Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called a zoological park, animal park, or menagerie) is a facility where animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for conservation purposes.[1]

The term zoological garden refers to zoology, the study of animals. The term is derived from the Ancient Greek ζῷον, zōion, 'animal', and the suffix -λογία, -logia, 'study of'. The abbreviation zoo was first used of the London Zoological Gardens, which was opened for scientific study in 1828, and to the public in 1847.[2] The first modern zoo was the Tierpark Hagenbeck by Carl Hagenbeck in Germany. In the United States alone, zoos are visited by over 181 million people annually.[3]

Etymology

[edit]

The London Zoo, which was opened in 1828, was initially known as the "Gardens and Menagerie of the Zoological Society of London", and it described itself as a menagerie or "zoological forest".[4] The abbreviation "zoo" first appeared in print in the United Kingdom around 1847, when it was used for the Clifton Zoo, but it was not until some 20 years later that the shortened form became popular in the rhyming song "Walking in the Zoo" by music-hall artist Alfred Vance.[4] The term "zoological park" was used for more expansive facilities in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Washington, D.C., and the Bronx in New York, which opened in 1846, 1891 and 1899 respectively.[5]

Relatively new terms for zoos, in the late 20th century are "conservation park" or "bio park". Adopting a new name is a strategy used by some zoo professionals to distance their institutions from the stereotypical and nowadays criticized zoo concept of the 19th century.[6] The term "bio park" was first coined and developed by the National Zoo in Washington D.C. in the late 1980s.[7] In 1993, the New York Zoological Society changed its name to the Wildlife Conservation Society and re branded the zoos under its jurisdiction as "wildlife conservation parks".[8]

History

[edit]Royal menageries

[edit]

The predecessor of the zoological garden is the menagerie, which has a long history from the ancient world to modern times. The oldest known zoological collection was revealed during excavations at Hierakonpolis, Egypt in 2009, of a c. 3500 BCE menagerie. The exotic animals included hippos, hartebeest, elephants, baboons and wildcats.[9] King Ashur-bel-kala of the Middle Assyrian Empire created zoological and botanical gardens in the 11th century BC. In the 2nd century BC, the Chinese Empress Tanki had a "house of deer" built, and King Wen of Zhou kept a 1,500-acre (610 ha) zoo called Ling-Yu, or the Garden of Intelligence. Other well-known collectors of animals included King Solomon of the Kingdom of Israel and Judah, Queen Semiramis and King Ashurbanipal of Assyria, and King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylonia.[10] By the 4th century BC, zoos existed in most of the Greek city states; Alexander the Great is known to have sent animals that he found on his military expeditions back to Greece. The Roman emperors kept private collections of animals for study or for use in the arena,[10] the latter faring notoriously poorly. The 19th-century historian W. E. H. Lecky wrote of the Roman games, first held in 366 BCE:

At one time, a bear and a bull, chained together, rolled in fierce combat across the sand ... Four hundred bears were killed in a single day under Caligula ... Under Nero, four hundred tigers fought with bulls and elephants. In a single day, at the dedication of the Colosseum by Titus, five thousand animals perished. Under Trajan ... lions, tigers, elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotami, giraffes, bulls, stags, even crocodiles and serpents were employed to give novelty to the spectacle.[11]

Charlemagne had an elephant named Abul-Abbas that was given to him by the Abbasid caliph.

King Henry I of England kept a collection of animals at his palace in Woodstock which reportedly included lions, leopards, and camels.[12] The most prominent collection in medieval England was in the Tower of London, created as early as 1204 by King John I. Henry III received a wedding gift in 1235 of three leopards from Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, and in 1264, the animals were moved to the Bulwark, renamed the Lion Tower, near the main western entrance of the Tower. It was opened to the public during the reign of Elizabeth I in the 16th century.[13] During the 18th century, the price of admission was three half-pence, or the supply of a cat or dog for feeding to the lions.[12] The animals were moved to the London Zoo when it opened.

Aztec emperor Moctezuma II had in his capital city of Tenochtitlan a "house of animals" with a large collection of birds, mammals and reptiles in a garden tended by more than 600 employees. The garden was described by several Spanish conquerors, including Hernán Cortés in 1520. After the Aztec revolt against the Spanish rule, and during the subsequent battle for the city, Cortés reluctantly ordered the zoo to be destroyed.[14]

Enlightenment era

[edit]

The oldest zoo in the world still in existence is the Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna, Austria. It was constructed by Adrian van Stekhoven in 1752 at the order of Emperor Francis I, to serve as an imperial menagerie as part of Schönbrunn Palace. The menagerie was initially reserved for the viewing pleasure of the imperial family and the court, but was made accessible to the public in 1765.[15] In 1775, a zoo was founded in Madrid, and in 1795, the zoo inside the Jardin des Plantes in Paris was founded by Jacques-Henri Bernardin, with animals from the royal menagerie at Versailles, primarily for scientific research and education. The planning about a space for the conservation and observation of animals was expressed in connection with the political construction of republican citizenship.[16]

The Kazan Zoo, the first zoo in Russia was founded in 1806 by the Professor of Kazan Federal University Karl Fuchs.

The modern zoo

[edit]Until the early 19th century, the function of the zoo was often to symbolize royal power, like King Louis XIV's menagerie at Versailles. Major cities in Europe set up zoos in the 19th century, usually using London and Paris as models. The transition was made from princely menageries designed to entertain high society with strange novelties into public zoological gardens. The new goal was to educate the entire population with information along modern scientific lines. Zoos were supported by local commercial or scientific societies.

British Empire

[edit]

The modern zoo that emerged in the 19th century in the United Kingdom[17] was focused on providing scientific study and later educational exhibits to the public for entertainment and inspiration.[18]

A growing fascination for natural history and zoology, coupled with the tremendous expansion in the urbanization of London, led to a heightened demand for a greater variety of public forms of entertainment to be made available. The need for public entertainment, as well as the requirements of scholarly research, came together in the founding of the first modern zoos. Whipsnade Zoo in Bedfordshire, England, opened in 1931. It allowed visitors to drive through the enclosures and come into close proximity with the animals.

