Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Medieval antisemitism

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Antisemitism in the history of the Jews in the Middle Ages became increasingly prevalent in the Late Middle Ages.[1] Early instances of pogroms against Jews are recorded in the context of the First Crusade. Expulsions of Jews from cities and instances of blood libel became increasingly common from the 13th to the 15th century. This trend only peaked after the end of the medieval period, and it only subsided with Jewish emancipation in the late 18th and 19th centuries.[2]

Accusations of deicide

[edit]In the Middle Ages, religion played a major role in fueling antisemitism. Even though it is not a part of Roman Catholic dogma, many Christians, including many members of the clergy, have held the Jewish people collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus, through the so-called blood curse of Pontius Pilate in the Gospels, among other things.[1]

As stated in the Boston College Guide to Passion Plays, "Over the course of time, Christians began to accept... that the Jewish people as a whole were responsible for killing Jesus. According to this interpretation, both the Jews present at Jesus’ death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time, have committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing. For 1900 years of Christian-Jewish history, the charge of deicide (which was originally attributed by Melito of Sardis) has led to hatred, violence against and murder of Jews in Europe and America."[3]

This accusation was repudiated by the Catholic Church in 1964 under Pope Paul VI issued the document Nostra aetate as a part of Vatican II.

Restrictions to marginal occupations

[edit]Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to the Jews, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, tolerating them as a "necessary evil". Catholic doctrine of the time held that lending money for interest was a sin, and forbidden to Christians. Not being subject to this restriction, Jews dominated this business. The Torah and later sections of the Hebrew Bible criticise usury but interpretations of the Biblical prohibition vary (the only time Jesus used violence was against money changers taking a toll to enter temple). Since few other occupations were open to them, Jews were motivated to take up money lending, and increasingly became associated with usury by antisemitic Christians.[4] This was said to show Jews were insolent, greedy, usurers, and subsequently led to many negative stereotypes and propaganda. Natural tensions between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) were added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants who were forced to pay their taxes to Jews could personify them as the people taking their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords on whose behalf the Jews worked.[5] Jews' role as moneylenders was later used against them, part of the justification in expelling them from England when they lacked the funds to continue lending the king money.[citation needed]

The Black Death

[edit]

The Black Death plague devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than a half of the population, with Jews being made scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence, in particular in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence, 40 Jews were burnt in Toulon as early as April 1348.[6] "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague ; they were tortured until they confessed to crimes that they could not possibly have committed.[citation needed]

"The large and significant Jewish communities in such cities as Nuremberg, Frankfurt, and Mainz were wiped out at this time."(1406)[7] In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambéry (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet's "confession", the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on 14 February 1349.[8][9]

Although the Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by the 6 July 1348 papal bull and another 1348 bull, several months later, 900 Jews were burnt in Strasbourg, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city.[6] Clement VI condemned the violence and said those who blamed the plague on the Jews (among whom were the flagellants) had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil."[10]

Demonization of the Jews

[edit]From around the 12th century through the 19th there were Christians who believed that some (or all) Jews possessed magical powers; some believed that they had gained these magical powers from making a deal with the devil.[citation needed]

Blood libels

[edit]On many occasions, Jews were accused of a blood libel, the supposed drinking of blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. According to the authors of these blood libels, the 'procedure' for the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses and then drunk. Finally, the child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed of, but in some instances rituals of black magic would be performed on it.[citation needed]

The story of William of Norwich (d. 1144) is often cited as the first known accusation of ritual murder against Jews. The Jews of Norwich, England were accused of murder after a Christian boy, William, was found dead. It was claimed that the Jews had tortured and crucified their victim. The legend of William of Norwich became a cult, and the child acquired the status of a holy martyr. Recent analysis has cast doubt on whether this was the first of the series of blood libel accusations but not on the contrived and antisemitic nature of the tale.[11]

During the Middle Ages blood libels were directed against Jews in many parts of Europe. The believers of these accusations reasoned that the Jews, having crucified Jesus, continued to thirst for pure and innocent blood and satisfied their thirst at the expense of innocent Christian children. Following this logic, such charges were typically made in Spring around the time of Passover, which approximately coincides with the time of Jesus' death.[12]

The story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) said that after the boy was dead, his body was removed from the cross and laid on a table. His belly was cut open and his entrails were removed for some occult purpose, such as a divination ritual. The stories of Jews committing blood libel were so widespread that the story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln was even used as a source for "The Prioress's Tale," one of the tales included in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales.[citation needed]

Prior to the late 16th century, the Catholic Church officially condemned accusations of blood libel against Jews. The earliest papal bull on the subject, from Innocent IV in 1247, defended the Jews against claims of ritual murder and blood libel that had emerged in the Polish ecclesiastical authorities.[13] In 1272, Pope Gregory X issued a papal bull that synthesized earlier documents and conclusively established the Church's disapproval of blood libel accusations: "Most falsely do these Christians claim that the Jews have secretly and furtively carried away these children and killed them... we order that Jews seized under such a silly pretext be freed from imprisonment."[14][better source needed] In the late 15th century, however, following the 1475 death of Simon of Trent, a toddler who was claimed to have been ritually murdered by the Jews of Trent, Germanic ecclesiastical authorities began pushing back against the Church's condemnation. Having convicted and executed several prominent Jews, Bishop Johannes Hinderbach of Trent widely disseminated accounts of miracles performed by Simon of Trent, and wrote several letters to Pope Sixtus IV extolling the "devotion and ardor" of pilgrims who had come to worship Simon's cult.[13] For the next three years, Hinderbach continued to lobby jurists and scholars in Rome, and several prominent legal authorities issued rulings in support of both the prosecution's findings and the canonization of Simon.[13] Perhaps due to this popular pressure, Pope Sixtus IV issued a papal bull that declared the trial legal, but did not officially recognize the Jews' guilt, thereby closing off the possibility of Simon's martyrdom.[13] Simon's popularity persisted, however, and in 1583, Pope Gregory XIII added Simon's name to Roman Martyrology, an official source on martyrs of the Roman Catholic Church. This addition, and its corresponding recognition of the local cult of Simon of Trent, halted the Church's condemnations of blood libel accusations until 1759.[15]

Association with misery

[edit]In medieval England, Jews were often associated with feelings of misery, dismay, and sadness. According to Thomas Coryate, "to look like a Jew" meant to look disconnected from oneself. This stereotype pervaded all aspects of life, with David Nirenberg noting that Elizabethan cookbooks emphasised Jewish misery.[16][full citation needed]

Host desecration

[edit]Jews were sometimes falsely accused of desecrating consecrated hosts in a reenactment of the Crucifixion by performing a ritual stealing and then stabbing the hosts until the wafer supposedly bled, which became a theological extension of the blood libel accusation that Jews ritually murdered Christian children. This crime was known as host desecration and carried the death penalty.[1]

Disabilities and restrictions

[edit]

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal disabilities and restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations varying with place and time, and determined by the influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden. The number of Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos[17] and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own, were forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and suffered a variety of other measures, including restrictions on dress.[1]

Clothing

[edit]The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was the first to proclaim the requirement for Jews to wear something that distinguished them as Jews. It could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape of a star or circle or square, a Jewish hat (already a distinctive style), or a robe. In many localities, members of medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as guild members) were prestigious, while others ostracised outcasts such as lepers, reformed heretics and prostitutes. The local introduction and enforcement of these rules varied greatly. Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid whenever the king needed to raise funds.[1]

The Crusades

[edit]

