Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

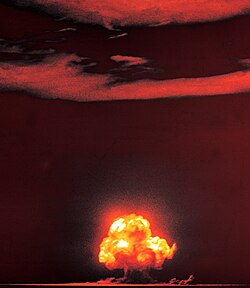

Nuclear weapons testing

View on Wikipedia

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

| Weapons of mass destruction |

|---|

|

| By type |

| By country |

|

| Non-state |

| Islamic State |

| Nuclear weapons by country |

| Proliferation |

| Treaties |

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of their explosion. Over 2,000 nuclear weapons tests have been carried out since 1945. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to signal strength. Because of their destruction and fallout, testing has seen opposition by civilians as well as governments, with international bans having been agreed on. Thousands of tests have been performed, with most in the second half of the 20th century.

The first nuclear device was detonated as a test by the United States at the Trinity site in New Mexico on July 16, 1945, with a yield approximately equivalent to 20 kilotons of TNT. The first thermonuclear weapon technology test of an engineered device, codenamed Ivy Mike, was tested at the Enewetak Atoll in the Marshall Islands on November 1, 1952 (local date), also by the United States. The largest nuclear weapon ever tested was the Tsar Bomba of the Soviet Union at Novaya Zemlya on October 30, 1961, with the largest yield ever seen, an estimated 50–58 megatons.

With the advent of nuclear technology and its increasingly global fallout an anti-nuclear movement formed and in 1963, three (UK, US, Soviet Union) of the then four nuclear states and many non-nuclear states signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, pledging to refrain from testing nuclear weapons in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. The treaty permitted underground nuclear testing. France continued atmospheric testing until 1974, and China continued until 1980. Neither has signed the treaty.[1]

Underground tests conducted by the Soviet Union continued until 1990, the United Kingdom until 1991, the United States until 1992, and both China and France until 1996. In signing the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty in 1996, these countries pledged to discontinue all nuclear testing; the treaty has not yet entered into force because of its failure to be ratified by eight countries. Non-signatories India and Pakistan last tested nuclear weapons in 1998. North Korea conducted nuclear tests in 2006, 2009, 2013, January 2016, September 2016 and 2017. The most recent confirmed nuclear test occurred[update] in September 2017 in North Korea.

Types

[edit]

Nuclear weapons tests have historically been divided into four categories reflecting the medium or location of the test.

- Atmospheric testing involves explosions that take place in the atmosphere. Generally, these have occurred as devices detonated on towers, balloons, barges, or islands, or dropped from airplanes, and some only buried far enough to intentionally create a surface-breaking crater. The United States, the Soviet Union, and China have all conducted tests involving explosions of missile-launched warheads (See List of nuclear weapons tests#Tests of live warheads on rockets). Nuclear explosions close enough to the ground to draw dirt and debris into their mushroom cloud can generate large amounts of nuclear fallout due to irradiation of the debris (particularly with neutron radiation) as well as radioactive contamination of otherwise non-radioactive material. This definition of atmospheric is used in the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which banned this class of testing along with exoatmospheric and underwater.

- Underground testing is conducted under the surface of the earth, at varying depths. Underground nuclear testing made up the majority of nuclear tests by the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War; other forms of nuclear testing were banned by the Limited Test Ban Treaty in 1963. True underground tests are intended to be fully contained and emit a negligible amount of fallout. Unfortunately these nuclear tests do occasionally "vent" to the surface, producing from nearly none to considerable amounts of radioactive debris as a consequence. Underground testing, almost by definition, causes seismic activity of a magnitude that depends on the yield of the nuclear device and the composition of the medium in which it is detonated, and generally creates a subsidence crater.[2] In 1976, the United States and the USSR agreed to limit the maximum yield of underground tests to 150 kt with the Threshold Test Ban Treaty.

Underground testing also falls into two physical categories: tunnel tests in generally horizontal tunnel drifts, and shaft tests in vertically drilled holes. - Exoatmospheric testing is conducted above the atmosphere. The test devices are lifted on rockets. These high-altitude nuclear explosions can generate a nuclear electromagnetic pulse (NEMP) when they occur in the ionosphere, and charged particles resulting from the blast can cross hemispheres following geomagnetic lines of force to create an auroral display.

- Underwater testing involves nuclear devices being detonated underwater, usually moored to a ship or a barge (which is subsequently destroyed by the explosion). Tests of this nature have usually been conducted to evaluate the effects of nuclear weapons against naval vessels (such as in Operation Crossroads), or to evaluate potential sea-based nuclear weapons (such as nuclear torpedoes or depth charges). Underwater tests close to the surface can disperse large amounts of radioactive particles in water and steam, contaminating nearby ships or structures, though they generally do not create fallout other than very locally to the explosion.

Salvo tests

[edit]Another way to classify nuclear tests is by the number of explosions that constitute the test. The treaty definition of a salvo test is:

In conformity with treaties between the United States and the Soviet Union, a salvo is defined, for multiple explosions for peaceful purposes, as two or more separate explosions where a period of time between successive individual explosions does not exceed 5 seconds and where the burial points of all explosive devices can be connected by segments of straight lines, each of them connecting two burial points, and the total length does not exceed 40 kilometers. For nuclear weapon tests, a salvo is defined as two or more underground nuclear explosions conducted at a test site within an area delineated by a circle having a diameter of two kilometers and conducted within a total period of time of 0.1 seconds.[3]

The USSR has exploded up to eight devices in a single salvo test; Pakistan's second and last official test exploded four different devices. Almost all lists in the literature are lists of tests; in the lists in Wikipedia (for example, Operation Cresset has separate items for Cremino and Caerphilly, which together constitute a single test), the lists are of explosions.

Purpose

[edit]Separately from these designations, nuclear tests are also often categorized by the purpose of the test itself.

- Weapons-related tests are designed to garner information about how (and if) the weapons themselves work. Some serve to develop and validate a specific weapon type. Others test experimental concepts or are physics experiments meant to gain fundamental knowledge of the processes and materials involved in nuclear detonations.

- Weapons effects tests are designed to gain information about the effects of the weapons on structures, equipment, organisms, and the environment. They are mainly used to assess and improve survivability to nuclear explosions in civilian and military contexts, tailor weapons to their targets, and develop the tactics of nuclear warfare.

- Safety experiments are designed to study the behavior of weapons in simulated accident scenarios. In particular, they are used to verify that a (significant) nuclear detonation cannot happen by accident. They include one-point safety tests and simulations of storage and transportation accidents.

- Nuclear test detection experiments are designed to improve the capabilities to detect, locate, and identify nuclear detonations, in particular, to monitor compliance with test-ban treaties. In the United States these tests are associated with Operation Vela Uniform before the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty stopped all nuclear testing among signatories.

- Peaceful nuclear explosions were conducted to investigate non-military applications of nuclear explosives. In the United States, these were performed under the umbrella name of Operation Plowshare.

Aside from these technical considerations, tests have been conducted for political and training purposes, and can often serve multiple purposes.

Alternatives to full-scale testing

[edit]

Since the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, "nuclear explosions" of all kinds are banned. Nuclear nations have invested in many alternatives to maintain confidence in weapon capability:

- Computer simulation is used extensively to provide as much information as possible without physical testing. Mathematical models for such simulation model scenarios not only of performance but also of shelf life and maintenance.[4][5] A theme has generally been that even though simulations cannot fully replace physical testing, they can reduce the amount of it that is necessary.[6]

- Physical testing

- Materials testing

- Subcritical (or cold) tests involving fissile materials and high explosives that purposely result in no yield. The name refers to the lack of creation of a critical mass of fissile material. Subcritical tests continue to be performed by the United States, Russia, and the People's Republic of China, at least.[7][8]

- Proxy isotope testing: high temperature/density/pressure compression testing of non-fissile isotopes such as plutonium-242 or uranium-238, to determine a bomb core's relevant equation of state.

- Fission testing

- Critical mass experiments studying fissile material compositions, densities, geometries, and reflectors. They can be subcritical or supercritical, in which case significant radiation fluxes can be produced. This type of test has resulted in several criticality accidents.

- Hydronuclear tests (hydrodynamical + nuclear) study nuclear materials under the conditions of explosive shock compression. They can create subcritical conditions, or supercritical conditions with yields ranging from negligible all the way up to a substantial fraction of full weapon yield.[9] Any fission yield is considered banned by the CTBT.

