Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

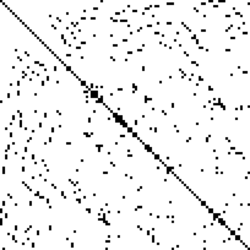

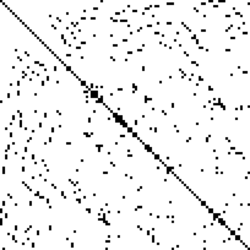

Sparse matrix

View on WikipediaExample of sparse matrix

|

The above sparse matrix contains only 9 non-zero elements, with 26 zero elements. Its sparsity is 74%, and its density is 26%.

|

In numerical analysis and scientific computing, a sparse matrix or sparse array is a matrix in which most of the elements are zero.[1] There is no strict definition regarding the proportion of zero-value elements for a matrix to qualify as sparse but a common criterion is that the number of non-zero elements is roughly equal to the number of rows or columns. By contrast, if most of the elements are non-zero, the matrix is considered dense.[1] The number of zero-valued elements divided by the total number of elements (e.g., m × n for an m × n matrix) is sometimes referred to as the sparsity of the matrix.

Conceptually, sparsity corresponds to systems with few pairwise interactions. For example, consider a line of balls connected by springs from one to the next: this is a sparse system, as only adjacent balls are coupled. By contrast, if the same line of balls were to have springs connecting each ball to all other balls, the system would correspond to a dense matrix. The concept of sparsity is useful in combinatorics and application areas such as network theory and numerical analysis, which typically have a low density of significant data or connections. Large sparse matrices often appear in scientific or engineering applications when solving partial differential equations.

When storing and manipulating sparse matrices on a computer, it is beneficial and often necessary to use specialized algorithms and data structures that take advantage of the sparse structure of the matrix. Specialized computers have been made for sparse matrices,[2] as they are common in the machine learning field.[3] Operations using standard dense-matrix structures and algorithms are slow and inefficient when applied to large sparse matrices as processing and memory are wasted on the zeros. Sparse data is by nature more easily compressed and thus requires significantly less storage. Some very large sparse matrices are infeasible to manipulate using standard dense-matrix algorithms.

Special cases

[edit]Banded

[edit]A band matrix is a special class of sparse matrix where the non-zero elements are concentrated near the main diagonal. A band matrix is characterised by its lower and upper bandwidths, which refer to the number of diagonals below and above (respectively) the main diagonal between which all of the non-zero entries are contained.

Formally, the lower bandwidth of a matrix A is the smallest number p such that the entry ai,j vanishes whenever i > j + p. Similarly, the upper bandwidth is the smallest number p such that ai,j = 0 whenever i < j − p (Golub & Van Loan 1996, §1.2.1). For example, a tridiagonal matrix has lower bandwidth 1 and upper bandwidth 1. As another example, the following sparse matrix has lower and upper bandwidth both equal to 3. Notice that zeros are represented with dots for clarity.

Matrices with reasonably small upper and lower bandwidth are known as band matrices and often lend themselves to simpler algorithms than general sparse matrices; or one can sometimes apply dense matrix algorithms and gain efficiency simply by looping over a reduced number of indices.

By rearranging the rows and columns of a matrix A it may be possible to obtain a matrix A′ with a lower bandwidth. A number of algorithms are designed for bandwidth minimization.

Diagonal

[edit]A diagonal matrix is the extreme case of a banded matrix, with zero upper and lower bandwidth. A diagonal matrix can be stored efficiently by storing just the entries in the main diagonal as a one-dimensional array, so a diagonal n × n matrix requires only n entries in memory.

Symmetric

[edit]A symmetric sparse matrix arises as the adjacency matrix of an undirected graph; it can be stored efficiently as an adjacency list.

Block diagonal

[edit]A block-diagonal matrix consists of sub-matrices along its diagonal blocks. A block-diagonal matrix A has the form

where Ak is a square matrix for all k = 1, ..., n.

Use

[edit]Reducing fill-in

[edit]The fill-in of a matrix are those entries that change from an initial zero to a non-zero value during the execution of an algorithm. To reduce the memory requirements and the number of arithmetic operations used during an algorithm, it is useful to minimize the fill-in by switching rows and columns in the matrix. The symbolic Cholesky decomposition can be used to calculate the worst possible fill-in before doing the actual Cholesky decomposition.

There are other methods than the Cholesky decomposition in use. Orthogonalization methods (such as QR factorization) are common, for example, when solving problems by least squares methods. While the theoretical fill-in is still the same, in practical terms the "false non-zeros" can be different for different methods. And symbolic versions of those algorithms can be used in the same manner as the symbolic Cholesky to compute worst case fill-in.

Solving sparse matrix equations

[edit]Both iterative and direct methods exist for sparse matrix solving.

Iterative methods, such as conjugate gradient method and GMRES utilize fast computations of matrix-vector products , where matrix is sparse. The use of preconditioners can significantly accelerate convergence of such iterative methods.

Storage

[edit]A matrix is typically stored as a two-dimensional array. Each entry in the array represents an element ai,j of the matrix and is accessed by the two indices i and j. Conventionally, i is the row index, numbered from top to bottom, and j is the column index, numbered from left to right. For an m × n matrix, the amount of memory required to store the matrix in this format is proportional to m × n (disregarding the fact that the dimensions of the matrix also need to be stored).

In the case of a sparse matrix, substantial memory requirement reductions can be realized by storing only the non-zero entries. Depending on the number and distribution of the non-zero entries, different data structures can be used and yield huge savings in memory when compared to the basic approach. The trade-off is that accessing the individual elements becomes more complex and additional structures are needed to be able to recover the original matrix unambiguously.

Formats can be divided into two groups:

- Those that support efficient modification, such as DOK (Dictionary of keys), LIL (List of lists), or COO (Coordinate list). These are typically used to construct the matrices.

- Those that support efficient access and matrix operations, such as CSR (Compressed Sparse Row) or CSC (Compressed Sparse Column).

Dictionary of keys (DOK)

[edit]DOK consists of a dictionary that maps (row, column)-pairs to the value of the elements. Elements that are missing from the dictionary are taken to be zero. The format is good for incrementally constructing a sparse matrix in random order, but poor for iterating over non-zero values in lexicographical order. One typically constructs a matrix in this format and then converts to another more efficient format for processing.[4]

List of lists (LIL)

[edit]LIL stores one list per row, with each entry containing the column index and the value. Typically, these entries are kept sorted by column index for faster lookup. This is another format good for incremental matrix construction.[5]

Coordinate list (COO)

[edit]COO stores a list of (row, column, value) tuples. Ideally, the entries are sorted first by row index and then by column index, to improve random access times. This is another format that is good for incremental matrix construction.[6]

Compressed sparse row (CSR, CRS or Yale format)

[edit]The compressed sparse row (CSR) or compressed row storage (CRS) or Yale format represents a matrix M by three (one-dimensional) arrays, that respectively contain nonzero values, the extents of rows, and column indices. It is similar to COO, but compresses the row indices, hence the name. This format allows fast row access and matrix-vector multiplications (Mx). The CSR format has been in use since at least the mid-1960s, with the first complete description appearing in 1967.[7]

The CSR format stores a sparse m × n matrix M in row form using three (one-dimensional) arrays (V, COL_INDEX, ROW_INDEX). Let NNZ denote the number of nonzero entries in M. (Note that zero-based indices shall be used here.)

