Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Melting point

View on Wikipedia

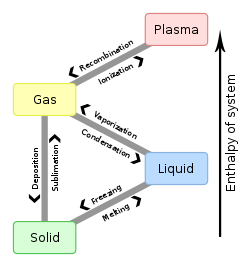

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase exist in equilibrium. The melting point of a substance depends on pressure and is usually specified at a standard pressure such as 1 atmosphere or 100 kPa.

When considered as the temperature of the reverse change from liquid to solid, it is referred to as the freezing point or crystallization point. Because of the ability of substances to supercool, the freezing point can easily appear to be below its actual value. When the "characteristic freezing point" of a substance is determined, in fact, the actual methodology is almost always "the principle of observing the disappearance rather than the formation of ice, that is, the melting point."[1]

Examples

[edit]

For most substances, melting and freezing points are approximately equal. For example, the melting and freezing points of mercury is 234.32 kelvins (−38.83 °C; −37.89 °F).[2] However, certain substances possess differing solid-liquid transition temperatures. For example, agar melts at 85 °C (185 °F; 358 K) and solidifies from 31 °C (88 °F; 304 K); such direction dependence is known as hysteresis. The melting point of ice at 1 atmosphere of pressure is very close[3] to 0 °C (32 °F; 273 K); this is also known as the ice point. In the presence of nucleating substances, the freezing point of water is not always the same as the melting point. In the absence of nucleators water can exist as a supercooled liquid down to −48.3 °C (−54.9 °F; 224.8 K) before freezing.[4]

The metal with the highest melting point is tungsten, at 3,414 °C (6,177 °F; 3,687 K);[5] this property makes tungsten excellent for use as electrical filaments in incandescent lamps. The often-cited carbon does not melt at ambient pressure but sublimes at about 3,700 °C (6,700 °F; 4,000 K); a liquid phase only exists above pressures of 10 MPa (99 atm) and estimated 4,030–4,430 °C (7,290–8,010 °F; 4,300–4,700 K) (see carbon phase diagram). Hafnium carbonitride (HfCN) is a refractory compound with the highest known melting point of any substance to date and the only one confirmed to have a melting point above 4,273 K (4,000 °C; 7,232 °F) at ambient pressure. Quantum mechanical computer simulations predicted that this alloy (HfN0.38C0.51) would have a melting point of about 4,400 K.[6] This prediction was later confirmed by experiment, though a precise measurement of its exact melting point has yet to be confirmed.[7] At the other end of the scale, helium does not freeze at all at normal pressure even at temperatures arbitrarily close to absolute zero; a pressure of more than twenty times normal atmospheric pressure is necessary.

| List of common chemicals | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical[I] | Density (g/cm3) | Melt (K)[8] | Boil (K) | |||||||||

| Water @STP | 1 | 273 | 373 | |||||||||

| Solder (Pb60Sn40) | 461 | |||||||||||

| Cocoa butter | 307.2 | - | ||||||||||

| Paraffin wax | 0.9 | 310 | 643 | |||||||||

| Hydrogen | 0.00008988 | 14.01 | 20.28 | |||||||||

| Helium | 0.0001785 | —[II] | 4.22 | |||||||||

| Beryllium | 1.85 | 1,560 | 2,742 | |||||||||

| Carbon | 2.267 | —[III][9] | 4,000[III][9] | |||||||||

| Nitrogen | 0.0012506 | 63.15 | 77.36 | |||||||||

| Oxygen | 0.001429 | 54.36 | 90.20 | |||||||||

| Sodium | 0.971 | 370.87 | 1,156 | |||||||||

| Magnesium | 1.738 | 923 | 1,363 | |||||||||

| Aluminium | 2.698 | 933.47 | 2,792 | |||||||||

| Sulfur | 2.067 | 388.36 | 717.87 | |||||||||

| Chlorine | 0.003214 | 171.6 | 239.11 | |||||||||

| Potassium | 0.862 | 336.53 | 1,032 | |||||||||

| Titanium | 4.54 | 1,941 | 3,560 | |||||||||

| Iron | 7.874 | 1,811 | 3,134 | |||||||||

| Nickel | 8.912 | 1,728 | 3,186 | |||||||||

| Copper | 8.96 | 1,357.77 | 2,835 | |||||||||

| Zinc | 7.134 | 692.88 | 1,180 | |||||||||

| Gallium | 5.907 | 302.9146 | 2,673 | |||||||||

| Silver | 10.501 | 1,234.93 | 2,435 | |||||||||

| Cadmium | 8.69 | 594.22 | 1,040 | |||||||||

| Indium | 7.31 | 429.75 | 2,345 | |||||||||

| Iodine | 4.93 | 386.85 | 457.4 | |||||||||

| Tantalum | 16.654 | 3,290 | 5,731 | |||||||||

| Tungsten | 19.25 | 3,695 | 5,828 | |||||||||

| Platinum | 21.46 | 2,041.4 | 4,098 | |||||||||

| Gold | 19.282 | 1,337.33 | 3,129 | |||||||||

| Mercury | 13.5336 | 234.43 | 629.88 | |||||||||

| Lead | 11.342 | 600.61 | 2,022 | |||||||||

| Bismuth | 9.807 | 544.7 | 1,837 | |||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||

Melting point measurements

[edit]

Many laboratory techniques exist for the determination of melting points. A Kofler bench is a metal strip with a temperature gradient (range from room temperature to 300 °C). Any substance can be placed on a section of the strip, revealing its thermal behaviour at the temperature at that point. Differential scanning calorimetry gives information on melting point together with its enthalpy of fusion.

