Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Activism

View on Wikipedia

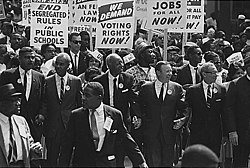

Activism consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived common good. Forms of activism range from mandate building in a community (including writing letters to newspapers), petitioning elected officials, running or contributing to a political campaign, preferential patronage (or boycott) of businesses, and demonstrative forms of activism like rallies, street marches, strikes, sit-ins, or hunger strikes.

Activism may be performed on a day-to-day basis in a wide variety of ways, including through the creation of art (artivism), computer hacking (hacktivism), or simply in how one chooses to spend their money (economic activism). For example, the refusal to buy clothes or other merchandise from a company as a protest against the exploitation of workers by that company could be considered an expression of activism. However, the term commonly refers to a form of collective action, in which numerous individuals coordinate an act of protest together.[1] Collective action that is purposeful, organized, and sustained over a period of time becomes known as a social movement.[2]

Historically, activists have used literature, including pamphlets, tracts, and books to disseminate or propagate their messages and attempt to persuade their readers of the justice of their cause.[3] Research has now begun to explore how contemporary activist groups use social media to facilitate civic engagement and collective action combining politics with technology.[4][5] Left-wing and right-wing online activists often use different tactics. Hashtag activism and offline protest are more common on the left. Working strategically with partisan media, migrating to alternative platforms, and manipulation of mainstream media are more common on the right (in the United States).[6] In addition, the perception of increased left-wing activism in science and academia may decrease conservative trust in science and motivate some forms of conservative activism, including on college campuses.[7] Some scholars have also shown how the influence of very wealthy Americans is a form of activism.[8][9]

Separating activism and terrorism can be difficult and has been described as a 'fine line'.[10]

Definitions of activism

[edit]The Online Etymology Dictionary records the English words "activism" and "activist" as in use in the political sense from the year 1920[11] or 1915[12] respectively. The history of the word activism traces back to earlier understandings of collective behavior[13][14][15] and social action.[16] As late as 1969 activism was defined as "the policy or practice of doing things with decision and energy", without regard to a political signification, whereas social action was defined as "organized action taken by a group to improve social conditions", without regard to normative status. Following the surge of "new social movements" in the United States during the 1960s, activism came to be understood as a rational and legitimate democratic form of protest or appeal.[17][18][19]

However, the history of the existence of revolt through organized or unified protest in recorded history dates back to the slave revolts of the 1st century BC(E) in the Roman Empire, where under the leadership of former gladiator Spartacus 6,000 slaves rebelled and were crucified from Capua to Rome in what became known as the Third Servile War.[20]

In English history, the Peasants' Revolt erupted in response to the imposition of a poll tax,[21] and has been paralleled by other rebellions and revolutions in Hungary, Russia, and more recently, for example, Hong Kong. In 1930 under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi thousands of protesting Indians participated in the Salt March,[22] as a protest against the oppressive taxes of their government, resulting in the imprisonment of 60,000 people and eventually independence of their nation. In nations throughout Asia, Africa and South America, the prominence of activism organized by social movements and especially under the leadership of civil activists or social revolutionaries has pushed for increasing national self-reliance or, in some parts of the developing world, collectivist communist or socialist organization and affiliation.[23] Activism has had major impacts on Western societies as well, particularly over the past century through social movements such as the Labour movement, the women's rights movement, and the civil rights movement.[24]

Types of activism

[edit]

Activism has often been thought to address either human rights or environmental concerns, but libertarian and religious right activism are also important types.[25] Human rights and environmental issues have historically been treated separately both within international law and as activist movements;[26] prior to the 21st century, most human rights movements did not explicitly treat environmental issues, and likewise, human rights concerns were not typically integrated into early environmental activism.[27] In the 21st century, the intersection between human rights and environmentalism has become increasingly important, leading to criticism of the mainstream environmentalist movement[28] and the development of the environmental justice and climate justice movements.

Human rights

[edit]Human rights activism seeks to protect basic rights such as those laid out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights including such liberties as: right to life, citizenship, and property, freedom of movement; constitutional freedoms of thought, expression, religion, peaceful assembly; and others.[29] The foundations of the global human rights movement involve resistance to colonialism, imperialism, slavery, racism, segregation, patriarchy, and oppression of indigenous peoples.[30]

Environment

[edit]Environmental activism takes quite a few forms:

- the protection of nature or the natural environment driven by a utilitarian conservation ethic or a nature oriented preservationist ethic

- the protection of the human environment (by pollution prevention or the protection of cultural heritage or quality of life)

- the conservation of depletable natural resources

- the protection of the function of critical earth system elements or processes such as the climate.

