Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Packet switching

View on Wikipedia

In telecommunications, packet switching is a method of grouping data into short messages in fixed format, i.e., packets, that are transmitted over a telecommunications network. Packets consist of a header and a payload. Data in the header is used by networking hardware to direct the packet to its destination, where the payload is extracted and used by an operating system, application software, or higher layer protocols. Packet switching is the primary basis for data communications in computer networks worldwide.

During the early 1960s, American engineer Paul Baran developed a concept he called distributed adaptive message block switching as part of a research program at the RAND Corporation, funded by the United States Department of Defense. His proposal was to provide a fault-tolerant, efficient method for communication of voice messages using low-cost hardware to route the message blocks across a distributed network. His ideas contradicted then-established principles of pre-allocation of network bandwidth, exemplified by the development of telecommunications in the Bell System. The new concept found little resonance among network implementers until the independent work of Welsh computer scientist Donald Davies at the National Physical Laboratory beginning in 1965. Davies developed the concept for data communication using software switches in a high-speed computer network and coined the term packet switching. His work inspired numerous packet switching networks in the decade following, including the incorporation of the concept into the design of the ARPANET in the United States and the CYCLADES network in France. The ARPANET and CYCLADES were the primary precursor networks of the modern Internet.

Concept

[edit]A simple definition of packet switching is:

The routing and transferring of data by means of addressed packets so that a channel is occupied during the transmission of the packet only, and upon completion of the transmission the channel is made available for the transfer of other traffic.[4][5]

Packet switching allows delivery of variable bit rate data streams, realized as sequences of short messages in fixed format, i.e. packets, over a computer network which allocates transmission resources as needed using statistical multiplexing or dynamic bandwidth allocation techniques. As they traverse networking hardware, such as switches and routers, packets are received, buffered, queued, and retransmitted (stored and forwarded), resulting in variable latency and throughput depending on the link capacity and the traffic load on the network. Packets are normally forwarded by intermediate network nodes asynchronously using first-in, first-out buffering, but may be forwarded according to some scheduling discipline for fair queuing, traffic shaping, or for differentiated or guaranteed quality of service, such as weighted fair queuing or leaky bucket. Packet-based communication may be implemented with or without intermediate forwarding nodes (switches and routers). In case of a shared physical medium (such as radio or 10BASE5), the packets may be delivered according to a multiple access scheme.

Packet switching contrasts with another principal networking paradigm, circuit switching, a method which pre-allocates dedicated network bandwidth specifically for each communication session, each having a constant bit rate and latency between nodes. In cases of billable services, such as cellular communication services, circuit switching is characterized by a fee per unit of connection time, even when no data is transferred, while packet switching may be characterized by a fee per unit of information transmitted, such as characters, packets, or messages.

A packet switch has four components: input ports, output ports, routing processor, and switching fabric.[6]

History

[edit]Invention and development

[edit]

The concept of switching small blocks of data was first invented independently by Paul Baran at the RAND Corporation during the early 1960s in the US and Donald Davies at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in the UK in 1965.[1][2][3][10]

In the late 1950s, the US Air Force established a wide area network for the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) radar defense system. Recognizing vulnerabilities in this network, the Air Force sought a system that might survive a nuclear attack to enable a response, thus diminishing the attractiveness of the first strike advantage by enemies (see Mutual assured destruction). In the early 1960s, Baran invented the concept of distributed adaptive message block switching in support of the Air Force initiative.[11][12] The concept was first presented to the Air Force in the summer of 1961 as briefing B-265,[13] later published as RAND report P-2626 in 1962,[7] and finally in report RM 3420 in 1964.[8] The reports describe a general architecture for a large-scale, distributed, survivable communications network. The proposal was composed of three key ideas: use of a decentralized network with multiple paths between any two points; dividing user messages into message blocks; and delivery of these messages by store and forward switching.[11][14] Baran's network design was focused on digital communication of voice messages using hardware switches that were low-cost electronics.[15][16][17] The ideas were not entirely original to Baran and the task to design a store and forward type of network was formulated by Baran's boss at RAND.[18]

Christopher Strachey, who became Oxford University's first Professor of Computation, filed a patent application in the United Kingdom for time-sharing in February 1959.[19][20] In June that year, he gave a paper "Time Sharing in Large Fast Computers" at the UNESCO Information Processing Conference in Paris where he passed the concept on to J. C. R. Licklider.[21][22] Licklider (along with John McCarthy) was instrumental in the development of time-sharing. After conversations with Licklider about time-sharing with remote computers in 1965,[23][24] Davies independently invented a similar data communication concept.[25] His insight was to use short messages in fixed format with high data transmission rates to achieve rapid communications.[26] He went on to develop a more advanced design for a hierarchical, high-speed computer network including interface computers and communication protocols.[27][28][29] He coined the term packet switching, and proposed building a commercial nationwide data network in the UK.[30][31] He gave a talk on the proposal in 1966, after which a person from the Ministry of Defence (MoD) told him about Baran's work.[32]

Roger Scantlebury, a member of Davies' team, presented their work (and referenced that of Baran) at the October 1967 Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP).[29][33][34][35][36] At the conference, Scantlebury proposed packet switching for use in the ARPANET and persuaded Larry Roberts the economics were favorable to message switching.[37][38][39][40][41][42] Davies had chosen some of the same parameters for his original network design as did Baran, such as a packet size of 1024 bits. To deal with packet permutations (due to dynamically updated route preferences) and datagram losses (unavoidable when fast sources send to a slow destinations), he assumed that "all users of the network will provide themselves with some kind of error control",[29] thus inventing what came to be known as the end-to-end principle. Davies proposed that a local-area network should be built at the laboratory to serve the needs of NPL and prove the feasibility of packet switching. After a pilot experiment in early 1969,[43][44][45][46] the NPL Data Communications Network began service in 1970.[47] Davies was invited to Japan to give a series of lectures on packet switching.[48] The NPL team carried out simulation work on datagrams and congestion in networks on a scale to provide data communication across the United Kingdom.[46][49][50][51][52]

Larry Roberts made the key decisions in the request for proposal to build the ARPANET.[53] Roberts met Baran in February 1967, but did not discuss networks.[54][55] He asked Frank Westervelt to explore the questions of message size and contents for the network, and to write a position paper on the intercomputer communication protocol including “conventions for character and block transmission, error checking and re transmission, and computer and user identification."[56] Roberts revised his initial design, which was to connect the host computers directly, to incorporate Wesley Clark's idea to use Interface Message Processors (IMPs) to create a message switching network, which he presented at SOSP.[57][58][59][60] Roberts was known for making decisions quickly.[61] Immediately after SOSP, he incorporated Davies' and Baran's concepts and designs for packet switching to enable the data communications on the network.[39][62][63][64]

A contemporary of Roberts' from MIT, Leonard Kleinrock had researched the application of queueing theory in the field of message switching for his doctoral dissertation in 1961–62 and published it as a book in 1964.[65] Davies, in his 1966 paper on packet switching,[27] applied Kleinorck's techniques to show that "there is an ample margin between the estimated performance of the [packet-switched] system and the stated requirement" in terms of a satisfactory response time for a human user.[66] This addressed a key question about the viability of computer networking.[67] Larry Roberts brought Kleinrock into the ARPANET project informally in early 1967.[68] Roberts and Taylor recognized the issue of response time was important, but did not apply Kleinrock's methods to assess this and based their design on a store-and-forward system that was not intended for real-time computing.[69] After SOSP, and after Roberts' direction to use packet switching,[62] Kleinrock sought input from Baran and proposed to retain Baran and RAND as advisors.[70][71][72] The ARPANET working group assigned Kleinrock responsibility to prepare a report on software for the IMP.[73] In 1968, Roberts awarded Kleinrock a contract to establish a Network Measurement Center (NMC) at UCLA to measure and model the performance of packet switching in the ARPANET.[70]

