Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Three-phase electric power

View on Wikipedia

Three-phase electric power (abbreviated 3ϕ)[1] is the most widely used form of alternating current (AC) for electricity generation, transmission, and distribution.[2] It is a type of polyphase system that uses three wires (or four, if a neutral return is included) and is the standard method by which electrical grids deliver power around the world.

In a three-phase system, each of the three voltages is offset by 120 degrees of phase shift relative to the others. This arrangement produces a more constant flow of power compared with single-phase systems, making it especially efficient for transmitting electricity over long distances and for powering heavy loads such as industrial machinery. Because it is an AC system, voltages can be easily increased or decreased with transformers, allowing high-voltage transmission and low-voltage distribution with minimal loss.

Three-phase circuits are also more economical: a three-wire system can transmit more power than a two-wire single-phase system of the same phase-to-phase voltage while using less conductor material.[3] Beyond transmission, three-phase power is commonly used to run large induction motors, other electric motors, and heavy industrial loads, while smaller devices and household equipment often rely on single-phase circuits derived from the same network.

Three-phase electrical power was first developed in the 1880s by several inventors and has remained the backbone of modern electrical systems ever since.

Terminology

[edit]The conductors between a voltage source and a load are called lines, and the voltage between any two lines is called line voltage. The voltage measured between any line and neutral is called phase voltage.[4] For example, in countries with nominal 230 V power, the line voltage is 400 V and the phase voltage is 230 V. For a 208/120 V service, the line voltage is 208 V and the phase voltage is 120 V.

History

[edit]Polyphase power systems were independently invented by Galileo Ferraris, Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky, Jonas Wenström, John Hopkinson, William Stanley Jr., and Nikola Tesla in the late 1880s.[5]

Three phase power evolved out of electric motor development. In 1885, Galileo Ferraris was doing research on rotating magnetic fields. Ferraris experimented with different types of asynchronous electric motors. The research and his studies resulted in the development of an alternator, which may be thought of as an alternating-current motor operating in reverse, so as to convert mechanical (rotating) power into electric power (as alternating current). On 11 March 1888, Ferraris published his research in a paper to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin.[6]

Two months later Nikola Tesla gained U.S. patent 381,968 for a three-phase electric motor design, application filed October 12, 1887. Figure 13 of this patent shows that Tesla envisaged his three-phase motor being powered from the generator via six wires.

These alternators operated by creating systems of alternating currents displaced from one another in phase by definite amounts, and depended on rotating magnetic fields for their operation. The resulting source of polyphase power soon found widespread acceptance. The invention of the polyphase alternator is key in the history of electrification, as is the power transformer. These inventions enabled power to be transmitted by wires economically over considerable distances. Polyphase power enabled the use of water-power (via hydroelectric generating plants in large dams) in remote places, thereby allowing the mechanical energy of the falling water to be converted to electricity, which then could be fed to an electric motor at any location where mechanical work needed to be done. This versatility sparked the growth of power-transmission network grids on continents around the globe.

Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky developed a three-phase electrical generator and a three-phase electric motor in 1888 and studied star and delta connections.[7][8][9] His three-phase three-wire transmission system was displayed in 1891 in Germany at the International Electrotechnical Exhibition, where Dolivo-Dobrovolsky used the system to transmit electric power at the distance of 176 km (110 miles) with 75% efficiency. In 1891 he also created a three-phase transformer and short-circuited (squirrel-cage) induction motor.[10][11][12] He designed the world's first three-phase hydroelectric power plant in 1891.[13] Inventor Jonas Wenström received in 1890 a Swedish patent on the same three-phase system.[14] The possibility of transferring electrical power from a waterfall at a distance was explored at the Grängesberg mine. A 45 m fall at Hällsjön, Smedjebackens kommun, where a small iron work had been located, was selected. In 1893, a three-phase 9.5 kV system was used to transfer 400 horsepower (300 kW) a distance of 15 km (10 miles), becoming the first commercial application.[15]

Principle

[edit]

In a symmetric three-phase power supply system, three conductors each carry an alternating current of the same frequency and voltage amplitude relative to a common reference, but with a phase difference of one third of a cycle (i.e., 120 degrees out of phase) between each. The common reference is usually connected to ground and often to a current-carrying conductor called the neutral. Due to the phase difference, the voltage on any conductor reaches its peak at one third of a cycle after one of the other conductors and one third of a cycle before the remaining conductor. This phase delay gives constant power transfer to a balanced linear load. It also makes it possible to produce a rotating magnetic field in an electric motor and generate other phase arrangements using transformers (for instance, a two-phase system using a Scott-T transformer). The amplitude of the voltage difference between two phases is times the amplitude of the voltage of the individual phases.

The symmetric three-phase systems described here are simply referred to as three-phase systems because, although it is possible to design and implement asymmetric three-phase power systems (i.e., with unequal voltages or phase shifts), they are not used in practice because they lack the most important advantages of symmetric systems.

In a three-phase system feeding a balanced and linear load, the sum of the instantaneous currents of the three conductors is zero. In other words, the current in each conductor is equal in magnitude to the sum of the currents in the other two, but with the opposite sign. The return path for the current in any phase conductor is the other two phase conductors.

Constant power transfer is possible with any number of phases greater than one. However, two-phase systems do not have neutral-current cancellation and thus use conductors less efficiently, and more than three phases complicates infrastructure unnecessarily. Additionally, in some practical generators and motors, two phases can result in a less smooth (pulsating) torque.[16]

Three-phase systems may have a fourth wire, common in low-voltage distribution. This is the neutral wire. The neutral allows three separate single-phase supplies to be provided at a constant voltage and is commonly used for supplying multiple single-phase loads. The connections are arranged so that, as far as possible in each group, equal power is drawn from each phase. Further up the distribution system, the currents are usually well balanced. Transformers may be wired to have a four-wire secondary and a three-wire primary, while allowing unbalanced loads and the associated secondary-side neutral currents.

Phase sequence

[edit]Wiring for three phases is typically identified by colors that vary by country and voltage. The phases must be connected in the correct order to achieve the intended direction of rotation of three-phase motors. For example, pumps and fans do not work as intended in reverse. Maintaining the identity of phases is required if two sources could be connected at the same time. A direct connection between two different phases is a short circuit and leads to flow of unbalanced current.

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]As compared to a single-phase AC power supply that uses two current-carrying conductors with no neutral, a three-phase supply with no neutral and the same phase-to-phase voltage can transmit the same power by using just 0.75 times as much conductor material.[a][3]

Three-phase supplies have properties that make them desirable in electric power distribution systems:

- The phase currents tend to cancel out one another, summing to zero in the case of a linear balanced load, which allows a reduction of the size of the neutral conductor because it carries little or no current. With a balanced load, all the phase conductors carry the same current and so can have the same size.

- Power transfer into a linear balanced load is constant, which, in motor/generator applications, helps to reduce vibrations.

- Three-phase systems can produce a rotating magnetic field with a specified direction and constant magnitude, which simplifies the design of electric motors, as no starting circuit is required.

However, most loads are single-phase. In North America, single-family houses and individual apartments are supplied one phase from the power grid and use a split-phase system to the panelboard from which most branch circuits will carry 120 V. Circuits designed for higher powered devices such as stoves, dryers, or outlets for electric vehicles carry 240 V.

In Europe, three-phase power is normally delivered to the panelboard and further to higher powered devices.

Generation and distribution

[edit]

At the power station, an electrical generator converts mechanical power into a set of three AC electric currents, one from each coil (or winding) of the generator. The windings are arranged such that the currents are at the same frequency but with the peaks and troughs of their wave forms offset to provide three complementary currents with a phase separation of one-third cycle (120° or 2π⁄3 radians). The generator frequency is typically 50 or 60 Hz, depending on the country.

At the power station, transformers change the voltage from generators to a level suitable for transmission in order to minimize losses.

After further voltage conversions in the transmission network, the voltage is finally transformed to the standard utilization before power is supplied to customers.

