Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Louis IX of France

View on Wikipedia

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis VIII, he was crowned in Reims at the age of 12. His mother, Blanche of Castile, effectively ruled the kingdom as regent until he came of age, and continued to serve as his trusted adviser until her death. During his formative years, Blanche successfully confronted rebellious vassals and championed the Capetian cause in the Albigensian Crusade, which had been ongoing for the past two decades.

Key Information

As an adult, Louis IX grappled with persistent conflicts involving some of the most influential nobles in his kingdom, including Hugh X of Lusignan and Peter I of Brittany. Concurrently, England's Henry III sought to reclaim the Angevin continental holdings, only to be decisively defeated at the Battle of Taillebourg. Louis expanded his territory by annexing several provinces, including parts of Aquitaine, Maine, and Provence. Keeping a promise he made while praying for recovery from a grave illness, Louis led the ill-fated Seventh and Eighth Crusades against the Muslim dynasties that controlled North Africa, Egypt, and the Holy Land. He was captured and ransomed during the Seventh Crusade, and later succumbed to dysentery during the Eighth Crusade. His son, Philip III, succeeded him.

Louis instigated significant reforms in the French legal system, creating a royal justice mechanism that allowed petitioners to appeal judgments directly to the monarch. He abolished trials by ordeal, endeavored to terminate private wars, and incorporated the presumption of innocence into criminal proceedings. To implement his new legal framework, he established the offices of provosts and bailiffs. Louis IX's reign is often marked as an economic and political zenith for medieval France, and he held immense respect throughout Christendom. His reputation as a fair and judicious ruler led to his being solicited to mediate disputes beyond his own kingdom.[1][2] Louis IX expanded upon the work of his predecessors, especially his grandfather Philip II of France and reformed the administrative institutions of the French crown.[3] He re-introduced, and expanded the scope of, the enquêtes commissioned to investigate governmental abuses and provide monetary restitutions for the crown.

Louis's admirers through the centuries have celebrated him as the quintessential Christian monarch. His skill as a knight and engaging manner with the public contributed to his popularity. Saint Louis was extremely pious, earning the moniker of a "monk king".[2][4] Louis was a staunch Christian and rigorously enforced Catholic orthodoxy. He enacted harsh laws against blasphemy,[5] and he also launched actions against France's Jewish population, including ordering them to wear a yellow badge of shame, as well as the notorious burning of the Talmud following the Disputation of Paris. Louis IX holds the distinction of being the sole canonized king of France and is also the direct ancestor of all subsequent French kings.[6]

Sources

[edit]Much of what is known of Louis's life comes from Jean de Joinville's famous Life of Saint Louis. Joinville was a close friend, confidant, and counselor to the king. He participated as a witness in the papal inquest into Louis's life that resulted in his canonization in 1297 by Pope Boniface VIII. Two other important biographies were written by the king's confessor, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, and his chaplain, William of Chartres. While several individuals wrote biographies in the decades following the king's death, only Jean of Joinville, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, and William of Chartres wrote from personal knowledge of the king and of the events they describe, and all three are biased favorably to the king. The fourth important source of information is William of Saint-Parthus's 19th-century biography,[7] which he wrote using material from the papal inquest mentioned above.

Early life

[edit]Louis was born on 25 April 1214 at Poissy, near Paris, the son of then-Prince Louis "the Lion" (later Louis VIII of France) and Blanche of Castile,[8], during the reign of his paternal grandfather, Philip II "Augustus" of France, and was baptized in Poissy in La Collégiale Notre-Dame church. His maternal grandfather was King Alfonso VIII of Castile. Tutors of Blanche's choosing taught him Latin, public speaking, writing, military arts, and government.[9] His father succeeded to the throne upon Philip II's death in 1223, when then-Prince Louis was nine years old.[10]

Minority (1226–1234)

[edit]Louis was 12 years old when his father died on 8 November 1226. His coronation as king took place on 29 November 1226 at Reims Cathedral, officiated by the bishop of Soissons.[11] Louis's mother, Queen Blanche, ruled France as regent during his minority.[12] Louis's mother instilled in him her devout Christianity. She is once recorded to have said:[13]

I love you, my dear son, as much as a mother can love her child; but I would rather see you dead at my feet than that you should ever commit a mortal sin.

Louis's younger brother Charles I of Sicily (1227–85) was created count of Anjou, thus founding the Capetian Angevin dynasty.

In 1229, when Louis was 15, his mother ended the Albigensian Crusade by signing an agreement with Raymond VII of Toulouse. Raymond VI of Toulouse had been suspected of ordering the assassination of Pierre de Castelnau, a Catholic preacher who attempted to convert the Cathars.[14]

On 27 May 1234, Louis married Margaret of Provence (1221–1295); she was crowned queen in Sens Cathedral the next day.[15] Margaret was the sister of Eleanor of Provence, who later married Henry III of England. The new Queen Margaret's religious zeal made her a well-suited partner for the king, and they are attested to have got on well, enjoying riding together, reading, and listening to music. His closeness to Margaret aroused jealousy in his mother, who tried to keep the couple apart as much as she could.[16]

While his contemporaries viewed Louis's reign as co-rule between him and his mother, historians generally believe Louis began ruling personally in 1234, with his mother then assuming a more advisory role.[1] She continued to have a strong influence on the king until her death in 1252.[12][17]

Louis as king

[edit]Arts

[edit]

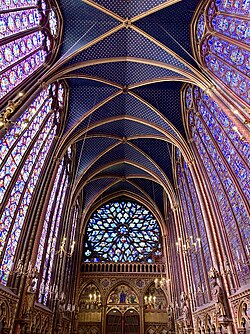

Louis's patronage of the arts inspired much innovation in Gothic art and architecture. The style of his court was influential throughout Europe, both because of artwork purchased from Parisian masters for export, and by the marriage of the king's daughters and other female relatives to foreigners. They became emissaries of Parisian models and styles elsewhere. Louis's personal chapel, the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, which was known for its intricate stained-glass windows, was copied more than once by his descendants elsewhere. Louis is believed to have ordered the production of the Morgan Bible and the Arsenal Bible, both deluxe illuminated manuscripts.

During the so-called "golden century of Saint Louis", the kingdom of France was at its height in Europe, both politically and economically. Saint Louis was regarded as "primus inter pares", first among equals, among the kings and rulers of the continent. He commanded the largest army and ruled the largest and wealthiest kingdom, the European centre of arts and intellectual thought at the time. The foundations for the notable college of theology, later known as the Sorbonne, were laid in Paris about the year 1257.[18]

Arbitration

[edit]

("Louis, by the grace of God, king of the Franks")

The prestige and respect felt by Europeans for King Louis IX were due more to the appeal of his personality than to military domination. For his contemporaries, he was the quintessential example of the Christian prince and embodied the whole of Christendom in his person. His reputation for fairness and even saintliness was already well established while he was alive, and on many occasions he was chosen as an arbiter in quarrels among the rulers of Europe.[1]

Shortly before 1256, Enguerrand IV, Lord of Coucy, arrested and without trial hanged three young squires of Laon, whom he accused of poaching in his forest. In 1256 Louis had the lord arrested and brought to the Louvre by his sergeants. Enguerrand demanded judgment by his peers and trial by battle, which the king refused because he thought it obsolete. Enguerrand was tried, sentenced, and ordered to pay 12,000 livres. Part of the money was to pay for masses to be said in perpetuity for the souls of the men he had hanged.

In 1258, Louis and James I of Aragon signed the Treaty of Corbeil to end areas of contention between them. By this treaty, Louis renounced his feudal overlordship over the County of Barcelona and Roussillon, which was held by the King of Aragon. James in turn renounced his feudal overlordship over several counties in southern France, including Provence and Languedoc. In 1259 Louis signed the Treaty of Paris, by which Henry III of England was confirmed in his possession of territories in southwestern France, and Louis received the provinces of Anjou, Normandy (Normandie), Poitou, Maine, and Touraine.[12]

Religion

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Integralism |

|---|

|

The perception of Louis IX by his contemporaries as the exemplary Christian prince was reinforced by his religious zeal. Louis was an extremely devout Catholic, and he built the Sainte-Chapelle ("Holy Chapel"),[1] located within the royal palace complex (now the Paris Hall of Justice), on the Île de la Cité in the centre of Paris. The Sainte Chapelle, a prime example of the Rayonnant style of Gothic architecture, was erected as a shrine for the crown of thorns and a fragment of the True Cross, precious relics of the Passion of Christ. He acquired these in 1239–41 from Emperor Baldwin II of the Latin Empire of Constantinople by agreeing to pay off Baldwin's debt to the Venetian merchant Niccolo Quirino, for which Baldwin had pledged the Crown of Thorns as collateral.[19] Louis IX paid the exorbitant sum of 135,000 livres to clear the debt.

