Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Soviet space program

View on Wikipedia

| Russian: Космическая программа СССР, romanized: Kosmicheskaya programma SSSR | |

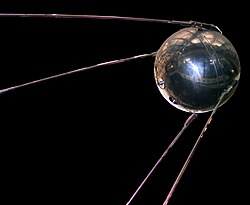

Launch of the first successful artificial satellite, Sputnik-1, from R-7 platform in 1957 | |

| Formed | 1951 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | December 1, 1991[1][2] |

| Manager |

|

| Key people | Design Bureaus |

| Primary spaceport | |

| First flight | Sputnik 1 (October 4, 1957) |

| First crewed flight | Vostok 1 (April 12, 1961) |

| Last crewed flight | Soyuz TM-13 (October 2, 1991) |

| Successes | See accomplishments |

| Failures | See failures below |

| Partial failures | See partial or cancelled projects Soviet lunar program |

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| Soviet space program |

|---|

The Soviet space program[3] (Russian: Космическая программа СССР, romanized: Kosmicheskaya programma SSSR) was the state space program of the Soviet Union, active from 1951 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.[4][5][6] Contrary to its competitors (NASA in the United States, the European Space Agency in Western Europe, and the Ministry of Aerospace Industry in China), which had their programs run under single coordinating agencies, the Soviet space program was divided between several internally competing design bureaus led by Korolev, Kerimov, Keldysh, Yangel, Glushko, Chelomey, Makeyev, Chertok and Reshetnev.[7] Several of these bureaus were subordinated to the Ministry of General Machine-Building. The Soviet space program served as an important marker of claims by the Soviet Union to its superpower status.[8]: 1

Soviet investigations into rocketry began with the formation of the Gas Dynamics Laboratory in 1921, and these endeavors expanded during the 1930s and 1940s.[9][10] In the years following World War II, both the Soviet and United States space programs utilised German technology in their early efforts at space programs. In the 1950s, the Soviet program was formalized under the management of Sergei Korolev, who led the program based on unique concepts derived from Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, sometimes known as the father of theoretical astronautics.[11]

Competing in the Space Race with the United States and later with the European Union and with China, the Soviet space program was notable in setting many records in space exploration, including the first intercontinental missile (R-7 Semyorka) that launched the first satellite (Sputnik 1) and sent the first animal (Laika the dog) into Earth orbit in 1957, and placed the first human in space in 1961, Yuri Gagarin. In addition, the Soviet program also saw the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, in 1963 and the first spacewalk in 1965. Other milestones included computerized robotic missions exploring the Moon starting in 1959: being the first to reach the surface of the Moon, recording the first image of the far side of the Moon, and achieving the first soft landing on the Moon. The Soviet program also achieved the first space rover deployment with the Lunokhod programme in 1966, and sent the first robotic probe that automatically extracted a sample of lunar soil and brought it to Earth in 1970, Luna 16.[12][13] The Soviet program was also responsible for leading the first interplanetary probes to Venus and Mars and made successful soft landings on these planets in the 1960s and 1970s.[14] It put the first space station, Salyut 1, into low Earth orbit in 1971, and the first modular space station, Mir, in 1986.[15] Its Interkosmos program was also notable for sending the first citizen of a country other than the United States or Soviet Union into space.[16][17]

The primary spaceport, Baikonur Cosmodrome, is now in Kazakhstan, which leases the facility to Russia.[18][19]

Origins

[edit]Early Russian-Soviet efforts

[edit]

The theory of space exploration had a solid basis in the Russian Empire before the First World War with the writings of the Russian and Soviet rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857–1935), who published pioneering papers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries on astronautic theory, including calculating the Rocket equation and in 1929 introduced the concept of the multistaged rocket.[20][21][22] Additional astronautic and spaceflight theory was also provided by the Ukrainian and Soviet engineer and mathematician Yuri Kondratyuk who developed the first known lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR), a key concept for landing and return spaceflight from Earth to the Moon.[23][24] The LOR was later used for the plotting of the first actual human spaceflight to the Moon. Many other aspects of spaceflight and space exploration are covered in his works.[25] Both theoretical and practical aspects of spaceflight was also provided by the Latvian pioneer of rocketry and spaceflight Friedrich Zander,[26] including suggesting in a 1925 paper that a spacecraft traveling between two planets could be accelerated at the beginning of its trajectory and decelerated at the end of its trajectory by using the gravity of the two planets' moons – a method known as gravity assist.[27]

Gas Dynamics Laboratory (GDL)

[edit]The first Soviet development of rockets was in 1921, when the Soviet military sanctioned the commencement of a small research laboratory to explore solid fuel rockets, led by Nikolai Tikhomirov, a chemical engineer, and supported by Vladimir Artemyev, a Soviet engineer.[28][29] Tikhomirov had commenced studying solid and Liquid-fueled rockets in 1894, and in 1915, he lodged a patent for "self-propelled aerial and water-surface mines."[30] In 1928 the laboratory was renamed the Gas Dynamics Laboratory (GDL).[31] The First test-firing of a solid fuel rocket was carried out in March 1928, which flew for about 1,300 meters[30] Further developments in the early 1930s were led by Georgy Langemak.[32] and 1932 in-air test firings of RS-82 unguided rockets from an Tupolev I-4 aircraft armed with six launchers successfully took place.[33]

Sergey Korolev

[edit]A key contributor to early soviet efforts came from a young Russian aircraft engineer Sergey Korolev, who would later become the de facto head of the Soviet space programme.[34] In 1926, as an advanced student, Korolev was mentored by the famous Soviet aircraft designer Andrey Tupolev, who was a professor at his University.[35] In 1930, while working as a lead engineer on the Tupolev TB-3 heavy bomber he became interested in the possibilities of liquid-fueled rocket engines to propel airplanes. This led to contact with Zander, and sparked his interest in space exploration and rocketry.[34]

Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (GIRD)

[edit]

Practical aspects built on early experiments carried out by members of the 'Group for the Study of Reactive Motion' (better known by its Russian acronym "GIRD") in the 1930s, where Zander, Korolev and other pioneers such as the Russian engineers Mikhail Tikhonravov, Leonid Dushkin, Vladimir Vetchinkin and Yuriy Pobedonostsev worked together.[36][37][38] On August 18, 1933, the Leningrad branch of GIRD, led by Tikhonravov,[37] launched the first hybrid propellant rocket, the GIRD-09,[39] and on November 25, 1933, the Soviet's first liquid-fueled rocket GIRD-X.[40]

Reactive Scientific Research Institute (RNII)

[edit]In 1933 GIRD was merged with GDL[30] by the Soviet government to form the Reactive Scientific Research Institute (RNII),[37] which brought together the best of the Soviet rocket talent, including Korolev, Langemak, Ivan Kleymyonov and former GDL engine designer Valentin Glushko.[41][42] Early success of RNII included the conception in 1936 and first flight in 1941 of the RP-318 the Soviets first rocket-powered aircraft and the RS-82 and RS-132 missiles entered service by 1937,[43] which became the basis for development in 1938 and serial production from 1940 to 1941 of the Katyusha multiple rocket launcher, another advance in the reactive propulsion field.[44][45][46] RNII's research and development were very important for later achievements of the Soviet rocket and space programs.[46][29]

During the 1930s, Soviet rocket technology was comparable to Germany's,[47] but Joseph Stalin's Great Purge severely damaged its progress. In November 1937, Kleymyonov and Langemak were arrested and later executed, Glushko and many other leading engineers were imprisoned in the Gulag.[48] Korolev was arrested in June 1938 and sent to a forced labour camp in Kolyma in June 1939. However, due to intervention by Tupolev, he was relocated to a prison for scientists and engineers in September 1940.[49]

World War II

[edit]During World War II, rocketry efforts were carried out by three Soviet design bureaus.[50] RNII continued to develop and improve solid fuel rockets, including the RS-82 and RS-132 missiles and the Katyusha rocket launcher,[32] where Pobedonostsev and Tikhonravov continued to work on rocket design.[51][52] In 1944, RNII was renamed Scientific Research Institute No 1 (NII-I) and combined with design bureau OKB-293, led by Soviet engineer Viktor Bolkhovitinov, which developed, with Aleksei Isaev, Boris Chertok, Leonid Voskresensky and Nikolay Pilyugin a short-range rocket powered interceptor called Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1.[53]

