Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Choco languages

View on Wikipedia| Chocoan | |

|---|---|

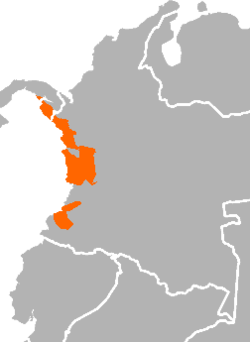

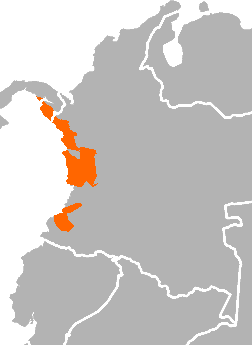

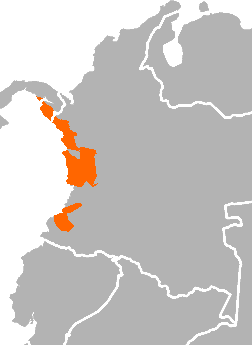

| Geographic distribution | Colombia and Panama |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | choc1280 |

| |

The Choco languages (also Chocoan, Chocó, Chokó) are a small family of Indigenous languages spread across Colombia and Panama.

Family division

[edit]Choco consists of six known branches, all but two of which are extinct.

- The Emberá languages (also known as Chocó proper, Cholo)

- Noanamá (also known as Waunana, Woun Meu)

- Sinúfana (Cenufara) † ?

- Anserma †

- Caramanta †

- ? Arma † (unattested)

At least Anserma, Arma, and Caramanta are extinct.

The Emberá group consists of two languages mainly in Colombia with over 60,000 speakers that lie within a fairly mutually intelligible dialect continuum. Ethnologue divides this into six languages. Kaufman (1994) considers the term Cholo to be vague and condescending. Noanamá has some 6,000 speakers on the Panama-Colombia border.

Jolkesky (2016)

[edit]Internal classification by Jolkesky (2016):[1]

- Choko

- Waunana

- Embera

- Southern

- Northern

Language contact

[edit]Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Guahibo, Kamsa, Paez, Tukano, Witoto-Okaina, Yaruro, Chibchan, and Bora-Muinane language families due to contact.[1]

Genetic links between Choco and Chibchan had been proposed by Lehmann (1920).[2] However, similarities are few, some of which may be related to the adoption of maize cultivation from neighbors.[1]: 324

Genetic relations

[edit]Choco has been included in a number of hypothetical phylum relationships:

- within Morris Swadesh's Macro-Leco

- Antonio Tovar, Jorge A. Suárez, and Robert Gunn: related to Cariban

- Čestmír Loukotka (1944): Southern Emberá may be related to Paezan, Noanamá to Arawakan

- within Paul Rivet and Loukotka's (1950) Cariban

- Constenla Umaña and Margery Peña: may be related to Chibchan

- within Joseph Greenberg's Nuclear Paezan, most closely related to Paezan and Barbacoan

- with Yaruro according to Pache (2016)[3]

Vocabulary

[edit]Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items for the Chocó languages.[4]

| gloss | Sambú | Chocó Pr. | Citara | Baudo | Waunana | Tadó | Saixa | Chamí | Ándagueda | Catio | Tukurá | N'Gvera |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| one | haba | abá | aba | aba | haba | aba | abbá | abba | abá | |||

| two | ome | ume | dáonomi | umé | homé | umé | ómay | tea | unmé | |||

| three | ompea | umpia | dáonatup | kimaris | hompé | umpea | ompayá | umbea | unpia | |||

| head | poro | poro | achiporo | púro | boró | tachi-púro | boró | bóro | buru | porú | ||

| eye | tau | tau | tabú | tau | dága | tau | tau | dáu | tow | dabu | tabú | tapü |

| tooth | kida | kida | kida | kidá | xidá | kidá | chida | chida | ||||

| man | amoxina | mukira | umakira | emokoida | mukira | mukína | mugira | mohuná | mukira | |||