Most automotive alternators generate three-phase AC and rectify it to DC with a diode bridge.[19]

Transformer connections

[edit]A "delta" (Δ) connected transformer winding is connected between phases of a three-phase system. A "wye" (Y) transformer connects each winding from a phase wire to a common neutral point.

A single three-phase transformer can be used, or three single-phase transformers.

In an "open delta" or "V" system, only two transformers are used. A closed delta made of three single-phase transformers can operate as an open delta if one of the transformers has failed or needs to be removed.[20] In open delta, each transformer must carry current for its respective phases as well as current for the third phase, therefore capacity is reduced to 87%. With one of three transformers missing and the remaining two at 87% efficiency, the capacity is 58% (2⁄3 of 87%).[21][22]

Where a delta-fed system must be grounded for detection of stray current to ground or protection from surge voltages, a grounding transformer (usually a zigzag transformer) may be connected to allow ground fault currents to return from any phase to ground. Another variation is a "corner grounded" delta system, which is a closed delta that is grounded at one of the junctions of transformers.[23]

Three-wire and four-wire circuits

[edit]

There are two basic three-phase configurations: wye (Y) and delta (Δ). As shown in the diagram, a delta configuration requires only three wires for transmission, but a wye (star) configuration may have a fourth wire. The fourth wire, if present, is provided as a neutral and is normally grounded. The three-wire and four-wire designations do not count the ground wire present above many transmission lines, which is solely for fault protection and does not carry current under normal use.

A four-wire system with symmetrical voltages between phase and neutral is obtained when the neutral is connected to the "common star point" of all supply windings. In such a system, all three phases will have the same magnitude of voltage relative to the neutral. Other non-symmetrical systems have been used.

The four-wire wye system is used when a mixture of single-phase and three-phase loads are to be served, such as mixed lighting and motor loads. An example of application is local distribution in Europe (and elsewhere), where each customer may be only fed from one phase and the neutral (which is common to the three phases). When a group of customers sharing the neutral draw unequal phase currents, the common neutral wire carries the currents resulting from these imbalances. Electrical engineers try to design the three-phase power system for any one location so that the power drawn from each of three phases is the same, as far as possible at that site.[24] Electrical engineers also try to arrange the distribution network so the loads are balanced as much as possible, since the same principles that apply to individual premises also apply to the wide-scale distribution system power. Hence, every effort is made by supply authorities to distribute the power drawn on each of the three phases over a large number of premises so that, on average, as nearly as possible a balanced load is seen at the point of supply.

For domestic use, some countries such as the UK may supply one phase and neutral at a high current (up to 100 A) to one property, while others such as Germany may supply 3 phases and neutral to each customer, but at a lower fuse rating, typically 40–63 A per phase, and "rotated" to avoid the effect that more load tends to be put on the first phase.[citation needed]

Based on wye (Y) and delta (Δ) connection. Generally, there are four different types of three-phase transformer winding connections for transmission and distribution purposes:

- wye (Y) – wye (Y) is used for small current and high voltage,

- Delta (Δ) – Delta (Δ) is used for large currents and low voltages,

- Delta (Δ) – wye (Y) is used for step-up transformers, i.e., at generating stations,

- wye (Y) – Delta (Δ) is used for step-down transformers, i.e., at the end of the transmission.

In North America, a high-leg delta supply is sometimes used where one winding of a delta-connected transformer feeding the load is center-tapped and that center tap is grounded and connected as a neutral as shown in the second diagram. This setup produces three different voltages: If the voltage between the center tap (neutral) and each of the top and bottom taps (phase and anti-phase) is 120 V (100%), the voltage across the phase and anti-phase lines is 240 V (200%), and the neutral to "high leg" voltage is ≈ 208 V (173%).[20]

The reason for providing the delta connected supply is usually to power large motors requiring a rotating field. However, the premises concerned will also require the "normal" North American 120 V supplies, two of which are derived (180 degrees "out of phase") between the "neutral" and either of the center-tapped phase points.

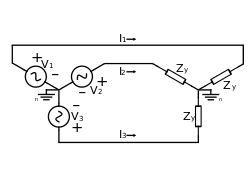

Balanced circuits

[edit]In the perfectly balanced case all three lines share equivalent loads. Examining the circuits, we can derive relationships between line voltage and current, and load voltage and current for wye- and delta-connected loads.

In a balanced system each line will produce equal voltage magnitudes at phase angles equally spaced from each other. With V1 as our reference and V3 lagging V2 lagging V1, using angle notation, and VLN the voltage between the line and the neutral we have:[25]

These voltages feed into either a wye- or delta-connected load.

Wye (or, star; Y)

[edit]

The voltage seen by the load will depend on the load connection; for the wye case, connecting each load to a phase (line-to-neutral) voltages gives[25]

where Ztotal is the sum of line and load impedances (Ztotal = ZLN + ZY), and θ is the phase of the total impedance (Ztotal).

The phase angle difference between voltage and current of each phase is not necessarily 0 and depends on the type of load impedance, Zy. Inductive and capacitive loads will cause current to either lag or lead the voltage. However, the relative phase angle between each pair of lines (1 to 2, 2 to 3, and 3 to 1) will still be −120°.

- Vab = (1∠α − 1∠α + 120°) √3 |V|∠α + 30°,

- Vbc = √3 |V|∠α − 90°,

- Vca = √3 |V|∠α + 150°

By applying Kirchhoff's current law (KCL) to the neutral node, the three phase currents sum to the total current in the neutral line. In the balanced case:

Delta (Δ)

[edit]

In the delta circuit, loads are connected across the lines, and so loads see line-to-line voltages:[25]

(Φv1 is the phase shift for the first voltage, commonly taken to be 0°; in this case, Φv2 = −120° and Φv3 = −240° or 120°.)

Further:

where θ is the phase of delta impedance (ZΔ).

Relative angles are preserved, so I31 lags I23 lags I12 by 120°. Calculating line currents by using KCL at each delta node gives

and similarly for each other line:

where, again, θ is the phase of delta impedance (ZΔ).

- Ia = Iab − Ica = √3 Iab∠−30°,

- Ib = Ibc − Iab,

- Ic = Ica − Ibc.

- S3Φ = 3VphaseI*phase.

Inspection of a phasor diagram, or conversion from phasor notation to complex notation, illuminates how the difference between two line-to-neutral voltages yields a line-to-line voltage that is greater by a factor of √3. As a delta configuration connects a load across phases of a transformer, it delivers the line-to-line voltage difference, which is √3 times greater than the line-to-neutral voltage delivered to a load in the wye configuration. As the power transferred is V2/Z, the impedance in the delta configuration must be 3 times what it would be in a wye configuration for the same power to be transferred.

Single-phase loads

[edit]Except in a high-leg delta system and a corner-grounded delta system, single-phase loads may be connected across any two phases, or a load can be connected from phase to neutral.[27] Distributing single-phase loads among the phases of a three-phase system balances the load and makes most economical use of conductors and transformers.

In a symmetrical three-phase four-wire wye system, the three phase conductors have the same voltage to the system neutral. The voltage between line conductors is √3 times the phase conductor to neutral voltage:[28]

The currents returning from the customers' premises to the supply transformer all share the neutral wire. If the loads are evenly distributed on all three phases, the sum of the returning currents in the neutral wire is approximately zero. Any unbalanced phase loading on the secondary side of the transformer will use the transformer capacity inefficiently.

If the supply neutral is broken, phase-to-neutral voltage is no longer maintained. Phases with higher relative loading will experience reduced voltage, and phases with lower relative loading will experience elevated voltage, up to the phase-to-phase voltage.

A high-leg delta provides phase-to-neutral relationship of VLL = 2 VLN , however, LN load is imposed on one phase.[20] A transformer manufacturer's page suggests that LN loading not exceed 5% of transformer capacity.[29]

Since √3 ≈ 1.73, defining VLN as 100% gives VLL ≈ 100% × 1.73 = 173%. If VLL was set as 100%, then VLN ≈ 57.7%.

