Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hmong language

View on Wikipedia

This article should specify the language of its non-English content using {{lang}} or {{langx}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (May 2022) |

| Hmong | |

|---|---|

| Mong | |

| lus Hmoob / lug Moob / lol Hmongb / lus Hmôngz (Vietnam) / 𖬇𖬰𖬞 𖬌𖬣𖬵 / 𞄉𞄧𞄵𞄀𞄩𞄰 | |

| Pronunciation | [m̥ɔ̃́] |

| Native to | China, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Thailand |

| Ethnicity | Hmong |

Native speakers | 4.5 million[a] (2015)[1] |

| Hmong writing: incl. Pahawh Hmong, Nyiakeng Puachue Hmong, multiple Latin standards | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | hmn Hmong, Mong (China, Laos) |

| ISO 639-3 | hmn – inclusive code for the Hmong/Mong macrolanguage (China, Laos), including all Core Hmongic languages, except hmf and hmvIndividual codes: cqd – Chuanqiandian Cluster Miao (cover term for Hmong in China)hea – Northern Qiandong Miaohma – Southern Mashan Hmonghmc – Central Huishui Hmonghmd – Large Flowery Miaohme – Eastern Huishui Hmonghmf – Hmong Don (Vietnam)hmg – Southwestern Guiyang Hmonghmh – Southwestern Huishui Hmonghmi – Northern Huishui Hmonghmj – Gehml – Luopohe Hmonghmm – Central Mashan Hmonghmp – Northern Mashan Hmonghmq – Eastern Qiandong Miaohms – Southern Qiandong Miaohmv – Hmong Dô (Vietnam)hmw – Western Mashan Hmonghmy – Southern Guiyang Hmonghmz – Hmong Shua (Sinicized Miao)hnj – Mong Njua/Mong Leng (China, Laos), Blue/Green Hmong (United States)hrm – A-Hmo, Horned Miao (China)huj – Northern Guiyang Hmongmmr – Western Xiangxi Miaomuq – Eastern Xiangxi Miaomww – Hmong Daw (China, Laos), White Hmong (United States)sfm – Small Flowery Miao |

| Glottolog | firs1234 |

| Linguasphere | 48-AAA-a |

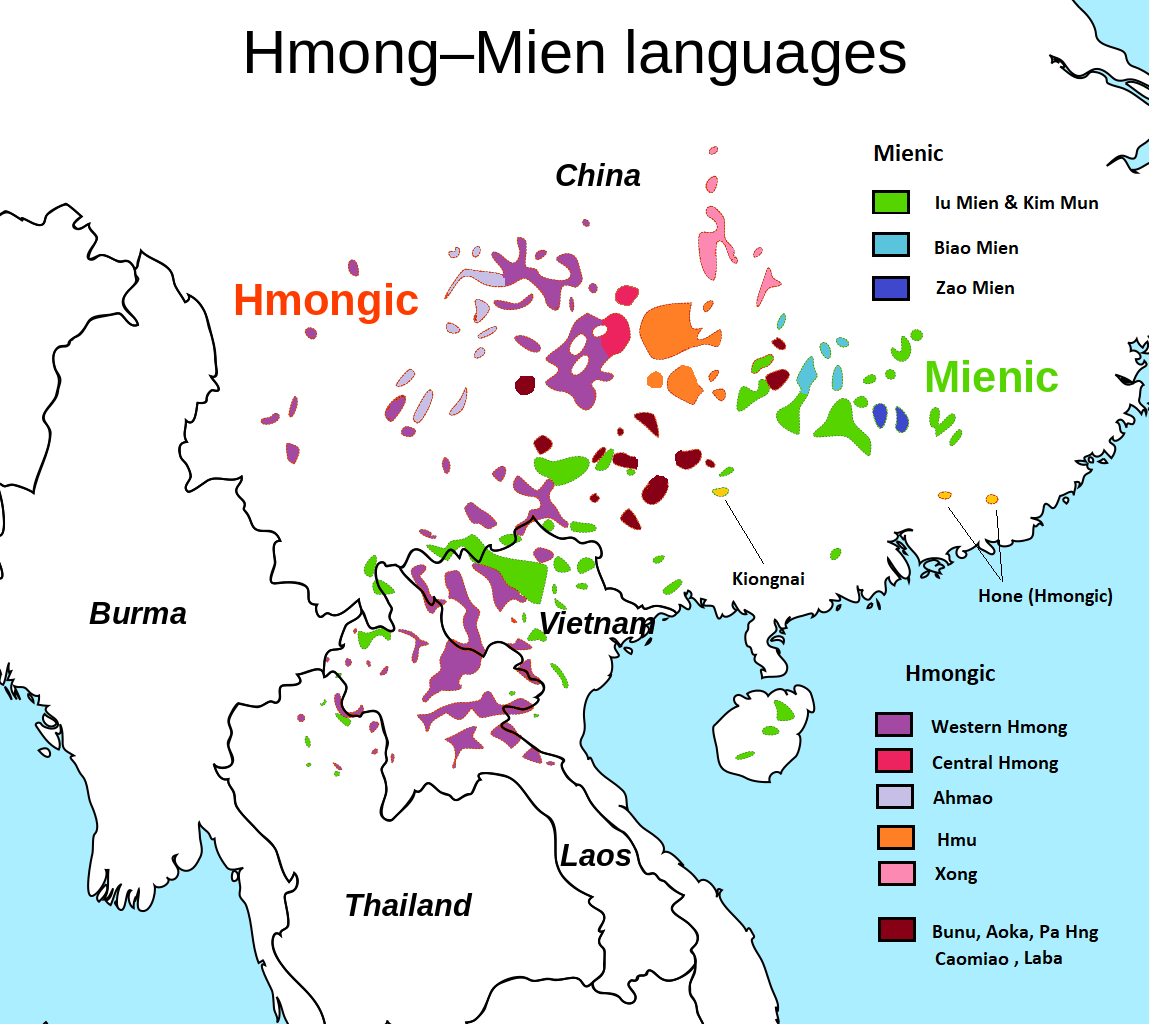

Map of Hmong-Mien languages, West Hmongic language in purple | |

Hmong or Mong (/ˈmʌŋ/ MUNG; RPA: Hmoob, CHV: Hmôngz, Nyiakeng Puachue: 𞄀𞄩𞄰, Pahawh: 𖬌𖬣𖬵, [m̥ɔ̃́]) is a dialect continuum of the West Hmongic branch of the Hmongic languages spoken by the Hmong people of Southwestern China, northern Vietnam, Thailand, and Laos.[2] There are an estimated 4.5 million speakers of varieties that are largely mutually intelligible, including over 280,000 Hmong Americans as of 2013.[3][4] Over half of all Hmong speakers speak the various dialects in China, where the Dananshan dialect forms the basis of the standard language.[5] However, Hmong Daw and Mong Leng are widely known only in Laos and the United States; Dananshan is more widely known in the native region of Hmong.

Varieties

[edit]Mong Leng (Moob Leeg) and Hmong Daw (Hmoob Dawb) are part of a dialect cluster known in China as Chuanqiandian Miao (Chinese: 川黔滇苗; lit. 'Sichuan–Guizhou–Yunnan Miao'), called the "Chuanqiandian cluster" in English (or "Miao cluster" in other languages) since West Hmongic is also called Chuanqiandian Miao. The variety spoken from Sichuan in China to Thailand and Laos is referred to in China as the "First Local Variety" (第一土语) of the cluster. Mong Leng and Hmong Daw are just those varieties of the cluster that migrated to Laos. The names Mong Leng, Hmong Dleu/Der, and Hmong Daw are also used in China for various dialects of the cluster.

Ethnologue once distinguished only the Laotian varieties (Hmong Daw, Mong Leng), Sinicized Miao (Hmong Shua), and the Vietnamese varieties (Hmong Dô, Hmong Don). The Vietnamese varieties are very poorly known; population estimates are not even available. In 2007, Horned Miao, Small Flowery Miao, and the Chuanqiandian cluster of China were split off from Mong Leng [blu].[6]

These varieties are as follows, along with some alternative names.

- Hmong/Mong/Chuanqiandian Miao macrolanguage (China, Laos, also spoken by minorities in Thailand and the United States), including:

- Hmong Daw (Hmong Der, Hmoob Dawb, Hmong Dleu, Hmongb Dleub, 'White Hmong'; Chinese: 白苗, Bái Miáo, 'White Miao'),

- Mong Leng (Moob Leeg, Moob Ntsuab, Mongb Nzhuab, 'Blue/Green Hmong'; Chinese: 青苗, Qīng Miáo, 'Blue-Green Miao'),

- Hmong Shua (Hmongb Shuat; 'Sinicized Miao'),

- Hmo or A-Hmo (Chinese: 角苗, Jiǎo Miáo, 'Horned Miao'),

- Small Flowery Miao,

- and the rest of the Chuanqiandian Miao cluster located in China.

- Hmong languages of Vietnam, not considered part of the China/Laos macrolanguage and possibly forming their own distinct macrolanguage — they are still not very well classified even if they are described by Ethnologue as having vigorous use (in Vietnam) but without population estimates; they have most probably been influenced by Vietnamese, as well as by French (in the former Indochina colonies) and later American English, and they may be confused with varieties spoken by minorities living today in the United States, Europe or elsewhere in Asia (where their varieties may have been assimilated locally, but separately in each area, with other Hmong varieties imported from Laos and China):

- Hmong Dô (Vietnam),

- Hmong Don (Vietnam, assumed).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stated that the White and Leng dialects "are said to be mutually intelligible to a well-trained ear, with pronunciation and vocabulary differences analogous to the differences between British and American English."[7]

Several Chinese varieties may overlap with or be more distinct than the varieties listed above:

- Dananshan Miao (Hmong Drout Raol, Hmong Hout Lab; called Hmong Dou in Northern Hmong), the basis of the Chinese standard of the Chuanqiandian cluster

- Black Miao (subgroups: Hmong Dlob, Hmong Buak/Hmoob Puas; Chinese: 黑苗, Hēi Miáo)[8]

- Southern Hmong (subgroups: Hmongb Shib, Hmongb Lens, Hmongb Dlex Nchab, Hmongb Sad; includes Mong Leng)

- Northern Hmong (subgroups: Hmongb Soud, Hmong Be/Hmongb Bes, Hmongb Ndrous)

- Western Sichuan Miao (Chinese: 川苗, Chuān Miáo)

In the 2007 request to establish an ISO code for the Chuanqiandian cluster, corresponding to the "first local dialect" (第一土语) of the Chuanqiandian cluster in Chinese, the proposer made the following statement on mutual intelligibility:

A colleague has talked with speakers of a number of these closely-related lects in the US, in Thailand and in China, and has had many discussions with Chinese linguists and foreign researchers or community development workers who have had extensive contact with speakers of these lects. As a result of these conversations this colleague believes that many of these lects are likely to have high inherent mutual intelligibility within the cluster. Culturally, while each sub-group prides itself on its own distinctives, they also recognize that other sub-groups within this category are culturally similar to themselves and accept the others as members of the same general ethnic group. However, this category of lects is internally varied and geographically scattered and mixed over a broad land area, and comprehensive intelligibility testing would be required to confirm reports of mutual intelligibility throughout the cluster.[9]

Varieties in Laos

[edit]According to the CDC, "although there is no official preference for one dialect over the other, White Hmong seems to be favored in many ways":[7] the Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA) most closely reflects that of White Hmong (Hmong Daw); most educated Hmong speak White Hmong because White Hmong people lack the ability to understand Mong Leng; and most Hmong dictionaries only include the White Hmong dialect. Furthermore, younger generations of Hmong are more likely to speak White Hmong, and speakers of Mong Leng are more likely to understand White Hmong than speakers of White Hmong are to understand Mong Leng.[7]

Varieties in the United States

[edit]Most Hmong in the United States speak White Hmong (Hmoob Dawb) and Mong Leng (Moob Leeg), with around 60% speaking White Hmong and 40% Mong Leng. The CDC states that "though some Hmong report difficulty understanding speakers of a dialect not their own, for the most part, Mong Leng seem to do better when understanding both dialects."[7]

Phonology

[edit]The three dialects described here are Hmong Daw (also called White Miao or Hmong Der),[10] Mong Leeg (also called Blue/Green Miao or Mong Leng),[11] and Dananshan (Standard Chinese Miao).[12] Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg are the two major dialects spoken by Hmong Americans. Although mutually intelligible, the dialects differ in both lexicon and certain aspects of phonology. For instance, Mong Leeg lacks the voiceless/aspirated /m̥/ of Hmong Daw (as exemplified by their names) and has a third nasalized vowel, /ã/; Dananshan has a couple of extra diphthongs in native words, numerous Chinese loans, and an eighth tone.

