Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fox hunting

View on Wikipedia

Fox hunting is an activity involving the tracking, chase and, if caught, the killing of a fox, normally a red fox, by trained foxhounds or other scent hounds. A group of unarmed followers, led by a "master of foxhounds" (or "master of hounds"), follow the hounds on foot or on horseback.[1]

Fox hunting with hounds, as a formalised activity, originated in England in the sixteenth century, in a form very similar to that practised until February 2005, when a law banning the activity in England and Wales came into force.[2] A ban on hunting in Scotland had been passed in 2002, but it continues to be within the law in Northern Ireland and several other jurisdictions, including Australia, Canada, France, Ireland and the United States.[3][4]

The sport is controversial, particularly in the United Kingdom. Proponents of fox hunting view it as an important part of rural culture and useful for reasons of conservation and pest control,[5][6][7][better source needed] while opponents argue it is cruel and unnecessary.[8]

History

[edit]The use of scenthounds to track prey dates back to Assyrian, Babylonian, and ancient Egyptian times, and was known as venery.[9]

Europe

[edit]

Many Greek- and Roman-influenced countries have long traditions of hunting with hounds. Hunting with Agassaei [d] hounds was popular in Celtic Britain, even before the Romans arrived, introducing the Castorian and Fulpine hound breeds which they used to hunt.[10] Norman hunting traditions were brought to Britain when William the Conqueror arrived, along with the Gascon and Talbot hounds.

Foxes were referred to as beasts of the chase by medieval times, along with the red deer (hart & hind), martens, and roes,[11] but the earliest known attempt to hunt a fox with hounds was in Norfolk, England, in 1534, where farmers began chasing foxes down with their dogs for the purpose of pest control.[10] The last wolf in England was killed in the late 15th century during the reign of Henry VII, leaving the English fox with no threat from larger predators. The first use of packs specifically trained to hunt foxes was in the late 1600s, with the oldest fox hunt being, probably, the Bilsdale in Yorkshire.[12]

By the end of the seventeenth century, deer hunting was in decline. The inclosure acts brought fences to separate formerly open land into many smaller fields, deer forests were being cut down, and arable land was increasing.[13] With the onset of the Industrial Revolution, people began to move out of the country and into towns and cities to find work. Roads, railway lines, and canals all split hunting countries,[14] but at the same time they made hunting accessible to more people. Shotguns were improved during the nineteenth century and the shooting of gamebirds became more popular.[13] Fox hunting developed further in the eighteenth century when Hugo Meynell developed breeds of hound and horse to address the new geography of rural England.[13]

In Germany, hunting with hounds (which tended to be deer or boar hunting) was first banned on the initiative of Hermann Göring on 3 July 1934.[15] In 1939, the ban was extended to cover Austria after Germany's annexation of the country. Bernd Ergert, the director of Germany's hunting museum in Munich, said of the ban, "The aristocrats were understandably furious, but they could do nothing about the ban given the totalitarian nature of the regime."[15]

United States

[edit]According to the Masters of Foxhounds Association of America, Englishman Robert Brooke was the first man to import hunting hounds to what is now the United States, bringing his pack of foxhounds to Maryland in 1650, along with his horses.[16] Also around this time, numbers of European red foxes were introduced into the Eastern seaboard of North America for hunting.[17][18] The first organised hunt for the benefit of a group (rather than a single patron) was started by Thomas, sixth Lord Fairfax in 1747.[16] In the United States, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson both kept packs of foxhounds before and after the American Revolutionary War.[19][20]

Australia

[edit]In Australia, the European red fox was introduced solely for the purpose of fox hunting in 1855.[21] Native animal populations have been very badly affected, with the extinction of at least 10 species attributed to the spread of foxes.[21] Fox hunting with hounds is mainly practised in the east of Australia. In the state of Victoria there are thirteen hunts, with more than 1000 members between them.[22] Fox hunting with hounds results in around 650 foxes being killed annually in Victoria,[22] compared with over 90,000 shot over a similar period in response to a State government bounty.[23] The Adelaide Hunt Club traces its origins to 1840, just a few years after the colonization of South Australia.

Current status

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]

Fox hunting is prohibited in Great Britain by the Protection of Wild Mammals (Scotland) Act 2002 and the Hunting Act 2004 (England and Wales), passed under the ministry of Tony Blair, but remains legal in Northern Ireland.[24][25] The passing of the Hunting Act was notable in that it was implemented through the use of the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949, after the House of Lords refused to pass the legislation, despite the Commons passing it by a majority of 356 to 166.[26]

After the ban on fox hunting, hunts in Great Britain switched to legal alternatives, such as drag hunting and trail hunting.[27][28] The Hunting Act 2004 also permits some previously unusual forms of hunting wild mammals with dogs to continue, such as "hunting... for the purpose of enabling a bird of prey to hunt the wild mammal".[29]

Opponents of hunting, such as the League Against Cruel Sports, claim that some of these alternatives are a smokescreen for illegal hunting or a means of circumventing the ban.[30] Hunting support group Countryside Alliance said in 2006 that there was anecdotal evidence that the number of foxes killed by hunts (unintentionally) and farmers had increased since the Hunting Act came into force, both by the hunts (through lawful methods) and landowners, and that more people were hunting with hounds (although killing foxes had become illegal).[31]

Tony Blair wrote in A Journey, his memoirs published in 2010, that the Hunting Act of 2004 is 'one of the domestic legislative measures I most regret'.[32]

United States

[edit]In America, fox hunting is also called "fox chasing", as it is the practice of many hunts not to actually kill the fox (the red fox is not regarded as a significant pest).[16] Some hunts may go without catching a fox for several seasons, despite chasing two or more foxes in a single day's hunting.[33] Foxes are not pursued once they have "gone to ground" (hidden in a hole). American fox hunters undertake stewardship of the land, and endeavour to maintain fox populations and habitats as much as possible.[33] In many areas of the eastern United States the coyote, a natural predator of the red and grey fox, is becoming more prevalent and threatens fox populations in a hunt's given territory. In some areas, coyote are considered fair game when hunting with foxhounds, even if they are not the intended species being hunted.

In 2013, the Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America listed 163 registered packs in the US and Canada.[34] This number does not include non-registered (also known as "farmer" or "outlaw") packs.[33] Baily's Hunting Directory Lists 163 foxhound or draghound packs in the US and 11 in Canada[35] In some arid parts of the Western United States, where foxes in general are more difficult to locate, coyotes[36] are hunted and, in some cases, bobcats.[37]

Other countries

[edit]

The other main countries in which organized fox hunting with hounds is practised are Ireland (which has 41 registered packs),[38] Australia, France (this hunting practice is also used for other animals such as deer, wild boar, fox, hare or rabbit), Canada and Italy. There is one pack of foxhounds in Portugal, and one in India. Although there are 32 packs for the hunting of foxes in France, hunting tends to take place mainly on a small scale and on foot, with mounted hunts tending to hunt red or roe deer, or wild boar.[39]

In Portugal fox hunting is permitted (Decree-Law no. 202/2004) but there have been popular protests[40] and initiatives to abolish it. A petition[41] was handed over to the Assembly of the Republic[42] on 18 May 2017 and the parliamentary hearing held in 2018.[43]

In Canada, the Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America lists seven registered hunt clubs in the province of Ontario, one in Quebec, and one in Nova Scotia.[44] Ontario issues licenses to registered hunt clubs, authorizing its members to pursue, chase or search for fox,[45] although the primary target of the hunts is coyotes.[46]

Quarry animals

[edit]Red fox

[edit]

