Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electric charge

View on Wikipedia| Electric charge | |

|---|---|

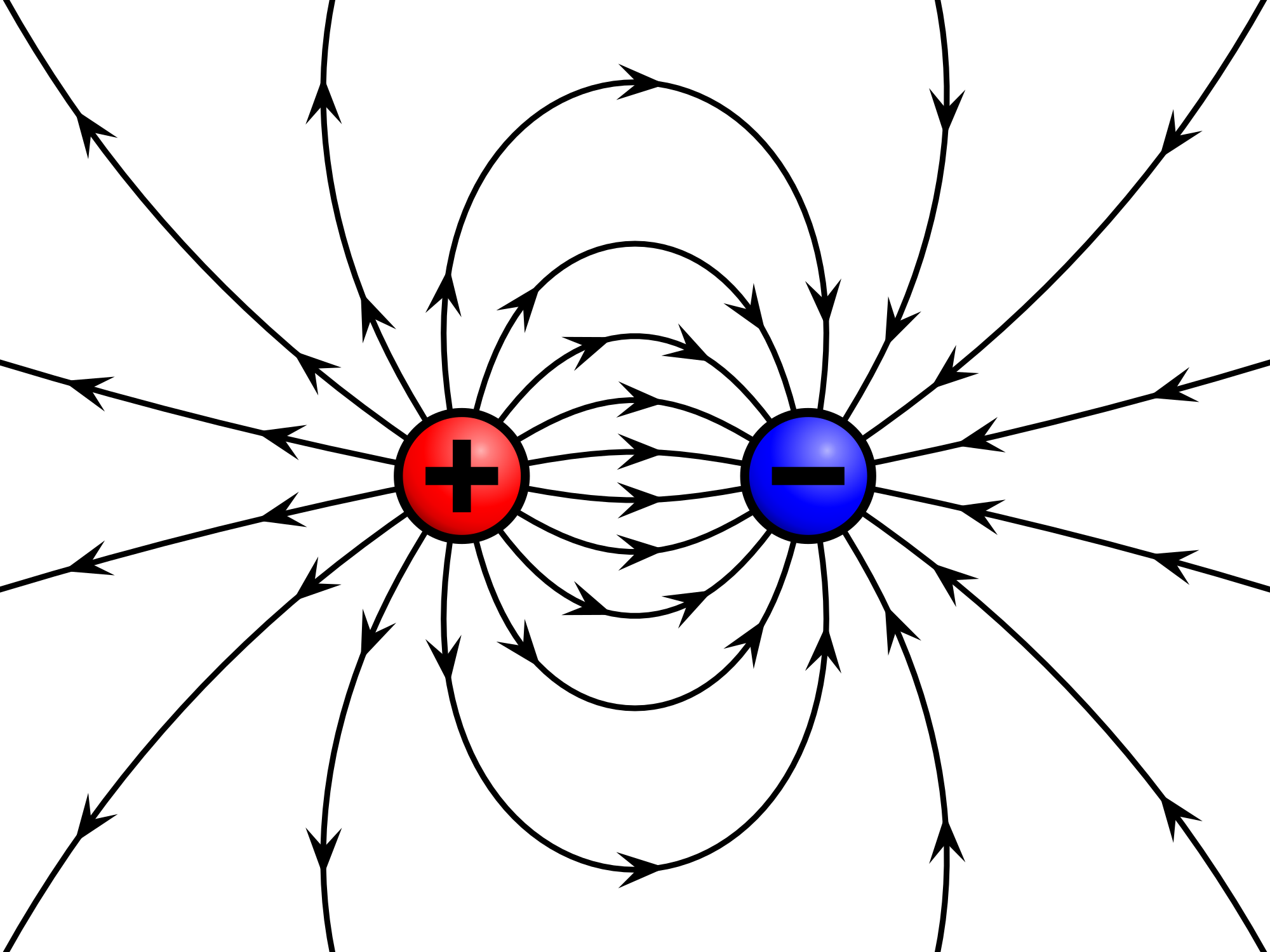

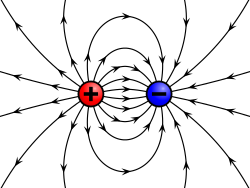

Electric field of a positive and a negative point charge | |

Common symbols | q |

| SI unit | coulomb (C) |

Other units | |

| In SI base units | A⋅s |

| Extensive? | yes |

| Conserved? | yes |

| Dimension | |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

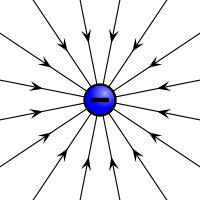

Electric charge (symbol q, sometimes Q) is a physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be positive or negative. Like charges repel each other and unlike charges attract each other. An object with no net charge is referred to as electrically neutral. Early knowledge of how charged substances interact is now called classical electrodynamics, and is still accurate for problems that do not require consideration of quantum effects.

