Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chronometry

View on Wikipedia

Chronometry[a] or horology[b] (lit. 'the study of time') is the science studying the measurement of time and timekeeping.[3] Chronometry enables the establishment of standard measurements of time, which have applications in a broad range of social and scientific areas. Horology usually refers specifically to the study of mechanical timekeeping devices, while chronometry is broader in scope, also including biological behaviours with respect to time (biochronometry), as well as the dating of geological material (geochronometry).

Horology is commonly used specifically with reference to the mechanical instruments created to keep time: clocks, watches, clockwork, sundials, hourglasses, clepsydras, timers, time recorders, marine chronometers, and atomic clocks are all examples of instruments used to measure time. People interested in horology are called horologists. That term is used both by people who deal professionally with timekeeping apparatuses, as well as enthusiasts and scholars of horology. Horology and horologists have numerous organizations, both professional associations and more scholarly societies. The largest horological membership organisation globally is the NAWCC, the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, which is US based, but also has local chapters elsewhere.

Records of timekeeping are attested during the Paleolithic, in the form of inscriptions made to mark the passing of lunar cycles and measure years. Written calendars were then invented, followed by mechanical devices. The highest levels of precision are presently achieved by atomic clocks, which are used to track the international standard second.[4][5]

Etymology

[edit]Chronometry is derived from two root words, Ancient Greek chronos (χρόνος) and metron (μέτρον), with rough meanings of "time" and "measure".[6] The combination of the two is taken to mean time measuring.

In the Ancient Greek lexicon, meanings and translations differ depending on the source. Chronos, used in relation to time when in definite periods, and linked to dates in time, chronological accuracy, and sometimes in rare cases, refers to a delay.[7] The length of the time it refers ranges from seconds to seasons of the year to lifetimes, it can also concern periods of time wherein some specific event takes place, or persists, or is delayed.[6]

The root word is correlated with the god Chronos in Ancient Greek mythology, who embodied the image of time, originated from out of the primordial chaos. Known as the one who spins the Zodiac Wheel, further evidence of his connection to the progression of time.[8] However, Ancient Greek makes a distinction between two types of time, chronos, the static and continuing progress of present to future, time in a sequential and chronological sense, and kairos, a concept based in a more abstract sense, representing the opportune moment for action or change to occur.

Kairos (καιρός) carries little emphasis on precise chronology, instead being used as a time specifically fit for something, or also a period of time characterised by some aspect of crisis, also relating to the endtime.[6] It can as well be seen in the light of an advantage, profit, or fruit of a thing,[7] but has also been represented in apocalyptic feeling, and likewise shown as variable between misfortune and success, being likened to a body part vulnerable due to a gap in armor for Homer,[9] benefit or calamity depending on the perspective. It is also referenced in Christian theology, being used as implication of God's action and judgement in circumstances.[10][11]

Because of the inherent relation between chronos and kairos, their function the Ancient Greek's portrayal and concept of time, understanding one means understanding the other in part. The implication of chronos, an indifferent disposition and eternal essence lies at the core of the science of chronometry, bias is avoided, and definite measurement is favoured.

Subfields

[edit]| Time |

|---|

|

Biochronometry

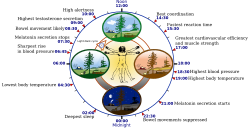

[edit]Biochronometry (also chronobiology or biological chronometry) is the study of biological behaviours and patterns seen in animals with factors based in time. It can be categorised into circadian rhythms and circannual cycles. Examples of these behaviours can be: the relation of daily and seasonal tidal cues to the activity of marine plants and animals,[12] the photosynthetic capacity and phototactic responsiveness in algae,[13] or metabolic temperature compensation in bacteria.[14]

Circadian rhythms of various species can be observed through their gross motor function throughout the course of a day. These patterns are more apparent with the day further categorised into activity and rest times. Investigation into a species is conducted through comparisons of free-running and entrained rhythms, where the former is attained from within the species' natural environment and the latter from a subject that has been taught certain behaviours. Circannual rhythms are alike but pertain to patterns within the scale of a year, patterns like migration, moulting, reproduction, and body weight are common examples, research and investigation are achieved with similar methods to circadian patterns.[14]

Circadian and circannual rhythms can be seen in all organisms, both single and multi-celled.[15][16] A sub-branch of biochronometry is microbiochronometry (also chronomicrobiology or microbiological chronometry), the examination of behavioural sequences and cycles within micro-organisms. Adapting to circadian and circannual rhythms is an essential evolution for living organisms.[15][16] These studies, as well as educating on the adaptations of organisms also bring to light certain factors affecting many of species’ and organisms’ responses, and can also be applied to further understand the overall physiology, this can be for humans as well. Examples include: factors of human performance, sleep, metabolism, and disease development, which are all connected to cycles related to biochronometry.[16]

Mental chronometry

[edit]Mental chronometry (also called cognitive chronometry) studies human information processing mechanisms, namely reaction time and perception. As well as a field of chronometry, it also forms a part of cognitive psychology and its contemporary human information processing approach.[17] Research comprises applications of the chronometric paradigms – many of which are related to classical reaction time paradigms from psychophysiology[18] – through measuring reaction times of subjects with varied methods, and contribute to studies in cognition and action.[19] Reaction time models and the process of expressing the temporostructural organisation of human processing mechanisms have an innate computational essence to them. It has been argued that because of this, conceptual frameworks of cognitive psychology cannot be integrated in their typical fashions.[20]

One common method is the use of event-related potentials (ERPs) in stimulus-response experiments. These are fluctuations of generated transient voltages in neural tissues that occur in response to a stimulus event either immediately before or after.[19] This testing emphasises the mental events' time-course and nature and assists in determining the structural functions in human information processing.[21]

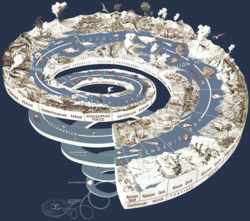

Geochronometry

[edit]The dating of geological materials makes up the field of geochronometry, and falls within areas of geochronology and stratigraphy, while differing itself from chronostratigraphy. The geochronometric scale is periodic, its units working in powers of 1000, and is based in units of duration, contrasting with the chronostratigraphic scale. The distinctions between the two scales have caused some confusion – even among academic communities.[22]

Geochronometry deals with calculating a precise date of rock sediments and other geological events, giving an idea as to what the history of various areas is, for example, volcanic and magmatic movements and occurrences can be easily recognised, as well as marine deposits, which can be indicators for marine events and even global environmental changes.[23] This dating can be done in a number of ways. All dependable methods – barring the exceptions of thermoluminescence, radioluminescence[24] and ESR (electron spin resonance) dating – are based in radioactive decay, focusing on the degradation of the radioactive parent nuclide and the corresponding daughter product's growth.[23]

By measuring the daughter isotopes in a specific sample its age can be calculated. The preserved conformity of parent and daughter nuclides provides the basis for the radioactive dating of geochronometry, applying the Rutherford Soddy Law of Radioactivity, specifically using the concept of radioactive transformation in the growth of the daughter nuclide.[25]

