Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Artist's book

View on Wikipedia

Artists' books (or book art or book objects) are works of art that engage with and transform the form of a book. Some are mass-produced with multiple editions, and some in small editions, while others are produced as one-of-a-kind objects.[1]

There is no single definition of an artist's book, and formulating a definition is cumbersome and subject to debate.[2] Importantly, the creation of artists' books incorporates a variety of formats and genres.[3] They have a complex history, with a particular focus and growth in contemporary artist movements.[4] They also have recently grown in popularity, especially in art institutions, and have become popular in art library reference workshops.[4] The exact definition and usage of artists' books has become more fluid and porous alongside the growth in popularity of artists' books.[5]

Overview

[edit]Artists' books have employed a wide range of forms, including the traditional Codex form as well as less common forms like scrolls, fold-outs, concertinas or loose items contained in a box. Artists have been active in printing and book production for centuries, but the artist's book is primarily a late 20th-century form. Book forms were also created within earlier movements, such as Dada, Constructivism, Futurism, and Fluxus.[6]

One suggested definition of an artist's book is as follows:

Artists' books are books or book-like objects over the final appearance of which an artist has had a high degree of control; where the book is intended as a work of art in itself.

— Stephen Bury[7]

Generally, an artist's book is interactive, portable, movable, and easily shared. Some artists' books challenge the conventional book format and become sculptural objects. Artists' books also may be created in order to make art accessible to people outside of the formal contexts of galleries or museums.[3][4]

Artists' books can be made from a variety of materials, including found objects.[8] The VCU Book Arts LibGuide writes that the following methods and practices are common (but certainly not the only methods) in artists' book production:

- hand binding

- letterpress printing

- digital printing

- photography

- printmaking

- calligraphy and hand lettering

- painting and drawing

- graphic designing

- paper engineering

- automated/machine production[3]

Early history

[edit]

Origins of the form: William Blake

[edit]Whilst artists have been involved in the production of books in Europe since the early medieval period (such as the Book of Kells and the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry), most writers on the subject cite the English visionary artist and poet William Blake (1757–1827) as the earliest direct antecedent.[6][10]

Books such as Songs of Innocence and of Experience were written, illustrated, printed, coloured and bound by Blake and his wife Catherine, and the merging of handwritten texts and images created intensely vivid, original works without any obvious precedents. These works would set the tone for later artists' books, connecting self-publishing and self-distribution with the integration of text, image and form.[citation needed] All of these factors have remained key concepts in artists' books up to the present day.

Avant-garde production 1909–1937

[edit]

As Europe plunged headlong towards World War I, various groups of avant-garde artists across the continent started to focus on pamphlets, posters, manifestos, and books. This was partially as a way to gain publicity within an increasingly print-dominated world, but also as a strategy to bypass traditional gallery systems. This allowed for the dissemination of new ideas and the creation of affordable work that might (theoretically) be seen by people who would not otherwise enter art galleries.[11]

This move toward radicalism was exemplified by the Italian Futurists, and by Filippo Marinetti (1876–1944) in particular. The publication of the "Futurist Manifesto", 1909, on the front cover of the French daily newspaper Le Figaro was an audacious coup de théâtre that resulted in international notoriety.[12] Marinetti used the ensuing fame to tour Europe, kickstarting movements across the continent that all veered towards book-making and pamphleteering.

In London, for instance, Marinetti's visit directly precipitated Wyndham Lewis' founding of the Vorticist movement, whose literary magazine BLAST is an early example of a modernist periodical, while David Bomberg's book Russian Ballet (1919), with its interspersing of a single carefully spaced text with abstract colour lithographs, is a landmark in the history of English language artists' books.[citation needed]

Russian Futurism, 1910–1917

[edit]

Regarding the creation of artists' books, the most influential offshoot of futurist principles occurred in Russia. Centered in Moscow, around the Gileia Group of Transrational (zaum) poets David and Nikolai Burliuk, Elena Guro, Vasili Kamenski and Velimir Khlebnikov, the Russian futurists created a sustained series of artists' books that challenged every assumption of orthodox book production. Whilst some of the books created by this group would be relatively straightforward typeset editions of poetry, many others played with form, structure, materials, and content that still seems contemporary.

Key works such as Worldbackwards (1912), by Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh, Natalia Goncharova, Larionov Rogovin and Tatlin, Transrational Boog (1915) by Aliagrov and Kruchenykh & Olga Rozanova, and Universal War (1916) by Kruchenykh used hand-written text, integrated with expressive lithographs and collage elements, creating small editions with dramatic differences between individual copies. Other titles experimented with materials such as wallpaper, printing methods including carbon copying and hectographs, and binding methods including the random sequencing of pages, ensuring no two books would have the same contextual meaning.[13] Marinetti visited in 1914, proselytizing on behalf of Futurist principles of speed, danger, and cacophony.[14][15]

Russian futurism gradually evolved into Constructivism after the Russian Revolution, centered on the key figures of Malevich and Tatlin. Attempting to create a new proletarian art for a new communist epoch, constructivist books would also have a huge impact on other European avant-gardes, with design and text-based works such as El Lissitzky's For The Voice (1922) having a direct impact on groups inspired by or directly linked to communism. Dada in Zurich and Berlin, the Bauhaus in Weimar, and De Stijl in the Netherlands all printed numerous books, periodicals, and theoretical tracts within the newly emerging International Modernist style. Artists' books from this era include Kurt Schwitters and Kate Steinitz's book The Scarecrow (1925), and Theo van Doesburg's periodical De Stijl.