The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is the normal prey animal of a fox hunt in the US and Europe. A small omnivorous predator,[47] the fox lives in burrows called earths,[48] and is predominantly active around twilight (making it a crepuscular animal).[49] Adult foxes tend to range around an area of between 5 and 15 km2 (2 and 6 square miles) in good terrain, although in poor terrain, their range can be as much as 20 km2 (7+3⁄4 square miles).[49] The red fox can run at up to 48 km/h (30 mph).[49] The fox is also variously known as a Tod (old English word for fox),[50] Reynard (the name of an anthropomorphic character in European literature from the twelfth century),[51] or Charlie (named for the Whig politician Charles James Fox).[52] American red foxes tend to be larger than European forms, but according to foxhunters' accounts, they have less cunning, vigour and endurance in the chase than European foxes.[53]

Coyote, grey fox, and other quarry

[edit]

Other species than the red fox may be the quarry for hounds in some areas. The choice of quarry depends on the region and numbers available.[16] The coyote (Canis latrans) is a significant quarry for many Hunts in North America, particularly in the west and southwest, where there are large open spaces.[16] The coyote is an indigenous predator that did not range east of the Mississippi River until the latter half of the twentieth century.[54] The coyote is faster than a fox, running at 65 km/h (40 mph) and also wider ranging, with a territory of up to 283 km2 (109 square miles),[55] so a much larger hunt territory is required to chase it. However, coyotes tend to be less challenging intellectually, as they offer a straight line hunt instead of the convoluted fox line. Coyotes can be challenging opponents for the dogs in physical confrontations, despite the size advantage of a large dog. Coyotes have larger canine teeth and are generally more practised in hostile encounters.[56]

The grey fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), a distant relative of the European red fox, is also hunted in North America.[16] It is an adept climber of trees, making it harder to hunt with hounds.[57] The scent of the gray fox is not as strong as that of the red, therefore more time is needed for the hounds to take the scent. Unlike the red fox which, during the chase, will run far ahead from the pack, the gray fox will speed toward heavy brush, thus making it more difficult to pursue. Also unlike the red fox, which occurs more prominently in the northern United States, the more southern gray fox is rarely hunted on horseback, due to its densely covered habitat preferences.

Hunts in the southern United States sometimes pursue the bobcat (Lynx rufus).[16] In countries such as India, and in other areas formerly under British influence, such as Iraq, the golden jackal (Canis aureus) is often the quarry.[58][59] During the British Raj, British sportsmen in India would hunt jackals on horseback with hounds as a substitute for the fox hunting of their native England. Unlike foxes, golden jackals were documented to be ferociously protective of their pack mates, and could seriously injure hounds.[60][61] Jackals were not hunted often in this manner, as they were slower than foxes and could scarcely outrun greyhounds after 200 yards or 180 m.[62]

Alternatives to hunting live prey

[edit]Following the ban on fox hunting in Great Britain, hunts switched to legal alternatives in order to preserve their traditional practices, although some hunt supporters had previously claimed this would be impossible and that hound packs would have to be destroyed.[63]

Most hunts turned, primarily, to trail hunting,[27][28] which anti-hunt organisations claim is just a smokescreen for illegal hunting.[64] Some anti-hunting campaigners have urged hunts to switch to the established sport of drag hunting instead, as this involves significantly less risk of wild animals being accidentally caught and killed.[65][66][67]

Trail hunting

[edit]A controversial[68] alternative to hunting animals with hounds. A trail of animal urine (most commonly fox) is laid in advance of the 'hunt', and then tracked by the hound pack and a group of followers; on foot, horseback, or both. Because the trail is laid using animal urine, and in areas where such animals naturally occur, hounds often pick up the scent of live animals; sometimes resulting in them being caught and killed.[69]

Drag hunting

[edit]An established sport which dates back to the 19th century. Hounds follow an artificial scent, usually aniseed, laid along a set route which is already known to the huntsmen.[70] A drag hunt course is set in a similar manner to a cross country course, following a route over jumps and obstacles. Because it is predetermined, the route can be tailored to keep hounds away from sensitive areas known to be populated by animals which could be confused for prey.[71]

Hound trailing

[edit]Similar to drag hunting, but in the form of a race; usually of around 15 km (10 miles) in length.[70] Unlike other forms of hunting, the hounds are not followed by humans.

Clean boot hunting

[edit]Clean boot hunting uses packs of bloodhounds to follow the natural trail of a human's scent.[70]

Animals of the hunt

[edit]Hounds and other dogs

[edit]

Fox hunting is usually undertaken with a pack of scent hounds,[1] and, in most cases, these are specially bred foxhounds.[72] These dogs are trained to pursue the fox based on its scent. The two main types of foxhound are the English Foxhound[73] and the American Foxhound.[74] It is possible to use a sight hound such as a Greyhound or lurcher to pursue foxes,[75] though this practice is not common in organised hunting, and these dogs are more often used for coursing animals such as hares.[76] There is also one pack of beagles in Virginia that hunt foxes. They are unique in that they are the only hunting beagle pack in the US to be followed on horseback. English Foxhounds are also used for hunting mink.

Hunts may also use terriers to flush or kill foxes that are hiding underground,[1] as they are small enough to pursue the fox through narrow earth passages. This is not practised in the United States, as once the fox has gone to ground and is accounted for by the hounds, it is left alone.

Horses

[edit]

The horses, called "field hunters" or hunters, ridden by members of the field, are a prominent feature of many hunts, although others are conducted on foot (and those hunts with a field of mounted riders will also have foot followers). Horses on hunts can range from specially bred and trained field hunters to casual hunt attendees riding a wide variety of horse and pony types. Draft and Thoroughbred crosses are commonly used as hunters, although purebred Thoroughbreds and horses of many different breeds are also used.

Some hunts with unique territories favour certain traits in field hunters; for example, when hunting coyote in the western US, a faster horse with more stamina is required to keep up, as coyotes are faster than foxes and inhabit larger territories. Hunters must be well-mannered, have the athletic ability to clear large obstacles such as wide ditches, tall fences, and rock walls, and have the stamina to keep up with the hounds. In English foxhunting, the horses are often a cross of half or a quarter Irish Draught and the remainder English thoroughbred.[77]

Dependent on terrain, and to accommodate different levels of ability, hunts generally have alternative routes that do not involve jumping. The field may be divided into two groups, with one group, the First Field, that takes a more direct but demanding route that involves jumps over obstacles[78] while another group, the Second Field (also called Hilltoppers or Gaters), takes longer but less challenging routes that utilise gates or other types of access on the flat.[78][79]

Birds of prey

[edit]In Great Britain, since the introduction of the hunting ban, a number of hunts have employed falconers to bring birds of prey to the hunt, due to the exemption in the Hunting Act for falconry.[80] Many experts, such as the Hawk Board, deny that any bird of prey can reasonably be used in the British countryside to kill a fox which has been flushed by (and is being chased by) a pack of hounds.[81]

Procedure

[edit]

Main hunting season

[edit]

The main hunting season usually begins in early November, in the northern hemisphere,[14] and in May in the southern hemisphere.

A hunt begins when the hounds are put, or cast, into a patch of woods or brush where foxes are known to lay up during daylight hours; known as a covert (pronounced "cover"). If the pack manages to pick up the scent of a fox, they will track it for as long as they are able. Scenting can be affected by temperature, humidity, and other factors. If the hounds lose the scent, a check occurs. [82]

The hounds pursue the trail of the fox and the riders follow, by the most direct route possible. This may involve very athletic skill on the part of horse and rider, and fox hunting has given birth to some traditional equestrian sports including steeplechase[83] and point-to-point racing.[84]

The hunt continues until either the fox goes to ground (evades the hounds and takes refuge in a burrow or den) or is overtaken and usually killed by the hounds.