- Fusion testing: inertial confinement fusion experiments using lasers, like the National Ignition Facility, or magnetized liners, like the Z Pulsed Power Facility, or projectile compression. They study the plasma physics and ignition of deuterium-tritium mixtures.

- Materials testing

Subcritical tests executed by the United States include:[10][11][12]

| Name | Date Time (UT[a]) | Location | Elevation + Height | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A series of 50 tests | January 1, 1960 | Los Alamos National Lab Test Area 49 35°49′22″N 106°18′08″W / 35.82289°N 106.30216°W | 2,183 metres (7,162 ft) and 20 metres (66 ft) | Series of 50 tests during US/USSR joint nuclear test ban.[13] |

| Odyssey | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | ||

| Trumpet | NTS Area U1a-102D 37°00′40″N 116°03′31″W / 37.01099°N 116.05848°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | ||

| Kismet | March 1, 1995 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 293 metres (961 ft) | Kismet was a proof of concept for modern hydronuclear tests; it did not contain any SNM (Special Nuclear Material—plutonium or uranium). |

| Rebound | July 2, 1997 10:—:— | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 293 metres (961 ft) | Provided information on the behavior of new plutonium alloys compressed by high-pressure shock waves; same as Stagecoach but for the age of the alloys. |

| Holog | September 18, 1997 | NTS Area U1a.101A 37°00′37″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01036°N 116.05888°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Holog and Clarinet may have switched locations. |

| Stagecoach | March 25, 1998 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Provided information on the behavior of aged (up to 40 years) plutonium alloys compressed by high-pressure shock waves. |

| Bagpipe | September 26, 1998 | NTS Area U1a.101B 37°00′37″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01021°N 116.05886°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Cimarron | December 11, 1998 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Plutonium surface ejecta studies. |

| Clarinet | February 9, 1999 | NTS Area U1a.101C 37°00′36″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01003°N 116.05898°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Holog and Clarinet may have switched places on the map. |

| Oboe | September 30, 1999 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Oboe 2 | November 9, 1999 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Oboe 3 | February 3, 2000 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Thoroughbred | March 22, 2000 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Plutonium surface ejecta studies, followup to Cimarron. |

| Oboe 4 | April 6, 2000 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Oboe 5 | August 18, 2000 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Oboe 6 | December 14, 2000 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Oboe 8 | September 26, 2001 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Oboe 7 | December 13, 2001 | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Oboe 9 | June 7, 2002 21:46:— | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Mario | August 29, 2002 19:00:— | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Plutonium surface studies (optical analysis of spall). Used wrought plutonium from Rocky Flats. |

| Rocco | September 26, 2002 19:00:— | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Plutonium surface studies (optical analysis of spall), followup to Mario. Used cast plutonium from Los Alamos. |

| Piano | September 19, 2003 20:44:— | NTS Area U1a.102C 37°00′39″N 116°03′32″W / 37.01095°N 116.05877°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | |

| Armando | May 25, 2004 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 290 metres (950 ft) | Plutonium spall measurements using x-ray analysis.[b] |

| Step Wedge | April 1, 2005 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | April–May 2005, a series of mini-hydronuclear experiments interpreting Armando results. |

| Unicorn | August 31, 2006 01:00:— | NTS Area U6c 36°59′12″N 116°02′38″W / 36.98663°N 116.0439°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | "...confirm nuclear performance of the W88 warhead with a newly-manufactured pit." Early pit studies. |

| Thermos | January 1, 2007 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | February 6 – May 3, 2007, 12 mini-hydronuclear experiments in thermos-sized flasks. |

| Bacchus | September 16, 2010 | NTS Area U1a.05? 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | |

| Barolo A | December 1, 2010 | NTS Area U1a.05? 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | |

| Barolo B | February 2, 2011 | NTS Area U1a.05? 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | |

| Castor | September 1, 2012 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | Not even a subcritical, contained no plutonium; a dress rehearsal for Pollux. |

| Pollux | December 5, 2012 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | A subcritical test with a scaled-down warhead mockup.[c] |

| Leda | June 15, 2014 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | Like Castor, the plutonium was replaced by a surrogate; this is a dress rehearsal for the later Lydia. The target was a weapons pit mock-up.[d] |

| Lydia | ??-??-2015 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | 1,222 metres (4,009 ft) and 190 metres (620 ft) | Expected to be a plutonium subcritical test with a scaled-down warhead mockup.[citation needed] |

| Vega | December 13, 2017 | Nevada test site | Plutonium subcritical test with a scaled down warhead mockup.[14] | |

| Ediza | February 13, 2019 | NTS Area U1a 37°00′41″N 116°03′35″W / 37.01139°N 116.05983°W | Plutonium subcritical test designed to confirm supercomputer simulations for stockpile safety.[15] | |

| Nightshade A | November 2020 | Nevada test site | Plutonium subcritical test designed to measure ejecta emission.[16][17] |

History

[edit]

| Significance | Country | Name | Date | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First plutonium test | Trinity | July 16, 1945 | 25 kt | |

| First implosion test | ||||

| First uranium bomb | Atomic bombing of Hiroshima | August 6, 1945 | 15 kt | |

| First gun-type bomb | ||||

| First thermonuclear boosting | Greenhouse George | May 8, 1951 | 225 kt | |

| First underground test | Buster–Jangle Uncle | November 29, 1951 | 1.2 kt | |

| First Teller-Ulam test | Ivy Mike | November 1, 1952 | 10.4 Mt | |

| First cryogenic deuterium test | ||||

| First deliverable thermonuclear test | RDS-6s | August 12, 1953 | 400 kt | |

| First solid-fuelled thermonuclear test | ||||

| First exoatmospheric test | Argus I | August 27, 1958 | 1.7 kt | |

| Most recent atmospheric test | 1980 Chinese nuclear test | October 16, 1980 | 1 Mt | |

| Most recent test | 2017 North Korean nuclear test | September 3, 2017 | 50-300 kt |

The first atomic weapons test was conducted near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, during the Manhattan Project, and given the codename "Trinity". The test was originally to confirm that the implosion-type nuclear weapon design was feasible, and to give an idea of what the actual size and effects of a nuclear explosion would be before they were used in combat against Japan. The test gave a good approximation of many of the explosion's effects, but did not give an appreciable understanding of nuclear fallout, which was not well understood by the project scientists until well after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The United States conducted six atomic tests before the Soviet Union developed their first atomic bomb (RDS-1) and tested it on August 29, 1949. Neither country had very many atomic weapons to spare at first, and so testing was relatively infrequent (when the US used two weapons for Operation Crossroads in 1946, they were detonating over 20% of their current arsenal). By the 1950s the United States had established a dedicated test site on its own territory (Nevada Test Site) and was also using a site in the Marshall Islands (Pacific Proving Grounds) for extensive atomic and nuclear testing.

The early tests were used primarily to discern the military effects of atomic weapons (Crossroads had involved the effect of atomic weapons on a navy, and how they functioned underwater) and to test new weapon designs. During the 1950s, these included new hydrogen bomb designs, which were tested in the Pacific, and also new and improved fission weapon designs. The Soviet Union also began testing on a limited scale, primarily in Kazakhstan. During the later phases of the Cold War, both countries developed accelerated testing programs, testing many hundreds of bombs over the last half of the 20th century.

Atomic and nuclear tests can involve many hazards. Some of these were illustrated in the US Castle Bravo test in 1954. The weapon design tested was a new form of hydrogen bomb, and the scientists underestimated how vigorously some of the weapon materials would react. As a result, the explosion—with a yield of 15 Mt—was over twice what was predicted. Aside from this problem, the weapon also generated a large amount of radioactive nuclear fallout, more than had been anticipated, and a change in the weather pattern caused the fallout to spread in a direction not cleared in advance. The fallout plume spread high levels of radiation for over 100 miles (160 km), contaminating populated islands in nearby atoll formations. Though they were soon evacuated, many of the islands' inhabitants suffered from radiation burns and later from other effects such as increased cancer rate and birth defects, as did the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Daigo Fukuryū Maru. One crewman died from radiation sickness after returning to port, and it was feared that the radioactive fish they had been carrying had made it into the Japanese food supply.