Dada and Surrealism

[edit]Dada was initially started at the Cabaret Voltaire, by a group of exiled artists in neutral Switzerland during World War I. Originally influenced by the sound poetry of Wassily Kandinsky, and the Blaue Reiter Almanac that Kandinsky had edited with Marc, artists' books, periodicals, manifestoes and absurdist theatre were central to each of Dada's main incarnations. Berlin Dada in particular, started by Richard Huelsenbeck after leaving Zurich in 1917, would publish a number of incendiary artists' books, such as George Grosz's The Face Of The Dominant Class (1921), a series of politically motivated satirical lithographs about the German bourgeoisie.

Whilst concerned mainly with poetry and theory, Surrealism created a number of works that continued in the French tradition of the Livre d'Artiste, whilst simultaneously subverting it. Max Ernst's Une Semaine de Bonté (1934), collaging found images from Victorian books, is a famous example, as is Marcel Duchamp's cover for Le Surréalisme' (1947) featuring a tactile three-dimensional pink breast made of rubber.[16]

One important Russian writer/artist who created artist books was Alexei Remizov.[17] Drawing on medieval Russian literature, he creatively combined dreams, reality, and pure whimsy in his artist books.

After World War II; post-modernism and pop art

[edit]Regrouping the avant-garde

[edit]After World War II, many artists in Europe attempted to rebuild links beyond nationalist boundaries, and used the artist's book as a way of experimenting with form, disseminating ideas and forging links with like-minded groups in other countries.

In the fifties artists in Europe developed an interest in the book, under the influence of modernist theory and in the attempt to rebuild positions destroyed by the war.

— Dieter Schwarz[18]

After the war, a number of leading artists and poets started to explore the functions and forms of the book 'in a serious way'.[19] Concrete poets in Brazil such as Augusto and Haroldo de Campos, Cobra artists in the Netherlands and Denmark and the French Lettrists all began to systematically deconstruct the book. A fine example of the latter is Isidore Isou's Le Grand Désordre, (1960), a work that challenges the viewer to reassemble the contents of an envelope back into a semblance of narrative. Two other examples of poet-artists whose work provided models for artists' books include Marcel Broodthaers and Ian Hamilton Finlay.[20]

Yves Klein in France was similarly challenging Modernist integrity with a series of works such as Yves: Peintures (1954) and Dimanche (1960) which turned on issues of identity and duplicity.[21] Other examples from this era include Guy Debord and Asger Jorn's two collaborations, Fin de Copenhague (1957) and Mémoires' (1959), two works of Psychogeography created from found magazines of Copenhagen and Paris respectively, collaged and then printed over in unrelated colours.[22]

Dieter Roth and Ed Ruscha

[edit]Often credited with defining the modern artist's book, Dieter Roth (1930–98) produced a series of works which systematically deconstructed the form of the book throughout the fifties and sixties.[23] These disrupted the codex's authority by creating books with holes in (e.g. Picture Book, 1957), allowing the viewer to see more than one page at the same time. Roth was also the first artist to re-use found books: comic books, printer's end papers and newspapers (such as Daily Mirror, 1961 and AC, 1964).[24][25] Although originally produced in Iceland in extremely small editions, Roth's books would be produced in increasingly large runs, through numerous publishers in Europe and North America, and would ultimately be reprinted together by the German publisher Hansjörg Mayer in the 1970s, making them more widely available in the last half-century than the work of any other comparable artist.

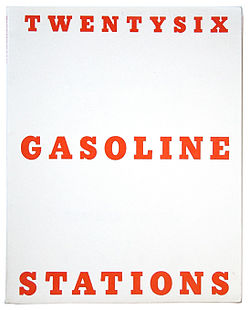

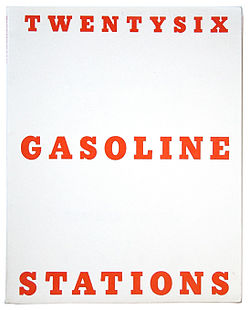

Almost contemporaneously in the United States, Ed Ruscha (1937–present) printed his first book, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, in 1963 in an edition of 400, but had printed almost 4000 copies by the end of the decade.[26] The book is directly related to American photographic travelogues, such as Robert Frank's The Americans' (1965), but deals with a banal journey on route 66 between Ruscha's home in Los Angeles and his parents' in Oklahoma.[27] Like Roth, Ruscha created a series of homogenous books throughout the sixties, including Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966, and Royal Road Test, 1967.

A Swiss artist worth mentioning is Warja Honegger-Lavater, who created artists' books contemporaneously with Dieter Roth and Ed Ruscha.

