Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Red-figure pottery

View on Wikipedia

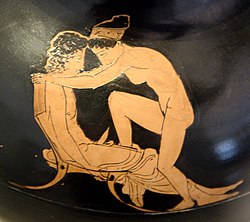

Red-figure pottery (Ancient Greek: ἐρυθρόμορφα, romanized: erythrómorpha) is a style of ancient Greek pottery in which the background of the pottery is painted black while the figures and details are left in the natural red or orange color of the clay.

It developed in Athens around 520 BC and remained in use until the late 3rd century AD. It replaced the previously dominant style of black-figure pottery within a few decades. Its modern name is based on the figural depictions in red color on a black background, in contrast to the preceding black-figure style with black figures on a red background. The most important areas of production, apart from Attica, were in Southern Italy. The style was also adopted in other parts of Greece. Etruria became an important center of production outside the Greek World.

Attic red-figure vases were exported throughout Greece and beyond. For a long time, they dominated the market for fine ceramics. Few centers of pottery production could compete with Athens in terms of innovation, quality and production capacity. Of the red-figure vases produced in Athens alone, more than 40,000 specimens and fragments survive today. From the second-most important production center, Southern Italy, more than 20,000 vases and fragments are preserved. Starting with the studies by John D. Beazley and Arthur Dale Trendall, the study of this style of art has made enormous progress. Some vases can be ascribed to individual artists or schools. The images provide evidence for the exploration of Greek cultural history, everyday life, iconography, and mythology.

Technique

[edit]

Red figure is, put simply, the reverse of the black figure technique. Both were achieved by using the three-phase firing technique. The paintings were applied to the shaped but unfired vessels after they had dried to a leathery, near-brittle texture. In Attica, the normal unfired clay was an orange color at this stage. The outlines of the intended figures were drawn either with a blunt scraper, leaving a slight groove, or with charcoal, which would disappear entirely during firing. Then the contours were redrawn with a brush, using a glossy clay slip. Occasionally, the painter decided to somewhat change the figurative scene. In such cases the grooves from the original sketch sometimes remain visible. Important contours were often drawn with a thicker slip, leading to a slightly protruding outline (relief line); less important lines and internal details were drawn with diluted glossy clay.

Detail in other colors, Including white or red, were applied at this point. The relief line was probably drawn with a bristle brush or a hair, dipped in thick paint. (The suggestion that a hollow needle could account for such features seems somewhat unlikely.)[a] The application of relief outlines was necessary, as the rather liquid glossy clay would otherwise have turned out too dull. After the technique's initial phase of development, both alternatives were used, to differentiate gradations and details more clearly. The space between figures was filled with a glossy grey clay slip. Then, the vases underwent triple-phase firing, during which the glossy clay reached its characteristic black or black-brown color through reduction, the reddish color by a final re-oxidation.[b] Since this final oxidizing phase was fired using lower temperatures, the glazed parts of the vase did not re-oxidize from black to red: their finer surface was melted (sintered) in the reducing phase, and now protected from oxygen.

The new technique had the primary advantage of permitting a far better execution of internal detail. In black-figure vase painting such details had to be scratched into the painted surfaces, which was always less accurate than the direct application of detail with a brush. Red-figure depictions were generally more lively and realistic than the black-figure silhouettes. They were also more clearly contrasted against the black backgrounds. It was now possible to depict humans not only in profile, but also in frontal, rear, or three-quarter perspectives. The red-figure technique also permitted the indication of a third dimension on the figures. However, it also had disadvantages. For example, the distinction of sex by using black slip for male skin and white paint for female skin was now impossible. The ongoing trend to depict heroes and deities naked and of youthful age also made it harder to distinguish the sexes through garments or hairstyles. In the initial phases, there were also miscalculations regarding the thickness of human figures.

In black-figure vase painting, the pre-drawn outlines were a part of the figure. In red-figure vases, the outline would, after firing, form part of the black background. This led to vases with very thin figures early on. A further problem was that the black background did not permit the depiction of space in any depth, so that spatial perspective was almost never attempted. Nonetheless, the advantages outnumbered the disadvantages. The depiction of muscles and other anatomical details clearly illustrates the development of the style.[1]

Attica

[edit]

Black-figure vase painting had been developed in Corinth in the 7th century BC and quickly became the dominant style of pottery decoration throughout the Greek world and beyond. Although Corinth dominated the overall market, regional markets and centers of production did develop. Initially, Athens copied the Corinthian style, but it gradually came to rival and overcome the dominance of Corinth. Attic artists developed the style to an unprecedented quality, reaching the apex of their creative possibilities in the second third of the 6th century BC. Exekias, active around 530 BC, can be seen as the most important representative of the black-figure style.

In the 5th century BC Attic fine pottery, now predominantly red-figure, maintained its dominance in the markets. Attic pottery was exported to Magna Graecia and even Etruria. The preference for Attic vases led to the development of local South Italian and Etruscan workshops or "schools", strongly influenced by Attic style, but producing exclusively for local markets.

Beginnings

[edit]The first red-figure vases were produced around 530 BC. The invention of the technique normally is accredited to the Andokides Painter. He, and other early representatives of the style, e.g. Psiax, initially painted vases in both styles, with black-figure scenes on one side, and red-figure on the other. Such vases, e.g. the Belly Amphora by the Andokides Painter (Munich 2301), are called bilingual vases. Although they display major advances against the black-figure style, the figures still appear somewhat stilted and seldom overlap. Compositions and techniques of the older style remained in use. Thus incised lines are quite common, as is the additional application of red paint ("added red") to cover large areas.[2]

Pioneering phase

[edit]

The artists of the so-called "Pioneer Group" made the step towards a full exploitation of the possibilities of the red-figure technique. They were active between circa 520 and 500 BC. Important representatives include Euphronios, Euthymides and Phintias. This group, recognised and defined by twentieth-century scholarship, experimented with the different possibilities offered by the new style. Thus figures appeared in new perspectives, such as frontal or rear views, and there were experiments with perspective foreshortening and more dynamic compositions. As a technical innovation Euphronios introduced the "relief line". At the same time new vase shapes were invented, a development favored by the fact that many of the pioneer group painters were also active as potters.