Vowels

[edit]The vowel systems of Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg are as shown in the following charts.[13] (Phonemes particular to Hmong Daw† and Mong Leeg‡ are color-coded and indicated by a dagger or double dagger respectively.)

- 1st Row: IPA, Hmong RPA

- 2nd Row: Nyiakeng Puachue

- 3rd Row: Pahawh

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close | ⓘ

i ⟨i⟩ |

ⓘ

ɨ ⟨w⟩ |

ⓘ

u ⟨u⟩ |

|||

| Mid | ⓘ

e ⟨e⟩ |

ⓘ

ẽ~eŋ ⟨ee⟩ |

ⓘ

ɔ ⟨o⟩ |

ⓘ

ɔ̃~ɔŋ ⟨oo⟩ | ||

| Open | ⓘ

a ⟨a⟩ |

ⓘ

ã~aŋ ⟨aa⟩ |

||||

| Closing | Centering | |

|---|---|---|

| Close component is front | ⓘ

ai ⟨ai⟩ |

ⓘ

iə ⟨ia⟩ |

| Close component is central | ⓘ

aɨ ⟨aw⟩ |

|

| Close component is back | ⓘ

au ⟨au⟩ |

ⓘ

uə ⟨ua⟩ |

The Dananshan standard of China is similar. Phonemic differences from Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg are color-coded and marked as absent or added.

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | nasal | oral | nasal | oral | nasal | |

| Close | i | (ɨ) (added) | u | |||

| Mid | e | en | o | oŋ | ||

| Open | a | aŋ | ||||

| Closing | Centering | |

|---|---|---|

| Close component is front | aj ⟨ai⟩ | (absent) |

| Close component is back | aw ⟨au⟩ | wɒ ⟨ua⟩ |

| əw ⟨ou⟩ eβ ⟨eu⟩ (added) |

Dananshan [ɨ] occurs only after non-palatal affricates, and is written ⟨i⟩, much like Mandarin Chinese. /u/ is pronounced [y] after palatal consonants. There is also a triphthong /jeβ/ ⟨ieu⟩, as well as other i- and u-initial sequences in Chinese borrowings, such as /waj/.

Consonants

[edit]Hmong makes a number of phonemic contrasts unfamiliar to English speakers. All non-glottal stops and affricates distinguish aspirated and unaspirated forms, and most also distinguish prenasalization independently of this. The consonant inventory of Hmong is shown in the chart below. (Consonants particular to Hmong Daw† and Mong Leeg‡ are color-coded and indicated by a dagger or double dagger respectively.)

- 1st Row: IPA, Hmong RPA

- 2nd Row: Nyiakeng Puachue

- 3rd Row: Pahawh

| Labial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral* | plain | sibilant | lateral* | plain | sibilant | ||||||

| Nasal | voiceless | m̥ ⟨hm⟩ 𞄀𞄄 𖬣𖬵† |

(m̥ˡ) ⟨hml⟩ 𞄠𞄄 𖬠𖬰† |

n̥ ⟨hn⟩ 𞄅𞄄 𖬩† |

ɲ̥ ⟨hny⟩ 𞄐𞄄 𖬣𖬰† |

|||||||

| voiced | m ⟨m⟩ 𞄀 𖬦 |

(mˡ) ⟨ml⟩ 𞄠 𖬠 |

n ⟨n⟩ 𞄅 𖬬 |

ɲ ⟨ny⟩ 𞄐 𖬮𖬵 |

(ŋ ⟨g⟩ marginal[14]) |

⟨ɴ⟩ 𞄢 |

||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate |

tenuis | p ⟨p⟩ 𞄚 𖬪𖬵 |

(pˡ) ⟨pl⟩ 𞄡 𖬟𖬵 |

t ⟨t⟩ 𞄃 𖬧𖬵 |

ts ⟨tx⟩ 𞄔 𖬯𖬵 |

(tˡ) ⟨dl⟩ 𞄏 𖬭𖬰‡ |

ʈ ⟨r⟩ 𞄖 𖬡 |

tʂ ⟨ts⟩ 𞄁 𖬝𖬰 |

c ⟨c⟩ 𞄈 𖬯 |

k ⟨k⟩*** 𞄎 |

q ⟨q⟩ 𞄗 𖬦𖬵 |

ʔ ⟨au⟩ 𞄠 𖬮𖬰 |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨ph⟩ 𞄚𞄄 𖬝𖬵 |

(pˡʰ) ⟨plh⟩ 𞄡𞄄 𖬪 |

tʰ ⟨th⟩ 𞄃𞄄 𖬟𖬰 |

tsʰ ⟨txh⟩ 𞄔𞄄 𖬦𖬰 |

(tˡʰ) ⟨dlh⟩ 𞄏𞄄 𖬭𖬵‡ |

ʈʰ ⟨rh⟩ 𞄖𞄄 𖬢𖬵 |

tʂʰ ⟨tsh⟩ 𞄁𞄄 𖬪𖬰 |

cʰ ⟨ch⟩ 𞄈𞄄 𖬧 |

kʰ ⟨kh⟩ 𞄎𞄄 𖬩𖬰 |

qʰ ⟨qh⟩ 𞄗𞄄 𖬣 |

||

| voiced | d ⟨d⟩ 𞄏 𖬞𖬰† |

|||||||||||

| murmured | dʱ ⟨dh⟩ 𞄏𞄄 𖬞𖬵† |

|||||||||||

| prenasalized** | ᵐb ⟨np⟩ 𞄜 𖬨𖬵 |

(ᵐbˡ) ⟨npl⟩ 𞄞 𖬫𖬰 |

ⁿd ⟨nt⟩ 𞄂 𖬩𖬵 |

ⁿdz ⟨ntx⟩ 𞄓 𖬢𖬰 |

(ⁿdˡ) ⟨ndl⟩ 𞄝 𖬭‡ |

ᶯɖ ⟨nr⟩ 𞄑 𖬜𖬰 |

ᶯdʐ ⟨nts⟩ 𞄍 𖬝 |

ᶮɟ ⟨nc⟩ 𞄌 𖬤𖬰 |

ᵑɡ ⟨nk⟩ 𞄇 𖬢 |

ᶰɢ ⟨nq⟩ 𞄙 𖬬𖬰 |

||

| ᵐpʰ ⟨nph⟩ 𞄜𞄄 𖬡𖬰 |

(ᵐpˡʰ) ⟨nplh⟩ 𞄞𞄄 𖬡𖬵 |

ⁿtʰ ⟨nth⟩ 𞄂𞄄 𖬫 |

ⁿtsʰ ⟨ntxh⟩ 𞄓𞄄 𖬥𖬵 |

(ⁿtˡʰ) ⟨ndlh⟩ 𞄝𞄄 𖬭𖬴‡ |

ᶯʈʰ ⟨nrh⟩ 𞄑𞄄 𖬨𖬰 |

ᶯtʂʰ ⟨ntsh⟩ 𞄍𞄄 𖬯𖬰 |

ᶮcʰ ⟨nch⟩ 𞄌𞄄 𖬨 |

ᵑkʰ ⟨nkh⟩ 𞄇𞄄 𖬫𖬵 |

ᶰqʰ ⟨nqh⟩ 𞄙𞄄 𖬬𖬵 |

|||

| Continuant | voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ 𞄕 𖬜𖬵 |

s ⟨x⟩ 𞄆 𖬮 |

l̥ ⟨hl⟩ 𞄄𞄉 𖬥 |

ʂ ⟨s⟩ 𞄊 𖬤𖬵 |

ɕ ~ ç ⟨xy⟩ 𞄛 𖬧𖬰 |

h ⟨h⟩ 𞄄 𖬟 | |||||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ 𞄒 𖬜 |

l ⟨l⟩ 𞄉 𖬞 |

ʐ ⟨z⟩ 𞄋 𖬥𖬰 |

ʑ ~ ʝ ⟨y⟩ 𞄘 𖬤 |

||||||||

| Approximant | ⟨ɻ⟩ 𞄣 |

|||||||||||

The Dananshan standard of China is similar. (Phonemic differences from Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg are color-coded and marked as absent or added. Minor differences, such as the voicing of prenasalized stops, or whether /c/ is an affricate or /h/ is velar, may be a matter of transcription.) Aspirates, voiceless fricatives, voiceless nasals, and glottal stop only occur with yin tones (1, 3, 5, 7). Standard orthography is added in angled brackets. The glottal stop is not written; it is not distinct from a zero initial. There is also a /w/, which occurs only in foreign words.

| Labial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral* | plain | sibilant | lateral* | plain | sibilant | ||||||

| Nasal | voiceless | m̥ ⟨hm⟩ | (absent) | n̥ ⟨hn⟩ | ɲ̥ ⟨hni⟩ | |||||||

| voiced | m ⟨m⟩ | (absent) | n ⟨n⟩ | ɲ ⟨ni⟩ | ŋ ⟨ngg⟩ (added) | |||||||

| Plosive/ Affricate | tenuis | p ⟨b⟩ | (pˡ) ⟨bl⟩ | t ⟨d⟩ | ts ⟨z⟩ | (tˡ) ⟨dl⟩ | ʈ ⟨dr⟩ | tʂ ⟨zh⟩ | tɕ ⟨j⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ | q ⟨gh⟩ | (ʔ) |

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨p⟩ | (pˡʰ) ⟨pl⟩ | tʰ ⟨t⟩ | tsʰ ⟨c⟩ | (tˡʰ) ⟨tl⟩ | ʈʰ ⟨tr⟩ | tʂʰ ⟨ch⟩ | tɕʰ ⟨q⟩ | kʰ ⟨k⟩ | qʰ ⟨kh⟩ | ||

| voiced | (absent) | |||||||||||

| prenasalized** | ᵐp ⟨nb⟩ | (ᵐpˡ) ⟨nbl⟩ | ⁿt ⟨nd⟩ | ⁿts ⟨nz⟩ | (absent) | ᶯʈ ⟨ndr⟩ | ᶯtʂ ⟨nzh⟩ | ⁿtɕ ⟨nj⟩ | ᵑk ⟨ng⟩ | ᶰq ⟨ngh⟩ | ||

| ᵐpʰ ⟨np⟩ | (ᵐpˡʰ) ⟨npl⟩ | ⁿtʰ ⟨nt⟩ | ⁿtsʰ ⟨nc⟩ | (absent) | ᶯʈʰ ⟨ntr⟩ | ᶯtʂʰ ⟨nch⟩ | ⁿtɕʰ ⟨nq⟩ | ᵑkʰ ⟨nk⟩ | ᶰqʰ ⟨nkh⟩ | |||

| Continuant | voiceless | f ⟨f⟩ | s ⟨s⟩ | l̥ ⟨hl⟩ | ʂ ⟨sh⟩ | ɕ ⟨x⟩ | x ⟨h⟩ | |||||

| voiced | v ⟨v⟩ | l ⟨l⟩ | ʐ ⟨r⟩ | ʑ ~ ʝ ⟨y⟩ | (w) | |||||||

^* The status of the consonants described here as single phonemes with lateral release is controversial. A number of scholars instead analyze them as biphonemic clusters with /l/ as the second element. The difference in analysis (e.g., between /pˡ/ and /pl/) is not based on any disagreement in the sound or pronunciation of the consonants in question, but on differing theoretical grounds. Those in favor of a unit-phoneme analysis generally argue for this based on distributional evidence (i.e., if clusters, these would be the only clusters in the language, although see below) and dialect evidence (the laterally released dentals in Mong Leeg, e.g. /tˡʰ/, correspond to the voiced dentals of White Hmong), whereas those in favor of a cluster analysis tend to argue on the basis of general phonetic principles (other examples of labial phonemes with lateral release appear extremely rare or nonexistent[15]).

^** Some linguists prefer to analyze the prenasalized consonants as clusters whose first element is /n/. However, this cluster analysis is not as common as the above one involving /l/.

^*** Only used in Hmong RPA and not in Pahawh Hmong, since Hmong RPA uses Latin script and Pahawh Hmong does not. For example, in Hmong RPA, to write keeb, the order Consonant + Vowel + Tone (CVT) must be followed, so it is k + ee + b = keeb, but in Pahawh Hmong, it is just Keeb "𖬀" (3rd-Stage Version).

Syllable structure

[edit]Hmong syllables have simple structure: all syllables have an onset consonant (except in a few particles[16]), nuclei may consist of a monophthong or diphthong, and the only coda consonants that occur are nasals. In Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg, nasal codas have become nasalized vowels, though they may be accompanied by weakly articulated [ŋ].[17] Similarly, a short [ʔ] may accompany the low-falling creaky tone.

Dananshan has a syllabic /l̩/ (written ⟨l⟩) in Chinese loans, such as lf 'two' and lx 'child'.