A basic melting point apparatus for the analysis of crystalline solids consists of an oil bath with a transparent window (most basic design: a Thiele tube) and a simple magnifier. Several grains of a solid are placed in a thin glass tube and partially immersed in the oil bath. The oil bath is heated (and stirred) and with the aid of the magnifier (and external light source) melting of the individual crystals at a certain temperature can be observed. A metal block might be used instead of an oil bath. Some modern instruments have automatic optical detection.

The measurement can also be made continuously with an operating process. For instance, oil refineries measure the freeze point of diesel fuel "online", meaning that the sample is taken from the process and measured automatically. This allows for more frequent measurements as the sample does not have to be manually collected and taken to a remote laboratory.[citation needed]

Techniques for refractory materials

[edit]For refractory materials (e.g. platinum, tungsten, tantalum, some carbides and nitrides, etc.) the extremely high melting point (typically considered to be above, say, 1,800 °C) may be determined by heating the material in a black body furnace and measuring the black-body temperature with an optical pyrometer. For the highest melting materials, this may require extrapolation by several hundred degrees. The spectral radiance from an incandescent body is known to be a function of its temperature. An optical pyrometer matches the radiance of a body under study to the radiance of a source that has been previously calibrated as a function of temperature. In this way, the measurement of the absolute magnitude of the intensity of radiation is unnecessary. However, known temperatures must be used to determine the calibration of the pyrometer. For temperatures above the calibration range of the source, an extrapolation technique must be employed. This extrapolation is accomplished by using Planck's law of radiation. The constants in this equation are not known with sufficient accuracy, causing errors in the extrapolation to become larger at higher temperatures. However, standard techniques have been developed to perform this extrapolation.[citation needed]

Consider the case of using gold as the source (mp = 1,063 °C). In this technique, the current through the filament of the pyrometer is adjusted until the light intensity of the filament matches that of a black-body at the melting point of gold. This establishes the primary calibration temperature and can be expressed in terms of current through the pyrometer lamp. With the same current setting, the pyrometer is sighted on another black-body at a higher temperature. An absorbing medium of known transmission is inserted between the pyrometer and this black-body. The temperature of the black-body is then adjusted until a match exists between its intensity and that of the pyrometer filament. The true higher temperature of the black-body is then determined from Planck's Law. The absorbing medium is then removed and the current through the filament is adjusted to match the filament intensity to that of the black-body. This establishes a second calibration point for the pyrometer. This step is repeated to carry the calibration to higher temperatures. Now, temperatures and their corresponding pyrometer filament currents are known and a curve of temperature versus current can be drawn. This curve can then be extrapolated to very high temperatures.

In determining melting points of a refractory substance by this method, it is necessary to either have black body conditions or to know the emissivity of the material being measured. The containment of the high melting material in the liquid state may introduce experimental difficulties. Melting temperatures of some refractory metals have thus been measured by observing the radiation from a black body cavity in solid metal specimens that were much longer than they were wide. To form such a cavity, a hole is drilled perpendicular to the long axis at the center of a rod of the material. These rods are then heated by passing a very large current through them, and the radiation emitted from the hole is observed with an optical pyrometer. The point of melting is indicated by the darkening of the hole when the liquid phase appears, destroying the black body conditions. Today, containerless laser heating techniques, combined with fast pyrometers and spectro-pyrometers, are employed to allow for precise control of the time for which the sample is kept at extreme temperatures. Such experiments of sub-second duration address several of the challenges associated with more traditional melting point measurements made at very high temperatures, such as sample vaporization and reaction with the container.

Thermodynamics

[edit]

For a solid to melt, heat is required to raise its temperature to the melting point. However, further heat needs to be supplied for the melting to take place: this is called the heat of fusion, and is an example of latent heat.[10]

From a thermodynamics point of view, at the melting point the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the material is zero, but the enthalpy (H) and the entropy (S) of the material are increasing (ΔH, ΔS > 0). Melting phenomenon happens when the Gibbs free energy of the liquid becomes lower than the solid for that material. At various pressures this happens at a specific temperature. It can also be shown that:

Here T, ΔS and ΔH are respectively the temperature at the melting point, change of entropy of melting and the change of enthalpy of melting.

