Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aztec codex

View on Wikipedia

Aztec codices (Nahuatl languages: Mēxihcatl āmoxtli, pronounced [meːˈʃiʔkatɬ aːˈmoʃtɬi]; sg.: codex) are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.[1] Most of their content is pictorial in nature and they come from the multiple Indigenous groups from before and after Spanish contact. Differences in styles indicate regional and temporal differences. The types of information in manuscripts fall into several broad categories: calendar or time, history, genealogy, cartography, economics/tributes, census and cadastral, and property plans. Codex Mendoza and the Florentine Codex are among the important and popular colonial-era codices. The Florentine Codex, for example is known for providing a Mexica narrative of the Spanish Conquest from the viewpoint of the Indigenous people, instead of Europeans.

History

[edit]Before the start of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Mexica and their neighbors in and around the Valley of Mexico relied on painted books and records to document many aspects of their lives. Painted manuscripts contained information about their history, science, land tenure, tribute, and sacred rituals.[2] According to the testimony of Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Moctezuma had a library full of such books, known as amatl, or amoxtli, kept by a calpixqui or nobleman in his palace, some of them dealing with tribute.[3] After the conquest of Tenochtitlan, Indigenous nations continued to produce painted manuscripts, and the Spaniards came to accept and rely on them as valid and potentially important records. The native tradition of pictorial documentation and expression continued strongly in the Valley of Mexico several generations after the arrival of Europeans, its latest examples reaching into the early seventeenth century.[2]

Formats

[edit]Since the 19th century, the word codex has been applied to all Mesoamerican pictorial manuscripts, regardless of format or date, despite the fact that pre-Hispanic Aztec manuscripts were (strictly speaking) non-codical in form.[4] Aztec codices were usually made from long sheets of fig-bark paper (amate) or stretched deerskins sewn together to form long and narrow strips; others were painted on big cloths.[5] Thus, usual formats include screenfold books, strips known as tiras, rolls, and cloths, also known as lienzos. While no Aztec codex preserves its covers, from the example of Mixtec codices it is assumed that Aztec screenfold books had wooden covers, perhaps decorated with mosaics in turquoise, as the surviving wooden covers of Codex Vaticanus B suggests.[6]

Writing and pictography

[edit]Aztec codices differ from European books in that most of their content is pictorial in nature. In regards to whether parts of these books can be considered as writing, current academics are divided in two schools: those endorsing grammatological perspectives, which consider these documents as a mixture of iconography and writing proper,[7] and those with semasiographical perspectives, which consider them a system of graphic communication which admits the presence of glyphs denoting sounds (glottography).[8] In any case, both schools coincide in the fact that most of the information in these manuscripts was transmitted by images, rather than by writing, which was restricted to names.[9]

Style and regional schools

[edit]According to Donald Robertson, the first scholar to attempt a systematic classification of Aztec pictorial manuscripts, the pre-Conquest style of Mesoamerican pictorials in Central Mexico can be defined as being similar to that of the Mixtec. This has historical reasons, for according to Codex Xolotl and historians like Ixtlilxochitl, the art of tlacuilolli or manuscript painting was introduced to the Tolteca-Chichimeca ancestors of the Tetzcocans by the Tlaoilolaques and Chimalpanecas, two Toltec tribes from the lands of the Mixtecs.[10] The Mixtec style would be defined by the usage of the native "frame line", which has the primary purpose of enclosing areas of color. as well as to qualify symbolically areas thus enclosed. Colour is usually applied within such linear boundaries, without any modeling or shading. Human forms can be divided into separable, component parts, while architectural forms are not realistic, but bound by conventions. Tridimensionality and perspective is absent. In contrast, post-Conquest codices present the use of European contour lines varying in width, and illusions of tridimensionality and perspective.[4] Later on, Elizabeth Hill-Boone gave a more precise definition of the Aztec pictorial style, suggesting the existence of a particular Aztec style as a variant of the Mixteca-Puebla style, characterized by more naturalism[11] and the use of particular calendrical glyphs that are slightly different from those of the Mixtec codices.

Regarding local schools within the Aztec pictorial style, Robertson was the first to distinguish three of them:

- School of Mexico Tenochtitlan: Based at the imperial capital of Tenochtitlan, it comprises two stages, an early one which would include the Matrícula de Tributos, Plano en Papel de Maguey, Codex Boturini and the Codex Borgia; and a later one, which would comprise Codex Mendoza, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, Codex Osuna, Codex Mexicanus and the Magliabechiano Group.

- School of Texcoco: Based at the Texcoco polity (altepetl), this school comprises documents related to the court of Nezahualcoyotl. Its foremost representativese are the Mapa Quinatzin, Mapa Tlotzin, Codex Xolotl, Codex en Cruz, the Boban Calendar Wheel, and the Relaciones Geográficas de Texcoco.

- School of Tlatelolco: Based at the sister-city of Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, this school is associated with the Badianus herbal, the Mapa de Santa Cruz, the Codex of Tlatelolco and the Florentine Codex.

Survival and preservation

[edit]A large number of prehispanic and colonial Indigenous texts have been destroyed or lost over time. For example, when Hernan Cortés and his six hundred conquistadores landed on the Aztec land in 1519, they found that the Aztecs kept books both in temples and in libraries associated to palaces such as that of Moctezuma. For example, besides the testimony of Bernal Díaz quoted above, the conquistador Juan Cano de Saavedra describes some of the books to be found at the library of Moctezuma, dealing with religion, genealogies, government, and geography, lamenting their destruction at the hands of the Spaniards, for such books were essential for the government and policy of Indigenous nations.[12] Further loss was caused by Catholic priests, who destroyed many of the surviving manuscripts during the early colonial period, burning them because they considered them idolatrous.[13]

The large extant body of manuscripts that did survive can now be found in museums, archives, and private collections. There has been considerable scholarly work on the classification, description, and analysis of these codices. A major publication project by scholars of Mesoamerican ethnohistory was brought to fruition in the 1970s: volume 14 of the Handbook of Middle American Indians, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources: Part Three is devoted to Middle American pictorial manuscripts, including numerous reproductions of single pages of important pictorials. This volume includes John B. Glass and Donald Robertson's survey and catalogue of Mesoamerican pictorials, comprising 434 entries, many of which originate in the Valley of Mexico.

Three Aztec codices have been considered as being possibly pre-Hispanic: Codex Borbonicus, the Matrícula de Tributos and the Codex Boturini. According to Robertson, no pre-Conquest examples of Aztec codices survived, for he considered the Codex Borbonicus and the Codex Boturini as displaying limited elements of European influence, such as the space apparently left to add Spanish glosses for calendric names in the Codex Borbonicus and some stylistic elements of trees in Codex Boturini.[4] Similarly, the Matrícula de Tributos seems to imitate European paper proportions, rather than native ones. However, Robertson's views, which equated Mixtec and Aztec style, have been contested by Elizabeth-Hill Boone, who considered a more naturalistic quality of the Aztec pictorial school. Thus, the chronological situation of these manuscripts is still disputed, with some scholars being in favour of them being pre-Hispanic, and some against.[14]

