Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

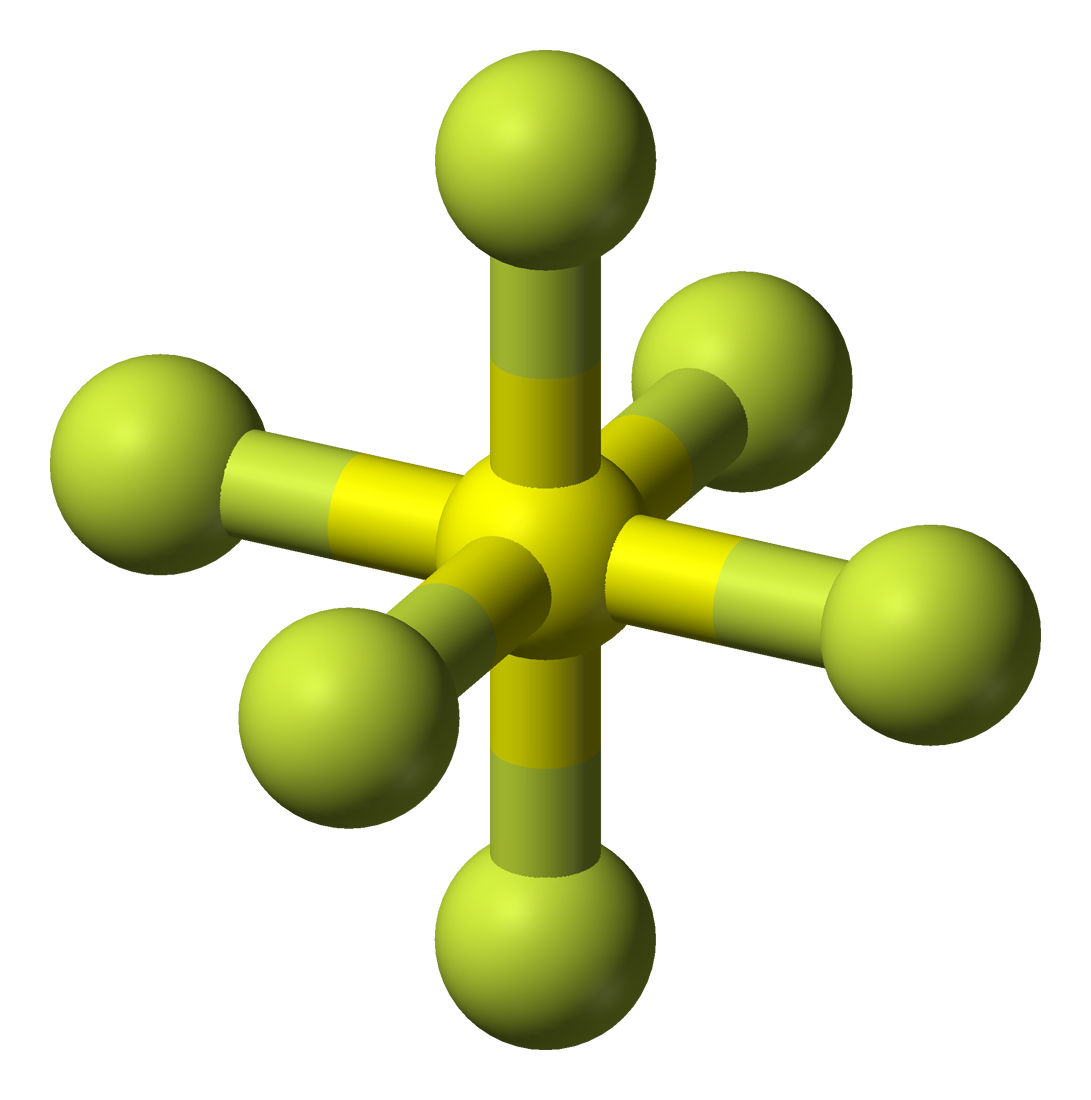

Sulfur hexafluoride

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Sulfur hexafluoride

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Hexafluoro-λ6-sulfane[1] | |||

| Other names

Elagas

Esaflon | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.018.050 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 2752 | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Sulfur+hexafluoride | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1080 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| SF6 | |||

| Molar mass | 146.05 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | odorless[2] | ||

| Density | 6.17 g/L | ||

| Melting point | −50.7 °C (−59.3 °F; 222.5 K)[6] (at or above 2,26 bar air pressure - at normal air pressure it sublimes instead) | ||

| Boiling point | −68.25 °C (−90.85 °F; 204.90 K)[7] (sublimes) | ||

| Critical point (T, P) | 45.51±0.1 °C, 3.749±0.01 MPa[3] | ||

| 0.003% (25 °C)[2] | |||

| Solubility | slightly soluble in water, very soluble in ethanol, hexane, benzene | ||

| Vapor pressure | 2.9 MPa (at 21.1 °C) | ||

| −44.0×10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Thermal conductivity |

| ||

| Viscosity | 15.23 μPa·s[5] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Orthorhombic, oP28 | |||

| Oh | |||

| Orthogonal hexagonal | |||

| Octahedral | |||

| 0 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

0.097 kJ/(mol·K) (constant pressure) | ||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

292 J·mol−1·K−1[8] | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−1209 kJ·mol−1[8] | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| V08DA05 (WHO) | |||

| License data | |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling:[9] | |||

| |||

| Warning | |||

| H280 | |||

| P403 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 1000 ppm (6000 mg/m3)[2] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 1000 ppm (6000 mg/m3)[2] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[2] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related sulfur fluorides

|

Disulfur decafluoride | ||

Related compounds

|

Selenium hexafluoride Sulfuryl fluoride | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Sulfur hexafluoride or sulphur hexafluoride (British spelling) is an inorganic compound with the formula SF6. It is a colorless, odorless, non-flammable, and non-toxic gas. SF

6 has an octahedral geometry, consisting of six fluorine atoms attached to a central sulfur atom. It is a hypervalent molecule.[citation needed]

Typical for a nonpolar gas, SF

6 is poorly soluble in water but quite soluble in nonpolar organic solvents. It has a density of 6.12 g/L at sea level conditions, considerably higher than the density of air (1.225 g/L). It is generally stored and transported as a liquefied compressed gas.[10]

SF

6 has 23,500 times greater global warming potential (GWP) than CO2 as a greenhouse gas (over a 100-year time-frame) but exists in relatively minor concentrations in the atmosphere. Its concentration in Earth's troposphere reached 12.06 parts per trillion (ppt) in February 2025, rising at 0.4 ppt/year.[11] The increase since 1980 is driven in large part by the expanding electric power sector, including fugitive emissions from banks of SF

6 gas contained in its medium- and high-voltage switchgear. Uses in magnesium, aluminium, and electronics manufacturing also hastened atmospheric growth.[12]

Synthesis and reactions

[edit]Sulfur hexafluoride on Earth exists primarily as a synthetic industrial gas, but has also been found to occur naturally.[13]