The melting point is sensitive to extremely large changes in pressure, but generally this sensitivity is orders of magnitude less than that for the boiling point, because the solid-liquid transition represents only a small change in volume.[11][12] If, as observed in most cases, a substance is more dense in the solid than in the liquid state, the melting point will increase with increases in pressure. Otherwise the reverse behavior occurs. Notably, this is the case of water, as illustrated graphically to the right, but also of Si, Ge, Ga, Bi. With extremely large changes in pressure, substantial changes to the melting point are observed. For example, the melting point of silicon at ambient pressure (0.1 MPa) is 1415 °C, but at pressures in excess of 10 GPa it decreases to 1000 °C.[13]

Melting points are often used to characterize organic and inorganic compounds and to ascertain their purity. The melting point of a pure substance is always higher and has a smaller range than the melting point of an impure substance or, more generally, of mixtures. The higher the quantity of other components, the lower the melting point and the broader will be the melting point range, often referred to as the "pasty range". The temperature at which melting begins for a mixture is known as the solidus while the temperature where melting is complete is called the liquidus. Eutectics are special types of mixtures that behave like single phases. They melt sharply at a constant temperature to form a liquid of the same composition. Alternatively, on cooling a liquid with the eutectic composition will solidify as uniformly dispersed, small (fine-grained) mixed crystals with the same composition.

In contrast to crystalline solids, glasses do not possess a melting point; on heating they undergo a smooth glass transition into a viscous liquid. Upon further heating, they gradually soften, which can be characterized by certain softening points.

Freezing-point depression

[edit]The freezing point of a solvent is depressed when another compound is added, meaning that a solution has a lower freezing point than a pure solvent. This phenomenon is used in technical applications to avoid freezing, for instance by adding salt or ethylene glycol to water.[citation needed]

Carnelley's rule

[edit]In organic chemistry, Carnelley's rule, established in 1882 by Thomas Carnelley, states that high molecular symmetry is associated with high melting point.[14] Carnelley based his rule on examination of 15,000 chemical compounds. For example, for three structural isomers with molecular formula C5H12 the melting point increases in the series isopentane −160 °C (113 K) n-pentane −129.8 °C (143 K) and neopentane −16.4 °C (256.8 K).[15] Likewise in xylenes and also dichlorobenzenes the melting point increases in the order meta, ortho and then para. Pyridine has a lower symmetry than benzene hence its lower melting point but the melting point again increases with diazine and triazines. Many cage-like compounds like adamantane and cubane with high symmetry have relatively high melting points.

A high melting point results from a high heat of fusion, a low entropy of fusion, or a combination of both. In highly symmetrical molecules the crystal phase is densely packed with many efficient intermolecular interactions resulting in a higher enthalpy change on melting.

Predicting the melting point of substances (Lindemann's criterion)

[edit]An attempt to predict the bulk melting point of crystalline materials was first made in 1910 by Frederick Lindemann.[17] The idea behind the theory was the observation that the average amplitude of thermal vibrations increases with increasing temperature. Melting initiates when the amplitude of vibration becomes large enough for adjacent atoms to partly occupy the same space. The Lindemann criterion states that melting is expected when the vibration root mean square amplitude exceeds a threshold value.

Assuming that all atoms in a crystal vibrate with the same frequency ν, the average thermal energy can be estimated using the equipartition theorem as[18]

where m is the atomic mass, ν is the frequency, u is the average vibration amplitude, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature. If the threshold value of u2 is c2a2 where c is the Lindemann constant and a is the atomic spacing, then the melting point is estimated as

Several other expressions for the estimated melting temperature can be obtained depending on the estimate of the average thermal energy. Another commonly used expression for the Lindemann criterion is[19]

From the expression for the Debye frequency for ν,

where θD is the Debye temperature and h is the Planck constant. Values of c range from 0.15 to 0.3 for most materials.[20]

Databases and automated prediction

[edit]In February 2011, Alfa Aesar released over 10,000 melting points of compounds from their catalog as open data[21] and similar data has been mined from patents.[22] The Alfa Aesar and patent data have been summarized in (respectively) random forest[21] and support vector machines.[22]

Melting point of the elements

[edit]| Group → | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ Period | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ① | H2 13.99 K (−259.16 °C) |