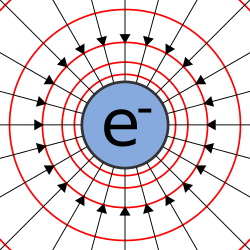

In an isolated system, the total charge stays the same - the amount of positive charge minus the amount of negative charge does not change over time. Electric charge is carried by subatomic particles. In ordinary matter, negative charge is carried by electrons, and positive charge is carried by the protons in the nuclei of atoms. If there are more electrons than protons in a piece of matter, it will have a negative charge, if there are fewer it will have a positive charge, and if there are equal numbers it will be neutral. Charge is quantized: it comes in integer multiples of individual small units called the elementary charge, e, about 1.602×10−19 C,[1] which is the smallest charge that can exist freely. Particles called quarks have smaller charges, multiples of 1/3e, but they are found only combined in particles that have a charge that is an integer multiple of e. In the Standard Model, charge is an absolutely conserved quantum number. The proton has a charge of +e, and the electron has a charge of −e.

Today, a negative charge is defined as the charge carried by an electron and a positive charge is that carried by a proton. Before these particles were discovered, a positive charge was defined by Benjamin Franklin as the charge acquired by a glass rod when it is rubbed with a silk cloth.

Electric charges produce electric fields.[2] A moving charge also produces a magnetic field.[3] The interaction of electric charges with an electromagnetic field (a combination of an electric and a magnetic field) is the source of the electromagnetic (or Lorentz) force,[4] which is one of the four fundamental interactions in physics. The study of photon-mediated interactions among charged particles is called quantum electrodynamics.[5]

The SI derived unit of electric charge is the coulomb (C) named after French physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb. In electrical engineering it is also common to use the ampere-hour (A⋅h). In physics and chemistry it is common to use the elementary charge (e) as a unit. Chemistry also uses the Faraday constant, which is the charge of one mole of elementary charges.

Overview

[edit]

Charge is the fundamental property of matter that exhibits electrostatic attraction or repulsion in the presence of other matter with charge. Electric charge is a characteristic property of many subatomic particles. The charges of free-standing particles are integer multiples of the elementary charge e; we say that electric charge is quantized. Michael Faraday, in his electrolysis experiments, was the first to note the discrete nature of electric charge. Robert Millikan's oil drop experiment demonstrated this fact directly, and measured the elementary charge. It has been discovered that one type of particle, quarks, have fractional charges of either −1/3 or +2/3, but it is believed they always occur in multiples of integral charge; free-standing quarks have never been observed.

By convention, the charge of an electron is negative, −e, while that of a proton is positive, +e. Charged particles whose charges have the same sign repel one another, and particles whose charges have different signs attract. Coulomb's law quantifies the electrostatic force between two particles by asserting that the force is proportional to the product of their charges, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. The charge of an antiparticle equals that of the corresponding particle, but with opposite sign.

The electric charge of a macroscopic object is the sum of the electric charges of the particles that it is made up of. This charge is often small, because matter is made of atoms, and atoms typically have equal numbers of protons and electrons, in which case their charges cancel out, yielding a net charge of zero, thus making the atom neutral.

An ion is an atom (or group of atoms) that has lost one or more electrons, giving it a net positive charge (cation), or that has gained one or more electrons, giving it a net negative charge (anion). Monatomic ions are formed from single atoms, while polyatomic ions are formed from two or more atoms that have been bonded together, in each case yielding an ion with a positive or negative net charge.

During the formation of macroscopic objects, constituent atoms and ions usually combine to form structures composed of neutral ionic compounds electrically bound to neutral atoms. Thus macroscopic objects tend toward being neutral overall, but macroscopic objects are rarely perfectly net neutral.