The mobs accompanying the First Crusade, and particularly the People's Crusade of 1096, attacked the Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and put many Jews to death. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Troyes, Mainz, and Cologne, were slain during the First Crusade by a mob army. "...on their journey east, wherever the mob of cross-bearing crusaders descended they slaughtered the Jews."[18] About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July 1096. Before the Crusades the Jews had practically a monopoly of trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of merchant traders among the Christians, and from this time onward restrictions on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent. The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against the Jews as against the Muslims, though attempts were made by bishops during the First Crusade and the papacy during the Second Crusade to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III, and formed the turning point in the medieval history of the Jews.[citation needed]

In the County of Toulouse (now part of southern France) Jews were received on good terms until the Albigensian Crusade. Toleration and favour shown to the Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church against the Counts of Toulouse. Following the Crusaders' successful wars against Raymond VI and Raymond VII, the Counts were required to discriminate against Jews like other Christian rulers. In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII, underwent a similar ceremony where he was obliged to prohibit the public employment of Jews, this time at Notre Dame in Paris. Explicit provisions on the subject were included in the Treaty of Meaux (1229). By the next generation a new, zealously Catholic, ruler was arresting and imprisoning Jews for no crime, raiding their houses, seizing their cash, and removing their religious books. They were then released only if they paid a new "tax". A historian has argued that organised and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.[19]

Expulsions from England, France, Germany, Spain and Portugal

[edit]

In the Middle Ages in Europe persecutions and formal expulsions of Jews were liable to occur at intervals, although it should be said that this was also the case for other minority communities, whether religious or ethnic. There were particular outbursts of riotous persecution in the Rhineland massacres of 1096 in Germany accompanying the lead-up to the First Crusade, many involving the crusaders as they travelled to the East. There were many local expulsions from cities by local rulers and city councils. In Germany the Holy Roman Emperor generally tried to restrain persecution, if only for economic reasons, but he was often unable to exert much influence.[20][21] As late as 1519, the Imperial city of Regensburg took advantage of the recent death of Emperor Maximilian I to expel its 500 Jews.[22]

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during 12th-14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the entirety of France by Louis IX in 1254, by Philip IV in 1306, by Charles IV in 1322, by Charles VI in 1394.

To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others killed in their homes. The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands killed and drowned while fleeing and the absence of Jews from England for three and a half centuries, until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile issued General Edict on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and many Sephardi Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire, some to Palestine, to avoid the Spanish Inquisition.

The Kingdom of Portugal followed suit and in December 1496, it was decreed that any Jew who did not convert to Christianity would be expelled from the country. However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the King. When those who chose expulsion arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who used force, coercion, and promises in order to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country. This period of time technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants would be referred to as "New Christians" or Marranos (lit. "pigs" in Spanish), and they were given a grace period of thirty years in which no inquiries into their faith would be allowed; this was later to be extended to end in 1534. A popular riot in 1504 would end in the death of two thousand Jews; the leaders of this riot were executed by Manuel.

Anti-Judaism and the Reformation

[edit]

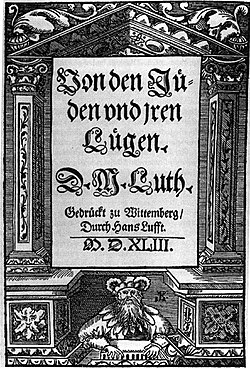

Martin Luther, an Augustinian friar and an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings inspired the Protestant Reformation, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his book On the Jews and their Lies, which describes the Jews in extremely harsh terms, excoriates them, and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom against them and their permanent oppression and/or expulsion. At one point in On the Jews and Their Lies, Martin Luther goes even as far to write "that we are at fault in not slaying them." Notably, Luther's intense hostility towards Jews moved away from a long-standing custom, developed by Augustine in the early fifth century, of assigning Jews the protected status as relics of the pre-Christ Biblical past who are thus useful to Christians and should not face expulsion. Luther's writings instead instigated another wave of political expulsions of Jewish populations from German localities, in the years immediately succeeding the release of “On the Jews and Their Lies” and for a few decades after the fact.[23] According to Paul Johnson, Luther's book "may be termed the first work of modern anti-Semitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."[24] In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther preached "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord."[25] Still, Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism.

Medieval antisemitic art

[edit]

During the Middle Ages, much art was created by Christians that depicted Jews in a fictional or stereotypical manner; the great majority of narrative religious Medieval art depicted events from the Bible, where the majority of persons shown had been Jewish. But the extent to which this was emphasized in their depictions varied greatly. Some of this art was based on preconceived notions about how Jews dressed or looked, as well as the "sinning" acts which Christians believed that they committed.[27] Visual art in particular expressed these ideas with a clear polemic edge. On the Westlettner of the Naumberg Cathedral, 13 of the 31 figures featured on the original set of reliefs are Jewish, clearly demarcated as such by their Jewish hats. As with much other medieval art of the Jews,[28][full citation needed] many of the 13 are depicted as in some way being complicit or directly aiding the Crucifixion of Christ, furthering the charge of Jewish deicide. With that in mind, however, some scholars argue that Naumberg's reliefs are unusually not anti-Jewish for their time period in their portrayal of the Jews, as not all of them are sculpted as unambiguously evil or malicious.[29] Comparing that to the caricatures in the west facade of the abbey church of St-Gilles-du-Gard, Naumberg's images do seem relatively tame. Here, Jews are displayed in some of the most typical anti-Jewish iconography of the time, with protruding jaws and hooked noses. Their haggardly, poor appearance is contrasted with the non-Jews of the image, including Roman guards, who are presented with a degree of fashion and status through their capes and typical tunics and similar attire.[29] Another iconic symbol of this era was Ecclesia and Synagoga, a pair of statues personifying the Christian Church (Ecclesia) next to her predecessor, the Nation of Israel (synagoga). The latter was often displayed blindfolded and carrying a tablet of the law sliping from her hand, sometimes also bearing a broken staff, whereas Ecclesia was standing upright with a crowned head, a chalice and a staff adorned with the cross.[30] This was often as a result of a misinterpretation of the Christian doctrine of Supersessionism involving a replacement of the "old" covenant given to Moses by the "new" covenant of Christ, which medieval Christians took to mean that the Jews had fallen out of God's favour.[citation needed]

Jews as enemies of Christians

[edit]Medieval Christians believed in the idea of Jewish "stubbornness", which correlated to many characteristics of the Jewish people. Specifically, Jews did not believe that Christ was the Messiah, a savior. This idea contributed to the stereotype that Jews were stubborn but also extended further in that the Jews dismissed Christ so far that they decided to murder him by nailing him to a cross. Jews were, therefore, marked as the "enemies of Christians" and "Christ-killers."[27]

The notion behind Jews as Christ-killers was one of the main inspirations behind antisemitic portrayals of Jews in Christian art. For example, in one piece, a Jew is placed in between the pages of a Bible[clarify], while sacrificing a lamb with a knife. The lamb is meant to represent Christ, which serves to reveal how Christ died at the hands of the Jewish people.[citation needed]

Jews as devil-like

[edit]Further, according to Medieval Christians, anyone who did not agree with their ideas of faith, including the Jewish people, were automatically assumed to be friendly with the devil and simultaneously condemned to hell. Therefore, in many portrayals of Christian art, Jews are made out to resemble demons or interact with the devil. This is meant to not only portray Jews as ugly, evil, and grotesque but also to establish that demons and Jews are innately similar. Jews would also be placed in front of hell to further showcase that they are damned.[27]

Stereotypical Jewish appearances

[edit]By the twelfth century, the concept of a "stereotypical Jew" was widely known. A stereotypical Jew was usually a male with a heavy beard, a hat, and a large, crooked nose, all of which were significant identifiers for someone who was Jewish. These notions were portrayed in medieval art, which ultimately ensured that a Jew could easily be identified. The idea behind a stereotypical Jew was to primarily portray a Jew as an ugly creature which is to be avoided and feared.[27]

See also

[edit]- Antisemitism

- Geography of antisemitism

- History of antisemitism

- Antisemitism in Europe

- Antisemitism in Christianity

- Christianity and Judaism

- History of the Jews in Europe

- Antisemitism in the Arab world

- Antisemitism in Islam

- History of the Jews under Muslim rule

- Islamic–Jewish relations

- Relations between Nazi Germany and the Arab world

- Jacob Barnet affair

- Jewish history

- History of the Jews in the Middle Ages

- Relations between Eastern Orthodoxy and Judaism

- Catholic Church and Judaism

- Religious antisemitism

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 287-289 The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Anti-Semitism In Medieval Europe Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Paley, Susan and Koesters, Adrian Gibbons, eds. "A Viewer's Guide to Contemporary Passion Plays" Archived March 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 12, 2006.