He[c] | |||||||||||||||||||

| ② | Li453.65 K (180.50 °C) |

Be1560 K (1287 °C) |

B 2349 K (2076 °C) |

C [d] |

N2 63.23 K (−209.86 °C) |

O2 54.36 K (−218.79 °C) |

F2 53.48 K (−219.67 °C) |

Ne24.56 K (−248.59 °C) | |||||||||||||

| ③ | Na370.944 K (97.794 °C) |

Mg923 K (650 °C) |

Al933.47 K (660.32 °C) |

Si1687 K (1414 °C) |

P 317.3 K (44.15 °C) |

S 388.36 K (115.21 °C) |

Cl2171.6 K (−101.5 °C) |

Ar83.81 K (−189.34 °C) | |||||||||||||

| ④ | K 336.7 K (63.5 °C) |

Ca1115 K (842 °C) |

Sc1814 K (1541 °C) |

Ti1941 K (1668 °C) |

V 2183 K (1910 °C) |

Cr2180 K (1907 °C) |

Mn1519 K (1246 °C) |

Fe1811 K (1538 °C) |

Co1768 K (1495 °C) |

Ni1728 K (1455 °C) |

Cu1357.77 K (1084.62 °C) |

Zn692.68 K (419.53 °C) |

Ga302.9146 K (29.7646 °C) |

Ge1211.40 K (938.25 °C) |

As[e] |

Se494 K (221 °C) |

Br2265.8 K (−7.2 °C) |

Kr115.78 K (−157.37 °C) | |||

| ⑤ | Rb312.45 K (39.30 °C) |

Sr1050 K (777 °C) |

Y 1799 K (1526 °C) |

Zr2128 K (1855 °C) |

Nb2750 K (2477 °C) |

Mo2896 K (2623 °C) |

Tc2430 K (2157 °C) |

Ru2607 K (2334 °C) |

Rh2237 K (1964 °C) |

Pd1828.05 K (1554.9 °C) |

Ag1234.93 K (961.78 °C) |

Cd594.22 K (321.07 °C) |

In429.7485 K (156.5985 °C) |

Sn505.08 K (231.93 °C) |

Sb903.78 K (630.63 °C) |

Te722.66 K (449.51 °C) |

I2 386.85 K (113.7 °C) |

Xe161.40 K (−111.75 °C) | |||

| ⑥ | Cs301.7 K (28.5 °C) |

Ba1000 K (727 °C) |

Lu1925 K (1652 °C) |

Hf2506 K (2233 °C) |

Ta3290 K (3017 °C) |

W 3695 K (3422 °C) |

Re3459 K (3186 °C) |

Os3306 K (3033 °C) |

Ir2719 K (2446 °C) |

Pt2041.4 K (1768.3 °C) |

Au1337.33 K (1064.18 °C) |

Hg234.3210 K (−38.8290 °C) |

Tl577 K (304 °C) |

Pb600.61 K (327.46 °C) |

Bi544.7 K (271.5 °C) |

Po527 K (254 °C) |

At575 K (302 °C) |

Rn202 K (−71 °C) | |||

| ⑦ | Fr300 K (27 °C) |

Ra973 K (700 °C) |

Lr1900 K (1627 °C) |

Rf2400 K (2100 °C) |

Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn283±11 K (10±11 °C) |

Nh700 K (430 °C) |

Fl200 K (−73 °C) |

Mc670 K (400 °C) |

Lv637–780 K (364–507 °C) |

Ts623–823 K (350–550 °C) |

Og325±15 K (52±15 °C) | |||

| La1193 K (920 °C) |

Ce1068 K (795 °C) |

Pr1208 K (935 °C) |

Nd1297 K (1024 °C) |

Pm1315 K (1042 °C) |

Sm1345 K (1072 °C) |

Eu1099 K (826 °C) |

Gd1585 K (1312 °C) |

Tb1629 K (1356 °C) |

Dy1680 K (1407 °C) |

Ho1734 K (1461 °C) |

Er1802 K (1529 °C) |

Tm1818 K (1545 °C) |

Yb1097 K (824 °C) | ||||||||

| Ac1500 K (1227 °C) |

Th2023 K (1750 °C) |

Pa1841 K (1568 °C) |

U 1405.3 K (1132.2 °C) |

Np912±3 K (639±3 °C) |

Pu912.5 K (639.4 °C) |

Am1449 K (1176 °C) |

Cm1613 K (1340 °C) |

Bk1259 K (986 °C) |

Cf1173 K (900 °C) |

Es1133 K (860 °C) |

Fm1800 K (1527 °C) |

Md1100 K (827 °C) |

No1100 K (827 °C) | ||||||||

| Notes | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Legend

Primordial From decay Synthetic Border shows natural occurrence of the element | |||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- Boiling point

- Congruent melting

- Hagedorn temperature

- Hafnium carbonitride, a compound with the highest known melting point

- List of elements by melting point

- Melting points of the elements (data page)

- Phase diagram

- Simon–Glatzel equation

- Slip melting point

- Triple point

- Zone melting

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Ramsay, J. A. (1 May 1949). "A New Method of Freezing-Point Determination for Small Quantities". Journal of Experimental Biology. 26 (1): 57–64. Bibcode:1949JExpB..26...57R. doi:10.1242/jeb.26.1.57. PMID 15406812.

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.122.

- ^ The melting point of purified water has been measured as 0.002519 ± 0.000002 °C, see Feistel, R. & Wagner, W. (2006). "A New Equation of State for H2O Ice Ih". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 35 (2): 1021–1047. Bibcode:2006JPCRD..35.1021F. doi:10.1063/1.2183324.