Thermoluminescence is an extremely useful concept to apply, being used in a diverse amount of areas in science,[26] dating using thermoluminescence is a cheap and convenient method for geochronometry.[27] Thermoluminescence is the production of light from a heated insulator and semi-conductor, it is occasionally confused with incandescent light emissions of a material, a different process despite the many similarities. However, this only occurs if the material has had previous exposure to and absorption of energy from radiation. Importantly, the light emissions of thermoluminescence cannot be repeated.[26] The entire process, from the material's exposure to radiation would have to be repeated to generate another thermoluminescence emission. The age of a material can be determined by measuring the amount of light given off during the heating process, by means of a phototube, as the emission is proportional to the dose of radiation the material absorbed.[23]

Time metrology

[edit]Time metrology or time and frequency metrology is the application of metrology for timekeeping, including frequency stability.[28][29] Its main tasks are the realization of the second as the SI unit of measurement for time and the establishment of time standards and frequency standards as well as their dissemination.[30]

History

[edit]Early humans would have used their basic senses to perceive the time of day, and relied on their biological sense of time to discern the seasons in order to act accordingly. Their physiological and behavioural seasonal cycles mainly being influenced by a melatonin based photoperiod time measurement biological system – which measures the change in daylight within the annual cycle, giving a sense of the time in the year – and their circannual rhythms, providing an anticipation of environmental events months beforehand to increase chances of survival.[31]

There is debate over when the earliest use of lunar calendars was, and over whether some findings constituted as a lunar calendar.[32][33] Most related findings and materials from the palaeolithic era are fashioned from bones and stone, with various markings from tools. These markings are thought to not have been the result of marks to represent the lunar cycles but non-notational and irregular engravings, a pattern of latter subsidiary marks that disregard the previous design is indicative of the markings being the use of motifs and ritual marking instead.[32]

However, as humans' focus turned to farming the importance and reliance on understanding the rhythms and cycle of the seasons grew, and the unreliability of lunar phases became problematic. An early human accustomed to the phases of the moon would use them as a rule of thumb, and the potential for weather to interfere with reading the cycle further degraded the reliability.[32][34] The length of a moon is on average less than our current month, not acting as a dependable alternate, so as years progress the room of error between would grow until some other indicator would give indication.[34]

The Ancient Egyptian calendars were among the first calendars made, and the civil calendar even endured for a long period afterwards, surviving past even its culture's collapse and through the early Christian era. It has been assumed to have been invented near 4231 BC by some, but accurate and exact dating is difficult in its era and the invention has been attributed to 3200 BC, when the first historical king of Egypt, Menes, united Upper and Lower Egypt.[34] It was originally based on cycles and phases of the moon, however, Egyptians later realised the calendar was flawed upon noticing the star Sirius rose before sunrise every 365 days, a year as we know it now, and was remade to consist of twelve months of thirty days, with five epagomenal days.[35][36] The former is referred to as the Ancient Egyptians' lunar calendar, and the latter the civil calendar.

Early calendars often hold an element of their respective culture's traditions and values, for example, the five day intercalary month of the Ancient Egyptian's civil calendar representing the birthdays of the gods Horus, Isis, Set, Osiris and Nephthys.[34][36] Maya use of a zero date as well as the Tzolkʼin's connection to their thirteen layers of heaven (the product of it and all the human digits, twenty, making the 260-day year of the year) and the length of time between conception and birth in pregnancy.[37]

Museums and libraries

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

Europe

[edit]There are many horology museums and several specialized libraries devoted to the subject. One example is the Royal Greenwich Observatory, which is also the source of the Prime Meridian and the home of the first marine timekeepers accurate enough to determine longitude (made by John Harrison). Other horological museums in the London area include the Clockmakers' Museum, which re-opened at the Science Museum in October 2015, the horological collections at the British Museum, the Science Museum (London), and the Wallace Collection. The Guildhall Library in London contains an extensive public collection on horology. In Upton, also in the United Kingdom, at the headquarters of the British Horological Institute, there is the Museum of Timekeeping. A more specialised museum of horology in the United Kingdom is the Cuckooland Museum in Cheshire, which hosts the world's largest collection of antique cuckoo clocks.

One of the more comprehensive museums dedicated to horology is the Musée international d'horlogerie, in La Chaux-de-Fonds in Switzerland, which contains a public library of horology. The Musée d'Horlogerie du Locle is smaller but located nearby. Other good horological libraries providing public access are at the Musée international d'horlogerie in Switzerland, at La Chaux-de-Fonds, and at Le Locle.

In France, Besançon has the Musée du Temps (Museum of Time) in the historic Palais Grenvelle. In Serpa and Évora, in Portugal, there is the Museu do Relógio. In Germany, there is the Deutsches Uhrenmuseum in Furtwangen im Schwarzwald, in the Black Forest, which contains a public library of horology.

North America

[edit]The two leading specialised horological museums in North America are the National Watch and Clock Museum in Columbia, Pennsylvania, and the American Clock and Watch Museum in Bristol, Connecticut. Another museum dedicated to clocks is the Willard House and Clock Museum in Grafton, Massachusetts. One of the most comprehensive horological libraries open to the public is the National Watch and Clock Library in Columbia, Pennsylvania.

Organizations

[edit]Notable scholarly horological organizations include:

- American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute – AWCI (United States of America)

- Antiquarian Horological Society – AHS (United Kingdom)

- British Horological Institute – BHI (United Kingdom)

- Chronometrophilia (Switzerland)

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie – DGC (Germany)

- Horological Society of New York – HSNY (United States of America)

- National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors – NAWCC (United States of America)

- UK Horology - UK Clock & Watch Company based in Bristol

Glossary

[edit]| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Chablon | French term for a watch movement (not including the dial and hands), that is not completely assembled. |

| Ébauche | French term (commonly used in English-speaking countries) for a movement blank, i.e., an incomplete watch movement sold as a set of loose parts—comprising the main plate, bridges, train, winding and setting mechanism, and regulator. The timing system, escapement, and mainspring, however, are not parts of the ébauche. |

| Établissage | French term for the method of manufacturing watches or movements by assembling their various components. It generally includes the following operations: receipt, inspection and stocking of the "ébauche", the regulating elements and the other parts of the movement and of the make-up; assembling; springing and timing; fitting the dial and hands; casing; final inspection before packing and dispatching. |

| Établisseur | French term for a watch factory that assembles watches from components it buys from other suppliers. |

| Factory, works | In the Swiss watch industry, the term manufacture is used of a factory that manufacturers watches almost completely, as distinct from an atelier de terminage, which only assembles, times, and fits hands and casing. |

| Manufacture d'horlogerie | French term for a watch factory that produces components (particularly the "ébauche") for its products (watches, alarm and desk clocks, etc.). |

| Remontoire | French term for a small secondary source of power, typically a weight or spring, which runs the timekeeping mechanism and is itself periodically rewound by the timepiece's main power source, such as a mainspring. |

| Terminage | French term denoting the process of assembling watch parts for the account of a producer. |

| Termineur | French term for an independent watchmaker (or workshop) engaged in assembling watches, either wholly or in part, for the account of an "établisseur" or a "manufacture", who supply the necessary loose parts. See "atelier de terminage" above. |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ (from Ancient Greek χρόνος (khrónos) 'time' and μέτρον (métron) 'measure')