- ^ Yuval-Naeh, Avinoam (7 December 2017). "England, Usury and the Jews in the Mid-Seventeenth Century". Journal of Early Modern History. 21 (6): 489–515. doi:10.1163/15700658-12342542. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Religious Discrimination, Berkman Center - Harvard Law School [dead link]

- ^ a b See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire ("The greatest epidemics in history"), in L'Histoire magazine, n°310, June 2006, p.47 (in French)

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 421. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Hertzberg, Arthur and Hirt-Manheimer, Aron. Jews: The Essence and Character of a People, HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, p.84. ISBN 0-06-063834-6

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 420. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Lindsey, Hal (1990). The Road to Holocaust. Random House. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-553-34899-6.

- ^ Bennett, Gillian (2005), "Towards a revaluation of the legend of 'Saint' William of Norwich and its place in the blood libel legend". Folklore, 116(2), pp 119–121.

- ^ Ben-Sasson, H.H., Editor; (1969). A History of The Jewish People. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-674-39731-2 (paper).

- ^ a b c d Teter, Magda. "The Death of Little Simon and the Trial of Jews in Trent." In Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth, 43-88. N.p.: Harvard University Press, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvt1sj9x.8.

- ^ "Gregory X: Letter about Jews against the Blood Libel". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-10-26.

- ^ Feigenbaum, Gail (2018-03-06). Getty Research Journal, No. 10. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-60606-571-6.

- ^ Nirenberg, David. Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition.

- ^ Chazan, Robert (2010). Reassessing Jewish Life in Medieval Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 252.

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 160. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Michael Costen, The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, p 38

- ^ Anti-Semitism. Jerusalem: Keter Books. 1974. ISBN 9780706513271.

- ^ "Map of Jewish expulsions and resettlement areas in Europe". Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida. A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Wood, Christopher S., Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, p. 251, 1993, Reaktion Books, London, ISBN 0948462469

- ^ David Nirenberg. "Anti-Judaism", W.W. Norton & Company, 2013, p.262. ISBN 978-0-393-34791-3

- ^ Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews, HarperCollins Publishers, 1987, p.242. ISBN 5-551-76858-9

- ^ Luther, Martin. D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesamtausgabe, Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1920, Vol. 51, p. 195.

- ^ Glazer-Eytan, Yonatan (2019). "Jews Imagined and Real: Representing and Prosecuting Host Profanation in Late Medieval Aragon". In Franco Llopis, Borja; Urquízar-Herrera, Antonio (eds.). Jews and Muslims Made Visible in Christian Iberia and Beyond, 14th to 18th Centuries. Leiden: Brill. p. 46; 67. ISBN 978-90-04-39016-4.

- ^ a b c d Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003). Saracens, Demons, and Jews: making monsters in Medieval art. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Pontius Pilate, anti-Semitism, and the Passion in medieval art. 2009-12-01.

- ^ a b Merback, Mitchell (2008). Beyond the Yellow Badge Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture. ISBN 978-90-04-15165-9. OCLC 923533086.

- ^ From Notre Dame to Prague, Europe’s anti-Semitism is literally carved in stone Jewish Telegraphic Agency, March 20, 2015

Medieval antisemitism

View on GrokipediaMedieval antisemitism denotes the pervasive prejudice, legal discrimination, and outbreaks of violence against Jewish populations in Christian-dominated Europe from roughly the fifth to the fifteenth centuries, fundamentally propelled by ecclesiastical doctrines imputing collective guilt to Jews for the crucifixion of Jesus, which framed them as perpetual adversaries to Christianity.[1] This theological foundation, articulated by patristic writers and amplified through medieval sermons and canon law, fostered a worldview in which Jews were viewed not merely as religious dissenters but as existential threats warranting isolation and periodic eradication.[2] Compounding these religious animosities were socioeconomic tensions arising from Jews' restricted occupational niches, particularly moneylending, which Christians were barred from practicing under usury prohibitions, breeding debtor resentment that erupted into pogroms during economic downturns or crises like the Black Death of 1348–1351, when Jews were falsely accused of well-poisoning and massacred across German and French territories.[3] Empirical analysis of these plague-era pogroms reveals their enduring cultural legacy, as regions with historical anti-Jewish violence exhibited heightened antisemitic incidents and political support for exclusionary movements centuries later, underscoring causes rooted in persistent societal attitudes rather than transient material conflicts.[4] Fabricated charges of ritual murder (blood libel) and host desecration, originating in the twelfth century, further incited mob violence and judicial executions, while ecclesiastical councils such as the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 mandated distinctive clothing and residential segregation to prevent social mingling.[5] Mass expulsions marked the era's culmination, with Jews evicted from England in 1290, France repeatedly in the fourteenth century, and numerous German principalities, often justified by rulers seizing assets to alleviate fiscal pressures amid feudal indebtedness.[6] These events, intertwined with crusading zeal—exemplified by the Rhineland massacres of 1096—highlighted how religious fervor and pragmatic opportunism converged to marginalize and displace Jewish communities, setting precedents for later European exclusions.[3] Despite scholarly debates over terminology, distinguishing medieval "anti-Judaism" from modern racial antisemitism, the period's patterns of demonization and scapegoating demonstrate a causal continuum driven by doctrinal hostility and crisis exploitation, unmitigated by empirical refutation of prevalent myths.[7]