In 1230, the king forbade all forms of usury, defined at the time as any taking of interest and therefore covering most banking activities. Louis used these anti-usury laws to extract funds from Jewish and Lombard moneylenders, with the hopes that it would help pay for a future crusade.[18] Louis also oversaw the Disputation of Paris in 1240, in which Paris's Jewish leaders were imprisoned and forced to admit to anti-Christian passages in the Talmud, the major source of Jewish commentaries on the Bible and religious law. As a result of the disputation, Pope Gregory IX declared that all copies of the Talmud should be seized and destroyed. In 1242, Louis ordered the burning of 12,000 copies of the Talmud, along with other important Jewish books and scripture.[20] The edict against the Talmud was eventually overturned by Gregory IX's successor, Innocent IV.[6]

Louis also expanded the scope of the Inquisition in France. He set the punishment for blasphemy to mutilation of the tongue and lips.[5] The area most affected by this expansion was southern France, where the Cathar sect had been strongest. The rate of confiscation of property from the Cathars and others reached its highest levels in the years before his first crusade and slowed upon his return to France in 1254.

In 1250, Louis headed a crusade to Egypt and was taken prisoner. During his captivity, he recited the Divine Office every day. After his release against ransom, he visited the Holy Land before returning to France.[13] In these deeds, Louis IX tried to fulfill what he considered the duty of France as "the eldest daughter of the Church" (la fille aînée de l'Église), a tradition of protector of the Church going back to the Franks and Charlemagne, who had been crowned by Pope Leo III in Rome in 800. The kings of France were known in the Church by the title "most Christian king" (Rex Christianissimus).

Louis founded many hospitals and houses: the House of the Filles-Dieu for reformed prostitutes; the Quinze-Vingt for 300 blind men (1254), and hospitals at Pontoise, Vernon, and Compiègne.[21]

St. Louis installed a house of the Trinitarian Order at Fontainebleau, his chateau and estate near Paris. He chose Trinitarians as his chaplains and was accompanied by them on his crusades. In his spiritual testament he wrote, "My dearest son, you should permit yourself to be tormented by every kind of martyrdom before you would allow yourself to commit a mortal sin."[13]

Louis authored and sent the Enseignements, or teachings, to his son Philip III. The letter outlined how Philip should follow the example of Jesus Christ in order to be a moral leader.[22] The letter is estimated to have been written in 1267, three years before Louis's death.[23]

Legal reforms

[edit]

Louis IX's most enduring domestic achievements came through his comprehensive reform of the French legal system. He created mechanisms that allowed subjects to appeal judicial decisions directly to the monarch, establishing a precedent for royal courts as the ultimate arbiters of justice in the kingdom. One of his most significant legal innovations was the abolition of trials by ordeal and combat, practices that had determined guilt or innocence through physical tests rather than evidence. Louis was the second European monarch after Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor to outlaw trial by ordeal, and in its place, Louis introduced the groundbreaking concept of presumption of innocence in criminal proceedings, fundamentally altering how justice was administered throughout the kingdom. These reforms collectively established a more rational and equitable legal framework that would influence French jurisprudence for centuries.

Prior to his departure on crusade in 1248, Louis had sent enquêteurs across the kingdom to receive complaints about royal injustice, investigate those claims, and provide restitutions to deserving petitioners. Based on the evidence of administrative corruption and malfeasance compiled in the enquêteurs' reports, as well as the disastrous failure of the crusade itself, in the last sixteen years of his reign Louis initiated a sweeping series of reforms.[3] This reform program was highlighted by the promulgation in December 1254 of what is known as the Great Reform Ordinance, a wide-ranging set of ethical principles and practical rules concerning the conduct and moral integrity of royal officers including baillis and enquêteurs. To ensure that the ordinance's precepts were upheld and enforced, the crown simultaneously relied upon a broad array of preventive strategies, intensive supervision, and accountability procedures, chief among them the reintroduction of the "enquêtes".[24] A 1261 inquest into the conduct of Mathieu de Beaune, bailli of Vermandois, illustrates Louis's commitment to accountability: testimonies from 247 witnesses were collected to investigate corruption allegations, showcasing the crown's rigorous oversight mechanisms and its mission to create a more transparent judiciary.[3] Such measures reduced localized abuses of power and standardized legal proceedings across the realm.

Perhaps most emblematic of Louis's commitment to justice was his personal involvement in judicial proceedings. According to many local legends and contemporary accounts, the king frequently sat under a great oak tree in the forest of Vincennes near Paris, where he would personally hear cases and render judgements.[25]

Scholarship and learning

[edit]

The reign of Louis IX coincided with a remarkable intellectual flourishing in France, particularly in Paris, which emerged as Europe's pre-eminent center of learning during Louis's reign. Scholars like William of Auvergne played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual landscape of Europe during his reign. William of Auvergne's monumental Magisterium divinale (1223–1240) attempted to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy with Christian doctrine, particularly challenges posed by Arabic commentaries on Aristotle. He was greatly favored by the crown and also served as a member of the regency council that ruled France in absence of the king during the seventh crusade.[26]

Perhaps greatest of all the intellectual minds active in France during Louis's reign was the theologian Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas's association with Paris represents one of the most fruitful collaborations between scholasticism and intellectual endeavor. Though Italian by birth, Aquinas conducted his most important work at the University of Paris, where he held the Dominican chair in theology twice (1256–1259 and 1269–1272). His Summa Theologica, widely considered to be the epitome of medieval scholastic theology, synthesized Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology in an unprecedented systematic framework at a time when Aristotle was just regaining popularity in Europe.[27]

Another major scholastic figure, the German Dominican Albertus Magnus, was also active at the University of Paris from 1245 to 1248. His experimental approach to natural sciences, exemplified by botanical studies and mineralogical investigations, prefigured later scientific methods while maintaining a theological framework.[28] Louis IX's support for Dominican institutions facilitated Albertus's work, which helped transform Paris into the primary center for Aristotelian studies.

Personal reign (1235–1266)

[edit]Construction of the Sainte-Chapelle

[edit]

The construction of Sainte-Chapelle was inspired by earlier Carolingian royal chapels, most notably the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne at Aix-la-Chapelle (modern-day Aachen). Before embarking on this ambitious project, Louis had already built a royal chapel at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1238. This earlier, single-level chapel's plan would be adapted for Sainte-Chapelle, though on a much grander scale.[29]

The primary motivation for building Sainte-Chapelle was to create a suitable sanctuary for Louis IX's collection of precious Christian relics including the crown of thorns. The foundation of the Chapelle was laid in 1241 and construction proceeded rapidly into the decade. On April 26, 1248 the Saint-Chapelle was consecrated as a private royal chapel for King Louis IX.[29]

The completed structure was remarkable in size, measuring 36 meters (118 ft) long, 17 meters (56 ft) wide, and 42.5 meters (139 ft) high - dimensions that rivaled contemporary Gothic cathedrals. The chapel featured two distinct levels of equal size but different purposes, the upper level housed the sacred relics and was reserved exclusively for the royal family and their guests, while the lower level served courtiers, servants, and palace

Seventh Crusade

[edit]

The Seventh Crusade was formally inaugurated by Pope Innocent IV’s issuance of the bull Terra Sancta Christi in 1245, which called for a renewed effort to secure Jerusalem by targeting Egypt, the economic and military linchpin of the Ayyubid Sultanate.[30] This papal directive built upon a century of crusading precedent, particularly the Fifth Crusade (1217–1221), which had similarly sought to leverage control over the Nile Delta to pressure Muslim powers in Syria and Palestine. Louis and his followers landed in Egypt on 4 or 5 June 1249 and began their campaign with the capture of the port of Damietta.[31][32] This attack caused some disruption in the Muslim Ayyubid empire, especially as the current sultan, Al-Malik as-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub, was on his deathbed. However, the march of Europeans from Damietta toward Cairo through the Nile River Delta went slowly. The seasonal rising of the Nile and the summer heat made it impossible for them to advance.[18] During this time, the Ayyubid sultan died, and the sultan's wife Shajar al-Durr set in motion a shift in power that would make her Queen and eventually result in the rule of the Egyptian army of the Mamluks.

