Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

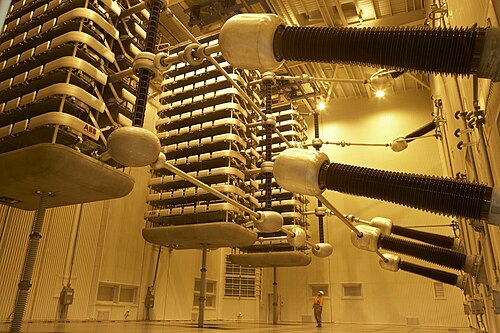

High-voltage direct current

View on Wikipedia

A high-voltage direct current (HVDC) electric power transmission system uses direct current (DC) for electric power transmission, in contrast with the more common alternating current (AC) transmission systems.[1] Most HVDC links use voltages between 100 kV and 800 kV.

HVDC lines are commonly used for long-distance power transmission, since they require fewer conductors and incur less power loss than equivalent AC lines. HVDC also allows power transmission between AC transmission systems that are not synchronized. Since the power flow through an HVDC link can be controlled independently of the phase angle between source and load, it can stabilize a network against disturbances due to rapid changes in power. HVDC also allows the transfer of power between grid systems running at different frequencies, such as 50 and 60 Hz. This improves the stability and economy of each grid, by allowing the exchange of power between previously incompatible networks.

The modern form of HVDC transmission uses technology developed extensively in the 1930s in Sweden (ASEA) and in Germany. Early commercial installations included one in the Soviet Union in 1951 between Moscow and Kashira, and a 100 kV, 20 MW system between Gotland and mainland Sweden in 1954.[2] The longest HVDC link in the world is the Zhundong–South Anhui link in China a ±1,100 kV, Ultra HVDC line with a length of more than 3,000 km (1,900 mi).[3]

High voltage transmission

[edit]High voltage is used for electric power transmission to reduce the energy lost in the resistance of the wires. For a given quantity of power transmitted, doubling the voltage will deliver the same power at only half the current:

Since the energy lost as heat in the wires is directly proportional to the square of the current using half the current at double the voltage reduces the line losses by a factor of 4.[a] While energy lost in transmission can also be reduced by decreasing the resistance by increasing the conductor size, larger conductors are heavier and more expensive.

High voltage cannot readily be used for lighting or motors, so transmission-level voltages must be reduced for end-use equipment. Transformers are used to change the voltage levels in alternating current (AC) transmission circuits, but cannot pass DC current. Transformers made AC voltage changes practical, and AC generators were more efficient than those using DC. These advantages led to early low-voltage DC transmission systems being supplanted by AC systems around the turn of the 20th century.[4]

Practical conversion of current between AC and DC became possible with the development of power electronics devices such as mercury-arc valves and, starting in the 1970s, power semiconductor devices including thyristors, integrated gate-commutated thyristors (IGCTs), MOS-controlled thyristors (MCTs) and insulated-gate bipolar transistors (IGBT).[5]

History

[edit]Electromechanical systems

[edit]

The first long-distance transmission of electric power was demonstrated using direct current in 1882 in the 57 km Miesbach-Munich Power Transmission, but only 1.5 kW was transmitted.[6] An early method of HVDC transmission was developed by the Swiss engineer René Thury[7] and his method, the Thury system, was put into practice by 1889 in Italy by the Acquedotto De Ferrari-Galliera company. This system used series-connected motor-generator sets to increase the voltage. Each set was insulated from electrical ground and driven by insulated shafts from a prime mover. The transmission line was operated in a constant-current mode, with up to 5,000 volts across each machine, some machines having double commutators to reduce the voltage on each commutator. This system transmitted 630 kW at 14 kV DC over a distance of 120 kilometres (75 mi).[8][9] The Moutiers–Lyon system transmitted 8,600 kW of hydroelectric power a distance of 200 kilometres (120 mi), including 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) of underground cable. This system used eight series-connected generators with dual commutators for a total voltage of 150 kV between the positive and negative poles, and operated from c.1906 until 1936. Fifteen Thury systems were in operation by 1913.[10] Other Thury systems operating at up to 100 kV DC worked into the 1930s, but the rotating machinery required high maintenance and had high energy loss.

Various other electromechanical devices were tested during the first half of the 20th century with little commercial success.[11] One technique attempted for conversion of direct current from a high transmission voltage to lower utilization voltage was to charge series-connected batteries, then reconnect the batteries in parallel to serve distribution loads.[12] While at least two commercial installations were tried around the turn of the 20th century, the technique was not generally useful owing to the limited capacity of batteries, difficulties in switching between series and parallel configurations, and the inherent energy inefficiency of a battery charge/discharge cycle.[b]

Mercury arc valves

[edit]First proposed in 1914,[13] the grid controlled mercury-arc valve became available during the period 1920 to 1940 for the rectifier and inverter functions associated with DC transmission. Starting in 1932, General Electric tested mercury-vapor valves and a 12 kV DC transmission line, which also served to convert 40 Hz generation to serve 60 Hz loads, at Mechanicville, New York. In 1941, a 60 MW, ±200 kV, 115 km (71 mi) buried cable link, known as the Elbe-Project, was designed for the city of Berlin using mercury arc valves but, owing to the collapse of the German government in 1945, the project was never completed.[14] The nominal justification for the project was that, during wartime, a buried cable would be less conspicuous as a bombing target. The equipment was moved to the Soviet Union and was put into service there as the Moscow–Kashira HVDC system.[15] The Moscow–Kashira system and the 1954 connection by Uno Lamm's group at ASEA between the mainland of Sweden and the island of Gotland marked the beginning of the modern era of HVDC transmission.[6]

Mercury arc valves were common in systems designed up to 1972, the last mercury arc HVDC system (the Nelson River Bipole 1 system in Manitoba, Canada) having been put into service in stages between 1972 and 1977.[16] Since then, all mercury arc systems have been either shut down or converted to use solid-state devices. The last HVDC system to use mercury arc valves was the Inter-Island HVDC link between the North and South Islands of New Zealand, which used them on one of its two poles. The mercury arc valves were decommissioned on 1 August 2012, ahead of the commissioning of replacement thyristor converters.

