contains binary blobs released under the terms of the GNU GPLv2 license.[8][13] Linux can also load binary blobs, proprietary firmware, drivers, or other executable modules from the filesystem, and link them into kernel space.[328]

When necessary (e.g., for accessing boot devices or for speed), firmware can be built-in to the kernel, meaning building the firmware into vmlinux; however, this is not always a viable option for technical or legal issues (e.g., it is not permitted to do this with firmware that is not GPL compatible, although this is quite common nonetheless).[329]

Trademark

[edit]Linux is a registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States, the European Union, and some other countries.[330][331] A legal battle over the trademark began in 1996, when William Della Croce, a lawyer who was never involved in the development of Linux, started requesting licensing fees for the use of the word Linux. After it was proven that the word was in common use long before Della Croce's claimed first use, the trademark was awarded to Torvalds.[332][333][334]

Removal of Russian maintainers

[edit]In October 2024, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, kernel developer Greg Kroah-Hartman removed some kernel developers whose email addresses suggested a connection to Russia from their roles as maintainers.[335][336] Linus Torvalds responded that he did not support Russian aggression and would not revert the patch, insinuating that opponents of the patch were Russian trolls.[337] James Bottomley, a kernel developer, issued an apology for the handling of the situation and clarified that the action was a consequence of U.S. sanctions against Russia.[338]

See also

[edit]- Linux – Family of Unix-like operating systems

- Linux kernel version history – Version history of the Linux kernel

- Comparison of operating systems

- Comparison of operating system kernels

- Microkernel – Kernel that provides fewer services than a traditional kernel

- Minix 3 – Unix-like operating system

- macOS – Operating system for Apple computers

- Microsoft Windows – Computer operating systems

Notes

[edit]- ^ As a whole, Linux source is provided under the terms of the GPL-2.0-only license with an explicit syscall exception.[11][12] Aside from that, individual files can be provided under a different license which is required to be compatible with the GPL-2.0-only license (i.e., the GNU General Public License version 2) or a dual license, with one of the choices being the GPL version 2 or a GPLv2 compatible license.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ "Linux Logos and Mascots". Linux Online. 2008. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Greg Kroah-Hartman (2 November 2025). "Linux 6.17.7". Retrieved 2 November 2025.

- ^ Greg Kroah-Hartman (2 November 2025). "Linux 6.12.57". Retrieved 2 November 2025.

- ^ Linus Torvalds (2 November 2025). "Linux 6.18-rc4". Retrieved 2 November 2025.

- ^ Russell, Paul Rusty. "GNU Extensions". Unreliable Guide To Hacking The Linux Kernel. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ MaskRay (12 May 2024). "Exploring GNU extensions in the Linux kernel". MaskRay. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

- ^ Bergmann, Arnd (3 March 2022). "Kbuild: move to -std=gnu11". Linux kernel mailing list (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2025.

- ^ a b c d "COPYING". git.kernel.org. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "GNU General Public License v2.0 only". spdx.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Linux Syscall Note". spdx.org. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b "GPL-2.0". git.kernel.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Linux-syscall-note". git.kernel.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Linux kernel licensing rules". The Linux Kernel documentation. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Love, Robert (2010). Linux kernel development (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-672-32946-3. LCCN 2010018961. OCLC 268788260. OL 25534863M.

- ^ "Extensions to the C Language Family". gcc.gnu.org. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ a b Richardson, Marjorie (1 November 1999). "Interview: Linus Torvalds". Linux Journal. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ a b Torvalds, Linus Benedict (26 August 1991). "What would you like to see most in minix?". Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Usenet: 1991Aug25.205708.9541@klaava.Helsinki.FI. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ a b Welsh, Matt; Dalheimer, Matthias Kalle; Kaufman, Lar (1999). "1: Introduction to Linux". Running Linux (3rd ed.). Sebastopol, California: O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 1-56592-976-4. OCLC 50638246.