On 8 February 1250, Louis lost his army at the Battle of Fariskur and was captured by the Egyptians. His release was eventually negotiated in return for a ransom of 400,000 bezants or about 200,000 livres tournois, a little less than the French crown's annual income,[33] and the surrender of the city of Damietta.[34]

Four years in the Kingdom of Jerusalem

[edit]Upon his liberation from captivity in Egypt, Louis IX devoted four years to fortifying the Kingdom of Jerusalem, focusing his efforts in Acre, Caesarea, and Jaffa. He used his resources to aid the Crusaders in reconstructing their defenses[35] and actively engaged in diplomatic endeavors with the Ayyubid dynasty. In the spring of 1254, Louis and his remaining forces made their return to France.[31]

Louis maintained regular correspondence and envoy exchanges with the Mongol rulers of his era. During his first crusade in 1248, he received envoys from Eljigidei, the Mongol military leader stationed in Armenia and Persia.[36] Eljigidei proposed that Louis should launch an offensive in Egypt while he targeted Baghdad to prevent the unification of the Muslim forces in Egypt and Syria. In response, Louis sent André de Longjumeau, a Dominican priest, as a delegate to the Khagan Güyük Khan (r. 1246–1248) in Mongolia. However, Güyük's death preceded the arrival of the emissary, and his widow and acting regent, Oghul Qaimish, rejected the diplomatic proposition.[37]

Louis sent another representative, the Franciscan missionary and explorer William of Rubruck, to the Mongol court. Rubruck visited the Khagan Möngke (r. 1251–1259) in Mongolia and spent several years there. In 1259, Berke, the leader of the Golden Horde, demanded Louis's submission.[38] In contrast, Mongol emperors Möngke and Khubilai's brother, the Ilkhan Hulegu, sent a letter to the French king, soliciting his military aid; this letter, however, never reached France.[39]

Return to France

[edit]

Louis IX returned to France in 1254 after spending four years in the Holy Land following his release from captivity during the failed Seventh Crusade. He set out from Acre on April 24, 1254, and arrived back in France in July of that year. The kingdom had been ruled by a regency in his absence, headed by the king's mother Blanche of Castile until her death in November 1252.

Jean de Joinville's narrative of the king's return home from crusade in July 1254 is marked by two fateful meetings. Upon disembarking at Hyères, forty miles east along the coast from Marseille, Louis and his entourage were met almost immediately by the abbot of Cluny, who presented him and the queen with two palfreys that Joinville estimated to be worth, by the standards of the first decade of the 1300s, five hundred livre tournois. The next day, the abbot returned to tell the king of his troubles, to which the king patiently and attentively listened. After the abbot's departure, Joinville posed to Louis whether the gift of the palfreys had made the king more favorable to the abbot's petition, and, when Louis replied in the affirmative, advised him that those men entrusted with administering the king's justice should be forbidden from accepting gifts, lest they "listen more willingly and with greater attention to those who gave them."[40]

While still at Hyères, the king heard of a renowned Franciscan named Hugues de Digne active in the area and, ever the enthusiast for sermons, requested that the friar attend the court so that Louis might hear him preach.[41]

Diplomatic relations and treaties

[edit]

After returning to France in 1254, Louis IX prioritized diplomatic settlements to resolve many longstanding territorial disputes and stabilize his kingdom's borders. In 1258, he concluded the Treaty of Corbeil with James I of Aragon. According to the terms of this treaty, Louis IX renounced ancient French claims of feudal overlordship over Catalonia (the Hispanic March), while James had to renounce all claims to several territories in southern France, including Languedoc, Provence, Toulouse, Quercy, and others, except for Montpellier and Carlat. Isabella, daughter of James I, was also betrothed to Philip, son of Louis IX securing peace with Aragon.

In 1259, Louis concluded the Treaty of Paris with Henry III of England. Henry III formally renounced all claims to Normandy, Anjou, Maine, Touraine, and Poitou-territories lost by his predecessors. In return, Louis IX recognized Henry III as Duke of Aquitaine and his vassal for Guyenne and Gascony, with Henry retaining control over these regions but under French suzerainty.[42] The Treaty of Paris had already positioned Louis as a respected mediator in European affairs, and in January 1264, Henry III formally requested Louis IX to arbitrate the dispute between the crown and the barons. Louis convened the Mise of Amiens, a judgement that annulled the Provisions of Oxford and sided decisively with Henry, rejecting the baronial reforms.[43] This ruling emboldened Henry's position but also deepened the conflict, as the barons, led by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, refused to accept the decision, which led to renewed warfare after 1264.

Louis IX's diplomatic reach extended across Western Europe and even into the Near East and Central Asia, earning him a reputation as one of the foremost arbitrators of his age. The king maintained diplomatic relations with the Mongols even after returning to France and in 1260, as the Mongols under Hulagu Khan sacked Baghdad and advanced into Syria, Louis maintained correspondence with Ilkhanate leaders, hoping to coordinate attacks against their mutual Mamluk adversaries.[25]

King Louis IX also maintained diplomatic relations with Emperor Frederick II and frequently corresponded with him, but their relationship was far from cordial. The contemporary Arab historian Ibn Wasil mentions a letter that the emperor sent to Louis, after the latter's release from captivity, in order "to remind him of his (own) sound advice and the consequences of his obstinacy and recalcitrance, and to upbraid him for it". There is no other record of this letter, but Frederick did write to King Ferdinand III of Castile blaming the pope for a disaster that could have been avoided; in this letter, the emperor links "papal cunning" to "the fate of our beloved friend, the illustrious King of France".[44] Frederick II also allegedly sent secret letters and envoys to Sultan As-Salih Ayyub of Egypt, warning him of Louis IX's impending crusade and offering to delay or disrupt the French king's campaign.[45]

King Louis IX enjoyed unparalleled prestige throughout Christendom and was respected even by his opponents as he was considered to be the 'Most Christian King' (rex Christianissimus). This title adopted by the French kings was later confirmed by the pope, while further papal concessions cemented France as the "eldest daughter of the church".[46] The king's influence was rooted not in military dominance but in widespread respect for his fairness, personal integrity, and reputation as a Christian ruler. European monarchs and nobles frequently sought his judgment in disputes, viewing him as an impartial and principled mediator.

Later reign (1267–1270)

[edit]Eighth Crusade and death

[edit]

In a parliament held at Paris, 24 March 1267, Louis and his three sons "took the cross". On hearing the reports of the missionaries, Louis resolved to land at Tunis, and he ordered his younger brother, Charles of Anjou, to join him there. The crusaders, among whom was the English prince Edward Longshanks, landed at Carthage 17 July 1270, but disease broke out in the camp.[35]

Louis died at Tunis on 25 August 1270, during an epidemic of dysentery that swept through his army.[47][48][49] According to European custom, his body was subjected to the process known as mos Teutonicus prior to most of his remains being returned to France.[50] Louis was succeeded as King of France by his son, Philip III.

Louis's younger brother, Charles I of Naples, preserved his heart and intestines, and conveyed them for burial in the Cathedral of Monreale near Palermo.[51]

Louis's bones were carried overland in a lengthy processional across Sicily, Italy, the Alps, and France, until they were interred in the royal necropolis at Saint-Denis in May 1271.[52] Charles and Philip III later dispersed a number of relics to promote Louis's veneration.[53]

Children

[edit]- Blanche (12 July/4 December 1240 – 29 April 1244), died in infancy.[8]

- Isabella (2 March 1241 – 28 January 1271), married Theobald II of Navarre.[54]

- Louis (23 September 1243/24 February 1244 – 11 January/2 February 1260). Betrothed to Berengaria of Castile in Paris on 20 August 1255.[55]

- Philip III (1 May 1245 – 5 October 1285), married firstly to Isabella of Aragon in 1262 and secondly to Maria of Brabant in 1274.

- John (1246/1247 – 10 March 1248), died in infancy.[8]

- John Tristan (8 April 1250 – 3 August 1270), Count of Valois, married Yolande II, Countess of Nevers.[8]

- Peter (1251 – 6/7 April 1284),[8] Count of Perche and Alençon, married Joanne of Châtillon.