Classification

[edit]The types of information in manuscripts fall into several categories: calendrical, historical, genealogical, cartographic, economic/tribute, economic/census and cadastral, and economic/property plans.[15] A census of 434 pictorial manuscripts of all of Mesoamerica gives information on the title, synonyms, location, history, publication status, regional classification, date, physical description, description of the work itself, a bibliographical essay, list of copies, and a bibliography.[16] Indigenous texts known as Techialoyan manuscripts are written on native paper (amatl) are also surveyed. They follow a standard format, usually written in alphabetic Nahuatl with pictorial content concerning a meeting of a given Indigenous pueblo's leadership and their marking out the boundaries of the municipality.[17] A type of colonial-era pictorial religious texts are catechisms called Testerian manuscripts. They contain prayers and mnemonic devices, some of which were deliberately falsified.[18] John B. Glass published a catalog of such manuscripts that were published without the forgeries being known at the time.[19]

Another mixed alphabetic and pictorial source for Mesoamerican ethnohistory is the late sixteenth-century Relaciones geográficas, with information on individual Indigenous settlements in colonial Mexico, created on the orders of the Spanish crown. Each relación was ideally to include a pictorial of the town, usually done by an Indigenous resident connected with town government. Although these manuscripts were created for Spanish administrative purposes, they contain important information about the history and geography of Indigenous polities.[20][21][22][23]

Important codices

[edit]Particularly important colonial-era codices that are published with scholarly English translations are Codex Mendoza, the Florentine Codex, and the works by Diego Durán. Codex Mendoza is a mixed pictorial, alphabetic Spanish manuscript.[24] Of supreme importance is the Florentine Codex, a project directed by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, who drew on Indigenous informants' knowledge of Aztec religion, social structure, natural history, and includes a history of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Mexica viewpoint.[25] The project resulted in twelve books, bound into three volumes, of bilingual Nahuatl/Spanish alphabetic text, with illustrations by native artists; the Nahuatl has been translated into English.[26] Also important are the works of Dominican Diego Durán, who drew on Indigenous pictorials and living informants to create illustrated texts on history and religion.[27]

The colonial-era codices often contain Aztec pictograms or other pictorial elements. Some are written in alphabetic text in Classical Nahuatl (in the Latin alphabet) or Spanish, and occasionally Latin. Some are entirely in Nahuatl without pictorial content. Although there are very few surviving prehispanic codices, the tlacuilo (codex painter) tradition endured the transition to colonial culture; scholars now have access to a body of around 500 colonial-era codices.

Some prose manuscripts in the Indigenous tradition sometimes have pictorial content, such as the Florentine Codex, Codex Mendoza, and the works of Durán, but others are entirely alphabetic in Spanish or Nahuatl. Charles Gibson has written an overview of such manuscripts, and with John B. Glass compiled a census. They list 130 manuscripts for Central Mexico.[28][29] A large section at the end has reproductions of pictorials, many from central Mexico.

List of Aztec codices

[edit]

- Anales de Cuauhtitlan, a 16th century text in Nahuatl, is one part of Codex Chimalpopoca

- Anales de Tlatelolco, an early colonial era set of annals written in Nahuatl, with no pictorial content. It contains information on Tlatelolco's participation in the Spanish conquest.

- Badianus Herbal Manuscript is formally called Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis (Latin for "Little Book of the Medicinal Herbs of the Indians") is a herbal manuscript, describing the medicinal properties of various plants used by the Aztecs. It was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano, from a Nahuatl original composed in the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1552 by Martín de la Cruz that is no longer extant. The Libellus is better known as the Badianus Manuscript, after the translator; the Codex de la Cruz-Badiano, after both the original author and translator; and the Codex Barberini, after Cardinal Francesco Barberini, who had possession of the manuscript in the early 17th century.[30]

- Chavero Codex of Huexotzingo is a codex on late 16th century tax collecting in Huexotzingo

- Codex Azcatitlan, a pictorial history of the Aztec empire, including images of the conquest

- Codex Aubin is a pictorial history or annal of the Aztecs from their departure from Aztlán, through the Spanish conquest, to the early Spanish colonial period, ending in 1608. Consisting of 81 leaves, it is two independent manuscripts, now bound together. The opening pages of the first, an annals history, bear the date of 1576, leading to its informal title, Manuscrito de 1576 ("The Manuscript of 1576"), although its year entries run to 1608. Among other topics, Codex Aubin has a native description of the massacre at the temple in Tenochtitlan in 1520. The second part of this codex is a list of the native rulers of Tenochtitlan, up to 1607. It is held by the British Museum and a copy of its commentary is at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. A copy of the original is held at the Princeton University library in the Robert Garrett Collection. The Aubin Codex is not to be confused with the similarly named Aubin Tonalamatl.[31]

- Codex Borbonicus is written by Aztec priests sometime after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Like all pre-Columbian Aztec codices, it was originally pictorial in nature, although some Spanish descriptions were later added. It can be divided into three sections: An intricate tonalamatl, or divinatory calendar; documentation of the Mesoamerican 52-year cycle, showing in order the dates of the first days of each of these 52 solar years; and a section of rituals and ceremonies, particularly those that end the 52-year cycle, when the "new fire" must be lit. Codex Bornobicus is held at the Library of the National Assembly of France.

- Codex Borgia – pre-Hispanic ritual codex, after which the group Borgia Group is named. The codex is itself named after Cardinal Stefano Borgia, who owned it before it was acquired by the Vatican Library.

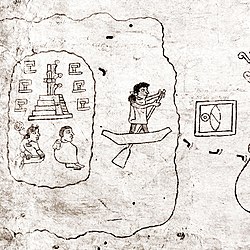

- Codex Boturini or Tira de la Peregrinación was painted by an unknown author sometime between 1530 and 1541, roughly a decade after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. Pictorial in nature, it tells the story of the legendary Aztec journey from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico. Rather than employing separate pages, the author used one long sheet of amatl, or fig bark, accordion-folded into 21½ pages. There is a rip in the middle of the 22nd page, and it is unclear whether the author intended the manuscript to end at that point or not. Unlike many other Aztec codices, the drawings are not colored, but rather merely outlined with black ink. Also known as "Tira de la Peregrinación" ("The Strip Showing the Travels"), it is named after one of its first European owners, Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci (1702 – 1751). It is now held in the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.

- Codex Chimalpahin, a collection of writings attributed to colonial-era historian Chimalpahin concerning the history of various important city-states.[32]

- Codex Chimalpopoca contains stories of the hero-god Quetzalcoatl

- Codex Cospi, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Cozcatzin, a post-conquest, bound manuscript consisting of 18 sheets (36 pages) of European paper, dated 1572, although it was perhaps created later than this. Largely pictorial, it has short descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl. The first section of the codex contains a list of land granted by Itzcóatl in 1439 and is part of a complaint against Diego Mendoza. Other pages list historical and genealogical information, focused on Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan. The final page consists of astronomical descriptions in Spanish. It is named for Don Juan Luis Cozcatzin, who appears in the codex as "alcalde ordinario de esta ciudad de México" ("ordinary mayor of this city of Mexico"). The codex is held by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

- Codex en Cruz - a single piece of amatl paper, it is currently held by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

- Codex Fejérváry-Mayer – pre-Hispanic calendar codex, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Florentine is a set of 12 books created under the supervision of Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún between approximately 1540 and 1576. The Florentine Codex has been the major source of Aztec life in the years before the Spanish conquest. Charles Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson published English translations of the Nahuatl text of the twelve books in separate volumes, with redrawn illustrations. A full color, facsimile copy of the complete codex was published in three bound volumes in 1979.

