Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

History of nuclear weapons

View on Wikipedia

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

Building on major scientific breakthroughs made during the 1930s, the United Kingdom began the world's first nuclear weapons research project, codenamed Tube Alloys, in 1941, during World War II. The United States, in collaboration with the United Kingdom, initiated the Manhattan Project the following year to build a weapon using nuclear fission. The project also involved Canada.[1] In August 1945, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were conducted by the United States, with British consent, against Japan at the close of that war, standing to date as the only use of nuclear weapons in hostilities.[2]

The Soviet Union started development shortly after with their own atomic bomb project, and not long after, both countries were developing even more powerful fusion weapons known as hydrogen bombs. Britain and France built their own systems in the 1950s, and the number of states with nuclear capabilities has gradually grown larger in the decades since.

A nuclear weapon, also known as an atomic bomb, possesses enormous destructive power from nuclear fission, or a combination of fission and fusion reactions.

Background

[edit]

In the first decades of the 19th century, physics was revolutionized with developments in the understanding of the nature of atoms including the discoveries in atomic theory by John Dalton.[3] Around the turn of the 20th century, it was discovered by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden and then Ernest Rutherford, that atoms had a highly dense, very small, charged central core called an atomic nucleus. In 1898, Pierre and Marie Curie discovered that pitchblende, an ore of uranium, contained a substance—which they named radium—that emitted large amounts of radiation. Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy identified that atoms were breaking down and turning into different elements. Hopes were raised among scientists and laymen that the elements around us could contain tremendous amounts of unseen energy, waiting to be harnessed. In 1905, Albert Einstein described this potential in his famous equation, E = mc2.

H. G. Wells was inspired by the work of Rutherford to write about an "atom bomb" in a 1914 novel, The World Set Free, which appeared shortly before the First World War.[4] In a 1924 article, Winston Churchill speculated about the possible military implications: "Might not a bomb no bigger than an orange be found to possess a secret power to destroy a whole block of buildings—nay to concentrate the force of a thousand tons of cordite and blast a township at a stroke?"[5]

At the time however, there was no known mechanism which could be used to unlock the vast energy potential that was theorized to exist inside the atom. The only particle then known to exist within the nucleus was the positively-charged proton, which would act to repel protons set in motion towards it. Then in 1932, a key breakthrough was made with the discovery of the neutron. Having no electric charge, the neutron is able to penetrate the nucleus with relative ease.

In January 1933, the Nazis came to power in Germany and suppressed Jewish scientists. Physicist Leo Szilard fled to London where, in 1934, he patented the idea of a nuclear chain reaction using neutrons. The patent also introduced the term critical mass to describe the minimum amount of material required to sustain the chain reaction and its potential to cause an explosion (British patent 630,726). The patent was not about an atomic bomb per se, as the possibility of chain reaction was still very speculative. Szilard subsequently assigned the patent to the British Admiralty so that it could be covered by the Official Secrets Act.[6] This work of Szilard's was ahead of the time, five years before the public discovery of nuclear fission and eight years before a working nuclear reactor. When he coined the term neutron inducted chain reaction, he was not sure about the use of isotopes or standard forms of elements. Despite this uncertainty, he correctly theorized uranium and thorium as primary candidates for such a reaction, along with beryllium which was later determined to be unnecessary in practice. Szilard joined Enrico Fermi in developing the first uranium-fuelled nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, which was activated at the University of Chicago in 1942.[7]

In Paris in 1934, Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie discovered that artificial radioactivity could be induced in stable elements by bombarding them with alpha particles; in Italy Enrico Fermi reported similar results when bombarding uranium with neutrons. He mistakenly believed he had discovered elements 93 and 94, naming them ausenium and hesperium. In 1938 it was realized these were in fact fission products.[citation needed]

In December 1938, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann reported that they had detected the element barium after bombarding uranium with neutrons. Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch correctly interpreted these results as being due to the splitting of the uranium atom. Frisch confirmed this experimentally on January 13, 1939.[8] They gave the process the name "fission" because of its similarity to the splitting of a cell into two new cells. Even before it was published, news of Meitner's and Frisch's interpretation crossed the Atlantic.[9] In their second publication on nuclear fission in February 1939, Hahn and Strassmann predicted the existence and liberation of additional neutrons during the fission process, opening up the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction.

After learning about the German fission in 1939, Leo Szilard concluded that uranium would be the element which could realize his 1933 idea about nuclear chain reaction.[10]

In the United States, scientists at Columbia University in New York City decided to replicate the experiment and on January 25, 1939, conducted the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States[11] in the basement of Pupin Hall. The following year, they identified the active component of uranium as being the rare isotope uranium-235.[12]

Between 1939 and 1940, Joliot-Curie's team applied for a patent family covering different use cases of atomic energy, one (case III, in patent FR 971,324 - Perfectionnements aux charges explosives, meaning Improvements in Explosive Charges) being the first official document explicitly mentioning a nuclear explosion as a purpose, including for war.[13] This patent was applied for on May 4, 1939, but only granted in 1950, being withheld by French authorities in the meantime.

Uranium appears in nature primarily in two isotopes: uranium-238 and uranium-235. When the nucleus of uranium-235 absorbs a neutron, it undergoes nuclear fission, releasing energy and, on average, 2.5 neutrons. Because uranium-235 releases more neutrons than it absorbs, it can support a chain reaction and so is described as fissile. Uranium-238, on the other hand, is not fissile as it does not normally undergo fission when it absorbs a neutron.

By the start of the war in September 1939, many scientists likely to be persecuted by the Nazis had already escaped. Physicists on both sides were well aware of the possibility of utilizing nuclear fission as a weapon, but no one was quite sure how it could be engineered. In August 1939, concerned that Germany might have its own project to develop fission-based weapons, Albert Einstein signed a letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning him of the threat.[14]

Roosevelt responded by setting up the Uranium Committee under Lyman James Briggs but, with little initial funding ($6,000), progress was slow. It was not until the U.S. entered the war in December 1941 that Washington decided to commit the necessary resources to a top-secret high priority bomb project.[15]

Organized research first began in Britain and Canada as part of the Tube Alloys project: the world's first nuclear weapons project. The Maud Committee was set up following the work of Frisch and Rudolf Peierls who calculated uranium-235's critical mass and found it to be much smaller than previously thought which meant that a deliverable bomb should be possible.[16] In the February 1940 Frisch–Peierls memorandum they stated that: "The energy liberated in the explosion of such a super-bomb...will, for an instant, produce a temperature comparable to that of the interior of the sun. The blast from such an explosion would destroy life in a wide area. The size of this area is difficult to estimate, but it will probably cover the centre of a big city."

Edgar Sengier, a director of Shinkolobwe Mine in the Congo which produced by far the highest quality uranium ore in the world, had become aware of uranium's possible use in a bomb. In late 1940, fearing that it might be seized by the Germans, he shipped the mine's entire stockpile of ore to a warehouse in New York.[17]

For 18 months British research outpaced the American but by mid-1942, it became apparent that the industrial effort required was beyond Britain's already stretched wartime economy.[18]: 204

In September 1942, General Leslie Groves was appointed to lead the U.S. project which became known as the Manhattan Project. Two of his first acts were to obtain authorization to assign the highest priority AAA rating on necessary procurements, and to order the purchase of all 1,250 tons of the Shinkolobwe ore.[17][19] The Tube Alloys project was quickly overtaken by the U.S. effort and after Roosevelt and Churchill signed the Quebec Agreement in 1943, it was relocated and amalgamated into the Manhattan Project.[18] Canada provided uranium and plutonium for the project.[20]

Szilard started to acquire high-quality graphite and uranium, which were the necessary materials for building a large-scale chain reaction experiment. The Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago was tasked with the completion of such a reactor, and Fermi moved there, continuing the pile experiments he began at Columbia. After many subcritical designs, Chicago Pile-1 achieved criticality on December 2, 1942. The success of this demonstration and technological breakthrough were partially due to Szilard's new atomic theories, his uranium lattice design, and the identification and mitigation of a key graphite impurity (boron) through a joint collaboration with graphite suppliers.[21]

From Los Alamos to Hiroshima

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

The beginning of the American research about nuclear weapons (The Manhattan Project) started with the Einstein–Szilárd letter.