- ^ Related to Latin horologium; from Ancient Greek ὡρολόγιον (hōrológion) 'instrument for telling the hour'; from ὥρα (hṓra) 'hour, time', interfix -o-, and suffix -logy)[1][2]

References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "horology". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ ὡρολόγιον, ὥρα. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Webster's Dictionary, 1913

- ^ Lombardi, M. A.; Heavner, T.P.; Jefferts, S. R. (2007). "NIST Primary Frequency Standards and the Realization of the SI Second". NCSLI Measure. 2 (4). NCSL International: 74–89. doi:10.1080/19315775.2007.11721402. S2CID 114607028.

- ^ Ramsey, N. F. (2005). "History of Early Atomic Clocks". Metrologia. 42 (3). IOP Publishing: S1 – S3. Bibcode:2005Metro..42S...1R. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/42/3/S01. S2CID 122631200.

- ^ a b c Bauer, W. (2001). A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Third Edition). University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b Liddell, H & Scott, R. (1996). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford University Press, USA.

- ^ Vrobel, S. (2007). The Kairos Syndrome. N.p.

- ^ Murhchadha. F.O. (2013). The Time of Revolution: Kairos and Chronos in Heidegger. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ Strong's Greek: 2540. καιρός (kairos). (n.d.). Retrieved 2 October 2020, from https://biblehub.com/greek/2540.htm

- ^ Mark 1:15 Greek Text Analysis. (n.d.). Retrieved 2 October 2020, from https://biblehub.com/text/mark/1-15.htm

- ^ Naylor, E. (2010). Chronobiology of Marine Organisms. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Bünning, E. (1964). The Physiological Clock: Endogenous diurnal rhythms and biological chronometry. Springer Verlag.

- ^ a b Menaker, M (Ed.) (1971). Biochronometry: Proceedings of a Symposium. National Academy of Sciences, USA.

- ^ a b Edmunds, L.N. (1985). Physiology of Circadian Rhythms in Micro-organisms. Elsevier.

- ^ a b c Gillette, M.U. (2013). Chronobiology: biological timing in health and disease. Academic Press.

- ^ Abrams, R.A, Balota, D.A. (1991). Mental Chronometry: Beyond Reaction Time. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Jensen, A.R. (2006). Clocking the Mind: Mental chronometry and individual differences. Elsevier.

- ^ a b Meyer, D.E, et al. (1988). Modern Mental Chronometry. Elsevier.

- ^ Van der Molen, M.W, et al. (1991). Chronopsychophysiology: Mental chronometry augmented by psychophysiological time markers. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Coles, M.G, et al. (1995). Mental Chronometry and the study of Human Information Processing. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Harland, W.B. (1975). The two geological time scales. Nature.

- ^ a b c Elderfield, H (Ed.). (2006). The oceans and marine geochemistry. Elsevier.

- ^ Erfurt, G (et al.). (2003). A fully automated multi-spectral radioluminescence reading system for geochronometry and dosimetry. Elsevier.

- ^ Rasskazov, S.V, Brandt, S.R & Brandt I.S. (2010). Radiogenic isotopes in geological processes. Springer.

- ^ a b McKeever, S.W.S. (1983). Thermoluminescence of solids. Academic Press.

- ^ Price List – CHNet. (n.d.). Retrieved 25 October 2020, from http://chnet.infn.it/en/price-list/

- ^ Arias, Elisa Felicitas (2 July 2005). "The metrology of time". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 363 (1834). The Royal Society: 2289–2305. Bibcode:2005RSPTA.363.2289A. doi:10.1098/rsta.2005.1633. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 16147510. S2CID 20446647.

- ^ Levine, Judah (1999). "Introduction to time and frequency metrology". Review of Scientific Instruments. 70 (6). AIP Publishing: 2567–2596. Bibcode:1999RScI...70.2567L. doi:10.1063/1.1149844. ISSN 0034-6748.

- ^ "time and frequency". BIPM. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Lincoln, GA, Andersson, H & Loudon A. (2003). Clock genes in calendar cells as the basis for annual timekeeping in mammals. BioScientifica.

- ^ a b c Marshack, A. (1989). Current Anthropology: On Wishful Thinking and Lunar "Calendars", Vol 30(4), p.491-500. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ D'Errico, F. (1989). Current Anthropology: Palaeolithic Lunar Calendars: A Case of Wishful Thinking?. Vol 30(1), p.117-118. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c d Winlock, H.E. (1940). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society: The Origin of the Ancient Egyptian Calendar, Vol 83, p.447-464. American Philosophical Society.

- ^ Jones, A. (1997). On the Reconstructed Macedonian and Egyptian Lunar Calendars. Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH.

- ^ a b Spalinger, A. (1995). Journal of Near Eastern Studies: Some Remarks on the Epagomenal Days in Ancient Egypt, Vol 54(1), p.33-47. Chicago University Press.

- ^ Kinsella, J., & Bradley, A. (1934). The Mathematics Teacher: The Mayan Calendar. Vol 27(7), p.340-343. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Further reading

[edit]- Perman, Stacy (2013). A grand complication: the race to build the world's most legendary watch. New York: Atria. ISBN 978-1-439-19008-1.

- Berner, G.A., Illustrated Professional Dictionary of Horology, Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry FH 1961 - 2012

- Daniels, George, Watchmaking, London: Philip Wilson Publishers, 1981 (reprinted June 15, 2011)

- Beckett, Edmund, A Rudimentary Treatise on Clocks, Watches and Bells, 1903, from Project Gutenberg

- Grafton, Edward, Horology, a popular sketch of clock and watch making, London: Aylett and Jones, 1849

- IEEE Guide for Measurement of Environmental Sensitivities of Standard Frequency Generators (Revision of IEEE Std 1193 - 1994), Piscataway, NJ: IEEE, doi:10.1109/ieeestd.2004.94440, ISBN 0-738-13711-1

- IEEE Standard Definitions of Physical Quantities for Fundamental Frequency and Time Metrology—Random Instabilities, Piscataway, NJ: IEEE, doi:10.1109/ieeestd.2008.4797525, ISBN 978-0-738-16855-5