Tones

[edit]Hmong is a tonal language and makes use of seven (Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg) or eight (Dananshan) distinct tones.

| Tone | Hmong Daw example[18] | Hmong/Mong RPA spelling | Vietnamese Hmong spelling | Nyiakeng Puachue | Pahawh Hmong |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High ˥ | /pɔ́/ 'ball' | pob ⓘ | poz | 𞄚𞄨𞄰 | 𖬒𖬰𖬪𖬵 |

| Mid ˧ | /pɔ/ 'spleen' | po ⓘ | po | 𞄚𞄨 | 𖬓𖬰𖬪𖬵 |

| Low ˩ | /pɔ̀/ 'thorn' | pos ⓘ | pos | 𞄚𞄨𞄴 | 𖬓𖬲𖬪𖬵 |

| High-falling ˥˧ | /pɔ̂/ 'female' | poj ⓘ | pox | 𞄚𞄨𞄲 | 𖬒𖬲𖬪𖬵 |

| Mid-rising ˧˦ | /pɔ̌/ 'to throw' | pov ⓘ | por | 𞄚𞄨𞄳 | 𖬒𖬶𖬪𖬵 |

| Low checked (creaky) tone ˩ (phrase final: long low rising ˨˩˧) |

/pɔ̰̀/ 'to see' | pom ⓘ | pov | 𞄚𞄨𞄱 | 𖬒𖬪𖬵 |

| Mid-falling breathy tone ˧˩ | /pɔ̤̂/ 'grandmother' | pog ⓘ | pol | 𞄚𞄨𞄵 | 𖬓𖬪𖬵 |

The Dananshan tones are transcribed as pure tone. However, given how similar several of them are, it is likely that there are also phonational differences as in Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg. Tones 4 and 6, for example, are said to make tenuis plosives breathy voiced (浊送气), suggesting they may be breathy/murmured like the Hmong g-tone. Tones 7 and 8 are used in early Chinese loans with entering tone, suggesting they may once have marked checked syllables.

Because voiceless consonants apart from tenuis plosives are restricted to appearing before certain tones (1, 3, 5, 7), those are placed first in the table:

| Tone | IPA | Orthography |

|---|---|---|

| 1 high falling | ˦˧ 43 | b |

| 3 top | ˥ 5 | d |

| 5 high | ˦ 4 | t |

| 7 mid | ˧ 3 | k |

| 2 mid falling | ˧˩ 31 | x |

| 4 low falling (breathy) | ˨˩̤ 21 | l |

| 6 low rising (breathy) | ˩˧̤ 13 | s |

| 8 mid rising | ˨˦ 24 | f |

So much information is conveyed by the tones that it is possible to speak intelligibly using musical tunes only; there is a tradition of young lovers communicating covertly playing a Jew's harp to convey vowel sounds.[19]

Orthography

[edit]Robert Cooper, an anthropologist, collected a Hmong folktale saying that the Hmong used to have a written language, and important information was written down in a treasured book. The folktale explains that cows and rats ate the book, so, in the words of Anne Fadiman, author of The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, "no text was equal to the task of representing a culture as rich as that of the Hmong." Therefore, the folktale states that the Hmong language was exclusively oral from that point onwards.[20]

Natalie Jill Smith, author of "Ethnicity, Reciprocity, Reputation and Punishment: An Ethnoexperimental Study of Cooperation among the Chaldeans and Hmong of Detroit (Michigan)", wrote that the Qing Dynasty had caused a previous Hmong writing system to die out when it stated that the death penalty would be imposed on those who wrote it down.[21]

Since the end of the 19th century, linguists created over two dozen Hmong writing systems, including systems using Chinese characters, the Lao alphabet, the Cyrillic script, the Thai alphabet, and the Vietnamese alphabet. In addition, in 1959 Shong Lue Yang, a Hmong spiritual leader from Laos, created an 81 symbol writing system called Pahawh. Yang was not previously literate in any language. Chao Fa, an anti-Laotian government Hmong group, uses this writing system.[20]

In the 1980s, Nyiakeng Puachue Hmong script was created by a Hmong Minister, Reverend Chervang Kong Vang, to be able to capture Hmong vocabulary clearly and also to remedy redundancies in the language as well as address semantic confusions that was lacking in other scripts. Nyiakeng Puachue Hmong script was mainly used by United Christians Liberty Evangelical Church, a church also founded by Vang, although the script have been found to be in use in Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, France, and Australia.[citation needed] The script bears strong resemblance to the Lao alphabet in structure and form and characters inspired from the Hebrew alphabets, although the characters themselves are different.[22]

Other experiments by Hmong and non-Hmong orthographers have been undertaken using invented letters.[23]

The Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA), the most widely used script for Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg, was developed in Laos between 1951 and 1953 by three Western missionaries.[20] In the United States Hmong do not use RPA for spelling of proper nouns, because they want their names to be easily pronounced by people unfamiliar with RPA. For instance Hmong in the U.S. spell Hmoob as "Hmong," and Liab Lis is spelled as Lia Lee.[20]

The Dananshan standard in China is written in a pinyin-based alphabet, with tone letters similar to those used in RPA.

Correspondence between orthographies

[edit]The following is a list of pairs of RPA and Dananshan segments having the same sound (or very similar sounds). Note however that RPA and the standard in China not only differ in orthographic rules, but are also used to write different languages. The list is ordered alphabetically by the RPA, apart from prenasalized stops and voiceless sonorants, which come after their oral and voiced homologues. There are three overriding patterns to the correspondences: RPA doubles a vowel for nasalization, whereas pinyin uses ⟨ng⟩; RPA uses ⟨h⟩ for aspiration, whereas pinyin uses the voicing distinction of the Latin script; pinyin uses ⟨h⟩ (and ⟨r⟩) to derive the retroflex and uvular series from the dental and velar, whereas RPA uses sequences based on ⟨t, x, k⟩ vs. ⟨r, s, q⟩ for the same.

Vowels

[edit]| RPA | Pinyin | Vietnamese | Pahawh |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | 𖬖, 𖬗 | ||

| aa | ang | 𖬚, 𖬛 | |

| ai | 𖬊, 𖬋 | ||

| au | âu | 𖬄, 𖬅 | |

| aw | – | ơư | 𖬎, 𖬏 |

| e | ê | 𖬈, 𖬉 | |

| ee | eng | ênh | 𖬀, 𖬁 |

| – | eu | – | – |

| i | 𖬂, 𖬃 | ||

| ia | – | iê | 𖬔, 𖬕 |

| o | 𖬒, 𖬓 | ||

| oo | ong | ông | 𖬌, 𖬍 |

| – | ou | – | – |

| u | u | 𖬆, 𖬇 | |

| ua | uô | 𖬐, 𖬑 | |

| w | i | ư | 𖬘, 𖬙 |

Consonants

[edit]| RPA | Dananshan | Vietnamese | Pahawh |

|---|---|---|---|

| c | j | ch | 𖬯 |

| ch | q | 𖬧 | |

| nc | nj | nd | 𖬤𖬰 |

| nch | nq | 𖬨 | |

| d | – | đ | 𖬞𖬰 |

| dh | – | đh | 𖬞𖬵 |

| dl | đr | 𖬭𖬰 | |

| dlh | tl | đl | 𖬭𖬵 |

| ndl | – | nđr | 𖬭 |

| ndlh | – | nđl | 𖬭𖬴 |

| f | ph | 𖬜𖬵 | |

| h | 𖬟 | ||

| k | g | c | – |

| kh | k | kh | 𖬩𖬰 |

| nk | ng | g | 𖬢 |

| nkh | nk | nkh | 𖬫𖬵 |

| l | 𖬞 | ||

| hl | 𖬥 | ||

| m | 𖬦 | ||

| hm | 𖬣𖬵 | ||

| ml | – | mn | 𖬠 |

| hml | – | hmn | 𖬠𖬰 |

| n | 𖬬 | ||

| hn | hn | 𖬩 | |

| – | ngg | – | – |

| ny | ni | nh | 𖬮𖬵 |

| hny | hni | hnh | 𖬣𖬰 |

| p | b | p | 𖬪𖬵 |

| ph | p | ph | 𖬝𖬵 |

| np | nb | b | 𖬨𖬵 |

| nph | np | mf | 𖬡𖬰 |

| pl | bl | pl | 𖬟𖬵 |

| plh | pl | fl | 𖬪 |

| npl | nbl | bl | 𖬫𖬰 |

| nplh | npl | mfl | 𖬡𖬵 |

| q | gh | k | 𖬦𖬵 |

| qh | kh | qh | 𖬣 |

| nq | ngh | ng | 𖬬𖬰 |

| nqh | nkh | nkr | 𖬬𖬵 |

| r | dr | tr | 𖬡 |

| rh | tr | rh | 𖬢𖬵 |

| nr | ndr | r | 𖬜𖬰 |

| nrh | ntr | nr | 𖬨𖬰 |

| s | sh | s | 𖬤𖬵 |

| t | d | t | 𖬧𖬵 |

| th | t | th | 𖬟𖬰 |

| nt | nd | nt | 𖬩𖬵 |

| nth | nt | nth | 𖬫 |

| ts | zh | ts | 𖬝𖬰 |

| tsh | ch | tsh | 𖬪𖬰 |

| nts | nzh | nts | 𖬝 |

| ntsh | nch | ntsh | 𖬯𖬰 |

| tx | z | tx | 𖬯𖬵 |

| txh | c | cx | 𖬦𖬰 |

| ntx | nz | nz | 𖬢𖬰 |

| ntxh | nc | nx | 𖬥𖬵 |

| v | 𖬜 | ||

| – | w | – | – |

| x | s | x | 𖬮 |

| xy | x | sh | 𖬧𖬰 |

| y | z | 𖬤 | |

| z | r | j | 𖬥𖬰 |

There is no simple correspondence between the tone letters. The historical connection between the tones is as follows. The Chinese names reflect the tones given to early Chinese loan words with those tones in Chinese.

| Tone class |

Tone number |

Dananshan orthog. |

RPA | Vietnamese Hmong | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hmoob | Moob | ||||

| 平 or A | 1 | b ˦˧ | b ˥ | z | |

| 2 | x ˧˩ | j ˥˧ | x | ||

| 上 or B | 3 | d ˥ | v ˧˦ | r | |

| 4 | l ˨˩̤ | s | g | s | |

| 去 or C | 5 | t ˦ | (unmarked) ˧ | ||

| 6 | s ˩˧̤ | g ˧˩̤ | l | ||

| 入 or D | 7 | k ˧ | s ˩ | s | |

| 8 | f ˨˦ | m ˩̰ ~ d ˨˩˧ | v ~ k | ||

Tones 4 and 7 merged in Hmoob Dawb, whereas tones 4 and 6 merged in Mong Leeg.[24]

Example: lus Hmoob /̤ lṳ˧˩ m̥̥õ˦ / 𞄉𞄧𞄴𞄀𞄄𞄰𞄩 / (White Hmong) / lug Moob / 𞄉𞄧𞄵𞄀𞄩𞄰 / (Mong Leng) / lol Hmongb (Dananshan) / lus Hmôngz (Vietnamese) "Hmong language".

Grammar

[edit]Hmong is an analytic SVO language in which adjectives and demonstratives follow the noun.

