Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Retirement

View on Wikipedia

Retirement is the withdrawal from one's position or occupation or from one's active working life.[1] A person may also semi-retire by reducing work hours or workload.

Many people choose to retire when they are elderly or incapable of doing their job for health reasons. People may also retire when they are eligible for private or public pension benefits, although some are forced to retire when bodily conditions no longer allow the person to work any longer (by illness or accident) or as a result of legislation concerning their positions.[2] In most countries, the idea of retirement is of recent origin, being introduced during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Previously, low life expectancy, lack of social security and the absence of pension arrangements meant that most workers continued to work until their death. Germany was the first country to introduce retirement benefits in 1889.[3]

Nowadays, most developed countries have systems to provide pensions on retirement in old age, funded by employers or the state. However, only about 15% of private industry workers in the US had access to a traditional defined benefit pension plan as of March 2023.[4]These plans, often called pensions, are increasingly rare, especially in the private sector, as most companies now offer defined contribution plans like 401(k)s instead.[5] Public sector workers have much higher pension coverage, with about 75% participating in pension plans [6]

In many poorer countries, there is no support for the elderly beyond that provided through the family. Today, retirement with a pension is considered a right of the worker in many societies; hard ideological, social, cultural and political battles have been fought over whether this is a right. In many Western countries, this is a right embodied in national constitutions.

An increasing number of individuals are choosing to put off this point of total retirement, by selecting to exist in the emerging state of pre-tirement.[7]

History

[edit]Retirement, or the practice of leaving one's job or ceasing to work after reaching a certain age, has been around since around the 18th century. Prior to the 18th century, humans had an average life expectancy between 26 and 40 years.[8][9][10][11] In consequence, only a small percentage of the population reached an age where physical impairments began to be obstacles to working.[12] Countries began to adopt government policies on retirement during the late 19th century and the 20th century, beginning in Germany under Otto von Bismarck.[13]

Retirement age

[edit]

A person may retire at whatever age they please. However, a country's tax laws or state old-age pension rules usually mean that in a given country a certain age is thought of as the standard retirement age. As life expectancy increases and more and more people live to an advanced age, in many countries the retirement age at which the public pension is awarded has been increased in the 21st century, often progressively.[14]

The standard retirement age varies from country to country but it is generally between 50 and 70 (according to latest statistics, 2011). In some countries this age is different for men and women, although this has recently been challenged in some countries (e.g., Austria), and in some countries the ages are being brought into line.[15] The table below shows the variation in eligibility ages for public old-age benefits in the United States and many European countries, according to the OECD.

The retirement age in many countries is increasing, often starting in the 2010s and continuing until the late 2020s.

| Country | Early retirement age | Normal retirement age | Employed, 55–59 | Employed, 60–64 | Employed, 65–69 | Employed, 70+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 60 (57) | 65 (60) | 39% | 7% | 1% | 0% |

| Belgium | 60 | 65 | 45% | 12% | 1% | 0% |

| Cambodia | 50 | 55 | 16% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| Denmark 1 | 60–65[16] | 65–68[17] | 77% | 35% | 9% | 3% |

| France 2 | 62 | 65 | 51% | 12% | 1% | 0% |

| Germany | 65 | 67 | 61% | 23% | 3% | 0% |

| Greece | 58 | 67[18] | 65% | 18% | 4% | 0% |

| Italy | 57 | 67 | 26% | 12% | 1% | 0% |

| Latvia 3 | none | 63–65[19] | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Netherlands | 60 | 65 (67) | 53% | 22% | 3% | 0% |

| Norway | 62 | 67 | 74% | 33% | 7% | 1% |

| Spain 4 | 60 | 65 | 46% | 22% | 0% | 0% |

| Sweden | 61 | 65 | 78% | 58% | 5% | 1% |

| Switzerland | 63 (61), [58] | 65 (64) | 77% | 46% | 7% | 2% |

| Thailand | 50 | 60 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| United Kingdom | 65 | 68 | 69% | 40% | 10% | 2% |

| United States 5 | 62 | 67 | 66% | 43% | 20% | 5% |

| Kenya | 50 | 55 | 66% | 43% | 20% | 5% |

Notes: Parentheses indicate eligibility age for women when different. Sources: Cols. 1–2: OECD Pensions at a Glance (2005), Cols. 3–6: Tabulations from HRS, ELSA and SHARE. Square brackets indicate early retirement for some public employees.

1 In Denmark, early retirement is called efterløn and there are some requirements to be met such as contributing to the labor market for at least 20 years.[20] Early and normal retirement ages vary according to the date of birth of the person filing for retirement.[16][17]

2 In France, the retirement age was 60, with full pension entitlement at 65; in 2010 this was extended to 62 and 67 respectively, increasing progressively over the following eight years.[21]

3 In Latvia, the retirement age depends on the date of birth of the person filing for retirement.[19]

4 In Spain it was ruled that the retirement age was to increase from 65 to 67 progressively from 2013 to 2027.[22]

5 In the United States, while the normal retirement age for Social Security, or Old Age Survivors Insurance (OASI) was age 65 to receive unreduced benefits, it is gradually increasing to age 67 by 2027.[14] Public servants are often not covered by Social Security but have their own pension programs. Police officers in the United States may typically retire at half pay after 20 years of service, or three-quarter pay after 30 years, allowing retirement from the early forties.[23] Military members of the US Armed Forces may elect to retire after 20 years of active duty. (See also: military retirement pay and military pension.)

Iranian age of retirement was increased much in 2022 and 2023 to 42 years of work insurance payment record to avoid government social security bankruptcy.[24]

Data sets

[edit]Recent advances in data collection have vastly improved the ability to understand important relationships between retirement and factors such as health, wealth, employment characteristics and family dynamics, among others. The most prominent study for examining retirement behavior in the United States is the ongoing Health and Retirement Study (HRS), first fielded in 1992. The HRS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey of adults in the U.S. ages 51+, conducted every two years, and contains a wealth of information on such topics as labor force participation (e.g., current employment, job history, retirement plans, industry/occupation, pensions, disability), health (e.g., health status and history, health and life insurance, cognition), financial variables (e.g., assets and income, housing, net worth, wills, consumption and savings), family characteristics (e.g., family structure, transfers, parent/child/grandchild/sibling information) and a host of other topics (e.g., expectations, expenses, internet use, risk taking, psychosocial, time use).[25]

2002 and 2004 saw the introductions of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) and the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), which includes respondents from 14 continental European countries plus Israel. These surveys were closely modeled after the HRS in the sample frame, design and content. A number of other countries (e.g., Japan, South Korea) also now field HRS-like surveys, and others (e.g., China, India) are currently fielding pilot studies. These data sets have expanded the ability of researchers to examine questions about retirement behavior by adding a cross-national perspective.

| Study | First wave | Eligibility age | Representative year/last wave | Sample size: households | Sample size: individuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) | 1992 | 51+ | 2006 | 12,288 | 18,469 |

| Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) | 2001 | 50+ | 2003 | 8,614 | 13,497 |

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | 2002 | 50+ | 2006 | 6,484 | 9,718 |

| Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) | 2004 | 50+ | 2006 | 22,255 | 32,442 |

| Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA) | 2006 | 45+ | 2006 | 6,171 | 10,254 |

| Japanese Health and Retirement Study (JHRS) | 2007 | 45–75 | 2007 | Est. 10,000 | |

| WHO Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) | 2007 | 50+/18–49 | 2007 | Est. 5,000/1,000 | |

| Chinese Health and Retirement Study (CHARLS) | pilot 2008 | 45+ | 2008 | Est. 1,500 | Est. 2,700 |

| Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) | pilot 2009 | 45+ | 2009 | Est. 2,000 | |

Notes: MHAS discontinued in 2003; ELSA numbers exclude institutionalized (nursing homes). Source: Borsch-Supan et al., eds. (November 2008). Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (2004–2007): Starting the Longitudinal Dimension.