Bolt Beranek & Newman (BBN) won the contract to build the network. Designed principally by Bob Kahn,[74][75] it was the first wide-area packet-switched network with distributed control.[53] The BBN "IMP Guys" independently developed significant aspects of the network's internal operation, including the routing algorithm, flow control, software design, and network control.[76][77] The UCLA NMC and the BBN team also investigated network congestion.[74][78] The Network Working Group, led by Steve Crocker, a graduate student of Kleinrock's at UCLA, developed the host-to-host protocol, the Network Control Program, which was approved by Barry Wessler for ARPA,[79] after he ordered certain more exotic elements to be dropped.[80] In 1970, Kleinrock extended his earlier analytic work on message switching to packet switching in the ARPANET.[81] His work influenced the development of the ARPANET and packet-switched networks generally.[82][83][84]

The ARPANET was demonstrated at the International Conference on Computer Communication (ICCC) in Washington in October 1972.[85][86] However, fundamental questions about the design of packet-switched networks remained.[87][88][89]

Roberts presented the idea of packet switching to communication industry professionals in the early 1970s. Before ARPANET was operating, they argued that the router buffers would quickly run out. After the ARPANET was operating, they argued packet switching would never be economic without the government subsidy. Baran had faced the same rejection and thus failed to convince the military into constructing a packet switching network in the 1960s.[9]

The CYCLADES network was designed by Louis Pouzin in the early 1970s to study internetworking.[90][91][92] It was the first to implement the end-to-end principle of Davies, and make the host computers responsible for the reliable delivery of data on a packet-switched network, rather than this being a service of the network itself.[93] His team was thus first to tackle the highly-complex problem of providing user applications with a reliable virtual circuit service while using a best-effort service, an early contribution to what will be the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP).[94]

Bob Metcalfe and others at Xerox PARC outlined the idea of Ethernet and the PARC Universal Packet (PUP) for internetworking.[95]

In May 1974, Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn described the Transmission Control Program, an internetworking protocol for sharing resources using packet-switching among the nodes.[96] The specifications of the TCP were then published in RFC 675 (Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program), written by Vint Cerf, Yogen Dalal and Carl Sunshine in December 1974.[97]

The X.25 protocol, developed by Rémi Després and others, was built on the concept of virtual circuits. In the mid-late 1970s and early 1980s, national and international public data networks emerged using X.25 which was developed with participation from France, the UK, Japan, USA and Canada. It was complemented with X.75 to enable internetworking.[98]

Packet switching was shown to be optimal in the Huffman coding sense in 1978.[99][100]

In the late 1970s, the monolithic Transmission Control Program was layered as the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), atop the Internet Protocol (IP). Many Internet pioneers developed this into the Internet protocol suite and the associated Internet architecture and governance that emerged in the 1980s.[101][102][103][104][105][106]

For a period in the 1980s and early 1990s, the network engineering community was polarized over the implementation of competing protocol suites, commonly known as the Protocol Wars. It was unclear which of the Internet protocol suite and the OSI model would result in the best and most robust computer networks.[107][108][109]

Leonard Kleinrock carried out theoretical work at UCLA during the 1970s analyzing throughput and delay in the ARPANET.[110][111][112] His theoretical work on hierarchical routing with student Farouk Kamoun became critical to the operation of the Internet.[113][114] Kleinrock published hundreds of research papers,[115][116] which ultimately launched a new field of research on the theory and application of queuing theory to computer networks.[81][117]

Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) VLSI (very-large-scale integration) technology led to the development of high-speed broadband packet switching during the 1980s–1990s.[118][119][120]

The "paternity dispute"

[edit]Roberts claimed in later years that, by the time of the October 1967 SOSP, he already had the concept of packet switching in mind (although not yet named and not written down in his paper published at the conference, which a number of sources describe as "vague"), and that this originated with his old colleague, Kleinrock, who had written about such concepts in his Ph.D. research in 1961-2.[59][37][60][121][122] In 1997, along with seven other Internet pioneers, Roberts and Kleinrock co-wrote "Brief History of the Internet" published by the Internet Society.[123] In it, Kleinrock is described as having "published the first paper on packet switching theory in July 1961 and the first book on the subject in 1964". Many sources about the history of the Internet began to reflect these claims as uncontroversial facts. This became the subject of what Katie Hafner called a "paternity dispute" in The New York Times in 2001.[124]

The disagreement about Kleinrock's contribution to packet switching dates back to a version of the above claim made on Kleinrock's profile on the UCLA Computer Science department website sometime in the 1990s. Here, he was referred to as the "Inventor of the Internet Technology".[125] The webpage's depictions of Kleinrock's achievements provoked anger among some early Internet pioneers.[126] The dispute over priority became a public issue after Donald Davies posthumously published a paper in 2001 in which he denied that Kleinrock's work was related to packet switching. Davies also described ARPANET project manager Larry Roberts as supporting Kleinrock, referring to Roberts' writings online and Kleinrock's UCLA webpage profile as "very misleading".[127][128] Walter Isaacson wrote that Kleinrock's claims "led to an outcry among many of the other Internet pioneers, who publicly attacked Kleinrock and said that his brief mention of breaking messages into smaller pieces did not come close to being a proposal for packet switching".[126]

Davies' paper reignited a previous dispute over who deserves credit for getting the ARPANET online between engineers at Bolt, Beranek, and Newman (BBN) who had been involved in building and designing the ARPANET IMP on the one side, and ARPA-related researchers on the other.[76][77] This earlier dispute is exemplified by BBN's Will Crowther, who in a 1990 oral history described Paul Baran's packet switching design (which he called hot-potato routing), as "crazy" and non-sensical, despite the ARPA team having advocated for it.[129] The reignited debate caused other former BBN employees to make their concerns known, including Alex McKenzie, who followed Davies in disputing that Kleinrock's work was related to packet switching, stating "... there is nothing in the entire 1964 book that suggests, analyzes, or alludes to the idea of packetization".[130]

Former IPTO director Bob Taylor also joined the debate, stating that "authors who have interviewed dozens of Arpanet pioneers know very well that the Kleinrock-Roberts claims are not believed".[131] Walter Isaacson notes that "until the mid-1990s Kleinrock had credited [Baran and Davies] with coming up with the idea of packet switching".[126]

A subsequent version of Kleinrock's biography webpage was copyrighted in 2009 by Kleinrock.[132] He was called on to defend his position over subsequent decades.[133] In 2023, he acknowledged that his published work in the early 1960s was about message switching and claimed he was thinking about packet switching.[134] Primary sources and historians recognize Baran and Davies for independently inventing the concept of digital packet switching used in modern computer networking including the ARPANET and the Internet.[1][2][39][135][136]

Kleinrock has received many awards for his ground-breaking applied mathematical research on packet switching, carried out in the 1970s, which was an extension of his pioneering work in the early 1960s on the optimization of message delays in communication networks.[81][137] However, Kleinrock's claims that his work in the early 1960s originated the concept of packet switching and that his work was a source of the packet switching concepts used in the ARPANET have affected sources on the topic, which has created methodological challenges in the historiography of the Internet.[124][126][128][133] Historian Andrew L. Russell said "'Internet history' also suffers from a ... methodological, problem: it tends to be too close to its sources. Many Internet pioneers are alive, active, and eager to shape the histories that describe their accomplishments. Many museums and historians are equally eager to interview the pioneers and to publicize their stories".[138]

Connectionless and connection-oriented modes

[edit]Packet switching may be classified into connectionless packet switching, also known as datagram switching, and connection-oriented packet switching, also known as virtual circuit switching. Examples of connectionless systems are Ethernet, IP, and the User Datagram Protocol (UDP). Connection-oriented systems include X.25, Frame Relay, Multiprotocol Label Switching (MPLS), and TCP.

In connectionless mode each packet is labeled with a destination address, source address, and port numbers. It may also be labeled with the sequence number of the packet. This information eliminates the need for a pre-established path to help the packet find its way to its destination, but means that more information is needed in the packet header, which is therefore larger. The packets are routed individually, sometimes taking different paths resulting in out-of-order delivery. At the destination, the original message may be reassembled in the correct order, based on the packet sequence numbers. Thus a virtual circuit carrying a byte stream is provided to the application by a transport layer protocol, although the network only provides a connectionless network layer service.