Animal rights

[edit]Shareholder activists

[edit]Libertarian and conservative

[edit]Activism is increasingly important on the political right in the United States and other countries, and some scholars have found: "the main split in conservatism has not been the long-standing one between economic and social conservatives detected in previous surveys (i.e., approximately the Libertarian right and the Christian right). Instead, it is between an emergent group (Activists) that fuses both ideologies and a less ideological category of 'somewhat conservative' Establishment Republicans."[25] One example of this activism is the Tea Party movement.[25]

Pew Research identified a "group of 'Staunch Conservatives' (11 percent of the electorate) who are strongly religious, across-the-board socially and economically conservative, and more politically active than other groups on the Right. They support the Tea Party at 72 percent, far higher than the next most favorable group."[25] One analysis found a group estimated to be 4% of the electorate who identified both as libertarians and staunch religious conservatives "to be the core of this group of high-engagement voters" and labeled this group "Activists."[25]

Methods

[edit]

Activists employ many different methods, or tactics, in pursuit of their goals.[2] The tactics chosen are significant because they can determine how activists are perceived and what they are capable of accomplishing. For example, nonviolent tactics generally tend to garner more public sympathy than violent ones.[31] and are more than twice as effective in achieving stated goals.[32]

Historically, most activism has focused on creating substantive changes in the policy or practice of a government or industry. Some activists try to persuade people to change their behavior directly (see also direct action), rather than to persuade governments to change laws.[33] For example, the cooperative movement seeks to build new institutions which conform to cooperative principles, and generally does not lobby or protest politically. Other activists try to persuade people or government policy to remain the same, in an effort to counter change.

Greta Thunberg a Swedish climate activist is known for founding the Fridays for Future movement.

Charles Tilly developed the concept of a "repertoire of contention", which describes the full range of tactics available to activists at a given time and place.[34] This repertoire consists of all of the tactics which have been proven to be successful by activists in the past, such as boycotts, petitions, marches, and sit-ins, and can be drawn upon by any new activists and social movements. Activists may also innovate new tactics of protest. These may be entirely novel, such as Douglas Schuler's idea of an "activist road trip",[35][36] or may occur in response to police oppression or countermovement resistance.[37] New tactics then spread to others through a social process known as diffusion, and if successful, may become new additions to the activist repertoire.[38]

Activism is not an activity always performed by those who profess activism as a profession.[39] The term "activist" may apply broadly to anyone who engages in activism, or narrowly limited to those who choose political or social activism as a vocation or characteristic practice.

Helena Alviar Garcia has combined activism with her work as a legal scholar, resulting in academia being seen as activism.[40]

Political activism

[edit]Judges may employ judicial activism to promote their own conception of the social good. The definition of judicial activism and whether a specific decisions is activist are controversial political issues.[41] The legal systems of different nations vary in the extent that judicial activism may be permitted.

Activists can also be public watchdogs and whistle blowers by holding government agencies accountable to oversight and transparency.[42]

Political activism may also include political campaigning, lobbying, voting, or petitioning. Often political activists also publish their ideas themselves via newsletters, periodicals, presses, or digital media.[3]

Political activism does not depend on a specific ideology or national history, as can be seen, for example, in the importance of conservative British women in the 1920s on issues of tariffs.[43]

Political activism, although often identified with young adults, occurs across peoples entire life-courses.[44]

Political activism on college campuses has been influential in left-wing politics since the 1960s, and recently there has been "a rise in conservative activism on US college campuses" and "it is common for conservative political organizations to donate money to relatively small conservative students groups".[7]

While people's motivations for political activism may vary, one model examined activism in the British Conservative party and found three primary motivations: (1) "incentives, such as ambitions for elective office", (2) "a desire for the party to achieve policy goals" and (3) "expressive concerns, as measured by the strength of the respondent's partisanship".[45]

In addition, very wealthy Americans can exercise political activism through massive financial support of political causes, and one study of the 400 richest Americans found "substantial evidence of liberal or right-wing activism that went beyond making contributions to political candidates."[8] This study also found, in general, "old money is, if anything, more uniformly conservative than new money."[8] Another study examined how "activism of the wealthy" has often increased inequality but is now sometimes used to decrease economic inequality.[9]

