Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aktion T4

View on Wikipedia

| Aktion T4 | |

|---|---|

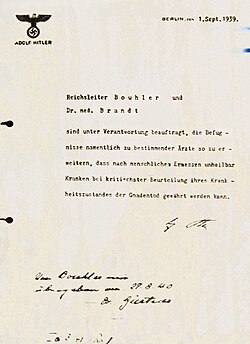

Hitler's order for Aktion T4 | |

| Also known as | T4 Program |

| Location | German-occupied Europe |

| Date | September 1939 – 1945 |

| Incident type | Forced euthanasia |

| Perpetrators | SS |

| Participants | Psychiatric hospitals, T4-Gutachter |

| Victims | 275,000–300,000[1][2][3][a] |

Aktion T4 (German, pronounced [akˈtsi̯oːn teː fiːɐ]) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia which targeted people with disabilities and the mentally ill in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings.[4] The name T4 is an abbreviation of Tiergartenstraße 4, a street address of the Chancellery department set up in early 1940, in the Berlin borough of Tiergarten, which recruited and paid personnel associated with Aktion T4.[5][b] Certain German physicians were authorised to select patients "deemed incurably sick, after most critical medical examination" and then administer to them a "mercy death" (Gnadentod).[7] In October 1939, Adolf Hitler signed a "euthanasia note", backdated to 1 September 1939, which authorised his physician Karl Brandt and Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler to begin the killing.

The killings took place from September 1939 until the end of World War II in Europe in 1945. Between 275,000 and 300,000 people were killed in psychiatric hospitals in Germany, Austria, occupied Poland, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (now the Czech Republic).[8] The number of victims was originally recorded as 70,273 but this number has been increased by the discovery of victims listed in the archives of the former East Germany.[9][c] About half of those killed were taken from church-run asylums.[10] In June 1940, Paul Braune and Fritz von Bodelschwingh, who served as directors of sanatoriums, protested against the killings, being members of the Lutheran Confessing Church.[11]

The Holy See announced on 2 December 1940 that the policy was contrary to divine law and that "the direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed".[12] Bishop Theophil Wurm of the Lutheran Confessing Church "wrote an open letter denouncing the policy."[11] Beginning in the summer of 1941, protests were led in Germany by the bishop of Münster, Clemens von Galen, whose intervention led to "the strongest, most explicit and most widespread protest movement against any Nazi policy since the beginning of the Third Reich", according to Richard J. Evans.[13]

Several reasons have been suggested for the killings, including eugenics, racial hygiene, and saving money.[14] Physicians in German and Austrian asylums continued many of the practices of Aktion T4 until the defeat of Germany in 1945, in spite of its official cessation in August 1941. The informal continuation of the policy led to 93,521 "beds emptied" by the end of 1941.[15][d] Technology developed under Aktion T4, particularly the use of lethal gas on large numbers of people, was taken over by the medical division of the Reich Interior Ministry, along with the personnel of Aktion T4, who participated in the mass murder of Jewish people under Operation Reinhard.[19] The number of people killed was about 200,000 in Germany and Austria, with about 100,000 victims in other European countries.[20] Following the war, a number of the perpetrators were tried and convicted for murder and crimes against humanity.

Background

[edit]At the beginning of the twentieth century, the sterilisation of people carrying what were considered to be hereditary defects and in some cases those exhibiting what was thought to be hereditary "antisocial" behaviour, was a respectable field of medicine. Canada, Denmark, Switzerland and the United States had passed laws enabling coerced sterilisation. Studies conducted in the 1920s ranked Germany as a country that was unusually reluctant to introduce sterilisation legislation.[21] In his book Mein Kampf (1924), Hitler wrote that one day racial hygiene "will appear as a deed greater than the most victorious wars of our present bourgeois era".[22][23]

In July 1933, the "Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring" prescribed compulsory sterilisation for people with conditions thought to be hereditary, such as schizophrenia, epilepsy, Huntington's chorea and "imbecility". Sterilisation was also legalised for chronic alcoholism and other forms of social deviance. The law was administered by the Interior Ministry under Wilhelm Frick through special Hereditary Health Courts (Erbgesundheitsgerichte), which examined the inmates of nursing homes, asylums, prisons, aged-care homes and special schools, to select those to be sterilised.[24] It is estimated that 360,000 people were sterilised under this law between 1933 and 1939.[25]

The policy and research agenda of racial hygiene and eugenics were promoted by Emil Kraepelin.[26] The eugenic sterilisation of persons diagnosed with (and viewed as predisposed to) schizophrenia was advocated by Eugen Bleuler, who presumed racial deterioration because of "mental and physical cripples" in his Textbook of Psychiatry,

The more severely burdened should not propagate themselves... If we do nothing but make mental and physical cripples capable of propagating themselves, and the healthy stocks have to limit the number of their children because so much has to be done for the maintenance of others, if natural selection is generally suppressed, then unless we will get new measures our race must rapidly deteriorate.[27][28][29]

Within the Nazi administration, the idea of including in the programme people with physical disabilities had to be expressed carefully, because the Reich Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, had a deformed right leg.[e] After 1937, the acute shortage of labour in Germany arising from rearmament, meant that anyone capable of work was deemed to be "useful", exempted from the law and the rate of sterilisation declined.[31] The term Aktion T4 is a post-war coining; contemporary German terms included Euthanasie (euthanasia) and Gnadentod (merciful death).[32] The T4 programme stemmed from the Nazi Party policy of "racial hygiene", a belief that the German people needed to be cleansed of racial enemies, which included anyone confined to a mental health facility and people with simple physical disabilities.[33] New insulin shock treatments were used by German psychiatrists to find out if patients with schizophrenia were curable.[34]

Implementation

[edit]

Karl Brandt, Hitler's doctor, and Hans Lammers, the head of the Reich Chancellery, testified after the war that Hitler had told them as early as 1933—when the sterilisation law was passed—that he favoured the killing of the incurably ill but recognised that public opinion would not accept this.[35] In 1935, Hitler told the Leader of Reich Doctors, Gerhard Wagner, that the question could not be taken up in peacetime; "Such a problem could be more smoothly and easily carried out in war". He wrote that he intended to "radically solve" the problem of the mental asylums in such an event.[35]

Aktion T4 began with a "trial" case in late 1938. Hitler instructed Brandt to evaluate a petition sent by two parents for the "mercy killing" of their son who was blind and had physical and developmental disabilities.[36][f] The child, born near Leipzig and eventually identified as Gerhard Kretschmar, was killed in July 1939.[38][39] Hitler instructed Brandt to proceed in the same manner in all similar cases.[40]

On 18 August 1939, three weeks after the killing of the boy, the Reich Committee for the Scientific Registering of Hereditary and Congenital Illnesses was established to register sick children or newborns identified as defective. The secret killing of infants began in 1939 and increased after the war started. By 1941, more than 5,000 children had been killed.[41][42] Hitler was in favour of killing those whom he judged to be lebensunwertes Leben ('Life unworthy of life').[43]

A few months before the "euthanasia" decree, in a 1939 conference with Leonardo Conti, Reich Health Leader and State Secretary for Health in the Interior Ministry, and Hans Lammers, Chief of the Reich Chancellery, Hitler gave as examples the mentally ill who he said could only be "bedded on sawdust or sand" because they "perpetually dirtied themselves" and "put their own excrement into their mouths". This issue, according to the Nazi regime, assumed a new urgency in wartime.[43]

After the invasion of Poland, Hermann Pfannmüller (Head of the State Hospital near Munich) said

It is unbearable to me that the flower of our youth must lose their lives at the front, so that that feeble-minded and asocial element can have a secure existence in the asylum.[44]

Pfannmüller advocated killing by a gradual decrease of food, which he believed was more merciful than poison injections.[45][46]

The German eugenics movement had an extreme wing even before the Nazis came to power. As early as 1920, Alfred Hoche and Karl Binding advocated killing people whose lives were "unworthy of life" (lebensunwertes Leben). Darwinism was interpreted by them as justification of the demand for "beneficial" genes and eradication of the "harmful" ones. Robert Lifton wrote, "The argument went that the best young men died in war, causing a loss to the Volk of the best genes. The genes of those who did not fight (the worst genes) then proliferated freely, accelerating biological and cultural degeneration".[47] The advocacy of eugenics in Germany gained ground after 1930, when the Depression was used to excuse cuts in funding to state mental hospitals, creating squalor and overcrowding.[48]