New shapes include the psykter and the pelike. Large krater and amphorae became popular at this time. Although there is no indication that the painters understood themselves as a group in the way that modern scholarship does, there were some connections and mutual influences, perhaps in an atmosphere of friendly competition and encouragement. Thus a vase by Euthymides is inscribed "as Euphronios never [would have been able]". More generally, the pioneer group tended to use inscriptions. The labelling of mythological figures or the addition of Kalos inscriptions are the rule rather than the exception.[2]

Apart from the vase painters, some bowl painters also used the new style. These include Oltos and Epiktetos. Many of their works were bilingual, often using red-figure only on the interior of the bowl.

Late Archaic

[edit]

The generation of artists after the pioneers, active during the Late Archaic period (circa 500 to 470 BC) brought the style to a new flourish. During this time, black-figure vases failed to reach the same quality and were pushed out of the market eventually. Some of the most famous Attic vase painters belong to this generation. They include the Berlin Painter, the Kleophrades Painter, and among the bowl painters Onesimos, Douris, Makron and the Brygos Painter. The improvement of quality went along with a doubling of output during this period. Athens became the dominant producer of fine pottery in the Mediterranean world, overshadowing nearly all other production centers.[3]

One of the key features of this most successful Attic vase painting style is the mastery of perspective foreshortening, allowing a much more naturalistic depiction of figures and actions. Another characteristic is the drastic reduction of figures per vessel, of anatomic details, and of ornamental decorations. In contrast, the repertoire of depicted scenes was increased. For example, the myths surrounding Theseus became very popular at this time. New or modified vase shapes were frequently employed, including the Nolan amphora (see Typology of Greek Vase Shapes), lekythoi, as well as bowls of the askos and dinos types. The specialisation into separate vase and bowl painters increased.[3]

Early and High Classical

[edit]

The key characteristic of Early Classical figures is that they are often stockier and less dynamic than their predecessors. As a result, the depictions gained seriousness, even pathos. The folds of garments were depicted less linearly, appearing more plastic. The manner of presenting scenes also changed substantially. Firstly, the paintings ceased to focus on the moment of a particular event, but rather, with dramatic tension, showed the situation immediately before the action, implying and contextualising the event proper. Also, some of the other new achievements of Athenian democracy began to show an influence on vase painting. Thus influences of tragedy and of wall painting can be detected. Since Greek wall painting is almost entirely lost today, its reflection on vases constitutes one of the few, albeit modest, sources of information on that genre of art.

Other influences on High Classical vase painting include the newly erected Parthenon and its sculptural decoration. This is especially visible in the depiction of garments; the material now falls more naturally, and more folds are depicted, leading to an increased "depth" of the depiction. The overall compositions were simplified even more. Artists placed special emphasis on symmetry, harmony, and balance. The human figures had returned to their earlier slenderness; they often radiate a self-absorbed, divine serenity.[3]

Important painters of this period, roughly 480 to 425 BC, include the Providence Painter, Hermonax, and the Achilles Painter, all following the tradition of the Berlin Painter. The Phiale Painter, probably a pupil of the Achilles Painter, is also important. New workshop traditions also developed. Notable examples include the so-called "mannerists", most famously among them the Pan Painter. Another tradition was begun by the Niobid Painter and continued by Polygnotos, the Kleophon Painter, and the Dinos Painter. The role of bowls decreased, although they were still produced in large numbers, e.g. by the workshop of the Penthesilea Painter.[3]

Late Classical

[edit]

During the Late Classical period, in the final quarter of the 5th century BC, two opposed trends were created. On the one hand, a style of vase painting strongly influenced by the "Rich Style" of sculpture developed, on the other, some workshops continued the developments of the High Classical period, with an increased emphasis on the depiction of emotion, and a range of erotic scenes. The most important representative of the Rich Style is the Meidias Painter. Characteristic features include transparent garments and multiple folds of cloth. There is also an increase in the depiction of jewelry and other objects. The use of additional colors, mostly white and gold, depicting accessories in a low relief, is very striking. Over time, there is a marked "softening": The male body, heretofore defined by the depiction of muscles, gradually lost that key feature.[3]

The paintings depicted mythological scenes less frequently than before. Images of the private and domestic world became more and more important. Scenes from the life of women are especially frequent. Mythological scenes are dominated by images of Dionysos and Aphrodite. It is not clear what caused this change of topic among some of the artists. Suggestions include a context with the horrors of the Peloponnesian War, but also the loss of Athens' dominant role in the Mediterranean pottery trade (itself partially a result of the war). The increasing role of new markets, e.g. Iberia, implied new needs and wishes on part of the customers. These theories are contradicted by the fact that some artists maintained the earlier style. Some, e.g. the Eretria Painter, attempted to combine both traditions. The best works of the Late Classical period are often found on smaller vessels, such as belly lekythoi, pyxides and oinochai. Lekanis, Bell krater(see Typology of Greek Vase Shapes) and hydria were also popular.[4]

The production of mainstream red-figure pottery ceased around 360 BC. The Rich and Simple styles both existed until that time. Late representatives include the Meleager Painter (Rich Style) and the Jena Painter (Simple Style).

Kerch Style

[edit]The final decades of Attic red—figure vase painting are dominated by the Kerch Style. This style, current between 370 and 330 BC, combined the preceding Rich and Modest Styles, with a preponderance of the Rich. Crowded compositions with large statuesque figures are typical. The added colors now include blue, green and others. Volume and shading are indicated by the use of diluted runny glossy clay. Occasionally, whole figures are added as appliques, i.e. as thin figural reliefs attached to the body of the vase. The variety of vessel shapes in use was reduced sharply. Common painted shapes include pelike, chalice krater, belly lekythos, skyphos, hydria and oinochoe. Scenes from female life are very common. Mythological themes are still dominated by Dionysos; Ariadne and Heracles are the most commonly depicted heroes. The best-known painter of this style is the Marsyas Painter.[4]

The last Athenian vases with figural depictions were created around 320 BC at the latest. The style continued somewhat longer, but with non-figural decorations. The last recognised examples are by painters known as the YZ Group.