Connection-oriented transmission requires a setup phase to establish the parameters of communication before any packet is transferred. The signaling protocols used for setup allow the application to specify its requirements and discover link parameters. Acceptable values for service parameters may be negotiated. The packets transferred may include a connection identifier rather than address information and the packet header can be smaller, as it only needs to contain this code and any information, such as length, timestamp, or sequence number, which is different for different packets. In this case, address information is only transferred to each node during the connection setup phase, when the route to the destination is discovered and an entry is added to the switching table in each network node through which the connection passes. When a connection identifier is used, routing a packet requires the node to look up the connection identifier in a table.[citation needed]

Connection-oriented transport layer protocols such as TCP provide a connection-oriented service by using an underlying connectionless network. In this case, the end-to-end principle dictates that the end nodes, not the network itself, are responsible for the connection-oriented behavior.

Packet switching in networks

[edit]In telecommunication networks, packet switching is used to optimize the usage of channel capacity and increase robustness.[60] Compared to circuit switching, packet switching is highly dynamic, allocating channel capacity based on usage instead of explicit reservations. This can reduce wasted capacity caused by underutilized reservations at the cost of removing bandwidth guarantees. In practice, congestion control is generally used in IP networks to dynamically negotiate capacity between connections. Packet switching may also increase the robustness of networks in the face of failures. If a node fails, connections do not need to be interrupted, as packets may be routed around the failure.

Packet switching is used in the Internet and most local area networks. The Internet is implemented by the Internet Protocol Suite using a variety of link layer technologies. For example, Ethernet and Frame Relay are common. Newer mobile phone technologies (e.g., GSM, LTE) also use packet switching. Packet switching is associated with connectionless networking because, in these systems, no connection agreement needs to be established between communicating parties prior to exchanging data.

X.25, the international CCITT standard of 1976, is a notable use of packet switching in that it provides to users a service of flow-controlled virtual circuits. These virtual circuits reliably carry variable-length packets with data order preservation. DATAPAC in Canada was the first public network to support X.25, followed by TRANSPAC in France.[139]

Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) is another virtual circuit technology. It differs from X.25 in that it uses small fixed-length packets (cells), and that the network imposes no flow control to users.

Technologies such as MPLS and the Resource Reservation Protocol (RSVP) create virtual circuits on top of datagram networks. MPLS and its predecessors, as well as ATM, have been called "fast packet" technologies. MPLS, indeed, has been called "ATM without cells".[140] Virtual circuits are especially useful in building robust failover mechanisms and allocating bandwidth for delay-sensitive applications.

Packet-switched networks

[edit]Donald Davies' work in the late 1960s on data communications and computer network design became well known in the United States, Europe and Japan.[48][141][142][143] It was the "cornerstone" that inspired numerous packet switching networks in the decade following.[144][145][146][147]

The history of packet-switched networks can be divided into three overlapping eras: early networks before the introduction of X.25; the X.25 era when many postal, telephone, and telegraph (PTT) companies provided public data networks with X.25 interfaces; and the Internet era which initially competed with the OSI model.[148][149][150]

Early networks

[edit]Research into packet switching at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) began with a proposal for a wide-area network in 1965,[23] and a local-area network in 1966.[151] ARPANET funding was secured in 1966 by Bob Taylor, and planning began in 1967 when he hired Larry Roberts. The NPL network followed by the ARPANET became operational in 1969, the first two networks to use packet switching.[44][45] Larry Roberts said many of the packet switching networks built in the 1970s were similar "in nearly all respects" to Donald Davies' original 1965 design.[147] The ARPANET and Louis Pouzin's CYCLADES were the primary precursor networks of the modern Internet.[93] CYCLADES, unlike ARPANET, was explicitly designed to research internetworking.[90]

Before the introduction of X.25 in 1976,[152] about twenty different network technologies had been developed. Two fundamental differences involved the division of functions and tasks between the hosts at the edge of the network and the network core. In the datagram system, operating according to the end-to-end principle, the hosts have the responsibility to ensure orderly delivery of packets. In the virtual call system, the network guarantees sequenced delivery of data to the host. This results in a simpler host interface but complicates the network. The X.25 protocol suite uses this network type.

AppleTalk

[edit]AppleTalk is a proprietary suite of networking protocols developed by Apple in 1985 for Apple Macintosh computers. It was the primary protocol used by Apple devices through the 1980s and 1990s. AppleTalk included features that allowed local area networks to be established ad hoc without the requirement for a centralized router or server. The AppleTalk system automatically assigned addresses, updated the distributed namespace, and configured any required inter-network routing. It was a plug-n-play system.[153][154]

AppleTalk implementations were also released for the IBM PC and compatibles, and the Apple IIGS. AppleTalk support was available in most networked printers, especially laser printers, some file servers and routers.

The protocol was designed to be simple, autoconfiguring, and not require servers or other specialized services to work. These benefits also created drawbacks, as Appletalk tended not to use bandwidth efficiently. AppleTalk support was terminated in 2009.[153][155]

ARPANET

[edit]The ARPANET was a progenitor network of the Internet and one of the first networks, along with ARPA's SATNET, to run the TCP/IP suite using packet switching technologies.

BNRNET

[edit]BNRNET was a network which Bell-Northern Research developed for internal use. It initially had only one host but was designed to support many hosts. BNR later made major contributions to the CCITT X.25 project.[156]

Cambridge Ring

[edit]The Cambridge Ring was an experimental ring network developed at the Computer Laboratory, University of Cambridge. It operated from 1974 until the 1980s.

CompuServe

[edit]CompuServe developed its own packet switching network, implemented on DEC PDP-11 minicomputers acting as network nodes that were installed throughout the US (and later, in other countries) and interconnected. Over time, the CompuServe network evolved into a complicated multi-tiered network incorporating ATM, Frame Relay, IP and X.25 technologies.

CYCLADES

[edit]The CYCLADES packet switching network was a French research network designed and directed by Louis Pouzin. First demonstrated in 1973, it was developed to explore alternatives to the early ARPANET design and to support network research generally. It was the first network to use the end-to-end principle and make the hosts responsible for reliable delivery of data, rather than the network itself. Concepts of this network influenced later ARPANET architecture.[157][158]

DECnet

[edit]DECnet is a suite of network protocols created by Digital Equipment Corporation, originally released in 1975 in order to connect two PDP-11 minicomputers.[159] It evolved into one of the first peer-to-peer network architectures, thus transforming DEC into a networking powerhouse in the 1980s. Initially built with three layers, it later (1982) evolved into a seven-layer OSI-compliant networking protocol. The DECnet protocols were designed entirely by Digital Equipment Corporation. However, DECnet Phase II (and later) were open standards with published specifications, and several implementations were developed outside DEC, including one for Linux.

DDX-1

[edit]DDX-1 was an experimental network from Nippon PTT. It mixed circuit switching and packet switching. It was succeeded by DDX-2.[160]

EIN

[edit]The European Informatics Network (EIN), originally called COST 11, was a project beginning in 1971 to link networks in Britain, France, Italy, Switzerland and Euratom. Six other European countries also participated in the research on network protocols. Derek Barber directed the project, and Roger Scantlebury led the UK technical contribution; both were from NPL.[161][162][163][164] The contract for its implementation was awarded to an Anglo French consortium led by the UK systems house Logica and Sesa and managed by Andrew Karney. Work began in 1973 and it became operational in 1976 including nodes linking the NPL network and CYCLADES.[165] Barber proposed and implemented a mail protocol for EIN.[166] The transport protocol of the EIN helped to launch the INWG and X.25 protocols.[167][168][169] EIN was replaced by Euronet in 1979.[170]

EPSS

[edit]The Experimental Packet Switched Service (EPSS) was an experiment of the UK Post Office Telecommunications. It was the first public data network in the UK when it began operating in 1976.[171] Ferranti supplied the hardware and software. The handling of link control messages (acknowledgements and flow control) was different from that of most other networks.[172][173][174]

GEIS

[edit]As General Electric Information Services (GEIS), General Electric was a major international provider of information services. The company originally designed a telephone network to serve as its internal (albeit continent-wide) voice telephone network.

In 1965, at the instigation of Warner Sinback, a data network based on this voice-phone network was designed to connect GE's four computer sales and service centers (Schenectady, New York, Chicago, and Phoenix) to facilitate a computer time-sharing service.

