Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Basis (linear algebra)

View on Wikipedia

In mathematics, a set B of elements of a vector space V is called a basis (pl.: bases) if every element of V can be written in a unique way as a finite linear combination of elements of B. The coefficients of this linear combination are referred to as components or coordinates of the vector with respect to B. The elements of a basis are called basis vectors.

Equivalently, a set B is a basis if its elements are linearly independent and every element of V is a linear combination of elements of B.[1] In other words, a basis is a linearly independent spanning set.

A vector space can have several bases; however all the bases have the same number of elements, called the dimension of the vector space.

This article deals mainly with finite-dimensional vector spaces. However, many of the principles are also valid for infinite-dimensional vector spaces.

Basis vectors find applications in the study of crystal structures and frames of reference.

Definition

[edit]A basis B of a vector space V over a field F (such as the real numbers R or the complex numbers C) is a linearly independent subset of V that spans V. This means that a subset B of V is a basis if it satisfies the two following conditions:

- linear independence: for every finite subset of B, if for some in F, then ;

- spanning property: for every vector v in V, one can choose in F and in B such that .

The scalars are called the coordinates of the vector v with respect to the basis B, and by the first property they are uniquely determined.

A vector space that has a finite basis is called finite-dimensional. In this case, the finite subset can be taken as B itself to check for linear independence in the above definition.

It is often convenient or even necessary to have an ordering on the basis vectors, for example, when discussing orientation, or when one considers the scalar coefficients of a vector with respect to a basis without referring explicitly to the basis elements. In this case, the ordering is necessary for associating each coefficient to the corresponding basis element. This ordering can be done by numbering the basis elements. In order to emphasize that an order has been chosen, one speaks of an ordered basis, which is therefore not simply an unstructured set, but a sequence, an indexed family, or similar; see § Ordered bases and coordinates below.

Examples

[edit]

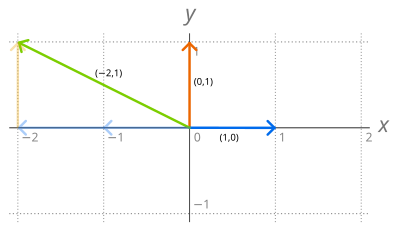

The set R2 of the ordered pairs of real numbers is a vector space under the operations of component-wise addition and scalar multiplication where is any real number. A simple basis of this vector space consists of the two vectors e1 = (1, 0) and e2 = (0, 1). These vectors form a basis (called the standard basis) because any vector v = (a, b) of R2 may be uniquely written as Any other pair of linearly independent vectors of R2, such as (1, 1) and (−1, 2), forms also a basis of R2.

More generally, if F is a field, the set of n-tuples of elements of F is a vector space for similarly defined addition and scalar multiplication. Let be the n-tuple with all components equal to 0, except the ith, which is 1. Then is a basis of which is called the standard basis of

A different flavor of example is given by polynomial rings. If F is a field, the collection F[X] of all polynomials in one indeterminate X with coefficients in F is an F-vector space. One basis for this space is the monomial basis B, consisting of all monomials: Any set of polynomials such that there is exactly one polynomial of each degree (such as the Bernstein basis polynomials or Chebyshev polynomials) is also a basis. (Such a set of polynomials is called a polynomial sequence.) But there are also many bases for F[X] that are not of this form.

Properties

[edit]Many properties of finite bases result from the Steinitz exchange lemma, which states that, for any vector space V, given a finite spanning set S and a linearly independent set L of n elements of V, one may replace n well-chosen elements of S by the elements of L to get a spanning set containing L, having its other elements in S, and having the same number of elements as S.

Most properties resulting from the Steinitz exchange lemma remain true when there is no finite spanning set, but their proofs in the infinite case generally require the axiom of choice or a weaker form of it, such as the ultrafilter lemma.

If V is a vector space over a field F, then:

- If L is a linearly independent subset of a spanning set S ⊆ V, then there is a basis B such that

- V has a basis (this is the preceding property with L being the empty set, and S = V).

- All bases of V have the same cardinality, which is called the dimension of V. This is the dimension theorem.

- A generating set S is a basis of V if and only if it is minimal, that is, no proper subset of S is also a generating set of V.

- A linearly independent set L is a basis if and only if it is maximal, that is, it is not a proper subset of any linearly independent set.

If V is a vector space of dimension n, then:

- A subset of V with n elements is a basis if and only if it is linearly independent.

- A subset of V with n elements is a basis if and only if it is a spanning set of V.

Coordinates

[edit]Let V be a vector space of finite dimension n over a field F, and be a basis of V. By definition of a basis, every v in V may be written, in a unique way, as where the coefficients are scalars (that is, elements of F), which are called the coordinates of v over B. However, if one talks of the set of the coefficients, one loses the correspondence between coefficients and basis elements, and several vectors may have the same set of coefficients. For example, and have the same set of coefficients {2, 3}, and are different. It is therefore often convenient to work with an ordered basis; this is typically done by indexing the basis elements by the first natural numbers. Then, the coordinates of a vector form a sequence similarly indexed, and a vector is completely characterized by the sequence of coordinates. An ordered basis, especially when used in conjunction with an origin, is also called a coordinate frame or simply a frame (for example, a Cartesian frame or an affine frame).

Let, as usual, be the set of the n-tuples of elements of F. This set is an F-vector space, with addition and scalar multiplication defined component-wise. The map is a linear isomorphism from the vector space onto V. In other words, is the coordinate space of V, and the n-tuple is the coordinate vector of v.

