Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Botany

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

|

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially their anatomy, taxonomy, and ecology.[1] A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who specialises in this field. "Plant" and "botany" may be defined more narrowly to include only land plants and their study, which is also known as phytology. Phytologists or botanists (in the strict sense) study approximately 410,000 species of land plants, including some 391,000 species of vascular plants (of which approximately 369,000 are flowering plants)[2] and approximately 20,000 bryophytes.[3]

Botany originated as prehistoric herbalism to identify and later cultivate plants that were edible, poisonous, and medicinal, making it one of the first endeavours of human investigation.[citation needed] Medieval physic gardens, often attached to monasteries, contained plants possibly having medicinal benefit. They were forerunners of the first botanical gardens attached to universities, founded from the 1540s onwards. One of the earliest was the Padua botanical garden. These gardens facilitated the academic study of plants. Efforts to catalogue and describe their collections were the beginnings of plant taxonomy and led in 1753 to the binomial system of nomenclature of Carl Linnaeus that remains in use to this day for the naming of all biological species.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, new techniques were developed for the study of plants, including methods of optical microscopy and live cell imaging, electron microscopy, analysis of chromosome number, plant chemistry and the structure and function of enzymes and other proteins. In the last two decades of the 20th century, botanists exploited the techniques of molecular genetic analysis, including genomics and proteomics and DNA sequences to classify plants more accurately.

Modern botany is a broad subject with contributions and insights from most other areas of science and technology. Research topics include the study of plant structure, growth and differentiation, reproduction, biochemistry and primary metabolism, chemical products, development, diseases, evolutionary relationships, systematics, and plant taxonomy. Dominant themes in 21st-century plant science are molecular genetics and epigenetics, which study the mechanisms and control of gene expression during differentiation of plant cells and tissues. Botanical research has diverse applications in providing staple foods, materials such as timber, oil, rubber, fibre and drugs, in modern horticulture, agriculture and forestry, plant propagation, breeding and genetic modification, in the synthesis of chemicals and raw materials for construction and energy production, in environmental management, and the maintenance of biodiversity.

Etymology

[edit]The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek word botanē (βοτάνη) meaning "pasture", "herbs" "grass", or "fodder";[4] Botanē is in turn derived from boskein (Greek: βόσκειν), "to feed" or "to graze".[5][6][7] Traditionally, botany has also included the study of fungi and algae by mycologists and phycologists respectively, with the study of these three groups of organisms remaining within the sphere of interest of the International Botanical Congress.

History

[edit]Early botany

[edit]

Botany originated as herbalism, the study and use of plants for their possible medicinal properties.[8] The early recorded history of botany includes many ancient writings and plant classifications. Examples of early botanical works have been found in ancient texts from India dating back to before 1100 BCE,[9][10] Ancient Egypt,[11] in archaic Avestan writings, and in works from China purportedly from before 221 BCE.[9][12]

Modern botany traces its roots back to Ancient Greece specifically to Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BCE), a student of Aristotle who invented and described many of its principles and is widely regarded in the scientific community as the "Father of Botany".[13] His major works, Enquiry into Plants and On the Causes of Plants, constitute the most important contributions to botanical science until the Middle Ages, almost seventeen centuries later.[13][14]

Another work from Ancient Greece that made an early impact on botany is De materia medica, a five-volume encyclopedia about preliminary herbal medicine written in the middle of the first century by Greek physician and pharmacologist Pedanius Dioscorides. De materia medica was widely read for more than 1,500 years.[15] Important contributions from the medieval Muslim world include Ibn Wahshiyya's Nabatean Agriculture, Abū Ḥanīfa Dīnawarī's (828–896) the Book of Plants, and Ibn Bassal's The Classification of Soils. In the early 13th century, Abu al-Abbas al-Nabati, and Ibn al-Baitar (d. 1248) wrote on botany in a systematic and scientific manner.[16][17][18]

In the mid-16th century, botanical gardens were founded in a number of Italian universities. The Padua botanical garden in 1545 is usually considered to be the first which is still in its original location. These gardens continued the practical value of earlier "physic gardens", often associated with monasteries, in which plants were cultivated for suspected medicinal uses. They supported the growth of botany as an academic subject. Lectures were given about the plants grown in the gardens. Botanical gardens came much later to northern Europe; the first in England was the University of Oxford Botanic Garden in 1621.[19]

German physician Leonhart Fuchs (1501–1566) was one of "the three German fathers of botany", along with theologian Otto Brunfels (1489–1534) and physician Hieronymus Bock (1498–1554) (also called Hieronymus Tragus).[20][21] Fuchs and Brunfels broke away from the tradition of copying earlier works to make original observations of their own. Bock created his own system of plant classification.

Physician Valerius Cordus (1515–1544) authored a botanically and pharmacologically important herbal Historia Plantarum in 1544 and a pharmacopoeia of lasting importance, the Dispensatorium in 1546.[22] Naturalist Conrad von Gesner (1516–1565) and herbalist John Gerard (1545 – c. 1611) published herbals covering the supposed medicinal uses of plants. Naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) was considered the father of natural history, which included the study of plants. In 1665, using an early microscope, Polymath Robert Hooke discovered cells (a term he coined) in cork, and a short time later in living plant tissue.[23]

Early modern botany

[edit]

During the 18th century, systems of plant identification were developed comparable to dichotomous keys, where unidentified plants are placed into taxonomic groups (e.g. family, genus and species) by making a series of choices between pairs of characters. The choice and sequence of the characters may be artificial in keys designed purely for identification (diagnostic keys) or more closely related to the natural or phyletic order of the taxa in synoptic keys.[24] By the 18th century, new plants for study were arriving in Europe in increasing numbers from newly discovered countries and the European colonies worldwide. In 1753, Carl Linnaeus published his Species Plantarum, a hierarchical classification of plant species that remains the reference point for modern botanical nomenclature. This established a standardised binomial or two-part naming scheme where the first name represented the genus and the second identified the species within the genus.[25] For the purposes of identification, Linnaeus's Systema Sexuale classified plants into 24 groups according to the number of their male sexual organs. The 24th group, Cryptogamia, included all plants with concealed reproductive parts, mosses, liverworts, ferns, algae and fungi.[26]

Increasing knowledge of plant anatomy, morphology and life cycles led to the realisation that there were more natural affinities between plants than the artificial sexual system of Linnaeus. Adanson (1763), de Jussieu (1789), and Candolle (1819) all proposed various alternative natural systems of classification that grouped plants using a wider range of shared characters and were widely followed. The Candollean system reflected his ideas of the progression of morphological complexity and the later Bentham & Hooker system, which was influential until the mid-19th century, was influenced by Candolle's approach. Darwin's publication of the Origin of Species in 1859 and his concept of common descent required modifications to the Candollean system to reflect evolutionary relationships as distinct from mere morphological similarity.[27]

In the 19th century botany was a socially acceptable hobby for upper-class women. These women would collect and paint flowers and plants from around the world with scientific accuracy. The paintings were used to record many species that could not be transported or maintained in other environments. Marianne North illustrated over 900 species in extreme detail with watercolor and oil paintings.[28] Her work and many other women's botany work was the beginning of popularizing botany to a wider audience.

Botany was greatly stimulated by the appearance of the first "modern" textbook, Matthias Schleiden's Grundzüge der Wissenschaftlichen Botanik, published in English in 1849 as Principles of Scientific Botany.[29] Schleiden was a microscopist and an early plant anatomist who co-founded the cell theory with Theodor Schwann and Rudolf Virchow and was among the first to grasp the significance of the cell nucleus that had been described by Robert Brown in 1831.[30] In 1855, Adolf Fick formulated Fick's laws that enabled the calculation of the rates of molecular diffusion in biological systems.[31]

Late modern botany

[edit]Building upon the gene-chromosome theory of heredity that originated with Gregor Mendel (1822–1884), August Weismann (1834–1914) proved that inheritance only takes place through gametes. No other cells can pass on inherited characters.[32] The work of Katherine Esau (1898–1997) on plant anatomy is still a major foundation of modern botany. Her books Plant Anatomy and Anatomy of Seed Plants have been key plant structural biology texts for more than half a century.[33][34]

The discipline of plant ecology was pioneered in the late 19th century by botanists such as Eugenius Warming, who produced the hypothesis that plants form communities, and his mentor and successor Christen C. Raunkiær whose system for describing plant life forms is still in use today. The concept that the composition of plant communities such as temperate broadleaf forest changes by a process of ecological succession was developed by Henry Chandler Cowles, Arthur Tansley and Frederic Clements. Clements is credited with the idea of climax vegetation as the most complex vegetation that an environment can support and Tansley introduced the concept of ecosystems to biology.[35][36][37] Building on the extensive earlier work of Alphonse de Candolle, Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943) produced accounts of the biogeography, centres of origin, and evolutionary history of economic plants.[38]