Many German eugenicists were nationalists and antisemites, who embraced the Nazi regime with enthusiasm. Many were appointed to positions in the Health Ministry and German research institutes. Their ideas were gradually adopted by the majority of the German medical profession, from which Jewish and communist doctors were soon purged.[49] In the 1930s, the Nazi Party had carried out a campaign of propaganda in favour of euthanasia. The National Socialist Racial and Political Office (NSRPA) produced leaflets, posters and short films to be shown in cinemas, pointing out to Germans the cost of maintaining asylums for the incurably ill and insane. These films included The Inheritance (Das Erbe, 1935), Victims of the Past (Opfer der Vergangenheit, 1937), which was given a major première in Berlin and was shown in all German cinemas, and I Accuse (Ich klage an, 1941) which was based on a novel by Hellmuth Unger, a consultant for "child euthanasia".[50]

Killing of children

[edit]

In mid-1939, Hitler authorised the creation of the Reich Committee for the Scientific Registering of Serious Hereditary and Congenital Illnesses (Reichsausschuss zur wissenschaftlichen Erfassung erb- und anlagebedingter schwerer Leiden) led by his physician, Karl Brandt, administered by Herbert Linden of the Interior Ministry, leader of German Red Cross Reichsarzt SS und Polizei Ernst-Robert Grawitz and SS-Oberführer Viktor Brack. Brandt and Bouhler were authorised to approve applications to kill children in relevant circumstances, though Bouhler left the details to subordinates such as Brack and SA-Oberführer Werner Blankenburg.[51][52][53]

Extermination centres were established at six existing psychiatric hospitals: Bernburg, Brandenburg, Grafeneck, Hadamar, Hartheim, and Sonnenstein.[33][54] One thousand children under the age of 17 were killed at the institutions Am Spiegelgrund and Gugging in Austria.[55][56] They played a crucial role in developments leading to the Holocaust.[33] As a related aspect of the "medical" and scientific basis of this programme, the Nazi doctors took thousands of brains from 'euthanasia' victims for research.[57]

From August 1939, the Interior Ministry registered children with disabilities, requiring doctors and midwives to report all cases of newborns with severe disabilities; the 'guardian' consent element soon disappeared. Those to be killed were identified as "all children under three years of age in whom any of the following 'serious hereditary diseases' were 'suspected': idiocy and Down syndrome (especially when associated with blindness and deafness); microcephaly; hydrocephaly; malformations of all kinds, especially of limbs, head, and spinal column; and paralysis, including spastic conditions".[58] The reports were assessed by a panel of medical experts, of whom three were required to give their approval before a child could be killed.[g]

The Ministry used deceit when dealing with parents or guardians, particularly in Catholic areas, where parents were generally uncooperative. Parents were told that their children were being sent to "Special Sections", where they would receive improved treatment.[59] The children sent to these centres were kept for "assessment" for a few weeks and then killed by injection of toxic chemicals, typically phenol; their deaths were recorded as "pneumonia". Autopsies were usually performed and brain samples were taken to be used for "medical research". Post mortem examinations apparently helped to ease the consciences of many of those involved, giving them the feeling that there was a genuine medical purpose to the killings.[60]

The most notorious of these institutions in Austria was Am Spiegelgrund, where from 1940 to 1945, 789 children were killed by lethal injection, gas poisoning and physical abuse.[61] Children's brains were preserved in jars of formaldehyde and stored in the basement of the clinic and in the private collection of Heinrich Gross, one of the institution's directors, until 2001.[56]

When the Second World War began in September 1939, less rigorous standards of assessment and a quicker approval process were adopted. Older children and adolescents were included and the conditions covered came to include

... various borderline or limited impairments in children of different ages, culminating in the killing of those designated as juvenile delinquents. Jewish children could be placed in the net primarily because they were Jewish; and at one of the institutions, a special department was set up for 'minor Jewish-Aryan half-breeds'.

— Lifton[62]

More pressure was placed on parents to agree to their children being sent away. Many parents suspected what was happening and refused consent, especially when it became apparent that institutions for children with disabilities were being systematically cleared of their charges. The parents were warned that they could lose custody of all their children and if that did not suffice, the parents could be threatened with call-up for 'labour duty'.[63] By 1941, more than 5,000 children had been killed.[42][h] The last child to be killed under Aktion T4 was Richard Jenne on 29 May 1945, in the children's ward of the Kaufbeuren-Irsee state hospital in Bavaria, Germany, more than three weeks after US Army troops had occupied the town.[64][65]

Killing of adults

[edit]Invasion of Poland

[edit]

Brandt and Bouhler developed plans to expand the programme of euthanasia to adults. In July 1939 they held a meeting attended by Conti and Professor Werner Heyde, head of the SS medical department. This meeting agreed to arrange a national register of all institutionalised people with mental illnesses or physical disabilities. The first adults with disabilities to be killed en masse by the Nazi regime were Poles. After the invasion on 1 September 1939, adults with disabilities were shot by the SS men of Einsatzkommando 16, Selbstschutz and EK-Einmann under the command of SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Tröger, overseen by Reinhard Heydrich, during Operation Tannenberg.[66][i]

All hospitals and mental asylums of the Wartheland were emptied. The region was incorporated into Germany and earmarked for resettlement by Volksdeutsche following the German conquest of Poland.[68] In the Danzig (now Gdańsk) area, some 7,000 Polish patients of institutions were shot. 10,000 were killed in the Gdynia area. Similar measures were taken in other areas of Poland destined for incorporation into Germany.[69]

In October 1939, the first experiments with the gassing of patients were conducted at Fort VII in Posen (occupied Poznań), where hundreds of prisoners were killed by means of carbon monoxide poisoning, in an improvised gas chamber developed by Albert Widmann, chief chemist of the German Criminal Police (Kripo). In December 1939, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler witnessed one of these gassings, ensuring that this invention would later be put to much wider uses.[70]

The idea of killing adult mental patients soon spread from occupied Poland to adjoining areas of Germany, probably because Nazi Party and SS officers in these areas were most familiar with what was happening in Poland. These were the areas where Germans wounded from the Polish campaign were expected to be accommodated, which created a demand for hospital space. The Gauleiter of Pomerania, Franz Schwede-Coburg, sent 1,400 patients from five Pomeranian hospitals to undisclosed locations in occupied Poland, where they were shot. The Gauleiter of East Prussia, Erich Koch, had 1,600 patients killed out of sight. More than 8,000 Germans were killed in this initial wave of killings carried out on the orders of local officials, although Himmler certainly knew and approved of them.[42][71]

The legal basis for the programme was a 1939 letter from Hitler, not a formal "Führer's decree" with the force of law. Hitler bypassed Conti, the Health Minister and his department, who might have raised questions about the legality of the programme and entrusted it to Bouhler and Brandt.[72][j]

Reich Leader Bouhler and Dr. Brandt are entrusted with the responsibility of extending the authority of physicians, to be designated by name, so that patients who, after a most critical diagnosis, on the basis of human judgment [menschlichem Ermessen], are considered incurable, can be granted mercy death [Gnadentod].

The killings were administered by Viktor Brack and his staff from Tiergartenstraße 4, disguised as the "Charitable Foundation for Cure and Institutional Care" offices which served as the front and was supervised by Bouhler and Brandt.[73][74] The officials in charge included Herbert Linden, who had been involved in the child killing programme; Ernst-Robert Grawitz, chief physician of the SS and August Becker, an SS chemist. The officials selected the doctors who were to carry out the operational part of the programme; based on political reliability as long-term Nazis, professional reputation and sympathy for radical eugenics.[75]

The list included physicians who had proved their worth in the child-killing programme, such as Unger, Heinze and Hermann Pfannmüller. The recruits were mostly psychiatrists, notably Professor Carl Schneider of Heidelberg, Professor Max de Crinis of Berlin and Professor Paul Nitsche from the Sonnenstein state institution. Heyde became the operational leader of the programme, succeeded later by Nitsche.[75]

Listing of targets from hospital records

[edit]

In early October, all hospitals, nursing homes, old-age homes and sanatoria were required to report all patients who had been institutionalised for five years or more, who had been committed as "criminally insane", who were of "non-Aryan race" or who had been diagnosed with any on a list of conditions. The conditions included schizophrenia, epilepsy, Huntington's chorea, advanced syphilis, senile dementia, paralysis, encephalitis and "terminal neurological conditions generally".[76]

Many doctors and administrators assumed that the reports were to identify inmates who were capable of being drafted for "labour service" and tended to overstate the degree of incapacity of their patients, to protect them from labour conscription. When some institutions refused to co-operate, teams of T4 doctors, or Nazi medical students, visited and compiled the lists, sometimes in a haphazard and ideologically motivated way.[76] In 1940, all Jewish patients were removed from institutions and killed.[77][78][79][k]

As with child inmates, adults were assessed by a panel of experts, working at the Tiergartenstraße offices. The experts were required to make their judgements on the reports, not medical histories or examinations. Sometimes they dealt with hundreds of reports at a time. On each they marked a + (death), a - (life), or occasionally a ? meaning that they were unable to decide. Three "death" verdicts condemned the person and as with reviews of children, the process became less rigorous, the range of conditions considered "unsustainable" grew broader and zealous Nazis further down the chain of command increasingly made decisions on their own initiative.[80]

Gassing

[edit]The first gassings in Germany proper took place in January 1940 at the Brandenburg Euthanasia Centre. The operation was headed by Brack, who said "the needle belongs in the hand of the doctor".[81] Bottled pure carbon monoxide gas was used. At trials, Brandt described the process as a "major advance in medical history".[82] Once the efficacy of the method was confirmed, it became standard and was instituted at a number of centres in Germany under the supervision of Widmann, Becker and Christian Wirth – a Kripo officer who later played a prominent role in the Final Solution (extermination of Jews) as commandant of newly built death camps in occupied Poland.