The inverse image by of is the n-tuple all of whose components are 0, except the ith that is 1. The form an ordered basis of , which is called its standard basis or canonical basis. The ordered basis B is the image by of the canonical basis of .

It follows from what precedes that every ordered basis is the image by a linear isomorphism of the canonical basis of , and that every linear isomorphism from onto V may be defined as the isomorphism that maps the canonical basis of onto a given ordered basis of V. In other words, it is equivalent to define an ordered basis of V, or a linear isomorphism from onto V.

Change of basis

[edit]Let V be a vector space of dimension n over a field F. Given two (ordered) bases and of V, it is often useful to express the coordinates of a vector x with respect to in terms of the coordinates with respect to This can be done by the change-of-basis formula, that is described below. The subscripts "old" and "new" have been chosen because it is customary to refer to and as the old basis and the new basis, respectively. It is useful to describe the old coordinates in terms of the new ones, because, in general, one has expressions involving the old coordinates, and if one wants to obtain equivalent expressions in terms of the new coordinates; this is obtained by replacing the old coordinates by their expressions in terms of the new coordinates.

Typically, the new basis vectors are given by their coordinates over the old basis, that is, If and are the coordinates of a vector x over the old and the new basis respectively, the change-of-basis formula is for i = 1, ..., n.

This formula may be concisely written in matrix notation. Let A be the matrix of the , and be the column vectors of the coordinates of v in the old and the new basis respectively, then the formula for changing coordinates is

The formula can be proven by considering the decomposition of the vector x on the two bases: one has and

The change-of-basis formula results then from the uniqueness of the decomposition of a vector over a basis, here ; that is for i = 1, ..., n.

Related notions

[edit]Free module

[edit]If one replaces the field occurring in the definition of a vector space by a ring, one gets the definition of a module. For modules, linear independence and spanning sets are defined exactly as for vector spaces, although "generating set" is more commonly used than that of "spanning set".

Like for vector spaces, a basis of a module is a linearly independent subset that is also a generating set. A major difference with the theory of vector spaces is that not every module has a basis. A module that has a basis is called a free module. Free modules play a fundamental role in module theory, as they may be used for describing the structure of non-free modules through free resolutions.

A module over the integers is exactly the same thing as an abelian group. Thus a free module over the integers is also a free abelian group. Free abelian groups have specific properties that are not shared by modules over other rings. Specifically, every subgroup of a free abelian group is a free abelian group, and, if G is a subgroup of a finitely generated free abelian group H (that is an abelian group that has a finite basis), then there is a basis of H and an integer 0 ≤ k ≤ n such that is a basis of G, for some nonzero integers . For details, see Free abelian group § Subgroups.

Analysis

[edit]In the context of infinite-dimensional vector spaces over the real or complex numbers, the term Hamel basis (named after Georg Hamel[2]) or algebraic basis can be used to refer to a basis as defined in this article. This is to make a distinction with other notions of "basis" that exist when infinite-dimensional vector spaces are endowed with extra structure. The most important alternatives are orthogonal bases on Hilbert spaces, Schauder bases, and Markushevich bases on normed linear spaces. In the case of the real numbers R viewed as a vector space over the field Q of rational numbers, Hamel bases are uncountable, and have specifically the cardinality of the continuum, which is the cardinal number , where (aleph-nought) is the smallest infinite cardinal, the cardinal of the integers.

The common feature of the other notions is that they permit the taking of infinite linear combinations of the basis vectors in order to generate the space. This, of course, requires that infinite sums are meaningfully defined on these spaces, as is the case for topological vector spaces – a large class of vector spaces including e.g. Hilbert spaces, Banach spaces, or Fréchet spaces.

The preference of other types of bases for infinite-dimensional spaces is justified by the fact that the Hamel basis becomes "too big" in Banach spaces: If X is an infinite-dimensional normed vector space that is complete (i.e. X is a Banach space), then any Hamel basis of X is necessarily uncountable. This is a consequence of the Baire category theorem. The completeness as well as infinite dimension are crucial assumptions in the previous claim. Indeed, finite-dimensional spaces have by definition finite bases and there are infinite-dimensional (non-complete) normed spaces that have countable Hamel bases. Consider , the space of the sequences of real numbers that have only finitely many non-zero elements, with the norm . Its standard basis, consisting of the sequences having only one non-zero element, which is equal to 1, is a countable Hamel basis.

Example

[edit]In the study of Fourier series, one learns that the functions {1} ∪ { sin(nx), cos(nx) : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } are an "orthogonal basis" of the (real or complex) vector space of all (real or complex valued) functions on the interval [0, 2π] that are square-integrable on this interval, i.e., functions f satisfying

The functions {1} ∪ { sin(nx), cos(nx) : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } are linearly independent, and every function f that is square-integrable on [0, 2π] is an "infinite linear combination" of them, in the sense that

for suitable (real or complex) coefficients ak, bk. But many[3] square-integrable functions cannot be represented as finite linear combinations of these basis functions, which therefore do not comprise a Hamel basis. Every Hamel basis of this space is much bigger than this merely countably infinite set of functions. Hamel bases of spaces of this kind are typically not useful, whereas orthonormal bases of these spaces are essential in Fourier analysis.

Geometry

[edit]The geometric notions of an affine space, projective space, convex set, and cone have related notions of basis.[4] An affine basis for an n-dimensional affine space is points in general linear position. A projective basis is points in general position, in a projective space of dimension n. A convex basis of a polytope is the set of the vertices of its convex hull. A cone basis[5] consists of one point by edge of a polygonal cone. See also a Hilbert basis (linear programming).