- The arrays V and COL_INDEX are of length NNZ, and contain the non-zero values and the column indices of those values respectively

- COL_INDEX contains the column in which the corresponding entry V is located.

- The array ROW_INDEX is of length m + 1 and encodes the index in V and COL_INDEX where the given row starts. This is equivalent to ROW_INDEX[j] encoding the total number of nonzeros above row j. The last element is NNZ , i.e., the fictitious index in V immediately after the last valid index NNZ − 1.[8]

For example, the matrix is a 4 × 4 matrix with 4 nonzero elements, hence

V = [ 5 8 3 6 ] COL_INDEX = [ 0 1 2 1 ] ROW_INDEX = [ 0 1 2 3 4 ]

assuming a zero-indexed language.

To extract a row, we first define:

row_start = ROW_INDEX[row] row_end = ROW_INDEX[row + 1]

Then we take slices from V and COL_INDEX starting at row_start and ending at row_end.

To extract the row 1 (the second row) of this matrix we set row_start=1 and row_end=2. Then we make the slices V[1:2] = [8] and COL_INDEX[1:2] = [1]. We now know that in row 1 we have one element at column 1 with value 8.

In this case the CSR representation contains 13 entries, compared to 16 in the original matrix. The CSR format saves on memory only when NNZ < (m (n − 1) − 1) / 2.

Another example, the matrix is a 4 × 6 matrix (24 entries) with 8 nonzero elements, so

V = [ 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 ] COL_INDEX = [ 0 1 1 3 2 3 4 5 ] ROW_INDEX = [ 0 2 4 7 8 ]

The whole is stored as 21 entries: 8 in V, 8 in COL_INDEX, and 5 in ROW_INDEX.

- ROW_INDEX splits the array V into rows:

(10, 20) (30, 40) (50, 60, 70) (80), indicating the index of V (and COL_INDEX) where each row starts and ends; - COL_INDEX aligns values in columns:

(10, 20, ...) (0, 30, 0, 40, ...)(0, 0, 50, 60, 70, 0) (0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 80).

Note that in this format, the first value of ROW_INDEX is always zero and the last is always NNZ, so they are in some sense redundant (although in programming languages where the array length needs to be explicitly stored, NNZ would not be redundant). Nonetheless, this does avoid the need to handle an exceptional case when computing the length of each row, as it guarantees the formula ROW_INDEX[i + 1] − ROW_INDEX[i] works for any row i. Moreover, the memory cost of this redundant storage is likely insignificant for a sufficiently large matrix.

The (old and new) Yale sparse matrix formats are instances of the CSR scheme. The old Yale format works exactly as described above, with three arrays; the new format combines ROW_INDEX and COL_INDEX into a single array and handles the diagonal of the matrix separately.[9]

For logical adjacency matrices, the data array can be omitted, as the existence of an entry in the row array is sufficient to model a binary adjacency relation.

It is likely known as the Yale format because it was proposed in the 1977 Yale Sparse Matrix Package report from Department of Computer Science at Yale University.[10]

Compressed sparse column (CSC or CCS)

[edit]CSC is similar to CSR except that values are read first by column, a row index is stored for each value, and column pointers are stored. For example, CSC is (val, row_ind, col_ptr), where val is an array of the (top-to-bottom, then left-to-right) non-zero values of the matrix; row_ind is the row indices corresponding to the values; and, col_ptr is the list of val indexes where each column starts. The name is based on the fact that column index information is compressed relative to the COO format. One typically uses another format (LIL, DOK, COO) for construction. This format is efficient for arithmetic operations, column slicing, and matrix-vector products. This is the traditional format for specifying a sparse matrix in MATLAB (via the sparse function).

Software

[edit]Many software libraries support sparse matrices, and provide solvers for sparse matrix equations. The following are open-source:

- PETSc, a large C library, containing many different matrix solvers for a variety of matrix storage formats.

- Trilinos, a large C++ library, with sub-libraries dedicated to the storage of dense and sparse matrices and solution of corresponding linear systems.

- Eigen3 is a C++ library that contains several sparse matrix solvers. However, none of them are parallelized.

- MUMPS (MUltifrontal Massively Parallel sparse direct Solver), written in Fortran90, is a frontal solver.

- deal.II, a finite element library that also has a sub-library for sparse linear systems and their solution.

- DUNE, another finite element library that also has a sub-library for sparse linear systems and their solution.

- Armadillo provides a user-friendly C++ wrapper for BLAS and LAPACK.

- SciPy provides support for several sparse matrix formats, linear algebra, and solvers.

- ALGLIB is a C++ and C# library with sparse linear algebra support

- ARPACK Fortran 77 library for sparse matrix diagonalization and manipulation, using the Arnoldi algorithm

- SLEPc Library for solution of large scale linear systems and sparse matrices

- scikit-learn, a Python library for machine learning, provides support for sparse matrices and solvers

- SparseArrays is a Julia standard library.

- PSBLAS, software toolkit to solve sparse linear systems supporting multiple formats also on GPU.

History

[edit]The term sparse matrix was possibly coined by Harry Markowitz who initiated some pioneering work but then left the field.[11]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Yan, Di; Wu, Tao; Liu, Ying; Gao, Yang (2017). "An efficient sparse-dense matrix multiplication on a multicore system". 2017 IEEE 17th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT). IEEE. pp. 1880–3. doi:10.1109/icct.2017.8359956. ISBN 978-1-5090-3944-9.

The computation kernel of DNN is large sparse-dense matrix multiplication. In the field of numerical analysis, a sparse matrix is a matrix populated primarily with zeros as elements of the table. By contrast, if the number of non-zero elements in a matrix is relatively large, then it is commonly considered a dense matrix. The fraction of zero elements (non-zero elements) in a matrix is called the sparsity (density). Operations using standard dense-matrix structures and algorithms are relatively slow and consume large amounts of memory when applied to large sparse matrices.

- ^ "Cerebras Systems Unveils the Industry's First Trillion Transistor Chip". www.businesswire.com. 2019-08-19. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

The WSE contains 400,000 AI-optimized compute cores. Called SLAC™ for Sparse Linear Algebra Cores, the compute cores are flexible, programmable, and optimized for the sparse linear algebra that underpins all neural network computation

- ^ "Argonne National Laboratory Deploys Cerebras CS-1, the World's Fastest Artificial Intelligence Computer | Argonne National Laboratory". www.anl.gov (Press release). Retrieved 2019-12-02.

The WSE is the largest chip ever made at 46,225 square millimeters in area, it is 56.7 times larger than the largest graphics processing unit. It contains 78 times more AI optimized compute cores, 3,000 times more high speed, on-chip memory, 10,000 times more memory bandwidth, and 33,000 times more communication bandwidth.