Factors affecting retirement decisions

[edit]

Many factors affect people's retirement decisions. Retirement funding education is a big factor that affects the success of an individual's retirement experience. Social Security plays an important role because most individuals solely rely on Social Security as their only retirement option, when Social Security's trust funds are expected to be depleted by 2034.[26] Knowledge affects an individual's retirement decisions by simply finding more reliable retirement options such as Individual Retirement Accounts or Employer-Sponsored Plans. In countries around the world, people are much more likely to retire at the early and normal retirement ages of the public pension system (e.g., ages 62 and 65 in the U.S.).[27] This pattern cannot be explained by different financial incentives to retire at these ages since typically retirement benefits at these ages are approximately actuarially fair; that is, the present value of lifetime pension benefits (pension wealth) conditional on retiring at age a is approximately the same as pension wealth conditional on retiring one year later at age a+1.[28] Nevertheless, a large literature has found that individuals respond significantly to financial incentives relating to retirement (e.g., to discontinuities stemming from the Social Security earnings test or the tax system).[29][30][31]

Greater wealth tends to lead to earlier retirement since wealthier individuals can essentially "purchase" additional leisure. Generally, the effect of wealth on retirement is difficult to estimate empirically since observing greater wealth at older ages may be the result of increased saving over the working life in anticipation of earlier retirement. However, many economists have found creative ways to estimate wealth effects on retirement and typically find that they are small. For example, one paper exploits the receipt of an inheritance to measure the effect of wealth shocks on retirement using data from the HRS.[32] The authors find that receiving an inheritance increases the probability of retiring earlier than expected by 4.4 percentage points, or 12 percent relative to the baseline retirement rate, over an eight-year period.

A great deal of attention has surrounded how the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent Great Recession are affecting retirement decisions, with the conventional wisdom saying that fewer people will retire since their savings have been depleted; however recent research suggests that the opposite may happen. Using data from the HRS, researchers examined trends in defined benefit (DB) vs. defined contribution (DC) pension plans and found that those nearing retirement had only limited exposure to the recent stock market decline and thus are not likely to substantially delay their retirement.[33] At the same time, using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), another study estimates that mass layoffs are likely to lead to an increase in retirement almost 50% larger than the decrease brought about by the stock market crash, so that on net retirements are likely to increase in response to the crisis.[34]

More information tells of how many who retire will continue to work, but not in the career they have had for the majority of their life. Job openings will increase in the next 5 years due to retirements of the baby boomer generation. The Over 50 population is actually the fastest growing labor groups in the US.

A great deal of research has examined the effects of health status and health shocks on retirement. It is widely found that individuals in poor health generally retire earlier than those in better health. This does not necessarily imply that poor health status leads people to retire earlier, since in surveys retirees may be more likely to exaggerate their poor health status to justify their earlier decision to retire. This justification bias, however, is likely to be small.[35] In general, declining health over time, as well as the onset of new health conditions, have been found to be positively related to earlier retirement.[36] Health conditions that can cause someone to retire include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea, joint diseases, and hyperlipidemia.[37]

Most people are married when they reach retirement age; thus, spouse's employment status may affect one's decision to retire. On average, husbands are three years older than their wives in the U.S., and spouses often coordinate their retirement decisions. Thus, men are more likely to retire if their wives are also retired than if they are still in the labor force, and vice versa.[38][39]

EU member states

[edit]Researchers analyzed factors affecting retirement decisions in EU member states:

- Alba-Ramirez (1997) uses micro data from the Active Population Survey of Spain and logit model for analyzing determinants of retirement decision and finds that having more members in the household, and as well as children, has a negative effect on the probability of retirement among older males. This is an intuitive result as males in bigger household with children have to earn more and pension benefits will be less than needed for household.[40]

- Antolin and Scarpetta (1998) using German Socio-Economic Panel and hazard model find that Socio-demographic factors such as health and gender have a strong impact on the retirement decision: women tend to retire earlier than men, and poor health makes people go into retirement, particularly in the case of disability retirement. The relationship between health status and retirement is significant for both self-assessed and objective indicators of health status.[41] This is similar finding to the previous research of Blau and Riphahn (1997); using individual data from the German Socio-Economic Panel as well, but controlling for different variables they found that if individual has chronic health condition, then he tends to retire.[42] Antolin and Scarpetta (1998) use better measure for health status than Blau and Riphahn (1997), because self-assessed and objective indicators of health status are better measures than chronic health condition.[41]

- Blöndal and Scarpetta (1999) find significant effect of socio-demographic factors on the retirement decision. Men tend to retire later than women as women try to benefit from special early retirement schemes in Germany and the Netherlands. Another reason is that they get access to pensions earlier than men as standard age of entitlement to pension is lower for women compared with men in Italy and the United Kingdom. The other interesting finding is that retirement depends on household size: heads of large households prefer not to retire. They think that this can be because of the significance of wages in large households compared with smaller ones and insufficiency of pension benefits. Another finding is that health status is significant factor in all early retirements; poor health conditions are especially significant if respondents join to disability benefit scheme. This result is true for both indicators used to express health status (self assessment and objective indicators).[43] This research is similar to Antolin and Scarpetta (1998) and shows similar results extending sample and implications from Germany to OECD.

- Murray et al. (2016, 2019) have shown that in the United Kingdom local labour markets of where workers live effects later life work exit.[44][45] In the first study, older workers aged 50 to 75 were more likely to exit the workforce over 10 years (years 2011–2011) if they had lived in a more deprived local authority in 2001. For respondents that identified as sick/disabled in 2011, effects of local area unemployment in 2001 were stronger for respondents who had better self-rated health in 2001.[44] The second study used the 1946 Birth Cohort to show that it's not just area unemployment near retirement age that matters for the ages workers retire: higher area unemployment at age 26 was associated with poorer health and lower likelihood of employment at aged 53; and these two individual pathways were identified as the key mediators between area unemployment and retirement age.[45]

- Rashad Mehbaliyev (2011)[46] analyzed how different factors related with health, demographics, behavior, financial status, and macroeconomics can affect retirement status in European Union countries for data collected from the SHARE Wave 2 dataset (Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe)[47] and UN sources. He found that males are less likely to be retired compared with females in New Member States, which is the opposite result than he found for Old Member States.[48] He explained that:[49] "The reasons for these results can be the facts that significant gender wage gap exists in New Member States,[50] household sizes are bigger in these countries than in Old Member States[51] and males play important role in household income which make them retire less than females."[52]

United States

[edit]

- Quinn et al. (1998) find significant correlation between health status and retirement status. They transform answers for question about health status from five levels ("excellent", "very good", "good", "fair" and "poor") into three levels and report results for three groups of people. 85% of respondents who answered "excellent" or "very good" to the question about their health in 1992 were still working two years after this interview, compared to 82% of those who answered "good", and 70% of those answered "fair" or "poor". This fact is also true for year 1996: 73% of people from the first group were still on the job market, while this is 66% and 55% for other groups of people.[54] However, Dhaval, Rashad and Spasojevic (2006) using data from six waves of Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) show that relationship between retirement and health status can imply the opposite effect in reality: physical and mental health decline after retirement.[55]

- Benitez-Silva (2000) analyzes determinants of labor force status and retirement process among elderly US citizens and possibility of decision returning to work using logit and probit models. He uses Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) for this purpose and finds that physical and mental health has significant effect on becoming employed. Male respondents are more likely to change their status from being not-employed to employed, but being insured has a negative effect on switching job status from “not-employed" to "employed" for people aged 60–62 and insignificant effect for 55–59 and aged over 63.[56]

Income for retirement

[edit]

Income after retirement can come from state pensions, occupational pensions, private savings and investments (private pension funds, owned housing), donations (e.g., by children), and social benefits.[58] Pension plans can be categorized as funded or pay-as-you-go.

Provision of pay-as-you-go state pensions for can be a significant drain on a government's budget, which can lead to pension underfunding.