Theological and Religious Foundations

Deicide Accusations and Christian Doctrine

The deicide accusation charged the Jewish people with collective responsibility for the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, construed as the murder of God in human form. This theological motif drew primary support from New Testament texts, notably Matthew 27:25, wherein a Jewish crowd invokes perpetual blood guilt upon itself and its descendants during the trial before Pontius Pilate.[8] Early patristic writers, such as John Chrysostom in his Adversus Judaeos homilies delivered in Antioch around 386–387 AD, intensified the charge by depicting Jews as ongoing adversaries of God, inherently stained by their ancestors' role in the Passion.[9] In medieval Latin Christian doctrine, the accusation evolved within a framework balancing Jewish culpability with pragmatic toleration. Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD), in works like De civitate Dei (c. 413–426 AD), maintained that Jews acted from blindness to Christ's divinity rather than full knowledge, rendering them participants in a divine plan that necessitated the Passion for salvation; their post-crucifixion dispersion served as ongoing punishment for deicide, yet they were to be preserved as "witnesses" bearing the Hebrew Scriptures that authenticated Christian claims.[10] [8] This witness doctrine, echoed in canon law and papal bulls like Pope Innocent III's Sicud Judaeis (1199), justified Jewish subservience—barring them from sovereignty or public office—while prohibiting mass conversion by force or extermination, as their survival testified to scriptural truth.[11] By the High Middle Ages, scholastic theologians hardened the deicide imputation toward willful malice. Peter Lombard (c. 1096–1160), in his Sentences (c. 1150), posited that Jewish leaders possessed partial messianic knowledge of Christ but crucified Him from envy, extending guilt beyond ignorance.[8] Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), building on this in Summa theologiae (1265–1274), contended that rabbinic authorities could have discerned Christ's identity via prophecies but rejected Him maliciously, affirming deicide as a deliberate rejection of divine revelation.[8] Dominican and Franciscan friars, active from the 13th century, further polemized this view in missionary disputations and texts like Raymundus Martini's Pugio fidei (c. 1270), portraying Jews not merely as blinded witnesses but as persistent threats through alleged Talmudic blasphemies against Christ, thus eroding Augustinian restraint.[8] The doctrine permeated medieval Christian practice, embedding deicide in liturgical elements like the Good Friday prayer for the "perfidious Jews"—unbelievers perfidiously rejecting salvation through Christ's blood—recited annually from at least the 7th century onward, which framed Jewish dispersion as providential chastisement.[12] This reinforced supersessionist theology, wherein the Church supplanted Israel as God's elect, and rationalized discriminatory policies by positing eternal Jewish guilt as causal to their marginalized status, though doctrinal nuance on culpability varied and did not universally endorse violence.[8]Demonization of Jews in Sermons and Theology

In medieval Christian theology, Jews were increasingly portrayed as obstinately blind to divine truth, cursed for their collective rejection of Christ, and susceptible to demonic influence, themes that permeated doctrinal treatises and sermons alike. This depiction built on earlier patristic traditions but gained intensity amid the Crusades and socio-economic tensions of the 11th–13th centuries, framing Judaism not merely as obsolete but as a malevolent force opposing Christian salvation. Theologians argued that Jews' adherence to literal interpretations of scripture demonstrated carnality and spiritual deformity, contrasting with Christian allegorical exegesis, thereby justifying their marginalization as witnesses to Christianity's triumph yet perpetual adversaries.[13][14] Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny (c. 1090–1156), exemplified this theological hostility in his treatise Adversus Iudaeos (c. 1144–1146), where he lambasted Jews for their "inveterate obduracy" and accused them of defiling Christian sacraments through ritual impurity, equating their stubbornness to a bestial rejection of reason. In a 1146 letter to King Louis VII of France, Peter further demonized Jews as a "pestilence" infecting society, urging their subjugation while stopping short of extermination, a stance that nonetheless reinforced views of Jews as inherently corrupting. His rhetoric, drawing on visceral imagery of Jewish "filth" and devilish alliance, influenced subsequent polemics and sermons that depicted Jews as subhuman obstacles to Christ's body.[15][16] Sermons, delivered in cathedrals and during liturgical seasons like Holy Week, amplified these theological motifs, often invoking Jews as contemporary perpetrators of deicide through alleged mockery of the Eucharist or synagogue practices. Guibert of Nogent (c. 1053–1124), in his crusade chronicle Dei gesta per Francos (c. 1108), derided Jews—including biblical figures like the Maccabees—as perfidious enemies whose traditions blinded them to Christian revelation, portraying their persistence as a demonic thwarting of God's plan. Preachers such as these integrated such narratives into homilies, fostering popular perceptions of Jews as devil's agents, a trope that by the 12th century merged with apocalyptic fears of Jewish "redemption" only at Judgment Day.[17][18] Not all theologians endorsed outright violence, as seen in Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), who in 1146–1147 sermons during the Second Crusade condemned mob attacks on Jews, citing Romans 11:18–20 to argue their preservation as "branches" grafted back at the end times, yet he simultaneously decried Jewish "exclusiveness" and spiritual blindness as barriers to conversion. Despite such restraint, Bernard's views upheld Jews' theological inferiority, aligning with a broader sermonic tradition that demonized them as cursed wanderers embodying divine retribution. This dual approach—doctrinal condemnation paired with conditional toleration—underscored the era's causal link between theological demonization and escalating social hostility, evident in rising accusations of Jewish sorcery by the 13th century.[19][20] By the later Middle Ages, these elements coalesced in works like those of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), who in Summa Theologica (c. 1265–1274) affirmed Jews' perpetual servitude as punishment for deicide, barring them from dominion over Christians while permitting their economic exploitation, a position echoed in sermons that portrayed Jewish usury as satanic exploitation. Such theological framing, disseminated through university disputations and pulpit oratory, systematically eroded empathy, priming audiences for crises where Jews were scapegoated as infernal conspirators. Empirical records of sermon collections, such as those from 13th-century mendicant orders, reveal recurrent motifs of Jewish "demonic partnership," correlating with spikes in ritual murder libels from 1144 onward.[21][22]Socio-Economic Dimensions

Restrictions on Land Ownership and Guilds

In medieval Europe, particularly from the late 12th century onward, Jews faced widespread prohibitions on land ownership, which barred them from agricultural pursuits and feudal landholding. These restrictions stemmed from canon law and secular policies that viewed Jewish land tenure as incompatible with Christian feudal structures, often treating Jews as royal wards rather than vassals entitled to fiefs. For instance, in England under Henry III, a 1271 ordinance explicitly banned Jews from holding freehold land, reinforcing earlier customs that limited them to urban movable property. Similar edicts appeared in France and the Holy Roman Empire, where rural land ownership was curtailed to prevent Jews from accumulating hereditary estates that could rival Christian nobility or evade ecclesiastical tithes.[23][24] By the late Middle Ages, such bans extended across many regions, confining Jews to cities and portable assets like cash or goods, a policy that economic historians attribute to both religious exclusion and efforts to channel Jewish activity into finance.[23] Exclusion from craft guilds compounded these limitations, as guilds—predominantly Christian associations formed from the 11th century—monopolized skilled trades such as blacksmithing, weaving, and masonry through apprenticeships, oaths, and membership statutes that required adherence to Christian rites. Jews were systematically denied entry, with guild charters often stipulating Christian faith as a prerequisite; in Ashkenazi communities, where crafts were otherwise viable, this barred participation in regulated urban economies. Primary guild records from cities like Cologne and Paris reflect this, showing no Jewish members amid rising guild dominance in the 13th century, which reduced Jewish occupational options to unregulated sectors like peddling and brokerage.[25] While some Jewish artisans operated informally or in Jewish-only groups in places like Spain before 1492, these were marginal and lacked the legal protections afforded to Christian guilds, perpetuating economic marginalization. These intertwined restrictions—on land for agrarian self-sufficiency and guilds for artisanal production—fostered a socioeconomic niche in commerce and moneylending, as Jews could not compete in land-based or guild-protected fields. Historians note that while early medieval Jews (pre-1000 CE) often held rural land voluntarily shifting to urban roles due to literacy advantages, later prohibitions rigidified this pattern, exacerbating resentments over perceived Jewish economic advantages in permitted areas. Enforcement varied by ruler—tolerant princes like Frederick II occasionally waived bans—but overall, they reflected causal Christian policies to segregate Jews economically, limiting assimilation and fueling stereotypes of parasitism despite Jews' contributions to trade networks.[23][26]Moneylending, Usury, and Resulting Resentments