- ^ See

scipy.sparse.dok_matrix - ^ See

scipy.sparse.lil_matrix - ^ See

scipy.sparse.coo_matrix - ^ Buluç, Aydın; Fineman, Jeremy T.; Frigo, Matteo; Gilbert, John R.; Leiserson, Charles E. (2009). Parallel sparse matrix-vector and matrix-transpose-vector multiplication using compressed sparse blocks (PDF). ACM Symp. on Parallelism in Algorithms and Architectures. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.211.5256.

- ^ Saad 2003

- ^ Bank, Randolph E.; Douglas, Craig C. (1993), "Sparse Matrix Multiplication Package (SMMP)" (PDF), Advances in Computational Mathematics, 1: 127–137, doi:10.1007/BF02070824, S2CID 6412241

- ^ Eisenstat, S. C.; Gursky, M. C.; Schultz, M. H.; Sherman, A. H. (April 1977). "Yale Sparse Matrix Package" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Oral history interview with Harry M. Markowitz, pp. 9, 10.

References

[edit]- Golub, Gene H.; Van Loan, Charles F. (1996). Matrix Computations (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins. ISBN 978-0-8018-5414-9.

- Stoer, Josef; Bulirsch, Roland (2002). Introduction to Numerical Analysis (3rd ed.). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-21738-3. ISBN 978-0-387-95452-3.

- Tewarson, Reginald P. (1973). Sparse Matrices. Mathematics in science and engineering. Vol. 99. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-685650-8. OCLC 316552948. (This book, by a professor at the State University of New York at Stony Book, was the first book exclusively dedicated to Sparse Matrices. Graduate courses using this as a textbook were offered at that University in the early 1980s).

- Bank, Randolph E.; Douglas, Craig C. "Sparse Matrix Multiplication Package" (PDF).

- Pissanetzky, Sergio (1984). Sparse Matrix Technology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-557580-5. OCLC 680489638.

- Snay, Richard A. (1976). "Reducing the profile of sparse symmetric matrices". Bulletin Géodésique. 50 (4): 341–352. Bibcode:1976BGeod..50..341S. doi:10.1007/BF02521587. hdl:2027/uc1.31210024848523. S2CID 123079384. Also NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NGS-4, National Geodetic Survey, Rockville, MD. Referencing Saad 2003.

- Scott, Jennifer; Tuma, Miroslav (2023). Algorithms for Sparse Linear Systems. Nečas Center Series. Birkhauser. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-25820-6. ISBN 978-3-031-25819-0. (Open Access)

Further reading

[edit]- Gibbs, Norman E.; Poole, William G.; Stockmeyer, Paul K. (1976). "A comparison of several bandwidth and profile reduction algorithms". ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 2 (4): 322–330. doi:10.1145/355705.355707. S2CID 14494429.

- Gilbert, John R.; Moler, Cleve; Schreiber, Robert (1992). "Sparse matrices in MATLAB: Design and Implementation". SIAM Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications. 13 (1): 333–356. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.1054. doi:10.1137/0613024.

- Sparse Matrix Algorithms Research at the Texas A&M University.

- SuiteSparse Matrix Collection

- SMALL project A EU-funded project on sparse models, algorithms and dictionary learning for large-scale data.

- Hackbusch, Wolfgang (2016). Iterative Solution of Large Sparse Systems of Equations. Applied Mathematical Sciences. Vol. 95 (2nd ed.). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28483-5. ISBN 978-3-319-28481-1.

- Saad, Yousef (2003). Iterative Methods for Sparse Linear Systems. SIAM. doi:10.1137/1.9780898718003. ISBN 978-0-89871-534-7. OCLC 693784152.

- Davis, Timothy A. (2006). Direct Methods for Sparse Linear Systems. SIAM. doi:10.1137/1.9780898718881. ISBN 978-0-89871-613-9. OCLC 694087302.

Sparse matrix

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A sparse matrix is an matrix in which most elements are zero, such that the number of non-zero elements, denoted as nnz, satisfies nnz .[1] More formally, for square matrices, a matrix is sparse if nnz is proportional to rather than .[3] In general, a matrix is sparse if nnz = for some , assuming .[4] The density of a matrix is defined as , measuring the proportion of non-zero entries; the sparsity is density.[5] Matrices are typically considered sparse when this density is low, often much less than 1% non-zero entries in many numerical applications.[6] In practice, even lower densities, such as less than 0.01%, are common in large-scale problems where sparsity exploitation is crucial.[7] Unlike dense matrices, which store all elements explicitly in memory regardless of their values, sparse matrices use specialized representations that store only the non-zero values and their indices to reduce memory usage.[8] To illustrate, consider a matrix with only two non-zero entries: Here, nnz = 2 and density = (22.2%), which serves as a simple example but for larger dimensions, much lower densities are typical for matrices treated as sparse.[5]Motivations

Sparse matrices commonly arise in real-world modeling problems where the data structure inherently features a predominance of zeros, reflecting the absence of interactions or dependencies. For instance, in graph theory, adjacency matrices represent networks of nodes and edges, with zero entries indicating no direct connections between vertices—a natural sparsity in many real-world graphs like social or transportation networks.[9] Similarly, in finite element methods for solving partial differential equations in engineering and physics, the resulting coefficient matrices are sparse because the local support of basis functions limits influences to nearby elements, leaving distant entries as zeros.[10] The primary motivation for specialized treatment of sparse matrices lies in the substantial computational savings they enable, particularly in memory usage and processing time for large systems. Dense matrix representations require storage for all elements, leading to space for an matrix, whereas sparse formats store only the non-zero entries (nnz), often achieving dramatic reductions—sometimes by orders of magnitude in applications with low density. Operations like matrix-vector multiplication or addition can thus scale as rather than , making iterative solvers and simulations feasible on standard hardware.[11][12] Without sparse techniques, handling these matrices as dense would pose severe challenges, especially in large-scale scientific computing where systems with millions or billions of variables are common. Dense storage could demand terabytes or petabytes of memory for simulations in fields like climate modeling or structural analysis, often exceeding available resources and causing computational overflow or infeasibility.[13] These issues underscored the need for sparse methods, which emerged in the mid-20th century amid advances in numerical analysis for solving engineering problems, building on early graph-theoretic insights from the 1950s.[14]Properties