With a scientific team led by J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan project brought together some of the top scientific minds of the day, including exiles from Europe, with the production power of American industry for the goal of producing fission-based explosive devices before Germany. Britain and the U.S. agreed to pool their resources and information, but the main other Allied power, the Soviet Union (USSR), was not informed. The U.S. made a tremendous investment in the project, then the second largest industrial enterprise ever seen,[18] spread across more than 30 sites in the U.S. and Canada. Scientific development was centralized in a secret laboratory at Los Alamos.

For a fission weapon to operate, there must be sufficient fissile material to support a chain reaction, a critical mass. To separate the fissile uranium-235 isotope from the non-fissile uranium-238, two methods were developed which took advantage of the fact that uranium-238 has a slightly greater atomic mass: electromagnetic separation and gaseous diffusion. Another secret site was erected at rural Oak Ridge, Tennessee, for the large-scale production and purification of the rare isotope, which required considerable investment. At the time, K-25, one of the Oak Ridge facilities, was the world's largest factory under one roof. The Oak Ridge site employed tens of thousands of people at its peak, most of whom had no idea what they were working on.

Although uranium-238 cannot be used for the initial stage of an atomic bomb, when it absorbs a neutron, it becomes uranium-239 which decays into neptunium-239, and finally the relatively stable plutonium-239, which is fissile like uranium-235. This could then be chemically separated from the rest of the irradiated fuel, in a process far simpler than enrichment. Following the success of Chicago Pile-1 and 2, techniques for continuous reactor operation, plutonium production and separation were developed at the X-10 Graphite Reactor pilot plant in Oak Ridge from 1943. From 1944, the B, D, and F reactors were secretly constructed at what is now known as the Hanford Site, alongside large separation plants. Separate efforts to produce plutonium from heavy water reactors were pursued, with the P-9 Project producing the moderator and resulting in the 1944 test reactor Chicago Pile-3. Such reactors would only be used for plutonium production in the postwar Savannah River Site.

The simplest form of nuclear weapon is a gun-type fission weapon, where a sub-critical mass would be shot at another sub-critical mass. The result would be a super-critical mass and an uncontrolled chain reaction that would create the desired explosion. The weapons envisaged in 1942 were the two gun-type weapons, Little Boy (uranium) and Thin Man (plutonium), and the Fat Man plutonium implosion bomb.

In early 1943 Oppenheimer determined that two projects should proceed forwards: the Thin Man project (plutonium gun) and the Fat Man project (plutonium implosion). The plutonium gun was to receive the bulk of the research effort, as it was the project with the most uncertainty involved. It was assumed that the uranium gun-type bomb could then be adapted from it.

In December 1943 the British mission of 19 scientists arrived in Los Alamos. Hans Bethe became head of the Theoretical Division.

In April 1944 it was found by Emilio Segrè that the plutonium-239 produced by the Hanford reactors had too high a level of background neutron radiation, and underwent spontaneous fission to a very small extent, due to the unexpected presence of plutonium-240 impurities. If such plutonium were used in a gun-type design, the chain reaction would start in the split second before the critical mass was fully assembled, blowing the weapon apart with a much lower yield than expected, in what is known as a fizzle.

As a result, development of Fat Man was given high priority. Chemical explosives were used to implode a sub-critical sphere of plutonium, thus increasing its density and making it into a critical mass. The difficulties with implosion centered on the problem of making the chemical explosives deliver a perfectly uniform shock wave upon the plutonium sphere— if it were even slightly asymmetric, the weapon would fizzle. This problem was solved by the use of explosive lenses which would focus the blast waves inside the imploding sphere, akin to the way in which an optical lens focuses light rays.[22]

After D-Day, General Groves ordered a team of scientists to follow eastward-moving victorious Allied troops into Europe to assess the status of the German nuclear program (and to prevent the westward-moving Soviets from gaining any materials or scientific manpower). They concluded that, while Germany had a modest nuclear research program headed by Werner Heisenberg, the government had not made a significant investment in the project, and it had been nowhere near success.[citation needed] Similarly, Japan's efforts at developing a nuclear weapon were starved of resources. The Japanese navy lost interest when a committee led by Yoshio Nishina concluded in 1943 that "it would probably be difficult even for the United States to realize the application of atomic power during the war".[23]

Historians claim to have found a rough schematic showing a Nazi nuclear bomb.[24] In March 1945, a German scientific team was directed by the physicist Kurt Diebner to develop a primitive nuclear device in Ohrdruf, Thuringia.[24][25] Last ditch research was conducted in an experimental nuclear reactor at Haigerloch.

Decision to drop the bomb

[edit]On April 12, after Roosevelt's death, Vice President Harry S. Truman assumed the presidency. At the time of the unconditional surrender of Germany on May 8, 1945, the Manhattan Project was still months away from producing a working weapon.

Because of the difficulties in making a working plutonium bomb, it was decided that there should be a test of the weapon. On July 16, 1945, in the desert north of Alamogordo, New Mexico, the first nuclear test took place, code-named "Trinity", using a device nicknamed "the gadget." The test, a plutonium implosion-type device, released energy equivalent to 22 kilotons of TNT, far more powerful than any weapon ever used before. The news of the test's success was rushed to Truman at the Potsdam Conference, where Churchill was briefed and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin was informed of the new weapon. On July 26, the Potsdam Declaration was issued containing an ultimatum for Japan: either surrender or suffer "prompt and utter destruction", although nuclear weapons were not mentioned.[18]

After hearing arguments from scientists and military officers over the possible use of nuclear weapons against Japan (though some recommended using them as demonstrations in unpopulated areas, most recommended using them against built up targets, a euphemistic term for populated cities), Truman ordered the use of the weapons on Japanese cities. Under the clause of the 1943 Quebec Agreement that specified that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without mutual consent, the atomic bombing of Japan was recorded as a decision of the Anglo-American Combined Policy Committee.[26][27][28]

Truman hoped it would send a strong message that would end in the capitulation of the Japanese leadership and avoid a lengthy invasion of the islands. Truman and his Secretary of State James F. Byrnes were also intent on ending the Pacific war before the Soviets could enter it,[29] given that Roosevelt had promised Stalin control of Manchuria if he joined the invasion.[30] On May 10–11, 1945, the Target Committee at Los Alamos, led by Oppenheimer, recommended Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and Kokura as possible targets. Concerns about Kyoto's cultural heritage led to it being replaced by Nagasaki. In late July and early August 1945, a series of leaflets were dropped over several Japanese cities warning them of an imminent destructive attack (though not mentioning nuclear bombs).[31] Evidence suggests that these leaflets were never dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or were dropped too late,[32][33] although a testimony does contradict this.[34]

On August 6, 1945, a uranium-based weapon, Little Boy, was detonated above the Japanese city of Hiroshima, and three days later, a plutonium-based weapon, Fat Man, was detonated above the Japanese city of Nagasaki. To date, Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only two instances of nuclear weapons being used in combat. The atomic raids killed at least one hundred thousand Japanese civilians and military personnel outright, with the heat, radiation, and blast effects. Many tens of thousands would later die of radiation sickness and related cancers.[35][36] Truman promised a "rain of ruin" if Japan did not surrender immediately, threatening to systematically eliminate their ability to wage war.[37] On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan's surrender.[38]

