Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Professor

View on Wikipedia

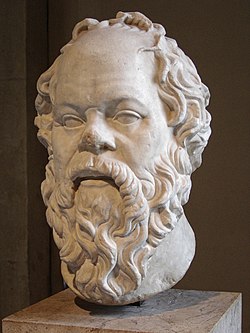

Albert Einstein as a professor | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Professor |

Occupation type | Education, research, teaching |

Activity sectors | Academics |

| Description | |

| Competencies | Academic knowledge, research, writing journal articles or book chapters, teaching |

Education required | Master's degree, doctoral degree (e.g., PhD), professional degree, or other terminal degree |

Fields of employment | Academics |

Related jobs | Teacher, lecturer, reader, researcher |

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.)[1] is an academic rank at universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, professor derives from Latin as a 'person who professes'. Professors are usually experts in their field and teachers of the highest rank.[1]

In most systems of academic ranks, "professor" as an unqualified title refers only to the most senior academic position, sometimes informally known as "full professor".[2][3] In some countries and institutions, the word professor is also used in titles of lower ranks such as associate professor and assistant professor; this is particularly the case in the United States, where the unqualified word is also used colloquially to refer to associate and assistant professors as well, and often to instructors or lecturers.[4]

Professors often conduct original research and commonly teach undergraduate, postgraduate, or professional courses in their fields of expertise. In universities with graduate schools, professors may mentor and supervise graduate students conducting research for a thesis or dissertation. In many universities, full professors take on senior managerial roles such as leading departments, research teams and institutes, and filling roles such as president, principal or vice-chancellor.[5] The role of professor may be more public-facing than that of more junior staff, and professors are expected to be national or international leaders in their field of expertise.[5]

Etymology

[edit]

The term professor was first used in the late 14th century to mean 'one who teaches a branch of knowledge'.[1] The word comes "...from Old French professeur" (14c.) and directly from [the] Latin professor[, for] 'person who professes to be an expert in some art or science; teacher of highest rank'; the Latin term came from the "...agent noun from profiteri" 'lay claim to, declare openly'. As a title that is "prefixed to a name, it dates from 1706". The "[s]hort form prof is recorded from 1838". The term professor is also used with a different meaning: "[o]ne professing religion. This canting use of the word comes down from the Elizabethan period, but is obsolete in England."[1]

Description

[edit]A professor is an accomplished and recognized academic. In most Commonwealth nations, as well as northern Europe, the title professor is the highest academic rank at a university. In the United States and Canada, the title of professor applies to most post-doctoral academics, so a larger percentage are thus designated. In these areas, professors are scholars with doctorate degrees (typically PhD degrees) or equivalent qualifications who teach in colleges and universities. An emeritus professor is a title given to selected retired professors with whom the university wishes to continue to be associated due to their stature and ongoing research. Emeritus professors do not receive a salary, but they are often given office or lab space, and use of libraries, labs, and so on.[7][8]

The term professor is also used in the titles assistant professor and associate professor,[9] which are not considered professor-level positions in all European countries. In Australia, the title associate professor is used in place of the term reader as used in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries; ranking above senior lecturer and below full professor.[10]

Beyond holding the proper academic title, universities in many countries also give notable artists, athletes and foreign dignitaries the title honorary professor, even if these persons do not have the academic qualifications typically necessary for professorship and they do not take up professorial duties. However, such "professors" usually do not undertake academic work for the granting institution. In general, the title of professor is strictly used for academic positions rather than for those holding it on honorary basis.

Tasks

[edit]

Professors are qualified experts in their field who generally perform some or all the following tasks:[11][12]

- Managing teaching, research, and publications in their departments (in countries where a professor is head of a department);

- Presenting lectures and seminars in their specialties (i.e., they "profess");

- Performing, leading and publishing advanced original research in peer reviewed journals in their fields;

- Providing community service, including consulting functions (such as advising government and nonprofit organizations) or providing expert commentary on TV or radio news or public affairs programs;

- Mentoring graduate students in their academic training;

- Mentoring more junior academic staff;

- Conducting administrative or managerial functions, usually at a high level (e.g. deans, heads of departments, research centers, etc.); and

- Assessing students in their fields of expertise (e.g., through grading examinations or viva voce defenses).

Other roles of professorial tasks depend on the institution, its legacy, protocols, place (country), and time. For example, professors at research-oriented universities in North America and, generally, at European universities, are promoted primarily on the basis of research achievements and external grant-raising success.

Around the world

[edit]| Academic ranks worldwide |

|---|

Many colleges and universities and other institutions of higher learning throughout the world follow a similar hierarchical ranking structure amongst scholars in academia; the list above provides details.

Salary

[edit]

A professor typically earns a base salary and a range of employee benefits. In addition, a professor who undertakes additional roles in their institution (e.g., department chair, dean, head of graduate studies, etc.) sometimes earns additional income. Some professors also earn additional income by activities such as consulting, publishing academic or other books, giving speeches, or coaching executives. Some fields (e.g., business and computer science) give professors more opportunities for outside work.

Germany and Switzerland

[edit]A report from 2005 by the "Deutscher Hochschulverband DHV",[13] a lobby group for German professors, the salary of professors, the annual salary of a German professor is €46,680 in group "W2" (mid-level) and €56,683 in group "W3" (the highest level), without performance-related bonuses. The anticipated average earnings with performance-related bonuses for a German professor is €71,500. The anticipated average earnings of a professor working in Switzerland vary for example between 158,953 CHF (€102,729) to 232,073 CHF (€149,985) at the University of Zurich and 187,937 CHF (€121,461) to 247,280 CHF (€159,774) at the ETH Zurich; the regulations are different depending on the Cantons of Switzerland.