Density and Sparsity Measures

In numerical linear algebra, the sparsity of a matrix is often quantified by the number of non-zero elements, denoted . The density of the matrix, which measures the fraction of non-zero entries, is defined as . The corresponding sparsity ratio is then , representing the proportion of zero entries; a matrix is typically considered sparse if this ratio exceeds 0.5 or if for square matrices of order . Additional metrics include the average number of non-zeros per row, given by , and per column, , which provide insight into the distribution of non-zeros across dimensions. Sparse matrices can exhibit structural sparsity or numerical sparsity. Structural sparsity refers to the fixed pattern of exactly zero entries in the matrix, independent of specific numerical values, and is determined by the positions of non-zeros. In contrast, numerical sparsity accounts for entries that are small in magnitude but not exactly zero, often treated as zeros in computations based on a tolerance threshold to exploit approximate sparsity patterns. This distinction is crucial in applications like optimization, where structural patterns guide algorithm design while numerical considerations affect conditioning and precision. For certain structured sparse matrices, such as banded ones, additional measures like bandwidth and profile characterize the sparsity more precisely. The bandwidth of a matrix is the smallest non-negative integer such that all non-zero entries satisfy .[15] The profile of a matrix, also known as the envelope or wavefront, is defined as , where is the largest such that , providing a measure of the envelope size relevant for storage and elimination algorithms.[16] These metrics are particularly useful for banded cases, where reducing bandwidth or profile minimizes computational fill-in. As an illustrative example, consider an tridiagonal matrix, which has non-zeros only on the main diagonal and the adjacent sub- and super-diagonals, yielding . The resulting density is for large , demonstrating high sparsity as grows.Basic Operations

Basic operations on sparse matrices are designed to exploit their sparsity, ensuring that computations focus only on non-zero elements to maintain efficiency. Addition and subtraction of two sparse matrices and involve aligning their non-zero entries by row and column indices, then performing the arithmetic sum or difference on matching positions while merging the sparsity patterns. If an entry sums to zero, it is excluded from the result to preserve sparsity. The time complexity of these operations is , where denotes the number of non-zero entries, as the algorithm traverses each matrix's non-zeros once.[17][18] Scalar multiplication of a sparse matrix by a scalar is a straightforward operation that scales each non-zero entry by , leaving the sparsity pattern unchanged unless , in which case the result is the zero matrix. This requires time proportional to , making it highly efficient for sparse representations.[17] The transpose of a sparse matrix , denoted , is obtained by swapping the row and column indices of each non-zero entry while preserving the values. This operation does not alter the number of non-zeros and has time complexity , as it simply reindexes the stored entries.[17][19] Sparsity preservation is a key consideration in these operations; addition and subtraction typically maintain or reduce sparsity by merging patterns, but more complex operations like matrix multiplication can introduce fill-in, where new non-zero entries appear in the result, potentially densifying the matrix and increasing storage and computational costs. For instance, the number of non-zeros in the product can grow quadratically in the worst case relative to the inputs, necessitating careful choice of algorithms to minimize fill-in.[20][21] As an illustrative example, consider adding two 3×3 sparse matrices with disjoint non-zero supports: The sum has non-zeros at positions (1,1), (1,2), (2,3), and (3,1), resulting in , with no fill-in due to the disjoint patterns.[17]Special Cases

Banded Matrices

A banded matrix is a sparse matrix in which the non-zero entries are confined to a diagonal band, specifically with lower bandwidth and upper bandwidth . This means that whenever (below the band) or (above the band), where and are row and column indices, respectively. The total bandwidth is then , encompassing the main diagonal and the adjacent subdiagonals and superdiagonals.[22] Storage for an banded matrix requires only the elements within this band, leading to space complexity, a significant improvement over the space needed for a full dense matrix representation. This efficiency is achieved through specialized formats like the banded storage scheme, which stores each diagonal in a compact array.[23] Banded matrices frequently arise in the discretization of boundary value problems for ordinary and partial differential equations using finite difference methods, where the local stencil of the discretization naturally limits non-zeros to nearby diagonals. A key property is that Gaussian elimination for LU factorization preserves the banded structure without introducing fill-in—meaning the lower triangular factor retains bandwidth and the upper triangular factor retains bandwidth —as long as partial pivoting is not required to maintain numerical stability.[24][22] For instance, the tridiagonal matrix with commonly emerges from central finite difference approximations to the second derivative in one-dimensional problems, such as solving on a uniform grid. This yields a system where has 2 on the main diagonal, -1 on the sub- and superdiagonals, and zeros elsewhere, illustrating the banded form directly tied to the differential operator's locality.[25]Symmetric Matrices

A symmetric sparse matrix is a square matrix that satisfies , where denotes the transpose of , meaning the element in the -th position equals that in the -th position.[26] This property holds for real-valued matrices, while for complex-valued cases, the analogous structure is a Hermitian sparse matrix, defined by , where is the conjugate transpose (i.e., the complex conjugate of ).[26] In sparse contexts, symmetry implies that non-zero off-diagonal elements are mirrored across the main diagonal, allowing computational efficiencies without altering the matrix's sparsity pattern.[27] Key properties of symmetric sparse matrices include reduced storage requirements, as only the upper or lower triangular portion (including the diagonal) needs to be stored, effectively halving the space for off-diagonal non-zeros compared to unsymmetric sparse formats.[28] For symmetric positive definite (SPD) matrices—those where for all non-zero vectors —all eigenvalues are real and positive, enabling stable numerical methods like Cholesky factorization without pivoting and ensuring convergence in iterative solvers.[29] This positive definiteness has implications for optimization and stability in sparse linear algebra, as it guarantees the matrix's invertibility and bounds condition numbers in certain applications.[29] Storage adaptations for symmetric sparse matrices typically involve modified compressed formats, such as symmetric compressed sparse row (CSR) or compressed sparse column (CSC), where only the upper (or lower) triangle is explicitly stored, and the symmetry is implicitly enforced during access.[27] For instance, in the Harwell-Boeing format (a precursor to modern sparse standards), symmetric matrices are flagged to indicate triangular storage, reducing memory footprint while preserving access efficiency for operations like matrix-vector multiplication.[28] These formats are implemented in libraries like Intel MKL, ensuring that symmetric structure is respected to avoid redundant data.[27] In eigenvalue problems, the symmetry of sparse matrices makes the Lanczos algorithm particularly suitable, as it generates a tridiagonal matrix in the Krylov subspace that preserves the symmetric eigenstructure, allowing efficient computation of extreme eigenvalues and eigenvectors for large-scale problems.[30] Developed by Cornelius Lanczos in 1950 and adapted for sparse matrices in subsequent works, this iterative method exploits the three-term recurrence inherent to symmetric matrices, achieving faster convergence than general-purpose solvers for extremal spectra.[29] A prominent example of an inherently symmetric sparse matrix is the graph Laplacian , where is the degree matrix (diagonal with vertex degrees) and is the adjacency matrix of an undirected graph; is symmetric and positive semi-definite, with sparsity reflecting the graph's edge density.[31] In graph theory applications, such as spectral partitioning, the Laplacian's symmetry enables Lanczos-based eigenvector computations for tasks like community detection.[30] Challenges in handling symmetric sparse matrices arise during approximations, such as preconditioning or low-rank updates, where numerical errors or truncation can break symmetry, leading to instability in algorithms that rely on it.[32] To address this, techniques like symmetrization—replacing an approximate inverse with —are employed to restore the property while preserving sparsity, though this may introduce minor fill-in or alter conditioning.[32] Such methods are crucial in iterative solvers to maintain the benefits of symmetry without full recomputation.[33]Block Diagonal Matrices