Unbalanced loads

[edit]When the currents on the three live wires of a three-phase system are not equal or are not at an exact 120° phase angle, the power loss is greater than for a perfectly balanced system. The method of symmetrical components is used to analyze unbalanced systems.

Non-linear loads

[edit]With linear loads, the neutral only carries the current due to imbalance between the phases. Gas-discharge lamps and devices that utilize rectifier-capacitor front-end such as switch-mode power supplies, computers, office equipment and such produce third-order harmonics that are in-phase on all the supply phases. Consequently, such harmonic currents add in the neutral in a wye system (or in the grounded (zigzag) transformer in a delta system), which can cause the neutral current to exceed the phase current.[27][30]

Three-phase loads

[edit]

An important class of three-phase load is the electric motor. A three-phase induction motor has a simple design, inherently high starting torque and high efficiency. Such motors are applied in industry for many applications. A three-phase motor is more compact and less costly than a single-phase motor of the same voltage class and rating, and single-phase AC motors above 10 hp (7.5 kW) are uncommon. Three-phase motors also vibrate less and hence last longer than single-phase motors of the same power used under the same conditions.[31]

Resistive heating loads such as electric boilers or space heating may be connected to three-phase systems. Electric lighting may also be similarly connected.

Line frequency flicker in light is detrimental to high-speed cameras used in sports event broadcasting for slow-motion replays. It can be reduced by evenly spreading line frequency operated light sources across the three phases so that the illuminated area is lit from all three phases. This technique was applied successfully at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.[32]

Rectifiers may use a three-phase source to produce a six-pulse DC output.[33] The output of such rectifiers is much smoother than rectified single phase and, unlike single-phase, does not drop to zero between pulses. Such rectifiers may be used for battery charging, electrolysis processes such as aluminium production and the electric arc furnace used in steelmaking, and for operation of DC motors. Zigzag transformers may make the equivalent of six-phase full-wave rectification, twelve pulses per cycle, and this method is occasionally employed to reduce the cost of the filtering components, while improving the quality of the resulting DC.

In many European countries electric stoves are usually designed for a three-phase feed with permanent connection. Individual heating units are often connected between phase and neutral to allow for connection to a single-phase circuit if three-phase is not available.[34] Other usual three-phase loads in the domestic field are tankless water heating systems and storage heaters. Homes in Europe have standardized on a nominal 230 V ±10% between any phase and ground. Most groups of houses are fed from a three-phase street transformer so that individual premises with above-average demand can be fed with a second or third phase connection.

Phase converters

[edit]It has been suggested that Rotary phase converter be merged into this section. (Discuss) Proposed since October 2025. |

Phase converters are used when three-phase equipment needs to be operated on a single-phase power source. They are used when three-phase power is not available or cost is not justifiable. Such converters may also allow the frequency to be varied, allowing speed control. Some railway locomotives use a single-phase source to drive three-phase motors fed through an electronic drive.[35]

A rotary phase converter is a three-phase motor with special starting arrangements and power factor correction that produces balanced three-phase voltages. When properly designed, these rotary converters can allow satisfactory operation of a three-phase motor on a single-phase source. In such a device, the energy storage is performed by the inertia (flywheel effect) of the rotating components. An external flywheel is sometimes found on one or both ends of the shaft.

A three-phase generator can be driven by a single-phase motor. This motor-generator combination can provide a frequency changer function as well as phase conversion, but requires two machines with all their expenses and losses. The motor-generator method can also form an uninterruptible power supply when used in conjunction with a large flywheel and a battery-powered DC motor; such a combination will deliver nearly constant power compared to the temporary frequency drop experienced with a standby generator set gives until the standby generator kicks in.

Capacitors and autotransformers can be used to approximate a three-phase system in a static phase converter, but the voltage and phase angle of the additional phase may only be useful for certain loads.

Variable-frequency drives and digital phase converters use power electronic devices to synthesize a balanced three-phase supply from single-phase input power.

Testing

[edit]Verification of the phase sequence in a circuit is of considerable practical importance. Two sources of three-phase power must not be connected in parallel unless they have the same phase sequence, for example, when connecting a generator to an energized distribution network or when connecting two transformers in parallel. Otherwise, the interconnection will behave like a short circuit, and excess current will flow. The direction of rotation of three-phase motors can be reversed by interchanging any two phases; it may be impractical or harmful to test a machine by momentarily energizing the motor to observe its rotation. Phase sequence of two sources can be verified by measuring voltage between pairs of terminals and observing that terminals with very low voltage between them will have the same phase, whereas pairs that show a higher voltage are on different phases.

Where the absolute phase identity is not required, phase rotation test instruments can be used to identify the rotation sequence with one observation. The phase rotation test instrument may contain a miniature three-phase motor, whose direction of rotation can be directly observed through the instrument case. Another pattern uses a pair of lamps and an internal phase-shifting network to display the phase rotation. Another type of instrument can be connected to a de-energized three-phase motor and can detect the small voltages induced by residual magnetism, when the motor shaft is rotated by hand. A lamp or other indicator lights to show the sequence of voltages at the terminals for the given direction of shaft rotation.[36]

Alternatives to three-phase

[edit]- Split-phase electric power

- Used when three-phase power is not available and allows double the normal utilization voltage to be supplied for high-power loads.

- Two-phase electric power

- Uses two AC voltages, with a 90-electrical-degree phase shift between them. Two-phase circuits may be wired with two pairs of conductors, or two wires may be combined, requiring only three wires for the circuit. Currents in the common conductor add to 1.4 times ( ) the current in the individual phases, so the common conductor must be larger. Two-phase and three-phase systems can be interconnected by a Scott-T transformer, invented by Charles F. Scott.[37] Very early AC machines, notably the first generators at Niagara Falls, used a two-phase system, and some remnant two-phase distribution systems still exist, but three-phase systems have displaced the two-phase system for modern installations.

- Monocyclic power

- An asymmetrical modified two-phase power system used by General Electric around 1897, championed by Charles Proteus Steinmetz and Elihu Thomson. This system was devised to avoid patent infringement. In this system, a generator was wound with a full-voltage single-phase winding intended for lighting loads and with a small fraction (usually 1/4 of the line voltage) winding that produced a voltage in quadrature with the main windings. The intention was to use this "power wire" additional winding to provide starting torque for induction motors, with the main winding providing power for lighting loads. After the expiration of the Westinghouse patents on symmetrical two-phase and three-phase power distribution systems, the monocyclic system fell out of use; it was difficult to analyze and did not last long enough for satisfactory energy metering to be developed.

- High-phase-order systems

- Have been built and tested for power transmission. Such transmission lines typically would use six or twelve phases. High-phase-order transmission lines allow transfer of slightly less than proportionately higher power through a given volume without the expense of a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) converter at each end of the line. However, they require correspondingly more pieces of equipment.

- DC

- AC was historically used because it could be easily transformed to higher voltages for long distance transmission. However modern electronics can raise the voltage of DC with high efficiency, and DC lacks skin effect which permits transmission wires to be lighter and cheaper and so high-voltage direct current gives lower losses over long distances.

