Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boiling point

View on Wikipedia

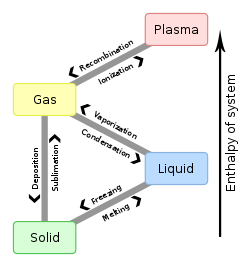

The boiling point of a substance is the temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid equals the pressure surrounding the liquid[1][2] and the liquid changes into a vapor.

The boiling point of a liquid varies depending upon the surrounding environmental pressure. A liquid in a partial vacuum, i.e., under a lower pressure, has a lower boiling point than when that liquid is at atmospheric pressure. Because of this, water boils at 100°C (or with scientific precision: 99.97 °C (211.95 °F)) under standard pressure at sea level, but at 93.4 °C (200.1 °F) at 1,905 metres (6,250 ft)[3] altitude. For a given pressure, different liquids will boil at different temperatures.

The normal boiling point (also called the atmospheric boiling point or the atmospheric pressure boiling point) of a liquid is the special case in which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the defined atmospheric pressure at sea level, one atmosphere.[4][5] At that temperature, the vapor pressure of the liquid becomes sufficient to overcome atmospheric pressure and allow bubbles of vapor to form inside the bulk of the liquid. The standard boiling point has been defined by IUPAC since 1982 as the temperature at which boiling occurs under a pressure of one bar.[6]

The heat of vaporization is the energy required to transform a given quantity (a mol, kg, pound, etc.) of a substance from a liquid into a gas at a given pressure (often atmospheric pressure).

Liquids may change to a vapor at temperatures below their boiling points through the process of evaporation. Evaporation is a surface phenomenon in which molecules located near the liquid's edge, not contained by enough liquid pressure on that side, escape into the surroundings as vapor. On the other hand, boiling is a process in which molecules anywhere in the liquid escape, resulting in the formation of vapor bubbles within the liquid.

Saturation temperature and pressure

[edit]A saturated liquid contains as much thermal energy as it can without boiling (or conversely a saturated vapor contains as little thermal energy as it can without condensing).

Saturation temperature means boiling point. The saturation temperature is the temperature for a corresponding saturation pressure at which a liquid boils into its vapor phase. The liquid can be said to be saturated with thermal energy. Any addition of thermal energy results in a phase transition.

If the pressure in a system remains constant (isobaric), a vapor at saturation temperature will begin to condense into its liquid phase as thermal energy (heat) is removed. Similarly, a liquid at saturation temperature and pressure will boil into its vapor phase as additional thermal energy is applied.

The boiling point corresponds to the temperature at which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the surrounding environmental pressure. Thus, the boiling point is dependent on the pressure. Boiling points may be published with respect to the NIST, USA standard pressure of 101.325 kPa (1 atm), or the IUPAC standard pressure of 100.000 kPa (1 bar). At higher elevations, where the atmospheric pressure is much lower, the boiling point is also lower. The boiling point increases with increased pressure up to the critical point, where the gas and liquid properties become identical. The boiling point cannot be increased beyond the critical point. Likewise, the boiling point decreases with decreasing pressure until the triple point is reached. The boiling point cannot be reduced below the triple point.

If the heat of vaporization and the vapor pressure of a liquid at a certain temperature are known, the boiling point can be calculated by using the Clausius–Clapeyron equation, thus:

where:

- is the boiling point at the pressure of interest,

- is the ideal gas constant,

- is the vapor pressure of the liquid,

- is some pressure where the corresponding is known (usually data available at 1 atm or 100 kPa (1 bar)),

- is the heat of vaporization of the liquid,

- is the boiling temperature,

- is the natural logarithm.

Saturation pressure is the pressure for a corresponding saturation temperature at which a liquid boils into its vapor phase. Saturation pressure and saturation temperature have a direct relationship: as saturation pressure is increased, so is saturation temperature.

If the temperature in a system remains constant (an isothermal system), vapor at saturation pressure and temperature will begin to condense into its liquid phase as the system pressure is increased. Similarly, a liquid at saturation pressure and temperature will tend to flash into its vapor phase as system pressure is decreased.