Fluxus and the Multiple

[edit]Growing out of John Cage's Experimental Composition classes from 1957 to 1959 at the New School for Social Research, Fluxus was a loose collective of artists from North America and Europe that centered on George Maciunas (1931–78), who was born in Lithuania. Maciunas set up the AG Gallery in New York, 1961, with the intention of putting on events and selling books and multiples by artists he liked. The gallery closed within a year, apparently having failed to sell a single item.[28] The collective survived, and featured an ever-changing roster of like-minded artists including George Brecht, Joseph Beuys, Davi Det Hompson, Daniel Spoerri, Yoko Ono, Emmett Williams and Nam June Paik.[29][30]

Artists' books (such as An Anthology of Chance Operations) and multiples[31] (as well as happenings), were central to Fluxus' ethos disdaining galleries and institutions, replacing them with "art in the community", and the definition of what was and wasn't a book became increasingly elastic throughout the decade as the two forms collided. Many of the Fluxus editions share characteristics with both; George Brecht's Water Yam (1963), for instance, involves a series of scores collected in a box, whilst similar scores are collected together in a bound book in Yoko Ono's Grapefruit (1964). Another famous example is Literature Sausage by Dieter Roth, one of many artists to be affiliated to Fluxus at one or other point in its history; each one was made from a pulped book mixed with onions and spices and stuffed into sausage skin. Literally a book, but utterly unreadable. Litsa Spathi and Ruud Jansen of the Fluxus Heidelberg Center in the Netherlands have an online archive of fluxus publications and fluxus webslinks.[32]

Artists' books began to proliferate in the sixties and seventies in the prevailing climate of social and political activism. Inexpensive, disposable editions were one manifestation of the dematerialization of the art object and the new emphasis on process.... It was at this time too that a number of artist-controlled alternatives began to develop to provide a forum and venue for many artists denied access to the traditional gallery and museum structure. Independent art publishing was one of these alternatives, and artists' books became part of the ferment of experimental forms.

— Joan Lyons.[33]

Additionally, critical to the Fluxus and The Multiple movements was Drucker's term "democratic multiple" (46).[5] Democratic multiple refers to the creation of artists books in high edition numbers to make them more publicly available for the everyday consumer. This coincided with the rise of the Fluxus and The Multiple movements and enabled broader participation in the creation and dissemination of artist's books.

Conceptual art

[edit]The artist's book proved central to the development of conceptual art. Lawrence Weiner, Bruce Nauman and Sol LeWitt in North America, Art & Language in the United Kingdom, Maurizio Nannucci in Italy, Jochen Gerz and Jean Le Gac in France and Jaroslaw Kozlowski in Poland all used the artist's book as a central part of their art practice. An early example, the exhibition January 5–31, 1969 organised in rented office space in New York City by Seth Siegelaub, featured nothing except a stack of artists' books, also called January 5–31, 1969 and featuring predominantly text-based work by Lawrence Weiner, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, and Robert Barry. Sol LeWitt's Brick Wall, (1977), for instance, simply chronicled shadows as they passed across a brick wall, Maurizio Nannucci "M/40" with 92 typesetting pages (1967) and "Definizioni/Definitions" (1970), whilst Kozlowski's Reality (1972) took a section of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, removing all of the text, leaving only the punctuation behind. Another example is the Einbetoniertes Buch,[34] 1971 (book in concrete) by Wolf Vostell.

Louise Odes Neaderland, the founder and Director of the non-profit group International Society of Copier Artists (I.S.C.A.) helped to establish electrostatic art as a legitimate art form, and to offer a means of distribution and exhibition to Xerox book Artists. Volume 1, #1 of The I.S.C.A. Quarterly was issued in April 1982 in a folio of 50 eight by eleven inch unbound prints in black and white or color Xerography. Each contributing artist's work of Xerox art was numbered in the Table of Contents and the corresponding number was stamped on the back of each artist's work. "The format changed over the years and eventually included an Annual Bookworks Edition, which contained a box of small handmade books from the I.S.C.A. contributors."[citation needed] After the advent of home computers and printers made it easier for artists to do what the copy machine formerly did, Volume 21, #4 in June 2003 was the final issue. "The 21 years of The I.S.C.A. Quarterlies represented a visual record of artists’ responses to timely social and political issues," as well as to personal experiences.[35] The complete I.S.C.A quarterly collection is housed and catalogued at the Jaffe Center for Book Arts at the Florida Atlantic University library.[36]

Proliferation and reintegration into the mainstream

[edit]As the form has expanded, many of the original distinctive elements of artists' books have been lost, blurred or transgressed. Artists such as Cy Twombly, Anselm Kiefer and PINK de Thierry, with her series Encyclopaedia Arcadia,[37] routinely make unique, hand crafted books in a deliberate reaction to the small mass-produced editions of previous generations; Albert Oehlen, for instance, whilst still keeping artists' books central to his practice, has created a series of works that have more in common with Victorian sketchbooks. A return to the cheap mass-produced aesthetic has been evidenced since the early 90s, with artists such as Mark Pawson and Karen Reimer making cheap mass production central to their practice.