Nouns

[edit]Noun phrases can contain the following elements (parentheses indicate optional elements):[25]

(possessive) + (quantifier) + (classifier) + noun + (adjective) + (demonstrative)

The Hmong pronominal system distinguishes between three grammatical persons and three numbers – singular, dual, and plural. They are not marked for case, that is, the same word is used to translate both "I" and "me", "she" and "her", and so forth. These are the personal pronouns of Hmong Daw and Mong Leeg:

- 1st Row: IPA, Hmong RPA

- 2nd Row: Vietnamese Hmong

- 3rd Row: Pahawh Hmong

- 4th Row: Nyiakeng Puachue

| Number: | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | kuv

cur 𞄎𞄧𞄳 |

wb

ưz 𞄬𞄰 |

peb

pêz 𞄚𞄪𞄰 |

| Second | koj

cox 𞄎𞄨𞄲 |

neb

nêz 𞄅𞄪𞄰 |

nej

nêx 𞄅𞄪𞄲 |

| Third | nws

nưs 𞄅𞄬𞄴 |

nkawd

gơưk 𞄇𞄤𞄶𞄬 |

lawv

lơưr 𞄉𞄤𞄳𞄬 |

| Number: | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | kuv

cur 𞄎𞄧𞄳 |

ib

iz 𞄦𞄰 |

peb

pêz 𞄚𞄪𞄰 |

| Second | koj

cox 𞄎𞄨𞄲 |

meb

mêz 𞄀𞄪𞄰 |

mej

mêx 𞄀𞄪𞄲 |

| Third | nwg

nưs 𞄅𞄬𞄵 |

ob tug

oz tus 𞄨𞄰𞄃𞄧𞄵 |

puab

puôz 𞄚𞄧𞄰𞄤 |

Classifiers

[edit]Classifiers are one of the features recurrently found in languages of Southeast Asia.[26] In Hmong, the noun does not directly follow a numeral, and a classifier or an adjective is required to count objects. Here are examples from Mong Leeg (Green Hmong):[27]

ob

𖬒𖬰𖬮𖬰

𞄨𞄰

two

tug

𖬇𖬲𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄶

CLF

dlev

𖬉𖬭𖬰

𞄝𞄪𞄳

dog

'two dogs'

ob

𖬒𖬰𖬮𖬰

𞄨𞄰

two

(tug)

(𖬇𖬲𖬧𖬵)

(𞄃𞄧𞄶)

CLF

nyuas

𖬑𖬲𖬮𖬵

𞄐𞄧𞄤𞄴

little

dlev

𖬉𖬭𖬰

𞄝𞄪𞄳

dog

'two little dogs'

Also, classifiers may occur with a noun without any numerals for definite and/or specific reference in Hmong.[28][29] The following examples are again from Green Hmong:[30]

kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

1SG

pum

𖬆𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄧𞄱

see

dlev

𖬉𖬭𖬰

𞄝𞄪𞄳

dog

'I saw dogs/a dog.' (indefinite and non-specific)

kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

1SG

pum

𖬆𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄧𞄱

see

tug

𖬇𖬲𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄶

CLF

dlev

𖬉𖬭𖬰

𞄝𞄪𞄳

dog

'I saw the dog.' (definite and specific)

kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

1SG

pum

𖬆𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄧𞄱

see

ib

𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰

𞄦𞄰

one

tug

𖬇𖬲𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄶

CLF

dlev

𖬉𖬭𖬰

𞄝𞄪𞄳

dog

'I saw a (specific) dog.' (indefinite and specific)

kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

1SG

pum

𖬆𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄧𞄱

see

ob

𖬒𖬰𖬮𖬰

𞄨𞄰

two

tug

𖬇𖬲𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄶

CLF

dlev

𖬉𖬭𖬰

𞄝𞄪𞄳

dog

hov

𖬒𖬶𖬟

𞄄𞄨𞄳

DEM:3

'I saw those two dogs.' (definite and specific)

Moreover, nominal possessive phrases are expressed with a classifier;[31] however, it may be omitted when the referent of the possessed noun is inalienable from the possessor as shown in the following Hmong Daw (White Hmong) phrases:[32]

nws

𖬙𖬲𖬬

𞄅𞄬𞄴

3SG

rab

𖬖𖬲𖬡

𞄖𞄤𞄰

CLF

ntaj

𖬖𖬰𖬩𖬵

𞄂𞄤𞄲

sword

'his sword'

kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

1SG

txiv

𖬂𖬶𖬯𖬵

𞄔𞄦𞄳

father

'my father'

Relativization is also expressed with classifiers.[32][33]

Although absent in Mandarin Chinese, definite reference by bare classifier constructions are found in Cantonese (Sinitic) and Zhuang (Kra-dai), which is the case for possessive classifier constructions as well.[34]

Verbs

[edit]Hmong is an isolating language in which most morphemes are monosyllables. As a result, verbs are not overtly inflected. Tense, aspect, mood, person, number, gender, and case are indicated lexically.[35]

Serial verb construction

[edit]Hmong verbs can be serialized, with two or more verbs combined in one clause. It is common for as many as five verbs to be strung together, sharing the same subject.

Here is an example from White Hmong:

Yam

Zav

𖬖𖬤

𞄘𞄤𞄱

Thing

zoo

jông

𖬍𖬥𖬰

𞄋𞄩

best

tshaj

tshax

𖬖𖬰𖬪𖬰

𞄁𞄄𞄤𞄲

very

plaws,

plơưs,

𖬏𖬰𖬟𖬵,

𞄡𞄤𞄬𞄴,

full,

nej

nêx

𖬈𖬲𖬬

𞄅𞄪𞄲

2PL

yuav

zuôr

𖬐𖬲𖬤

𞄘𞄧𞄤𞄳

IRR

tsum

tsuv

𖬆𖬝𖬰

𞄁𞄧𞄱

must

mus,

mus,

𖬇𖬰𖬦,

𞄀𞄧𞄴,

go,

nrhiav,

nriêz,

𖬔𖬲𖬨𖬰,

𞄑𞄄𞄦𞄤𞄳,

seek,

nug,

nuv,

𖬇𖬲𖬬,

𞄅𞄧𞄶,

ask,

xyuas,

shuôs,

𖬑𖬲𖬧𖬰,

𞄛𞄧𞄤𞄴,

examine,

saib

saiz

𖬊𖬰𖬤𖬵

𞄊𞄤𞄦𞄰

look

luag

luôv

𖬑𖬶𖬞

𞄉𞄧𞄤𞄶

others

muaj

muôj

𖬐𖬰𖬦

𞄀𞄧𞄤𞄲

have

kev

cêr

𖬉

𞄎𞄪𞄳

services

pab

paz

𖬖𖬲𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄤𞄰

variations

hom

hov

𖬒𖬟

𞄄𞄨𞄱

type

dab_tsi

đaz_tsi

𖬖𖬲𖬞𖬰_𖬃𖬝𖬰

𞄏𞄤𞄰_𞄁𞄦

what

nyob

nhoz

𖬒𖬰𖬮𖬵

𞄐𞄨𞄰

be.at

ncig

ndil

𖬃𖬲𖬤𖬰

𞄌𞄦𞄶

around

ib

ib

𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰

𞄦𞄰

one

cheeb_tsam

qênhz_tsav

𖬀𖬶𖬧_𖬖𖬝𖬰

𞄈𞄄𞄫𞄰_𞄁𞄤𞄱

area

ntawm

ntơưv

𖬎𖬰𖬩𖬵

𞄂𞄤𞄬𞄱

at

nej.

nêx.

𖬈𖬲𖬬.

𞄅𞄪𞄲.

2PL

'The best thing you can do is to explore your neighborhood and find out what services are available.'

Tense

[edit]Because the verb form in Hmong does not change to indicate tense, the simplest way to indicate the time of an event is to use temporal adverb phrases like "last year," "today," or "next week."

Here is an example from White Hmong:

Nag hmo

Nav hmo

𖬗𖬶𖬬 𖬓𖬰𖬣𖬵

𞄅𞄤𞄵 𞄀𞄄𞄨

yesterday

kuv

cur

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

I

mus

mus

𖬇𖬰𖬦

𞄀𞄧𞄴

go

tom

tov

𖬒𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄨𞄱

LOC

khw.

khư.

𖬙𖬰𖬩𖬰.

𞄎𞄄𞄬.

market

'I went to the market yesterday.'

Aspect

[edit]Aspectual differences are indicated by a number of verbal modifiers. Here are the most common ones:

Progressive: (Mong Leeg) taab tom + verb, (White Hmong) tab tom + verb = situation in progress

Puab

Puôz

𖬐𖬶𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄧𞄰𞄤

they

taab tom

tangz tov

𖬚𖬲𖬧𖬵 𖬒𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄥𞄰 𞄃𞄨𞄱

PROG

haus

hâus

𖬅𖬰𖬟

𞄄𞄤𞄴𞄨

drink

dlej.

đrêx

𖬈𖬲𖬭.

𞄏𞄪𞄲.

water

(Mong Leeg)

'They are drinking water.'

Taab/tab tom + verb can also be used to indicate a situation that is about to start. That is clearest when taab/tab tom occurs in conjunction with the irrealis marker yuav. Note that the taab tom construction is not used if it is clear from the context that a situation is ongoing or about to begin.

Perfective: sentence/clause + lawm = completed situation

Kuv

Cur

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

I

noj

nox

𖬒𖬲𖬬

𞄅𞄨𞄲

eat

mov

mor

𖬒𖬶𖬦

𞄀𞄨𞄳

rice

lawm.

lơưv

𖬎𖬰𖬞.

𞄉𞄤𞄱𞄬.

PERF

(Leeg and White Hmong)

'I am finished/I am done eating rice.' / 'I have already eaten "rice".'

Lawm at the end of a sentence can also indicate that an action is underway:

Tus

𖬇𖬰𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄴

CLF

tub

𖬆𖬰𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄰

boy

tau

𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄤𞄨

get

rab

𖬖𖬲𖬡

𞄖𞄤𞄰

CLF

hneev,

𖬀𖬲𖬩,

𞄅𞄄𞄳𞄫,

crossbow

nws

𖬙𖬲𖬬

𞄅𞄬𞄴

he

thiaj

𖬔𖬶𖬟𖬰

𞄃𞄄𞄦𞄲𞄤

then

mus

𖬇𖬰𖬦

𞄀𞄧𞄴

go

ua si

𖬑𖬮𖬰 𖬃𖬤𖬵

𞄧𞄤 𞄊𞄦

play

lawm.

𖬎𖬰𖬞.

𞄉𞄤𞄱𞄬.

PFV

(White Hmong)

'The boy got the crossbow and went off to play.' / 'The boy went off to play because he got the bow.'

Another common way to indicate the accomplishment of an action or attainment is by using tau, which, as a main verb, means 'to get/obtain.' It takes on different connotations when it is combined with other verbs. When it occurs before the main verb (i.e. tau + verb), it conveys the attainment or fulfillment of a situation. Whether the situation took place in the past, the present, or the future is indicated at the discourse level rather than the sentence level. If the event took place in the past, tau + verb translates to the past tense in English.

Lawv

𖬎𖬶𖬞

𞄉𞄤𞄳𞄬

they

tau

𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄤𞄨

attain

noj

𖬒𖬲𖬬

𞄅𞄨𞄲

eat

nqaij

𖬊𖬶𖬬𖬰

𞄙𞄤𞄲𞄦

meat

nyug.

𖬇𖬲𖬮𖬵.

𞄐𞄧𞄵.

beef

(White Hmong)

'They ate beef.'

Tau is optional if an explicit past time marker is present (e.g. nag hmo, last night). Tau can also mark the fulfillment of a situation in the future:

Thaum

𖬄𖬟𖬰

𞄃𞄄𞄤𞄱𞄨

when

txog

𖬓𖬯𖬵

𞄔𞄨𞄵

arrive

peb

𖬈𖬰𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄪𞄰

New

caug

𖬅𖬲𖬯

𞄈𞄤𞄵𞄨

Year

lawm

𖬎𖬰𖬞

𞄉𞄤𞄱𞄬

PFV

sawv daws

𖬎𖬶𖬤𖬵 𖬏𖬰𖬞𖬰

𞄊𞄤𞄳𞄬 𞄏𞄤𞄴𞄬

everybody

thiaj

𖬔𖬶𖬟𖬰

𞄃𞄄𞄦𞄲𞄤

then

tau

𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄤𞄨

attain

hnav

𖬗𖬩

𞄅𞄄𞄳𞄤

wear

khaub ncaws

𖬄𖬰𖬩𖬰 𖬏𖬰𖬤𖬰

𞄎𞄄𞄤𞄰𞄨 𞄌𞄤𞄴𞄬

clothes

tshiab.

𖬔𖬪𖬰.

𞄁𞄄𞄦𞄰𞄤.

new

(White Hmong)

'So when the New Year arrives, everybody gets to wear new clothes.'

When tau follows the main verb (i.e. verb + tau), it indicates the accomplishment of the purpose of an action.

Kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

I

xaav

𖬛𖬮

𞄆𞄥𞄳

think

xaav

𖬛𖬮

𞄆𞄥𞄳

think

ib plag,

𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬗𖬶𖬟𖬵,

𞄦𞄰 𞄡𞄤𞄵,

awhile,

kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

I

xaav

𖬛𖬮

𞄆𞄥𞄳

think

tau

𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄤𞄨

get

tswv yim.

𖬙𖬝𖬰 𖬂𖬤.

𞄁𞄬𞄳 𞄘𞄦𞄱.

idea

(Mong Leeg)

'I thought it over and got an idea.'

Tau is also common in serial verb constructions that are made up of a verb, followed by an accomplishment: (White Hmong) nrhiav tau, to look for; caum tau, to chase; yug tau, to give birth.