Color codes

[edit]Conductors of a three-phase system are usually identified by a color code, to facilitate balanced loading and to assure the correct phase rotation for motors. Colors used may adhere to International Standard IEC 60446 (later IEC 60445), older standards or to no standard at all and may vary even within a single installation. For example, in the U.S. and Canada, different color codes are used for grounded (earthed) and ungrounded systems.

| Country | Phases[note 1] | Neutral, N[note 2] |

Protective earth, PE[note 3] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L2 | L3 | ||||||||||

| Australia and New Zealand (AS/NZS 3000:2007 Figure 3.2, or IEC 60446 as approved by AS:3000) | Red, or brown[note 4] | White;[note 4] prev. yellow | Dark blue, or grey[note 4] | Black, or blue[note 4] | Green/yellow-striped (installations prior to 1966: green) | |||||||

| Canada | Mandatory[38] | Red[note 5] | Black | Blue | White, or grey | Green, perhaps yellow-striped, or uninsulated | ||||||

| Isolated systems[39] | Orange | Brown | Yellow | White, or grey | Green perhaps yellow-striped | |||||||

| European CENELEC (European Union and others; since April 2004, IEC 60446, later IEC 60445-2017), United Kingdom (since 31 March 2004), Hong Kong (from July 2007), Singapore (from March 2009), Russia (since 2009; GOST R 50462), Argentina, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, South Korea (from Jan. 2021) | Brown | Black | Grey | Blue | Green/yellow-striped[note 6] | |||||||

| Older European (prior to IEC 60446, varied by country)[note 7] | ||||||||||||

| UK (before April 2006), Hong Kong (before April 2009), South Africa, Malaysia, Singapore (before February 2011) | Red | Yellow | Blue | Black | Green/yellow-striped (before c. 1970: green) | |||||||

| India | Red | Yellow | Blue | Black | Green, perhaps yellow-striped | |||||||

| Chile – NCH 4/2003 | Blue | Black | Red | White | Green, perhaps yellow-striped | |||||||

| Former USSR (Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan; before 2009), People's Republic of China[note 8] (GB 50303-2002 Section 15.2.2) | Yellow | Green | Red | Sky blue | Green/yellow-striped | |||||||

| Norway (before CENELEC adoption) | Black | White/grey | Brown | Blue | Yellow/green-striped; prev. yellow or uninsulated | |||||||

| Norway [note 9] | Black | Brown | Grey | Blue | Green/yellow-striped | |||||||

| United States[note 10] | 120, 208, or 240 V | Black | Red | Blue | White | Bare Conductor (no insulation) | ||||||

| 277 or 480 V | Brown | Orange | Yellow | Gray | Bare Conductor (no insulation) | |||||||

| Alternate Practices (Delta with tapped winding) | Black | Orange

(High-Leg[note 11]) |

Red | White | Green or Yellow/green-striped or no insulation | |||||||

| Blue | ||||||||||||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ In a high-pressure system it is the difficulty of devising an insulation that will not break down which practically limits the voltage. Therefore, in comparing polyphase and single-phase we must take cases that are on a par from this point of view of insulation. It has been common in the case of single-phase (and also in that of continuous currents) to keep one line at the potential of the earth, and to insulate the other sufficiently, having regard to the pressure between the two lines. In this case it is clearly the maximum pressure between the lines that forms what we here are calling the voltage of the system. If, however, both the lines are independently insulated from earth so as to withstand safely the maximum pressure occurring between line and earth, then the lines may have between themselves a voltage equal to double that maximum pressure without fear of a breakdown, provided always the lines, and the respective circuits into which they lead, are so well insulated from one another as to obviate risks in this respect. The question then arises whether, in comparing the advantages of various systems, we shall take as the basis of comparison the pressure between any two lines or the pressure between line and earth. If we take the maximum pressure between any point of the line and earth as the basis of comparison, then there is no saving in copper by the employment of polyphase currents; for each line of any system, carrying a certain current at the maximum allowable pressure above the earth may be considered as dependently transmitting a certain amount of power; and therefore the total power is simply proportional to the number of line-wires, to which the total weight of copper is also proportional. For instance, a 3-phase system joined up in star fashion with the common junction to earth, and having a pressure of 1000 volts between each line and earth (and therefore 1732 volts between line and line), has no advantage so far as the insulation of the line is concerned, over a single-phase system having a pressure of 1000 volts between each line and earth (and therefore 2000 volts between line and line). To transmit equal power, with equal loss in the lines, each of the two wires of the single-phase system must be times as heavy as each of the three wires of the 3-phase system. The two systems will require equal total weights of copper. If, on the other hand, we take the maximum pressure between any two lines as the basis of comparison, we are now equating not the risks of breakdown of the lines, but the risks of breakdown of the apparatus, machines, transformers, &c., in which the goodness of the insulation must be considered equal. And on this basis of comparison there is a decided economy of copper by the employment of 3-phase currents, as can be seen by the following considerations. ... Or, to put it in another way: the single-phase system requires two wires, each of double cross-section, as against the three wires of the 3-phase system. The weight of copper required on the 3-phase system is only three-fourths of that required by any single-phase system.

- ^ Many labelling systems exist for phases, some having additional meaning, such as: H1, H2, H3; A, B, C; R, S, T; U, V, W; R, Y, B.

- ^ Also, grounded conductor.

- ^ Also, earth, or grounding conductor.

- ^ a b c d In Australia and New Zealand, active conductors can be any color except green/yellow, green, yellow, black, or light blue. Yellow is no longer permitted in the 2007 revision of wiring code ASNZS 3000. European color codes are used for all IEC or flex cables such as extension leads, appliance leads etc. and are equally permitted for use in building wiring per AS/NZS 3000:2007.

- ^ In Canada the high leg conductor in a high-leg delta system is always marked red.

- ^ The international standard green-yellow marking of protective-earth conductors was introduced to reduce the risk of confusion by color blind installers. About 7% to 10% of men cannot clearly distinguish between red and green, which is a particular concern in older schemes where red marks a live conductor and green marks protective earth or safety ground.

- ^ In Europe, there still exist many installations with older colors but, since the early 1970s, all new installations use green/yellow earth according to IEC 60446. (E.g. phase/neutral & earth, German: black/grey & red; France: green/red & white; Russia: red/grey & black; Switzerland: red/grey & yellow or yellow & red; Denmark: white/black & red.

- ^ Note that while China officially uses phase 1: yellow, phase 2: green, phase 3: red, neutral: blue, ground: green/yellow, this is not strongly enforced and there is significant local variation.

- ^ According to the guidance in NEK 400-5-51, Section 514.3 NEK:2022 the recommended order in Norway is L1: BLACK, L2: BROWN, and L3: GRAY. However other order may be used. As for when this was implemented it may have been NEK400:2002. PE shall be GREEN/YELLOW according to 514.3.3

- ^ Since 1975, the U.S. National Electric Code has not specified coloring of phase conductors. It is common practice in many regions to identify 120/208 V (wye) conductors as black, red, and blue, and 277/480 V (wye or delta) conductors as brown, orange, yellow. In a 120/240 V delta system with a 208 V high leg, the high leg (typically B phase) is always marked orange, commonly A phase is black and C phase is either red or blue. Local regulations may amend the N.E.C. The U.S. National Electric Code has color requirements for grounded conductors, ground, and grounded-delta three-phase systems which result in one ungrounded leg having a higher voltage potential to ground than the other two ungrounded legs.

- ^ Must be the high leg, if it is present.

References

[edit]- ^ Saleh, S. A.; Rahman, M. A. (25 March 2013). "The analysis and development of controlled 3φ wavelet modulated AC-DC converter". 2012 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES). pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/PEDES.2012.6484282. ISBN 978-1-4673-4508-8. S2CID 32935308.

- ^ William D. Stevenson, Jr. Elements of Power System Analysis Third Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York (1975). ISBN 0-07-061285-4, p. 2

- ^ a b Thompson, Sylvanus P. (1895). "Combinations of polyphase currents". Polyphase electric currents and alternate current motors. E. and F.N. Spon, London. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Brumbach, Michael (2014). Industrial maintenance. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar, Cengage Learning. p. 411. ISBN 9781133131199.

- ^ "AC Power History and Timeline". Edison Tech Center. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Milestones:Rotating Fields and Early Induction Motors, 1885-1888". ETHW. 2022-06-14. Retrieved 2025-01-01.

- ^ US422746A, "Dobrowolsky", issued 1890-03-04

- ^ "US Patent: 422,746 - Electric induction apparatus or transformer". www.datamp.org. Retrieved 2025-01-01.

- ^ US455683A, "Dobeowolsky", issued 1891-07-07

- ^ US456804A, "Dobrowolsky", issued 1891-07-28

- ^ "Wayback Machine". www.mpoweruk.com.