In addition to Brandenburg, the killing centres included Grafeneck Castle in Baden-Württemberg (10,824 dead), Schloss Hartheim near Linz in Austria (over 18,000 dead), Sonnenstein in Saxony (15,000 dead), Bernburg in Saxony-Anhalt and Hadamar in Hesse (14,494 dead). The same facilities were also used to kill mentally sound prisoners transferred from concentration camps in Germany, Austria and occupied parts of Poland.

Condemned patients were transferred from their institutions to new centres in T4 Charitable Ambulance buses, called the Community Patients Transports Service. They were run by teams of SS men wearing white coats, to give it an air of medical care.[83] To prevent the families and doctors of the patients from tracing them, the patients were often first sent to transit centres in major hospitals, where they were supposedly assessed. They were moved again to special treatment (Sonderbehandlung) centres. Families were sent letters explaining that owing to wartime regulations, it was not possible for them to visit relatives in these centres.[84]

Most of these patients were killed within 24 hours of arriving at the centres and their bodies cremated.[84] Some bodies were dissected for medical research whilst others had their gold teeth extracted.[85] For every person killed, a death certificate was prepared, giving a false but plausible cause of death. This was sent to the family along with an urn of ashes (random ashes, since the victims were cremated en masse). The preparation of thousands of falsified death certificates took up most of the working day of the doctors who operated the centres.[86]

During 1940, the centres at Brandenburg, Grafeneck and Hartheim killed nearly 10,000 people each, while another 6,000 were killed at Sonnenstein. In all, about 35,000 people were killed in T4 operations that year. Operations at Brandenburg and Grafeneck were wound up at the end of the year, partly because the areas they served had been cleared and partly because of public opposition. In 1941, however, the centres at Bernburg and Sonnenstein increased their operations, while Hartheim (where Wirth and Franz Stangl were successively commandants) continued as before. Another 35,000 people were killed before August 1941, when the T4 programme was officially shut down by Hitler. Even after that date the centres continued to be used to kill concentration camp inmates: eventually some 20,000 people in this category were killed.[l]

In 1971, Gitta Sereny conducted interviews with Stangl, who was in prison in Düsseldorf, having been convicted of co-responsibility for killing 900,000 people, while commandant of the Sobibor and Treblinka extermination camps in Poland. Stangl gave Sereny a detailed account of the operations of the T4 programme based on his time as commandant of the killing facility at the Hartheim institute.[88] He described how the inmates of asylums were removed and transported by bus to Hartheim. Some were in no mental state to know what was happening to them but many were perfectly sane and for them forms of deception were used. They were told they were at a special clinic where they would receive improved treatment and were given a brief medical examination on arrival. They were induced to enter what appeared to be a shower block, where they were gassed with carbon monoxide. The ruse was also used at extermination camps.[88] Some of the victims knew their fate and tried to defend themselves.[85]

Number of euthanasia victims

[edit]The SS functionaries and hospital staff associated with Aktion T4 in the German Reich were paid from the central office at Tiergartenstraße 4 in Berlin from the spring of 1940. The SS and police from SS-Sonderkommando Lange responsible for murdering the majority of patients in the annexed territories of Poland since October 1939, took their salaries from the normal police fund, supervised by the administration of the newly formed Wartheland district. The programme in Germany and occupied Poland was overseen by Heinrich Himmler.[89]

Before 2013, it was believed that 70,000 persons were murdered in the euthanasia programme, but the German Federal Archives reported that research in the archives of former East Germany indicated that the number of victims in Germany and Austria from 1939 to 1945 was about 200,000 persons and that another 100,000 persons were victims in other European countries.[20][90] In the German T4 centres there was at least the semblance of legality in keeping records and writing letters. In Polish psychiatric hospitals no one was left behind. Killings were inflicted using gas-vans, sealed army bunkers and machine guns; families were not informed about the murdered relatives and the empty wards were handed over to the SS.[89]

| T4 Center | Period | 1940 | 1941 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grafeneck | 20 Jan – Dec 1940 | 9,839 | — | 9,839 | |

| Brandenburg | 8 Feb – Oct 1940 | 9,772 | — | 9,772 | |

| Bernburg | 21 November 1940 – 30 July 1943 | — | 8,601 | 8,601 | |

| Hartheim | 6 May 1940 – Dec 1944 | 9,670 | 8,599 | 18,269 | |

| Sonnenstein | Jun 1940 – Sep 1942 | 5,943 | 7,777 | 13,720 | |

| Hadamar | Jan 1941 – 31 July 1942 | — | 10,072 | 10,072 | |

| Total by year[91] | 35,224 | 35,049 | 70,273 | ||

| In hospitals in occupied Poland[89] | |||||

| Owińska | Oct 1939 | 1,100 | |||

| Kościan | Nov 1939 – Mar 1940[92] | (2,750) 3,282 | |||

| Świecie | Oct–Nov 1939[93] | 1,350 | |||

| Kocborowo | 22 September 1939 – Jan 1940 (1941–44)[92] |

2,562 (1,692) | |||

| Dziekanka | 7 December 1939 – 12 January 1940 (Jul 1941)[92] |

1,201 (1,043) | |||

| Chełm | 12 January 1940 | 440 | |||

| Warta | 31 March 1940 (16 Jun 1941)[92] |

581 (499) | |||

| Działdowo | 21 May – 8 July 1940 | 1,858 | |||

| Kochanówka | 13 March 1940 – Aug 1941 | (minimum of) 850 | |||

| Helenówek (et al.) | 1940–1941 | 2,200–2,300 | |||

| Lubliniec | Nov 1941 | (children) 194 | |||

| Choroszcz | Aug 1941 | 700 | |||

| Rybnik | 1940–1945[92] | 2,000 | |||

| Total by number[92] | c. 16,153 | ||||

Technology and personnel transfer to death camps

[edit]After the official end of the euthanasia programme in 1941, most of the personnel and high-ranking officials, as well as gassing technology and the techniques used to deceive victims, were transferred under the jurisdiction of the national medical division of the Reich Interior Ministry. Further gassing experiments with the use of mobile gas chambers (Einsatzwagen) were conducted at Soldau concentration camp by Herbert Lange following Operation Barbarossa. Lange was appointed commander of the Chełmno extermination camp in December 1941. He was given three gas vans by the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), converted by the Gaubschat GmbH in Berlin[94] and before February 1942, killed 3,830 Polish Jews and around 4,000 Romani, under the guise of "resettlement".[95]

After the Wannsee conference, implementation of gassing technology was accelerated by Heydrich. Beginning in the spring of 1942, three killing factories were built secretly in east-central Poland. The SS officers responsible for the earlier Aktion T4, including Wirth, Stangl and Irmfried Eberl, had important roles in the implementation of the "Final Solution" for the next two years.[96][m] The first killing centre, equipped with stationary gas chambers, modelled on technology developed under Aktion T4, was established at Bełżec in the General Government territory of occupied Poland; the decision preceded the Wannsee Conference of January 1942 by three months.[97]

Opposition

[edit]

In January 1939, Brack commissioned a paper from Professor of Moral Theology at the University of Paderborn, Joseph Mayer, on the likely reactions of the churches in the event of a state euthanasia programme being instituted. Mayer – a longstanding euthanasia advocate – reported that the churches would not oppose such a programme if it was seen to be in the national interest. Brack showed this paper to Hitler in July and it may have increased his confidence that the "euthanasia" programme would be acceptable to German public opinion.[52] Notably, when Sereny interviewed Mayer shortly before his death in 1967, he denied that he formally condoned the killing of people with disabilities but no copies of this paper are known to survive.[98]