| water | pañia | paniá | pania | pania | dó | pania | panía | banía | puneá | panea | pánia | |

| fire | tibua | tibuá | xemkavai | tupuk | tupu | tubechuá | tübü | |||||

| sun | pisia | pisiá | umantago | vesea | edau | vesea | áxonihino | umata | emwaiton | humandayo | ahumautu | |

| moon | edexo | édexo | hidexo | xedeko | xedego | edekoː | átoní | edexo | heydaho | xedeko | xedéko | hedeko |

| maize | pe | pe | paga | pedeu | pe | pe | bé | pe | ||||

| jaguar | imama | ibamá | ibamá | imama | kumá | pimamá | imama | imamá | imamá | |||

| arrow | enatruma | halomá | halomá | sia | chókiera | umatruma | sía | ukida | enentiera |

Proto-language

[edit]For reconstructions of Proto-Chocó and Proto-Emberá by Constenla and Margery (1991),[5] see the corresponding Spanish article.

See also

[edit]- Embera-Wounaan, who speak the Choco languages, Embera and Wounaan

- Quimbaya language

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho De Valhery. 2016. Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Brasília.

- ^ Lehmann, W. (1920). Zentral-Amerika. Teil I. Die Sprachen Zentral-Amerikas in ihren Beziehungen zueinander sowie zu Süd-Amerika und Mexico. Berlin: Reimer.

- ^ Pache, Matthias J. 2016. Pumé (Yaruro) and Chocoan: Evidence for a New Genealogical Link in Northern South America. Language Dynamics and Change 6 (2016) 99–155. doi:10.1163/22105832-00601001

- ^ Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center.

- ^ Constenla Umaña, Adolfo; Margery Peña, Enrique. (1991). Elementos de fonología comparada Chocó. Filología y lingüística, 17, 137-191.

Bibliography

[edit]- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

- Constenla Umaña, Adolfo; & Margery Peña, Enrique. (1991). Elementos de fonología comparada Chocó. Filología y lingüística, 17, 137-191.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1987). Language in the Americas. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Gunn, Robert D. (Ed.). (1980). Claificación de los idiomas indígenas de Panamá, con un vocabulario comparativo de los mismos. Lenguas de Panamá (No. 7). Panama: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1990). Language history in South America: What we know and how to know more. In D. L. Payne (Ed.), Amazonian linguistics: Studies in lowland South American languages (pp. 13–67). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70414-3.

- Kaufman, Terrence. (1994). The native languages of South America. In C. Mosley & R. E. Asher (Eds.), Atlas of the world's languages (pp. 46–76). London: Routledge.

- Loewen, Jacob. (1963). Choco I & Choco II. International Journal of American Linguistics, 29.

- Licht, Daniel Aguirre. (1999). Embera. Languages of the world/materials 208. LINCOM.

- Mortensen, Charles A. (1999). A reference grammar of the Northern Embera languages. Studies in the languages of Colombia (No.7); SIL publications in linguistics (No. 134). SIL.

- Pinto García, C. (1974/1978). Los indios katíos: su cultura - su lengua. Medellín: Editorial Gran-América.

- Rendón G., G. (2011). La lengua Umbra: Descubrimiento - Endolingüística - Arqueolingüística. Manizales: Zapata.

- Rivet, Paul; & Loukotka, Cestmír. (1950). Langues d'Amêrique du sud et des Antilles. In A. Meillet & M. Cohen (Eds.), Les langues du monde (Vol. 2). Paris: Champion.

- Sara, S. I. (2002). A tri-lingual dictionary of Emberá-English-Spanish. (Languages of the World/Dictionaries, 38). Munich: Lincom Europa.

- Suárez, Jorge. (1974). South American Indian languages. The new Encyclopædia Britannica (15th ed.). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Swadesh, Morris. (1959). Mapas de clasificación lingüística de México y las Américas. México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Tovar, Antonio; & Larrucea de Tovar, Consuelo. (1984). Catálogo de las lenguas de América del Sur (nueva ed.). Madrid: Editorial Gedos. ISBN 84-249-0957-7.