In medieval Europe, the Catholic Church's longstanding prohibition on usury—defined as charging interest on loans—created a structural vacuum in credit provision among Christians, as canon law from the Third Lateran Council in 1179 and subsequent decrees strictly forbade it between Christians.[27] Jewish law, drawing from Deuteronomy 23:20, permitted lending at interest to non-Jews while prohibiting it among Jews, allowing Jewish communities to supply credit to Christian borrowers and rulers seeking funds for wars or infrastructure.[28] This role was amplified by discriminatory restrictions: Jews were often barred from owning land, joining craft guilds, or farming in Christian domains, funneling them into portable trades like commerce and finance, where literacy rates—fostered by religious study—provided an advantage in record-keeping and contracts.[29][27] Jewish moneylending operated under royal oversight in places like England, where the Exchequer of the Jews, established around 1190, recorded loans, enforced repayments, and levied taxes on Jewish lenders, with the Crown claiming a share of profits to fund its treasury.[29] Interest rates were regulated variably; papal bulls in the 13th century, such as those under Innocent III, capped Jewish usury at roughly two pence per pound per week (equivalent to about 43% annually) and banned using church goods as pledges, though enforcement was inconsistent and rates often reflected high risks from defaults or pogroms.[30] Contrary to stereotypes, only a minority of Jews—typically an urban elite—specialized in large-scale lending to nobility or municipalities; most Jews engaged in petty trade, artisanry, or small loans, with estimates suggesting fewer than 10% of England's 3,000 Jews around 1200 were significant usurers.[31][32] Economic resentments intensified as borrowers—nobles, clergy, and peasants—faced repayment pressures during famines, wars, or recessions, fostering perceptions of Jews as exploitative outsiders profiting from Christian hardship.[33] Debtors' hostility manifested in riots targeting lenders' homes and synagogues, as seen in 1263 London, where debts to Jewish financiers fueled mob violence amid baronial revolts against royal taxation.[29] Rulers exploited these sentiments for political gain; Edward I's 1290 Edict of Expulsion from England canceled all Jewish-held debts (estimated at £100,000, a massive sum) in exchange for parliamentary taxes, relieving indebted landowners while confiscating Jewish assets.[34] Similar dynamics appeared in France, where Philip IV's 1306 expulsion seized Jewish loans to fund campaigns, blending fiscal opportunism with popular anti-usury agitation.[35] Theological critiques amplified lay resentments, with canonists like Alessandro Nievo in 15th-century Italy arguing Jewish lending endangered Christian souls by tempting usury, urging bans despite pragmatic tolerance by popes reliant on Jewish credit for Crusades.[36] This convergence of debtor grievances and doctrinal disdain entrenched tropes of Jewish avarice in literature and sermons, portraying lenders as "broods of vipers" preying on the faithful, though empirical records show Jewish loans enabled economic activity like cathedral construction and trade expansion that benefited borrowers long-term.[37] By the late Middle Ages, as Christian bankers like the Lombards filled the usury niche, Jewish lenders faced expulsion waves, underscoring how initial necessities bred enduring animosities.[35]Legal and Social Restrictions

Sumptuary Laws and Identifying Clothing

The Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 decreed in Canon 68 that Jews and Saracens in Christian provinces must wear clothing distinguishing them from Christians, aiming to prevent inadvertent social or sexual intermingling by ensuring their visibility.[38] This measure built on earlier Islamic precedents but marked the first ecumenical endorsement in Western Christendom, reflecting theological concerns over ritual purity and de facto segregation.[39] Enforcement varied by region, often tied to papal legates or local rulers, with the badge or garment serving both identificatory and stigmatizing functions amid rising socioeconomic tensions.[40] In England, papal legates Pandulf and Guala enforced the council's directives during the early 13th century, mandating a tabula—a badge resembling the Tablets of the Law—worn by Jews over age seven on their outer garments above the heart, typically yellow taffeta measuring six fingers long and three broad.[41] The 1275 Statute of the Jewry under Edward I formalized this requirement, specifying a yellow badge shaped as "two Tables joined," reinforcing identification to curb alleged usury and ritual crimes while facilitating royal taxation of Jewish communities.[42] Compliance was inconsistent, as exemptions were sometimes granted for payments, underscoring the laws' role in extortion alongside discrimination.[43] Across the Holy Roman Empire, the Judenhut—a tall, conical yellow hat—emerged as a common marker, decreed in locales like Breslau by 1266 and Rome under severe penalties, symbolizing otherness through its association with stereotypes of heresy or infernal imagery.[44] This headwear, distinct from badges, heightened visibility in public spaces, exacerbating social isolation and vulnerability to pogroms, as seen during the Rintfleisch massacres of 1298 where identifiable Jews were targeted en masse.[45] In France, Louis IX's 1254 ordinance required Jews to affix a yellow circle or rouelle to their clothing, echoing the Lateran badge while prohibiting luxurious attire to underscore subservient status.[46] Such edicts, sporadically reapplied amid expulsions, intertwined with broader sumptuary restrictions limiting Jewish dress to coarse fabrics, ostensibly to prevent ostentation but practically to affirm Christian dominance and mitigate resentments over moneylending prosperity.[47] Overall, these mandates formalized medieval antisemitism's visual grammar, enabling casual harassment and justifying violence by rendering Jews perpetually conspicuous outsiders.[43]Residential Segregation and Ghetto Precursors

In the Holy Roman Empire, the earliest documented example of a designated Jewish quarter emerged in Speyer in 1084, when Bishop Rüdiger Huzmann resettled Jews fleeing pogroms in Mainz and Worms into a protected area outside the city walls near the cathedral, granting them privileges to attract settlement and boost the city's prestige while ensuring separation from the Christian populace.[48] [49] This arrangement provided physical security amid rising violence but also enabled ecclesiastical and secular oversight, marking an initial blend of protection and isolation that characterized early medieval precedents to later ghettos. Similar quarters soon appeared in nearby ShUM cities—Speyer, Worms, and Mainz—forming interconnected Jewish communities by the late 11th century, where residence was tied to communal institutions like synagogues and mikvehs.[48] Ecclesiastical policy accelerated compulsory segregation across Europe. The Third Lateran Council of 1179 and the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 decreed measures to distinguish Jews from Christians, including distinctive clothing and prohibitions on shared dwellings to avert "undue familiarity" that might lead to Christian apostasy or moral contamination, as articulated in canon 68 of the 1215 council.[50] [51] These canons, while not always mandating locked enclosures, pressured secular rulers to confine Jews to specific urban zones, often narrow alleys or peripheral streets, for easier taxation, surveillance, and containment of perceived threats during crusades or economic unrest. In practice, such quarters housed hundreds in cramped conditions; for instance, Trier's medieval Judengasse, established by 1235, accommodated around 300 Jews in densely built houses forming an eruv for Sabbath observance.[52] Regional variations highlighted evolving restrictions. In Iberia, juderías like Girona's call (Jewish quarter) were organized by 1160 as semi-autonomous enclaves under royal protection, yet walled for defense against mobs, with Jews barred from residing elsewhere after the 13th century amid Reconquista tensions.[53] In England, Jews clustered in the London Jewry along streets like Old Jewry from the late 12th century, with the 1275 Statute of the Jewry formalizing limits on property ownership and movement, confining them to royal wards for fiscal exploitation.[54] German lands saw stricter precursors, such as Prague's community by 1262 and Frankfurt's Judengasse in 1462, where Emperor Frederick III mandated all Jews live along a single enclosed lane to curb "disorder" and usury complaints, foreshadowing the locked, curfewed ghettos of the 16th century.[50] These arrangements, initially partly voluntary for communal cohesion, increasingly became enforced isolation, fostering overcrowding—e.g., multi-family dwellings in Speyer's quarter—and vulnerability to fires or sieges, while reinforcing economic roles in moneylending within bounded spaces.[55]Civic and Political Disabilities