Internet activism

[edit]The power of Internet activism came into a global lens with the Arab Spring protests starting in late 2010. People living in the Middle East and North African countries that were experiencing revolutions used social networking to communicate information about protests, including videos recorded on smart phones, which put the issues in front of an international audience.[46] This was one of the first occasions in which social networking technology was used by citizen-activists to circumvent state-controlled media and communicate directly with the rest of the world. These types of practices of Internet activism were later picked up and used by other activists in subsequent mass mobilizations, such as the 15-M Movement in Spain in 2011, Occupy Gezi in Turkey in 2013, and more.[47]

Online "left- and right-wing activists use digital and legacy media differently to achieve political goals".[6] Left-wing online activists are usually more involved in traditional "hashtag activism" and offline protest, while right-wing activists may "manipulate legacy media, migrate to alternative platforms, and work strategically with partisan media to spread their messages".[6] Research suggests right-wing online activists are more likely to use "strategic disinformation and conspiracy theories".[6]

Internet activism may also refer to activism which focuses on protecting or changing the Internet itself, also known as digital rights. The Digital Rights movement[48] consists of activists and organizations, such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who work to protect the rights of people in relation to new technologies, particularly concerning the Internet and other information and communications technologies.

Many contemporary activists now utilize new tactics through the Internet and other information and communication technologies (ICTs), also known as Internet activism or cyber-activism. Some scholars argue that many of these new tactics are digitally analogous to the traditional offline tools of contention.[49] Other digital tactics may be entire new and unique, such as certain types of hacktivism.[34][50] Together they form a new "digital repertoire of contention" alongside the existing offline one.[51] The rising use of digital tools and platforms by activists[52] has also increasingly led to the creation of decentralized networks of activists that are self-organized[53][54][55] and leaderless,[47][56] or what is known as franchise activism.

Economic activism

[edit]Economic activism involves using the economic power of government, consumers, and businesses for social and economic policy change.[57] Both conservative and liberal groups use economic activism as a form of pressure to influence companies and organizations to oppose or support particular political, religious, or social values and behaviors.[58] This may be done through ethical consumerism to reinforce "good" behavior and support companies one would like to succeed, or through boycott or divestment to penalize "bad" behavior and pressure companies to change or go out of business.

Brand activism[59] is the type of activism in which business plays a leading role in the processes of social change. Applying brand activism, businesses show concern for the communities they serve, and their economic, social, and environmental problems, which allows businesses to build sustainable and long-term relationships with the customers and prospects. Kotler and Sarkar defined the phenomenon as an attempt by firms to solve the global problems its future customers and employees care about.[60]

Consumer activism consists of activism carried out on behalf of consumers for consumer protection or by consumers themselves. For instance, activists in the free produce movement of the late 1700s protested against slavery by boycotting goods produced with slave labor. Today, vegetarianism, veganism, and freeganism are all forms of consumer activism which boycott certain types of products. Other examples of consumer activism include simple living, a minimalist lifestyle intended to reduce materialism and conspicuous consumption, and tax resistance, a form of direct action and civil disobedience in opposition to the government that is imposing the tax, to government policy, or as opposition to taxation in itself.

Shareholder activism involves shareholders using an equity stake in a corporation to put pressure on its management.[61] The goals of activist shareholders range from financial (increase of shareholder value through changes in corporate policy, financing structure, cost cutting, etc.) to non-financial (disinvestment from particular countries, adoption of environmentally friendly policies, etc.).[62]

Art activism

[edit]Design activism locates design at the center of promoting social change, raising awareness on social/political issues, or questioning problems associated with mass production and consumerism. Design Activism is not limited to one type of design.[63][64]

Art activism or artivism utilizes the medium of visual art as a method of social or political commentary. Art activism can activate utopian thinking, which is imagining about an ideal society that is different from the current society, which is found to be effective for increasing collective action intentions.

Fashion activism was coined by Celine Semaan.[65] Fashion activism is a type of activism that ignites awareness by giving consumers tools to support change, specifically in the fashion industry.[66][67] It has been used as an umbrella term for many social and political movements that have taken place in the industry.[68] Fashion Activism uses a participatory approach to a political activity.[69]

Craft activism or craftivism is a type of visual activism that allows people to bring awareness to political or social discourse.[70] It is a creative approach to activism as it allows people to send short and clear messages to society.[71] People who contribute to craftivism are called "craftivists".[72]

Activism in literature may publish written works that express intended or advocated reforms. Alternatively, literary activism may also seek to reform perceived corruption or entrenched systems of power within the publishing industry.