Particularly since the mid-1960s there have been advances in understanding of the physics of plant physiological processes such as transpiration (the transport of water within plant tissues), the temperature dependence of rates of water evaporation from the leaf surface and the molecular diffusion of water vapour and carbon dioxide through stomatal apertures. These developments, coupled with new methods for measuring the size of stomatal apertures, and the rate of photosynthesis have enabled precise description of the rates of gas exchange between plants and the atmosphere.[39][40] Innovations in statistical analysis by Ronald Fisher,[41] Frank Yates and others at Rothamsted Experimental Station facilitated rational experimental design and data analysis in botanical research.[42] The discovery and identification of the auxin plant hormones by Kenneth V. Thimann in 1948 enabled regulation of plant growth by externally applied chemicals. Frederick Campion Steward pioneered techniques of micropropagation and plant tissue culture controlled by plant hormones.[43] The synthetic auxin 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid or 2,4-D was one of the first commercial synthetic herbicides.[44]

20th century developments in plant biochemistry have been driven by modern techniques of organic chemical analysis, such as spectroscopy, chromatography and electrophoresis. With the rise of the related molecular-scale biological approaches of molecular biology, genomics, proteomics and metabolomics, the relationship between the plant genome and most aspects of the biochemistry, physiology, morphology and behaviour of plants can be subjected to detailed experimental analysis.[45] The concept originally stated by Gottlieb Haberlandt in 1902[46] that all plant cells are totipotent and can be grown in vitro ultimately enabled the use of genetic engineering experimentally to knock out a gene or genes responsible for a specific trait, or to add genes such as GFP that report when a gene of interest is being expressed. These technologies enable the biotechnological use of whole plants or plant cell cultures grown in bioreactors to synthesise pesticides, antibiotics or other pharmaceuticals, as well as the practical application of genetically modified crops designed for traits such as improved yield.[47]

Modern morphology recognises a continuum between the major morphological categories of root, stem (caulome), leaf (phyllome) and trichome.[48] Furthermore, it emphasises structural dynamics.[49] Modern systematics aims to reflect and discover phylogenetic relationships between plants.[50][51][52][53] Modern molecular phylogenetics largely ignores morphological characters, relying on DNA sequences as data. Molecular analysis of DNA sequences from most families of flowering plants enabled the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group to publish in 1998 a phylogeny of flowering plants, answering many of the questions about relationships among angiosperm families and species.[54] The theoretical possibility of a practical method for identification of plant species and commercial varieties by DNA barcoding is the subject of active current research.[55][56]

Branches of botany

[edit]Botany is divided along several axes.

Some subfields of botany relate to particular groups of organisms. Divisions related to the broader historical sense of botany include bacteriology, mycology (or fungology), and phycology – respectively, the study of bacteria, fungi, and algae – with lichenology as a subfield of mycology. The narrower sense of botany as the study of embryophytes (land plants) is called phytology. Bryology is the study of mosses (and in the broader sense also liverworts and hornworts). Pteridology (or filicology) is the study of ferns and allied plants. A number of other taxa of ranks varying from family to subgenus have terms for their study, including agrostology (or graminology) for the study of grasses, synantherology for the study of composites, and batology for the study of brambles.

Study can also be divided by guild rather than clade or grade. For example, dendrology is the study of woody plants.

Many divisions of biology have botanical subfields. These are commonly denoted by prefixing the word plant (e.g. plant taxonomy, plant ecology, plant anatomy, plant morphology, plant systematics), or prefixing or substituting the prefix phyto- (e.g. phytochemistry, phytogeography). The study of fossil plants is called palaeobotany. Other fields are denoted by adding or substituting the word botany (e.g. systematic botany).

Phytosociology is a subfield of plant ecology that classifies and studies communities of plants.

The intersection of fields from the above pair of categories gives rise to fields such as bryogeography, the study of the distribution of mosses.

Different parts of plants also give rise to their own subfields, including xylology, carpology (or fructology), and palynology, these being the study of wood, fruit and pollen/spores respectively.

Botany also overlaps on the one hand with agriculture, horticulture and silviculture, and on the other hand with medicine and pharmacology, giving rise to fields such as agronomy, horticultural botany, phytopathology, and phytopharmacology.

Scope and importance

[edit]

The study of plants is vital because they underpin almost all animal life on Earth by generating a large proportion of the oxygen and food that provide humans and other organisms with aerobic respiration with the chemical energy they need to exist. Plants, algae and cyanobacteria are the major groups of organisms that carry out photosynthesis, a process that uses the energy of sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide[57] into sugars that can be used both as a source of chemical energy and of organic molecules that are used in the structural components of cells.[58] As a by-product of photosynthesis, plants release oxygen into the atmosphere, a gas that is required by nearly all living things to carry out cellular respiration. In addition, they are influential in the global carbon and water cycles and plant roots bind and stabilise soils, preventing soil erosion.[59] Plants are crucial to the future of human society as they provide food, oxygen, biochemicals, and products for people, as well as creating and preserving soil.[60]

Historically, all living things were classified as either animals or plants[61] and botany covered the study of all organisms not considered animals.[62] Botanists examine both the internal functions and processes within plant organelles, cells, tissues, whole plants, plant populations and plant communities. At each of these levels, a botanist may be concerned with the classification (taxonomy), phylogeny and evolution, structure (anatomy and morphology), or function (physiology) of plant life.[63]

The strictest definition of "plant" includes only the "land plants" or embryophytes, which include seed plants (gymnosperms, including the pines, and flowering plants) and the free-sporing cryptogams including ferns, clubmosses, liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Embryophytes are multicellular eukaryotes descended from an ancestor that obtained its energy from sunlight by photosynthesis. They have life cycles with alternating haploid and diploid phases. The sexual haploid phase of embryophytes, known as the gametophyte, nurtures the developing diploid embryo sporophyte within its tissues for at least part of its life,[64] even in the seed plants, where the gametophyte itself is nurtured by its parent sporophyte.[65] Other groups of organisms that were previously studied by botanists include bacteria (now studied in bacteriology), fungi (mycology) – including lichen-forming fungi (lichenology), non-chlorophyte algae (phycology), and viruses (virology). However, attention is still given to these groups by botanists, and fungi (including lichens) and photosynthetic protists are usually covered in introductory botany courses.[66][67]

Palaeobotanists study ancient plants in the fossil record to provide information about the evolutionary history of plants. Cyanobacteria, the first oxygen-releasing photosynthetic organisms on Earth, are thought to have given rise to the ancestor of plants by entering into an endosymbiotic relationship with an early eukaryote, ultimately becoming the chloroplasts in plant cells. The new photosynthetic plants (along with their algal relatives) accelerated the rise in atmospheric oxygen started by the cyanobacteria, changing the ancient oxygen-free, reducing, atmosphere to one in which free oxygen has been abundant for more than 2 billion years.[68][69]

Among the important botanical questions of the 21st century are the role of plants as primary producers in the global cycling of life's basic ingredients: energy, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and water, and ways that our plant stewardship can help address the global environmental issues of resource management, conservation, human food security, biologically invasive organisms, carbon sequestration, climate change, and sustainability.[70]

Human nutrition

[edit]

Virtually all staple foods come either directly from primary production by plants, or indirectly from animals that eat them.[71] Plants and other photosynthetic organisms are at the base of most food chains because they use the energy from the sun and nutrients from the soil and atmosphere, converting them into a form that can be used by animals. This is what ecologists call the first trophic level.[72] The modern forms of the major staple foods, such as hemp, teff, maize, rice, wheat and other cereal grasses, pulses, bananas and plantains,[73] as well as hemp, flax and cotton grown for their fibres, are the outcome of prehistoric selection over thousands of years from among wild ancestral plants with the most desirable characteristics.[74]

Botanists study how plants produce food and how to increase yields, for example through plant breeding, making their work important to humanity's ability to feed the world and provide food security for future generations.[75] Botanists also study weeds, which are a considerable problem in agriculture, and the biology and control of plant pathogens in agriculture and natural ecosystems.[76] Ethnobotany is the study of the relationships between plants and people. When applied to the investigation of historical plant–people relationships ethnobotany may be referred to as archaeobotany or palaeoethnobotany.[77] Some of the earliest plant-people relationships arose between the indigenous people of Canada in identifying edible plants from inedible plants. This relationship the indigenous people had with plants was recorded by ethnobotanists.[78]

Plant biochemistry

[edit]Plant biochemistry is the study of the chemical processes used by plants. Some of these processes are used in their primary metabolism like the photosynthetic Calvin cycle and crassulacean acid metabolism.[79] Others make specialised materials like the cellulose and lignin used to build their bodies, and secondary products like resins and aroma compounds.