- Blanche (early 1253 – 17 June 1320), married Ferdinand de la Cerda, Infante of Castile.[8]

- Margaret (early 1255 – July 1271), married John I, Duke of Brabant.[8]

- Robert (1256 – 7 February 1317), Count of Clermont,[8] married Beatrice of Burgundy. The French crown devolved upon his male-line descendant, Henry IV (the first Bourbon king), when the legitimate male line of Philip III died out in 1589.

- Agnes (1260 – 19/20 December 1327), married Robert II, Duke of Burgundy.[8]

Louis and Margaret's two children who died in infancy were first buried at the Cistercian abbey of Royaumont. In 1820 they were transferred and reinterred to Saint-Denis Basilica.[56]

Ancestry

[edit]| Ancestors of Louis IX of France | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Veneration as a saint

[edit]Louis | |

|---|---|

San Luis, Rey de Francia (English: Saint Louis, King of France) by Francisco Pacheco | |

| King of France Confessor | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Anglican Communion |

| Canonized | 11 July 1297, Rome, Papal States by Pope Boniface VIII |

| Feast | 25 August |

| Attributes | The crown of thorns, crown, sceptre, globus cruciger, sword, fleur-de-lis, mantle, and the other parts of the French regalia |

| Patronage | |

Pope Boniface VIII proclaimed the canonization of Louis in 1297;[57] he is the only French king to be declared a saint.[58] Louis IX is often considered the model of the ideal Christian monarch.[57]

Named in his honour, the Sisters of Charity of St. Louis is a Roman Catholic religious order founded in Vannes, France, in 1803.[59] A similar order, the Sisters of St Louis, was founded in Juilly in 1842.[60][61]

He is honoured as co-patron of the Third Order of St. Francis, which claims him as a member of the Order. When he became king, over a hundred poor people were served meals in his house on ordinary days. Often the king served these guests himself. His acts of charity, coupled with his devout religious practices, gave rise to the legend that he joined the Third Order of St. Francis, though it is unlikely that he ever actually joined the order.[9]

The Catholic Church and Episcopal Church honor him with a feast day on 25 August.[62][63]

Things named after Saint Louis

[edit]- The French royal Order of Saint Louis (1693–1790 and 1814–1830)[64]

Places

[edit]Many countries in which French speakers and Catholicism were prevalent named places after King Louis:

- San Luis Province in Argentina[65]

- San Luis Potosí in Mexico[66]

- Multiple locations in the United States

- St. Louis, Missouri, named by French colonists[67]

- St. Louis County, Missouri

- St. Louis County, Minnesota

- San Luis Rey, Oceanside, California, named by the Franciscans who built one of the California missions there.

- San Luis, Colorado

- Multiple locations in France[67]

- Île Saint-Louis, an island in the river Seine, Paris[68]

- Saint-Louis, New Caledonia

- Multiple locations in Canada[67]

- Saint-Louis, Senegal[67]

- São Luís, Maranhão in Brazil[69]

- The Philippines

Buildings

[edit]- France

- Hôpital Saint-Louis, hospital in the 10th arrondissement of Paris[72]

- The Cathédrale Saint-Louis de Versailles in Versailles[73]

- United States

- The Basilica of St. Louis, King of France, completed in 1834 in St. Louis, Missouri[74]

- The Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis, completed in 1914 in St. Louis, Missouri[75]

- The Cathedral-Basilica of Saint Louis, King of France (St. Louis Cathedral), completed in 1850s in New Orleans, Louisiana[76]

- The Saint Louis Roman Catholic Church and School in Clarksville, Maryland, established in 1855 and 1923, respectively.

- Saint Louis Catholic Church and School in Fairfax County, Virginia.

- The St. Louis King of France Catholic Church and School, in Metairie, Louisiana[77]

- Saint Louis Catholic High School, in Lake Charles, Louisiana

- St. Louis the King Catholic Church, in Marquette, Michigan

- Saint Louis King of France Catholic Church and School, in Austin, Texas

- Saint Louis Catholic Church, in Waco, Texas

- Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, Oceanside, California, founded 12 June 1798

- San Luis Rey Mission, Chamberino, New Mexico

- St. Louis Roman Catholic Church in Buffalo, New York[78] (Mother Church of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Buffalo)[79]

- St. Louis Catholic Church and School, Castroville, Texas [80]

- The national church of France in Rome: San Luigi dei Francesi in Italian, or Saint Louis of France in English[81]

- The Cathedral of St Louis in Plovdiv, Bulgaria[82]

- The Cathedral of St Louis in Carthage, Tunisia, so named because Louis IX died at that approximate location in 1270[83]

- The Church of St Louis in Moscow, Russia[84]

- India

- Rue Saint Louis of Pondicherry[85]

- St. Louis Church, Dahisar West, Mumbai[86]

- The Convent of Saint Louis and Catholic High School in Carrickmacross, Ireland.

Notable portraits

[edit]France

- The Equestrian Statue of Louis IX, Paris, by Hippolyte Lefèbvre, which stands outside of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart at Montmartre.[87]

United States

- A bas-relief of St. Louis is one of the carved portraits of historic lawmakers that adorn the chamber of the United States House of Representatives.

- Saint Louis is also portrayed on a frieze depicting a timeline of important lawgivers throughout world history, on the North Wall of the Courtroom at the Supreme Court of the United States.[88]

- A statue of St. Louis by the sculptor John Donoghue stands on the roofline of the New York State Appellate Division Court at 27 Madison Avenue in New York City.

- The Apotheosis of St. Louis is an equestrian statue of the saint, by Charles Henry Niehaus, that stands in front of the Saint Louis Art Museum in Forest Park.

- A heroic portrait by Baron Charles de Steuben hangs in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Baltimore. An 1821 gift of King Louis XVIII of France, it depicts St. Louis burying his plague-stricken troops before the siege of Tunis at the beginning of the Eighth Crusade in 1270.

In fiction

[edit]- Louis IX, play by Jacques-François Ancelot, 1819

- Davis, William Stearns, "Falaise of the Blessed Voice" aka "The White Queen". New York: Macmillan, 1904

- Peter Berling, The Children of the Grail

- Jules Verne, "To the Sun?/Off on a Comet!" A comet takes several bits of the Earth away when it grazes the Earth. Some people, taken up at the same time, find the Tomb of Saint Louis is one of the bits, as they explore the comet.

- Adam Gidwitz, The Inquisitor's Tale

- Dante Alighieri, Divina Commedia. It is likely that Dante hides the figure of the Saint King behind the Veltro, the Messo di Dio, the Veglio di Creta and the "515", which is a duplicate of the Messo. This is a trinitarian representation to oppose to the analogous representation of his grandson Philip IV the Fair, as the Beast from the Sea. The idea came to Dante from the transposition of the Revelation of St. John in the history, studied from the abbot and theologian Joachim of Fiore.[89]

- Theodore de Bainville, poem, "La Ballade des Pendus (Le Verger du Roi Louis)"; musicalized by Georges Brassens.

Music

[edit]- Arnaud du Prat, Paris canon; Rhymed, chanted office for St. Louis, 1290, Sens Bib. Mun. MS6, and elsewhere.

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet for Saint Louis, H.320, for 1 voice, 2 treble instruments (?) and continuo 1675.

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem santi Ludovici Regis Galliae canticum tribus vocibus cum symphonia, H.323, for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments and continuo (1678 ?)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem Sancti Ludovici regis Galliae, H.332, for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments and continuo 1683)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem Sancti Ludovici regis Galliae canticum, H.365 & H.365 a, for soloists, chorus, woodwinds, strings and continuo (1690)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Motet In honorem Sancti Ludovici regis Galliae, H.418, for soloists, chorus, 2 flutes, 2 violins and continuo (1692–93)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Goyau, Georges. 'St. Louis IX.' The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company". 2013 [1910]. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Louis IX, king of France". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Collings, Andrew Jeffrey (2018). "The King Cannot be Everywhere: Royal Governance and Local Society in the Reign of Louis IX".

- ^ Bouquet, Martin (1840–1904). Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France. Tome 23 / [éd. par Dom Martin Bouquet,...] ; nouv. éd. publ. sous la dir. de M. Léopold Delisle,... (in French).