- ^ Kringle, Loni; Thornley, Wyatt A.; Kay, Bruce D.; Kimmel, Greg A. (18 September 2020). "Reversible structural transformations in supercooled liquid water from 135 to 245 K". Science. 369 (6510): 1490–1492. arXiv:1912.06676. Bibcode:2020Sci...369.1490K. doi:10.1126/science.abb7542. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 32943523.

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.123.

- ^ Hong, Q.-J.; van de Walle, A. (2015). "Prediction of the material with highest known melting point from ab initio molecular dynamics calculations". Phys. Rev. B. 92 (2): 020104(R). Bibcode:2015PhRvB..92b0104H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.92.020104.

- ^ Buinevich, V.S.; Nepapushev, A.A.; Moskovskikh, D.O.; Trusov, G.V.; Kuskov, K.V.; Vadchenko, S.G.; Rogachev, A.S.; Mukasyan, A.S. (March 2020). "Fabrication of ultra-high-temperature nonstoichiometric hafnium carbonitride via combustion synthesis and spark plasma sintering". Ceramics International. 46 (10): 16068–16073. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.03.158. S2CID 216437833.

- ^ Holman, S. W.; Lawrence, R. R.; Barr, L. (1 January 1895). "Melting Points of Aluminum, Silver, Gold, Copper, and Platinum". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 31: 218–233. doi:10.2307/20020628. JSTOR 20020628.

- ^ a b "Carbon". rsc.org.

- ^ "Latent heat | Definition, Examples, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 4 June 2024. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ The exact relationship is expressed in the Clausius–Clapeyron relation.

- ^ "J10 Heat: Change of aggregate state of substances through change of heat content: Change of aggregate state of substances and the equation of Clapeyron-Clausius". Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ Tonkov, E. Yu. and Ponyatovsky, E. G. (2005) Phase Transformations of Elements Under High Pressure, CRC Press, Boca Raton, p. 98 ISBN 0-8493-3367-9

- ^ Brown, R. J. C. & R. F. C. (2000). "Melting Point and Molecular Symmetry". Journal of Chemical Education. 77 (6): 724. Bibcode:2000JChEd..77..724B. doi:10.1021/ed077p724.

- ^ Haynes, pp. 6.153–155.

- ^ Gilman, H.; Smith, C. L. (1967). "Tetrakis(trimethylsilyl)silane". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 8 (2): 245–253. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)91037-4.

- ^ Lindemann FA (1910). "The calculation of molecular vibration frequencies". Phys. Z. 11: 609–612.

- ^ Sorkin, S., (2003), Point defects, lattice structure, and melting Archived 5 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Thesis, Technion, Israel.

- ^ Philip Hofmann (2008). Solid state physics: an introduction. Wiley-VCH. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-527-40861-0. Retrieved 13 March 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Nelson, D. R., (2002), Defects and geometry in condensed matter physics, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-00400-4

- ^ a b Bradley, Jean-Claude; Lang, Andrew; Williams, Antony; Curtin, Evan (11 August 2011). "ONS Open Melting Point Collection". Nature Precedings. doi:10.1038/npre.2011.6229.1. Model published on QsarDB retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ a b Tetko, Igor V; m. Lowe, Daniel; Williams, Antony J (2016). "The development of models to predict melting and pyrolysis point data associated with several hundred thousand compounds mined from PATENTS". Journal of Cheminformatics. 8 2. doi:10.1186/s13321-016-0113-y. PMC 4724158. PMID 26807157. Model[permanent dead link] published on OCHEM retrieved 18 June 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Works cited

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1439855119.

External links

[edit]- Melting and boiling point tables vol. 1 by Thomas Carnelley (Harrison, London, 1885–1887)

- Melting and boiling point tables vol. 2 by Thomas Carnelley (Harrison, London, 1885–1887)

- Patent mined data[permanent dead link] Over 250,000 freely downloadable melting point data. Also downloadable at figshare