Artists and works

[edit]

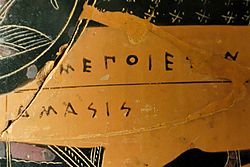

The Kerameikos was the potters' quarter of Athens. It contained a variety of small workshops, and probably a few larger ones. In 1852 AD, during building activity in Ermou Street, the workshop of the Jena Painter was discovered. The artefacts from it are now on display in the University collection of the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena.[5] According to modern research, the workshops were owned by the potters. The names of about 40 Attic vase painters are known, from vase inscriptions, usually accompanied by the words ἐγραψεν (égrapsen, has painted). In contrast, the signature of the potter, ἐποίησεν (epoíesen, has made) has survived on more than twice as many, namely about 100, pots (both numbers refer to the totality of Attic figural vase painting). Although signatures had been known since c. 580 BC (first known signature by the potter Sophilos), their use increased to an apex around the Pioneering Phase. A changing, apparently increasingly negative, attitude to artisans led to a reduction of signatures, starting during the Classical period at the latest.[6] Overall, signatures are quite rare. The fact that they are mostly found on especially good pieces indicates that they expressed the pride of potter and/or painter.[7]

The status of painters in relation to that of potters remains somewhat unclear. The fact that, e.g., Euphronius was able to work as both painter and potter suggests that at least some of the painters were not slaves. On the other hand, some of the known names indicate that there were at least some former slaves and some perioikoi among the painters. Additionally, some of the names are not unique: for example, several painters signed as Polygnotos. This may represent attempts to profit from the name of that great painter. The same may be the case where painters bear otherwise famous names, like Aristophanes (vase painter). The careers of some vase painters are quite well known. Apart from painters with relatively short periods of activity (one or two decades), some can be traced for much longer. Examples include Douris, Makron, Hermonax and the Achilles Painter. The fact that several painters later became potters, and the relatively frequent cases where it is unclear whether some potters were also painters or vice versa, suggest a career structure, perhaps starting with an apprenticeship involving mainly painting, and leading up to being a potter.

This division of labor appears to have developed along with the introduction of red-figure painting, since many potter-painters are known from the black-figure period (including Exekias, Nearchos and perhaps the Amasis Painter). The increased demand for exports would have led to new structures of production, encouraging specialisation and division of labor, leading to a sometimes ambiguous distinction between painter and potter. As mentioned above, the painting of vessels was probably mainly the responsibility of younger assistants or apprentices. Some further conclusions regarding the organisational aspects of pottery production can be suggested. It appears that generally, several painters worked for one pottery workshop, as indicated by the fact that frequently, several roughly contemporary pots by the same potter are painted by various painters. For examples, pots made by Euphronios have been found to be painted by Onesimos, Douris, the Antiphon Painter, the Triptolemos Painter and the Pistoxenos Painter. Conversely, an individual painter could also change from one workshop to another. For example, the bowl painter Oltos worked for at least six different potters.[7]

Although from a modern perspective the vase painters are often considered artists, and their vases thus as works of art, this view is not consistent with that held in antiquity. Vase painters, like potters, were considered craftsmen, their produce considered trade goods.[8] The craftsmen must have had a reasonably high level of education, as a variety of inscriptions occur. On the one hand, the aforementioned Kalos inscriptions are common; on the other hand, inscriptions often label the depicted figures. That not every vase painter could write is shown by some examples of meaningless rows of random letters. The vases indicate a steady improvement of literacy from the 6th century BC onwards.[9] Whether potters, and perhaps vase painters, belonged to the Attic elite has not been satisfactorily clarified so far. Do the frequent depictions of the symposium, a definite upper-class activity, reflect the painters' personal experience, their aspirations to attend such events, or simply the demands of the market?[10] A large proportion of the painted vases produced, such as psykter, krater, kalpis, stamnos, as well as kylikes and kantharoi, were made and bought to be used at symposia.[11]

Elaborately painted vases were good, but not the best, table wares available to a Greek. Metal vessels, especially from precious metals, were held in higher regard. Nonetheless, painted vases were not cheap products; the larger specimens, especially, were expensive. Around 500 BC, a large painted vase cost about one drachma, equivalent to the daily wage of a stonemason. It has been suggested that the painted vases represent an attempt to imitate metal vessels. It is normally assumed that the lower social classes tended to use simple undecorated coarse wares, massive quantities of which are found in excavations. Tablewares made of perishable materials, like wood, may have been even more widespread.[12] Nonetheless, multiple finds of red-figure vases, usually not of the highest quality, found in settlements, prove that such vessels were used in daily life. A large proportion of production was taken up by cult and grave vessels. In any case, it can be assumed that the production of high-quality pottery was a profitable business. For example, an expensive votive gift by the painter Euphronios was found on the Athenian Acropolis.[13] There can be little doubt that the export of such pottery made an important contribution to the affluence of Athens. It is hardly surprising that many workshops appear to have aimed their production at export markets, for example by producing vessel shapes that were more popular in the target region than in Athens. The 4th century BC demise of Attic vase painting tellingly coincides with the very period when the Etruscans, probably the main western export market, came under increasing pressure from South Italian Greeks and the Romans. A further reason for the end of the production of figurally decorated vases is a change in tastes at the start of the Hellenistic period. The main reason, however, should be seen in the increasingly unsuccessful progress of the Peloponnesian War, culminating in the devastating defeat of Athens in 404 BC. After this, Sparta controlled the western trade, albeit without having the economic strength to fully exploit it. The Attic potters had to find new markets; they did so in the Black Sea area. But Athens and its industries never fully recovered from the defeat. Some potters and painters had already relocated to Italy during the war, seeking better economic conditions. A key indicator for the export-oriented nature of Attic vase production is the nearly total absence of theatre scenes. Buyers from other cultural backgrounds, such as Etruscans or later customers in the Iberian Peninsula, would have found such depiction incomprehensible or uninteresting. In Southern Italian vase painting, which was mostly not aimed at export, such scenes are quite common.[14]