Older people are more prone to sickness, and the cost of health care in retirement is large. Most countries provide universal health insurance coverage for seniors, although in the United States many people retire before they become eligible for Medicare health cover at 65 years of age.

Funded pension: size of lump sum required

[edit]In case of funded pensions, to pay for pension, assumed for simplicity to be received at the end of each year, and taking discounted values in the manner of a net present value calculation, the ideal lump sum available at retirement should be:

- (1 – zprop ) R repl S {(1+ ireal ) −1+(1+ ireal ) −2 +... ....+ (1+ ireal ) −p} = (1-zprop ) R repl S {(1 – (1+ireal)−p )/ireal}

Above is the standard mathematical formula for the sum of a geometric series. (Or if ireal =0 then the series in braces sums to p since it then has p equal terms). As an example, assume that S=60,000 per year and that it is desired to replace Rrepl=0.80, or 80%, of pre-retirement living standard for p=30 years. Assume for current purposes that a proportion z prop=0.25 (25%) of pay was being saved. Using ireal=0.02, or 2% per year real return on investments, the necessary lump sum is given by the formula as (1–0.25)*0.80*60,000*annuity-series-sum(30)=36,000*22.396=806,272 in the nation's currency in 2008–2010 terms. To allow for inflation in a straightforward way, it is best to talk of the 806,272 as being '13.43 years of retirement age salary'. It may be appropriate to regard this as being the necessary lump sum to fund 36,000 of annual supplements to any employer or government pensions that are available. It is common to not include any house value in the calculation of this necessary lump sum, so for a homeowner the lump sum pays primarily for non-housing living costs.

At retirement, the following amount will have been accumulated:

- zprop S {(1+ i rel to pay )w-1+(1+ i rel to pay )w-2 +... ....+ (1+ i rel to pay )+ 1 }

- = zprop S ((1+i rel to pay)w- 1)/i rel to pay

To make the accumulation match with the lump sum needed to pay pension:

- zprop S (((1+i rel to pay )) w – 1)/i rel to pay = (1-zprop ) R repl S (1 – ((1+i real)) −p )/i real

Bring zprop to the left hand side to give the answer, under this rough and unguaranteed method, for the proportion of pay that should be saved:

- zprop = R repl (1 – ((1+i real )) −p )/i real / [(((1+i rel to pay )) w – 1)/i rel to pay + R repl (1 – ((1+i real )) −p )/i real ] (Ret-03)

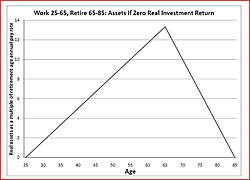

Note that the special case i rel to pay =0 = i real means that the geometric series should be summed by noting that there are p or w identical terms and hence z prop = p/(w+p). This corresponds to the graph above with the straight line real-terms accumulation.

Sample results

[edit]The result for the necessary zprop given by (Ret-03) depends critically on the assumptions made. As an example, one might assume that price inflation will be 3.5% per year forever and that one's pay will increase only at that same rate of 3.5%. If a 4.5% per year nominal rate of interest is assumed, then (using 1.045/1.035 in real terms) pre-retirement and post-retirement net interest rates will remain the same, irel to pay = 0.966 percent per year and ireal = 0.966 percent per year. These assumptions may be reasonable in view of the market returns available on inflation-indexed bonds, after expenses and any tax. Equation (Ret-03) is readily coded in Excel and with these assumptions gives the required savings rates in the accompanying picture.

Annuity

[edit]The problem that the lifespan is not known in advance can be reduced by the purchase at retirement of an inflation-indexed life annuity. Inflation-adjusted annuities are designed to provide income that rises with inflation, helping retirees maintain purchasing power over time.[59]

Calculators

[edit]A useful and straightforward calculation can be done if it is assumed that interest, after expenses, taxes, and inflation is zero. Assume that in real (after-inflation) terms, one's salary never changes over w years of working life. During p years of pension, one has a living standard that costs a replacement ratio R times as much as one's living standard in working life. The working life living standard is one's salary minus the proportion of salary Z that should be saved. Calculations are per unit salary (e.g., assume salary = 1).

Then after w years work, retirement age accumulated savings = wZ. To pay for pension for p years, necessary savings at retirement = Rp(1-Z)

Equate these: wZ = Rp(1-Z) and solve to give Z = Rp / (w + Rp). For example, if w = 35, p = 30 and R = 0.65, a proportion Z = 35.78% should be saved.

Retirement calculators generally accumulate a proportion of salary up to retirement age. This shows a straightforward case, which nonetheless could be practically useful for optimistic people hoping to work for only as long as they are likely to be retired.

For more complicated situations, there are several online retirement calculators on the Internet. Many retirement calculators project how much an investor needs to save, and for how long, to provide a certain level of retirement expenditures. Some retirement calculators, appropriate for safe investments, assume a constant, unvarying rate of return. Monte Carlo retirement calculators take volatility into account and project the probability that a particular plan of retirement savings, investments, and expenditures will outlast the retiree. Retirement calculators vary in the extent to which they take taxes, social security, pensions, and other sources of retirement income and expenditures into account.

The assumptions keyed into a retirement calculator are critical. One of the most important assumptions is the assumed rate of real (after inflation) investment return. A conservative return estimate could be based on the real yield of Inflation-indexed bonds offered by some governments, including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. The TIP$TER retirement calculator projects the retirement expenditures that a portfolio of inflation-linked bonds, coupled with other income sources like Social Security, would be able to sustain. Current real yields on United States Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) are available at the US Treasury site. Current real yields on Canadian 'Real Return Bonds' are available at the Bank of Canada's site. As of December 2011, US Treasury inflation-linked bonds (TIPS) were yielding about 0.8% real per annum for the 30-year maturity and a noteworthy slightly negative real return for the 7-year maturity.

Many individuals use "retirement calculators" on the Internet to determine the proportion of their pay they should be saving in a tax advantaged-plan (e.g., IRA or 401-K in the US, RRSP in Canada, personal pension in the UK, superannuation in Australia). After expenses and any taxes, a reasonable (though arguably pessimistic) long-term assumption for a safe real rate of return is zero. So in real terms, interest does not help the savings grow. Each year of work must pay its share of a year of retirement. For someone planning to work for 40 years and be retired for 20 years, each year of work pays for itself and for half a year of retirement. Hence, 33.33% of pay must be saved, and 66.67% can be spent when earned. After 40 years of saving 33.33% of pay, we have accumulated assets of 13.33 years of pay, as in the graph. In the graph to the right, the lines are straight, which is appropriate given the assumption of a zero real investment return.

The graph above can be compared with those generated by many retirement calculators. However, most retirement calculators use nominal (not "real" dollars) and therefore require a projection of both the expected inflation rate and the expected nominal rate of return. One way to work around this limitation is to, for example, enter "0% return, 0% inflation" inputs into the calculator. The Bloomberg retirement calculator gives the flexibility to specify, for example, zero inflation and zero investment return and to reproduce the graph above. The MSN retirement calculator in 2011 has as the defaults a realistic 3% per annum inflation rate and optimistic 8% return assumptions; consistency with the December 2011 US nominal bond and inflation-protected bond market rates requires a change to about 3% inflation and 4% investment return before and after retirement.

Ignoring tax, someone wishing to work for a year and then relax for a year on the same living standard needs to save 50% of pay. Similarly, someone wishing to work from age 25 to 55 and be retired for 30 years till 85 needs to save 50% of pay if government and employment pensions are not a factor and if it is considered appropriate to assume a zero real investment return.

A newer method for determining the adequacy of a retirement plan is Monte Carlo simulation. This method has been gaining popularity and is now employed by many financial planners.[60] Monte Carlo retirement calculators[61][62] allow users to enter savings, income and expense information and run simulations of retirement scenarios. The simulation results show the probability that the retirement plan will be successful.