SF

6 can be prepared from the elements through exposure of S

8 to F

2. This was the method used by the discoverers Henri Moissan and Paul Lebeau in 1901. Some other sulfur fluorides are cogenerated, but these are removed by heating the mixture to disproportionate any S

2F

10 (which is highly toxic) and then scrubbing the product with NaOH to destroy remaining SF

4.[clarification needed]

Alternatively, using bromine, sulfur hexafluoride can be synthesized from SF4 and CoF3 at lower temperatures (e.g. 100 °C), as follows:[14]

There are few chemical reactions for SF

6. A main contribution to the inertness of SF6 is the steric hindrance of the sulfur atom, whereas its heavier group 16 counterparts, such as SeF6 are more reactive than SF6 as a result of less steric hindrance.[15] It does not react with molten sodium below its boiling point,[16] but reacts exothermically with lithium. However, alkali metals react with SF6 in liquid ammonia to form the corresponding sulfides and fluorides[17]:

As a result of its inertness, SF

6 has an atmospheric lifetime of around 3200 years, and no significant environmental sinks other than the ocean.[18]

Applications

[edit]By 2000, the electrical power industry is estimated to use about 80% of the sulfur hexafluoride produced, mostly as a gaseous dielectric medium.[19] Other main uses as of 2015 included a silicon etchant for semiconductor manufacturing, and an inert gas for the casting of magnesium.[20]

Dielectric medium

[edit]SF

6 is used in the electrical industry as a gaseous dielectric medium for high-voltage sulfur hexafluoride circuit breakers, switchgear, and other electrical equipment, often replacing oil-filled circuit breakers (OCBs) that can contain harmful polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). SF

6 gas under pressure is used as an insulator in gas insulated switchgear (GIS) because it has a much higher dielectric strength than air or dry nitrogen. The high dielectric strength is a result of the gas's high electronegativity and density. This property makes it possible to significantly reduce the size of electrical gear. This makes GIS more suitable for certain purposes such as indoor placement, as opposed to air-insulated electrical gear, which takes up considerably more room.

Gas-insulated electrical gear is also more resistant to the effects of pollution and climate, as well as being more reliable in long-term operation because of its controlled operating environment. Exposure to an arc chemically breaks down SF

6 though most of the decomposition products tend to quickly re-form SF

6, a process termed "self-healing".[21] Arcing or corona can produce disulfur decafluoride (S

2F

10), a highly toxic gas, with toxicity similar to phosgene. S

2F

10 was considered a potential chemical warfare agent in World War II because it does not produce lacrimation or skin irritation, thus providing little warning of exposure.

SF

6 is also commonly encountered as a high voltage dielectric in the high voltage supplies of particle accelerators, such as Van de Graaff generators and Pelletrons and high voltage transmission electron microscopes.

Alternatives to SF

6 as a dielectric gas include several fluoroketones.[22][23] Compact GIS technology that combines vacuum switching with clean air insulation has been introduced for a subset of applications up to 420 kV.[24]

Medical use

[edit]SF

6 is used to provide a tamponade or plug of a retinal hole in retinal detachment repair operations[25] in the form of a gas bubble. It is inert in the vitreous chamber.[26] The bubble initially doubles its volume in 36 hours due to oxygen and nitrogen entering it, before being absorbed in the blood in 10–14 days.[27]

SF

6 is used as a contrast agent for ultrasound imaging. Sulfur hexafluoride microbubbles are administered in solution through injection into a peripheral vein. These microbubbles enhance the visibility of blood vessels to ultrasound. This application has been used to examine the vascularity of tumours.[28] It remains visible in the blood for 3 to 8 minutes, and is exhaled by the lungs.[29]

Tracer compound

[edit]Sulfur hexafluoride was the tracer gas used in the first roadway air dispersion model calibration; this research program was sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and conducted in Sunnyvale, California on U.S. Highway 101.[30] Gaseous SF

6 is used as a tracer gas in short-term experiments of ventilation efficiency in buildings and indoor enclosures, and for determining infiltration rates. Two major factors recommend its use: its concentration can be measured with satisfactory accuracy at very low concentrations, and the Earth's atmosphere has a negligible concentration of SF

6.

Sulfur hexafluoride was used as a non-toxic test gas in an experiment at St John's Wood tube station in London, United Kingdom on 25 March 2007.[31] The gas was released throughout the station, and monitored as it drifted around. The purpose of the experiment, which had been announced earlier in March by the Secretary of State for Transport Douglas Alexander, was to investigate how toxic gas might spread throughout London Underground stations and buildings during a terrorist attack.

Sulfur hexafluoride is also routinely used as a tracer gas in laboratory fume hood containment testing. The gas is used in the final stage of ASHRAE 110 fume hood qualification. A plume of gas is generated inside of the fume hood and a battery of tests are performed while a gas analyzer arranged outside of the hood samples for SF6 to verify the containment properties of the fume hood.

It has been used successfully as a transient tracer in oceanography to study diapycnal mixing and air-sea gas exchange.[32] The concentration of sulfur hexafluoride in seawater (typically on the order of femtomoles per kilogram[33]) has been classified by the international oceanography community as a "level one" measurement, denoting the highest priority data for observing ocean changes.[34]

Other uses

[edit]- The magnesium industry uses SF

6 as an inert "cover gas" to prevent oxidation during casting,[35] and other processes including smelting.[36] Once the largest user, consumption has declined greatly with capture and recycling.[12] - Insulated glazing windows have used it as a filler to improve their thermal and acoustic insulation performance.[37][38]

- SF

6 plasma is used in the semiconductor industry as an etchant in processes such as deep reactive-ion etching. A small fraction of the SF

6 breaks down in the plasma into sulfur and fluorine, with the fluorine ions performing a chemical reaction with silicon.[39] - Tires filled with it take longer to deflate from diffusion through rubber due to the larger molecule size.[37]

- Nike likewise used it to obtain a patent and to fill the cushion bags in all of their "Air"-branded shoes from 1992 to 2006.[40] 277 tons was used during the peak in 1997.[37]

- The United States Navy's Mark 50 torpedo closed Rankine-cycle propulsion system is powered by sulfur hexafluoride in an exothermic reaction with solid lithium.[41]

- Waveguides in high-power microwave systems are pressurized with it. The gas electrically insulates the waveguide, preventing internal arcing.

- Electrostatic loudspeakers have used it because of its high dielectric strength and high molecular weight.[42]

- Disulfur decafluoride, a chemical weapon, is produced with it as a feedstock.

- For entertainment purposes, when breathed, SF

6 causes the voice to become significantly deeper, due to its density being so much higher than air. This phenomenon is related to the more well-known effect of breathing low-density helium, which causes someone's voice to become much higher. Both of these effects should only be attempted with caution as these gases displace oxygen that the lungs are attempting to extract from the air. Sulfur hexafluoride is also mildly anesthetic.[43][44] - For science demonstrations / magic as "invisible water" since a light foil boat can be floated in a tank, as will an air-filled balloon.