Castle Bravo was the worst US nuclear accident, but many of its component problems—unpredictably large yields, changing weather patterns, unexpected fallout contamination of populations and the food supply—occurred during other atmospheric nuclear weapons tests by other countries as well. Concerns over worldwide fallout rates eventually led to the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, which limited signatories to underground testing. Not all countries stopped atmospheric testing, but because the United States and the Soviet Union were responsible for roughly 86% of all nuclear tests, their compliance cut the overall level substantially. France continued atmospheric testing until 1974, and China until 1980.

A tacit moratorium on testing was in effect from 1958 to 1961 and ended with a series of Soviet tests in late 1961, including the Tsar Bomba, the largest nuclear weapon ever tested. The United States responded in 1962 with Operation Dominic, involving dozens of tests, including the explosion of a missile launched from a submarine.

Almost all new nuclear powers have announced their possession of nuclear weapons with a nuclear test. The only acknowledged nuclear power that claims never to have conducted a test was South Africa (although see Vela incident), which has since dismantled all of its weapons. Israel is widely thought to possess a sizable nuclear arsenal, though it has never tested, unless they were involved in Vela. Experts disagree on whether states can have reliable nuclear arsenals—especially ones using advanced warhead designs, such as hydrogen bombs and miniaturized weapons—without testing, though all agree that it is very unlikely to develop significant nuclear innovations without testing. One other approach is to use supercomputers to conduct "virtual" testing, but codes need to be validated against test data.

There have been many attempts to limit the number and size of nuclear tests; the most far-reaching is the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty of 1996, which has not, as of 2013[update], been ratified by eight of the "Annex 2 countries" required for it to take effect, including the United States. Nuclear testing has since become a controversial issue in the United States, with a number of politicians saying that future testing might be necessary to maintain the aging warheads from the Cold War. Because nuclear testing is seen as furthering nuclear arms development, many are opposed to future testing as an acceleration of the arms race.

In total nuclear test megatonnage, from 1945 to 1992, 520 atmospheric nuclear explosions (including eight underwater) were conducted with a total yield of 545 megatons,[19] with a peak occurring in 1961–1962, when 340 megatons were detonated in the atmosphere by the United States and Soviet Union,[20] while the estimated number of underground nuclear tests conducted in the period from 1957 to 1992 was 1,352 explosions with a total yield of 90 Mt.[19]

-

The first atomic test, "Trinity", took place on July 16, 1945.

-

The Sedan test of 1962 was an experiment by the United States in using nuclear weapons to excavate large amounts of earth.

-

Kytoon balloons were used on Indian Springs Air Force Base, Nevada, April 20, 1952, to get exact weather information during atomic test periods.

Yield

[edit]The yield of atomic and thermonuclear weapons is typically measured in kilotons or megatons TNT equivalent. Thermonuclear (fusion/fission by Teller-Ulam design) bombs, often mesaured in megatons, can be hundreds of times stronger than their atomic (fission only) counterparts measured only in kilotons.

In the US context, it was decided during the Manhattan Project that yield measured in tons of TNT equivalent could be imprecise. This comes from the range of experimental values of the energy content of TNT, ranging from 900 to 1,100 calories per gram (3,800 to 4,600 J/g). There is also the issue of which ton to use, as short tons, long tons, and metric tonnes all have different values. It was therefore decided that one kiloton would be equivalent to 1×1012 calories (4.2×1012 J) exactly,[21] (the equivalent of 1000 cal/g if the metric tonne were used).

Nuclear testing by country

[edit]

The nuclear powers have conducted more than 2,000 nuclear test explosions (numbers are approximate, as some test results have been disputed):

United States: 1,054 tests by official count (involving at least 1,149 devices). 219 were atmospheric tests as defined by the CTBT. These tests include 904 at the Nevada Test Site, 106 at the Pacific Proving Grounds and other locations in the Pacific, 3 in the South Atlantic Ocean, and 17 other tests taking place in Amchitka Alaska, Colorado, Mississippi, New Mexico and Nevada outside the NNSS (see Nuclear weapons and the United States for details). 24 tests are classified as British tests held at the NTS. There were 35 Plowshare detonations and 7 Vela Uniform tests; 88 tests were safety experiments and 4 were transportation/storage tests.[22] Motion pictures were made of the explosions, later used to validate computer simulation predictions of explosions.[23] United States' table data.

United States: 1,054 tests by official count (involving at least 1,149 devices). 219 were atmospheric tests as defined by the CTBT. These tests include 904 at the Nevada Test Site, 106 at the Pacific Proving Grounds and other locations in the Pacific, 3 in the South Atlantic Ocean, and 17 other tests taking place in Amchitka Alaska, Colorado, Mississippi, New Mexico and Nevada outside the NNSS (see Nuclear weapons and the United States for details). 24 tests are classified as British tests held at the NTS. There were 35 Plowshare detonations and 7 Vela Uniform tests; 88 tests were safety experiments and 4 were transportation/storage tests.[22] Motion pictures were made of the explosions, later used to validate computer simulation predictions of explosions.[23] United States' table data. Soviet Union: 715 tests (involving 969 devices) by official count, plus 13 unnumbered test failures.[24][25] Most were at their Southern Test Area at Semipalatinsk Test Site and the Northern Test Area at Novaya Zemlya. Others include rocket tests and peaceful-use explosions at various sites in Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Ukraine. Soviet Union's table data.

Soviet Union: 715 tests (involving 969 devices) by official count, plus 13 unnumbered test failures.[24][25] Most were at their Southern Test Area at Semipalatinsk Test Site and the Northern Test Area at Novaya Zemlya. Others include rocket tests and peaceful-use explosions at various sites in Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Ukraine. Soviet Union's table data. United Kingdom: 45 tests, of which 12 were in Australian territory, including three at the Montebello Islands and nine in mainland South Australia at Maralinga and Emu Field,[26] 9 at Christmas Island (Kiritimati) in the Pacific Ocean, plus 24 in the United States at the Nevada Test Site as part of joint test series).[27] 43 safety tests (the Vixen series) are not included in that number, though safety experiments by other countries are. The United Kingdom's summary table.

United Kingdom: 45 tests, of which 12 were in Australian territory, including three at the Montebello Islands and nine in mainland South Australia at Maralinga and Emu Field,[26] 9 at Christmas Island (Kiritimati) in the Pacific Ocean, plus 24 in the United States at the Nevada Test Site as part of joint test series).[27] 43 safety tests (the Vixen series) are not included in that number, though safety experiments by other countries are. The United Kingdom's summary table. France: 210 tests by official count (50 atmospheric, 160 underground[28]), four atomic atmospheric tests at C.S.E.M. near Reggane, 13 atomic underground tests at C.E.M.O. near In Ekker in the French Algerian Sahara, and nuclear atmospheric and underground tests at and around Fangataufa and Moruroa Atolls in French Polynesia. Four of the In Ekker tests are counted as peaceful use, as they were reported as part of the CET's APEX (Application pacifique des expérimentations nucléaires, “Peaceful Application of Nuclear Experiments”), and given alternate names. France's summary table.

France: 210 tests by official count (50 atmospheric, 160 underground[28]), four atomic atmospheric tests at C.S.E.M. near Reggane, 13 atomic underground tests at C.E.M.O. near In Ekker in the French Algerian Sahara, and nuclear atmospheric and underground tests at and around Fangataufa and Moruroa Atolls in French Polynesia. Four of the In Ekker tests are counted as peaceful use, as they were reported as part of the CET's APEX (Application pacifique des expérimentations nucléaires, “Peaceful Application of Nuclear Experiments”), and given alternate names. France's summary table. China: 45 tests (23 atmospheric and 22 underground), at Lop Nur Nuclear Weapons Test Base, in Malan, Xinjiang[29] There are two additional unnumbered failed tests. China's summary table.

China: 45 tests (23 atmospheric and 22 underground), at Lop Nur Nuclear Weapons Test Base, in Malan, Xinjiang[29] There are two additional unnumbered failed tests. China's summary table. India: Six underground explosions (including the first one in 1974), at Pokhran. India's summary table.