Early retirement

[edit]Retirement is generally considered to be "early" if it occurs before the age (or tenure) needed for eligibility for support and funds from government or employer-provided sources. Early retirees typically rely on their own savings and investments to be self-supporting, either indefinitely or until they begin receiving external support. Early retirement can also be used as a euphemistic term for being terminated from employment before typical retirement age.[63]

Savings needed

[edit]The withdrawal rate from the portfolio depends on the remaining life expectancy.[65][66]

Those contemplating early retirement will want to know if they have enough to survive possible bear markets. The history of the US stock market shows that one would need to live on about 4% of the initial portfolio per year to ensure that the portfolio is not depleted before the end of the retirement;[67] this rule of thumb is a summary of one conclusion of the Trinity study, though the report is more nuanced and the conclusions and very approach have been heavily criticized (see Trinity study for details). This allows for increasing the withdrawals with inflation to maintain a consistent spending ability throughout the retirement, and to continue making withdrawals even in dramatic and prolonged bear markets.[68] (The 4% figure does not assume any pension or change in spending levels throughout the retirement.)

When retiring prior to age 59+1⁄2, there is a 10% IRS penalty on withdrawals from a retirement plan such as a 401(k) plan or a Traditional IRA. Exceptions apply under certain circumstances. At age 59 and six months, the penalty-free status is achieved and the 10% IRS penalty no longer applies.

To avoid the 10% penalty prior to age 59+1⁄2, a person should consult a lawyer about the use of IRS rule 72 T. This rule must be applied for with the IRS. It allows the distribution of an IRA account prior to age 59+1⁄2 in equal amounts of a period of either 5 years or until the age of 59+1⁄2, whichever is the longest time period, without a 10% penalty. Taxes still must be paid on the distributions.

Calculations using actual numbers

[edit]Although the 4% initial portfolio withdrawal rate described above can be used as a rough gauge, it is often desirable to use a retirement planning tool that accepts detailed input and can render a result that has more precision. Some of these tools model only the retirement phase of the plan while others can model both the savings or accumulation phase as well as the retirement phase of the plan. For example, an analysis by Forbes reckoned that in 90% of historical markets, a 4% rate would have lasted for at least 30 years, while in 50% of the historical markets, a 4% rate would have been sustained for more than 40 years.[69]

The effects of making inflation-adjusted withdrawals from a given starting portfolio can be modeled with a downloadable spreadsheet[70] that uses historical stock market data to estimate likely portfolio returns. Another approach is to employ a retirement calculator[71] that also uses historical stock market modeling, but adds provisions for incorporating pensions, other retirement income, and changes in spending that may occur during the course of the retirement.[72]

Life after retirement

[edit]Retirement might coincide with important life changes; a retired worker might move to a new location, for example a retirement community (Kamal et al., 2024), thereby having less frequent contact with their previous social context and adopting a new lifestyle. Often retirees volunteer for charities and other community organizations. Tourism is a common marker of retirement and for some becomes a way of life, such as for so-called grey nomads. Some retired people even choose to go and live in warmer climates in what is known as retirement migration.

It has been found that Americans have six lifestyle choices as they age: continuing to work full-time, continuing to work part-time, retiring from work and becoming engaged in a variety of leisure activities, retiring from work and becoming involved in a variety of recreational and leisure activities, retiring from work and later returning to work part-time, and retiring from work and later returning to work full-time.[73] An important note to make from these lifestyle definitions are that four of the six involve working. America is facing an important demographic change in that the Baby Boomer generation is now reaching retirement age. This poses two challenges: whether there will be a sufficient number of skilled workers in the work force, and whether the current pension programs will be sufficient to support the growing number of retired people.[74] The reasons that some people choose to never retire, or to return to work after retiring include not only the difficulty of planning for retirement but also wages and fringe benefits, expenditure of physical and mental energy, production of goods and services, social interaction, and social status may interact to influence an individual's work force participation decision.[73]

Often retirees are called upon to care for grandchildren and occasionally aged parents. For many it gives them more time to devote to a hobby or sport such as golf or sailing.

On the other hand, many retirees feel restless and suffer from depression as a result of their new situation. The newly retired are one of the most vulnerable social groups to become depressed most likely due to retirement coinciding with a deteriorating health status and increased care-giving responsibilities.[75] Retirement coincides with deterioration of one's health that correlates with increasing age and this likely plays a major role in increased rates of depression in retirees. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have shown that healthy elderly and retired people are as happy or happier and have an equal quality of life as they age as compared to younger employed adults, therefore retirement in and of itself is not likely to contribute to development of depression. Research around what retirees would ideally like to have a fulfilling life after retiring, found the most important factors were "physical comfort, social integration, contribution, security, autonomy and enjoyment".[76]

Many people in the later years of their lives, due to failing health, require assistance, sometimes in extremely expensive treatments – in some countries – being provided in a nursing home. Those who need care, but are not in need of constant assistance, may choose to live in a retirement home.

Research models

[edit]There are range of research models through which psychologists and other researchers attempt to understand retirement. These include:

- Multilevel model of retirement: the multilevel model of retirement is an organizational psychology approach that views retirements through three levels: societal, organizational, and individual level.[77][78][79][80]

- Temporal process model of retirement: the temporal process model of retirement is an organizational psychology approach that views retirements through three progressive phases: retirement planning, retirement decision making, and retirement transition and adjustment.[81][82][83]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of retirement" Merriam Websters

- ^ For example, in the United States, a person holding the rank of general or admiral must retire after 40 years of service unless he or she is reappointed to serve longer. (10 USC 636 Retirement for years of service: regular officers in grades above brigadier general and rear admiral (lower half))

- ^ "The German Precedent" Social Security History, US Social Security Administration

- ^ "15 percent of private industry workers had access to a defined benefit retirement plan". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 29 June 2025.

- ^ "Pension or 401(k)? Retirement Plan Trends in the U.S. Workplace". www.stlouisfed.org. Retrieved 29 June 2025.

- ^ "How many American workers participate in workplace retirement plans?". Pension Rights Center. Retrieved 29 June 2025.

- ^ "Britons opt for Pre-tirement over Total Retirement" (PDF).

- ^ Galor, Oded; Moav, Omer (2007). "The Neolithic Revolution and Contemporary Variations in Life Expectancy" (PDF). Brown University Working Paper. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Galor, Oded; Moav, Omer (2005). "Natural Selection and the Evolution of Life Expectancy" (PDF). Brown University Working Paper. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "A millennium of health improvement". BBC News. 27 December 1998. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ "Expectations of Life" by H.O. Lancaster (page 8)

- ^ "Aging in the Past". publishing.cdlib.org. Retrieved 29 June 2025.

- ^ Weisman, Mary-Lou (1999), "The History of Retirement, From Early Man to A.A.R.P.", The New York Times, retrieved 23 December 2016

- ^ a b SueKunkel. "Normal retirement age (NRA)". ssa.gov. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Turpin Distribution. Search". ebiz.turpin-distribution.com.

- ^ a b "Efterløn 2018" (in Danish). Ældresagen. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Hvornår kan jeg gå på folkepension?" (in Danish). borger.dk. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "Greece MPs approve new austerity budget amid protests". BBC News. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Pensijas vecuma paaugstināšana no 62 līdz 65 gadu vecumam" (in Latvian). The State Social Insurance Agency. 18 December 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "Efterløn 2024". Seniorfolk. 15 November 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ "Pension rallies hit French cities". BBC News. 7 September 2010.

- ^ Minder, Raphael (27 January 2011). "Spain to Raise Retirement Age to 67". The New York Times.

- ^ Michael Bucci (November 1992). "Police and firefighter pension plans". Monthly Labor Review. 115 (11). Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ "واکنشی به مصوبه افزایش سن بازنشستگی: ضد کارگریترین قانون معاصر ایران". 4 January 2024.

- ^ Juster, F. Thomas; Suzman, Richard (1995). "An Overview of the Health and Retirement Study". The Journal of Human Resources. 30 (Special Issue on the Health and Retirement Study: Data Quality and Early Results): S7 – S56. doi:10.2307/146277. JSTOR 146277.