Soviet atomic bomb project

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

The Soviet Union was not invited to share in the new weapons developed by the United States and the other Allies. During the war, information had been pouring in from a number of volunteer spies involved with the Manhattan Project (known in Soviet cables under the code-name of Enormoz), and the Soviet nuclear physicist Igor Kurchatov was carefully watching the Allied weapons development. It came as no surprise to Stalin when Truman had informed him at the Potsdam conference that he had a "powerful new weapon." Truman was shocked at Stalin's lack of interest. Stalin was nonetheless outraged by the situation, more by the Americans' guarded monopoly of the bomb than the weapon itself. Some historians share the assessment that Truman immediately authorized nuclear weapons as a "negotiating tool" in the early Cold War. In alarm at this monopoly, the Soviets urgently undertook their own atomic program.[29]

The Soviet spies in the U.S. project were all volunteers and none were Soviet citizens. One of the most valuable, Klaus Fuchs, was a German émigré theoretical physicist who had been part of the early British nuclear efforts and the UK mission to Los Alamos. Fuchs had been intimately involved in the development of the implosion weapon and passed on detailed cross-sections of the Trinity device to his Soviet contacts. Other Los Alamos spies—none of whom knew each other—included Theodore Hall and David Greenglass. The information was kept but not acted upon, as the Soviet Union was still too busy fighting the war in Europe to devote resources to this new project.

In the years immediately after World War II, the issue of who should control atomic weapons became a major international point of contention. Many of the Los Alamos scientists who had built the bomb began to call for "international control of atomic energy," often calling for either control by transnational organizations or the purposeful distribution of weapons information to all superpowers, but due to a deep distrust of the intentions of the Soviet Union, both in postwar Europe and in general, the policymakers of the United States worked to maintain the American nuclear monopoly.

A half-hearted plan for international control was proposed at the newly formed United Nations by Bernard Baruch (The Baruch Plan), but it was clear both to American commentators—and to the Soviets—that it was an attempt primarily to stymie Soviet nuclear efforts. The Soviets vetoed the plan, effectively ending any immediate postwar negotiations on atomic energy, and made overtures towards banning the use of atomic weapons in general.

The Soviets had put their full industrial might and manpower into the development of their own atomic weapons. The initial problem for the Soviets was primarily one of resources—they had not scouted out uranium resources in the Soviet Union and the U.S. had made deals to monopolise the largest known (and high purity) reserves in the Belgian Congo. The USSR used penal labour to mine the old deposits in Czechoslovakia—now an area under their control—and searched for other domestic deposits (which were eventually found).

Two days after the bombing of Nagasaki, the U.S. government released an official technical history of the Manhattan Project, authored by Princeton physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth, known colloquially as the Smyth Report. The sanitized summary of the wartime effort focused primarily on the production facilities and scale of investment, written in part to justify the wartime expenditure to the American public.

The Soviet program, under the suspicious watch of former NKVD chief Lavrenty Beria (a participant and victor in Stalin's Great Purge of the 1930s), would use the Report as a blueprint, seeking to duplicate as much as possible the American effort. The "secret cities" used for the Soviet equivalents of Hanford and Oak Ridge literally vanished from the maps for decades to come.

At the Soviet equivalent of Los Alamos, Arzamas-16, physicist Yuli Khariton led the scientific effort to develop the weapon. Beria distrusted his scientists, however, and he distrusted the carefully collected espionage information. As such, Beria assigned multiple teams of scientists to the same task without informing each team of the other's existence. If they arrived at different conclusions, Beria would bring them together for the first time and have them debate with their newfound counterparts. Beria used the espionage information as a way to double-check the progress of his scientists, and in his effort for duplication of the American project even rejected more efficient bomb designs in favor of ones that more closely mimicked the tried-and-true Fat Man bomb used by the U.S. against Nagasaki.[citation needed]

On August 29, 1949, the effort brought its results, when the USSR successfully tested its first fission bomb, dubbed "Joe-1" by the U.S.[39] The news of the first Soviet bomb was announced to the world first by the United States,[40] which had detected atmospheric radioactive traces generated from its test site in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic.[41]

The loss of the American monopoly on nuclear weapons marked the first tit-for-tat of the nuclear arms race.[42]

American developments after World War II

[edit]With the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, the U.S. Congress established the civilian Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to take over the development of nuclear weapons from the military, and to develop nuclear power.[43] The AEC made use of many private companies in processing uranium and thorium and in other urgent tasks related to the development of bombs. Many of these companies had very lax safety measures and employees were sometimes exposed to radiation levels far above what was allowed then or now.[44] (In 1974, the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (FUSRAP) of the Army Corps of Engineers was set up to deal with contaminated sites left over from these operations.[45])

The Atomic Energy Act also established the United States Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, which had broad legislative and executive oversight jurisdiction over nuclear matters and became one of the powerful congressional committees in U.S. history.[46] Its two early chairmen, Senator Brien McMahon and Senator Bourke Hickenlooper, both pushed for increased production of nuclear materials and a resultant increase in the American atomic stockpile.[47] The size of that stockpile, which had been low in the immediate postwar years,[48] was a closely guarded secret.[49] Indeed, within the U.S. government, including the Departments of State and Defense, there was considerable confusion over who actually knew the size of the stockpile, and some people chose not to know for fear they might disclose the number accidentally.[48]

First thermonuclear weapons

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

The notion of using a fission weapon to ignite a process of nuclear fusion can be dated back to September 1941, when it was first proposed by Enrico Fermi to his colleague Edward Teller during a discussion at Columbia University.[50] At the first major theoretical conference on the development of an atomic bomb hosted by J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley in the summer of 1942, Teller directed the majority of the discussion towards this idea of a "Super" bomb.

It was thought at the time that a fission weapon would be quite simple to develop and that perhaps work on a hydrogen bomb (thermonuclear weapon) would be possible to complete before the end of the Second World War. However, in reality the problem of a regular atomic bomb was large enough to preoccupy the scientists for the next few years, much less the more speculative "Super" bomb. Only Teller continued working on the project—against the will of project leaders Oppenheimer and Hans Bethe.

The Joe-1 atomic bomb test by the Soviet Union that took place in August 1949 came earlier than expected by Americans, and over the next several months there was an intense debate within the U.S. government, military, and scientific communities regarding whether to proceed with development of the far more powerful Super.[51]

After the atomic bombings of Japan, many scientists at Los Alamos rebelled against the notion of creating a weapon thousands of times more powerful than the first atomic bombs. For the scientists the question was in part technical—the weapon design was still quite uncertain and unworkable—and in part moral: such a weapon, they argued, could only be used against large civilian populations, and could thus only be used as a weapon of genocide.

Many scientists, such as Bethe, urged that the United States should not develop such weapons and set an example towards the Soviet Union. Promoters of the weapon, including Teller, Ernest Lawrence, and Luis Alvarez, argued that such a development was inevitable, and to deny such protection to the people of the United States—especially when the Soviet Union was likely to create such a weapon themselves—was itself an immoral and unwise act.

Oppenheimer, who was now head of the General Advisory Committee of the successor to the Manhattan Project, the Atomic Energy Commission, presided over a recommendation against the development of the weapon. The reasons were in part because the success of the technology seemed limited at the time (and not worth the investment of resources to confirm whether this was so), and because Oppenheimer believed that the atomic forces of the United States would be more effective if they consisted of many large fission weapons (of which multiple bombs could be dropped on the same targets) rather than the large and unwieldy super bombs, for which there was a relatively limited number of targets of sufficient size to warrant such a development.

What is more, if such weapons were developed by both superpowers, they would be more effective against the U.S. than against the USSR, as the U.S. had far more regions of dense industrial and civilian activity as targets for large weapons than the Soviet Union.