After going international some years later, GEIS created a network data center near Cleveland, Ohio. Very little has been published about the internal details of their network. The design was hierarchical with redundant communication links.[175][176]

IPSANET

[edit]IPSANET was a semi-private network constructed by I. P. Sharp Associates to serve their time-sharing customers. It became operational in May 1976.[177]

IPX/SPX

[edit]The Internetwork Packet Exchange (IPX) and Sequenced Packet Exchange (SPX) are Novell networking protocols from the 1980s derived from Xerox Network Systems' IDP and SPP protocols, respectively which date back to the 1970s. IPX/SPX was used primarily on networks using the Novell NetWare operating systems.[178]

Merit Network

[edit]Merit Network, an independent nonprofit organization governed by Michigan's public universities,[179] was formed in 1966 as the Michigan Educational Research Information Triad to explore computer networking between three of Michigan's public universities as a means to help the state's educational and economic development.[180] With initial support from the State of Michigan and the National Science Foundation (NSF), the packet-switched network was first demonstrated in December 1971 when an interactive host-to-host connection was made between the IBM mainframe systems at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and Wayne State University in Detroit.[181] In October 1972, connections to the CDC mainframe at Michigan State University in East Lansing completed the triad. Over the next several years, in addition to host-to-host interactive connections, the network was enhanced to support terminal-to-host connections, host-to-host batch connections (remote job submission, remote printing, batch file transfer), interactive file transfer, gateways to the Tymnet and Telenet public data networks, X.25 host attachments, gateways to X.25 data networks, Ethernet attached hosts, and eventually TCP/IP; additionally, public universities in Michigan joined the network.[181][182] All of this set the stage for Merit's role in the NSFNET project starting in the mid-1980s.

NPL

[edit]Donald Davies of the National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom) designed and proposed a national commercial data network based on packet switching in 1965.[183][184] The proposal was not taken up nationally but the following year, he designed a local network using "interface computers", today known as routers, to serve the needs of NPL and prove the feasibility of packet switching.[185]

By 1968 Davies had begun building the NPL network to meet the needs of the multidisciplinary laboratory and prove the technology under operational conditions.[186][46][187] In 1969, the NPL, followed by the ARPANET, were the first two networks to use packet switching.[188][45] By 1976, 12 computers and 75 terminal devices were attached,[189] and more were added until the network was replaced in 1986. NPL was the first to use high-speed links.[190][191][192]

Octopus

[edit]Octopus was a local network at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. It connected sundry hosts at the lab to interactive terminals and various computer peripherals including a bulk storage system.[193][194][195]

Philips Research

[edit]Philips Research Laboratories in Redhill, Surrey developed a packet switching network for internal use. It was a datagram network with a single switching node.[196]

PUP

[edit]PARC Universal Packet (PUP or Pup) was one of the two earliest internetworking protocol suites; it was created by researchers at Xerox PARC in the mid-1970s. The entire suite provided routing and packet delivery, as well as higher level functions such as a reliable byte stream, along with numerous applications. Further developments led to Xerox Network Systems (XNS).[197]

RCP

[edit]RCP was an experimental network created by the French PTT. It was used to gain experience with packet switching technology before the specification of the TRANSPAC public network was frozen. RCP was a virtual-circuit network in contrast to CYCLADES which was based on datagrams. RCP emphasised terminal-to-host and terminal-to-terminal connection; CYCLADES was concerned with host-to-host communication. RCP influenced the X.25 specification, which was deployed on TRANSPAC and other public data networks.[198][199][200]

RETD

[edit]Red Especial de Transmisión de Datos (RETD) was a network developed by Compañía Telefónica Nacional de España. It became operational in 1972 and thus was the first public network.[201][202][203][204]

SCANNET

[edit]"The experimental packet-switched Nordic telecommunication network SCANNET was implemented in Nordic technical libraries in the 1970s, and it included first Nordic electronic journal Extemplo. Libraries were also among first ones in universities to accommodate microcomputers for public use in the early 1980s."[205]

SITA HLN

[edit]SITA is a consortium of airlines. Its High Level Network (HLN) became operational in 1969. Although organised to act like a packet-switching network,[23] it still used message switching.[206][18] As with many non-academic networks, very little has been published about it.

SRCnet/SERCnet

[edit]A number of computer facilities serving the Science Research Council (SRC) community in the United Kingdom developed beginning in the early 1970s. Each had their own star network (ULCC London, UMRCC Manchester, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory). There were also regional networks centred on Bristol (on which work was initiated in the late 1960s) followed in the mid-late 1970s by Edinburgh, the Midlands and Newcastle. These groups of institutions shared resources to provide better computing facilities than could be afforded individually. The networks were each based on one manufacturer's standards and were mutually incompatible and overlapping.[207][208][209] In 1981, the SRC was renamed the Science and Engineering Research Council (SERC). In the early 1980s a standardisation and interconnection effort started, hosted on an expansion of the SERCnet research network and based on the Coloured Book protocols, later evolving into JANET.[210][211][212]

Systems Network Architecture

[edit]Systems Network Architecture (SNA) is IBM's proprietary networking architecture created in 1974. An IBM customer could acquire hardware and software from IBM and lease private lines from a common carrier to construct a private network.[213]

Telenet

[edit]Telenet was the first FCC-licensed public data network in the United States. Telenet was incorporated in 1973 and started operations in 1975. It was founded by Bolt Beranek & Newman with Larry Roberts as CEO as a means of making packet switching technology public. Telenet initially used a proprietary Virtual circuit host interface, but changed it to X.25 and the terminal interface to X.29 after their standardization in CCITT.[89] It went public in 1979 and was then sold to GTE.[214][215]

Tymnet

[edit]Tymnet was an international data communications network headquartered in San Jose, CA. In 1969, it began install a network based on minicomputers to connect timesharing terminals to its central computers. The network used store-and-forward and voice-grade lines. Routing was not distributed, rather it was established by a central supervisor on a call-by-call basis.[23]

X.25 era

[edit]

There were two kinds of X.25 networks. Some such as DATAPAC and TRANSPAC were initially implemented with an X.25 external interface. Some older networks such as TELENET and TYMNET were modified to provide an X.25 host interface in addition to older host connection schemes. DATAPAC was developed by Bell-Northern Research which was a joint venture of Bell Canada (a common carrier) and Northern Telecom (a telecommunications equipment supplier). Northern Telecom sold several DATAPAC clones to foreign PTTs including the Deutsche Bundespost. X.75 and X.121 allowed the interconnection of national X.25 networks.

AUSTPAC

[edit]AUSTPAC was an Australian public X.25 network operated by Telstra. Established by Telstra's predecessor Telecom Australia in the early 1980s, AUSTPAC was Australia's first public packet-switched data network and supported applications such as on-line betting, financial applications—the Australian Taxation Office made use of AUSTPAC—and remote terminal access to academic institutions, who maintained their connections to AUSTPAC up until the mid-late 1990s in some cases. Access was via a dial-up terminal to a PAD, or, by linking a permanent X.25 node to the network.[216]

ConnNet

[edit]ConnNet was a network operated by the Southern New England Telephone Company serving the state of Connecticut.[217][218] Launched on March 11, 1985, it was the first local public packet-switched network in the United States.[219]

Datanet 1

[edit]Datanet 1 was the public switched data network operated by the Dutch PTT Telecom (now known as KPN). Strictly speaking Datanet 1 only referred to the network and the connected users via leased lines (using the X.121 DNIC 2041), the name also referred to the public PAD service Telepad (using the DNIC 2049). And because the main Videotex service used the network and modified PAD devices as infrastructure the name Datanet 1 was used for these services as well.[220]

DATAPAC

[edit]DATAPAC was the first operational X.25 network (1976).[221] It covered major Canadian cities and was eventually extended to smaller centers.[citation needed]

Datex-P

[edit]Deutsche Bundespost operated the Datex-P national network in Germany. The technology was acquired from Northern Telecom.[222]

Eirpac

[edit]Eirpac is the Irish public switched data network supporting X.25 and X.28. It was launched in 1984, replacing Euronet. Eirpac is run by Eircom.[223][224][225]

Euronet

[edit]Nine member states of the European Economic Community contracted with Logica and the French company SESA to set up a joint venture in 1975 to undertake the Euronet development, using X.25 protocols to form virtual circuits. It was to replace EIN and established a network in 1979 linking a number of European countries until 1984 when the network was handed over to national PTTs.[226][227]

HIPA-NET

[edit]Hitachi designed a private network system for sale as a turnkey package to multi-national organizations.[when?] In addition to providing X.25 packet switching, message switching software was also included. Messages were buffered at the nodes adjacent to the sending and receiving terminals. Switched virtual calls were not supported, but through the use of logical ports an originating terminal could have a menu of pre-defined destination terminals.[228]

Iberpac

[edit]Iberpac is the Spanish public packet-switched network, providing X.25 services. It was based on RETD which was operational since 1972. Iberpac was run by Telefonica.[229]

IPSS

[edit]In 1978, X.25 provided the first international and commercial packet-switching network, the International Packet Switched Service (IPSS).