Southern Italy

[edit]At least from a modern point of view, the Southern Italian red-figure vase paintings represent the only region of production that reaches Attic standards of artistic quality. After the Attic vases, the South Italian ones (including those from Sicily), are the most thoroughly researched. In contrastic to their Attic counterparts, they were mostly produced for local markets. Only few pieces have been found outside Southern Italy and Sicily. The first workshops were founded in the mid-5th century BC by Attic potters. Soon, local craftsmen were trained and the thematic and formal dependence on Attic vases overcome. Towards the end of the century, the distinctive "ornate style" and "plain style" developed in Apulia. Especially the ornate style was adopted by other mainland schools, but without reaching the same quality.[15]

By now, 21,000 South Italian vases and fragments are known. Of those, 11,000 are ascribed to Apulian workshops, 4,000 to Campanian, 2,000 to Paestan, 1,500 to Lucanian and 1,000 to Sicilian ones.[16]

Apulia

[edit]

The Apulian vase painting tradition is considered as the leading South Italian style. The main centre of production was at Taras. Apulian red-figure vases were produced from circa 430 to 300 BC. The plain and ornate styles are distinguished. The main difference between them is that the plain style favoured bell craters, column kraters and smaller vessels, and that a single "plain" vessel rarely depicted more than four figures. The main subjects were mythological scenes, female heads, warriors in scenes of combat of farewell, and dionysiac thiasos imagery. The reverse often showed youths wearing cloaks. The key feature of these simply decorated wares is the general absence of additional colours. Important plain style representatives are the Sisyphus Painter and the Tarporley Painter. After the mid-4th century BC, the style grows more and more similar to the ornate style. An important artist of that period is the Varrese Painter.[17]

The artists using the ornate style tended to favour large vessels, like volute kraters, amphorae, loutrophoroi and hydriai. The larger surface area was used to depict up to 20 figures, often in several registers on the body of the vase. Additional colours, especially shades of red, yellow-gold and white are used copiously. Since the 2nd half of the 4th century, the necks and sides of the vases are decorated with rich vegetal or ornamental decorations. At the same time, perspective views, especially of buildings such as "Palace of Hades" (naiskoi), develop. Since 360 BC, such structures are often depicted in scenes connected with burial rites (naiskos vases). Important representatives of this style are the Ilioupersis Painter, the Darius Painter and the Baltimore Painter. Mythological scenes were especially popular: The assembly of the Gods, the amazonomachy, the Trojan War, Heracles and Bellerophon. Additionally, such vases frequently depict scenes from myths that are only rarely illustrated on vases. Some specimens represent the single source for the iconography of a particular myth. Another subject that is unknown from Attic vase painting are the theatre scenes. Especially farce scenes, e.g. from the so-called phlyax vases are quite common. Scenes of athletic activity or everyday life only occur in the early phase, they disappear entirely after 370 BC.[18]

Apulian vase painting had a formative influence on the traditions of the other South Italian production centres. It is assumed that individual Apulian artists settled in other Italian cities and contributed their skills there. Apart from red-figure, Apulia also produced black-varnished vases with painted decor (Gnathia vases) and polychrome vases (Canosa vases).[19]

Campania

[edit]

Campania also produced red-figure vases in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. The light brown clay of Campania was covered with a slip that developed a pink or red tint after firing. The Campanian painters preferred smaller vessel types, but also hydriai and bell kraters. The most popular shape is the bow-handled amphora. Many typical Apulian vessel shapes, like volute kraters, column kraters, loutrophoroi, rhyta and nestoris amphorae are absent, pelikes are rare. The repertoire of motifs is limited. Subjects include youths, women, thiasos scenes, birds and animals, and often native warriors. The backs often show cloaked youths. Mythological scenes and depictions related to burial rites play a subsidiary role. Naiskos scenes, ornamental elements and polychromy are adopted after 340 BC under Lucanian influence.[20]

Before the immigration of Sicilian potters in the second quarter of the 4th century BC, when several workshops were established in Campania, only the Owl-Pillar Workshop of the second half of the 5th century is known. Campanian vase painting is subdivided in three main groups:

The first group is represented by the Kassandra Painter from Capua, still under Sicilian influence. He was followed by the workshop of the Parrish Painter and that of the Laghetto Painter and the Caivano Painter. Their work is characterised by a preference for satyr figures with thyrsos, depictions of heads (normally below the handles of hydriai), decorative borders of garments, and the frequent use of additional white, red and yellow. The Laghetto and Caivano Painters appear to have moved to Paestum later.[21]

The AV Group also had its workshop in Capua. Of particular importance is the Whiteface-Frignano Painter, one of the first in this group. His typical characteristic is the use of additional white paint to depict the faces of women. This group favoured domestic scenes, women and warriors. Multiple figures are rare, usually there is only one figure each on the front and back of the vase, sometimes only the head. Garments are usually drawn casually.[22]

After 350 BC, the CA Painter and his successors worked in Cumae. The CA painter is considered as the outstanding artist of his group, or even of Campanian vase painting as a whole. From 330 onwards, a strong Apulian influence is visible. The most common motifs are naiskos and grave scenes, dionysiac scenes and symposia. Depictions of bejewelled female heads are also common. The CA painter was polychrome but tended to use much white for architecture and female figures. His successors were not fully able to maintain his quality, leading to a rapid demise, terminating with the end of Campanian vase painting around 300 BC.[22]