Sometimes macroscopic objects contain ions distributed throughout the material, rigidly bound in place, giving an overall net positive or negative charge to the object. Also, macroscopic objects made of conductive elements can more or less easily (depending on the element) take on or give off electrons, and then maintain a net negative or positive charge indefinitely. When the net electric charge of an object is non-zero and motionless, the phenomenon is known as static electricity. This can easily be produced by rubbing two dissimilar materials together, such as rubbing amber with fur or glass with silk. In this way, non-conductive materials can be charged to a significant degree, either positively or negatively. Charge taken from one material is moved to the other material, leaving an opposite charge of the same magnitude behind. The law of conservation of charge always applies, giving the object from which a negative charge is taken a positive charge of the same magnitude, and vice versa.

Even when an object's net charge is zero, the charge can be distributed non-uniformly in the object (e.g., due to an external electromagnetic field, or bound polar molecules). In such cases, the object is said to be polarized. The charge due to polarization is known as bound charge, while the charge on an object produced by electrons gained or lost from outside the object is called free charge. The motion of electrons in conductive metals in a specific direction is known as electric current.

Unit

[edit]The SI unit of quantity of electric charge is the coulomb (symbol: C). The coulomb is defined as the quantity of charge that passes through the cross section of an electrical conductor carrying one ampere for one second.[6] This unit was proposed in 1946 and ratified in 1948.[6] The lowercase symbol q is often used to denote a quantity of electric charge. The quantity of electric charge can be directly measured with an electrometer, or indirectly measured with a ballistic galvanometer.

The elementary charge is defined as a fundamental constant in the SI.[7] The value for elementary charge, when expressed in SI units, is exactly 1.602176634×10−19 C.[1]

After discovering the quantized character of charge, in 1891, George Stoney proposed the unit 'electron' for this fundamental unit of electrical charge. J. J. Thomson subsequently discovered the particle that we now call the electron in 1897. The unit is today referred to as elementary charge, fundamental unit of charge, or simply denoted e, with the charge of an electron being −e. The charge of an isolated system should be a multiple of the elementary charge e, even if at large scales charge seems to behave as a continuous quantity. In some contexts it is meaningful to speak of fractions of an elementary charge; for example, in the fractional quantum Hall effect.

The unit faraday is sometimes used in electrochemistry. One faraday is the magnitude of the charge of one mole of elementary charges,[8] i.e. 9.648533212...×104 C.

History

[edit]

From ancient times, people were familiar with four types of phenomena that today would all be explained using the concept of electric charge: (a) lightning, (b) the torpedo fish (or electric ray), (c) St Elmo's Fire, and (d) that amber rubbed with fur would attract small, light objects.[9] The first account of the amber effect is often attributed to the ancient Greek mathematician Thales of Miletus, who lived from c. 624 to c. 546 BC, but there are doubts about whether Thales left any writings;[10] his account about amber is known from an account from early 200s.[11] This account can be taken as evidence that the phenomenon was known since at least c. 600 BC, but Thales explained this phenomenon as evidence for inanimate objects having a soul.[11] In other words, there was no indication of any conception of electric charge. More generally, the ancient Greeks did not understand the connections among these four kinds of phenomena. The Greeks observed that the charged amber buttons could attract light objects such as hair. They also found that if they rubbed the amber for long enough, they could even get an electric spark to jump,[citation needed] but there is also a claim that no mention of electric sparks appeared until late 17th century.[12] This property derives from the triboelectric effect. In late 1100s, the substance jet, a compacted form of coal, was noted to have an amber effect,[13] and in the middle of the 1500s, Girolamo Fracastoro, discovered that diamond also showed this effect.[14] Some efforts were made by Fracastoro and others, especially Gerolamo Cardano to develop explanations for this phenomenon.[15]

In contrast to astronomy, mechanics, and optics, which had been studied quantitatively since antiquity, the start of ongoing qualitative and quantitative research into electrical phenomena can be marked with the publication of De Magnete by the English scientist William Gilbert in 1600.[16] In this book, there was a small section where Gilbert returned to the amber effect (as he called it) in addressing many of the earlier theories,[15] and coined the Neo-Latin word electrica (from ἤλεκτρον (ēlektron), the Greek word for amber). The Latin word was translated into English as electrics.[17] Gilbert is also credited with the term electrical, while the term electricity came later, first attributed to Sir Thomas Browne in his Pseudodoxia Epidemica from 1646.[18] (For more linguistic details see Etymology of electricity.) Gilbert hypothesized that this amber effect could be explained by an effluvium (a small stream of particles that flows from the electric object, without diminishing its bulk or weight) that acts on other objects. This idea of a material electrical effluvium was influential in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was a precursor to ideas developed in the 18th century about "electric fluid" (Dufay, Nollet, Franklin) and "electric charge".[19]