Special Design Bureau for Special Engines (OKB-SD) was led by Glushko and focused on developing auxiliary liquid-fueled rocket engines to assist takeoff and climbing of prop aircraft, including the RD-IKhZ, RD-2 and RD-3.[54] In 1944, the RD-1 kHz auxiliary rocket motor was tested in a fast-climb Lavochkin La-7R for protection of the capital from high-altitude Luftwaffe attacks.[55] In 1942 Korolev was transferred to OKB-SD, where he proposed development of the long range missiles D-1 and D-2.[56]

The third design bureau was Plant No 51 (OKB-51), led by Soviet Ukrainian Engineer Vladimir Chelomey, where he created the first Soviet pulsating air jet engine in 1942, independently of similar contemporary developments in Nazi Germany.[57][58]

German influence

[edit]Nazi Germany developed rocket technology that was more advanced than the Allies and a race commenced between the Soviet Union and the United States to capture and exploit the technology. Soviet rocket specialist was sent to Germany in 1945 to obtain V-2 rockets and worked with German specialists in Germany and later in the Soviet Union to understand and replicate the rocket technology.[59][60][61] The involvement of German scientists and engineers was an essential catalyst to early Soviet efforts. In 1945 and 1946 the use of German expertise was invaluable in reducing the time needed to master the intricacies of the V-2 rocket, establishing production of the R-1 rocket and enable a base for further developments. On 22 October 1946, 302 German rocket scientists and engineers, including 198 from the Zentralwerke (a total of 495 persons including family members), were deported to the Soviet Union as part of Operation Osoaviakhim.[62][63][64] However, after 1947 the Soviets made very little use of German specialists and their influence on the future Soviet rocket program was marginal.[65]

Sputnik and Vostok

[edit]

The Soviet space program was tied to the USSR's Five-Year Plans and from the start was reliant on support from the Soviet military. Although he was "single-mindedly driven by the dream of space travel", Korolev generally kept this a secret while working on military projects—especially, after the Soviet Union's first atomic bomb test in 1949, a missile capable of carrying a nuclear warhead to the United States—as many mocked the idea of launching satellites and crewed spacecraft. Nonetheless, the first Soviet rocket with animals aboard launched in July 1951; the two dogs, Dezik and Tsygan, were recovered alive after reaching 101 km in altitude. Two months ahead of America's first such achievement, this and subsequent flights gave the Soviets valuable experience with space medicine.[66]: 84–88, 95–96, 118

Because of its global range and large payload of approximately five tons, the reliable R-7 was not only effective as a strategic delivery system for nuclear warheads, but also as an excellent basis for a space vehicle. The United States' announcement in July 1955 of its plan to launch a satellite during the International Geophysical Year greatly benefited Korolev in persuading Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to support his plans. [66]: 148–151 In a letter addressed to Khrushchev, Korolev stressed the necessity of launching a "simple satellite" in order to compete with the American space effort.[67] Plans were approved for Earth-orbiting satellites (Sputnik) to gain knowledge of space, and four uncrewed military reconnaissance satellites, Zenit. Further planned developments called for a crewed Earth orbit flight by and an uncrewed lunar mission at an earlier date.[68]

After the first Sputnik proved to be successful, Korolev—then known publicly only as the anonymous "Chief Designer of Rocket-Space Systems"[66]: 168–169 —was charged to accelerate the crewed program, the design of which was combined with the Zenit program to produce the Vostok spacecraft. After Sputnik, Soviet scientists and program leaders envisioned establishing a crewed station to study the effects of zero-gravity and the long term effects on lifeforms in a space environment.[69] Still influenced by Tsiolkovsky—who had chosen Mars as the most important goal for space travel—in the early 1960s, the Soviet program under Korolev created substantial plans for crewed trips to Mars as early as 1968 to 1970. With closed-loop life support systems and electrical rocket engines, and launched from large orbiting space stations, these plans were much more ambitious than America's goal of landing on the Moon.[66]: 333–337

In late 1963 and early 1964 the Polyot 1 and Polyot 2 satellites were launched, these were the first satellites capable of adjusting both orbital inclination and Apsis. This marked a significant step in the potential use of spacecraft in Anti-satellite warfare, as it demonstrated the potential to eventually for uncrewed satellites to intercept and destroy other satellites. This would have highlighted the potential use of the space program in a conflict with the US.[70][71][72]

Funding and support

[edit]

The Soviet space program was secondary in military funding to the Strategic Rocket Forces' ICBMs. While the West believed that Khrushchev personally ordered each new space mission for propaganda purposes, and the Soviet leader did have an unusually close relationship with Korolev and other chief designers, Khrushchev emphasized missiles rather than space exploration and was not very interested in competing with Apollo.[66]: 351, 408, 426–427

While the government and the Communist Party used the program's successes as propaganda tools after they occurred, systematic plans for missions based on political reasons were rare, one exception being Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, on Vostok 6 in 1963.[66]: 351 Missions were planned based on rocket availability or ad hoc reasons, rather than scientific purposes. For example, the government in February 1962 abruptly ordered an ambitious mission involving two Vostoks simultaneously in orbit launched "in ten days time" to eclipse John Glenn's Mercury-Atlas 6 that month; the program could not do so until August, with Vostok 3 and Vostok 4.[66]: 354–361

Internal competition

[edit]Unlike the American space program, which had NASA as a single coordinating structure directed by its administrator, James Webb through most of the 1960s, the USSR's program was split between several competing design groups. Despite the successes of the Sputnik Program between 1957 and 1961 and Vostok Program between 1961 and 1964, after 1958 Korolev's OKB-1 design bureau faced increasing competition from his rival chief designers, Mikhail Yangel, Valentin Glushko, and Vladimir Chelomei. Korolev planned to move forward with the Soyuz craft and N-1 heavy booster that would be the basis of a permanent crewed space station and crewed exploration of the Moon. However, Dmitry Ustinov directed him to focus on near-Earth missions using the Voskhod spacecraft, a modified Vostok, as well as on uncrewed missions to nearby planets Venus and Mars.[citation needed]

Yangel had been Korolev's assistant but with the support of the military, he was given his own design bureau in 1954 to work primarily on the military space program. This had the stronger rocket engine design team including the use of hypergolic fuels but following the Nedelin catastrophe in 1960 Yangel was directed to concentrate on ICBM development. He also continued to develop his own heavy booster designs similar to Korolev's N-1 both for military applications and for cargo flights into space to build future space stations.[citation needed]

Glushko was the chief rocket engine designer but he had a personal friction with Korolev and refused to develop the large single chamber cryogenic engines that Korolev needed to build heavy boosters.[citation needed]

Chelomey benefited from the patronage of Khrushchev[66]: 418 and in 1960 was given the plum job of developing a rocket to send a crewed vehicle around the Moon and a crewed military space station. With limited space experience, his development was slow.[citation needed]

The progress of the Apollo program alarmed the chief designers, who each advocated for his own program as the response. Multiple, overlapping designs received approval, and new proposals threatened already approved projects. Due to Korolev's "singular persistence", in August 1964—more than three years after the United States declared its intentions—the Soviet Union finally decided to compete for the Moon. It set the goal of a lunar landing in 1967—the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution—or 1968.[66]: 406–408, 420 At one stage in the early 1960s the Soviet space program was actively developing multiple launchers and spacecraft. With the fall of Krushchev in 1964, Korolev was given complete control of the crewed program.[73][74]

In 1961, Valentin Bondarenko, a cosmonaut training for a crewed Vostok mission, was killed in an endurance experiment after the chamber he was in caught on fire. The Soviet Union chose to cover up his death and continue on with the space program.[75]

After Korolev

[edit]

Korolev died in January 1966 from complications of heart disease and severe hemorrhaging following a routine operation that uncovered colon cancer. Kerim Kerimov,[76] who had previously served as the head of the Strategic Rocket Forces and had participated in the State Commission for Vostok as part of his duties,[77] was appointed Chairman of the State Commission on Piloted Flights and headed it for the next 25 years (1966–1991). He supervised every stage of development and operation of both crewed space complexes as well as uncrewed interplanetary stations for the former Soviet Union. One of Kerimov's greatest achievements was the launch of Mir in 1986.[citation needed]