- Codex Ixtlilxochitl, an early 17th-century codex fragment detailing, among other subjects, a calendar of the annual festivals and rituals celebrated by the Aztec teocalli during the Mexican year. Each of the 18 months is represented by a god or historical character. Written in Spanish, the Codex Ixtlilxochitl has 50 pages comprising 27 separate sheets of European paper with 29 drawings. It was derived from the same source as the Codex Magliabechiano. It was named after Fernando de Alva Cortés Ixtlilxochitl (between 1568 & 1578 - c. 1650), a member of the ruling family of Texcoco, and is held in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and published in 1976.[33] Page by page views of the manuscript are available online.[34]

- Codex Laud, part of the Borgia Group.

- Codex Magliabechiano was created during the mid-16th century, in the early Spanish colonial period. Based on an earlier unknown codex, the Codex Magliabechiano is primarily a religious document, depicting the 20 day-names of the tonalpohualli, the 18 monthly feasts, the 52-year cycle, various deities, Indigenous religious rites, costumes, and cosmological beliefs. The Codex Magliabechiano has 92 pages made from Europea paper, with drawings and Spanish language text on both sides of each page. It is named after Antonio Magliabechi, a 17th-century Italian manuscript collector, and is held in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence, Italy.

- Codex Mendoza is a pictorial document, with Spanish annotations and commentary, composed circa 1541. It is divided into three sections: a history of each Aztec ruler and their conquests; a list of the tribute paid by each tributary province; and a general description of daily Aztec life. It is held in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford.[35]

- Codex Mexicanus a pictorial manuscript of Aztec calendar, writing system, history of the Mexica and other cultural facets

- Codex Osuna is a mixed pictorial and Nahuatl alphabetic text detailing complaints of particular Indigenous against colonial officials.

- Codex Porfirio Díaz, sometimes considered part of the Borgia Group

- Codex Ramírez manuscript created by Juan de Tovar contains history of the Aztecs and is presumably a draft of Codex Tovar

- Codex Reese - a map of land claims in Tenotichlan discovered by the famed manuscript dealer William Reese.[36]

- Codex Ríos - an Italian translation and augmentation of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

- Codex Santa Maria Asunción - Aztec census, similar to Codex Vergara; published in facsimile in 1997.[37]

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis - calendar, divinatory almanac and history of the Aztec people, published in facsimile.[38]

- Codex of Tlatelolco is a pictorial codex, produced around 1560.

- Codex Tovar - a history by Juan de Tovar.

- Codex Vaticanus B, part of the Borgia Group

- Codex Vergara - records the border lengths of Mesoamerican farms and calculates their areas.[39]

- Codex Xolotl - a pictorial codex recounting the history of the Valley of Mexico, and Texcoco in particular, from Xolotl's arrival in the Valley to the defeat of Azcapotzalco in 1428.[40]

- Crónica Mexicayotl, Hernando Alvarado Tezozomoc, prose manuscript in the native tradition.

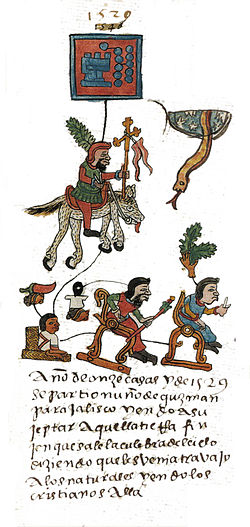

- Huexotzinco Codex, Nahua pictorials that are part of a 1531 lawsuit by Hernán Cortés against Nuño de Guzmán that the Huexotzincans joined.

- Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2 - a post-conquest Indigenous map, legitimizing the land rights of the Cuauhtinchantlacas.

- Mapa Quinatzin is a sixteenth-century mixed pictorial and alphabetic manuscript concerning the history of Texcoco. It has valuable information on the Texcocan legal system, depicting particular crimes and the specified punishments, including adultery and theft. One striking fact is that a judge was executed for hearing a case that concerned his own house. It has name glyphs for Nezahualcoyotal and his successor Nezahualpilli.[41]

- Matrícula de Huexotzinco. Nahua pictorial census and alphabetic text, published in 1974.[42]

- Oztoticpac Lands Map of Texcoco, 1540 is a pictorial on native amatl paper from Texcoco ca. 1540 relative to the estate of Don Carlos Chichimecatecatl of Texcoco.

- Romances de los señores de Nueva España - a collection of Nahuatl songs transcribed in the mid-16th century

- Santa Cruz Map. Mid-sixteenth-century pictorial of the area around the central lake system.[43]

- Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco

- Map of the Founding of Tetepilco, found in 2024, "about the foundation of San Andrés Tetepilco and includes lists of toponyms within the region"[44]

- Inventory of the Church of San Andrés Tetepilco, found in 2024, "a pictographic inventory of the church and its assets"[44]

- Tira of San Andrés Tetepilco, history of Tenochtitlan from foundation to 17th century[44]

- Tira de la Peregrinación see Codex Boturini

Legacy

[edit]Continued scholarship of the codices has been influential in contemporary Mexican society, particularly for contemporary Nahuas who are now reading these texts to gain insight into their own histories.[45][46] Research on these codices has also been influential in Los Angeles, where there is a growing interest in Nahua language and culture in the 21st century.[47][48]

See also

[edit]- Codex Zouche-Nuttall - one of the Mixtec codices. Codex Zouche-Nuttall is in the British Museum.

- Crónica X

- Historia de Mexico with the Tovar calendar, ca. 1830–1862. From the Jay I Kislak Collection at the Library of Congress

- Maya codices

- Mesoamerican literature

- Colonial Mesoamerican native-language texts

References

[edit]- ^ Batalla, Juan José (2016-12-05). "The Historical Sources: Codices and Chronicles". In Nichols, Deborah L.; Rodríguez-Alegría, Enrique (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–40. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199341962.013.30.

- ^ a b Boone, Elizabeth H. "Central Mexican Pictorials." In Davíd Carrasco (ed). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures. : Oxford University Press, 2001.ISBN 9780195188431

- ^ Díaz del Castillo, Bernal; Serés, Guillermo; León Portilla, Miguel (2014). Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España (Primera edición mexicana ed.). México, D.F.: Academia Mexicana de la Lengua. ISBN 978-607-95771-9-3. OCLC 1145170261.

- ^ a b c Robertson, Donald (1994). Mexican manuscript painting of the early colonial period : the metropolitan schools. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2675-2. OCLC 30436784.

- ^ Article in Mexicolore

- ^ Jansen, Maarten E. R. G. N.; Reyes García, Luis; Anders, Ferdinand (1993). Códice Vaticano B.3773. Madrid, España: Sociedad Estatal Quinto Centenario]. ISBN 968-16-4155-8. OCLC 1101345811.

- ^ Velásquez García, Erik (2018-05-31). "In memoriam Alfonso Lacadena". Estudios de Cultura Maya. 52: 306. doi:10.19130/iifl.ecm.2018.52.961. ISSN 2448-5179.

- ^ Mikulska Dąbrowska, Katarzyna (2015). Tejiendo destinos : un acercamiento al sistema de comunicación gráfica en los códices adivinatorios (Primera ed.). Zinacantepec, México, México. ISBN 978-607-7761-77-8. OCLC 951433139.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Uriarte, María Teresa (2010). De la antigua California al Desierto de Atacama (1 ed.). México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN 978-607-02-2018-0. OCLC 768827325.

- ^ Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, Fernando de; O'Gorman, Edmundo (1985). Obras históricas: incluyen el texto completo de las llamadas Relaciones e Historia de la nación chichimeca en una nueva versión establecida con el cotejo de los manuscritos más antiguos que se conocen (4a ed.). México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Impr. Universitaria. ISBN 968-837-175-0. OCLC 18797818.