Italy

[edit]As of 2021[update], in the Italian universities there are about 18 thousand Assistant Professors, 23 thousand Associate Professors, and 14 thousand Full Professors. The role of "professore a contratto" (the equivalent of an "adjunct professor"), a non-tenured position which does not require a PhD nor any habilitation but requires a public academic competition (in which the PhD title is a preferential qualification), is paid at the end of the academic year nearly €3000 for the entire academic year,[14] without salary during the academic year.[15] There are about 28 thousand "Professori a contratto" in Italy.[16] Associate Professors have a gross salary in between 52.937,59 and 96.186,12 euros per year, Full Professors have a gross salary in between 75.431,76 and 131.674 Euros per year, and adjunct professors of around 3,000 euros per year.[17]

As of 2025 in the Italian universities there are: 16,574 Full Professors 26,472 Associate Professors with salary and 33,535 "Professori a contratto" without salary.[16]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]According to World Salaries 2023, the salary of a professor in any public university is 447,300 SAR, or 119,217.18 USD[18]

Spain

[edit]The salaries of civil servant professors in Spain are fixed on a nationwide basis, but there are some bonuses related to performance and seniority and a number of bonuses granted by the Autonomous Regional governments. These bonuses include three-year premiums (Spanish: trienios, according to seniority), five-year premiums (quinquenios, according to compliance with teaching criteria set by the university) and six-year premiums (sexenios, according to compliance with research criteria laid down by the national government). These salary bonuses are relatively small. Nevertheless, the total number of sexenios is a prerequisite for being a member of different committees.

The importance of these sexenios as a prestige factor in the university was enhanced by legislation in 2001 (LOU). Some indicative numbers can be interesting, in spite of the variance in the data. We report net monthly payments (after taxes and social security fees), without bonuses: Ayudante, €1,200; Ayudante Doctor, €1,400; Contratado Doctor; €1,800; Profesor Titular, €2,000; Catedrático, €2,400. There are a total of 14 payments per year, including 2 extra payments in July and December (but for less than a normal monthly payment).

United States

[edit]Professors in the United States commonly occupy any of several positions in academia. In the U.S., the word "professor" informally refers collectively to the academic ranks of assistant professor, associate professor, or professor. This usage differs from the predominant usage of the word "professor" internationally, where the unqualified word "professor" only refers to full professors. The majority of university lecturers and instructors in the United States, as of 2015[update], do not occupy these tenure-track ranks, but are part-time adjuncts.[19]

Table of wages

[edit]In 2007 the Dutch social fund for the academic sector SoFoKleS[20] commissioned a comparative study of the wage structure of academic professions in the Netherlands in relation to that of other countries. Among the countries reviewed are the United States, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, France, Sweden and the Netherlands. To improve comparability, adjustments have been made to correct for purchasing power and taxes. Because of differences between institutions in the US and UK these countries have two listings of which one denotes the salary in top-tier institutions (based on the Shanghai-ranking).

The table below shows the final reference wages (per year) expressed in net amounts of Dutch euros in 2014 (i.e., converted into Dutch purchasing power).[21]

| Country | Assistant professor | Associate professor | Full professor |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | €46,475 | €52,367 | €77,061 |

| United States – top universities | €59,310 | €68,429 | €103,666 |

| United Kingdom | €36,436 | €44,952 | €60,478 |

| United Kingdom – top universities | €39,855 | €45,235 | €84,894 |

| Germany | €33,182 | €42,124 | €47,894 |

| France | €24,686 | €30,088 | €38,247 |

| Netherlands | €34,671 | €42,062 | €50,847 |

| Switzerland | €78,396 | €89,951 | €101,493 |

| Belgium | €32,540 | €37,429 | €42,535 |

| Sweden | €30,005 | €35,783 | €42,357 |

| Norway | €34,947 | €37,500 | €45,113 |

Research professor

[edit]In a number of countries, the title "research professor" refers to a professor who is exclusively or mainly engaged in research, and who has few or no teaching obligations. For example, the title is used in this sense in the United Kingdom (where it is known as a research professor at some universities and professorial research fellow at some other institutions) and in northern Europe. A research professor is usually the most senior rank of a research-focused career pathway in those countries and is regarded as equal to the ordinary full professor rank. Most often they are permanent employees, and the position is often held by particularly distinguished scholars; thus the position is often seen as more prestigious than an ordinary full professorship. The title is used in a somewhat similar sense in the United States, with the exception that research professors in the United States are often not permanent employees and often must fund their salary from external sources,[22] which is usually not the case elsewhere.

In fiction

[edit]Traditional fictional portrayals of professors, in accordance with a stereotype, are shy, absent-minded individuals often lost in thought. In many cases, fictional professors are socially or physically awkward. Examples include the 1961 film The Absent-Minded Professor or Professor Calculus of The Adventures of Tintin stories. Professors have also been portrayed as being misguided into an evil pathway, such as Professor Metz, who helped Bond villain Blofeld in the film Diamonds Are Forever; or simply evil, like Professor Moriarty, archenemy of British detective Sherlock Holmes. The modern animated series Futurama has Professor Hubert Farnsworth, a typical absent-minded but genius-level professor. A related stereotype is the mad scientist.

Vladimir Nabokov, author and professor of English at Cornell, frequently used professors as the protagonists in his novels. Professor Henry Higgins is a main character in George Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion. In the Harry Potter series, set at the wizard school Hogwarts, the teachers are known as professors, many of whom play important roles, notably Professors Dumbledore, McGonagall and Snape. In the board game Cluedo, Professor Plum has been depicted as an absent-minded academic. Christopher Lloyd played Plum's film counterpart, a psychologist who had an affair with one of his patients.