Melting point

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Phase Transition

The melting point of a substance is defined as the temperature at which the solid and liquid phases coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium, typically measured at standard atmospheric pressure of 1 atm, marking the point where the solid begins to transform into a liquid without further temperature increase until the phase change is complete.[1][6] This characteristic temperature is a fundamental physical property for pure, crystalline solids, reflecting the conditions under which the Gibbs free energy of the two phases is equal (ΔG = 0 at T_m), allowing both phases to exist stably.[7] Melting represents a first-order phase transition, characterized by a discontinuous change in properties such as volume and entropy, accompanied by the absorption of latent heat known as the enthalpy of fusion (ΔH_fus).[8] During this process, the solid's ordered molecular structure breaks down into the more disordered liquid state, resulting in an increase in entropy (ΔS_fus > 0), where the entropy change is related to the enthalpy by ΔS_fus = ΔH_fus / T_m at the equilibrium temperature.[9][10] The transition occurs at constant temperature and pressure, with the system requiring energy input to overcome intermolecular forces, leading to the latent heat absorption without a rise in temperature. The slope of the melting curve in the phase diagram, which describes how the melting point varies with pressure, is given by the Clapeyron equation: where ΔV is the change in molar volume from solid to liquid (typically positive for most substances) and ΔS is the entropy change during fusion.[11] This relation highlights the interdependence of temperature and pressure at equilibrium, with increasing pressure generally raising the melting point for materials where the liquid occupies more volume than the solid. Early observations of melting points contributed to the development of temperature scales; in 1714, Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit calibrated his mercury thermometer using the melting point of ice at 32°F as a fixed reference, alongside other reproducible thermal events, establishing a basis for precise thermometry.[12][13]Importance in Science and Industry

In science, the melting point serves as a key indicator of the strength of intermolecular forces within a substance, with higher melting points generally reflecting stronger attractive forces that require more energy to overcome for phase transition.[14] It plays a central role in constructing phase diagrams, where the melting curve delineates the boundary between solid and liquid phases under varying temperature and pressure conditions, aiding in the prediction of material behavior.[15] Additionally, melting points are integral to cryoscopy, the study of freezing point depression in solutions, which leverages the relationship between solute concentration and lowered melting temperatures to determine molecular weights and solute properties.[16] These applications collectively enhance the understanding of molecular structures, as deviations in melting points from expected values reveal insights into purity, polymorphism, or structural irregularities in compounds.[17] In industry, melting points are essential for metallurgy, where they guide alloy design by influencing casting processes, phase stability, and the selection of compositions that achieve desired mechanical properties without unintended melting during use.[18] In pharmaceuticals, the melting point assesses drug stability and purity, ensuring that active ingredients withstand processing temperatures without degradation, particularly for high-melting-point compounds prone to instability during melt extrusion.[19] It also indicates the thermal resilience of drug lattices, informing formulation strategies to maintain efficacy over time.[5] Food science relies on melting points to optimize processing temperatures for fats, oils, and confectionery, enabling quality control in products like chocolate—where precise melting ensures texture and shelf stability—and dairy items, preventing adulteration or inconsistent melting behavior.[20] In electronics, high melting points of materials like silicon (1414°C) are critical for semiconductor fabrication, allowing wafers to endure high-temperature doping and annealing without structural failure.[21] Environmentally, melting points underpin climate science by defining thresholds for ice sheet stability; for instance, the gradual melting of Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, driven by rising temperatures exceeding their equilibrium points, has contributed approximately one-third to global sea-level rise observed from 2006 to 2015.[22] This process amplifies coastal flooding risks and ecosystem disruptions as meltwater influx alters ocean dynamics. The economic implications of melting points are profound in material selection for demanding sectors like aerospace, where high-melting-point alloys enable engine components to operate under extreme heat, reducing maintenance costs and enhancing fuel efficiency—potentially lowering overall production expenses by optimizing lightweight, durable designs.[23] Such choices drive innovations in high-temperature environments, balancing performance gains against energy-intensive manufacturing to achieve long-term cost savings.[24]Examples and Data

Common Substances

The melting point serves as a fundamental benchmark for phase transitions in common materials, illustrating how temperature drives the shift from solid to liquid states under standard atmospheric pressure. For organic compounds, water exemplifies this with its precise melting point of 0°C, where ice transitions to liquid, a value critical for environmental and biological processes.[25] Sucrose, the primary component of table sugar, melts at 186°C, though it often decomposes slightly before fully liquefying, highlighting the thermal sensitivity of carbohydrates.[1] Paraffin wax, used in candles and coatings, typically melts around 60°C, providing a low-temperature example of hydrocarbon-based solids that soften gradually over a range due to molecular weight variations.[26] Metals demonstrate higher melting points tied to their metallic bonding strength, influencing applications from construction to electronics. Iron melts at 1538°C, a temperature that defines steel production thresholds and industrial forging limits.[27] Aluminum, valued for its lightweight properties, reaches its melting point at 660°C, enabling efficient recycling and casting in manufacturing.[28] Gold, prized for jewelry, melts at 1064°C, reflecting its resistance to oxidation and stability at elevated temperatures.[29] Polymers like polyethylene illustrate the diversity in synthetic materials, with a melting point around 115°C for low-density variants, which broadens the utility of plastics in packaging while limiting their use in high-heat environments.[30] This range underscores how chain branching affects thermal behavior in polymers.| Substance | Melting Point (°C) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Water (ice) | 0 | Benchmark for aqueous phase equilibrium. |