- ^ Cordy-Collins, Alana; Stern, Jean (1977). Pre-Columbian art history : selected readings. Palo Alto, Calif.: Peek Publications. ISBN 0-917962-41-9. OCLC 3843930.

- ^ Martínez Baracs, Rodrigo (2006). La perdida Relación de la Nueva España y su conquista de Juan Cano (1. ed.). México, D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. ISBN 968-03-0194-X. OCLC 122937827.

- ^ Murray, Stuart A. P. (2009). Library, the : an illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. pp. 136–138. ISBN 9781628733228.

- ^ Escalante, Pablo (2010). Los códices mesoamericanos antes y después de la conquista española : historia de un lenguaje pictográfico (1. ed.). México, D.F. ISBN 978-607-16-0308-1. OCLC 666239806.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Glass, John B. "A Survey of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts", article 22, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 3-80.

- ^ Glass, John B. in collaboration with Donald Robertson. "A Census of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts". article 23, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 81-252.

- ^ Robertson, Donald. "Techialoyan Manuscripts and Paintings with a Catalog." article 24, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 253-281.

- ^ Glass, John B. "A Census of Middle American Testerian Manuscripts." article 25, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 281-296.

- ^ Glass, John B. "A Catalog of Falsified Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts." article 26, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 297-309.

- ^ Howard F. Cline "The Relaciones Geográficas of the Spanish Indies, 1577-1648", article 5. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 183-242. ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- ^ Robertson, Donald, "The Pinturas (Maps) of the Relaciones Geográficas, with a Catalog", article 6.Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 243-278.

- ^ Cline, Howard F. "A Census of the Relaciones Geográficas of New Spain, 1579-1612," article 8. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 324-369.

- ^ Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- ^ Berdan, Frances, and Patricia Rieff Anawalt. The Codex Mendoza. 4 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- ^ Sahagún, Bernardino de. El Códice Florentino: Manuscrito 218-20 de la Colección Palatina de la Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. Fascimile ed., 3 vols. Florence: Giunti Barbera and México: Secretaría de Gobernación, 1979.

- ^ Sahagún, Bernardino de. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Translated by Arthur J. O Anderson and Charles E Dibble. 13 vols. Monographs of the School of American Research 14. Santa Fe: School of American Research; Salt Lake City: University of Utah, 1950-82.

- ^ Durán, Diego. The History of the Indies of New Spain. Translated by Doris Heyden. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994. Durán, Diego. Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar. Translated by Fernando Horcasitas and Doris Heyden. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

- ^ Gibson, Charles. "Prose sources in the Native Historical Tradition", article 27B. "A Census of Middle American Prose Manuscripts in the Native Historical Tradition". Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 4; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, 326-378.

- ^ Gibson, Charles and John B. Glass. "Prose sources in the Native Historical Tradition", article 27A. "A Survey of Middle American Prose Manuscripts in the Native Historical Tradition". Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 4; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, 311-321.

- ^ An Aztec Herbal: The Classic Codex of 1552. Wm. Gates editor. Dover Publications 2000. ISBN 978-0486-41130-9

- ^ Aubin Tonalamatl, Trafficking Culture Encyclopedia

- ^ Codex Chimalpahin: Society and Politics in Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Texcoco, Culhuacan, and other Nahua Altepetl in Central Mexico. Domingo de San Antón Muñon Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuantzin, Edited and translated by Arthur J.O. Anderson, et al. 2 vols. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1997.

- ^ Jacqueline de Durand-Forest, ed. Codex Ixtlilxochitl: Bibliothèque nationale, Paris (Ms. Mex. 55-710). Fontes rerum Mexicanarum 8. Graz, Austria: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt 1976.

- ^ "FAMSI - Akademische Druck - u. Verlagsanstalt - Graz - Codex Ixtlilxochitl".

- ^ The Essential Codex Mendoza, F. Berdan and P. Anawalt, eds. University of California Press 1997. ISBN 978-0520-20454-6

- ^ Raymond, Lindsey (2010-09-24). "One man, 65,000 manuscripts". Yale Daily News. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ^ Barbara J. Williams, Harvey, H. R. (1997). The Códice de Santa María Asunción : Facsimile and Commentary : Households and Lands in Sixteenth-century Tepetlaoztoc. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-522-8

- ^ Eloise Quiñones Keber, Eloise. Codex Telleriano-Remensis: Ritual, Divination, and History in a Pictorial Aztec Manuscript. University of Texas Press 1995. ISBN 978-0-292-76901-4.

- ^ M. Jorge et al. (2011). Mathematical accuracy of Aztec land surveys assessed from records in the Codex Vergara. PNAS: University of Michigan.

- ^ Calnek, Edward E. (1973). "The Historical Validity of the Codex Xolotl". American Antiquity. 38 (4): 423–427. doi:10.2307/279147. JSTOR 279147. S2CID 161510221.

- ^ Offner, Jerome A. Law and Politics in Aztec Texcoco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1983, pp. 71-81. ISBN 978-0521-23475-7

- ^ Hans J. Prem, Matrícula de Huexotzinco. Graz: Druck und Verlagsanstalt 1974. ISBN 978-3201-00870-9

- ^ Sigvald Linné, El valle y la ciudad de México en 1550. Relación histórica fundada sobre un mapa geográfico, que se conserva en la biblioteca de la Universidad de Uppsala, Suecia. Stockholm: 1948.

- ^ a b c "Archaeologists recover 16th-century Aztec codices of San Andrés Tetepilco". 22 March 2024.

- ^ Tenorio, Rich (2021-10-07). "Scholar says 'underestimated' Mexica writing system deserves respect". Mexico News Daily. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ "Aztec renaissance: New research sheds fresh light on intellectual achievements of long-vanished empire". The Independent. 2021-04-08. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ "UCLA historian brings language of the Aztecs from ancient to contemporary times". UCLA. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ Mattei, Shanti Escalante-De (2022-02-18). "LACMA Exhibits Subvert the Totalizing Myths of Colonial Conquest". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

Further reading

[edit]- Batalla Rosado, Juan José. "The Historical Sources: Codices and Chronicles" in The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs. Oxford University Press 2017, pp. 29–40. ISBN 978-0-19-934196-2

- Howard F. Cline "The Relaciones Geográficas of the Spanish Indies, 1577-1648", article 5. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 183–242. ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- Cline, Howard F. "A Census of the Relaciones Geográficas of New Spain, 1579-1612," article 8. Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 324–369.ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- Gibson, Charles. "Prose sources in the Native Historical Tradition", article 27A. "A Survey of Middle American Prose Manuscripts in the Native Historical Tradition". Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 4; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, 311–321. ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Gibson, Charles and John B. Glass. "Prose sources in the Native Historical Tradition", article 27B. "A Census of Middle American Prose Manuscripts in the Native Historical Tradition". Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 4; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, 322–400. ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Gibson, Charles. "Published Collections of Documents Relating to Middle American Ethnohistory", article 11.Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 2; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1973, pp. 3–41. ISBN 0-292-70153-5

- Glass, John B. "A Survey of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts", article 22, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 3–80. ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Glass, John B. "A Census of Middle American Testerian Manuscripts." article 25, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 281–296. ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Glass, John B. "A Catalog of Falsified Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts." article 26, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 297–309. ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Glass, John B. in collaboration with Donald Robertson. "A Census of Native Middle American Pictorial Manuscripts". article 23, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 81–252.ISBN 0-292-70154-3

- Nicholson, H. B. “Pre-Hispanic Central Mexican Historiography.” In Investigaciones contemporáneos sobre historia de México. Memorias de la tercera reunión de historiadores mexicanos y norteamericanos, Oaxtepec, Morelos, 4–7 de noviembre de 1969, pp. 38–81. Mexico City, 1971.