Contemporary and post-conceptual artists also have made artist's books an important aspect of their practice, notably William Wegman, Bob Cobbing, Martin Kippenberger, Raymond Pettibon, Freddy Flores Knistoff and Suze Rotolo. Book artists in pop-up books and other three-dimensional one-of-a-kind books include Bruce Schnabel, Carol Barton, Hedi Kyle, Julie Chen, Ed Hutchins and Susan Joy Share.

Many book artists working in traditional, as well as non-traditional, forms have taught and shared their art in workshops at centers such as the Center for Book Arts[38] in New York City, and the Visual Arts Studio (VisArts), the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Studio School, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Statewide Outreach Program, and the no longer extant Richmond Printmaking Workshop, all in Richmond, Virginia. Other institutions devoted to the art form include San Francisco Center for the Book, Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, and Women's Studio Workshop in Rosendale, New York.

Art book fairs

[edit]There are a variety of manners in which one can purchase and learn more about artists books. In fact, the recent boom in artists' books production and dissemination is closely linked to art book fairs:

Even if the buzz of interest in publication as an art practice around the turn of the twenty-first century resembles the hype around the “artist’s book” in the 1970s, the phenomenon of art book fairs in this quantity and intensity is something new. (...) Art book fairs today are not only a venue for representing a separate, prior publishing scene, they are also a central forum for constituting and nurturing a community around publishing as artistic practice.

— Michalis Pichler[39]

Many bookstores facilitate the dissemination of artists books. Printed Matter in New York City hosts an expansive collection of purchasable artists books. They offer artists the opportunity to submit their book for printing and then selling in their store, giving artists a platform to disseminate their work. Printed Matter is also an important distributor of artists books for both individuals and institutions.

One other important way to find and/or buy artists books is through Artists Book Fairs, which provide spaces for artists and their appreciators to come together and share/disseminate/buy artist books. Tony White provides a list of some artist books fairs that offer a place for dissemination and sharing:

Artist book fairs (Los Angeles, New York, Seoul, Tokyo, Mexico City, etc.); Codex International Book Art Fair; 8-Ball Zine Fair (Tokyo); I Never Read, Art Book Fair Basel; Libros Mutantes Madrid; MISS Read Artist Book Fair (Berlin); Offprint Art Book Fair Paris and London; Rencontres d’Arles" — Tony White[4]

Critical reception

[edit]In the early 1970s the artist's book began to be recognized as a distinct genre, and with this recognition came the beginnings of critical appreciation of and debate on the subject. Institutions devoted to the study and teaching of the form were founded (The Center for Book Arts in New York, for example); library and art museum collections began to create new rubrics with which to classify and catalog artists' books and also actively began to expand their fledgling collections; new collections were founded (such as Franklin Furnace in New York); and numerous group exhibitions of artist's books were organized in Europe and America (notably one at Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia in 1973, the catalog of which, according to Stefan Klima's Artists Books: A Critical Survey of the Literature, is the first place the term "Artist's Book" was used). Artists' books became a popular form for feminist artists beginning in the 1970s. The Women's Studio Workshop (NY) and the Women's Graphic Center at the Woman's Building (LA), founded by graphic designer, Sheila de Bretteville were centers where women artists could work and explore feminist themes.[40] Bookstores specializing in artists' books were founded, usually by artists, including Ecart in 1968 (Geneva), Other Books and So in 1975 (Amsterdam), Art Metropole in 1974 (Toronto) and Printed Matter in New York (1976). All of these also had publishing programmes over the years, and the latter two are still active today.

In the 1980s this consolidation of the field intensified, with an increasing number of practitioners, greater commercialization, and also the appearance of a number of critical publications devoted to the form. In 1983, for example, Cathy Courtney began a regular column for the London-based Art Monthly (Courtney contributed articles for 17 years, and this feature continues today with different contributors). The Library of Congress adopted the term artists books in 1980 in its list of established subjects, and maintains an active collection in its Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

In the 1980s and 1990s, BA, MA and MFA programs in Book Art were founded, some notable examples of which are the MFA at Mills College in California, the MFA at The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, the MA at Camberwell College of Arts in London, and the BA at the College of Creative Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The Journal of Artists' Books (JAB) was founded in 1994 to "raise the level of critical inquiry about artists' books."

In 1994, a National Book Art Exhibition,[41] Art ex libris,[42][43] was held at Artspace Gallery in Richmond, Virginia, and the Virginia Commission for the Arts awarded a technical assistance grant for videotaping the exhibition.[44]

In 1995, excerpts from Art ex Libris: The National Book Art Invitational at Artspace video documentary were shown in the Frances and Armand Hammer Auditorium at the 4th Biannual Book Arts Fair sponsored by Pyramid Atlantic Art Center at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. In 1996, the Art ex Libris documentary was included in an auction at Swann Galleries to benefit the Center for Book Arts in New York City. Many of the books exhibited in Art ex Libris at Artspace Gallery and Art ex Machina at 1708 Gallery are now in the Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry in Miami, Florida.

In recent decades the artist's book has been developed, by way of the artists' record album concept pioneered by Laurie Anderson into new media forms including the artist's CD-ROM and the artist's DVD-ROM. Beginning in 2007, the Codex Foundation began its Book Fair and Symposium,[45] a biennial 4-day event in the San Francisco Bay Area attended by collectors and producers of artist books as well as laypeople and academics interested in the medium.