A block diagonal matrix consists of multiple submatrices, or blocks, arranged along the main diagonal, with all off-block-diagonal elements being zero. These blocks may be square or rectangular, though square blocks are common in square overall matrices, and the structure inherently exploits sparsity by confining non-zero entries to these isolated blocks. This form arises naturally in systems where variables can be grouped into independent or weakly coupled subsets.[34] The primary advantages of block diagonal matrices lie in their support for independent operations on each block, which reduces the computational complexity from that of the full matrix dimension to the sum of the individual block sizes. This enables efficient parallel processing, as blocks can be solved or manipulated concurrently without inter-block dependencies, making them particularly suitable for distributed computing environments. Additionally, the structure simplifies analysis and preconditioning in iterative solvers by effectively decoupling the system.[34][35] Permuting a general sparse matrix into block diagonal form is achieved through graph partitioning methods applied to the matrix's adjacency graph, where vertices represent rows/columns and edges indicate non-zero entries. These techniques identify partitions that minimize connections between blocks, revealing or approximating the block structure to enhance parallelism and reduce fill-in during factorization.[36] In multi-physics simulations, such as coupled magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) or plasma models, block diagonal matrices represent decoupled physical components like fluid velocity and magnetic fields, allowing specialized solvers for each block while handling weak couplings via Schur complements. This approach achieves optimal scalability for large-scale systems with mixed discretizations.[35] For storage, block diagonal matrices are typically handled by storing each diagonal block independently in a compact sparse format, such as compressed sparse row (CSR), which avoids allocating space for the zero off-diagonal regions and leverages the modularity for memory-efficient access.[37]Storage Formats

Coordinate and List Formats

The Coordinate (COO) format represents a sparse matrix by storing the row indices, column indices, and corresponding non-zero values in three separate arrays, each of length equal to the number of non-zero elements (nnz). This structure uses O(nnz) space and facilitates straightforward construction from data sources like files or lists, as non-zeros can be appended without predefined ordering. COO is particularly advantageous for converting to other sparse formats, such as sorting the indices for compressed representations, but it lacks efficiency in operations like matrix-vector multiplication due to the need for explicit iteration over all elements.[38] The List of Lists (LIL) format organizes the matrix as a collection of lists, one per row, where each row's list holds tuples of (column index, value) pairs for its non-zero entries. Requiring O(nnz) space, LIL supports efficient incremental construction and modification, such as inserting or deleting elements in specific rows, making it suitable for building matrices dynamically during computations like finite element assembly. It performs well for row-wise operations, like accessing or updating individual rows, but is inefficient for column-wise access or dense arithmetic, often necessitating conversion to formats optimized for such tasks.[39][38] The Dictionary of Keys (DOK) format employs a hash table (dictionary) with keys as (row, column) index tuples mapping to non-zero values, enabling average O(1) time for insertions, deletions, and lookups of individual elements. With O(nnz) space usage plus minor hash overhead, DOK is ideal for scenarios involving frequent, unstructured updates to the matrix, such as during iterative algorithms where non-zero positions evolve. However, it offers poor performance for traversing rows or columns sequentially and for numerical operations, limiting its use to construction phases before conversion to more access-oriented formats.[38] Overall, COO, LIL, and DOK prioritize flexibility for matrix assembly over computational efficiency, with COO best for bulk conversions, LIL for row-centric builds, and DOK for scattered updates; all share the drawback of slower access patterns compared to structured alternatives, typically requiring O(nnz) time for most operations.[38]Example: COO Representation

Consider the following 4×4 sparse matrix , which has only three non-zero elements: In COO format, is stored as three arrays of length 3 (nnz = 3):- Row indices: [0, 1, 3]

- Column indices: [0, 2, 1]

- Values: [5, 3, 2]

Compressed Row and Column Formats

Compressed Sparse Row (CSR), also known as the Yale format, is a compact storage scheme for sparse matrices that organizes non-zero elements in row-major order to enable efficient row-wise access and operations. Developed as part of the Yale Sparse Matrix Package, this format uses three arrays: a row pointer array (indptr) of length (where is the number of rows), a column indices array (col_ind), and a values array (val), each of the latter two containing exactly the number of non-zero elements (nnz). The indptr array stores the cumulative indices where each row's non-zeros begin in col_ind and val, with indptr = 0 and indptr = nnz; within each row segment, col_ind holds the column positions of the non-zeros in increasing order, paired with their values in val. This arrangement achieves O(m + nnz) space complexity, significantly reducing memory usage compared to dense storage for matrices with low density.[40] The Compressed Sparse Column (CSC) format mirrors CSR but transposes the orientation for column-wise efficiency, employing a column pointer array (indptr) of length (where is the number of columns), a row indices array (row_ind), and a values array, with non-zeros stored in column-major order. In CSC, indptr marks the start of column j's non-zeros in row_ind and val, requiring O(n + nnz) space and facilitating operations like transpose-vector multiplications. Both formats assume the matrix is sorted within rows or columns to avoid redundant storage and ensure predictable access patterns.[40] CSR representations are typically constructed from the Coordinate (COO) format, a precursor that lists all non-zero triples (row, column, value), by sorting the entries first by row index and then by column index within rows, followed by building the indptr array from the sorted row boundaries. This conversion process incurs O(nnz log nnz) time due to sorting but yields a structure optimized for computation over the modifiable but slower COO. CSC follows an analogous procedure, sorting by column then row.[40] These formats excel in use cases demanding fast traversal, particularly sparse matrix-vector multiplication (SpMV), where CSR enables sequential row iteration to compute with minimal indirect addressing and improved cache locality, achieving up to vectorized performance on modern processors. In SpMV kernels, CSR's layout aligns with the row-oriented accumulation in y, reducing memory bandwidth demands compared to unsorted formats; for instance, implementations can process 10-100 GFLOPS on CPUs for typical sparse matrices from scientific applications. CSC similarly accelerates column-oriented tasks like solving transposed systems.[41][40] To illustrate CSR, consider the following 4×4 sparse matrix (0-based indexing): This matrix has nnz = 7. The CSR components are:- indptr: [0, 2, 4, 5, 7]

- col_ind: [0, 2, 1, 3, 0, 2, 3]

- val: [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Dictionary-Based Formats