- Robertson, Donald, "The Pinturas (Maps) of the Relaciones Geográficas, with a Catalog", article 6.Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 1; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1972, pp. 243–278. ISBN 0-292-70152-7

- Robertson, Donald. "Techialoyan Manuscripts and Paintings with a Catalog." article 24, Guide to Ethnohistorical Sources Part 3; Handbook of Middle American Indians. University of Texas Press 1975, pp. 253–281. ISBN 0-292-70154-3

External links

[edit]Aztec codex

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Creation

The Aztec codex tradition developed within the Mexica civilization during the Late Postclassic period (circa 1200–1521 CE), as the Aztecs established their empire in the Valley of Mexico following their migration from Aztlán around the 12th–13th centuries CE and the founding of Tenochtitlan in 1325 CE. This practice built upon broader Mesoamerican pictorial manuscript conventions, particularly the Mixteca-Puebla style originating in central Mexico from the 13th century, which emphasized ritual, calendrical, and historical content through logographic and ideographic systems.[11] Mexica codices served administrative, religious, and propagandistic functions, documenting genealogies, conquests, and tribute to reinforce imperial authority.[12] Specialized scribes known as tlacuiloque (painter-scribes) created these works, trained in elite calmecac schools where they mastered the pictographic script combining phonetic, semantic, and narrative elements. The production process began with preparing amate paper from the beaten inner bark of wild fig trees (Ficus spp.), treated with lime paste for sizing and folded into accordion-style screenfolds typically measuring 10–20 meters in length. Surfaces were coated with a fine white gesso for durability, upon which artists applied pigments—derived from minerals like cinnabar for red, azurite for blue, and charcoal for black—using brushes made from animal hair or plant fibers to render vivid, stylized imagery.[13][11] Authentic pre-Columbian Aztec codices are rare due to widespread destruction during the Spanish conquest beginning in 1519 CE, with only a few examples like the Codex Borbonicus and Codex Borgia surviving, dated to the late 15th or early 16th century and reflecting purely indigenous ritual and divinatory themes without European influence.[14] These manuscripts demonstrate the codex's role in preserving esoteric knowledge, such as the tonalpohualli ritual calendar, underscoring the Aztecs' sophisticated system of visual literacy predating alphabetic imposition.[6]Pre-Columbian Usage

![Page from Codex Boturini depicting the Aztec migration from Aztlan][float-right] In pre-Columbian Aztec society, pictorial manuscripts known as codices functioned primarily as tools for administrative, historical, and ritual record-keeping, employing a system of pictograms, ideograms, and logograms to convey events, dates, names, and concepts without alphabetic script.[15] These documents enabled efficient communication among the nobility, priests, and scribes across linguistically diverse conquered territories, facilitating governance in the expansive Triple Alliance empire centered at Tenochtitlan.[15] Administrative uses included tracking tribute payments from subjugated city-states, conducting censuses of populations and resources, and documenting imperial policies, which supported the economic and military sustenance of Aztec hegemony from the 14th to early 16th centuries.[16] [17] Historical codices preserved annals of migrations, conquests, and genealogies, legitimizing rulership and territorial claims; for instance, tira-style manuscripts like the Codex Boturini illustrated the Mexica journey from Aztlan to Tenochtitlan around 1325 CE, marking key settlements and divine signs.[1] Ritual and calendrical functions were central, with screenfold almanacs detailing the 260-day tonalamatl cycle for divination, determining auspicious days for ceremonies, warfare, agriculture, and personal events such as naming children.[18] [15] These codices integrated cosmology, associating each of the 13-day weeks with ruling deities and symbols to guide priestly interpretations of fate and ritual timing.[17] Although few authentic pre-conquest Aztec codices survive due to systematic destruction during the Spanish invasion starting in 1519, their contents and uses are reconstructed from fragments, post-conquest replicas, and archaeological context, underscoring their role in sustaining Mesoamerican intellectual traditions.[1]Spanish Conquest and Destruction

The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, culminating in the fall of Tenochtitlan on August 13, 1521, initiated widespread disruption to indigenous record-keeping traditions, including the physical destruction or neglect of codices amid the collapse of imperial structures.[4] While some losses occurred incidentally during military campaigns led by Hernán Cortés from 1519 onward, the primary eradication stemmed from post-conquest efforts by Franciscan missionaries and ecclesiastical authorities who regarded Aztec codices—containing ritual calendars, genealogies, historical annals, and religious pictographs—as instruments of idolatry and superstition warranting elimination to facilitate Christian conversion.[19] These codices, housed in institutional libraries such as the amoxcalli of Tenochtitlan and Texcoco, numbered in the hundreds to thousands across the Aztec realm prior to 1521, serving practical roles in governance, tribute assessment, and divination.[20] Juan de Zumárraga, appointed first bishop of Mexico in 1528 and serving until 1548, spearheaded much of the systematic destruction, collecting Aztec manuscripts from native archives in Texcoco and other centers during the late 1520s and early 1530s, then consigning them to flames as manifestations of pre-Christian "bad faith."[21] His actions, part of broader inquisitorial campaigns against perceived heresy, aligned with papal directives and the doctrinal imperative to extirpate polytheistic artifacts, resulting in the incineration of untold volumes that encoded Aztec cosmology, legal precedents, and imperial narratives.[22] Other friars contributed to this purge, motivated by a causal view that preserving such texts perpetuated native resistance to evangelization, though not all clergy endorsed wholesale burning—some, like Bernardino de Sahagún, later documented Aztec knowledge in supervised post-conquest compilations.[19] Aztec elites occasionally preemptively destroyed or altered records to obscure politically inconvenient histories, but Spanish initiatives dominated the scale of loss.[19] The devastation left an irrecoverable void in primary sources, with scholarly estimates indicating that of the pre-1521 Aztec codices, fewer than a dozen plausibly survived intact, and debates persist over whether any purely pre-conquest Aztec historical or administrative examples endure without colonial alterations—figures like Donald Robertson argued none do, classifying survivors such as the Codex Borbonicus as limited post-conquest replicas in style.[20] Broader Mesoamerican manuscript survival hovers around 12 to two dozen, mostly ritual or Mixtec-origin works evading destruction by export to Europe or concealment.[4] This near-total erasure compelled reliance on European-authored chronicles and hybrid native-Spanish codices for reconstructing Aztec society, underscoring the conquest's causal role in fracturing indigenous epistemic continuity.[20]Rediscovery and Preservation Efforts