The Zoological Society of London was founded in 1826 by Stamford Raffles and established the London Zoo in Regent's Park two years later in 1828.[19] At its founding, it was the world's first scientific zoo.[10][20] Originally intended to be used as a collection for scientific study, it was opened to the public in 1847.[20] The Zoo is located in Regent's Park—then undergoing development at the hands of the architect John Nash. What set the London zoo apart from its predecessors was its focus on society at large. The zoo was established in the middle of a city for the public, and its layout was designed to cater for the large London population. The London zoo was widely copied as the archetype of the public city zoo.[21] In 1853, the Zoo opened the world's first public aquarium. It closed in 2019 and some fish moved to Whipsnade Zoo.

Dublin Zoo was opened in 1831 by members of the medical profession interested in studying animals while they were alive and more particularly getting hold of them when they were dead.[22]

Downs' Zoological Gardens created by Andrew Downs and opened to the Nova Scotia public in 1847. It was originally intended to be used as a collection for scientific study. By the early 1860s, the zoo grounds covered 40 hectares with many fine flowers and ornamental trees, picnic areas, statues, walking paths, The Glass House (which contained a greenhouse with an aviary, aquarium, and museum of stuffed animals and birds), a pond, a bridge over a waterfall, an artificial lake with a fountain, a wood-ornamented greenhouse, a forest area, and enclosures and buildings.[23][24][25]

The first zoological garden in Australia was Melbourne Zoo in 1860.

Germany

[edit]

In German states leading roles came Berlin (1841), Frankfurt (1856), and Hamburg (1863). In 1907, the entrepreneur Carl Hagenbeck founded the Tierpark Hagenbeck in Eimsbüttel, now a quarter of Hamburg. His zoo was a radical departure from the layout of the zoo that had been established in 1828. It was the first zoo to use open enclosures surrounded by moats, rather than barred cages, to better approximate animals' natural environments.[26] He also set up mixed-species exhibits and based the layout on the different organizing principle of geography, as opposed to taxonomy.[27]

Poland

[edit]

The Wrocław Zoo (Polish: Ogród Zoologiczny we Wrocławiu) is the oldest zoo in Poland, opened in 1865 when the city was part of Prussia, and was home to about 10,500 animals representing about 1,132 species (in terms of the number of animal species, it is the third largest in the world[28]). In 2014 the Wrocław Zoo opened the Africarium, the only themed oceanarium devoted solely to exhibiting the fauna of Africa, comprehensively presenting selected ecosystems from the continent of Africa. Housing over 10 thousand animals, the facility's breadth extends from housing insects such cockroaches to large mammals like elephants on an area of over 33 hectares.[29]

United States

[edit]In the United States, the Philadelphia Zoo, opened on July 1, 1874, earning its motto "America's First Zoo." The Lincoln Park Zoological Gardens in Chicago and the Cincinnati Zoo opened in 1875. In the 1930s, federal relief programs provided financial aid to most local zoos. The Works Progress Administration and similar New Deal government agencies helped greatly in the construction, renovation, and expansion of zoos when the Great Depression severely reduced local budgets. It was "a new deal for animals."[30]

The Atlanta Zoo, founded in 1886, suffered neglect. By 1984 it was ranked among the ten worst zoos in the United States. Systematic reform by 2000 put it on the list of the ten best.[31]

By 2020, the United States featured 230 accredited zoos and aquariums across 45 states, accommodating 800,000 animals, and 6,000 species out of which about 1,000 are endangered. The zoos provide 208,000 jobs, and with an annual budget of $230 million for wildlife conservation. They attract over 200 million visits a year and have special programs for schools. They are organized by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.[32][33]

Japan

[edit]Japan's first modern zoo, Tokyo's Ueno Zoo, opened in 1882 based on European models. In World War II it was used to teach the Japanese people about the lands recently conquered by the Army. In 1943, fearing American bombing attacks, the government ordered the zoo to euthanize dangerous animals that might escape.[34][35]

Environmentalism

[edit]

When ecology emerged as a matter of public interest in the 1970s, a few zoos began to consider making conservation their central role, with Gerald Durrell of the Jersey Zoo, George Rabb of Brookfield Zoo Chicago, and William Conway of the Bronx Zoo (Wildlife Conservation Society) leading the discussion. From then on, zoo professionals became increasingly aware of the need to engage themselves in conservation programs, and the American Zoo Association soon said that conservation was its highest priority.[36] To stress conservation issues, many large zoos stopped the practice of having animals perform tricks for visitors. The Detroit Zoo, for example, stopped its elephant show in 1969, and its chimpanzee show in 1983, acknowledging that the trainers had probably abused the animals to get them to perform.[37]

Mass destruction of wildlife habitat has yet to cease all over the world and many species such as elephants, big cats, penguins, tropical birds, primates, rhinos, exotic reptiles, and many others are in danger of dying out. Many of today's zoos hope to stop or slow the decline of many endangered species and see their primary purpose as breeding endangered species in captivity and reintroducing them into the wild. Modern zoos also aim to help teach visitors the importance of animal conservation, often through letting visitors witness the animals firsthand.[38] Some critics, and the majority of animal rights activists, say that zoos, no matter their intentions, or how noble these intentions, are immoral and serve as nothing but to fulfill human leisure at the expense of the animals (an opinion that has spread over the years). However, zoo advocates argue that their efforts make a difference in wildlife conservation and education.[38]

Human exhibits

[edit]

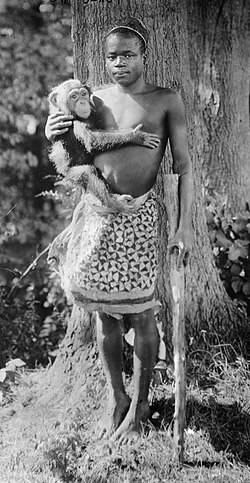

Humans were occasionally displayed in cages at zoos along with non-human animals, to illustrate the differences between people of European and non-European origin. In September 1906, William Hornaday, director of the Bronx Zoo in New York City—with the agreement of Madison Grant, head of the New York Zoological Society—had Ota Benga, a Congolese pygmy, displayed in a cage with the chimpanzees, then with an orangutan named Dohong, and a parrot. The exhibit was intended as an example of the "missing link" between the orangutan and white man. It triggered protests from the city's clergymen, but the public reportedly flocked to see Benga.[39][40]

Humans were also displayed at various events, especially colonial expositions such as the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition, with the practice continuing in Belgium at least to as late as 1958 in a "Congolese village" display at Expo 58 in Brussels. These displays, while sometimes called "human zoos", usually did not take place in zoos or use cages.[41]

Type

[edit]

Zoo animals live in enclosures that often attempt to replicate their natural habitats or behavioural patterns, for the benefit of both the animals and visitors. Nocturnal animals are often housed in buildings with a reversed light-dark cycle, i.e. only dim white or red lights are on during the day so the animals are active during visitor hours, and brighter lights on at night when the animals sleep. Special climate conditions may be created for animals living in extreme environments, such as penguins. Special enclosures for birds, mammals, insects, reptiles, fish, and other aquatic life forms have also been developed. Some zoos have walk-through exhibits where visitors enter enclosures of non-aggressive species, such as lemurs, marmosets, birds, lizards, and turtles. Visitors are asked to keep to paths and avoid showing or eating foods that the animals might snatch.