| Sucrose | 186 | Decomposes near melting. |

| Paraffin wax | ~60 | Varies by composition (47–65°C range). |

| Iron | 1538 | Key for metallurgy. |

| Aluminum | 660 | Enables low-energy processing. |

| Gold | 1064 | High purity standard. |

| Polyethylene (LDPE) | ~115 | Represents plastic softening range. |

Melting Points of Elements

The melting points of the chemical elements span an enormous range, reflecting the diversity of bonding types and atomic structures across the periodic table. Helium exhibits the lowest melting point at 0.95 K (under ~25 atm pressure), while tungsten has the highest at 3695 K (3422 °C).[33] These extremes highlight how elements transition from gases and liquids at standard conditions to refractory solids capable of withstanding extreme temperatures. Periodic trends in melting points are pronounced, particularly among metals. For transition metals, melting points generally increase across a period due to stronger metallic bonding as atomic radius decreases and the number of delocalized electrons rises, enhancing lattice stability. Notable anomalies include mercury, with a melting point of -38.8 °C (234.3 K), resulting from relativistic effects that contract the 6s orbital and weaken metallic bonding. Nonmetals and metalloids often show lower values due to covalent or molecular structures, such as carbon's sublimate behavior, but graphite's effective melting point exceeds 4000 K under pressure. Several factors influence these melting points. Smaller atomic radii in later periods strengthen interatomic forces, while higher electronegativity in nonmetals favors directional covalent bonds over isotropic metallic ones, typically lowering melting points. Crystal structure plays a key role; for instance, body-centered cubic (BCC) lattices in metals like tungsten provide higher coordination and thus elevated melting points compared to face-centered cubic (FCC) structures in elements like copper. The following table lists the melting points of all 118 known elements, ordered by atomic number, with values in both Celsius and Kelvin. Data are drawn from standard compilations and represent normal melting points at standard pressure unless otherwise noted (e.g., helium requires pressure >1 atm; elements like carbon and arsenic sublime at 1 atm). Values for superheavy elements (atomic numbers 104–118) are largely theoretical or estimated due to their short half-lives and synthetic nature; melting points have not been experimentally determined as of 2025.[34]| Atomic Number | Symbol | Element | Melting Point (°C) | Melting Point (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | Hydrogen | -259.16 | 14.01 |

| 2 | He | Helium | -272.20 (0.95 at ~25 atm) | 0.95 (at ~25 atm) |

| 3 | Li | Lithium | 180.54 | 453.69 |

| 4 | Be | Beryllium | 1287 | 1560 |

| 5 | B | Boron | 2076 | 2349 |

| 6 | C | Carbon | Sublimes ~3650 (graphite at 1 atm; diamond ~3550 under high P) | ~3923 (graphite); ~3823 (diamond under P) |

| 7 | N | Nitrogen | -210.00 | 63.15 |

| 8 | O | Oxygen | -218.79 | 54.36 |

| 9 | F | Fluorine | -219.67 | 53.48 |

| 10 | Ne | Neon | -248.59 | 24.56 |

| 11 | Na | Sodium | 97.72 | 370.87 |

| 12 | Mg | Magnesium | 650.00 | 923.15 |

| 13 | Al | Aluminum | 660.32 | 933.47 |

| 14 | Si | Silicon | 1414 | 1687 |

| 15 | P | Phosphorus | 44.15 (white) | 317.30 |

| 16 | S | Sulfur | 115.21 (rhombic) | 388.36 |

| 17 | Cl | Chlorine | -100.98 | 172.17 |

| 18 | Ar | Argon | -189.34 | 83.81 |

| 19 | K | Potassium | 63.28 | 336.43 |

| 20 | Ca | Calcium | 842 | 1115 |

| 21 | Sc | Scandium | 1541 | 1814 |

| 22 | Ti | Titanium | 1668 | 1941 |

| 23 | V | Vanadium | 1910 | 2183 |

| 24 | Cr | Chromium | 1907 | 2180 |

| 25 | Mn | Manganese | 1246 | 1519 |

| 26 | Fe | Iron | 1538 | 1811 |

| 27 | Co | Cobalt | 1495 | 1768 |

| 28 | Ni | Nickel | 1455 | 1728 |

| 29 | Cu | Copper | 1084.62 | 1357.77 |

| 30 | Zn | Zinc | 419.53 | 692.68 |

| 31 | Ga | Gallium | 29.76 | 302.91 |

| 32 | Ge | Germanium | 938.25 | 1211.40 |

| 33 | As | Arsenic | Sublimes 615 (gray at 1 atm; 817 at 36 atm) | 888 (subl.); 1090 (at 36 atm) |