Around 1663 Otto von Guericke invented what was probably the first electrostatic generator, but he did not recognize it primarily as an electrical device and only conducted minimal electrical experiments with it.[20] Other European pioneers were Robert Boyle, who in 1675 published the first book in English that was devoted solely to electrical phenomena.[21] His work was largely a repetition of Gilbert's studies, but he also identified several more "electrics",[22] and noted mutual attraction between two bodies.[21]

In 1729 Stephen Gray was experimenting with static electricity, which he generated using a glass tube. He noticed that a cork, used to protect the tube from dust and moisture, also became electrified (charged). Further experiments (e.g., extending the cork by putting thin sticks into it) showed—for the first time—that electrical effluvia (as Gray called it) could be transmitted (conducted) over a distance. Gray managed to transmit charge with twine (765 feet) and wire (865 feet).[23] Through these experiments, Gray discovered the importance of different materials, which facilitated or hindered the conduction of electrical effluvia. John Theophilus Desaguliers, who repeated many of Gray's experiments, is credited with coining the terms conductors and insulators to refer to the effects of different materials in these experiments.[23] Gray also discovered electrical induction (i.e., where charge could be transmitted from one object to another without any direct physical contact). For example, he showed that by bringing a charged glass tube close to, but not touching, a lump of lead that was sustained by a thread, it was possible to make the lead become electrified (e.g., to attract and repel brass filings).[24] He attempted to explain this phenomenon with the idea of electrical effluvia.[25]

Gray's discoveries introduced an important shift in the historical development of knowledge about electric charge. The fact that electrical effluvia could be transferred from one object to another, opened the theoretical possibility that this property was not inseparably connected to the bodies that were electrified by rubbing.[26] In 1733 Charles François de Cisternay du Fay, inspired by Gray's work, made a series of experiments (reported in Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences), showing that more or less all substances could be 'electrified' by rubbing, except for metals and fluids[27] and proposed that electricity comes in two varieties that cancel each other, which he expressed in terms of a two-fluid theory.[28] When glass was rubbed with silk, du Fay said that the glass was charged with vitreous electricity, and, when amber was rubbed with fur, the amber was charged with resinous electricity. In contemporary understanding, positive charge is now defined as the charge of a glass rod after being rubbed with a silk cloth, but it is arbitrary which type of charge is called positive and which is called negative.[29] Another important two-fluid theory from this time was proposed by Jean-Antoine Nollet (1745).[30]

Up until about 1745, the main explanation for electrical attraction and repulsion was the idea that electrified bodies gave off an effluvium.[31] Benjamin Franklin started electrical experiments in late 1746,[32] and by 1750 had developed a one-fluid theory of electricity, based on an experiment that showed that a rubbed glass received the same, but opposite, charge strength as the cloth used to rub the glass.[32][33] Franklin imagined electricity as being a type of invisible fluid present in all matter and coined the term charge itself (as well as battery and some others[34]); for example, he believed that it was the glass in a Leyden jar that held the accumulated charge. He posited that rubbing insulating surfaces together caused this fluid to change location, and that a flow of this fluid constitutes an electric current. He also posited that when matter contained an excess of the fluid it was positively charged and when it had a deficit it was negatively charged. He identified the term positive with vitreous electricity and negative with resinous electricity after performing an experiment with a glass tube he had received from his overseas colleague Peter Collinson. The experiment had participant A charge the glass tube and participant B receive a shock to the knuckle from the charged tube. Franklin identified participant B to be positively charged after having been shocked by the tube.[35] There is some ambiguity about whether William Watson independently arrived at the same one-fluid explanation around the same time (1747). Watson, after seeing Franklin's letter to Collinson, claims that he had presented the same explanation as Franklin in spring 1747.[36] Franklin had studied some of Watson's works prior to making his own experiments and analysis, which was probably significant for Franklin's own theorizing.[37] One physicist suggests that Watson first proposed a one-fluid theory, which Franklin then elaborated further and more influentially.[38] A historian of science argues that Watson missed a subtle difference between his ideas and Franklin's, so that Watson misinterpreted his ideas as being similar to Franklin's.[39] In any case, there was no animosity between Watson and Franklin, and the Franklin model of electrical action, formulated in early 1747, eventually became widely accepted at that time.[37] After Franklin's work, effluvia-based explanations were rarely put forward.[40]