Plants and various other groups of photosynthetic eukaryotes collectively known as "algae" have unique organelles known as chloroplasts. Chloroplasts are thought to be descended from cyanobacteria that formed endosymbiotic relationships with ancient plant and algal ancestors. Chloroplasts and cyanobacteria contain the blue-green pigment chlorophyll a.[80] Chlorophyll a (as well as its plant and green algal-specific cousin chlorophyll b)[a] absorbs light in the blue-violet and orange/red parts of the spectrum while reflecting and transmitting the green light that we see as the characteristic colour of these organisms. The energy in the red and blue light that these pigments absorb is used by chloroplasts to make energy-rich carbon compounds from carbon dioxide and water by oxygenic photosynthesis, a process that generates molecular oxygen (O2) as a by-product.

The light energy captured by chlorophyll a is initially in the form of electrons (and later a proton gradient) that is used to make molecules of ATP and NADPH which temporarily store and transport energy. Their energy is used in the light-independent reactions of the Calvin cycle by the enzyme rubisco to produce molecules of the 3-carbon sugar glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate is the first product of photosynthesis and the raw material from which glucose and almost all other organic molecules of biological origin are synthesised. Some of the glucose is converted to starch which is stored in the chloroplast.[84] Starch is the characteristic energy store of most land plants and algae, while inulin, a polymer of fructose is used for the same purpose in the sunflower family Asteraceae. Some of the glucose is converted to sucrose (common table sugar) for export to the rest of the plant.

Unlike in animals (which lack chloroplasts), plants and their eukaryote relatives have delegated many biochemical roles to their chloroplasts, including synthesising all their fatty acids,[85][86] and most amino acids.[87] The fatty acids that chloroplasts make are used for many things, such as providing material to build cell membranes out of and making the polymer cutin which is found in the plant cuticle that protects land plants from drying out.[88]

Plants synthesise a number of unique polymers like the polysaccharide molecules cellulose, pectin and xyloglucan[89] from which the land plant cell wall is constructed.[90] Vascular land plants make lignin, a polymer used to strengthen the secondary cell walls of xylem tracheids and vessels to keep them from collapsing when a plant sucks water through them under water stress. Lignin is also used in other cell types like sclerenchyma fibres that provide structural support for a plant and is a major constituent of wood. Sporopollenin is a chemically resistant polymer found in the outer cell walls of spores and pollen of land plants responsible for the survival of early land plant spores and the pollen of seed plants in the fossil record. It is widely regarded as a marker for the start of land plant evolution during the Ordovician period.[91] The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today is much lower than it was when plants emerged onto land during the Ordovician and Silurian periods. Many monocots like maize and the pineapple and some dicots like the Asteraceae have since independently evolved[92] pathways like Crassulacean acid metabolism and the C4 carbon fixation pathway for photosynthesis which avoid the losses resulting from photorespiration in the more common C3 carbon fixation pathway. These biochemical strategies are unique to land plants.

Medicine and materials

[edit]Phytochemistry is a branch of plant biochemistry primarily concerned with the chemical substances produced by plants during secondary metabolism.[93] Some of these compounds are toxins such as the alkaloid coniine from hemlock. Others, such as the essential oils peppermint oil and lemon oil are useful for their aroma, as flavourings and spices (e.g., capsaicin), and in medicine as pharmaceuticals as in opium from opium poppies. Many medicinal and recreational drugs, such as tetrahydrocannabinol (active ingredient in cannabis), caffeine, morphine and nicotine come directly from plants. Others are simple derivatives of botanical natural products. For example, the pain killer aspirin is the acetyl ester of salicylic acid, originally isolated from the bark of willow trees,[94] and a wide range of opiate painkillers like heroin are obtained by chemical modification of morphine obtained from the opium poppy.[95] Popular stimulants come from plants, such as caffeine from coffee, tea and chocolate, and nicotine from tobacco. Most alcoholic beverages come from fermentation of carbohydrate-rich plant products such as barley (beer), rice (sake) and grapes (wine).[96] Native Americans have used various plants as ways of treating illness or disease for thousands of years.[97] This knowledge Native Americans have on plants has been recorded by enthnobotanists and then in turn has been used by pharmaceutical companies as a way of drug discovery.[98]

Plants can synthesise coloured dyes and pigments such as the anthocyanins responsible for the red colour of red wine, yellow weld and blue woad used together to produce Lincoln green, indoxyl, source of the blue dye indigo traditionally used to dye denim and the artist's pigments gamboge and rose madder.

Sugar, starch, cotton, linen, hemp, some types of rope, wood and particle boards, papyrus and paper, vegetable oils, wax, and natural rubber are examples of commercially important materials made from plant tissues or their secondary products. Charcoal, a pure form of carbon made by pyrolysis of wood, has a long history as a metal-smelting fuel, as a filter material and adsorbent and as an artist's material and is one of the three ingredients of gunpowder. Cellulose, the world's most abundant organic polymer,[99] can be converted into energy, fuels, materials and chemical feedstock. Products made from cellulose include rayon and cellophane, wallpaper paste, biobutanol and gun cotton. Sugarcane, rapeseed and soy are some of the plants with a highly fermentable sugar or oil content that are used as sources of biofuels, important alternatives to fossil fuels, such as biodiesel.[100] Sweetgrass was used by Native Americans to ward off bugs like mosquitoes.[101] These bug repelling properties of sweetgrass were later found by the American Chemical Society in the molecules phytol and coumarin.[101]

Plant ecology

[edit]

Plant ecology is the science of the functional relationships between plants and their habitats – the environments where they complete their life cycles. Plant ecologists study the composition of local and regional floras, their biodiversity, genetic diversity and fitness, the adaptation of plants to their environment, and their competitive or mutualistic interactions with other species.[103] Some ecologists even rely on empirical data from indigenous people that is gathered by ethnobotanists.[104] This information can relay a great deal of information on how the land once was thousands of years ago and how it has changed over that time.[104] The goals of plant ecology are to understand the causes of their distribution patterns, productivity, environmental impact, evolution, and responses to environmental change.[105]

Plants depend on certain edaphic (soil) and climatic factors in their environment but can modify these factors too. For example, they can change their environment's albedo, increase runoff interception, stabilise mineral soils and develop their organic content, and affect local temperature. Plants compete with other organisms in their ecosystem for resources.[106][107] They interact with their neighbours at a variety of spatial scales in groups, populations and communities that collectively constitute vegetation. Regions with characteristic vegetation types and dominant plants as well as similar abiotic and biotic factors, climate, and geography make up biomes like tundra or tropical rainforest.[108]

Herbivores eat plants, but plants can defend themselves and some species are parasitic or even carnivorous. Other organisms form mutually beneficial relationships with plants. For example, mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia provide plants with nutrients in exchange for food, ants are recruited by ant plants to provide protection,[109] honey bees, bats and other animals pollinate flowers[110][111] and humans and other animals[112] act as dispersal vectors to spread spores and seeds.

Plants, climate and environmental change

[edit]Plant responses to climate and other environmental changes can inform our understanding of how these changes affect ecosystem function and productivity. For example, plant phenology can be a useful proxy for temperature in historical climatology, and the biological impact of climate change and global warming. Palynology, the analysis of fossil pollen deposits in sediments from thousands or millions of years ago allows the reconstruction of past climates.[113] Estimates of atmospheric CO2 concentrations since the Palaeozoic have been obtained from stomatal densities and the leaf shapes and sizes of ancient land plants.[114] Ozone depletion can expose plants to higher levels of ultraviolet radiation-B (UV-B), resulting in lower growth rates.[115] Moreover, information from studies of community ecology, plant systematics, and taxonomy is essential to understanding vegetation change, habitat destruction and species extinction.[116]

Genetics

[edit]

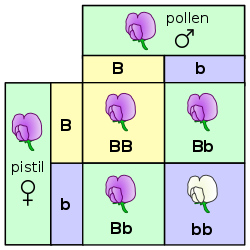

Inheritance in plants follows the same fundamental principles of genetics as in other multicellular organisms. Gregor Mendel discovered the genetic laws of inheritance by studying inherited traits such as shape in Pisum sativum (peas). What Mendel learned from studying plants has had far-reaching benefits outside of botany. Similarly, "jumping genes" were discovered by Barbara McClintock while she was studying maize.[117] Nevertheless, there are some distinctive genetic differences between plants and other organisms.