- ^ "A SUMMARY OF THE 2021 ANNUAL REPORTS". www.ssa.gov. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Gruber, Jonathan and David Wise, eds. (1999). Social Security and Retirement around the World. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Gustman, Alan and Thomas Steinmeier (2003). "Retirement Effects of Proposals by the President's Commission to Strengthen Social Security." NBER Working Paper No. 10030

- ^ Feldstein, Martin and Jeffrey B. Liebman (2002). "Social Security," in Handbook of Public Economics, Vol. 4, Elsevier Press

- ^ Friedberg, Leora (2000). "The Labor Supply Effects of the Social Security Earnings Test." Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 82, No. 1, pp. 48–63

- ^ Liebman, Jeffrey B., Erzo F.P. Luttmer and David G. Seif (2008). "Labor Supply Responses to Marginal Social Security Benefits: Evidence from Discontinuities." NBER Working Paper No. 14540

- ^ Brown, Jeffrey R., Courtney Coile and Scott J. Weisbenner (2006). "The Effect of Inheritance Receipt on Retirement." NBER Working Paper No. 12386

- ^ Gustman, Alan; Steinmeier, Thomas; Tabatabai, Jahid (10–11 August 2009). How Do Pension Changes Affect Retirement Preparedness? The Trend to Defined Contribution Plans and the Vulnerability of the Retirement Age Population to the Stock Market Decline of 2008–2009 (PDF). 11th Annual Joint Conference of the Retirement Research Consortium. Washington, DC: National Press Club.

- ^ Coile, Courtney B. and Phillip B. Levine (2009). "The Market Crash and Mass Layoffs: How the Current Economic Crisis May Affect Retirement," presented at NBER Summer Institute Workshop on Aging, 21–25 July 2009.

- ^ Dwyer, Debra and Olivia Mitchell (1999). "Health problems as determinants of retirement: Are self-rated measures endogenous?" Journal of Health Economics, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 173–193

- ^ Dwyer, Debra and Jianting Hu (2000). "Retirement Expectations and Realizations: the Role of Health Shocks and Economic Factors," in Forecasting Retirement Needs and Retirement Wealth, Mitchell, Olivia, P. Brett Hammond and Anna Rappaport, eds.

- ^ Chosewood, L. Casey (3 May 2011). "When It Comes to Work, How Old Is Too Old?". NIOSH: Workplace Safety and Health. Medscape and NIOSH.

- ^ Blau, David M. (1998). "Labor Force Dynamics of Older Married Couples." Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 595–629

- ^ Gustman, Alan and Thomas Steinmeier (2000). "Retirement in Dual Career Families: A Structural Model." Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 503–545

- ^ Alba-Ramirez, A. 1997, "Labor Force Participation and Transitions of Older Workers in Spain", Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Working Paper 97-39, Economic series 17, May.

- ^ a b Antolín, P. and S. Scarpetta. 1998. "Microeconometric Analysis of the Retirement Decision: Germany”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 204, OECD Publishing

- ^ Blau, D. and R. Riphahn. 1997. “Labor Force Transitions of Older Married Couples in Germany”. Paper presented at International Health and Retirement Surveys Conference, Amsterdam, August.

- ^ Blöndal, S. and S. Scarpetta. 1997. Early retirement in OECD countries: The Role of Social Security Systems, OECD Economic Studies, issue 29, pages 7–54

- ^ a b Murray, Emily T.; Head, Jenny; Shelton, Nicola; Hagger-Johnson, Gareth; Stansfeld, Stephen; Zaninotto, Paola; Stafford, Mai (June 2016). "Local area unemployment, individual health and workforce exit: ONS Longitudinal Study". The European Journal of Public Health. 26 (3): 463–469. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckw005. ISSN 1101-1262. PMC 4884329. PMID 26922299.

- ^ a b Murray, Emily T.; Zaninotto, Paola; Fleischmann, Maria; Stafford, Mai; Carr, Ewan; Shelton, Nicola; Stansfeld, Stephen; Kuh, Diana; Head, Jenny (April 2019). "Linking local labour market conditions across the life course to retirement age: Pathways of health, employment status, occupational class and educational achievement, using 60 years of the 1946 British Birth Cohort" (PDF). Social Science & Medicine. 226: 113–122. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.038. PMID 30852391. S2CID 73725800.

- ^ Mehbaliyev, Rashad (2009). Determinants of retirement status: Comparative evidence from old and new EU member states (PDF) (Masters). Budapest: Central European University.

- ^ SHARE. "The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE): Other". share-project.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Mehbaliyev, Rashad (14 February 2012). Determinants of Retirement Status. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. ISBN 9783848407804 – via www.morebooks.de.

- ^ Production, bücher de IT and. "Determinants of Retirement Status". www.buecher.de.

- ^ "Determinants of Retirement Status". libreriauniversitaria.it. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Personal Loans- Law Books". lawbooks.com.au. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Mehbaliyev, Rashad (14 February 2012). Determinants of Retirement Status: Comparative Evidence from Old and New EU Member States. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. ISBN 978-3848407804.

- ^ a b "Actuarial Life Table". U.S. Social Security Administration Office of Chief Actuary. 2020. Archived from the original on 8 July 2023.

- ^ Quinn, J., R. Burkhauser, K. Cahill and R. Weather. 1998. "Microeconometric Analysis of the Retirement Decision: The United States”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 203

- ^ Dhaval, D., I. Rashad, and J. Spasojevic. 2006. “The Effects of Retirement on Physical and Mental Health Outcomes”, NBER Working Paper w12123

- ^ Benitez-Silva, H. 2000. "Micro Determinants of Labor Force Status Among Older Americans", SUNY-Stony Brook Department of Economics Working Papers 00-07

- ^ Dagher, Veronica; Tergesen, Anne; Ettenheim, Rosie (31 March 2023). "Here's What Retirement Looks Like in America in Six Charts". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023.

(For Average household retirement savings account balance:) Estimates of 401(k), IRA, Keogh and other defined contribution account balances based on 2019 data. Source: Employee Benefit Research Institute. . . . (For median net worth:) Source: Federal Reserve.

- ^ Eurofound, Income from work after retirement in the EU (2012) http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/pubdocs/2012/59/en/2/EF1259EN.pdf

- ^ Haithcock, Stan. "How Inflation-Adjusted Annuities Work". Stan The Annuity Man. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "A SURE BET? (Wealth Manager)". 11 June 2007. Archived from the original on 11 June 2007.

- ^ "Retirement calculator – easy, comprehensive, informative". 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011.

- ^ Online Monte Carlo Retirement Planner.

- ^ Larimore, Taylor. The Bogleheads' Guide to Retirement Planning. Wiley. p. 213.

- ^ "FIRECalc: Why another retirement calculator?". firecalc.com. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Clements, Jonathan (21 May 2006). "Make Sure Your Money Lasts as Long as You". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Dallas News: Breaking News for DFW, Texas, World". dallasnews.com. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Dallas News: Breaking News for DFW, Texas, World". dallasnews.com. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Retire Early's Safe Withdrawal Rates in Retirement". retireearlyhomepage.com. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Five Ways To Protect Your Retirement Income". Forbes. 4 March 2015. Archived from the original on 6 March 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ http://retireearlyhomepage.com/re60.html downloadable spreadsheet

- ^ FIRECalc: A different kind of retirement calculator.

- ^ "The Ultimate Retirement Calculator". retirement calculator that incorporates inflation, pensions and social security

- ^ a b Cox, H. (2012). Work/retirement choices and lifestyle patterns of older Americans. In L. Loeppke (Ed.), Annual editions: Aging (24th ed., pp. 74–83). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

- ^ Hardy, M. (2006). Older workers. In R. Binstock & L. George (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (6th ed., pp. 201–218). Boston, MA: Academic Press

- ^ Lee, Jinkook; Smith, James P. (1 June 2009). "Work, Retirement, and Depression". Journal of Population Ageing. 2 (1): 57–71. doi:10.1007/s12062-010-9018-0. ISSN 1874-7876. PMC 3655414. PMID 23687521.