Lucania

[edit]The Lucanian vase painting tradition began around 430 BC, with the works of the Pisticci Painter. He was probably active in Pisticci, where some of his works were discovered. He was strongly influenced by Attic tradition. His successors, the Amycus Painter and the Cyclops Painter had a workshop in Metapontum. They were the first to paint the new nestoris (see Typology of Greek Vase Shapes) vase type. Mythical or theatrical scenes are common. For example, the Cheophoroi painter, named after the Cheophoroi by Aeschylos showed scenes from the tragedy in question on several of his vases. The influence of Apulian vase painting becomes tangible roughly at the same time. Especially polychromy and vegetal decor became standard. Important representatives of this style include the Dolon Painter and the Brooklyn-Budapest Painter. Towards the mid-4th century BC, a massive drop in quality and thematic variety becomes notable. The last notable Lucanian vase painter was the Primato Painter, strongly influenced by the Apulian Lycourgos Painter. After him, a short rapid demise is followed by the cessation of Lucanian vase painting at the start of the last quarter of the 4th century BC.[23]

Paestum

[edit]

The Paestan vase painting style developed as the last of the South Italian styles. It was founded by Sicilian immigrants around 360 BC. the first workshop was controlled by Asteas and Python. They are the only South Italian vase painters known from inscriptions. They mainly painted bell kraters, neck amphorae, hydriai, lebes gamikos, lekanes, lekythoi and jugs, more rarely pelikes, chalice kraters and volute kraters. Characteristics include decorations such as lateral palmettes, a pattern of tendrils with calyx and umbel known as "asteas flower", crenelation-like patterns on garments and curly hair hanging over the back of figures. Figures that bend forwards, resting on plants or rocks, are equally common. Special colours are used often, especially white, gold, black, purple and shades of red.[24]

The themes depicted often belong to the Dionysiac cycle: thiasos and symposium scenes, satyrs, maenads, Silenos, Orestes, Electra, the gods Aphrodite and Eros, Apollo, Athena and Hermes. Paestan painting rarely depicts domestic scenes, but favours animals. Asteas and Python had a major influence on the vase painting of Paestum. This is clearly visible in the work of the Aphrodite Painter, who probably immigrated from Apulia. Around 330 BC, a second workshop developed, originally following the work of the first. The quality of its painting and variety of its motifs deteriorated quickly. At the same time, an influence by the Campanian Caivano Painter becomes notable, garments falling in a linear fashion and contourless female figures followed. Around 300 BC, Paestan vase painting came to a halt.[25]

Sicily

[edit]

The production of Sicilian vase painting began before the end of the 5th century BC, in the poleis of Himera and Syracusae. In terms of style, themes, ornamentation and vase shapes, the workshops were strongly influenced by the Attic tradition, especially by the Late Classical Meidias Painter. In the second quarter of the 4th century, Sicilian vase painters emigrated to Campania and Paestum, where they introduced red-figure vase painting. Only Syracusae retained a limited production.[26]

The typical Sicilian style only developed around 340 BC. Three groups of workshops can be distinguished. The first, known as the Lentini-Manfria Group, was active in Syracusae and Gela, a second, making Centuripe Ware around Mt. Aetna, and a third on Lipari. The most typical feature of Sicilian vase painting is the use of additional colours, especially white. In the early phase, large vessels like chalice kraters and hydriai were painted, but smaller vessels like flasks, lekanes, lekythoi and skyphoid pyxides are more typical. The most common motifs are scenes from female life, erotes, female heads and phlyax scenes. Mythological scenes are rare. Like in all other areas, vase painting disappears from Sicily around 300 BC.[26]

Etruria and other regions

[edit]

In contrast to black-figure vase painting, red-figure vase painting developed few regional traditions, workshops or "schools" outside Attica and Southern Italy. The few exceptions include some workshops in Boeotia (Painter of the Great Athens Kantharos), Chalkidike, Elis, Eretria, Corinth and Laconia.

Only Etruria, one of the main export markets for Attic vases, developed its own schools and workshops, eventually exporting its own products. The adoption of red-figure painting, imitating Athenian vases, occurred only after 490 BC, half a century after the style had been developed. Because of the technique used, the earliest examples are known as pseudo-red-figure vase paintings. The true red-figure technique was introduced much later, near the end of the 5th century BC. Several painters, workshops and production centres are known for both styles. Their products were not only used locally, but also exported to Malta, Carthage, Rome and Liguria.

Pseudo-red-figure vase painting

[edit]The early Etruscan examples merely imitated the red-figure technique. Similar to a rare and early Attic technique (see Six's technique), the whole vessel was covered with black glossy clay and figures were applied afterwards using mineral colours that would oxidise red or white. Thus, in contrast to contemporary Attic vase painting, the red colour was not achieved by leaving areas unpainted but by adding paint to the black prime layer. Like in black-figure vases, internal detail was not painted on, but incised into the figures. Important representatives of this style include the Praxias Painter and other masters from his workshop in Vulci. In spite of their evident good knowledge of Greek myth and iconography, there is no evidence to indicate that these painters had immigrated from Attica. An exception to this may be the Praxia Painter, as Greek inscription on four of his vases may indicate that he originated from Greece.[27]

In Etruria, the pseudo-red-figure style was not just a phenomenon of the earliest phases, as it had been in Attica. Especially during the 4th century, some workshops specialised in this technique, although true red-figure painting was widespread among Etruscan workshops at the same time. Notable workshops include the Sokra Group and the Phantom Group. The Sokra Group, somewhat older, preferred bowls with interior decoration of Greek mythical themes, but also some Etruscan motifs. The phantom Group mainly painted cloaked figures combined with vegetal or palmette ornamentation. The workshops of both groups are suspected to have been in Caere, Falerii and Tarquinia. The Phantom Group produced until the early 3rd century BC. Like elsewhere, the changing tastes of the customers eventually led to the end of this style.[28]

Red-figure vase painting

[edit]

True red figure vase painting, i.e. vases where the red areas have been left unpainted, was introduced to Etruria near the end of the 5th century BC. The first workshops developed in Vulci and Falerii and produced also for the surrounding areas. It is likely that Attic masters were behind these early workshops, but a South Italian influence is evident, too. These workshops dominated the Etruscan market into the 4th century BC. Large and medium-sized vessels like kraters and jugs were decorated mostly with mythological scenes. In the course of the 4th century, the Falerian production began to eclipse that of Vulci. New centres of production developed in Chiusi and Orvieto. Especially the Tondo Group of Chiusi, producing mainly drinking vessels with interior depictions of dionysiac scenes, became important. During the second half of the century, Volterra became a main centre. Here, especially rod-handled kraters were produced and, especially in the early phases, painted elaborately.