In medieval Europe, Jews were systematically barred from holding public offices, particularly those entailing authority over Christians, as codified in canon law. The Fourth Lateran Council of 1215 explicitly prohibited Jews from exercising such power, deeming it "too absurd" for those who rejected Christ to govern believers, and renewed prior ecclesiastical decrees to enforce this exclusion.[39] This canon influenced secular rulers across regions like England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire, where Jews were denied magistracies, judicial roles, and administrative positions; for instance, in 1222, the English Council of Oxford echoed the prohibition, limiting Jewish influence in governance.[38] Enforcement varied but typically resulted in Jews lacking representation in municipal councils or royal courts, reinforcing their status as royal wards rather than full subjects with political agency. Jews also faced exclusion from military service and citizenship privileges, further curtailing civic participation. In most polities, they were prohibited from bearing arms or enlisting in armies, except occasionally in royal retinues for specific duties like tax collection, due to distrust and religious incompatibilities such as Sabbath observance.[56] This barred them from the honors and protections of soldiery, while special levies like the tallage in England substituted for feudal obligations, treating Jews as perpetual outsiders without the rights of burghers or nobles.[57] Lacking municipal citizenship, Jews could not vote in assemblies, serve on juries involving Christians, or testify reliably in mixed courts, as their oaths were often deemed suspect under canon law precedents like Gratian's Decretum, which prioritized Christian testimony.[58] These disabilities stemmed from a legal framework viewing Jews as tolerated but subordinate, protected by charters (e.g., Emperor Frederick I's 1152 privileges granting safety but no political equality) yet liable to revocation during crises.[59] In practice, they confined Jews to economic niches under royal oversight, with violations punished by fines or expulsion threats, as seen in 13th-century Sicilian statutes revoking Jewish tax-farming roles after complaints of overreach.[60] Such measures, while not uniform, persisted until early modern emancipations, limiting Jewish integration into the body politic.Pivotal Crises and Violence

Rhineland Massacres During the Crusades

The Rhineland massacres of 1096 occurred during the prelude to the First Crusade, as unstructured popular crusading bands, inflamed by religious zeal, targeted Jewish communities in German cities along the Rhine River. These attacks, often termed the "German Crusade," were not directed by papal authorities but arose from local preachers and self-proclaimed leaders who portrayed Jews as immediate enemies of Christ, extending the crusade's logic of holy war against non-Christians to Europe's Jewish populations.[61] Primary Hebrew chronicles, such as that of Solomon bar Simson, record the events as driven by crusader demands for conversion or death, rooted in longstanding Christian accusations of deicide.[62] The violence began in Speyer on April 26, 1096, where Bishop Johannes intervened effectively, limiting deaths to approximately 11 Jews despite crusader assaults on the community. In Worms, from May 18 to 20, mobs killed an estimated 800 to 1,000 Jews, overwhelming initial protections; many victims were slaughtered in their homes or the bishop's palace after refusing baptism. Mainz suffered the deadliest assault on May 27–29, led by Count Emicho of Flonheim, resulting in 900 to 1,100 deaths despite bribes paid to Bishop Ruthard for safeguarding; chroniclers describe crusaders breaking into fortified spaces and massacring families.[63] Further attempts in cities like Trier and Metz saw additional killings, with overall estimates for Rhineland victims ranging from 2,000 to 5,000, devastating prosperous Jewish centers.[64] Jewish responses emphasized martyrdom over apostasy, with communal leaders organizing suicides and killings of dependents to evade forced conversion, as detailed in accounts like Solomon bar Simson's, which frame the events as a test of faith akin to biblical persecutions. Local Christian burghers often joined crusaders for plunder and debt relief, exacerbating the carnage, though some ecclesiastical figures condemned the acts post-facto. Emicho's band, claiming divine visions, failed to reach Jerusalem and dispersed after defeats, but the massacres marked a shift toward organized anti-Jewish violence in Europe, independent of crusade successes.[61][63]Black Death Persecutions and Well-Poisoning Claims

During the Black Death pandemic of 1347–1351, which killed an estimated 30–60% of Europe's population, Jews faced intensified accusations of deliberately poisoning wells and water sources to spread the plague among Christians.[65] These claims emerged in early 1348 in Savoy and the Swiss Confederation, where torture extracted confessions from Jews alleging a coordinated plot originating from Toledo, Spain, involving poisoned well water.[24] No verifiable evidence of such poisoning has been found by historians; instead, the accusations aligned with patterns of scapegoating minorities during crises, amplified by existing religious prejudices and economic tensions, as Jews' relatively lower mortality rates—possibly due to stricter hygiene and quarantine practices rooted in religious law—fueled suspicions.[66] [67] The libel spread rapidly through German-speaking regions of the Holy Roman Empire, inciting massacres that destroyed numerous Jewish communities. In Basel, on January 9, 1349, council authorities ignored papal protections and burned 300 to 600 Jews on a wooden pyre erected on an island in the Rhine River, while others had been drowned earlier in the river.[68] In Strasbourg, on February 14, 1349—St. Valentine's Day—the guild masters and mob overrode the bishop's safeguards, herding approximately 2,000 Jews into the Jewish cemetery and burning them alive in a massive wooden structure, effectively annihilating the local community.[69] Similar pogroms occurred in Freiburg, Erfurt, and Mainz, with thousands killed overall; in some cases, like Mainz, up to 3,000 perished amid flagellant-led violence.[65] Pope Clement VI attempted to counter the hysteria with two papal bulls issued from Avignon: one on July 6, 1348, reaffirming protections under Sicut Iudaeis and attributing the plague to natural astronomical conjunctions rather than Jewish malice, and another on September 26, 1348 (Quamvis Perfidiam), explicitly exonerating Jews by noting their own deaths from the disease and condemning forced baptisms and killings.[70] Despite these interventions, local authorities and mobs often disregarded them, as secular powers prioritized public unrest over ecclesiastical decrees; the persecutions wiped out over 200 Jewish communities, particularly in Switzerland and the Rhineland, though some areas like Cologne and Nuremberg temporarily shielded residents.[24] Historians attribute the well-poisoning narrative's persistence to a combination of causal factors: the plague's inexplicable origins, Christians' cancellation of debts to Jewish lenders via murder, and the ritualistic nature of prior antisemitic tropes like blood libel, rather than any factual basis.[66] Confessions uniformly derived from torture, with no independent corroboration, and post-plague investigations, such as those ordered by Emperor Charles IV, confirmed the accusations' falsity while failing to halt the violence.[67] These events marked a peak in medieval pogroms, reducing Jewish populations in affected regions by up to 50% beyond plague losses alone, and entrenched the well-poisoning motif in European folklore as a recurring antisemitic canard.[65]Expulsions from England, France, and Iberia