Mood

[edit]The grammatical marker yuav is analyzed by some scholars as a future tense marker[36][37] when it appears preceding a verb:

Yuav can also be analyzed as a marker of irrealis mood, for situations that are unfulfilled or unrealized.[38] That includes hypothetical or non-occurring situations with past, present, or future time references:

Tus

𖬇𖬰𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄴

CLF

Tsov

𖬒𖬶𖬝𖬰

𞄁𞄨𞄳

Tiger

hais tias,

𖬋𖬰𖬟 𖬕𖬰𖬧𖬵,

𞄄𞄤𞄴𞄦 𞄃𞄦𞄴𞄤,

say,

"Kuv

"𖬆𖬲

"𞄎𞄧𞄳

I

tshaib

𖬊𖬰𖬪𖬰

𞄁𞄄𞄤𞄰𞄦

hungry

tshaib

𖬊𖬰𖬪𖬰

𞄁𞄄𞄤𞄰𞄦

hungry

plab

𖬖𖬲𖬟𖬵

𞄡𞄤𞄰

stomach

li

𖬃𖬞

𞄉𞄦

INT

kuv

𖬆𖬲

𞄎𞄧𞄳

I

yuav

𖬐𖬲𖬤

𞄘𞄧𞄳𞄤

IRR

noj

𖬒𖬲𖬬

𞄅𞄨𞄲

eat

koj".

𖬒𖬲."

𞄎𞄨𞄲".

you

(from a White Hmong folk tale)

'The Tiger said, "I'm very hungry and I'm going to eat you.'

Tus

𖬇𖬰𖬧𖬵

𞄃𞄧𞄴

CLF

Qav

𖬗𖬦𖬵

𞄗𞄤𞄳

Frog

tsis

𖬃𖬰𖬝𖬰

𞄁𞄦𞄴

NEG

paub

𖬄𖬰𖬪𖬵

𞄚𞄤𞄰𞄨

know

yuav

𖬐𖬲𖬤

𞄘𞄧𞄳𞄤

IRR

ua

𖬑𖬮𖬰

𞄧𞄤

do

li

𖬃𖬞

𞄉𞄦

cas

𖬗𖬲𖬯

𞄈𞄤𞄴

what

li.

𖬃𖬞.

𞄉𞄦.

INT

'The frog didn't know what to do.'

Vocabulary

[edit]Overview

[edit]Hmong vocabulary comes from several sources: native Hmongic words, Chinese borrowings, and Tibeto-Burman borrowings,[39] as well as additional borrowings from the national languages where Hmong communities live outside China, including borrowings from Thai/Lao and English.[40]

Domains

[edit]Colors

[edit]Many Hmong and non-Hmong people who are learning the Hmong language tend to use the word xim (a borrowing from Thai/Lao) as the word for 'color', while the native Hmong word for 'color' is kob. For example, xim appears in the sentence Liab yog xim ntawm kev phom sij with the meaning "Red is the color of danger / The red color is of danger".

List of colors:

The following color terms are given as in Hmong Daw (HD; White Hmong) and Mong Leeg (ML; Green Hmong).

𖬔𖬞 liab (HD); 𖬖𖬲𖬞 lab (ML) 'red'

𖬐𖬶𖬝 ntsuab 'green'

𖬖𖬝𖬰 𖬈𖬮 tsam xem 'purple'

𖬆𖬰𖬞𖬰

dub (HD); 𖬆𖬰𖬭𖬰

dlub (ML) 'black'𖬔𖬲𖬮

xiav (HD); 𖬗𖬮

xav (ML) 'blue'𖬎𖬞𖬰

dawb (HD); 𖬎𖬭𖬰

dlawb (ML) 'white'𖬗𖬮𖬰 / 𖬗𖬲 𖬉𖬲𖬜𖬵 av / kas fes 'brown'

𖬖𖬰𖬞𖬰 daj (HD); dlaaj (ML) 'yellow'

𖬓𖬰𖬦𖬰 txho 'grey'

𖬖𖬲 𖬙𖬢𖬰

kab ntxwv (HD); 𖬚𖬲 𖬙𖬢𖬰

kaab ntxwv (ML) 'orange'𖬖𖬰𖬪𖬵 𖬀𖬶𖬤

paj yeeb (HD); 𖬚𖬰𖬪𖬵 𖬀𖬰𖬤

paaj yeeb (ML) 'pink'

Several of the Hmong terms for colors are native roots that date back to at least the Proto-Hmongic period, such as dub 'black', dawb 'white', and liab 'red', while daj 'yellow' was a very early borrowing from Chinese.[41] Several other terms are more recent innovations.

Numbers

[edit]| Numeral | Hmong Numeral | Pahawh Hmong | Hmong RPA | Hmong Loanwords | Pahawh Symbols |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 𖭐 | 𖬊𖬲𖬢𖬰 | Ntxaiv | Xoom (term from Thai/Lao)[42] | 𖭐 (Ones) |

| 1 | 𖭑 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Ib | ||

| 2 | 𖭒 | 𖬒𖬰𖬮𖬰 | Ob | ||

| 3 | 𖭓 | 𖬈𖬰𖬪𖬵 | Peb | ||

| 4 | 𖭔 | 𖬄𖬰𖬟𖬵 | Plaub | ||

| 5 | 𖭕 | 𖬂𖬲𖬝𖬰 | Tsib | ||

| 6 | 𖭖 | 𖬡 | Rau | ||

| 7 | 𖭗 | 𖬗𖬰𖬧𖬰 | Xya | ||

| 8 | 𖭘 | 𖬂𖬤 | Yim | ||

| 9 | 𖭙 | 𖬐𖬰𖬯 | Cuaj | ||

| 10 | 𖭑𖭐 | 𖬄 | Kaum | 𖭛 (Tens) | |

| 11 | 𖭑𖭑 | 𖬄 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Kaum ib | ||

| 20 | 𖭒𖭐 | 𖬁𖬰𖬬 𖬄𖬢 | Nees nkaum | ||

| 21 | 𖭒𖭑 | 𖬁𖬰𖬬 𖬄𖬢 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Nees nkaum ib | ||

| 30 | 𖭓𖭐 | 𖬈𖬰𖬪𖬵 𖬅𖬲𖬯 | Peb caug | ||

| 31 | 𖭓𖭑 | 𖬈𖬰𖬪𖬵 𖬅𖬲𖬯 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Peb caug ib | ||

| 40 | 𖭔𖭐 | 𖬄𖬰𖬟𖬵 𖬅𖬲𖬯 | Plaub caug | ||

| 41 | 𖭔𖭑 | 𖬄𖬰𖬟𖬵 𖬅𖬲𖬯 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Plaub caug ib | ||

| 50 | 𖭕𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬝𖬰 𖬅𖬲𖬯 | Tsib caug | ||

| 51 | 𖭕𖭑 | 𖬂𖬲𖬝𖬰 𖬅𖬲𖬯 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Tsib caug ib | ||

| 60 | 𖭖𖭐 | 𖬡 𖬄𖬯 | Rau caum | ||

| 61 | 𖭖𖭑 | 𖬡 𖬄𖬯 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Rau caum ib | ||

| 70 | 𖭗𖭐 | 𖬗𖬰𖬧𖬰 𖬄𖬯 | Xya caum | ||

| 71 | 𖭗𖭑 | 𖬗𖬰𖬧𖬰 𖬄𖬯 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Xya caum ib | ||

| 80 | 𖭘𖭐 | 𖬂𖬤 𖬄𖬯 | Yim caum | ||

| 81 | 𖭘𖭑 | 𖬂𖬤 𖬄𖬯 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Yim caum ib | ||

| 90 | 𖭙𖭐 | 𖬐𖬰𖬯 𖬄𖬯 | Cuaj caum | ||

| 91 | 𖭙𖭑 | 𖬐𖬰𖬯 𖬄𖬯 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 | Cuaj caum ib | ||

| 100 | 𖭑𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬑𖬲𖬪𖬵 | Ib puas | 𖭜 (Hundreds) | |

| 1,000 | 𖭑,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬔𖬦𖬰 | Ib txhiab | Ib phav (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭜𖭐 (Thousands) |

| 10,000 | 𖭑𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬄 𖬔𖬦𖬰 | Kaum txhiab | Kaum phav (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭝 (Ten thousand) |

| 100,000 | 𖭑𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬑𖬲𖬪𖬵 𖬔𖬦𖬰 | Ib puas txhiab | Ib puas phav (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭝𖭐 (Hundred Thousands) |

| 1,000,000 | 𖭑,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬌𖬡 | Ib roob | Ib lab (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭞 (Millions) |

| 10,000,000 | 𖭑𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬄 𖬌𖬡 | Kaum roob | Kaum lab (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭞𖭐 (Ten Millions) |

| 100,000,000 | 𖭑𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬑𖬲𖬪𖬵 𖬌𖬡 | Ib puas roob | Ib puas lab (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭟 (Hundred Millions) |

| 1,000,000,000 | 𖭑,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬈 | Ib kem | Ib phav lab (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭟𖭐 (Billions) |

| 10,000,000,000 | 𖭑𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬄 𖬈 | Kaum kem | Kaum phav lab (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭠 (Ten Billions) |

| 100,000,000,000 | 𖭑𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬑𖬲𖬪𖬵 𖬈 | Ib puas kem | Ib puas phav lab (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭠𖭐 (Hundred Billions) |

| 1,000,000,000,000 | 𖭑,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐,𖭐𖭐𖭐 | 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬗𖬧𖬵 | Ib tas | Ib lab lab (Thai/Lao word) | 𖭡 (Trillions) |

The number 57023 would be written as 𖭕𖭗𖭐𖭒𖭓.

Days of the week

[edit]| Days | Pahawh Hmong | Hmong RPA | Hmong Loanwords (from Thai/Lao) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | 𖬘𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬆𖬰𖬩 | Zwj hnub | Vas thiv |

| Monday | 𖬘𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬃𖬥 | Zwj hli | Vas cas |

| Tuesday | 𖬘𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬑𖬶𖬦𖬵 | Zwj quag | Vas as qhas |

| Wednesday | 𖬘𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬀𖬶𖬜𖬵 | Zwj feeb | Vas phuv |

| Thursday | 𖬘𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬀𖬶𖬧𖬵 | Zwj teeb | Vas phab hav |

| Friday | 𖬘𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬐𖬶 | Zwj kuab | Vas xuv |

| Saturday | 𖬘𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬗𖬶𖬯 | Zwj cag | Vas xom ~ Vas xaum[43] |

A sentence like "Today is Monday", using only non-borrowed, non-calqued terms, would be said Hnub no yog zwj hli, rather than Hnub no yog hnub ib/Monday in Hmong. However, Hmong speakers in English-speaking countries sometimes use Thai/Lao loanwords or English terms for the days of the week instead, as in Mong Leng ua ntej nub Saturday 'before Saturday'.[44]

Months of the year

[edit]| Months | Pahawh Hmong (Formal) | Hmong RPA | Informal |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 𖬀𖬰𖬤 𖬀𖬶𖬯 | Yeej ceeb | [Lub] Ib hlis |

| February | 𖬆𖬰 𖬀𖬶𖬮 | Kub xeeb | [Lub] Ob hlis |

| March | 𖬖𖬰𖬤 𖬔𖬲 | Yaj kiav | [Lub] Peb hlis |

| April | 𖬀 𖬒𖬯 | Keem com | [Lub] Plaub hlis |

| May | 𖬆𖬰 𖬆𖬶𖬬 | Kub nuj | [Lub] Tsib hlis |

| June | 𖬒𖬶𖬧𖬵 𖬔𖬶𖬞 | Tov liaj | [Lub] Rau hlis |

| July | 𖬐𖬰𖬟 𖬀𖬶𖬮 | Huaj xeeb | [Lub] Xya hlis |

| August | 𖬀𖬶𖬯 𖬑𖬯 | Ceeb cua | [Lub] Yim hlis |

| September | 𖬔𖬝𖬰 𖬆𖬰 𖬀𖬰𖬞 | Tsiab kub leej | [Lub] Cuaj hlis |

| October | 𖬀𖬪𖬵 𖬋𖬰𖬪𖬰 | Peem tshais | [Lub] Kaum hlis |

| November | 𖬌𖬲𖬞 𖬀𖬲 𖬀𖬦𖬰 | Looj keev txheem | [Lub] Kaum ib hlis |

| December | 𖬑𖬶𖬨𖬵 𖬎𖬯 | Npuag cawb | [Lub] Kaum ob hlis |

Worldwide usage

[edit]Presence in community and education

[edit]The Hmong language has found a significant presence in the United States, particularly in Minnesota. The Hmong people first arrived in Minnesota in late 1975 following the communist seizure of power in Indochina. Many educated Hmong elites with leadership experience and English-language skills were among the first to be welcomed by Minnesotans. These elites worked to solidify the social services targeted to refugees, attracting others to migrate to the region. The first Hmong family arrived in Minnesota on 5 November 1975.[45]

The Hmong language program in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Minnesota is one of the first programs in the United States to teach language-accredited Hmong classes.[46]

Translation

[edit]In February 2012, Microsoft released "Hmong Daw" as an option in Bing Translator.[47] In May 2013, Google Translate introduced support for Hmong Daw (referred to only as Hmong).[48]

Research in nursing shows that when translating from English to Hmong, the translator must take into account that Hmong comes from an oral tradition and equivalent concepts may not exist. For example, the word and concept for "prostate" does not exist.[49]

Sample texts

[edit]Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Hmong:

𖬑𖬦𖬰 𖬇𖬰𖬧𖬵 𖬁𖬲𖬬 𖬇𖬲𖬤 𖬓𖬲𖬞 𖬐𖬰𖬦 𖬉 𖬘𖬲𖬤 𖬀𖬰𖬝𖬵 𖬔𖬟𖬰 𖬂𖬲𖬤𖬵 𖬅𖬲𖬨𖬵 𖬓𖬲𖬥𖬰 𖬄𖬲𖬟 𖬒𖬲𖬯𖬵 𖬋𖬯. 𖬎𖬶𖬞 𖬖𖬰𖬮 𖬓𖬜𖬰 𖬆𖬰𖬞 𖬖𖬞𖬰 𖬎𖬲𖬟𖬰 𖬔𖬟𖬰 𖬆𖬰𖬞 𖬔𖬤𖬵 𖬔𖬟𖬰 𖬂𖬮𖬰 𖬁𖬲𖬞 𖬐𖬲𖬤 𖬆𖬝𖬰 𖬒𖬲𖬯 𖬅𖬮𖬰 𖬉𖬰 𖬎𖬰𖬩𖬵 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬁𖬲𖬞 𖬎𖬰𖬩𖬵 𖬒𖬲𖬯𖬵 𖬉 𖬅𖬮𖬰 𖬙 𖬂𖬰𖬧𖬵.