JANET

[edit]JANET was the UK academic and research network, linking all universities, higher education establishments, and publicly funded research laboratories following its launch in 1984.[230] The X.25 network, which used the Coloured Book protocols, was based mainly on GEC 4000 series switches, and ran X.25 links at up to 8 Mbit/s in its final phase before being converted to an IP-based network in 1991. The JANET network grew out of the 1970s SRCnet, later called SERCnet.[231]

PSS

[edit]Packet Switch Stream (PSS) was the Post Office Telecommunications (later to become British Telecom) national X.25 network with a DNIC of 2342. British Telecom renamed PSS Global Network Service (GNS), but the PSS name has remained better known. PSS also included public dial-up PAD access, and various InterStream gateways to other services such as Telex.

REXPAC

[edit]REXPAC was the nationwide experimental packet switching data network in Brazil, developed by the research and development center of Telebrás, the state-owned public telecommunications provider.[232]

SITA Data Transport Network

[edit]SITA is a consortium of airlines. Its Data Transport Network adopted X.25 in 1981, becoming the world's most extensive packet-switching network.[233][234][235] As with many non-academic networks, very little has been published about it.

TRANSPAC

[edit]TRANSPAC was the national X.25 network in France.[139] It was developed locally at about the same time as DATAPAC in Canada. The development was done by the French PTT and influenced by its preceding experimental network RCP.[236] It began operation in 1978, and served commercial users and, after Minitel began, consumers.[237]

Tymnet

[edit]Tymnet utilized virtual call packet switched technology including X.25, SNA/SDLC, BSC and ASCII interfaces to connect host computers (servers) at thousands of large companies, educational institutions, and government agencies. Users typically connected via dial-up connections or dedicated asynchronous serial connections. The business consisted of a large public network that supported dial-up users and a private network business that allowed government agencies and large companies (mostly banks and airlines) to build their own dedicated networks. The private networks were often connected via gateways to the public network to reach locations not on the private network. Tymnet was also connected to dozens of other public networks in the U.S. and internationally via X.25/X.75 gateways.[238][239]

UNINETT

[edit]UNINETT was a wide-area Norwegian packet-switched network established through a joint effort between Norwegian universities, research institutions and the Norwegian Telecommunication administration. The original network was based on X.25; Internet protocols were adopted later.[240]

VENUS-P

[edit]VENUS-P was an international X.25 network that operated from April 1982 through March 2006. At its subscription peak in 1999, VENUS-P connected 207 networks in 87 countries.[241]

XNS

[edit]Xerox Network Systems (XNS) was a protocol suite promulgated by Xerox, which provided routing and packet delivery, as well as higher-level functions such as a reliable stream, and remote procedure calls. It was developed from PARC Universal Packet (PUP).[242][243]

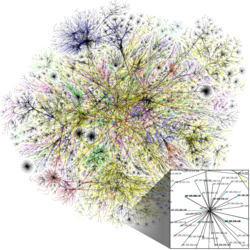

Internet era

[edit]| Internet |

|---|

|

|

|

When Internet connectivity was made available to anyone who could pay for an Internet service provider subscription, the distinctions between national networks blurred. The user no longer saw network identifiers such as the DNIC. Some older technologies such as circuit switching have resurfaced with new names such as fast packet switching. Researchers have created some experimental networks to complement the existing Internet.[244]

CSNET

[edit]The Computer Science Network (CSNET) was a computer network funded by the NSF that began operation in 1981. Its purpose was to extend networking benefits for computer science departments at academic and research institutions that could not be directly connected to ARPANET due to funding or authorization limitations. It played a significant role in spreading awareness of, and access to, national networking and was a major milestone on the path to the development of the global Internet.[245][246]

Internet2

[edit]Internet2 is a not-for-profit United States computer networking consortium led by members from the research and education communities, industry, and government.[247] The Internet2 community, in partnership with Qwest, built the first Internet2 Network, called Abilene, in 1998 and was a prime investor in the National LambdaRail (NLR) project.[248] In 2006, Internet2 announced a partnership with Level 3 Communications to launch a brand new nationwide network, boosting its capacity from 10 to 100 Gbit/s.[249] In October, 2007, Internet2 officially retired Abilene and now refers to its new, higher capacity network as the Internet2 Network.

NSFNET

[edit]

The National Science Foundation Network (NSFNET) was a program of coordinated, evolving projects sponsored by the NSF beginning in 1985 to promote advanced research and education networking in the United States.[250] NSFNET was also the name given to several nationwide backbone networks, operating at speeds of 56 kbit/s, 1.5 Mbit/s (T1), and 45 Mbit/s (T3), that were constructed to support NSF's networking initiatives from 1985 to 1995. Initially created to link researchers to the nation's NSF-funded supercomputing centers, through further public funding and private industry partnerships it developed into a major part of the Internet backbone.

NSFNET regional networks

[edit]In addition to the five NSF supercomputer centers, NSFNET provided connectivity to eleven regional networks and through these networks to many smaller regional and campus networks in the United States. The NSFNET regional networks were:[251][252]

- BARRNet, the Bay Area Regional Research Network in Palo Alto, California;

- CERFnet, California Education and Research Federation Network in San Diego, California, serving California and Nevada;

- CICNet, the Committee on Institutional Cooperation Network via the Merit Network in Ann Arbor, Michigan and later as part of the T3 upgrade via Argonne National Laboratory outside of Chicago, serving the Big Ten Universities and the University of Chicago in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin;

- Merit/MichNet in Ann Arbor, Michigan serving Michigan, formed in 1966,[253] still in operation as of 2023[update];[254]

- MIDnet in Lincoln, Nebraska serving Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and South Dakota;

- NEARNET, the New England Academic and Research Network in Cambridge, Massachusetts, added as part of the upgrade to T3, serving Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont, established in late 1988, operated by BBN under contract to MIT, BBN assumed responsibility for NEARNET on 1 July 1993;[255]

- NorthWestNet in Seattle, Washington, serving Alaska, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, Oregon, and Washington, founded in 1987;[256]

- NYSERNet, New York State Education and Research Network in Ithaca, New York;

- JVNCNet, the John von Neumann National Supercomputer Center Network in Princeton, New Jersey, serving Delaware and New Jersey;

- SESQUINET, the Sesquicentennial Network in Houston, Texas, founded during the 150th anniversary of the State of Texas;

- SURAnet, the Southeastern Universities Research Association network in College Park, Maryland and later as part of the T3 upgrade in Atlanta, Georgia serving Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, sold to BBN in 1994; and

- Westnet in Salt Lake City, Utah and Boulder, Colorado, serving Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming.

National LambdaRail

[edit]The National LambdaRail (NRL) was launched in September 2003. It is a 12,000-mile high-speed national computer network owned and operated by the US research and education community that runs over fiber-optic lines. It was the first transcontinental 10 Gigabit Ethernet network. It operates with an aggregate capacity of up to 1.6 Tbit/s and a 40 Gbit/s bitrate.[257][258] NLR ceased operations in March 2014.