India: Six underground explosions (including the first one in 1974), at Pokhran. India's summary table. Pakistan: Six underground explosions at Ras Koh Hills and the Chagai District.[30] Pakistan's summary table.

Pakistan: Six underground explosions at Ras Koh Hills and the Chagai District.[30] Pakistan's summary table. North Korea: North Korea is the only country in the world that still tests nuclear weapons, and their tests have caused escalating tensions between them and the United States. Their most recent nuclear test was on September 3, 2017. North Korea's summary table

North Korea: North Korea is the only country in the world that still tests nuclear weapons, and their tests have caused escalating tensions between them and the United States. Their most recent nuclear test was on September 3, 2017. North Korea's summary table

There may also have been at least three alleged but unacknowledged nuclear explosions (see list of alleged nuclear tests) including the Vela incident.

From the first nuclear test in 1945 until tests by Pakistan in 1998, there was never a period of more than 22 months with no nuclear testing. June 1998 to October 2006 was the longest period since 1945 with no acknowledged nuclear tests.

A summary table of all the nuclear testing that has happened since 1945 is here: Worldwide nuclear testing counts and summary.

Global fallout

[edit]

Nuclear weapons testing did not produce scenarios like nuclear winter as a result of a scenario of a concentrated number of nuclear explosions in a nuclear holocaust, but the thousands of tests, hundreds being atmospheric, did nevertheless produce a global fallout that peaked in 1963 (the bomb pulse), reaching levels of about 0.15 mSv per year worldwide, or about 7% of average background radiation dose from all sources, and has slowly decreased since,[34] with natural environmental radiation levels being around 1 mSv. This global fallout was one of the main drivers for the ban of nuclear weapons testing, particularly atmospheric testing. It has been estimated that by 2020 between to 200,000 to 460,000 people have died as a result of nuclear weapons testing, while the total number of deaths may rise up to 2.4 million people.[35]

Criticism

[edit]Nuclear arms tests have been criticized for its arms race[36] and its fallout,[37][38][39] with a potentially global fallout.

Nuclear weapons tests have been criticized by anti-nuclear activists as nuclear imperialism, colonialism,[40] ecocide, environmental racism and nuclear genocide.[41][42][43]

The movement gained particularly in the 1960s and in the 1980s again.

The international day "End Nuclear Tests Day" raises critical awareness annually.[44]

Treaties against testing

[edit]There are many existing anti-nuclear explosion treaties, notably the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. These treaties were proposed in response to growing international concerns about environmental damage among other risks. Nuclear testing involving humans also contributed to the formation of these treaties. Examples can be seen in the following articles:

The Partial Nuclear Test Ban treaty makes it illegal to detonate any nuclear explosion anywhere except underground, in order to reduce atmospheric fallout. Most countries have signed and ratified the Partial Nuclear Test Ban, which went into effect in October 1963. Of the nuclear states, France, China, and North Korea have never signed the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.[45]

The 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) bans all nuclear explosions everywhere, including underground. For that purpose, the Preparatory Commission of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization is building an international monitoring system with 337 facilities located all over the globe. 85% of these facilities are already operational.[46] As of May 2012[update], the CTBT has been signed by 183 States, of which 157 have also ratified. For the Treaty to enter into force it needs to be ratified by 44 specific nuclear technology-holder countries. These "Annex 2 States" participated in the negotiations on the CTBT between 1994 and 1996 and possessed nuclear power or research reactors at that time. The ratification of eight Annex 2 states is still missing: China, Egypt, Iran, Israel and the United States have signed but not ratified the Treaty; India, North Korea and Pakistan have not signed it.[47]

The following is a list of the treaties applicable to nuclear testing:

| Name | Agreement date | In force date | In effect today? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unilateral USSR ban | March 31, 1958 | March 31, 1958 | no | USSR unilaterally stops testing provided the West does as well. |

| Bilateral testing ban | August 2, 1958 | October 31, 1958 | no | USA agrees; ban begins on 31 October 1958, 3 November 1958 for the Soviets, and lasts until abrogated by a USSR test on 1 September 1961. |

| Antarctic Treaty System | December 1, 1959 | June 23, 1961 | yes | Bans testing of all kinds in Antarctica. |

| Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) | August 5, 1963 | October 10, 1963 | yes | Ban on all but underground testing. |

| Outer Space Treaty | January 27, 1967 | October 10, 1967 | yes | Bans testing on the moon and other celestial bodies. |

| Treaty of Tlatelolco | February 14, 1967 | April 22, 1968 | yes | Bans testing in South America and the Caribbean Sea Islands. |

| Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty | January 1, 1968 | March 5, 1970 | yes | Bans the proliferation of nuclear technology to non-nuclear nations. |

| Seabed Arms Control Treaty | February 11, 1971 | May 18, 1972 | yes | Bans emplacement of nuclear weapons on the ocean floor outside territorial waters. |

| Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) | January 1, 1972 | no | A five-year ban on installing launchers. | |

| Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty | May 26, 1972 | August 3, 1972 | no | Restricts ABM development; additional protocol added in 1974; abrogated by the US in 2002. |

| Agreement on the Prevention of Nuclear War | June 22, 1973 | June 22, 1973 | yes | Promises to make all efforts to promote security and peace. |

| Threshold Test Ban Treaty | July 1, 1974 | December 11, 1990 | yes | Prohibits higher than 150 kt for underground testing. |

| Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty (PNET) | January 1, 1976 | December 11, 1990 | yes | Prohibits higher than 150 kt, or 1500kt in aggregate, testing for peaceful purposes. |

| Moon Treaty | January 1, 1979 | January 1, 1984 | no | Bans use and emplacement of nuclear weapons on the moon and other celestial bodies. |

| Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty (SALT II) | June 18, 1979 | no | Limits strategic arms. Kept but not ratified by the US, abrogated in 1986. | |

| Treaty of Rarotonga | August 6, 1985 | ? | Bans nuclear weapons in South Pacific Ocean and islands. US never ratified. | |

| Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) | December 8, 1987 | June 1, 1988 | no | Eliminated Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBMs). Implemented by 1 June 1991. Both sides alleged the other was in violation of the treaty. Expired following US withdrawal, 2 August 2019. |

| Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe | November 19, 1990 | July 17, 1992 | yes | Bans categories of weapons, including conventional, from Europe. Russia notified signatories of intent to suspend, 14 July 2007. |

| Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty I (START I) | July 31, 1991 | December 5, 1994 | no | 35-40% reduction in ICBMs with verification. Treaty expired 5 December 2009, renewed (see below). |

| Treaty on Open Skies | March 24, 1992 | January 1, 2002 | yes | Allows for unencumbered surveillance over all signatories. |

| US unilateral testing moratorium | October 2, 1992 | October 2, 1992 | no | George. H. W. Bush declares unilateral ban on nuclear testing.[48] Extended several times, not yet abrogated. |

| Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START II) | January 3, 1993 | January 1, 2002 | no | Deep reductions in ICBMs. Abrogated by Russia in 2002 in retaliation of US abrogation of ABM Treaty. |

| Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty (Treaty of Bangkok) | December 15, 1995 | March 28, 1997 | yes | Bans nuclear weapons from southeast Asia. |

| African Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Treaty (Pelindaba Treaty) | January 1, 1996 | July 16, 2009 | yes | Bans nuclear weapons in Africa. |

| Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) | September 10, 1996 | yes (effectively) | Bans all nuclear testing, peaceful and otherwise. Strong detection and verification mechanism (CTBTO). US has signed and adheres to the treaty, though has not ratified it. | |

| Treaty on Strategic Offensive Reductions (SORT, Treaty of Moscow) | May 24, 2002 | June 1, 2003 | no | Reduces warheads to 1700–2200 in ten years. Expired, replaced by START II. |

| START I treaty renewal | April 8, 2010 | January 26, 2011 | yes | Same provisions as START I. |

Compensation for victims

[edit]Over 500 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests were conducted at various sites around the world from 1945 to 1980. As public awareness and concern mounted over the possible health hazards associated with exposure to the nuclear fallout, various studies were done to assess the extent of the hazard. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ National Cancer Institute study claims that nuclear fallout might have led to approximately 11,000 excess deaths, most caused by thyroid cancer linked to exposure to iodine-131.[49]