Safari park

[edit]

Some zoos keep animals in larger, outdoor enclosures, confining them with moats and fences, rather than in cages. Safari parks, also known as zoo parks and lion farms, allow visitors to drive through them and come in close proximity to the animals.[10] Sometimes, visitors are able to feed animals through the car windows.

The first safari park was Whipsnade Park in Bedfordshire, England, opened by the Zoological Society of London in 1931 which since 2014 covers 600 acres (240 hectares). Since the early 1970s, an 1,800 acres (730 hectares) park in the San Pasqual Valley near San Diego has featured the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, run by the Zoological Society of San Diego. One of two state-supported zoo parks in North Carolina is the 2,000 acres (810 hectares) North Carolina Zoo in Asheboro.[42] The 500 acres (200 hectares) Werribee Open Range Zoo in Melbourne, Australia, displays animals living in an artificial savannah.

Aquaria

[edit]

The first public aquarium was opened at the London Zoo in 1853. This was followed by the opening of public aquaria in continental Europe (e.g. Paris in 1859, Hamburg in 1864, Berlin in 1869, and Brighton in 1872) and the United States (e.g. Boston in 1859, Washington in 1873, San Francisco Woodward's Gardens in 1873, and the New York Aquarium at The Battery in 1896).

Roadside zoos

[edit]Roadside zoos are found throughout North America, particularly in remote locations. They are often small, for-profit zoos, often intended to attract visitors to some other facility, such as a gas station. The animals may be trained to perform tricks, and visitors are able to get closer to them than in larger zoos.[43] Since they are sometimes less regulated, roadside zoos are often subject to accusations of neglect[44] and cruelty.[45]

In June 2014 the Animal Legal Defense Fund filed a lawsuit against the Iowa-based roadside Cricket Hollow Zoo for violating the Endangered Species Act by failing to provide proper care for its animals.[46] Since filing the lawsuit, ALDF has obtained records from investigations conducted by the USDA's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services; these records show that the zoo is also violating the Animal Welfare Act.[47]

Petting zoos

[edit]

A petting zoo, also called petting farm or children's zoo, features a combination of domestic animals and wild species that are docile enough to touch and feed. To ensure the animals' health, the food is supplied by the zoo, either from vending machines or a kiosk nearby.

Animal theme parks

[edit]An animal theme park is a combination of an amusement park and a zoo, mainly for entertaining and commercial purposes. Marine mammal parks such as SeaWorld, Sea Life and Marineland are more elaborate dolphinariums keeping whales, and containing additional entertainment attractions. Another kind of animal theme park contains more entertainment and amusement elements than the classical zoo, such as stage shows, roller coasters, and mythical creatures. Some examples are Busch Gardens Tampa Bay in Tampa, Florida, both Disney's Animal Kingdom and Gatorland in Orlando, Florida, Flamingo Land Resort in North Yorkshire, England, and Six Flags Discovery Kingdom in Vallejo, California.

Zoo population management

[edit]Sources of animals

[edit]By 2000 most animals being displayed in zoos were the offspring of other zoo animals.[citation needed] This trend, however was and still is somewhat species-specific. When animals are transferred between zoos, they usually spend time in quarantine, and are given time to acclimatize to their new enclosures which are often designed to mimic their natural environment. For example, some species of penguins may require refrigerated enclosures. Guidelines on necessary care for such animals is published in the Zoological Society of London.[48] Animal exchanges between facilities are usually made voluntarily, based on a model of cooperation for conservation. Loaned animals usually remain the property of the original park, and any offspring yielded by loaned animals are usually divided between the lending and holding institutions. For decades the capture of wild animals or purchasing of animals has been broadly considered unethical and has not been practiced by reputable zoos.

Space constraints and surplus animals

[edit]

Especially in large animals, a limited number of spaces are available in zoos. As a consequence, various management tools are used to preserve the space for the genetically most important individuals and to reduce the risk of inbreeding. Management of animal populations is typically through international organizations such as AZA and EAZA.[49] Zoos have several different ways of managing the animal populations, such as moves between zoos, contraception, sale of excess animals and euthanization (culling).[50]

Contraception can be an effective way to limit a population's breeding. However it may also have health repercussions and can be difficult or even impossible to reverse in some animals.[51] Additionally, some species may lose their reproductive capability entirely if prevented from breeding for a period (whether through contraceptives or isolation), but further study is needed on the subject.[49] Sale of surplus animals from zoos was once common and in some cases animals have ended up in substandard facilities. In recent decades the practice of selling animals from certified zoos has declined.[50] A large number of animals are culled each year in zoos, but this is controversial.[52] A highly publicized culling as part of population management was that of a healthy giraffe at Copenhagen Zoo in 2014. The zoo argued that his genes already were well-represented in captivity, making the giraffe unsuitable for future breeding. There were offers to adopt him and an online petition to save him had many thousand signatories, but the culling proceeded.[53] Although zoos in some countries have been open about culling, the controversy of the subject and pressure from the public has resulted in others being closed.[50] This stands in contrast to most zoos publicly announcing animal births.[50] Furthermore, while many zoos are willing to cull smaller and/or low-profile animals, fewer are willing to do it with larger high-profile species.[50][52]

Breeding and cloning

[edit]Many animals breed readily in captivity. Zoos frequently are forced to intentionally limit captive breeding because of a lack of natural wild habitat in which to reintroduce animals.[54] This highlights the importance of in situ conservation, or preservation of natural spaces, in addition to the utility of zoo captive breeding and reintroduction programs. In situ conservation and reintroduction programs are key elements to obtaining certification by reputable organisations such as the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA).[55] Efforts to clone endangered species in the United States, Europe, and Asia are frequently embedded in zoos and zoological parks.[56]