Some bureaucrats opposed the T4 programme; Lothar Kreyssig, a district judge and member of the Confessing Church, wrote to Justice Minister Franz Gürtner protesting that the action was illegal since no law or formal decree from Hitler had authorised it. Gürtner replied, "If you cannot recognise the will of the Führer as a source of law, then you cannot remain a judge" and had Kreyssig dismissed.[48]

Hitler had a policy of not issuing written instructions for matters which could later be condemned by the international community, but made an exception when he provided Bouhler and Brack with written authority for the T4 programme. Hitler wrote a confidential letter in October 1939 to overcome opposition within the German state bureaucracy. Hitler told Bouhler that, "the Führer's Chancellery must under no circumstances be seen to be active in this matter".[73] Gürtner had to be shown Hitler's letter in August 1940 to gain his co-operation.[74]

Exposure

[edit]In the towns where the killing centres were located, some people saw the inmates arrive in buses, saw smoke from the crematoria chimneys and noticed that the buses were returning empty. In Hadamar, ashes containing human hair rained down on the town and despite the strictest orders, some of the staff at the killing centres talked about what was going on. In some cases families could tell that the causes of death in certificates were false, e.g. when a patient was claimed to have died of appendicitis, even though his appendix had been removed some years earlier. In other cases, families in the same town would receive death certificates on the same day.[99] In May 1941, the Frankfurt County Court wrote to Gürtner describing scenes in Hadamar, where children shouted in the streets that people were being taken away in buses to be gassed.[100]

During 1940, rumours of what was taking place spread and many Germans withdrew their relatives from asylums and sanatoria to care for them at home, often with great expense and difficulty. In some places doctors and psychiatrists co-operated with families to have patients discharged or if the families could afford it, transferred them to private clinics beyond the reach of T4. Other doctors "re-diagnosed" patients so that they no longer met the T4 criteria, which risked exposure when Nazi zealots from Berlin conducted inspections. In Kiel, Professor Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt managed to save nearly all of his patients.[101] Lifton listed a handful of psychiatrists and administrators who opposed the killings; many doctors collaborated, either through ignorance, agreement with Nazi eugenicist policies or fear of the regime.[101]

Protest letters were sent to the Reich Chancellery and the Ministry of Justice, some from Nazi Party members. The first open protest against the removal of people from asylums took place at Absberg in Franconia in February 1941 and others followed. The SD report on the incident at Absberg noted that "the removal of residents from the Ottilien Home has caused a great deal of unpleasantness" and described large crowds of Catholic townspeople, among them Party members, protesting against the action.[102]

Similar petitions and protests occurred throughout Austria as rumours spread of mass killings at the Hartheim Euthanasia Centre and of mysterious deaths at the children's clinic, Am Spiegelgrund in Vienna. Anna Wödl, a nurse and mother of a child with a disability, vehemently petitioned to Hermann Linden at the Reich Ministry of the Interior in Berlin to prevent her son, Alfred, from being transferred from Gugging, where he lived and which also became a euthanasia center. Wödl failed and Alfred was sent to Am Spiegelgrund, where he was killed on 22 February 1941. His brain was preserved in formaldehyde for "research" and stored in the clinic for sixty years.[103]

Church protests

[edit]The Lutheran theologian Friedrich von Bodelschwingh (director of the Bethel Institution for Epilepsy at Bielefeld) and Pastor Paul-Gerhard Braune (director of the Hoffnungstal Institution near Berlin) protested. Bodelschwingh negotiated directly with Brandt and indirectly with Hermann Göring, whose cousin was a prominent psychiatrist. Braune had meetings with Gürtner, who was always dubious about the legality of the programme. Gürtner later wrote a strongly worded letter to Hitler protesting against it; Hitler did not read it but was told about it by Lammers.[104]

Bishop Theophil Wurm, presiding over the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Württemberg, wrote to Interior Minister Frick in March 1940 "denouncing the policy"; that month a confidential report from the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) in Austria, warned that the killing programme must be implemented with stealth "...to avoid a probable backlash of public opinion during the war".[11][105] On 4 December 1940, Reinhold Sautter, the Supreme Church Councillor of the Württemberg State Church, complained to the Nazi Ministerial Councillor Eugen Stähle against the murders in Grafeneck Castle. Stähle said "The fifth commandment Thou shalt not kill, is no commandment of God but a Jewish invention".[106]

Bishop Heinrich Wienken of Berlin, a leading member of the Caritas Association, was selected by the Fulda episcopal synod to represent the views of the Catholic Church in meetings with T4 operatives. In 2008, Michael Burleigh wrote

Wienken seems to have gone partially native in the sense that he gradually abandoned an absolute stance based on the Fifth Commandment in favour of winning limited concessions regarding the restriction of killing to 'complete idiots', access to the sacraments and the exclusion of ill Roman Catholic priests from these policies.[107]

Despite a decree issued by the Vatican on 2 December 1940 stating that the T4 policy was "against natural and positive Divine law" and that "The direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed", the Catholic Church hierarchy in Germany decided to take no further action. Incensed by the Nazi appropriation of Church property in Münster to accommodate people made homeless by an air raid, in July and August 1941, the bishop of Münster, Clemens August Graf von Galen, gave four sermons criticising the Nazis for arresting Jesuits, confiscating church property and for the euthanasia program.[108][109] Galen sent the text to Hitler by telegram, calling on

... the Führer to defend the people against the Gestapo. It is a terrible, unjust and catastrophic thing when man opposes his will to the will of God ... We are talking about men and women, our compatriots, our brothers and sisters. Poor unproductive people if you wish, but does this mean that they have lost their right to live?[110]

Galen's sermons were not reported in the German press but were circulated illegally in leaflets. The text was dropped by the Royal Air Force over German troops.[111][112] In 2009, Richard J. Evans wrote that "This was the strongest, most explicit and most widespread protest movement against any policy since the beginning of the Third Reich".[13] Local Nazis asked for Galen to be arrested but Goebbels told Hitler that such action would provoke a revolt in Westphalia and Hitler decided to wait until after the war to take revenge.[113][111]

In 1986, Lifton wrote, "Nazi leaders faced the prospect of either having to imprison prominent, highly admired clergymen and other protesters – a course with consequences in terms of adverse public reaction they greatly feared – or else end the programme".[114] Evans considered it "at least possible, even indeed probable" that the T4 programme would have continued beyond Hitler's initial quota of 70,000 deaths but for the public reaction to Galen's sermon.[115] Burleigh called assumptions that the sermon affected Hitler's decision to suspend the T4 programme "wishful thinking" and noted that the various Church hierarchies did not complain after the transfer of T4 personnel to Aktion Reinhard.[116]

British historian Alec Ryrie wrote that "Braune, von Bodelschwingh, Kreyssig, Wurn, von Galen, and others had demonstrated that when a broad enough swatch of Germany's Christians took a stand, it was possible to save lives."[11] On the other hand, Henry Friedlander wrote that it was not the criticism from the Church but rather the loss of secrecy and "general popular disquiet about the way euthanasia was implemented" that caused the killings to be suspended.[117]

Galen had detailed knowledge of the euthanasia programme by July 1940 but did not speak out until almost a year after Protestants had begun to protest. In 2002, Beth A. Griech-Polelle wrote:

Worried lest they be classified as outsiders or internal enemies, they waited for Protestants, that is the "true Germans", to risk a confrontation with the government first. If the Protestants were able to be critical of a Nazi policy, then Catholics could function as "good" Germans and yet be critical too.[118]

On 29 June 1943, Pope Pius XII issued the encyclical Mystici corporis Christi, in which he condemned the fact that "physically deformed people, mentally disturbed people and hereditarily ill people have at times been robbed of their lives" in Germany. Following this, in September 1943, a bold but ineffectual condemnation was read by bishops from pulpits across Germany, denouncing the killing of "the innocent and defenceless mentally handicapped and mentally ill, the incurably infirm and fatally wounded, innocent hostages and disarmed prisoners of war and criminal offenders, people of a foreign race or descent".[119]

Suspension and continuity

[edit]

On 24 August 1941, Hitler ordered the suspension of the T4 killings. After the invasion of the Soviet Union in June, many T4 personnel were transferred to the eastern front. The projected death total for the T4 programme of 70,000 deaths had been reached by August 1941.[120] The termination of the T4 programme did not end the killing of people with disabilities; from the end of 1941, on the initiative of institute directors and local party leaders, the killing of adults and children continued, albeit less systematically, until the end of the war.[121]