- ^ a b Bobineau, Olivier (8 December 2011). "Retour de l'ordre religieux ou signe de bonne santé de notre pluralisme laïc ?". Le Monde.fr (in French). Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ a b "The Pope Who Saved the Talmud". The 5 Towns Jewish Times. 15 June 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Vie de St Louis, ed. H.-F. Delaborde, Paris, 1899

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Richard 1983, p. xxiv.

- ^ a b "Saint Louis, King of France, Archdiocese of St. Louis, MO". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Fawtier, Robert (1973). "The Great Kings of the Dynasty". In Henneman, John Bell (ed.). The Medieval French Monarchy. The Dryden Press. p. 66.

- ^ Hanley 2016, pp. 234–235.

- ^ a b c "Louis IX". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2008.

- ^ a b c Fr. Paolo O. Pirlo, SHMI (1997). "St. Louis". My First Book of Saints. Sons of Holy Mary Immaculate – Quality Catholic Publications. pp. 193–194. ISBN 971-91595-4-5.

- ^ Sumption 1978, p. 15.

- ^ Richard 1983, p. 64.

- ^ Richard 1983, p. 65.

- ^ Shadis 2010, pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b c "St. Louis IX of France | EWTN". EWTN Global Catholic Television Network. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ Guerry, Emily (18 April 2019). "Dr". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Burning of the Talmud". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- ^ Goyau, Pierre-Louis-Théophile-Georges (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9.

- ^ Greer Fein, Susanna. "Art. 94, Enseignements de saint Lewis a Philip soun fitz: Introduction | Robbins Library Digital Projects". d.lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ O'Connell, David (1972). The teachings of Saint Louis; a critical text. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press. pp. 46–49.

- ^ William Chester Jordan, Louis IX and the Challenge of the Crusade: A Study in Rulership (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979), pp. 35–64, 135–181; and Jean Richard, Saint Louis, roi d'une France féodale, soutien de la Terre sainte (Paris: Fayard, 1983), ed. and abridged by Simon Lloyd, trans. Jean Birrell as Saint Louis: Crusader King of France (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 156–183.

- ^ a b Jean de Joinville, Life of Saint Louis

- ^ William of Auvergne

- ^ Gilson, Etienne (1991). The Spirit of Mediaeval Philosophy. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-268-01740-8.

- ^ Harran, Marilyn J. "Albertus Magnus, Saint." World Book Student. World Book, 2013. Web. Feb. 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, the Ste Chapelle (Paris-Buildings) in Grove Encyclopedia of Art

- ^ Rudolf Hiestand, 'The Military Orders and Papal Crusading Propaganda', in Victor Mallia-Milanes, The Military Orders Volume III: History and Heritage (London: Routledge, 2017), p. 155.

- ^ a b "Crusades: Crusades of the 13th century". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 787.

- ^ Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia; Sean L., Field (2013). The Sanctity of Louis IX: Early Lives of Saint Louis by Geoffrey of Beaulieu and William of Chartres. Cornell University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780801469138. Retrieved 3 March 2025.

- ^ Tyerman 2006, p. 796.

- ^ a b "Bréhier, Louis. "Crusades." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company". 2013 [1908]. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Jackson 1980, p. 481-513.

- ^ Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Durham, New Carolina: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813513041. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History. 33 (1): 1–44. ISSN 0021-910X. JSTOR 41933117.

- ^ Aigle, Denise (2005). "The Letters of Eljigidei, H¨uleg¨u and Abaqa: Mongol overtures or Christian Ventriloquism?" (PDF). Inner Asia. 7 (2): 143–162. doi:10.1163/146481705793646883. S2CID 161266055. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Jean de Joinville, Life of Saint Louis. 324–327, cap. 652–656.

- ^ Jean de Joinville, Life of Saint Louis. 324–327

- ^ "Louis IX - Peace, Reforms, Administration | Britannica".

- ^ "King Henry III".

- ^ Translation from Seventh Crusade, 47; Ibn Wasil, Mufarrij al-kurūb, 173-5

- ^ Ibn al-Dawadari, Kanz al-durar wa-jāmiʿ al-ghurar

- ^ J. Weitzel, 'Zur Zuständigkeit des Reichskammergerichts als Appellations gericht', ZSRG GA,90 (1973), 213–45; K. Perels, 'Die Justizverweigerung I'm alten Reiche seit 1495', ZSRG GA, 25 (1904), 1–51

- ^ Magill & Aves 1998, p. 606.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 1004.

- ^ Lock 2013, p. 183.

- ^ Westerhof 2008, p. 79.

- ^ Gaposchkin 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Gaposchkin 2008, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Gaposchkin 2008, pp. 28–30, 76.

- ^ Jordan 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Jordan 2017, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Brown 1990, p. 810.

- ^ a b Louis IX, Oxford Dictionary of Saints, (Oxford University Press, 2004), 326.

- ^ McHenry, Robert (1993). "Louis". The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia. Vol. 7 (15th ed.). p. 497. ISBN 978-0852295717.

- ^ "Who We Are". Sisters of Charity of St. Louis. 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Our Father and Patron St. Louis / St. Louis, King of France, 1214–1270 AD" St. Louis Handbook for Schools. Sisters of St Louis. p. 8.

- ^ "Our history". Sisters of St Louis. 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Optional Memorial of Saint Louis of France | USCCB". bible.usccb.org. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- ^ Mazas, Alexandre (1860). Histoire de l'ordre royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis depuis son institution en 1693 jusqu'en 1830 (in French). Firmin Didot frères, fils et Cie. p. 28.

- ^ "San Luis". Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Historia". City of San Luis Potosí (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Everett-Heath, John (2018). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 1436. ISBN 978-0-19-256243-2.

- ^ "Ile Saint Louis – Paris". francemonthly.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (2018). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. p. 1369. ISBN 978-0-19-256243-2.

- ^ "Municipality of San Luis | Provincial Government of Aurora". Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "San Luis, Batangas: Historical Data". Batangas History, Culture & Folklore. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Histoire de l'hôpital Saint-Louis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ "Versailles Saint-Louis Cathedral: guided tour". ParisCityVision.com. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "History & the Story of St. Louis IX". Basilica of Saint Louis, King of France. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "Brief History of the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis". The Cathedral Basilica of St. Louis. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "Our History". Cathedral-Basilica of Saint Louis King of France. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "St. Louis King of France Catholic School". St. Louis King of France Catholic School.

- ^ "History – St. Louis RC Church".

- ^ "Saint Louis Roman Catholic Church in Buffalo, US".

- ^ "St. Louis Church Castroville".

- ^ Bassani Grampp, Florian (August 2008). "On a Roman Polychoral Performance in August 1665". Early Music. 36 (3): 415–433. doi:10.1093/em/can095. JSTOR 27655211. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Plovdiv, Visit. "Catholic Cathedral 'Saint Louis'". visitplovdiv.com. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ Artaud de La Ferrière, Alexis (May 2019). "Listen Articles The Catholic Church in Tunisia: a transliminal institution between religion and nation". The Journal of North African Studies. 25 (3): 415–446. doi:10.1080/13629387.2019.1611428. S2CID 164493102.

- ^ "Приход св. Людовика в Москве – Приход св. Людовика в Москве". ru.eglise.ru. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Stock Photo – Rue Saint Louis in Pondicherry India". Alamy. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "St. Louis Church". stlouischurchdahisar.in. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Equestrian statue of Louis IX in Paris France". Equestrian statues. 6 April 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ "US Supreme Court Courtroom Friezes" (PDF). Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Lombardi, Giancarlo (2022). L'Estetica Dantesca del Dualismo (in Italian). Borgomanero, Novara, Italy: Giuliano Ladolfi Editore. ISBN 978-8866446620.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brown, Elizabeth A. R. (Autumn 1990). "Authority, the Family, and the Dead in Late Medieval France". French Historical Studies. 16 (4): 803–832. doi:10.2307/286323. JSTOR 286323.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1928-0290-9.

- Davis, Jennifer R. (Autumn 2010). "The Problem of King Louis IX of France: Biography, Sanctity, and Kingship". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 41 (2): 209–225. doi:10.1162/JINH_a_00050. S2CID 144928195.

- Dupuy, Trevor N. (1993). The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-062-70056-8. OL 1715499M.

- Gaposchkin, M. Cecilia (2008). The Making of Saint Louis: Kingship, Sanctity, and Crusade in the Later Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-47625-9. OL 16365443M.

