Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Luna 9

View on Wikipedia

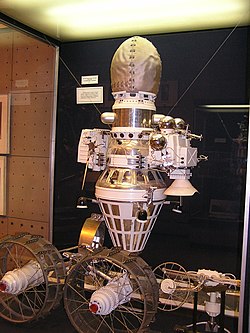

A replica of Luna 9 on display in the Museum of Air and Space Paris, Le Bourget. | |

| Mission type | Lunar lander |

|---|---|

| Operator | Soviet space program |

| COSPAR ID | 1966-006A |

| SATCAT no. | 01954 |

| Mission duration | 6 days, 11 hours, 10 minutes |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft type | Ye-6 |

| Manufacturer | GSMZ Lavochkin |

| Launch mass | 1583.7 kg[1] |

| Landing mass | 99 kg |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 31 January 1966, 11:41:37 UTC[1] |

| Rocket | Molniya-M 8K78M s/n 103-32 |

| Launch site | Baikonur, Site 31/6 |

| End of mission | |

| Last contact | 6 February 1966, 22:55 GMT |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric[2] |

| Regime | Highly elliptical |

| Perigee altitude | 220 km |

| Apogee altitude | 500000 km |

| Inclination | 51.8° |

| Period | 14.96 days |

| Epoch | 31 January 1966 |

| Lunar lander | |

| Landing date | 3 February 1966, 18:45:30 GMT |

| Landing site | 7°08′N 64°22′W / 7.13°N 64.37°W[3][4][5] |

Luna 9 (Луна-9), internal designation Ye-6 No.13, was an uncrewed space mission of the Soviet Union's Luna programme. On 3 February 1966, the Luna 9 spacecraft became the first spacecraft to achieve a soft landing on the Moon and return imagery from its surface.[6][7]

Spacecraft

[edit]The spacecraft and lander capsule, combined, weighed 1,538 kilograms (3,391 lb) and was 2.7 meters tall. It commenced the main descent, and shortly before its controlled impact ejected the lander capsule. The lander had a mass of 99 kilograms (218 lb) and consisted of a spheroid Automatic Lunar Station (ALS) capsule measuring 58 centimetres (23 in).[6] It used a landing bag to survive the impact speed of over 54 kilometres per hour (34 mph).[8] It was a hermetically sealed container with radio equipment, a program timing device, heat control systems, scientific apparatus, power sources, and a television system.

The spacecraft was developed in the design bureau then known as OKB-1, under Chief Designer Sergei Korolev (who had died before the launch). The first 11 Luna missions were unsuccessful for a variety of reasons. At that time the project was transferred to Lavochkin design bureau since OKB-1 was busy with a human expedition to the Moon. Luna 9 was the twelfth attempt at a soft-landing by the Soviet Union; it was also the first successful deep space probe built by the Lavochkin design bureau, which ultimately would design and build almost all Soviet (later Russian) lunar and interplanetary spacecraft.[9]

Launch and translunar coast

[edit]Luna 9 was launched by a Molniya-M rocket, serial number 103-32, flying from Site 31/6 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. Liftoff took place at 11:41:37 GMT on 31 January 1966. The first three stages of the four-stage carrier rocket injected the payload and fourth stage into low Earth orbit, at an altitude of 168 by 219 kilometres (104 by 136 mi) and an inclination of 51.8°.[2] The fourth stage, a Blok-L, then fired to raise the perigee of the orbit to a new apogee approximately 500,000 kilometres (310,000 mi), before deploying Luna 9 into a highly elliptical geocentric orbit.[2]

For thermal control, the spacecraft then spun itself up to 0.67 rpm using nitrogen jets. On 1 February at 19:29 GMT, a mid-course correction took place involving a 48-second burn and resulting in a delta-v of 71.2 metres per second (234 ft/s).[6]