Following the Spanish conquest, systematic destruction reduced the number of Aztec codices, yet some survived through export to Europe or protection by indigenous custodians and colonial collectors. The Codex Mendoza, produced in Mexico City around 1541 for transmission to Spain, was seized by French privateers during transit and preserved in French royal collections until its scholarly rediscovery in 1831.[8] Similarly, the Florentine Codex, compiled by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún with Nahua collaborators from the 1540s to 1577, reached European libraries and has been held in Florence's Laurentian Library since the late 16th century, enabling ongoing study despite early colonial disruptions.[23] Early preservation often involved missionary initiatives to document indigenous knowledge, counterbalanced by autos-da-fé burnings ordered by officials like Bishop Juan de Zumárraga in the 1520s and 1530s, which targeted perceived idolatrous texts. Surviving manuscripts, including colonial-era works like the Codex Boturini (circa 1530–1540s), were acquired by European antiquarians such as Lorenzo Boturini in the 1740s, who amassed collections later confiscated and repatriated to Mexico in the 19th century.[24] These efforts preserved pictorial histories amid broader archival losses estimated to exceed thousands of documents. Modern preservation emphasizes scientific conservation and repatriation. In March 2024, Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) recovered the three Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco—late 16th- to early 17th-century manuscripts depicting Mexica migrations—from a private family collection, subjecting them to forensic analysis, restoration, and integration into national archives.[25] Institutions like the Bodleian Libraries employ non-destructive techniques, including multispectral imaging and material spectroscopy, to assess degradation in holdings such as fragmented Aztec codices without invasive interventions.[26] Digitization initiatives, such as the 2023 Digital Florentine Codex project, produce high-resolution facsimiles to reduce handling risks while broadening access for researchers.[27] These measures address vulnerabilities from organic materials like amate paper, susceptible to humidity, insects, and prior repairs with incompatible adhesives.Modern Analysis and Interpretations

Modern scholarly analysis of Aztec codices emphasizes their hybrid nature, blending pre-Hispanic pictographic traditions with colonial alphabetic annotations, which complicates direct interpretation of indigenous intent. Most surviving examples, such as the Codex Mendoza (c. 1541) and Florentine Codex (1575–1577), were produced post-conquest by Nahua tlacuilos under Spanish auspices, incorporating Nahuatl texts alongside images to document history, tribute, and ethnography for European audiences.[28][29] Scholars like Frances F. Berdan and Patricia Rieff Anawalt argue that these works preserve authentic Aztec organizational data, such as the Mendoza's grid of conquered towns and tribute tallies numbering over 400 locales, but reflect negotiated colonial agendas rather than unaltered pre-Hispanic narratives.[30] Decipherment challenges stem from the codices' non-alphabetic script, which relies on logograms, rebuses, and contextual conventions rather than consistent phonetics, requiring deep familiarity with Nahua cosmology and rhetoric. Gordon Whittaker's 2021 study identifies phonetic components in glyphs, such as toponymic rebuses where a "water" sign (atl) prefixes names like Atlixco, enabling partial readings of rulers' names and events, yet full narratives remain elusive without corroborating oral traditions or archaeology.[31] Pre-conquest codices, rarer and mostly ritualistic like the Codex Borgia group, evade linear historical decoding, focusing instead on cyclical calendars and deities, with interpretations debated over whether they encode esoteric priestly knowledge or public mythologies.[14] Recent advancements include material science examinations, such as X-ray fluorescence on Berlin's Humboldt fragments (acquired 1803–1804), confirming amatl bark paper and pre-1521 pigments, thus authenticating origins despite fragmentation.[10] Digitization efforts, like the 2023 Getty full-color scan of the Florentine Codex's 2,400+ pages, facilitate multispectral imaging to reveal faded details, enhancing analyses of Sahagún's informant-based accounts of Aztec pharmacology and omens.[32][33] These tools counter earlier biases in colonial transcriptions, where European filters distorted indigenous views, as seen in Mendoza's idealized empire maps aligning with Spanish imperial rhetoric. Ongoing debates question the extent of Nahua agency, with 2022 reassessments positing the Mendoza as a "colonial indigenous artwork" retaining pre-Hispanic stylistic markers like stepped-fret borders.[34] Interpretations increasingly integrate interdisciplinary data, cross-referencing codices with excavations at sites like Tenochtitlan, where tribute motifs match artifact distributions, validating economic claims over ritual exaggerations.[6] However, systemic challenges persist: academic reliance on post-conquest sources risks overemphasizing hybridity at the expense of lost pre-Hispanic corpora, estimated at thousands before 1521 burnings, urging caution against projecting modern egalitarian lenses onto hierarchical Aztec depictions of warfare and sacrifice.[7] New discoveries, such as the 2024 Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco, prompt reevaluations but require verification against forgery risks highlighted in past radiocarbon disputes.[35]Formats and Materials

Types of Aztec Codices

Pre-Columbian Aztec codices, produced before the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521, represent a minuscule fraction of the original corpus, with only two to three surviving examples widely accepted as authentic Nahua works, owing to widespread destruction by Spanish forces. These manuscripts, executed in traditional pictographic style on amatl (fig-bark paper) screenfolds, primarily served ritual and divinatory purposes, such as tonalamatls—calendars mapping the 260-day tonalpohualli cycle to gods, omens, and ceremonies for priestly consultation. The Codex Borbonicus exemplifies this type, featuring sequential day signs paired with deities like Tezcatlipoca and Xiuhtecuhtli, without alphabetic text, emphasizing causal links between cosmic cycles and human actions in Mesoamerican cosmology.[1][36] Colonial Aztec codices, crafted from the 1530s onward by indigenous tlacuiloque (painters-scribes) under Spanish oversight, blend prehispanic iconography with Nahuatl or Spanish annotations to document history, administration, and culture for colonial records or native memory preservation. Historical-migration types, like the Codex Boturini (c. 1530s), trace the Mexica journey from Aztlán to Tenochtitlan via glyphic sequences of glyphs, footprints, and temples, illustrating directional causality in ethnogenesis narratives.[37] Tribute-economic variants, such as the Matrícula de Tributos (c. 1520s, possibly pre-conquest but copied post-), enumerate provincial payments in goods like cloaks and cacao to the Triple Alliance, using standardized motifs for quantification and oversight.[35] Ethnographic-religious codices form another major subtype, compiling indigenous knowledge for missionary or archival ends; the Florentine Codex (1577), directed by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún with Nahua informants, spans 12 volumes on topics from gods and omens to social customs, integrating pictographs with parallel Nahuatl and Spanish texts to capture prehispanic causal explanations of natural and social phenomena. Genealogical-legal types, including 17th-century Techialoyan manuscripts, asserted native land rights through pictorial maps, kin trees, and signatures, often hybridizing Aztec symbols with European heraldry to navigate colonial jurisprudence. These categories reflect adaptation to conquest pressures, prioritizing verifiable data like tribute tallies over narrative embellishment.[38][7]Materials Used (Bark Paper, Deer Skin, etc.)

Aztec codices were predominantly crafted from amate paper, produced by processing the inner bark of trees in the fig family, such as Ficus aurea or Trema micrantha, through soaking, cooking, and pounding to form thin, flexible sheets.[39][40] This bark paper, known as amatl in Nahuatl, was valued for its availability in Mesoamerican forests and its suitability for painting with mineral-based pigments after sizing with lime or starch for a smooth surface.[41] Archaeological evidence confirms amate production dating back centuries before the Aztec era, with sheets typically measuring 15-20 cm in width and sewn or pasted into long strips up to several meters in length.[39] Deerskin, derived from the hides of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), served as a durable alternative material, especially for codices requiring longevity or transport.[42][24] Hides were cured, stretched, scraped to remove hair and flesh, and cut into rectangular panels before assembly, providing a tougher substrate less prone to tearing than bark paper but more challenging to inscribe uniformly.[35] This material's use is documented in surviving pre-Columbian examples, where it supported detailed pictography without the need for extensive preparation beyond tanning./01:The_Changing_World(1400-1600)/1.07:Mesoamerica__Aztecs_Mixtec_Maya(1400-1521_CE)) Less frequently, cotton cloth (tlacuiloliztli) or agave fiber mats were employed for specific codices, particularly in ritual or regional contexts, though these were secondary to amate and deerskin due to higher production costs and coarser textures.[19][43] These organic supports were folded into accordion-style screenfolds, often bound with wooden covers in elite productions, enabling compact storage and sequential reading of narrative sequences.[35] The choice of material influenced durability, with bark paper susceptible to humidity and insect damage, while deerskin offered greater resilience in arid highland environments like the Valley of Mexico.[42]Techniques and Tools