Critical issues and debate

[edit]A number of critical issues around artists' book have been debated, including their content, form, function, and usage. These issues and debates include:

- The exact definition, naming, and understanding of an artist book

- Artist's book craft as an implicitly political act and its challenge to imagine a new kind of reading.[46]

- How artists' books act as catalysts for social change, especially in challenging heteronormativeunderstandings of the art field[11]

- With that, how Queer people and the creation of artists' books intersect[47]

- Artists' books specifically not engaging in social and political change, only focusing on textual wordplay[11]

- How artists' books reimagine public art[48]

- The relationship between artists' books and corporeality (that is, of the body)

The name itself has been called into question and an exact definition is hard to create. There are many different terms that often overlap, and thus distinguishing between the terms "artist's book", "book art", "bookworks", "livre d'artiste", fine press books, etc. can be difficult. Some scholars and artists argue that the definition should be encapsulated in its broadest sense; as Tony White argues, "the simplest definition uses the Duchampian prompt: 'It's an artist book if the artist says it is'" (99).[4] Lucy Lippard argues that the term artist book refers to an entirely distinct form of art: "neither an art book (collected reproductions of separate art works) nor a book on art (critical exegeses and/or artists’ writings), the artist’s book is a work of art on its own, conceived specifically for the book form and often published by the artist him/herself" (quoted in White, 45).[4][5] John Perreault follows on this thinking, determining that artists' books "make art statements in their own right, within the context of art rather than of literature" (15).[51] Ulises Carrión builds upon this, understanding artists' books as autonomous forms that are not reduced only to text, like a traditional book.[52] This thinking mostly comes about because artists' books are often a production, something to be experienced and engaged with rather than simply read (17).[51] Nevertheless, this variety of thinking and terminology about artists' books indicates there is no monolithic conception of an artist's book; it is open to a variety of definitions and interpretations.

However, some artists have asserted that the term "artist's book" is problematic and sounds outdated:

“Artist’s book” as a term is problematic because it ghettoizes, enforces the separation from broader everyday practices and limits the subversive potential of books by putting an art tag on them. (…) While extended discussions have taken place around the term, including heated debate over whether and where to put the apostrophe in artist’s book, Lawrence Weiner once cut through the Gordian knot by concluding: “Don’t call it an artist’s book, just call it a book.”

— Michalis Pichler[53]

No matter the terminology or naming convention, contemporary scholars understand the artist to have full control over the creation, meaning, and purpose of the artist's book.[3]

One critical issue related to artists' books is how they function politically. Artists' books are often artistic expressions that challenge dominant political systems, and this can occur in a variety of manners. Often, artists' books are created independently outside of the art gallery system/world, which, as White argues, is one way to challenge how "the art gallery world...[privileges] works by predominantly white, male artists" (224).[11] Working independently is a critical way to incorporate new and emerging voices, allowing for "greater equity and inclusion and for more diverse voices and perspectives" (224).[11] This notion of working independently is often combined with working through intersectionality, where the artist's lived experience directly impacts the creation of the artist's book. Clearly, this focus on incorporating new artists from a variety of backgrounds and experiences challenges white, heteronormative systems.

Queer artists, for instance, often use the artist's book form to make their lives and experiences visible in the face of oppression. Part of the reason for this is that both Queer people and artists' books "exist on the fringes of larger communities".[47] As Queer people are marginalized in our society, so are artists' books in the art world, according to Carosone and Freeman.[47] Yet, it is in this marginalization that artists' books create new narratives outside of heteronormativity and give spaces for Queer people to fully express themselves. As Carosone concludes, "I feel that there is definitely something queer about artists' books".[47] In this way, we see another example of intersectionality between the artist book form and Queer identities.

One other critical issue is how the form of the artist book is related to issues of illness and corporeality. Amanda Couch, for instance, has written extensively on how the production of artists' books mirrors forms of digestion, both in terms of the physical construction of the artist book and the experience of "digesting" an artist book when viewing the material. The actual structure of one of Couch's artist books mirrors the bodily system of digestion: "the accordion format, itself, [is] an embodiment of the digestive system, emulating the alimentary tract within the belly cavity" (9).[50] Combining with the actual materiality and structure of the artist book is the actual writing of the book. As Couch notes, she specifically constructed the text to mirror the undulating and curving structure of the digestion pathway: "the cursive text has no spaces, a scripto continua, which runs across and back along its nine-meter length. Each word is tied to the previous, to the next, and to the subsequent line, from left to right, then upside down right to left. Writing in a curve...[where] the bends also recall medical diagrams of coiled intestines" (9).[50] In this, Couch argues that the artist book is a way to visually represent physical processes of the body. This represents how artists' books can be used to simulate and/or mirror issues of the body; this, as Couch argues, allows for a more personal communication of one's body functions.