The leadership of the OKB-1 design bureau was given to Vasily Mishin, who had the task of sending a human around the Moon in 1967 and landing a human on it in 1968. Mishin lacked Korolev's political authority and still faced competition from other chief designers.[citation needed] Under pressure, Mishin approved the launch of the Soyuz 1 flight in 1967, even though the craft had never been successfully tested on an uncrewed flight. The mission launched with known design problems and ended with the vehicle crashing to the ground, killing Vladimir Komarov. This was the first in-flight fatality of any space program.[78]

The Soviets were beaten in sending the first crewed flight around the Moon in 1968 by Apollo 8, but Mishin pressed ahead with development of the flawed super heavy N1, in the hope that the Americans would have a setback, leaving enough time to make the N1 workable and land a man on the Moon first. There was a success with the joint flight of Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5 in January 1969 that tested the rendezvous, docking, and crew transfer techniques that would be used for the landing, and the LK lander was tested successfully in earth orbit. But after four uncrewed test launches of the N1 ended in failure, the program was suspended for two years and then cancelled, removing any chance of the Soviets landing men on the Moon before the United States.[79]

Besides the crewed landings, the abandoned Soviet Moon program included the multipurpose moon base Zvezda, first detailed with developed mockups of expedition vehicles[80] and surface modules.[81]

Following this setback, Chelomey convinced Ustinov to approve a program in 1970 to advance his Almaz military space station as a means of beating the US's announced Skylab. Mishin remained in control of the project that became Salyut but the decision backed by Mishin to fly a three-man crew without pressure suits rather than a two-man crew with suits to Salyut 1 in 1971 proved fatal when the re-entry capsule depressurized killing the crew on their return to Earth. Mishin was removed from many projects, with Chelomey regaining control of Salyut. After working with NASA on the Apollo–Soyuz, the Soviet leadership decided a new management approach was needed, and in 1974 the N1 was canceled and Mishin was out of office. The design bureau was renamed NPO Energia with Glushko as chief designer.[79]

In contrast with the difficulty faced in its early crewed lunar programs, the USSR found significant success with its remote moon operations, achieving two historical firsts with the automatic Lunokhod and the Luna sample return missions. The Mars probe program was also continued with some success, while the explorations of Venus and then of the Halley comet by the Venera and Vega probe programs were more effective.[79]

Lunar missions

[edit]

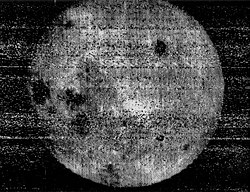

The "Luna" programme, achieved the first flyby of the moon by Luna 1 in 1959 (also marking the first time a probe reached the far side of the moon),[82] the first impact of the moon by Luna 2,[83] and the first photos of the far side of the moon by Luna 3.

As well as garnering scientific information on the moon, Luna 1 was able to detect a strong flow of ionized plasma emanating from the Sun, streaming through interplanetary space. Luna 2 impacted the moon east of Mare Imbrium.[83] Photography transmitted by Luna 3 showed two dark regions which were named Mare Moscoviense (Sea of Moscow) and Mare Desiderii (Sea of Dreams), the latter was found to be composed of the smaller Mare Ingenii and other dark craters.[84] Luna 2 marked the first time a man-made object has contacted a celestial body. Luna 1 discovered the Moon had no magnetic field.[82]

In 1963, the Soviet Union's "2nd Generation" Luna programme was less successful, Luna 4, Luna 5, Luna 6, Luna 7, and Luna 8 were all met with mission failures. However, in 1966 Luna 9 achieved the first soft-landing on the Moon, and successfully transmitted photography from the surface.[85] Luna 10 marked the first man-made object to establish an orbit around the Moon,[86] followed by Luna 11, Luna 12, and Luna 14 which also successfully established orbits. Luna 12 was able to transmit detailed photography of the surface from orbit.[87] Luna 10, 12, and Luna 14 conducted Gamma ray spectrometry of the Moon, among other tests.

The Zond programme was orchestrated alongside the Luna programme with Zond 1 and Zond 2 launching in 1964, intended as flyby missions, however both failed.[88][89] Zond 3 however was successful, and transmitted high quality photography from the far side of the moon.[90][91]

In late 1966, Luna 13 became the third spacecraft to make a soft-landing on the Moon, with the American Surveyor 1 having now taken second.[92]

Zond 4, launched in 1968 was intended as a means to test the possibility of a crewed mission to the moon, including methods of a stable re-entry to earth from a Lunar trajectory using a heat shield.[93] It did not flyby the moon, but established an elliptical orbit at Lunar distance. Due to issues with the crafts orientation, it was unable to make a soft-landing in the Soviet union and instead was self destructed. Later in the year Zond 5, carrying two Russian tortoises became the first man-made object to flyby the moon and return to Earth (as well as the first animal to flyby the moon), splashing down in the Indian Ocean.[94] Zond 6, Zond 7, and Zond 8 had similar mission profiles, Zond 6 failed to return to earth safely, Zond 7 did however and returned high quality color photography of the earth and the moon from varying distances,[95] Zond 8 successfully returned to earth after a Lunar flyby.[96]

In 1969, Luna 15 was an intended lunar sample return mission, however resulted in a crash landing.[97] In 1970 however Luna 16 became the first robotic probe to land on the Moon and return a surface sample, having drilled 35 cm into the surface,[98] to Earth and represented the first lunar sample return mission by the Soviet Union and the third overall, having followed the Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 crewed missions.

Luna 17, Luna 21 and Luna 24 delivered rovers onto the surface of the moon.[99] Luna 20 was another successful sample return mission.[100] Luna 18 and Luna 23 resulted in crash landings.

In total there were 24 missions in the Luna Programme, 15 were considered to be successful, including 4 hard landings and 3 soft landings, 6 orbits, and 2 flybys. The programme was continued after the collapse of the Soviet union, when the Russian federation space agency launched Luna 25 in 2023.[101]

Venusian missions

[edit]

The Venera programme marked many firsts in space exploration and explorations of Venus. Venera 1 and Venera 2 resulted in failure due to losses of contact, Venera 3, which also lost contact, marked the first time a man-made object made contact with another planet after it impacted Venus on March 1, 1966. Venera 4, Venera 5, and Venera 6 performed successful atmospheric entry. In 1970 Venera 7 marked the first time a spacecraft was able to return data after landing on another planet.[102]

Venera 7 held a resistant thermometer and an aneroid barometer to measure the temperature and atmospheric pressure on the surface, the transmitted data showed 475 C at the surface, and a pressure of 92 bar. A wind of 2.5 meters/sec was extrapolated from other measurements. The landing point of Venera 7 was 5°S 9°W / 5°S 9°W.[103][104] Venera 7 impacted the surface at a somewhat high speed of 17 metres per second, later analysis of the recorded radio signals revealed that the probe had survived the impact and continued transmitting a weak signal for another 23 minutes. It is believed that the spacecraft may have bounced upon impact and come to rest on its side, so the antenna was not pointed towards Earth.[102][105]

In 1972, Venera 8 landed on Venus and measured the light level as being suitable for surface photography, finding it to be similar to the amount of light on Earth on an overcast day with roughly 1 km visibility.[106]

In 1975, Venera 9 established an orbit around Venus and successfully returned the first photography of the surface of Venus.[107][108] Venera 10 landed on Venus and followed with further photography shortly after.[109]

In 1978, Venera 11 and Venera 12 successfully landed, however ran into issues performing photography and soil analysis. Venera 11's light sensor detected lightning strikes.[110][111][112]

In 1981, Venera 13 performed a successful soft-landing on Venus and marked the first probe to drill into the surface of another planet and take a sample.[113][114] Venera 13 also took an audio sample of the Venusian environment, marking another first.[115]

Venera 13 returned the first color images of the surface of Venus, revealing an orange-brown flat bedrock surface covered with loose regolith and small flat thin angular rocks. The composition of the sample determined by the X-ray fluorescence spectrometer put it in the class of weakly differentiated melanocratic alkaline gabbroids, similar to terrestrial leucitic basalt with a high potassium content. The acoustic detector returned the sounds of the spacecraft operations and the background wind, estimated to be a speed of around 0.5 m/sec wind.[113]

Venera 14, an identical spacecraft to Venera 13, launched 5 days apart. The mission profiles were very similar, except 14 ran into issues using it's spectrometer to analyze the soil.[116]

In total 10 Venera probes achieved a soft landing on the surface of Venus.