Chronometry

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Etymology

The term chronometry derives from the Ancient Greek roots khronos (χρόνος), meaning "time," and metron (μέτρον), meaning "measure" or "meter."[7] This combination reflects the discipline's focus on the scientific measurement of time intervals and durations. The suffix -metry itself originates from the same Greek metron, commonly used in English to denote systems of measurement, as seen in terms like geometry and anthropometry. The word chronometry first appeared in English in the early 19th century, with its earliest recorded use in 1833 by the astronomer Sir John Herschel in his treatise Astronomy. Herschel employed the term to describe the precise fixing of temporal moments in astronomical observations, stating that "chronometry … enables us to fix the moments in which phenomena occur, with the last degree of precision."[7][2] This introduction aligned with growing advancements in timekeeping instruments during the era, such as marine chronometers, which demanded rigorous scientific terminology for accuracy in navigation and celestial studies. Astronomers like Johann Heinrich von Mädler also contributed to early applications through chronometrical observations in 1833 for the Russian government, underscoring the term's relevance in 19th-century astronomical practice.[8] In contrast to horology, which derives from Greek hōra (ὥρα, "hour" or "season") and logos (λόγος, "study" or "account") and primarily refers to the art and craft of constructing mechanical timepieces like clocks and watches, chronometry encompasses a broader scientific scope. Horology emphasizes the design, manufacture, and maintenance of horological devices, whereas chronometry extends to all methods of precise time measurement, including non-mechanical techniques and theoretical principles across disciplines. This distinction highlights chronometry's role as a foundational metrological science rather than a specialized craft.Core Concepts

Chronometry is the quantitative science of measuring time intervals and epochs with precision, encompassing the development and application of methods to quantify durations and moments in physical processes. This distinguishes it from qualitative aspects of time perception, such as subjective experiences of duration influenced by psychological factors, which do not rely on standardized instrumentation.[2][9] The foundational unit in chronometry is the second (s), the base unit of time in the International System of Units (SI). It is defined as the duration of exactly 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the cesium-133 atom, at rest and at a temperature of 0 K.[10] This atomic definition ensures a stable and reproducible standard for time measurement, independent of astronomical or mechanical variations. A core principle of chronometry in classical physics is the uniformity of time, positing that time progresses at a constant rate everywhere and is unaffected by spatial location or motion. However, special relativity introduces effects on time measurement, including time dilation, where the passage of time for an observer differs based on relative velocity, such that a moving clock appears to run slower from the perspective of a stationary observer.[11] Chronometry further differentiates between coordinate time, which represents the temporal coordinate in a specific reference frame, and proper time, the invariant interval measured directly by a clock along its path through spacetime.[12]Subfields

Biological Chronometry

Biological chronometry, also known as biochronometry, is the scientific study of endogenous biological clocks that govern timing processes in living organisms, particularly focusing on rhythmic phenomena such as circadian cycles. These internal timekeepers enable organisms to anticipate and adapt to environmental changes, synchronizing physiological functions like sleep, metabolism, and hormone release with external cues. In mammals, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), located in the hypothalamus, serves as the primary master clock, coordinating approximately 24-hour rhythms through interconnected neuronal networks that generate self-sustaining oscillations via transcriptional-translational feedback loops involving clock genes like CLOCK and PER.[13][14] Key techniques in biological chronometry include actigraphy, a non-invasive method that uses wearable accelerometers to monitor movement patterns and infer sleep-wake cycles over extended periods, providing objective data on rest-activity rhythms without the need for laboratory confinement. For assessing cellular aging, telomere length measurement—often via quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or fluorescence in situ hybridization—quantifies the progressive shortening of protective chromosomal caps, which correlates with replicative senescence as described by the Hayflick limit, where human fibroblasts typically undergo around 50 population doublings before halting division.[15][16] In humans, the intrinsic circadian period averages approximately 24.2 hours under constant conditions, slightly longer than the solar day, which requires daily entrainment by zeitgebers like light to maintain alignment with the 24-hour environment. Disruptions to these rhythms, such as those induced by transmeridian travel or irregular work schedules, desynchronize the SCN from external cues, leading to conditions like jet lag disorder—characterized by insomnia, fatigue, and cognitive impairment—or shift work sleep disorder, which increases risks for metabolic and cardiovascular issues due to chronic misalignment.[17][18][19]Psychological Chronometry

Psychological chronometry, also known as mental chronometry, is the scientific study of the duration of mental processes through the measurement of reaction times in response to stimuli. This field emerged in the 19th century as a method to quantify cognitive operations by analyzing the time elapsed between a sensory input and a behavioral output, providing insights into the sequential stages of information processing in the human brain. The foundational work was conducted by Dutch physiologist Franciscus Donders in 1868, who introduced the subtractive method to isolate the time required for specific mental stages by comparing reaction times across tasks of varying complexity. In simple reaction time (SRT) tasks, where participants respond to a single, predictable stimulus, average human response latencies are approximately 200 milliseconds, encompassing basic sensory perception and motor execution. Choice reaction time (CRT) tasks, involving discrimination among multiple stimuli and selection of an appropriate response, typically take around 400 milliseconds, reflecting additional cognitive demands.[20][21] Donders' subtractive approach decomposes these latencies into discrete stages: stimulus identification (the time to perceive and categorize the input), response selection (choosing the appropriate action), and response execution (initiating the motor output). By subtracting SRT from more complex tasks like go/no-go or choice reactions, he estimated the duration of identification and selection processes, establishing that mental operations occur in measurable, additive intervals rather than instantaneously. This method has been widely adopted and refined, revealing that identification and selection each add roughly 100-200 milliseconds to baseline motor times.[22] In contemporary research, psychological chronometry integrates with neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to map the neural correlates of these temporal stages. Latency-resolved fMRI allows researchers to track the sequence of brain activations during reaction tasks, correlating hemodynamic responses with behavioral timings to identify regions involved in stimulus processing (e.g., visual cortex) versus decision-making (e.g., prefrontal areas). For instance, studies have shown that response selection engages the supplementary motor area with latencies aligning to the 150-250 millisecond range observed in subtractive paradigms. These applications extend mental chronometry beyond behavioral measures, enhancing understanding of cognitive timing in clinical contexts like attention deficits. Variations in alertness, influenced by circadian biological rhythms, can modulate these reaction times by up to 20-30 milliseconds across the day.[23][24][25]Geological Chronometry