TransPAC2, and TransPAC3

[edit]TransPAC2 is a high-speed international Internet service connecting research and education networks in the Asia-Pacific region to those in the US.[259] TransPAC3 is part of the NSF's International Research Network Connections (IRNC) program.[260]

Very high-speed Backbone Network Service (vBNS)

[edit]The Very high-speed Backbone Network Service (vBNS) came on line in April 1995 as part of a NSF sponsored project to provide high-speed interconnection between NSF-sponsored supercomputing centers and select access points in the United States.[261] The network was engineered and operated by MCI Telecommunications under a cooperative agreement with the NSF. By 1998, the vBNS had grown to connect more than 100 universities and research and engineering institutions via 12 national points of presence with DS-3 (45 Mbit/s), OC-3c (155 Mbit/s), and OC-12 (622 Mbit/s) links on an all OC-12 backbone, a substantial engineering feat for that time. The vBNS installed one of the first ever production OC-48 (2.5 Gbit/s) IP links in February 1999 and went on to upgrade the entire backbone to OC-48.[262]

In June 1999 MCI WorldCom introduced vBNS+ which allowed attachments to the vBNS network by organizations that were not approved by or receiving support from NSF.[263] After the expiration of the NSF agreement, the vBNS largely transitioned to providing service to the government. Most universities and research centers migrated to the Internet2 educational backbone. In January 2006, when MCI and Verizon merged,[264] vBNS+ became a service of Verizon Business.[265]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The real story of how the Internet became so vulnerable". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2015-05-30. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

Historians credit seminal insights to Welsh scientist Donald W. Davies and American engineer Paul Baran

- ^ a b c Pelkey, James L.; Russell, Andrew L.; Robbins, Loring G. (2022). Circuits, Packets, and Protocols: Entrepreneurs and Computer Communications, 1968-1988 (PDF). Morgan & Claypool. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4503-9729-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-04-23. Retrieved 2023-11-22.

Paul Baran, an engineer celebrated as the co-inventor (along with Donald Davies) of the packet switching technology that is the foundation of digital networks

- ^ a b "Inductee Details - Paul Baran". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved 6 September 2017; "Inductee Details - Donald Watts Davies". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Weik, Martin (6 December 2012). Fiber Optics Standard Dictionary. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1461560234.

- ^ National Telecommunication Information Administration (1 April 1997). Telecommunications: Glossary of Telecommunications Terms. Vol. 1037, Part 3 of Federal Standard. Government Institutes. ISBN 1461732328.

- ^ Forouzan, Behrouz A.; Fegan, Sophia Chung (2007). Data Communications and Networking. Huga Media. ISBN 978-0-07-296775-3.

- ^ a b Baran, Paul (1962). "RAND Paper P-2626".

- ^ a b Baran, Paul (January 1964). "On Distributed Communications".

- ^ a b Roberts, L. (1988), "The arpanet and computer networks", A history of personal workstations, New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 141–172, doi:10.1145/61975.66916, ISBN 978-0-201-11259-7, retrieved 2023-11-30

- ^ Edmondson-Yurkanan, Chris (2007). "SIGCOMM's archaeological journey into networking's past". Communications of the ACM. 50 (5): 63–68. doi:10.1145/1230819.1230840. ISSN 0001-0782.

The 1960 challenge was to build a network such that a significant subset of the network could survive a military attack. [Baran] told us he knew he could design a solution once he realized that, 'given redundant paths, the reliability of the net work could be greater than the reliability of the parts.' ... In his first draft dated Nov. 10, 1965, Davies forecast today's 'killer app' for his new communication service: 'The greatest traffic could only come if the public used this means for everyday purposes such as shopping... People sending enquiries and placing orders for goods of all kinds will make up a large section of the traffic... Business use of the telephone may be reduced by the growth of the kind of service we contemplate.'

- ^ a b Baran, Paul (2002). "The beginnings of packet switching: some underlying concepts" (PDF). IEEE Communications Magazine. 40 (7): 42–48. Bibcode:2002IComM..40g..42B. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2002.1018006. ISSN 0163-6804. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10.

Essentially all the work was defined by 1961, and fleshed out and put into formal written form in 1962. The idea of hot potato routing dates from late 1960.

- ^ Baran, Paul (May 27, 1960). "Reliable Digital Communications Using Unreliable Network Repeater Nodes" (PDF). The RAND Corporation: 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- ^ Stewart, Bill (2000-01-07). "Paul Baran Invents Packet Switching". Living Internet. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ "Paul Baran and the Origins of the Internet". RAND Corporation. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- ^ Pelkey, James L. "6.1 The Communications Subnet: BBN 1969". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications 1968–1988.

As Kahn recalls: ... Paul Baran's contributions ... I also think Paul was motivated almost entirely by voice considerations. If you look at what he wrote, he was talking about switches that were low-cost electronics. The idea of putting powerful computers in these locations hadn't quite occurred to him as being cost effective. So the idea of computer switches was missing. The whole notion of protocols didn't exist at that time. And the idea of computer-to-computer communications was really a secondary concern.

- ^ Waldrop, M. Mitchell (2018). The Dream Machine. Stripe Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-953953-36-0.

Baran had put more emphasis on digital voice communications than on computer communications.

- ^ Kleinrock, L. (1978). "Principles and lessons in packet communications". Proceedings of the IEEE. 66 (11): 1320–1329. doi:10.1109/PROC.1978.11143. ISSN 0018-9219.

Paul Baran ... focused on the routing procedures and on the survivability of distributed communication systems in a hostile environment, but did not concentrate on the need for resource sharing in its form as we now understand it; indeed, the concept of a software switch was not present in his work.

- ^ a b "Interview of Donald Davies" (PDF).

- ^ "Computer Pioneers - Christopher Strachey". history.computer.org. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ "Computer - Time-sharing, Minicomputers, Multitasking". Britannica. Retrieved 2023-07-23.

- ^ Corbató, F. J.; et al. (1963). The Compatible Time-Sharing System: A Programmer's Guide (PDF). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03008-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help). "the first paper on time-shared computers by C. Strachey at the June 1959 UNESCO Information Processing conference". - ^ Gillies & Cailliau 2000, p. 13

- ^ a b c d Roberts, Dr. Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Roberts, Dr. Lawrence G. (May 1995). "The ARPANET & Computer Networks". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- ^ Roberts, Gareth Ffowc (2022). For the Recorde: A History of Welsh Mathematical Greats. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78683-917-6.

Mathematicians had already developed methods of analysing traffic jams - 'queueing theory' ... - but it needed new a insight to solve the problem of how to avoid bottle-necks between computers.

- ^ Pelkey, James L. (May 27, 1988). "Interview of Donald Davies" (PDF).

- ^ a b Davies, D. W. (1966). "Proposal for a Digital Communication Network" (PDF).

all users of the network will provide themselves with some kind of error control ... Computer developments in the distant future might result in one type of network being able to carry speech and digital messages efficiently.

- ^ Scantlebury, R. A.; Bartlett, K. A. (April 1967), A Protocol for Use in the NPL Data Communications Network, Private papers

- ^ a b c Davies, Donald; Bartlett, Keith; Scantlebury, Roger; Wilkinson, Peter (October 1967). A Digital Communication Network for Computers Giving Rapid Response at remote Terminals (PDF). ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-10. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- ^ Yates, David M. (1997). Turing's Legacy: A History of Computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945-1995. National Museum of Science and Industry. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-901805-94-2.

- ^ Davies, D. W. (17 March 1986), Oral History 189: D. W. Davies interviewed by Martin Campbell-Kelly at the National Physical Laboratory, Charles Babbage Institute University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, archived from the original on 29 July 2014, retrieved 21 July 2014

- ^ "UK National Physical Laboratories, Donald Davies". LivingInternet. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ Hafner, Katie; Lyon, Matthew (1996). Where wizards stay up late: the origins of the Internet. Internet Archive. Simon & Schuster. pp. 76–78. ISBN 978-0-684-81201-4.

Roger Scantlebury ... from Donald Davies' team ... presented a detailed design study for a packet switched network. It was the first Roberts had heard of it. ... Roberts also learned from Scantlebury, for the first time, of the work that had been done by Paul Baran at RAND a few years earlier.

- ^ Moschovitis 1999, p. 58-9 More significantly, Roger Scantlebury ... presents the design for a packet-switched network. This is the first Roberts and Taylor have heard of packet switching, a concept that appears to be a promising receipe for transmitting data through the ARPAnet.