In 1984, the Vega programme began and ended with the launch of two crafts launched 6 days apart, Vega 1 and Vega 2. Both crafts deployed a balloon in addition to a lander, marking a first in spaceflight.[117][118][119]

Martian missions

[edit]

The first Soviet mission to explore Mars, Mars 1, was launched in 1962. Although it was intended to fly by the planet and transmit scientific data, the spacecraft lost contact before reaching Mars, marking a setback for the program. In 1971, the Soviet Union launched Mars 2 and Mars 3. Mars 2 became the first spacecraft to reach the surface of mars, however this was a hard landing and was destroyed on impact.[120][121] However, Mars 3 achieved a historic milestone by becoming the first successful soft landing on Mars. Mars 3 used parachutes and rockets as part of its landing system, however contacted the surface at a somewhat high speed of 20 metres per second. Unfortunately, its lander transmitted data for only up to 20 seconds before it went silent.[122]

Following the initial successes and setbacks, the Mars 4, Mars 5, Mars 6, and Mars 7 missions were launched between 1969 and 1973. Mars 4 and Mars 5 performed successful flybys, performing analysis which detected the presence of a weak Ozone layer and magnetic field corroborating analysis done by the American Mariner 4 and Mariner 9.[123] Mars 6 and Mars 7 failed to successfully land.[124]

Salyut space station

[edit]

The Salyut programme was a series of missions which established the first earth orbit Space station.[125] "Salyut" meaning "Salute" translated.

Initially, the Salyut stations served as research laboratories in orbit. Salyut 1, the first in the series, launched in 1971, was primarily a civilian scientific mission. The crew set a then record-setting 24-day mission though its tragic end due to the death of the Soyuz-11 crew after a docking accident underscored the high risks of human spaceflight.[126] Following this, the Soviet Union also developed Salyut 2 and Salyut 3, which featured reconnaissance capabilities and carried a large gun,[125][127] both ran into significant issues during their missions.[128][129] This dual use design of both scientific and military research applications demonstrated the Soviet Union's strategy of blending scientific achievement with defense applications.

As the Salyut program progressed, later missions like Salyut 6 and Salyut 7 improved upon earlier designs by allowing long-duration crewed missions and more complex experiments. These stations, with their expanded crew capacity and amenities for long term stay, carrying electric stoves, a refrigerator, and constant hot water.[130] The Salyut series effectively paved the way for future Soviet and later Russian space stations, including the Mir space station, which would become a significant part in the history of long-term space exploration.

The longest stay, aboard Salyut 7, was 237 days.[131]

Program secrecy

[edit]

The Soviet space program had withheld information on its projects predating the success of Sputnik, the world's first artificial satellite. In fact, when the Sputnik project was first approved, one of the most immediate courses of action the Politburo took was to consider what to announce to the world regarding their event.[132]

The Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) established precedents for all official announcements on the Soviet space program.[133] The information eventually released did not offer details on who built and launched the satellite or why it was launched. The public release revealed, "there is an abundance of arcane scientific and technical data... as if to overwhelm the reader with mathematics in the absence of even a picture of the object".[8] What remains of the release is the pride for Soviet cosmonautics and the vague hinting of future possibilities then available after Sputnik's success.[134]

The Soviet space program's use of secrecy served as both a tool to prevent the leaking of classified information between countries and also to create a mysterious barrier between the space program and the Soviet populace. The program's nature embodied ambiguous messages concerning its goals, successes, and values. Launchings were not announced until they took place. Cosmonaut names were not released until they flew. Mission details were sparse. Outside observers did not know the size or shape of their rockets or cabins or most of their spaceships, except for the first Sputniks, lunar probes and Venus probe.[135]

However, the military influence over the Soviet space program may be the best explanation for this secrecy. The OKB-1 was subordinated under the Ministry of General Machine-Building,[8] tasked with the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles, and continued to give its assets random identifiers into the 1960s: "For example, the Vostok spacecraft was referred to as 'object IIF63' while its launch rocket was 'object 8K72K'".[8] Soviet defense factories had been assigned numbers rather than names since 1927. Even these internal codes were obfuscated: in public, employees used a separate code, a set of special post-office numbers, to refer to the factories, institutes, and departments.

The program's public pronouncements were uniformly positive: as far as the people knew, the Soviet space program had never experienced failure. According to historian James Andrews, "With almost no exceptions, coverage of Soviet space exploits, especially in the case of human space missions, omitted reports of failure or trouble".[8]

According to Dominic Phelan in the book Cold War Space Sleuths, "The USSR was famously described by Winston Churchill as 'a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma' and nothing signified this more than the search for the truth behind its space program during the Cold War. Although the Space Race was literally played out above our heads, it was often obscured by a figurative 'space curtain' that took much effort to see through."[135][136]

Projects and accomplishments

[edit]

Completed projects

[edit]The Soviet space program's projects include:

- Almaz space stations

- Cosmos satellites

- Foton

- Luna – Moon flybys, orbiters, impacts, landers, rovers, sample returns

- Mars probe program

- Meteor meteorological satellites

- Molniya communications satellites

- Mir space station

- Proton satellites

- Phobos Mars probes program

- Salyut space stations

- Soyuz program spacecraft

- Sputnik satellites

- TKS spacecraft

- Venera – Venus probes program

- Vega program – Venus and comet Halley probes program

- Vostok program spacecraft

- Voskhod program spacecraft

- Zond program

Notable firsts

[edit]

Two days after the United States announced its intention to launch an artificial satellite, on July 31, 1955, the Soviet Union announced its intention to do the same. Sputnik 1 was launched on October 4, 1957, beating the United States and stunning people all over the world.[137]

The Soviet space program pioneered many aspects of space exploration:

- 1957: First intercontinental ballistic missile and orbital launch vehicle, the R-7 Semyorka.

- 1957: First satellite, Sputnik 1.

- 1957: First animal in Earth orbit, the dog Laika on Sputnik 2.

- 1959: First rocket ignition in Earth orbit, first man-made object to escape Earth's gravity, Luna 1.

- 1959: First data communications, or telemetry, to and from outer space, Luna 1.

- 1959: First man-made object to pass near the Moon, first man-made object in Heliocentric orbit, Luna 1.

- 1959: First probe to impact the Moon, Luna 2.

- 1959: First images of the Moon's far side, Luna 3.

- 1960: First animals to safely return from Earth orbit, the dogs Belka and Strelka on Sputnik 5.

- 1961: First probe launched to Venus, Venera 1.

- 1961: First person in space (International definition) and in Earth orbit, Yuri Gagarin on Vostok 1, Vostok program.

- 1961: First person to spend over 24 hours in space Gherman Titov, Vostok 2 (also first person to sleep in space).

- 1962: First dual crewed spaceflight, Vostok 3 and Vostok 4.

- 1962: First probe launched to Mars, Mars 1.

- 1963: First woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova, Vostok 6.

- 1964: First multi-person crew (3), Voskhod 1.

- 1965: First extra-vehicular activity (EVA), by Alexsei Leonov,[138] Voskhod 2.

- 1965: First radio telescope in space, Zond 3.

- 1965: First probe to hit another planet of the Solar System (Venus), Venera 3.

- 1966: First probe to make a soft landing on and transmit from the surface of the Moon, Luna 9.

- 1966: First probe in lunar orbit, Luna 10.

- 1966: First image of the whole Earth disk, Molniya 1.[139]

- 1967: First uncrewed rendezvous and docking, Cosmos 186/Cosmos 188.

- 1968: First living beings to reach the Moon (circumlunar flights) and return unharmed to Earth, Russian tortoises and other lifeforms on Zond 5.

- 1969: First docking between two crewed craft in Earth orbit and exchange of crews, Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5.

- 1970: First soil samples automatically extracted and returned to Earth from another celestial body, Luna 16.