It is now known that the Franklin model was fundamentally correct. There is only one kind of electrical charge, and only one variable is required to keep track of the amount of charge.[41]

Until 1800 it was only possible to study conduction of electric charge by using an electrostatic discharge. In 1800 Alessandro Volta was the first to show that charge could be maintained in continuous motion through a closed path.[42]

In 1833, Michael Faraday sought to remove any doubt that electricity is identical, regardless of the source by which it is produced.[43] He discussed a variety of known forms, which he characterized as common electricity (e.g., static electricity, piezoelectricity, magnetic induction), voltaic electricity (e.g., electric current from a voltaic pile), and animal electricity (e.g., bioelectricity).

In 1838, Faraday raised a question about whether electricity was a fluid or fluids or a property of matter, like gravity. He investigated whether matter could be charged with one kind of charge independently of the other.[44] He came to the conclusion that electric charge was a relation between two or more bodies, because he could not charge one body without having an opposite charge in another body.[45]

In 1838, Faraday also put forth a theoretical explanation of electric force, while expressing neutrality about whether it originates from one, two, or no fluids.[46] He focused on the idea that the normal state of particles is to be nonpolarized, and that when polarized, they seek to return to their natural, nonpolarized state.

In developing a field theory approach to electrodynamics (starting in the mid-1850s), James Clerk Maxwell stops considering electric charge as a special substance that accumulates in objects, and starts to understand electric charge as a consequence of the transformation of energy in the field.[47] This pre-quantum understanding considered magnitude of electric charge to be a continuous quantity, even at the microscopic level.[47]

Role of charge in static electricity

[edit]Static electricity refers to the electric charge of an object and the related electrostatic discharge when two objects are brought together that are not at equilibrium. An electrostatic discharge creates a change in the charge of each of the two objects.

Electrification by sliding

[edit]When a piece of glass and a piece of resin—neither of which exhibit any electrical properties—are rubbed together and left with the rubbed surfaces in contact, they still exhibit no electrical properties. When separated, they attract each other.

A second piece of glass rubbed with a second piece of resin, then separated and suspended near the former pieces of glass and resin causes these phenomena:

- The two pieces of glass repel each other.

- Each piece of glass attracts each piece of resin.

- The two pieces of resin repel each other.

This attraction and repulsion is an electrical phenomenon, and the bodies that exhibit them are said to be electrified, or electrically charged. Bodies may be electrified in many other ways, as well as by sliding. The electrical properties of the two pieces of glass are similar to each other but opposite to those of the two pieces of resin: The glass attracts what the resin repels and repels what the resin attracts.

If a body electrified in any manner whatsoever behaves as the glass does, that is, if it repels the glass and attracts the resin, the body is said to be vitreously electrified, and if it attracts the glass and repels the resin it is said to be resinously electrified. All electrified bodies are either vitreously or resinously electrified.

An established convention in the scientific community defines vitreous electrification as positive, and resinous electrification as negative. The exactly opposite properties of the two kinds of electrification justify our indicating them by opposite signs, but the application of the positive sign to one rather than to the other kind must be considered as a matter of arbitrary convention—just as it is a matter of convention in mathematical diagram to reckon positive distances towards the right hand.[48]

Role of charge in electric current

[edit]Electric current is the flow of electric charge through an object. The most common charge carriers are the positively charged proton and the negatively charged electron. The movement of any of these charged particles constitutes an electric current. In many situations, it suffices to speak of the conventional current without regard to whether it is carried by positive charges moving in the direction of the conventional current or by negative charges moving in the opposite direction. This macroscopic viewpoint is an approximation that simplifies electromagnetic concepts and calculations.

At the opposite extreme, if one looks at the microscopic situation, one sees there are many ways of carrying an electric current, including: a flow of electrons; a flow of electron holes that act like positive particles; and both negative and positive particles (ions or other charged particles) flowing in opposite directions in an electrolytic solution or a plasma.

The direction of the conventional current in most metallic wires is opposite to the drift velocity of the actual charge carriers; i.e., the electrons.