Social rituals are important to hunts, although many have fallen into disuse. One of the most notable was the act of blooding. In this ceremony, the master or huntsman would smear the blood of the fox onto the cheeks or forehead of a newly initiated hunt-follower, often a young child.[85] Another practice of some hunts was to cut off the fox's tail (brush), the feet (pads) and the head (mask) as trophies, with the carcass then thrown to the hounds.[85] Both of these practices were widely abandoned during the nineteenth century, although isolated cases may still have occurred to the modern day.[85]

Cubbing

[edit]In the autumn of each year, hunts accustom the young hounds, which by now are full-size, but not yet sexually mature, to hunt and kill foxes through the practice of cubbing (also called cub hunting, autumn hunting and entering).[14][86][49] Cubbing also aims to teach hounds to restrict their hunting to foxes, so that they do not hunt other species such as deer or hares.[1][87]

The activity sometimes incorporates the practice of holding up; where hunt supporters, riders and foot followers surround a covert and drive back foxes attempting to escape, before then drawing the covert with the young hounds and some more experienced hounds, allowing them to find and kill foxes within the surrounded covert.[1] A young hound is considered to be entered into the pack once they have successfully joined in a hunt of this fashion. Young hounds which do not show sufficient aptitude may be killed by their owners or drafted to other packs, including minkhound packs.[88]

The Burns Inquiry, established in 1999, reported that an estimated 10,000 fox cubs were killed annually during the cub-hunting season in Great Britain.[89] Cub hunting is now illegal in Great Britain,[90] although anti-hunt associations maintain that the practice continues.[91][need quotation to verify]

People

[edit]Hunt staff and officials

[edit]

Published in Vanity Fair (1906)

As a social ritual, participants in a fox hunt fill specific roles, the most prominent of which is the master, who often number more than one and then are called masters or joint masters. These individuals typically take much of the financial responsibility for the overall management of the sporting activities of the hunt, along with the care and breeding of the hunt's foxhounds as well as control and direction of its paid staff.

- The Master of Foxhounds (who use the post-nominal (and may also be called) MFH[92][93][94]) or Joint Master of Foxhounds operates the sporting activities of the hunt, maintains the kennels, works with (and sometimes is) the huntsman, and spends the money raised by the hunt club. (Often the master or joint masters are the largest of financial contributors to the hunt.) The master will have the final say over all matters in the field.[95]

- Honorary secretaries are volunteers (usually one or two) who look after the administration of the hunt.[95]

- The Treasurer collects the cap (money) from guest riders and manages the hunt's finances.[95]

- A kennelman looks after hounds in kennels, assuring that all tasks are completed when pack and staff return from hunting.[96]

- The huntsman, who may be a professional, is responsible for directing the hounds. The Huntsman usually carries a horn to communicate to the hounds, followers and whippers in.[95] Some huntsmen also fill the role of kennelman (and are therefore known as the kennel huntsman). In some hunts the master is also the huntsman.

- Whippers-in (or "Whips") are assistants to the huntsman. Their main job is to keep the pack all together, especially to prevent the hounds from straying or 'riotting', which term refers to the hunting of animals other than the hunted fox or trail line. To help them to control the pack, they carry hunting whips (and in the United States they sometimes also carry .22 revolvers loaded with snake shot or blanks.)[95] The role of whipper-in in hunts has inspired parliamentary systems (including the Westminster System and the US Congress) to use whip for a member who enforces party discipline and ensures the attendance of other members at important votes.[97]

- Terrier man— Carries out fox control. Most hunts where the object is to kill the fox will employ a terrier man, whose job it is to control the terriers which may be used underground to corner or flush the fox. Often voluntary terrier men will follow the hunt as well. In the UK and Ireland, they often ride quadbikes with their terriers in boxes on their bikes.[98]

In addition to members of the hunt staff, a committee may run the Hunt Supporters Club to organise fundraising and social events and in the United States many hunts are incorporated and have parallel lines of leadership.

The United Kingdom, Ireland, and the United States each have a Masters of Foxhounds Association (MFHA) which consists of current and past masters of foxhounds. This is the governing body for all foxhound packs and deals with disputes about boundaries between hunts, as well as regulating the activity.

Attire

[edit]

Mounted hunt followers typically wear traditional hunting attire. A prominent feature of hunts operating during the formal hunt season (usually November to March in the northern hemisphere) is hunt members wearing 'colours'. This attire usually consists of the traditional red coats worn by huntsmen, masters, former masters, whippers-in (regardless of sex), other hunt staff members and male members who have been invited by masters to wear colours and hunt buttons as a mark of appreciation for their involvement in the organization and running of the hunt.

Since the Hunting Act in England and Wales, only Masters and Hunt Servants tend to wear red coats or the hunt livery whilst out hunting. Gentleman subscribers tend to wear black coats, with or without hunt buttons. In some countries, women generally wear coloured collars on their black or navy coats. These help them stand out from the rest of the field.

The traditional red coats are often misleadingly called "pinks". Various theories about the derivation of this term have been given, ranging from the colour of a weathered scarlet coat to the name of a purportedly famous tailor.[100][101]

Some hunts, including most harrier and beagle packs, wear green rather than red jackets, and some hunts wear other colours such as mustard. The colour of breeches vary from hunt to hunt and are generally of one colour, though two or three colours throughout the year may be permitted.[102] Riding boots are generally English dress boots (no laces). For the men they are black with brown leather tops (called tan tops), and for the women, black with a patent black leather top of similar proportion to the men.[102] Additionally, the number of buttons is significant. The Master wears a scarlet coat with four brass buttons while the huntsman and other professional staff wear five. Amateur whippers-in also wear four buttons.

Another differentiation in dress between the amateur and professional staff is found in the ribbons at the back of the hunt cap. The professional staff wear their hat ribbons down, while amateur staff and members of the field wear their ribbons up.[103]

Those members not entitled to wear colours, dress in a black hunt coat and unadorned black buttons for both men and women, generally with pale breeches. Boots are all English dress boots and have no other distinctive look.[102] Some hunts also further restrict the wear of formal attire to weekends and holidays and wear ratcatcher (tweed jacket and tan breeches), at all other times.

Other members of the mounted field follow strict rules of clothing etiquette. For example, for some hunts, those under eighteen (or sixteen in some cases) will wear ratcatcher all season. Those over eighteen (or in the case of some hunts, all followers regardless of age) will wear ratcatcher during autumn hunting from late August until the Opening Meet, normally around 1 November. From the Opening Meet they will switch to formal hunting attire where entitled members will wear scarlet and the rest black or navy.

The highest honour is to be awarded the hunt button by the Hunt Master. This sometimes means one can then wear scarlet if male, or the hunt collar if female (colour varies from hunt to hunt) and buttons with the hunt crest on them. For non-mounted packs or non-mounted members where formal hunt uniform is not worn, the buttons are sometimes worn on a waistcoat. All members of the mounted field should carry a hunting whip (it should not be called a crop). These have a horn handle at the top and a long leather lash (2–3 yards or 2–2.5 m) ending in a piece of coloured cord. Generally all hunting whips are brown, except those of Hunt Servants, whose whips are white.