- 1970: First robotic space rover, Lunokhod 1 on the Moon.

- 1970: First full interplanetary travel with a soft landing and useful data transmission. Data received from the surface of another planet of the Solar System (Venus), Venera 7

- 1971: First space station, Salyut 1.

- 1971: First probe to impact the surface of Mars, Mars 2.

- 1971: First probe to land on Mars, Mars 3.

- 1971: First armed space station, Almaz.

- 1975: First probe to orbit Venus, to make a soft landing on Venus, first photos from the surface of Venus, Venera 9.

- 1980: First Asian person in space, Vietnamese Cosmonaut Pham Tuan on Soyuz 37; and First Latin American, Cuban and person with African ancestry in space, Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez on Soyuz 38

- 1984: First Indian Astronaut in space, Rakesh Sharma on Soyuz T-11 (Salyut-7 space station).

- 1984: First woman to walk in space, Svetlana Savitskaya (Salyut 7 space station).

- 1986: First crew to visit two separate space stations (Mir and Salyut 7).

- 1986: First probes to deploy robotic balloons into Venus atmosphere and to return pictures of a comet during close flyby Vega 1, Vega 2.

- 1986: First permanently crewed space station, Mir, 1986–2001, with a permanent presence on board (1989–1999).

- 1987: First crew to spend over one year in space, Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov on board of Soyuz TM-4 – Mir.

- 1988: First fully automated flight of a spaceplane (Buran).

Incidents, failures, and setbacks

[edit]Accidents and cover-ups

[edit]The Soviet space program experienced a number of fatal incidents and failures.[140]

The first official cosmonaut fatality during training occurred on March 23, 1961, when Valentin Bondarenko died in a fire within a low pressure, high oxygen atmosphere.

On April 23, 1967, Soyuz 1 crashed into the ground at 90 mph (140 km/h) due to a parachute failure, killing Vladimir Komarov. Komarov's death was the first in-flight fatality in the history of spaceflight.[141][142]

The Soviets continued striving for the first lunar mission with the N-1 rocket, which exploded on each of four uncrewed tests shortly after launch. The Americans won the race to land men on the Moon with Apollo 11 on July 20, 1969.

In 1971, the Soyuz 11 mission to stay at the Salyut 1 space station resulted in the deaths of three cosmonauts when the reentry capsule depressurized during preparations for reentry. This accident resulted in the only human casualties to occur in space (beyond 100 km (62 mi), as opposed to the high atmosphere). The crew members aboard Soyuz 11 were Vladislav Volkov, Georgy Dobrovolsky, and Viktor Patsayev.

On April 5, 1975, Soyuz 7K-T No.39, the second stage of a Soyuz rocket carrying two cosmonauts to the Salyut 4 space station malfunctioned, resulting in the first crewed launch abort. The cosmonauts were carried several thousand miles downrange and became worried that they would land in China, which the Soviet Union was having difficult relations with at the time. The capsule hit a mountain, sliding down a slope and almost slid off a cliff; however, the parachute lines snagged on trees and kept this from happening. As it was, the two suffered severe injuries and the commander, Lazarev, never flew again.

On March 18, 1980, a Vostok rocket exploded on its launch pad during a fueling operation, killing 48 people.[143]

In August 1981, Kosmos 434, which had been launched in 1971, was about to re-enter. To allay fears that the spacecraft carried nuclear materials, a spokesperson from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the USSR assured the Australian government on 26 August 1981, that the satellite was "an experimental lunar cabin". This was one of the first admissions by the Soviet Union that it had ever engaged in a crewed lunar spaceflight program.[66]: 736

In September 1983, a Soyuz rocket being launched to carry cosmonauts to the Salyut 7 space station exploded on the pad, causing the Soyuz capsule's abort system to engage, saving the two cosmonauts on board.[144]

Buran

[edit]

The Soviet Buran program attempted to produce a class of spaceplanes launched from the Energia rocket, in response to the US Space Shuttle. It was intended to operate in support of large space-based military platforms as a response to the Strategic Defense Initiative. Buran only had orbital maneuvering engines, unlike the Space Shuttle, Buran did not fire engines during launch, instead relying entirely on Energia to lift it out of the atmosphere. It copied the airframe and thermal protection system design of the US Space Shuttle Orbiter, with a maximum payload of 30 metric tons (slightly higher than that of the Space Shuttle), and weighed less.[145] It also had the capability to land autonomously. Due to this, some retroactively consider it to be the more capable launch vehicle.[146] By the time the system was ready to fly in orbit in 1988, strategic arms reduction treaties made Buran redundant. On November 15, 1988, Buran and its Energia rocket were launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, and after two orbits in three hours, glided to a landing a few miles from its launch pad.[147] While the craft survived that re-entry, the heat shield was not reusable. This failure resulted from United States counter intelligence efforts.[148] After this test flight, the Soviet Ministry of Defense would defund the program, considering it relatively pointless compared to its price.[149]

Polyus satellite

[edit]The Polyus satellite was a prototype orbital weapons platform designed to destroy Strategic Defense Initiative satellites with a megawatt carbon-dioxide laser.[150] Launched mounted upside-down on its Energia rocket, its single flight test was a failure when the inertial guidance system failed to rotate it 180° and instead rotated a complete 360°.[151]

Canceled projects

[edit]Energia rocket

[edit]

The Energia was a successfully developed super heavy-lift launch vehicle which burned liquid hydrogen fuel. But without the Buran or Polyus payloads to launch, it was also canceled due to lack of funding on dissolution of the USSR.

Interplanetary projects

[edit]Mars missions

[edit]- Heavy rover Mars 4NM was going to be launched by the abandoned N1 launcher between 1974 and 1975.

- Mars sample return mission Mars 5NM was going to be launched by a single N1 launcher in 1975.

- Mars sample return mission Mars 5M or (Mars-79) was to be double launched in parts by Proton launchers, and then joined in orbit for flight to Mars in 1979.[citation needed]

Vesta

[edit]The Vesta mission would have consisted of two identical double-purposed interplanetary probes to be launched in 1991. It was intended to fly-by Mars (instead of an early plan to Venus) and then study four asteroids belonging to different classes. At 4 Vesta a penetrator would be released.

Tsiolkovsky

[edit]The Tsiolkovsky mission was planned as a double-purposed deep interplanetary probe to be launched in the 1990s to make a "sling shot" flyby of Jupiter and then pass within five or seven radii of the Sun. A derivative of this spacecraft would possibly be launched toward Saturn and beyond.[152]

See also

[edit]- DRAKON, an algorithmic visual programming language developed for the Buran space project.

- Intercosmos, a Soviet space program designed to give nations on friendly relations with the Soviet Union access to crewed and uncrewed space missions

- List of Russian aerospace engineers

- List of Russian explorers

- List of space disasters

- Pilot-Cosmonaut of the USSR, an honorary title

- Roscosmos, the program's eventual post-Soviet continuation under the Russian Federation

- Roscosmos Cosmonaut Corps, Russian astronaut corps

- Sheldon names, which were used to identify launch vehicles of the Soviet Union when their Soviet names were unknown in the USA

- Soviet rocketry

- Space Race

- Tank on the Moon, a 2007 French documentary film on the Lunokhod program

References

[edit]- ^ Полвека без Королёва, zavtra.ru. Archived 28 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Reichl, Eugen (2019). The Soviet Space Program: The Lunar Mission Years: 1959–1976. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, Limited. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7643-5675-9. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ "Space Race Timeline".

- ^ "2 апреля 1955 года «Об образовании общесоюзного Министерства общего машиностроения СССР»". Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ^ Вертикальная структура: как реорганизуется космическая отрасль России, АиФ. Archived 30 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Postal Stationery Russia Airmail Envelope with Depiction of the Earth Being Orbited and Four Gold Stars". groundzerobooksltd.com. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Andrews, James T.; Siddiqi, Asif A. (2011). Into the Cosmos: Space Exploration and Soviet Culture. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-7746-9. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Chertok 2005, pp. 9–10, 164–165 Vol 1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 6–14.

- ^ "Home | AIAA". Archived from the original on January 4, 2012.