During the 2nd half of the 4th century BC, mythological themes disappeared from the repertoire of Etruscan painters. They were replaced by female heads and scenes of up to two figures. Instead of figural depictions, ornaments and floral motifs covered the vessel bodies. Large figural compositions, like that on a krater by the Den Haag Funnel Group Painter were only produced exceptionally. The originally large-scale production at Falerii lost its dominant role to the production centre at Caere, which had probably been founded by Falerian painters and cannot be said to represent a distinct tradition. The standard repertoire of the Caere workshops included simply painted oinochoai, lekythoi and drinking bowls of the Torcop Group, and plates of the Genucuilia Group. The switch to the production of black glaze vases near the end of the 4th century, probably as a reaction to changing tastes of the time, spelt the end of Etruscan red-figure vase painting.[29]

Research and reception

[edit]

About 65,000 red-figure vases and vase fragments are known to have survived.[c] The study of ancient pottery and of Greek vase painting began already in the Middle Ages. Restoro d'Arezzo dedicated a chapter (Capitolo delle vasa antiche) of his description of the world to ancient vases (Della composizione del mondo, libro VIII, capitolo IV). He considered especially the clay vessels as perfect in terms of shape, colour, and artistic style.[30] Nevertheless, initially the attention focused on vases in general, and perhaps especially on stone vases. The first collections of ancient vases, including some painted vessels, developed during the Renaissance. We even know of some imports from Greece to Italy at that time. Still, until the end of the Baroque period, vase painting was overshadowed by other genres, especially by sculpture. A rare pre-Classicist exception is a book of watercolours depicting figural vases, which was produced for Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc. Like some of his contemporary collectors, Peiresc owned a number of clay vases.[31]

Since the period of Classicism, ceramic vessels were collected more frequently. For example, Sir William Hamilton[d] and Giuseppe Valletta had vase collections. Vases found in Italy were relatively affordable, so that even private individuals could assemble important collections. Vases were a popular souvenir for young Northwestern Europeans to bring home from the Grand Tour. In the diaries of his voyage to Italy,[e] Goethe refers to the temptation of buying ancient vases. Those who could not afford originals had the option of acquiring copies or prints. There were even manufactories specialised in imitating ancient pottery. The best known is Wedgwood ware, although it employed techniques entirely unrelated to those used in antiquity, using ancient motifs merely as a thematic inspiration.[32]

Since the 1760s, archaeological research also began to focus on vase paintings. The vases were appreciated as source material for all aspects of ancient life, especially for iconographical and mythological studies. Vase painting was now treated as a substitute for the almost entirely lost oeuvre of Greek monumental painting. Around this time, the widespread view that all painted vases were Etruscan works became untenable. Nonetheless, the artistic fashion of that time to imitate ancient vases came to be called all'etrusque. England and France tried to outdo each other in terms of both research and imitation of vases. The German aesthetic writers Johann Heinrich Müntz and Johann Joachim Winckelmann studied vase paintings. Winckelmann especially praised the Umrißlinienstil ("outline style", i.e. red-figure painting). Vase ornaments were compiled and disseminated in England through Pattern books.[33]

Vase paintings even had an influence on the development of modern painting. The linear style influenced artists such as Edward Burne-Jones, Gustave Moreau or Gustav Klimt. Around 1840, Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller painted a Still Life with Silver Vessels and Red-Figure Bell Krater. Henri Matisse produced a similar painting (Intérieur au vase étrusque). Their aesthetic influence extends into the present. For example, the well-known curved shape of the Coca-Cola bottle is inspired by Greek vases.[34]

The scientific study of Attic vase paintings was advanced especially by John D. Beazley. Beazley began to study the vases from about 1910 onwards, inspired by the methodology that the art historian Giovanni Morelli had developed for the study of paintings. He assumed that each painter produced individual works that can always be unmistakably ascribed. To do so, particular details, such as faces, fingers, arms, legs, knees, garment folds and so on, were compared. Beazley examined 65,000 vases and fragments (of which 20,000 were black-figure). In the course of six decades of study, he was able to ascribe 17,000 of them to individual artists. Where their names remained unknown, he developed a system of conventional names. Beazley also united and combined individual painters into groups, workshops, schools and styles. No other archaeologist has ever had as formative an influence on a whole subdiscipline as had Beazley on the study of Greek vase painting. A large proportion of his analysis is still considered valid today. Beazley first published his conclusions on red-figure vase painting in 1925 and 1942. His initial studies only considered material from before the 4th century BC. For a new edition of his work published in 1963, he also incorporated that later period, making use of the work of other scholars, such as Karl Schefold, who had especially studied the Kerch Style vases. Famous scholars who continued the study of Attic red-figure after Beazley include John Boardman, Erika Simon and Dietrich von Bothmer.[35]

For the study of South Italian case painting, Arthur Dale Trendall's work has a similar significance to that of Beazley for Attica. Most post-Beazley scholars can be said to follow Beazley's tradition and use his methodology.[f] The study of Greek vases is ongoing, not least because of the constant addition of new material from archaeological excavations, illicit excavations and unknown private collections.