Justification

[edit]Conservation and research

[edit]

The position of most modern zoos in Australasia, Asia, Europe, and North America, particularly those with scientific societies, is that they display wild animals primarily for the conservation of endangered species, as well as for research purposes and education, and secondarily for the entertainment of visitors.[57][58] The Zoological Society of London states in its charter that its aim is "the advancement of Zoology and Animal Physiology and the introduction of new and curious subjects of the Animal Kingdom." It maintains two research institutes, the Nuffield Institute of Comparative Medicine and the Wellcome Institute of Comparative Physiology. In the United States, the Penrose Research Laboratory of the Philadelphia Zoo focuses on the study of comparative pathology.[10] The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums produced its first conservation strategy in 1993, and in November 2004, it adopted a new strategy that sets out the aims and mission of zoological gardens of the 21st century.[59] When studying behaviour of captive animals, several things should however be taken into account before drawing conclusions about wild populations. Including that captive populations are often smaller than wild ones and that the space available to each animal is often less than in the wild.[60]

Conservation programs all over the world fight to protect species from going extinct, but many conservation programs are underfunded and under-represented. Conservation programs can struggle to fight bigger issues like habitat loss and illness. It often takes significant funding and long time periods to rebuild degraded habitats, both of which are scarce in conservation efforts. The current state of conservation programs cannot rely solely in situ (on-site conservation) plans alone, ex situ (off-site conservation) may therefore provide a suitable alternative. Off-site conservation relies on zoos, national parks, or other care facilities to support the rehabilitation of the animals and their populations. Zoos benefit conservation by providing suitable habitats and care to endangered animals. When properly regulated, they present a safe, clean environment for the animals to increase populations sizes. A study on amphibian conservation and zoos addressed these problems by writing,

Whilst addressing in situ threats, particularly habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation, is of primary importance; for many amphibian species in situ conservation alone will not be enough, especially in light of current un-mitigatable threats that can impact populations very rapidly such as chytridiomycosis [an infectious fungal disease]. Ex situ programmes can complement in situ activities in a number of ways including maintaining genetically and demographically viable populations while threats are either better understood or mitigated in the wild[61]

The breeding of endangered species is coordinated by cooperative breeding programmes containing international studbooks and coordinators, who evaluate the roles of individual animals and institutions from a global or regional perspective, and there are regional programmes all over the world for the conservation of endangered species. In Africa, conservation is handled by the African Preservation Program (APP);[62] in the U.S. and Canada by Species Survival Plans;[63] in Australasia, by the Australasian Species Management Program;[64] in Europe, by the European Endangered Species Program;[65] and in Japan, South Asia, and South East Asia, by the Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums, the South Asian Zoo Association for Regional Cooperation, and the South East Asian Zoo Association.

Positive impacts on local wildlife

[edit]

Besides conservation of captive species, large zoos may form a suitable environment for wild native animals such as herons to live in or visit. A colony of black-crowned night herons has regularly summered at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. for more than a century.[66] Some zoos may provide information to visitors on wild animals visiting or living in the zoo, or encourage them by directing them to specific feeding or breeding platforms.[67][68]

In addition to these potential positive impacts, Milstein proposes that zoos can transform their practices by increasing their focus on wildlife rescue and care, and by making better use of online platforms to situate species of interest within their wider ecologies.[69] Such changes may enhance public education and encourage audiences to participate in projects and campaigns that limit the ecologically destructive process putting local wildlife at risk in the first place.

Animal welfare in zoos

[edit]

The welfare of zoo animals varies widely including its level. Some zoos work to improve their animal enclosures and make it fit the animals' needs, but constraints such as size and expense can complicate this.[70][71] The type of enclosure and the husbandry are of great importance in determining the welfare of animals. Substandard enclosures can lead to decreased lifespans, caused by factors as human diseases, unsafe materials in the cages and possible escape attempts. However, when zoos take time to think about the animal's welfare, zoos can become a place of refuge. Today, many zoos are improving enclosures by including tactile and sensory features in the habitat that allow animals to encourage natural behaviors. These additions can prove to be effective in improving the lives of animals in captivity. The tactile and sensory features will vary depending on the species of animal.[72] There are animals that are injured in the wild and are unable to survive on their own, but in the zoos they can live out the rest of their lives healthy and happy. In recent years, some zoos have chosen to move out some larger animals because they do not have the space available to provide an adequate enclosure for them. However, those cannot avoid the fundamental issue of commercially exploiting beings that are inherently deserving of respect, and infringing upon their freedom.

An issue with animal welfare in zoos is that best animal husbandry practices are often not completely known, especially for species that are only kept in a small number of zoos.[60] To solve this organizations like EAZA and AZA have begun to develop husbandry manuals.[73][74]

Problems

[edit]Capture in wild and mortality

[edit]In modern, well-regulated zoos, breeding is controlled to maintain a self-sustaining, global captive population. This is not the case in some less well-regulated zoos, often based in poorer regions. Overall "stock turnover" of animals during a year in a select group of poor zoos was reported as 20%-25% with 75% of wild caught apes dying in captivity within the first 20 months.[75] The authors of the report stated that before successful breeding programs, the high mortality rate was the reason for the "massive scale of importations."

One 2-year study indicated that of 19,361 mammals that left accredited zoos in the U.S. between 1992 and 1998, 7,420 (38%) went to dealers, auctions, hunting ranches, unaccredited zoos and individuals, and game farms.[76]

Behavioural restriction

[edit]Many modern zoos attempt to improve animal welfare by providing more space and behavioural enrichments. This often involves housing the animals in naturalistic enclosures that allow the animals to express more of their natural behaviours, such as roaming and foraging. Whilst many zoos have been working hard on this change, in some zoos, some enclosures still remain barren concrete enclosures or other minimally enriched cages.[77]

Sometimes animals are unable to perform certain behaviors in zoos, like seasonal migration or traveling over large distances. Whether these behaviors are necessary for good welfare however is unclear. Some behaviors are seen as essential for an animal's welfare whilst others are not.[78] It is however shown that even in limited spaces, certain natural behaviors can still be performed. A study in 2014 for example found that Asian elephants in zoos covered similar or higher walking distances when compared to sedentary wild populations.[79] Migration in the wild can also be related to food scarcity or other unfavorable environmental problems.[80] However a proper zoo enclosure never runs out of food or water, and in case of unfavorable temperatures or weather animals are provided with (indoor) shelter.