- United States: Prior to March 2009, the US was the only nation to compensate nuclear test victims. Since the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990, more than $1.38 billion in compensation has been approved. The money is going to people who took part in the tests, notably at the Nevada Test Site, and to others exposed to the radiation.[50] As of 2017, the US government refused to pay for the medical care of troops who associate their health problems with the construction of Runit Dome in the Marshall Islands.[51]

- France: In March 2009, the French Government offered to compensate victims for the first time and legislation is being drafted which would allow payments to people who suffered health problems related to the tests.[52] The payouts would be available to victims' descendants and would include Algerians, who were exposed to nuclear testing in the Sahara in 1960. Victims say the eligibility requirements for compensation are too narrow.[citation needed]

- United Kingdom: There is no formal British government compensation program. Nearly 1,000 veterans of Christmas Island nuclear tests in the 1950s are engaged in legal action against the Ministry of Defense for negligence. They say they suffered health problems and were not warned of potential dangers before the experiments.[citation needed]

- Russia: Decades later, Russia offered compensation to veterans who were part of the 1954 Totsk test. There was no compensation to civilians sickened by the Totsk test. Anti-nuclear groups say there has been no government compensation for other nuclear tests.[citation needed]

- China: China has undertaken highly secretive atomic tests in remote deserts in a Central Asian border province. Anti-nuclear activists say there is no known government program for compensating victims.[citation needed]

Milestone nuclear explosions

[edit]The following list is of milestone nuclear explosions. In addition to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the first nuclear test of a given weapon type for a country is included, as well as tests that were otherwise notable (such as the largest test ever). All yields (explosive power) are given in their estimated energy equivalents in kilotons of TNT (see TNT equivalent). Putative tests (like Vela incident) have not been included.

| Date | Name | Yield (kt)

|

Country | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 16, 1945 | Trinity | 18–20 | United States | First fission-device test, first plutonium implosion detonation. |

| August 6, 1945 | Little Boy | 12–18 | United States | Bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, first detonation of a uranium gun-type device, first use of a nuclear device in combat. |

| August 9, 1945 | Fat Man | 18–23 | United States | Bombing of Nagasaki, Japan, second detonation of a plutonium implosion device (the first being the Trinity Test), second and last use of a nuclear device in combat. |

| August 29, 1949 | RDS-1 | 22 | Soviet Union | First fission-weapon test by the Soviet Union. |

| May 8, 1951 | George | 225 | United States | First boosted nuclear weapon test, first weapon test to employ fusion in any measure. |

| October 3, 1952 | Hurricane | 25 | United Kingdom | First fission weapon test by the United Kingdom. |

| November 1, 1952 | Ivy Mike | 10,400 | United States | First "staged" thermonuclear weapon, with cryogenic fusion fuel, primarily a test device and not weaponized. |

| November 16, 1952 | Ivy King | 500 | United States | Largest pure-fission weapon ever tested. |

| August 12, 1953 | RDS-6s | 400 | Soviet Union | First fusion-weapon test by the Soviet Union (not "staged"). |

| March 1, 1954 | Castle Bravo | 15,000 | United States | First "staged" thermonuclear weapon using dry fusion fuel. A serious nuclear fallout accident occurred. Largest nuclear detonation conducted by United States. |

| November 22, 1955 | RDS-37 | 1,600 | Soviet Union | First "staged" thermonuclear weapon test by the Soviet Union (deployable). |

| May 31, 1957 | Orange Herald | 720 | United Kingdom | Largest boosted fission weapon ever tested. Intended as a fallback "in megaton range" in case British thermonuclear development failed. |

| November 8, 1957 | Grapple X | 1,800 | United Kingdom | First (successful) "staged" thermonuclear weapon test by the United Kingdom |

| February 13, 1960 | Gerboise Bleue | 70 | France | First fission weapon test by France. |

| October 31, 1961 | Tsar Bomba | 50,000 | Soviet Union | Largest thermonuclear weapon ever tested—scaled down from its initial 100 Mt design by 50%. |

| October 16, 1964 | 596 | 22 | China | First fission-weapon test by the People's Republic of China. |

| June 17, 1967 | Test No. 6 | 3,300 | China | First "staged" thermonuclear weapon test by the People's Republic of China. |

| August 24, 1968 | Canopus | 2,600 | France | First "staged" thermonuclear weapon test by France |

| May 18, 1974 | Smiling Buddha | 12 | India | First fission nuclear explosive test by India. |

| May 11, 1998 | Pokhran-II | 45–50 | India | First potential fusion-boosted weapon test by India; first deployable fission weapon test by India. |

| May 28, 1998 | Chagai-I | 40 | Pakistan | First fission weapon (boosted) test by Pakistan[53] |

| October 9, 2006 | 2006 nuclear test | under 1 | North Korea | First fission-weapon test by North Korea (plutonium-based). |

| September 3, 2017 | 2017 nuclear test | 200–300 | North Korea | First "staged" thermonuclear weapon test claimed by North Korea. |

- Note

- "Staged" refers to whether it was a "true" thermonuclear weapon of the so-called Teller–Ulam configuration or simply a form of a boosted fission weapon. For a more complete list of nuclear test series, see List of nuclear tests. Some exact yield estimates, such as that of the Tsar Bomba and the tests by India and Pakistan in 1998, are somewhat contested among specialists.

See also

[edit]- Atmospheric focusing – Type of wave interaction causing shock waves

- Atomic Testing Museum (in Nevada in the US)

- High-altitude nuclear explosion – Nuclear detonations in the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere

- Historical nuclear weapons stockpiles and nuclear tests by country

- History of nuclear weapons

- International Day against Nuclear Tests – Annual observance on August 29

- How to Photograph an Atomic Bomb – 2006 book by Peter Kuran

- List of military nuclear accidents (including nuclear weapons accidents)

- List of nuclear weapons tests of the United States

- List of states with nuclear weapons

- Live fire exercise – Military exercise using live munitions

- National Technical Means – Methods of verification of adherence to international treaties

- Nuclear test sites

- Nuclear ethics – Academic and policy-relevant field on problems in the nuclear weapons and energy complex

- Nuclear weapons design

- Project Gnome – 1961 nuclear test explosion in New Mexico, United States

- Rope trick effect – "Spikes" emanating from suspended nuclear explosions

- Subsidence crater – Hole or depression left on the surface over the site of an underground explosion

- Test Readiness Program

- Trinity and Beyond (documentary about nuclear weapon testing)

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Universal Time at the Nevada National Security Site is 8 hours after local time; UT dates are one day after local date for UT times after 16:00.

- ^ A video of the Armando test on YouTube

- ^ A video of the Pollux test on YouTube

- ^ A video of the Leda test on YouTube

Citations

[edit]- ^ "The Treaty has not been signed by France or by the People's Republic of China." US Department of State, Limited Test Ban Treaty.

- ^ For a longer and more technical discussion, see US Congress, Office of Technology Assessment (October 1989). The Containment of Underground Nuclear Explosions (PDF). Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-02-27. Retrieved 2018-12-24.

- ^ Yang, Xiaoping; North, Robert; Romney, Carl; Richards, Paul R. "Worldwide Nuclear Explosions" (PDF).

- ^ Scoles, Sarah (2023-04-20). "Trust but verify: U.S. labs are overhauling the nuclear stockpile. Can they validate the weapons without bomb tests?". Science.

- ^ Hoffman, David E. (2011-11-01). "Supercomputers offer tools for nuclear testing — and solving nuclear mysteries". Washington Post.

- ^ Associated Press (2006-10-18). "Supercomputers can't perfectly simulate nuclear blasts: Experts". CBC News.

- ^ "US conducts 'subcritical' nuclear test". zeenews.india.com. 2012-12-07. Retrieved 2013-05-28.

- ^ Thomas Nilsen (2 October 2012). "Subcritical nuke tests may be resumed at Novaya Zemlya". barentsobserver.com. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- ^ Carey Sublette (9 August 2001), Nuclear Weapons Frequently Asked Questions, section 4.1.9, retrieved 10 April 2011

- ^ Papazian, Ghazar R.; Reinovsky, Robert E.; Beatty, Jerry N. (2003). "The New World of the Nevada Test Site" (PDF). Los Alamos Science (28). Retrieved 2013-12-12.