External links

[edit]- Proel: Familia Chocó

Choco languages

View on GrokipediaOverview

Geographic Distribution and Speakers

The Choco languages, belonging to the Chocoan family, are spoken by indigenous Emberá and Wounaan communities primarily in the humid Pacific lowlands of northwestern Colombia and southeastern Panama. These languages occupy a continuous territory stretching from the Colombian departments of Chocó, Antioquia, and Valle del Cauca to Panama's Darién and Panama provinces, where dense rainforests and river systems shape the speakers' semi-nomadic lifestyles. Limited extensions reach into Ecuador's Esmeraldas province, though such communities are small and often endangered.[2][6] The Emberá branch dominates in speaker numbers, comprising a dialect continuum with over 90,000 speakers as of 2020, the vast majority residing in Colombia along rivers like the San Juan and Atrato. For instance, Northern Emberá has approximately 20,000 speakers in Colombian Chocó and Antioquia, while Southern Emberá varieties extend into Panama's Darién region with around 22,000 speakers. The Wounaan branch (also called Woun Meu or Noanamá) accounts for about 11,500 speakers as of 2020, concentrated in border areas such as Colombia's lower Baudó River and Panama's Sambú district, where communities maintain traditional practices like basketry and fishing; most varieties are vulnerable or endangered.[6][7] Collectively, the Choco languages have approximately 103,500 speakers as of 2020, representing a vital part of the region's linguistic diversity despite pressures from Spanish dominance and environmental displacement. Most speakers are bilingual, with revitalization initiatives focusing on education and cultural documentation to sustain usage among younger generations.[6]Historical Context

The Chocoan language family, comprising Emberá and Wounaan branches, originated in the Pacific lowlands of western Colombia, with evidence suggesting an ancient distribution extending northward into Panama, possibly including the now-extinct Cueva language. Pre-colonial speakers inhabited diverse environments from coastal mangroves to inland rainforests, maintaining autonomous communities with limited external contacts until European arrival. The family's internal diversity indicates a long-standing presence in the region, though precise timelines for diversification remain uncertain due to the absence of written records.[2] European contact began in the early 16th century during the Spanish conquest of the Chocó region, driven by the pursuit of gold and other minerals. Chocoan-speaking groups, particularly the Emberá, mounted fierce resistance against Spanish incursions, leading to significant population displacements and migrations southward into Ecuador and northward into Panama as a means of evasion. A notable event occurred in 1637, when unified Emberá forces under a warrior chief expelled invaders, prompting a mass exodus into remote jungles and mountains; Spanish control was not fully consolidated until the late 18th century. These upheavals, compounded by enslavement and disease, resulted in substantial demographic declines and the loss of several Chocoan varieties.[8][2] Linguistic documentation of Chocoan languages emerged sporadically during the colonial era through Spanish chroniclers and missionaries, who compiled basic wordlists amid evangelization efforts, though these were often orthographically inconsistent and focused on practical communication. Systematic study commenced in the early 20th century with expeditions by scholars like Erland Nordenskiöld, who collected data on Emberá and related dialects during travels to Colombia and Panama in the 1920s. Post-colonial research intensified in the mid-20th century, with influential works establishing the family's genetic unity and exploring substrate influences on regional Spanish varieties from 16th- and 17th-century contacts. Contemporary documentation emphasizes community-led revitalization amid ongoing threats from deforestation and cultural assimilation.[9][10]Classification