There are two conventions regarding the standard boiling point of water: The normal boiling point is commonly given as 100 °C (212 °F) (actually 99.97 °C (211.9 °F) following the thermodynamic definition of the Celsius scale based on the kelvin) at a pressure of 1 atm (101.325 kPa). The IUPAC-recommended standard boiling point of water at a standard pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar)[7] is 99.61 °C (211.3 °F).[6][8] For comparison, on top of Mount Everest, at 8,848 m (29,029 ft) elevation, the pressure is about 34 kPa (255 Torr)[9] and the boiling point of water is 71 °C (160 °F).[10] The Celsius temperature scale was defined until 1954 by two points: 0 °C being defined by the water freezing point and 100 °C being defined by the water boiling point at standard atmospheric pressure.

Relation between the normal boiling point and the vapor pressure of liquids

[edit]

The higher the vapor pressure of a liquid at a given temperature, the lower the normal boiling point (i.e., the boiling point at atmospheric pressure) of the liquid.

The vapor pressure chart to the right has graphs of the vapor pressures versus temperatures for a variety of liquids.[11] As can be seen in the chart, the liquids with the highest vapor pressures have the lowest normal boiling points.

For example, at any given temperature, methyl chloride has the highest vapor pressure of any of the liquids in the chart. It also has the lowest normal boiling point (−24.2 °C), which is where the vapor pressure curve of methyl chloride (the blue line) intersects the horizontal pressure line of one atmosphere (atm) of absolute vapor pressure.

The critical point of a liquid is the highest temperature (and pressure) it will actually boil at.

See also Vapour pressure of water.

Boiling point of chemical elements

[edit]The element with the lowest boiling point is helium. Both the boiling points of rhenium and tungsten exceed 5000 K at standard pressure; because it is difficult to measure extreme temperatures precisely without bias, both have been cited in the literature as having the higher boiling point.[12]

Boiling point as a reference property of a pure compound

[edit]As can be seen from the above plot of the logarithm of the vapor pressure vs. the temperature for any given pure chemical compound, its normal boiling point can serve as an indication of that compound's overall volatility. A given pure compound has only one normal boiling point, if any, and a compound's normal boiling point and melting point can serve as characteristic physical properties for that compound, listed in reference books. The higher a compound's normal boiling point, the less volatile that compound is overall, and conversely, the lower a compound's normal boiling point, the more volatile that compound is overall. Some compounds decompose at higher temperatures before reaching their normal boiling point, or sometimes even their melting point. For a stable compound, the boiling point ranges from its triple point to its critical point, depending on the external pressure. Beyond its triple point, a compound's normal boiling point, if any, is higher than its melting point. Beyond the critical point, a compound's liquid and vapor phases merge into one phase, which may be called a superheated gas. At any given temperature, if a compound's normal boiling point is lower, then that compound will generally exist as a gas at atmospheric external pressure. If the compound's normal boiling point is higher, then that compound can exist as a liquid or solid at that given temperature at atmospheric external pressure, and will so exist in equilibrium with its vapor (if volatile) if its vapors are contained. If a compound's vapors are not contained, then some volatile compounds can eventually evaporate away in spite of their higher boiling points.

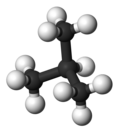

In general, compounds with ionic bonds have high normal boiling points, if they do not decompose before reaching such high temperatures. Many metals have high boiling points, but not all. Very generally—with other factors being equal—in compounds with covalently bonded molecules, as the size of the molecule (or molecular mass) increases, the normal boiling point increases. When the molecular size becomes that of a macromolecule, polymer, or otherwise very large, the compound often decomposes at high temperature before the boiling point is reached. Another factor that affects the normal boiling point of a compound is the polarity of its molecules. As the polarity of a compound's molecules increases, its normal boiling point increases, other factors being equal. Closely related is the ability of a molecule to form hydrogen bonds (in the liquid state), which makes it harder for molecules to leave the liquid state and thus increases the normal boiling point of the compound. Simple carboxylic acids dimerize by forming hydrogen bonds between molecules. A minor factor affecting boiling points is the shape of a molecule. Making the shape of a molecule more compact tends to lower the normal boiling point slightly compared to an equivalent molecule with more surface area.

| Common name | n-butane | isobutane |

|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name | butane | 2-methylpropane |

| Molecular form |

|

|

| Boiling point (°C) |

−0.5 | −11.7 |

| Common name | n-pentane | isopentane | neopentane |

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name | pentane | 2-methylbutane | 2,2-dimethylpropane |

| Molecular form |

|

|

|

| Boiling point (°C) |

36.0 | 27.7 | 9.5 |

Most volatile compounds (anywhere near ambient temperatures) go through an intermediate liquid phase while warming up from a solid phase to eventually transform to a vapor phase. By comparison to boiling, a sublimation is a physical transformation in which a solid turns directly into vapor, which happens in a few select cases such as with carbon dioxide at atmospheric pressure. For such compounds, a sublimation point is a temperature at which a solid turning directly into vapor has a vapor pressure equal to the external pressure.