- It is used for benchmark and calibration measurements in Associative and Dissociative Electron Attachment (DEA) experiments[45][46]

Greenhouse gas

[edit]-

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) measured by the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) in the lower atmosphere (troposphere) at stations around the world. Abundances are given as pollution free monthly mean mole fractions in parts-per-trillion.

-

Abundance and growth rate of SF

6 in Earth's troposphere (1978-2018).[12] -

Atmospheric concentration of SF6 vs. similar man-made gases (right graph). Note the log scale.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, SF

6 is the most potent greenhouse gas. Its global warming potential of 23,900 times that of CO

2 when compared over a 100-year period.[47] Sulfur hexafluoride is inert in the troposphere and stratosphere and is extremely long-lived, with an estimated atmospheric lifetime of 800–3,200 years.[48]

Measurements of SF6 show that its global average mixing ratio has increased from a steady base of about 54 parts per quadrillion[13] prior to industrialization, to over 12 parts per trillion (ppt) as of February 2025, and is increasing by about 0.4 ppt (3.5%) per year.[11][49] Average global SF6 concentrations increased by about 7% per year during the 1980s and 1990s, mostly as the result of its use in magnesium production, and by electrical utilities and electronics manufacturers. Given the small amounts of SF6 released compared to carbon dioxide, its overall individual contribution to global warming is estimated to be less than 0.2%,[50] however the collective contribution of it and similar man-made halogenated gases has reached about 10% as of 2020.[51] Alternatives are being tested.[52][53]

In Europe, SF

6 falls under the F-Gas directive which bans or controls its use for several applications.[54] Since 1 January 2006, SF

6 is banned as a tracer gas and in all applications except high-voltage switchgear.[55] It was reported in 2013 that a three-year effort by the United States Department of Energy to identify and fix leaks at its laboratories in the United States such as the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, where the gas is used as a high voltage insulator, had been productive, cutting annual leaks by 1,030 kilograms (2,280 pounds). This was done by comparing purchases with inventory, assuming the difference was leaked, then locating and fixing the leaks.[56]

Physiological effects and precautions

[edit]Sulfur hexafluoride is a nontoxic gas, but by displacing oxygen in the lungs, it also carries the risk of asphyxia if too much is inhaled.[57] Since it is more dense than air, a substantial quantity of gas, when released, will settle in low-lying areas and present a significant risk of asphyxiation if the area is entered. That is particularly relevant to its use as an insulator in electrical equipment since workers may be in trenches or pits below equipment containing SF

6.[58]

As with all gases, the density of SF

6 affects the resonance frequencies of the vocal tract, thus changing drastically the vocal sound qualities, or timbre, of those who inhale it. It does not affect the vibrations of the vocal folds. The density of sulfur hexafluoride is relatively high at room temperature and pressure due to the gas's large molar mass. Unlike helium, which has a molar mass of about 4 g/mol and pitches the voice up, SF

6 has a molar mass of about 146 g/mol, and the speed of sound through the gas is about 134 m/s at room temperature, pitching the voice down. For comparison, the molar mass of air, which is about 80% nitrogen and 20% oxygen, is approximately 30 g/mol which leads to a speed of sound of 343 m/s.[59]

Sulfur hexafluoride has an anesthetic potency slightly lower than nitrous oxide;[60] it is classified as a mild anesthetic.[61]

See also

[edit]- Selenium hexafluoride

- Tellurium hexafluoride

- Uranium hexafluoride

- Hypervalent molecule

- Halocarbon—another group of major greenhouse gases

- Trifluoromethylsulfur pentafluoride, a similar gas

References

[edit]- ^ "Sulfur Hexafluoride - PubChem Public Chemical Database". PubChem. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0576". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Horstmann S, Fischer K, Gmehling J (2002). "Measurement and calculation of critical points for binary and ternary mixtures". AIChE Journal. 48 (10): 2350–2356. Bibcode:2002AIChE..48.2350H. doi:10.1002/aic.690481024. ISSN 0001-1541.

- ^ Assael MJ, Koini IA, Antoniadis KD, Huber ML, Abdulagatov IM, Perkins RA (2012). "Reference Correlation of the Thermal Conductivity of Sulfur Hexafluoride from the Triple Point to 1000 K and up to 150 MPa". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 41 (2): 023104–023104–9. Bibcode:2012JPCRD..41b3104A. doi:10.1063/1.4708620. ISSN 0047-2689. S2CID 18916699.

- ^ Assael MJ, Kalyva AE, Monogenidou SA, Huber ML, Perkins RA, Friend DG, May EF (2018). "Reference Values and Reference Correlations for the Thermal Conductivity and Viscosity of Fluids". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 47 (2): 021501. Bibcode:2018JPCRD..47b1501A. doi:10.1063/1.5036625. ISSN 0047-2689. PMC 6463310. PMID 30996494.

- ^ https://encyclopedia.airliquide.com/sulfur-hexafluoride#properties

- ^ https://encyclopedia.airliquide.com/sulfur-hexafluoride#properties

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ GHS: Record of Schwefelhexafluorid in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, accessed on 2021-12-13.

- ^ Niemeyer L (1998), Christophorou LG, Olthoff JK (eds.), "SF6 Recycling in Electric Power Equipment", Gaseous Dielectrics VIII, Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 431–442, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4899-7_58, ISBN 978-1-4615-4899-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ a b "Trends in Atmospheric Sulpher Hexaflouride". US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

- ^ a b c Simmonds, P. G., Rigby, M., Manning, A. J., Park, S., Stanley, K. M., McCulloch, A., Henne, S., Graziosi, F., Maione, M., and 19 others (2020) "The increasing atmospheric burden of the greenhouse gas sulfur hexafluoride (SF6)". Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20: 7271–7290. doi:10.5194/acp-20-7271-2020.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b Busenberg, E. and Plummer, N. (2000). "Dating young groundwater with sulfur hexafluoride: Natural and anthropogenic sources of sulfur hexafluoride". Water Resources Research. 36 (10). American Geophysical Union: 3011–3030. Bibcode:2000WRR....36.3011B. doi:10.1029/2000WR900151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Winter RW, Pugh JR, Cook PW (January 9–14, 2011). SF5Cl, SF4 and SF6: Their Bromine−facilitated Production & a New Preparation Method for SF5Br. 20th Winter Fluorine Conference.

- ^ Duward Shriver, Peter Atkins (2010). Inorganic Chemistry. W. H. Freeman. p. 409. ISBN 978-1-4292-5255-3.

- ^ Raj G (2010). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry: Volume II (12th ed.). GOEL Publishing House. p. 160. Extract of page 160

- ^ Holger Lars Deubner, Florian Kraus: The Decomposition Products of Sulfur Hexafluoride (SF6) with Metals Dissolved in Liquid Ammonia. In: Inorganics. Band 5, Nr. 4, 13. Oktober 2017, S. 68, doi:10.3390/inorganics5040068 (mdpi.com).