Dictionary-based formats for sparse matrices utilize hash tables, typically implemented as dictionaries, to store non-zero elements using their coordinates as keys and values as the corresponding matrix entries. This approach, exemplified by the Dictionary of Keys (DOK) format, maps pairs of (row, column) indices to the non-zero values, treating absent keys as zeros.[42][43] DOK is particularly suited for dynamic construction of sparse matrices through incremental insertions and deletions, enabling efficient building in scenarios with irregular or evolving sparsity patterns.[42] In the DOK format, the structure subclasses a standard dictionary, allowing O(1) average-time complexity for inserting, updating, or deleting individual elements by their coordinates.[43] This facilitates handling duplicate coordinate entries by overwriting existing values, ensuring unique keys per position, and supports straightforward sparsity queries, such as checking the presence of a non-zero element at a specific index via key lookup.[42] Variants of dictionary-based formats include those employing sorted dictionaries, such as tree-based maps (e.g., using balanced binary search trees), which maintain keys in a specified order (e.g., row-major or lexicographical) to enable efficient ordered iteration or range queries without additional sorting overhead.[44] Advantages of dictionary-based formats include their simplicity for dynamic modifications and random access, making them ideal for applications requiring frequent structural changes, like assembling matrices from scattered data sources.[43] They also inherently avoid storing zeros, reducing memory for highly sparse data, and allow easy querying of sparsity patterns through dictionary operations.[44] However, these formats incur higher memory overhead due to the per-entry metadata in hash tables, such as pointers and hash values, compared to compressed array-based representations.[44] Additionally, hash-based access patterns are not cache-friendly, leading to poorer performance in sequential operations or arithmetic computations, as elements are not stored contiguously.[45] For illustration, consider pseudocode for building a 3x3 sparse matrix incrementally in a DOK-like format:initialize dok = empty dictionary

dok[(0,0)] = 1.0 # insert diagonal element

dok[(1,2)] = 4.0 # insert off-diagonal

dok[(2,1)] = -2.0 # another insertion

# Now dok represents the matrix with non-zeros at specified positions

initialize dok = empty dictionary

dok[(0,0)] = 1.0 # insert diagonal element

dok[(1,2)] = 4.0 # insert off-diagonal

dok[(2,1)] = -2.0 # another insertion

# Now dok represents the matrix with non-zeros at specified positions

Applications

Linear Systems Solving

Solving sparse linear systems of the form , where is an sparse matrix, requires methods that exploit the matrix's low density to achieve computational efficiency. Direct methods compute an exact factorization of , enabling fast solution via substitution, while iterative methods approximate the solution through successive refinements, often preferred for extremely large systems due to lower memory demands. Both approaches must address challenges like numerical stability and the preservation of sparsity. Direct methods primarily rely on sparse LU factorization, decomposing (with permutation for stability) or more generally for QR variants. In sparse LU, Gaussian elimination is adapted to skip zero operations, but fill-in—new nonzeros in the factors—can increase density and cost; strategies to minimize fill-in, such as ordering, are essential to keep the factors sparse.[46] Sparse QR factorization, useful for overdetermined systems or when preserving orthogonality, employs Householder reflections or Givens rotations applied only to nonzero elements, often via multifrontal algorithms that process submatrices (fronts) to control fill-in and enable parallelism.[47] These factorizations allow solving in time post-factorization, where denotes nonzeros, though the factorization phase dominates for sparse . Iterative methods offer an alternative for systems too large for direct factorization, generating a sequence of approximations converging to . Stationary methods like Jacobi and Gauss-Seidel are simple and exploit sparsity directly: Jacobi solves using the diagonal and off-diagonals split into (lower) and (upper), requiring one sparse matrix-vector multiply per iteration; Gauss-Seidel improves this by using updated components immediately, as in , often doubling convergence speed for diagonally dominant sparse matrices.[48] These methods converge if the spectral radius of the iteration matrix is less than 1, but slowly for ill-conditioned systems. To enhance convergence, preconditioning transforms the system to , where is easier to invert. Diagonal preconditioning uses , a trivial sparse approximation that normalizes rows cheaply. More robust are incomplete factorizations, such as ILU(0) (level-0, dropping fill-in beyond the original sparsity pattern) or ILU(k) (retaining fill-in up to level ), which provide as drop-tolerant LU approximations, significantly reducing iteration counts for Krylov methods on sparse indefinite systems.[49] Krylov subspace methods, including GMRES and BiCGSTAB, build solution subspaces from powers of , with each iteration costing for the sparse matrix-vector product, making them scalable for matrices with .[48] For symmetric positive definite (SPD) sparse , the conjugate gradient (CG) method stands out, minimizing the A-norm error over the Krylov subspace and converging in at most steps—practically far fewer for smooth problems like discretized PDEs—via short-recurrence updates that maintain orthogonality without storing prior residuals.[50] Preconditioned CG, using ILU or diagonal , further accelerates this for large-scale applications.[48] Fill-in reduction techniques can be applied prior to these methods to improve sparsity in the effective preconditioner.Graph Representations

Sparse matrices play a central role in representing graphs and networks, where the inherent sparsity arises from the limited connectivity between vertices. The adjacency matrix of an undirected graph with vertices is an square matrix where if there is an edge between vertices and , and otherwise, assuming no self-loops; the matrix is symmetric for undirected graphs.[51] For unweighted graphs, this binary structure ensures high sparsity when the graph has few edges relative to the possible pairs. In weighted graphs, stores the edge weight instead of 1, maintaining sparsity if weights are assigned only to existing edges.[9] For directed graphs, the adjacency matrix is generally asymmetric, with (or the weight) indicating a directed edge from to . Another key representation is the incidence matrix of a directed graph, an matrix where each column corresponds to an edge: for the source vertex of edge , for the target vertex , and 0 elsewhere. This structure captures the orientation of edges and is inherently sparse, with exactly two nonzeros per column.[52] In spectral graph theory, the Laplacian matrix , where is the diagonal degree matrix with equal to the degree of vertex , provides a sparse representation that encodes global graph properties through its eigenvalues. The eigenvalues of reveal information about connectivity, clustering, and expansion in the graph, with the smallest nonzero eigenvalue (algebraic connectivity) measuring how well-connected the graph is. Since and are both sparse, inherits their sparsity, making it efficient for spectral computations on large graphs.[53] The sparsity of these matrix representations directly stems from the graph's structure: for an adjacency matrix of an undirected graph, the number of nonzeros is exactly (accounting for symmetry), which is in typical sparse graphs where . Incidence matrices have nonzeros overall, also . Compressed storage formats, such as those for rows or coordinates, are particularly suitable for these graph-derived sparse matrices to minimize memory usage.[9][11] A representative example is the adjacency matrix for a social network graph, where vertices represent users and edges denote friendships or follows; such graphs are sparse because the average degree (number of connections per user) is low—often around 10 to 100 in networks with millions of vertices—resulting in nonzeros far below the dense size, enabling efficient storage and analysis of relationships.[54]Scientific Simulations