See also

[edit]- Ancient Greek art

- List of Greek vase painters

- See also Liste der Formen, Typen und Varianten der antiken griechischen Fein- und Gebrauchskeramik in the German Wikipedia for a useful set of tables classifying vase shapes and variations, with distinguishing shape outlines and typical examples, also Typology of Greek vase shapes.

Notes, references and sources

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ John Boardman: The History of Greek Vases, London 2001, p. 286. The hollow needle, or syringe, was proposed by Noble (1965). First publication of the hair method by Gérard Seiterle: Die Zeichentechnik in der rotfigurigen Vasenmalerei. Das Rätsel der Relieflinien. In: Antike Welt 2/1976, S. 2–9.

- ^ Joseph Veach Noble: The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery. New York 1965. The Process was first rediscovered and published by Theodor Schumann: Oberflächenverzierung in der antiken Töpferkunst. Terra sigillata und griechische Schwarzrotmalerei. In: Berichte der deutschen keramischen Gesellschaft 32 (1942), S. 408–426. More references in Noble (1965).

- ^ Balbina Bäbler, in DNP 15/3 (Zeitrechnung: I. Klassische Archäologie, Sp. 1164) refers to 65.000 vases having been examined by Beazley. From that number, about 20.000 must be subtracted, since they were black-figure (Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, S. 7). 21.000 red-figure vases are known from Southern Italy. Additionally, there are some examples from other parts of Greece

- ^ Hamilton's first collection of "Etruscan" vases was lost at sea but memorialized in engravings; he formed a second collection that is conserved in the British museum.

- ^ 9. März 1787

- ^ The principal exceptions being David Gill and Michael Vickers who repudiate the significance of vase painting as an art form and reject the analogy of Renaissance artists' studios and the ancient Greek pottery workshop,[36] a view criticized by R.M. Cook.[37] Additionally James Whitley and Herbert Hoffmann have criticised Beazley's approach as being unduly "positivist" in that it concentrates exclusively on aspects of connoisseurship at the cost of ignoring the larger social and cultural context that might have influenced the practice of vase painting.[38][39]

References

[edit]- ^ John Boardman: Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Archaic Period,1975, p. 15-16

- ^ a b John H. Oakley: Rotfigurige Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 10 (2001), col. 1141

- ^ a b c d e Oakley: Rotfigurige Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 10 (2001), col. 1142

- ^ a b Oakley: Rotfigurige Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 10 (2001), col. 1143

- ^ Der Jenaer Maler, Reichert, Wiesbaden 1996, p. 3

- ^ Ingeborg Scheibler: Vasenmaler, in: DNP 12/I, Sp. 1148

- ^ a b Ingeborg Scheibler: Vasenmaler, in: DNP 12/I, col. 1147f.

- ^ Boardman: Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Classical Period,1989, p. 234

- ^ Ingeborg Scheibler: Vasenmaler, in: DNP 12/I, col. 1148

- ^ Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasenmalerei, p. 13; Martine Denoyelle: Euphronios. Vasenmaler und Töpfer, Berlin 1991, p. 17

- ^ see Alfred Schäfer: Unterhaltung beim griechischen Symposion. Darbietungen, Spiele und Wettkämpfe von homerischer bis in spätklassische Zeit, von Zabern, Mainz 1997

- ^ Boardman: Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Classical Period,1989 p. 237.

- ^ Boardman: Athenian Black Figure Vases,1991, p. 12

- ^ Boardman: Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Classical Period,1987, p. 222

- ^ Rolf Hurschmann: Unteritalische Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 12/1 (2002), col. 1009–1011

- ^ Hurschmann: Unteritalische Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 12/1 (2002), col. 1010 and Trendall p. 9, with slightly differing numbers.

- ^ Hurschmann: Apulische Vasen, in: DNP 1 (1996), col. 922f.

- ^ Hurschmann: Apulische Vasen, in: DNP 1 (1996), col. 923

- ^ Hurschmann in: DNP 1 (1996), col. 923

- ^ Hurschmann: Kampanische Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 6 (1998), col. 227

- ^ Hurschmann: Kampanische Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 6 (1998), col. 227f

- ^ a b Hurschmann: Kampanische Vasenmalerei, in: DNP 6 (1998), col. 228

- ^ Hurschmann: Lukanische Vasen, in: DNP 7 (1999), col. 491

- ^ Hurschmann: Paestanische Vasen, in: DNP 9 (2000), col. 142

- ^ Hurschmann: Paestanische Vasen, in: DNP 9 (2000), col. 142f.

- ^ a b Hurschmann: Sizilische Vasen, in: DNP 11 (2001), col. 606

- ^ Reinhard Lullies in Antike Kunstwerke aus der Sammlung Ludwig. Vol 1. Frühe Tonsarkophage und Vasen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, p. 178–181 ISBN 3-8053-0439-0.

- ^ Huberta Heres – Max Kunze (Hrsg.): Die Welt der Etrusker, Archäologische Denkmäler aus Museen der sozialistischen Länder. Exhibition catalogue Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Hauptstadt der DDR – Altes Museum vom 04. Oktober bis 30. Dezember 1988. Berlin 1988, p. 245-249

- ^ Huberta Heres – Max Kunze (Hrsg.): Die Welt der Etrusker, Archäologische Denkmäler aus Museen der sozialistischen Länder. Exhibition catalogue Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Hauptstadt der DDR – Altes Museum vom 04. Oktober bis 30. Dezember 1988. Berlin 1988, p. 249-263

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vasen/Vasenmalerei, in DNP 15/3, col. 946

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vasen/Vasenmalerei, in DNP 15/3, col. 947-949

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vasen/Vasenmalerei, in DNP 15/3, col. 949-950

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vasen/Vasenmalerei, in DNP 15/3, col. 951-954

- ^ Sabine Naumer: Vasen/Vasenmalerei, in DNP 15/3, col. 954

- ^ John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, p. 7f.