In the end, President Truman made the final decision, looking for a proper response to the first Soviet atomic bomb test in 1949. On January 31, 1950, Truman announced a crash program to develop the hydrogen (fusion) bomb. The exact mechanism was still not known: the classical hydrogen bomb, whereby the heat of the fission bomb would be used to ignite the fusion material, seemed highly unworkable. An insight by Los Alamos mathematician Stanislaw Ulam showed that the fission bomb and the fusion fuel could be in separate parts of the bomb, and that radiation of the fission could compress the fusion material before igniting it.

Teller pushed the notion further and used the results of the boosted-fission "George" test (a boosted-fission device using a small amount of fusion fuel to boost the yield of a fission bomb) to confirm the fusion of heavy hydrogen elements before preparing for their first true multi-stage, Teller-Ulam hydrogen bomb test. Many scientists, initially against the weapon, such as Oppenheimer and Bethe, changed their previous opinions, seeing the development as being unstoppable.

The first fusion bomb was tested by the United States in Operation Ivy on November 1, 1952, on Elugelab Island in the Enewetak (or Eniwetok) Atoll of the Marshall Islands, code-named "Mike." Mike used liquid deuterium as its fusion fuel and a large fission weapon as its trigger. The device was a prototype design and not a deliverable weapon: standing over 20 ft (6 m) high and weighing at least 140,000 lb (64 t) (its refrigeration equipment added an additional 24,000 lb (11,000 kg) as well), it could not have been dropped from even the largest planes.

Its explosion yielded energy equivalent to 10.4 megatons of TNT—over 450 times the power of the bomb dropped onto Nagasaki— and obliterated Elugelab, leaving an underwater crater 6240 ft (1.9 km) wide and 164 ft (50 m) deep where the island had once been. Truman had initially tried to create a media blackout about the test—hoping it would not become an issue in the upcoming presidential election—but on January 7, 1953, Truman announced the development of the hydrogen bomb to the world as hints and speculations of it were already beginning to emerge in the press.

Not to be outdone, the Soviet Union exploded its first thermonuclear device, designed by the physicist Andrei Sakharov, on August 12, 1953, labeled "Joe-4" by the West. This created concern within the U.S. government and military, because, unlike Mike, the Soviet device was a deliverable weapon, which the U.S. did not yet have. This first device though was arguably not a true hydrogen bomb and could only reach explosive yields in the hundreds of kilotons (never reaching the megaton range of a staged weapon). Still, it was a powerful propaganda tool for the Soviet Union, and the technical differences were fairly oblique to the American public and politicians.

Following the Mike blast by less than a year, Joe-4 seemed to validate claims that the bombs were inevitable and vindicate those who had supported the development of the fusion program. Coming during the height of McCarthyism, the effect was pronounced on the security hearings in early 1954, which revoked former Los Alamos director Robert Oppenheimer's security clearance on the grounds that he was unreliable, had not supported the American hydrogen bomb program, and had made long-standing left-wing ties in the 1930s. Edward Teller participated in the hearing as the only major scientist to testify against Oppenheimer, resulting in his virtual expulsion from the physics community.

On March 1, 1954, the U.S. detonated its first practical thermonuclear weapon (which used isotopes of lithium as its fusion fuel), known as the "Shrimp" device of the Castle Bravo test, at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands. The device yielded 15 megatons, more than twice its expected yield, and became the worst radiological disaster in U.S. history. The combination of the unexpectedly large blast and poor weather conditions caused a cloud of radioactive nuclear fallout to contaminate over 7,000 square miles (18,000 km2). 239 Marshall Island natives and 28 Americans were exposed to significant amounts of radiation, resulting in elevated levels of cancer and birth defects in the years to come.[52]

The crew of the Japanese tuna-fishing boat Lucky Dragon 5, who had been fishing just outside the exclusion zone, returned to port suffering from radiation sickness and skin burns; one crew member was terminally ill. Efforts were made to recover the cargo of contaminated fish but at least two large tuna were probably sold and eaten. A further 75 tons of tuna caught between March and December were found to be unfit for human consumption. When the crew member died and the full results of the contamination were made public by the U.S., Japanese concerns were reignited about the hazards of radiation.[53]

The hydrogen bomb age had a profound effect on the thoughts of nuclear war in the popular and military mind. With only fission bombs, nuclear war was something that possibly could be limited. Dropped by planes and only able to destroy the most built up areas of major cities, it was possible for many to look at fission bombs as a technological extension of large-scale conventional bombing—such as the extensive firebombing of German and Japanese cities during World War II. Proponents brushed aside as grave exaggeration claims that such weapons could lead to worldwide death or harm.

Even in the decades before fission weapons, there had been speculation about the possibility for human beings to end all life on the planet, either by accident or purposeful maliciousness—but technology had not provided the capacity for such action. The great power of hydrogen bombs made worldwide annihilation possible.

The Castle Bravo incident itself raised a number of questions about the survivability of a nuclear war. Government scientists in both the U.S. and the USSR had insisted that fusion weapons, unlike fission weapons, were cleaner, as fusion reactions did not produce the dangerously radioactive by-products of fission reactions. While technically true, this hid a more gruesome point: the last stage of a multi-staged hydrogen bomb often used the neutrons produced by the fusion reactions to induce fissioning in a jacket of natural uranium and provided around half of the yield of the device itself.

This fission stage made fusion weapons considerably dirtier than they were made out to be. This was evident in the towering cloud of deadly fallout that followed the Bravo test. When the Soviet Union tested its first megaton device in 1955, the possibility of a limited nuclear war seemed even more remote in the public and political mind. Even cities and countries that were not direct targets would suffer fallout contamination. Extremely harmful fission products would disperse via normal weather patterns and embed in soil and water around the planet.

Speculation began to run towards what fallout and dust from a full-scale nuclear exchange would do to the world as a whole, rather than just cities and countries directly involved. In this way, the fate of the world was now tied to the fate of the bomb-wielding superpowers.

Deterrence and brinkmanship

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Throughout the 1950s and the early 1960s the U.S. and the USSR both endeavored, in a tit-for-tat approach, to prevent the other power from acquiring nuclear supremacy. This had massive political and cultural effects during the Cold War. As one instance of this mindset, in the early 1950s it was proposed to drop a nuclear bomb on the Moon as a globally visible demonstration of American weaponry.[54]

The first atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively, were large, custom-made devices, requiring highly trained personnel for their arming and deployment. They could be dropped only from the largest bomber planes—at the time the B-29 Superfortress—and each plane could only carry a single bomb in its hold. The first hydrogen bombs were similarly massive and complicated. This ratio of one plane to one bomb was still fairly impressive in comparison with conventional, non-nuclear weapons, but against other nuclear-armed countries it was considered a grave danger.

In the immediate postwar years, the U.S. expended much effort on making the bombs "G.I.-proof"—capable of being used and deployed by members of the U.S. Army, rather than Nobel Prize–winning scientists. In the 1950s, the U.S. undertook a nuclear testing program to improve the nuclear arsenal.

Starting in 1951, the Nevada Test Site (in the Nevada desert) became the primary location for all U.S. nuclear testing (in the USSR, Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan served a similar role). Tests were divided into two primary categories: "weapons related" (verifying that a new weapon worked or looking at exactly how it worked) and "weapons effects." A detailed study about the effects of nuclear weapons can be read from S. Glasstone and P.J. Dolan. [55]

In the beginning, almost all nuclear tests were either atmospheric (conducted above ground, in the atmosphere) or underwater (such as some of the tests done in the Marshall Islands). Testing was used as a sign of both national and technological strength, but also raised questions about the safety of the tests, which released nuclear fallout into the atmosphere (most dramatically with the Castle Bravo test in 1954, but in more limited amounts with almost all atmospheric nuclear testing).

