Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sultanate of Zanzibar

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| History of Tanzania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Pre-colonial period |

| Colonial period |

| Modern history |

|

|

The Sultanate of Zanzibar (Swahili: Usultani wa Zanzibar, Arabic: سلطنة زنجبار, romanized: Sulṭanat Zanjībār), also known as the Zanzibar Sultanate,[1] was an East African Muslim state controlled by the Sultan of Zanzibar, in place between 1856 and 1964.[4] The Sultanate's territories varied over time, and after a period of decline, the state had sovereignty over only the Zanzibar Archipelago and a 16-kilometre-wide (10 mi) strip along the Kenyan coast, with the interior of Kenya constituting the British Kenya Colony and the coastal strip administered as a de facto part of that colony.

Under an agreement reached on 8 October 1963, the Sultan of Zanzibar relinquished sovereignty over his remaining territory on the mainland, and on 12 December 1963, Kenya officially obtained independence from the British. On 12 January 1964, revolutionaries, led by the African Afro-Shirazi Party, overthrew the mainly Arab government. Jamshid bin Abdullah, the last sultan, was deposed and lost sovereignty over Zanzibar, marking the end of the Sultanate, and resulted in the massacre of tens of thousands of Arabs. It was also involved in the shortest war in history, the Anglo-Zanzibar War, which lasted 38 minutes.

History

[edit]

Founding

[edit]According to the 16th-century explorer Leo Africanus, Zanzibar (Zanguebar) was the term used by Arabs and Persians to refer to the eastern African coast running from Kenya to Mozambique, dominated by five semi-independent Muslim kingdoms: Mombasa, Malindi, Kilwa, Mozambique, and Sofala. Africanus further noted that they all had standing agreements of loyalty with the major central African states, including the Kingdom of Mutapa.[5][6]

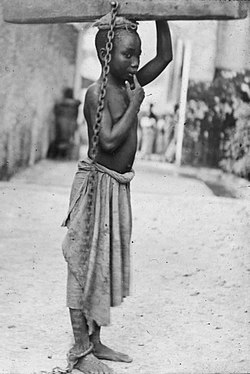

In 1698, Zanzibar became part of the overseas holdings of Oman after Saif bin Sultan, the Imam of Oman, defeated the Portuguese in Mombasa, in what is now Kenya. In 1832[7] or 1840,[8] Omani ruler Said bin Sultan moved his court from Muscat to Stone Town on the island of Unguja (that is, Zanzibar Island). He established a ruling Arab elite and encouraged the development of clove plantations, using the island's slave labour.[9] The East African slave trade flourished greatly from the second half of the nineteenth century, when Saif bin Sultan made Zanzibar his capital and expanded international commercial activities and plantation economy in cloves and coconuts.[10]

Zanzibar's commerce fell increasingly into the hands of traders from the Indian subcontinent, whom Said encouraged to settle on the island. After his death in 1856, two of his sons, Majid bin Said and Thuwaini bin Said, struggled over the succession, so Zanzibar and Oman were divided into two separate realms. Thuwaini became the Sultan of Muscat and Oman while Majid became the first Sultan of Zanzibar, but obliged to pay an annual tribute to the Omani court in Muscat.[11][12] During his 14-year reign as Sultan, Majid consolidated his power around the local slave trade. Pressed by the British, his successor, Barghash bin Said, helped abolish the slave trade in Zanzibar and largely developed the country's infrastructure.[13] The third Sultan, Khalifa bin Said, also furthered the country's progress toward abolishing slavery.[14]

Context for the Sultan's loss of control over his dominions

[edit]

Until 1884, the Sultans of Zanzibar controlled a substantial portion of the Swahili Coast, known as Zanj, and trading routes extending further into the continent, as far as Kindu on the Congo River. That year, however, the Society for German Colonization forced local chiefs on the mainland to agree to German protection, prompting Sultan Bargash bin Said to protest. Coinciding with the Berlin Conference and the Scramble for Africa, further German interest in the area was soon shown in 1885 by the arrival of the newly created German East Africa Company, which had a mission to colonize the area.

In 1886, the British and Germans secretly met and discussed their aims of expansion in the African Great Lakes, with spheres of influence already agreed upon the year before, with the British to take what would become the East Africa Protectorate (now Kenya) and the Germans to take present-day Tanzania. Both powers leased coastal territory from Zanzibar and established trading stations and outposts. Over the next few years, all of the mainland possessions of Zanzibar came to be administered by European imperial powers, beginning in 1888 when the Imperial British East Africa Company took over administration of Mombasa.[15]

The same year the German East Africa Company acquired formal direct rule over the coastal area previously submitted to German protection. This resulted in a native uprising, the Abushiri revolt, which was suppressed by the Kaiserliche Marine and heralded the end of Zanzibar's influence on the mainland.