Conservation of electric charge

[edit]The total electric charge of an isolated system remains constant regardless of changes within the system itself.[49] : 4 This law is inherent to all processes known to physics and can be derived in a local form from gauge invariance of the wave function. The conservation of charge results in the charge-current continuity equation. More generally, the rate of change in charge density ρ within a volume of integration V is equal to the area integral over the current density J through the closed surface S = ∂V, which is in turn equal to the net current I:

Thus, the conservation of electric charge, as expressed by the continuity equation, gives the result:

The charge transferred between times and is obtained by integrating both sides:

where I is the net outward current through a closed surface and q is the electric charge contained within the volume defined by the surface.

Relativistic invariance

[edit]Aside from the properties described in articles about electromagnetism, electric charge is a relativistic invariant. This means that any particle that has electric charge q has the same electric charge regardless of how fast it is travelling. This property has been experimentally verified by showing that the electric charge of one helium nucleus (two protons and two neutrons bound together in a nucleus and moving around at high speeds) is the same as that of two deuterium nuclei (one proton and one neutron bound together, but moving much more slowly than they would if they were in a helium nucleus).[50][51]

See also

[edit]- SI electromagnetism units

- Color charge

- Partial charge

- Positron or antielectron is an antiparticle or antimatter counterpart of the electron

References

[edit]- ^ a b "2022 CODATA Value: elementary charge". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. May 2024. Retrieved 2024-05-18.

- ^ Chabay, Ruth; Sherwood, Bruce (2015). Matter and interactions (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 867.

- ^ Chabay, Ruth; Sherwood, Bruce (2015). Matter and interactions (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 673.

- ^ Chabay, Ruth; Sherwood, Bruce (2015). Matter and interactions (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 942.

- ^ Rennie, Richard; Law, Jonathan, eds. (2019). "Quantum electrodynamics". A Dictionary of Physics (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198821472.

- ^ a b "CIPM, 1946: Resolution 2". BIPM.

- ^ The International System of Units (PDF), V3.01 (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, Aug 2024, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0, p. 127

- ^ Gambhir, RS; Banerjee, D; Durgapal, MC (1993). Foundations of Physics, Vol. 2. New Delhi: Wiley Eastern Limited. p. 51. ISBN 9788122405231. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Roller, Duane; Roller, D.H.D. (1954). The development of the concept of electric charge: Electricity from the Greeks to Coulomb. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 1.

- ^ O'Grady, Patricia F. (2002). Thales of Miletus: The Beginnings of Western Science and Philosophy. Ashgate. p. 8. ISBN 978-1351895378.

- ^ a b "Lives of the Eminent Philosophers by Diogenes Laërtius, Book 1, §24".

- ^ Roller, Duane; Roller, D.H.D. (1953). "The Prenatal History of Electrical Science". American Journal of Physics. 21 (5): 348. Bibcode:1953AmJPh..21..343R. doi:10.1119/1.1933449.

- ^ Roller, Duane; Roller, D.H.D. (1953). "The Prenatal History of Electrical Science". American Journal of Physics. 21 (5): 351. Bibcode:1953AmJPh..21..343R. doi:10.1119/1.1933449.

- ^ Roller, Duane; Roller, D.H.D. (1953). "The Prenatal History of Electrical Science". American Journal of Physics. 21 (5): 353. Bibcode:1953AmJPh..21..343R. doi:10.1119/1.1933449.

- ^ a b Roller, Duane; Roller, D.H.D. (1953). "The Prenatal History of Electrical Science". American Journal of Physics. 21 (5): 356. Bibcode:1953AmJPh..21..343R. doi:10.1119/1.1933449.

- ^ Roche, J.J. (1998). The mathematics of measurement. London: The Athlone Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0387915814.

- ^ Roller, Duane; Roller, D.H.D. (1954). The development of the concept of electric charge: Electricity from the Greeks to Coulomb. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 6–7.

Heilbron, J.L. (1979). Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Study of Early Modern Physics. University of California Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-520-03478-5. - ^ Brother Potamian; Walsh, J.J. (1909). Makers of electricity. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 70.

- ^ Baigrie, Brian (2007). Electricity and magnetism: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 11.

- ^ Heathcote, N.H. de V. (1950). "Guericke's sulphur globe". Annals of Science. 6 (3): 304. doi:10.1080/00033795000201981.

Heilbron, J.L. (1979). Electricity in the 17th and 18th centuries: a study of early Modern physics. University of California Press. pp. 215–218. ISBN 0-520-03478-3. - ^ a b Baigrie, Brian (2007). Electricity and magnetism: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 20.