Because testing was seen as a sign of technological development (the ability to design usable weapons without some form of testing was considered dubious), halts on testing were often called for as stand-ins for halts in the nuclear arms race itself, and many prominent scientists and statesmen lobbied for a ban on nuclear testing. In 1958, the U.S., USSR, and the United Kingdom (a new nuclear power) declared a temporary testing moratorium for both political and health reasons, but by 1961 the Soviet Union had broken the moratorium and both the USSR, and the U.S. began testing with great frequency.

As a show of political strength, the Soviet Union tested the largest-ever nuclear weapon in October 1961, the massive Tsar Bomba, which was tested in a reduced state with a yield of around 50 megatons—in its full state it was estimated to have been around 100 Mt. The weapon was largely impractical for actual military use but was hot enough to induce third-degree burns at a distance of 62 mi (100 km) away. In its full, dirty, design it would have increased the amount of worldwide fallout since 1945 by 25%.

In 1963, all nuclear and many non-nuclear states signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, pledging to refrain from testing nuclear weapons in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. The treaty permitted underground tests.

Most tests were considerably more modest and worked for direct technical purposes as well as their potential political overtones. Weapons improvements took on two primary forms. One was an increase in efficiency and power, and within only a few years fission bombs were developed that were many times more powerful than the ones created during World War II. The other was a program of miniaturization, reducing the size of the nuclear weapons.

Smaller bombs meant that bombers could carry more of them, and also that they could be carried on the new generation of rockets in development in the 1950s and 1960s. U.S. rocket science received a large boost in the postwar years, largely with the help of engineers acquired from the Nazi rocketry program. These included scientists such as Wernher von Braun, who had helped design the V-2 rockets the Nazis launched across the English Channel. An American program, Project Paperclip, had endeavored to move German scientists into American hands (and away from Soviet hands) and put them to work for the U.S.

Weapons improvement

[edit]Early nuclear armed rockets—such as the MGR-1 Honest John, first deployed by the U.S. in 1953—were surface-to-surface missiles with relatively short ranges (around 15 mi/25 km maximum) and yields around twice the size of the first fission weapons. The limited range meant they could only be used in certain types of military situations. U.S. rockets could not, for example, threaten Moscow with an immediate strike, and could only be used as tactical weapons (that is, for small-scale military situations).

Strategic weapons—weapons that could threaten an entire country—relied, for the time being, on long-range bombers that could penetrate deep into enemy territory. In the U.S., this requirement led, in 1946, to creation of the Strategic Air Command—a system of bombers headed by General Curtis LeMay (who previously presided over the firebombing of Japan during WWII). In operations like Chrome Dome (1961–1968), SAC kept nuclear-armed planes in the air 24 hours a day, ready for an order to attack Moscow.

These technological possibilities enabled nuclear strategy to develop a logic considerably different from previous military thinking. Because the threat of nuclear warfare was so awful, it was first thought that it might make any war of the future impossible. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's doctrine of "massive retaliation" in the early years of the Cold War was a message to the USSR, saying that if the Red Army attempted to invade the parts of Europe not given to the Eastern bloc during the Potsdam Conference (such as West Germany), nuclear weapons would be used against the Soviet troops and potentially the Soviet leaders.

With the development of more rapid-response technologies (such as rockets and long-range bombers), this policy began to shift. If the Soviet Union also had nuclear weapons and a policy of "massive retaliation" was carried out, it was reasoned, then any Soviet forces not killed in the initial attack, or launched while the attack was ongoing, would be able to serve their own form of nuclear retaliation against the U.S. Recognizing that this was an undesirable outcome, military officers and game theorists at the RAND think tank developed a nuclear warfare strategy that was eventually called Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD).

MAD divided potential nuclear war into two stages: first strike and second strike. First strike meant the first use of nuclear weapons by one nuclear-equipped nation against another nuclear-equipped nation. If the attacking nation did not prevent the attacked nation from a nuclear response, the attacked nation would respond with a second strike against the attacking nation. In this situation, whether the U.S. first attacked the USSR, or the USSR first attacked the U.S., the result would be that both nations would be damaged to the point of utter social collapse.

According to game theory, because starting a nuclear war was suicidal, no logical country would shoot first. However, if a country could launch a first strike that utterly destroyed the target country's ability to respond, that might give that country the confidence to initiate a nuclear war. The object of a country operating by the MAD doctrine is to deny the opposing country this first strike capability.

MAD played on two seemingly opposed modes of thought: cold logic and emotional fear. The English phrase MAD was often known by, "nuclear deterrence," was translated by the French as "dissuasion," and "terrorization" by the Soviets. This apparent paradox of nuclear war was summed up by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill as "the worse things get, the better they are"—the greater the threat of mutual destruction, the safer the world would be.

This philosophy made a number of technological and political demands on participating nations. For one thing, it said that it should always be assumed that an enemy nation may be trying to acquire first strike capability, which must always be avoided. In American politics this translated into demands to avoid "bomber gaps" and "missile gaps" where the Soviet Union could potentially outshoot the Americans. It also encouraged the production of thousands of nuclear weapons by both the U.S. and the USSR, far more than needed to simply destroy the major civilian and military infrastructures of the opposing country. These policies and strategies were satirized in the 1964 Stanley Kubrick film Dr. Strangelove, in which the Soviets, unable to keep up with the US's first strike capability, instead plan for MAD by building a Doomsday Machine, and thus, after a (literally) mad US General orders a nuclear attack on the USSR, the end of the world is brought about.

The policy also encouraged the development of the first early warning systems. Conventional war, even at its fastest, was fought over days and weeks. With long-range bombers, from the start of a nuclear attack to its conclusion was mere hours. Rockets could reduce a conflict to minutes. Planners reasoned that conventional command and control systems could not adequately react to a nuclear attack, so great lengths were taken to develop computer systems that could look for enemy attacks and direct rapid responses.

The U.S. poured massive funding into development of SAGE, a system that could track and intercept enemy bomber aircraft using information from remote radar stations. It was the first computer system to feature real-time processing, multiplexing, and display devices. It was the first general computing machine, and a direct predecessor of modern computers.

-

The introduction of nuclear armed rockets, like the MGR-1 Honest John, reflected a change in both nuclear technology and strategy.

-

Long-range bomber aircraft, such as the B-52 Stratofortress, allowed deployment of a wide range of strategic nuclear weapons.

-

A SSM-N-8 Regulus is launched from USS Halibut; prior to the development of the SLBM, the United States employed submarines with Regulus cruise missiles in the submarine-based strategic deterrent role.

-

With early warning systems, it was thought that the strikes of nuclear war would come from dark rooms filled with computers, not the battlefield of the wars of old.

Emergence of the anti-nuclear movement

[edit]

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the end of World War II quickly followed the 1945 Trinity nuclear test, and the Little Boy device was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. Exploding with a yield equivalent to 12,500 tonnes of TNT, the blast and thermal wave of the bomb destroyed nearly 50,000 buildings and killed approximately 75,000 people.[56] Subsequently, the world's nuclear weapons stockpiles grew.[57]

Operation Crossroads was a series of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean in the summer of 1946. Its purpose was to test the effect of nuclear weapons on naval ships. To prepare the Bikini atoll for the nuclear tests, Bikini's native residents were evicted from their homes and resettled on smaller, uninhabited islands where they were unable to sustain themselves.[58]

National leaders debated the impact of nuclear weapons on domestic and foreign policy. Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs.[59] Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when a Hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific contaminated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon. One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later. The incident caused widespread concern around the world and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[60] The anti-nuclear weapons movement grew rapidly because for many people the atomic bomb "encapsulated the very worst direction in which society was moving".[61]

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to the Pacific nuclear weapons tests was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[61] The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London on July 9, 1955, by Bertrand Russell in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. The signatories included eleven pre-eminent intellectuals and scientists, including Albert Einstein, who signed it just days before his death on April 18, 1955. A few days after the release, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton offered to sponsor a conference—called for in the manifesto—in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Eaton's birthplace. This conference was to be the first of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, held in July 1957.