Internal Divisions

The Chocoan language family, also known as Chocó, is internally divided into two primary living branches: Emberá and Wounaan (also spelled Waunana or Noanamá). These branches are distinguished based on comparative phonological and lexical evidence, with Emberá comprising a cluster of closely related varieties spoken primarily in western Colombia, eastern Panama, and northwestern Ecuador, while Wounaan is more uniform and concentrated in northern Colombia and eastern Panama.[11][12] The Emberá branch includes at least six recognized languages or dialect clusters, reflecting significant internal diversity driven by geographic separation along river systems in the Chocó region. Key varieties encompass Northern Emberá (spoken by communities in Panama and Colombia), Southern Emberá (with subgroups in southern Colombia and Ecuador), Embera Catío (primarily in Antioquia and Chocó departments of Colombia), Embera Chamí (in Risaralda and neighboring areas), Embera Tadó (in the Tadó region of Colombia), and Epena (or Saija Emberá, along the Saija River). This subgroup accounts for the majority of Chocoan speakers, estimated at approximately 92,000 individuals as of 2013, and exhibits shared innovations such as specific vowel harmony patterns reconstructed to Proto-Emberá.[6][12][11] In contrast, the Wounaan branch comprises three languages, with approximately 11,500 speakers as of 2013 mainly in the Baudó and San Juan river basins of Chocó department, Colombia, and smaller communities in Panama. It diverges from Emberá in core vocabulary and phonology, including distinct treatments of proto-Chocoan consonants, supporting its status as a coordinate branch rather than a dialect of Emberá.[6][12][11] Several extinct languages are associated with the family, potentially forming additional branches, though their precise affiliations remain tentative due to limited documentation. These include Cueva (spoken in eastern Panama until the 18th century and possibly a separate branch), Sinúfana (or Cenúfana, from the Sinú River valley in Colombia), and others like Anserma and Caramanta from historical records in the Cauca Valley. Such varieties highlight the family's historical extent but lack sufficient comparative data for firm subgrouping.[11]External Genetic Relations

The Chocoan languages form a small, independent language family spoken in northwestern South America, with no widely accepted genetic affiliations to other major language families. While typological similarities and lexical borrowings exist with neighboring groups such as Chibchan languages (e.g., Guna), these are generally attributed to prolonged areal contact rather than shared ancestry.[2] A notable 2016 proposal suggests a genealogical connection between Chocoan and the Pumé (also known as Yaruro) language of Venezuela, which had previously been classified as an isolate. This hypothesis is based on recurrent sound correspondences in basic vocabulary and morphology, with 51 cognate sets identified across the compared languages, including parallels in pronouns, body parts, and numerals. For instance, Pumé ba 'two' corresponds regularly to Chocoan forms like Emberá ba or Wounaan wa, supported by consistent phonological shifts such as vowel harmony and consonant lenition. The proposed link implies a time depth of several millennia and a potential trans-Andean dispersal, though it remains controversial and unconfirmed, with some recent analyses favoring alternative connections such as to Chibchan.[13][2]Languages

Emberá Branch

The Emberá branch constitutes the primary division of the Choco language family, encompassing a group of closely related languages spoken by indigenous communities along the Pacific coast. These languages are primarily distributed in northwestern Colombia, particularly in the departments of Chocó, Antioquia, and Córdoba, as well as in southeastern Panama's Darién region. The branch is characterized by a dialect continuum, where adjacent varieties exhibit high mutual intelligibility, though divergence increases with geographic separation. Collectively, the Emberá languages are spoken by over 100,000 people (as of 2017), making them the most vital component of the Choco family.[14] Within the Emberá branch, linguists recognize several distinct languages, often grouped into northern and southern subgroups based on phonological and lexical differences. The northern subgroup includes Northern Emberá (also known as Emberá-Darién or West Emberá), Emberá-Catío, and Emberá-Baudó, which are spoken mainly in Panama and the Colombian departments bordering it. The southern subgroup comprises Emberá-Chamí, Emberá-Tadó, and Epena (also called Southern Emberá or Emberá-Saija), concentrated in the inland areas of Colombia's Chocó region. This classification highlights isoglosses such as nasalization patterns and vocabulary for local flora and fauna, which delineate the subgroups while underscoring the branch's internal unity.[15][16] Linguistically, Emberá languages exhibit agglutinative morphology typical of the Choco family, with complex verb systems incorporating prefixes for person, number, and evidentiality, alongside derivational suffixes for aspect and causation. Noun phrases feature classifiers and possessives marked by juxtaposition or enclitics, while phonology often includes a five-vowel system with nasal variants and contrastive tone in some varieties. For instance, Northern Emberá and Emberá-Katío share syntactic structures like verb-final clauses and switch-reference marking in subordination, though southern varieties show innovations in consonant clusters. These features have been documented through fieldwork, revealing adaptations to the tropical rainforest environment, such as specialized terms for biodiversity and navigation.[17][18]Wounaan Branch