Species boundaries in plants may be weaker than in animals, and cross species hybrids are often possible. A familiar example is peppermint, Mentha × piperita, a sterile hybrid between Mentha aquatica and spearmint, Mentha spicata.[118] The many cultivated varieties of wheat are the result of multiple inter- and intra-specific crosses between wild species and their hybrids.[119] Angiosperms with monoecious flowers often have self-incompatibility mechanisms that operate between the pollen and stigma so that the pollen either fails to reach the stigma or fails to germinate and produce male gametes.[120] This is one of several methods used by plants to promote outcrossing.[121] In many land plants the male and female gametes are produced by separate individuals. These species are said to be dioecious when referring to vascular plant sporophytes and dioicous when referring to bryophyte gametophytes.[122]

Charles Darwin in his 1878 book The Effects of Cross and Self-Fertilization in the Vegetable Kingdom[123] at the start of chapter XII noted "The first and most important of the conclusions which may be drawn from the observations given in this volume, is that generally cross-fertilisation is beneficial and self-fertilisation often injurious, at least with the plants on which I experimented." An important adaptive benefit of outcrossing is that it allows the masking of deleterious mutations in the genome of progeny. This beneficial effect is also known as hybrid vigor or heterosis. Once outcrossing is established, subsequent switching to inbreeding becomes disadvantageous since it allows expression of the previously masked deleterious recessive mutations, commonly referred to as inbreeding depression.

Unlike in higher animals, where parthenogenesis is rare, asexual reproduction may occur in plants by several different mechanisms. The formation of stem tubers in potato is one example. Particularly in arctic or alpine habitats, where opportunities for fertilisation of flowers by animals are rare, plantlets or bulbs, may develop instead of flowers, replacing sexual reproduction with asexual reproduction and giving rise to clonal populations genetically identical to the parent. This is one of several types of apomixis that occur in plants. Apomixis can also happen in a seed, producing a seed that contains an embryo genetically identical to the parent.[124]

Most sexually reproducing organisms are diploid, with paired chromosomes, but doubling of their chromosome number may occur due to errors in cytokinesis. This can occur early in development to produce an autopolyploid or partly autopolyploid organism, or during normal processes of cellular differentiation to produce some cell types that are polyploid (endopolyploidy), or during gamete formation. An allopolyploid plant may result from a hybridisation event between two different species. Both autopolyploid and allopolyploid plants can often reproduce normally, but may be unable to cross-breed successfully with the parent population because there is a mismatch in chromosome numbers. These plants that are reproductively isolated from the parent species but live within the same geographical area, may be sufficiently successful to form a new species.[125] Some otherwise sterile plant polyploids can still reproduce vegetatively or by seed apomixis, forming clonal populations of identical individuals.[125] Durum wheat is a fertile tetraploid allopolyploid, while bread wheat is a fertile hexaploid. The commercial banana is an example of a sterile, seedless triploid hybrid. Common dandelion is a triploid that produces viable seeds by apomictic seed.

As in other eukaryotes, the inheritance of endosymbiotic organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts in plants is non-Mendelian. Chloroplasts are inherited through the male parent in gymnosperms but often through the female parent in flowering plants.[126]

Molecular genetics

[edit]

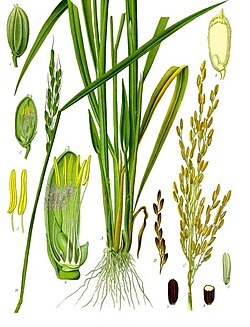

A considerable amount of new knowledge about plant function comes from studies of the molecular genetics of model plants such as the Thale cress, Arabidopsis thaliana, a weedy species in the mustard family (Brassicaceae).[93] The genome or hereditary information contained in the genes of this species is encoded by about 135 million base pairs of DNA, forming one of the smallest genomes among flowering plants. Arabidopsis was the first plant to have its genome sequenced, in 2000.[127] The sequencing of some other relatively small genomes, of rice (Oryza sativa)[128] and Brachypodium distachyon,[129] has made them important model species for understanding the genetics, cellular and molecular biology of cereals, grasses and monocots generally.

Model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana are used for studying the molecular biology of plant cells and the chloroplast. Ideally, these organisms have small genomes that are well known or completely sequenced, small stature and short generation times. Corn has been used to study mechanisms of photosynthesis and phloem loading of sugar in C4 plants.[130] The single celled green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, while not an embryophyte itself, contains a green-pigmented chloroplast related to that of land plants, making it useful for study.[131] A red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae has also been used to study some basic chloroplast functions.[132] Spinach,[133] peas,[134] soybeans and a moss Physcomitrella patens are commonly used to study plant cell biology.[135]

Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a soil rhizosphere bacterium, can attach to plant cells and infect them with a callus-inducing Ti plasmid by horizontal gene transfer, causing a callus infection called crown gall disease. Schell and Van Montagu (1977) hypothesised that the Ti plasmid could be a natural vector for introducing the Nif gene responsible for nitrogen fixation in the root nodules of legumes and other plant species.[136] Today, genetic modification of the Ti plasmid is one of the main techniques for introduction of transgenes to plants and the creation of genetically modified crops.

Epigenetics

[edit]Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in the underlying DNA sequence[137] but cause the organism's genes to behave (or "express themselves") differently.[138] One example of epigenetic change is the marking of the genes by DNA methylation which determines whether they will be expressed or not. Gene expression can also be controlled by repressor proteins that attach to silencer regions of the DNA and prevent that region of the DNA code from being expressed. Epigenetic marks may be added or removed from the DNA during programmed stages of development of the plant, and are responsible, for example, for the differences between anthers, petals and normal leaves, despite the fact that they all have the same underlying genetic code. Epigenetic changes may be temporary or may remain through successive cell divisions for the remainder of the cell's life. Some epigenetic changes have been shown to be heritable,[139] while others are reset in the germ cells.

Epigenetic changes in eukaryotic biology serve to regulate the process of cellular differentiation. During morphogenesis, totipotent stem cells become the various pluripotent cell lines of the embryo, which in turn become fully differentiated cells. A single fertilised egg cell, the zygote, gives rise to the many different plant cell types including parenchyma, xylem vessel elements, phloem sieve tubes, guard cells of the epidermis, etc. as it continues to divide. The process results from the epigenetic activation of some genes and inhibition of others.[140]

Unlike animals, many plant cells, particularly those of the parenchyma, do not terminally differentiate, remaining totipotent with the ability to give rise to a new individual plant. Exceptions include highly lignified cells, the sclerenchyma and xylem which are dead at maturity, and the phloem sieve tubes which lack nuclei. While plants use many of the same epigenetic mechanisms as animals, such as chromatin remodelling, an alternative hypothesis is that plants set their gene expression patterns using positional information from the environment and surrounding cells to determine their developmental fate.[141]

Epigenetic changes can lead to paramutations, which do not follow the Mendelian heritage rules. These epigenetic marks are carried from one generation to the next, with one allele inducing a change on the other.[142]

Plant evolution

[edit]

The chloroplasts of plants have a number of biochemical, structural and genetic similarities to cyanobacteria, (commonly but incorrectly known as "blue-green algae") and are thought to be derived from an ancient endosymbiotic relationship between an ancestral eukaryotic cell and a cyanobacterial resident.[143][144][145][146]

The algae are a polyphyletic group and are placed in various divisions, some more closely related to plants than others. There are many differences between them in features such as cell wall composition, biochemistry, pigmentation, chloroplast structure and nutrient reserves. The algal division Charophyta, sister to the green algal division Chlorophyta, is considered to contain the ancestor of true plants.[147] The Charophyte class Charophyceae and the land plant sub-kingdom Embryophyta together form the monophyletic group or clade Streptophytina.[148]