The blockade of Zanzibar (1888–1889) was a joint international operation led by Germany, with the support of the British Empire, Portugal and Italy, against the Sultanate of Zanzibar, with the aim of ending the slave and arms trade off the eastern coast of Africa. This coalition aimed to coerce Sultan Khalifa bin Said of Zanzibar into rigorously enforcing existing treaties that prohibited the maritime slave trade and the illicit arms trade emanating from his East African dominions.[16]

Establishment of the Zanzibar Protectorate

[edit]With the signing of the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty between the United Kingdom and the German Empire in 1890, Zanzibar itself became a British protectorate.[17] In August 1896, following the death of Sultan Hamad bin Thuwaini, Britain and Zanzibar fought a 38-minute war, the shortest in recorded history. A struggle for succession took place as the Sultan's cousin Khalid bin Barghash seized power. The British instead wanted Hamoud bin Mohammed to become Sultan, believing that he would be much easier to work with. The British gave Khalid an hour to vacate the Sultan's palace in Stone Town. Khalid failed to do so, and instead assembled an army of 2,800 men to fight the British. The British launched an attack on the palace and other locations around the city after which Khalid retreated and later went into exile. Hamoud was then peacefully installed as Sultan.[18]

That "Zanzibar" for these purposes included the 16 km (10 mi) coastal strip of Kenya that would later become the Protectorate of Kenya was a matter recorded in the parliamentary debates at the time.[19]

-

Island of Unguja and the African mainland

-

Zanzibar's Sultanate c. 1875

-

The Harem and Tower Harbour of Zanzibar. 1890[20]

-

Independence stamp overprinted "Republic"

Establishment of the East Africa Protectorate

[edit]In 1886, the British government encouraged William Mackinnon, who already had an agreement with the Sultan and whose shipping company traded extensively in the African Great Lakes, to increase British influence in the region. He formed a British East Africa Association which led to the Imperial British East Africa Company being chartered in 1888 and given the original grant to administer the territory. It administered about 240 km (150 mi) of coastline stretching from the River Jubba via Mombasa to German East Africa which were leased from the Sultan. The British "sphere of influence", agreed at the Berlin Conference of 1885, extended up the coast and inland across the future Kenya and after 1890 included Uganda as well. Mombasa was the administrative centre at this time.[15]

However, the company began to fail, and on 1 July 1895 the British government proclaimed a protectorate, the East Africa Protectorate, the administration being transferred to the Foreign Office. In 1902, administration was again transferred to the Colonial Office and the Uganda territory was incorporated as part of the protectorate also. In 1897 Lord Delamere, the pioneer of white settlement, arrived in the Kenya highlands, which was then part of the Protectorate.[21]: 761 Lord Delamere was impressed by the agricultural possibilities of the area. In 1902 the boundaries of the Protectorate were extended to include what was previously the Eastern Province of Uganda.[21]: 761 [22] Also, in 1902, the East Africa Syndicate received a grant of 1,300 km2 (500 sq mi) to promote white settlement in the Highlands. Lord Delamere now commenced extensive farming operations, and in 1905, when a large number of immigrants arrived from Britain and South Africa, the Protectorate was transferred from the authority of the Foreign Office to that of the Colonial Office.[21]: 762 The capital was shifted from Mombasa to Nairobi in 1905. A regular Government and Legislature were constituted by Order in Council in 1906.[21]: 761 This constituted the administrator a governor and provided for legislative and executive councils. Lieutenant Colonel J. Hayes Sadler was the first governor and commander in chief. There were occasional troubles with local tribes but the country was opened up by the colonial government with little bloodshed.[21]: 761 After the First World War, more immigrants arrived from Britain and South Africa, and by 1919 the European population was estimated at 9,000 strong.[21]: 761

Loss of sovereignty over Kenya

[edit]On 23 July 1920, the inland areas of the East Africa Protectorate were annexed as British dominions by Order in Council.[23] That part of the former Protectorate was thereby constituted as the Colony of Kenya and from that time, the Sultan of Zanzibar ceased to be sovereign over that territory. The remaining 16 km (10 mi) wide coastal strip (with the exception of Witu) remained a Protectorate under an agreement with the Sultan of Zanzibar.[24] That coastal strip, remaining under the sovereignty of the Sultan of Zanzibar, was constituted as the Protectorate of Kenya in 1920.[15][25]