- ^ Thorn, Robert N.; Westervelt, Donald R. (February 1, 1987). "Hydronuclear Experiments" (PDF). LANL Report LA-10902-MS. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ Conrad, David C. (July 1, 2000). "Underground explosions are music to their ears". Science and Technology Review. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Nevada Test Site: U1a Complex subcritical experiments (PDF) (Report). DOE Nevada. February 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2003.

- ^ Kishner, Andrew (18 September 2018). "U.S. Sneaks in 'Vega,' Its 28th Subcritical Nuclear Test". Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ O'Brien, Nolan (24 May 2019). "Subcritical experiment captures scientific measurements to advance stockpile safety". LLNL. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "US conducted subcritical nuclear test in November". NHK World-Japan. 16 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Danielson, Jeremy; Bauer, Amy L. (September 2016). Nightshade Prototype Experiments (Silverleaf). Los Alamos National Laboratory (Report). OSTI. doi:10.2172/1338708. OSTI 1338708.

- ^ Togzhan Kassenova (28 September 2009). "The lasting toll of Semipalatinsk's nuclear testing". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ^ a b Pavlovski, O. A. (1 January 1998). "Radiological Consequences of Nuclear Testing for the Population of the Former USSR (Input Information, Models, Dose, and Risk Estimates)". Atmospheric Nuclear Tests. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 219–260. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-03610-5_17. ISBN 978-3-642-08359-4.

- ^ "Radioactive Fallout - Worldwide Effects of Nuclear War - Historical Documents". Atomciarchive.com.

- ^ The Containment of Underground Explosions (Report). Office of Technology Assessment. 31 October 1989. p. 11. OTA-ISC-414.

- ^ "United States Nuclear Tests: July 1945 through September 1992" (PDF). Las Vegas, NV: Department of Energy, Nevada Operations Office. 2000-12-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-12. Retrieved 2013-12-18. This is usually cited as the "official" US list.

- ^ Long, Kat. "Blasts from the Past: Old Nuke Test Films Offer New Insights [Video]". Scientific American. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ^ "USSR Nuclear Weapons Tests and Peaceful Nuclear Explosions 1949 through 1990" (Document). Sarov, Russia: RFNC-VNIIEF. 1996. The official Russian list of Soviet tests.

- ^ Mikhailov, Editor in Chief, V.N.; Andryushin, L.A.; Voloshin, N.P.; Ilkaev, R.I.; Matushchenko, A.M.; Ryabev, L.D.; Strukov, V.G.; Chernyshev, A.K.; Yudin, Yu.A. "Catalog of Worldwide Nuclear Testing". Archived from the original on 2013-12-19. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help)An equivalent list available on the internet. - ^ "British nuclear weapons testing in Australia | ARPANSA". Retrieved 2022-11-02.

- ^ "UK/US Agreement". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

- ^ "N° 3571.- Rapport de MM. Christian Bataille et Henri Revol sur les incidences environnementales et sanitaires des essais nucléaires effectués par la France entre 1960 et 1996 (Office d'évaluation des choix scientifiques et technologiques)". Assemblee-nationale.fr. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

- ^ "Nuclear Weapons Test List". Fas.org. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan Special Weapons - A Chronology". Archived from the original on 2012-04-27. Retrieved 2018-12-24.

- ^ "Atmospheric δ14C record from Wellington". Trends: A Compendium of Data on Global Change. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. 1994. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ^ Levin, I.; et al. (1994). "δ14C record from Vermunt". Trends: A Compendium of Data on Global Change. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Radiocarbon dating". University of Utrecht. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

- ^ Bouville, André; Simon, Steven L.; Miller, Charles W.; Beck, Harold L.; Anspaugh, Lynn R.; Bennett, Burton G. (2002). "Estimates of Doses from Global Fallout". Health Physics. 82 (5): 690–705. Bibcode:2002HeaPh..82..690B. doi:10.1097/00004032-200205000-00015. ISSN 0017-9078. PMID 12003019.

- ^ Adams, Lilly (May 26, 2020). "Resuming Nuclear Testing a Slap in the Face to Survivors". The Equation. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Kinsella, William (2023-08-04). "The nuclear arms race's legacy: Contamination, staggering cleanup costs and a culture of secrecy • Missouri Independent". Missouri Independent. Retrieved 2025-01-07.

- ^ Prăvălie, Remus (2014-02-22). "Nuclear Weapons Tests and Environmental Consequences: A Global Perspective". Ambio. 43 (6). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 729–744. Bibcode:2014Ambio..43..729P. doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0491-1. ISSN 0044-7447. PMC 4165831. PMID 24563393.

- ^ Seale, Jack (2024-11-20). "Britain's Nuclear Bomb Scandal: Our Story review – how the UK's atomic testing programme devastated lives". the Guardian. Retrieved 2025-01-07.

- ^ "Banning nuclear explosions protects the environment". CTBTO. Retrieved 2025-01-07.

- ^ Hennaoui, Leila; Nurzhan, Marzhan (2023-10-02). "Dealing with a Nuclear Past: Revisiting the Cases of Algeria and Kazakhstan through a Decolonial Lens". The International Spectator. 58 (4): 91–109. doi:10.1080/03932729.2023.2234817. ISSN 0393-2729.

- ^ Skinner, Rob (2021-09-30). "'Against Nuclear Imperialism': peace, race and anti-colonialism in the early 1960s". University of Bristol. Retrieved 2025-01-03.

- ^ Hsu, Hsuan L. (2014-05-21). "Nuclear colonialism". Environment & Society Portal. Retrieved 2025-01-03.

- ^ Maguire, Richard (2007). "From the Guest Editor: The nuclear weapon and genocide: The beginning of a discussion". Journal of Genocide Research. 9 (3): 353–360. doi:10.1080/14623520701528866. ISSN 1462-3528.

- ^ Nations, United (1945-07-16). "End Nuclear Tests Day". United Nations. Retrieved 2025-01-08.

- ^ U.S. Department of State, Limited Test Ban Treaty.

- ^ "CTBTO Factsheet: Ending Nuclear Explosions" (PDF). Ctbto.org. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ^ "Status of signature and ratification". Ctbto.org. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- ^ "The Status of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty: Signatories and Ratifiers". Arms Control Association. March 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ Council, National Research (11 February 2003). Exposure of the American Population to Radioactive Fallout from Nuclear Weapons Tests: A Review of the CDC-NCI Draft Report on a Feasibility Study of the Health Consequences to the American Population from Nuclear Weapons Tests Conducted by the United States and Other Nations. doi:10.17226/10621. ISBN 9780309087131. PMID 25057651.

- ^ "Radiation Exposure Compensation System: Claims to Date Summary of Claims Received by 06/11/2009" (PDF). Usdoj.gov.

- ^ "Troops Who Cleaned Up Radioactive Islands Can't Get Medical Care". The New York Times. 28 January 2017.

- ^ Hardach, Sophie; Shirbon, Estelle (24 March 2009). "France to compensate victims of nuclear testing". Reuters. Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Pakistan Nuclear Weapons: A Brief History of Pakistan's Nuclear Program". Federation of American Scientists. 11 December 2002. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

General and cited references

[edit]- Gusterson, Hugh. Nuclear Rites: A Weapons Laboratory at the End of the Cold War. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996.

- Hacker, Barton C. Elements of Controversy: The Atomic Energy Commission and Radiation Safety in Nuclear Weapons Testing, 1947–1974. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

- Rice, James. Downwind of the Atomic State: Atmospheric Testing and the Rise of the Risk Society. (New York University Press, 2023). https://nyupress.org/9781479815340/downwind-of-the-atomic-state/

- Schwartz, Stephen I. Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1998.

- Weart, Spencer R. Nuclear Fear: A History of Images. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

External links

[edit]- Federation of American Scientists Archived 2016-09-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban-Treaty Organization

- Nuclear Weapon Archive

- NuclearFiles.org

- What About Radiation on Bikini Atoll?