- ^ "Free minix-like kernel sources for 386-AT - Google Groups". groups.google.com. 5 October 1991. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Williams, Sam (March 2002). "Chapter 9: The GNU General Public License". Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman's Crusade for Free Software. O'Reilly. ISBN 0-596-00287-4. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Christine Bresnahan & Richard Blum (2016). LPIC-2: Linux Professional Institute Certification Study Guide: Exam 201 and Exam 202. John Wiley & Sons. p. 107. ISBN 9781119150794.

- ^ a b Torvalds, Linus. "Release Notes for Linux v0.12". The Linux Kernel Archives. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- ^ Fred Hantelmann (2016). LINUX Start-up Guide: A self-contained introduction. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 9783642607493.

- ^ a b c Fred Hantelmann (2016). LINUX Start-up Guide: A self-contained introduction. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 16. ISBN 9783642607493.

- ^ Summers, David W. (19 January 1992). "Troubles with Partitions". Newsgroup: alt.os.linux. Usenet: 1992Jan19.085628.18752@cseg01.uark.edu. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ Clegg, Alan B. (31 March 1992). "It's here!". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux. Usenet: 1992Mar31.131811.19832@rock.concert.net. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ "Appendix A: The Tanenbaum-Torvalds Debate". Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution. O'Reilly. 1999. ISBN 1-56592-582-3. Retrieved 22 November 2006.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andy (29 January 1992). "LINUX is obsolete". Newsgroup: comp.os.minix. Usenet: 12595@star.cs.vu.nl. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andy (12 May 2006). "Tanenbaum-Torvalds Debate: Part II". VU University Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ^ "0.96 out next week". www.krsaborio.net.

- ^ "refs/tags/v0.96a - pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/nico/archive - Git at Google". kernel.googlesource.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2025. Retrieved 3 May 2025.

- ^ Hayward, David (22 November 2012). "The history of Linux: how time has shaped the penguin". TechRadar. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Christine Bresnahan & Richard Blum (2016). LPIC-2: Linux Professional Institute Certification Study Guide: Exam 201 and Exam 202. John Wiley & Sons. p. 108. ISBN 9781119150794.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (9 June 1996). "Linux 2.0 really _is_ released." LKML (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Kernel Build System — The Linux Kernel documentation". Kernel.org. Archived from the original on 22 July 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Kconfig make config — The Linux Kernel documentation". Kernel.org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (20 January 1999). "2.2.0-final". LKML (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ a b "The Wonderful World of Linux 2.2". 26 January 1999. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "Linux/390 Observations and Notes". linuxvm.org. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (4 January 2001). "And oh, btw." LKML (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "The Wonderful World of Linux 2.4". Archived from the original on 17 March 2005. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (17 December 2003). "Linux 2.6.0". LKML (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "proc(5) - Linux manual page" (see /proc/sys/kernel/pid_max). Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "btrfs Wiki". btrfs.wiki.kernel.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Fred Hantelmann (2016). LINUX Start-up Guide: A self-contained introduction. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9783642607493.

- ^ Linux Kernel Mailing List (17 June 2005). "Linux 2.6.12". git-commits-head (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ Kroah-Hartman, Greg (3 August 2006). "Adrian Bunk is now taking over the 2.6.16-stable branch". LKML (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Rothwell, Stephen (12 February 2008). "Announce: Linux-next (Or Andrew's dream :-))". LKML (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ Corbet, Jonathan (21 October 2010). "linux-next and patch management process". LWN.net. Eklektix, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ "The Linux Kernel Archives". Kernel.org. Archived from the original on 30 January 1998. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ "Add a personality to report 2.6.x version numbers [LWN.net]". lwn.net. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ a b Torvalds, Linus (21 July 2011). "Linux 3.0 release". Linux kernel mailing list. Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (30 May 2011). "Linux 3.0-rc1". LKML (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 31 May 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (10 April 2001). "Re: [PATCH] i386 rw_semaphores fix". yarchive.net. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (13 December 2012). "Good-Bye 386: Linux to drop support for i386 chips with next major release". ZDNet. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2013.