The Protectorate of Kenya was governed as part of the Colony of Kenya by virtue of an agreement between the United Kingdom and the Sultan dated 14 December 1895.[21]: 762 [26][27]

The Colony of Kenya and the Protectorate of Kenya each came to an end on 12 December 1963. The United Kingdom ceded sovereignty over the Colony of Kenya and, under an agreement dated 8 October 1963, the Sultan agreed that simultaneously with independence for Kenya, the Sultan would cease to have sovereignty over the Protectorate of Kenya.[21]: 762 [28] In this way, Kenya became an independent country under the Kenya Independence Act 1963. Exactly 12 months later on 12 December 1964, Kenya became a republic under the name "Republic of Kenya".[21]: 762

End of the Zanzibar Protectorate and deposition of the Sultan

[edit]On 10 December 1963, the Protectorate that had existed over Zanzibar since 1890 was terminated by the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom did not grant Zanzibar independence, as such, because the UK never had sovereignty over Zanzibar. Rather, by the Zanzibar Act 1963 of the United Kingdom,[29] the UK ended the Protectorate and made provision for full self-government in Zanzibar as an independent country within the Commonwealth. Upon the Protectorate being abolished, Zanzibar became a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth under the Sultan.[30] Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah was overthrown a month later during the Zanzibar Revolution.[31] Jamshid fled into exile, and the Sultanate was replaced by the People's Republic of Zanzibar. In April 1964, the existence of this socialist republic was ended with its union with Tanganyika to form the United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, which became known as Tanzania six months later.[8]

Demographics

[edit]By 1964, the country was a constitutional monarchy within the Commonwealth ruled by Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah.[32] Zanzibar had a population of around 230,000 natives, some of whom claimed Persian ancestry and were known locally as Shirazis.[2] It also contained significant minorities in the 50,000 Arabs and 20,000 South Asians who were prominent in business and trade.[2] The various ethnic groups were becoming mixed and the distinctions between them had blurred;[32] according to one historian, an important reason for the general support for Sultan Jamshid was his family's ethnic diversity.[32] However, the island's Arab inhabitants, as the major landowners, were generally wealthier than the natives;[33] the major political parties were organised largely along ethnic lines, with Arabs dominating the Zanzibar Nationalist Party (ZNP) and natives the Afro-Shirazi Party (ASP).[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Gascoigne, Bamber (2001). "History of Zanzibar". HistoryWorld. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Speller 2007, p. 4

- ^ "Coins of Zanzibar". Numista. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ Ndzovu, Hassan J. (2014). "Historical Evolution of Muslim Politics in Kenya from the 1840s to 1963". Muslims in Kenyan Politics: Political Involvement, Marginalization, and Minority Status. Northwestern University Press. pp. 17–50. ISBN 9780810130029. JSTOR j.ctt22727nc.7.

- ^ Africanus, Leo (1526). The History and Description of Africa. Hakluyt Society. pp. 51–54. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Ogot, Bethwell A. (1974). Zamani: A Survey of East African History. East African Publishing House. p. 104.

- ^ Ingrams 1967, p. 162

- ^ a b Appiah & Gates 1999, p. 2045

- ^ Ingrams 1967, p. 163

- ^ Coupland, Reginald (1967). The Exploitation of East Africa, 1856-1890: The Slave Trade and the Scramble. United States of America: Northwestern University Press.

- ^ "Background Note: Oman". U.S. Department of State - Diplomacy in Action.

- ^ Ingrams 1967, pp. 163–164

- ^ Michler 2007, p. 37

- ^ Ingrams 1967, p. 172

- ^ a b c "British East Africa". www.heliograph.com.

- ^ "Anglo-German Agreement | Europe [1886] | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 22 July 2025.

- ^ Ingrams 1967, pp. 172–173

- ^ Michler 2007, p. 31

- ^ "BRITISH EAST AFRICA. (Hansard, 13 June 1895)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 13 June 1895.

- ^ "The Harem and Tower Harbour of Zanzibar". Chronicles of the London Missionary Society: 234. 1890. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Roberts-Wray, Sir Kenneth (1966). Commonwealth and Colonial Law. F.A. Praeger.