- ^ "Famous firsts in space". CNN. Cable News Network. April 9, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Article title

- ^ "Behind the Iron Curtain: The Soviet Venera program". August 26, 2020.

- ^ Brian Dunbar (April 19, 2021). "50 Years Ago: Launch of Salyut, the World's First Space Station". NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Sheehan, Michael (2007). The international politics of space. London: Routledge. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-415-39917-3.

- ^ Burgess, Colin; Hall, Rex (2008). The first Soviet cosmonaut team: their lives, legacy, and historical impact. Berlin: Springer. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-387-84823-5.

- ^ http://www.roscosmos.ru/index.asp?Lang=ENG Archived October 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Russian Right Stuff DVD Set Space Program Secret History 2 Discs". mediaoutlet.com. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Baker & Zak 2013, p. 3.

- ^ "Konstantin Tsiolkovsky Brochures" (PDF). Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^

Wilford, John (1969). We Reach the Moon; the New York Times Story of Man's Greatest Adventure. New York: Bantam Paperbacks. p. 167. ISBN 0-373-06369-0

{{isbn}}: ignored ISBN errors (link). - ^ Harvey, Brian (2007). Russian Planetary Exploration: History, Development, Legacy and Prospects. Springer.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 3.

- ^ Zander's 1925 paper, “Problems of flight by jet propulsion: interplanetary flights,” was translated by NASA. See NASA Technical Translation F-147 (1964); specifically, Section 7: Flight Around a Planet's Satellite for Accelerating or Decelerating Spaceship, pp. 290–292.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 6.

- ^ a b Chertok 2005, p. 164 Vol 1.

- ^ a b c Zak, Anatoly. "Gas Dynamics Laboratory". Russian Space Web. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "Russian Rocket Projectiles – WWII". Weapons and Warfare. November 18, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Siddiqi 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 165 Vol 1.

- ^ a b Siddiqi 2000, p. 4.

- ^ "Late great engineers: Sergei Korolev – designated designer". The Engineer. June 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Baker & Zak 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 166 Vol 1.

- ^ Okninski, Adam (December 2021). "Hybrid rocket propulsion technology for space transportation revisited – propellant solutions and challenges". FirePhysChem. 1 (4): 260–271. Bibcode:2021FPhCh...1..260O. doi:10.1016/j.fpc.2021.11.015. S2CID 244899773.

- ^ "GIRD (Gruppa Isutcheniya Reaktivnovo Dvisheniya)". WEEBAU. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Baker & Zak 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 167 vol 1.

- ^ Pobedonostsev, Yuri A. (1977). "On the History of the Development of Solid-Propellant Rockets in the Soviet Union". NASA Conference Publication. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Scientific and Technical Information Office: 59–63.

- ^ "Greatest World War II Weapons : The Fearsome Katyusha Rocket Launcher". Defencyclopidea. February 20, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Siddiqi 2000, p. 9.

- ^ Chertok 2005, pp. 167–168 Vol 1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 11–14.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 22.

- ^ "Tikhonravov, Mikhail Klavdievich". Russian Space Web. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ Chertok 2005, p. 207 Vol 1.

- ^ Chertok 2005, pp. 174, 207 Vol 1.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, p. 15.

- ^ "Last of the Wartime Lavochkins". Air International. 11 (5). Bromley, Kent: 245–246. November 1976.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 21–22.

- ^ "Vladimir Nikolayevich". astronautix. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ Chertok 2005, pp. 215–369 Vol 1.

- ^ Chertok 2005, pp. 43–71 Vol 2.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 24–82.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly. "Official decisions on the deportation of Germans". Russian Space Web. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 37–42.

- ^ Hebestreit, Gunther. "Geheimoperation OSSAWIAKIM: Die Verschleppung deutscher Raketenwissenschaftler in die Sowjetunion" [Secret operation Ossawiakim: The relocation of German rocket scientists into the Soviet Union]. Förderverein Institut RaBe e.V. Archived from the original on December 4, 2024. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

An order from Moscow was read to the people who had been awakened from their sleep, in which they were informed that the Zentralwerke were to be relocated to the Soviet Union, which affected both the facilities and equipment and the personnel.

- ^ Siddiqi 2000, pp. 40, 63, 83–84.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Siddiqi, Asif Azam (2000). Challenge To Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945–1974 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA History Div. ISBN 9780160613050. Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ Korolev, Sergei; Riabikov, Vasilii (2008). On Work to Create an Artificial Earth Satellite. Baturin.

- ^ "The Soviet Manned Lunar Program".

- ^ M.K. Tikhonravov, Memorandum on an Artificial Earth Satellite, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, orig. May 26, 1954, Published in Raushenbakh, editor (1991), 5–15. Edited by Asif Siddiqi and translated by Gary Goldberg. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/165393

- ^ "The Historic Beginnings Of The Space Arms Race". www.spacewar.com. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ RBTH; Novosti, Yury Zaitsev, RIA (November 1, 2008). "The historic beginnings of the space arms race". Russia Beyond. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Hidden History of the Soviet Satellite-Killer". Popular Mechanics. November 1, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2024.

- ^ Adam Mann (July 28, 2020). "The Vostok Program: The Soviet's first crewed spaceflight program". space.com. Future US, Inc. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ Asif Siddiqi (June 2019). "Why the Soviets Lost the Moon Race". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "James Oberg's Pioneering Space". www.jamesoberg.com. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- ^ "Йепхл Юкхебхв Йепхлнб". Space.hobby.ru (in Russian). Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Asif Azam Siddiqi (2000). Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945–1974. NASA. p. 94. ISBN 9780160613050.

- ^ "NASA – Vladimir Komarov and Soyuz 1". Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c Nicholas L. Johnson (1995). "The Soviet Reach for The Moon" (PDF). usra.edu. USRA. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "LEK Lunar Expeditionary Complex". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ "DLB Module". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ a b "Luna 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ a b "Luna 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 3". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 9". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 10". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 12". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 3". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 3 photography". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 13". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "50 Years Ago: Zond 4 launched successfully. - NASA". March 6, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Zond 5". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 7". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Zond 8". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 15". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 16". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 17". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Luna 20". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "50 Years Later, the Soviet Union's Luna Program Might Get a Reboot". Popular Mechanics. July 18, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "Venera 7". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venera 7, The First Craft to Make Controlled Landing on Another Planet And Send Data From its Surface". www.amusingplanet.com. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Venera 7". weebau.com. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Plumbing the Atmosphere of Venus". mentallandscape.com. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Venera 8". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venera 9". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venera 9 descent craft". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Venus - Venera 10 Lander". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "A history of the search for life on Venus". www.skyatnightmagazine.com. September 14, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Venera 11 & 12 probes to Venus". heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "Venera 11 descent craft". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ a b "Venera 13". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Surface of Venus". pages.uoregon.edu. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "Drilling into the Surface of Venus". mentallandscape.com. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "Venera 14". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Vega 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Vega 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "In Depth | Vega 2". NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ Harland, David M. (1999). The Soviet Space Program: The History of the U.S.S.R.'s Space Achievements. Springer.

- ^ "Mars 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Mars 3". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Mars 5". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Mars 4". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ a b "50 Years Ago: Launch of Salyut, the World's First Space Station - NASA". April 19, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "Salyut 1". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Russia's early space stations (1969-1985)". russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "Salyut 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Salyut-3 (OPS-2) space station". www.russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved November 19, 2024.

- ^ "Salyut 7". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "The First Space Stations". airandspace.si.edu. August 15, 2023. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "The Soviet Space Program by Eric Mariscal". Prezi.com. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ "TASS history".

- ^ "The start of the Space Race (article)". Khan Academy. October 1, 1958. Retrieved March 8, 2022.

- ^ a b "OhioLINK Institution Selection". Ebooks.ohiolink.edu. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Dominic Phelan (2013). "Cold War Space Sleuths" (PDF). springer.com. Praxis Publishing. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Launius, Roger (2002). To Reach the High Frontier. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 7–10. ISBN 0-8131-2245-7.

- ^ Rincon, Paul; Lachmann, Michael (October 13, 2014). "The First Spacewalk How the first human to take steps in outer space nearly didn't return to Earth". BBC News. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Joel Achenbach (January 3, 2012). "Spaceship Earth: The first photos". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ James E Oberg (1981). Red Star in Orbit. Random House. ISBN 978-0394514291.