𞄔𞄄𞄧𞄤𞄃𞄧𞄴𞄅𞄫𞄵𞄘𞄧𞄵𞄉𞄨𞄴 𞄀𞄧𞄲𞄤𞄎𞄪𞄳𞄘𞄬𞄲𞄚𞄄𞄲𞄫𞄃𞄄𞄦𞄰𞄤 𞄊𞄦𞄰𞄜𞄤𞄵𞄨𞄋𞄨𞄴 𞄄𞄤𞄳𞄨𞄔𞄨𞄲𞄈𞄤𞄦. 𞄉𞄤𞄳𞄬𞄆𞄤𞄲 𞄑𞄨𞄵𞄉𞄧𞄰𞄉𞄤𞄲𞄃𞄄𞄤𞄲𞄬 𞄃𞄄𞄦𞄰𞄤𞄉𞄧𞄰𞄊𞄦𞄰𞄤𞄃𞄄𞄦𞄰𞄤 𞄦𞄰𞄉𞄫𞄵𞄘𞄧𞄳𞄤𞄁𞄧𞄱𞄈𞄨𞄲 𞄧𞄤 𞄎𞄪𞄂𞄤𞄱𞄬𞄦𞄰𞄉𞄫𞄵𞄂𞄤𞄱𞄬𞄔𞄨𞄲𞄎𞄪𞄧𞄳 𞄧𞄤𞄎𞄬𞄳𞄃𞄦𞄲.

Txhua tus neeg yug los muaj kev ywj pheej thiab sib npaug zos hauv txoj cai. Lawv xaj nrog lub laj thawj thiab lub siab thiab ib leeg yuav tsum coj ua ke ntawm ib leeg ntawm txoj kev ua kwv tij.

Vietnamese Hmong:[50]

Cxuô tus nênhl zul los muôx cêr zưx fênhx thiêz siz npâul jôs hâur txox chai. Lơưr xax ndol luz lax thơưx thiêz luz siêz thiêz iz lênhl zuôr tsuv chox uô cê ntơưv iz lênhl ntơưv txôx cêr uô cưr tiz.

tsʰuə˧ tu˩ neŋ˧˩̤ ʝu˧˩̤ lɒ˩ muə˥˧ ke˧˧˦ ʝɨ˥˧ pʰeŋ˥˧ tʰiə˦ ʂi˦ ᵐbau˧˩̤ ʐɒ˩ hau˧˦ tsɒ˥˧ cai˧. Laɨ˧˦ sa˥˧ ᶯɖɒ˧˩̤ lu˦ la˥˧ tʰaɨ˥˧ tʰiə˦ lu˦ ʂiə˦ tʰiə˦ i˦ leŋ˧˩̤ ʝuə˧˦ tʂu˩̰ cɒ˥˧ uə˧ ke˧ ⁿdaɨ˩̰ i˦ leŋ˧˩̤ ⁿdaɨ˩̰ tsɒ˥˧ ke˧˧˦ uə˧ kɨ˧˦ ti˥˧.

English:[51]

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Sample text in Hmong RPA, Pahawh Hmong, and Hmong IPA:[52][53][54]

Hmong RPA:

Hmoob yog ib nywj keeb neeg uas yeej nrog ntiaj teb neeg tib txhij tshwm sim los. Niaj hnoob tam sim no tseem muaj nyob thoob plaws hauv ntiaj teb, xws: es xias, yus lauv, auv tas lias, thiab as mes lis kas. Hom neeg Hmoob no yog thooj li cov neeg nyob sab es xias. Tab sis nws muaj nws puav pheej teej tug, moj kuab, txuj ci, mooj kav moj coj, thiab txheeb meem mooj meej kheej ib yam nkaus li lwm haiv neeg. Hmoob yog ib hom neeg uas nyiam txoj kev ncaj ncees, nyiam kev ywj pheej, nyiam phooj ywg, muaj kev cam hwm, muaj txoj kev sib hlub, sib pab thiab sib tshua heev.

Pahawh Hmong:

𖬌𖬣𖬵 𖬓𖬤 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬘𖬲𖬮𖬵 𖬀𖬶 𖬁𖬲𖬬 𖬑𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬀𖬰𖬤 𖬓𖬜𖬰 𖬔𖬶𖬩𖬵 𖬈𖬰𖬧𖬵 𖬁𖬲𖬬 𖬂𖬲𖬧𖬵 𖬂𖬰𖬦𖬰 𖬘𖬪𖬰 𖬂𖬤𖬵 𖬓𖬲𖬞. 𖬔𖬶𖬬 𖬌𖬩 𖬖𖬧𖬵 𖬂𖬤𖬵 𖬓𖬰𖬬 𖬓𖬲𖬞 𖬀𖬝𖬰 𖬐𖬰𖬦 𖬒𖬰𖬮𖬵 𖬌𖬟𖬰 𖬏𖬰𖬟𖬵 𖬄𖬲𖬟 𖬔𖬶𖬩𖬵 𖬈𖬰𖬧𖬵, 𖬙𖬲𖬮 𖬃𖬞: 𖬉𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬕𖬰𖬮, 𖬇𖬰𖬤 𖬄𖬲𖬞, 𖬄𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬗𖬲𖬧𖬵 𖬕𖬰𖬞, 𖬔𖬟𖬰 𖬗𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬉𖬲𖬦 𖬃𖬰𖬞 𖬗𖬲. 𖬒𖬟 𖬁𖬲𖬬 𖬌𖬣𖬵 𖬓𖬰𖬬 𖬓𖬤 𖬌𖬲𖬟𖬰 𖬃𖬞 𖬒𖬶𖬯 𖬁𖬲𖬬 𖬒𖬰𖬮𖬵 𖬖𖬲𖬤𖬵 𖬉𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬕𖬰𖬮. 𖬖𖬲𖬧𖬵 𖬃𖬰𖬤𖬵 𖬙𖬲𖬬 𖬐𖬰𖬦 𖬙𖬲𖬬 𖬐𖬲𖬪𖬵 𖬀𖬰𖬝𖬵 𖬀𖬰𖬧𖬵 𖬇𖬲𖬧𖬵, 𖬒𖬲𖬦 𖬐𖬶, 𖬆𖬶𖬯𖬵 𖬃𖬯, 𖬌𖬲𖬦 𖬗 𖬒𖬲𖬦 𖬒𖬲𖬯, 𖬔𖬟𖬰 𖬀𖬶𖬦𖬰 𖬀𖬦 𖬌𖬲𖬦 𖬀𖬰𖬦 𖬀𖬰𖬩𖬰 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬖𖬤 𖬅𖬰𖬢 𖬃𖬞 𖬘𖬞 𖬊𖬲𖬟 𖬁𖬲𖬬. 𖬌𖬣𖬵 𖬓𖬤 𖬂𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬒𖬟 𖬁𖬲𖬬 𖬑𖬲𖬮𖬰 𖬔𖬰𖬮𖬵 𖬒𖬲𖬯𖬵 𖬉 𖬖𖬰𖬤𖬰 𖬁𖬰𖬤𖬰, 𖬔𖬰𖬮𖬵 𖬉 𖬘𖬲𖬤 𖬀𖬰𖬝𖬵, 𖬔𖬰𖬮𖬵 𖬌𖬲𖬝𖬵 𖬙𖬶𖬤, 𖬐𖬰𖬦 𖬉 𖬖𖬯 𖬘𖬟, 𖬐𖬰𖬦 𖬒𖬲𖬯𖬵 𖬉 𖬂𖬲𖬤𖬵 𖬆𖬰𖬥, 𖬂𖬲𖬤𖬵 𖬖𖬲𖬪𖬵 𖬔𖬟𖬰 𖬂𖬲𖬤𖬵 𖬑𖬪𖬰 𖬀𖬲𖬟.

Hmong IPA:

mɒŋ˦ ʝɒ˧˩̤ i˦ ɲɨ˥˧ keŋ˦ neŋ˧˩̤ uə˩ ʝeŋ˥˧ ᶯɖɒ˧˩̤ ⁿdiə˥˧ te˦ neŋ˧˩̤ ti˦ tsʰi˥˧ tʂʰɨ˩̰ ʂi˩̰ lɒ˩. Niə˥˧ n̥ɒŋ˦ ta˩̰ ʂi˩̰ nɒ˧ tʂeŋ˩̰ muə˥˧ ɲɒ˦ tʰɒŋ˦ pˡaɨ˩ hau˧˦ ⁿdiə˥˧ te˦, sɨ˩: e˩ siə˩, ʝu˩ lau˧˦, au˧˦ ta˩ li˧ə˩, tʰiə˦ a˩ me˩ li˧˩ ka˩. Hɒ˩̰ neŋ˧˩̤ M̥ɒŋ˦ nɒ˧ ʝɒ˧˩̤ tʰɒŋ˥˧ li˧ cɒ˧˦ neŋ˧˩̤ ɲɒ˦ ʂa˦ e˩ siə˩. Ta˦ ʂi˩ nɨ˩ muə˥˧ nɨ˩ puə˧˦ pʰeŋ˥˧ teŋ˥˧ tu˧˩̤, mɒ˥˧ kuə˦, tsu˥˧ ci˧, mɒŋ˥˧ ka˧˦ mɒ˥˧ cɒ˥˧, tʰiə˦ tsʰeŋ˦ meŋ˩̰ mɒŋ˥˧ meŋ˥˧ kʰeŋ˥˧ i˦ ʝa˩̰ ᵑɡau˩ li˧ lɨ˩̰ hai˧˦ neŋ˧˩̤. M̥ɒŋ˦ ʝɒ˧˩̤ i˦ Hɒ˩̰ neŋ˧˩̤ uə˩ ɲiə˩̰ tsɒ˥˧ ke˧˦ ᶮɟa˥˧ ᶮɟeŋ˩, ɲiə˩̰ ke˧˦ ʝɨ˥˧ pʰeŋ˥˧, ɲiə˩̰ pʰɒŋ˥˧ ʝɨ˧˩̤, muə˥˧ ke˧˦ ca˩̰ hɨ˩̰, muə˥˧ tsɒ˥˧ ke˧˦ ʂi˦ l̥u˦, ʂi˦ pa˦ tʰiə˦ ʂi˦ tʂʰuə˧ heŋ˧˦.

In popular culture

[edit]The 2008 film Gran Torino by Clint Eastwood features a large American Hmong speaking cast.[55][56] The screenplay was written in English and the actors improvised the Hmong parts of the script. The decision to cast Hmong actors received a positive reception in Hmong communities.[57] The film also gained recognition and collected awards such as the Ten Best Films of 2008 from the American Film Institute and a César Award in France for Best Foreign Film.[58][59]

Films

[edit]The following films feature the Hmong language:

- 2008 – "Gran Torino". Directed by Clint Eastwood; produced by Clint Eastwood, Bill Gerber, Robert Lorenz. The story follows Walt Kowalski, a recently widowed Korean War veteran alienated from his family and angry at the world. Walt's young neighbor, Thao Vang Lor, is pressured by his cousin into trying to steal Walt's prized 1972 Ford Torino for his initiation into a gang. Walt thwarts the theft and subsequently develops a relationship with the boy and his family.

