Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Canonization

View on Wikipedia

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint,[1] specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of saints,[2] or authorized list of that communion's recognized saints.[3][4]

Catholic Church

[edit]

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

Canonization is a papal declaration that the Catholic faithful may venerate a particular deceased member of the church. Popes began making such decrees in the tenth century. Up to that point, the local bishops governed the veneration of holy men and women within their own dioceses; and there may have been, for any particular saint, no formal decree at all. In subsequent centuries, the procedures became increasingly regularized and the Popes began restricting to themselves the right to declare someone a Catholic saint. In contemporary usage, the term is understood to refer to the act by which any Christian church declares that a person who has died is a saint, upon which declaration the person is included in the list of recognized saints, called the "canon".[5]

Biblical roots

[edit]In the Roman Martyrology, the following entry is given for the Penitent Thief: "At Jerusalem, the commemoration of the good Thief, who confessed Christ on the cross, and deserved to hear from Him these words: 'This day thou shalt be with Me in paradise.'[6][7]

Historical development

[edit]The Roman Canon, the historical Eucharistic Prayer or Anaphora of Canon of the Roman Rite contains only the names of apostles and martyrs, along with that of the Blessed Virgin Mary and, since 1962, that of Saint Joseph her spouse.

By the fourth century, however, "confessors"—people who had confessed their faith not by dying but by word and life—began to be venerated publicly. Examples of such people are Saint Hilarion and Saint Ephrem the Syrian in the East, and Saint Martin of Tours and Saint Hilary of Poitiers in the West. Their names were inserted in the diptychs, the lists of saints explicitly venerated in the liturgy, and their tombs were honoured in like manner as those of the martyrs. Since the witness of their lives was not as unequivocal as that of the martyrs, they were venerated publicly only with the approval by the local bishop. This process is often referred to as "local canonization".[9]

This approval was required even for veneration of a reputed martyr. In his history of the Donatist heresy, Saint Optatus recounts that at Carthage a Catholic matron, named Lucilla, incurred the censures of the Church for having kissed the relics of a reputed martyr whose claims to martyrdom had not been juridically proved. And Saint Cyprian (died 258) recommended that the utmost diligence be observed in investigating the claims of those who were said to have died for the faith. All the circumstances accompanying the martyrdom were to be inquired into; the faith of those who suffered, and the motives that animated them were to be rigorously examined, in order to prevent the recognition of undeserving persons. Evidence was sought from the court records of the trials or from people who had been present at the trials.

Augustine of Hippo (died 430) tells of the procedure which was followed in his day for the recognition of a martyr. The bishop of the diocese in which the martyrdom took place set up a canonical process for conducting the inquiry with the utmost severity. The acts of the process were sent either to the metropolitan or primate, who carefully examined the cause, and, after consultation with the suffragan bishops, declared whether the deceased was worthy of the name of "martyr" and public veneration.

Though not "canonizations" in the narrow sense, acts of formal recognition, such as the erection of an altar over the saint's tomb or transferring the saint's relics to a church, were preceded by formal inquiries into the sanctity of the person's life and the miracles attributed to that person's intercession.

Such acts of recognition of a saint were authoritative, in the strict sense, only for the diocese or ecclesiastical province for which they were issued, but with the spread of the fame of a saint, were often accepted elsewhere also.

Nature

[edit]In the Catholic Church, both in the Latin and the constituent Eastern churches, the act of canonization is reserved to the Apostolic See and occurs at the conclusion of a long process requiring extensive proof that the candidate for canonization lived and died in such an exemplary and holy way that they are worthy to be recognized as a saint. The Church's official recognition of sanctity implies that the person is now in Heaven and that they may be publicly invoked and mentioned officially in the liturgy of the Church, including in the Litany of the Saints.