- Hanley, Catherine (2016). Louis: The French Prince who invaded England. Yale University Press.

- Jackson, Peter (July 1980). "The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260". The English Historical Review. 95 (376): 481–513. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCV.CCCLXXVI.481. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 568054.

- Jordan, William Chester (1979). Louis IX and the Challenge of the Crusade: A Study in Rulership. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05285-4. OL 4433805M.

- —— (2017). "A Border Policy? Louis IX and the Spanish Connection". In Liang, Yuen-Gen; Rodriguez, Jarbel (eds.). Authority and Spectacle in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: Essays in Honor of Teofilo F. Ruiz. Routledge. OL 33569507M.

- Le Goff, Jacques (2009). Saint Louis. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 978-0-268-03381-1.

- Lock, Peter (2013). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-13137-1.

- Magill, Frank Northen; Aves, Alison, eds. (1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The Middle Ages. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 1-5795-8041-6.

- Shadis, Miriam (2010). Berenguela of Castile (1180–1246) and Political Women in the High Middle Ages. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23473-7.

- Richard, Jean (1983). Lloyd, Simon (ed.). Saint Louis: Crusader King of France. Translated by Birrell, Jean. Cambridge University Press.

- Streyer, J.R. (1962). "The Crusades of Louis IX". In Setton, K.M. (ed.). A History of the Crusades. Vol. II. pp. 487–521.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1978). The Albigensian Crusade. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-20002-3. OL 7857399M.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Westerhof, Danielle (16 October 2008). Death and the Noble Body in Medieval England. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-843-83416-8.

External links

[edit]- John de Joinville. Memoirs of Louis IX, King of France. Chronicle, 1309.

- Saint Louis in Medieval History of Navarre

- Site about The Saintonge War between Louis IX of France and Henry III of England.

- Account of the first Crusade of Saint Louis from the perspective of the Arabs..

- A letter from Guy, a knight, concerning the capture of Damietta on the sixth Crusade with a speech delivered by Saint Louis to his men.

- Etext full version of the Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville, a biography of Saint Louis written by one of his knights

- "St. Lewis, King of France", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- "Man of the Middle Ages, Saint Louis, King of France", Archdiocese of St. Louis, MO Archived 26 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

Louis IX of France

View on GrokipediaSources and Historiography

Primary Sources

The principal eyewitness account of Louis IX's life and character is provided by Jean de Joinville's Vie de Saint Louis, a memoir composed circa 1309 by the seneschal of Champagne, who accompanied the king on the Seventh Crusade from 1248 to 1254. Joinville's work draws on personal observations, offering detailed narratives of Louis's piety, judicial practices, and conduct during captivity in Egypt, though it emphasizes moral exemplars over strict chronology.[7] Hagiographical vitae by Dominican friars close to the king form another core set of sources. Geoffrey of Beaulieu, Louis's confessor from 1237 onward, authored the Vita Ludovici noni between 1250 and circa 1275, focusing on the monarch's devotional life, miracles attributed to him, and saintly virtues witnessed firsthand, including during the crusade. Similarly, William of Chartres, a Dominican preacher who traveled with Louis to Tunis in 1270, composed a vita highlighting the king's humility and asceticism, based on direct interactions and posthumous testimonies gathered for canonization proceedings initiated in 1272. These texts, while shaped by religious agendas to promote sanctity, preserve contemporary details of Louis's routines, such as his daily prayers and almsgiving.[8] Royal administrative records, including charters, ordinances, and letters patent preserved in the Trésor des chartes, document Louis's governance, such as the 1254 ordinance reforming royal officials and his 1268 instructions on justice. These edicts, issued directly from the king's chancery, reveal policy intents with precise dates and addressees, like the establishment of the parlement de Paris in 1250 for appellate review. Chronicles compiled under royal auspices, such as entries in the Grandes Chroniques de France derived from earlier annals at Saint-Denis, incorporate official notices of events like the Treaty of Paris (1259) and the Eighth Crusade's launch in 1270, though later redactions introduce interpretive layers. Papal and episcopal correspondence, including Innocent IV's letters during the 1240s Albigensian conflicts, further corroborate diplomatic and ecclesiastical interactions.[8]Modern Scholarship

Modern scholarship on Louis IX emphasizes his role as a pivotal Capetian monarch who centralized royal authority through administrative and judicial innovations, while critiquing the material and human costs of his crusading enterprises. Historians such as William Chester Jordan argue that the Seventh Crusade (1248–1254) represented a strategic overreach driven by Louis's vow during illness, resulting in the capture of Damietta but ultimate defeat and ransom payments exceeding 1 million bezants, which strained French finances without lasting territorial gains. Jordan's analysis highlights causal links between Louis's piety and policy failures, portraying the expedition as a product of messianic expectations rather than pragmatic diplomacy, though it indirectly bolstered his domestic prestige upon return.[9] Thematic studies further explore Louis's religious worldview shaping governance, with Jacques Le Goff's biography depicting him as a "prud'homme"—a figure of probity blending feudal knighthood with monastic asceticism—who enforced moral reforms amid 13th-century challenges like heresy and fiscal instability.[10] Le Goff contends that Louis's personal devotions, including daily Masses and almsgiving documented at over 100,000 livres parisis annually, informed legal measures like the enquêtes générales of 1247–1248, which investigated local corruption and recovered royal domains valued at thousands of livres.[11] This integration of sanctity and statecraft is seen as causally enabling the expansion of the Parlement de Paris into a permanent appellate court by 1254, reducing seigneurial abuses and standardizing coinage to combat debasement.[12] Posthumous image-making receives scrutiny in M. Cecilia Gaposchkin's work, which traces the canonization process initiated by Philip IV and approved by Boniface VIII in 1297, revealing how crusade narratives and miracle accounts—over 70 reported at his tomb—were politically leveraged to legitimize Capetian rule. Gaposchkin notes that early cult promotion, including translations of relics in 1306, emphasized Louis's exemplary kingship over mere thaumaturgy, countering scholastic doubts about lay sanctity amid rising papal influence.[13] Recent assessments, including Jordan's examination of missionary efforts, underscore Louis's targeted conversions of Muslims during captivity (1249–1250), involving incentives like subsidies for over 100 converts, as reflective of Augustinian theology rather than coercion, though outcomes were limited by cultural resistance.[14] Collectively, these studies privilege archival evidence from royal registers and chronicles, cautioning against anachronistic projections of tolerance while affirming Louis's empirical successes in fiscal stabilization and judicial equity as foundations for France's medieval state-building.[2]Early Life and Minority

Birth and Family Background

Louis IX was born on 25 April 1214 at Poissy, a royal residence near Paris in the Île-de-France region.[15][16] He was baptized shortly after, receiving the name Louis in honor of familial tradition, and was the second surviving son of his parents, though an elder brother, Philip, born in 1209, had died in infancy by 1218, positioning Louis as the heir apparent.[15] His father, Louis VIII (born 1187), had ascended the French throne in 1223 following the death of his own father, Philip II Augustus, whose conquests had significantly expanded Capetian domains, including Normandy and parts of the south after the Albigensian Crusade.[17] Louis VIII's marriage to Louis IX's mother, Blanche of Castile (born 1188), occurred in 1200 as a diplomatic alliance arranged by Philip II to secure ties with the Kingdom of Castile; Blanche was the daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile and Eleanor of England, the latter being a daughter of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine, thus linking the French royal house to Plantagenet and Aquitainian lineages.[15][17] The couple produced eleven children in total, with Louis IX as the eldest surviving male, followed by siblings including Robert (born 1216), John (born circa 1219, died young), Alphonse (born 1220), Charles (born 1227), and several daughters; this large progeny reflected the era's emphasis on securing dynastic continuity amid high infant mortality.[15] Louis VIII's early death in 1226 from dysentery during a southern campaign elevated the twelve-year-old Louis IX to the throne, with Blanche assuming regency duties informed by her own experiences in Iberian and English courts.[16]Regency under Blanche of Castile