Similar to Couch's conversations, Bolaki argues that there is an increasing intersection between artists books and medical humanities.[49] Bolaki envisions artists book that talk about disabilities/illnesses as a way to stop the reduction of chronic illness stories/experiences to just medical data (21-22).[49] By this, Bolaki recognizes that many doctors favor a data-only approach to talking about chronic illness that prevents the actual lived experience of the patient from being realized (also called the medical model of disability). In examining the artists books of three separate artists, Bolaki finds that "artists' books can provide invaluable insights into a range of embodied experiences, offering in the process an intimate authority that encourages the medical and health humanities community to rethink key assumptions of illness narrative(s)" (24).[49]

One artist Bolaki discusses is Martha Hall. Hall was well-known for crafting artists books that detailed her struggles with cancer. One of her most famous works is The Rest of My Life II, which includes a box of the artist's calendar and other planning documents, detailing the intricacies, the struggles, of scheduling medical appointments in addition to her everyday life.

Bolaki utilizes the complexity of the artist book form (as demonstrated in Hall's The Rest of My Life II) to indicate how a "tactile and multi sensory engagement" like this can offer a more complete understanding of someone's experiences with disability and chronic illness (37).[49] For Hall, her doctors only considered her body in terms of its disease; they did not consider the stress and labor involved in life outside of the medical office. The artist book form communicates this understanding.

Photo gallery

[edit]-

Exhibition of Artist's books at Ystad's Art museum 2024.

-

Contemporary artist's book by Cheri Gaulke

-

Sculptural artist book

-

Title page spread / Alexey Parygin "Eclipse"

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Greenfield, Jane (2002). ABC of bookbinding: a unique glossary with over 700 illustrations for collectors and librarians. New Castle (Del.) Nottingham (GB): Oak Knoll press The Plough press. ISBN 978-1-884718-41-0.

- ^ Pigza, Jessica. "Yale University Library Research Guides: Book Art Resources: The Term Artists' Books". guides.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 2025-04-30.

- ^ a b c d "Books – Book Art – Research Guides at Virginia Commonwealth University". Guides.library.vcu.edu. 2010-05-28. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ a b c d e f White, Tony (2017), Dyki, Judy; Glassman, Paul (eds.), "Artists' books in the art and design library", The Handbook of Art and Design Librarianship, Facet, pp. 99–108, doi:10.29085/9781783302024.014, ISBN 978-1-78330-202-4, retrieved 2025-04-28

- ^ a b c Lippard, Lucy (1985). "The Artist's Book Goes Public". Artists' Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. Visual Studies Workshop Press.

- ^ a b Drucker, Johanna (2004). The Century of Artists' Books. Granary Books. p. 8.

- ^ Artists' Books: The Book As a Work of Art, 1963–1995, Bury, Scolar Press, 1995.

- ^ Martinez, Alejandro (24 January 2021). "Ten Theses on the Artist's Book". Artishock Revista. Archived from the original on 2021-01-24.

- ^ Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy Z, object 1 (Bentley 1, Erdman 1, Keynes 1) "General Title Page"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Gwendolyn Jan. Discovering Artists' Books. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-03. Retrieved 2014-04-03. Cached copy retrieved April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e White, Tony (September 2023). "artists books and After". Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America. 42 (2): 213–230. doi:10.1086/731092. ISSN 0730-7187.

- ^ For an English translation Marinetti, F. T. (1909). "The Futurist Manifesto". cscs.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ^ The Russian Avant-Garde Book, Rowell & Wye, MOMA, 2002

- ^ Although his visit didn't go particularly well, with key members of Cubo-Futurism feeling distinctly patronized by his pronouncements. See Collaborating on the Paradigm of the Future by Margarita Tupitsyn "?". Archived from the original on 2004-10-26.

- ^ The Russian Avant-Garde Book, Rowell & Wye, MOMA, 2002, p11

- ^ Marcel Duchamp Studies Online,"Duchamp's Window Display for André Breton's Le Surréalisme et la Peinture (1945) by Thomas Girst". toutfait.com. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ Julia Friedman, Beyond Symbolism and Surrealism: Alexei Remizov's Synthetic Art, Northwestern University Press, 2010.

- ^ Lawrence Weiner : books, 1968–1989 : catalogue raisonné, Dieter Schwarz. p120

- ^ The Century of Artists' Books, Drucker, Granary Books, p12

- ^ The question of the relation between avant-garde poetry and artists' books is dealt with very well in the chapter entitled "Poètes ou artistes?" in Anne Moeglin-Delcroix, Esthétique du livre d’artiste, 1960–1980 (Paris: Jean Michel Place; Biliothèque nationale de France, 1997), 60–95.