Abnormal behaviour

[edit]Animals in zoos can exhibit behaviors that are abnormal in their frequency, intensity, or would not normally be part of their behavioural repertoire. Whilst these types of behaviors can be a sign of bad welfare and stress, this is not necessarily the case. Other measurements or behavioral research is advised before determining whether an animal performing stereotypical behavior is living in bad welfare or not.[81] Examples of stereotypical behaviors are pacing, head-bobbing, obsessive grooming and feather-plucking[82] A study examining data collected over four decades found that polar bears, lions, tigers and cheetahs can display stereotypical behaviors in many older exhibits. However they also noted that in more modern naturalistic exhibits, these behaviors could completely disappear.[83] Elephants have also been recorded displaying stereotypical behaviours in the form of swaying back and forth, trunk swaying or route tracing. This has been observed in 54% of individuals in UK zoos.[84] However it has been shown that modern facilities and modern husbandry can greatly decrease or even entirely remove abnormal behaviors. A study of a group of elephants in Planckendael showed that the older wild-caught animals displayed many stereotypical behaviors. These elephants had spent part of their lives either in a circus or in other substandard enclosures. On the other hand, the elephants born in the modern facilities that had lived in a herd their whole life barely displayed any stereotypical behaviors at all.[85] The life history of an animal is thus extremely important when analyzing the causes of stereotypical behavior, as this can be a historical relict instead of a result of present-day husbandry.

Some zoos have used psychoactive drugs, such as Prozac, in attempting to stop animals from exhibiting the behaviors.[86]

Longevity

[edit]The influence on a zoological environment on animal's longevity is not straightforward. A study of 50 mammal species found that 84% of them lived longer in zoos than they would in the wild on average.[87] On the other hand, some research claims that elephants in Japanese zoos would live shorter than their wild counterparts at just 17 years. This has been refuted by other studies however.[88] Such studies might not yet fully represent recent improvements in husbandry. For example, studies show that captive-bred elephants already have a lower mortality risk then wild-caught ones.[89]

Climate conditions

[edit]Climatic conditions can make it difficult to keep some animals in zoos in some locations. For example, Alaska Zoo had an elephant named Maggie. She was housed in a small, indoor enclosure because the outdoor temperature was too low.[90][91]

Epidemiology

[edit]Tsetse flies have invaded zoos that have been established in the tsetse zone. More concerning, tsetse-borne species of trypanosomes have entered zoos outside the traditional tsetse zone in infected animals imported and added to their collections. Whether these can be controlled depends on several factors: Vale 1998 found that the technique used in placing attractants was important; and Green 1988, Torr 1994, Torr et al. 1995, and Torr et al. 1997 found the availability for specifically needed attractants for the specific job to also vary widely.[92][93]

Moral criticism

[edit]Some critics and many animal rights activists argue that zoo animals are treated as voyeuristic objects, rather than living creatures, and often suffer due to the transition from being free and wild to captivity.[94] Ever since imports of wild-caught animals can became more regulated by organizations like CITES and national laws, zoos have started sustaining their populations via breeding. This change started around the 1970s. Many corporations in the form of breeding programs have been set up since, for both common and endangered species.[95][96][97] Emma Marris, writing an opinion piece for The New York Times, suggested zoos "stopped breeding all their animals, with the possible exception of any endangered species with a real chance of being released back into the wild ... Eventually, the only animals on display would be a few ancient holdovers from the old menageries, animals in active conservation breeding programs and perhaps a few rescues. Such zoos might even be merged with sanctuaries."[98]

In 2017, activist travel company Responsible Travel and anti-captive animal charity the Born Free Foundation conducted an independent survey of 1,000 members of the UK public who had visited a zoo in the previous five years, to gauge public understanding of zoos' contribution to conservation. The results showed that zoos spend on average ten times less than visitors expect on conservation. It also emerged that three-quarters of visitors would expect at least one-fifth of the animals in a zoo to be endangered. The actual figure, according to the Born Free Foundation, is 10%.[99]

In light of these findings and ongoing animal welfare concerns,[100] in 2017, Responsible Travel became the first travel company to stop promoting holidays that include visits to a zoo.[101]

Live feeding

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with China and the United Kingdom and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (January 2022) |

In some countries, feeding live vertebrates to zoo animals is illegal under most circumstances. The UK Animal Welfare Act of 2006, for example, states that prey must be killed for feeding, unless this threatens the health of the predator.[102] Some zoos had already adopted such practices prior to the implementation of such policies. London Zoo, for example, stopped feeding live vertebrates in the 20th century, long before the Animal Welfare Act.[102] Despite being illegal in China, some zoos have been found to still feed live vertebrates to their predators. In some parks like Xiongsen Bear and Tiger Mountain Village, live chickens and other livestock were found to be thrown into the enclosures of tigers and other predators. In Guilin, in south-east China, live cows and pigs are thrown to tigers to amuse visitors. Other Chinese parks like Shenzhen Safari Park have already stopped this practice after facing heavy criticism.[103]

Regulation

[edit]

United States

[edit]In the United States, any public animal exhibit must be licensed and inspected by the Department of Agriculture, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Depending on the animals they exhibit, the activities of zoos are regulated by laws including the Endangered Species Act, the Animal Welfare Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 and others.[104]

Additionally, zoos in several countries may choose to pursue accreditation by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), which originated in the U.S. To achieve accreditation, a zoo must pass an application and inspection process and meet or exceed the AZA's standards for animal health and welfare, fundraising, zoo staffing, and involvement in global conservation efforts. Inspection is performed by three experts (typically one veterinarian, one expert in animal care, and one expert in zoo management and operations) and then reviewed by a panel of twelve experts before accreditation is awarded. This accreditation process is repeated once every five years. The AZA estimates that there are approximately 2,400 animal exhibits operating under USDA license as of February 2007; fewer than 10% are accredited.[105]

Europe

[edit]The European Union introduced a directive to strengthen the conservation role of zoos, making it a statutory requirement that they participate in conservation and education, and requiring all member states to set up systems for their licensing and inspection.[106] Zoos are regulated in the UK by the Zoo Licensing Act of 1981, which came into effect in 1984. A zoo is defined as any "establishment where wild animals are kept for exhibition [...] to which members of the public have access, with or without charge for admission, seven or more days in any period of twelve consecutive months", excluding circuses and pet shops. The Act requires that all zoos be inspected and licensed, and that animals kept in enclosures are provided with a suitable environment in which they can express most normal behavior.[106]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Zoo | Animals & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ "Landmarks in ZSL History" Archived 2020-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, Zoological Society of London and Princess Margareta Hohenzolern Duda move in Zoo withK kinga Tanajewska ( daughter,n 1981 ).