The Wounaan branch constitutes one of the two primary divisions of the Chocoan language family, alongside the Emberá branch.[2] It encompasses a single language, Wounaan (also known as Woun Meu, Noanamá, or Waunana), which is spoken by indigenous communities in the Pacific lowlands.[19] This branch is characterized by its ergative-absolutive alignment and close genetic relation to Emberá languages, forming a compact family centered in the densely forested regions west of the Colombian Andes.[2][20] Wounaan is primarily spoken by approximately 10,000 indigenous people (as of 2020), with communities distributed across the Darién region of eastern Panama and the Chocó Department in northwestern Colombia.[6] These speakers belong to the Wounaan ethnic group, who maintain semi-nomadic lifestyles tied to riverine environments, and the language serves as a key marker of cultural identity.[2] While considered stable in some assessments, with use as a first language predominant within ethnic communities, intergenerational transmission faces challenges, as younger speakers in urbanizing areas show reduced proficiency.[21][19] Linguistically, Wounaan exhibits a rigid subject-object-verb (SOV) word order and pro-drop properties, allowing omission of subject and object pronouns in context.[20] Case marking follows an ergative pattern, where the agent of transitive verbs is marked with suffixes like -o or -mua, while the patient and the single argument of intransitive verbs remain unmarked (absolutive).[20] Clause linking relies on asyndetic chaining for coordination, with overt conjunctions such as mamɘ ('but') and comitative dɨ for noun phrases; subordination employs suffixal strategies (e.g., -mɘn 'if', -baawai 'when') and nominalization (e.g., -tarr).[20] Valency is modulated through productive causatives like -pi and argument omission for reduction, reflecting agglutinative morphology with a preference for suffixes.[20] Documentation efforts include descriptive grammars and community-based projects, such as those by Murillo Miranda (2015) on phonology and syntax, and collaborative initiatives emphasizing speaker involvement.[20][22] Historical linguistic work suggests possible connections to extinct languages like Cueva in Panama, though these remain tentative.[2] Ongoing research highlights influences from neighboring Chibchan languages, particularly Guna, evident in lexical borrowings.[2]Extinct Languages

Several extinct languages have been tentatively classified within the Chocoan family, primarily based on limited lexical evidence from colonial-era records. These languages were spoken in the Pacific lowlands and Andean foothills of Colombia, with some possibly extending into Panama, and most became extinct by the 17th or 18th century due to European colonization, disease, and enslavement. Documentation is scarce, often consisting of short wordlists or place names, making precise classification challenging; however, similarities in vocabulary suggest affiliations with core Chocoan branches like Emberá or Wounaan. Key extinct Chocoan languages include:- Anserma (Anserna): Spoken in the Cauca Valley region of western Colombia, this language is known from a few dozen words recorded in the 16th century. It is considered extinct since the early colonial period, with lexical parallels to modern Emberá suggesting a close relation.

- Arma: Attested in the Cauca River basin of Colombia, Arma is documented through approximately 20-30 words from 16th- and 17th-century sources. The language ceased to be spoken by the late 18th century, and its vocabulary shows Chocoan features such as nasalized vowels and specific terms for local flora.

- Caramanta: Located in the Antioquia department of Colombia, this extinct language is evidenced by a small corpus of words and toponyms from the 16th century. It likely perished during the initial colonial conquests, with proposed links to the Emberá branch based on shared morphological elements.