- ^ Yves Klein, Sidra Stich, Hayward Gallery, 1994

- ^ Nolle, Christian. "The Collaboration between Guy Debord & Asger Jorn from 1957–1959". Virose.pt. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ The Century of Artists' Books, Drucker, Granary Books, p73

- ^ Dieter Roth, Books + Multiples, Dobke, Hansjorg Mayer 2004

- ^ "Collection of Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY". Moma.org. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ Ekdahl, Ekdahl. Artists Books and Beyond (PDF). Ifla.org. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ Hickey, Dave (January 1997). "Edward Ruscha: Twentysix Gasoline Stations, 1962 – photographer". Artforum. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ Mr Fluxus, Williams, Noel, Thames and Hudson, 1997

- ^ "Fluxus Archive". Artnotart.com. Archived from the original on 2013-09-02. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ Humphrey, Jr., Thomas MacGillivray. "The Fluxus File" (PDF). BroadStrokes. II (6). Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ The term Multiple had first been used by Daniel Spoerri to describe his Edition MAT mass-produced sculptures in 1959

- ^ "Fluxus Heidelberg Center – Overview Publications". Fluxusheidelberg.org. Archived from the original on 2012-08-03. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ quoted in The Century of Artists' Books, Drucker, Granary Books, p72

- ^ Hubert Kretschmer. "Archive Artist Publications – KatalogSuche-Ergebnisse". Artistbooks.de. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ Ashley Miller; Seth Thompson. "The International Society of Copier Artists (I.S.C.A) Quarterly". Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ "Jaffe Center for Book Arts". Library.fau.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-08-02. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ Perrée, Rob Cover to Cover – The Artist's Book in Perspective - N.A.I. Publishers, Rotterdam 2002

- ^ "About". Center for Book Arts. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ Pichler, Michalis (25 March 2019). "Art Book Fairs as Public Spheres". mitpress.mit.edu. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Allen, Mike (5 January 2018). "Artist's books open feminist themes". Arts & Extras. Roanoke Times. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Connor, Sibella (March 11, 1994). "By the Book: This art goes beyond words to touch the reverent reader". Richmond, Virginia: Richmond Times-Dispatch. p. C1.

- ^ Roberts-Pullen, Paulette (March 1994). "Pagination Imagination: Artspace explores the form and function of books". Style Weekly.

- ^ Bullard, CeCe (February 17, 1994). "Getting a good read on books as fine art". Richmond, Virginia: Richmond Times-Dispatch. p. D24.

The essence of a book is communication, but that is by no means the end of a book's possibilities. A book is sculpture. A book is a mixed-media assemblage. A book is a concept. A book may be a symbol. A book can become an icon. In "Art Ex Libris: The National Book Art Exhibition now at Artspace, more than a hundred artists explore and extend the possibilities of a book as something more than words on paper.

- ^ "Davi Det Hompson". Richmond, Virginia: Style Weekly. December 17, 1996. p. 35.

- ^ "The Foundation – About". Codex Foundation. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ Jurecic, Ann (2012). Illness as narrative. Pittsburgh series in composition, literacy, and culture. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-6190-1. OCLC 761852954.

- ^ a b c d Carosone, Michael (April 2010). "Queering Artists' Books: A Queer Critical Analysis of Artists' Books". The Blue Notebook. 4 (2): 31–39.

- ^ Speight, Elaine; Quick, Charles (2020-02-27). ""Fragile Possibilities": The Role of the Artist's Book in Public Art". Arts. 9 (1): 32. doi:10.3390/arts9010032. ISSN 2076-0752.

- ^ a b c d e Bolaki, Stella (March 2020). "Contemporary Artists' Books and the Intimate Aesthetics of Illness". Journal of Medical Humanities. 41 (1): 21–39. doi:10.1007/s10912-019-09596-4. ISSN 1041-3545. PMC 7052030. PMID 31879836.

- ^ a b c Couch, Amanda (2020-03-01). "Reflections on Digestions and Other Corporealities in Artists' Books". Journal of Medical Humanities. 41 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1007/s10912-019-09592-8. ISSN 1573-3645. PMID 31808022.

- ^ a b Perreault, John (1973). Vanderlip, Dianne Perry (ed.). "Some Thoughts on Books As Art". Artists Books. Moore College of Art ... 23 March-20 April 1973. University Art Museum, Berkeley ... 16 January-24 February 1974.

- ^ Carrión, Ulises (1985). "The New Art of Making Books". In Lyons, Joan (ed.). ARTISTS' A Critical Anthology. BOOKS: and Sourcebook. Visual Studies Workshop Press. pp. 31–43.

- ^ Pichler, Michalis (9 December 2019). "artist's book as a term is problematic". 3:AM Magazine. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Abt, Jeffrey (1986) The Book Made Art: A Selection of Contemporary Artists' Books

- Alexander, Charles, ed. (1995) Talking the Boundless Book: Art, Language, and the Book Arts

- Bernhard Cella(2012) Collecting Books: A selection of recent Art and Artists' Books produced in Austria [1] [2], a YouTube Video that is part of the project.

- Bleus, Guy (1990) Art is Books

- Borsuk, Amaranth (2018). The Book. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press

- Bright, Betty (2005) No Longer Innocent: Book Art in America, 1960–1980

- Bringhurst, Robert, Koch, Peter Rutledge. (2011)The Art of the Book in California: Five Contemporary Presses Stanford: Stanford University Libraries, ISBN 978-0-911221-46-6

- Brown, Kathryn, ed. (2013), The Art Book Tradition in Twentieth-Century Europe: Picturing Language.