After the bombing of Hamburg in July 1943, occupants of old age homes were killed. In the post-war trial of Dr. Hilda Wernicke, Berlin, August 1946, testimony was given that "500 old, broken women" who had survived the bombing of Stettin in June 1944 were euthanised at the Meseritz-Oberwalde Asylum.[121] The Hartheim, Bernberg, Sonnenstein and Hadamar centres continued in use as "wild euthanasia" centres to kill people sent from all over Germany, until 1945.[120] The methods were lethal injection or starvation, those employed before use of gas chambers.[122]

By the end of 1941, about 100,000 people had been killed in the T4 programme.[123] From mid-1941, concentration camp prisoners too feeble or too much trouble to keep alive were murdered after a cursory psychiatric examination under Action 14f13.[124]

Post-war

[edit]Doctors' trial

[edit]After the war trials were held in connection with the Nazi euthanasia programme at various places including Dresden, Frankfurt, Graz, Nuremberg and Tübingen. In December 1946 an American military tribunal (commonly called the Doctors' trial) prosecuted 23 doctors and administrators for their roles in war crimes and crimes against humanity. These crimes included the systematic killing of those deemed "unworthy of life", including people with mental disabilities, the people who were institutionalised mentally ill and people with physical impairments. After 140 days of proceedings, including the testimony of 85 witnesses and the submission of 1,500 documents, in August 1947 the court pronounced 16 of the defendants guilty. Seven were sentenced to death; the men, including Brandt and Brack, were executed on 2 June 1948.

The indictment read in part:

14. Between September 1939 and April 1945 the defendants Karl Brandt, Blome, Brack, and Hoven unlawfully, wilfully, and knowingly committed crimes against humanity, as defined by Article II of Control Council Law No. 10, in that they were principals in, accessories to, ordered, abetted, took a consenting part in, and were connected with plans and enterprises involving the execution of the so called "euthanasia" program of the German Reich, in the course of which the defendants herein murdered hundreds of thousands of human beings, including German civilians, as well as civilians of other nations. The particulars concerning such murders are set forth in paragraph 9 of count two of this indictment and are incorporated herein by reference.

— International Military Tribunal[125]

Earlier, in 1945, American forces tried seven staff members of the Hadamar killing centre for the killing of Soviet and Polish nationals, which was within their jurisdiction under international law, as these were the citizens of wartime allies. (Hadamar was within the American Zone of Occupation in Germany. This was before the Allied resolution of December 1945, to prosecute individuals for "crimes against humanity" for such mass atrocities.) Alfons Klein, Heinrich Ruoff and Karl Willig were sentenced to death and executed; the other four were given long prison sentences.[126] In 1946, reconstructed German courts tried members of the Hadamar staff for the murders of nearly 15,000 German citizens. The chief physician, Adolf Wahlmann and Irmgard Huber, the head nurse, were convicted.[citation needed]

Other perpetrators

[edit]

- Dietrich Allers was sentenced to eight years time served in December 1968.[127]

- Hans Asperger was not discovered to be involved in the programme until after his death in 1980.[128]

- Erich Bauer, arrested in 1949 and sentenced to death, which was automatically commuted to life in prison due to West Germany's abolition of capital punishment. He died in prison in 1980.

- August Becker, initially sentenced to three years after the war, in 1960 was tried again and sentenced to ten years in prison. He was released early due to ill health and died in 1967.[129]

- Werner Blankenburg lived under an alias and died in 1957.[130]

- Philipp Bouhler committed suicide in captivity, May 1945.[130]

- Werner Catel was cleared by a denazification board after World War II and was head of paediatrics at the University of Kiel.[131] He retired early after his role in the T4 programme was exposed but continued to support the killing of children with mental and physical disabilities.[132]

- Leonardo Conti hanged himself in captivity on 6 October 1945.[133]

- Professor Max de Crinis took his own life via a cyanide capsule after poisoning his family.

- Fritz Cropp d. 6 April 1984, Bremen. A Nazi official in Oldenburg, Cropp was appointed the country medical officer of health in 1933. In 1935 he transferred to Berlin, where he worked as a ministerial adviser in the Division IV (health care and people care) in the Ministry of the Interior. In 1939, he became assistant director; Cropp was involved in the Nazi "euthanasia" Aktion T4 in 1940. He was Herbert Linden's superior and was responsible for patient transfers.[134]

- Irmfried Eberl captured 1948; killed himself to avoid trial.

- Gottfried von Erdmannsdorff, commander of Fortress Mogilev, where many physically and mentally disabled prisoners were killed; executed by the Soviet Union in 1946.

- Ernst-Robert Grawitz killed himself shortly before the fall of Berlin in April 1945.[135]

- Heinrich Gross was tried twice. One sentence was overturned and the charges in the second trial in 2000 were dropped as a result of his dementia; he died in 2005.[136]

- Lorenz Hackenholt vanished in 1945.[137]

- Hans Heinze was convicted of crimes against humanity for his work at the Brandenburg Euthanasia Centre and served seven years in an NKVD special camp.[138]

- Philipp, Landgrave of Hesse, the governor of Hesse-Nassau, was tried in 1947 at Hadamar for his role in Aktion T4 but was sentenced only to two years' "time served"; he died in 1980.[139]

- Werner Heyde escaped detection for 18 years and took his own life in 1964, before his trial.[124]

- Josef Hirtreiter served time in prison from 1951 to 1977 for gassings of Jews at the Treblinka extermination camp. His involvement at the Hadamar clinic was alleged but could never be proved.[140]

- Ernst Illing was the director of the Vienna Psychiatric-Neurological Clinic for Children Am Spielgrund, where he killed about 200 children; he was sentenced to death on 18 July 1946.[141]

- Erwin Jekelius, former director of Am Spiegelgrund, died in a prison camp in the Soviet Union in 1952.[142]

- Erich Koch served time in prison from 1950 to his death in 1986.[143]

- Erwin Lambert died in 1976.[137]

- Hans Lammers was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment after being convicted in the Ministries Trial. This was later commuted to 10 years and Lammers was released in 1951. He died in 1962.

- Herbert Lange was killed by Allied troops during the Battle of Berlin.

- Herbert Linden took his own life in 1945. Overseers of the programme were initially Herbert Linden and Werner Heyde. Linden was later replaced by Hermann Paul Nitsche.[144]

- Heinrich Matthes was sentenced to life imprisonment at the Treblinka trials.

- Friedrich Mennecke died in 1947 while awaiting trial.[145]

- Franz Niedermoser, chief doctor of the Klagenfurt extermination center, was executed in 1946 after being convicted in the Klagenfurt trial.

- Paul Nitsche was tried and executed by an East German court in 1948.[146]

- Josef Oberhauser served eight years of a 15-year prison sentence for crimes against humanity and was released in 1956. He later received a further four years imprisonment at the Belzec trial for 300,000 counts of acting as an accessory to murder.

- Hermann Pfannmüller served five years in prison as an accessory to murder.

- Franz Reichleitner was killed by Italian partisans in 1944.

- Professor Carl Schneider hanged himself in his prison cell in 1946, while awaiting trial.[147]

- Walter Schultze was sentenced to four years at hard labor in May 1960 for aiding and abetting manslaughter of 380 persons.[148]

- Franz Schwede was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 1948 and was released in 1956; he died in 1960.[149]

- Franz Stangl, after being caught in Brazil in 1967, was sentenced to life imprisonment. He died of heart failure six months into the sentence.

- Rudolf Tröger was killed in action at the Maginot Line.[150]

- Marianne Türk was a doctor at Vienna Psychiatric-Neurological Clinic for Children Am Spielgrund where, with Ernst Illing, she killed 200 children. She was sentenced to 10 years prison on 18 July 1946.[141]

- Reinhold Vorberg was sentenced to ten years time served in December 1968.[127]

- Albert Widmann was convicted in two trials in the 1960s and served six years in prison.

- Christian Wirth was killed by Yugoslav partisans in 1944.

The Stasi (Ministry for State Security) of East Germany stored around 30,000 files of Aktion T4 in their archives. Those files became available to the public after German Reunification in 1990, leading to a new wave of research on these wartime crimes.[151]

Memorials

[edit]The German national memorial to the people with disabilities murdered by the Nazis was dedicated in 2014 in Berlin.[152][153] It is located in the pavement of a site next to the Tiergarten park, the location of the former villa at Tiergartenstraße 4 in Berlin, where more than 60 Nazi bureaucrats and doctors worked in secret under the "T4" programme to organise the mass murder of sanatorium and psychiatric hospital patients deemed unworthy to live.[153]

See also

[edit]- Ableism

- Memorandum Authorizing Involuntary Euthanasia

- Nazi doctors (list)

- Nazi eugenics, the racially based social policies that placed the improvement of the Aryan race at the heart of Nazis ideology.