Science activism

[edit]Science activism may include efforts to better communicate the benefits of science or ensure continued funding for scientific research.[73][74] It may also include efforts to increase perceived legitimacy of particular scientific fields or respond to the politicization of particular fields.[75] The March for Science held around the world in 2017 and 2018 were notable examples of science activism. Approaches to science activism vary from protests to more psychological, marketing-oriented approaches that takes into account such factors as individual sense of self, aversion to solutions to problems, and social perceptions.[76]

Other methods

[edit]- Community building

- Manipulation

- Media activism

- Peace activism

- Propaganda

- Protest

- Strike action

Activism industry

[edit]Some groups and organizations participate in activism to such an extent that it can be considered as an industry. In these cases, activism is often done full-time, as part of an organization's core business. Many organizations in the activism industry are either non-profit organizations or non-governmental organizations with specific aims and objectives in mind. Most activist organizations do not manufacture goods,[citation needed] but rather mobilize personnel to recruit funds and gain media coverage.

The term activism industry has often been used to refer to outsourced fundraising operations. However, activist organizations engage in other activities as well.[77] Lobbying, or the influencing of decisions made by government, is another activist tactic. Many groups, including law firms, have designated staff assigned specifically for lobbying purposes. In the United States, lobbying is regulated by the federal government.[78]

Many government systems encourage public support of non-profit organizations by granting various forms of tax relief for donations to charitable organizations. Governments may attempt to deny these benefits to activists by restricting the political activity of tax-exempt organizations.

See also

[edit]- Arab Spring

- Advocacy evaluation

- Advocacy group

- Advocacy

- Animal rights

- Asian American activism

- Civil disobedience

- Community leader

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Cultural activism

- Demonstration (protest)

- Dissident

- Human rights activists

- List of activists

- List of peace activists

- Media manipulation

- Restorationism

- Slacktivism

- Social engineering (political science)

- Spiritual activism

- Student activism

- Water protectors

- Youth activism

References

[edit]- ^ Tarrow, Sidney (1998). Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-07680-7. OCLC 727948411.

- ^ a b Goodwin, Jeff; Jasper, James (2009). The Social Movements Reader: Cases and Concepts (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8764-0.

- ^ a b Ostertag, Bob (2006). People's movements, people's press: the journalism of social justice movements. Boston, Mass: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-6164-0.

- ^ Obar, Jonathan; et al. (2012). "Advocacy 2.0: An Analysis of How Advocacy Groups in the United States Perceive and Use Social Media as Tools for Facilitating Civic Engagement and Collective Action". Journal of Information Policy. 2: 1–25. doi:10.5325/jinfopoli.2.2012.1. S2CID 246628982. SSRN 1956352.

- ^ Obar, Jonathan (2014). "Canadian Advocacy 2.0: A Study of Social Media Use by Social Movement Groups and Activists in Canada". Canadian Journal of Communication. 39. doi:10.22230/cjc.2014v39n2a2678. SSRN 2254742.

- ^ a b c d Freelon, Deen; Marwick, Alice; Kreiss, Daniel (4 September 2020). "False equivalencies: Online activism from left to right". Science. 369 (6508): 1197–1201. Bibcode:2020Sci...369.1197F. doi:10.1126/science.abb2428. PMID 32883863. S2CID 221471947. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b Ince, Jelani; Finlay, Brandon M.; Rojas, Fabio (2018). "College campus activism: Distinguishing between liberal reformers and conservative crusaders". Sociology Compass. 12 (9) e12603. doi:10.1111/soc4.12603. ISSN 1751-9020. S2CID 150160691. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Burris, Val (1 August 2000). "The Myth of Old Money Liberalism: The Politics of the Forbes 400 Richest Americans". Social Problems. 47 (3): 360–378. doi:10.2307/3097235. ISSN 0037-7791. JSTOR 3097235.

- ^ a b Scully, Maureen; Rothenberg, Sandra; Beaton, Erynn E.; Tang, Zhi (20 March 2017). "Mobilizing the Wealthy: Doing "Privilege Work" and Challenging the Roots of Inequality". Business & Society. 57 (6): 1075–1113. doi:10.1177/0007650317698941. ISSN 0007-6503. S2CID 157605628.