- ^ Tragic Tangle, System Failure Case Studies, NASA

- ^ Vladimir Komarov and Soyuz 1 Archived November 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, NASA

- ^ "Media Reports | Soviet rocket blast left 48 dead". BBC News. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Schmemann, Serge (October 12, 1983). "Soyuz Accident Quietly Conceded". New York Times. United States. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Buran Space Shuttle vs STS – Comparison". www.buran.su. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (November 19, 2013). "Did the USSR Build a Better Space Shuttle?". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (November 20, 2008). "Buran – the Soviet space shuttle". BBC.

- ^ Windrem, Robert (February 11, 2008). "How the Soviet space shuttle fizzled". NBC News. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "Buran reusable shuttle". www.russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ Konstantin Lantratov. "Звёздные войны, которых не было" [Star Wars that didn't happen].

- ^ Ed Grondine. "Polyus". Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (February 5, 2013). "Planetary spacecraft". Russian Space Web. Retrieved May 13, 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Andrews, James T.: Red Cosmos: K. E. Tsiolkovskii, Grandfather of Soviet Rocketry. (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009)

- Brzezinski, Matthew: Red Moon Rising: Sputnik and the Hidden Rivalries that Ignited the Space Age. (Holt Paperbacks, 2008)

- Burgess, Colin; French, Francis: Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961–1965. (University of Nebraska Press, 2007)

- Burgess, Colin; French, Francis: In the Shadow of the Moon: A Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965–1969. (University of Nebraska Press, 2007)

- Harford, James: Korolev: How One Man Masterminded the Soviet Drive to Beat America to the Moon. (John Wiley & Sons, 1997)

- Siddiqi, Asif A.: Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945–1974. (Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2000)

- Siddiqi, Asif A.: The Red Rockets' Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857–1957. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010)

- Siddiqi, Asif A.; Andrews, James T. (eds.): Into the Cosmos: Space Exploration and Soviet Culture. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011)

- Baker, David; Zak, Anatoly (2013). Race for Space 1: Dawn of the Space Age. RHK. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- Chertok, Boris (January 31, 2005). Rockets and People (Volumes 1–4 ed.). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- Rödel, Eberhard (2018). The Soviet space program: first steps: 1941–1953. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0764355394.

- Reichl, Eugen (2019). The Soviet Space Program: The Lunar Mission Years: 1959–1976 (1st ed.). Schiffer Military History. ISBN 978-0-7643-5675-9.

- Reichl, Eugen (2019). The Soviet space program: the N1, the Soviet Moon rocket. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0764358555.

- Burgess, Colin; Hall, Rex (2009). The First Soviet Cosmonaut Team: Their Lives, Legacy, and Historical Impact. Praxis. ISBN 978-0-387-84824-2.

External links

[edit]Soviet space program

View on GrokipediaIdeological and Geopolitical Foundations

Marxist-Leninist Motivations for Space Conquest

The Soviet space program was ideologically positioned as a manifestation of Marxist-Leninist principles, wherein technological mastery over space served to empirically validate the superiority of proletarian collectivism against capitalist individualism, enabling the state-directed mobilization of human and material resources on a scale deemed impossible under private enterprise.[7] This framing drew from dialectical materialism's emphasis on transformative leaps in production forces as historical necessities, rejecting incremental "bourgeois" approaches in favor of concentrated, ideologically driven efforts that aligned scientific progress with class struggle.[8] Soviet propagandists and leaders portrayed rocketry and cosmonautics not as neutral engineering feats, but as extensions of the proletarian revolution into the cosmos, fulfilling Lenin's dictum that communism required the full electrification—and by extension, technological electrification—of society to overcome scarcity and backwardness.[9] Vladimir Lenin conceptualized science and technology as instruments of class emancipation, arguing that under socialism, productive forces could be rationally organized to serve the masses, free from capitalist exploitation that subordinated innovation to profit.[10] This view, echoed in Joseph Stalin's industrialization drives, treated advanced technology as a "class weapon" for bolstering the dictatorship of the proletariat, with rocketry emerging from wartime missile programs as a tool for both defense and ideological assertion of Soviet prowess amid resource constraints.[11] Stalin's regime, despite purges that decimated scientific cadres, prioritized state-funded technical intelligentsia to achieve self-sufficiency, viewing successes in heavy industry and armaments as preludes to conquering natural frontiers like space, thereby demonstrating the planned economy's capacity for directed leaps over market-driven diffusion.[12] Following Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev's de-Stalinization campaign intensified the space program's role as a prestige mechanism to reaffirm regime legitimacy, channeling ideological fervor into high-profile projects that masked domestic economic strains and agricultural failures by showcasing communist system's purported efficiency in harnessing collective will for epochal achievements.[13] Khrushchev's leadership accelerated resource allocation to rocketry despite competing priorities, framing these endeavors as dialectical resolutions to capitalist encirclement, where bold state initiatives could outpace Western incrementalism and propagate Marxist-Leninist teachings globally through tangible victories in the scientific domain.[14] This prioritization persisted even as it strained the economy, underscoring a causal prioritization of ideological projection over immediate material welfare, consistent with the Leninist imperative to build socialism through mastery of nature's forces.[15]Cold War Competition with the United States

The geopolitical rivalry of the Cold War framed space exploration as an arena for demonstrating technological and ideological superiority, with Soviet rocketry advancements rooted in military imperatives that enabled rapid civilian applications. The Soviet Union prioritized intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) development, achieving successful R-7 tests in mid-1957, which allowed quick repurposing of this clustered engine design for orbital launches amid perceived U.S. nuclear threats.[16][17] This dual-use approach contrasted with U.S. efforts, where Project Vanguard's December 6, 1957, launch failure—resulting in a televised explosion—exposed delays in non-military satellite rocketry, inadvertently amplifying Soviet momentum by underscoring American setbacks just weeks after initial Soviet orbital success.[18][19] U.S. intelligence, including CIA National Intelligence Estimates, frequently underestimated Soviet missile reliability and adaptation speed in the 1950s, projecting lower ICBM operational rates and overlooking the R-7's versatility for space payloads, which fueled post-Sputnik escalation on both sides.[20][21] Such assessments, varying between conservative figures for Soviet ground forces and missile deployments, contributed to reactive U.S. policy shifts, including increased funding, while Soviet leaders exploited intelligence gaps for opportunistic advances. Espionage played a limited role compared to indigenous innovation, though mutual surveillance via overflights and defectors informed threat perceptions driving the competition.[22] Strategic priorities diverged asymmetrically: Soviet efforts targeted prestige-laden "firsts" to propagate Marxist-Leninist triumphs, leveraging centralized control for swift, high-risk milestones, whereas U.S. responses emphasized comprehensive, enduring capabilities like sustained lunar exploration to secure long-term dominance.[23][24] This Soviet focus on symbolic victories, contrasted with American systematic scaling, revealed planning variances—Soviet programs often prioritized propaganda over reliability, leading to early leads but later sustainability challenges—amid broader deterrence dynamics where space feats signaled military potential.[25]Early Theoretical and Experimental Roots