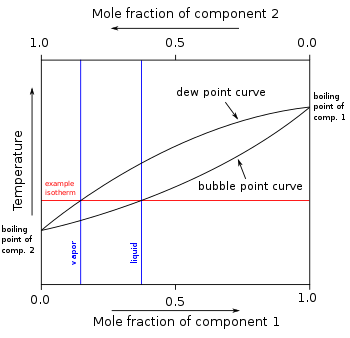

Impurities and mixtures

[edit]In the preceding section, boiling points of pure compounds were covered. Vapor pressures and boiling points of substances can be affected by the presence of dissolved impurities (solutes) or other miscible compounds, the degree of effect depending on the concentration of the impurities or other compounds. The presence of non-volatile impurities such as salts or compounds of a volatility far lower than the main component compound decreases its mole fraction and the solution's volatility, and thus raises the normal boiling point in proportion to the concentration of the solutes. This effect is called boiling point elevation. As a common example, salt water boils at a higher temperature than pure water.

In other mixtures of miscible compounds (components), there may be two or more components of varying volatility, each having its own pure component boiling point at any given pressure. The presence of other volatile components in a mixture affects the vapor pressures and thus boiling points and dew points of all the components in the mixture. The dew point is a temperature at which a vapor condenses into a liquid. Furthermore, at any given temperature, the composition of the vapor is different from the composition of the liquid in most such cases. In order to illustrate these effects between the volatile components in a mixture, a boiling point diagram is commonly used. Distillation is a process of boiling and [usually] condensation which takes advantage of these differences in composition between liquid and vapor phases.

Boiling point of water with elevation

[edit]Following is a table of the change in the boiling point of water with elevation, at intervals of 500 meters over the range of human habitation [the Dead Sea at −430.5 metres (−1,412 ft) to La Rinconada, Peru at 5,100 m (16,700 ft)], then of 1,000 meters over the additional range of uninhabited surface elevation [up to Mount Everest at 8,849 metres (29,032 ft)], along with a similar range in Imperial.

| Elevation (m) |

Boiling point (°C) |

Elevation (ft) |

Boiling point (°F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −500 | 101.6 | −1,500 | 214.7 | |

| 0 | 100.0 | 0 | 212.0 | |

| 500 | 98.4 | 1,500 | 209.3 | |

| 1,000 | 96.7 | 3,000 | 206.6 | |

| 1,500 | 95.1 | 4,500 | 203.9 | |

| 2,000 | 93.4 | 6,000 | 201.1 | |

| 2,500 | 91.7 | 7,500 | 198.3 | |

| 3,000 | 90.0 | 9,000 | 195.5 | |

| 3,500 | 88.2 | 10,500 | 192.6 | |

| 4,000 | 86.4 | 12,000 | 189.8 | |

| 4,500 | 84.6 | 13,500 | 186.8 | |

| 5,000 | 82.8 | 15,000 | 183.9 | |

| 6,000 | 79.1 | 16,500 | 180.9 | |

| 7,000 | 75.3 | 20,000 | 173.8 | |

| 8,000 | 71.4 | 23,000 | 167.5 | |

| 9,000 | 67.4 | 26,000 | 161.1 | |

| 29,000 | 154.6 |

Element table

[edit]| Group → | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ Period | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | H2 20.271 K (−252.879 °C) |

He4.222 K (−268.928 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li1603 K (1330 °C) |