In finite element methods (FEM), sparse matrices arise naturally from the discretization of partial differential equations (PDEs) over unstructured or structured meshes, where the global stiffness matrix is assembled from local element contributions that only connect nearby nodes. This locality ensures that each row of the stiffness matrix has a small, fixed number of non-zero entries—typically 5 to 9 for 2D triangular or quadrilateral elements—reflecting the support of basis functions. For instance, in structural mechanics or heat transfer simulations, the resulting sparse stiffness matrix enables efficient storage and computation, as the vast majority of entries (often over 99%) are zero due to the absence of long-range interactions.[10][55] Time-dependent simulations of physical systems, such as fluid dynamics or reaction-diffusion processes, frequently involve solving systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) or PDEs where sparse Jacobian matrices capture the local dependencies in the discretized operators. These Jacobians, derived from linearizations of nonlinear terms, exhibit structured sparsity patterns that mirror the underlying mesh connectivity, allowing for reduced memory usage and faster evaluations in implicit time-stepping schemes. Efficient computation of such sparse Jacobians via automatic differentiation techniques further accelerates convergence in stiff solvers by minimizing the cost of Newton iterations.[56] Multigrid methods leverage the hierarchical sparsity of matrices arising in PDE discretizations by constructing coarse-level approximations that preserve essential low-frequency modes while coarsening the fine-grid sparsity structure. Algebraic multigrid variants, in particular, generate prolongation and restriction operators directly from the sparse matrix graph, enabling robust preconditioning for ill-conditioned systems without geometric information. This exploitation of sparsity hierarchies achieves near-optimal convergence rates, scaling linearly with the problem size even for highly refined meshes.[57] At extreme scales, sparse matrices in scientific simulations can reach billions of non-zero entries; for example, global climate models solving coupled atmospheric-oceanic PDEs may involve linear systems with up to half a billion unknowns and corresponding sparse operators. Similarly, quantum chemistry simulations using configuration interaction methods produce Hamiltonians with billions to trillions of non-zeros, necessitating specialized sparse solvers to manage the exponential growth in basis size. A representative example is the 2D Poisson equation discretized on a uniform grid via the finite difference method, yielding a sparse matrix with a five-point stencil pattern—effectively pentadiagonal in bandwidth for row-ordered unknowns—and approximately 5 non-zeros per row for large grids.[58][59][55]Algorithms

Matrix-Vector Multiplication

Sparse matrix-vector multiplication (SpMV) computes the product , where is an sparse matrix and is a dense -vector, producing a dense -vector . This operation is a core kernel in iterative solvers and scientific simulations due to its frequent use in approximating solutions to linear systems.[60] The Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) format enables an efficient row-wise traversal for SpMV. In this format, non-zero values of are stored contiguously in a values array, accompanied by column indices and row pointer arrays that delimit the non-zeros per row. The algorithm iterates over each row from 0 to , initializing , and accumulates for each non-zero in that row, where ranges over the column indices of the non-zeros.[60]for i = 0 to m-1 do

y[i] = 0

for k = rowptr[i] to rowptr[i+1] - 1 do

j = colind[k]

y[i] += values[k] * x[j]

end for

end for

for i = 0 to m-1 do

y[i] = 0

for k = rowptr[i] to rowptr[i+1] - 1 do

j = colind[k]

y[i] += values[k] * x[j]

end for

end for

Fill-In Reduction Techniques

In sparse matrix factorizations such as LU or Cholesky decomposition, fill-in refers to the creation of additional nonzero entries in the factor matrices that were not present in the original matrix. This phenomenon arises during Gaussian elimination, where the process of eliminating variables introduces new dependencies, potentially increasing the density of the factors and thus the computational cost and memory requirements.[63] To mitigate fill-in, various ordering strategies permute the rows and columns of the sparse matrix prior to factorization, aiming to minimize the number of new nonzeros generated. The minimum degree ordering heuristic, originally inspired by Markowitz pivoting criteria, selects at each step the variable with the smallest number of nonzero connections in the remaining submatrix, thereby delaying the introduction of dense rows or columns. This approach has been refined over time into approximate minimum degree algorithms that balance accuracy with efficiency in implementation.[64] Another prominent strategy is nested dissection, which recursively partitions the matrix's graph into smaller subgraphs by removing balanced separators, ordering the separator vertices last to control fill propagation. For matrices arising from two-dimensional grid discretizations, nested dissection achieves fill-in bounded by nonzeros, where is the matrix dimension, significantly improving over naive orderings that can lead to fill.[65] Symbolic analysis serves as a preprocessing step to predict the fill-in pattern without performing the full numerical factorization, enabling efficient allocation of storage and planning of computation. By simulating the elimination process on the matrix's sparsity graph, it determines the exact structure of the nonzero entries in the LU or Cholesky factors based on the chosen ordering.[63] This phase is crucial for sparse direct solvers, as it avoids redundant operations on zeros during the subsequent numerical phase.[66] A representative example of fill-in reduction via row permutation involves a small sparse matrix that is initially ill-ordered, leading to excessive fill during LU factorization. Consider the 5×5 matrix which has a banded structure disrupted by the positions of rows 1 and 4. Without permutation, Gaussian elimination introduces fill-in across the upper triangle, resulting in 12 nonzeros in the L and U factors combined. Applying a row permutation that swaps rows 1 and 4 yields now exhibiting a bandwidth of 2, where LU factorization produces only 9 nonzeros in the factors, demonstrating a clear reduction in fill.[66] While these techniques substantially reduce factorization costs, they introduce trade-offs: computing a high-quality ordering, such as via nested dissection, can require time comparable to the factorization itself in worst cases, though approximate methods like minimum degree often achieve near-optimal fill reduction with lower overhead.[63] In practice, the savings in memory and flops during factorization typically outweigh the preprocessing cost for large-scale problems in direct solving of linear systems.Iterative Solution Methods

Iterative solution methods for sparse linear systems generate a sequence of approximate solutions by iteratively minimizing a residual or error measure, leveraging the sparsity of to perform efficient matrix-vector multiplications without forming dense factorizations. These methods are particularly suited for large-scale problems where direct solvers would be prohibitive due to memory and time costs. Among them, Krylov subspace methods construct approximations within expanding subspaces generated from the initial residual, offering robust performance for sparse matrices arising in scientific computing.[48] The conjugate gradient (CG) method, developed by Hestenes and Stiefel in 1952, is a seminal Krylov subspace algorithm for symmetric positive definite matrices. It minimizes the -norm of the error at each step over the Krylov subspace , where is the initial residual, achieving exact solution in at most steps for an matrix. For nonsymmetric systems, the generalized minimal residual (GMRES) method, introduced by Saad and Schultz in 1986, minimizes the Euclidean norm of the residual over the same Krylov subspace, using Arnoldi orthogonalization to build an orthonormal basis. Both methods rely on sparse matrix-vector products (SpMV) as their core operation, which exploits the matrix's nonzero structure for computational efficiency.[50][67][48] Convergence of Krylov methods is influenced by the spectral properties of , particularly its condition number and the spectral radius , which bounds the eigenvalue distribution. For CG, the error reduction after iterations satisfies , showing slower convergence for ill-conditioned matrices common in sparse discretized PDEs. GMRES convergence is harder to bound theoretically but benefits from clustered eigenvalues, with the residual norm decreasing rapidly if the field of values is favorable; however, it can stagnate for matrices with large . Preconditioning transforms the system to (left) or (right), where is easier to invert, improving the effective condition number and accelerating convergence without altering the solution.[48] Common preconditioners for sparse matrices include incomplete LU (ILU) factorization, which computes a sparse approximate lower-upper decomposition by dropping small elements during Gaussian elimination to control fill-in, and multigrid methods, which hierarchically smooth errors across coarse and fine levels using prolongation and restriction operators derived algebraically from . ILU variants like ILU(0) preserve the diagonal and unit structure while omitting off-diagonal fill beyond level zero, providing robustness for mildly nonsymmetric sparse systems. Algebraic multigrid (AMG), as surveyed by Xu in 2017, excels for unstructured sparse matrices by automatically generating coarse-grid approximations via aggregation or smoothed aggregation, achieving mesh-independent convergence rates for elliptic problems.[48][68] Stopping criteria for iterative methods typically monitor the relative residual norm , where is a user-defined tolerance (e.g., to ), ensuring the backward error is small relative to the right-hand side. This criterion balances accuracy and computational cost, as computing the true error requires the exact solution; alternatives like the preconditioned residual may be used for preconditioned iterations. A more refined approach, proposed by Arioli, Duff, and Ruiz (1992), stops when the residual norm falls below a fraction of the discretization or rounding error, preventing over-iteration in noisy environments.[48][69] As an example, the CG algorithm for sparse proceeds as follows, with each iteration involving one SpMV and dot products:1. Choose initial guess x_0; compute r_0 = b - A x_0; p_0 = r_0