- ^ Stöven T, Tanhua T, Hoppema M, Bullister JL (2015-09-18). "Perspectives of transient tracer applications and limiting cases". Ocean Science. 11 (5): 699–718. Bibcode:2015OcSci..11..699S. doi:10.5194/os-11-699-2015. ISSN 1812-0792.

- ^ Constantine T. Dervos, Panayota Vassilou (2000). "Sulfur Hexafluoride: Global Environmental Effects and Toxic Byproduct Formation". Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 50 (1). Taylor and Francis: 137–141. Bibcode:2000JAWMA..50..137D. doi:10.1080/10473289.2000.10463996. PMID 10680375. S2CID 8533705.

- ^ Deborah Ottinger, Mollie Averyt, Deborah Harris (2015). "US consumption and supplies of sulphur hexafluoride reported under the greenhouse gas reporting program". Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences. 12 (sup1). Taylor and Francis: 5–16. doi:10.1080/1943815X.2015.1092452.

- ^ Jakob F, Perjanik N, Sulfur Hexafluoride, A Unique Dielectric (PDF), Analytical ChemTech International, Inc., archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2017-10-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Kieffel Y, Biquez F (1 June 2015). "SF6 alternative development for high voltage switchgears". 2015 IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference (EIC). pp. 379–383. doi:10.1109/ICACACT.2014.7223577. ISBN 978-1-4799-7352-1. S2CID 15911515 – via IEEE Xplore.

- ^ "Sustainable switchgear technology for a CO2 neutral future". Siemens Energy. 2020-08-31. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ Daniel A. Brinton, C. P. Wilkinson (2009). Retinal detachment: principles and practice. Oxford University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-19-971621-0.

- ^ Gholam A. Peyman, M.D., Stephen A. Meffert, M.D., Mandi D. Conway (2007). Vitreoretinal Surgical Techniques. Informa Healthcare. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-84184-626-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hilton GF, Das T, Majji AB, Jalali S (1996). "Pneumatic retinopexy: Principles and practice". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 44 (3): 131–143. PMID 9018990.

- ^ Lassau N, Chami L, Benatsou B, Peronneau P, Roche A (December 2007). "Dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (DCE-US) with quantification of tumor perfusion: a new diagnostic tool to evaluate the early effects of antiangiogenic treatment". Eur Radiol. 17 (Suppl. 6): F89–F98. doi:10.1007/s10406-007-0233-6. PMID 18376462. S2CID 42111848.

- ^ "SonoVue, INN-sulphur hexafluoride - Annex I - Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ^ C Michael Hogan (September 10, 2011). "Air pollution line source". Encyclopedia of Earth. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "'Poison gas' test on Underground". BBC News. 25 March 2007. Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Fine RA (2010-12-15). "Observations of CFCs and SF6 as Ocean Tracers". Annual Review of Marine Science. 3 (1): 173–195. doi:10.1146/annurev.marine.010908.163933. ISSN 1941-1405. PMID 21329203.

- ^ J.L. Bullister and T. Tanhua, 2010. "Sampling and measurement of chlorofluorocarbons and sulfur hexafluoride in seawater". IOCCP Report No. 14. http://www.go-ship.org/HydroMan.html

- ^ "GO-SHIP Data Requirements". www.go-ship.org. Retrieved 2025-01-30.

- ^ Scott C. Bartos (February 2002). "Update on EPA's manesium industry partnership for climate protection" (PDF). US Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Ayres J (2000). "Canadian Perspective on SF6 Management from Magnesium Industry" (PDF). Environment Canada.

- ^ a b c J. Harnisch and W. Schwarz (2003-02-04). "Final report on the costs and the impact on emissions of potential regulatory framework for reducing emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulphur hexafluoride" (PDF). Ecofys GmbH.

- ^ Hopkins C (2007). Sound insulation - Google Books. Elsevier / Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 504–506. ISBN 978-0-7506-6526-1.

- ^ Y. Tzeng, T.H. Lin (September 1987). "Dry Etching of Silicon Materials in SF

6 Based Plasmas" (PDF). Journal of the Electrochemical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013. - ^ Stanley Holmes (September 24, 2006). "Nike Goes For The Green". Bloomberg Business Week Magazine. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Hughes, T.G., Smith, R.B., Kiely, D.H. (1983). "Stored Chemical Energy Propulsion System for Underwater Applications". Journal of Energy. 7 (2): 128–133. Bibcode:1983JEner...7..128H. doi:10.2514/3.62644.

- ^ Dick Olsher (October 26, 2009). "Advances in loudspeaker technology - A 50 year prospective". The Absolute Sound. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Edmond I Eger MD, et al. (September 10, 1968). "Anesthetic Potencies of Sulfur Hexafluoride, Carbon Tetrafluoride, Chloroform and Ethrane in Dogs: Correlation with the Hydrate and Lipid Theories of Anesthetic Action". Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 30 (2). Anesthesiology - The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc: 127–134.

- ^ WTOL (2015-01-27). Sound Like Darth Vader with Sulfur Hexafluoride. YouTube. Imagination Station.

- ^ Braun M, Marienfeld S, Ruf MW, Hotop H (2009-05-26). "High-resolution electron attachment to the molecules CCl4and SF6over extended energy ranges with the (EX)LPA method". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 42 (12) 125202. Bibcode:2009JPhB...42l5202B. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/42/12/125202. ISSN 0953-4075. S2CID 122242919.

- ^ Fenzlaff M, Gerhard R, Illenberger E (1988-01-01). "Associative and dissociative electron attachment by SF6 and SF5Cl". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 88 (1): 149–155. Bibcode:1988JChPh..88..149F. doi:10.1063/1.454646. ISSN 0021-9606.

- ^ "2.10.2 Direct Global Warming Potentials". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ A. R. Ravishankara, S. Solomon, A. A. Turnipseed, R. F. Warren, Solomon, Turnipseed, Warren (8 January 1993). "Atmospheric Lifetimes of Long-Lived Halogenated Species". Science. 259 (5092): 194–199. Bibcode:1993Sci...259..194R. doi:10.1126/science.259.5092.194. PMID 17790983. S2CID 574937. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) data from hourly in situ samples analyzed on a gas chromatograph located at Cape Matatulu (SMO)". aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov (FTP). July 7, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020. (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- ^ "SF6 Sulfur Hexafluoride". PowerPlantCCS Blog. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Butler J. and Montzka S. (2020). "The NOAA Annual Greenhouse Gas Index (AGGI)". NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory/Earth System Research Laboratories.

- ^ "g3, the SF6-free solution in practice | Think Grid". think-grid.org. 18 February 2019. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ Mohamed Rabie, Christian M. Franck (2018). "Assessment of Eco-friendly Gases for Electrical Insulation to Replace the Most Potent Industrial Greenhouse Gas SF6". Environmental Science & Technology. 52 (2). American Chemical Society: 369–380. Bibcode:2018EnST...52..369R. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b03465. hdl:20.500.11850/238519. PMID 29236468.