In England, King Edward I issued the Edict of Expulsion on July 18, 1290, ordering all Jews to leave the kingdom by All Saints' Day (November 1), with an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 individuals affected.[71] The decree followed centuries of restrictions on Jewish economic roles, confining them primarily to moneylending, which generated royal revenues through taxation and tallages but also fueled popular resentment over usury. Edward's decision was driven by financial exigency amid war debts from campaigns in Wales and Gascony; in exchange for parliamentary grants totaling £116,000, he agreed to expel the Jews, allowing the crown to seize their assets and cancel debts owed to them by Christian borrowers. [71] Enforcement was swift, with Jews escorted to ports under royal protection to prevent pogroms, though many faced robbery en route; the expulsion marked the end of organized Jewish life in England until the 1650s.[71] France experienced repeated expulsions, reflecting cyclical royal exploitation of Jewish communities for fiscal gain under religious pretexts. Philip II Augustus ordered the first major expulsion in 1182, confiscating Jewish property and debts to fund administrative reforms, though Jews were readmitted in 1198 for their economic utility.[72] The most notorious occurred under Philip IV (the Fair) on April 22, 1306, when approximately 100,000 Jews were arrested without prior edict, their possessions seized to alleviate the king's monetary crisis from military expenditures and currency debasement.[73] [72] Philip declared himself creditor of all Jewish loans, auctioning off synagogues and homes at undervalued prices while permitting departure with minimal assets by Shrove Tuesday; this act eliminated a key revenue source but temporarily stabilized royal finances.[73] Subsequent readmissions under Louis X in 1315 were short-lived, with further expulsions in 1322 and 1394 under Charles VI, the latter permanent until the Revolution, as kings alternated between extraction and banishment amid accusations of ritual crimes and usury.[72] [74] In Iberia, expulsions culminated in the late 15th century amid the Reconquista's push for religious homogeneity, though earlier pogroms like those of 1391 had already prompted mass conversions. The pivotal Alhambra Decree of March 31, 1492, issued by Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, mandated the departure of all practicing Jews by July 31, affecting an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 individuals who refused baptism.[75] The edict cited the need to prevent Jewish "influence" over conversos (forced converts), whom authorities suspected of crypto-Judaism, exacerbated by Inquisition reports of backsliding; economic factors included resentment over Jewish roles in finance and trade, with seizure of abandoned property funding royal endeavors.[76] [77] Influenced by confessor Tomás de Torquemada, the decree framed expulsion as a divine imperative for Christian unity post-Granada conquest, leading to dispersal to Portugal, North Africa, and Italy, where many faced further perils.[75] Portugal's Manuel I decreed expulsion in 1497 but opted for forced conversion, effectively absorbing Iberian Jewry into converso status while banning emigration.[76] These events, while justified religiously, enabled debt cancellations and asset appropriations, underscoring rulers' pragmatic use of antisemitic theology to consolidate power and resources.[77]Ritual Crime Allegations

Blood Libel Origins and Spread

The blood libel accusation, alleging that Jews ritually murdered Christian children to obtain blood for religious purposes such as Passover matzah, originated in medieval Europe with the unexplained death of a boy named William in Norwich, England, on March 25, 1144. William's body was discovered in a wooded area called Mousehold Heath, bearing wounds that locals interpreted as crucifixion marks, fueling rumors among the Christian population that Norwich's Jewish community had killed him in mockery of Christ's Passion and to collect his blood for ritual use.[78] [79] No contemporary evidence linked Jews to the crime, and royal intervention prevented immediate arrests, but the story gained traction through the writings of the Benedictine monk Thomas of Monmouth, who around 1150 began composing The Life and Passion of St. William the Martyr, a hagiographic account portraying William as a saintly victim of Jewish ritual murder based on coerced confessions and fabricated testimonies.[80] This narrative established William's cult as a pilgrimage site, embedding the libel in local devotion and providing a template for future accusations that combined antisemitic stereotypes of Jewish cruelty with Eucharistic miracle motifs.[81] The libel spread initially within England, where economic resentments against Jewish moneylenders and heightened religious fervor from the Second Crusade amplified suspicions. In 1168, similar charges surfaced in Gloucester, claiming Jews had abducted and killed a boy named Harold for blood; this was followed in 1181 by the case in Bury St. Edmunds, where 57 Jews were reportedly imprisoned and many tortured or killed after accusations of murdering a boy named Robert.[78] By 1190, amid anti-Jewish riots preceding the Third Crusade, blood libel contributed to the massacre of around 150 Jews in York, though not directly tied to a child murder there.[79] These English cases disseminated via monastic chronicles, saints' vitae, and oral traditions among pilgrims and clergy, framing Jews as inherent enemies of Christianity.[82] Transmission to continental Europe occurred through cross-Channel contacts, crusading networks, and clerical exchanges, with the first major case outside England in Blois, France, in 1171, where 31–40 Jews were burned at the stake on May 26 after false claims of crucifying a Christian child and draining his blood, despite no body being found.[83] The accusation proliferated in the Holy Roman Empire during the 13th century, as in Fulda in 1235, where five Jews were executed for allegedly murdering five boys in a ritual, and Pforzheim in 1267, leading to burnings and expulsions.[79] Papal bulls, such as Innocent IV's Etsi Judaicos in 1247, occasionally condemned the libel as baseless and urged investigations, yet enforcement was inconsistent, and the motif persisted in popular piety, sermons, and art, often conflated with host desecration claims to justify pogroms during crises like the Rintfleisch massacres of 1298.[78] By the late 13th century, the libel had embedded in European folklore, recurring in over a dozen documented cases across Germany, France, and Switzerland, invariably lacking forensic evidence and relying on torture-extracted confessions.[80]Host Desecration Charges

Host desecration charges accused Jews of stealing consecrated Eucharistic hosts—believed under Catholic transubstantiation doctrine to embody Christ's literal body and blood—and subjecting them to ritual abuse, such as stabbing, boiling, or burning, purportedly to reenact or express hatred for the crucifixion.[84][85] These allegations emerged amid heightened Eucharistic devotion following the Fourth Lateran Council's 1215 affirmation of transubstantiation, which spurred miracle cults around bleeding or surviving hosts, often framed as Jewish assaults thwarted by divine intervention.[86] The earliest documented case occurred in 1243 at Belitz near Berlin, where Jews were accused of desecrating a host; all implicated individuals, including women, were burned at the stake, and the site became known as the "Jews' pyre."[87][86] Similar charges proliferated in the Holy Roman Empire and France, paralleling blood libel accusations as extensions of ritual murder tropes, with claims that desecrated hosts miraculously bled or spoke, inciting mobs and ecclesiastical trials.[88] In 1290 Paris, thirteen Jews were burned alive after torture-induced confessions of purchasing and stabbing hosts, leading to royal confiscations and further expulsions.[89] These fabrications, unsupported by contemporary Jewish evidence or independent verification, served as pretexts for pogroms and property seizures, reinforcing Jews' portrayal as existential threats to Christian sacraments; for instance, the 1370 Brussels incident saw dozens of Jews massacred after host-stabbing rumors, with the event commemorated in a perpetual shrine.[87][85] By the fifteenth century, such charges waned in Western Europe but persisted in Central Europe, culminating in events like the 1510 Berlin case, where 38 Jews were executed despite papal skepticism toward the libels.[89] Ecclesiastical authorities occasionally investigated claims rigorously, yet popular fervor and inquisitorial pressures often overrode evidentiary standards, embedding the motif in art and liturgy as moral warnings against Jewish perfidy.[84]Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Jews in Medieval Art as Enemies and Devils