- "Time-lapse map of all nuclear weapon tests from 1945 to 1998." on YouTube

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Atomic Bomb website and nuclear weapon testing articles

- The Woodrow Wilson Center's Nuclear Proliferation International History Project

Nuclear weapons testing

View on GrokipediaTechnical Fundamentals

Types of Nuclear Tests

Nuclear weapons tests are primarily classified by the physical environment in which the detonation occurs, as this determines the propagation of blast effects, radiation dispersal, and detectability.[1] The main categories include atmospheric, underground, underwater, and exoatmospheric tests, each conducted to gather data on weapon performance under specific conditions while assessing environmental and strategic implications.[9] Atmospheric tests involve detonations in the open air, either as air bursts at altitude, surface bursts on land, or elevated shots using towers or balloons. These tests, totaling 528 globally, produced visible fireballs and widespread fallout due to direct interaction with the atmosphere, allowing observation of full-scale effects like thermal radiation and electromagnetic pulses but risking global radioactive contamination.[1] The United States conducted 215 such tests between 1945 and 1962, including the Trinity test on July 16, 1945, which yielded 21 kilotons and marked the first artificial nuclear explosion.[9] Atmospheric testing ended for most nations following the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited tests outside underground environments to mitigate health and environmental hazards from fallout.[1] Underground tests, comprising 1,528 detonations worldwide, occur in shafts or tunnels beneath the Earth's surface, typically at depths of hundreds of meters to contain blast and radiation.[1] This method, adopted post-1963 treaty, minimizes atmospheric fallout but can cause seismic activity and venting of radioactive gases if containment fails, as seen in some U.S. Nevada Test Site events.[9] The U.S. performed 815 underground tests from 1963 to 1992, using vertical boreholes for device emplacement and horizontal tunnels for diagnostics, enabling precise measurement of yield and efficiency without surface disruption.[9] These tests supported weapon reliability verification amid escalating yields, such as the 15-megaton Castle Bravo miscalculation in 1954, though that was atmospheric.[10] Underwater tests detonate devices submerged in water, studying hydrodynamic effects, shockwave propagation, and hull damage to ships, as in the U.S. Operation Crossroads Baker shot on July 25, 1946, at Bikini Atoll, which yielded 23 kilotons and contaminated vessels severely.[9] Fewer than atmospheric tests, they highlighted neutron activation of seawater and biological impacts but were largely curtailed by treaties due to marine ecosystem disruption.[1] Exoatmospheric or high-altitude tests explode above the sensible atmosphere, often via rocket delivery, to examine effects like gamma-ray induced auroras and satellite disruptions, exemplified by the U.S. Starfish Prime on July 9, 1962, at 400 kilometers altitude yielding 1.4 megatons.[9] These produced no local fallout but generated artificial radiation belts affecting electronics over vast areas, informing anti-satellite and EMP weaponization studies.[1] Additional categories include peaceful nuclear explosions (PNEs), such as the U.S. Plowshare program's 35 underground or cratering shots for civil engineering like excavation, banned under the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty as indistinguishable from weapons tests.[9] Subcritical tests, using conventional explosives to compress fissile material without achieving supercriticality or yield, comply with test ban treaties and sustain stockpile confidence through hydrodynamic simulations, as conducted at U.S. sites like the Nevada National Security Site.[11] Hydronuclear tests, producing minimal fission yield to verify implosion dynamics, represent a gray area but were phased out under moratoria.[1]Yield Assessment and Measurement

The explosive yield of a nuclear weapon, defined as the total energy released and conventionally expressed in kilotons (kt) or megatons (Mt) of TNT equivalent, is assessed through a combination of direct instrumentation, empirical scaling laws, and post-detonation analysis tailored to the test environment. For early atmospheric tests like the 1945 Trinity detonation, yields were initially estimated indirectly via hydrodynamic scaling laws applied to declassified blast radius photographs, as pioneered by G.I. Taylor, yielding an approximate value of 18-22 kt without classified data on energy input. Subsequent radiochemical analysis of trinitite samples from Trinity, involving decay counting and mass spectrometry of isotopes such as molybdenum, has refined the yield to approximately 24.8 ± 2.0 kt, accounting for fission efficiency and neutron fluence. These methods cross-validate against fireball imaging and thermal radiation data, which for the Hiroshima bomb converged on 21 kt using radiochemistry and optical measurements of initial luminosity. In atmospheric and underwater tests, yield determination often relies on multi-parameter diagnostics including overpressure gauges for shock wave propagation, bhangmeter readings for fireball luminosity, and radiochemical sampling of debris clouds via aircraft or rockets to quantify fission products and neutron activation ratios. For instance, post-test debris analysis measures isotopic ratios (e.g., uranium-235 fission remnants) to compute the fission fraction, supplemented by gamma-ray spectroscopy for fusion-boosted components, achieving uncertainties typically under 10-20% for yields above 1 kt. Crater dimensions and ejecta volume provide additional scaling for surface or shallow bursts, calibrated against known TNT benchmarks. Underground tests, comprising the majority of post-1963 detonations under the Partial Test Ban Treaty, predominantly use seismic monitoring to estimate yield, converting body-wave or surface-wave magnitudes (mb or Ms) to energy release via site-specific empirical formulas that correct for geology, depth, and decoupling effects. The process involves recording teleseismic P-waves, applying magnitude-yield relations like log(Y) = A(mb - C) + B (where Y is yield in kt, and A, B, C are calibrated constants), with corrections for tectonic release or cavity tamping reducing errors to 20-50% for contained explosions up to 1 Mt. Hydrodynamic sensors in boreholes and radionuclide venting analysis serve as confirmatory techniques, though seismic methods dominate for remote assessments of foreign tests due to their global detectability. Uncertainties persist in adversarial contexts, as evidenced by debates over Soviet yields at Semipalatinsk, where seismic data required decoupling adjustments to align with 10-100 kt ranges.Testing Methodologies and Sites

Nuclear weapons testing methodologies encompass a range of techniques designed to evaluate device performance, yield, and effects under controlled conditions, evolving from open-air detonations to contained explosions to minimize environmental release while adhering to international treaties post-1963.[9] Primary categories include atmospheric tests, conducted in the open air via methods such as tower-mounted devices, balloon suspension for elevated bursts, airdrops from aircraft, or surface placements; these allowed direct observation of fireball dynamics, blast waves, and thermal radiation but dispersed fallout widely until prohibited by the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty.[12] Underground testing, predominant after the 1960s, involved emplacing devices in vertical shafts—typically 100 to 2,000 feet deep—or horizontal tunnels to contain the explosion and limit venting, with over 800 such tests at U.S. sites alone between 1951 and 1992; shaft tests focused on yield measurement via seismic data and cavity analysis, while tunnels enabled effects simulations on structures or materials.[13][14] Other variants include underwater detonations for naval effects studies, as in Operation Crossroads (1946), and exoatmospheric or space tests to assess high-altitude electromagnetic pulses, exemplified by U.S. Starfish Prime in 1962.[15] Post-moratorium, subcritical experiments—using conventional explosives on fissile materials without achieving criticality—have sustained stockpile certification, conducted in tunnels at sites like the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS).[12] Test sites were selected for geographic isolation, geological stability, and logistical access, often repurposed military areas to facilitate rapid iteration amid Cold War imperatives. The United States executed 1,030 tests, with 928 at the NNSS (formerly Nevada Test Site) in Yucca Flat and Pahute Mesa—ideal for underground containment due to alluvial basins and tuff layers—and 106 in the Pacific Proving Grounds at Bikini and Enewetak Atolls for atmospheric and underwater trials, though these caused extensive radiological contamination.[1][13] The Soviet Union conducted 715 tests, primarily at the Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan (456 explosions, including early atmospheric and later underground in salt domes for containment) and Novaya Zemlya in the Arctic (132 tests, focused on thermonuclear yields up to 50 megatons).[1] France performed 210 detonations, shifting from the Algerian Sahara (13 atmospheric at Reggane and In Ekker, 1960-1966) to French Polynesia's Moruroa and Fangataufa Atolls (193 underwater and atmospheric tests), where coral geology proved inadequate for full containment, leading to documented leakage.[1] The United Kingdom's 45 tests included joint U.S. operations at NNSS, independent atmospheric blasts at Monte Bello Islands and Maralinga in Australia (1952-1957), and Christmas Island in the Pacific, selected for imperial access but resulting in long-term indigenous exposure.[1] China's 45 tests occurred exclusively at Lop Nur in Xinjiang, utilizing desert basins for both atmospheric (23) and underground (22) methods from 1964 onward, with yields scaling to megaton range by the 1970s.[1]| Nation | Primary Sites | Test Count | Key Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Nevada National Security Site; Pacific Proving Grounds | 1,030 | Underground shafts/tunnels; atmospheric airdrops/towers; subcritical (post-1992)[1][13] |