In the Catholic Church, canonization is a decree that allows universal veneration of the saint. For permission to venerate merely locally, only beatification is needed.[10]

Procedure prior to reservation to the Apostolic See

[edit]

For several centuries the bishops, or in some places only the primates and patriarchs,[11] could grant martyrs and confessors public ecclesiastical honor; such honor, however, was always decreed only for the local territory of which the grantors had jurisdiction. Only acceptance of the cultus by the Pope made the cultus universal, because he alone can rule the universal Catholic Church.[12] Abuses, however, crept into this discipline, due as well to indiscretions of popular fervor as to the negligence of some bishops in inquiring into the lives of those whom they permitted to be honoured as saints.

In the Medieval West, the Apostolic See was asked to intervene in the question of canonizations so as to ensure more authoritative decisions. The canonization of Saint Udalric, Bishop of Augsburg by Pope John XV in 993 was the first undoubted example of papal canonization of a saint from outside of Rome being declared worthy of liturgical veneration for the entire church.[13]

Thereafter, recourse to the judgment of the Pope occurred more frequently. Toward the end of the 11th century, the Popes began asserting their exclusive right to authorize the veneration of a saint against the older rights of bishops to do so for their dioceses and regions. Popes therefore decreed that the virtues and miracles of persons proposed for public veneration should be examined in councils, more specifically in general councils. Pope Urban II, Pope Calixtus II, and Pope Eugene III conformed to this discipline.

Exclusive reservation to the Apostolic See

[edit]Hugh de Boves, Archbishop of Rouen, canonized Walter of Pontoise, or St. Gaultier, in 1153, the final saint in Western Europe to be canonized by an authority other than the Pope:[14][15] "The last case of canonization by a metropolitan is said to have been that of St. Gaultier, or Gaucher, [A]bbot of Pontoise, by the Archbishop of Rouen. A decree of Pope Alexander III [in] 1170 gave the prerogative to the [P]ope thenceforth, so far as the Western Church was concerned."[14] In a decretal of 1173, Pope Alexander III reprimanded some bishops for permitting veneration of a man who was merely killed while intoxicated, prohibited veneration of the man, and most significantly decreed that "you shall not therefore presume to honor him in the future; for, even if miracles were worked through him, it is not lawful for you to venerate him as a saint without the authority of the Catholic Church."[16] Theologians disagree as to the full import of the decretal of Pope Alexander III: either a new law was instituted,[17] in which case the Pope then for the first time reserved the right of beatification to himself, or an existing law was confirmed.

However, the procedure initiated by the decretal of Pope Alexander III was confirmed by a bull of Pope Innocent III issued on the occasion of the canonization of Cunigunde of Luxembourg in 1200. The bull of Pope Innocent III resulted in increasingly elaborate inquiries to the Apostolic See concerning canonizations. Because the decretal of Pope Alexander III did not end all controversy and some bishops did not obey it in so far as it regarded beatification, the right of which they had certainly possessed hitherto, Pope Urban VIII issued the Apostolic letter Caelestis Hierusalem cives of 5 July 1634 that exclusively reserved to the Apostolic See both its immemorial right of canonization and that of beatification. He further regulated both of these acts by issuing his Decreta servanda in beatificatione et canonizatione Sanctorum on 12 March 1642.

Procedure from 1734 to 1738 to 1983

[edit]In his De Servorum Dei beatificatione et de Beatorum canonizatione of five volumes the eminent canonist Prospero Lambertini (1675–1758), who later became Pope Benedict XIV, elaborated on the procedural norms of Pope Urban VIII's Apostolic letter Caelestis Hierusalem cives of 1634 and Decreta servanda in beatificatione et canonizatione Sanctorum of 1642, and on the conventional practice of the time. His work published from 1734 to 1738 governed the proceedings until 1917. The article "Beatification and canonization process in 1914" describes the procedures followed until the promulgation of the Codex of 1917. The substance of De Servorum Dei beatifιcatione et de Beatorum canonizatione was incorporated into the Codex Iuris Canonici (Code of Canon Law) of 1917,[18] which governed until the promulgation of the revised Codex Iuris Canonici in 1983 by Pope John Paul II. Prior to promulgation of the revised Codex in 1983, Pope Paul VI initiated a simplification of the procedures.