Geological chronometry, also known as geochronometry, encompasses methods to determine the absolute ages of rocks, minerals, and geological events on timescales ranging from thousands to billions of years, primarily through radiometric dating techniques that exploit the predictable decay of radioactive isotopes.[26] These methods provide quantitative timelines for Earth's history, enabling the construction of the geologic time scale and understanding of processes like plate tectonics and mountain building.[27] The foundational concept in radiometric dating is the exponential decay of unstable parent isotopes into stable daughter isotopes, governed by the law of radioactive decay. This is expressed as: where is the number of parent atoms remaining at time , is the initial number of parent atoms, is the decay constant (specific to each isotope), and is the elapsed time.[28] The half-life, the time for half the parent atoms to decay, is related to by , providing a constant rate independent of environmental conditions, which allows age calculation by measuring the parent-daughter ratio in a sample.[26] One of the most precise methods is uranium-lead (U-Pb) dating, which measures the decay of uranium-238 to lead-206 (half-life 4.468 billion years) and uranium-235 to lead-207 (half-life 704 million years) in accessory minerals like zircon crystals, which resist alteration and trap isotopes effectively during crystallization.[27] This technique has dated the oldest terrestrial materials, such as zircon crystals from Western Australia at approximately 4.4 billion years, and contributed to establishing Earth's age at 4.54 billion years through analysis of meteorites and lead isotope ratios.[29][30] For younger geological events, particularly in volcanic contexts, potassium-argon (K-Ar) dating is widely applied to measure the decay of potassium-40 to argon-40 (half-life 1.25 billion years) in potassium-bearing minerals like feldspar and mica within igneous rocks.[31] Upon cooling below the argon closure temperature (around 300–500°C), argon gas is trapped, allowing the accumulation of radiogenic argon to be dated, with applications to volcanic rocks from millions of years ago, such as those in the Yellowstone region.[32] Radiocarbon dating, suitable for more recent timescales, relies on the decay of carbon-14 (half-life 5,730 years) in organic materials, formed in the atmosphere and incorporated into living organisms until death, after which it decays without replenishment.[26] This method is effective up to about 50,000 years, as beyond this, the remaining carbon-14 levels become too low for accurate measurement, and it is calibrated using tree rings and lake varves for precision.[27][33] Complementing radiometric methods, stratigraphic correlation integrates relative dating by matching rock layers (strata) across regions based on shared lithology, fossils, and sedimentary features, providing a framework to assign absolute ages from dated reference points and resolve gaps in the continuous record of Earth's history.[34]Physical Chronometry

Physical chronometry examines the fundamental nature of time within the framework of physical laws, spanning scales from the quantum realm to the vast expanse of the cosmos. At the atomic and subatomic levels, time is quantized in ways that challenge classical notions, while on cosmic scales, it serves as a dimension intertwined with space. This subfield distinguishes itself by focusing on universal principles that govern time's behavior, independent of biological or geological contexts, emphasizing theoretical foundations over practical measurement devices. One key concept is the Planck time, defined as the smallest theoretically meaningful interval of time in current physical theories, approximately seconds. This unit arises from combining fundamental constants—the speed of light , the gravitational constant , and the reduced Planck constant —as , marking the scale where quantum mechanics and general relativity must unify to describe phenomena like the Big Bang's earliest moments. Below this duration, spacetime itself may lose its classical structure, rendering traditional time measurements inapplicable.[35] In the theory of relativity, time is not absolute but relative, exhibiting dilation for observers in motion relative to one another. The Lorentz factor, , quantifies this effect, where is the relative velocity and is the speed of light; for speeds approaching , increases, slowing time for the moving observer as measured by a stationary one. This principle, derived from the invariance of the speed of light, underscores how time propagates through spacetime, with m/s serving as the universal constant that links spatial and temporal dimensions across all inertial frames.[36] On cosmic scales, physical chronometry employs observables like the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation to estimate the universe's age at approximately 13.8 billion years. The CMB, the relic glow from the epoch of recombination about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, provides a snapshot of the early universe's uniformity and expansion history, allowing precise modeling of time's evolution since the initial singularity. This age determination relies on parameters such as the Hubble constant and matter density, refined through satellite missions analyzing CMB fluctuations.[37]Time Metrology

Measurement Standards

International Atomic Time (TAI) serves as a primary international time standard, providing a continuous, uniform scale realized through the weighted average of readings from over 450 atomic clocks contributed by more than 80 national metrology institutes worldwide.[38][39] The BIPM computes TAI monthly in deferred time, ensuring its stability and accuracy by incorporating data from these clocks, with primary frequency standards used for calibration to maintain traceability to the SI second. Established by the 13th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) in 1967, TAI realizes Terrestrial Time (TT) as defined by the International Astronomical Union, with a fixed offset of TT - TAI = 32.184 seconds.[40][41] Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), the global civil time standard, maintains synchronization with solar time while adopting the uniform rate of TAI, differing by an integer number of seconds to account for Earth's irregular rotation.[42] UTC is computed by the BIPM using TAI as its base, with adjustments introduced as leap seconds when the difference between UTC and UT1 (a measure of Earth's rotation) approaches 0.9 seconds.[43] As of November 2025, 27 leap seconds have been inserted since 1972, the most recent on December 31, 2016, with none added since then due to stable Earth rotation trends. In 2022, the 27th CGPM resolved to discontinue the practice of inserting leap seconds into UTC after 2035 to ensure long-term stability of time standards.[44][45] The evolution of time measurement standards reflects a shift from solar-based systems to atomic precision, beginning with Ephemeris Time (ET) in 1952, which derived uniform time from Earth's orbital motion around the Sun to address irregularities in rotational time.[46] This was supplanted by atomic time following the 1967 CGPM resolution, which defined the SI second—the core unit underlying TAI and UTC—as the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the cesium-133 atom at rest at 0 K.[47] Current discussions within the Consultative Committee for Time and Frequency (CCTF) explore redefining the second using optical transitions in atoms like strontium or ytterbium, potentially improving accuracy by orders of magnitude; as of the September 2025 CCTF meeting, evaluations of optical frequency standards continue, with a draft proposal targeted for the 2026 CGPM.[48][49][50] The Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM) holds primary responsibility for maintaining TAI through international coordination of clock data and dissemination via publications like Circular T.[51] The International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) monitors Earth's rotation and announces leap seconds six months in advance, ensuring UTC's alignment with astronomical observations while preserving the continuity of atomic time scales.[43]Precision Techniques