Since the 1980s and 1990s, various stereotypes were re-evaluated, including professors. Writers began to depict professors as just normal human beings and might be quite well-rounded in abilities, excelling both in intelligence and in physical skills. An example of a fictional professor not depicted as shy or absent-minded is Indiana Jones, a professor as well as an archeologist-adventurer, who is skilled at both scholarship and fighting. The popularity of the Indiana Jones movie franchise had a significant impact on the previous stereotype, and created a new archetype which is both deeply knowledgeable and physically capable.[23] The character generally referred to simply as the Professor on the television sitcom series, Gilligan's Island, although described alternatively as a high-school science teacher or research scientist, is depicted as a sensible advisor, a clever inventor, and a helpful friend to his fellow castaways. John Houseman's portrayal of law school professor Charles W. Kingsfield, Jr., in The Paper Chase (1973) remains the epitome of the strict, authoritarian professor who demands perfection from students. Annalise Keating (played by Viola Davis) from the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) legal drama mystery television series How to Get Away with Murder is a law professor at the fictional Middleton University.[24] Early in the series, Annalise is a self-sufficient and confident woman, respected for being a great law professor and a great lawyer, feared and admired by her students,[25] whose image breaks down as the series progresses.[26] Sandra Oh stars as an English professor, Ji-Yoon Kim, recently promoted to the role of department chair in the 2021 Netflix series The Chair. The series includes her character's negotiation of liberal arts campus politics, in particular issues of racism, sexism, and social mores.[27]

Mysterious, older men with magical powers (and unclear academic standing) are sometimes given the title of "Professor" in literature and theater. Notable examples include Professor X in the X-Men franchise, Professor Marvel in The Wizard of Oz[28] and Professor Drosselmeyer (as he is sometimes known) from the ballet The Nutcracker. Also, the magician played by Christian Bale in the film The Prestige[29] adopts 'The Professor' as his stage name. A variation of this type of non-academic professor is the "crackpot inventor", as portrayed by Professor Potts in the film version of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang or the Jerry Lewis-inspired Professor Frink character on The Simpsons. Other professors of this type are the thoughtful and kind Professor Digory Kirke of C. S. Lewis's Chronicles of Narnia.

Non-academic usage

[edit]The title has been used by comedians, such as "Professor" Irwin Corey and Soupy Sales in his role as "The Big Professor". In the past, pianists in saloons and other rough environments have been called "professor".[30] The puppeteer of a Punch and Judy show is also traditionally known as "Professor".[31] Aside from such examples in the performing arts, one apparently novel example is known where the title of professor has latterly been applied to a college appointee with an explicitly "non-academic role", which seems to be primarily linked to claims of "strategic importance".[32]

See also

[edit]- Academic discipline

- Adjunct professor

- Sacrae Theologiae Professor (S.T.P.) – degree now awarded as S.T.D. or Doctor of Divinity (D.D.)

- Emeritus

- Habilitation

- Scholarly method

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Harper, Douglas. "Professor". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ^ Pettigrew, Todd (17 June 2011). "Assistant? Associate? What the words before "professor" mean: Titles may not mean what you think they do". Maclean's. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ^ "United Kingdom, Academic Career Structure". European University Institute. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Hartley, Tom (26 January 2013). "Dr Who or Professor Who? On Academic Email Etiquette". Tom Hartley. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Promoted from doctor to professor: what changes?". Times Higher Education. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- ^ David K. Knox "Socrates: The First Professor" Innovative Higher Education December 1998, Volume 23, Issue 2, pp 115–126

- ^ "Difference Between a Teacher and a Professor". Western Governors University. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ van Dijk, Esther E.; van Tartwijk, Jan; van der Schaaf, Marieke F.; Kluijtmans, Manon (1 November 2020). "What makes an expert university teacher? A systematic review and synthesis of frameworks for teacher expertise in higher education" (PDF). Educational Research Review. 31 100365. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100365. ISSN 1747-938X.

- ^ "Associate Professor – definition of associate professor". Free Online Dictionary. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "Australia, Academic Career Structure". European University Institute. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Difference Between a Teacher and a Professor". Western Governors University. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "What exactly is a professor these days?". Times Higher Education (THE). 13 November 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Deutscher Hochschulverband". Hochschulverband.de. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "University L'Orientale of Naples – table of annual fees for contract professors" (PDF).

- ^ Monella, Lillo Montalto (26 January 2018). "Essere professore a contratto all'università...per 3,75 euro l'ora". euronews (in Italian). Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Esplora i dati". USTAT. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Salary Sapienza University of Rome Italy (in Italian) Tabella stipendi personale Docente". Sapienza Università di Roma. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Average Professor – Education Salary in Saudi Arabia for 2023". World Salaries. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ "COE – Characteristics of Postsecondary Faculty". National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "SoFoKleS | Sociaal Fonds voor de KennisSector". Sofokles.nl. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ SEO Economic Research (23 September 2015). "International wage differences in academic occupations" (PDF). Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- ^ Classification of Ranks and Titles.

- ^ Hiscock, Peter (2012). "Cinema, Supernatural Archaeology, and the Hidden Human Past". Numen. 59 (2/3): 156–177. doi:10.1163/156852712X630761. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 23244957.

- ^ "Viola Davis as Annalise Keating". ABC. The Walt Disney Company. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Kumari Upadhyaya, Kayla (25 September 2014). "How To Get Away With Murder: "Pilot"". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Kumari Upadhyaya, Kayla (23 October 2015). "A new lie has consequences for everyone on How To Get Away With Murder". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Dettmar, Kevin (2 September 2021). "What 'The Chair' Gets Unexpectedly Right About the Ivory Tower". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "The Wizard of Oz (1939)". IMDb. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "The Prestige (2006)". IMDb. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ "Music: Machines & Musicians". Time. 30 August 1937. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "A working life: The Punch and Judy man". the Guardian. 22 August 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "REINFORCEMENTS!". Union Theological College, Belfast. 26 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

External links

[edit] Media related to Professors at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Professors at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Professor at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Professor at Wikiquote The dictionary definition of professor at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of professor at Wiktionary