Random basis

[edit]For a probability distribution in Rn with a probability density function, such as the equidistribution in an n-dimensional ball with respect to Lebesgue measure, it can be shown that n randomly and independently chosen vectors will form a basis with probability one, which is due to the fact that n linearly dependent vectors x1, ..., xn in Rn should satisfy the equation det[x1 ⋯ xn] = 0 (zero determinant of the matrix with columns xi), and the set of zeros of a non-trivial polynomial has zero measure. This observation has led to techniques for approximating random bases.[6][7]

It is difficult to check numerically the linear dependence or exact orthogonality. Therefore, the notion of ε-orthogonality is used. For spaces with inner product, x is ε-orthogonal to y if (that is, cosine of the angle between x and y is less than ε).

In high dimensions, two independent random vectors are with high probability almost orthogonal, and the number of independent random vectors, which all are with given high probability pairwise almost orthogonal, grows exponentially with dimension. More precisely, consider equidistribution in n-dimensional ball. Choose N independent random vectors from a ball (they are independent and identically distributed). Let θ be a small positive number. Then for

| Eq. 1 |

N random vectors are all pairwise ε-orthogonal with probability 1 − θ.[7] This N growth exponentially with dimension n and for sufficiently big n. This property of random bases is a manifestation of the so-called measure concentration phenomenon.[8]

The figure (right) illustrates distribution of lengths N of pairwise almost orthogonal chains of vectors that are independently randomly sampled from the n-dimensional cube [−1, 1]n as a function of dimension, n. A point is first randomly selected in the cube. The second point is randomly chosen in the same cube. If the angle between the vectors was within π/2 ± 0.037π/2 then the vector was retained. At the next step a new vector is generated in the same hypercube, and its angles with the previously generated vectors are evaluated. If these angles are within π/2 ± 0.037π/2 then the vector is retained. The process is repeated until the chain of almost orthogonality breaks, and the number of such pairwise almost orthogonal vectors (length of the chain) is recorded. For each n, 20 pairwise almost orthogonal chains were constructed numerically for each dimension. Distribution of the length of these chains is presented.

Proof that every vector space has a basis

[edit]Let V be any vector space over some field F. Let X be the set of all linearly independent subsets of V.

The set X is nonempty since the empty set is an independent subset of V, and it is partially ordered by inclusion, which is denoted, as usual, by ⊆.

Let Y be a subset of X that is totally ordered by ⊆, and let LY be the union of all the elements of Y (which are themselves certain subsets of V).

Since (Y, ⊆) is totally ordered, every finite subset of LY is a subset of an element of Y, which is a linearly independent subset of V, and hence LY is linearly independent. Thus LY is an element of X. Therefore, LY is an upper bound for Y in (X, ⊆): it is an element of X, that contains every element of Y.

As X is nonempty, and every totally ordered subset of (X, ⊆) has an upper bound in X, Zorn's lemma asserts that X has a maximal element. In other words, there exists some element Lmax of X satisfying the condition that whenever Lmax ⊆ L for some element L of X, then L = Lmax.

It remains to prove that Lmax is a basis of V. Since Lmax belongs to X, we already know that Lmax is a linearly independent subset of V.

If there were some vector w of V that is not in the span of Lmax, then w would not be an element of Lmax either. Let Lw = Lmax ∪ {w}. This set is an element of X, that is, it is a linearly independent subset of V (because w is not in the span of Lmax, and Lmax is independent). As Lmax ⊆ Lw, and Lmax ≠ Lw (because Lw contains the vector w that is not contained in Lmax), this contradicts the maximality of Lmax. Thus this shows that Lmax spans V.

Hence Lmax is linearly independent and spans V. It is thus a basis of V, and this proves that every vector space has a basis.

This proof relies on Zorn's lemma, which is equivalent to the axiom of choice. Conversely, it has been proved that if every vector space has a basis, then the axiom of choice is true.[9] Thus the two assertions are equivalent.

See also

[edit]- Basis of a matroid

- Basis of a linear program

- Coordinate system

- Change of basis – Coordinate change in linear algebra

- Frame of a vector space – Similar to the basis of a vector space, but not necessarily linearly independent

- Spherical basis – Basis used to express spherical tensors

Notes

[edit]- ^ Halmos, Paul Richard (1987). Finite-Dimensional Vector Spaces (4th ed.). New York: Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-387-90093-3.

- ^ Hamel 1905

- ^ Note that one cannot say "most" because the cardinalities of the two sets (functions that can and cannot be represented with a finite number of basis functions) are the same.

- ^ Rees, Elmer G. (2005). Notes on Geometry. Berlin: Springer. p. 7. ISBN 978-3-540-12053-7.

- ^ Kuczma, Marek (1970). "Some remarks about additive functions on cones". Aequationes Mathematicae. 4 (3): 303–306. doi:10.1007/BF01844160. S2CID 189836213.

- ^ Igelnik, B.; Pao, Y.-H. (1995). "Stochastic choice of basis functions in adaptive function approximation and the functional-link net". IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 6 (6): 1320–1329. doi:10.1109/72.471375. PMID 18263425.

- ^ a b c Gorban, Alexander N.; Tyukin, Ivan Y.; Prokhorov, Danil V.; Sofeikov, Konstantin I. (2016). "Approximation with Random Bases: Pro et Contra". Information Sciences. 364–365: 129–145. arXiv:1506.04631. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2015.09.021. S2CID 2239376.

- ^ Artstein, Shiri (2002). "Proportional concentration phenomena of the sphere" (PDF). Israel Journal of Mathematics. 132 (1): 337–358. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.417.2375. doi:10.1007/BF02784520. S2CID 8095719.