Precision techniques in chronometry encompass advanced instrumentation and methodologies that achieve fractional frequency accuracies on the order of 10^{-15} or better, enabling unprecedented stability in time measurement for scientific and technological applications. These methods primarily rely on atomic and optical phenomena to define and maintain time standards, surpassing earlier mechanical and quartz-based systems by orders of magnitude. Key developments include beam and maser clocks operating in the microwave domain, as well as more recent optical lattice and ion clocks that exploit higher-frequency transitions for superior precision.[52] Cesium beam atomic clocks represent a foundational precision technique, utilizing a beam of cesium-133 atoms excited by microwave radiation to measure the hyperfine transition frequency of 9,192,631,770 Hz, which defines the second in the International System of Units (SI). In these clocks, atoms pass through a vacuum tube where they interact with microwaves in a resonant cavity, and the frequency is adjusted to maximize the detection of atoms in the upper energy state, achieving fractional accuracies around 10^{-15}. For instance, the NIST-7 cesium beam clock, operational since 1993, maintains time such that it neither gains nor loses a second in approximately 6 million years.[53][54] Hydrogen maser clocks provide exceptional short-term stability for precision timing, employing a maser (microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) with hydrogen atoms in a storage bulb to oscillate at the 1,420 MHz hyperfine transition. Unlike cesium beam clocks, hydrogen masers prioritize stability over absolute accuracy, with fractional frequency instabilities as low as 10^{-16} over seconds to hours, making them ideal for applications requiring continuous, low-noise signals, though long-term accuracy is limited to about 10^{-13} due to cavity phase shifts. They are commonly used in ensembles to support time scales like UTC(NIST), where multiple masers contribute to averaging out individual drifts.[55][56] Optical atomic clocks mark a significant advancement, leveraging electronic transitions in the optical domain (hundreds of terahertz) rather than microwave frequencies, which allows for narrower linewidths and longer interrogation times, yielding accuracies up to 10^{-18} or better. Strontium-87 lattice clocks trap thousands of neutral atoms in an optical lattice formed by interfering laser beams, where the clock transition at 429 THz is probed, achieving systematic uncertainties of 8.1 × 10^{-19} in recent implementations by mitigating environmental perturbations like blackbody radiation shifts. For example, a strontium-87 lattice clock at the National Time Service Center (China) achieved a total uncertainty of 2 × 10^{-18} as of June 2025, further demonstrating advancements in mitigating environmental shifts. Similarly, ytterbium-171 optical lattice clocks at NIST have demonstrated total uncertainties of 3.3 × 10^{-18} as of 2023, with the clock laser locked to the atomic resonance for stable operation. These clocks outperform microwave standards by factors of 100 in accuracy and stability, paving the way for redefining the SI second.[57][58][59][60] A critical technique enhancing cesium-based precision is the atomic fountain method, which employs laser cooling to slow cesium atoms to microkelvin temperatures using six counter-propagating laser beams in an optical molasses configuration, reducing thermal motion and enabling interrogation times up to one second. In a fountain clock, the cooled atomic cloud is launched upward by laser momentum, passes through a microwave cavity twice during free fall (Rabi interrogation), and is detected after fluorescence, achieving fractional accuracies of 2–5 × 10^{-16}, as realized in NIST-F2. This approach minimizes Doppler shifts and second-order Zeeman effects, making fountain clocks the current basis for primary frequency standards.[61][62] Frequency combs serve as essential tools for linking optical clock frequencies to the microwave domain, generating a spectrum of evenly spaced laser modes (mode-locked femtosecond lasers) that act as a "ruler" in frequency space, with the comb's repetition rate (gigahertz) and carrier-envelope offset enabling direct division of optical signals to microwave outputs. Developed in the late 1990s, these combs have enabled the first optical clocks to surpass cesium standards in accuracy by providing phase-coherent transfer, as demonstrated in NIST comparisons where optical-to-microwave synthesis achieved noise levels below 10^{-15}.[63][64] Recent advances as of 2025 include quantum logic clocks, which use sympathetic cooling and readout of "clock" ions (e.g., aluminum-27) via entangled "logic" ions (e.g., magnesium-25) to detect forbidden optical transitions with minimal perturbation, attaining systematic uncertainties below 10^{-18}, such as NIST's Al+ clock at 9.4 × 10^{-19}. This quantum-entanglement approach enhances readout fidelity for ions with weak fluorescence, improving overall precision for fundamental physics tests. Additionally, space-based experiments like the Atomic Clock Ensemble in Space (ACES) mission, launched to the International Space Station in April 2025, integrate a cold-atom cesium clock (PHARAO) with hydrogen masers to verify general relativity through redshift measurements and gravitational time dilation, achieving frequency comparisons with ground clocks at 10^{-16} stability over intercontinental links.[65][66][67]Historical Development

Ancient and Medieval Periods

The earliest known devices for measuring time emerged in ancient civilizations, relying on natural phenomena such as the sun's shadow or the flow of water. In Egypt around 1500 BCE, sundials appeared as simple shadow clocks, often portable L-shaped instruments that divided the sunlit day into ten parts using a gnomon to cast shadows on a marked surface.[68] These devices marked a foundational step in chronometry by providing a visual means to track daytime hours based on solar position. Concurrently, water clocks, or clepsydrae, were developed in Mesopotamia, including Babylon, by approximately 1600 BCE, utilizing the steady outflow of water from a container to measure intervals, particularly useful for nighttime or cloudy conditions when sundials failed.[69] This innovation allowed for more consistent timekeeping in administrative and ritual contexts, as the regulated drip or level drop indicated elapsed time. Advancements in ancient chronometry built upon these basics, integrating astronomical observations for greater precision. The Greek astronomer Hipparchus, working between 147 and 127 BCE, proposed dividing the full day into 24 equinoctial hours of equal length, a system derived from his studies of solar and stellar movements to standardize time beyond varying seasonal daylight.[70] This conceptual shift from unequal "temporal hours" to fixed divisions influenced subsequent calendars and influenced Roman adaptations. In the Roman era, sundials proliferated and diversified; by 30 BCE, the architect Vitruvius documented 13 distinct styles across Greece, Asia Minor, and Italy, including conical and planar designs calibrated for local latitudes to enhance accuracy in public forums, temples, and private estates.[68] These instruments, often inscribed with seasonal adjustments, underscored chronometry's role in civic life, from scheduling legal proceedings to astronomical alignments. During the medieval period, chronometry transitioned toward mechanical solutions, driven by monastic needs for prayer timings and urban synchronization. In Europe, the first mechanical clocks emerged in the 13th century, employing verge-and-foliot escapements powered by weights to regulate motion, marking a departure from natural flows. The Salisbury Cathedral clock, installed in 1386, represents one of the oldest surviving examples, featuring a striking mechanism that chimed hours via bells, though it lacked a visible dial and focused on auditory signals for communal use.[71] Parallel innovations in the Islamic world advanced water-based automata; the polymath Isma'il al-Jazari described the elephant clock in his 1206 treatise The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, a monumental clepsydra resembling an elephant with internal gears, floats, and figures that released a bird every half hour to mark time, blending engineering precision with symbolic artistry.[72] These developments laid groundwork for escapement technology that would evolve in later centuries, emphasizing reliability in diverse cultural contexts.Modern and Contemporary Advances