Be2742 K (2469 °C) |

B 4200 K (3927 °C) |

C 3915 K (subl.) (3642 °C) |

N2 77.355 K (−195.795 °C) |

O2 90.188 K (−182.962 °C) |

F2 85.03 K (−188.11 °C) |

Ne27.104 K (−246.046 °C) | |||||||||||||

| 3 | Na1156.090 K (882.940 °C) |

Mg1363 K (1091 °C) |

Al2743 K (2470 °C) |

Si3538 K (3265 °C) |

P 553.7 K (280.5 °C) |

S 717.8 K (444.6 °C) |

Cl2239.11 K (−34.04 °C) |

Ar87.302 K (−185.848 °C) | |||||||||||||

| 4 | K 1032 K (759 °C) |

Ca1757 K (1484 °C) |

Sc3109 K (2836 °C) |

Ti3560 K (3287 °C) |

V 3680 K (3407 °C) |

Cr2945.15 K (2672.0 °C) |

Mn2334 K (2061 °C) |

Fe3134 K (2861 °C) |

Co3200 K (2927 °C) |

Ni3003 K (2730 °C) |

Cu2835 K (2562 °C) |

Zn1180 K (907 °C) |

Ga2673 K (2400 °C) |

Ge3106 K (2833 °C) |

As887 K (subl.) (615 °C) |

Se958 K (685 °C) |

Br2332.0 K (58.8 °C) |

Kr119.735 K (−153.415 °C) | |||

| 5 | Rb961 K (688 °C) |

Sr1650 K (1377 °C) |

Y 3203 K (2930 °C) |

Zr4650 K (4377 °C) |

Nb5017 K (4744 °C) |

Mo4912 K (4639 °C) |

Tc4538 K (4265 °C) |

Ru4423 K (4150 °C) |

Rh3968 K (3695 °C) |

Pd3236 K (2963 °C) |

Ag2483 K (2210 °C) |

Cd1040 K (767 °C) |

In2345 K (2072 °C) |

Sn2875 K (2602 °C) |

Sb1908 K (1635 °C) |

Te1261 K (988 °C) |

I2 457.4 K (184.3 °C) |

Xe165.051 K (−108.099 °C) | |||

| 6 | Cs944 K (671 °C) |

Ba2118 K (1845 °C) |

Lu3675 K (3402 °C) |

Hf4876 K (4603 °C) |

Ta5731 K (5458 °C) |

W 6203 K (5930 °C) |

Re5900.15 K (5627.0 °C) |

Os5285 K (5012 °C) |

Ir4403 K (4130 °C) |

Pt4098 K (3825 °C) |

Au3243 K (2970 °C) |

Hg629.88 K (356.73 °C) |

Tl1746 K (1473 °C) |

Pb2022 K (1749 °C) |

Bi1837 K (1564 °C) |

Po1235 K (962 °C) |

At2503±3 K (230±3 °C) |

Rn211.5 K (−61.7 °C) | |||

| 7 | Fr950 K (677 °C) |

Ra2010 K (1737 °C) |

Lr | Rf5800 K (5500 °C) |

Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn340±10 K (67±10 °C) |

Nh1430 K (1130 °C) |

Fl380 K (107 °C) |

Mc~1400 K (~1100 °C) |

Lv1035–1135 K (762–862 °C) |

Ts883 K (610 °C) |

Og450±10 K (177±10 °C) | |||

| La3737 K (3464 °C) |

Ce3716 K (3443 °C) |

Pr3403 K (3130 °C) |

Nd3347 K (3074 °C) |

Pm3273 K (3000 °C) |

Sm2173 K (1900 °C) |

Eu1802 K (1529 °C) |

Gd3546 K (3273 °C) |

Tb3396 K (3123 °C) |

Dy2840 K (2567 °C) |

Ho2873 K (2600 °C) |

Er3141 K (2868 °C) |

Tm2223 K (1950 °C) |

Yb1469 K (1196 °C) | ||||||||

| Ac3471 K (3198 °C) |

Th5061 K (4788 °C) |

Pa4300? K (4027 °C) |

U 4404 K (4131 °C) |

Np4175.15 K (3902.0 °C) |

Pu3508.15 K (3235.0 °C) |

Am2880 K (2607 °C) |

Cm3383 K (3110 °C) |

Bk2900 K (2627 °C) |

Cf1743 K (1470 °C) |

Es1269 K (996 °C) |

Fm | Md | No | ||||||||

| Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Values are in kelvin K and degrees Celsius °C, rounded | |||||||||||||||||||||

| For the equivalent in degrees Fahrenheit °F, see: Boiling points of the elements (data page) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Some values are predictions | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

Primordial From decay Synthetic Border shows natural occurrence of the element | |||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Boiling points of the elements (data page)

- Boiling-point elevation

- Critical point (thermodynamics)

- Ebulliometer, a device to accurately measure the boiling point of liquids

- Hagedorn temperature

- Joback method (Estimation of normal boiling points from molecular structure)

- List of gases including boiling points

- Melting point

- Subcooling

- Superheating

- Trouton's constant relating latent heat to boiling point

- Triple point

References

[edit]- ^ Goldberg, David E. (1988). 3,000 Solved Problems in Chemistry (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill. section 17.43, p. 321. ISBN 0-07-023684-4.