Nonvascular land plants are embryophytes that lack the vascular tissues xylem and phloem. They include mosses, liverworts and hornworts. Pteridophytic vascular plants with true xylem and phloem that reproduced by spores germinating into free-living gametophytes evolved during the Silurian period and diversified into several lineages during the late Silurian and early Devonian. Representatives of the lycopods have survived to the present day. By the end of the Devonian period, several groups, including the lycopods, sphenophylls and progymnosperms, had independently evolved "megaspory" – their spores were of two distinct sizes, larger megaspores and smaller microspores. Their reduced gametophytes developed from megaspores retained within the spore-producing organs (megasporangia) of the sporophyte, a condition known as endospory. Seeds consist of an endosporic megasporangium surrounded by one or two sheathing layers (integuments). The young sporophyte develops within the seed, which on germination splits to release it. The earliest known seed plants date from the latest Devonian Famennian stage.[149][150] Following the evolution of the seed habit, seed plants diversified, giving rise to a number of now-extinct groups, including seed ferns, as well as the modern gymnosperms and angiosperms.[151] Gymnosperms produce "naked seeds" not fully enclosed in an ovary; modern representatives include conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and Gnetales. Angiosperms produce seeds enclosed in a structure such as a carpel or an ovary.[152][153] Ongoing research on the molecular phylogenetics of living plants appears to show that the angiosperms are a sister clade to the gymnosperms.[154]

Plant physiology

[edit]

Plant physiology encompasses all the internal chemical and physical activities of plants associated with life.[155] Chemicals obtained from the air, soil and water form the basis of all plant metabolism. The energy of sunlight, captured by oxygenic photosynthesis and released by cellular respiration, is the basis of almost all life. Photoautotrophs, including all green plants, algae and cyanobacteria gather energy directly from sunlight by photosynthesis. Heterotrophs including all animals, all fungi, all completely parasitic plants, and non-photosynthetic bacteria take in organic molecules produced by photoautotrophs and respire them or use them in the construction of cells and tissues.[156] Respiration is the oxidation of carbon compounds by breaking them down into simpler structures to release the energy they contain, essentially the opposite of photosynthesis.[157]

Molecules are moved within plants by transport processes that operate at a variety of spatial scales. Subcellular transport of ions, electrons and molecules such as water and enzymes occurs across cell membranes. Minerals and water are transported from roots to other parts of the plant in the transpiration stream. Diffusion, osmosis, and active transport and mass flow are all different ways transport can occur.[158] Examples of elements that plants need to transport are nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. In vascular plants, these elements are extracted from the soil as soluble ions by the roots and transported throughout the plant in the xylem. Most of the elements required for plant nutrition come from the chemical breakdown of soil minerals.[159] Sucrose produced by photosynthesis is transported from the leaves to other parts of the plant in the phloem and plant hormones are transported by a variety of processes.

Plant hormones

[edit]

2 With the sun at an angle and only shining on one side of the shoot, auxin moves to the opposite side and stimulates cell elongation there.

3 and 4 Extra growth on that side causes the shoot to bend towards the sun.[160]

Plants are not passive, but respond to external signals such as light, touch, and injury by moving or growing towards or away from the stimulus, as appropriate. Tangible evidence of touch sensitivity is the almost instantaneous collapse of leaflets of Mimosa pudica, the insect traps of Venus flytrap and bladderworts, and the pollinia of orchids.[161]

The hypothesis that plant growth and development is coordinated by plant hormones or plant growth regulators first emerged in the late 19th century. Darwin experimented on the movements of plant shoots and roots towards light[162] and gravity, and concluded "It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the tip of the radicle . . acts like the brain of one of the lower animals . . directing the several movements".[163] About the same time, the role of auxins (from the Greek auxein, to grow) in control of plant growth was first outlined by the Dutch scientist Frits Went.[164] The first known auxin, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), which promotes cell growth, was only isolated from plants about 50 years later.[165] This compound mediates the tropic responses of shoots and roots towards light and gravity.[166] The finding in 1939 that plant callus could be maintained in culture containing IAA, followed by the observation in 1947 that it could be induced to form roots and shoots by controlling the concentration of growth hormones were key steps in the development of plant biotechnology and genetic modification.[167]

Cytokinins are a class of plant hormones named for their control of cell division (especially cytokinesis). The natural cytokinin zeatin was discovered in corn, Zea mays, and is a derivative of the purine adenine. Zeatin is produced in roots and transported to shoots in the xylem where it promotes cell division, bud development, and the greening of chloroplasts.[168][169] The gibberelins, such as gibberelic acid are diterpenes synthesised from acetyl CoA via the mevalonate pathway. They are involved in the promotion of germination and dormancy-breaking in seeds, in regulation of plant height by controlling stem elongation and the control of flowering.[170] Abscisic acid (ABA) occurs in all land plants except liverworts, and is synthesised from carotenoids in the chloroplasts and other plastids. It inhibits cell division, promotes seed maturation, and dormancy, and promotes stomatal closure. It was so named because it was originally thought to control abscission.[171] Ethylene is a gaseous hormone that is produced in all higher plant tissues from methionine. It is now known to be the hormone that stimulates or regulates fruit ripening and abscission,[172][173] and it, or the synthetic growth regulator ethephon which is rapidly metabolised to produce ethylene, are used on industrial scale to promote ripening of cotton, pineapples and other climacteric crops.

Another class of phytohormones is the jasmonates, first isolated from the oil of Jasminum grandiflorum[174] which regulates wound responses in plants by unblocking the expression of genes required in the systemic acquired resistance response to pathogen attack.[175]

In addition to being the primary energy source for plants, light functions as a signalling device, providing information to the plant, such as how much sunlight the plant receives each day. This can result in adaptive changes in a process known as photomorphogenesis. Phytochromes are the photoreceptors in a plant that are sensitive to light.[176]

Plant anatomy and morphology

[edit]

Plant anatomy is the study of the structure of plant cells and tissues, whereas plant morphology is the study of their external form.[177] All plants are multicellular eukaryotes, their DNA stored in nuclei.[178][179] The characteristic features of plant cells that distinguish them from those of animals and fungi include a primary cell wall composed of the polysaccharides cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin,[180] larger vacuoles than in animal cells and the presence of plastids with unique photosynthetic and biosynthetic functions as in the chloroplasts. Other plastids contain storage products such as starch (amyloplasts) or lipids (elaioplasts). Uniquely, streptophyte cells and those of the green algal order Trentepohliales[181] divide by construction of a phragmoplast as a template for building a cell plate late in cell division.[84]

The bodies of vascular plants including clubmosses, ferns and seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) generally have aerial and subterranean subsystems. The shoots consist of stems bearing green photosynthesising leaves and reproductive structures. The underground vascularised roots bear root hairs at their tips and generally lack chlorophyll.[183] Non-vascular plants, the liverworts, hornworts and mosses do not produce ground-penetrating vascular roots and most of the plant participates in photosynthesis.[184] The sporophyte generation is nonphotosynthetic in liverworts but may be able to contribute part of its energy needs by photosynthesis in mosses and hornworts.[185]

The root system and the shoot system are interdependent – the usually nonphotosynthetic root system depends on the shoot system for food, and the usually photosynthetic shoot system depends on water and minerals from the root system.[183] Cells in each system are capable of creating cells of the other and producing adventitious shoots or roots.[186] Stolons and tubers are examples of shoots that can grow roots.[187] Roots that spread out close to the surface, such as those of willows, can produce shoots and ultimately new plants.[188] In the event that one of the systems is lost, the other can often regrow it. In fact it is possible to grow an entire plant from a single leaf, as is the case with plants in Streptocarpus sect. Saintpaulia,[189] or even a single cell – which can dedifferentiate into a callus (a mass of unspecialised cells) that can grow into a new plant.[186] In vascular plants, the xylem and phloem are the conductive tissues that transport resources between shoots and roots. Roots are often adapted to store food such as sugars or starch,[183] as in sugar beets and carrots.[188]

Stems mainly provide support to the leaves and reproductive structures, but can store water in succulent plants such as cacti, food as in potato tubers, or reproduce vegetatively as in the stolons of strawberry plants or in the process of layering.[190] Leaves gather sunlight and carry out photosynthesis.[191] Large, flat, flexible, green leaves are called foliage leaves.[192] Gymnosperms, such as conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetophytes are seed-producing plants with open seeds.[193] Angiosperms are seed-producing plants that produce flowers and have enclosed seeds.[152] Woody plants, such as azaleas and oaks, undergo a secondary growth phase resulting in two additional types of tissues: wood (secondary xylem) and bark (secondary phloem and cork). All gymnosperms and many angiosperms are woody plants.[194] Some plants reproduce sexually, some asexually, and some via both means.[195]

Although reference to major morphological categories such as root, stem, leaf, and trichome are useful, one has to keep in mind that these categories are linked through intermediate forms so that a continuum between the categories results.[196] Furthermore, structures can be seen as processes, that is, process combinations.[49]

Systematic botany

[edit]