- ^ "Visitor Demographics". Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ a b Blunt 1976; Reichenbach 2002, pp. 151–163.

- ^ Hyson 2000, p. 29; Hyson 2003, pp. 1356–1357.

- ^ Maple 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Robinson 1987a, pp. 10–17; Robinson 1987b, pp. 678–682.

- ^ Conway 1995, pp. 259–276.

- ^ World's First Zoo - Hierakonpolis, Egypt, Archaeology Magazine, http://www.archaeology.org/1001/topten/egypt.html Archived 2010-07-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e "Zoo". Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Lecky, W.E.H. History of European Morals from Augustus to Charlemagne. Vol. 1, Longmans, 1869, pp. 280–282.

- ^ a b Blunt, Wilfred. The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century. Hamish Hamilton, 1976, pp. 15–17.

- ^ "Big cats prowled London's tower" , BBC News, October 24, 2005.

- ^ Martín del Campo y Sánchez, Rafael. "El parque zoológico de Moctezuma en Tenochtitlán" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ M.G. Ash, ed., Mensch, Tier und Zoo – der Tiergarten Schönbrunn im internationalen Vergleich vom 18. Jahrhundert bis heute(Vienna: Böhlau, 2008).

- ^ Pierre Serna, "The republican menagerie: animal politics in the French Revolution." French History 28.2 (2014): 188–206.

- ^ Brown, Tim (2014-01-01). "'Zoo proliferation'—The first British Zoos from 1831–1840". Der Zoologische Garten. 83 (1): 17–27. Bibcode:2014DZGar..83...17B. doi:10.1016/j.zoolgart.2014.05.002. ISSN 0044-5169. Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

in the years immediately after the establishment of the London Zoo, ... Britain had a number of these institutions when other countries did not have any or, at most, one such place

- ^ "Introducing the Modern Zoo". Zoological Society of London. Archived from the original on 2013-12-14.

- ^ "April 27". Today in Science History. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ a b "ZSL's History". ZSL. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- ^ "The Role of Architectural Design in Promoting the Social Objectives of Zoos". Archived from the original on 2013-04-12. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ^ Costello, John (June 9, 2011). "The great zoo's who". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ Stewart, Herbert Leslie (29 December 2017). "The Dalhousie Review". Dalhousie University Press. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ McGregor, Phlis (4 September 2015). "Halifax's first zoo is well-kept secret of Fairmount history". CBC News. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Punch, Terry (May–June 2006). "Zoo Diary". Saltscapes Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017.

- ^ Rene S. Ebersole (November 2001). "The New Zoo". Audubon Magazine. National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ^ Nigel Rothfels, Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo (2008)

- ^ "Wielkie liczenie w zoo we Wrocławiu. Zobacz, ile zwierząt w nim mieszka" [Counting great at the zoo in Wrocław. See how many animals live in it]. wroclaw.wyborcza.pl (in Polish). January 19, 2016. Archived from the original on May 6, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ Isler, Danuta. "A trip to Wroclaw Afrykarium". Radio Poland. Archived from the original on 2018-07-13. Retrieved 2018-07-13.

- ^ Jesse C. Donahue, and Erik K. Trump, American zoos during the depression: a new deal for animals (McFarland, 2014).

- ^ Francis Desiderio, "Raising the Bars: The Transformation of Atlanta's Zoo, 1889-2000." Atlanta History 18.4 (2000): 8–64.

- ^ See Association of Zoos & Aquariums, 2020 Archived 2020-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Daniel E. Bender, The Animal Game: Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo (Harvard University Press, 2016).

- ^ Ian Jared Miller, and Harriet Ritvo, The Nature of the Beasts: Empire and Exhibition at the Tokyo Imperial Zoo (2013) pp. 4, 99–105. excerpt Archived 2021-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aso Noriko, Public Properties: Museums in Imperial Japan (Duke UP, 2014).

- ^ See Kisling, Vernon N. (ed.): Zoo and Aquarium History, Boca Raton 2001. ISBN 0-8493-2100-X; Hoage, R. J. Deiss and William A. (ed.): New Worlds, New Animals, Washington 1996. ISBN 0-8018-5110-6; Hanson, Elizabeth. Animal Attractions, Princeton 2002. ISBN 0-691-05992-6; and Hancocks, David. A Different Nature, Berkeley 2001. ISBN 0-520-21879-5

- ^ Donahue, Jesse and Trump, Erik. Political Animals: Public Art in American Zoos and Aquariums. Lexington Books, 2007, p. 79.

- ^ a b Masci, David. "Zoos in the 21st Century." CQ Researcher 28 Apr. 2000: 353–76. Web. 26 Jan. 2014.

- ^ Bradford, Phillips Verner and Blume, Harvey. Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo. St. Martins Press, 1992.

- ^ "Man and Monkey Show Disapproved by Clergy" Archived 2016-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, September 10, 1906.

- ^ Blanchard, Pascal; Bancel, Nicolas; and Lemaire, Sandrine. "From human zoos to colonial apotheoses: the era of exhibiting the Other" Archived April 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Africultures.

- ^ Ferral, Katelyn (2010-07-15). "N.C. Zoo, bucking a trend, sets an attendance record". Newsobserver.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- ^ Guzoo Animal Farm Archived May 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, website about Canadian roadside zoos, accessed June 18, 2009.

- ^ Roadside zoo animals starving. Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine Free Lance-Star. 11 Jan. 1997.

- ^ Dixon, Jennifer. House panel told of abuses by zoos. Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine Times Daily. 8 July 1992.

- ^ Elwood, Ian (8 April 2014). "Animal Abandonment is a Crime". Animal Legal Defense Fund. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017.

- ^ "- APHIS Inspection Report of Cricket Hollow Zoo, May 21 2014".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Zoo: Procurement and care of animals," Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ a b "Population Q&A". Zooquaria. Autumn 2016 (94). EAZA: 32–33.