Controversy

[edit]The nature of fox hunting, including the killing of the quarry animal, the pursuit's strong associations with tradition and social class, and its practice for sport have made it a source of great controversy within the United Kingdom. In December 1999, the then Home Secretary, Jack Straw MP, announced the establishment of a Government inquiry (the Burns Inquiry) into hunting with dogs, to be chaired by the retired senior civil servant Lord Burns. The inquiry was to examine the practical aspects of different types of hunting with dogs and its impact, how any ban might be implemented and the consequences of any such ban.[104]

Amongst its findings, the Burns Inquiry committee analysed opposition to hunting in the UK and reported that:

There are those who have a moral objection to hunting and who are fundamentally opposed to the idea of people gaining pleasure from what they regard as the causing of unnecessary suffering. There are also those who perceive hunting as representing a divisive social class system. Others, as we note below, resent the hunt trespassing on their land, especially when they have been told they are not welcome. They worry about the welfare of the pets and animals and the difficulty of moving around the roads where they live on hunt days. Finally there are those who are concerned about damage to the countryside and other animals, particularly badgers and otters.[105]

In a later debate in the House of Lords, the inquiry chairman, Lord Burns, also stated that "Naturally, people ask whether we were implying that hunting is cruel... The short answer to that question is no. There was not sufficient verifiable evidence or data safely to reach views about cruelty. It is a complex area."[106]

Anti-hunting activists who choose to take action in opposing fox hunting can do so through lawful means, such as campaigning for fox hunting legislation and monitoring hunts for cruelty. Some use unlawful means.[107] Main anti-hunting campaign organisations include the RSPCA and the League Against Cruel Sports. In 2001, the RSPCA took high court action to prevent pro-hunt activists joining in large numbers to change the society's policy in opposing hunting.[108]

Outside of campaigning, some activists choose to engage in direct intervention such as sabotage of the hunt.[109] Hunt sabotage is unlawful in a majority of the United States, and some tactics used in it (such as trespass and criminal damage) are offences there and in other countries.[110]

Fox hunting with hounds has been happening in Europe since at least the sixteenth century, and strong traditions have built up around the activity, as have related businesses, rural activities, and hierarchies. For this reason, there are large numbers of people who support fox hunting and this can be for a variety of reasons.[5]

Pest control

[edit]The fox is referred to as vermin in some countries. Some farmers fear the loss of their smaller livestock,[66] while others consider them an ally in controlling rabbits, voles, and other rodents, which eat crops.[111] A key reason for dislike of the fox by pastoral farmers is their tendency to commit acts of surplus killing toward animals such as chickens, since having killed many they eat only one.[112][113] Some anti-hunt campaigners maintain that provided it is not disturbed, the fox will remove all of the chickens it kills and conceal them in a safer place.[114]

Opponents of fox hunting claim that the activity is not necessary for fox control, arguing that the fox is not a pest species despite its classification and that hunting does not and cannot make a real difference to fox populations.[115] They compare the number of foxes killed in the hunt to the many more killed on the roads. They also argue that wildlife management goals of the hunt can be met more effectively by other methods such as lamping (dazzling a fox with a bright light, then shooting by a competent shooter using an appropriate weapon and load).[116]

There is scientific evidence that fox hunting has no effect on fox populations, at least in Britain, thereby calling into question the idea it is a successful method of culling. In 2001 there was a 1-year nationwide ban on fox-hunting because of an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease. It was found this ban on hunting had no measurable impact on fox numbers in randomly selected areas.[117] Prior to the fox hunting ban in the UK, hounds contributed to the deaths of 6.3% of the 400,000 foxes killed annually.[118]

The hunts claim to provide and maintain a good habitat for foxes and other game,[66] and, in the US, have fostered conservation legislation and put land into conservation easements. Anti-hunting campaigners cite the widespread existence of artificial earths and the historic practice by hunts of introducing foxes, as indicating that hunts do not believe foxes to be pests.[119]

It is also argued that hunting with dogs has the advantage of weeding out old, sick, and weak animals because the strongest and healthiest foxes are those most likely to escape. Therefore, unlike other methods of controlling the fox population, it is argued that hunting with dogs resembles natural selection.[66] The counter-argument is given that hunting cannot kill old foxes because foxes have a natural death rate of 65% per annum.[119]

In Australia, where foxes have played a major role in the decline in the number of species of wild animals, the Government's Department of the Environment and Heritage concluded that "hunting does not seem to have had a significant or lasting impact on fox numbers." Instead, control of foxes relies heavily on shooting, poisoning and fencing.[120]

Economics

[edit]As well as the economic defence of fox hunting that it is necessary to control the population of foxes, lest they cause economic cost to the farmers, it is also argued that fox hunting is a significant economic activity in its own right, providing recreation and jobs for those involved in the hunt and supporting it. The Burns Inquiry identified that between 6,000 and 8,000 full-time jobs depend on hunting in the UK, of which about 700 result from direct hunt employment and 1,500 to 3,000 result from direct employment on hunting-related activities.[1]

Since the ban in the UK, there has been no evidence of significant job losses, and hunts have continued to operate along limited lines, either trail hunting, or claiming to use exemptions in the legislation.[121]

Animal welfare and animal rights

[edit]Many animal welfare groups, campaigners and activists believe that fox hunting is unfair and cruel to animals.[122] They argue that the chase itself causes fear and distress and that the fox is not always killed instantly as is claimed. Animal rights campaigners also object to hunting (including fox hunting), on the grounds that animals should enjoy some basic rights (such as the right to freedom from exploitation and the right to life).[123][124]

In the United States and Canada, pursuing quarry for the purpose of killing is strictly forbidden by the Masters of Foxhounds Association.[16] According to article 2 of the organisation's code:

The sport of fox hunting as it is practised in North America places emphasis on the chase and not the kill. It is inevitable, however, that hounds will at times catch their game. Death is instantaneous. A pack of hounds will account for their quarry by running it to ground, treeing it, or bringing it to bay in some fashion. The Masters of Foxhounds Association has laid down detailed rules to govern the behaviour of Masters of Foxhounds and their packs of hounds.[125]

There are times when a fox that is injured or sick is caught by the pursuing hounds, but hunts say that the occurrence of an actual kill of this is exceptionally rare.[16]

Supporters of hunting maintain that when foxes or other prey (such as coyotes in the western USA) are hunted, the quarry are either killed relatively quickly (instantly or in a matter of seconds) or escapes uninjured. Similarly, they say that the animal rarely endures hours of torment and pursuit by hounds, and research by Oxford University shows that the fox is normally killed after an average of 17 minutes of chase.[122] They further argue that, while hunting with hounds may cause suffering, controlling fox numbers by other means is even more cruel. Depending on the skill of the shooter, the type of firearm used, the availability of good shooting positions and luck, shooting foxes can cause either an instant kill, or lengthy periods of agony for wounded animals which can die of the trauma within hours, or of secondary infection over a period of days or weeks. Research from wildlife hospitals, however, indicates that it is not uncommon for foxes with minor shot wounds to survive. [126] Hunt supporters further say that it is a matter of humanity to kill foxes rather than allow them to suffer malnourishment and mange.[127]

Other methods include the use of snares, trapping and poisoning, all of which also cause considerable distress to the animals concerned, and may affect other species. This was considered in the Burns Inquiry (paras 6.60–11), whose tentative conclusion was that lamping using rifles fitted with telescopic sights, if carried out properly and in appropriate circumstances, had fewer adverse welfare implications than hunting.[1] The committee believed that lamping was not possible without vehicular access, and hence said that the welfare of foxes in upland areas could be affected adversely by a ban on hunting with hounds, unless dogs could be used to flush foxes from cover (as is permitted in the Hunting Act 2004).