- ^ Gerhard Neidhöfer: Michael von Dolivo-Dobrowolsky und der Drehstrom. Geschichte der Elektrotechnik VDE-Buchreihe, Volume 9, VDE VERLAG, Berlin Offenbach, ISBN 978-3-8007-3115-2.

- ^ Allerhand, Adam (2020). "The Earliest Years of Three-Phase Power—1891–1893 [Scanning Our Past]". Proceedings of the IEEE. 108: 215–227. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2019.2955618.

- ^ Bergström och Nordlund, Lars (2002). Ellära- Kretsteknik och fältteori. Naturaläromedel. p. 283. ISBN 91-7536-330-5.

- ^ Hjulström, Filip (1940). Elektrifieringens utveckling i Sverige, en ekonomisk-geografisk översikt. [Excerpt taken from YMER 1941, häfte 2.Utgiven av Sällskapet för antropologi och geografi: Meddelande från Upsala univeristets geografiska institution, N:o 29, published by Esselte ab, Stockholm 1941 no. 135205]

- ^ von Meier, Alexandra (2006). Electric Power Systems. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-471-17859-0.

We also stated one rationale for this three-phase system; namely, that a three-phase generator experiences a constant torque on its rotor as opposed to the pulsating torque that appears in a single- or two-phase machine, which is obviously preferable from a mechanical engineering standpoint.

- ^ Hawkins Electrical Guide, Theo. Audel and Co., 2nd ed., 1917, vol. 4, Ch. 46: Alternating Currents, p. 1026, fig. 1260.

- ^ Hawkins Electrical Guide, Theo. Audel and Co., 2nd ed., 1917, vol. 4, Ch. 46: Alternating Currents, p. 1026, fig. 1261.

- ^ "A New Design for Automotive Alternators" (PDF). August 30, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-30.

- ^ a b c Fowler, Nick (2011). Electrician's Calculations Manual (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-07-177017-0.

- ^ Gibbs, J. B. (April 27, 1920). "Three-Phase Power from Single-Phase Transformer Connections". Power. 51 (17). McGraw-Hill: 673. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

- ^ H. W. Beaty, D. G. Fink (ed.), Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers. 15th ed., McGraw-Hill, 2007, ISBN 0-07-144146-8, pp. 10–11.

- ^ "Schneider" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ "Saving energy through load balancing and load scheduling" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ^ a b c J. Duncan Glover; Mulukutla S. Sarma; Thomas J. Overbye (April 2011). Power System Analysis & Design. Cengage Learning. pp. 60–68. ISBN 978-1-111-42579-1.

- ^ "What is "Stray Voltage"?" (PDF). Utility Technology Engineers-Consultants (UTEC). August 10, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Lowenstein, Michael. "The 3rd Harmonic Blocking Filter: A Well Established Approach to Harmonic Current Mitigation". IAEI Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ The boy electrician by J. W. Sims M.I.E.E. (p. 98).

- ^ "Federal pacific". Archived from the original on May 30, 2012.

- ^ Enjeti, Prasad. "Harmonics in Low Voltage Three-Phase Four-Wire Electric Distribution Systems and Filtering Solutions" (PDF). Texas A&M University Power Electronics and Power Quality Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ^ Alexander, Charles K.; Sadiku, Matthew N. O. (2007). Fundamentals of Electric Circuits. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 504. ISBN 978-0-07-297718-9.

- ^ Hui, Sun. "Sports Lighting – Design Considerations For The Beijing 2008 Olympic Games" (PDF). GE Lighting. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Pekarek, Steven; Skvarenina, Timothy (November 1998). "ACSL/Graphic Modeller Component Models for Electric Power Education". IEEE Transactions on Education. 41 (4): 348. Bibcode:1998ITEdu..41..348P. doi:10.1109/TE.1998.787374. Archived from the original on June 26, 2003.

- ^ "British and European practices for domestic appliances compared", Electrical Times, volume 148, p. 691, 1965.

- ^ "Speeding-up Conventional Lines and Shinkansen" (PDF). Japan Railway & Transport Review. 58: 58. Oct 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Steve Sentry, "Motor Control Fundamentals", Cengage Learning, 2012, ISBN 1133709176, page 70

- ^ Brittain, J. E. (2007). "Electrical Engineering Hall of Fame: Charles F. Scott". Proceedings of the IEEE. 95 (4): 836–839. Bibcode:2007IEEEP..95..836B. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2006.892488.

- ^ C22.1-15 – Canadian Electrical Code, Part I: Safety Standard for Electrical Installations (23rd ed.). Canadian Standards Association. 2015. Rule 4–038. ISBN 978-1-77139-718-6.

- ^ C22.1-15 – Canadian Electrical Code, Part I: Safety Standard for Electrical Installations (23rd ed.). Canadian Standards Association. 2015. Rule 24–208(c). ISBN 978-1-77139-718-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Neidhofer, Gerhard (2007). "Early Three-Phase Power [History]". IEEE Power and Energy Magazine. 5 (5): 88–100. doi:10.1109/MPE.2007.904752. ISSN 1540-7977.

External links

[edit]Three-phase electric power

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Terminology

Three-phase electric power refers to a polyphase alternating current (AC) electrical system consisting of three separate power-carrying circuits, with voltages and currents staggered symmetrically in time by 120 degrees.[1] This contrasts with direct current (DC) systems, where current flows unidirectionally without phase alternation, making three-phase inherently an AC configuration optimized for efficient power transmission and utilization.[1] A phase in this context denotes one of the three individual sinusoidal voltage or current waveforms (typically labeled a, b, and c) that are equal in magnitude but displaced by 120 electrical degrees.[1] In three-phase systems, phase voltage is the potential difference between one phase conductor and the neutral point, representing the voltage across a single phase winding.[1] By contrast, line voltage (or line-to-line voltage) is the voltage measured between any two phase conductors, which equals √3 times the phase voltage in a balanced wye-connected system and leads the phase voltage by 30 degrees.[1] The neutral is the common connection point in a wye (star) configuration where the three phase conductors meet, serving as a reference for phase voltages and carrying return current in unbalanced conditions.[1] A balanced system occurs when the magnitudes of the three phase voltages or currents are equal and their phases are symmetrically displaced by 120 degrees, resulting in zero current flow through the neutral conductor.[1] Conversely, an unbalanced system features unequal phase magnitudes or loads, leading to neutral current flow and potential voltage variations across phases.[1] Phasor notation provides a vector representation of sinusoidal quantities in the complex plane, where each phase is depicted as a complex number with magnitude equal to the peak (or RMS) value and angle indicating the phase shift, facilitating the analysis of phase relationships without time-domain trigonometry.[7] In three-phase machines like generators and motors, the stator is the stationary outer component housing the windings that produce or receive the rotating magnetic field.[8] The rotor, in turn, is the inner rotating component that interacts with the stator's field to generate torque in motors or electromotive force in generators.[8]Principle of Operation