- Cauca: Spoken along the Cauca River in southern Colombia, Cauca is known from fragmentary 16th-century vocabularies and is classified as Chocoan due to resemblances in basic lexicon (e.g., numerals and body parts). It became extinct by the mid-17th century.

- Cenu (or Cénu/Sinú): Associated with the Sinú River region in northern Colombia, Cenu is attested through colonial documents and a short wordlist. Extinct since the 17th century, it may represent a northern extension of Chocoan, with some terms overlapping with Emberá. Sinúfana (or Cenufana), possibly a dialect or closely related variety, shares this status and sparse attestation.

- Quimbaya (Kimbaya): From the Quimbaya culture area in central Colombia, this language survives in only about eight words recorded in the 16th century. It is extinct and tentatively linked to Chocoan through potential cognates in agriculture and kinship terms.

Reconstruction and Features

Proto-Choco Language

The Proto-Choco language, also known as Proto-Chocó, represents the reconstructed ancestral form of the Chocoan language family, spoken in northwestern South America. Reconstruction efforts have primarily focused on phonology and basic lexicon, drawing from comparative data across modern Chocoan languages, particularly the Emberá and Wounaan (Waunana) branches. The seminal work is Elementos de fonología comparada Chocó by Adolfo Constenla Umaña and Enrique Margery Peña (1991), which analyzes correspondences in four Emberá dialects (Saija, Chamí, Catío, and Sambú) alongside Waunana to establish sound regularities and proto-forms. This study provides 311 reconstructed lexical items, emphasizing nouns, verbs, and grammatical elements to trace family-internal evolution.[12] The phonological system of Proto-Chocó features a relatively simple inventory of consonants, reflecting a voiced-voiceless opposition in stops without the complex distinctions seen in some daughter languages. The reconstructed consonants include voiceless stops p, t, k; glottal stop ʔ; voiced stops b, d; nasals m, n; fricatives s, h; and approximants w, j, yielding a total of about 12 phonemes. Vowel reconstruction posits a basic five-vowel oral system (/i, e, a, o, u/), often with nasalized variants (ĩ, ẽ, ã, õ, ũ) that play a contrastive role, as evidenced by regular nasal harmony and spreading in descendant languages. Phonotactics favor open syllables (CV or CVC), with word-initial consonants common and no complex clusters. These features highlight Proto-Chocó's typological simplicity compared to the aspirated and glottalized stops that developed later in Emberá varieties. Lexical reconstructions illustrate core vocabulary and potential areal influences. For instance, wa denotes 'water', with reflexes varying across modern languages (e.g., bɨ́); ba means 'house', with forms like dʌ́; and ti reconstructs to 'hand'. Other examples include bua 'two' and pa 'one', supporting numeral systems shared across the family. These proto-forms, derived via the comparative method, reveal sound changes such as lenition of stops (e.g., *k > h in intervocalic positions) and vowel nasalization triggered by nearby nasals. While grammatical reconstruction remains limited, shared morphemes suggest agglutinative traits, including prefixes for person marking and suffixes for aspect, though full syntactic patterns await further comparative work.[12]Phonology and Grammar