- ^ a b c d e Kleiman, Thompson and Baer (2010). Wild Mammals in Captivity. University of Chicago Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-0-226-44009-5.

- ^ Hunn, D. (February 16, 2014). "What happens when zoo contraceptives work too well?". St. Louis Dispatch. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ a b "Marius The Giraffe Was Not Alone: Zoos in Europe Kill 5,000 Healthy Animals Annually". Huffington Post. February 27, 2014. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ Johnston, I. (February 9, 2014). "Copenhagen Zoo kills 'surplus' young giraffe Marius despite online petition". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved February 10, 2014.

- ^ Ralls, Katherine (2001). Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. Smithsonian Institution USA. pp. 599–607.

- ^ "Reintroduction Programs". American Association of Zoos and Aquariums. 2022.

- ^ Carrie Friese (2013). Cloning Wild Life: Zoos, Captivity, and the Future of Endangered Animals. NYU Press. p. 3 and 14. ISBN 9780814729106.

- ^ Tudge, Colin. Last Animals in the Zoo: How Mass Extinction Can Be Stopped, London 1991. ISBN 1-55963-157-0

- ^ "Manifesto for Zoos" Archived August 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, John Regan Associates, 2004.

- ^ "World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Strategy" Archived 2007-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, World Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

- ^ a b Rowden, Lewis J.; Rose, Paul E. (2016). "A global survey of banteng (Bos javanicus) housing and husbandry: Banteng Husbandry Survey". Zoo Biology. 35 (6): 546–555. doi:10.1002/zoo.21329. hdl:10871/24538. PMID 27735990.

- ^ Brady, Leanna; Young, Richard; Goetz, Matthias; Dawson, Jeff (October 2017). "Increasing zoo's conservation potential through understanding barriers to holding globally threatened amphibians". Biodiversity and Conservation. 26 (11): 2736 (or 2). Bibcode:2017BiCon..26.2735B. doi:10.1007/s10531-017-1384-y. S2CID 24619590. ProQuest 1943858410.

- ^ African Association of Zoological Gardens and Aquaria

- ^ American Zoo and Aquarium Association Archived 2011-02-22 at the Wayback Machine and the Canadian Association of Zoos and Aquariums Archived 2010-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "AquaZoos - Educational Writing Group". AquaZoos. Archived from the original on February 2, 2007.

- ^ "European Association of Zoos and Aquaria » EAZA". www.eaza.net. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Akpan, Nsikan (12 May 2015). "Smithsonian's mystery of the black-crowned night herons solved by satellites". PBS NewsHour. PBS. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Birdworld Animals". Birdworld. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Graureiher". Tiergarten Schoenbrunn. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ Milstein, Tema (2009). "Somethin' Tells Me It's All Happening at the Zoo". Environmental Communication. 3: 25–48.

- ^ Norton, Bryan G.; Hutchins, Michael; Stevens, Elizabeth F.; Maple, Terry L. (ed.): Ethics on the Ark. Zoos, Animal Welfare, and Wildlife Conservation. Washington, D.C., 1995. ISBN 1-56098-515-1

- ^ Malmud, Randy. Reading Zoos. Representations of Animals and Captivity. New York, 1998. ISBN 0-8147-5602-6

- ^ Beer, Haley N.; Shrader, Trenton C.; Schmidt, Ty B.; Yates, Dustin T. (December 2023). "The Evolution of Zoos as Conservation Institutions: A Summary of the Transition from Menageries to Zoological Gardens and Parallel Improvement of Mammalian Welfare Management". Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens. 4 (4): 648–664. doi:10.3390/jzbg4040046. ISSN 2673-5636.

- ^ "PROGRAMMES » EAZA". www.eaza.net. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ "Animal Care Manuals | Association of Zoos & Aquariums". www.aza.org. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-01-24.

- ^ Jensen, Derrick and Tweedy-Holmes Karen. Thought to exist in the wild: awakening from the nightmare of zoos. No Voice Unheard, 2007, p. 21; Baratay, Eric and Hardouin-Fugier, Elisabeth. Zoo: A History of the Zoological Gardens of the West. Reaktion, London. 2002.

- ^ Goldston, Linda. February 11, 1999, cited in Scully, Matthew. Dominion. St. Martin's Griffin, 2004 (paperback), p. 64.

- ^ Masci, D. (2000). "Zoos in the 21st century". CQ Researcher: 353–76. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2016-12-16.

- ^ Veasey, Jake & Waran, Natalie & Young, Robert. (1996). On Comparing the Behaviour of Zoo Housed Animals with Wild Conspecifics as a Welfare Indicator. Animal Welfare. 5. 13–24.

- ^ Rowell, Z. E. (2014). Locomotion in captive Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, 2(4), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v2i4.50 Archived 2021-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "How and Why Animals Migrate - NatureWorks". nhpbs.org. Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Mason, Georgia & Latham, N.R.. (2004). Can't stop, won't stop: Is stereotypy a reliable animal welfare indicator?. Animal Welfare. 13. 57–69.

- ^ "Are Zoos good or bad for animals?". Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ Derr, Mark. "Big Beasts, Tight Space and a Call for Change in Journal Report," The New York Times, October 2, 2003.

- ^ Harris, M.; Sherwin, C.; Harris, S. (10 November 2008). "Defra Final Report on Elephant Welfare" (PDF). University of Bristol. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Vleugels. E. (2016). Onderzoek naar stereotyp, agressief en dominant gedrag en locatiegebruik bij een groep Aziatische olifanten gehuisvest in Planckendael, UNIVERSITEIT GENT FACULTEIT DIERGENEESKUNDE

- ^ Braitman, Laurel. "Even the Gorillas and Bears in Our Zoos Are Hooked on Prozac". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ Tidière, M., Gaillard, JM., Berger, V. et al. Comparative analyses of longevity and senescence reveal variable survival benefits of living in zoos across mammals. Sci Rep 6, 36361 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36361 Archived 2021-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mott, M. (11 December 2008). "Wild elephants live longer than their zoo counterparts". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Lahdenperä M, Mar KU, Courtiol A, Lummaa V. Differences in age-specific mortality between wild-caught and captive-born Asian elephants [published correction appears in Nat Commun. 2018 Aug 28;9(1):3544]. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3023. Published 2018 Aug 7. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05515-8

- ^ Kershaw, Sarah (10 January 2005). "Alaska's lone zoo elephant heats up national debate". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Pemberton, Mary (11 January 2007). "Alaska's only elephant heads to California". NBC. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ Mbaya, A. W.; Aliyu, M. M.; Ibrahim, U. I. (2009-04-02). "The clinico-pathology and mechanisms of trypanosomosis in captive and free-living wild animals: A review". Veterinary Research Communications. 33 (7). Springer: 793–809. doi:10.1007/s11259-009-9214-7. ISSN 0165-7380. PMID 19340600. S2CID 23405683.