Three-phase electric power operates on the principle of generating three alternating current (AC) voltages or currents that are sinusoidal waveforms, each displaced by 120 electrical degrees in phase from the others. This configuration arises from the design of three-phase generators, where coils are spatially arranged at 120 degrees around the stator, producing time-displaced outputs as a rotor's magnetic field sweeps past them. The voltages can be expressed as , , and , where is the RMS voltage and is the angular frequency.[9][10] To analyze the relationships between these voltages and corresponding currents, phasors are employed as rotating vectors in the complex plane, representing the magnitude and phase angle of each sinusoidal quantity using root-mean-square (RMS) values. For a balanced system, the phase voltages are depicted as phasors , , and , where here denotes the RMS phase voltage. Currents follow similarly, with their phasors determined by the load impedance, enabling straightforward vector addition and circuit analysis without time-domain integration.[9][10] In a wye-connected system, the line voltage (between two lines) exceeds the phase voltage (line-to-neutral) due to the vector sum of two phase voltages. Consider the line voltage between phases A and B: it is the phasor difference . Substituting the phasors yields . Resolving into rectangular components: The magnitude is then , so , with a 30-degree phase lead. This relationship holds symmetrically for other line voltages in a balanced wye system.[9] The total instantaneous power in a balanced three-phase system remains constant, avoiding the pulsations inherent in single-phase power. The instantaneous power of each phase is , and similarly for phases B and C, where is the RMS current and is the phase angle. Expanding using trigonometric identities, the sum includes terms that cancel due to the 120-degree shifts, resulting in , a DC value independent of time. This constancy arises from the vector symmetry, ensuring smooth power delivery.[9][10] In three-phase machines, the phase-displaced currents in the stator windings produce a rotating magnetic field, fundamental to the operation of motors and generators. The field results from the superposition of three pulsating fields, each along a spatial axis 120 degrees apart, creating a resultant vector of constant magnitude that rotates at synchronous speed , where is the supply frequency and is the number of poles. This rotation induces voltages in generators or torques rotors in motors via electromagnetic interaction.[9][11]Phase Sequence

In a three-phase electric power system, the phase sequence defines the temporal order in which the voltages of the three phases reach their positive peak values. The positive phase sequence, commonly denoted as ABC, occurs when phase A reaches its peak first, followed by phase B after a 120° lag, and then phase C after another 120° lag, creating an anticlockwise rotation in the phasor representation.[12] This sequence is characterized by the angular displacement between consecutive phases, as expressed in the phasor equations where the voltage phasors are , , and , with the phasor diagram showing vectors spaced 120° apart in the ABC order to illustrate the forward rotational sense.[13] The negative phase sequence, denoted as ACB, reverses this order, with phase A peaking first, followed by phase C after a 120° lag, and phase B after another 120° lag, resulting in a clockwise rotation in the phasor diagram where the phasors are , , and .[12] Sequence reversal is typically achieved by interchanging the connections of any two phases, which inverts the rotational direction without altering the magnitude or frequency of the voltages.[14] The phase sequence significantly impacts the operation of rotating machinery, such as three-phase induction motors, where the positive ABC sequence generates a forward rotating magnetic field that produces torque in the counterclockwise direction (when viewed from the drive end), driving the motor in its intended forward rotation.[15] Conversely, a negative ACB sequence creates a reverse rotating magnetic field, producing torque in the clockwise direction and causing the motor to rotate oppositely, which can lead to incorrect operation or mechanical stress if not corrected.[12] Phase sequence can be detected using dedicated phase sequence indicators, which are small three-phase motors equipped with a visible rotor or pointer; the direction of rotor rotation—clockwise for ABC or counterclockwise for ACB—directly reveals the sequence.[15] Another method involves connecting voltmeters across components in an unbalanced RL or RC circuit, where the relative voltage magnitudes (e.g., higher voltage across the resistor in a positive sequence RL setup) differ based on the sequence, allowing determination through measurement.[15] In industrial applications, the positive ABC sequence is the preferred standard in North America and Europe to ensure consistent motor rotation and system interoperability, with phase labeling often following A-B-C or equivalent color codes like red-yellow-blue.[14]Historical Development

Origins and Invention

In the 1880s, early alternating current (AC) systems were predominantly single-phase and optimized for lighting, yet they revealed critical limitations for motor applications and electric traction, as single-phase currents generated only pulsating magnetic fields that resulted in inefficient, vibration-prone operation unsuitable for consistent torque in industrial or transport uses.[16] These shortcomings spurred innovations in multiphase systems, particularly through the development of rotating magnetic fields to enable smoother and more efficient motor performance. Italian electrical engineer Galileo Ferraris independently conceived this principle in 1885 while experimenting at the Polytechnic University of Turin, constructing a prototype induction motor with two perpendicular sets of coils energized by phase-shifted AC currents to produce a continuously rotating magnetic field. Ferraris detailed his findings in a paper presented to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin on March 18, 1888, emphasizing the potential for polyphase configurations, though he chose not to patent the invention.[17] Key developments in three-phase systems emerged concurrently. In 1887, German engineer Friedrich August Haselwander proposed the first three-phase AC system and built a three-phase synchronous generator. Swedish inventor Jonas Wenström patented a complete three-phase generation and transmission system in 1889. Russian engineer Michael Dolivo-Dobrowolsky developed the first practical three-phase cage induction motor in 1889, as well as three-phase generators and transformers, enabling the successful 1891 Lauffen-to-Frankfurt power transmission — the first long-distance three-phase AC demonstration.[4][18][19] Concurrently, Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla pursued similar concepts in the United States, filing a series of patents in late 1887 for polyphase AC systems that included generators, transmission lines, and motors capable of harnessing rotating fields for practical power distribution. These included designs for three-phase configurations. A cornerstone of these was U.S. Patent 381,968, titled "Electro-Magnetic Motor," granted on May 1, 1888, which outlined a multiphase motor design using independent magnetizing coils to create a rotating field from alternating currents, addressing the inefficiencies of single-phase motors.[20] Tesla publicly demonstrated his polyphase (two-phase) motor and generator prototypes on May 16, 1888, during a lecture titled "A New System of Alternating Current Motors and Transformers" to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in New York, marking an early operational exhibit of polyphase technology and highlighting its superiority for long-distance transmission and mechanical drive applications.[16]Widespread Adoption

The first commercial demonstration of three-phase hydroelectric power occurred in 1891 at the Lauffen am Neckar plant in Germany, where electricity was generated and transmitted over 175 kilometers to Frankfurt am Main for the International Electrotechnical Exhibition.[21][22] This system delivered approximately 300 horsepower at 15,000 volts with 75% efficiency, marking the initial long-distance application of three-phase alternating current and showcasing its viability for utility-scale distribution.[22] In the United States during the 1890s, Westinghouse Electric Company adopted Nikola Tesla's polyphase alternating current system, including three-phase configurations, as part of the "War of Currents" against Thomas Edison's direct current networks.[23] Westinghouse's licensing of Tesla's patents in 1888 enabled the development of efficient polyphase generators and motors, tipping the balance toward AC adoption for its superior transmission capabilities over long distances. Key milestones followed, including the powering of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago with Westinghouse's two-phase polyphase AC system, which illuminated the fair using twelve 1,000-horsepower polyphase generators and consumed three times the electricity of the entire city. This success paved the way for the 1895 Adams Hydroelectric Generating Plant at Niagara Falls, the world's largest at the time, which generated 11,000 volts of two-phase polyphase AC at 25 cycles per second to supply power over 20 miles.[24] Standardization efforts in the early 1900s solidified three-phase systems globally. The American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE), predecessor to the IEEE, established its first standardization committee in 1898, focusing on electrical apparatus including voltages and frequencies. Westinghouse's selection of 60 Hz in 1891 contributed to its emergence as the dominant U.S. frequency in the early 1900s.[25][26] Internationally, the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), founded in 1906, developed unified terminology, measurements, and specifications for three-phase equipment to facilitate cross-border interoperability.[27] The global spread of three-phase power in the early 20th century diverged by region: Europe prioritized traction systems for railways, with Italy adopting three-phase AC for electric locomotives as early as the 1900s due to its efficiency in variable-speed applications.[28] In contrast, the United States emphasized industrial applications, where three-phase motors powered factories and heavy machinery, with networks expanding significantly by the 1910s.[29] This focus reflected Europe's denser rail infrastructure versus America's burgeoning manufacturing sector.Benefits and Limitations