- ^ David Nikel (2020-01-15). "Sulfur hexafluoride: The truths and myths of this greenhouse gas". phys.org. Retrieved 2020-10-18.

- ^ "Climate: MEPs give F-gas bill a 'green boost'". www.euractiv.com. EurActiv.com. 13 October 2005. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Michael Wines (June 13, 2013). "Department of Energy's Crusade Against Leaks of a Potent Greenhouse Gas Yields Results". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Sulfur Hexafluoride". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Guide to the safe use of SF6 in gas". UNIPEDE/EURELECTRIC. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- ^ "Physics in Speech". University of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Adriani J (1962). The Chemistry and Physics of Anesthesia (2nd ed.). Illinois: Thomas Books. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-398-00011-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Weaver RH, Virtue RW (1 November 1952). "The mild anesthetic properties of sulfur hexafluoride". Anesthesiology. 13 (6): 605–607. doi:10.1097/00000542-195211000-00006. PMID 12986223. S2CID 32403288.

Further reading

[edit]- "Sulfur hexafluoride". Air Liquide Gas Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Christophorou, Loucas G., Isidor Sauers, eds. (1991). Gaseous Dielectrics VI. Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-43894-3.

- Holleman AF, Wiberg E (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- Khalifa M (1990). High-Voltage Engineering: Theory and Practice. New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-8128-6. OCLC 20595838.

- Maller VN, Naidu MS (1981). Advantages in High Voltage Insulation and Arc Interruption in SF6 and Vacuum. Oxford; New York: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0-08-024726-7. OCLC 7866855.

- SF6 Reduction Partnership for Electric Power Systems

- Matt McGrath (September 13, 2019). "Climate change: Electrical industry's 'dirty secret' boosts warming". BBC News. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

External links

[edit]Sulfur hexafluoride

View on GrokipediaChemical Properties

Molecular Structure and Bonding

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆) features a central sulfur(VI) atom bonded to six fluorine atoms, forming a hypervalent molecule with the sulfur atom surrounded by twelve valence electrons in its Lewis structure.[9] The molecular geometry is octahedral (AX₆ in VSEPR notation), with all S-F bonds equivalent and bond angles of 90° between adjacent bonds and 180° between opposite bonds, arising from the symmetry of the six coordinating ligands. This regular octahedron is confirmed experimentally, with gas-phase S-F bond lengths measured at 1.561 Å. The bonding in SF₆ is primarily covalent, characterized by high electronegativity of fluorine leading to significant charge transfer from sulfur to fluorine atoms, resulting in partial ionic character.[10] Traditional valence bond theory invoked sp³d² hybridization on sulfur, incorporating empty 3d orbitals to expand the octet and accommodate six bonding pairs, a model that rationalizes the octahedral shape but has been challenged by computational evidence.[11] Modern quantum chemical calculations, including molecular orbital theory, indicate minimal participation of sulfur 3d orbitals in bonding, as their energies are too high for effective overlap with fluorine orbitals; instead, the hypervalency is explained through recoupled pair bonding or 3-center 4-electron (3c-4e) interactions, where electron pairs from sulfur are delocalized over multiple centers without violating the octet rule in resonance structures.[12][11] This shift reflects empirical validation from ab initio methods, which prioritize s- and p-orbital contributions and polar covalent bonding over d-orbital expansion.[12] The equivalence of all S-F bonds, despite the hypervalent nature, stems from rapid pseudorotation or fluxional behavior in related species, but in SF₆, the symmetric structure precludes distinct axial-equatorial differentiation observed in lower-coordinate sulfur fluorides like SF₄.[13] Experimental bond dissociation energies support a stepwise weakening from SF₆ to lower fluorides, consistent with increasing ionic character and reduced overlap in hypervalent frameworks.[10]Physical Characteristics

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) is a colorless, odorless, and non-flammable gas at standard temperature and pressure, with a molecular weight of 146.06 g/mol.[14] Its vapor density is approximately 5.11 relative to air, resulting in a absolute density of 6.16 g/L at 0 °C and 1 atm pressure.[15] The gas exhibits low solubility in water, with a value of 5.4 cm³/kg at 25 °C and 101.325 kPa partial pressure.[1] Under atmospheric pressure, SF6 sublimes at −63.9 °C rather than melting, though its triple point occurs at −50.8 °C and 224 kPa, above which it can exist as a liquid.[16] The critical temperature is 45.54 °C, and the critical pressure is 3.76 MPa.[17] These phase properties contribute to its utility in high-pressure applications, where it maintains gaseous behavior over a wide temperature range at ambient conditions. Key thermophysical properties include a specific heat capacity at constant pressure (cp) of approximately 0.642 kJ/kg·K at 25 °C and low pressure, and a thermal conductivity of 0.015 W/m·K under similar conditions.[18] SF6 is non-polar and symmetric, leading to minimal intermolecular forces and thus low viscosity, with values around 15 μPa·s at 25 °C.[19]| Property | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Density (gas) | 6.16 g/L | 0 °C, 1 atm |

| Melting/sublimation point | −50.8 °C / −63.9 °C | 224 kPa / 1 atm |

| Critical temperature | 45.54 °C | - |

| Water solubility | 5.4 cm³/kg | 25 °C, 101.325 kPa |

Chemical Stability and Reactivity

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆) exhibits exceptional chemical stability under standard conditions, attributed to the strength of its six S–F bonds and its symmetric octahedral geometry, rendering it inert toward hydrolysis, oxidation, and most common reagents. It remains stable at temperatures up to 500 °C in the absence of catalysts or reactive metals, with no significant decomposition or polymerization observed during normal storage and handling.[20][21] Despite this inertness, SF₆ can undergo decomposition under high-energy conditions such as electrical arcs or discharges in gas-insulated equipment, producing toxic byproducts including sulfur oxyfluorides (e.g., SOF₂, SO₂F₂) and hydrogen fluoride (HF) when moisture is present. These reactions occur via bond cleavage initiated by electron impact or thermal stress, with decomposition efficiency increasing with discharge energy; for instance, partial discharges can generate trace levels of lower fluorides like SF₅ or SF₄ radicals.[4][22] Reactivity with metals is limited but notable under specific circumstances: SF₆ shows minimal interaction with most structural metals at ambient temperatures but can react slowly with alkali metals like sodium above 200 °C, forming metal fluorides and sulfur compounds, or with transition metals under plasma conditions. Specialized reducing agents, such as certain aluminum(I) compounds or metal phosphides, enable rare room-temperature reductions, cleaving S–F bonds to yield aluminum or metal sulfides and fluorides, though such reactions require non-standard laboratory setups and do not reflect typical environmental or industrial behavior.[20][23][24] Thermal plasma or electrochemical methods can achieve near-complete decomposition (up to 99% with H₂ addition), but these demand elevated temperatures exceeding 1000 °C or specialized electrodes, underscoring SF₆'s resistance to casual breakdown.[25][26]History and Production