Some opponents of hunting criticise the fact that the animal suffering in fox hunting takes place for sport, citing either that this makes such suffering unnecessary and therefore cruel, or else that killing or causing suffering for sport is immoral.[128] The Court of Appeal, in considering the British Hunting Act, determined that the legislative aim of the Hunting Act was "a composite one of preventing or reducing unnecessary suffering to wild mammals, overlaid by a moral viewpoint that causing suffering to animals for sport is unethical."[129]

Anti-hunting campaigners also criticised UK hunts of which the Burns Inquiry estimated that foxhound packs put down around 3,000 hounds, and the hare hunts killed around 900 hounds per year, in each case after the hounds' working life had come to an end.[1][130][131]

In June 2016, three people associated with the South Herefordshire Hunt (UK) were arrested on suspicion of causing suffering to animals in response to claims that live fox cubs were used to train hounds to hunt and kill. The organisation Hunt Investigation Team supported by the League Against Cruel Sports, gained video footage of an individual carrying a fox cub into a large kennel where the hounds can clearly be heard baying. A dead fox was later found in a rubbish bin. The individuals arrested were suspended from Hunt membership.[132] In August, two more people were arrested in connection with the investigation.[133]

Civil liberties

[edit]It is argued by some hunt supporters that no law should curtail the right of a person to do as they wish, so long as it does not harm others.[66] Philosopher Roger Scruton has said, "To criminalise this activity would be to introduce legislation as illiberal as the laws which once deprived Jews and Catholics of political rights, or the laws which outlawed homosexuality".[134] In contrast, liberal philosopher, John Stuart Mill wrote, "The reasons for legal intervention in favour of children apply not less strongly to the case of those unfortunate slaves and victims of the most brutal parts of mankind—the lower animals."[135] The UK's most senior court, the House of Lords, has decided that a ban on hunting, in the form of the Hunting Act 2004, does not contravene the European Convention on Human Rights,[136] as did the European Court of Human Rights.[137]

Trespass

[edit]In its submission to the Burns Inquiry, the League Against Cruel Sports presented evidence of over 1,000 cases of trespass by hunts. These included trespass on railway lines and into private gardens.[1] Trespass can occur as the hounds cannot recognise human-created boundaries they are not allowed to cross, and may therefore follow their quarry wherever it goes unless successfully called off. However, in the United Kingdom, trespass is a largely civil matter when performed accidentally.

Nonetheless, in the UK, the criminal offence of 'aggravated trespass' was introduced in 1994 specifically to address the problems caused to fox hunts and other field sports by hunt saboteurs.[138][139] Hunt saboteurs trespass on private land to monitor or disrupt the hunt, as this is where the hunting activity takes place.[139] For this reason, the hunt saboteur tactics manual presents detailed information on legal issues affecting this activity, especially the Criminal Justice Act.[140] Some hunt monitors also choose to trespass whilst they observe the hunts in progress.[139]

The construction of the law means that hunt saboteurs' behaviour may result in charges of criminal aggravated trespass,[141] rather than the less severe offence of civil trespass.[142] Since the introduction of legislation to restrict hunting with hounds, there has been a level of confusion over the legal status of hunt monitors or saboteurs when trespassing, as if they disrupt the hunt whilst it is not committing an illegal act (as all the hunts claim to be hunting within the law) then they commit an offence; however, if the hunt was conducting an illegal act then the criminal offence of trespass may not have been committed.[139]

Social life and class issues in Britain

[edit]

In Britain, and especially in England and Wales, supporters of fox hunting regard it as a distinctive part of British culture generally, the basis of traditional crafts and a key part of social life in rural areas, an activity and spectacle enjoyed not only by the riders but also by others such as the unmounted pack which may follow along on foot, bicycle or 4×4 vehicles.[5] They see the social aspects of hunting as reflecting the demographics of the area; the Home Counties packs, for example, are very different from those in North Wales and Cumbria, where the hunts are very much the activity of farmers and the working class. The Banwen Miners Hunt is such a working class club, founded in a small Welsh mining village, although its membership now is by no means limited to miners, with a more cosmopolitan make-up.[143]

Oscar Wilde, in his play A Woman of No Importance (1893), once famously described "the English country gentleman galloping after a fox" as "the unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable."[144] Even before the time of Wilde, much of the criticism of fox hunting was couched in terms of social class. The argument was that while more "working class" blood sports such as cock fighting and badger baiting were long ago outlawed,[145][146] fox hunting persists, although this argument can be countered with the fact that hare coursing, a more "working-class" sport, was outlawed at the same time as fox hunting with hounds in England and Wales. The philosopher Roger Scruton has said that the analogy with cockfighting and badger baiting is unfair, because these sports were more cruel and did not involve any element of pest control.[134]

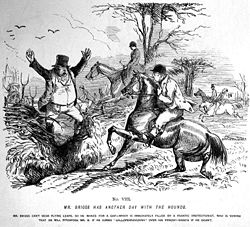

A series of "Mr. Briggs" cartoons by John Leech appeared in the magazine Punch during the 1850s which illustrated class issues.[147] More recently the British anarchist group Class War has argued explicitly for disruption of fox hunts on class warfare grounds and even published a book The Rich at Play examining the subject.[148] Other groups with similar aims, such as "Revolutions per minute" have also published papers which disparage fox hunting on the basis of the social class of its participants.[149]

Opinion polls in the United Kingdom have shown that the population is equally divided as to whether or not the views of hunt objectors are based primarily on class grounds.[150] Some people have pointed to evidence of class bias in the voting patterns in the House of Commons during the voting on the hunting bill between 2000 and 2001, with traditionally working-class Labour members voting the legislation through against the votes of normally middle- and upper-class Conservative members.[151]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Final Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs in England and Wales". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 9 June 2000. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ "Hunt ban forced through Commons". BBC News. 19 November 2004. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- ^ Griffin, Emma (2007). Blood Sport. Yale University Press.

- ^ "Fox hunting worldwide". BBC News. 16 September 1999. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ "Creation and conservation of habitat by foxhunting". Masters of Fox Hounds Association. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "The need for wildlife management". Masters of Fox Hounds Association. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ "The morality of hunting with dogs" (PDF). Campaign to Protect Hunted Animals. Retrieved 13 October 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Aslam, Dilpazier (18 February 2005). "Ten things you didn't know about hunting with hounds". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ a b Aslam, D (18 February 2005). "Ten things you didn't know about hunting with hounds". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "Forest and Chases in England and Wales c. 1000 to c. 1850". St John's College, Oxford. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ^ Jane Ridley, Fox Hunting: a history (HarperCollins, October 1990)

- ^ a b c Birley, D. (1993). Sport and the Making of Britain. Manchester University Press. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-0-7190-3759-7. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ a b c Raymond Carr, English Fox Hunting: A History (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1976)

- ^ a b Harrison, David; Paterson, Tony (22 September 2002). "Thanks to Hitler, hunting with hounds is still verboten". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "History of American Foxhunting". Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America. 2008. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ Presnall, C.C. (1958). "The Present Status of Exotic Mammals in the United States". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 22 (1): 45–50. doi:10.2307/3797296. JSTOR 3797296.

- ^ Churcher, C.S. (1959). "The Specific Status of the New World Red Fox". Journal of Mammalogy. 40 (4): 513–520. doi:10.2307/1376267. JSTOR 1376267.

- ^ "Profile – George Washington". Explore DC. 2001. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ "A short history of foxhunting in Virginia". Freedom Fields Farm. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ a b Eastham, Jaime. "Australia's Noah's Ark springs a leak". Australian Conservation Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ a b "It's the thrill not the kill, they say". The Age. Melbourne. 20 March 2005. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- ^ "Bounty fails to win ground war against foxes". The Age. Melbourne. 5 May 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- ^ Hookham, Mark (15 March 2007). "Hain lambasted over website backing hunting". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- ^ "Northern Ireland bans hare coursing, and fox hunting could be next". 24 June 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "Protesters storm UK parliament". CNN. 16 September 2004. Archived from the original on 18 November 2004. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ a b "What is trail hunting?". thehuntingoffice. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Trail Laying". huntingact.co.uk. 25 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Stephen Moss, The banned rode on: Eighteen months ago hunting was banned. Or was it? from The Guardian dated 7 November 2006, at guardian.co.uk, accessed 29 April 2013

- ^ "What is trail hunting and is it legal?". itv.com. 24 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ "'More foxes dead' since hunt ban". BBC News. 17 February 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Blair regrets hunting ban". Country Life. 1 September 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Smart, Bruce (2004). "9" (PDF). A community of the horse. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2006. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- ^ "Geographical listing of hunts". Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America. 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Directory of Hunts". Baily's Hunting Directory. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Arapahoe Hunt Club History". Arapahoe Hunt Club. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ "Recognized Hunts". Chronicle of the Horse. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ "Welcome to the IMFHA- representing Irish Fox Hunting". The Irish Masters of Foxhounds Association. Archived from the original on 2 February 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "Venerie-the Organisation representing hunting with hounds in France". Venerie. 9 June 2000.