Advantages

One key advantage of three-phase electric power is its ability to deliver constant power to loads, resulting in smooth operation without the torque pulsations experienced in single-phase motors.[30] In three-phase induction motors, the rotating magnetic field produced by the offset phases ensures a continuous torque output, eliminating the need for auxiliary starting mechanisms and reducing mechanical stress and noise.[30] This constant power delivery stems from the balanced nature of the three-phase system, where the instantaneous power remains uniform across the cycle. Three-phase systems also offer higher transmission efficiency, enabling approximately 1.73 times more power to be transmitted using conductors of the same size compared to single-phase systems, due to the factor in the power equation . This efficiency arises because the line current in a three-phase system is lower for the same total power and voltage, reducing resistive losses in the conductors.[31] Consequently, equipment design is simplified, as three-phase motors are inherently self-starting without requiring capacitors or additional windings, unlike single-phase motors that need such components for phase shifting.[32] Furthermore, fewer wires are needed overall to deliver equivalent power, streamlining installation and maintenance.[30] Economically, three-phase power reduces material costs in transmission lines by requiring about 25% less copper than single-phase systems for the same power capacity and distance.[33] This savings comes from the optimized current distribution across three phases, allowing smaller conductor cross-sections while maintaining performance.[33] In generators, three-phase configurations produce a smoother output voltage profile due to the interleaved phases, minimizing fluctuations and improving overall system stability compared to single-phase alternatives.[34]Disadvantages

Three-phase electric power systems exhibit greater complexity compared to single-phase systems, primarily due to the need for three conductors instead of two, which increases material requirements and installation challenges. This additional wiring elevates deployment costs, with estimates for extending three-phase service ranging from $40,000 to $80,000 per mile (as of 2023) in rural or remote areas where infrastructure is absent.[35] Single-phase alternatives are often favored for their simpler and lower-cost installation in such scenarios.[36] The initial capital outlay for three-phase systems is also higher, stemming from the necessity for specialized equipment such as multi-winding transformers and advanced protective relays designed to handle balanced and unbalanced conditions across phases. These components, including larger panels and isolation transformers, contribute to upfront expenses that exceed those of single-phase setups for equivalent power capacities in industrial applications.[37][38] In unbalanced loading conditions, where single-phase loads are unevenly distributed across the three phases, significant neutral currents can arise, particularly from triplen harmonics generated by nonlinear loads. These currents, which do not cancel in the neutral conductor, can exceed the rated capacity, leading to overheating, increased losses, and potential damage or fire hazards in the neutral wiring.[39] Safety risks are amplified in three-phase systems due to the higher line-to-line voltages, such as 208 V compared to the 120 V phase-to-neutral in standard U.S. wye configurations, which heighten the potential for electric shock and arc flash incidents during faults or maintenance. Low-voltage three-phase setups like 208Y/120 V still pose arc flash hazards under bolted fault conditions with available short-circuit currents above certain thresholds, necessitating enhanced protective measures beyond those for single-phase 120 V systems.[40] Maintenance of three-phase systems presents additional difficulties, as fault diagnosis requires monitoring and testing across multiple phases, complicating troubleshooting compared to the straightforward two-wire approach in single-phase circuits. This multi-phase nature often demands specialized tools and expertise to isolate issues like phase imbalances or inter-phase faults, resulting in higher ongoing maintenance costs.[36][41]Generation and Transmission

Power Generation

Three-phase electric power is primarily generated using synchronous generators, where three-phase windings are placed on the stator and excited by a rotating DC magnetic field produced by the rotor. The rotor, typically featuring salient poles or a cylindrical structure, is supplied with direct current through slip rings and brushes or via a brushless exciter system, creating a constant magnetic field that rotates synchronously with the prime mover, such as a steam turbine or hydroelectric turbine. As the rotor turns, it induces electromotive forces (EMFs) in the stator windings, which are spatially displaced by 120 electrical degrees, resulting in three balanced sinusoidal voltages that form the three-phase output.[42] The magnitude of the induced EMF per phase in a synchronous generator is given by the equation , where is the frequency, is the number of turns per phase, is the flux per pole, and is the winding factor accounting for distribution and pitch effects. For three-phase operation, this equation ensures balanced EMFs with a 120-degree phase shift, producing a rotating magnetic field that maintains constant power delivery without the pulsations seen in single-phase systems. Modern synchronous generators in power plants typically produce three-phase output at voltages ranging from 11 kV to 25 kV, which is then stepped up for transmission.[43] The full-load line current in a three-phase system is calculated using the formula , where is the apparent power in kVA and is the line-to-line voltage in volts. As an illustrative example, a 1000 kVA generator operating at 400 V—a common low-voltage three-phase level in many regions—has a full-load line current of approximately 1443 A (often rounded to 1440 A in specifications).[44] The frequency of the generated three-phase power is standardized at 50 Hz in Europe and much of Asia, and 60 Hz in the Americas, directly tied to the synchronous speed of the turbine-driven rotor via the relation , where is the number of poles and is the rotor speed in RPM. This standardization ensures compatibility across interconnected grids. In renewable energy integration, wind turbines often employ three-phase induction generators, such as doubly-fed induction generators (DFIGs), which operate asynchronously but produce three-phase AC output synchronized to the grid frequency through power electronics. Similarly, solar photovoltaic systems use three-phase inverters to convert DC power to grid-compatible three-phase AC, employing phase-locked loops (PLLs) for precise synchronization with the utility grid's voltage, frequency, and phase.[45][46]Distribution Systems

Three-phase electric power distribution begins with high-voltage transmission lines that carry electricity from generation plants over long distances to substations. These lines typically operate at voltages ranging from 110 kV to 765 kV and consist of three overhead conductors arranged in a delta configuration, which is ungrounded to minimize grounding-related issues and reduce the need for a neutral conductor.[47][48] At substations, transformers step down the high voltage to medium levels suitable for local distribution, generally between 2.4 kV and 33 kV. This reduction allows for safer and more efficient delivery to end-users while maintaining compatibility with three-phase systems.[49] In urban areas, distribution infrastructure often employs underground cables to enhance reliability, aesthetics, and protection from environmental factors, despite higher installation costs. Conversely, rural distribution predominantly uses pole-mounted overhead lines, which are more economical for sparsely populated regions with longer spans between loads.[50] Grounding practices in distribution systems favor a solidly grounded wye configuration, where the neutral is directly connected to ground, facilitating rapid detection and clearing of ground faults through high fault currents that protective relays can sense effectively.[51] Transmission and distribution losses primarily arise from resistive heating in conductors, quantified as where is current and is resistance; employing higher voltages reduces current for a given power level, thereby significantly lowering these losses across three-phase lines.[52]Transformer Configurations