- ^ East Africa Order in Council, 1902, S.R.O. 1902 No. 661, S.R.O. ^ S.I. Rev. 246

- ^ Kenya (Annexation) Order in Council, 1920, S.R.O. 1902 No. 661, S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. 246.

- ^ Agreement of 14 June 1890: State pp. vol. 82. p. 653

- ^ Kenya Protectorate Order in Council, 1920 S.R.O. 1920 No. 2343, S.R.O. & S.I. Rev. VIII, 258, State Pp., Vol. 87 p. 968

- ^ Kenya Protectorate Order in Council, 1920, S.R.O. 1920 No. 2343 & S.I. Rev. VIII, 258, State Pp., Vol. 87, p.968.

- ^ "Kenya Gazette". 7 September 1921 – via Google Books.

- ^ HC Deb 22 November 1963 vol 684 cc1329-400 wherein the UK Under-Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations and for the Colonies stated" "An agreement was then signed on 8 October 1963, providing that on the date when Kenya became independent the territories composing the Kenya Coastal Strip would become part of Kenya proper."

- ^ Zanzibar Act 1963: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1963/55/contents/

- ^ United States Department of State 1975, p. 986

- ^ Ayany 1970, p. 122

- ^ a b c d Shillington 2005, p. 1716

- ^ Parsons 2003, p. 106

Bibliography

[edit]- Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis Jr., eds. (1999), Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00071-1, OCLC 41649745

- Ingrams, William H. (1967), Zanzibar: Its History and Its People, Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 0-7146-1102-6, OCLC 186237036

- Ayany, Samuel G. (1970), A History of Zanzibar: A Study in Constitutional Development, 1934–1964, Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau, OCLC 201465

- Michler, Ian (2007), Zanzibar: The Insider's Guide (2nd ed.), Cape Town: Struik Publishers, ISBN 978-1-77007-014-1, OCLC 165410708

- Parsons, Timothy (2003), The 1964 Army Mutinies and the Making of Modern East Africa, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-325-07068-7.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005), Encyclopedia of African History, CRC Press, ISBN 1-57958-245-1.

- Speller, Ian (2007), "An African Cuba? Britain and the Zanzibar Revolution, 1964.", Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 35 (2): 1–35, doi:10.1080/03086530701337666, S2CID 159656717.

- United States Department of State (1975), Countries of the World and Their Leaders (2nd ed.), Detroit: Gale Research Company, OCLC 1492755

External links

[edit]- Official website of the Zanzibar Royal Family

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Sultanate of Zanzibar

View on GrokipediaThe Sultanate of Zanzibar was a monarchy in East Africa ruled by sultans of Omani Arab origin from the Al Busaidi dynasty, spanning 1856 to 1964 with its capital in Stone Town on Unguja Island in the Zanzibar Archipelago.[1] It exerted commercial influence over coastal East Africa and interior trade routes, emerging as a key node in Indian Ocean commerce after Omani Sultan Said bin Sultan transferred his court's base from Muscat to Zanzibar around 1840 and developed clove plantations there using enslaved labor.[1][2] The sultanate was formally created on 19 October 1856 following Said's death, when his sons divided the Omani domains, with Majid bin Said assuming rule over Zanzibar.[3] The economy centered on exporting ivory, slaves, and cloves, the latter becoming dominant after their introduction around 1812 and expansion via large-scale plantations reliant on imported slaves from East Africa's interior, which fueled both local agriculture and the transoceanic slave trade to the Middle East until British pressure led to its abolition in 1873.[2][1] Trade networks connected Omani, Indian, and European merchants, with treaties facilitating growth in exports like copal and sesame alongside the primary commodities.[2] British influence intensified, culminating in a protectorate status via the 1890 Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty and the brief Anglo-Zanzibar War of 1896, the shortest recorded conflict at under an hour, which ousted a rebellious sultan.[1] A series of sultans, including Barghash bin Said who modernized infrastructure, governed under increasing European oversight until independence from Britain on 10 December 1963.[3][1] The sultanate ended abruptly with the Zanzibar Revolution on 12 January 1964, when African-led insurgents under John Okello overthrew the last sultan, Jamshid bin Abdullah, amid ethnic tensions between the Arab elite and African majority, resulting in approximately 17,000 deaths primarily among Arabs and South Asians, widespread property seizures, and the deposing of the monarchy.[4][1] The ensuing People's Republic under Abeid Karume implemented land reforms and racially targeted policies before uniting with Tanganyika on 26 April 1964 to form Tanzania, marking the sultanate's dissolution.[4]