- ^ Blass 1984

References

[edit]General references

[edit]- Blass, Andreas (1984), "Existence of bases implies the axiom of choice" (PDF), Axiomatic set theory, Contemporary Mathematics volume 31, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, pp. 31–33, ISBN 978-0-8218-5026-8, MR 0763890

- Brown, William A. (1991), Matrices and vector spaces, New York: M. Dekker, ISBN 978-0-8247-8419-5

- Lang, Serge (1987), Linear algebra, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-96412-6

Historical references

[edit]- Banach, Stefan (1922), "Sur les opérations dans les ensembles abstraits et leur application aux équations intégrales (On operations in abstract sets and their application to integral equations)" (PDF), Fundamenta Mathematicae (in French), 3: 133–181, doi:10.4064/fm-3-1-133-181, ISSN 0016-2736

- Bolzano, Bernard (1804), Betrachtungen über einige Gegenstände der Elementargeometrie (Considerations of some aspects of elementary geometry) (in German)

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1969), Éléments d'histoire des mathématiques (Elements of history of mathematics) (in French), Paris: Hermann

- Dorier, Jean-Luc (1995), "A general outline of the genesis of vector space theory", Historia Mathematica, 22 (3): 227–261, doi:10.1006/hmat.1995.1024, MR 1347828

- Fourier, Jean Baptiste Joseph (1822), Théorie analytique de la chaleur (in French), Chez Firmin Didot, père et fils

- Grassmann, Hermann (1844), Die Lineale Ausdehnungslehre - Ein neuer Zweig der Mathematik (in German), reprint: Hermann Grassmann. Translated by Lloyd C. Kannenberg. (2000), Extension Theory, Kannenberg, L.C., Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-2031-5

- Hamel, Georg (1905), "Eine Basis aller Zahlen und die unstetigen Lösungen der Funktionalgleichung f(x+y)=f(x)+f(y)", Mathematische Annalen (in German), 60 (3), Leipzig: 459–462, doi:10.1007/BF01457624, S2CID 120063569

- Hamilton, William Rowan (1853), Lectures on Quaternions, Royal Irish Academy

- Möbius, August Ferdinand (1827), Der Barycentrische Calcul : ein neues Hülfsmittel zur analytischen Behandlung der Geometrie (Barycentric calculus: a new utility for an analytic treatment of geometry) (in German), archived from the original on 2009-04-12

- Moore, Gregory H. (1995), "The axiomatization of linear algebra: 1875–1940", Historia Mathematica, 22 (3): 262–303, doi:10.1006/hmat.1995.1025

- Peano, Giuseppe (1888), Calcolo Geometrico secondo l'Ausdehnungslehre di H. Grassmann preceduto dalle Operazioni della Logica Deduttiva (in Italian), Turin

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit]- Instructional videos from Khan Academy

- "Linear combinations, span, and basis vectors". Essence of linear algebra. August 6, 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17 – via YouTube.

- "Basis", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

Basis (linear algebra)

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Definition

In linear algebra, a basis for a vector space over a field is a set of vectors in that is linearly independent and spans . This means that every vector in can be expressed as a finite linear combination of elements from , with coefficients in , and such a representation is unique for each vector in .[11][12] Linear independence of ensures that no vector in can be written as a linear combination of the other vectors in , while the spanning property guarantees that the linear combinations of vectors in generate all of . The uniqueness of the representation follows directly from the linear independence of , as any two distinct linear combinations equaling the same vector would imply a nontrivial linear dependence relation among the basis vectors.[11][13] The dimension of the vector space , denoted , is defined as the cardinality (number of elements) of any basis for ; all bases for have the same cardinality. In the finite-dimensional case, where , a basis is often denoted as , with each a vector in .[14][6]Properties

A set of vectors in a vector space over a field is a basis if and only if it is linearly independent and spans . Equivalently, if is known, then is a basis if it spans and has exactly elements.[15] In a finite-dimensional vector space , all bases have the same number of elements; this common number is the dimension of , denoted . This invariance of dimension follows from the Steinitz exchange lemma, which establishes that the sizes of bases are uniquely determined.[15] Any linearly independent set in a vector space can be extended to a basis of . In the finite-dimensional case, this is achieved by iteratively applying the Steinitz exchange lemma to add vectors from a spanning set until a basis is obtained. For the general case, the extension relies on Zorn's lemma applied to the partially ordered set of linearly independent supersets, ensuring a maximal linearly independent set exists, which must then span .[15] The Steinitz exchange lemma provides a key tool for proving dimension invariance. Suppose is a linearly independent subset of and is a spanning set for , with . Then there exist indices such that spans . Intuitively, this lemma allows "exchanging" elements from the spanning set with those from the independent set without losing the spanning property, preserving the size while incorporating the independent vectors; repeated application shows that no linearly independent set can exceed the size of a spanning set, equating basis cardinalities.[15] As an application, if and are subspaces of a vector space such that is their internal direct sum, then . This follows by taking bases for and , which combine to form a basis for the direct sum.[15]Examples