- ^ Bohmer, Carol (2010). Rejecting refugees: political asylum in the 21st century. Routledge. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-415-77375-1. OCLC 743396687.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "activism". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "activist". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Park, Robert; Burgess, Ernest (1921). Introduction to the Science of Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Merton, Robert (1945). Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press.

- ^ Hoffer, Eric (1951). The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ Parsons, Talcott (1937). The Structure of Social Action. New York: Free Press.

- ^ Olson, Mancur (1965). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Gamson, William A. (1975). The Strategy of Social Protest. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press. ISBN 978-0-256-01684-0.

- ^ Tilly, Charles (1978). From Mobilization to Revolution. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-07571-7.

- ^ Czech, Kenneth P. (April 1994). "Ancient History: Spartacus and the Slave Rebellion". HistoryNet. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ "Peasants' Revolt". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ Pletcher, Kenneth (14 December 2015). "Salt March". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Goodwin, Jeff (2001). No Other Way Out: States and Revolutionary Movements, 1945–1991. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Meyer, David; Tarrow, Sidney (1998). The Social Movement Society: Contentious Politics for a New Century. Rowman & Littlefield.

- ^ a b c d e Keckler, Charles; Rozell, Mark J. (3 April 2015). "The Libertarian Right and the Religious Right". Perspectives on Political Science. 44 (2): 92–99. doi:10.1080/10457097.2015.1011476. ISSN 1045-7097. S2CID 145428669.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (11 October 2012). "Human Rights and the Environment: Where Next?". European Journal of International Law. 23 (3): 613–642. doi:10.1093/ejil/chs054. Archived from the original on 5 June 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2021 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ "Introduction" (PDF). Human Rights Dialogue. 2 (11): 2. Spring 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Britton-Purdy, Jedediah (7 September 2016). "Environmentalism Was Once a Social-Justice Movement". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations. 1948. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009.

- ^ Clapham, Human Rights (2007), p. 19. "In fact, the modern civil rights movement and the complex normative international framework have grown out of a number of transnational and widespread movements. Human rights were invoked and claimed in the contexts of anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, anti-slavery, anti-apartheid, anti-racism, and feminist and indigenous struggles everywhere."

- ^ Zunes, Stephen; Asher, Sarah Beth; Kurtz, Lester (1999). Nonviolent Social Movements: A Geographical Perspective. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-57718-075-3. OCLC 40753886.

- ^ Chenoweth, Erica; Stephan, Maria J. (2013). Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15683-7. OCLC 810145714.

- ^ "Direct action". Activist Handbook. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ a b Tilly, Charles; Tarrow, Sidney (2015). Contentious Politics (Second revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-025505-3. OCLC 909883395.

- ^ Schuler, Douglas (2008). Liberating Voices: A Pattern Language for Communication Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-69366-0.

- ^ "Activist Road Trip". Public Sphere Project. 2008. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ McAdam, Doug (1983). "Tactical Innovation and the Pace of Insurgency". American Sociological Review. 48 (6): 735–754. doi:10.2307/2095322. JSTOR 2095322.

- ^ Ayres, Jeffrey M. (1999). "From the Streets to the Internet: The Cyber-Diffusion of Contention". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 566 (1): 132–143. doi:10.1177/000271629956600111. ISSN 0002-7162. S2CID 154834235.

- ^ "Introduction to Activism". Permanent Culture Now. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Beasley Doyle, Heather (15 December 2016). "For Latin American legal scholar returning to teach at HLS, 'academia is activism'". Harvard Law Today. Retrieved 14 January 2025.

- ^ Kmiec, Keenan D. (October 2004). "The Origin and Current Meanings of Judicial Activism". California Law Review. 92 (5): 1441–1478. doi:10.2307/3481421. JSTOR 3481421. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ "Politically Active? 4 Tips for Incorporating Self-Care, US News". US News. 27 February 2017. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ Thackeray, David (October 2010). "Home and Politics: Women and Conservative Activism in Early Twentieth-Century Britain". Journal of British Studies. 49 (4): 826–848. doi:10.1086/654913. ISSN 1545-6986. PMID 20941876. S2CID 27993371. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Nolas, Sevasti-Melissa; Varvantakis, Christos; Aruldoss, Vinnarasan, eds. (18 December 2019). Political Activism across the Life Course. doi:10.4324/9781351201797. ISBN 978-1-351-20179-7. Archived from the original on 29 June 2023.