Origins and Establishment

Omani Influence and Conquest of Zanzibar

The Portuguese seized Zanzibar in the early 16th century as part of their maritime empire, exploiting its strategic position for Indian Ocean trade, but their control eroded amid logistical challenges and rebellions by local Swahili elites allied with inland powers. In 1696, Omani Imam Saif bin Sultan al-Ya'rubi launched a prolonged siege against the Portuguese Fort Jesus in Mombasa, capturing it in December 1698 after a two-year campaign that leveraged Omani naval blockades and reinforcements from Arab allies. This victory precipitated the Portuguese withdrawal from Zanzibar by early 1699, establishing nominal Omani overlordship over the island and adjacent Swahili ports through garrisons and tribute extraction.[5][6][7] Throughout the 18th century, Omani authority in East Africa remained precarious, undermined by dynastic instability in Oman—including the decline of the Ya'ariba imamate and Persian occupations of Muscat—yet persisted via fortified coastal enclaves and pragmatic alliances with autonomous Swahili city-states such as Kilwa and Pate. These city-states, governed by sultans of mixed Arab-African descent, granted Omani governors nominal sovereignty in exchange for military protection against inland threats and access to transoceanic commerce networks, fostering a hybrid suzerain-vassal system rather than direct administration. Trade incentives, particularly the flow of ivory from the African interior and spices via monsoon winds, incentivized Omanis to invest in naval patrols that deterred European interlopers and rival Arab traders from the Persian Gulf.[8] Said bin Sultan, who seized the Omani throne in 1806 amid fratricidal conflicts, methodically consolidated East African holdings by deploying flotillas of dhows and war galleys to enforce tribute and quell uprisings in ports like Mombasa. Recognizing Zanzibar's centrality as a nexus for exporting East African commodities to India and Arabia, Said first arrived there in 1828 to assess its potential, then relocated his court permanently in 1832, prioritizing economic oversight over ceremonial ties to Muscat. This shift, propelled by the profitability of monopolizing slave and ivory caravans from the mainland, elevated Zanzibar's administrative primacy within the Omani domain, binding the island's fortunes to Omani maritime prowess without fully supplanting local Swahili customs.[9][10][11]Capital Transfer and Formal Founding in 1856

In 1840, Sultan Said bin Sultan relocated the capital of his Omani domains from Muscat to Stone Town on Zanzibar Island, drawn by the archipelago's deep natural harbor—which surpassed Muscat's in accommodating large dhow fleets—and its geographic proximity to the East African mainland's resource-rich interior, enabling efficient oversight of expanding trade in ivory, cloves, and slaves.[9][12] This shift reflected the empire's economic reorientation toward African coastal entrepôts, where Zanzibar served as a nexus for Indian Ocean commerce, with annual clove exports alone reaching substantial volumes by the mid-1840s due to plantations established under Said's direct administration.[12] The move involved transplanting Said's court, including relatives and officials, to ornate coral-stone palaces like Bet il Sahel, solidifying Zanzibar's role as the administrative and commercial hub over Oman's fragmented Arabian holdings.[12] Said bin Sultan's death on 19 October 1856 aboard his ship Victoria en route from Muscat to Zanzibar triggered a succession crisis, as his will—allegedly dividing the empire between his sons—pitted Majid bin Said, who controlled Zanzibar, against Thuwaini bin Said, who held Muscat and sought dominion over all territories.[11][13] Thuwaini dispatched forces toward Zanzibar, but British mediation, led by Acting Consul Rigby and culminating in Lord Canning's arbitration as Governor-General of India, upheld the partition to avert broader instability, recognizing Majid's de facto authority in the east.[14][15] This intervention aligned with British interests in stabilizing trade routes while limiting Omani consolidation, as evidenced by prior treaties curbing slave exports.[15] On 19 October 1856, Majid bin Said was formally proclaimed Sultan of Zanzibar, marking the establishment of an independent sultanate encompassing Unguja and Pemba islands plus mainland possessions such as the coastal ports from Mogadishu to Kilwa, with an estimated annual revenue of 2 million Maria Theresa dollars derived primarily from customs duties.[1][7] The partition severed Zanzibar's nominal ties to Muscat, granting Majid sovereignty under a perpetual treaty obligation to Britain for protection, while Thuwaini retained Oman; this delineation persisted until European encroachments in the 1880s, underscoring how geographic and economic imperatives, rather than dynastic unity, defined the sultanate's viability.[1][14]Government and Rulers