Upon the death of Louis VIII from dysentery on November 8, 1226, at Montpensier while returning from the Albigensian Crusade, his widow Blanche of Castile assumed the regency for their twelve-year-old son, Louis IX.[18] [19] Blanche, a Castilian princess born in 1188 as the daughter of Alfonso VIII of Castile and Eleanor of England, had married Louis VIII in 1200 to secure an alliance against England.[15] She swiftly arranged Louis IX's coronation on November 29, 1226, at Notre-Dame de Reims to legitimize his rule and invoke sacral kingship traditions.[20] [21] Blanche's regency, lasting until 1234, confronted immediate baronial opposition fueled by resentment toward her foreign origins and perceived threats to feudal privileges.[22] Nobles, including Hugues X de Lusignan and Pierre Mauclerc (Duke of Brittany), formed leagues in 1226–1227 to exploit the minority, spreading rumors impugning Blanche's morality to erode her authority.[23] She countered by allying with loyalists like Theobald IV of Champagne, who provided military aid, and leveraging urban bourgeois support through financial appeals and exemptions.[23] [15] Blanche also mobilized the emerging mendicant orders—Dominicans and Franciscans—to preach obedience to the crown and rally popular sentiment against the rebels, marking an early use of religious networks for political stabilization.[24] A central challenge was concluding the Albigensian Crusade against southern heresy and autonomy. Blanche inherited her husband's campaign against Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse, who controlled Languedoc strongholds.[24] Through papal legates and military pressure, she negotiated the Treaty of Paris on April 12, 1229, whereby Raymond submitted, ceding key territories like the Agenais and paying a massive indemnity of 10,000 marks silver; his daughter Joan wed Louis IX's brother Alphonse of Poitiers to bind the region dynastically.[25] [26] This pacified the south without full extermination, though enforcement persisted via royal seneschals. Concurrently, Blanche repelled English incursions backed by Henry III, who aided baronial rebels, and subdued Pierre Mauclerc's Breton defiance by 1234, capturing him briefly and extracting homage.[23] [24] By 1234, with Louis IX reaching maturity, Blanche orchestrated his marriage to Margaret of Provence on May 27 to forge alliances, formally ending the regency while retaining advisory influence.[22] Her governance consolidated Capetian authority, centralizing administration through bailiffs and emphasizing royal justice over feudal anarchy, laying foundations for Louis's later reforms.[27]Domestic Policies and Reforms

Legal and Judicial Reforms

Louis IX emphasized impartial justice as a core aspect of kingship, personally adjudicating disputes under the oak tree at Vincennes to ensure accessibility and fairness in royal judgments. His reforms aimed to curb corruption among local officials, such as baillis and sergeants, by enforcing ethical standards and enhancing royal oversight, reflecting a commitment to moral governance over feudal arbitrariness.[28] In 1247, prior to embarking on the Seventh Crusade, Louis dispatched enquêteurs—royal investigators—to tour the realm, soliciting public complaints against administrative abuses and examining the conduct of royal agents. These commissions uncovered widespread extortion and malfeasance, leading to the removal or punishment of several baillis, the restitution of ill-gotten gains to victims, and the codification of procedures for future inquiries, thereby strengthening direct royal control over local justice. This initiative marked an early use of systematic administrative audits to enforce accountability, bypassing entrenched local powers. Upon his return from crusade in 1254, Louis promulgated the Great Ordinance, a comprehensive decree reforming judicial and administrative practices.[29] It required baillis and other officers to deliver justice without favoritism, prohibited acceptance of gifts or bribes, mandated penalties only after formal inquiry rather than ordeal or combat, and imposed residency requirements on officials to prevent absentee mismanagement.[28] The ordinance also banned judicial duels in royal courts, favoring evidentiary hearings, and extended protections against arbitrary seizures, contributing to a shift toward more rational, record-based adjudication.[20] Louis further centralized appellate jurisdiction by regularizing sessions of the curia regis as a dedicated judicial body, precursor to the Parlement de Paris, where nobles and clerics reviewed lower court decisions and enforced royal edicts.[30] This development, active from the 1250s, prioritized appeals from subjects aggrieved by seigneurial or municipal courts, elevating royal authority while providing remedies for injustices; by the 1260s, it handled hundreds of cases annually, fostering uniformity in French law.[31] To underscore personal responsibility, Louis ordered restitution from his treasury for harms caused by corrupt agents under prior reigns, exemplifying accountability at the sovereign level.[32] These measures, though limited by medieval enforcement challenges, laid foundations for absolutist judicial centralization, reducing reliance on feudal customs and trial by battle.[12]Economic and Administrative Measures

Louis IX centralized royal administration by establishing and empowering baillis in northern provinces and seneschals in the south as salaried, itinerant officials tasked with judicial oversight, tax collection, and enforcement of royal edicts, thereby reducing feudal fragmentation.[12] To curb corruption among these agents, he dispatched pairs of enquêteurs—special investigators—who toured the realm to gather complaints, audit finances, and recommend redress, a practice initiated around 1247 and intensified post-crusade.[33] The 1254 administrative ordinance, drawn from enquête findings, prescribed ethical standards for baillis and seneschals, including prohibitions on gift-taking, usury, and conflicts of interest, while mandating regular rotations and financial accountability to the crown; a follow-up edict in 1256 extended these reforms with moral strictures against gambling and oath-breaking among officials.[2] These measures enhanced royal oversight, with surviving records showing dismissals and restitutions for abuses, though enforcement relied on the king's personal authority and periodic audits rather than permanent bureaucracy.[12] On the economic front, Louis addressed monetary instability exacerbated by wartime debasements through the 1266 reform, which on July 12 introduced the gros tournois—a silver coin weighing about 4 grams and valued at 12 deniers—as the standard for the sou tournois, minted solely at royal workshops to unify reckoning and boost trade confidence.[34] This initiative, alongside gold écu issuance, aimed to supplant feudal coinages and curb counterfeiting by enforcing exclusive royal minting rights, fostering economic integration amid post-crusade recovery.[35] His policies indirectly supported commerce by quelling noble feuds via truces and judicial interventions, enabling safer markets and fairs, though heavy crown taxation on towns strained urban finances.[36]Patronage of Arts, Scholarship, and Architecture

Louis IX commissioned the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris as a royal chapel to house relics acquired from Constantinople, including the Crown of Thorns, with construction beginning in 1239 and the chapel consecrated on April 26, 1248.[37] This structure exemplifies the Rayonnant Gothic style, characterized by expansive stained-glass windows and intricate stone tracery, reflecting the king's emphasis on luminous, relic-centric sacred spaces.[1] His architectural patronage extended to other projects, such as the expansion of the abbey at Royaumont and fortifications like the Louvre, though these were often tied to religious or defensive purposes rather than purely aesthetic innovation.[38] In scholarship, Louis IX supported theological education by endorsing the foundation of the Collège de Sorbon in 1257, established by his chaplain Robert de Sorbon to provide housing and resources for poor theology students at the University of Paris.[39] He confirmed the college's charter and provided additional properties, fostering an environment where mendicant friars and secular scholars could engage in advanced studies.[40] The king frequently hosted leading intellectuals, including Dominican Thomas Aquinas and Franciscan Bonaventure, at his table for discussions on theology and philosophy, demonstrating his personal commitment to intellectual pursuits aligned with Dominican and Franciscan orders.[41][42] Louis IX's patronage of the arts included commissioning illuminated manuscripts and ivories that advanced courtly and devotional imagery, such as those possibly linked to his biblical picture cycles.[43] His support for mendicant orders facilitated the production of theological texts and visual aids for preaching, contributing to the integration of art with scholarly dissemination during his reign.[44] Overall, this patronage not only elevated French Gothic aesthetics but also reinforced the Capetian monarchy's alliance with ecclesiastical learning, prioritizing works that served pious and propagandistic functions over secular entertainment.[45]Religious Policies and Piety

Personal Devotion and Church Support

Louis IX's personal devotion was profoundly shaped by his mother, Blanche of Castile, who instilled in him habits of prayer and liturgical participation from childhood; he regularly attended Mass and developed a deep commitment to Christian worship.[38] As king, he maintained rigorous spiritual disciplines, including attending Mass twice daily, reciting the Divine Office each day, and wearing a hairshirt as a penitential practice beneath his royal garments.[46] [47] His piety extended to frequent confession, communion, and veneration of relics, embodying a comprehensive engagement with contemporary forms of Catholic devotion.[48] In support of the Church, Louis IX commissioned the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris between 1241 and 1248 as a royal chapel to enshrine relics of the Passion, notably the Crown of Thorns acquired from Baldwin II of Constantinople in 1239 for 135,000 livres—purchased personally to safeguard these sacred objects from sale to non-Christians.[49] [50] The chapel's construction, completed and consecrated in 1248, exemplified his architectural patronage for ecclesiastical purposes, featuring innovative Rayonnant Gothic design to glorify divine relics.[49] Louis provided substantial almsgiving and founded institutions aligned with Church teachings, including hospitals and abbeys, while defending clerical interests without granting undue privileges; he allocated fines from offenders to religious and charitable works.[51] His fidelity to papal authority and efforts to enforce orthodoxy contributed to his canonization in 1297 by Pope Boniface VIII, recognizing his exemplary Christian kingship marked by personal austerity and institutional support for the faith.[46]Measures Against Heresy and Non-Christians