Finite-Dimensional Cases

In finite-dimensional vector spaces, bases provide explicit sets of vectors that span the space while remaining linearly independent. A prototypical example is the standard basis for the Euclidean space , consisting of the vectors , , up to . These vectors span because any vector can be expressed as the linear combination . Their linear independence follows from the fact that the only solution to is , as this equation yields the system for each .[1] Another common finite-dimensional space is the vector space of all polynomials with real coefficients of degree at most , which has dimension . The set forms a basis for , as any polynomial is precisely the linear combination , ensuring spanning. Linear independence holds because if for all , then all coefficients , by the uniqueness of polynomial representations.[16] Bases also arise naturally in the context of matrices. For an matrix with full column rank (i.e., rank ), the columns of form a basis for the column space , a subspace of . Consider the invertible matrix ; its columns and are linearly independent since , and they span because maps onto . Thus, is a basis for .[1] Non-standard bases illustrate the flexibility of basis choice. In , the set serves as a basis: any vector can be written as a linear combination, specifically , confirming spanning. Linear independence is verified by noting that the matrix with these columns, , has determinant .[17] To verify whether a candidate set forms a basis for a finite-dimensional space, two checks are essential: spanning and linear independence. Spanning can be assessed by forming the matrix with the candidate vectors as columns (or rows) and using row reduction to determine if the row-reduced echelon form has a pivot in every row corresponding to the space's dimension, indicating full rank. For linear independence in , arrange the vectors as columns of an matrix and compute its determinant; a nonzero value confirms independence, as the only solution to the homogeneous system is the zero vector.[18][19]Infinite-Dimensional Cases

In infinite-dimensional vector spaces, the concept of a basis, specifically a Hamel basis, introduces significant differences from the finite-dimensional case, primarily due to the requirement that every vector be expressed as a finite linear combination of basis elements. The existence of such bases for arbitrary vector spaces, including infinite-dimensional ones, relies on the axiom of choice.[20] Consider the vector space of all continuous real-valued functions on the interval , equipped with pointwise addition and scalar multiplication. This space admits a Hamel basis only under the axiom of choice, and without it, the existence of an algebraic basis is not guaranteed.[20] The basis, when it exists, is highly pathological, uncountable, and lacks any explicit construction, contrasting sharply with intuitive spanning sets like polynomials or trigonometric functions, which fail to form an algebraic basis because they do not span via finite combinations alone.[21] A more straightforward example is the vector space of all polynomials with real coefficients, which is infinite-dimensional. The set forms a countable Hamel basis for this space: it is linearly independent over , as any finite linear dependence relation for all implies all coefficients , and it spans because every polynomial is a finite linear combination of these monomials.[20] In the sequence space of square-summable real sequences, which is a separable infinite-dimensional Hilbert space, a Hamel basis exists via the axiom of choice but is uncountable and non-constructive.[21] This uncountability arises because any countable set in spans only a countable union of finite-dimensional subspaces, which cannot cover the uncountable dimension of the space.[21] The algebraic Hamel basis differs fundamentally from the orthonormal (Hilbert) basis in such spaces; the latter, like the standard basis where has 1 in the th position and 0 elsewhere, allows representation via convergent infinite series , whereas a Hamel basis mandates finite support in all linear combinations.[20] This restriction poses a core challenge: in infinite dimensions, most elements require only finitely many basis coefficients to be nonzero, limiting the utility of Hamel bases for analysis and preventing the capture of infinite expansions natural to the space's topology.[21]Representation

Coordinates

Given a basis for a finite-dimensional vector space over a field , every vector can be uniquely expressed as a linear combination , where the scalars are called the coordinates of with respect to , denoted .[22] This representation is unique due to the linear independence of the basis vectors.[23] The coordinate map defined by is a linear isomorphism, preserving vector addition and scalar multiplication while providing a bijective correspondence between and the coordinate space .[24] To extract the coordinates, one solves the system of linear equations arising from the linear independence of , typically by expressing in the basis vectors' components if is coordinatized, such as in .[25] For example, consider with basis . To find the coordinates of , solve , yielding the system: Thus, , , so .[22] Linear maps between vector spaces can be represented using coordinates with respect to fixed bases. If is linear with bases for and for , the B-coordinate matrix of is the matrix whose columns are the C-coordinates of for , such that for all .[23] This matrix encodes the action of in the coordinate framework.[25]Change of Basis

In linear algebra, a change of basis refers to the process of expressing vectors and linear operators with respect to a different ordered basis of a vector space, which alters their coordinate representations while preserving the underlying linear structure. This transformation is facilitated by a change of basis matrix, also known as a transition matrix, that linearly maps coordinates from one basis to another. Such changes are essential for simplifying computations, such as diagonalizing matrices or adapting to geometric interpretations./13%3A_Diagonalization/13.02%3A_Change_of_Basis) Consider two ordered bases and for an -dimensional vector space over a field like or . Let denote the coordinate column vector of with respect to . The change of basis matrix from to satisfies . To construct , express the bases as matrices and whose columns are the basis vectors in coordinates with respect to some fixed basis (often the standard basis for ); then . The columns of are the coordinates of the -basis vectors with respect to .[26]/13%3A_Diagonalization/13.02%3A_Change_of_Basis) The formula arises from the equality , where and are the basis matrices. Substituting yields , and solving for the new coordinates gives , confirming . Since and are bases, they are invertible (their columns are linearly independent and span ), so is also invertible; specifically, transforms coordinates from back to . This invertibility ensures the mapping is bijective, reflecting the equivalence of bases.[26]/13%3A_Diagonalization/13.02%3A_Change_of_Basis)[27] For a concrete example in , take the standard basis , so , and a non-standard basis , so The determinant of is , confirming it is a basis. Then . The inverse is Now consider , so . The new coordinates are Verification: . Applying recovers ./13%3A_Diagonalization/13.02%3A_Change_of_Basis)[27] Change of basis also affects representations of linear operators. If is the matrix of a linear operator with respect to basis , then the matrix with respect to is . This similarity transformation preserves eigenvalues, trace, determinant, and other intrinsic properties of , as it merely re-expresses the operator in a new coordinate system. For instance, choosing as eigenvectors of yields a diagonal , simplifying analysis./13%3A_Diagonalization/13.02%3A_Change_of_Basis)[26]Variations