- ^ Stephens, Christine; Breheny, Mary; Mansvelt, Juliana (3 June 2015). "Healthy ageing from the perspective of older people: A capability approach to resilience". Psychology & Health. 30 (6): 715–731. doi:10.1080/08870446.2014.904862. ISSN 0887-0446. PMID 24678916. S2CID 24424011.

- ^ Wang, Mo; Shi, Junqi (3 January 2014). "Psychological Research on Retirement". Annual Review of Psychology. 65 (1): 209–233. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115131. PMID 23751036.

- ^ Oleksiyenko, Olena; Życzyńska-Ciołek, Danuta (March 2018). "Structural Determinants of Workforce Participation after Retirement in Poland". Journal of Population Ageing. 11 (1): 83–103. doi:10.1007/s12062-017-9213-3. PMC 5813080. PMID 29492180.

- ^ Ones, Deniz S.; Anderson, Neil; Viswesvaran, Chockalingam; Sinangil, Handan Kepir (4 August 2021). "The Multilevel Nature of Retirement Management". The SAGE Handbook of Industrial, Work & Organizational Psychology, 3v: Personnel Psychology and Employee Performance; Organizational Psychology; Managerial Psychology and Organizational Approaches. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4739-4278-3.

- ^ Bal, P. Matthijs (5 July 2024). "The multilevel and temporal models of retirement". Elgar Encyclopedia of Organizational Psychology. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 620. ISBN 978-1-80392-176-1. Retrieved 8 July 2025.

- ^ Whitbourne, Susan K. (19 January 2016). "Retirement". The Encyclopedia of Adulthood and Aging, 3 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1227. ISBN 978-1-118-52892-1.

- ^ Ones, Deniz S.; Anderson, Neil; Viswesvaran, Chockalingam; Sinangil, Handan Kepir (4 August 2021). "Temporal process model of retirement". The SAGE Handbook of Industrial, Work & Organizational Psychology, 3v: Personnel Psychology and Employee Performance; Organizational Psychology; Managerial Psychology and Organizational Approaches. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4739-4278-3. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

- ^ Maree, Jacobus G. (20 July 2019). Handbook of Innovative Career Counselling. Springer. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-3-030-22799-9.

- ^ Kamal, Zarul (2024). "Pengeluaran Optimum dan Mampan: Aplikasi Pelan Caruman Tertakrif di Malaysia (Optimum and Sustainable Withdrawal: Application of Defined Contribution Plans in Malaysia)". Sains Malaysiana. 53 (53): 3639–3649. doi:10.17576/jsm-2024-5311-08.

Further reading

[edit]- Schultz, Ellen E., RETIREMENT HEIST: How Companies Plunder and Profit from the Nest Eggs of American Workers", Penguin Publishing, 2011

- Robert A. Stebbins (2013). Planning Your Time in Retirement: How to Cultivate a Leisure Lifestyle to Suit Your Needs and Interests. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-2160-4.

- Jamie P. Hopkins; David A. Littell; Kenn Beam Tacchino (July 2015). Planning for Retirement Needs, Thirteenth Edition. American College. ISBN 978-1-58293-230-9.

External links

[edit]- "Historical Development", Social Security Administration

- Short, Joanna, "Economic History of Retirement in the U.S.", 2010-02-01, Augustana College, Rock Island, Illinois

Retirement

View on GrokipediaConceptual Foundations

Definition and Etymology

Retirement denotes the withdrawal from one's occupation, position, or active working life, typically occurring at a specified age or after a defined period of service, with individuals thereafter relying on accumulated savings, investments, pensions, or other non-employment income sources for sustenance.[17][18] This transition marks the end of regular wage or salary earning through labor, enabling pursuits such as leisure, hobbies, or voluntary endeavors, though partial disengagement—semi-retirement—involving reduced hours or flexible arrangements also falls under broader interpretations.[19][20] The term originates from the mid-16th-century French retraite, a noun form of the verb retirer ("to draw back" or "withdraw"), combining re- (back) and tirer (to pull or draw), initially evoking military retreats or personal withdrawal for seclusion or safety.[21][22] Adopted into English around 1590, retirement first signified an act of retreating from action, danger, or public exposure, as in seeking privacy or receding from view; by the 1600s, it extended to withdrawal from societal or professional roles, with the sense of ceasing occupational work solidifying in the 18th century amid emerging notions of leisure after labor.[23][24] This linguistic evolution parallels the concept's historical rarity before industrialization, when low life expectancies and economic necessities precluded widespread withdrawal from work, rendering retirement as a mass phenomenon a late-19th-century innovation tied to state pensions, such as Germany's 1889 system under Otto von Bismarck, which set age-based eligibility to mitigate social unrest.[5][25]Economic and Social Implications

Retirement contributes to rising old-age dependency ratios, straining public finances as fewer working-age individuals support growing numbers of retirees. In OECD countries, the old-age dependency ratio—defined as individuals aged 65 or older per 100 working-age persons (20-64)—increased from 19% in 1980 to 31% in 2023, with projections reaching 52% by 2060 due to lower fertility rates and extended lifespans.[26] Globally, this ratio stood at approximately 30% in 2024, with advanced economies like Japan exceeding 50%, amplifying fiscal pressures on pension and healthcare expenditures.[27][28] In the United States, the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund faces depletion by 2033, after which incoming payroll taxes would cover only about 79% of scheduled benefits, necessitating reforms such as benefit cuts or tax increases absent policy changes.[29] Population aging reduces labor force participation rates, particularly among those over 60, leading to slower GDP growth; a RAND Corporation analysis estimates that a 10% increase in the population aged 60 and older decreases per capita GDP growth by 5.5%, with roughly two-thirds attributable to diminished labor productivity and one-third to reduced labor supply.[30] Retirees shift consumption patterns toward healthcare and leisure, potentially offsetting some labor shortages through sustained spending but increasing public sector liabilities, as evidenced by projections of added healthcare costs in developed nations.[31] Socially, retirement alters interpersonal networks, often substituting weaker ties (e.g., colleagues) with stronger familial bonds, which can enhance emotional support but risks isolation if family structures weaken.[32] This transition correlates with improved mental health and oral function in some cohorts, particularly through increased dental care access, though outcomes vary by socioeconomic status—high-income retirees report gains in well-being, while lower-income groups experience declines.[33][34] Social participation post-retirement mediates reductions in depression, underscoring the need for community engagement to mitigate risks of exclusion and identity loss from workforce exit.[35] Inequality persists, with 80% of U.S. households over age 60 financially struggling, linking lower retirement wealth to shorter lifespans—up to nine years less for the bottom income quintile—exacerbating intergenerational tensions and reliance on family or state support in aging societies.[36]Historical Evolution