- ^ Whiteley, Paul F.; Seyd, Patrick; Richardson, Jeremy; Bissell, Paul (January 1994). "Explaining Party Activism: The Case of the British Conservative Party". British Journal of Political Science. 24 (1): 79–94. doi:10.1017/S0007123400006797. ISSN 1469-2112. S2CID 154681634. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ^ Sliwinski, Michael (21 January 2016). "The Evolution of Activism: From the Streets to Social Media". Law Street. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ a b Zeynep, Tufekci (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21512-0. OCLC 961312425.

- ^ Hector, Postigo (2012). The digital rights movement: the role of technology in subverting digital copyright. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-30533-4. OCLC 812346336.

- ^ Meikle, Graham (2002). Future Active: Media Activism and the Internet. Annandale, N.S.W.: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-1-86403-148-5. OCLC 50165391.

- ^ Samuel, Alexandra (2004). Hacktivism and the Future of Political Participation. Harvard University: Doctoral Dissertation.

- ^ Earl, Jennifer; Kimport, Katrina (2011). Digitally Enabled Social Change: Activism in the Internet Age. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-29535-2. OCLC 727948420.

- ^ Rolfe, Brett (2005). "Building an Electronic Repertoire of Contention". Social Movement Studies. 4 (1): 65–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.457.9077. doi:10.1080/14742830500051945. ISSN 1474-2837. S2CID 10619520.

- ^ Fuchs, Christian (2006). "The Self-Organization of Social Movements". Systemic Practice and Action Research. 19 (1): 101–137. doi:10.1007/s11213-005-9006-0. ISSN 1094-429X. S2CID 38385359.

- ^ Clay, Shirky (2008). Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-153-0. OCLC 168716646.

- ^ Castells, Manuel (2015). Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-9575-4. OCLC 896126968.

- ^ Carne, Ross (2013). The Leaderless Revolution: How Ordinary People will Take Power and Change Politics in the 21st Century. New York: Plume. ISBN 978-0-452-29894-1. OCLC 795168105.

- ^ Lin, Tom C. W., Incorporating Social Activism Archived 1 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine (1 December 2018). 98 Boston University Law Review 1535 (2018)

- ^ White, Ben and Romm, Tony, Corporate America Tackles Trump Archived 4 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Politico, (6 February 2017)

- ^ Sarkar, Christian; Kotler, Philip (October 2018). Brand Activism: From Purpose to Action. ISBN 978-0-9905767-9-2.

- ^ "WHAT IS BRAND ACTIVISM? – ActivistBrands.com". Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Lin, Tom C. W. (18 March 2015). "Reasonable Investor(s)". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2579510.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Activist Investor Definition". Carried Interest. Archived from the original on 25 June 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Markussen, T (2013). "The Disruptive Aesthetics of Design Activism: Enacting Design Between Art and Politics". Design Issues. 29 (1): 38. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00195. S2CID 17301556.

- ^ Tom Bieling (Ed.): Design (&) Activism – Perspectives on Design as Activism and Activism as Design. Mimesis, Milano, 2019, ISBN 978-88-6977-241-2.

- ^ "Fashion Activism: Changing the World One Trend at a Time | Peacock Plume". peacockplume.fr. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ^ Hirscher, Anja-Lisa (2013). "Fashion Activism Evaluation and Application of Fashion Activism Strategies to Ease Transition Towards Sustainable Consumption Behaviour". Research Journal of Textile and Apparel. 17: 23–38. doi:10.1108/RJTA-17-01-2013-B003.

- ^ Mazzarella, Francesco; Storey, Helen; Williams, Dilys (1 April 2019). "Counter-narratives Towards Sustainability in Fashion. Scoping an Academic Discourse on Fashion Activism through a Case Study on the Centre for Sustainable Fashion". The Design Journal. 22 (sup1): 821–833. doi:10.1080/14606925.2019.1595402. ISSN 1460-6925.

- ^ Fuad-Lake, Alastair (2009). Design activism: beautiful strangeness for a sustainable world. Sterling, VA: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-644-4.

- ^ Hirscher, Anja-Lisa; Niinimäki, Kirsi (2013). "Fashion Activism through Participatory Design". European Academy of Design.