- ^ Theodore, Louis; Dupont, R. Ryan; Ganesan, Kumar, eds. (1999). Pollution Prevention: The Waste Management Approach to the 21st Century. CRC Press. section 27, p. 15. ISBN 1-56670-495-2.

- ^ "Boiling Point of Water and Altitude". www.engineeringtoolbox.com.

- ^ General Chemistry Glossary Purdue University website page

- ^ Reel, Kevin R.; Fikar, R. M.; Dumas, P. E.; Templin, Jay M. & Van Arnum, Patricia (2006). AP Chemistry (REA) – The Best Test Prep for the Advanced Placement Exam (9th ed.). Research & Education Association. section 71, p. 224. ISBN 0-7386-0221-3.

- ^ a b Cox, J. D. (1982). "Notation for states and processes, significance of the word standard in chemical thermodynamics, and remarks on commonly tabulated forms of thermodynamic functions". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 54 (6): 1239–1250. doi:10.1351/pac198254061239.

- ^ Standard Pressure IUPAC defines the "standard pressure" as being 105 Pa (which amounts to 1 bar).

- ^ Appendix 1: Property Tables and Charts (SI Units), Scroll down to Table A-5 and read the temperature value of 99.61 °C at a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar). Obtained from McGraw-Hill's Higher Education website.

- ^ West, J. B. (1999). "Barometric pressures on Mt. Everest: New data and physiological significance". Journal of Applied Physiology. 86 (3): 1062–6. doi:10.1152/jappl.1999.86.3.1062. PMID 10066724. S2CID 27875962.

- ^ "11.12: Boiling". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2022-08-26. Retrieved 2025-02-15.

- ^ Perry, R.H.; Green, D.W., eds. (1997). Perry's Chemical Engineers' Handbook (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-049841-5.

- ^ DeVoe, Howard (2000). Thermodynamics and Chemistry (1st ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-02-328741-1.

External links

[edit]- . . 1914.

Boiling point

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Boiling

Definition and Process

The boiling point of a liquid is the temperature at which the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the surrounding pressure, typically atmospheric pressure at standard conditions, leading to a phase transition from liquid to vapor throughout the bulk of the liquid. This equilibrium condition allows vapor bubbles to form, grow, and detach from nucleation sites—such as microscopic crevices on the heating surface, impurities, or gas pockets trapped within the liquid—initiating the boiling process.[5] Once nucleated, these bubbles expand due to the heat input, rise through the liquid due to buoyancy, and release vapor at the surface, facilitating efficient heat transfer.[6] Boiling differs fundamentally from evaporation, as the latter is a slower, surface-limited process where individual molecules gain sufficient kinetic energy to escape the liquid-air interface without bubble formation, occurring at temperatures below the boiling point.[7] In contrast, boiling involves vigorous bubble generation and detachment across the liquid volume, driven by the rapid phase change once the saturation temperature is reached.[8] The first systematic investigations into the influence of pressure on boiling emerged in the 17th century through experiments by Robert Boyle, who used an air pump to demonstrate that reducing atmospheric pressure lowers the boiling temperature of liquids like water.[9] Illustrations of the boiling process commonly depict vapor bubbles originating from nucleation sites at the bottom of a container, expanding as they ascend through the denser liquid, and rupturing at the free surface to emit steam, highlighting the dynamic convective currents induced by the rising bubbles.Saturation Temperature and Pressure