Descent and landing

[edit]Oblique LO3 view of Planitia Descensus

| |||||||

At an altitude of 8,300 kilometres (5,200 mi) from the Moon, the spacecraft was oriented for the firing of its retrorockets and its spin was stopped in preparation for landing. From this moment the orientation of the spacecraft was supported by measurements of directions to the Sun and the Earth using an optomechanical system. At 75 kilometres (47 mi) above the lunar surface, the radar altimeter triggered the jettison of the side modules, the inflation of the airbags and the firing of the retro rockets. At 250 metres (820 ft) from the surface, the main retrorocket was turned off by the integrator of an acceleration having reached the planned velocity of the braking manoeuver. The four outrigger engines were used to slow the craft. About 5 metres (16 ft) above the lunar surface, a contact sensor touched the ground triggering the engines to be shut down and the landing capsule to be ejected and its landing airbag being inflated. The capsule landed at 22 kilometres per hour (14 mph; 6.1 m/s).[6]

The capsule bounced several times before coming to rest in Oceanus Procellarum west of Reiner and Marius craters at approximately 7°8′N 64°22′W / 7.133°N 64.367°W[3][10] on 3 February 1966 at 18:45:30 GMT.[6]

Surface operations

[edit]

Approximately 250 seconds after landing in the Oceanus Procellarum, four petals that covered the top half of the spacecraft opened outward for increased stability. Seven hours after (to allow for the Sun to climb to 7° elevation) the probe began sending the first of nine images (including five panoramas) of the surface of the Moon. Seven radio sessions with a total of 8 hours and 5 minutes were transmitted, as well as a series of three TV pictures. After assembly the photographs gave a panoramic view of the immediate lunar surface, comprising views of nearby rocks and of the horizon, 1.4 kilometres (0.87 mi) away.[6]

The pictures from Luna 9 were not released immediately by the Soviet authorities, but scientists at Jodrell Bank Observatory in England, which was monitoring the craft, noticed that the signal format used was identical to the internationally agreed Radiofax system used by newspapers for transmitting pictures. The Daily Express rushed a suitable receiver to the Observatory and the pictures from Luna 9 were decoded and published worldwide.[11] The BBC speculated that the spacecraft's designers deliberately fitted the probe with equipment conforming to the standard, to enable reception of the pictures by Jodrell Bank Observatory.[12]

The radiation detector, the only dedicated scientific instrument on board, measured dosage of 30 millirads (0.3 milligrays) per day.[13] The mission also determined that a spacecraft would not sink into the lunar dust; that the ground could support a lander. The last contact with the spacecraft was at 22:55 GMT on 6 February 1966.[6]

Models and displays

[edit]Detailed Luna 9 models are on display at the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics, Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics, Museum of Cosmonautics and Rocket Technology, Museum of Air and Space Paris and other locations.

-

Luna 9 mockup (1:1) at the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics.

-

Luna-9 descent capsule at the Memorial Museum of Cosmonautics.

-

Luna 9 on display at the Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics.

-

Luna-9 descent capsule at the Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics.

-

Onboard container of the automatic control system "Luna-9", Museum of the History of Cosmonautics.

-

Luna 9 model at the Museum of Cosmonautics and Rocket Technology.

Stamps

[edit]The successful Luna 9 landing was commemorated on stamps.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]Sources

[edit]- ^ a b Siddiqi 2018, p. 55.

- ^ a b c McDowell, Jonathan. "Satellite Catalog". Jonathan's Space Page. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ a b Table of Anthropogenic Impacts and Spacecraft on the Moon.

- ^ Wagner, R.V.; Nelson, D.M.; Plescia, J.B.; Robinson, M.S.; Speyerer, E.J.; Mazarico, E. (2017). "Coordinates of anthropogenic features on the Moon". Icarus. 283: 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2016.05.011.

- ^ Siddiqi et al. 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f g "NASA-NSSDC-Spacecraft-Details". NASA. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Reichl, Eugen (2019). The Soviet Space Program The Lunar Years: 1959-1976. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-7643-5675-9. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Luna E-6". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, D.C.: NASA History Program Office. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2019.

- ^ Siddiqi, A.; Hendrickx, B.; Varfolomeyev, T. (2000). "The Tough Road Travelled - A New Look at the Second Generation Luna Probes". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 53 (9–10): 343. ISSN 0007-084X.

- ^ Daily Express front page Saturday February 5 1966

- ^ BBC On This Day | 3 | 1966: Soviets land probe on Moon

- ^ NSSDCA ID: 1966-006A-02