Louis IX rigorously enforced Catholic orthodoxy within his realm, expanding the scope of the papal Inquisition established in the 1230s to combat lingering heretical movements, particularly remnants of Catharism in southern France following the Albigensian Crusade's conclusion via the Treaty of Paris in 1229.[52] In 1249, he instructed his barons to prosecute heretics in accordance with ecclesiastical directives, thereby integrating secular authority with inquisitorial procedures to root out deviations from doctrine.[53] He prescribed severe penalties for blasphemy, including mutilation of the tongue and lips, as a deterrent against challenges to Christian teachings.[54] Regarding non-Christians, Louis IX's policies targeted Jewish communities, whom he viewed as obstacles to Christian unity due to perceived blasphemies in their texts. In 1240, he convened the Disputation of Paris, a public trial of the Talmud initiated at the urging of apostate Jew Nicholas Donin, resulting in the confiscation and public burning of approximately 10,000 to 12,000 Jewish manuscripts—equivalent to 24 cartloads—in Paris in 1242.[55][56] This act, endorsed by papal bull from Innocent IV in 1244, aimed to eliminate writings deemed injurious to Christianity.[57] Further edicts in December 1254 prohibited Jews from retaining copies of the Talmud or other banned rabbinic texts under threat of expulsion, barred them from charging interest to Christians (requiring restitution of prior usury profits), and restricted their economic activities to manual labor or permitted commerce, enforcing the Fourth Lateran Council's mandate for a distinctive yellow badge (rouelle) to identify Jews publicly.[58] These measures sought to compel conversion—Louis personally sponsored baptisms and debated rabbis—while prohibiting Jews from employing Christian servants or holding positions of authority over Christians, though he refrained from physical violence against them in line with papal prohibitions.[59] Policies toward Muslims (Saracens) were minimal domestically, as their presence in France was negligible, with Louis's primary confrontations occurring via crusades abroad rather than internal ordinances.[60]Foreign Relations and Crusades

Diplomacy with Neighboring Powers

Louis IX sought to resolve longstanding territorial ambiguities with neighboring powers through negotiated settlements, prioritizing the establishment of clear feudal hierarchies and borders over military conquest. This approach reflected his preference for arbitration and mutual concessions, often involving the renunciation of nominal overlordships inherited from Carolingian or Capetian claims in exchange for formal homage and defined suzerainty. Such diplomacy stabilized France's frontiers, allowing Louis to focus resources on internal reforms and crusading endeavors without the drain of peripheral conflicts.[61][62] Relations with England centered on resolving disputes stemming from the Angevin empire's losses under Philip II Augustus. After years of intermittent warfare and failed truces, Louis initiated talks in 1254 upon his return from the Seventh Crusade, culminating in the Treaty of Paris signed on 4 December 1259 at Paris between Louis and Henry III. Under its terms, Henry III formally renounced English claims to Normandy, Maine, Poitou, Anjou, and Touraine—territories lost to France since 1204—and acknowledged Louis as his liege lord for Gascony and Guyenne, rendering Henry a direct vassal. In return, Louis restored to Henry the sovereignty of Limousin, Quercy, and Périgord (including cities like Limoges, Cahors, and Périgueux), which had been annexed by France in 1259, and agreed to a financial indemnity of 15,000 marks to facilitate the transfer. This settlement ended Plantagenet pretensions to the French throne and integrated southwestern France more firmly under Capetian overlordship, though it sowed seeds of future Anglo-French rivalry by preserving English continental holdings.[63][61][64] To the south, Louis addressed border frictions with the Crown of Aragon, which had expanded into former Carolingian marchlands. The Treaty of Corbeil, concluded on 11 May 1258 at Corbeil between Louis and envoys of James I of Aragon (and ratified by James on 16 July 1258), demarcated spheres of influence: Louis relinquished French suzerainty over Catalonia, Roussillon, and other eastern Pyrenean territories, while James I abandoned Aragonese claims to Languedoc, Provence, and the County of Toulouse, retaining only the lordship of Montpellier. This pact clarified the Pyrenean frontier, reducing incentives for proxy conflicts via Occitan nobles, and facilitated marital ties, including the later 1260 betrothal of Louis's son Philip (future Philip III) to Isabella, daughter of James I, further cementing the alliance.[65][62] Diplomacy with Iberian kingdoms like Castile emphasized familial and strategic alliances to secure the southwestern flank, leveraging Louis's mother Blanche of Castile's connections. Louis supported Castilian campaigns against Muslim taifas through indirect aid and arbitration, while marital diplomacy—such as the 1235 marriage of his sister Isabella to Theobald IV of Champagne (with Navarrese ties) and negotiations with Ferdinand III—aimed at countering Aragonese influence without direct confrontation. With the Holy Roman Empire, Louis adopted a stance of benevolent neutrality amid the post-Frederick II interregnum after 1250, avoiding entanglement in the 1257 double election of Richard of Cornwall and Alfonso X of Castile as rival kings of the Romans, and instead focusing correspondence on ecclesiastical matters to preserve border tranquility along the Rhine and Savoy. These efforts underscored Louis's broader foreign policy of eschewing expansionism for juridical clarity and Christian concord among Catholic monarchs.[62][2]Seventh Crusade

Louis IX vowed to lead a crusade in December 1244, motivated by the recent sack of Jerusalem by Khwarezmian forces allied with the Ayyubids.[66] Preparations involved raising funds through taxes, including a twentieth on church revenues, and assembling an army estimated at 15,000 to 35,000 men, including knights, crossbowmen, and infantry, accompanied by his brothers Robert of Artois, Alphonse of Poitiers, and Charles of Anjou.[67][68] The fleet departed from the newly built port of Aigues-Mortes on 25 August 1248, wintering in Cyprus before proceeding to Egypt in 1249, aiming to conquer the wealthy Nile Delta as a base to pressure for Jerusalem's return.[68][69] The Crusaders landed near Damietta on 5 June 1249 and captured the city on 6 June with minimal resistance, as the Ayyubid garrison under Sultan As-Salih Ayyub withdrew up the Nile amid flooding and the sultan's illness.[70][71] Louis fortified Damietta as a supply base but delayed advance until November 1249 due to Nile floods, then marched southward toward Cairo, crossing to the east bank at Gharbia and besieging Al-Mansurah by late December.[69] Disease and supply shortages plagued the army, exacerbated by scorched-earth tactics from Egyptian forces.[70] The Battle of Al-Mansurah unfolded from 8 to 11 February 1250, where Crusader knights initially broke through Egyptian lines led by Emir Fakhr-ad-Din Yusuf, but Robert of Artois impulsively pursued into the city, leading to his death along with key nobles like the Earl of Salisbury and 285 Templars in ambushes by Baibars' forces.[70][72] Louis regrouped and held positions briefly but faced counterattacks and dysentery outbreaks, forcing a retreat toward Damietta; on 6 April 1250, at Fariskur, the rearguard was overwhelmed, resulting in Louis's capture alongside thousands of survivors.[73][74] Negotiations secured Louis's release in May 1250 after agreeing to a ransom of 800,000 bezants for captives and the surrender of Damietta, which was handed over in exchange for the king's freedom.[75][76] Rather than return immediately, Louis sailed to Acre, where he remained until 1254, mediating truces between Christian factions and Ayyubid successors, including aiding fortification of Caesarea and Sidon, though the crusade failed to regain Jerusalem and incurred massive costs exceeding 1.5 million livres tournois.[77][75] Chronicler Jean de Joinville, who participated, portrayed the expedition as a trial of faith amid strategic miscalculations, with heavy losses from battle and illness underscoring logistical vulnerabilities against mobile Mamluk tactics.[78]Eighth Crusade and Death