- ^ Vickers, Michael; Gill, David (1994). Artful Crafts: Ancient Greek silverware and pottery. Oxford; New York: Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press. OCLC 708421572.

- ^ Cook, R.M. (1987). "'Artful crafts': A commentary". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 107. Oxford: Cambridge University Press: 169–171. doi:10.2307/630079. JSTOR 630079. S2CID 161909935.

- ^ Whitley, James (1998). "Beazley as theorist". Antiquity. 73 (271). Antiquity Publications Ltd: 40–47. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00084520. S2CID 162478619.

- ^ Hoffmann, Herbert (1979). Fehr, Burkhard; Meyer, Klaus-Heinrich; Schalles, Hans-Joachim; Schneider, Lambert (eds.). "In the wake of Beazley: Prolegomena to an Anthropological Study of Greek Vase-Painting" (PDF). Hephaistos. 1. Archäologisches Institut, University of Hamburg: 61–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Beazley, John Davidson (1963) [1946]. Attic Red-figure vase-painters (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 419228649.

- Boardman, John (1994) [1981]. Rotfigurige Vasen aus Athen: die archaische Zeit: ein Handbuch [Red-figure vases from Athens: the archaic times: a handbook]. Kulturgeschichte der antiken Welt (in German). Vol. 4 (4th ed.). Mainz: von Zabern. ISBN 3805302347.

- Boardman, John (1991) [1981]. Rotfigurige Vasen aus Athen: die archaische Zeit: ein Handbuch [Red-figure vases from Athens: the archaic times: a handbook]. Kulturgeschichte der antiken Welt (in German). Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). Mainz: von Zabern. ISBN 3805312628.

- Fless, Friederike (2002). Rotfigurige Keramik als Handelsware: Erwerb und Gebrauch attischer Vasen im mediterranen und pontischen Raum während des 4. Jhs. v. Chr [Red-figure pottery as a commodity: Acquisition and use of attic vases in the mediterranean and pontic region during the 4th century BC]. Internationale Archäologie (in German). Vol. 71. Rahden: Leidorf. ISBN 3896463438.

- Giuliani, Luca (1995). Tragik, Trauer und Trost: Bildervasen für eine apulische Totenfeier [Tragic, grief and consolation: Vase images for an apulian funeral feast] (in German). Berlin: Staatliche Museen. OCLC 878870139.

- Rolf Hurschmann: Apulische Vasen

, in: DNP 1 (1996), col. 922 f.; Kampanische Vasenmalerei

, in: DNP 1 (1996), col. 922 f.; Kampanische Vasenmalerei , in: DNP 6 (1998), col. 227 f.; Lukanische Vasen

, in: DNP 6 (1998), col. 227 f.; Lukanische Vasen , in: DNP 7 (1999), col. 491; Paestanische Vasen

, in: DNP 7 (1999), col. 491; Paestanische Vasen , in: DNP 9 (2000), col. 142/43; Sizilische Vasen

, in: DNP 9 (2000), col. 142/43; Sizilische Vasen , in: DNP 11 (2001), col. 606; Unteritalische Vasenmalerei

, in: DNP 11 (2001), col. 606; Unteritalische Vasenmalerei , in: DNP 12/1 (2002), col. 1009–1011

, in: DNP 12/1 (2002), col. 1009–1011 - Mannack, Thomas (2002). Griechische Vasenmalerei [Greek vase painting] (in German) (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft ed.). Stuttgart; Darmstadt: Theiss. ISBN 3806217432.

- Sabine Naumer: Vasen/Vasenmalerei

, in DNP 15/3, col. 946-958

, in DNP 15/3, col. 946-958 - John H. Oakley: Rotfigurige Vasenmalerei

, in: DNP 10 (2001), col. 1141–43

, in: DNP 10 (2001), col. 1141–43 - Reusser, Christoph (2002). Vasen für Etrurien: Verbreitung und Funktionen attischer Keramik im Etrurien des 6. und 5. Jahrhunderts vor Christus [Vases for Etruria: Proliferation and function of Attic ceramics in 6th and 5th century BC Etruria] (habilitation thesis). Akanthus crescens (in German). Vol. 5. Zürich: Akanthus. ISBN 3905083175.

- Scheibler, Ingeborg (1995). Griechische Töpferkunst. Herstellung, Handel und Gebrauch der antiken Tongefäße [Greek pottery. Production, trade and use of antique clay vessels] (in German) (2nd ed.). Munich: Beck. ISBN 9783406393075.

- Ingeborg Scheibler: Vasenmaler

, in: DNP 12/I (2002), col. 1147f.

, in: DNP 12/I (2002), col. 1147f. - Simon, Erika; Hirmer, Max (1981). Die griechischen Vasen [The Greek vases] (in German) (2nd ed.). Munich: Hirmer. ISBN 3777433101.

- Trendall, Arthur Dale (1991). Rotfigurige Vasen aus Unteritalien und Sizilien: Ein Handbuch [Red-figure vases from Lower Italy and Sicily: A handbook]. Kulturgeschichte der Antiken Welt (in German). Vol. 47. Mainz: P. von Zabern. ISBN 3805311117.

Further reading

[edit]- Boardman, John. 2001. The History of Greek Vases: Potters, Painters, Pictures. New York: Thames & Hudson.

- Bouzek, Jan. 1990. Studies of Greek Pottery In the Black Sea Area. Prague: Charles University.

- Cook, Robert Manuel, and Pierre Dupont. 1998. East Greek Pottery. London: Routledge.

- Farnsworth, Marie. 1964. "Greek Pottery: A Mineralogical Study." American Journal of Archaeology 68 (3): 221–28.

- Sparkes, Brian A. 1996. The Red and the Black: Studies In Greek Pottery. London: Routledge.

- Von Bothmer, Dietrich (1987). Greek vase painting. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-084-5.

External links

[edit]- The Beazley archive – searchable archive of Attic vase paintings Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- The Trendall archive – South Italian vase paintings Archived 2007-12-18 at the Wayback Machine