2. For k = 0, 1, 2, ... until convergence:

a. α_k = (r_k^T r_k) / (p_k^T A p_k) // SpMV in denominator

b. x_{k+1} = x_k + α_k p_k

c. r_{k+1} = r_k - α_k A p_k // SpMV here

d. β_k = (r_{k+1}^T r_{k+1}) / (r_k^T r_k)

e. p_{k+1} = r_{k+1} + β_k p_k

3. Stop if ||r_{k+1}||_2 / ||b||_2 < ε

1. Choose initial guess x_0; compute r_0 = b - A x_0; p_0 = r_0

2. For k = 0, 1, 2, ... until convergence:

a. α_k = (r_k^T r_k) / (p_k^T A p_k) // SpMV in denominator

b. x_{k+1} = x_k + α_k p_k

c. r_{k+1} = r_k - α_k A p_k // SpMV here

d. β_k = (r_{k+1}^T r_{k+1}) / (r_k^T r_k)

e. p_{k+1} = r_{k+1} + β_k p_k

3. Stop if ||r_{k+1}||_2 / ||b||_2 < ε

Software and Implementations

Open-Source Libraries

Several prominent open-source libraries provide robust support for sparse matrix operations across various programming languages, catering to needs ranging from rapid prototyping to high-performance computing. These libraries implement efficient storage formats such as compressed sparse row (CSR) and coordinate (COO), enabling memory-efficient representation and computation for matrices with predominantly zero entries.[71] In Python, the SciPy library's sparse module offers a user-friendly interface for constructing and manipulating sparse matrices, supporting formats like CSR and COO for efficient storage and operations. It includes linear algebra routines in scipy.sparse.linalg for solving sparse systems via direct and iterative methods, making it ideal for scientific computing workflows integrated with NumPy arrays. SciPy emphasizes ease of use through high-level APIs, though it may incur overhead for very large-scale problems due to Python's interpreted nature.[71] For C++, Eigen provides a template-based sparse module that supports the SparseMatrix class for compressed storage, enabling operations like matrix-vector multiplication and triangular solves. It features sparse LU factorization via the SparseLU solver and a suite of iterative solvers such as Conjugate Gradient and BiCGSTAB for solving linear systems. Eigen prioritizes performance through compile-time optimizations and low-level memory management, achieving high efficiency on multi-core systems without external dependencies. SuiteSparse, implemented in C, is a comprehensive collection of algorithms for sparse linear algebra, with UMFPACK offering direct multifrontal LU factorization for general sparse systems and CHOLMOD providing supernodal Cholesky factorization for symmetric positive definite matrices. These components deliver state-of-the-art performance for direct solvers, often outperforming alternatives in factorization speed and accuracy on challenging matrices from the SuiteSparse Matrix Collection. SuiteSparse is particularly suited for embedded use in larger applications due to its modular design and minimal runtime overhead.[72] Trilinos, a C++-based library developed by Sandia National Laboratories, provides scalable algorithms for solving large-scale, sparse linear and nonlinear problems, with key packages like Epetra and Tpetra for distributed-memory parallel sparse matrices in formats similar to CSR. It includes a variety of solvers, preconditioners (e.g., incomplete factorizations, multigrid), and supports integration with MPI and CUDA for GPU acceleration, making it a cornerstone for high-performance computing applications in engineering and science.[73] PETSc (Portable, Extensible Toolkit for Scientific Computation), available in C and Fortran with Python bindings, specializes in parallel sparse matrix handling for high-performance computing environments. It supports distributed sparse matrices in formats like AIJ (analogous to CSR) and includes a wide array of preconditioners, such as incomplete LU and algebraic multigrid, integrated with scalable iterative solvers like GMRES. PETSc excels in distributed-memory parallelism via MPI, facilitating efficient scaling to thousands of cores for large-scale simulations.[74] Comparisons among these libraries highlight trade-offs in ease of use versus performance: Python-based SciPy offers the simplest integration for prototyping and smaller problems but lags in raw speed compared to compiled options like Eigen or SuiteSparse for sequential tasks.[75] In contrast, Eigen provides a balance of accessibility and efficiency for C++ developers, while SuiteSparse stands out for direct solver benchmarks on irregular matrices. PETSc and Trilinos prioritize scalability in parallel settings, often achieving superior performance on HPC clusters at the cost of a steeper learning curve for setup and configuration.[76][77]Commercial Tools

MATLAB provides comprehensive built-in support for sparse matrices, enabling efficient storage and manipulation through functions likesparse for constructing matrices from triplets of indices and values, and full for conversion to dense format when needed.[78] Arithmetic, logical, and indexing operations are fully compatible with sparse matrices, allowing seamless integration with dense ones.[8] For solving linear systems, MATLAB includes iterative solvers such as pcg, the preconditioned conjugate gradient method, optimized for sparse symmetric positive definite systems.[79]

Intel oneAPI Math Kernel Library (oneMKL) offers optimized routines for sparse matrix operations, including sparse matrix-vector multiplication (SpMV) via Sparse BLAS functions that leverage hardware-specific accelerations for high performance on Intel architectures.[80] It also features PARDISO, a parallel direct sparse solver that handles unsymmetric, symmetric indefinite, and symmetric positive definite matrices, supporting both real and complex systems with multi-core and GPU extensions for industrial-scale computations.[81]

The Numerical Algorithms Group (NAG) Library delivers robust sparse matrix capabilities in both Fortran and C implementations, with Chapter F11 providing linear algebra routines for storage, factorization, and solution of sparse systems.[82] For eigensolvers, it includes FEAST-based algorithms for large sparse eigenvalue problems, applicable to standard, generalized, and polynomial forms in complex, real symmetric, Hermitian, and non-Hermitian cases.[83] LU factorization is supported via routines like F01BRF, which permutes and factors real sparse matrices for subsequent solving.[84]

Commercial sparse matrix tools integrate deeply with finite element analysis (FEA) and computer-aided design (CAD) software, such as ANSYS Mechanical, where sparse direct solvers and preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG) methods handle the large matrices arising in structural simulations, combining iterative and direct approaches for efficiency on complex models.[85]

These proprietary libraries provide key advantages through vendor-specific optimizations, such as hardware-tuned parallelism and single-precision support for memory efficiency, alongside professional technical support and regular updates tailored to enterprise needs.[86][81]