Medieval Christian art frequently portrayed Jews with demonic attributes, including horns, tails, cloven hooves, and direct associations with devils, reinforcing their depiction as perennial enemies of Christ and allies of Satan.[90] This iconography emerged prominently from the 12th century onward, drawing on theological interpretations that viewed Jews as a "vessel of the devil" due to their refusal to convert and historical accusations of deicide.[91] Such representations served to visually distinguish Jews as morally corrupt and spiritually damned, often in manuscripts, sculptures, and frescoes across Western Europe. A key demonic trope was the attribution of horns to Jews, originating from the Latin Vulgate Bible's mistranslation of Exodus 34:29, where Moses' face "shone" (from Hebrew qaran) was rendered as "horned" after descending Sinai.[92] By the 13th century, this feature extended beyond Moses to Jews generally in art, symbolizing their stubbornness and infernal nature; for instance, a 1267 synod in Vienna mandated Jews wear pointed hats resembling horns to mark them visually.[92] In English and French illuminated manuscripts from the 1230s, such as the Psalter of Robert de Lisle, Jews appear in apocalyptic scenes with horned heads alongside demons.[93] Sculptural examples include the Judensau (Jew-sow) motifs, first appearing around 1230 in German-speaking regions, where Jews were carved suckling a sow or emerging from its anus, evoking bestial and satanic degradation.[94] Over 40 such reliefs survive from the 14th to 16th centuries, notably at Cologne Cathedral (c. 1300) and Regensburg Cathedral (c. 1320), blending porcine filth with demonic imagery to caricature Jews as subhuman servants of evil.[13] In Passion cycle frescoes, like those in 14th-century Italian churches, Jews tormenting Christ often bear tails or fangs, aligning them with hellish tormentors in Last Judgment panels.[14] These artistic conventions, while rooted in patristic writings equating Jews with the devil—such as John Chrysostom's 4th-century homilies calling them "intimate" with Satan—intensified amid 12th-13th century crusading fervor and economic tensions, embedding visual antisemitism in church decoration accessible to illiterate masses.[91] Scholarly analysis attributes their persistence to a deliberate monstrous code, akin to depictions of Saracens or heretics, which dehumanized outsiders to affirm Christian identity. Despite variations by region—more grotesque in Northern Europe than Italy—these images collectively propagated the notion of Jews as cosmic adversaries, influencing popular perceptions until the early modern era.[90]Stereotypical Depictions and Literary Tropes

In medieval European literature, Jews were recurrently depicted through tropes of demonic otherness, often merging theological accusations of deicide with folkloric imagery of devils, serpents, and beasts to portray them as inherently malevolent. This demonization, evident in homilies, chronicles, and narratives from the 12th century onward, attributed supernatural traits like horns or tails to Jews, symbolizing their supposed alliance with Satan and rejection of Christ. Such representations intensified during periods of social upheaval, as seen in English texts where Jews embodied existential threats to Christian piety and community.[95][13] A parallel stereotype fixed Jews as avaricious usurers, exploiting Christian debtors through moneylending—a role necessitated by ecclesiastical bans on usury for Christians, formalized at councils like Nicaea in 325 CE and reinforced by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, which confined Jews to financial occupations amid broader civic restrictions. Literary works amplified this into tropes of Jews as heartless creditors foreclosing on nobles or peasants, fueling narratives of economic predation that mirrored real resentments over debt but ignored the structural causes, such as guild exclusions barring Jews from crafts and landownership. In German and French vernacular tales, such as elements in the Roman de Renart adaptations, Jews appeared as cunning financiers hoarding wealth, their greed portrayed as a collective vice antithetical to Christian charity.[5][96] Prominent examples include Geoffrey Chaucer's The Prioress's Tale (c. 1390s), where Jews collectively murder a pious Christian boy for singing a Marian hymn, his throat slit in ritual malice before his body is miraculously discovered; this drew directly from blood libel legends like the 1255 case of Little Hugh of Lincoln, in which 18 Jews were executed amid claims of child crucifixion, a story disseminated in ballads and chronicles to evoke communal horror. Similarly, medieval bestiaries equated Jews with venomous creatures like the asp or basilisk, symbolizing deceit and poisoning of Christian society, a motif that bridged visual caricature and textual allegory to entrench fears of contamination. These tropes, while rooted in observable economic frictions, escalated into causal narratives blaming Jews for societal ills, from famine to moral decay, without empirical basis for the supernatural elements.[2][97][96] In Passion plays and mystery cycles, such as those performed in 14th-15th century England and Germany, Jews featured as archetypal villains in Christ's trial and crucifixion, shouting "Crucify him" with exaggerated ferocity, their roles scripted to elicit audience revulsion and reinforce stereotypes of inherent enmity. This theatrical persistence, documented in guild records from York and Chester cycles, causally linked literary vilification to public rituals, where actors donned stereotypical garb like pointed hats mandated by sumptuary laws (e.g., 1215 Lateran edicts), blurring depiction with lived enforcement. Scholarly analyses note how such portrayals, disseminated orally and in manuscripts, perpetuated a feedback loop of prejudice, though contemporary chroniclers like Matthew Paris (c. 1240s) occasionally critiqued excesses while upholding the core tropes.[98][99]Controversies in Historical Interpretation

Anti-Judaism vs. Modern Antisemitism Debate

Historians have long debated whether the hostility toward Jews in medieval Europe should be termed "antisemitism," implying a continuity with modern racial prejudices, or distinguished as "anti-Judaism," a primarily theological critique rooted in Christian doctrine.[100] Anti-Judaism, as defined by scholars like Gavin Langmuir, encompassed rational scriptural arguments against Jewish beliefs, such as the charge of deicide or supersessionism—the idea that Christianity had replaced Judaism as God's covenant—allowing for Jewish conversion as a path to redemption.[101] In contrast, modern antisemitism, a term coined by Wilhelm Marr in 1879 to describe secular, pseudoscientific racial hatred, viewed Jewishness as an immutable biological trait, irremediable by baptism and tied to conspiracy theories of global domination.[100] Proponents of the distinction, including Langmuir, argue that true antisemitism emerged only in the 12th century with irrational "chimeric" accusations, such as the blood libel alleging ritual murder of Christian children, which projected impossible traits onto Jews without empirical basis and marked a shift from theological polemic to prejudicial fantasy.[102] This view posits a causal break: medieval anti-Judaism drew on verifiable historical events like the crucifixion narrative, whereas modern variants secularized and racialized these into ahistorical myths, culminating in Nazi ideology's eliminationism, where over 6 million Jews were murdered between 1941 and 1945 not for religious error but purported racial inferiority.[101] Langmuir's framework, developed in works like Toward a Definition of Antisemitism (1990), emphasizes that pre-12th-century hostility lacked the delusional elements defining antisemitism, making anachronistic applications of the term to earlier periods misleading.[103] Critics of a sharp distinction, such as David Nirenberg, contend that anti-Judaism functioned not merely as religious critique but as a persistent Western intellectual tool for conceptualizing alterity, law, and social order, with medieval expressions laying groundwork for modern forms through enduring stereotypes of Jews as economic exploiters or cultural threats.[104] In Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (2013), Nirenberg traces this from ancient philosophers like Aristotle to medieval theologians and beyond, arguing that accusations of usury—rooted in medieval bans on Christian moneylending, leading to Jewish niche dominance and expulsions like England's in 1290—evolved into 19th-century tropes of Jewish financial control without a total rupture.[105] Similarly, Jeremy Cohen's Living Letters of the Law (1999) highlights a 12th-century theological escalation from Augustine's protective stance—Jews as "witness people" bearing scripture—to aggressive mandates for conversion or segregation, as in the Fourth Lateran Council's 1215 decrees requiring Jewish badges, which intensified physical and symbolic exclusion prefiguring ghettoization and pogroms.[106] The debate reflects broader historiographical tensions, including risks of anachronism when projecting 19th-century racial categories onto a era dominated by sacramental worldview, yet empirical evidence of recurring violence—such as the Rhineland massacres of 1096, killing thousands during the First Crusade—mirrors patterns in 1881 Russian pogroms or 1938 Kristallnacht, suggesting causal continuity in scapegoating amid crises like plagues or economic upheaval.[100] [107] Some scholars note institutional biases in academia, where minimizing medieval Christianity's role may stem from post-Holocaust sensitivities, underplaying how doctrines like the Adversus Judaeos tradition fueled both theological and visceral hatreds.[108] Ultimately, while forms differed—religious prejudice allowed limited integration via conversion, unlike racial fatalism—the medieval legacy of mythic demonization provided raw material for modern ideologies, as seen in the persistence of blood libel echoes in 20th-century forgeries like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (1903).[104]Economic vs. Religious Causality