The saturation temperature, also known as the boiling point at a given pressure, is defined as the temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid equals the pressure of the surrounding system, allowing the liquid and vapor phases to exist in thermodynamic equilibrium.[10] At this point, the liquid can vaporize without further temperature increase, as the rates of evaporation and condensation balance.[11] This equilibrium condition is fundamental to phase changes and is observed across various substances under controlled pressures.[12] The boiling point of a liquid varies inversely with external pressure: higher pressures elevate the saturation temperature by requiring greater molecular energy to overcome the increased resistance to vapor formation, while lower pressures reduce it.[13] For example, pressure cookers exploit this principle by sealing in steam to build internal pressure, thereby raising the saturation temperature and enabling faster cooking at higher temperatures.[14] In contrast, at high altitudes where atmospheric pressure drops, the saturation temperature decreases, prolonging cooking times; specifically, it falls by approximately 1°C for every 300 meters of elevation increase due to the reduced ambient pressure.[15] In a typical pressure-temperature phase diagram for a pure substance, the saturation line—also called the vapor-liquid equilibrium curve—separates the liquid and vapor regions, illustrating how saturation temperature changes with pressure along this boundary.[16] This curve begins at the triple point, the unique condition where solid, liquid, and vapor phases coexist in equilibrium, and ends at the critical point, beyond which distinct liquid and vapor phases merge into a supercritical fluid. The normal boiling point corresponds to the saturation temperature at standard atmospheric pressure of 1 atm.[12]Theoretical Relations

Normal Boiling Point

The normal boiling point of a liquid is defined as the temperature at which its vapor pressure equals 101.325 kPa (1 atm), the standard atmospheric pressure, allowing the liquid to transition to vapor throughout the bulk.[17] Note that since 1982, IUPAC has recommended the standard boiling point at 1 bar (100 kPa) for standard state conditions, which for water is approximately 99.61 °C, differing slightly from the normal boiling point. This condition, denoted as , represents the saturation temperature specifically at this benchmark pressure and serves as a fundamental reference for comparing the volatility of substances under standardized conditions.[17] The concept of the normal boiling point emerged in the 19th century as chemists and physicists sought consistent metrics for thermophysical properties, but it was formally standardized by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in the 20th century to ensure uniformity in scientific data reporting. This adoption, detailed in IUPAC recommendations from 1994, emphasized the use of 101.325 kPa to align with historical atmospheric pressure conventions while facilitating reproducible measurements in chemical thermodynamics. Prior to broader IUPAC codification, variations in pressure definitions had led to inconsistencies in reported values, prompting the need for this precise benchmark. Measurement of the normal boiling point typically involves ebulliometric or dynamic distillation techniques under controlled conditions to maintain exactly 101.325 kPa. In ebulliometry, the liquid is heated in a specialized apparatus like a Beckmann thermometer-equipped ebulliometer, where the steady-state reflux temperature is recorded as vapor recondenses, ensuring equilibrium at the target pressure. Distillation methods, such as those using a simple or fractional column apparatus, observe the plateau temperature during vaporization while barometric pressure is monitored and adjusted if necessary to match 1 atm. These approaches prioritize purity and pressure control to achieve accuracy within 0.5–1 K for most organic liquids. Values are conventionally reported in degrees Celsius (°C) or Kelvin (K), with the latter absolute scale preferred in thermodynamic calculations; for instance, the normal boiling point of water is 100 °C, equivalent to 373.15 K.[18] This unit choice reflects practical laboratory conventions, where °C aligns with historical scales, while K ensures additivity in equations without negative values.Vapor Pressure Connection

The boiling point of a liquid is defined as the temperature at which its vapor pressure equals the surrounding external pressure, marking the onset of boiling where the liquid and vapor phases are in equilibrium.[2] This equilibrium condition arises because the vapor pressure represents the pressure exerted by the escaping molecules, and when it matches the external pressure, bubbles of vapor can form throughout the liquid without restriction.[13] The normal boiling point specifically refers to this temperature when the external pressure is 1 atm (101.325 kPa), serving as a standard reference for comparing substances.[19] The temperature dependence of vapor pressure, which directly governs boiling behavior, is described by the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, derived from thermodynamic principles.[20] The equation takes the form: where and are vapor pressures at absolute temperatures and , is the enthalpy of vaporization, and is the gas constant.[21] This relation quantifies how vapor pressure increases exponentially with temperature, explaining why boiling points rise with increasing external pressure.[19] The derivation begins with the Clapeyron equation, , which relates the slope of the phase boundary in the pressure-temperature diagram to the enthalpy change and volume change across the phase transition.[20] For vaporization, and from the ideal gas law, assuming the liquid volume is negligible compared to the vapor volume.[21] Integrating this form, with the assumption of constant , yields the Clausius-Clapeyron equation.[20] This approximation holds reasonably well for many substances over moderate temperature ranges but may deviate at high pressures or near critical points where ideality fails.[19] In practice, the Clausius-Clapeyron equation enables predictions of boiling point shifts with pressure changes; for instance, it can estimate how the boiling point of water decreases at high altitudes due to lower atmospheric pressure.[21] For more accurate modeling over wider ranges, empirical correlations like the Antoine equation are often employed, given by: where is vapor pressure in mmHg, is temperature in °C, and , , are substance-specific constants fitted to experimental data.[22] This form provides a practical tool for engineering applications, such as distillation processes, by offering a simple way to interpolate vapor pressure curves without relying solely on theoretical assumptions.[23]Boiling Points of Pure Substances