Three-phase transformers are commonly configured using wye (star) or delta connections on the primary and secondary windings to match system requirements for voltage transformation, grounding, and load balancing.[53] The four primary configurations—wye-wye, delta-delta, delta-wye, and wye-delta—each exhibit distinct electrical characteristics, including phase shifts and current flow paths.[54] These setups are typically implemented as a single three-phase unit or a bank of three single-phase transformers.[53] In the wye-wye (Y-Y) configuration, both primary and secondary windings connect at a common neutral point, forming a star shape on each side. The diagram consists of three windings per side, with one end of each tied to the neutral and the other ends to the line terminals. Line voltage equals times phase voltage on both sides, and phase currents equal line currents. This setup allows for a grounded neutral on both sides, enabling single-phase loads, but it can propagate zero-sequence currents and third-harmonic voltages unless mitigated by a tertiary delta winding.[53] The delta-delta (Δ-Δ) configuration features closed triangular windings on both primary and secondary sides, with no neutral available. The diagram shows three windings connected end-to-end in a loop on each side, with line terminals at the junctions. Line and phase voltages are equal on both sides, with no phase shift between primary and secondary. It supports three-phase loads effectively and can operate in open-delta mode with two transformers if one fails, though unbalanced loads may induce circulating currents. Third-harmonic currents circulate within the delta loops without affecting the external system.[53] A delta-wye (Δ-Y) transformer has delta-connected primary windings and wye-connected secondary windings, often with a grounded neutral on the secondary. The primary diagram is a closed triangle, while the secondary forms a star with neutral access. This arrangement introduces a 30° phase shift (lagging) and provides line-to-neutral voltages on the secondary for single-phase loads. It is widely used for stepping down transmission voltages to distribution levels due to its ability to balance loads and isolate faults. Zero-sequence currents are trapped in the primary delta, preventing them from appearing on the secondary.[54][53] Conversely, the wye-delta (Y-Δ) configuration reverses the windings, with wye on the primary (often grounded) and delta on the secondary. The primary diagram is a star, and the secondary a closed triangle. It also produces a 30° phase shift (leading) and is suited for step-up applications, such as connecting generators to transmission lines, by providing a neutral on the high-voltage primary side. The secondary delta confines third harmonics internally.[54][53] Voltage relationships in these configurations depend on the winding type and turns ratio. In a delta-wye transformer, the secondary line voltage is given by , where the turns ratio is the ratio of primary to secondary turns per phase, accounting for the factor between line and phase voltages on the wye side.[54][55] For wye-wye and delta-delta, the line voltage ratio directly matches the turns ratio, while wye-delta follows a similar adjustment but inverted. Phase sequence determines the direction of these phase shifts, ensuring compatibility in paralleled systems.[53] Zero-sequence currents, including third harmonics from non-linear loads, are handled differently based on the configuration. Delta windings block zero-sequence paths to the external circuit by allowing these currents to circulate internally, reducing distortion on the line. Wye windings with a neutral permit zero-sequence flow, which can lead to neutral currents but enables grounding for fault detection.[56][53] The Scott-T transformer represents a specialized configuration using two single-phase transformers in a T-shaped connection to convert between three-phase and two-phase power, providing balanced voltages without a neutral on the two-phase side. It finds unique application in legacy systems or specific industrial drives requiring two-phase supply from three-phase grids.[57] Three-phase transformers are rated for cooling to manage heat from core and winding losses, with oil-immersed and dry-type designs being predominant. Oil-immersed units use insulating oil for both cooling and insulation, often with natural (ONAN) or forced (ONAF) air circulation, offering high efficiency and suitability for outdoor, high-power installations up to hundreds of MVA. Dry-type transformers rely on air cooling, either natural (AN) or forced (AF), providing fire safety and environmental advantages for indoor, medium-power applications like buildings, though they are bulkier and less efficient at high ratings.[58]Circuit Configurations

Three-Wire and Four-Wire Systems

Three-wire three-phase systems, typically configured in a delta or ungrounded wye arrangement, consist of three phase conductors without a neutral wire and are primarily employed for serving balanced industrial loads such as large motors and heavy machinery.[47] In these setups, power is delivered solely through the three phase lines, providing line-to-line voltages like 240 V in common U.S. applications, which suits environments where loads are symmetrically distributed across phases to avoid current imbalances.[59] The absence of a neutral simplifies installation and reduces material costs but limits the system's ability to accommodate unbalanced or single-phase loads effectively, as any deviation requires careful load balancing to prevent overheating or inefficiency.[54] In contrast, four-wire three-phase systems typically utilize a wye configuration with three phase conductors and a dedicated neutral wire, though delta configurations with a neutral are also used, enabling the derivation of single-phase voltages alongside three-phase power and making them prevalent in commercial buildings for mixed load requirements.[60] In wye arrangements, this delivers line-to-line voltages of 208 V and line-to-neutral voltages of 120 V in standard U.S. installations, allowing single-phase appliances like lighting and outlets to connect directly to a phase and neutral without additional transformers.[60] A common four-wire delta configuration, known as high-leg delta, provides 240 V line-to-line voltages, with 120 V line-to-neutral from two phases and 208 V from the high leg to neutral; it is often used in older U.S. commercial and light industrial settings to supply both 120 V single-phase and 240 V three-phase power.[61] The neutral conductor serves as a current return path for unbalanced loads, enhancing flexibility for diverse applications in offices, retail spaces, and light commercial facilities.[62] A key safety feature of four-wire systems is the grounding of the neutral conductor at the service entrance, which establishes a low-impedance reference for line-to-neutral voltages and facilitates the detection and clearing of ground faults by providing a path for fault currents back to the source.[63] This grounding practice reduces shock hazards and improves system stability compared to ungrounded three-wire configurations, where fault detection relies on other methods like ground lamps or relays. In wye four-wire systems, the neutral enables more effective support of unbalanced single-phase loads by allowing distribution across all three phases, with the neutral carrying the resulting imbalance current and preventing severe line current imbalances that could occur in three-wire systems.[47]Balanced Wye Connection

In a balanced wye (star) connection, three phase windings or loads are connected at a common neutral point, forming a four-wire system when the neutral is included, with the other ends connected to the three line conductors. The neutral point maintains zero potential relative to ground in balanced conditions because the vector sum of the three balanced phase currents is zero, resulting in no neutral current flow.[10][64] In this configuration, the line current equals the phase current, as each line conductor carries the current of its respective phase without sharing.[64][10] The phase voltages are equal in magnitude and separated by 120° in the phasor diagram, with the line-to-line voltage being times the phase voltage due to the geometric relationship between the vectors. For example, if the phase voltage is represented as a phasor at 0°, the adjacent phase is at -120°, and the third at +120°; the line voltage between the first and second phases is then at a 30° angle.[10][64] The total three-phase power in a balanced wye connection is given by the equation where is the line-to-line voltage, is the line current (equal to phase current), and is the phase angle between voltage and current; this derives from the per-phase power multiplied by three, accounting for the voltage ratio.[10][64] The apparent power in volt-amperes (or kVA when scaled) is given by which allows calculation of the line current for a known apparent power and line voltage via . For instance, in a balanced system rated at 1000 kVA apparent power and operating at a line-to-line voltage of 400 V (a common low-voltage three-phase level in many regions), the full-load line current is approximately 1443 A.[65] This configuration provides constant power delivery without pulsations, as the instantaneous power across phases sums uniformly.[10] Balanced wye connections are widely used in residential and commercial power distribution systems, particularly with wye-connected transformers, as they support both single-phase and three-phase loads efficiently from the same network.[66] The neutral conductor in such systems facilitates the distribution of mixed loads while maintaining balance under ideal conditions. In balanced operation, the neutral path, though carrying zero current, inherently supports zero-sequence components like triplen harmonics if introduced, though they cancel out symmetrically.[10]Balanced Delta Connection

In a balanced delta connection, the three phase windings are interconnected in a closed triangular loop, eliminating the need for a neutral conductor. This configuration ensures that the line voltage equals the phase voltage (), while the line current magnitude is times the phase current magnitude (), with the line current lagging the phase current by 30 degrees.[67][68] Ungrounded delta systems enhance fault tolerance through circulating currents; during a single ground fault on one phase, the fault current flows through the capacitances to ground and circulates within the delta loop via the other two phases, allowing continued operation without immediate tripping.[69][70] The total three-phase power for a balanced delta-connected load is calculated as , identical in form to the wye connection formula but leveraging the equality of line and phase voltages.[67] Delta connections find widespread application in high-power industrial motors, where their ability to handle elevated currents and provide torque without a neutral supports robust performance, and in transmission lines to simplify infrastructure by avoiding neutral conductors.[68][71] In practice, three-phase induction motors are often connected in delta configuration. No neutral conductor is required, as the windings form a closed triangular loop without a star point, and the motor connects directly to the three line conductors L1, L2, and L3. A standard wiring example for motors with terminals U1, U2 (phase U), V1, V2 (phase V), and W1, W2 (phase W) involves bridging U1 to V2, V1 to W2, and W1 to U2 to form the delta. The line conductors are then connected to the bridged junctions: L1 to U1/V2, L2 to V1/W2, and L3 to W1/U2 (variations in terminal bridging direction exist but are functionally equivalent up to phase rotation). Each winding receives the full line-to-line voltage (e.g., 400 V in Europe), and the motor operates symmetrically without a neutral conductor. A key advantage of the delta's closed-loop structure is the trapping of third-harmonic currents, which circulate internally within the windings rather than appearing in the line currents, thereby mitigating harmonic distortion in the power supply.[72]Load Connections

Single-Phase Loads