| Soviet Union/Russia | Semipalatinsk; Novaya Zemlya | 715 | Atmospheric surface/airbursts; underground in salt/caverns[1] |

| United Kingdom | Maralinga/Monte Bello (Australia); Christmas Island; NNSS (joint) | 45 | Atmospheric towers/balloons; limited underground[1] |

| France | Reggane/In Ekker (Algeria); Moruroa/Fangataufa (Polynesia) | 210 | Atmospheric; underwater; shaft/tunnel underground[1] |

| China | Lop Nur | 45 | Atmospheric drop; vertical shaft underground[1] |

Strategic and Developmental Objectives

Deterrence and Arsenal Reliability

Nuclear weapons testing plays a critical role in establishing and maintaining the reliability of arsenals, which forms the foundation of credible nuclear deterrence by assuring potential adversaries of the certainty of devastating retaliation. Full-scale explosive tests allow verification of warhead performance, including yield, delivery integration, and resilience to environmental stresses, thereby building empirical confidence in operational effectiveness.[17] Historically, the United States conducted over 1,000 nuclear tests from 1945 to 1992 to refine designs and certify reliability, enabling a deterrent posture that prevented direct great-power conflict during the Cold War.[18] Following the U.S. voluntary moratorium on explosive testing in September 1992, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has relied on the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) to sustain arsenal reliability without full-yield detonations. The SSP integrates supercomputer simulations, hydrodynamic testing, and subcritical experiments—non-nuclear explosions that assess plutonium behavior under compression—to annually certify the safety, security, and effectiveness of the approximately 3,700 warheads in the U.S. stockpile.[19][20] These methods leverage data from prior tests and advanced diagnostics to detect potential degradation in components like pits and boosters, with annual presidential certifications affirming high confidence in performance since the moratorium.[21] Debates persist regarding the long-term sufficiency of test-ban-era approaches for deterrence, as adversaries such as Russia, China, and North Korea have conducted post-1992 tests to validate modernized arsenals, potentially exploiting perceived U.S. vulnerabilities from untested modifications or aging effects. Critics, including some defense analysts, contend that without occasional explosive testing, uncertainties in low-probability failure modes could undermine deterrence credibility, especially amid peer competitors' advancements in hypersonics and defenses that challenge legacy designs.[22] Proponents of the moratorium counter that SSP's science-based tools provide robust assurance, with resumption risking global proliferation and norm erosion without proportional reliability gains.[23] Empirical outcomes, including the absence of stockpile failures in surveillance programs, support continued certification, though causal links to deterrence efficacy remain inferential absent real-world use.[24]Scientific Advancements from Testing

![Castle Bravo thermonuclear test, March 1, 1954][float-right] Nuclear weapons testing provided critical empirical data on fission and fusion processes, enabling refinements in theoretical models of nuclear reactions under extreme conditions. The Trinity test on July 16, 1945, at Alamogordo, New Mexico, confirmed the viability of plutonium implosion designs, yielding approximately 20 kilotons and validating chain reaction dynamics predicted by Los Alamos scientists.[25] This test resolved uncertainties in neutron multiplication and criticality, foundational to subsequent weapon designs and broader nuclear physics.[9] The Ivy Mike test on November 1, 1952, at Enewetak Atoll, demonstrated the Teller-Ulam staged thermonuclear configuration, achieving a yield of 10.4 megatons through deuterium-tritium fusion boosted by a fission primary.[26] Analysis of debris revealed the first synthesis of superheavy elements einsteinium and fermium, expanding the periodic table and advancing understanding of heavy ion production in high-flux neutron environments.[26] These insights confirmed fusion ignition mechanisms and informed multi-stage weapon architectures.[27] Operation Castle Bravo on March 1, 1954, at Bikini Atoll, unexpectedly yielded 15 megatons due to unanticipated tritium production from lithium-7 fission, revealing previously unknown reaction pathways in lithium deuteride fuels.[28] This discovery shifted fusion design paradigms toward "dry" fuels, eliminating cryogenic requirements and enabling compact, deliverable thermonuclear weapons.[29] The test's diagnostics, including radiochemical sampling, provided data on plasma evolution and radiation hydrodynamics, contributing to high-energy-density physics.[9] Testing advanced materials science by exposing alloys and composites to gigabar pressures and temperatures exceeding 100 million kelvin, yielding data on phase transitions, spallation, and defect formation unattainable in laboratories until recent decades.[30] Effects simulations from tests like Starfish Prime on July 9, 1962, elucidated electromagnetic pulse generation and artificial radiation belts, informing space weather models and satellite hardening.[31] Seismic monitoring of over 2,000 global tests refined crustal wave propagation models, enhancing earthquake detection and geophysics.[9] Instrumentation innovations, such as ultra-high-speed framing cameras and neutron flux detectors developed for yield measurements, extended to non-nuclear applications in plasma research and shock physics.[9] Fallout isotope analysis from atmospheric tests traced global dispersion patterns, advancing atmospheric chemistry and radiobiology, though primarily through unintended releases rather than controlled experiments.[32] These empirical validations underpinned computational codes for simulating nuclear phenomena, bridging first-principles hydrodynamics with observed outcomes.[9]Safety and Stockpile Stewardship

Safety protocols during nuclear weapons testing evolved from rudimentary measures in the 1940s to more structured evacuation and monitoring by the 1950s, yet atmospheric tests exposed personnel and nearby populations to ionizing radiation via fallout.[33] Empirical studies indicate that fallout from U.S. atmospheric tests, particularly iodine-131 from Nevada sites between 1951 and 1962, resulted in elevated thyroid doses for downwind populations, contributing to an estimated 10,000 to 75,000 additional thyroid cancer cases nationwide, though overall cancer risk increases were modest relative to background rates.[34] The 1954 Castle Bravo test, yielding 15 megatons, exemplified risks when unexpected lithium hydride fusion produced massive fallout, irradiating Marshall Islanders and Japanese fishermen with doses up to 17 rads, leading to acute radiation sickness in some and long-term health issues.[5] Underground testing, mandated by the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty, reduced public exposure but introduced containment challenges, with venting incidents like the 1968 Baneberry test releasing 0.04% of its yield as fallout due to a cracked containment chimney.[35] Health monitoring programs, such as the U.S. Nuclear Test Personnel Review, have documented slightly elevated leukemia and solid tumor rates among participants, though confounding factors like smoking complicate attribution solely to radiation.[36] These incidents underscored the trade-offs in testing for deterrence reliability versus environmental and human health costs, with total U.S. test yields exceeding 200 megatons by 1992.[4] Post-1992 U.S. testing moratorium, the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP), established under Presidential Decision Directive 15, maintains nuclear arsenal safety, security, and reliability through advanced simulations, hydrodynamic tests, and subcritical experiments without producing a nuclear yield, ensuring compliance with the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.[37] Subcritical tests, conducted at the Nevada National Security Site since 1997, compress special nuclear materials with high explosives to replicate weapon physics under extreme conditions, validating models of plutonium aging and safety features like insensitive high explosives.[38] As of 2024, the National Nuclear Security Administration completed experiments at the PULSE facility, gathering data on material behavior to certify warheads annually without full-scale detonations.[39] The SSP integrates supercomputing at facilities like Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where campaigns simulate decades of stockpile aging effects, predicting failures in safety mechanisms such as fire-resistant pits or one-point safety, with confidence derived from cross-validating against historical test data totaling over 1,000 U.S. explosions.[21] This approach has sustained certification of the enduring stockpile—approximately 3,700 warheads as of 2023—amid concerns over plutonium pit degradation, prompting investments in production facilities to replace aging components by the 2030s.[19] Critics argue simulations cannot fully replicate fission chain reactions, but empirical validation through subcritical and radiographic data has upheld reliability assessments, averting the need for resumed testing despite geopolitical tensions.[20]Historical Evolution

Origins in World War II and Immediate Postwar (1940s)