The scientific revolution marked a pivotal era in chronometry, beginning with Christiaan Huygens' invention of the pendulum clock in 1656, which dramatically improved timekeeping accuracy to about 15 seconds per day by leveraging the pendulum as a harmonic oscillator to regulate the escapement mechanism.[73] This innovation addressed the limitations of earlier spring-driven clocks, which deviated by up to 15 minutes daily, enabling more reliable astronomical observations and navigation.[4] Building on this foundation, in the 18th century, John Harrison developed the marine chronometer H4, completed in 1761, which solved the longitude problem at sea by maintaining accuracy within seconds per day despite environmental challenges like temperature variations and motion.[74] Harrison's design, resembling a large pocket watch, used a fusion of materials and innovative compensation techniques to achieve this precision, revolutionizing maritime navigation and earning him a substantial reward from the British Longitude Act.[74] The 20th century brought electronic advancements, starting with the quartz clock invented by Warren Marrison at Bell Laboratories in 1927, which utilized the piezoelectric vibrations of a quartz crystal at around 50,000 Hz to drive a synchronous motor, achieving stabilities orders of magnitude better than mechanical clocks.[75] This technology became the basis for standard timekeeping in observatories and later consumer devices, with errors reduced to fractions of a second per month.[76] The era's crowning achievement was the development of atomic clocks; the first practical cesium-beam atomic clock was built in 1955 at the UK's National Physical Laboratory by Louis Essen and Jack Parry, using the hyperfine transition frequency of cesium-133 atoms to define time with an accuracy of one second in 300 years.[77] This device laid the groundwork for the 1967 redefinition of the second in the International System of Units (SI).[5] In 1978, the launch of the first NAVSTAR GPS satellite integrated atomic clock timekeeping into global navigation, enabling precise positioning by synchronizing satellite signals with ground-based clocks to within nanoseconds.[78] Post-2000 developments have pushed chronometry into the optical and quantum realms. Optical atomic clocks, emerging in the early 2000s, employ laser-cooled atoms such as strontium or ytterbium probed at optical frequencies—about 100,000 times higher than microwave frequencies—yielding fractional uncertainties below 10^{-18}, far surpassing cesium standards.[57] These clocks, exemplified by NIST's strontium lattice clock, have demonstrated stability that would neither gain nor lose a second over the age of the universe.[79] As of 2025, efforts to redefine the SI second based on an optical transition continue under the Consultative Committee for Time and Frequency, with a roadmap targeting implementation by 2030 pending consensus on the reference atom and international validation.[49] In July 2025, researchers conducted the world's largest intercontinental comparison of optical atomic clocks, involving ten clocks across multiple countries, demonstrating stability at levels that support the anticipated redefinition of the second by 2030.[80] Complementing this, quantum entanglement has enabled advanced time transfer techniques; by entangling ensembles of atoms across optical clocks, researchers have achieved precision beyond the standard quantum limit, reducing phase noise in distributed synchronization for applications like GPS enhancements and fundamental physics tests.[81] For instance, entangled strontium atoms in lattice clocks have improved frequency metrology stability by factors of up to 10, facilitating ultra-precise comparisons over long distances.[82]Applications

Scientific Uses

In astronomy, chronometry plays a pivotal role in pulsar timing arrays, which detect gravitational waves through precise measurements of pulsar pulse arrival times. The Hulse-Taylor binary pulsar, discovered in 1974, provided the first indirect evidence of gravitational wave emission via the observed decay in its orbital period, consistent with general relativity predictions; this work earned Russell A. Hulse and Joseph H. Taylor the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics.[83] In 2023, the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav) collaboration, along with international pulsar timing arrays, reported evidence for a low-frequency stochastic gravitational-wave background using 15 years of precise pulsar timing data, marking a significant milestone in gravitational-wave astrophysics.[84] Similarly, transit timing variations (TTVs) enable the detection of exoplanets by monitoring deviations in the timing of planetary transits across a star's disk, revealing the gravitational influence of unseen companions in multi-planet systems.[85] In physics, chronometric techniques test fundamental theories like general relativity using atomic clocks to measure time dilation effects. The 1971 Hafele-Keating experiment flew cesium-beam atomic clocks on commercial airliners eastward and westward around the world, observing time gains and losses of approximately 59 nanoseconds (eastward) and 273 nanoseconds (westbound) relative to stationary clocks, aligning with relativistic predictions for velocity and gravitational potentials.[86] In biology and geology, chronometry synchronizes experimental protocols and calibrates dating methods with atomic time standards for accurate temporal analysis. In circadian rhythm studies, precise timekeeping ensures consistent entrainment and measurement of ~24-hour oscillations in constant conditions, allowing researchers to quantify phase shifts and period lengths critical for understanding clock gene expression and health implications.[87] In geological applications, radiometric dating techniques function as natural atomic clocks by measuring radioactive decay in rocks, with decay constants calibrated against atomic time to establish absolute ages on the geologic time scale, enabling correlation of events like volcanic eruptions or sediment deposition over millions of years.[30]Technological and Everyday Uses

Chronometry plays a pivotal role in modern navigation systems, where precise timekeeping is essential for accurate positioning. The Global Positioning System (GPS) relies on atomic clocks aboard satellites to achieve frequency accuracies on the order of 2 × 10^{-12}, enabling positioning errors as low as a few meters by measuring signal travel times at the speed of light. This level of chronometric precision ensures that even small timing discrepancies, on the order of nanoseconds, do not compromise location accuracy for applications ranging from aviation to autonomous vehicles. As a terrestrial backup to mitigate GPS vulnerabilities such as jamming or spoofing, enhanced Long Range Navigation (eLoran) provides robust timing and positioning signals with no common failure modes to satellite-based systems, supporting continuity in critical infrastructure during disruptions. In computing and telecommunications, chronometry underpins network synchronization through protocols like the Network Time Protocol (NTP), which enables distributed systems to maintain clock coherence over the internet with accuracies typically better than 1 millisecond in local networks. NTP version 4, as standardized by the IETF, uses hierarchical stratum servers synchronized to UTC via atomic clocks or GPS, facilitating reliable timestamping in applications such as data logging and distributed computing. Blockchain technologies further leverage precise chronometry for transaction timestamping, where synchronized clocks prevent double-spending and ensure chronological integrity; for instance, Ethereum nodes often derive timestamps from NTP-synced sources to validate block orders with sub-second resolution. Everyday applications integrate chronometry seamlessly into consumer devices and high-stakes operations. Smartphones synchronize their internal clocks using cellular network signals via the Network Identity and Time Zone (NITZ) protocol, which broadcasts UTC-aligned time and timezone data from base stations, achieving accuracies sufficient for calendar functions and alarms without internet dependency. In financial trading, atomic time standards are critical for high-frequency operations, where regulations like the EU's MiFID II mandate clock synchronization to within 100 microseconds of UTC to timestamp trades accurately and enable regulatory surveillance, far surpassing the 50-millisecond tolerance for general automated systems in the US.Institutions and Resources