- Bury, Stephen (1995) Artists' Books: The Book As a Work of Art, 1963–1995

- Carrion, Ulises (2024) Bookworks and Beyond, eds. Sal Hamerman and Javier Rivero Ramos. ISBN 9780691973890

- Castleman, Riva (1994) A Century of Artists Books

- Celant, Germano, translated from the Italian by Corine Lotz (1972) Book as Artwork, 1960–72

- Celant, Germano and Tim Guest (1981) Books by Artists

- Firshing Brown, Ellen. "Beyond words – Artists' Books in Modernism Magazine (2008)". publishing.yudu.com. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Friedman, Julia. Beyond Symbolism and Surrealism: Alexei Remizov's Synthetic Art, Northwestern University Press, 2010. ISBN 0-8101-2617-6 (Trade Cloth)

- Fusco, Maria and Ian Hunt (2006) Put About: A Critical Anthology on Independent Publishing

- Hildebrand-Schat, Viola and Stefan Soltek: Art by the Book (German), ed. by Klingspor Museum Offenbach, Lindlar 2013. Die Neue Sachlichkeit, ISBN 978-3-942139-32-8

- Hubert, Rennée Riese, and Judd D. Hubert (1999) The Cutting Edge of Reading: Artists' Books

- Lauf, Cornelia and Clive Phillpot (1998) Artist/Author: Contemporary Artists' Books

- Leszek Brogowski, Éditer l’art. Le livre d’artiste et l’histoire du livre, nouvelle édition revue et augmentée, Rennes, Éditions Incertain Sens, coll. "Grise" (ISBN 978-2-914291-77-4)

- Johanna Drucker (1994). The Century of Artists' Books. Granary Books. ISBN 9781887123693.

- Johanna Drucker, (1998) Figuring the Word: Essays on Books, Writing, and Visual Poetics

- Jury, David, ed. (2007) Book Art Object Berkeley: Codex Foundation, ISBN 978-0-9817914-0-1

- Jones, Shirley (2019). Mezzotint and the Artist's Book: a forty year journey (The Red Hen Press)

- Jury, David, Koch, Peter Rutledge, eds. (2013) Book Art Object 2 Berkeley: Codex Foundation and Stanford: Stanford University Libraries, ISBN 978-0-911221-50-3

- Khalfa, Jean (2001) The Dialogue between Painting and Poetry: Livres d'Artistes 1874–1999, Black Apollo Press

- Klima, Stefan (1998) Artists Books: A Critical Survey of the Literature

- Lippard, Lucy (1973) Six years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972

- Lyons, Joan, ed. (1985) Artists' Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook

- Martinez, Alejandro (2021). "Ten Theses on the Artist's Book". Artishock.

- Moeglin-Delcroix, Anne. (1997) Esthétique du livre d’artiste, 1960-1980. Paris: Jean-Michel Place; Biliothèque nationale de France.

- Maurizio Nannucci, "Artists' Books", Palazzo Strozzi, Florence 1978

- Pace, Jessica, Di Gennaro, Lou, Jenks, Josephine, AND Stephens, Catherine. "Artist Interviews as a Tool in the Preservation of Artists’ Books" RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Cultural Heritage 25 Number 2 (21 November 2024)

- Perrée, Rob (2002) Cover to Cover: The Artist's Book in Perspective

- Pichler, Michalis (2019), Publishing Manifestos MIT Press, Cambridge, MA [3]

- Phillpot, Clive (2013). Booktrek: Selected Essays on Artists' Books (1972–2010). Switzerland: JRP/Ringier, ISBN 978-3-03764-207-8

- Phillpot, Clive (1982). "Real Lush". ArtForum.

- Smith, Keith (1989) Structure of the Visual Book

- Umbrella, founded and edited by Judith Hoffberg, is one of the oldest online periodicals covering artists’ books and other multiple editions. Available online for the years 1978–2005 through the Digital Collections of the IUPUI University Library.

Artist's book

View on GrokipediaAn artist's book is a publication conceived, designed, and often produced by an artist, in which the book form itself functions as an integral element of the artistic expression, integrating visual, textual, and structural components to convey conceptual ideas.[1][2] Unlike traditional illustrated books or luxury livres d'artistes featuring commissioned artwork for literary texts, artist's books prioritize the artist's autonomous vision, frequently employing experimental formats such as altered bindings, non-linear narratives, or multimedia elements to challenge conventional reading and publishing practices.[3] Emerging prominently in the early 20th century through avant-garde movements like Futurism and Dada—exemplified by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's Zang Tumb Tumb (1914), which used typographic innovation to simulate auditory experiences of battle— the genre expanded post-World War II with conceptual approaches by artists such as Ed Ruscha, whose deadpan photographic volumes like Various Small Fires and Milk (1964) documented mundane subjects to probe perception and seriality, and Dieter Roth, who incorporated organic materials prone to decomposition to explore themes of entropy and impermanence.[4][5] Defining characteristics include democratic production methods, often in limited self-published editions, which democratize access to original art while subverting mass-market commodification, and a focus on the book's materiality as a sculptural or performative object.[6][7] These works have influenced interdisciplinary fields, from Fluxus events to contemporary digital hybrids, underscoring the book's enduring versatility as a site for artistic inquiry unbound by gallery conventions.[8]