In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament took place at Easter 1958, when several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.[62][63] The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches.[61]

In 1959, a letter in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was the start of a successful campaign to stop the Atomic Energy Commission dumping radioactive waste in the sea 19 kilometres from Boston.[64] On November 1, 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons. It was the largest national women's peace protest of the 20th century.[65][66]

In 1958, Linus Pauling and his wife presented the United Nations with the petition signed by more than 11,000 scientists calling for an end to nuclear-weapon testing. The "Baby Tooth Survey," headed by Dr Louise Reiss, demonstrated conclusively in 1961 that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout spread primarily via milk from cows that had ingested contaminated grass.[67][68][69] Public pressure and the research results subsequently led to a moratorium on above-ground nuclear weapons testing, followed by the Partial Test Ban Treaty, signed in 1963 by John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev.[59][70][71]

Cuban Missile Crisis

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Bombers and short-range rockets were not reliable: planes could be shot down, and earlier nuclear missiles could cover only a limited range— for example, the first Soviet rockets' range limited them to targets in Europe. However, by the 1960s, both the United States and the Soviet Union had developed intercontinental ballistic missiles, which could be launched from extremely remote areas far away from their target. They had also developed submarine-launched ballistic missiles, which had less range but could be launched from submarines very close to the target without any radar warning. This made any national protection from nuclear missiles increasingly impractical.

The military realities made for a precarious diplomatic situation. The international politics of brinkmanship led leaders to exclaim their willingness to participate in a nuclear war rather than concede any advantage to their opponents, feeding public fears that their generation may be the last. Civil defense programs undertaken by both superpowers, exemplified by the construction of fallout shelters and urging civilians about the survivability of nuclear war, did little to ease public concerns.

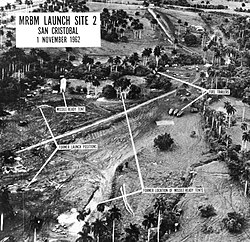

The climax of brinksmanship came in early 1962, when an American U-2 spy plane photographed a series of launch sites for medium-range ballistic missiles being constructed on the island of Cuba, just off the coast of the southern United States, beginning what became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. The U.S. administration of John F. Kennedy concluded that the Soviet Union, then led by Nikita Khrushchev, was planning to station Soviet nuclear missiles on the island (as a response to placing US Jupiter MRBMs in Italy and Turkey), which was under the control of communist Fidel Castro. On October 22, Kennedy announced the discoveries in a televised address. He announced a naval blockade around Cuba that would turn back Soviet nuclear shipments and warned that the military was prepared "for any eventualities." The missiles had 2,400 mile (4,000 km) range and would allow the Soviet Union to quickly destroy many major American cities on the Eastern Seaboard if a nuclear war began.

The leaders of the two superpowers stood nose to nose, seemingly poised over the beginnings of a third world war. Khrushchev's ambitions for putting the weapons on the island were motivated in part by the fact that the U.S. had stationed similar weapons in Britain, Italy, and nearby Turkey, and had previously attempted to sponsor an invasion of Cuba the year before in the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion. On October 26, Khrushchev sent a message to Kennedy offering to withdraw all missiles if Kennedy committed to a policy of no future invasions of Cuba. Khrushchev worded the threat of assured destruction eloquently:

You and I should not now pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied a knot of war, because the harder you and I pull, the tighter the knot will become. And a time may come when this knot is tied so tight that the person who tied it is no longer capable of untying it, and then the knot will have to be cut. What that would mean I need not explain to you, because you yourself understand perfectly what dreaded forces our two countries possess.

A day later, however, the Soviets sent another message, this time demanding that the U.S. remove its missiles from Turkey before any missiles were withdrawn from Cuba. On the same day, a U-2 plane was shot down over Cuba and another almost intercepted over the Soviet Union, as Soviet merchant ships neared the quarantine zone. Kennedy responded by accepting the first deal publicly and sending his brother Robert to the Soviet embassy to accept the second deal privately. On October 28, the Soviet ships stopped at the quarantine line and, after some hesitation, turned back towards the Soviet Union. Khrushchev announced that he had ordered the removal of all missiles in Cuba, and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk was moved to comment, "We went eyeball to eyeball, and the other fellow just blinked."

The Crisis was later seen as the closest the U.S. and the USSR ever came to nuclear war and had been narrowly averted by last-minute compromise by both superpowers. Fears of communication difficulties led to the installment of the first hotline, a direct link between the superpowers that allowed them to more easily discuss future military activities and political maneuverings. It had been made clear that missiles, bombers, submarines, and computerized firing systems made escalating any situation to Armageddon far easier than anybody desired.

After stepping so close to the brink, both the U.S. and the USSR worked to reduce their nuclear tensions in the years immediately following. The most immediate culmination of this work was the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, in which the U.S. and USSR agreed to no longer test nuclear weapons in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. Testing underground continued, allowing for further weapons development, but the worldwide fallout risks were purposefully reduced, and the era of using massive nuclear tests as a form of saber rattling ended.

In December 1979, NATO decided to deploy cruise and Pershing II missiles in Western Europe in response to Soviet deployment of intermediate range mobile missiles, and in the early 1980s, a "dangerous Soviet-US nuclear confrontation" arose.[72] In New York on June 12, 1982, one million people gathered to protest about nuclear weapons, and to support the second UN Special Session on Disarmament.[73][74] As the nuclear abolitionist movement grew, there were many protests at the Nevada Test Site. For example, on February 6, 1987, nearly 2,000 demonstrators, including six members of Congress, protested against nuclear weapons testing and more than 400 people were arrested.[75] Four of the significant groups organizing this renewal of anti-nuclear activism were Greenpeace, The American Peace Test, The Western Shoshone, and Nevada Desert Experience.

There have been at least four major false alarms, the most recent in 1995, that resulted in the activation of nuclear attack early warning protocols. They include the accidental loading of a training tape into the American early-warning computers; a computer chip failure that appeared to show a random number of attacking missiles; a rare alignment of the Sun, the U.S. missile fields and a Soviet early warning satellite that caused it to confuse high-altitude clouds with missile launches; the launch of a Norwegian research rocket resulted in President Yeltsin activating his nuclear briefcase for the first time.[76]

Initial proliferation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

In the fifties and sixties, three more countries joined the "nuclear club." The United Kingdom had been an integral part of the Manhattan Project following the Quebec Agreement in 1943. The passing of the McMahon Act by the United States in 1946 unilaterally broke this partnership and prevented the passage of any further information to the United Kingdom. The British Government, under Clement Attlee, determined that a British Bomb was essential. Because of British involvement in the Manhattan Project, Britain had extensive knowledge in some areas, but not in others.

An improved version of 'Fat Man' was developed, and on 26 February 1952, Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced that the United Kingdom had an atomic bomb and a successful test took place on 3 October 1952. At first these were free-fall bombs, intended for use by the V Force of jet bombers. A Vickers Valiant dropped the first UK nuclear weapon on 11 October 1956 at Maralinga, South Australia. Later came a missile, Blue Steel, intended for carriage by the V Force bombers, and then the Blue Streak medium-range ballistic missile (later canceled). Anglo-American cooperation on nuclear weapons was restored by the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement. As a result of this and the Polaris Sales Agreement, the United Kingdom has bought United States designs for submarine missiles and fitted its own warheads. It retains full independent control over the use of the missiles. It no longer possesses any free-fall bombs.