Museums and Libraries

Several prominent museums and libraries around the world house significant collections of chronometry artifacts, ranging from mechanical timekeepers to modern precision instruments, preserving the evolution of time measurement for public education and research. In Europe, the British Museum in London maintains a notable collection of marine chronometers, including examples featuring John Harrison's maintaining power mechanism, which were pivotal in 18th-century advancements in longitude determination at sea.[88] These items, such as pocket chronometers with spring detent escapements, illustrate early horological innovations and are displayed alongside related historical timepieces.[89] The Musée International d'Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, stands as one of the largest dedicated clock museums globally, featuring an extensive array of timekeeping devices from antiquity to the present, including atomic clocks that demonstrate post-World War II precision timing breakthroughs.[90] Its collection encompasses over 4,500 objects, with the atomic section highlighting instruments that contributed to the 1967 redefinition of the second based on cesium atom vibrations, underscoring Switzerland's role in horological research.[91] In North America, the National Watch and Clock Museum in Columbia, Pennsylvania, operated by the National Association of Watch & Clock Collectors, boasts the continent's largest assembly of timepieces, with galleries tracing chronometry from sundials and early mechanical clocks to quartz-based technologies that revolutionized consumer timekeeping in the late 20th century.[92] Exhibits on quartz history include pivotal devices like the first quartz wristwatches from the 1960s and 1970s, showcasing the shift from mechanical to electronic regulation and its impact on accuracy and affordability.[93] Complementing this, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., preserves extensive archival collections on timekeeping, including rare books, manuscripts, and maps that document the scientific and cultural history of chronometry, such as treatises on astronomical clocks and longitude calculations.[94] Beyond these regions, the Beijing Ancient Observatory in China exemplifies preservation efforts in Asia, with its 15th-century platform housing original Ming Dynasty bronze instruments like armillary spheres, celestial globes, and sundials used for celestial observations and time reckoning. Built in 1442, the site features eight large astronomical tools that integrated time measurement with calendar-making, offering insights into pre-modern East Asian chronometry.[95]Professional Organizations

The Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (BIPM), established in 1875 under the Metre Convention, serves as the intergovernmental organization responsible for coordinating international time metrology, including the calculation and dissemination of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) through integration of atomic clock data from global laboratories.[38] The BIPM Time Department maintains reference time scales such as UTC and Terrestrial Time (TT), ensuring worldwide synchronization for scientific, navigational, and telecommunication applications.[96] The International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) advances chronometry through its Commission on Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics (C15), established in 1996, which promotes research in precision frequency standards and optical clocks essential for high-accuracy timekeeping.[97] This commission fosters international conferences and collaborations that drive innovations in atomic physics relevant to chronometric standards, complementing efforts in symbols, units, and fundamental constants via Commission C2.[98] Nationally, the United States Naval Observatory (USNO) leads in atomic timekeeping as the official source of time for the U.S. Department of Defense, maintaining the Master Clock ensemble of over 100 atomic clocks that realizes UTC(USNO) with femtosecond precision.[99] The USNO's Precise Time Department provides timing signals via GPS and other systems, supporting military navigation and global positioning.[100] The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Time and Frequency Division, part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, develops and maintains national standards for time and frequency, including primary frequency standards like cesium fountains and optical clocks that contribute to international atomic time (TAI) and UTC(NIST).[101] As of 2025, NIST leads advancements in quantum timekeeping and frequency dissemination for applications in telecommunications, navigation, and fundamental physics.[102] In the United Kingdom, the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) functions as the national metrology institute, operating the UTC(NPL) time scale and primary frequency standards, including caesium fountains and optical clocks that contribute to international atomic time (TAI).[103] NPL's Time and Frequency Group develops transportable optical clocks and frequency dissemination techniques, enhancing precision metrology for applications in telecommunications and fundamental physics.[104] In 2025, global collaborations under initiatives like the international optical clock network have enabled simultaneous comparisons of ten next-generation atomic clocks across six countries, using fiber links and satellite connections to share optical clock signals with unprecedented stability, paving the way for potential redefinition of the second.[105] These efforts, involving institutions such as NIST, PTB, and NPL, focus on quantum-enhanced time transfer and entanglement for distributed chronometry networks.[106]Key Terms

Definitions of Essential Concepts

In chronometry, an epoch refers to a specific, fixed instant in time designated as a reference point for establishing time scales, calendars, celestial coordinate systems, star catalogs, and orbital parameters. This standardization ensures consistency in measurements across astronomical and navigational applications. For instance, the J2000.0 epoch is defined as noon Terrestrial Time on January 1, 2000 (Julian Date 2451545.0), serving as the standard reference for modern celestial mechanics and ephemerides.[107] Sidereal time measures the Earth's rotation relative to distant stars rather than the Sun, providing a basis for tracking celestial positions independent of solar motion.[108] It is calculated as the hour angle of the vernal equinox, with mean sidereal time using the mean equinox and apparent sidereal time using the true equinox to account for nutation.[109] A complete sidereal day, representing one full rotation relative to the stars, lasts approximately 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4 seconds of mean solar time.[110] Dynamical time denotes a class of relativistic time scales that superseded ephemeris time in celestial mechanics, incorporating general relativity to model the uniform motion of celestial bodies.[111] Defined by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), it includes variants such as Terrestrial Time (TT) for geocentric ephemerides and Barycentric Dynamical Time (TDB) for barycentric coordinates, ensuring predictions align with observed solar system dynamics.[110] These scales maintain a constant rate based on the second as realized by atomic clocks, adjusted for relativistic effects near Earth or the solar system barycenter.[112]Specialized Terminology

In chronometry, the Allan variance serves as a key metric for quantifying the frequency stability of precision oscillators and clocks, particularly in atomic timekeeping systems. Developed to analyze the statistical properties of frequency deviations in atomic standards, it provides a time-dependent measure that distinguishes between different noise types, such as white phase noise, flicker noise, and random walk frequency noise, which affect long-term stability. The Allan deviation, the square root of the variance, is defined as , where is the averaging time, represents the fractional frequency deviation between consecutive measurements, and the angle brackets denote an ensemble average; this formulation allows evaluation of stability over varying observation intervals, revealing optimal performance windows for clocks like cesium fountains or optical lattices.[113] Coherence time in atomic clocks refers to the duration over which the quantum superposition of atomic states—essential for precise interrogation of hyperfine or optical transitions—persists without significant decoherence from environmental perturbations such as magnetic field fluctuations, blackbody radiation, or collisions. In optical lattice clocks, for instance, achieving coherence times exceeding several seconds enables fractional frequency uncertainties below , as longer coherence allows more Ramsey interrogation cycles and reduces phase noise contributions; techniques like dynamical decoupling or lattice engineering can extend this time by mitigating scattering losses and thermal effects. This parameter directly impacts the clock's short-term stability and accuracy, with state-of-the-art systems demonstrating coherence times up to minutes in neutral atom ensembles.[114] The leap second is a discrete adjustment inserted into Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) to account for the irregular slowing of Earth's rotation relative to atomic time scales, ensuring that UTC remains within 0.9 seconds of UT1, the solar-based timescale. Administered by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), the procedure involves continuous monitoring of the UT1-UTC difference using very long baseline interferometry and satellite laser ranging; when predictions indicate the difference will approach 0.6 seconds, the IERS announces a leap second approximately six months in advance, typically adding one second (positive leap) at the end of June or December by extending the final minute to 61 seconds. Since 1972, 27 such insertions have occurred, all positive, with no negative leaps to date, reflecting the net deceleration of Earth's rotation due to tidal friction.[115] In November 2022, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) agreed to phase out leap seconds starting in 2035, allowing UTC and UT1 to diverge gradually by up to one second until at least 2135.[116]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_American_Cyclop%C3%A6dia_(1879)/M%C3%A4dler,_Johann_Heinrich