Since 1983

[edit]The Apostolic constitution Divinus Perfectionis Magister of Pope John Paul II of 25 January 1983[19] and the norms issued by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints on 7 February 1983 to implement the constitution in dioceses, continued the simplification of the process initiated by Pope Paul VI.[19] Contrary to popular belief, the reforms did not eliminate the office of the Promoter of the Faith (Latin: Promotor Fidei), popularly known as the Devil's advocate, whose office is to question the material presented in favor of canonization. The reforms were intended to reduce the adversarial nature of the process. In November 2012 Pope Benedict XVI appointed Monsignor Carmello Pellegrino as Promoter of the Faith.[20]

Candidates for canonization undergo the following process:

- Servant of God (Servus Dei): The process of canonization commences at the diocesan level. A bishop with jurisdiction, usually the bishop of the place where the candidate died or is buried, although another ordinary can be given this authority, gives permission to open an investigation into the virtues of the individual in response to a petition of members of the faithful, either actually or pro forma.[21] This investigation usually commences no sooner than five years after the death of the person being investigated.[22] The Pope, qua Bishop of Rome, may also open a process and has the authority to waive the waiting period of five years, e.g., as was done for St. Teresa of Calcutta by Pope John Paul II,[23] and for Lúcia Santos and for Pope John Paul II himself by Pope Benedict XVI.[24][25] Normally, an association to promote the cause of the candidate is instituted, an exhaustive search of the candidate's writings, speeches, and sermons is undertaken, a detailed biography is written, and eyewitness accounts are collected. When sufficient evidence has been collected, the local bishop presents the investigation of the candidate, who is titled "Servant of God" (Latin: Servus Dei), to the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints of the Roman Curia, where the cause is assigned a postulator, whose office is to collect further evidence of the life of the Servant of God. Religious orders that regularly deal with the Congregation often designate their own Postulator General. At some time, permission is then granted for the body of the Servant of God to be exhumed and examined. A certification non-cultus is made that no superstitious or heretical worship, or improper cult of the Servant of God or her/his tomb has emerged, and relics are taken and preserved.

- Venerable (Venerabilis; abbreviated "Ven.") or "Heroic in Virtue": When sufficient evidence has been collected, the Congregation recommends to the Pope that he proclaim the heroic virtue of the Servant of God; that is, that the Servant of God exercised "to a heroic degree" the theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity and the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. From this time the one said to be "heroic in virtue" is entitled "Venerable" (Latin: Venerabilis). A Venerable does not yet have a feast day, permission to erect churches in their honor has not yet been granted, and the Church does not yet issue a statement on their probable or certain presence in Heaven, but prayer cards and other materials may be printed to encourage the faithful to pray for a miracle wrought by their intercession as a sign of God's will that the person be canonized.

- Blessed (Beatus or Beata; abbreviated "Bl."): Beatification is a statement of the Church that it is "worthy of belief" that the Venerable is in Heaven and saved. Attaining this grade depends on whether the Venerable is a martyr:The satisfaction of the applicable conditions permits beatification, which then bestows on the Venerable the title of "Blessed" (Latin: Beatus or Beata). A feast day will be designated, but its observance is ordinarily only permitted for the Blessed's home diocese, to specific locations associated with them, or to the churches or houses of the Blessed's religious order if they belonged to one. Parishes may not normally be named in honor of beati.

- For a martyr, the Pope has only to make a declaration of martyrdom, which is a certification that the Venerable gave their life voluntarily as a witness of the Faith or in an act of heroic charity for others.