- 2011 – "Bittersweet Tears (Kua Muag Iab)". Directors by Kelly Vang & Mandy Xiong; Writer: Kelly Vang. Bittersweet Tears is a romantic comedy about a vengeful and bittersweet love between Gaomao (Jenny Lor) and Vong (Beng Hang). Vong is the only son of Chong Yee (Billy Yang). Having lost everything Gaomao swears vengeance on Chong Yee, the man whom she claims to be responsible for her loss. Will Gaomao be able to overcome her own heart and take her revenge?

- 2016 – "1985". Director and writer by Kang Vang. When an adventurous Hmong teen discovers a secret map to a mythical dragon, he and his three best friends decide to go on a quest that leads them on a journey filled with danger, excitement, and self-discovery.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]a Ethnologue uses the term "Hmong" as a "macrolanguage", i.e., along the lines of the Chinese 苗语 Miáoyǔ "Miao language", to handle the fact that some mainland Chinese academic sources lump many individual languages together into single "language" categories, while international sources almost universally keep these languages distinct.[60][61] As the current article is focused on the Hmong language proper as found in international published sources, the population figure here reflects this. Ethnologue (17th edition) lists the population of the larger macrolanguage at 8.1 million.

References

[edit]- ^ Jarkey 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Ratliff, Martha (1992). Meaningful Tone: A Study of Tonal Morphology in Compounds, Form Classes, and Expressive Phrases in White Hmong. Dekalb, Illinois: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University.

- ^ Jarkey, Nerida (2015). Serial Verbs in White Hmong. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29239-0.

- ^ Hoeffel, Elizabeth M.; Rastogi, Sonya; Kim, Myoung Ouk; Shahid, Hasan (March 2012). "The Asian Population: 2010" (PDF). 2010 Census Briefs. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Not of Chinese Miao as a whole for which the standard language is based on Hmu

- ^ "2007-188 - ISO 639-3". www.sil.org.

- ^ a b c d "Chapter 2. Overview of Lao Hmong Culture." (Archive) Promoting Cultural Sensitivity: Hmong Guide. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. p. 14. Retrieved on 5 May 2013.

- ^ Note however that "Black Miao" is more commonly used for Hmu.

- ^ "ISO 639-3 New Code Request" (PDF). Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ Golston, Chris; Phong Yang (2001). "Hmong loanword phonology". In C. Féry; A. D. Green; R. van de Vijver (eds.). Proceedings of HILP 5 (Linguistics in Potsdam 12 ed.). Potsdam: University of Potsdam. pp. 40–57. ISBN 3-935024-27-4. [1]

- ^ Smalley, William et al. Mother of Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990. p. 48-51. See also: Mortensen, David. “Preliminaries to Mong Leng (Mong Njua) Phonology” Unpublished, UC Berkeley. 2004. Archived 29 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 王辅世主编,《苗语简志》,民族出版社,1985年。

- ^ "Hmong Dictionary - Dictionary Hmong".

- ^ White 2020, p. 216.

- ^ Even the landmark book The Sounds of the World's Languages specifically describes lateral release as involving a homorganic consonant.

- ^ White 2020, p. 220.

- ^ White 2020, p. 214.

- ^ Examples taken from: Heimbach, Ernest H. White Hmong–English Dictionary [White Meo-English Dictionary]. 2003 ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications, 1969. Note that many of these words have multiple meanings.

- ^ Robson, David. "The beautiful languages of the people who talk like birds". BBC Future. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Fadiman, Anne (1998). The spirit catches you and you fall down: a Hmong child, her American doctors, and the collision of two cultures. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-374-52564-4.

- ^ Smith, Natalie Jill. "Ethnicity, Reciprocity, Reputation and Punishment: An Ethnoexperimental Study of Cooperation among the Chaldeans and Hmong of Detroit (Michigan)" (PhD dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles, 2001. p. 225. UMI Number: 3024065. Cites: Hamilton-Merritt, 1993 and Faderman [sic], 1998

- ^ Everson, Michael (15 February 2017). "L2/17-002R3: Proposal to encode the Nyiakeng Puachue Hmong script in the UCS" (PDF).

- ^ http://www.hmonglanguage.net Hmong Language online encyclopedia.

- ^ Mortensen (2004)

- ^ Ratliff, Martha (1997). "Hmong–Mien demonstratives and pattern persistence" (PDF). Mon-Khmer Studies. 27: 317–328. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2007. ()

- ^ Enfield 2018, p. 17.

- ^ Mortensen 2019, pp. 624–625.

- ^ Bisang 1993, pp. 22–26.

- ^ Simpson, Soh & Nomoto 2011, p. 175.

- ^ Mortensen 2019, pp. 625–626.

- ^ Mortensen 2019, pp. 622–624.

- ^ a b Bisang 1993, p. 27.

- ^ Mortensen 2019, p. 623.

- ^ Matthews 2007, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Strecker, David and Lopao Vang. White Hmong Grammar. 1986.

- ^ Mottin 1978.

- ^ Jaisser 1984.

- ^ White 2014, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Ratliff 2010, p. 242.

- ^ White 2021, p. 164.

- ^ Ratliff 2010, p. 243.

- ^ White 2021, p. 166.

- ^ "WOLD -". wold.clld.org. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ White 2021, p. 167.

- ^ "Hmong and Hmong Americans in Minnesota". MNopedia. 2 July 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "Hmong". College of Liberal Arts. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "Microsoft Translator celebrates International Mother Language Day with the release of Hmong". Microsoft Translator Blog. 21 February 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ Donald Melanson (8 May 2013). "Google Translate adds five more languages to its repertoire". Engadget. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Lor, Maichou (30 April 2020). Sha, Mandy (ed.). Hmong and Chinese Qualitative Research Interview Questions: Assumptions and Implications of Applying the Survey Back Translation Method (Chapter 9) in The Essential Role of Language in Survey Research. RTI Press. pp. 181–202. doi:10.3768/rtipress.bk.0023.2004. ISBN 978-1-934831-24-3.

- ^ a b c d "UDHR in Hmong-Mien languages". www.omniglot.com. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". United Nations. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Pahawh Hmong alphabet and pronunciation". omniglot.com. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Oppitz, Michael. "Die geschichte der verlorenen schrift" (PDF). Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "세계의 문자들". podor.egloos.com (in Korean). Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Gran Torino movie review and film summary (2008) | Roger Ebert". Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "Hmong get a mixed debut in new Eastwood film". MPR News. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ O'Brien, Kathleen. "Rutgers scholar sheds light on 'Gran Torino' ethnic stars Archived 17 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine." The Star-Ledger. Thursday 15 January 2009. Retrieved on 16 March 2012.

- ^ "Prison drama A Prophet sweeps French Oscars". BBC News. 1 March 2010. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2008". afi.com. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ^ "Hmong". Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ Strecker, David (1987). "The Hmong-Mien Languages" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 10:2: 1–11. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bisang, Walter (1993). "Classifiers, Quantifiers and Class Nouns in Hmong". Studies in Language. 17 (1). John Benjamins Publishing Company: 1–51. doi:10.1075/sl.17.1.02bis. ISSN 0378-4177.

- Cooper, Robert, ed. (1998). The Hmong: A Guide to Traditional Lifestyles. Singapore: Times Editions. pp. 35–41.

- Enfield, N. J. (2018). Mainland Southeast Asian Languages: A Concise Typological Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781139019552. ISBN 9781139019552. S2CID 133621227.

- Finck, John (1982). "Clan Leadership in the Hmong Community of Providence, Rhode Island". In Downing, Bruce T.; Olney, Douglas P. (eds.). The Hmong in the West. Minneapolis, MN: Southeast Asian Refugee Studies Project, Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, University of Minnesota. pp. 22–25.

- Jaisser, Annie (1984). Complementation in Hmong (MA thesis). San Diego State University.

- Matthews, Stephen (2007). "Cantonese Grammar in Areal Perspective". In Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y.; Dixon, R. M. W. (eds.). Grammars in Contact: A Cross-Linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 220–236. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199207831.003.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-920783-1.

- Mortensen, David (2019). "Hmong (Mong Leng)". In Vittrant, Alice; Watkins, Justin (eds.). The Mainland Southeast Asia Linguistic Area. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 609–652. doi:10.1515/9783110401981-014. ISBN 978-3-11-040198-1. S2CID 195399573.

- Mottin, Jean (1978). Éléments de grammaire Hmong Blanc. Bangkok: Don Bosco Press.

- Ratliff, Martha (2010). Hmong-Mien Language History. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Simpson, Andrew; Soh, Hooi Ling; Nomoto, Hiroki (2011). "Bare Classifiers and Definiteness: A Cross-linguistic Investigation". Studies in Language. 35 (1). John Benjamins Publishing Company: 168–193.

- Thao, Paoze (1999). Mong Education at the Crossroads. New York: University Press of America. pp. 12–13.

- White, Nathan (2014). Non-spatial Setting in White Hmong (MA thesis). Trinity Western University.

- White, Nathan (2020). "Word in Hmong". In Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y.; Dixon, R. M. W.; White, Nathan (eds.). Phonological Word and Grammatical Word: A Cross-linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 213–259.

- White, Nathan (2021). "Language and variety mixing in diasporic Hmong". Italian Journal of Linguistics. 33 (1): 157–180. doi:10.26346/1120-2726-172.

- Xiong, Yuyou; Cohen, Diana (2005). Student's Practical Miao–Chinese–English Handbook / Npout Ndeud Xof Geuf Lol Hmongb Lol Shuad Lol Yenb. Yunnan Nationalities Publishing House. p. 539. ISBN 7-5367-3287-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Enwall, Joakim. Hmong Writing Systems in Vietnam: A Case Study of Vietnam's Minority Language Policy. Stockholm, Sweden: Center for Pacific Asian Studies, 1995.

- Lyman, Thomas Amis (Chulalongkorn University). "The Mong (Leeg Miao) and their Language: A Brief Compendium" (Archive). p. 63–66.

- Miyake, Marc. 2011. Unicode 6.1: the Old Miao script.

- Miyake, Marc. 2012. Anglo-Hmong tonology.

External links

[edit]- White Hmong Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database)

- White Hmong Swadesh List on Wiktionary (see Swadesh list)

- Lomation's Hmong Text Reader – free online program that can read Hmong words/text.

- Online Hmong dictionary (including audio clips)

- Mong Literacy: consonants, vowels, tones of Mong Njua and Hmong Daw

- Hmong Resources

- Hmong basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Hmong text reader

- 1. CVT — Romanized Popular Alphabet 0.0.1 documentation Romanized Popular Alphabet

- English-Hmong Phrasebook with Useful Wordlist (for Hmong Speakers), Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, DC.

Hmong language

View on GrokipediaClassification and history

Linguistic affiliation

The Hmong language is classified within the West Hmongic branch of the Hmongic languages, which forms one of the two primary divisions of the Hmong-Mien (also known as Miao-Yao) language family.[7] This family comprises a compact group of minority languages spoken mainly in southern China and mainland Southeast Asia, with Hmong-Mien languages exhibiting significant internal diversity. Conservative estimates indicate approximately 4 to 5 million speakers of mutually intelligible Hmong varieties worldwide.[8] Typologically, Hmong is an analytic language characterized by isolating morphology, with little to no inflection or derivation through affixes. It follows a predominantly subject-verb-object (SVO) word order and is head-initial in most constructions, though genitive and relative clause structures show variability. A defining feature is its heavy reliance on tone to distinguish lexical meanings, often featuring more tones than neighboring languages in the region.[7] Within the Hmong-Mien family, Hmong relates closely to the Mienic branch, which includes languages like Iu Mien, though the two branches display mutual affinities but are not fully intelligible. Hmong varieties themselves form a dialect continuum, where adjacent forms are mutually intelligible, but distant ones may not be, reflecting gradual linguistic divergence rather than sharp boundaries between separate languages.[7] Hypotheses on broader genetic affiliations for the Hmong-Mien family remain debated, with proposals linking it to Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic (including Mon-Khmer), or other regional families like Tai-Kadai and Austronesian, but these lack consensus and are not widely accepted.[7]Historical development