Professor

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Historical Origins

The term "professor" derives from the Latin professor, an agent noun formed from the verb profiteri, meaning "to declare publicly" or "to profess," emphasizing the act of openly avowing and imparting knowledge.[4] This etymology underscores the public nature of teaching in early academia, where instructors formally declared expertise to students and the community. The concept emerged in the context of 13th-century European universities, such as the University of Bologna (established around 1088) and the University of Paris (formalized by the mid-12th century but thriving by the 13th), where scholars publicly lectured on civil and canon law, theology, and liberal arts as part of guild-like associations of masters and students. During the Renaissance (14th–17th centuries), the role of the professor evolved amid the revival of classical learning and the expansion of higher education. Professors increasingly functioned as salaried public lecturers in key disciplines like law, medicine, and theology, often at institutions influenced by humanist reforms that prioritized rigorous textual analysis and disputation. A pivotal influence came from religious orders, notably the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola, whose members established colleges and universities across Europe and beyond, training professors to integrate faith with scholarly instruction in subjects ranging from humanities to sciences.[11] The English adoption of "professor" as a formal title occurred in the 16th century, aligning with royal endowments that professionalized academia; for instance, King Henry VIII created the first Regius Professorships at Oxford and Cambridge in the 1540s for fields like divinity, civil law, and Greek, marking a shift toward dedicated, state-supported teaching positions.[6] By the 18th century, the title gained structured formality in German-speaking universities, where distinctions such as ordentlicher Professor (ordinary or full professor, with administrative duties and salary) and außerordentlicher Professor (extraordinary or associate professor, often without chair) codified a hierarchical system that influenced modern academic ranks.[12]Contemporary Definitions

In contemporary higher education, a professor is defined as a senior academic rank held by individuals with established expertise in a specific field, typically requiring an earned doctoral degree or terminal qualification, and encompassing responsibilities in teaching, research, and institutional service. This rank signifies a position of leadership and autonomy within academia, where professors contribute to advancing knowledge through scholarly activities while mentoring students and shaping departmental directions.[7][13][14] The title of professor is distinguished from lower ranks such as associate professor, which represents a mid-level tenured position often involving national scholarly recognition and broader service roles but without the full leadership authority of a full professor; assistant professor, an entry-level tenure-track role focused on building a research portfolio; lecturer, a teaching-oriented position usually without tenure eligibility and emphasizing instructional duties over research; and instructor, an initial rank typically requiring only a master's degree and centered on classroom teaching. Professors, in particular, exercise greater autonomy in curriculum design, research agendas, and academic governance, positioning them as principal investigators and departmental influencers.[15][16][17] Institutionally, organizations like the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) define professors as full-time faculty eligible for tenure, with appointments involving sustained excellence in teaching, research, and service, and a probationary period not exceeding seven years leading to continuous tenure. This framework ensures job security and academic freedom for professors as core members of the instructional-research staff.[18] In the 21st century, the concept of professorship has evolved to encompass interdisciplinary roles that integrate multiple fields to address complex global challenges, reflecting a shift from siloed disciplines to collaborative approaches central to modern higher education. Additionally, the rise of online learning has expanded professorships to include virtual platforms, where professors deliver courses, conduct remote research collaborations, and engage in digital pedagogy, driven by technological advancements and increased accessibility since the early 2000s.[19][20][21]Role and Responsibilities

Teaching Obligations

Professors bear primary responsibility for delivering classroom instruction through lecturing, where they present complex subject matter to undergraduate and graduate students, often integrating multimedia aids and interactive elements to enhance comprehension.[22] This core duty extends to grading assignments, exams, and projects, providing timely and constructive feedback to guide student improvement, as outlined in university faculty handbooks.[23] Additionally, professors maintain regular office hours to offer personalized support, addressing questions on course content or academic planning, and they advise students on theses or dissertations, particularly at the graduate level, by overseeing research progress and defending scholarly work.[24] Preparation forms a foundational aspect of these obligations, involving the development of syllabi that outline learning objectives, policies, and timelines, alongside creating course materials such as readings, slides, and problem sets tailored to foster critical thinking skills like analysis and synthesis.[23] Assessments are designed to evaluate not only knowledge retention but also application and evaluation abilities, with professors emphasizing assignments that encourage independent reasoning over rote memorization.[24] This preparation ensures courses remain current and relevant, often incorporating recent scholarly insights to bridge theoretical concepts with practical applications, including ethical considerations for emerging technologies like artificial intelligence in education.[25] Professors adapt their teaching to diverse formats, including seminars that promote discussion-based learning, laboratory sessions requiring hands-on demonstrations and safety oversight, and online classes utilizing platforms for virtual interactions.[22] Post-2020, the shift to remote teaching accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic led to widespread adoption of asynchronous videos, proctored assessments, and collaborative tools like video conferencing with annotations to replicate in-person engagement in labs and seminars.[26] These adaptations prioritize equitable access, such as providing recorded lectures for students in different time zones, and by 2025, hybrid models integrating AI-assisted tools for personalized learning have become standard in many institutions.[27] Ethical considerations underpin all teaching duties, with professors enforcing academic integrity by clearly communicating expectations in syllabi, detecting plagiarism through tools and policies, and promoting honest scholarship as essential for personal and professional growth.[28] Inclusive practices are equally vital, involving the creation of accessible materials, diverse perspectives in curricula, and supportive environments that accommodate varied learning needs and backgrounds to ensure all students can thrive.[24]Research and Publication Duties