Pre-Industrial Eras

In pre-industrial societies, spanning ancient civilizations to early modern agrarian economies before the late 18th century, formal retirement—defined as a planned cessation of work supported by institutional savings or pensions—did not exist as a widespread practice. Labor persisted as a lifelong necessity for survival, with individuals shifting to lighter tasks like supervision or household roles only when physical decline allowed, but rarely fully withdrawing from productive activity. Elderly support hinged on familial reciprocity, where able-bodied kin provided food, shelter, and care in exchange for prior contributions, inheritance rights, or ongoing minor labor from the aged.[37] In ancient Greece and Rome, kinship remained the primary safeguard against elderly destitution, as no comprehensive state welfare systems operated for civilians; those without family often resorted to beggary, slavery, or limited temple-based charity. Roman soldiers, however, benefited from structured discharge provisions after 20-25 years of service, including land grants or cash bonuses under reforms by Augustus around 13 BCE, marking one of the earliest formalized post-service supports, though these applied narrowly to military veterans rather than the general populace. Exposure of infirm elderly, particularly in Sparta via the gerousia council's oversight or infanticide extensions to the aged, underscored pragmatic attitudes prioritizing communal productivity over indefinite care.[38] Medieval European patterns echoed this reliance on family, with elderly parents frequently bequeathing land or dwellings to children—often the youngest or a designated heir—in return for lifelong maintenance, a custom documented in manorial records and legal customs like English copyhold tenures from the 13th century onward. Absent such arrangements, the indigent elderly turned to church-run almshouses or poor relief, which by the 14th century accommodated a fraction of the aged poor amid recurrent famines and plagues; for instance, English parish records from the 15th-16th centuries indicate that only about 5-10% of those over 60 resided in institutional care, the rest dependent on kin or vagrancy. Community norms enforced obligations unevenly, with widows and childless elders most vulnerable to poverty.[39] Low life expectancy further constrained the scope of elderly dependency: global averages at birth approximated 30-35 years in 1800, rising marginally from prehistoric estimates of 25-30 years, primarily due to infant mortality rates exceeding 200 per 1,000 births and infectious diseases claiming many in young adulthood. Among survivors to age 15, however, expectancy extended to 50-60 years in regions like Roman Italy or medieval England, yet economic pressures in subsistence farming precluded idleness, as household units required all members' contributions to avert starvation.[40][41]Industrial and Modern Transformations

The Industrial Revolution, beginning in the late 18th century in Britain and spreading to Europe and North America by the mid-19th century, fundamentally altered labor patterns by shifting populations from agrarian self-sufficiency to urban wage labor in factories and mills. This transition did not initially foster widespread retirement, as older workers often continued in physically demanding roles until incapacity, supported sporadically by family, poor relief, or workhouses; labor force participation rates for men aged 65 and over remained high, exceeding 70% in the United States around 1880.[42] The factory system's emphasis on productivity and mechanization marginalized some elderly workers, yet formal retirement mechanisms were rare, with reliance on informal kin networks or charitable institutions persisting.[43] Emergence of structured pensions marked the onset of modern retirement frameworks in the late 19th century, driven by industrial employers seeking to retain skilled labor and mitigate social unrest. In the United States, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad established one of the earliest private pension plans in 1884, offering up to 35% of prior pay to employees retiring at age 65 after long service, followed by American Express in 1875 as the first corporate plan providing benefits to non-military workers.[44] [45] These initiatives, concentrated in railroads and utilities, were voluntary and covered limited workforces, reflecting employer incentives rather than universal norms; by 1900, fewer than 5% of American workers had access to such plans.[46] In Europe, trade unions began experimenting with old-age benefits in the 1890s, establishing homes and rudimentary retirement funds for members amid growing awareness of industrial pauperism among the aged.[47] State intervention pioneered systematic retirement support, exemplified by Otto von Bismarck's reforms in Germany. Enacted in 1889, the Imperial Insurance Code introduced the world's first compulsory old-age and disability pension for industrial and lower white-collar workers, funded by tripartite contributions from employees, employers, and the government, with benefits commencing at age 70 after 20 years of contributions; this pay-as-you-go system accumulated reserves while aiming to preempt socialist agitation by securing worker loyalty.[48] [49] Eligibility was stringent, excluding many rural and self-employed individuals, and initial payouts were modest, equivalent to about 10-20% of average wages, yet it established a precedent for national systems blending insurance and welfare principles.[50] These developments transformed retirement from an ad hoc cessation of work into a policy-supported life stage, though actual withdrawal from labor remained uncommon before the 20th century due to economic necessity and limited benefit generosity.[42]20th-Century Institutionalization

The institutionalization of retirement in the 20th century marked a shift from ad hoc, limited provisions for the elderly to widespread, structured systems of state-mandated and employer-sponsored pensions, establishing age-based withdrawal from the workforce as a societal norm. Early in the century, public sector pensions expanded significantly; for instance, six U.S. state teacher retirement systems were established by 1920, beginning with North Dakota and California in 1913, while federal civil service pensions covered all government employees by that decade.[51] [52] In Europe, statutory schemes for civil servants and military personnel, precursors to broader coverage, proliferated, with collective bargaining driving private pension growth amid industrial expansion.[53] [54] The Great Depression accelerated federal intervention in the United States, culminating in the Social Security Act of August 14, 1935, which created a national old-age insurance program funded by payroll taxes, initially providing monthly benefits starting in 1940 for retirees aged 65 and older who had contributed sufficiently.[55] This act covered about half the workforce initially, excluding agricultural and domestic laborers, and set the retirement age at 65, influencing norms by tying benefits to cessation of work.[56] Amendments in 1939 introduced survivors' benefits, broadening the program's scope and embedding retirement as a federally supported phase of life, which dramatically reduced elderly poverty rates over subsequent decades through income replacement averaging around 39% of pre-retirement earnings for average earners by the late 20th century.[57] [58] Post-World War II economic growth fueled the rise of private defined-benefit pensions in the U.S. and Europe, with employer-sponsored plans peaking in coverage during the mid-20th century; by the 1950s, union negotiations secured pensions for millions in manufacturing and other sectors, exemplified by widespread adoption following models like the American Express plan from the early 1900s.[59] [60] In Europe, public pension expansions, building on 19th-century foundations, integrated retirement into welfare states, with systems in countries like Germany and the UK mandating contributions and benefits that standardized exit from labor markets around age 65-70.[50] These mechanisms institutionalized retirement by linking economic security to chronological age, often enforcing mandatory retirement policies that cleared positions for younger workers and aligned with actuarial assumptions of declining productivity after 60.[42] By mid-century, retirement transitioned from a privilege for the affluent or public employees to an expectation for the industrial working class, supported by increasing life expectancies and productivity gains that enabled societal resource allocation toward non-working elderly.[61] However, this institutional framework relied on demographic assumptions of stable worker-to-retiree ratios, which later strained systems as fertility declined and longevity rose, though such pressures emerged predominantly after 1970.[62]Global Demographics and Trends

Retirement Ages Across Regions

Statutory retirement ages, which determine eligibility for public pensions, typically range from 60 to 67 years across regions, while effective retirement ages—the average age at which individuals exit the labor force—often differ due to factors like health, economic incentives, and pension generosity. In OECD countries, predominantly in Europe, North America, and parts of Asia-Pacific, the average effective retirement age stood at 64.4 years for men and 63.6 years for women as of recent data.[63] These figures reflect a gap between statutory norms and actual behavior, with effective ages generally lower in southern Europe and higher in East Asia owing to weaker early retirement pathways in the latter.[64] In Europe, statutory ages are converging toward 67 years amid fiscal pressures from aging populations, with countries like Denmark, Italy, and the Netherlands setting 67 as the standard, while France maintains 64 following reforms but faces ongoing debates over sustainability.[65] Effective ages average around 64 for men in OECD European members, lower in nations like Italy (63.5) due to generous disability and early pension options, and higher in Nordic countries like Sweden (66).[66] Projections indicate EU-wide effective ages approaching 67 by 2060, driven by policy reforms linking retirement to life expectancy gains.[65] North America's statutory ages align closely with OECD norms, at 67 for the United States (for those born 1960 or later) and 65 in Canada, though early access with reductions is available from 62 and 60, respectively.[6] Effective ages hover near 65 in the US and 64 in Canada, influenced by private savings vehicles like 401(k)s that incentivize delayed retirement for higher benefits, though health declines prompt earlier exits in manual sectors.[8] Asia exhibits wide variation, with statutory ages often lower for women (e.g., 60 in China versus 65 for men) but effective ages elevated in high-productivity economies like Japan (around 69 for men) and South Korea (69), where cultural norms, limited welfare, and labor shortages sustain longer working lives.[66] In contrast, India and Indonesia have statutory ages of 58-60, yet effective ages exceed 65 in informal sectors due to inadequate pension coverage.[67] OECD projections forecast rises across the region to counter demographic declines, with Asia-Pacific non-OECD averages trailing OECD figures by 1-2 years currently.[63] Latin America features statutory ages of 60-65, such as 65 for men in Brazil and Mexico, but effective ages average in the low 60s, hampered by low pension coverage (under 52% for those over 65) and informal employment forcing continued work.[68] [69] Reforms in countries like Chile have indexed ages to life expectancy, pushing toward 65-67, though enforcement varies amid economic volatility.[70] In Africa, formal statutory ages cluster at 60 (e.g., South Africa, Nigeria), but pension systems cover few workers, with sub-Saharan coverage below 20% for elderly, leading to effective labor participation extending into the 70s in subsistence economies where retirement implies destitution rather than leisure.[71] Data scarcity reflects reliance on family support over state pensions, with urban formal sectors mirroring OECD ages but rural majorities defying them through necessity-driven longevity in work.[72]| Region | Typical Statutory Age (Men/Women) | Average Effective Age (Men, approx.) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Europe (OECD) | 65-67 / 64-66 | 64 | Rising due to reforms; lower in South.[64] |