- ^ "Cidadãos organizam manifestação a pedir fim de caça à raposa, "prática cruel e bárbara"". PÚBLICO. 3 March 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ^ "Pelo Fim da Caça à Raposa em Portugal". Petição Pública.

- ^ "Petição No. 324/XIII/2". Parlamento (in Portuguese).

- ^ "Audição Parlamentar No. 59-CAM-XIII". Parlamento (in Portuguese).

- ^ "Hunt Map". Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America. 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997". Ontario.ca. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ O'Connor, Joe (11 December 2018). "Horses, hounds and coyotes — Meet Canada's only woman employed as a huntsman". Financial Post Magazine. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Diet". Derbyshire Fox Rescue. 2006. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ "Peatland Wildlife – The Fox". Northern Ireland Environment and Heritage Service. 2004. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d Fox, David. "Vulpes vulpes (red fox)". University of Michigan – Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Todd". Behind the name. 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 226.

- ^ "Three centuries of hunting foxes". BBC News. 16 September 1999. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Sketches in Natural History: History of the Mammalia. By Charles Knight Published by C. Cox, 1849

- ^ Houben, JM (2004). "Status and management of coyote depredations in the Eastern United States". US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Tokar, Eric. "Canis latrans (coyote)". University of Michigan – Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Coppinger, Ray (2001). Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. New York: Scribner. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-684-85530-1.

- ^ Jansa, Sharon. "Urocyon cirereoargentus (gray fox)". University of Michigan – Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Hurworth hound bound for India". Horse & Hound. Horse and Hound. 24 May 2004. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Unusual features of RAF Habbaniya (Iraq)". RAF Habbaniya Association. Archived from the original on 2 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ An Encyclopaedia of Rural Sports: Or a Complete Account, Historical, Practical, and Descriptive, of Hunting, Shooting, Fishing, Racing, and Other Field Sports and Athletic Amusements of the Present Day, Delabere Pritchett Blaine by Delabere Pritchett Blaine, published by Longman, Orme, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1840

- ^ A monograph of the canidae by St. George Mivart, F.R.S, published by Alere Flammam. 1890

- ^ The Sports Library, Riding, Driving and Kindred Sports by T. F. Dale, published by T.F. Unwin, 1899

- ^ Kallenbach, M (19 March 2002). "Peer warns of a war with countryside". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 5 April 2002. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- ^ "What is trail hunting and is it legal?". www.itv.com. 24 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Salt, H. (1915). "Drag Hunting Verses Stag Hunting". Killing for Sport. Archived from the original on 5 March 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Countryside Alliance (2000). "Submission to the Burns Inquiry". Defra. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ "Drag Hunting". New Forest Drag Hunt. Archived from the original on 9 April 2003. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "Call to ban controversial trail hunting on North Northamptonshire Council land". northantstelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ "The impact of hunting with dogs on wildlife and conservation" (PDF). www.league.org.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Nicholas Goddard and John Martin, "Drag hunting", Encyclopedia of traditional British rural sports, Tony Collins, John Martin and Wray Vamplew (eds), Routledge, Abingdon, 2005, ISBN 0-415-35224-X, p104.

- ^ "What is drag hunting?". North East Cheshire Drag Hunt. 2008. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "English Foxhound History". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "English Foxhound Breed Standard". American Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "American Foxhound Breed Standard". American Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "Greyhound History". American Kennel Club. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "End of the road for illegal hare coursing". BBC Inside Out. 24 January 2005. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ "Hunt Etiquette" (PDF). Waitemata Hunt. October 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Information and Guidelines for Foxhunters in the Field". Independence Foxhounds. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ "Hunting Hounds and Polo Ponies". JoCo History. 1998. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (7 November 2006). "The banned rode on". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ McLeod, I. (2005). "Birds of prey and the Hunting Act 2004". Justice of the Peace. 169: 774–775.

- ^

Robards, Hugh J. (16 April 2011). Foxhunting: How to Watch and Listen. Foxhunters' Library. Lanham, Maryland: Derrydale Press. pp. 21, 137. ISBN 978-1-58667-121-1. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

On approaching the road, the hounds check (lose the scent), then cast (deploy) themselves over. [...] check [-] when hounds lose the line of the fox

- ^ "Steeplechase". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2008. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- ^ "A History of Point to Point". Irish Point to Point. 2003. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b c "Customs of Hunting". Icons – A portrait of Britain. 2006. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- ^ Misstear, R. (26 March 2013). "Incidents of illegal fox cubbing reported to RSPCA officers". Walesonline. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Thomas, L.H.; Allen, W.R. (2000). "A veterinary opinion on hunting with hounds, Submission to the Burns Inquiry". Veterinary Association for Wildlife Management. Retrieved 20 November 2007.

- ^ Fanshawe (2003). "Future of hound breeds under threat from hunting bill". Masters of Fox Hounds Association. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "What Is Cubbing?". The Canary. 19 August 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^

Misstear, Rachael (26 March 2013). "Incidents". WalesOnline. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

RSPCA inspector Keith Hogben said [...] 'The practice is entirely illegal under the Hunting Act 2004.'

- ^ "What is cubbing?". Keep The Ban. 2022. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Rusk, Eliza (2016). This country life:old houses. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-5305-9754-3.

- ^ Jahiel, Jessica (2000). The complete idiot's guide to Horseback Riding. p. 178.

- ^ Who's Who. 1983. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7136-2280-5.

- ^ a b c d e "Organization in the field". Miami Valley Hunt. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ "Code of conduct". Irish Masters of Foxhounds Association. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "About Parliament – Whips". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ "Hunt terriermen". Campaign for the Abolition of Terrier Work. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "Horse Country Life – Questions about Foxhunting Attire, Books, Etiquette, Antiques". horsecountrylife.com.

- ^ Reeds, Jim (7 December 2003). "The Legend of Tailor Pink". horse-country.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Hunting Fashion". Icons – A portrait of Britain. July 2006. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ a b c "Dress Code". Beech Grove Hunt. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ "Dress Code". RMA Sandhurst Draghunt. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs (1999). "Background to the Inquiry". Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ "Final Report of the Committee of Inquiry into Hunting with Dogs in England and Wales, para 4.12". Defra. 9 June 2000. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2008.

- ^ Burns, T. (12 March 2001). "Lords Hansard". House of Lords. Retrieved 29 February 2008.

- ^ "Hunt Crimewatch". League Against Cruel Sports. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ "RSPCA wins right to block hunt lobby". The Telegraph. London. 19 June 2001. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ^ "HSA hunt tactics book". Hunt Saboteurs Association. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ "Hunter Harassment Laws". American Hunt Saboteurs Association. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Ryder, R. (2000). "Submission to the Burns Inquiry". Defra. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Kruuk, H (1972). "Surplus killing by carnivores". Journal of Zoology, London. 166 (2): 435–50. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1972.tb04087.x.

- ^ Baldwin, Marc (29 April 2007). "Red Fox Vulpes vulpes:Food & Feeding". Wildlife Online. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- ^ "Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) General description". National Fox Welfare Society. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2008.