- ^ Baigrie, Brian (2007). Electricity and magnetism: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 21.

- ^ a b Baigrie, Brian (2007). Electricity and magnetism: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 27.

- ^ Baigrie, Brian (2007). Electricity and magnetism: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 28.

- ^ Heilbron, J.L. (1979). Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Study of Early Modern Physics. University of California Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-520-03478-5.

- ^ Baigrie, Brian (2007). Electricity and magnetism: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 35.

- ^ Roller, Duane; Roller, D.H.D. (1954). The development of the concept of electric charge: Electricity from the Greeks to Coulomb. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 40.

- ^ Two Kinds of Electrical Fluid: Vitreous and Resinous – 1733. Charles François de Cisternay DuFay (1698–1739) Archived 2009-05-26 at the Wayback Machine. sparkmuseum.com

- ^ Wangsness, Roald K. (1986). Electromagnetic Fields (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. p. 40. ISBN 0-471-81186-6.

- ^ Heilbron, J.L. (1979). Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Study of Early Modern Physics. University of California Press. pp. 280–289. ISBN 978-0-520-03478-5.

- ^ Heilbron, John (2003). "Leyden jar and electrophore". In Heilbron, John (ed.). The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 459. ISBN 9780195112290.

- ^ a b Baigrie, Brian (2007). Electricity and magnetism: A historical perspective. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 38.

- ^ Guarnieri, Massimo (2014). "Electricity in the Age of Enlightenment". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 8 (3): 61. doi:10.1109/MIE.2014.2335431. S2CID 34246664.

- ^ "Electric charge and current - a short history | IOPSpark".

- ^ Franklin, Benjamin (1747-05-25). "Letter to Peter Collinson, May 25, 1747". Letter to Peter Collinson. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ^ Watson, William (1748). "Some further inquiries into the nature and properties of electricity". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 45: 100. doi:10.1098/rstl.1748.0004. S2CID 186207940.

- ^ a b Cohen, I. Bernard (1966). Franklin and Newton (reprint ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 390–413.

- ^ Weinberg, Steven (2003). The discovery of subatomic particles (rev ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780521823517.

- ^ Heilbron, J.L. (1979). Electricity in the 17th and 18th centuries: a study of early Modern physics. University of California Press. pp. 344–5. ISBN 0-520-03478-3.

- ^ Tricker, R.A.R (1965). Early electrodynamics: The first law of circulation. Oxford: Pergamon. p. 2. ISBN 9781483185361.

- ^ Denker, John (2007). "One Kind of Charge". www.av8n.com/physics. Archived from the original on 2016-02-05.

- ^ Zangwill, Andrew (2013). Modern Electrodynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-521-89697-9.

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1833). "Experimental researches in electricity — third series". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 123: 23–54. doi:10.1098/rstl.1833.0006. S2CID 111157008.

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1838). "Experimental researches in electricity — eleventh series". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 128: 4. doi:10.1098/rstl.1838.0002. S2CID 116482065.

§1168

- ^ Steinle, Friedrich (2013). "Electromagnetism and field physics". In Buchwald, Jed Z.; Fox, Robert (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the history of physics. Oxford University Press. p. 560.

- ^ Faraday, Michael (1838). "Experimental researches in electricity — fourteenth series". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 128: 265–282. doi:10.1098/rstl.1838.0014. S2CID 109146507.

- ^ a b Buchwald, Jed Z. (2013). "Electrodynamics from Thomson and Maxwell to Hertz". In Buchwald, Jed Z.; Fox, Robert (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the history of physics. Oxford University Press. p. 575.

- ^ James Clerk Maxwell (1891) A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, pp. 32–33, Dover Publications

- ^ Purcell, E. M. (1963). Berkeley Physics Course: Electricity and magnetism. United States: McGraw Hill.

- ^ Jefimenko, O.D. (1999). "Relativistic invariance of electric charge" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Naturforschung A. 54 (10–11): 637–644. Bibcode:1999ZNatA..54..637J. doi:10.1515/zna-1999-10-1113. S2CID 29149866. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- ^ Singal, A.K. (1992). "On the charge invariance and relativistic electric fields from a steady conduction current". Physics Letters A. 162 (2): 91–95. Bibcode:1992PhLA..162...91S. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(92)90982-R. ISSN 0375-9601.

External links

[edit] Media related to Electric charge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Electric charge at Wikimedia Commons- How fast does a charge decay?