- ^ Adler, Peter H.; Tuten, Holly C.; Nelder, Mark P. (2011-01-07). "Arthropods of Medicoveterinary Importance in Zoos". Annual Review of Entomology. 56 (1). Annual Reviews: 123–142. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144741. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 20731604.

- ^ Jensen, p. 48.

- ^ "Where do our animals come from and where do they go?". Zoological Society of London (ZSL). Archived from the original on 2020-11-02. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ "About The Zoological Society - Zoological Society of Milwaukee". Zoological Society of Milwaukee. Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "PROGRAMMES » EAZA". www.eaza.net. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ Marris, Emma (2021-06-11). "Opinion | Modern Zoos Are Not Worth the Moral Cost". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-10-20.

- ^ "Are zoos as good for wildlife as they make out? | Responsible Travel". www.responsibletravel.com. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "ZOOS AND AQUARIA". www.bornfree.org.uk. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ @NatGeoUK (2017-05-31). "Hot topic: is it time for zoos to be banned?". National Geographic. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b "Live-Feeding Prey to Captive Predators". Faunalytics. October 17, 2014. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Ferocity training". Sunday Morning Post, Hong Kong. November 29, 1999. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- ^ Grech, Kali S. "Overview of the Laws Affecting Zoos" Archived 2012-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, Michigan State University College of Law, Animal Legal & Historical Center, 2004.

- ^ "AZA Accreditation Introduction". Archived from the original on November 2, 2007.

- ^ a b "The Zoo Licensing Act 1981" Archived May 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs.

Further reading

[edit]- Baratay, Eric, and Elizabeth Hardouin-Fugier. (2002) History of Zoological Gardens in the West

- Blunt, Wilfrid (1976). The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century, Hamish Hamilton, London. ISBN 0-241-89331-3 online

- Braverman, Irus (2012). Zooland: The Institution of Captivity, Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804783576 excerpt Archived 2021-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Bruce, Gary. (2017) Through the Lion Gate: A History of the Berlin Zoo excerpt Archived 2021-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Conway, William (1995). "The conservation park: A new zoo synthesis for a changed world", in The Ark Evolving: Zoos and Aquariums in Transition, Wemmer, Christen M. (ed.), Smithsonian Institution Conservation and Research Center, Front Royal, Virginia.

- Donahue, Jesse C., and Erik K. Trump. (2014) American zoos during the depression: a new deal for animals (McFarland, 2014).

- Fisher, James. (1967) Zoos of the World: The Story of Animals in Captivity, popular history

- Hancocks, David. A Different Nature: The Paradoxical World of Zoos and Their Uncertain Future (2003) excerpt

- Hardouin-Fugier, Elisabeth. (2004) Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West

- Hyson, Jeffrey (2000). "Jungle of Eden: The Design of American Zoos" in Environmentalism in Landscape Architecture, Conan, Michel (ed.), Dumbarton Oaks, Washington. ISBN 0-88402-278-1

- Hochadel, Oliver. "Watching Exotic Animals Next Door: 'Scientific' Observations at the Zoo (ca. 1870–1910)."Science in Context(June 2011) 24#2 pp 183–214. online Archived 2021-08-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Hyson, Jeffrey (2003). "Zoos," in Krech III, Shepard; Merchant, Carolyn; McNeill, John Robert, eds. (2004). Encyclopedia of World Environmental History. Vol. 3: O–Z, Index. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-93735-1.

- The International Zoo Yearbook, annual since 1959 from the Zoological Society of London.

- Kohler, Robert E. (2006). All Creatures: Naturalists, Collectors, and Biodiversity, 1850–1950 (Princeton University Press).

- Kisling, Vernon N., ed. (2001) Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections to Zoological Gardens (2001) excerpt Archived 2016-01-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- Maddeaux, Sarah-Joy. (2014) "A 'delightful resort for persons of all ages, and more especially for the young': Children at Bristol Zoo Gardens, 1835–1940." Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 7.1 (2014): 87–106 excerpt.

- Maple, Terry (1995). "Toward a Responsible Zoo Agenda", in Ethics on the Ark: Zoos, Animal Welfare, and Wildlife Conservation, Norton, Bryan G., Hutchins, Michael, Stevens, Elizabeth F. and Maple, Terry L. (ed.), Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington. ISBN 1-56098-515-1

- Meuser, Natascha (2019). Zoo Buildings. Construction and Design Manual. DOM publishers, Berlin. ISBN 978-3-86922-680-4

- Miller, Ian Jared, and Harriet Ritvo. The Nature of the Beasts: Empire and Exhibition at the Tokyo Imperial Zoo (2013) excerpt

- Murphy, James B. (2007) Herpetological History of the Zoo & Aquarium World

- Reichenbach, Herman (2002). "Lost Menageries: Why and How Zoos Disappear (Part 1)", International Zoo News Vol.49/3 (No.316), April–May 2002.

- Robinson, Michael H. (1987a). "Beyond the zoo: The biopark", Defenders of Wildlife Magazine, Vol. 62, No. 6.

- Robinson, Michael H. (1987b). "Towards the Biopark: The Zoo That Is Not", American Association of Zoological Parks and Aquariums, Annual Proceedings.

- Rothfels, Nigel. (2008) Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo excerpt

- Vandersommers, Daniel. (2023) Entangled Encounters at the National Zoo: Stories from the Animal Archive (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2023).

- Woods, Abigail. (2018) "Doctors in the Zoo: Connecting Human and Animal Health in British Zoological Gardens, c. 1828–1890." In Animals and the Shaping of Modern Medicine (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018), pp. 27–69.

External links

[edit]- Zoos Worldwide Zoos, aquariums, animal sanctuaries and wildlife parks

- Zoological Gardens keeping Asian Elephants

- The Bartlett Society: Devoted to studying yesterday's methods of keeping wild animals, download page