- ^ "New research explodes myth that hunting with gun-packs controlled foxes in Wales". International Fund for Animal Welfare. 2006. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Deadline 2000 (2000). "Submission to Burns Inquiry". The National Archives. Defra. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Baker, P.J.; Harris, S.; Webbon, C.C. (2002). "Ecology: Effect of British hunting ban on fox numbers". Nature. 419 (6902): 34. Bibcode:2002Natur.419...34B. doi:10.1038/419034a. PMID 12214224. S2CID 4392265.

- ^ Leader-Williams, N.; Oldfield, T.E.; Smith, R.J.; Walpole, M.J. (2002). "Science, conservation and fox-hunting". Nature. 419 (6910): 878. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..878L. doi:10.1038/419878a. PMID 12410283.

- ^ a b League Against Cruel Sports (2000). "Submission to Burns Inquiry". Defra. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "European Red Fox Fact Sheet". Environment Department, Australian Government. 2004. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ Simon Hart (26 December 2007). "Hounding out a law that's failed in every way". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ a b "Is fox hunting cruel?". BBC News. 16 September 1999. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "The universal declaration of animal rights". Uncaged. 2006. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "General FAQs". People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "MFHA Code of Hunting Practices". Masters of Foxhounds Association of North America. 2000. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Baker, P.; Harris, S.; White, P. "After the hunt, the future of foxes in Britain" (PDF). International Fund for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- ^ Four Burrows Hunt (2000). "Submission to Burns Inquiry". Defra. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Linzey, A. (2006). "Fox Hunting" (PDF). Christian Socialist Movement. Retrieved 11 February 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "R. (oao The Countryside Alliance; oao Derwin and others) v. Her Majesty's Attorney General and Secretary of State of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs". EWCA. 23 June 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Fanshawe, B. (17 May 2000). "Details of number of hounds involved in hunting, Campaign for Hunting submission to Burns Inquiry". Defra. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "The Hare Hunting Associations, submission to Burns Inquiry". Defra. 2000. Archived from the original on 24 August 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- ^ Harris, S. (23 June 2016). "Investigation launched after footage shows 'Fox Cubs Being Put into Hounds' Kennels'". Huffington Post UK. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "Further arrests in South Herefordshire Hunt animal cruelty probe". BBC News. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ a b Scruton, Roger (2000). "Fox Hunting: The Modern Case. Written submission to the Burns Inquiry". Defra. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ^ Medema, S.G.; Samuels, W.J. (2003). The history of economic thought. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20551-1. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ^ "House of Lords judgement on Hunting Act ECHR challenge". House of Lords. 28 November 2007. Archived from the original on 7 December 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ^ "HECtHR judgment in case Friend and Countryside Alliance and Others v. UK". ECtHR. 24 November 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ "Legal advice for activists". Free Beagles. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Stokes, Elizabeth (1996). "Hunting and Hunt Saboteurs: A Censure Study". University of East London. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "Legal advice on Public Order and trespass". Hunt Saboteurs Association. Archived from the original on 24 November 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "Trespass and Nuisance on Land: Legal Guidance". Crown Prosecution Service. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ^ Countryside Alliance and the Council of Hunting Associations (2006). "Hunting without Harassment" (PDF). Countryside Alliance. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "Banwen Miners Hunt History". The Banwen Miners Hunt. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "Oscar Wilde". Bibliomania. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ^ "Banned Blood Sports". Icons- a portrait of England. 2006. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ Jackson, Steve (2006). "Badger Baiting". Badger Pages. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "John Leech Hunting archive". Andrew Cates. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "Class War Merchandise". London Class War. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ "The Rich at Play". Red Star Research/Revolutions per minute. 2002. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ Clover, Charles (27 July 1999). "New poll shows public not prepared to outlaw hunting". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Orendi, Dagmar (2004). The Debate About Fox Hunting: A Social and Political Analysis (PDF) (Master's). Humboldt Universität zu Berlin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

Further reading

[edit]- Davies, Ross E. (editor). Regulation and Imagination: Legal and Literary Perspectives on Fox-hunting (Green Bag Press 2021).

- Trench, Charles Chenevix. "Nineteenth-Century Hunting". History Today (Aug 1973), Vol. 23 Issue 8, pp 572–580 online.

External links

[edit]- General

- News media

- Hunting and pro-hunting organisations

- Masters of Foxhounds Association (UK)

- Masters of Foxhounds Association of America (USA and Canada)

- Countryside Alliance – Campaign for Hunting (UK)

- The Parliamentary Middle Way Group (UK)

- Veterinary Association for Wildlife Management Archived 12 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Anti-hunting organisations

- Hunt Saboteurs Association (UK)

- League Against Cruel Sports – Hunting with Dogs (UK)

- RSPCA – Ban Hunting (UK)

- Government reports

- Hunting with Dogs (UK).

Fox hunting

View on GrokipediaFox hunting is a traditional field sport originating in England during the 16th century, involving the tracking and pursuit of a wild fox by a pack of scent hounds led by a huntsman, with human participants following on horseback or on foot.[1] The hounds detect the fox's scent and give chase across rural terrain, often resulting in an extended pursuit that may end with the fox being overtaken and killed by the pack.[1] Emerging from earlier pest control practices and a shift from deer hunting due to declining populations, the sport gained its modern form in the 18th century through innovations like Hugo Meynell's breeding of swifter hounds at the Quorn Hunt, fostering organized packs and formalized events that emphasized speed and endurance.[1] By the 19th century, expanded rail networks enabled broader participation, embedding fox hunting as a cornerstone of rural equestrian culture linked to land management and social traditions among the landed classes.[1] Long-standing debates over its ethics, particularly the suffering inflicted on the quarry and hounds, culminated in prohibitions: Scotland's Protection of Wild Mammals Act in 2002 and the UK's Hunting Act 2004, which banned hunting wild mammals with dogs in England and Wales effective February 2005, though exemptions exist for limited pest control scenarios.[2][1] Proponents historically justified it for regulating fox numbers as predators of livestock and game, while critics highlighted cruelty absent empirical proof of superior efficacy over alternatives like shooting.[1] Today, traditional hunting persists legally in Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and parts of the United States—where it often prioritizes the chase over dispatch—alongside drag or trail hunting in banned regions as substitutes using artificial scents.[1]

Historical Development

Origins in Europe

The earliest documented pursuit of foxes with hounds in Europe dates to 1534 in Norfolk, England, where a farmer deployed farm dogs to chase a fox that had been raiding poultry, marking an initial effort at vermin control rather than organized sport.[3][4] Prior to the 16th century, European hunting traditions emphasized larger quarry like deer, boar, and hare using packs of hounds, as codified in medieval forest laws that restricted such activities to nobility and gentry while classifying foxes as pests to be eliminated opportunistically via shooting, trapping, or digging out with terriers.[1][5] Foxes' elusive nature and increasing prevalence amid landscape changes—such as deforestation reducing deer habitats—prompted the adaptation of scent hounds for their pursuit, though packs remained irregular and secondary to stag hunting until fox numbers warranted dedicated efforts.[6] By the mid-17th century, formalized fox hunting packs emerged in England, with the Bilsdale Hunt in Yorkshire founded in 1668 by George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, as one of the earliest continuous operations, reflecting a shift toward systematic vermin management across rural estates.[6] This development coincided with improvements in hound breeding, drawing on Norman and Celtic strains introduced centuries earlier for tracking, which enhanced endurance and scenting ability suited to foxes' terrain-covering runs.[7] In broader Europe, analogous practices appeared sporadically; for instance, German hunts incorporated foxes alongside hares until prohibitions in 1934, but lacked the centralized packs of Britain, often merging with broader coursing traditions under aristocratic oversight.[7] Ireland saw early adoption by the 18th century, influenced by English settlers, though continental variants like French chasse au renard prioritized deer until the 19th century.[1] These origins underscore fox hunting's pragmatic roots in agricultural necessity, evolving from ad hoc responses to predation on livestock—foxes annually killing thousands of poultry and lambs in 16th-century records—into a structured pursuit enabled by England's open fields and improving equine capabilities, distinct from the ritualized game hunts of medieval Europe.[1][6]Expansion to the Americas and Australia