Chemical Elements

The normal boiling points of chemical elements, defined as the temperature at which their vapor pressure reaches 1 atm (101.325 kPa), vary dramatically across the periodic table, from cryogenic temperatures for light gases to over 5000 °C for refractory metals.[24] These values serve as key physical properties for identifying elements and understanding their behavior in chemical processes. Boiling points exhibit distinct periodic trends influenced by bonding types and atomic structure. In groups of non-metals and metalloids, boiling points generally increase down the group due to larger atomic sizes leading to stronger van der Waals forces; for instance, noble gases show low values rising from helium at -268.9 °C to xenon at -108.1 °C.[25] Metallic elements display higher boiling points overall, with transition metals like tungsten reaching 5555 °C owing to robust delocalized metallic bonding involving d-electrons.[26] Anomalies occur, such as mercury's relatively low boiling point of 356.7 °C compared to neighboring transition metals, resulting from relativistic effects that contract the 6s orbital, reduce s-p orbital mixing, and weaken interatomic bonds.[27] Measuring boiling points for reactive or volatile elements poses significant challenges. Alkali metals, highly reactive with oxygen and moisture, require inert atmospheres like argon or nitrogen, often in sealed ampoules or gloveboxes to avoid oxidation during vaporization.[28] Cryogenic elements and gases, such as hydrogen or helium, demand specialized low-temperature setups like cryostats or dilution refrigerators to achieve and maintain sub-ambient conditions precisely, preventing contamination from atmospheric gases.[25] The table below provides a comprehensive list of normal boiling points for all 118 elements, compiled from authoritative references including the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Values are in °C; some for superheavy elements (atomic numbers 104–118) are theoretical estimates based on empirical trends and quantum calculations, as these elements have not been produced in sufficient quantities for direct measurement. For elements that sublime at 1 atm, the sublimation temperature is provided with a note.[26][25][29]| Atomic Number | Element | Symbol | Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hydrogen | H | -252.9 |