Aztec codices were primarily produced using amate, a bark paper derived from the inner layer of trees such as the wild fig (Ficus cotinifolia). The production technique began with stripping the bark, which was then soaked in water or boiled to separate and soften the fibers, followed by beating the softened material with flat stones or wooden mallets to flatten it into thin, uniform sheets.[40][44] These individual sheets, typically measuring around 15-20 cm in height, were pasted together end-to-end using natural adhesives like plant gums to form extended strips up to several meters long, which were accordion-folded into screenfold formats for readability from both sides.[14][3] To prepare the surface for pictographic application, makers applied a thin layer of gesso—a white priming mixture of chalk, gypsum, or lime bound with animal glue or plant starch—over both obverse and reverse sides, creating a durable, absorbent base that enhanced pigment adhesion and prevented ink bleeding.[4] Pigments were sourced from inorganic minerals (e.g., red ochre or cinnabar for reds, azurite or clay for blues), organic materials (e.g., charcoal for blacks, plant extracts for yellows), and insects (e.g., cochineal for vibrant reds), ground into fine powders and diluted with water or binders like tree sap before use.[45][46] Application techniques involved outlining symbols with fine lines, possibly using reed tips or early brush-like tools, then filling areas with layered washes or opaque paints for depth and symbolic emphasis, as evidenced in surviving pre-Columbian examples like the Codex Borgia.[47] Tools were rudimentary and locally sourced, including obsidian blades for trimming sheets, stone mortars for pigment grinding, and brushes fashioned from bundled animal hair, yucca fibers, or feathers, enabling precise control in rendering complex iconography without metal implements.[48] Alternative materials like deerskin vellum required curing, stretching, and scraping with bone or stone tools to achieve a paintable surface, though bark paper predominated for its availability and cultural precedence in Mesoamerican scribal traditions.[3]Physical Characteristics and Durability

Aztec codices generally featured a screenfold construction, comprising elongated strips of material folded accordion-style into multiple leaves, typically measuring 15–25 cm in height and extending several meters when unfolded. This format facilitated sequential reading by unfolding panels, with some examples bound between wooden covers for protection.[35][41] The predominant substrate was amate paper, produced by harvesting and processing the inner bark of trees like Ficus or Trema, which was soaked, beaten, and flattened into thin, flexible sheets. Alternative materials included deerskin parchment or maguey (agave) fiber, though amate prevailed due to its superior tensile strength and workability. Pages were coated with a thin layer of gypsum or lime plaster to create a smooth, absorbent surface for applying pigments derived from minerals, plants, and insects.[35][49][50] Amate's fibrous structure conferred greater durability than agave paper, resisting fragmentation under repeated folding and handling, yet codices remained inherently fragile organic artifacts vulnerable to fire, moisture, microbial decay, and insect infestation. Pre-Columbian survivorship is limited to fewer than two dozen examples, largely attributable to deliberate destruction during the 1521 Spanish conquest and exposure to tropical climates. Colonial-era codices faced similar threats, with preservation often dependent on dry storage or ecclesiastical safeguarding. Contemporary conservation employs climate-controlled repositories, pH-neutral repairs, and digitization to extend longevity against ongoing mechanical wear and environmental factors.[49][7]Writing and Pictography

Evolution of Pictographic Writing

The pictographic writing system used in Aztec codices originated in the Olmec civilization of Mesoamerica's Gulf Coast, where precursors to formal writing emerged over 3,000 years ago, around 1000 BCE, including glyphs representing a 20-day calendar cycle that combined pictographic and early glyphic elements to denote speech and concepts.[6][51] This foundational system spread eastward to the Maya lowlands and westward to central Mexico, evolving through regional adaptations in cultures such as the Zapotec and Mixtec, which produced hieroglyphic inscriptions on stone and early screenfold manuscripts.[6][52] In central Mexico, the tradition retained a predominantly pictographic character, serving as mnemonic devices rather than full phonetic scripts, with symbols rendered on perishable bark paper by specialized scribes or tlacuilos.[6] By the time of the Aztec (Mexica) empire's rise around 1325 CE, the system had standardized into an ideographic framework emphasizing visual representation over linguistic phonetics, incorporating logograms for objects and events, rebus principles for proper names (e.g., combining a "water" glyph with additional markers for phonetic hints), and conventionalized symbols for numerals like the xiquipilli denoting 8,000 units.[53] Unlike the Maya script, which integrated syllabic signs for broader phonetic encoding and achieved near-full decipherment, Aztec pictography remained limited in phonetic capacity, prioritizing concise outlines for oral elaboration in historical annals, tribute tallies, and divinatory almanacs.[6][53] This evolution reflected practical adaptations to imperial needs, such as recording conquests and calendars, with scribes producing hundreds of codices during the empire's peak from 1325 to 1521 CE.[54] Recent scholarly reassessments highlight the system's sophistication in conveying a multisensory cosmology, challenging earlier dismissals as primitive by demonstrating its capacity to encode abstract relationships through integrated painting and symbolism, distinct from alphabetic traditions.[55] Pre-Aztec influences persisted in regional variations, such as hill or ethnic group pictographs, but Aztec usage focused on narrative efficiency, evolving terser xiuhpohualli (yearly records) to track rulers and events without extensive textual elaboration.[56][6] The destruction of most pre-colonial examples limited direct continuity, yet surviving colonial-era codices reveal a resilient tradition adapted under Spanish oversight.[6]Key Pictographic Symbols and Their Meanings

Aztec pictographic writing employed a system of logograms, ideograms, and phonetic complements to convey concepts, often relying on the rebus principle where images represented sounds or syllables alongside direct pictorial meanings.[57] This approach allowed for efficient depiction of historical events, genealogies, and administrative records in codices such as the Codex Mendoza, where symbols combined semantic and phonetic elements to denote places, numbers, and actions.[58] Numerical symbols followed a vigesimal (base-20) system, with dots representing units from one to four, a horizontal bar signifying five, and combinations thereof for higher values up to nineteen; for instance, ten was shown as two bars, and fifteen as three bars.[59] A flag or banner denoted twenty ("cempoalli," one count), which could be stacked or multiplied for larger quantities, as seen in tribute tallies in the Codex Mendoza where sequences of flags indicated volumes of goods like mantles or cacao beans.[60] Place glyphs typically featured a mound or hill as a generic locative suffix, augmented by specific icons for phonetic or semantic content; for example, the glyph for Mazatlan combined a deer (mazatl) atop a hill with teeth (approximating -tlan, place of abundance) via rebus, denoting "place of deer."[57] Similarly, Tulancingo incorporated tule reeds with a human posterior glyph symbolizing foundation (-tzin), indicating "place of foundation among tules."[57] Deity representations used distinctive attributes for identification: Huitzilopochtli, the patron war god, was depicted with eagle elements symbolizing solar power and martial prowess, often linked to the eagle perched on a cactus in foundational myths.[61] Quetzalcoatl appeared as a feathered serpent, embodying renewal and fertility through shedding skin motifs, while feathers in general signified divine status, abundance, and warrior elite, as in elaborate headdresses with quetzal plumes.[61] Event symbols included a burning temple to signify conquest, paired with the defeated place's glyph, as in migration or tribute codices recording Aztec expansions.[56] Tribute lists employed bundled icons for commodities—such as stacked mantles for textiles or cacao pods for currency—quantified by numeral prefixes to detail annual obligations from subjugated cities.[60]| Symbol Type | Example | Meaning/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Numeral (1-4) | Dots | Units in vigesimal counting[59] |