- ^ Hempstead, C.; Worthington, W., eds. (2005). Encyclopedia of 20th-Century Technology. Vol. 1, A–L. Routledge. p. 574. ISBN 9781135455514.

It was a seminal meeting as the NPL proposal illustrated how the communications for such a resource-sharing computer network could be realized.

- ^ "On packet switching". Net History. Retrieved 2024-01-08.

[Scantlebury said] We referenced Baran's paper in our 1967 Gatlinburg ACM paper. You will find it in the References. Therefore I am sure that we introduced Baran's work to Larry (and hence the BBN guys).

- ^ a b Naughton, John (2015). A Brief History of the Future: The origins of the Internet. Hachette. ISBN 978-1474602778.

they lacked one vital ingredient. Since none of them had heard of Paul Baran they had no serious idea of how to make the system work. And it took an English outfit to tell them. ... Larry Roberts paper was the first public presentation of the ARPANET concept as conceived with the aid of Wesley Clark ... Looking at it now, Roberts paper seems extraordinarily, well, vague.

- ^ Waldrop, M. Mitchell (2018). The Dream Machine. Stripe Press. pp. 285–6. ISBN 978-1-953953-36-0.

Scantlebury and his companions from the NPL group were happy to sit up with Roberts all that night, sharing technical details and arguing over the finer points.

- ^ a b c Abbate, Jane (2000). Inventing the Internet. MIT Press. pp. 37–8, 58–9. ISBN 978-0262261333.

The NPL group influenced a number of American computer scientists in favor of the new technique, and they adopted Davies's term "packet switching" to refer to this type of network. Roberts also adopted some specific aspects of the NPL design.

- ^ "Oral-History:Donald Davies & Derek Barber". Retrieved 13 April 2016.

the ARPA network is being implemented using existing telegraphic techniques simply because the type of network we describe does not exist. It appears that the ideas in the NPL paper at this moment are more advanced than any proposed in the USA

- ^ Barber, Derek (Spring 1993). "The Origins of Packet Switching". The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society (5). ISSN 0958-7403. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

Roger actually convinced Larry that what he was talking about was all wrong and that the way that NPL were proposing to do it was right. I've got some notes that say that first Larry was sceptical but several of the others there sided with Roger and eventually Larry was overwhelmed by the numbers.

- ^ Needham, Roger M. (2002-12-01). "Donald Watts Davies, C.B.E. 7 June 1924 – 28 May 2000". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 87–96. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0006. S2CID 72835589.

Larry Roberts presented a paper on early ideas for what was to become ARPAnet. This was based on a store-and-forward method for entire messages, but as a result of that meeting the NPL work helped to convince Roberts that packet switching was the way forward.

- ^ Rayner, David; Barber, Derek; Scantlebury, Roger; Wilkinson, Peter (2001). NPL, Packet Switching and the Internet. Symposium of the Institution of Analysts & Programmers 2001. Archived from the original on 2003-08-07. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

The system first went 'live' early in 1969

- ^ a b John S, Quarterman; Josiah C, Hoskins (1986). "Notable computer networks". Communications of the ACM. 29 (10): 932–971. doi:10.1145/6617.6618. S2CID 25341056.

The first packet-switching network was implemented at the National Physical Laboratories in the United Kingdom. It was quickly followed by the ARPANET in 1969.

- ^ a b c Haughney Dare-Bryan, Christine (June 22, 2023). Computer Freaks (Podcast). Chapter Two: In the Air. Inc. Magazine. 35:55 minutes in.

Leonard Kleinrock: Donald Davies ... did make a single node packet switch before ARPA did

- ^ a b c C. Hempstead; W. Worthington (2005). Encyclopedia of 20th-Century Technology. Routledge. pp. 573–5. ISBN 9781135455514.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin (1987). "Data Communications at the National Physical Laboratory (1965-1975)". Annals of the History of Computing. 9 (3/4): 221–247. doi:10.1109/MAHC.1987.10023. S2CID 8172150.

- ^ a b Needham, R. M. (2002). "Donald Watts Davies, C.B.E. 7 June 1924 – 28 May 2000". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 87–96. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0006. S2CID 72835589.

The 1967 Gatlinburg paper was influential on the development of ARPAnet, which might otherwise have been built with less extensible technology. ... Davies was invited to Japan to lecture on packet switching.

- ^ Clarke, Peter (1982). Packet and circuit-switched data networks (PDF) (PhD thesis). Department of Electrical Engineering, Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-08-03. Retrieved 2024-01-21. "As well as the packet switched network actually built at NPL for communication between their local computing facilities, some simulation experiments have been performed on larger networks. A summary of this work is reported in [69]. The work was carried out to investigate networks of a size capable of providing data communications facilities to most of the U.K. ... Experiments were then carried out using a method of flow control devised by Davies [70] called 'isarithmic' flow control. ... The simulation work carried out at NPL has, in many respects, been more realistic than most of the ARPA network theoretical studies."

- ^ Pelkey, James. "6.3 CYCLADES Network and Louis Pouzin 1971-1972". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications 1968-1988. Archived from the original on 2021-06-17. Retrieved 2020-02-03.

- ^ Campbell-Kelly, Martin (Autumn 2008). "Pioneer Profiles: Donald Davies". Computer Resurrection (44). ISSN 0958-7403.

- ^ Wilkinson, Peter (2001). NPL Development of Packet Switching. Symposium of the Institution of Analysts & Programmers 2001. Archived from the original on 2003-08-07. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

The feasibility studies continued with an attempt to apply queuing theory to study overall network performance. This proved to be intractable so we quickly turned to simulation.

- ^ a b Hafner, Katie (2018-12-30). "Lawrence Roberts, Who Helped Design Internet's Precursor, Dies at 81". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

He decided to use packet switching as the underlying technology of the Arpanet; it remains central to the function of the internet. And it was Dr. Roberts's decision to build a network that distributed control of the network across multiple computers. Distributed networking remains another foundation of today's internet.

- ^ Waldrop, M. Mitchell (2018). The Dream Machine. Stripe Press. pp. 285–6. ISBN 978-1-953953-36-0.

Oops. Roberts knew Baran slightly and had in fact had lunch with him during a visit to RAND the previous February. But he certainly didn't remember any discussion of networks. How could he have missed something like that?

- ^ O'Neill, Judy (5 March 1990). "An Interview with PAUL BARAN" (PDF). p. 37.

On Tuesday, 28 February 1967 I find a notation on my calendar for 12:00 noon Dr. L. Roberts.

- ^ Pelkey, James. "4.7 Planning the ARPANET: 1967-1968 in Chapter 4 - Networking: Vision and Packet Switching 1959 - 1968". The History of Computer Communications. Archived from the original on December 23, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ Press, Gil (January 2, 2015). "A Very Short History Of The Internet And The Web". Forbes. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved 2020-02-07.

Roberts' proposal that all host computers would connect to one another directly ... was not endorsed ... Wesley Clark ... suggested to Roberts that the network be managed by identical small computers, each attached to a host computer. Accepting the idea, Roberts named the small computers dedicated to network administration 'Interface Message Processors' (IMPs), which later evolved into today's routers.

- ^ SRI Project 5890-1; Networking (Reports on Meetings), Stanford University, 1967, archived from the original on February 2, 2020, retrieved 2020-02-15,

W. Clark's message switching proposal (appended to Taylor's letter of April 24, 1967 to Engelbart)were reviewed.

- ^ a b Roberts, Lawrence (1967). "Multiple computer networks and intercomputer communication" (PDF). Multiple Computer Networks and Intercomputer Communications. pp. 3.1 – 3.6. doi:10.1145/800001.811680. S2CID 17409102.

Thus the set of IMP's, plus the telephone lines and data sets would constitute a message switching network

- ^ a b c Tanenbaum, Andrew S.; Wetherall, David (2011). Computer networks (PDF) (5th ed.). Boston Amsterdam: Prentice Hall. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-13-212695-3.