Discovery and Early Synthesis

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) was first synthesized in 1901 by French chemists Henri Moissan and Paul Lebeau through the direct reaction of elemental sulfur with fluorine gas.[27][28] Moissan, who had isolated fluorine in 1886 and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for that achievement, collaborated with Lebeau at the Sorbonne in Paris to explore compounds of the newly accessible halogen.[29] The synthesis involved combusting sulfur in a fluorine atmosphere, yielding the colorless, odorless gas alongside minor sulfur fluorides, which were separated by distillation.[27] This direct fluorination method highlighted SF6's exceptional chemical stability, as the compound resisted further reaction even under forcing conditions, a property attributed to the strong sulfur-fluorine bonds and octahedral geometry.[30] Early characterizations confirmed its inertness, non-toxicity, and high density (approximately 6.16 g/L at standard conditions), distinguishing it from more reactive sulfur halides like SF4 or SF2.[31] However, the process's reliance on highly reactive fluorine limited scalability and posed significant safety risks, confining initial production to laboratory quantities.[30] Subsequent early efforts refined purification but retained the elemental fluorine route until mid-20th-century alternatives emerged, such as pyrolysis of sulfur pentafluoride chloride (SF5Cl) to avoid direct handling of F2.[30] These developments built on Moissan and Lebeau's foundational work, which established SF6 as a benchmark for fluorocarbon stability without immediate practical applications.[32]Industrial Scale Production

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆) is manufactured on an industrial scale primarily through the direct fluorination of elemental sulfur with fluorine gas, following the exothermic reaction S + 3F₂ → SF₆. Elemental sulfur is vaporized at elevated temperatures, typically around 100–200°C, and reacted with high-purity fluorine gas, which is produced via the electrolysis of a molten mixture of potassium fluoride and hydrogen fluoride (KF·2HF). This process occurs in corrosion-resistant reactors, such as those lined with nickel or Monel alloy, to withstand the aggressive nature of fluorine and ensure safety and efficiency. The reaction yields crude SF₆, which is then purified through fractional distillation or adsorption to remove byproducts like sulfur tetrafluoride (SF₄) and lower fluorides, achieving purities often exceeding 99.99% for electrical-grade applications.[33][34][35] Alternative methods include the fluorination of sulfur tetrafluoride (SF₄ + F₂ → SF₆), sometimes facilitated by oxidative agents like cobalt(III) fluoride (CoF₃) in a regenerable solid-phase process, where CoF₃ acts as an oxygen source and is recycled using fluorine. These approaches are used to improve yield or handle impurities but are less common than direct synthesis due to the availability of elemental sulfur and the simplicity of the primary reaction. Production facilities emphasize closed-loop systems to minimize fluorine emissions and recycle unreacted gases, reflecting the high cost and hazard of fluorine handling.[35][36] Key global producers include Solvay, Resonac Holdings (formerly Showa Denko), Honeywell International, and Matheson Tri-Gas, with manufacturing concentrated in regions with access to fluorine production infrastructure, such as Europe, North America, and Asia. Annual worldwide output supports demand primarily from the electrical industry, with market analyses indicating steady growth driven by high-voltage equipment needs, though exact volumes vary by year and are not publicly detailed by all firms due to commercial sensitivity.[37][38][39]Purity Standards and Supply Chain

Technical grade sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆) for electrical applications must meet stringent purity requirements outlined in IEC 60376:2018, which specifies a minimum SF₆ content exceeding 99.7% by volume, with strict limits on impurities such as moisture (<15 mg/kg), air (<0.05% by volume), and hydrolyzable fluorides (<0.2 mg/kg) to ensure dielectric integrity and prevent corrosion or arc decomposition in high-voltage equipment.[40][41] For semiconductor and electronic applications, ultra-high purity grades reach 99.999% SF₆, minimizing contaminants that could affect etching processes or plasma stability.[42] Reclaimed SF₆, governed by IEC 60480, requires purification to at least 95% purity for reuse, involving filtration to remove particulates, adsorption of decomposition products like SO₂ and HF, and liquefaction for impurity separation.[43] SF₆ production primarily occurs through direct fluorination of sulfur or sulfur compounds with fluorine gas, often via oxidative processes such as burning sulfur in a fluorine stream or reacting sulfur tetrafluoride with cobalt trifluoride and fluorine, yielding high-purity gas after distillation and drying.[35] Major global producers include Solvay (now Syensqo), Air Liquide, Linde plc, Showa Denko K.K., and Honeywell International, who control much of the supply through integrated fluorochemical facilities, with annual production estimated at 7,000–8,000 metric tons as of recent market analyses.[18][38][39] The supply chain begins with sourcing elemental sulfur (from petroleum refining) and fluorine (derived from hydrofluoric acid electrolysis), progressing to specialized synthesis plants in regions like Europe, North America, and Asia-Pacific, where China dominates manufacturing capacity.[39] Distribution involves high-pressure cylinders or tonner containers shipped to switchgear manufacturers (e.g., ABB, Siemens) and utilities, with growing emphasis on closed-loop systems for gas recovery during equipment maintenance to mitigate emissions, as facilitated by suppliers like DILO and Concorde Specialty Gases.[44][45] Supply disruptions, such as those from fluorspar shortages or regulatory pressures on fluorochemicals, have occasionally tightened availability, prompting investments in recycling infrastructure that recovers up to 99% of used SF₆.[46]Applications

Electrical Insulation and Dielectrics

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) is widely employed as a dielectric gas in high-voltage electrical equipment, particularly in circuit breakers and gas-insulated switchgear (GIS), owing to its exceptional insulating capabilities and arc-quenching efficiency.[5] Its electronegative nature enables effective electron capture, which enhances breakdown resistance under high electric fields, making it suitable for voltages exceeding 72.5 kV.[47] The gas's dielectric strength is approximately 2.5 times greater than that of air at equivalent pressure and gap distance, permitting more compact equipment designs compared to air- or oil-insulated alternatives.[33] In SF6 circuit breakers, the gas provides both insulation between live parts and rapid arc extinction during current interruption, as the high thermal conductivity and low speed of sound (about one-third that of air) facilitate convective cooling and prevent re-ignition.[5][33] Typical operating pressures range from 0.4 to 0.5 MPa, where breakdown voltage peaks around 0.2 MPa for uniform fields, though practical systems optimize for non-uniform geometries to achieve ratings up to 800 kV.[33] This dual functionality reduces the physical size of interrupters, with SF6-based breakers handling short-circuit currents up to 80 kA.[47] GIS systems encapsulate conductors, busbars, and switches in SF6-filled enclosures, leveraging the gas's high insulation to minimize footprint—often 10-20% of air-insulated substation area—while improving reliability in contaminated or seismic-prone environments.[48] Over 90% of SF6 consumption in the electrical sector occurs in GIS and related high-voltage applications, with installations like the Itaipú hydroelectric plant featuring more than 100 tons of the gas in compact switchyards.[48][18] The gas's chemical inertness ensures long-term stability, though minor decomposition products from arcing necessitate periodic monitoring and gas reclamation to maintain dielectric performance.[5]Medical and Tracer Uses