Systematic botany is part of systematic biology, which is concerned with the range and diversity of organisms and their relationships, particularly as determined by their evolutionary history.[197] It involves, or is related to, biological classification, scientific taxonomy and phylogenetics. Biological classification is the method by which botanists group organisms into categories such as genera or species. Biological classification is a form of scientific taxonomy. Modern taxonomy is rooted in the work of Carl Linnaeus, who grouped species according to shared physical characteristics. These groupings have since been revised to align better with the Darwinian principle of common descent – grouping organisms by ancestry rather than superficial characteristics. While scientists do not always agree on how to classify organisms, molecular phylogenetics, which uses DNA sequences as data, has driven many recent revisions along evolutionary lines and is likely to continue to do so. The dominant classification system is called Linnaean taxonomy. It includes ranks and binomial nomenclature. The nomenclature of botanical organisms is codified in the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) and administered by the International Botanical Congress.[198][199]

Kingdom Plantae belongs to Domain Eukaryota and is broken down recursively until each species is separately classified. The order is: Kingdom; Phylum (or Division); Class; Order; Family; Genus (plural genera); Species. The scientific name of a plant represents its genus and its species within the genus, resulting in a single worldwide name for each organism.[199] For example, the tiger lily is Lilium columbianum. Lilium is the genus, and columbianum the specific epithet. The combination is the name of the species. When writing the scientific name of an organism, it is proper to capitalise the first letter in the genus and put all of the specific epithet in lowercase. Additionally, the entire term is ordinarily italicised (or underlined when italics are not available).[200][201][202]

The evolutionary relationships and heredity of a group of organisms is called its phylogeny. Phylogenetic studies attempt to discover phylogenies. The basic approach is to use similarities based on shared inheritance to determine relationships.[203] As an example, species of Pereskia are trees or bushes with prominent leaves. They do not obviously resemble a typical leafless cactus such as an Echinocactus. However, both Pereskia and Echinocactus have spines produced from areoles (highly specialised pad-like structures) suggesting that the two genera are indeed related.[204][205]

Judging relationships based on shared characters requires care, since plants may resemble one another through convergent evolution in which characters have arisen independently. Some euphorbias have leafless, rounded bodies adapted to water conservation similar to those of globular cacti, but characters such as the structure of their flowers make it clear that the two groups are not closely related. The cladistic method takes a systematic approach to characters, distinguishing between those that carry no information about shared evolutionary history – such as those evolved separately in different groups (homoplasies) or those left over from ancestors (plesiomorphies) – and derived characters, which have been passed down from innovations in a shared ancestor (apomorphies). Only derived characters, such as the spine-producing areoles of cacti, provide evidence for descent from a common ancestor. The results of cladistic analyses are expressed as cladograms: tree-like diagrams showing the pattern of evolutionary branching and descent.[206]

From the 1990s onwards, the predominant approach to constructing phylogenies for living plants has been molecular phylogenetics, which uses molecular characters, particularly DNA sequences, rather than morphological characters like the presence or absence of spines and areoles. The difference is that the genetic code itself is used to decide evolutionary relationships, instead of being used indirectly via the characters it gives rise to. Clive Stace describes this as having "direct access to the genetic basis of evolution."[207] As a simple example, prior to the use of genetic evidence, fungi were thought either to be plants or to be more closely related to plants than animals. Genetic evidence suggests that the true evolutionary relationship of multicelled organisms is as shown in the cladogram below – fungi are more closely related to animals than to plants.[208]

| |||||||||||||

In 1998, the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group published a phylogeny for flowering plants based on an analysis of DNA sequences from most families of flowering plants. As a result of this work, many questions, such as which families represent the earliest branches of angiosperms, have now been answered.[54] Investigating how plant species are related to each other allows botanists to better understand the process of evolution in plants.[209] Despite the study of model plants and increasing use of DNA evidence, there is ongoing work and discussion among taxonomists about how best to classify plants into various taxa.[210] Technological developments such as computers and electron microscopes have greatly increased the level of detail studied and speed at which data can be analysed.[211]

Symbols

[edit]A few symbols are in current use in botany. A number of others are obsolete; for example, Linnaeus used planetary symbols ⟨♂⟩ (Mars) for biennial plants, ⟨♃⟩ (Jupiter) for herbaceous perennials and ⟨♄⟩ (Saturn) for woody perennials, based on the planets' orbital periods of 2, 12 and 30 years; and Willd used ⟨♄⟩ (Saturn) for neuter in addition to ⟨☿⟩ (Mercury) for hermaphroditic.[212] The following symbols are still used:[213]

- ♀ female

- ♂ male

- ⚥ hermaphrodite/bisexual

- ⚲ vegetative (asexual) reproduction

- ◊ sex unknown

- ☉ annual

- ⚇ biennial

- ♾ perennial

- ☠ poisonous

- 🛈 further information

- × crossbred hybrid

- + grafted hybrid

See also

[edit]- Branches of botany

- Evolution of plants

- Floristics

- Glossary of botanical terms

- Glossary of plant morphology

- List of botany journals

- List of botanists

- List of botanical gardens

- List of botanists by author abbreviation

- List of domesticated plants

- List of flowers

- List of systems of plant taxonomy

- Outline of botany

- Timeline of British botany

Notes

[edit]- ^ Chlorophyll b is also found in some cyanobacteria. A bunch of other chlorophylls exist in cyanobacteria and certain algal groups, but none of them are found in land plants.[81][82][83]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "botany (n.), sense 1.a," September 2024, "The branch of science concerned with the study of plants, esp. as observed in the field, and in their taxonomic, morphological, anatomical, and ecological aspects."

- ^ RGB Kew 2016.

- ^ The Plant List & 2013.

- ^ "βοτάνη - LSJ". LSJ. Internet Archive. 27 January 2021. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1940.

- ^ Gordh & Headrick 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary 2012.

- ^ Sumner 2000, p. 16.

- ^ a b Reed 1942, pp. 7–29.

- ^ Oberlies 1998, p. 155.

- ^ Manniche 2006.

- ^ Needham, Lu & Huang 1986.

- ^ a b Greene 1909, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Bennett & Hammond 1902, p. 30.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, p. 532.

- ^ Dallal 2010, p. 197.

- ^ Panaino 2002, p. 93.

- ^ Levey 1973, p. 116.

- ^ Hill 1915.

- ^ National Museum of Wales 2007.

- ^ Yaniv & Bachrach 2005, p. 157.

- ^ Sprague & Sprague 1939.

- ^ Waggoner 2001.

- ^ Scharf 2009, pp. 73–117.

- ^ Capon 2005, pp. 220–223.

- ^ Hoek, Mann & Jahns 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Starr 2009, pp. 299–.

- ^ Ross, Ailsa (2015-04-22). "The Victorian Gentlewoman Who Documented 900 Plant Species". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2024-06-05.

- ^ Morton 1981, p. 377.

- ^ Harris 2000, pp. 76–81.

- ^ Small 2012, pp. 118–.

- ^ Karp 2009, p. 382.

- ^ National Science Foundation 1989.

- ^ Chaffey 2007, pp. 481–482.

- ^ Tansley 1935, pp. 299–302.

- ^ Willis 1997, pp. 267–271.

- ^ Morton 1981, p. 457.

- ^ de Candolle 2006, pp. 9–25, 450–465.

- ^ Jasechko et al. 2013, pp. 347–350.

- ^ Nobel 1983, p. 608.

- ^ Yates & Mather 1963, pp. 91–129.

- ^ Finney 1995, pp. 554–573.

- ^ Cocking 1993.

- ^ Cousens & Mortimer 1995.

- ^ Ehrhardt & Frommer 2012, pp. 1–21.

- ^ Haberlandt 1902, pp. 69–92.

- ^ Leonelli et al. 2012.

- ^ Sattler & Jeune 1992, pp. 249–262.

- ^ a b Sattler 1992, pp. 708–714.

- ^ Ereshefsky 1997, pp. 493–519.

- ^ Gray & Sargent 1889, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Medbury 1993, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Judd et al. 2002, pp. 347–350.

- ^ a b Burger 2013.

- ^ Kress et al. 2005, pp. 8369–8374.

- ^ Janzen et al. 2009, pp. 12794–12797.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, p. 1240.

- ^ Gust 1996.

- ^ Missouri Botanical Garden 2009.

- ^ Chapman et al. 2001, p. 56.

- ^ Braselton 2013.

- ^ Ben-Menahem 2009, p. 5368.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, p. 602.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 619–620.

- ^ Capon 2005, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Cleveland Museum of Natural History 2012.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 516–517.