The phonology of Chocoan languages is distinguished by a systematic contrast between oral and nasal vowels, a feature present across the family. Proto-Chocoan is reconstructed with a five-vowel oral system /i, e, a, o, u/ and corresponding nasal vowels /ĩ, ẽ, ã, õ, ũ/, though individual languages and dialects may show variation, such as mergers or additional distinctions in vowel height or rounding. Nasalization often spreads regressively from nasal consonants to preceding vowels, and vocalic nasality can be phonemically contrastive, as in Northern Emberá pairs like kʰo 'eat' (oral) versus kʰõ (nasal form in some contexts). Consonant inventories in Chocoan languages are relatively simple, typically comprising 15–20 phonemes, with a focus on stops, nasals, and fricatives. Common consonants include voiceless stops /p, t, k/, voiced stops /b, d, g/, nasals /m, n/, alveolar fricative /s/, glottal fricative /h/, trill or flap /r/, lateral /l/, and glides /w, j/. Dialects of the Emberá branch often feature aspirated stops /pʰ, tʰ, kʰ/ and glottal stops /ʔ/, while the Wounaan branch may include prenasalized stops like /ᵐb, ⁿd/ derived from nasal harmony. Syllable structure is predominantly (C)V(N), permitting onset consonants but restricting codas to nasals or glottal stops; complex onsets and coda clusters are rare, contributing to the languages' rhythmic flow. For example, in Emberá-Katío, voiced stops assimilate to homorganic nasals in nasal environments, yielding forms like /ᵐb/ from /b/ after a nasal vowel. Grammatically, Chocoan languages are agglutinative and head-marking, relying heavily on suffixation for inflection and derivation, with minimal prefixation. Nouns inflect for case, number (singular/plural via suffixes like -ra in Proto-Chocoan), and sometimes gender or classifiers in specific branches. The family exhibits ergative-absolutive alignment, particularly evident in nominal case marking: transitive subjects take an ergative suffix (e.g., -a or -e in Wounaan), while intransitive subjects and transitive objects remain unmarked (absolutive). This pattern holds in declarative clauses but may split toward nominative alignment in certain tenses or embedded contexts, as seen in Emberá-Katío verbal agreement.[20][23] Verbs are highly inflected, marking person (first, second, third), number, tense, aspect (e.g., completive -de, incompletive -a), mood, and evidentiality through ordered suffixes. Derivational morphology is productive, forming causatives (e.g., -ba 'cause to'), reciprocals (-uai), and nominalizations from verbal roots. Basic word order is verb-initial (VSO or VOS), though flexible due to discourse pragmatics, with postpositions governing oblique arguments. In Wounaan, valency changes are encoded via applicative suffixes like -uel 'benefactive', increasing transitivity while preserving ergative patterning.[17] Subordination employs nominalizing suffixes on verbs to form relative or complement clauses, integrating them as noun phrases. Overall, these features reflect a typological profile adapted to the multilingual contact zones of northwestern South America.[20]Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Choco languages, spoken primarily in the humid Pacific coastal regions of Colombia and Panama, encompasses terms reflecting the daily life, environment, and cultural practices of their speakers, including references to rivers, forests, agriculture, and fishing. Basic lexical items form the core for comparative linguistics within the family, enabling the identification of cognates and the partial reconstruction of Proto-Chocoan forms. Comparative studies rely on standardized word lists adapted from Swadesh-style inventories to capture shared heritage across the Emberá and Wounaan (Waunana) branches, where lexical similarity is estimated at around 50-70% for core vocabulary between closely related varieties.[24] A key resource for understanding Chocoan vocabulary is the comparative word list compiled by Harms (1989), which amplifies a modified Swadesh-Rowe list with items relevant to the family's cultural context, such as terms for tropical flora and fauna. This list documents forms from Northern Emberá, Southern Emberá, and Waunana, highlighting regular sound correspondences that support family unity. For instance, nouns and verbs often exhibit vowel harmony and nasalization patterns, with Proto-Chocoan reconstructions proposed for stable items like body parts and numerals based on these correspondences. Representative examples from the list illustrate the degree of retention and variation:| English Gloss | Northern Emberá | Southern Emberá | Waunana |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | sɨ́ | sɨ́ | sɨ́ |

| Moon | tʌ́ | tʌ́ | tʌ́ |

| Water | bɨ́ | bɨ́ | bɨ́ |

| Fire | kʌ́ | kʌ́ | kʌ́ |

| House | dʌ́ | dʌ́ | dʌ́ |

| One | pʌ́ | pʌ́ | pʌ́ |

| Two | kʌ́mɨ́ | kʌ́mɨ́ | kʌ́mɨ́ |

| Dog | wɨ́ | wɨ́ | wɨ́ |

| Fish | tʌ́mɨ́ | tʌ́mɨ́ | tʌ́mɨ́ |

| Tree | sʌ́ | sʌ́ | sʌ́ |