| 2 | Helium | He | -268.9 |

| 3 | Lithium | Li | 1342 |

| 4 | Beryllium | Be | 2470 |

| 5 | Boron | B | 3927 |

| 6 | Carbon | C | 3642 (sublimes) |

| 7 | Nitrogen | N | -195.8 |

| 8 | Oxygen | O | -183.0 |

| 9 | Fluorine | F | -188.1 |

| 10 | Neon | Ne | -246.1 |

| 11 | Sodium | Na | 883 |

| 12 | Magnesium | Mg | 1090 |

| 13 | Aluminum | Al | 2467 |

| 14 | Silicon | Si | 3265 |

| 15 | Phosphorus | P | 280 |

| 16 | Sulfur | S | 444.6 |

| 17 | Chlorine | Cl | -34.0 |

| 18 | Argon | Ar | -185.8 |

| 19 | Potassium | K | 759 |

| 20 | Calcium | Ca | 1484 |

| 21 | Scandium | Sc | 2836 |

| 22 | Titanium | Ti | 3287 |

| 23 | Vanadium | V | 3913 |

| 24 | Chromium | Cr | 2671 |

| 25 | Manganese | Mn | 2061 |

| 26 | Iron | Fe | 2862 |

| 27 | Cobalt | Co | 2927 |

| 28 | Nickel | Ni | 2913 |

| 29 | Copper | Cu | 2562 |

| 30 | Zinc | Zn | 907 |

| 31 | Gallium | Ga | 2204 |

| 32 | Germanium | Ge | 2830 |

| 33 | Arsenic | As | 614 (sublimes) |

| 34 | Selenium | Se | 685 |

| 35 | Bromine | Br | 59 |

| 36 | Krypton | Kr | -153.4 |

| 37 | Rubidium | Rb | 688 |

| 38 | Strontium | Sr | 1382 |

| 39 | Yttrium | Y | 3338 |

| 40 | Zirconium | Zr | 4409 |

| 41 | Niobium | Nb | 4742 |

| 42 | Molybdenum | Mo | 4639 |

| 43 | Technetium | Tc | 4538 |

| 44 | Ruthenium | Ru | 3900 |

| 45 | Rhodium | Rh | 3695 |

| 46 | Palladium | Pd | 2963 |

| 47 | Silver | Ag | 2162 |

| 48 | Cadmium | Cd | 767 |

| 49 | Indium | In | 2072 |

| 50 | Tin | Sn | 2602 |

| 51 | Antimony | Sb | 1587 |

| 52 | Tellurium | Te | 988 |

| 53 | Iodine | I | 184 |

| 54 | Xenon | Xe | -108.1 |

| 55 | Cesium | Cs | 671 |

| 56 | Barium | Ba | 1897 |

| 57 | Lanthanum | La | 3464 |

| 58 | Cerium | Ce | 3443 |

| 59 | Praseodymium | Pr | 3520 |

| 60 | Neodymium | Nd | 3074 |

| 61 | Promethium | Pm | 3000 (est.) |

| 62 | Samarium | Sm | 2076 |

| 63 | Europium | Eu | 1597 |

| 64 | Gadolinium | Gd | 3273 |

| 65 | Terbium | Tb | 3232 |

| 66 | Dysprosium | Dy | 2567 |

| 67 | Holmium | Ho | 2700 |

| 68 | Erbium | Er | 2868 |

| 69 | Thulium | Tm | 2540 (est.) |

| 70 | Ytterbium | Yb | 1196 |

| 71 | Lutetium | Lu | 3402 |

| 72 | Hafnium | Hf | 4602 |

| 73 | Tantalum | Ta | 5458 |

| 74 | Tungsten | W | 5555 |

| 75 | Rhenium | Re | 5596 |

| 76 | Osmium | Os | 5012 |

| 77 | Iridium | Ir | 4130 |

| 78 | Platinum | Pt | 3825 |

| 79 | Gold | Au | 2856 |

| 80 | Mercury | Hg | 356.7 |

| 81 | Thallium | Tl | 1473 |

| 82 | Lead | Pb | 1749 |

| 83 | Bismuth | Bi | 1564 |

| 84 | Polonium | Po | 962 |

| 85 | Astatine | At | 337 (est.) |

| 86 | Radon | Rn | -62 |

| 87 | Francium | Fr | 677 (est.) |

| 88 | Radium | Ra | 1737 (est.) |

| 89 | Actinium | Ac | 3198 |

| 90 | Thorium | Th | 4788 |

| 91 | Protactinium | Pa | 4171 |

| 92 | Uranium | U | 4131 |

| 93 | Neptunium | Np | 4175 |

| 94 | Plutonium | Pu | 3228 |

| 95 | Americium | Am | 2607 |

| 96 | Curium | Cm | 3100 (est.) |

| 97 | Berkelium | Bk | 2597 (est.) |

| 98 | Californium | Cf | 1470 (est.) |

| 99 | Einsteinium | Es | 1087 (est.) |

| 100 | Fermium | Fm | ~1000 (est.) |

| 101 | Mendelevium | Md | ~1100 (est.) |

| 102 | Nobelium | No | ~1800 (est.) |

| 103 | Lawrencium | Lr | ~1630 (est.) |

| 104 | Rutherfordium | Rf | ~2100 (est.) |

| 105 | Dubnium | Db | ~2200 (est.) |

| 106 | Seaborgium | Sg | ~2200 (est.) |

| 107 | Bohrium | Bh | ~2200 (est.) |

| 108 | Hassium | Hs | ~480 (est.) |

| 109 | Meitnerium | Mt | ~1800 (est.) |

| 110 | Darmstadtium | Ds | ~1500 (est.) |

| 111 | Roentgenium | Rg | ~1570 (est.) |

| 112 | Copernicium | Cn | 357 (est.) |

| 113 | Nihonium | Nh | ~1400 (est.) |

| 114 | Flerovium | Fl | 107 (est.) |

| 115 | Moscovium | Mc | ~1100 (est.) |

| 116 | Livermorium | Lv | 404 (est.) |

| 117 | Tennessine | Ts | 574 (est.) |

| 118 | Oganesson | Og | 177 (est.) |