Succession of Sultans from Majid to Jamshid

Majid bin Said Al-Busaid, the first Sultan of Zanzibar following the 1856 partition of his father Said bin Sultan's domains, reigned from 19 October 1856 until his death on 7 October 1870.[3][1] He consolidated control over East African trade routes, prioritizing the slave trade as a economic pillar despite emerging European abolitionist pressures.[16] Barghash bin Said Al-Busaid succeeded his brother Majid on 7 October 1870 and ruled until 26 March 1888.[3] His reign involved resisting British demands to curb the slave trade, culminating in the 1873 treaty that restricted but did not eliminate it, thereby maintaining fiscal stability amid diplomatic tensions.[16] Barghash's efforts to modernize infrastructure, such as building the first piped water system, reflected adaptive governance under growing foreign influence.[17] Khalifah bin Said Al-Busaid briefly held the throne from 26 March 1888 to 13 February 1890, following familial disputes over Barghash's succession.[3] His short rule ended with his death, amid patterns of intra-dynastic rivalry that characterized Al Busaid transitions. Ali bin Said Al-Busaid then reigned from 13 February 1890 to 29 March 1893, continuing under British scrutiny as Zanzibar's autonomy waned.[17] Hamad bin Thuwaini Al-Busaid governed from 29 March 1893 until his death on 25 August 1896, a period marked by alignment with British interests to secure recognition.[18] His passing triggered a fratricidal crisis when Khalid bin Barghash, his nephew, seized the palace and proclaimed himself sultan on 26 August 1896, defying British preference for Hamud bin Muhammad.[18] The ensuing Anglo-Zanzibar War on 27 August 1896, lasting approximately 38 minutes, saw British naval bombardment destroy Khalid's forces, installing Hamud and establishing de facto protectorate veto power over successions.[18][19] Hamud bin Muhammad Al-Busaid ruled from 27 August 1896 to 18 July 1902, signing the 1897 Frere Town agreement to phase out coastal slave markets under British mandate, which stabilized relations but eroded sovereign trade autonomy.[17] Ali bin Hamud Al-Busaid succeeded from 18 July 1902 to 21 July 1911, navigating protectorate constraints formalized in 1890, with British residents increasingly dictating administrative approvals.[17] Khalifah bin Harub Al-Busaid's extended reign from 21 July 1911 to 9 October 1960 exemplified stability under colonial oversight, as he deferred to British vetoes on policy and succession to avoid disputes that had previously destabilized the dynasty.[17][13] His rule spanned both world wars and post-war decolonization pressures, maintaining nominal monarchy amid economic dependencies. Abdullah bin Khalifah Al-Busaid reigned from 9 October 1960 until his abdication on 1 July 1963 due to health issues, paving the way for independence negotiations.[13] Jamshid bin Abdullah Al-Busaid, the last sultan, acceded on 1 July 1963 and ruled until the 12 January 1964 revolution deposed him, ending the sultanate after Zanzibar's brief independence on 10 December 1963.[13][1]| Sultan | Reign Period |

|---|---|

| Majid bin Said Al-Busaid | 1856–1870 |

| Barghash bin Said Al-Busaid | 1870–1888 |

| Khalifah bin Said Al-Busaid | 1888–1890 |

| Ali bin Said Al-Busaid | 1890–1893 |

| Hamad bin Thuwaini Al-Busaid | 1893–1896 |

| Hamud bin Muhammad Al-Busaid | 1896–1902 |

| Ali bin Hamud Al-Busaid | 1902–1911 |

| Khalifah bin Harub Al-Busaid | 1911–1960 |

| Abdullah bin Khalifah Al-Busaid | 1960–1963 |

| Jamshid bin Abdullah Al-Busaid | 1963–1964 |

.svg/250px-Flag_of_the_Sultanate_of_Zanzibar_(1963).svg.png)

.svg/2000px-Flag_of_the_Sultanate_of_Zanzibar_(1963).svg.png)

![Sultanate of Zanzibar in pink[clarification needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1c/Omani_Empire_2.png/250px-Omani_Empire_2.png)

![The Harem and Tower Harbour of Zanzibar. 1890[20]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/The_Harem_and_Tower_Harbour_of_Zanzibar_%28p.234%2C_1890%29_-_Copy.jpg/120px-The_Harem_and_Tower_Harbour_of_Zanzibar_%28p.234%2C_1890%29_-_Copy.jpg)