- Nazi medical experimentation

- Operation Reinhard, men of Aktion T4 provided expertise for building the extermination camps during the Holocaust.

- Aktion 14f13 (1941–44), a Nazi extermination operation that killed prisoners who were sick, elderly, or deemed no longer fit for work

- Racial hygiene

- T4-Gutachter experts selecting victims killed by gas in "euthanasia" centers

- Ich klage an, Nazi pro-euthanasia propaganda film

- Life unworthy of life

Notes

[edit]- ^ As many as 100,000 people may have been killed directly as part of Aktion T4. Mass euthanasia killings were also carried out in the Central and Eastern European countries and territories occupied by Nazi Germany during the war (see Nazi war crimes). Categories are fluid and no definitive figure can be assigned but historians put the total number of victims at around 300,000.[3]

- ^ Tiergartenstraße 4 was the location of the Central Office and administrative headquarters of the Gemeinnützige Stiftung für Heil- und Anstalts- pflege (Charitable Foundation for Curative and Institutional Care).[6]

- ^ Notes on patient records from the archive "R 179" of the Chancellery of the Führer Main Office II b. Between 1939 and 1945, about 200,000 women, men and children in psychiatric institutions of the German Reich were killed in covert actions by gas, medication or starvation. Original: Zwischen 1939 und 1945 wurden ca. 200.000 Frauen, Männer und Kinder aus psychiatrischen Einrichtungen des Deutschen Reichs im mehreren verdeckten Aktionen durch Vergasung, Medikamente oder unzureichende Ernährung ermordet.[9]

- ^ Robert Lifton and Michael Burleigh estimated that twice the official number of T4 victims may have perished before the end of the war.[16][page needed][17] Ryan and Schurman gave an estimated range of 200,000 and 250,000 victims of the policy upon the arrival of Allied troops in Germany.[18]

- ^ This was the result either of club foot or osteomyelitis. Goebbels is commonly said to have had club foot (talipes equinovarus), a congenital condition. William L. Shirer, who worked in Berlin as a journalist in the 1930s and was acquainted with Goebbels, wrote in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1960) that the deformity was from a childhood attack of osteomyelitis and a failed operation to correct it.[30]

- ^ Robert Lifton wrote that this request was "encouraged"; the severely disabled child and the agreement of the parents to his killing were apparently genuine.[37]

- ^ Professors Werner Catel (a Leipzig psychiatrist) and Hans Heinze, head of a state institution for children with intellectual disabilities at Görden near Brandenburg; Ernst Wentzler a Berlin paediatric psychiatrist and the author Dr. Helmut Unger.[58]

- ^ Lifton concurs with this figure, but notes that the killing of children continued after the T4 programme was formally ended in 1941.[63]

- ^ The second phase of Operation Tannenberg referred to as the Unternehmen Tannenberg by Heydrich's Sonderreferat{ began in late 1939 under the codename Intelligenzaktion and lasted until January 1940, in which 36,000–42,000 people, including Polish children, were killed in Pomerania before the end of 1939.[67]

- ^ Several drafts of a formal euthanasia law were prepared but Hitler refused to authorise them. The senior participants in the programme always knew that it was not a law, even by the loose definition of legality prevailing in Nazi Germany.[72]

- ^ According to Lifton, most Jewish inmates of German mental institutions were dispatched to Lublin in Poland in 1940 and killed there.[79]

- ^ These figures come from the article Aktion T4 on the German Wikipedia, which cites Ernst Klee.[87]

- ^ Role of T4 "Inspector" Christian Wirth in the Holocaust.[96]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Exhibition catalogue in German and English" (PDF). Berlin, Germany: Memorial for the Victims of National Socialist ›Euthanasia‹ Killings. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Euthanasia Program" (PDF). Yad Vashem. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ a b Chase, Jefferson (26 January 2017). "Remembering the 'forgotten victims' of Nazi 'euthanasia' murders". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Sandner 1999, p. 385.

- ^ Hojan & Munro 2015; Bialas & Fritze 2014, pp. 263, 281; Sereny 1983, p. 48.

- ^ Sereny 1983, p. 48.

- ^ Proctor 1988, p. 177.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 477; Browning 2005, p. 193; Proctor 1988, p. 191.

- ^ a b GFE 2013.

- ^ Evans 2009, p. 107; Burleigh 2008, p. 262.

- ^ a b c d Ryrie, Alec (3 April 2018). Protestants: The Faith That Made the Modern World. Penguin. p. 288-289. ISBN 978-0-7352-2282-3.

- ^ McKale, Donald M. (17 March 2006). Hitler's Shadow War: The Holocaust and World War II. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-4616-3547-5.

- ^ a b Evans 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Burleigh & Wippermann 2014; Adams 1990, pp. 40, 84, 191.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 142; Ryan & Schuchman 2002, pp. 25, 62.

- ^ Burleigh 1995.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 142.

- ^ Ryan & Schuchman 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Lifton 2000, p. 102.

- ^ a b "Sources on the History of the "Euthanasia" crimes 1939–1945 in German and Austrian Archives" [Quellen zur Geschichte der "Euthanasie"-Verbrechen 1939–1945 in deutschen und österreichischen Archiven] (PDF). Bundesarchiv. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Hansen & King 2013, p. 141.

- ^ Hitler, p. 447.

- ^ Padfield 1990, p. 260.

- ^ Evans 2005, pp. 507–508.

- ^ "Forced Sterilization". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Engstrom, Weber & Burgmair 2006, p. 1710.

- ^ Joseph 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Bleuler 1924, p. 214.

- ^ Read 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Shirer 1991, p. 124.

- ^ Evans 2005, p. 508.

- ^ a b Miller 2006, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Breggin 1993, pp. 133–148.

- ^ Bangen 1992.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2000, p. 256.

- ^ Friedman 2011, p. 146.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 50.

- ^ Schmidt 2007, p. 118.

- ^ Cina & Perper 2012, p. 59.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Proctor 1988, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Browning 2005, p. 190.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, p. 62.

- ^ Baader 2009, pp. 18–27, "Für mich ist die Vorstellung untragbar, dass beste, blühende Jugend an der Front ihr Leben lassen muss, damit verblichene Asoziale und unverantwortliche Antisoziale ein gesichertes Dasein haben.".

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Schmitt 1965, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 47.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2000, p. 254.

- ^ Evans 2005, p. 444.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Browning 2005, p. 185.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2000, p. 259.

- ^ Miller 2006, p. 158.

- ^ Torrey & Yolken 2010, pp. 26–32.

- ^ Local 2014.

- ^ a b Kaelber 2015.

- ^ Weindling 2006, p. 6.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, p. 52.

- ^ Sereny 1983, p. 55.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 60.

- ^ "The war against the "inferior". On the History of Nazi Medicine in Vienna – Chronology". A project by the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 56.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, p. 163.

- ^ Evans 2004, p. 93.

- ^ Semków 2006, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Semków 2006, pp. 42–50.

- ^ Friedlander 1995, p. 87.

- ^ Browning 2005, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Browning 2005, p. 188.

- ^ Kershaw 2000, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Lifton 1986, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Padfield 1990, p. 261.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2000, p. 253.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, p. 64.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Browning 2005, p. 191.

- ^ Padfield 1990, pp. 261, 303.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, p. 77.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 67.

- ^ Annas & Grodin 1992, p. 25.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Burleigh 2000, p. 54.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, p. 71.

- ^ a b Hohendorf, Gerrit (2016). "THE EXTERMINATION OF MENTALLY ILL AND HANDICAPPED PEOPLE UNDER NATIONAL SOCIALIST RULE". Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah. Archived from the original on 15 August 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023 – via SciencesPo.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 74.

- ^ Klee 1983.

- ^ a b Sereny 1983, pp. 41–90.

- ^ a b c Hojan & Munro 2013.

- ^ "Euthanasie«-Morde". Foundation the Monument for the Murdered Jews of Europe. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ a b Klee 1985, p. 232.

- ^ a b c d e f Jaroszewski 1993.

- ^ WNSP State Hospital 2013.

- ^ Beer 2015, pp. 403–417.

- ^ Ringelblum 2013, p. 20.

- ^ a b Sereny 1983, p. 54.

- ^ Joniec 2016, pp. 1–39.

- ^ Sereny 1983, p. 71.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 75.

- ^ Sereny 1983, p. 58.

- ^ a b Lifton 1986, pp. 80, 82.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 90.

- ^ NEP 2017.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Padfield 1990, p. 304.