Professors are expected to engage in original research within their academic field, often allocating around 40% of their workload to scholarly inquiry in research-intensive institutions, with variations by rank, field, and institution—for pre-tenure faculty, this supports progression toward tenure.[22][29] This research may be conducted independently to demonstrate intellectual autonomy, such as through sole or senior authorship on key outputs, or collaboratively with peers, institutions, or interdisciplinary teams to address complex problems.[29][30] For promotion to higher ranks like associate or full professor, institutions require evidence of high-quality, original contributions that gain external recognition, with independence emphasized to show progression beyond mentored work.[30][29] Publication remains a cornerstone of professorial research duties, with expectations centered on disseminating findings through peer-reviewed outlets to establish impact and credibility. Common formats include journal articles in reputable venues, scholarly books from academic presses, and conference papers, particularly in fields like computer science where proceedings hold significant weight.[31] For tenure (to associate professor), benchmarks often involve 4-12 peer-reviewed articles over 5-7 years, depending on discipline (e.g., 3-5 in humanities, 6-8 in social sciences), while promotion to full professor may require 10-20 additional high-impact publications; requirements vary by institution and prioritize quality and influence over volume.[32][33] Metrics such as the h-index, which measures an author's productivity and citation impact—for instance, an h-index of 10 indicates 10 papers each cited at least 10 times—are increasingly used in evaluations to quantify scholarly reach.[34][35] As of 2025, open-access publishing is often mandated for federally funded research in the US, promoting broader dissemination.[36] Securing external funding is a critical responsibility for professors, often essential for sustaining research programs and meeting institutional benchmarks for promotion. In the United States, professors submit proposals to agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF), which require a one-page project summary highlighting intellectual merit and broader impacts, a detailed 15-page project description outlining methods and goals, a budget justification, and supplementary plans for data management and mentoring.[37] The process involves adhering to the NSF's Proposal and Award Policies and Procedures Guide, with submissions evaluated for feasibility and innovation.[38] In Europe, similar proposals to the European Research Council (ERC) include administrative forms, a research proposal detailing the project's excellence and feasibility, and supplementary documents like CVs, submitted through the EU's Funding and Tenders Portal.[39] These grant-writing efforts not only fund research but also signal a professor's ability to compete at national and international levels.[40] Intellectual property arising from university research poses key considerations for professors, particularly regarding ownership and commercialization of discoveries. Under policies at institutions like Stanford University, inventions conceived or developed using university resources or during faculty duties are owned by the university, which discloses, patents, and licenses them on behalf of inventors.[41] Harvard University similarly claims ownership of "supported inventions" funded by or created with significant institutional resources, requiring faculty to disclose potential IP to the Office of Technology Development for patent evaluation and protection.[42] Royalties from successful patenting are shared, with inventors typically receiving around 33-35% after the first few million dollars, incentivizing faculty to pursue patentable innovations while aligning with university missions.[41][42]Administrative and Community Service

Professors often engage in administrative duties that support institutional governance, including participation in committees responsible for hiring new faculty, approving curricula, and ensuring accreditation standards are met. For instance, faculty members typically serve on search committees to evaluate candidates for academic positions, contributing their expertise to maintain departmental quality and diversity. They also review and approve course proposals and program changes through curriculum committees, ensuring alignment with educational goals and regulatory requirements. Additionally, professors contribute to accreditation processes by preparing reports and participating in site visits for bodies like regional accrediting agencies. These roles are essential for shared governance in universities, where faculty input helps shape institutional policies and operations.[43][44] Beyond internal administration, professors mentor junior faculty, guiding them through tenure processes, research development, and career advancement, which fosters a supportive academic environment. They also play key roles in university policy development, such as drafting guidelines for academic integrity, diversity initiatives, or resource allocation during budget reviews. Service to professional organizations involves holding leadership positions, organizing conferences, or reviewing grants and manuscripts for scholarly societies, enhancing the broader academic community's standards and collaboration. These contributions extend professors' influence beyond their institutions, promoting ethical practices and innovation in their fields.[45][46] Public engagement forms a significant aspect of professors' community service, encompassing public lectures, consulting for non-academic entities, and involvement in community programs that apply scholarly expertise to societal issues. For example, faculty may deliver keynote addresses at civic events or advise policymakers on topics like environmental sustainability or public health, bridging academia and real-world applications. Community programs often include service-learning initiatives where professors collaborate with local organizations to address needs such as education access or economic development. This outreach not only disseminates knowledge but also enriches professors' perspectives through diverse interactions.[47][48] Balancing these service demands with research and teaching obligations presents ongoing challenges, often exacerbated by the "publish or perish" culture prevalent in academia. While service is valued for institutional health, excessive committee work or mentoring responsibilities can reduce time for scholarly output, leading to stress and potential career setbacks in tenure evaluations. Institutions increasingly recognize this tension, with some implementing workload policies to allocate specific time for service, aiming to sustain faculty well-being and productivity. Global variations exist, such as higher service expectations in European systems emphasizing collegial decision-making.[49][50]Academic Ranks and Qualifications