- For a non-martyr, all of them being denominated "confessors" because they "confessed", i.e., bore witness to the Faith by how they lived, proof is required of the occurrence of a miracle through the intercession of the Venerable; that is, that God granted a sign that the person is enjoying the beatific vision by performing a miracle for which the Venerable interceded. Presently, these miracles are almost always miraculous cures of infirmity, because these are the easiest to judge given the Church's evidentiary requirements for miracles; e.g., a patient was sick with an illness for which no cure was known; prayers were directed to the Venerable; the patient was cured; the cure was spontaneous, instantaneous, complete, and enduring; and physicians cannot discover any natural explanation for the cure.

- Saint (Sanctus or Sancta; abbreviated "St." or "S."): To be canonized as a saint, ordinarily at least two miracles must have been performed through the intercession of the Blessed after their death, but for beati confessors, i.e., beati who were not declared martyrs, only one miracle is required, ordinarily being additional to that upon which beatification was premised. Very rarely, a Pope may waive the requirement for a second miracle after beatification if he, the Sacred College of Cardinals, and the Congregation for the Causes of Saints all agree that the Blessed lived a life of great merit proven by certain actions. This extraordinary procedure was used in Pope Francis' canonization of Pope John XXIII, who convoked the first part of the Second Vatican Council.

Canonization is a statement of the Church that the person certainly enjoys the beatific vision of Heaven. The title of "Saint" (Latin: Sanctus or Sancta) is then proper, reflecting that the saint is a refulgence of the holiness (sanctitas) of God himself, which alone comes from God's gift. The saint is assigned a feast day which may be celebrated anywhere in the universal Church, although it is not necessarily added to the General Roman Calendar or local calendars as an "obligatory" feast; parish churches may be erected in their honor; and the faithful may freely celebrate and honor the saint.

Although recognition of sainthood by the Pope does not directly concern a fact of Divine revelation, nonetheless it must be "definitively held" by the faithful as infallible pursuant to, at the least, the Universal Magisterium of the Church, because it is a truth related to revelation by historical necessity.[26][27]

Regarding the Eastern Catholic Churches, the cult of candidates for sainthood who have attained beatification in a sui juris Church is restricted to that Church. Canonization removes this restriction, and the saint is then venerated in the universal Church.[28]

Equipollent canonization

[edit]Popes have several times permitted to the universal Church, without executing the ordinary judicial process of canonization described above, the veneration as a saint, the "cultus" of one long venerated as such locally. This act of a Pope is denominated "equipollent" or "equivalent canonization"[29] and "confirmation of cultus".[30] In such cases, there is no need to have a miracle attributed to the saint to allow their canonization.[29] According to the rules Pope Benedict XIV (regnat 17 August 1740 – 3 May 1758) instituted, there are three conditions for an equipollent canonization: (1) existence of an ancient cultus of the person, (2) a general and constant attestation to the virtues or martyrdom of the person by credible historians, and (3) uninterrupted fame of the person as a worker of miracles.

Protestant denominations

[edit]The majority of Protestant denominations do not formally recognize saints because some think[who?] the Bible uses the term in a way that suggests all Christians are saints[citation needed]. However, some denominations do, as shown below.

Anglican Communion

[edit]The Church of England, the Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, canonized Charles I as a saint, in the Convocations of Canterbury and York of 1660.[31]

United Methodist Church

[edit]The General Conference of the United Methodist Church has formally declared individuals martyrs, including Dietrich Bonhoeffer (in 2008) and Martin Luther King Jr. (in 2012).[32][33]

Eastern Orthodox Church

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2020) |

Various terms are used for canonization by the autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Churches: канонизация[36] ("canonization") or прославление[37] ("glorification",[38] in the Russian Orthodox Church), კანონიზაცია (kanonizats’ia, Georgian Orthodox Church), канонизација (Serbian Orthodox Church), canonizare (Romanian Orthodox Church), and Канонизация (Bulgarian Orthodox Church). Additional terms are used for canonization by other autocephalous Eastern Orthodox Churches: αγιοκατάταξη[39] (Katharevousa: ἁγιοκατάταξις) agiokatataxi/agiokatataxis, "ranking among saints" (Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, Church of Cyprus, Church of Greece), kanonizim (Albanian Orthodox Church), kanonizacja (Polish Orthodox Church), and kanonizace/kanonizácia (Czech and Slovak Orthodox Church).