Dual Basis

The dual space of a vector space over a field , denoted , consists of all linear functionals on , which are linear maps from to .[28] The vector space operations on are defined pointwise: for linear functionals and scalars , and for all .[28] Given a basis for , where is the index set with , the dual basis for is defined such that each is the unique linear functional satisfying , the Kronecker delta (which is 1 if and 0 otherwise).[28] This construction ensures that is a basis for , as the functionals are linearly independent and span , mirroring the dimension of .[28] The dual basis provides a natural correspondence between bases of and bases of . Any linear functional can be uniquely expressed in the dual basis as , where the coefficients are determined by evaluating on the original basis vectors.[28] This representation highlights how the dual basis encodes the action of functionals through their values on the primal basis. The duality between and induces a canonical bilinear pairing for and , which is linear in each argument and separates points in the respective spaces.[28] In the finite-dimensional case over , consider with the standard basis , where has a 1 in the -th position and 0 elsewhere.[29] The corresponding dual basis consists of the coordinate functionals defined by , the -th component of .[30] These can be represented as row vectors, with corresponding to the -th standard row vector, satisfying .[30] For instance, any linear functional is then , where , recovering the standard representation .[28]Orthonormal Basis

An orthonormal basis is defined in the context of an inner product space, where it consists of a set of vectors that form a basis and satisfy the orthonormality condition for all , meaning the vectors are pairwise orthogonal and each has unit norm.[31] This geometric structure provides advantages over general bases by preserving lengths and angles through the inner product, facilitating computations in projections and decompositions./09%3A_Inner_product_spaces/9.05%3A_The_Gram-Schmidt_Orthogonalization_procedure) A key method to obtain an orthonormal basis from any linearly independent set in a finite-dimensional inner product space is the Gram-Schmidt process, introduced by Erhard Schmidt in 1907.[32] The algorithm proceeds iteratively as follows: Start with and normalize . For , define to orthogonalize against previous vectors, then set to normalize. This yields as an orthonormal basis spanning the same subspace.[33] For example, consider the basis in with the Euclidean inner product. Apply Gram-Schmidt: , , so . Then , , so . Finally, , , so . The resulting orthonormal basis is .[33] In an orthonormal basis , the coordinates of any vector in the space are given by the Fourier coefficients , so . This representation simplifies orthogonal projections onto subspaces, as the projection of onto the span of is directly without additional computations.[34] A fundamental property is Parseval's identity, which states that for any in a finite-dimensional inner product space with orthonormal basis , . This equality extends the Pythagorean theorem to the entire space, quantifying how the squared norm distributes across basis components.[34] Representative examples illustrate these concepts. In Euclidean space with the standard dot product, the standard orthonormal basis is where has a 1 in the -th position and 0 elsewhere, enabling straightforward coordinate interpretations.[31] In contrast, on the circle with the inner product , the Fourier basis forms an orthonormal basis, where coefficients yield the standard Fourier series expansion.[35]Hamel Basis

A Hamel basis for a vector space over a field is a linearly independent subset such that every element of can be uniquely expressed as a finite linear combination of elements from with coefficients in .[36] This algebraic notion extends the standard basis concept from finite-dimensional spaces but requires only finite sums for spanning, distinguishing it from topological bases that permit infinite series. In infinite-dimensional spaces, such bases often have cardinality exceeding any countable set, potentially reaching the cardinality of the continuum or larger.[37] A classic example arises when considering the real numbers as a vector space over the rational numbers . Here, a Hamel basis exists and must be uncountable, with cardinality equal to that of the continuum, ensuring every real number is a unique finite sum where and .[38] While transcendental numbers like and can be included in such a basis, no explicit construction is known without invoking the axiom of choice, rendering the basis non-constructive.[39] The finiteness condition of Hamel bases—that every vector is a finite linear combination—excludes infinite series expansions, such as those used in power series representations for function spaces, which are instead captured by other basis types in infinite dimensions. In spaces like the Hilbert space or the Banach space of continuous functions on , Hamel bases exhibit pathological properties: they are uncountable and non-measurable with respect to the standard Lebesgue or Borel measures.[40] These features enable the construction of counterexamples in functional analysis, including discontinuous linear functionals and sets lacking the Baire property, highlighting their incompatibility with analytic structures.[41] The Baire category theorem implies that constructive Hamel bases—those explicitly describable or countable—are rare in infinite-dimensional Banach spaces, as any countable candidate would fail to span the space densely due to the completeness of the metric.[42] This non-constructivity underscores why Hamel bases, while algebraically universal, are often avoided in practical analysis of infinite-dimensional examples like sequence or function spaces.Theoretical Aspects