Tenure-Track Hierarchy

The tenure-track hierarchy represents the traditional pathway for academic faculty in many universities, particularly in North America, structured as a progressive ladder from entry-level to senior positions. The entry point is typically the rank of assistant professor, an initial tenure-track appointment for new PhD holders or equivalent, lasting approximately 5 to 7 years during which faculty members build their scholarly profile.[51] Upon successful evaluation, promotion to associate professor occurs, marking the mid-level rank and usually coinciding with the granting of tenure, which provides a more secure position.[52] Further advancement to full professor, the senior rank, requires another review after 5 to 7 years as associate, demonstrating sustained excellence and leadership in the field.[51] The tenure process is governed by a "tenure clock," a probationary period—often 6 years of full-time service—culminating in a comprehensive review of the candidate's dossier.[53] This dossier compiles evidence of performance across three core criteria: teaching (e.g., course evaluations and student outcomes), research or scholarship (e.g., publications and grants), and service (e.g., committee work and professional contributions).[54] Reviews proceed through multiple levels, including departmental committees, deans, and institutional leadership, with external letters from peers assessing the candidate's impact; annual progress evaluations occur earlier, such as in the third year, to guide development.[53] Positive outcomes lead to tenure and promotion, while negative decisions may result in non-renewal, emphasizing the high-stakes nature of this evaluation.[54] Tenure confers significant benefits, primarily job security, as tenured faculty can only be dismissed for cause, such as severe misconduct or financial exigency, rather than performance fluctuations or institutional priorities.[55] It also ensures academic freedom, allowing professors to explore controversial topics in research and teaching without fear of reprisal, thereby fostering institutional innovation and intellectual integrity.[55] Additionally, tenured faculty gain eligibility for paid sabbaticals, typically every 6 to 7 years, enabling focused periods of advanced study or creative work that enhance their contributions.[55] Since the 1990s, tenure-track positions have declined markedly in U.S. higher education, reflecting broader shifts toward contingent labor. In fall 1987, about 39% of faculty held full-time tenured appointments, but by fall 2021, this had fallen to 24%, with tenure-track roles comprising a shrinking share of the remaining full-time positions.[56] Overall, contingent appointments rose from 47% in 1987 to 68% in 2021, and remained at 68% as of fall 2023, driven by cost pressures and enrollment growth, reducing the availability of traditional tenure-track opportunities.[56][57]Non-Tenure and Adjunct Positions

Non-tenure-track positions in academia encompass a range of roles outside the traditional tenure system, including adjunct, visiting, and clinical professorships, which prioritize teaching and practical expertise over long-term job security and research obligations. These positions allow institutions to flexibly meet instructional needs while drawing on diverse professional backgrounds, but they often come with limited institutional support and precarious employment conditions. Unlike tenure-track roles, which integrate balanced expectations for teaching, research, and service leading to permanent appointment, non-tenure positions are typically contract-based and renewable at the institution's discretion.[58] Adjunct professors are commonly appointed on a part-time basis to teach specific courses, often without access to office space, research funding, or professional development resources. They bear heavy teaching loads, frequently juggling multiple institutions to achieve financial viability, and receive compensation solely for classroom hours, resulting in low overall pay that averages around $3,000–$8,000 per course depending on the field and location. This structure limits their involvement in curriculum development or academic governance, positioning them as supplemental instructors rather than integral faculty members.[59][60] Visiting and clinical professors fill temporary roles designed to infuse specialized knowledge into the academic environment, often for durations ranging from one semester to several years. Visiting professors are typically scholars on leave from other institutions or retirees sharing expertise through guest lectures and courses, facilitating short-term collaborations without long-term commitments. Clinical professors, prevalent in professional disciplines like law, medicine, and business, emphasize practical training and may hail from industry backgrounds, bringing real-world experience to supervise applied projects or clinics while focusing primarily on teaching over original research.[61][62] The proliferation of contingent faculty—encompassing adjuncts, full-time non-tenure-track, and other temporary roles—has reshaped higher education, with such positions accounting for 68% of all faculty appointments in U.S. colleges and universities as of fall 2023. This shift, driven by institutional cost-saving measures, has intensified precarity, manifesting in unstable contracts, absence of benefits like health insurance, and vulnerability to abrupt terminations, as evidenced during the COVID-19 pandemic when many lost work without recourse. These conditions erode academic freedom and institutional stability, prompting calls for improved equity and support.[63][64][65][57] Qualifications for non-tenure and adjunct positions generally require advanced degrees, such as a master's or doctorate in the relevant field, alongside demonstrated teaching ability or professional experience, but place far less weight on extensive publications compared to tenure-track paths. For instance, adjunct instructors may qualify with a master's and relevant credits in the discipline, while clinical or visiting roles often value industry leadership or prior academic service over scholarly output. This accessibility enables broader participation but underscores the roles' emphasis on immediate instructional contributions rather than sustained research careers.[66][67][68]Appointment and Promotion Processes

The appointment process for professorial positions typically begins with a job advertisement issued by the academic department or institution, outlining the required qualifications, responsibilities, and application materials.[69] These advertisements are often posted on professional association websites, academic job boards, and institutional career pages, with searches managed by a faculty search committee responsible for screening applications.[70] A doctoral degree, such as a PhD, is a standard minimum requirement for tenure-track positions, while postdoctoral experience is frequently expected, particularly in research-intensive fields like the sciences and engineering.[71] Following initial screening, shortlisted candidates undergo preliminary interviews, often at academic conferences, followed by on-campus visits that include presentations, meetings with faculty and students, and further discussions.[72] Reference checks are conducted as a critical step, involving direct contact with provided referees to verify the candidate's qualifications, research output, teaching abilities, and fit for the department; these checks may also include unsolicited references for top candidates.[70] The search committee then recommends finalists to the department chair or dean, who makes the final hiring decision after approval from higher administration, often incorporating institutional budget and strategic priorities.[73] Promotion within the professorial ranks, such as from associate to full professor, involves a rigorous evaluation process centered on sustained excellence in research, teaching, and service. Departments initiate reviews periodically or upon candidate request, compiling a dossier that includes the faculty member's curriculum vitae, publications, grant records, and self-assessment.[74] Peer reviews by internal colleagues assess the candidate's contributions against departmental standards, while external evaluation letters—typically a minimum of five from recognized experts in the field—provide independent validation of scholarly impact.[75] Quantitative metrics play a key role in these evaluations, with citation counts from databases like Google Scholar or Web of Science serving as indicators of research influence, alongside student evaluations of teaching effectiveness gathered through course feedback systems.[76] The dossier advances through multiple levels of review, including department vote, college committee, and provost or dean assessment, culminating in a tenure and promotion decision that emphasizes national or international recognition for full professorship.[77] Diversity initiatives in academic appointments have gained prominence since the early 2000s, with many institutions adopting affirmative action policies to address historical underrepresentation. For instance, the University of California system's Faculty Equity System tracks applicant demographics to promote inclusive hiring practices, requiring departments to report on efforts to recruit underrepresented groups.[78] Federal guidelines under Title VII of the [Civil Rights Act of 1964](/page/Civil Rights Act of 1964), reinforced by post-2000s equity mandates, encourage proactive recruitment strategies such as targeted outreach to minority-serving institutions and bias training for search committees.[79] Despite these efforts, challenges persist in hiring and promotion due to systemic biases, resulting in ongoing underrepresentation of women and racial minorities in the professoriate. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics indicate that in fall 2023, women comprised approximately 49% of full-time faculty at degree-granting institutions, with lower representation in STEM fields at about 28%.[80][81] Similarly, Black and Hispanic faculty held approximately 4.2% and 4.5% of full professorships, respectively, as of fall 2023, highlighting persistent racial disparities influenced by implicit bias in reference letters and evaluation criteria.[80] Studies show that underrepresented minority faculty face higher scrutiny in promotion reviews, with external letters often rating their work lower due to subjective assessments of "fit" and prestige.[82]Global Perspectives