The Orthodox Church in America, an Eastern Orthodox Church partly recognized as autocephalous, uses the term "glorification" for the official recognition of a person as a saint.[40]

Oriental Orthodox Church

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2020) |

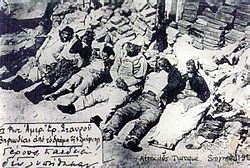

Within the Armenian Apostolic Church, part of Oriental Orthodoxy, there had been discussions since the 1980s about canonizing the victims of the Armenian genocide.[41] On 23 April 2015, all of the victims of the genocide were canonized.[42][43][44]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "canonize". Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ Charles Annandale. The Imperial Dictionary of the English Language, Volume 1; 1905. P. 386. Canon – A catalogue of saints acknowledged and canonized in the Roman Catholic Church.

- ^ CANON // Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume 3; 1913. – P. 255–256. – The name Canon (κανών) means a norm or rule; and it is used for various objects, such as the Canon of Holy Scripture, canons of Councils, the official list of saints' names (whence "canonization"), and the canon or list of clerks who serve a certain church, from which they themselves are called canons (canonici).

- ^ "Canonization". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ Copeland, Clare (2012). "Saints, Devotions and Canonisation in Early Modern Italy". History Compass. 10 (3): 260–269. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2012.00834.x. ISSN 1478-0542.

- ^ "Laudate Dominum – Roman Martyrology – March".

- ^ Clark, John (3 April 2015). "Canonized from the Cross: How St Dismas Shows it's Never Too Late..." Seton Magazine. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Kemp (1948).

- ^ For the history of such canonization, see Kemp.[8]

- ^ "Beatification, in the present discipline, differs from canonization in this: that the former implies (1) a locally restricted, not a universal, permission to venerate, which is (2) a mere permission, and no precept; while canonization implies a universal precept" (Beccari, Camillo. "Beatification and Canonization". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. Accessed 27 May 2009.).

- ^ August., Brevic. Collat. cum Donatistis, III, 13, no. 25 in PL, XLIII, 628.

- ^ Gonzalez Tellez, Comm. Perpet. in singulos textus libr. Decr., III, xlv, in Cap. 1, De reliquiis et vener. Sanct.

- ^ Kemp, E. W. (1945). "Pope Alexander III and the Canonization of Saints: The Alexander Prize Essay". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 27: 13–28. doi:10.2307/3678572. ISSN 0080-4401. JSTOR 3678572. S2CID 159681002.

- ^ a b "William Smith and Samuel Cheetham, A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities (Murray, 1875)". Boston: Little. p. 283. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "Pope Alexander III". Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Pope Gregory IX, Decretales, 3, "De reliquiis et veneratione sanctorum". It is alternatively quoted as follows: "For the future you will not presume to pay him reverence, as, even though miracles were worked through him, it would not allow you to revere him as a saint unless with the authority of the Roman Church". (C. 1, tit. cit., X, III, xlv.)

- ^ St. Robert Bellarmine, De Eccles. Triumph., I, 8.

- ^ "Aimable Musoni, 'Saints without Borders'" (PDF). pp. 9–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Divinus Perfectionis Magister". The Holy See. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ "Devil's Advocate Is Puglia: 'It will test the virtues of aspiring saints', la Republica". 5 November 2012.

- ^ Pope John Paul II, Divinus Perfectionis Magister (25 January 1983), Art. 1, Sec. 1.

- ^ Pietro Cardinal Palazzini, Norms to be observed in inquiries made by bishops in the causes of saints, 1983 Archived 22 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine, §9(a).