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) serves as the gaseous core in stabilized microbubble formulations for ultrasound contrast enhancement, notably in products like Lumason (sulfur hexafluoride lipid-type A microspheres) and SonoVue, where it improves visualization of cardiac structures during echocardiography.[49][50] These agents opacify the left ventricular chamber in adults with suboptimal echocardiograms, enhancing delineation of endocardial borders and detection of intracardiac abnormalities, with the SF6 component exhibiting a terminal half-life of approximately 10 minutes in blood following intravenous administration at 0.3 mL/kg doses.[50][51] Clinical studies report low rates of adverse events, including transient minor side effects like headache or nausea, with no observed deaths, myocardial infarctions, or anaphylaxis in pharmacological stress echocardiography using SonoVue.[52] In ophthalmology, SF6 is employed as an expansile gas tamponade in vitreoretinal procedures, such as pars plana vitrectomy for macular holes or retinal detachment repair, where 20-25% mixtures with air or oxygen promote tissue apposition by expanding over 1-2 days due to SF6's lower solubility compared to alternatives like perfluoropropane (C3F8).[53][54] Such mixtures reduce short-term postoperative hypotony risks in sutureless 25-gauge vitrectomy by providing intraocular pressure support without excessive expansion. Off-label applications include voiding urosonography for detecting vesicoureteral reflux in children, leveraging SF6 microbubbles for safe, non-nephrotoxic contrast.[55] As a tracer gas, SF6's chemical inertness, low toxicity, and high detectability via electron capture detectors enable precise quantification at parts-per-trillion levels, making it suitable for ventilation assessments.[56] In building and laboratory settings, it measures air changes per hour, evaluates fume hood containment per ASHRAE 110 standards, and detects leaks in closed systems like condenser tubes or HVAC ducts.[57][58] Environmental and agricultural research employs SF6 to trace atmospheric dispersion, mine airflow patterns, and ruminant enteric methane emissions, where rumen boluses release calibrated SF6 amounts for breath sampling and flux calculation via mass balance.[59][58] These applications exploit SF6's non-reactivity and stability under physiological or ambient conditions, though its potent greenhouse properties necessitate minimal release volumes.[56]Miscellaneous Industrial Applications

Sulfur hexafluoride serves as a cover gas in magnesium die casting and smelting processes, where it is introduced in low concentrations—typically less than 1% mixed with air or air/carbon dioxide—over molten magnesium to inhibit oxidation and prevent combustion.[60] This application leverages SF6's chemical inertness and density to form a protective blanket, reducing emissions of magnesium oxide and improving casting yield, with the U.S. magnesium industry historically relying on it for primary ingot production and recycling operations.[61] Although alternatives like hydrofluorocarbons have been adopted in some regions to mitigate environmental concerns, SF6 remains in use where its superior efficacy justifies the trade-offs.[62] In semiconductor fabrication, SF6 functions as a plasma etching gas for selectively removing silicon and other materials during microfabrication of integrated circuits, photovoltaic cells, and micro-electro-mechanical systems.[63] Its high fluorine content enables anisotropic etching with precise control, contributing to the production of advanced electronic components, though it accounts for a smaller fraction of total SF6 consumption compared to electrical uses.[64] Industry reports indicate SF6's role in chamber cleaning and wafer processing, often in combination with other fluorocarbons like NF3.[65] SF6 has been employed as a fill gas in insulated glazing units for double-pane windows since the 1970s, enhancing acoustic insulation by reducing sound transmission velocity through the gas space, sometimes in mixtures with argon for combined thermal and noise benefits.[30] This application exploits the gas's high molecular weight and low thermal conductivity to achieve U-values as low as 0.23 Btu/h·ft²·°F in specialized European windows, though its use has declined due to cost and regulatory pressures favoring less potent gases. Minor applications include aluminum degassing and leak detection in industrial systems, where SF6's detectability and stability provide traceability without reacting with processed materials.[48]Environmental and Atmospheric Role

Greenhouse Gas Potential

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) exhibits one of the highest global warming potentials (GWPs) among greenhouse gases, primarily due to its strong infrared absorption bands in the atmospheric window region (8–12 μm) and its prolonged persistence in the atmosphere. The 100-year GWP of SF6, which integrates its radiative forcing relative to an equivalent mass of carbon dioxide (CO2) over a century, is estimated at 23,500 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments.[5] More recent evaluations, such as those aligned with IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), place this value at 24,300, reflecting refinements in spectroscopic data and lifetime modeling.[66] These metrics quantify SF6's capacity to trap outgoing longwave radiation, with per-molecule radiative efficiency approximately three times that of CFC-11, a historically significant chlorofluorocarbon.[67] The atmospheric lifetime of SF6 underpins its elevated GWP, estimated at 3,200 years based on mesospheric photolysis and electron attachment as primary sink mechanisms, as derived from in situ measurements in the polar vortex and global modeling.[68] This longevity—far exceeding that of shorter-lived gases like methane (∼12 years)—amplifies cumulative climate forcing, though some studies propose shorter lifetimes (e.g., 580–1,400 years) when accounting for enhanced mesospheric loss rates, highlighting ongoing uncertainties in sink parameterization.[69] SF6's potency is further evidenced by its inclusion in the Kyoto Protocol as one of the six primary greenhouse gases, where even trace emissions contribute disproportionately to radiative imbalance due to the absence of natural sources and its fully fluorinated structure, which resists hydrolysis and oxidation in the troposphere.[5] Despite these intrinsic properties, SF6's overall climate influence remains modulated by its low global mixing ratios (typically 10–11 parts per trillion as of 2023), which limit absolute forcing compared to abundant gases like CO2; however, the GWP metric isolates per-unit potential, emphasizing the need for emission controls in high-integrity applications.[69] Empirical validation of these values draws from laboratory infrared spectra and field observations, underscoring SF6's role as a benchmark for synthetic fluorinated gases in climate modeling.[70]Sources of Emissions and Global Concentrations