Existence Proof

The existence of a basis in every vector space over a field relies on the axiom of choice (AC). In Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory with AC (ZFC), one standard proof uses Zorn's lemma, an equivalent form of AC. Consider the set of all linearly independent subsets of the vector space , partially ordered by inclusion. For any chain in , the union is linearly independent and thus an upper bound in . By Zorn's lemma, has a maximal element . To show spans , suppose there exists . Then is linearly independent, contradicting maximality of . Hence, is a basis.[43] A direct construction using the well-ordering theorem (another equivalent of AC) well-orders and defines the basis as the set of elements not in the span of all preceding elements in the well-ordering.[44] In the finite-dimensional case, existence follows without AC via induction on the dimension : for , any nonzero vector spans; assuming true for , extend a basis of a hyperplane to the full space by adding a vector outside it, or use Gaussian elimination on a spanning set to find a basis./02%3A_Matrix_Algebra/2.07%3A_Bases) The axiom of choice is necessary: in ZF without AC, "every vector space has a basis" is equivalent to AC. For example, in the basic Fraenkel model (a permutation model of ZF), there exists a vector space over with no basis, as all its linearly independent subsets are finite but the space is infinite-dimensional in a way that prevents spanning. Amorphous sets (infinite sets non-partitionable into two infinite subsets) in such models yield vector spaces like (with amorphous) lacking a Hamel basis, since any basis would induce an infinite partition contradicting amorphousness.[45] Historically, the use of well-ordering to prove basis existence traces to Felix Hausdorff's 1914 work, building on earlier special cases like Georg Hamel's 1905 proof for over .[46]Relation to Modules

In abstract algebra, the concept of a basis extends from vector spaces to modules over a ring , where a free -module is defined as one that possesses a basis. A basis for an -module is a subset such that every element of can be uniquely expressed as a finite linear combination with and only finitely many nonzero, implying linear independence over (no nontrivial relations ).[47] This generalizes the vector space case, where is a field and every module is free.[48] When is the integers , the module is free with the standard basis , where has a 1 in the -th position and zeros elsewhere, allowing unique representations of elements as integer combinations.[49] Similarly, the polynomial ring over a commutative ring is a free -module with basis , of countably infinite rank, as every polynomial has a unique expression in this form.[50] In contrast, not all modules are free; for example, the rational numbers as a -module has no basis, since any two nonzero elements are linearly dependent over (e.g., for integer ), yet is not finitely generated.[51] The rank of a free -module, defined as the cardinality of any basis, serves as an analog to the dimension of a vector space. Over principal ideal domains (PIDs) like or (for field ), the rank is well-defined and invariant, with submodules of free modules also free of rank at most that of the original.[52] However, without PID assumptions—such as over general commutative rings—the invariance of rank for projective modules (a broader class containing free modules) may require additional conditions like localization at prime ideals, though for free modules over commutative rings, bases consistently have the same cardinality.[53]Random Bases

Random bases in linear algebra refer to bases constructed probabilistically, often by sampling vectors from a distribution such as the standard Gaussian and subsequently orthogonalizing them to form an orthonormal basis. A standard method for generating a random orthonormal basis involves forming an matrix with independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) standard normal entries, then computing its QR decomposition , where has orthonormal columns that serve as the random basis vectors.[54] This approach draws from the Haar measure on the orthogonal group, ensuring uniformity over the manifold of orthogonal matrices.[55] Alternatively, random orthonormal bases can be generated directly using products of Householder reflection matrices, where each reflection is defined by a random unit vector, providing an efficient numerical implementation for high dimensions.[54] The properties of random bases, particularly those derived from Gaussian matrices, exhibit notable behavior under probabilistic analysis. The expected condition number of the generating matrix for an real Gaussian random matrix satisfies , implying that grows linearly with on average.[56] This growth reflects the disparity between the largest singular value, which scales as , and the smallest, which scales as .[57] Once orthogonalized to form the basis , the condition number becomes exactly 1, but the original matrix's ill-conditioning can introduce numerical instability during the orthogonalization process, especially under small perturbations, where the basis vectors may deviate significantly from orthogonality.[58] In applications, random bases facilitate Monte Carlo-style approximations of subspaces in high-dimensional settings, such as the randomized range finder algorithm, which computes an approximate orthonormal basis for the column space of a large matrix (with ) by projecting onto a low-dimensional random subspace spanned by a Gaussian matrix and orthogonalizing the result via QR decomposition.[59] This method achieves near-optimal error bounds with high probability, enabling efficient low-rank approximations without full matrix factorizations. However, the curse of dimensionality manifests in random bases for high , where non-orthogonalized random vectors lead to matrices with condition numbers scaling as , exacerbating ill-conditioning and computational sensitivity in numerical tasks.[56]Applications

In Geometry

In Euclidean geometry, a basis for a vector space provides a set of linearly independent directions that span the entire space, allowing any vector to be expressed as a unique linear combination of these basis vectors. Geometrically, these vectors can be visualized as arrows originating from a common point, defining the axes of a coordinate frame; for instance, in three-dimensional space, the standard basis vectors , , and along the x-, y-, and z-axes enable the location of points via their Cartesian coordinates. This framework facilitates the representation of geometric objects, such as lines and planes, by parameterizing them relative to these directions.[60] A change of basis in this geometric context corresponds to reorienting or rescaling these directions, which manifests as transformations like rotations or non-uniform scalings of the coordinate system. For example, rotating the basis vectors by an angle in the plane alters the coordinates of points while preserving distances and angles if the new basis maintains orthogonality and unit length, though general changes may introduce shearing or stretching effects. Such transformations are essential for aligning coordinate frames with specific geometric features, such as rotating axes to simplify the equation of a conic section. The change of basis matrix encapsulates this geometric shift, linking coordinates in the original and new frames.[61] In affine spaces, which generalize Euclidean spaces by incorporating translations without a fixed origin, an affine basis extends the linear basis by including a distinguished point as the "origin," paired with linearly independent vectors that span the translation space. This structure allows for the affine combination of points, where coefficients sum to one, enabling the description of positions and affine transformations like parallel projections. Geometrically, an affine basis defines a frame for measuring displacements and ratios along lines, crucial for concepts in projective geometry without privileging any single point.[62] A practical example arises in coordinate geometry of the plane, where the standard Cartesian basis yields rectangular coordinates . In contrast, polar coordinates provide a nonlinear reparameterization via and , with position-dependent frame vectors suited for circular symmetries, though this is not a fixed linear basis change.[63] The volume of the parallelepiped formed by basis vectors in Euclidean space is given by the absolute value of the determinant of the matrix whose columns (or rows) are these vectors, providing a measure known as the covolume. For instance, if form a basis in -dimensional space, the signed volume is , where is the basis matrix; this quantifies the "scaling factor" of the basis relative to the standard one and remains invariant under certain transformations. Geometrically, it represents the -dimensional content enclosed by the parallelepiped with edges along the basis vectors, zero if the vectors are linearly dependent.[64] In crystallography, lattice bases consist of three linearly independent vectors defining the primitive unit cell of a crystal lattice, capturing the periodic geometric arrangement of atoms in solid materials. These bases generate the Bravais lattice points via integer combinations, with the covolume corresponding to the volume of the unit cell, which determines density and symmetry properties. Such bases enable the classification of crystal structures into 14 Bravais types, essential for understanding material geometries.[65]In Analysis