- ^ Mother Teresa of Calcutta (1910–1997), Biography, Office of Papal Liturgical Celebrations, Internet Office of the Holy See

- ^ "Sister Lucia's Beatification Process to Begin". ZENIT – The World Seen from Rome. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Cardinal José Saraiva Martins, CMF, Response of His Holiness Benedict XVI for the Examination of the Cause for Beatification and Canonization of the Servant of God John Paul II, 2005 Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Doctrinal Commentary on the Concluding Formula of the Professio Fidei, by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

- ^ "Beatification and Canonization", The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. p. 366.

- ^ "Making Saints: The Process of Canonization in the Catholic Church". The Maronite Voice. 3 January 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

Having ascertained the martyrdom or heroic practice of the virtues or "heroic offer of life" through beatification, the Church officially raises one to the honors of the altar, but the cult given to him or her will be restricted to a Church sui iuris, a nation, region, diocese, province or a religious institute according the stipulations in the decree of beatification. Canonization removes this restraint and the saint becomes an object of veneration in the universal Church.

- ^ a b EWTN. "Pope Francis declares blind 14th-century lay Dominican a saint". CNA. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Beatification and Canonization". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2000. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

Those proposed as coming under the definition of cases excepted (casus excepti) by Urban VIII are treated in another way. In such cases it must be proved that an immemorial public veneration (at least for 100 years before the promulgation, in 1640, of the decrees of Urban VIII) has been paid the servant of God, whether confessor or martyr. Such cause is proposed under the title of "confirmation of veneration" (de confirmatione cultus); it is dealt with in an ordinary meeting of the Congregation of Rites.

- ^ Mitchell, Jolyon (29 November 2012). Martyrdom: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780191642449.

In 1660 the convocations of Canterbury and York canonized King Charles.

- ^ Hodges, Sam (2008). "Dietrich Bonhoeffer first martyr officially recognized by United Methodists". Dallas News. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Mulenga, Maidstone (1 May 2012). "United Methodists declare MLK Jr. a modern-day martyr". United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Αγ. Χρυσόστομος Σμύρνης. Archived 21 July 2011 at archive.today. Municipality of Triglia. Retrieved: 7 September 2012.

- ^ (in Greek) Κων/τίνος Β. Χιώλος. "Ο μαρτυρικός θάνατος του Μητροπολίτου Σμύρνης". Archived 12 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Δημοσια Κεντρικη Βιβλιοθηκη Σερρων. Τετάρτη, 13 Σεπτεμβρίου 2006.

- ^ "Почему был канонизирован Николай Второй?" by Protodeacon Andrey Kuraev at Pravmir.ru (17 July 2009)

- ^ ""Прославление святых – это не дело узкого круга специалистов, это дело всей Церкви" by Julija Birjukova at Pravmir.ru (9 Dec. 2013)".

- ^ "On the Glorification of Saints" by Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky

- ^ Georgios Babiniotis. Dictionary of Modern Greek, Athens: Lexicology Centre, 1998, p. 53.

- ^ "The Glorification of Saints in the Orthodox Church" Archived 8 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Fr. Joseph Frawley

- ^ Roberta R. Ervine, Worship Traditions in Armenia and the Neighboring Christian East, St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2006, p. 346 n. 17.

- ^ Davlashyan, Naira. "Armenian Church makes saints of 1.5 million genocide victims". Yahoo News. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Armenian Genocide victims canonized in Holy Etchmiadzin". Panarmenian.Net. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ "Canonized: Armenian Church proclaims collective martyrdom of Genocide victims – Genocide". ArmeniaNow.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

References

[edit]- Kemp, Eric Waldram (1948), Canonization and Authority in the Western Church, Oxford: Oxford University Press

External links

[edit] Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Canonization", Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 5 (9th ed.), 1878, pp. 22–23

- Delehaye, Hippolyte (1911), "Canonization", Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 5 (11th ed.), pp. 192–193

- Beccari, Camillo (1907). "Beatification and Canonization". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2.

Catholic Church

[edit]- Divinus Perfectionis Magister – Apostolic Constitution of Pope John Paul II (English)

- Congregation for the Causes of Saints – Vatican Website

- Historical Sketch of Canonization – Friarsminor.org