The primary sources of sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) emissions are fugitive releases from its use as an electrical insulator in high-voltage switchgear and circuit breakers, accounting for the majority of global emissions due to leaks during operation, maintenance, and equipment decommissioning. In the United States, approximately 67% of SF6 emissions in 2022 originated from the electrical transmission and distribution sector, with additional contributions from semiconductor manufacturing processes such as plasma etching. Globally, emissions have been driven by expanding electrical infrastructure in developing regions, with annual emissions increasing by 24% between 2008 and 2018, largely attributable to heightened deployment of SF6-filled switchgear in countries like China. Lesser sources include magnesium production and double glazing manufacturing, though these represent under 5% of total emissions based on national inventories.[5][71][72] Global emission inventories estimate total anthropogenic SF6 releases at around 7-9 gigagrams (Gg) per year during the 2010s, with inverse modeling analyses for 2005-2021 indicating regionally resolved patterns dominated by East Asia, particularly China, which contributed over 50% of emissions by the early 2020s due to rapid grid expansion. These estimates derive from atmospheric observations and bottom-up inventories, revealing discrepancies where reported national figures understate actual releases by up to 250% in some cases, as verified by top-down measurements. While U.S. emissions declined by about 40-50% from 2007 to 2018 through voluntary reductions and equipment improvements, global trends show sustained growth, with China's emissions nearly doubling from 2.6 Gg/year in 2011 (34% of global total) to higher levels by 2021, equivalent to 125 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent.[73][72][74] Atmospheric concentrations of SF6 have risen steadily since industrial production began in the 1950s, reflecting its long lifetime of over 3,000 years and minimal natural sinks, with globally averaged mole fractions reaching approximately 11 parts per trillion (ppt) by the mid-2020s based on marine surface observations. Monthly mean abundances, as measured by networks like NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory and AGAGE, show an upward trend of about 0.2-0.3 ppt per year in recent decades, correlating directly with emission growth in industrialized and emerging economies. Pollution-free measurements from remote stations confirm near-uniform mixing in the troposphere, with concentrations in 2024-2025 exceeding pre-industrial levels by two orders of magnitude, underscoring the gas's persistence and traceability to human sources.[6][72]Relative Climate Impact and Empirical Data

Sulfur hexafluoride possesses a 100-year global warming potential (GWP) of 23,500 relative to carbon dioxide, as assessed in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), reflecting its strong infrared absorption and atmospheric persistence with a lifetime exceeding 3,200 years.[66] This metric quantifies the radiative efficiency of SF6, approximately 0.57 W m⁻² ppb⁻¹, which drives its outsized per-molecule impact compared to CO₂'s baseline of 1.[75] Empirical measurements from the NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory indicate global mean tropospheric SF6 mole fractions reached approximately 11 parts per trillion (ppt) by 2023, with a consistent annual growth rate of 0.24 ppt yr⁻¹ observed since the late 1990s, derived from marine surface air samples.[6] These concentrations, while rising due to anthropogenic emissions estimated at 6-8 Gg yr⁻¹ globally (with China accounting for over 50% since 2011), remain orders of magnitude lower than CO₂'s ~420 ppm, limiting SF6's absolute radiative forcing to about 0.004-0.006 W m⁻² as of 2020—less than 0.3% of total anthropogenic forcing (~2.7 W m⁻²).[72][69] In CO₂-equivalent terms, annual SF6 emissions equate to roughly 140-190 Mt CO₂e, representing under 0.4% of global greenhouse gas emissions (~50 Gt CO₂e yr⁻¹), underscoring that its climate influence, though potent per unit, is marginal overall due to minimal release volumes primarily from electrical equipment leaks rather than combustion-scale sources like fossil fuels.[69] Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) network data corroborate this trend, showing pollution-free monthly means stabilizing at similar ppt levels across remote stations, with no evidence of disproportionate atmospheric accumulation relative to other fluorinated gases.[69] Thus, while SF6 exemplifies high-potency forcing agents, empirical budgets reveal its net contribution as a trace perturbation amid dominant CO₂-driven changes.[76]Alternatives, Regulations, and Debates

Technological Alternatives to SF6

Technological alternatives to sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) in high-voltage electrical equipment primarily target gas-insulated switchgear (GIS) and circuit breakers, where SF6's superior dielectric strength and arc-quenching properties have historically enabled compact designs.[77] These substitutes include fluorine-free gases, low global warming potential (GWP) fluorinated gas mixtures, vacuum interrupters, and solid insulation systems, driven by SF6's GWP of 23,500 over 100 years.[78] While feasible for many applications, alternatives often require higher operating pressures, larger equipment footprints, or modified designs to achieve comparable performance, potentially increasing costs by 20-50% in some cases.[79] Fluorine-free options, such as "clean air" (purified dry air or nitrogen-oxygen mixtures), provide zero GWP and have been commercialized for voltages up to 550 kV.[80] Siemens Energy's blue GIS uses pressurized dry air with particle traps, achieving insulation levels equivalent to SF6 through optimized electrode geometries, though arc interruption relies on vacuum or hybrid mechanisms rather than gas alone.[79] These systems exhibit dielectric breakdown voltages about 50-70% of SF6 at atmospheric pressure but match it at 1.5-2 times higher pressures, resulting in bulkier enclosures that can expand substation footprints by up to 30%.[81] Low-GWP fluorinated mixtures, like GE's g3 (a blend of 4-6% C4F7N fluoronitrile with CO2 and trace O2), offer GWP reductions to under 1% of SF6 while retaining 90-98% of its dielectric strength at 1.4-1.5 times SF6's pressure.[82] Similarly, 3M's Novec 4710 (CF3CF(OCF2CF2)2OCF3) mixed with CO2 provides arc-quenching capabilities suitable for circuit breakers up to 420 kV, with full-load interruption ratings matching SF6 in lab tests but requiring toxicity assessments due to decomposition products.[83] These gases have higher boiling points (-30°C to -20°C versus SF6's -64°C), limiting cold-weather performance unless pressurized further, and recycling processes remain under development, with current disposal as the primary end-of-life option.[84] Vacuum interrupters, often paired with solid epoxy or polymer insulation, eliminate gases entirely and dominate medium-voltage (up to 52 kV) applications, interrupting currents up to 63 kA with contact distances under 10 mm.[85] For high-voltage extensions, hybrid designs combine vacuum bottles for switching with air or solid insulation for dielectrics, as in Hitachi Energy's EconiQ 550 kV breakers, which achieve SF6-equivalent reliability without fluorocarbons.[80] Vacuum technology excels in non-sustained fault interruption but may produce metal vapors requiring filters, and scaling to ultra-high voltages (>800 kV) remains limited by electrode erosion over 30,000 operations.[81]| Alternative | GWP (100-yr) | Dielectric Strength Relative to SF6 | Typical Voltage Range | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clean Air | 0 | 50-70% at equiv. pressure | Up to 550 kV | Larger footprint, pressure needs |

| g3 Mixture | <120 | 90-98% at 1.4x pressure | Up to 420 kV | Higher cost, toxicity of components |

| Novec 4710/CO2 | ~2,000 | 85-95% at 1.2-1.5x pressure | Up to 245 kV | Boiling point, decomposition risks |

| Vacuum/Solid | 0 | Comparable in MV; hybrid for HV | Up to 550 kV (hybrid) | Erosion in high ops, size for HV |

![Abundance and growth rate of SF 6 in Earth's troposphere (1978-2018).[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/AGAGE_sulfur_hexafluroride_growth.png/500px-AGAGE_sulfur_hexafluroride_growth.png)