France had been heavily involved in nuclear research before World War II through the work of the Joliot-Curies. This was discontinued after the war because of the instability of the Fourth Republic and lack of finances.[77] However, in the 1950s, France launched a civil nuclear research program, which produced plutonium as a byproduct.

In 1956, France formed a secret Committee for the Military Applications of Atomic Energy and a development program for delivery vehicles. With the return of Charles de Gaulle to the French presidency in 1958, final decisions to build a bomb were made, which led to a successful test in 1960. Since then, France has developed and maintained its own nuclear deterrent independent of NATO.

In 1951, China and the Soviet Union signed an agreement whereby China supplied uranium ore in exchange for technical assistance in producing nuclear weapons. In 1953, China established a research program under the guise of civilian nuclear energy. Throughout the 1950s the Soviet Union provided large amounts of equipment. But as the relations between the two countries worsened the Soviets reduced the amount of assistance and, in 1959, refused to donate a bomb for copying purposes. Despite this, the Chinese made rapid progress. Chinese first gained possession of nuclear weapons in 1964, making it the fifth country to have them. It tested its first atomic bomb at Lop Nur on October 16, 1964 (Project 596); and tested a nuclear missile on October 25, 1966; and tested a thermonuclear (hydrogen) bomb (Test No. 6) on June 14, 1967. China ultimately conducted a total of 45 nuclear tests; although the country has never become a signatory to the Limited Test Ban Treaty, it conducted its last nuclear test in 1996. In the 1980s, China's nuclear weapons program was a source of nuclear proliferation, as China transferred its CHIC-4 technology to Pakistan. China became a party to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) as a nuclear weapon state in 1992, and the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) in 2004.[78] As of 2017, the number of Chinese warheads is thought to be in the low hundreds,[79] The Atomic Heritage Foundation notes a 2018 estimate of approximately 260 nuclear warheads, including between 50 and 60 ICBMs and four nuclear submarines.[78] China declared a policy of "no first use" in 1964, the only nuclear weapons state to announce such a policy; this declaration has no effect on its capabilities and there are no diplomatic means of verifying or enforcing this declaration.[80]

Cold War

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

After World War II, the balance of power between the Eastern and Western blocs and the fear of global destruction prevented the further military use of atomic bombs. This fear was even a central part of Cold War strategy, referred to as the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction. So important was this balance to international political stability that a treaty, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (or ABM treaty), was signed by the U.S. and the USSR in 1972 to curtail the development of defenses against nuclear weapons and the ballistic missiles that carry them. This doctrine resulted in a large increase in the number of nuclear weapons, as each side sought to ensure it possessed the firepower to destroy the opposition in all possible scenarios.

Early delivery systems for nuclear devices were primarily bombers like the United States B-29 Superfortress and Convair B-36, and later the B-52 Stratofortress. Ballistic missile systems, based on Wernher von Braun's World War II designs (specifically the V-2 rocket), were developed by both United States and Soviet Union teams (in the case of the U.S., effort was directed by the German scientists and engineers although the Soviet Union also made extensive use of captured German scientists, engineers, and technical data).

These systems were used to launch satellites, such as Sputnik, and to propel the Space Race, but they were primarily developed to create Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) that could deliver nuclear weapons anywhere on the globe. Development of these systems continued throughout the Cold War—though plans and treaties, beginning with the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I), restricted deployment of these systems until, after the fall of the Soviet Union, system development essentially halted, and many weapons were disabled and destroyed. On January 27, 1967, more than 60 nations signed the Outer Space Treaty, banning nuclear weapons in space.

There have been a number of potential nuclear disasters. Following air accidents U.S. nuclear weapons have been lost near Atlantic City, New Jersey (1957); Savannah, Georgia (1958) (see Tybee Bomb); Goldsboro, North Carolina (1961); off the coast of Okinawa (1965); in the sea near Palomares, Spain (1966) (see 1966 Palomares B-52 crash); and near Thule Air Base, Greenland (1968) (see 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash). Most of the lost weapons were recovered, the Spanish device after three months' effort by the DSV Alvin and DSV Aluminaut. Investigative journalist Eric Schlosser discovered that at least 700 "significant" accidents and incidents involving 1,250 nuclear weapons were recorded in the United States between 1950 and 1968.[81]

The Soviet Union was less forthcoming about such incidents, but the environmental group Greenpeace believes that there are around forty non-U.S. nuclear devices that have been lost and not recovered, compared to eleven lost by America, mostly in submarine disasters.[82] The U.S. has tried to recover Soviet devices, notably in the 1974 Project Azorian using the specialist salvage vessel Hughes Glomar Explorer to raise a Soviet submarine. After news leaked out about this boondoggle, the CIA would coin a favorite phrase for refusing to disclose sensitive information, called glomarization: We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested but, hypothetically, if such data were to exist, the subject matter would be classified, and could not be disclosed.[83]

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 essentially ended the Cold War. However, the end of the Cold War failed to end the threat of nuclear weapon use, although global fears of nuclear war reduced substantially. In a major move of symbolic de-escalation, Boris Yeltsin, on January 26, 1992, announced that Russia planned to stop targeting United States cities with nuclear weapons.

Cost

[edit]The designing, testing, producing, deploying, and defending against nuclear weapons is one of the largest expenditures for the nations which possess nuclear weapons. In the United States during the Cold War years, between "one quarter to one third of all military spending since World War II [was] devoted to nuclear weapons and their infrastructure."[84] According to a retrospective Brookings Institution study published in 1998 by the Nuclear Weapons Cost Study Committee (formed in 1993 by the W. Alton Jones Foundation), the total expenditures for U.S. nuclear weapons from 1940 to 1998 was $5.5 trillion in 1996 dollars.[85]

For comparison, the total public debt at the end of fiscal year 1998 was $5,478,189,000,000 in 1998 dollars[86] or $5.3 trillion. The entire public debt in 1998 was therefore equal to the cost of research, development, and deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons-related programs during the Cold War.[84][85][87]

Second nuclear age

[edit]

The second nuclear age can be regarded as proliferation of nuclear weapons among lesser powers and for reasons other than the American-Soviet-Chinese rivalry.

India embarked relatively early on a program aimed at nuclear weapons capability, but apparently accelerated this after the 1962 Sino-Indian War. India's first atomic-test explosion was in 1974 with Smiling Buddha, which it described as a "peaceful nuclear explosion."

After the collapse of Eastern Military High Command and the disintegration of Pakistan as a result of the 1971 Winter war, Pakistan's Bhutto launched scientific research on nuclear weapons. The Indian test caused Pakistan to spur its programme, and the ISI conducted successful espionage operations in the Netherlands, while also developing the programme indigenously. India tested fission, and perhaps, fusion devices in 1998, and Pakistan successfully tested fission devices that same year, raising concerns they would use nuclear weapons on each other.

All the non-Russian former Soviet bloc countries with nuclear weapons - Belarus, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan - transferred their warheads to Russia by 1996.

South Africa had an active program to develop uranium-based nuclear weapons but dismantled its nuclear weapon program in the 1990s.[88] Experts do not believe it actually tested such a weapon, though it later claimed it constructed crude devices that it eventually dismantled. In the late 1970s American spy satellites detected a "brief, intense, double flash of light near the southern tip of Africa."[89] Known as the Vela incident, it was speculated to have been a South African or possibly Israeli nuclear weapons test, though some feel that it may have been caused by natural events or a detector malfunction.