Fox hunting practices were introduced to North America by English settlers during the colonial period, with the earliest documented importation of foxhounds occurring in 1650 when Robert Brooke brought a pack to Maryland alongside his family and horses.[8] This marked the transfer of the European tradition, adapted to local quarry including native red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), which differed from the solely red fox pursuits in Britain. By the mid-18th century, organized hunts emerged, such as those involving George Washington, who maintained a personal pack of hounds and participated in hunts as early as 1768, often on horseback across Virginia plantations. The sport gained traction among colonial elites in Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, where terrain and fox populations supported mounted chases, though early efforts focused more on deer and hare before shifting emphasis to foxes.[9] The formal organization of fox hunts expanded post-independence, with the Piedmont Foxhounds in Virginia established by the late 18th century as one of the earliest subscription-based packs in the United States, predating widespread clubs.[10] Canada's Montreal Hunt, founded in 1826, represents the continent's first documented hunt club, while in the U.S., proliferation accelerated after the Civil War, yielding 76 registered packs by 1904 across regions from the Northeast to the Midwest and Southwest.[9] This growth reflected socioeconomic patterns akin to Britain, attracting landowners and gentry, but incorporated American variations like trail hunting on varied landscapes and occasional coyote pursuits in open prairies. By the early 20th century, the Masters of Foxhounds Association formalized standards, overseeing over 145 registered packs today, primarily east of the Mississippi River where fox densities and private land access align with traditional methods.[10] In Australia, fox hunting arrived with British colonial expansion, though initial hound imports in 1810 under Governor Lachlan Macquarie targeted both foxes and stags for sport, predating viable fox populations.[11] European red foxes, absent natively, were deliberately introduced starting in the mid-1850s—specifically around 1855 in Victoria—for recreational hunting to replicate English pastimes among settlers.[12] Releases centered near Melbourne, with feral populations establishing by the early 1870s and spreading rapidly; genetic studies confirm multiple Victorian introductions circa 1870 fueled this colonization, reaching continental coverage within 70 years.[13] Organized hunts, such as those by the Sydney Hunt Club from its 1810s origins, persisted into the 20th century but faced decline due to foxes' invasive status, which shifted perceptions from sport to pest control, limiting mounted traditions to select clubs in New South Wales and Victoria amid regulatory scrutiny.[14] Unlike North America, Australia's arid interior constrained fox densities and hunt viability, confining expansion to temperate southeastern regions.[15]Evolution of Organized Hunts

Organized fox hunting emerged in England during the late 17th century, transitioning from ad hoc pursuits by farmers and landowners to structured packs maintained for systematic quarry control and sport. Early packs, such as those in the Quorn country hunted by Thomas Boothby around the 1740s, represented the first dedicated foxhound subscriptions, where hounds were kenneled collectively and hunts coordinated across defined territories rather than relying on individual landowners' dogs.[7] This shift coincided with agricultural enclosures, which created expansive open fields suitable for prolonged chases, replacing fragmented woodlands previously used for deer hunting.[1] Hugo Meynell, master of the Quorn Hunt from 1753 to 1800, pioneered the modern form by selectively breeding foxhounds for enhanced speed, endurance, and scenting prowess, adapting them to cross-country pursuits over varied terrain.[16] [17] His innovations included prioritizing hounds' stamina for extended runs—often exceeding 20 miles—and integrating faster horse breeds to keep pace, transforming hunts from short, opportunistic kills into strategic, all-day events emphasizing the chase.[1] Meynell's methods, detailed in contemporary hunting diaries, emphasized scientific kennel management, including controlled breeding lines from bloodhounds and staghounds, which standardized pack performance and influenced subsequent hunts nationwide.[16] By the early 19th century, organized hunts proliferated, with over 100 registered packs by 1830, supported by subscription models where subscribers funded masters, huntsmen, and kennels.[18] Formalization included designated hunt countries, annual meets, and codified etiquette, as seen in the establishment of the Masters of Foxhounds Association precursors. This era saw hunts evolve into social institutions among the gentry, with terriers introduced for earth-stopping and whips for hound control, enhancing efficiency in locating and pursuing foxes across expanding rural landscapes altered by the Industrial Revolution.[19] Data from hunt records indicate average pack sizes grew to 40-60 hounds, enabling consistent coverage of 200-300 square miles per season.[1]Core Practices and Elements

Quarry Species

The primary quarry species in fox hunting is the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), a small omnivorous canid weighing 4 to 7 kilograms (8 to 15 pounds) in adults, characterized by its reddish fur, white underbelly, and bushy tail with a black tip.[20] Native to Eurasia and North America, the red fox is prized for its cunning evasion tactics, including using dense cover, doubling back on trails, and denning in underground earths, which provide hounds with a challenging scent trail typically lasting 20 to 60 minutes per hunt.[21] Its adaptability to varied terrains—from open fields to woodlands—has made it the traditional target since fox hunting's formalization in the 18th century, when packs were selectively bred to pursue its distinctive odor over long distances.[22] In regions outside Europe, such as North America, fox hunts may also pursue the gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), a smaller species (3 to 5 kilograms) with grayish fur and arboreal climbing ability, or the coyote (Canis latrans), a larger canid (8 to 20 kilograms) known for straight-line running and pack behavior, particularly in areas where red fox populations are sparse.[8] These alternatives reflect local ecology; for instance, coyotes often replace foxes in western U.S. hunts due to their prevalence as adaptable predators in open prairies.[20] Occasionally, bobcats (Lynx rufus) are chased in southern states, though hunts emphasize non-lethal pursuit to preserve quarry populations for sustained sport.[23] In the United Kingdom, prior to the 2004 ban on live quarry hunting, the red fox remained the exclusive target, with no native gray fox and coyotes absent from the ecosystem.[24]Hounds, Horses, and Supporting Animals

The primary hounds employed in fox hunting are English Foxhounds, a breed selectively developed in England during the late 16th century specifically for pursuing foxes in packs through varied terrain.[19] These hounds exhibit substantial builds with long, straight legs suited for galloping, broad chests for endurance, and an acute sense of smell derived from crosses with stag-hunting hounds known for scenting and stamina.[25][26] Packs typically consist of 20 to 40 hounds, counted in couples (pairs), enabling coordinated tracking via vocalization and collective scenting to follow the fox's trail over distances that can span several miles.[27][28] Horses used in fox hunting, known as field hunters, prioritize functional traits over specific breeds, requiring stamina to sustain several hours of pursuit across rough countryside, a calm temperament to handle the excitement of hounds and crowds, bravery for navigating natural obstacles, and reliable jumping ability to clear hedges, walls, and ditches without refusal.[22][29] Common types include Thoroughbreds, draft-Thoroughbred crosses, and other athletic equines like Warmbloods or ponies, selected for soundness, fitness, and sure-footedness rather than pedigree exclusivity.[30] Riders accustom these mounts to hunt conditions through progressive training, ensuring they remain responsive amid unpredictable chases.[31] Supporting animals include working terriers deployed by terriermen to assist in locating and flushing foxes from underground dens or earths, preventing evasion and aiding the hounds' pursuit.[32] Breeds such as Jack Russell Terriers, Patterdale Terriers, Border Terriers, Lakeland Terriers, and Fell Terriers are favored for their gameness, agility in confined spaces, and vermin-hunting instincts, often entering burrows to bay or extract the quarry.[33][34] These terriers, typically small and tenacious, complement the pack by addressing scenarios where foxes seek refuge below ground, though their use varies by hunt protocol and regional regulations.[35]Seasonal Procedures and Cubbing