- ^ Botanical Society of America 2013.

- ^ Ben-Menahem 2009, pp. 5367–5368.

- ^ Butz 2007, pp. 534–553.

- ^ Stover & Simmonds 1987, pp. 106–126.

- ^ Zohary & Hopf 2000, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Floros, Newsome & Fisher 2010.

- ^ Schoening 2005.

- ^ Acharya & Anshu 2008, p. 440.

- ^ Kuhnlein & Turner 1991.

- ^ Lüttge 2006, pp. 7–25.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 190–193.

- ^ Kim & Archibald 2009, pp. 1–39.

- ^ Howe et al. 2008, pp. 2675–2685.

- ^ Takaichi 2011, pp. 1101–1118.

- ^ a b Lewis & McCourt 2004, pp. 1535–1556.

- ^ Padmanabhan & Dinesh-Kumar 2010, pp. 1368–1380.

- ^ Schnurr et al. 2002, pp. 1700–1709.

- ^ Ferro et al. 2002, pp. 11487–11492.

- ^ Kolattukudy 1996, pp. 83–108.

- ^ Fry 1989, pp. 1–11.

- ^ Thompson & Fry 2001, pp. 23–34.

- ^ Kenrick & Crane 1997, pp. 33–39.

- ^ Gowik & Westhoff 2010, pp. 56–63.

- ^ a b Benderoth et al. 2006, pp. 9118–9123.

- ^ Jeffreys 2005, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Mann 1987, pp. 186–187.

- ^ University of Maryland Medical Center 2011.

- ^ Densmore 1974.

- ^ McCutcheon et al. 1992.

- ^ Klemm et al. 2005.

- ^ Scharlemann & Laurance 2008, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Washington Post 18 Aug 2015.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, p. 794.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 786–818.

- ^ a b TeachEthnobotany (2012-06-12), Cultivation of peyote by Native Americans: Past, present and future, archived from the original on 2021-10-28, retrieved 2016-05-05

- ^ Burrows 1990, pp. 1–73.

- ^ Addelson 2003.

- ^ Grime & Hodgson 1987, pp. 283–295.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 819–848.

- ^ Herrera & Pellmyr 2002, pp. 211–235.

- ^ Proctor & Yeo 1973, p. 479.

- ^ Herrera & Pellmyr 2002, pp. 157–185.

- ^ Herrera & Pellmyr 2002, pp. 185–210.

- ^ Bennett & Willis 2001, pp. 5–32.

- ^ Beerling, Osborne & Chaloner 2001, pp. 287–394.

- ^ Björn et al. 1999, pp. 449–454.

- ^ Ben-Menahem 2009, pp. 5369–5370.

- ^ Ben-Menahem 2009, p. 5369.

- ^ Stace 2010b, pp. 629–633.

- ^ Hancock 2004, pp. 190–196.

- ^ Sobotka, Sáková & Curn 2000, pp. 103–112.

- ^ Renner & Ricklefs 1995, pp. 596–606.

- ^ Porley & Hodgetts 2005, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Darwin, C. R. 1878. The effects of cross and self fertilisation in the vegetable kingdom. London: John Murray". darwin-online.org.uk

- ^ Savidan 2000, pp. 13–86.

- ^ a b Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 495–496.

- ^ Morgensen 1996, pp. 383–384.

- ^ Arabidopsis Genome Initiative 2000, pp. 796–815.

- ^ Devos & Gale 2000.

- ^ University of California-Davis 2012.

- ^ Russin et al. 1996, pp. 645–658.

- ^ Rochaix, Goldschmidt-Clermont & Merchant 1998, p. 550.

- ^ Glynn et al. 2007, pp. 451–461.

- ^ Possingham & Rose 1976, pp. 295–305.

- ^ Sun et al. 2002, pp. 95–100.

- ^ Heinhorst & Cannon 1993, pp. 1–9.

- ^ Schell & Van Montagu 1977, pp. 159–179.

- ^ Bird 2007, pp. 396–398.

- ^ Hunter 2008.

- ^ Spector 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Reik 2007, pp. 425–432.

- ^ Costa & Shaw 2007, pp. 101–106.

- ^ Cone & Vedova 2004.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 552–581.

- ^ Copeland 1938, pp. 383–420.

- ^ Woese et al. 1977, pp. 305–311.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith 2004, pp. 1251–1262.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 617–654.

- ^ Becker & Marin 2009, pp. 999–1004.

- ^ Fairon-Demaret 1996, pp. 217–233.

- ^ Stewart & Rothwell 1993, pp. 279–294.

- ^ Taylor, Taylor & Krings 2009, chapter 13.

- ^ a b Mauseth 2003, pp. 720–750.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 751–785.

- ^ Lee et al. 2011, p. e1002411.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 280–314.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 315–340.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 341–372.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 373–398.

- ^ Mauseth 2012, p. 351.

- ^ Darwin 1880, pp. 129–200.

- ^ Darwin 1880, pp. 449–492.

- ^ Darwin 1880, p. 573.

- ^ Plant Hormones 2013.

- ^ Went & Thimann 1937, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 411–412.

- ^ Sussex 2008, pp. 1189–1198.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 827–830.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 411–413.

- ^ Taiz & Zeiger 2002, pp. 461–492.

- ^ Taiz & Zeiger 2002, pp. 519–538.

- ^ Lin, Zhong & Grierson 2009, pp. 331–336.

- ^ Taiz & Zeiger 2002, pp. 539–558.

- ^ Demole, Lederer & Mercier 1962, pp. 675–685.

- ^ Chini et al. 2007, pp. 666–671.

- ^ Roux 1984, pp. 25–29.

- ^ Raven, Evert & Eichhorn 2005, p. 9.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 433–467.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information 2004.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 62–81.

- ^ López-Bautista, Waters & Chapman 2003, pp. 1715–1718.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 630, 738.

- ^ a b c Campbell et al. 2008, p. 739.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 607–608.

- ^ Lepp 2012.

- ^ a b Campbell et al. 2008, pp. 812–814.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, p. 740.

- ^ a b Mauseth 2003, pp. 185–208.

- ^ Mithila et al. 2003, pp. 408–414.

- ^ Campbell et al. 2008, p. 741.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 114–153.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 154–184.

- ^ Capon 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 209–243.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 244–277.

- ^ Sattler & Jeune 1992, pp. 249–269.

- ^ Lilburn et al. 2006.

- ^ McNeill et al. 2011, p. Preamble, para. 7.

- ^ a b Mauseth 2003, pp. 528–551.

- ^ Mauseth 2003, pp. 528–555.

- ^ International Association for Plant Taxonomy 2006.

- ^ Silyn-Roberts 2000, p. 198.

- ^ Mauseth 2012, pp. 438–444.

- ^ Mauseth 2012, pp. 446–449.

- ^ Anderson 2001, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Mauseth 2012, pp. 442–450.

- ^ Stace 2010a, p. 104.

- ^ Mauseth 2012, p. 453.

- ^ Chase et al. 2003, pp. 399–436.

- ^ Capon 2005, p. 223.

- ^ Morton 1981, pp. 459–459.

- ^ Lindley 1848.

- ^ Simpson 2010.

Sources

[edit]- Acharya, Deepak; Anshu, Shrivastava (2008). Indigenous Herbal Medicines: Tribal Formulations and Traditional Herbal Practices. Jaipur, India: Aavishkar Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7910-252-7.

- Addelson, Barbara (December 2003). "Natural Science Institute in Botany and Ecology for Elementary Teachers". Botanical Gardens Conservation International. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- Anderson, Edward F. (2001). The Cactus Family. Pentland, OR: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-498-5.

- Armstrong, G.A.; Hearst, J.E. (1996). "Carotenoids 2: Genetics and Molecular Biology of Carotenoid Pigment Biosynthesis". FASEB J. 10 (2): 228–237. doi:10.1096/fasebj.10.2.8641556. PMID 8641556. S2CID 22385652.

- Becker, Burkhard; Marin, Birger (2009). "Streptophyte Algae and the Origin of Embryophytes". Annals of Botany. 103 (7): 999–1004. doi:10.1093/aob/mcp044. PMC 2707909. PMID 19273476.