Roberts bought the idea and presented a some what vague paper about it at the ACM SIGOPS Symposium on Operating System Principles held in Gatlinburg, Tennessee in late 1967

- ^ Waldrop, M. Mitchell (2018). The Dream Machine. Stripe Press. pp. 279, 284–5. ISBN 978-1-953953-36-0.

Roberts was already becoming known as the fastest man in the Pentagon. ... And not for nothing was Larry Roberts known as the fastest man in the Pentagon. By the time they got to the airport, the decision had been made .... Once again, the fastest man in the Pentagon made his decision without hesitation

- ^ a b "Shapiro: Computer Network Meeting of October 9–10, 1967". stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Computer Pioneers - Donald W. Davies". IEEE Computer Society. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

In 1965, Davies pioneered new concepts for computer communications in a form to which he gave the name "packet switching." ... The design of the ARPA network (ArpaNet) was entirely changed to adopt this technique.

- ^ "Pioneer: Donald Davies", Internet Hall of Fame "America’s Advanced Research Project Agency (ARPA), and the ARPANET received his network design enthusiastically and the NPL local network became the first two computer networks in the world using the technique."

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2014). The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon and Schuster. p. 246. ISBN 9781476708690.

- ^ Davies, D. W. (1966). "Proposal for a Digital Communication Network" (PDF). p. 10, 16.

- ^ Heart, F.; McKenzie, A.; McQuillian, J.; Walden, D. (January 4, 1978). Arpanet Completion Report (PDF) (Technical report). Burlington, MA: Bolt, Beranek and Newman. pp. III-40-1

- ^ "SRI Project 5890-1; Networking (Reports on Meetings). [1967]". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- ^ Hafner & Lyon 1996

- ^ a b Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 39, 57–58. ISBN 978-0-2625-1115-5.

Baran proposed a "distributed adaptive message-block network" [in the early 1960s] ... Roberts recruited Baran to advise the ARPANET planning group on distributed communications and packet switching. ... Roberts awarded a contract to Leonard Kleinrock of UCLA to create theoretical models of the network and to analyze its actual performance.

- ^ Summary of ARPA ad hoc meeting, November 3, 1967,

We propose that a working group of approximately four people devote some concentrated effort in the near future in defining the IMP precisely. This group would interact with the larger group from the earlier meetings from time to time. Tentatively we think that the core of this investigatory group would be Bhushan (MIT), Kleinrock (UCLA), Shapiro (SRI) and Westervelt (University of Michigan), along with a kibitzer's group, consisting of such people as Baran (Rand), Boehm (Rand), Culler (UCSB) and Roberts (ARPA).

- ^ Judy O'Neill (1990), Oral history interview with Paul Baran, Charles Babbage Institute, hdl:11299/107101,

BARAN: On Tuesday, 31 October 1967 I see a notation 9:30 AM to 2:00 PM for ARPA's (Elmer) Shapiro, (Barry) Boehm, (Len) Kleinrock, ARPA Network. On Monday, 13 November 1967 I see the following: Larry Roberts to abt (about?) lunch (time?). Art Bushkin = 1:00 PM. Here. Larry Roberts IMP Committee. On Thursday, 16 November 1967 I see 7 PM Kleinrock, UCLA - IMP Meeting.

- ^ Meeting of the ARPA Computer Network Working Group at UCLA, November 16, 1967

- ^ a b Hafner & Lyon 1996, pp. 116, 149

- ^ Pelkey, James L. "6.1 The Communications Subnet: BBN 1969". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications 1968–1988.

Kahn, the principal architect

- ^ a b Roberts, Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching" (PDF). IEEE Invited Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

Significant aspects of the network's internal operation, such as routing, flow control, software design, and network control were developed by a BBN team consisting of Frank Heart, Robert Kahn, Severo Omstein, William Crowther, and David Walden

- ^ a b F.E. Froehlich, A. Kent (1990). The Froehlich/Kent Encyclopedia of Telecommunications: Volume 1 - Access Charges in the U.S.A. to Basics of Digital Communications. CRC Press. p. 344. ISBN 0824729005.

Although there was considerable technical interchange between the NPL group and those who designed and implemented the ARPANET, the NPL Data Network effort appears to have had little fundamental impact on the design of ARPANET. Such major aspects of the NPL Data Network design as the standard network interface, the routing algorithm, and the software structure of the switching node were largely ignored by the ARPANET designers. There is no doubt, however, that in many less fundamental ways the NPL Data Network had and effect on the design and evolution of the ARPANET.

- ^ RFC 334

- ^ RFC 53

- ^ Heart, F.; McKenzie, A.; McQuillian, J.; Walden, D. (January 4, 1978). Arpanet Completion Report (PDF) (Technical report). Burlington, MA: Bolt, Beranek and Newman. p. III-63.

- ^ a b c Clarke, Peter (1982). Packet and circuit-switched data networks (PDF) (PhD thesis). Department of Electrical Engineering, Imperial College of Science and Technology, University of London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-08-03. Retrieved 2024-01-21. "Many of the theoretical studies of the performance and design of the ARPA Network were developments of earlier work by Kleinrock ... Although these works concerned message switching networks, they were the basis for a lot of the ARPA network investigations ... The intention of the work of Kleinrock [in 1961] was to analyse the performance of store and forward networks ... Kleinrock [in 1970] extended the theoretical approaches of [his 1961 work] to the early ARPA network."

- ^ Abbate, Janet (1999). Inventing the Internet. Internet Archive. MIT Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-262-01172-3.

On Kleinrock's influence, see Frank, Kahn, and Kleinrock 1972, p. 265; Tanenbaum 1989, p. 631.

- ^ Davies, Donald Watts (1979). Computer networks and their protocols. Internet Archive. Wiley. pp. See page refs highlighted at url. ISBN 978-0-471-99750-4.

- ^ Kleinrock, L. (1978). "Principles and lessons in packet communications". Proceedings of the IEEE. 66 (11): 1320–1329. doi:10.1109/PROC.1978.11143. ISSN 0018-9219.

- ^ Pelkey, James. "8.3 CYCLADES Network and Louis Pouzin 1971–1972". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications 1968–1988.

- ^ Hafner & Lyon 1996, p. 222

- ^ Pelkey, James. "8.4 Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) 1973-1976". Entrepreneurial Capitalism and Innovation: A History of Computer Communications 1968–1988.

Arpanet had its deficiencies, however, for it was neither a true datagram network nor did it provide end-to-end error correction.

- ^ Pouzin, Louis (May 1975). "An integrated approach to network protocols". Proceedings of the May 19-22, 1975, national computer conference and exposition on - AFIPS '75. Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 701–707. doi:10.1145/1499949.1500100. ISBN 978-1-4503-7919-9. S2CID 1689917.

- ^ a b Roberts, Dr. Lawrence G. (November 1978). "The Evolution of Packet Switching" (PDF). IEEE Invited Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 31, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ a b Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. MIT Press. pp. 124–127. ISBN 978-0-262-51115-5.

In fact, CYCLADES, unlike ARPANET, had been explicitly designed to facilitate internetworking; it could, for instance, handle varying formats and varying levels of service

- ^ Kim, Byung-Keun (2005). Internationalising the Internet the Co-evolution of Influence and Technology. Edward Elgar. pp. 51–55. ISBN 1845426754.

In addition to the NPL Network and the ARPANET, CYCLADES, an academic and research experimental network, also played an important role in the development of computer networking technologies

- ^ "The internet's fifth man". The Economist. 2013-11-30. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

In the early 1970s Mr Pouzin created an innovative data network that linked locations in France, Italy and Britain. Its simplicity and efficiency pointed the way to a network that could connect not just dozens of machines, but millions of them. It captured the imagination of Dr Cerf and Dr Kahn, who included aspects of its design in the protocols that now power the internet.

- ^ a b Bennett, Richard (September 2009). "Designed for Change: End-to-End Arguments, Internet Innovation, and the Net Neutrality Debate" (PDF). Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. pp. 7, 9, 11. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

Two significant packet networks preceded the TCP/IP Internet: ARPANET and CYCLADES. The designers of the Internet borrowed heavily from these systems, especially CYCLADES ... The first end-to-end research network was CYCLADES, designed by Louis Pouzin at IRIA in France with the support of BBN's Dave Walden and Alex McKenzie and deployed beginning in 1972.