| North America | 65-67 / same | 65 | Private plans delay exits.[8] |

| Asia-Pacific | 60-67 / 55-65 | 65-69 | High in Japan/Korea; informal extends in South.[66] |

| Latin America | 60-65 / 55-62 | 62-64 | Low coverage forces continuation.[68] |

| Africa | 60 / same | 65+ (informal) | Formal data limited; poverty sustains work.[71] |

Savings and Pension Coverage Statistics

In OECD countries, public pension systems generally provide broad coverage, with contributory schemes encompassing over 90% of formal sector workers in most nations, supplemented by means-tested benefits for others. Private pension coverage, often voluntary or employer-sponsored, averages around 50-60% of the working-age population across these economies, though mandatory systems in countries like Australia and Sweden push rates above 80%. For instance, the 2023 Pensions at a Glance report highlights near-universal first-pillar coverage in nations such as Denmark and the Netherlands, where combined public and occupational schemes mitigate gaps for informal or low-wage earners.[64] Globally, pension coverage remains uneven, with the Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index 2024 documenting private pension participation rates among the working-age population ranging from under 15% in Brazil to over 80% in Chile, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, and Hong Kong SAR. In developing regions, coverage is markedly lower; the World Bank notes that non-contributory social pensions reach only about 35% of those aged 60 and older in areas like Europe and Central Asia, East Asia, and Latin America, leaving substantial portions of the elderly without formal retirement income and dependent on family or state assistance. The International Labour Organization's World Social Protection Report 2024–26 reports a global effective social protection coverage rate of 52.4%, but old-age pension-specific access lags in low-income countries, often below 20% due to informal employment dominance and limited fiscal capacity.[73][74][75] Retirement savings adequacy underscores coverage disparities, with many systems falling short of replacement rates needed for pre-retirement living standards. The OECD Pensions Outlook 2024 indicates that net replacement rates—pensions as a percentage of pre-retirement earnings—average 60-70% in advanced economies but drop below 40% for low earners without supplementary savings, exacerbated by longevity risks. Globally, a persistent savings gap persists; Natixis' 2024 Global Retirement Index estimates cumulative shortfalls in the trillions, driven by insufficient contributions and investment returns in under-covered populations. In the United States, for example, median retirement account balances for households aged 55-64 hovered around $185,000 in 2022 data, far below benchmarks for sustainable retirement given average life expectancies.[76][77]Influences of Longevity, Fertility, and Migration

Increased human longevity, driven by medical and public health advancements, extends the post-retirement lifespan, necessitating greater accumulated savings or delayed retirement to sustain living standards. In the United States, life expectancy at age 65 trails leading nations like Japan and several European countries, yet overall gains pressure defined-benefit pension systems where payouts span more years.[78][79] Globally, average life expectancy is projected to reach 77.3 years by 2050, amplifying fiscal strains on pay-as-you-go public pensions as fewer contributions fund longer benefit periods.[80] Declining fertility rates exacerbate these pressures by shrinking future working-age populations relative to retirees, elevating old-age dependency ratios that burden pension sustainability. Worldwide fertility has fallen below the 2.1 replacement level in many developed economies, with OECD projections showing prolonged rises in ratios due to low births combined with longevity.[81][82] This demographic inversion reduces the contributor-to-beneficiary base, increasing public pension expenditures as a share of GDP and prompting reforms like raised eligibility ages.[83] In regions like Europe and Japan, where fertility hovers around 1.3-1.5 children per woman, the ratio could double by mid-century without offsets, straining economic growth and fiscal resources.[84] Migration influences retirement dynamics by potentially importing younger workers to bolster payroll tax revenues and ease dependency burdens, though outcomes hinge on inflows' scale, age profile, and skill levels. Studies indicate that targeted immigration, particularly of working-age individuals, can slow dependency ratio growth in aging societies by expanding the labor force.[85] However, empirical analyses in Europe reveal that migration, including from outside the EU, often fails to materially improve pension funding adequacy due to factors like initial fiscal costs, family reunification, and variable employment rates.[86] Net positive effects require policies favoring high-employment migrants, as emigration from source countries can conversely inflate pension spending there by depleting contributors.[87] In the EU context, ageing-driven pension costs underscore migration's role, yet integration challenges limit its reliability as a standalone solution.[88]Determinants of Retirement Decisions

Individual Health and Capability Factors

Individual health status serves as a primary determinant of retirement timing, with declines in physical or mental well-being often accelerating exit from the workforce due to diminished capacity to perform job duties. Longitudinal data from the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS), tracking over 20,000 individuals aged 50 and older since 1992, reveal that self-reported poor health or the onset of disabilities substantially elevates retirement probabilities, independent of financial incentives.[89][90] Similarly, econometric models incorporating health metrics demonstrate that adverse health events, such as major illnesses, reduce labor supply by prompting early retirement to manage symptoms or accommodate reduced productivity.[91] Chronic physical conditions exert a particularly strong influence, as they impair functional abilities required for sustained employment. In the European Union, musculoskeletal disorders and cardiovascular diseases account for a disproportionate share of early labor market exits, with chronic disease prevalence among working-age populations rising from 19% in 2010 to 28% in 2017, correlating with heightened retirement rates.[92] Poor health ranks as the leading cited reason for premature retirement across OECD countries, often overriding economic factors, as affected individuals face escalating medical needs and workplace accommodations that prove unsustainable.[92] For manual or physically demanding occupations, conditions like arthritis limit mobility, resulting in hazard ratios for retirement up to 2.5 times higher than for healthier peers, per HRS analyses.[90] Cognitive capabilities similarly shape retirement decisions, with age-related declines fostering mismatches between mental demands and job requirements. NBER research on older workers (aged 50+) finds that cognitive impairment, measured via memory and executive function tests, predicts reduced job retention, especially in non-routine cognitive roles, leading to voluntary or involuntary exits by age 65 in affected cohorts.[93] In the U.S., HRS participants exhibiting cognitive decline show 15-20% lower labor force participation rates compared to those maintaining baseline function, as diminished problem-solving capacity heightens error risks and fatigue.[90] European Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) data corroborate this, linking early cognitive deficits to 10-15% earlier retirement, particularly among less-educated groups lacking adaptive skills.[94] Mental health factors, including depression and anxiety exacerbated by chronic illness, compound these effects by eroding motivation and resilience. HRS findings indicate that individuals with comorbid physical and mental conditions retire up to three years earlier on average, with depression onset doubling the odds of workforce withdrawal versus physical health issues alone.[90] Capability preservation through interventions like vocational rehabilitation can mitigate early retirement; however, untreated declines often dominate, as baseline health trajectories—rooted in genetics, lifestyle, and prior exposures—causally drive capacity erosion over time.[93] Overall, healthier individuals exhibit greater flexibility in delaying retirement, underscoring health's causal primacy over other personal factors in empirical models.[91]Market and Economic Incentives