- Beerling, D.J.; Osborne, C.P.; Chaloner, W.G. (2001). "Evolution of Leaf-form in Land Plants Linked to Atmospheric CO2 Decline in the Late Palaeozoic Era" (PDF). Nature. 410 (6826): 352–354. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..352B. doi:10.1038/35066546. PMID 11268207. S2CID 4386118. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-09-20. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- Benderoth, Markus; Textor, Susanne; Windsor, Aaron J.; Mitchell-Olds, Thomas; Gershenzon, Jonathan; Kroymann, Juergen (June 2006). "Positive Selection Driving Diversification in Plant Secondary Metabolism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (24): 9118–9123. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.9118B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601738103. JSTOR 30051907. PMC 1482576. PMID 16754868.

- Ben-Menahem, Ari (2009). Historical Encyclopedia of Natural and Mathematical Sciences. Vol. 1. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-68831-0.

- Bennett, Charles E.; Hammond, William A. (1902). The Characters of Theophrastus – Introduction. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- Bennett, K.D.; Willis, K.J. (2001). "Pollen". In Smol, John P.; Birks, H. John B. (eds.). Tracking Environmental Change Using Lake Sediments. Vol. 3: Terrestrial, Algal, and Siliceous Indicators. Dordrecht, Germany: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Bird, Adrian (May 2007). "Perceptions of Epigenetics". Nature. 447 (7143): 396–398. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..396B. doi:10.1038/nature05913. PMID 17522671. S2CID 4357965.

- Björn, L.O.; Callaghan, T.V.; Gehrke, C.; Johanson, U.; Sonesson, M. (November 1999). "Ozone Depletion, Ultraviolet Radiation and Plant Life". Chemosphere – Global Change Science. 1 (4): 449–454. Bibcode:1999ChGCS...1..449B. doi:10.1016/S1465-9972(99)00038-0.

- Bold, H.C. (1977). The Plant Kingdom (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-680389-8.

- Braselton, J.P. (2013). "What is Plant Biology?". Ohio University. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- Burger, William C. (2013). "Angiosperm Origins: A Monocots-First Scenario". Chicago: The Field Museum. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- Burrows, W.J. (1990). Processes of Vegetation Change. London: Unwin Hyman. ISBN 978-0-04-580013-1.

- Butz, Stephen D. (2007). Science of Earth Systems (2 ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4180-4122-9.

- Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B.; Urry, Lisa Andrea; Cain, Michael L.; Wasserman, Steven Alexander; Minorsky, Peter V.; Jackson, Robert Bradley (2008). Biology (8 ed.). San Francisco: Pearson – Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-321-54325-7.

- de Candolle, Alphonse (2006). Origin of Cultivated Plants. Glacier National Park, MT: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4286-0946-4.

- Capon, Brian (2005). Botany for Gardeners (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Timber Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88192-655-2.

- Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2004). "Only Six Kingdoms of Life" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 271 (1545): 1251–1262. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2705. PMC 1691724. PMID 15306349. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-01-10. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Chaffey, Nigel (2007). "Esau's Plant Anatomy, Meristems, Cells, and Tissues of the Plant Body: their Structure, Function, and Development". Annals of Botany. 99 (4): 785–786. doi:10.1093/aob/mcm015. PMC 2802946.

- Chapman, Jasmin; Horsfall, Peter; O'Brien, Pat; Murphy, Jan; MacDonald, Averil (2001). Science Web. Cheltenham, UK: Nelson Thornes. ISBN 978-0-17-438746-6.

- Chase, Mark W.; Bremer, Birgitta; Bremer, Kåre; Reveal, James L.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Soltis, Pamela S.; Stevens, Peter S. (2003). "An Update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group Classification for the Orders and Families of Flowering Plants: APG II" (PDF). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 141 (4): 399–436. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-04-01.

- Chini, A.; Fonseca, S.; Fernández, G.; Adie, B.; Chico, J.M.; Lorenzo, O.; García-Casado, G.; López-Vidriero, I.; Lozano, F.M.; Ponce, M.R.; Micol, J.L.; Solano, R. (2007). "The JAZ Family of Repressors is the Missing Link in Jasmonate Signaling". Nature. 448 (7154): 666–671. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..666C. doi:10.1038/nature06006. PMID 17637675. S2CID 4383741.

- Cocking, Edward C. (October 18, 1993). "Obituary: Professor F. C. Steward". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- Cone, Karen C.; Vedova, Chris B. Della (2004-06-01). "Paramutation: The Chromatin Connection". The Plant Cell. 16 (6): 1358–1364. Bibcode:2004PlanC..16.1358D. doi:10.1105/tpc.160630. ISSN 1040-4651. PMC 490031. PMID 15178748.

- Copeland, Herbert Faulkner (1938). "The Kingdoms of Organisms". Quarterly Review of Biology. 13 (4): 383–420. doi:10.1086/394568. S2CID 84634277.

- Costa, Silvia; Shaw, Peter (March 2007). "'Open Minded' Cells: How Cells Can Change Fate" (PDF). Trends in Cell Biology. 17 (3): 101–106. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.005. PMID 17194589. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-15.

- Cousens, Roger; Mortimer, Martin (1995). Dynamics of Weed Populations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-49969-9. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- Dallal, Ahmad (2010). Islam, Science, and the Challenge of History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15911-0. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- Darwin, Charles (1880). The Power of Movement in Plants (PDF). London: Murray. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2013-07-14.

- Demole, E.; Lederer, E.; Mercier, D. (1962). "Isolement et détermination de la structure du jasmonate de méthyle, constituant odorant caractéristique de l'essence de jasmin isolement et détermination de la structure du jasmonate de méthyle, constituant odorant caractéristique de l'essence de jasmin". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 45 (2): 675–685. doi:10.1002/hlca.19620450233.

- Densmore, Frances (1974). How Indians Use Wild Plants for Food, Medicine, and Crafts. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-13110-8.

- Devos, Katrien M.; Gale, M.D. (May 2000). "Genome Relationships: The Grass Model in Current Research". The Plant Cell. 12 (5): 637–646. doi:10.2307/3870991. JSTOR 3870991. PMC 139917. PMID 10810140. Archived from the original on 2008-06-07. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- Ehrhardt, D.W.; Frommer, W.B. (February 2012). "New Technologies for 21st Century Plant Science". The Plant Cell. 24 (2): 374–394. Bibcode:2012PlanC..24..374E. doi:10.1105/tpc.111.093302. PMC 3315222. PMID 22366161.

- Ereshefsky, Marc (1997). "The Evolution of the Linnaean Hierarchy". Biology and Philosophy. 12 (4): 493–519. doi:10.1023/A:1006556627052. S2CID 83251018.

- Ferro, Myriam; Salvi, Daniel; Rivière-Rolland, Hélène; Vermat, Thierry; et al. (20 August 2002). "Integral Membrane Proteins of the Chloroplast Envelope: Identification and Subcellular Localization of New Transporters". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (17): 11487–11492. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9911487F. doi:10.1073/pnas.172390399. PMC 123283. PMID 12177442.

- Fairon-Demaret, Muriel (October 1996). "Dorinnotheca streelii Fairon-Demaret, gen. et sp. nov., a New Early Seed Plant From the Upper Famennian of Belgium". Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 93 (1–4): 217–233. Bibcode:1996RPaPa..93..217F. doi:10.1016/0034-6667(95)00127-1.

- Finney, D.J. (November 1995). "Frank Yates 12 May 1902 – 17 June 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 41: 554–573. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1995.0033. JSTOR 770162. S2CID 26871863.

- Floros, John D.; Newsome, Rosetta; Fisher, William (2010). "Feeding the World Today and Tomorrow: The Importance of Food Science and Technology" (PDF). Institute of Food Technologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- Fry, S.C. (1989). "The Structure and Functions of Xyloglucan". Journal of Experimental Biology. 40 (1): 1. Bibcode:1989JEBot..40....1F. doi:10.1093/jxb/40.1.1.

- Gordh, Gordon; Headrick, D.H. (2001). A Dictionary of Entomology. Cambridge, MA: CABI Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85199-291-4. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- Gray, Asa; Sargent, Charles (1889). Scientific Papers of Asa Gray: Selected by Charles Sprague Sargent. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- Greene, Edward Lee (1909). Landmarks of botanical history: a study of certain epochs in the development of the science of botany: part 1, Prior to 1562 A.D. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- Glynn, Jonathan M.; Miyagishima, Shin-ya; Yoder, David W.; Osteryoung, Katherine W.; Vitha, Stanislav (May 1, 2007). "Chloroplast Division". Traffic. 8 (5): 451–461. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00545.x. PMID 17451550. S2CID 2808844.

- Gowik, U.; Westhoff, P. (2010). "The Path from C3 to C4 Photosynthesis". Plant Physiology. 155 (1): 56–63. doi:10.1104/pp.110.165308. PMC 3075750. PMID 20940348.