The Hmong language, part of the Hmong-Mien family, traces its origins to southern China, where ancestral populations related to modern Hmong speakers emerged as a distinct linguistic group, with genetic evidence indicating a presence in the region dating back approximately 2,500 years.[9] This early development occurred amid interactions with neighboring groups, including Tai-Kadai and Austroasiatic speakers, shaping the language's foundational features before significant disruptions.[10] Beginning in the 18th century, escalating conflicts with the Qing dynasty, including persecutions and land encroachments, prompted large-scale southward migrations of Hmong communities into the mountainous regions of what are now Laos, Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar.[11] These movements, driven by resistance to assimilation and resource scarcity, fragmented Hmong-speaking populations and reinforced the language's role as a marker of ethnic identity during periods of upheaval. Hmong oral traditions recount the existence of an ancient writing system that was lost during Chinese imperial efforts to standardize scripts and assimilate non-Han groups.[12] This folklore, preserved through generations of storytelling, describes the script's destruction as a deliberate act to erase Hmong cultural autonomy, leading to a reliance on oral transmission for history, genealogy, and knowledge— a tradition that dominated for over two millennia.[13] The absence of a written form until the modern era amplified the language's vulnerability to external influences but also fostered resilient mnemonic practices, such as epic songs and proverbs, that encoded complex social and cosmological concepts.[14] Under French colonial rule in Indochina, particularly in Laos during the mid-20th century, missionaries introduced the first widely adopted orthography for Hmong to facilitate Bible translation and literacy among highland communities.[15] In 1953, American linguists William Smalley and Linwood Barney, collaborating with French Catholic missionary Father Yves Bertrais, developed the Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA), a Latin-based script adapted to Hmong's tonal phonology, which gained traction in missionary schools and refugee contexts.[16] This system marked a pivotal shift from oral dominance, enabling documentation of folklore and basic education, though it reflected colonial priorities in language standardization. The 1975 communist takeover in Laos triggered a massive Hmong exodus, with over 100,000 refugees resettling in the United States, France, and other countries, creating a global diaspora that intensified pressures on language maintenance.[17] In host societies, assimilation demands—such as English-only education and intergenerational language shift—have accelerated Hmong's decline among younger generations, with studies showing reduced fluency in diaspora communities due to socioeconomic barriers and cultural adaptation.[18] Preservation efforts, including community language programs and digital media, have emerged to counter these trends, emphasizing RPA literacy to sustain oral traditions amid ongoing identity challenges.[19]Varieties and distribution

Major varieties

The Hmong language encompasses a dialect continuum within the West Hmongic branch of the Hmong-Mien family, with principal varieties including Hmong Daw (also known as White Hmong), Mong Leng (also known as Green or Blue Hmong), and the Chuanqiandian Miao cluster (including the Dananshan dialect, the basis of the Chinese standard). Hmong Daw and Mong Leng are the most prominent dialects among Hmong communities in Southeast Asia and the diaspora, characterized by high mutual intelligibility due to shared grammar and core vocabulary, though they exhibit differences in pronunciation, lexical items (with approximately 70% overlap in basic vocabulary), and some phonological features such as tone realization. For instance, speakers of Hmong Daw and Mong Leng can generally understand each other with minimal adjustment, akin to related dialects in other language families. The Chuanqiandian varieties, spoken mainly in China, represent another closely related subgroup within West Hmongic. Hmu, classified under Eastern Hmongic, is a more divergent Hmongic language spoken mainly in Guizhou Province, China, and features distinct phonological inventories that reduce intelligibility with Western varieties like Hmong Daw.[7][20][21][22] In Vietnam, Hmong varieties form poorly documented subgroups, often referred to with the prefix "Hmôngz" in local orthographies, including Hmôngz Lenhl (White Hmong), Hmôngz Dơuz (White subgroup), Hmôngz Duz (Black Hmong), Hmôngz Siz (Red Hmong), and Hmôngz Sua (Green Hmong). These exhibit unique phonological shifts, such as variations in initial consonants and vowel systems adapted to regional substrates, which complicate standardization efforts. Script adoption remains challenging, with the Hmong Vietnamese Romanized script—featuring 59 consonants, 28 rhymes, and 8 tones—struggling due to its complexity and limited applicability across dialects, as evidenced by field research showing low usage rates compared to the more accessible International Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA). Only about 20% of Hmong in Vietnam actively use local scripts, hindered by dialectal diversity and lack of institutional support.[23] The Chinese standard variety, based on the Dananshan dialect of Western Miao (Hmong), differs from Southeast Asian forms like Hmong Daw and Mong Leng through tone mergers and splits, resulting in an 8-tone system versus the typical 7 tones in the latter. For example, certain low-level and falling tones have merged in some Chinese varieties, altering phonetic contrasts that are preserved in Southeast Asian Hmong. These divergences stem from geographic isolation across mountainous regions, which limited contact and fostered independent developments, as well as substrate influences from neighboring Sino-Tibetan and Austroasiatic languages that introduced lexical borrowings and phonetic adaptations.[24][25][7]Geographic distribution

The Hmong language is spoken by an estimated 3.7 million native speakers worldwide, primarily in East and Southeast Asia. In China, approximately 1.4 million speakers of major Hmong varieties, such as the Chuanqiandian Miao cluster (including the Dananshan dialect), reside in the southern provinces of Guizhou, Yunnan, Hunan, and Sichuan, where they use these West Hmongic lects in rural highland communities.[26] Vietnam hosts approximately 1.2 million Hmong speakers concentrated in the northern mountainous provinces such as Lào Cai, Hà Giang, and Sơn La.[27] In Laos, the speaker base has declined from around 400,000 prior to 1975 to about 300,000 today, largely due to conflict-related displacement and emigration, with communities remaining in the northern provinces like Xieng Khouang and Luang Prabang.[25] Thailand is home to over 100,000 speakers, mostly in the northern hill regions near the borders with Laos and Myanmar.[28] Myanmar has a smaller presence, with fewer than 20,000 speakers in isolated highland areas along the eastern border.[29] Significant diaspora communities have formed following the Vietnam War and subsequent refugee movements, contributing to the global spread of the language. The United States has the largest expatriate population, with about 360,000 individuals of Hmong descent as of 2023, many maintaining the language as a heritage tongue; these communities are densely concentrated in California (especially Fresno and Sacramento), Minnesota (Saint Paul area), and Wisconsin (Wausau and La Crosse).[30] France hosts over 15,000 Hmong residents, primarily in urban centers like Paris and Rhône-Alpes, stemming from direct resettlement from Laos.[31] Smaller groups exist in Australia (around 2,000 speakers, mainly in Melbourne and Sydney) and Canada (approximately 4,000, focused in Ontario and British Columbia).[31] Overall, the total number of speakers of mutually intelligible Hmong varieties is estimated at approximately 4 million worldwide, including diaspora populations. Urbanization trends are reshaping Hmong language use, particularly in Vietnam and the United States, where migration to cities for economic opportunities has accelerated language shift toward dominant languages like Vietnamese and English among younger generations. In Vietnam, rural-to-urban movement has led to decreased daily use of Hmong in favor of Vietnamese, especially in expanding highland towns.[32] In the U.S., 71% of Hmong Americans aged 5 and older speak English proficiently, reflecting intergenerational transmission challenges in urban settings, though family and community networks sustain the language.[30] As of 2025, U.S. Hmong communities continue to expand, with notable growth in bilingual education initiatives to preserve the language amid diaspora vitality. Programs such as dual-language immersion schools in Fresno Unified School District and the Hmong American Immersion School in Appleton, Wisconsin, integrate Hmong instruction into curricula, supporting over 1,000 students annually and fostering biliteracy.[33][34][35]Phonology

Consonants

The Hmong language exhibits a rich consonant inventory, particularly in the Hmong Daw (White Hmong) variety, which includes approximately 48 to 55 phonemic consonants depending on whether certain complex initials are analyzed as clusters or unitary phonemes.[1] These consonants occur exclusively in syllable-initial position and encompass a range of manners of articulation, including stops, nasals, fricatives, affricates, and approximants, with distinctions in voicing, aspiration, prenasalization, and release types.[36] Stops form the largest category, featuring plain voiceless (e.g., /p/, /t/, /k/), aspirated voiceless (e.g., /pʰ/, /tʰ/, /kʰ/), voiced (e.g., /b/, /d/, /g/), and prenasalized forms (e.g., /ᵐb/, /ⁿd/, /ᵑɡ/), alongside lateral- and strident-released variants such as /pˡ/ and /tˢ/.[36] Nasals include both voiced (e.g., /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /ɲ/) and voiceless counterparts (e.g., /m̥/, /n̥/, /ŋ̥/, /ɲ̥/), the latter often realized with aspiration in orthography as "hm," "hn," etc. Fricatives comprise labiodental (/f/, /v/), alveolar (/s/), postalveolar (/ʂ/), and lateral (/ɬ/), with voiced variants like /v/ showing allophonic variation between , [β], and depending on adjacent vowels or position. Affricates, such as /ts/, /tsʰ/, /ʈʂ/, and prenasalized /ⁿts/, add to the inventory's complexity, while approximants include /j/, /w/, /l/, and /ɥ/.[1][36] The following table presents a representative pulmonic consonant chart for Hmong Daw, organized by place and manner of articulation, with IPA symbols and corresponding Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA) orthographic examples where applicable (e.g., /ɲ/ as "ny" in "nyab" 'to bend'):| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental/Alveolar | Postalveolar/Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p (p) | t (t) | ʈ (tr) | k (k) | q (q) | |||

| pʰ (ph) | tʰ (th) | ʈʰ (thr) | kʰ (kh) | qʰ (qh) | ||||

| pˡ (pl) | kˡ (kl) | |||||||

| b (b) | d (d) | g (g) | ||||||

| ᵐb (mb) | ⁿd (nd) | ᵑɡ (ng) | ||||||

| tl (tl) | ||||||||

| Affricate | ts (ts) | ʈʂ (ch) | ||||||

| tsʰ (tsh) | ʈʂʰ (chh) | |||||||

| ⁿts (ntx) | ⁿɖʐ (nzh) | |||||||

| Fricative | f (f), v (v) | s (s) | ʂ (x) | ç (xy) | h (h) | |||

| ɬ (hl) | ||||||||

| Nasal | m (m), m̥ (hm) | n (n), n̥ (hn) | ɲ (ny), ɲ̥ (hny) | ŋ (ng), ŋ̥ (hng) | ||||

| Approximant | l (l) | j (y) | ||||||

| w (vw) | ɥ (w) |

Vowels

The Hmong languages exhibit a moderately sized vowel inventory, typically comprising 6 oral monophthongs and a smaller set of diphthongs, with variations across dialects such as Hmong Daw (White Hmong) and Mong Leng (Green Hmong).[38][1] In Hmong Daw, the oral monophthongs are /i/ (high front unrounded), /e/ (mid front unrounded), /a/ (low central unrounded), /ɔ/ (mid back unrounded), /u/ (high back rounded), and /ɨ/ (high central unrounded), providing contrasts in height, frontness, and rounding.[38] These vowels are generally steady-state, with /ɨ/ serving as a distinctive central vowel absent in many related languages.[38] In Mong Leng, the oral monophthong inventory includes /i/ (high front unrounded), /ɪ/ (near-high front unrounded, contrasting with /i/ in height), /e/ (realized as [ɛ], mid-low front unrounded), /a/ (low central unrounded), /ɔ/ (mid back unrounded), and /u/ (high back rounded), showing a slight shift toward more open front vowels compared to Hmong Daw's /e/.[1] Both varieties feature nasalized monophthongs, though their distribution differs: Hmong Daw has /ẽ/ (mid front nasalized) and /õ/ (mid back nasalized, often with optional velar nasal coda [ŋ]), while Mong Leng includes these plus /ã/ (low central nasalized), which merges with /a/ in Hmong Daw.[38][1] Nasal vowels are longer and more centralized than their oral counterparts, with nasalization extending throughout the vowel duration.[38] Diphthongs in Hmong are primarily falling or rising combinations involving a low or mid vowel, common across varieties for lexical contrast. In Hmong Daw, the diphthongs are /ai/ (centralizing to [ae]), /au/ (backing to [ɔu] or lengthening [ɔː]), /aɨ/ (central [ɐə]), /ia/ (rising [ĭa] or [eə]), and /ua/ (rising [uə] or [oɔ]).[38] Mong Leng features /aɪ/ (similar to Hmong Daw's /ai/), /aʊ/ and /aʊ̯/ (falling back diphthongs), and /u̯a/ (rising, with minimal fronting, sometimes [wa]), but lacks the /ia/ diphthong found in Hmong Daw, often replacing it with a monophthong /a/.[1] These diphthongs exhibit asymmetric trajectories, with the first element shorter in rising types.[38] In the Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA), the standard orthography for Hmong, vowels are represented with Latin letters approximating their qualities: "a" for /a/, "e" for /e/ or [ɛ], "i" for /i/, "o" for /ɔ/, "u" for /u/, and "w" or "v" for /ɨ/ or /ɪ/.[38][1] Diphthongs follow straightforward digraphs like "ai" for /ai/, "au" for /au/, "aiv" for /aɨ/, "ia" for /ia/, and "ua" for /ua/, while nasalized vowels use doubled forms or endings such as "en" for /ẽ/, "on" for /õ/, and "aa" for /ã/ in Mong Leng.[38][1] This system ensures one-to-one correspondences for most vowels, facilitating literacy across dialects despite minor phonological differences.[1]Tones