In functional analysis, the concept of a basis extends beyond the algebraic Hamel basis to account for the topological structure of infinite-dimensional spaces, particularly Banach spaces. A Schauder basis for a Banach space is a sequence such that every can be uniquely represented as an infinite series , where the series converges in the norm of . This definition, introduced by Juliusz Schauder in 1927, emphasizes topological convergence rather than mere algebraic linear combinations, making it suitable for normed spaces where infinite sums must respect the metric structure. In contrast to a Hamel basis, which consists of finite linear combinations and ignores topology, a Schauder basis is inherently tied to the norm topology and is often more practical for analysis, though a Hamel basis may exist algebraically in spaces where no Schauder basis does. While every Hamel basis induces a Schauder basis in finite dimensions, in infinite-dimensional settings, Hamel bases are typically uncountable and lack useful topological properties, rendering them impractical for most analytical purposes. Schauder bases, being countable sequences, align better with separability and allow for the study of convergence behaviors essential in functional analysis.[66] A classic example of a Schauder basis is the trigonometric system in the Hilbert space , where every square-integrable function admits a unique Fourier series expansion that converges in the norm, as established by the Riesz-Fischer theorem. This basis facilitates the decomposition of functions into orthogonal components, underpinning much of harmonic analysis.[66] The existence of Schauder bases in Banach spaces has been a central topic; it was long conjectured that every separable Banach space possesses one, but Per Enflo constructed a counterexample in 1973—a separable Banach space lacking both the approximation property and thus any Schauder basis. For non-separable Banach spaces, counterexamples are even more straightforward, as uncountability often precludes countable bases. However, many important separable spaces, such as spaces for , admit Schauder bases like the Haar system. A refinement of the Schauder basis is the unconditional basis, where the convergence of is independent of rearrangements of the terms, bounded by a constant such that for any choice of signs . This property, stronger than mere conditional convergence, ensures robustness under permutations and is crucial for applications in operator theory and approximation. In Hilbert spaces, orthonormal bases are automatically unconditional Schauder bases.[67]Computational Aspects

In numerical linear algebra, Gaussian elimination serves as a core method for extracting bases from a matrix by transforming it into row echelon form (REF) or reduced row echelon form (RREF). For the column space, the columns of the original matrix corresponding to the pivot positions in the REF provide a basis, as these columns are linearly independent and span the same space. For the null space, solving the homogeneous system from the RREF yields a basis consisting of the special solutions—vectors that capture the free variables. This process, equivalent to Gauss-Jordan elimination, is implemented efficiently in software and preserves the dimensions of the spaces involved.[68][69] The QR decomposition offers a stable alternative for computing an orthonormal basis specifically for the column space. It factors a matrix as , where is an orthogonal matrix () and is upper triangular; the first columns of (with ) then form the desired orthonormal basis, orthogonalizing the original columns via Gram-Schmidt or Householder reflections. This approach enhances numerical reliability over direct pivoting in Gaussian elimination for tall, skinny matrices, avoiding column swaps that could amplify errors.[70][71] Singular value decomposition (SVD) extends these ideas for rank-revealing purposes, decomposing where and are orthogonal, and is diagonal with singular values . The leading left singular vectors (columns of ) provide an orthonormal basis for the column space, while the singular values quantify the "strength" of each basis direction, aiding in low-rank approximations and numerical rank estimation via thresholds on small . SVD is particularly valuable for ill-conditioned matrices, as it isolates the effective rank from noise.[72][73] A practical example of basis extraction appears in Python's NumPy library, where QR decomposition can yield an orthonormal column space basis:import numpy as np

A = np.array([[1.0, 2.0, 3.0], [4.0, 5.0, 6.0], [7.0, 8.0, 9.0]]).T # Example 3x3 matrix

Q, R = np.linalg.qr(A)

r = np.linalg.matrix_rank(A)

orthonormal_basis = Q[:, :r]

print(orthonormal_basis)

import numpy as np

A = np.array([[1.0, 2.0, 3.0], [4.0, 5.0, 6.0], [7.0, 8.0, 9.0]]).T # Example 3x3 matrix

Q, R = np.linalg.qr(A)

r = np.linalg.matrix_rank(A)

orthonormal_basis = Q[:, :r]

print(orthonormal_basis)