Pre-Revolutionary Influences and Soviet Pioneers

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a self-taught physicist in Tsarist Russia, provided the theoretical bedrock for rocketry through rigorous derivations grounded in Newtonian mechanics. In his 1903 treatise Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices, Tsiolkovsky formulated the core equation of rocketry—Δv = v_e \ln(m_0 / m_f)—quantifying the change in velocity (Δv) achievable via exhaust velocity (v_e) and the ratio of initial to final mass (m_0 / m_f), which demonstrated the impracticality of single-stage rockets for orbital velocities exceeding 8 km/s. This analysis, derived from conservation of momentum without reliance on empirical data beyond basic physics, necessitated multi-stage configurations to exponentially reduce mass while compounding velocity increments, and highlighted the superiority of high-specific-impulse liquid propellants over solids. Tsiolkovsky further specified liquid oxygen and hydrogen as optimal fuels in this work, prioritizing thermodynamic efficiency for sustained thrust.[26][27][28] Earlier, in 1895, Tsiolkovsky conceptualized a space elevator as a tapered cable from Earth's surface to geostationary orbit, calculating the required material strength to counter gravitational and centrifugal forces, though he acknowledged its dependence on unattainable tensile properties of contemporary materials. These pre-revolutionary contributions, disseminated in obscure journals amid Tsiolkovsky's isolation in Kaluga, emphasized causal propulsion physics—thrust as reaction mass expulsion—over speculative narratives, influencing subsequent engineers despite limited state support under the Tsars.[29][30] Post-1917, Bolshevik-era pioneers operationalized Tsiolkovsky's principles through hands-on propulsion tests. Friedrich Tsander, a Riga-born engineer active from the early 1920s, built and statically tested liquid-fueled engines using nitrous oxide and gasoline, achieving verifiable combustion stability and thrust measurements that validated Tsiolkovsky's efficiency predictions, though limited by rudimentary cryogenics yielding specific impulses below 200 seconds. Tsander's 1924 designs incorporated regenerative cooling to mitigate nozzle erosion, drawing directly from first-principles heat transfer analysis.[31][32] Mikhail Tikhonravov, transitioning from glider aviation in the mid-1920s, integrated solid-hybrid propulsion into winged testbeds, conducting towed and powered flights to empirically assess reaction control in near-space regimes; his 1930 experiments measured drag reductions and altitude gains up to 1 km, confirming theoretical ascent profiles while exposing vibration-induced failures in early composites. These efforts prioritized quantifiable data—thrust-to-weight ratios and burnout velocities—over visionary claims, yet faced interruptions from resource shortages and the 1937-1938 purges, which repressed innovators and stalled prototype scaling until wartime imperatives.[33][34]Formation of Key Organizations (GIRD, RNII)

The Group for the Study of Reactive Motion (GIRD) was established on September 15, 1931, in Moscow as a voluntary association of engineers and scientists dedicated to jet propulsion research, initiated by Mikhail Tikhonravov with support from the Communist Academy and trade unions. Initially funded through public subscriptions and proletarian organizations, GIRD received direct Soviet government sponsorship starting in 1932, reflecting early recognition of rocketry's potential military applications in propulsion and weaponry.[35] On August 17, 1933, GIRD achieved the Soviet Union's first successful liquid-propellant rocket launch with the GIRD-09, utilizing liquid oxygen and jellied gasoline to reach an altitude of approximately 400 meters.[36] In September 1933, GIRD merged with the Gas Dynamics Laboratory (GDL) to form the Reactive Scientific Research Institute (RNII) on September 21, by decree of the Revolutionary Military Council, consolidating fragmented rocketry efforts under state military oversight to prioritize applied development for defense needs.[37] RNII produced early prototypes, including the ORM-65 liquid-fueled rocket engine tested in 1937, which powered experimental vehicles and demonstrated scalability for winged rockets.[38] State funding under RNII emphasized dual-use technologies, linking civilian propulsion research to military rocketry for artillery and anti-aircraft roles, a pragmatic alignment driven by Stalin-era industrialization priorities rather than ideological space ambitions.[39] The Great Purge of 1937–1938 severely disrupted RNII, with arrests and executions of key personnel—including director Ivan Kleimenov and chief engineer Georgy Langemak, both shot in 1938 on fabricated sabotage charges—decimating leadership and halting projects amid widespread paranoia in scientific institutions.[40] This repression, which claimed lives like that of RNII deputy Iosif Gruzdev, reflected Stalin's suspicion of technical elites as potential threats, prioritizing political loyalty over expertise and foreshadowing vulnerabilities in Soviet rocketry's institutional stability.[40] Despite these setbacks, RNII's foundational work laid groundwork for wartime missile programs, sustained by the regime's instrumental view of science as a tool for power projection.World War II and Postwar Rocketry Foundations

Wartime Missile Developments

During World War II, Soviet rocketry efforts prioritized tactical solid-propellant unguided rockets for immediate military application, with the BM-13 Katyusha multiple launch rocket system representing the pinnacle of indigenous wartime production. Deployed from July 1941, the Katyusha fired M-13 rockets with ranges of 8.5 to 20 kilometers, enabling massed fire support in key battles such as Stalingrad and Kursk.[41] Over 500,000 such rockets were manufactured annually from 1942 to 1944, demonstrating scalable production despite wartime disruptions, though accuracy remained limited to area saturation due to lack of guidance systems.[41] Liquid-fueled rocketry, advanced pre-war by organizations like GIRD and RNII, stalled amid the 1930s purges and invasion demands, with no significant long-range ballistic missile prototypes completed by 1944. Engineers addressed empirical challenges through trial-and-error, including propellant instability in early solid fuels and trajectory inaccuracies from crude aerodynamics, refined via field tests and static firings under duress.[42] Sergei Korolev, imprisoned from 1938 to 1944 for alleged sabotage, contributed indirectly by maintaining theoretical expertise during confinement in aviation design bureaus; upon release in mid-1944, he led conceptual work on long-range designs like the RDD project, initiated in November 1944 to counter intelligence on German capabilities.[43] These wartime experiences in mass deployment and iterative testing laid essential groundwork for post-war advancements, emphasizing reliability over precision in resource-scarce conditions, though systemic biases in Soviet reporting often overstated indigenous progress relative to actual technical constraints.[44]Exploitation of German V-2 Technology

Following the end of World War II, the Soviet Union conducted Operation Osoaviakhim on the night of October 21–22, 1946, a large-scale NKVD-led deportation that forcibly relocated approximately 2,552 German specialists, including rocket engineers and technicians from former Nazi facilities, along with their families totaling around 6,560 individuals, to the USSR for technology transfer purposes.[45] This operation targeted experts in armaments, aviation, and rocketry, with many assigned to secret sites such as Gorodomlya Island in Lake Seliger, where they worked under Soviet oversight to reconstruct and analyze captured V-2 (A-4) rocket components and documentation seized from eastern German territories.[46] The effort complemented earlier postwar scavenging, including the capture of over 100 incomplete V-2 missiles and production tooling from Mittelwerk factories, enabling the Soviets to bypass some foundational development hurdles in liquid-propellant rocketry.[47] Under the direction of Soviet engineers like Sergei Korolev and Helmut Gröttrup (a key German lead from the V-2 team), the relocated specialists first focused on assembling and statically testing captured V-2 hardware, culminating in the USSR's initial full launches of reproduction V-2 rockets from Kapustin Yar test range starting in September 1947, with 13 German engineers directly involved in preparations for early flights that October.[48] These tests revealed gaps in Soviet industrial replication, including inconsistencies in high-purity ethanol production for the RF-4 fuel mixture (75% ethanol, 25% water) and challenges in forging turbine blades and gyroscopic guidance components due to incomplete German blueprints and domestic metallurgy limitations, resulting in several launch failures from engine stalls and structural weaknesses.[49] By mid-1948, Soviet-led reverse-engineering efforts yielded the R-1 missile, a near-direct copy of the V-2 with identical 13.4-tonne mass, 25-tonne thrust engine, and 270–300 km range, achieving its first successful target impact on October 10, 1948, after initial test flights in April and September that validated basic flight profiles despite ongoing supply chain bottlenecks.[48] The exploitation provided a critical technological baseline, with joint Soviet-German teams preparing around 20 operational V-2 replicas for testing, which informed guidance algorithms and propulsion scaling that accelerated the transition to indigenous variants like the R-2 by 1949, though declassified accounts indicate heavy initial reliance on appropriated designs strained Soviet innovation by diverting resources from parallel domestic engine research and exposed vulnerabilities in scaling production without full mastery of underlying materials science.[47] While this scavenging enabled the USSR to field its first ballistic missile regiment equipped with R-1s by 1950, it underscored causal limitations in coerced knowledge transfer, as many German specialists lacked access to proprietary Peenemünde data held by the Western Allies, compelling Soviets to iteratively refine components through trial-and-error amid postwar industrial shortages.[50] By 1949, the Germans' role diminished as Soviet authorities repatriated most non-essential experts, shifting emphasis to native teams that adapted V-2 principles into clustered-booster architectures, though early designs retained core elements like alcohol-LOX turbopumps traceable to the originals.[48]Ignition of the Space Race: Sputnik Era

Launch of Sputnik 1 (1957)