- ^ Schmuhl 1987, p. 321.

- ^ Burleigh 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Ericksen 2012, p. 111.

- ^ Evans 2009, p. 110.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 93.

- ^ a b Burleigh 2008, p. 262.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 94.

- ^ Kershaw 2000, pp. 427, 429.

- ^ Lifton 1986, p. 95.

- ^ Evans 2009, p. 112.

- ^ Burleigh 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Friedlander 1997, p. 111.

- ^ Griech-Polelle 2002, p. 76.

- ^ Evans 2009, pp. 529–530.

- ^ a b Burleigh 2008, p. 263.

- ^ a b Aly & Chroust 1994, p. 88.

- ^ Lifton 1986, pp. 96–102.

- ^ Hilberg 2003, p. 1,066.

- ^ a b Hilberg 2003, p. 932.

- ^ Taylor 1949.

- ^ NARA 1980, pp. 1–12.

- ^ a b Ernst Klee: What They Did – What They Became. Doctors, lawyers and other participants in the murder of the sick or Jews, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 75

- ^ Baron-Cohen, Simon (2018). "The truth about Hans Asperger's Nazi collusion". Nature. 557 (7705): 305–306. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..305B. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05112-1. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 13700224. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Trauriges Bild" [Sad Image]. Der Spiegel (in German). Vol. L. 4 December 1967. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ a b Hilberg 2003, p. 1,175.

- ^ "Ins NS-Euthanasieprogramm verstrickt: Der Mediziner Werner Catel (Stellungnahme des Senats vom 14.11.2006)" [Enmeshed in the Nazi Euthanasia Program: The Physician Werner Catel (Statement of the Senate from 14 November 2006)]. University of Kiel (in German). 14 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Werner Catel (1894–1981)". Memorial and Information Point for the Victims of the National Socialist 'Euthanasia' Killings. 10 August 2017. Archived from the original on 25 August 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Hilberg 2003, p. 1,176.

- ^ Hilberg 2003, p. 1,003.

- ^ Hilberg 2003, p. 1,179.

- ^ Martens, D. (2004). "Unfit to live". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 171 (6): 619–620. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1041335. PMC 516202.

- ^ a b Berenbaum & Peck 2002, p. 247.

- ^ "p. 17, Ernst Klee: "Was sie taten – Was sie wurden", p. 136". Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ^ Petropoulos 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Bryant, Michael (2014). Eyewitness to Genocide: The Operation Reinhard Death Camp Trials, 1955-1966. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1621900498.

- ^ a b Totten & Parsons 2009, p. 181.

- ^ "Euthanasia"

- ^ Hilberg 2003, p. 1,182.

- ^ Sandner 2003, p. 395.

- ^ Chroust 1988, p. 8.

- ^ Böhm, B. (2012). "Paul Nitsche – Reformpsychiater und Hauptakteur der NS-"Euthanasie"". Der Nervenarzt. 83 (3): 293–302. doi:10.1007/s00115-011-3389-1. PMID 22399059. S2CID 32985121.

- ^ L Singer (3 December 1998). "Ideology and ethics. The perversion of German psychiatrists' ethics by the ideology of national socialism". European Psychiatry. 13 (Supplement 3): 87s – 92s. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(98)80038-2. PMID 19698678. S2CID 206095914.

Carl Schneider committed suicide by hanging after his arrest...

(subscription required) - ^ "Nazi Official Gets Four Years for Murder Role". New York Herald Tribune (European Edition). 11 May 1960. p. 3.

- ^ Nöth 2004, p. 82.

- ^ Carsten Schreiber: Hidden elite - ideology and regional rule practice of the security service of the SS and its network using the example of Saxony, Munich 2008, p. 401f.

- ^ Buttlar 2003.

- ^ ABC News. "International News – World News – ABC News". ABC News.

- ^ a b "Berlin Dedicates Holocaust Memorial for Disabled". Israel National News. AFP. 2 September 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

References

[edit]Books

- Adams, Mark B. (1990). The Wellborn Science: Eugenics in Germany, France, Brazil and Russia. Monographs on the History and Philosophy of Biology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505361-6.

- Aly, Gotz; Chroust, Peter (1994). Cleansing the Fatherland [Contributions to National Socialist Health and Social Policy] (Edited translations of articles originally published in the journal Beiträge zur Nationalsozialistischen Gesundheits - und Sozial - politik). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4775-2 – via Archive Foundation.

- Annas, George J.; Grodin, Michael A. (1992). The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code: Human Rights in Human Experimentation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977226-1.

- Bangen, Hans (1992). Geschichte der medikamentösen Therapie der Schizophrenie [History of Drug Therapy of Schizophrenia]. Berlin: VWB Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung. ISBN 3-927408-82-4.

- Berenbaum, Michael; Peck, Abraham J. (2002). The Holocaust and History: The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed and the Re-examined. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21529-1.

- Bialas, Wolfgang; Fritze, Lothar (2015). Nazi Ideology and Ethics. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-4438-5881-6.

- Bleuler, E. (1924). Textbook of Psychiatry [Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie]. Translated by Brill, A. A. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 3755976.

- Browning, Christopher (2005). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Arrow. ISBN 978-0-8032-5979-9.

- Burleigh, Michael (1995). Death and Deliverance: 'Euthanasia' in Germany 1900–1945. New York: Verlag Klemm & Oelschläger. ISBN 978-0-521-47769-7.

- Burleigh, Michael (2000). "Psychiatry, German Society and the Nazi "Euthanasia" Programme". In Bartov, Omer (ed.). The Holocaust Origins, Implementation, Aftermath. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15036-1.

- Chroust, Peter, ed. (1988). Friedrich Mennecke. Innenansichten eines medizinischen Täters im Nationalsozialismus. Eine Edition seiner Briefe 1935–1947 [Friedrich Mennecke. Interior Views of a Medical Offender in National Socialism: An Edition of his Letters 1935–1947]. Hamburger Instituts für Sozialforschung. ISBN 978-3-926736-01-7.

- Cina, Stephen J.; Perper, Joshua A. (2010). When Doctors Kill: Who, Why, and How (online ed.). New York: Copernicus Books. ISBN 978-1-4419-1369-2.

- Ericksen, Robert P. (2012). Complicity in the Holocaust: Churches and Universities in Nazi Germany (online ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139059602. ISBN 978-1-280-87907-4.

- Evans, Suzanne E. (2004). Forgotten Crimes: The Holocaust and People with Disabilities. Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-56663-565-3.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9649-4.

- Evans, Richard J. (2009). The Third Reich at War. New York City: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59420-206-3 – via Archive Foundation.

- Friedlander, Henry (1995). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2208-1.

- Friedlander, Henry (1 September 1997). The Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4675-9.

- Friedman, Jonathan C. (2011). The Routledge History of the Holocaust. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-83744-3.

- "Euthanasie im Dritten Reich" [Euthanasia in the Third Reich]. Bundesarchiv (in German). German Federal Archive. 2013. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Griech-Polelle, Beth A. (2002). Bishop von Galen: German Catholicism and National Socialism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13197-0.

- Hansen, Randall; King, Desmond S. (2013). Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race and the Population Scare in Twentieth-Century North America (Cambridge Books Online ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139507554. ISBN 978-1-139-50755-4.

- Hilberg, R. (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews. Vol. III (3rd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09557-9.

- Hitler, A. Mein Kampf [My Struggle] (in German).

- Jaroszewski, Zdzisław (1993). Ermordung der Geisteskranken in Polen 1939-1945. PWN. ISBN 978-8-30-111174-8.

- Joniec, Jarosław (2016). Historia Niemieckiego Obozu Zagłady w Bełżcu [History of the Belzec Extermination Camp] (in Polish). Lublin: Muzeum – Miejsce Pamięci w Bełżcu (National Bełżec Museum & Monument of Martyrology). ISBN 978-83-62816-27-9. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Joseph, Jay (2004). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology under the Microscope. New York: Algora. ISBN 978-0-87586-344-3.

- Kershaw, Ian (2000). Hitler: 1936–1945 Nemesis. Vol. II. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32252-1.

- Klee, Ernst (1983). Euthanasie im NS-Staat. Die Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens [Euthanasia in the NS State: The Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life] (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-596-24326-6.

- Klee, Ernst (1985). Dokumente zur Euthanasie [Documents on Euthanasia] (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-596-24327-3 – via Archive Foundation.

- Lifton, R. J. (1986). The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04904-2 – via Archive Foundation.

- Lifton, R. J. (2000). The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04905-9 – via Archive Foundation.