Variations in Europe

In Germany, the term Hochschullehrer encompasses university teaching staff, including professors classified under the W-scale pay grades, which denote career stages and responsibilities. Junior professors hold W1 positions, typically tenure-track roles lasting up to six years with a focus on establishing research independence, while W2 and W3 positions represent mid- and full professorships, respectively, often with permanent civil servant status and leadership in departments.[83][84] These ranks emphasize a balance of research, teaching, and administration, with W3 professors leading chairs and securing external funding. In France, the rank of professeur des universités signifies a full professor role within public universities, where incumbents are appointed as civil servants by the state, ensuring job security and benefits tied to national regulations rather than institutional contracts.[85] This status underscores the bureaucratic, state-funded nature of French higher education, with recruitment via competitive national qualifications and a strong integration of research obligations alongside teaching. Nordic countries, such as Sweden, place significant emphasis on research in professorial roles, where professors allocate the majority of their time to independent research projects, grant acquisition, and scholarly output, supported by collective bargaining agreements negotiated by academic unions like SULF.[86][87] These agreements regulate working conditions, including protected research time and equitable distribution of teaching loads across institutions. In contrast, the United Kingdom's professorial rank represents the pinnacle of academic achievement, equivalent to a full professor elsewhere, but with a pronounced teaching component integrated into daily duties, where professors often lead large lecture courses, supervise dissertations, and contribute to curriculum development alongside research.[88] This reflects the UK's hybrid public-private university model, where teaching excellence is evaluated through student feedback and national assessments, differing from the more research-centric Nordic framework. The Bologna Process, initiated in 1999, has driven EU-wide harmonization of higher education systems, standardizing degree structures and qualifications to enhance professor mobility across borders.[89] By promoting the European Qualifications Framework and mutual recognition of credentials, it facilitates cross-country appointments and collaborations, reducing barriers for professors seeking positions in multiple member states. Gender parity in professorial roles has seen gradual progress, with women comprising about 30% of Grade A (higher academic) positions EU-wide as of 2022, supported by initiatives like Horizon Europe's gender equality plans that prioritize balanced representation in research leadership.[90]Practices in North America

In North America, the professorial role is predominantly shaped by the tenure-track system in the United States, where the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) establishes key standards for academic freedom and job security. The AAUP's 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, endorsed by over 280 organizations, defines tenure as a safeguard for full-time faculty to engage in teaching and research without external interference, with eligibility extending to all full-time members regardless of rank after a probationary period typically lasting up to seven years.[91] Termination during or after this period is permitted only for adequate cause, financial exigency, or program discontinuation, ensuring procedural due process.[92] By 2023, however, tenured and tenure-track positions comprised only about 32% of the faculty workforce, reflecting a shift toward contingency.[57] In Canada, professorial practices vary by province, with Ontario exemplifying the prominence of collective agreements that formalize working conditions through union negotiations. The Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) supports faculty associations in bargaining for equitable pay, academic freedom, and tenure protections, as seen in agreements like the 2024-2026 contract ratified by the Association of Professors of the University of Ottawa, which addresses workload, promotion, and equity provisions.[93] These agreements, often covering full-time and contract academic staff, emphasize collaborative governance and differ from the U.S. model by integrating stronger union oversight, such as in the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) Academic Employees Collective Agreement for colleges, which prioritizes full-time hiring over partial-load roles.[94] Institutional diversity significantly influences professorial duties, contrasting the teaching-centric roles at community colleges with the research-intensive expectations at R1 universities. At community colleges, faculty primarily focus on instruction, handling heavier loads of 15 credit hours per semester and developing curricula tailored to associate-degree programs, with tenure evaluations centered on pedagogical excellence rather than scholarly output.[95] In contrast, R1 institutions—classified by the Carnegie system as doctoral universities with very high research activity, requiring at least $50 million in annual R&D expenditures and 70 research doctorates—demand substantial publication records and grant acquisition from faculty, often allocating only 8-10 hours weekly to teaching while prioritizing research productivity for tenure and promotion.[96] This divide underscores how community colleges serve transfer and vocational students with applied teaching, whereas R1 environments emphasize advancing knowledge through high-impact research. Neoliberal reforms since the 1980s have profoundly altered these practices by reducing state funding and promoting market-oriented models, leading to greater reliance on adjunct faculty and influencing faculty workloads amid rising student debt. Public funding per student declined variably post-1980, prompting universities to raise tuition twelvefold by 2023 and diversify revenue, which shifted hiring toward contingent positions—now comprising over 60% of faculty—to control costs, thereby eroding tenure protections and increasing precarity.[97] This trend, exacerbated by student debt burdens exceeding $1.65 trillion as of 2025, has pressured institutions to expand class sizes and adjunct teaching to maintain affordability, indirectly reshaping tenured roles toward administrative oversight of larger, diverse student cohorts.[98] Efforts to address historical inequities through Indigenous and multicultural hiring initiatives are prominent, particularly in Canada via the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) program's equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) mandates. Universities must achieve targets by 2029—such as 50% women, 22% racialized minorities, 4.9% Indigenous peoples, and 7.5% persons with disabilities in CRC allocations—or face hiring restrictions prioritizing these groups, as enforced by the Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat.[99] In the U.S., similar initiatives include equity-minded cluster hiring, where departments recruit diverse faculty cohorts around thematic areas to foster inclusion, with over 20% of 2024-25 job postings requiring DEI statements to evaluate candidates' contributions to multicultural environments.[100] These approaches aim to diversify professoriates, which remain underrepresented for Indigenous and racialized groups, by embedding EDI in recruitment processes.[101]Systems in Asia and the Middle East