- ^ Youngson, Bel (5 February 2019). "Craftivism for occupational therapists: finding our political voice" (PDF). British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 82 (6): 383–385. doi:10.1177/0308022619825807. ISSN 0308-0226. S2CID 86850023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Corbett, Sarah; Housely, Sarah (2011). "The Craftivist Collective Guide to Craftivism". Utopian Studies. 22 (2): 344–351. doi:10.5325/utopianstudies.22.2.0344. S2CID 141667893.

- ^ Greer, Betsy, ed. (21 April 2014). Craftivism: the art of craft and activism. Vancouver. ISBN 978-1-55152-535-8. OCLC 1032507461.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Daie, Jaleh (1996). "The Activist Scientist". Science. 272 (5265): 1081. Bibcode:1996Sci...272.1081D. doi:10.1126/science.272.5265.1081.

- ^ Hernandez, Daniela (22 April 2017). "Why Some Scientists Are Embracing Activism". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Scheitle, Christopher P. (2018). "Politics and the Perceived Boundaries of Science: Activism, Sociology, and Scientific Legitimacy". Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World. 4 2378023118769544: 237802311876954. doi:10.1177/2378023118769544.

- ^ Campbell, Troy H. (2019). "Team Science: Building Better Science Activists with Insights from Disney, Marketing, and Psychological Research". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 43, no. 4. Center for Inquiry. pp. 34–39. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Fisher, Dana R. (14 September 2006). "The Activism Industry". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Do Pay-For-Placement Search Engines engage in Trademark "Use"?, IP Law360 – Godfrey and Kahn". 11 July 2011. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011.

Further reading

[edit]- Paul Rogat Loeb, Soul of a Citizen: Living With Conviction in a Cynical Time (St Martin's Press, 2010). ISBN 978-0-312-59537-1.

- Brian Martin with Wendy Varney. Nonviolence Speaks: Communicating against Repression, (Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 2003).

- Randy Shaw, The Activist's Handbook: A Primer for the 1990s and Beyond (University of California Press, 1996). ISBN 0-520-20317-8.

- David Walls, The Activist's Almanac: The Concerned Citizen's Guide to the Leading Advocacy Organizations in America (Simon & Schuster/Fireside, 1993). ISBN 0-671-74634-0.

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2022. "Celebrity Activism on Racial Justice during COVID-19: The Death of George Floyd, the Rise of Naomi Osaka, and the Celebritization of Race in Pandemic Times." International Review of Sociology (Published online: March 16, 2022). doi:10.1080/03906701.2022.2052457

- Deflem, Mathieu. 2019. "The New Ethics of Pop: Celebrity Activism Since Lady Gaga." pp. 113–129 in Pop Cultures: Sconfinamenti Alterdisciplinari, edited by Massimiliano Stramaglia. Lecce-Rovato, Italy: Pensa Multimedia. ISBN 9788867606092

- Victor Gold, Liberwocky (Thomas Nelson, 2004). ISBN 978-0-7852-6057-8.

- Commons Social Change Library

Activism

View on GrokipediaActivism encompasses vigorous, direct efforts to influence or alter social, political, economic, or environmental conditions, often through methods like protests, advocacy, boycotts, and civil disobedience that surpass conventional political engagement.[1][2] These actions typically aim to challenge power structures or norms perceived as unjust, drawing on collective mobilization to amplify demands for reform.[3] Historically, activism has catalyzed landmark changes, including the abolition of slavery, advancement of women's suffrage, establishment of labor protections, and progress in civil rights, by shifting public discourse and compelling institutional responses.[1] Nonviolent strategies, when sustained and broadly resonant, have proven particularly effective in achieving policy concessions, as evidenced by empirical analyses of campaigns like those for voting rights.[4] In contrast, modern digital activism excels at rapid awareness-raising and fundraising but frequently falters in translating virtual support into substantive outcomes, a phenomenon termed slacktivism.[5][6] Despite successes, activism's defining characteristics include inherent risks of escalation to violence or coercion, which can provoke backlash and erode legitimacy.[1] Research highlights associations between certain activist orientations—particularly in environmental domains—and traits like Machiavellianism or narcissism, potentially prioritizing symbolic gestures over pragmatic, evidence-based solutions.[7] Performative elements, driven by social signaling rather than causal impact, further complicate assessments of efficacy, as they may foster division without addressing root mechanisms of change.[8] Overall, activism's impact hinges on strategic alignment with empirical realities and public priorities, rather than unyielding ideology.[9]