- Longerich, P. (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Miller, Michael (2006). Leaders of the SS and German Police. Vol. I. San Jose, CA: R. James Bender. ISBN 978-93-297-0037-2.

- Nöth, Stefan (1 May 2004). "Antisemitismus". Voraus zur Unzeit. Coburg und der Aufstieg des Nationalsozialismus in Deutschland [Ahead at an Inopportune Moment. Coburg and the Rise of the National Socialism in Germany] (in German). Initiative Stadtmuseum Coburg. ISBN 978-3-9808006-3-1.

- Padfield, Peter (1990). Himmler: Reichsführer-SS. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-40437-9.

- Petropoulos, Jonathan (2009). Royals and the Reich: The Princes von Hessen in Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921278-1.

- Proctor, Robert N. (1988). Racial Hygiene: Medicine under the Nazis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard College. ISBN 978-0-674-74578-0 – via Archive Foundation.

- Read, J. (2004). "Genetics, Eugenics and Mass Murder". In Read, J.; Mosher, R. L.; Bentall, R. P. (eds.). Models of Madness: Psychological, Social and Biological Approaches to Schizophrenia. ISPD book. Hove, East Sussex: Brunner-Routledge. ISBN 978-1-58391-905-7.

- Ringelblum Archives of the Holocaust: Introduction (PDF). Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. 2013. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Ryan, Donna F.; Schuchman, John S. (2002). "Part I: Targetting the "Unfit" and Radical Public Health Strategies in Nazi Germany". Racial Hygiene: Deaf People in Hitler's Europe. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 978-1-56368-132-5 – via Archive Foundation.

- Sandner, Peter (2003). Verwaltung des Krankenmordes [Administration of Suicides]. Historische Schriftenreihe Des Landeswohlfahrtsverbandes Hes (in German). Vol. II. Gießen: Psychosozial. ISBN 978-3-89806-320-3.

- Schmidt, Ulf (2007). Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84725-031-5 – via Archive Foundation.

- Schmitt, Gerhard (1965). Selektion in der Heilanstalt 1939–1945 [Selection in the Sanatorium 1939–1945]. Stuttgart: Evangelisches Verlagsanstalt. OCLC 923376286.

- Schmuhl, Hans-Walter (1987). Rassenhygiene, Nationalsozialismus, Euthanasie: Von der Verhütung zur Vernichtung "lebensunwerten Lebens", 1890–1945 [Racial Hygiene, National Socialism, Euthanasia: From Prevention to Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life 1890–1945 [simultaneous PhD University of Bielefeld, Bielefeld 1986 as Die Synthese von Arzt und Henker]]. Kritische Studien zur Geschichtswissenschaft (in German). Vol. 75. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-35737-8.

- Sereny, Gitta (1983). Into that Darkness: An Examination of Conscience. New York, NY: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-71035-8.

- Shirer, William L. (1991) [1960]. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-449-21977-5.

- Taylor, T. (1949). Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals: Under Control Council Law no. 10, Nuernberg, October 1946 – April 1949 (transcription) (United States Holocaust Museum ed.). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. OCLC 504102502. Archived from the original on 4 May 2006 – via Archive Foundation.

- Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S. (2009). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-99084-4.

- Weindling, Paul Julian (2006). Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials: From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-50700-5.

Conferences

- Baader, Gerhard (2009). Psychiatrie im Nationalsozialismus zwischen ökonomischer Rationalität und Patientenmord [Psychiatry in National Socialism: Between Economic Rationality and Patient Murder] (PDF). Geschichte der Psychiatrie: Nationalsocialismus und Holocaust Gedächtnis und Gegenwart (PDF). geschichtederpsychiatrie.at. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

Journals

- Breggin, Peter (1993). "Psychiatry's Role in the Holocaust" (PDF). International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 4 (2): 133–48. doi:10.3233/JRS-1993-4204. PMID 23511221. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2017 – via PDF file direct download, 4.07 MB.

- Burleigh, Michael (2008). "Between Enthusiasm, Compliance and Protest: The Churches, Eugenics and the Nazi 'Euthanasia' Programme". Contemporary European History. 3 (3): 253–264. doi:10.1017/S0960777300000886. ISSN 0960-7773. PMID 11660654. S2CID 6399101.

- Engstrom, E. J.; Weber, M. M.; Burgmair, W. (October 2006). "Emil Wilhelm Magnus Georg Kraepelin (1856–1926)". The American Journal of Psychiatry. British Library Serials. 163 (10): 1710. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.10.1710. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 17012678.

- "History of Świecie Hospital" [Historia szpitala w Świeciu]. Regional State Hospital: Wojewódzki Szpital dla Nerwowo i Psychicznie Chorych, Samorząd Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017.

- Sandner, Peter (July 1999). "Die "Euthanasie"-Akten im Bundesarchiv. Zur Geschichte eines lange verschollenen Bestandes" [The 'Euthanasia' Files in the Federal Archives. On the History of a Long Lost Existence] (PDF). Vierteljahrschefte für Zeitgeschichte – Institut für Zeitgeschichte. 47 (3): 385–400. ISSN 0042-5702. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- Semków, Piotr (September 2006). "Kolebka" [Cradle] (PDF). IPN Bulletin (8–9 (67–68)). 42–50 44–51/152. ISSN 1641-9561. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2015 – via direct download: 3.44 MB.

- Fuller Torrey, Edwin; Yolken, Robert (January 2010). "Psychiatric Genocide: Nazi Attempts to Eradicate Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp097. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 2800142. PMID 19759092.

Newspapers

- Buttlar, H. (1 October 2003). "Nazi-"Euthanasie" Forscher öffnen Inventar des Schreckens" [Nazi 'Euthanasia' Researchers open Inventory of Horror]. Der Spiegel (online ed.). Hamburg. ISSN 0038-7452. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "Nazis Killed Hundreds at Austrian Mental Hospital". The Local AB. 25 November 2014. no issn. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

Websites

- Beer, Mathias (2015). "Die Entwicklung der Gaswagen beim Mord an den Juden" [The Development of the Gas-Van in the Murdering of the Jews]. The Final Solution. Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Munich: Jewish Virtual Library. pp. 403–417. ISSN 0042-5702. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Burleigh, Michael; Wippermann, Wolfang (2014). "Nazi Racial Science". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- Hojan, Artur; Munro, Cameron (2015). Overview of Nazi 'Euthanasia' Programme. Berlin: The Tiergartenstraße 4 Association. ISBN 978-1-4438-5422-1. OCLC 875635606. Further information':' Kaminsky, Uwe (2014), "Mercy Killing and Economism" [in:] Bialas, Wolfgang; Fritze, Lothar (ed.), Nazi Ideology and Ethics. pp. 263–265. Cambridge Scholars Publishing "Once emptied, the Polish institutions were almost exclusively turned over to the SS"[p. 265]. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- Hojan, Artur; Munro, Cameron (28 February 2013). "Nazi Euthanasia Programme in Occupied Poland 1939–1945". Berlin, Kleisthaus: Tiergartenstraße 4. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- "History of Świecie Hospital" [Historia szpitala w Świeciu]. Regional State Hospital: Wojewódzki Szpital dla Nerwowo i Psychicznie Chorych, Samorząd Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017.

- "Psychiatrzy w obronie pacjentów". Niedziela, Tygodnik Katolicki. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017.

- Kaelber, Lutz (29 August 2015). "Am Spiegelgrund". University of Vermont. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "The Memorial Page of Nazi Euthanasia Programs". Germany National Memorial. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "United States of America v. Alfons Klein et al" (PDF). Captured German Records. National Archives and Records Administration. 1980. 12-449, 000-12-31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

Further reading

[edit]Books

[edit]- Bachrach, Susan D.; Kuntz, Dieter (2004). Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Washington D.C.: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2916-5.

- Benzenhöfer, Udo (2010). Euthanasia in Germany Before and During the Third Reich. Münster/Ulm: Verlag Klemm & Oelschläger. ISBN 978-3-86281-001-7.

- Binding, K.; Hoche, A. (1920). Die Freigabe der Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens: Ihr Mass u. ihre Form [The Release of the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life: Their Mass and Shape]. Leipzig: Meiner. OCLC 72022317.

- Burleigh, M.; Wippermann, W. (1991). The Racial State: Germany 1933–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39114-6.

- Burleigh, M. (1997). "Part II". Ethics and Extermination: Reflections on Nazi Genocide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 113–152. ISBN 978-0-521-58211-7.

- Burleigh, M. (2001) [2000]. "Medicalized Mass Murder". The Third Reich: A New History (Pbk. Pan ed.). London: Macmillan. pp. 382–404. ISBN 978-0-330-48757-3.

- Evans, Richard J. (2009). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594202063.