| 34 | Se | Selenium | 221 | 494 |

| 35 | Br | Bromine | -7.2 | 265.95 |

| 36 | Kr | Krypton | -157.4 | 115.75 |

| 37 | Rb | Rubidium | 39.31 | 312.46 |

| 38 | Sr | Strontium | 777 | 1050 |

| 39 | Y | Yttrium | 1522 | 1795 |

| 40 | Zr | Zirconium | 1855 | 2128 |

| 41 | Nb | Niobium | 2477 | 2750 |

| 42 | Mo | Molybdenum | 2623 | 2896 |

| 43 | Tc | Technetium | 2157 | 2430 |

| 44 | Ru | Ruthenium | 2334 | 2607 |

| 45 | Rh | Rhodium | 1964 | 2237 |

| 46 | Pd | Palladium | 1555 | 1828 |

| 47 | Ag | Silver | 961.78 | 1234.93 |

| 48 | Cd | Cadmium | 320.99 | 594.14 |

| 49 | In | Indium | 156.60 | 429.75 |

| 50 | Sn | Tin | 231.93 (white) | 505.08 |

| 51 | Sb | Antimony | 630.63 | 903.78 |

| 52 | Te | Tellurium | 449.51 | 722.66 |

| 53 | I | Iodine | 113.70 | 386.85 |

| 54 | Xe | Xenon | -111.75 | 161.40 |

| 55 | Cs | Cesium | 28.44 | 301.59 |

| 56 | Ba | Barium | 727 | 1000 |

| 57 | La | Lanthanum | 920 | 1193 |

| 58 | Ce | Cerium | 795 | 1068 |

| 59 | Pr | Praseodymium | 931 | 1204 |

| 60 | Nd | Neodymium | 1021 | 1294 |

| 61 | Pm | Promethium | 1042 | 1315 |

| 62 | Sm | Samarium | 1072 | 1345 |

| 63 | Eu | Europium | 822 | 1095 |

| 64 | Gd | Gadolinium | 1313 | 1586 |

| 65 | Tb | Terbium | 1356 | 1629 |

| 66 | Dy | Dysprosium | 1412 | 1685 |

| 67 | Ho | Holmium | 1474 | 1747 |

| 68 | Er | Erbium | 1529 | 1802 |

| 69 | Tm | Thulium | 1545 | 1818 |

| 70 | Yb | Ytterbium | 824 | 1097 |

| 71 | Lu | Lutetium | 1663 | 1936 |

| 72 | Hf | Hafnium | 2233 | 2506 |

| 73 | Ta | Tantalum | 3017 | 3290 |

| 74 | W | Tungsten | 3422 | 3695 |

| 75 | Re | Rhenium | 3186 | 3459 |

| 76 | Os | Osmium | 3033 | 3306 |

| 77 | Ir | Iridium | 2446 | 2719 |

| 78 | Pt | Platinum | 1768.3 | 2041.45 |

| 79 | Au | Gold | 1064.18 | 1337.33 |

| 80 | Hg | Mercury | -38.83 | 234.32 |

| 81 | Tl | Thallium | 304 | 577 |

| 82 | Pb | Lead | 327.46 | 600.61 |

| 83 | Bi | Bismuth | 271.40 | 544.55 |

| 84 | Po | Polonium | 254 | 527 |

| 85 | At | Astatine | 302 (est.) | 575 (est.) |

| 86 | Rn | Radon | -71 (est.) | 202 (est.) |

| 87 | Fr | Francium | 27 (est.) | 300 (est.) |

| 88 | Ra | Radium | 700 (est.) | 973 (est.) |

| 89 | Ac | Actinium | 1050 | 1323 |

| 90 | Th | Thorium | 1750 | 2023 |

| 91 | Pa | Protactinium | 1572 | 1845 |

| 92 | U | Uranium | 1132 | 1405 |

| 93 | Np | Neptunium | 644 | 917 |

| 94 | Pu | Plutonium | 640 | 913 |

| 95 | Am | Americium | 994 | 1267 |

| 96 | Cm | Curium | 1340 | 1613 |

| 97 | Bk | Berkelium | 986 | 1259 |

| 98 | Cf | Californium | 900 (est.) | 1173 (est.) |

| 99 | Es | Einsteinium | 860 (est.) | 1133 (est.) |

| 100 | Fm | Fermium | 1527 (est.) | 1800 (est.) |

| 101 | Md | Mendelevium | — | — |

| 102 | No | Nobelium | 827 (est.) | 1100 (est.) |

| 103 | Lr | Lawrencium | — | — |

| 104 | Rf | Rutherfordium | — | — |

| 105 | Db | Dubnium | — | — |

| 106 | Sg | Seaborgium | — | — |

| 107 | Bh | Bohrium | — | — |

| 108 | Hs | Hassium | — | — |

| 109 | Mt | Meitnerium | — | — |

| 110 | Ds | Darmstadtium | — | — |

| 111 | Rg | Roentgenium | — | — |

| 112 | Cn | Copernicium | — | — |

| 113 | Nh | Nihonium | — | — |

| 114 | Fl | Flerovium | — | — |

| 115 | Mc | Moscovium | — | — |

| 116 | Lv | Livermorium | — | — |

| 117 | Ts | Tennessine | — | — |

| 118 | Og | Oganesson | — | — |