Israel is widely believed to possess an arsenal of up to several hundred nuclear warheads, but this has never been officially confirmed or denied (though the existence of their Dimona nuclear facility was confirmed by Mordechai Vanunu in 1986). Key US scientists involved in the American bomb program, clandestinely helped the Israelis and thus played an important role in nuclear proliferation, one was Edward Teller.[citation needed]

In January 2004, Dr A. Q. Khan of Pakistan's programme confessed to having been a key mover in "proliferation activities",[90] seen as part of an international proliferation network of materials, knowledge, and machines from Pakistan to Libya, Iran, and North Korea.

North Korea announced in 2003 that it had several nuclear explosives. The first claimed detonation was the 2006 North Korean nuclear test, conducted on October 9, 2006. On May 25, 2009, North Korea continued nuclear testing, violating United Nations Security Council Resolution 1718. A third test was conducted on 13 February 2013, two tests were conducted in 2016 in January and September, followed by test a year later in September 2017.

As part of the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances in 1994,[91] the country of Ukraine surrendered its nuclear arsenal, left over from the USSR, in part on the promise that its borders would remain respected if it did so. In 2022 during the prelude to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin, as he had lightly done in the past, alleged that Ukraine was on the path to receiving nuclear weapons. According to Putin, there was a "real danger" that Western allies could help supply Ukraine, which appeared to be on the path to joining NATO, with nuclear arms. Critics labelled Putin's claims as "conspiracy theories" designed to build a case for an invasion of Ukraine.[92]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Canada's little-known contributions to the atomic bomb, Tyler Dawson, National Post, July 24, 2023.

- ^ Tannenwald, Nina. "'Limited' Tactical Nuclear Weapons Would Be Catastrophic". Scientific American. Retrieved April 10, 2025.

- ^ Young-Brown, F. (2016). Nuclear Fusion and Fission. Great Discoveries in Science. Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-502-61949-5.

- ^ Polanyi, John (November 5, 2022). "We have to believe in a world without war – and science should lead the way". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

Wells ... had read the record of research ... by Ernest Rutherford, and was aware that atoms could break apart. In this finding, he saw the ultimate weapon of war. He named the weapon an "atom bomb."

- ^ Alkon, Paul Kent (2006). Winston Churchill's Imagination. Associated University Presse. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-838-75632-4.

- ^ L'Annunziata, Michael F. (2007). Radioactivity: Introduction and History. Elsevier. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-080-54888-3.

- ^ L'Annunziata, Michael F. (2016). Radioactivity: Introduction and History, From the Quantum to Quarks. Elsevier. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-444-63496-2.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 263, 268.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, p. 268.

- ^ "Leo Szilard | Biographies". www.atomicarchive.com.

- ^ Anderson, H.L.; Booth, E.T.; Dunning, J.R.; Fermi, E.; Glasoe, G.N.; Slack, F.G. (1839). "The Fission of Uranium". Physical Review. 55 (5): 511–512. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.511.2. Institutional citation: Pupin Physics Laboratories Columbia University New York, New York (Received: February 16, 1939)

- ^ Rhodes 1986, p. 267.

- ^ Bendjebbar (2000). Histoire secrète de la bombe atomique française. Cherche Midi. p. 403. ISBN 978-2-86274-794-1.

- ^ Rhodes 1986, pp. 305–312.

- ^ Herrera, Geoffrey Lucas (2006). Technology and International Transformation: The Railroad, the Atom Bomb, and the Politics of Technological Change. SUNY Press. pp. 179–80. ISBN 978-0-7914-6868-5.

- ^ Laucht, Christoph (2012). Elemental Germans: Klaus Fuchs, Rudolf Peierls and the Making of British Nuclear Culture 1939–59. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-137-22295-4.

- ^ a b Groves, Leslie R. (1983). Now It Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. Da Capo Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-786-74822-8.

- ^ a b c d Best, Geoffrey (November 15, 2006). Churchill and War. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-85285-541-3.

- ^ Jones, Vincent C. (December 1, 1985). Manhattan, the Army and the Atomic Bomb. United States Government Publishing Office. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-16-087288-4.

- ^ "Canada's historical role in developing nuclear weapons". Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission. February 3, 2014.

- ^ "Leo Szilard - Nuclear Museum". June 30, 2023. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023.

- ^ Hoddeson, Lillian; Henriksen, Paul W.; Meade, Roger A.; Westfall, Catherine L. (February 12, 2004). Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945. Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-521-54117-6.

- ^ Burns & Siracusa 2013, pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b Drawing uncovered of 'Nazi nuke'. BBC.com. Wednesday, 1 June 2005, 13:11 GMT 14:11 UK.

- ^ "Hitler 'tested small atom bomb'". BBC News. March 14, 2005.

- ^ Gowing 1964, p. 372.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 372–373.

- ^ "Minutes of a Meeting of the Combined Policy Committee, Washington, July 4, 1945". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on September 18, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Todd, Allan (2015). History for the IB Diploma Paper 2: The Cold War. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-107-55632-4.

- ^ Leffler, Melvyn P.; Westad, Odd Arne (March 25, 2010). The Cambridge History of the Cold War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-521-83719-4.

- ^ "Warning Leaflets". Atomic Heritage Foundation. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- ^ "A Day Too Late".

- ^ "The Hiroshima leaflet".

- ^ "Survivors of the Atomic Bomb Share Their Stories". Time. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Rezelman, David; Gosling, F.G.; Fehner, Terrence R. (2000). "The atomic bombing of Hiroshima". The Manhattan Project: An Interactive History. U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on September 11, 2007. page on Hiroshima casualties.

- ^ The Spirit of Hiroshima: An Introduction to the Atomic Bomb Tragedy. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. 1999.

- ^ "First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan; Missile Is Equal to 20,000 Tons of TNT; Truman Warns Foe of a 'Rain of Ruin'". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ "Japan surrenders". History channel. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ Holloway 1995, pp. 215–218.

- ^ Young & Schilling 2019, p. 21.

- ^ Holloway 1995, p. 213.

- ^ Rhodes 1995, p. 24.

- ^ Young & Schilling 2019, p. 3.

- ^ "Poisoned Workers & Poisoned Places", USA Today, June 24, 2001.

- ^ FUSRAP Chronology at Internet Archive.

- ^ Young & Schilling 2019, pp. 4, 33.

- ^ Rhodes 1995, pp. 279–280.

- ^ a b Young & Schilling 2019, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Bundy 1988, pp. 199–201.

- ^ Rhodes 1995, p. 207.

- ^ Young & Schilling 2019, pp. 1–2.

- ^ "The Marshall Islands: Tropical idylls scarred like Tohoku". The Japan Times. June 10, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ "Lucky Dragon's lethal catch". March 18, 2012. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2013.

- ^ Hargitai, Henrik; Naß, Andrea (2019). "Planetary Mapping: A Historical Overview". In Hargitai, Henrik (ed.). Planetary Cartography and GIS. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography. Springer International Publishing. pp. 27–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-62849-3_2. ISBN 978-3-319-62849-3. S2CID 86546344.

- ^ Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip J. (1979). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons. The United States Department of Defense and the United States Department of Energy.

- ^ Emsley, John (2001). "Chapter: Uranium". Nature's Building Blocks: An A to Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. p. 476. ISBN 978-0-198-50340-8.

- ^ Palevsky, Mary; Futrell, Robert; Kirk, Andrew (2005). "Recollections of Nevada's Nuclear Past" (PDF). Unlv Fusion: 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Niedenthal, Jack (2008). "A Short History of the People of Bikini Atoll". BikiniAtoll.com. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Rudig, Wolfgang (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy. Longman. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-0-582-90269-5.

- ^ a b c Falk 1982, pp. 96–97.

- ^ "A brief history of CND". CNDUK.org.

- ^ "Early defections in march to Aldermaston". Guardian Unlimited. April 5, 1958.