In China, the academic hierarchy for professors, known as "jiaoshou" for full professors, is structured into ranks including instructor, lecturer, associate professor, and professor, with promotions often influenced by alignment with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).[102] University charters increasingly emphasize "unswerving loyalty" to the CCP, requiring faculty to uphold Party leadership in teaching and research, as seen in revisions at institutions like Fudan University since 2018.[103] This political alignment can impact career progression, where expressions critical of the Party, such as discussions on its legitimacy, have led to dismissals of professors.[104] In India, the University Grants Commission (UGC) oversees professor promotions through regulations that mandate minimum qualifications, including a PhD, teaching experience, and research output measured by publications and API (Academic Performance Indicators) scores. Promotions from assistant to associate professor require at least eight years of service and a minimum of seven publications in refereed journals, while full professorship demands an additional six years and further scholarly contributions, ensuring standardization across public universities. These UGC guidelines, updated in 2018, prioritize merit-based advancement but face implementation challenges in resource-constrained institutions. In Gulf states like Saudi Arabia, professorial roles heavily rely on expatriate academics, who constitute a significant portion of faculty in universities such as King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), drawn by competitive packages to support knowledge transfer.[105] Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030 initiative promotes localization (Saudization) to reduce expatriate dependence, aiming to train and appoint more Saudi nationals as professors through scholarships and domestic PhD programs to increase the proportion of local faculty by 2030. This shift emphasizes building a sustainable academic workforce aligned with economic diversification goals. Japan's academic system traditionally grants professors lifetime employment upon achieving full rank, providing job security that fosters long-term research but can lead to complacency and resistance to reform.[106] This model, rooted in post-war labor practices, applies to national universities where tenured faculty hold positions until retirement age, typically 65, with limited turnover.[107] In contrast, South Korea's professorial landscape is highly competitive, with research funding often sourced from chaebol conglomerates like Samsung, which invest heavily in university-industry partnerships to drive innovation in fields such as electronics and biotechnology.[108] These collaborations support professor-led projects, but the pressure to secure grants from chaebols influences research priorities toward applied technologies over basic science. Across authoritarian regimes in Asia and the Middle East, professors face significant restrictions on academic freedom, including censorship of curricula and surveillance of scholarly activities to align with state ideologies.[109] In countries like China and Iran, faculty risk dismissal or arrest for research deemed politically sensitive, as documented in global monitoring reports tracking 391 attacks on higher education from July 2023 to June 2024.[110] Additionally, brain drain exacerbates these challenges in developing nations, with the Middle East experiencing some of the highest rates of academic emigration due to instability and limited opportunities, leading to faculty shortages in institutions like those in Yemen and Iraq. Efforts to reverse this, such as return incentives in Saudi Arabia under Vision 2030, aim to retain talent but contend with ongoing political pressures.[111]Compensation and Benefits

Salary Structures by Region

Professorial salaries vary significantly by region, influenced by economic conditions, institutional funding, and national policies. In North America, particularly the United States, full professors at public and private institutions earn an average of $160,954 annually for the 2024-25 academic year, based on nine- or ten-month contracts, with higher figures at private doctoral institutions reaching $203,603.[112] In Europe, salaries are generally lower but include strong social benefits; for instance, full (W3) professors in Germany earn between €5,543 and €7,778 gross per month (€66,516 to €93,336 annually), depending on the federal state and experience level.[113] In the United Kingdom, the average professor salary stands at £77,093 per year, reflecting national pay spines adjusted annually through collective bargaining.[114] In the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia, university professors average 236,366 SAR (approximately $63,000 USD) annually, often tax-free, attracting international talent to institutions like King Saud University.[115] In Asia, salaries vary widely; for example, full professors in China earn approximately ¥500,000 to ¥800,000 annually (about $70,000-$112,000 USD) at top universities, while in India, they average ₹20-30 lakhs (about $24,000-$36,000 USD), influenced by public funding and private sector competition.[116][117] Key factors shaping these structures include years of experience, academic field, and institution type. Entry-level full professors typically start 10-20% below averages, with salaries increasing through seniority steps or performance reviews; for example, in the US, a full professor with over 20 years may exceed $200,000 at research-intensive universities.[112] STEM fields command premiums over humanities due to external grant funding and market demand.[118] Public institutions often pay less than private ones; US public full professors average $151,270 compared to $203,603 at private independents.[112]| Region/Country | Average Full Professor Salary (Annual, Local Currency) | Key Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | $160,954 USD | 9-10 month contract; higher in private doctoral institutions | [112] |

| United Kingdom | £77,093 GBP | National pay spine; includes London weighting | [114] |

| Germany | €66,516–€93,336 EUR | W3 scale; state-dependent, gross | [113] |

| Saudi Arabia | 236,366 SAR | Tax-free; attracts expatriates with housing allowances | [115] |

| China | ¥500,000–¥800,000 CNY | Varies by institution; includes research incentives | [116] |

| India | ₹2,000,000–₹3,000,000 INR | UGC scales; higher in IITs/IISc | [117] |