| Numeral (5) | Bar | Base for additive system[59] |

| Numeral (20) | Flag | Multiplier for higher counts[59] |

| Place Suffix | Hill/Mound | Locative indicator[57] |

| Conquest | Burning Temple | Victory over city[56] |

Narrative and Historical Accounts

Aztec codices narrated historical events through sequential pictographic sequences that depicted migrations, successions of rulers, battles, and foundational myths, often aligned with the xiuhpohualli (year count) calendar to denote chronology. These visual accounts emphasized key figures like priests carrying divine bundles and glyphs for places or years, requiring oral explication by tlacuilos (painter-scribes) to convey full details.[12][24] The Codex Boturini, a 16th-century copy of a pre-conquest original, chronicles the Mexica migration from Aztlán starting in 1168 CE, illustrating approximately 200 years of wandering across central Mexico with stops at sites like Chicomoztoc and Culhuacan, guided by the god Tezcatlipoca and marked by events such as leadership changes and conflicts. The narrative unfolds in a tira (strip) format, progressing left to right across 21.5 meters of amate paper, culminating in the arrival at Tenochtitlan's site in 1325 CE where an eagle on a cactus was sighted.[12][24][62] Complementing this, the Codex Aubin extends the historical record from the migration era through the reigns of Mexica tlatoque (rulers) like Acamapichtli (founder, r. 1376–1395 CE) and Moctezuma II (r. 1502–1520 CE), documenting conquests, tribute systems, and the 1521 fall to Hernán Cortés, with 81 leaves combining pictographs and alphabetic Nahuatl text up to 1608 CE. This annalistic structure lists events by year, including omens preceding the Spanish arrival, preserving indigenous viewpoints on imperial expansion and catastrophe.[63][64] Such codices functioned to affirm dynastic legitimacy and communal identity, blending verifiable place names and dates with symbolic elements like speech scrolls for reported dialogues, though interpretations vary due to the loss of oral traditions post-conquest. Colonial-era productions like these often integrated European paper and binding while retaining core pictographic methods, offering primary indigenous counterpoints to Spanish chronicles that emphasize divine retribution over empirical sequences.[62][12]Religious and Ceremonial Content

Aztec codices extensively document religious beliefs and ceremonial practices through pictographic representations of deities, ritual calendars, and sacrificial rites, reflecting the centrality of religion in maintaining cosmic order. Pre-conquest ritual almanacs, such as the Codex Borbonicus, dedicate their initial sections to the tonalpohualli, a 260-day divinatory calendar divided into 20 trecenas of 13 days each, with each period presided over by a specific deity like Chalchiuhtlicue or Xiuhtecuhtli, accompanied by illustrations of associated gods, omens, and ritual actions including offerings and autosacrifice.[65] These depictions guided priests in timing ceremonies to avert misfortune and ensure agricultural fertility.[66] Post-conquest codices like the Florentine Codex provide detailed accounts of the 18 monthly festivals (veintenas) plus the five barren days (nemontemi), each tied to particular gods and rituals. Book 2 of the Florentine Codex describes ceremonies such as Toxcatl, honoring Tezcatlipoca with the selection and sacrifice of a captive impersonator (ixiptla) whose heart was extracted atop the Templo Mayor to symbolize divine renewal.[67] These texts include prayers, songs, priestly duties, and communal feasts, emphasizing bloodletting and human sacrifice as mechanisms to nourish gods like Huitzilopochtli, whose rituals involved flaying victims and ritual cannibalism in specific contexts.[68] Similarly, Book 1 catalogs gods' attributes, origins, and worship, portraying entities such as Quetzalcoatl with serpentine forms and ritual implements.[69] Sacrificial imagery recurs across codices, showing priests wielding obsidian knives for heart extraction, with blood symbolizing life force offered to sustain the sun's movement and prevent universal collapse, as per Mesoamerican cosmology shared among Nahua peoples.[70] Codices like the Codex Borgia illustrate deity impersonations and processions, underscoring ceremonies' role in political and economic cycles, such as dry-season rituals linked to Tezcatlipoca.[71] These pictorial records, verified through archaeological correlates like skull racks at Tenochtitlan, affirm the scale and religious imperative of such practices, countering interpretive downplays by integrating textual and material evidence.[72]Style and Regional Schools

Regional Variations in Style

Aztec codices, produced across the diverse city-states of the Valley of Mexico and beyond, exhibit stylistic variations tied to local political centers, such as Tenochtitlan (Mexica/Tenochca) and Texcoco (Acolhua/Texcocan), reflecting distinct scribal traditions within Nahua culture.[73] These differences manifest in composition, figural depiction, and emphasis on content, with Tenochca codices favoring linear, sequential narratives of imperial conquests and tribute, characterized by bold outlines, standardized human forms in profile, and repetitive motifs for provinces and goods, as seen in the Codex Mendoza's structured folios detailing 1428–1541 conquests and annual tribute quotas from over 370 towns. In contrast, Texcocan manuscripts like the Codex Xolotl employ more cartographic integration, embedding glyphs for settlements and rulers within landscape representations to trace Acolhua genealogies from the 13th to 16th centuries, with finer line work and emphasis on territorial claims over ritual or military exploits.[73] Further variations appear in eastern peripheral regions influenced by the Mixteca-Puebla tradition, such as the Borgia Group codices (e.g., Codex Borbonicus, dated circa 1500–1521), which prioritize esoteric ritual calendars and deity processions in a denser, more abstract iconographic style with swirling motifs, layered symbolism, and less narrative linearity compared to central Valley historical accounts.[11] This regional divergence stems from the incorporation of pre-Aztec Postclassic styles from Puebla-Tlaxcala areas, where codices feature heightened complexity in astronomical and divinatory elements, using up to 20 pages of screenfold format for cyclical tonalpohualli (260-day) reckonings, differing from the Mendoza's pragmatic, grid-like tribute inventories.[47] Scholarly analysis identifies these as evidence of localized scribal schools under the Triple Alliance (1428–1521), where Texcoco's poetic and administrative focus yielded hybrid map-genealogies, while Tenochtitlan's imperial propaganda emphasized uniformity in figure scale and color palettes dominated by red and black inks derived from cochineal and carbon.[73] ![Nezahualcoyotl Palace from Codex Quinatzin][float-right]Such stylistic distinctions also extend to pigment application and border treatments; central codices often use broad, unframed panels for readability in public recitations, whereas peripheral examples incorporate framed vignettes and mineral-based blues (from indigo or azurite) for ritual potency, highlighting adaptations to local resources and patronage—e.g., Texcocan rulers like Nezahualcoyotl (r. 1429–1472) commissioning works blending Acolhua heritage with Mexica motifs.[47] These variations underscore the empire's decentralized artistic production, where altepetl (city-state) tlacuiloque (scribes) maintained autonomy in expression despite shared pictographic conventions, as evidenced by comparative studies of surviving fragments from Humboldt's 1803–1804 Mexican collections showing localized figural proportions and glyph orientations.[10]