Thyristor valves

[edit]The development of thyristor valves for HVDC began in the late 1960s. The first complete HVDC scheme based on thyristor was the Eel River scheme in Canada, which was built by General Electric and went into service in 1972.[17]

Since 1977, new HVDC systems have used solid-state devices, in most cases thyristors. Like mercury arc valves, thyristors require connection to an external AC circuit in HVDC applications to turn them on and off. HVDC using thyristors is also known as line-commutated converter (LCC) HVDC.

On March 15, 1979, a 1920 MW thyristor based direct current connection between Cabora Bassa and Johannesburg (1,410 km; 880 mi) was energized. The conversion equipment was built in 1974 by Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft AG (AEG), and Brown, Boveri & Cie (BBC) and Siemens were partners in the project. Service interruptions of several years were a result of a civil war in Mozambique.[18] The transmission voltage of ±533 kV was the highest in the world at the time.[6]

Capacitor-commutated converters

[edit]Line-commutated converters have some limitations in their use for HVDC systems. This results from requiring a period of reverse voltage to affect the turn off. An attempt to address these limitations is the capacitor-commutated converter (CCC). The CCC has series capacitors inserted into the AC line connections. CCC has remained only a niche application because of the advent of voltage-source converters (VSCs) which more directly address turn-off issues.

Voltage-source converters

[edit]Widely used in motor drives since the 1980s, voltage-source converters (VSCs) started to appear in HVDC in 1997 with the experimental Hellsjön–Grängesberg project in Sweden. By the end of 2011, this technology had captured a significant proportion of the HVDC market.

The development of higher rated insulated-gate bipolar transistors (IGBTs), gate turn-off thyristors (GTOs), and integrated gate-commutated thyristors (IGCTs), has made HVDC systems more economical and reliable. This is because modern IGBTs incorporate a short-circuit failure mode, wherein should an IGBT fail, it is mechanically shorted. Therefore, modern VSC HVDC converter stations are designed with sufficient redundancy to guarantee operation over their entire service lives. The manufacturer Hitachi Energy (formerly Hitachi ABB Power Grids) calls this concept HVDC Light,[19] while Siemens calls a similar concept HVDC PLUS (Power Link Universal System) and Alstom call their product based upon this technology HVDC MaxSine. They have extended the use of HVDC down to blocks as small as a few tens of megawatts and overhead lines as short as a few dozen kilometers. There are several different variants of VSC technology: most installations built until 2012 use pulse-width modulation in a circuit that is effectively an ultra-high-voltage motor drive. More recent installations, including HVDC PLUS and HVDC MaxSine, are based on variants of a converter called a modular multilevel converter (MMC).

Multilevel converters have the advantage that they allow harmonic filtering equipment to be reduced or eliminated altogether. By way of comparison, AC harmonic filters of typical line-commutated converter stations cover nearly half of the converter station area.

With time, voltage-source converter systems will probably replace all installed simple thyristor-based systems, including the highest DC power transmission applications.[5][page needed]

Comparison with AC

[edit]Advantages

[edit]A long-distance, point-to-point HVDC transmission scheme generally has lower overall investment cost and lower losses than an equivalent AC transmission scheme. Although HVDC conversion equipment at the terminal stations is costly, the total DC transmission-line costs over long distances are lower than for an AC line of the same distance. HVDC requires less conductor per unit distance than an AC line, as there is no need to support three phases and there is no skin effect. AC systems use a higher peak voltage for the same power, increasing insulator costs.

Depending on voltage level and construction details, HVDC transmission losses are quoted at 3.5% per 1,000 km (620 mi), about 50% less than AC (6.7%) lines at the same voltage.[20] This is because direct current transfers only active power and thus causes lower losses than alternating current, which transfers both active and reactive power. In other words, transmitting electric AC power over long distances inevitably results in a phase shift between voltage and current. Because of this phase shift the effective Power=Current*Voltage, where * designates a vector product, decreases. Since DC power has no phase, the phase shift cannot occur in the DC case.

HVDC transmission may also be selected for other technical benefits. HVDC can transfer power between separate AC networks. HVDC power flow between separate AC systems can be automatically controlled to support either network during transient conditions, but without the risk that a major power-system collapse in one network will lead to a collapse in the second. The controllability feature is also useful where control of energy trading is needed.

Specific applications where HVDC transmission technology provides benefits include:

- Undersea-cable transmission schemes (e.g. the 720 km (450 mi) North Sea Link, the 580 km (360 mi) NorNed cable between Norway and the Netherlands,[21] Italy's 420 km (260 mi) SAPEI cable between Sardinia and the mainland,[22] the 290 km (180 mi) Basslink between the Australian mainland and Tasmania, and the 250 km (160 mi) Baltic Cable between Sweden and Germany[23]).

- Endpoint-to-endpoint long-haul bulk power transmission without intermediate taps, usually to connect a remote generating plant to the main grid (e.g. the Nelson River DC Transmission System in Canada).

- Increasing the capacity of an existing transmission line in situations where additional wires are difficult or expensive to install.

- Power transmission and stabilization between unsynchronized AC networks, with the extreme example being an ability to transfer power between countries that use AC at different frequencies.

- Stabilizing a predominantly AC power grid, without increasing prospective short-circuit current.

- Integration of renewable resources such as wind into the main transmission grid. HVDC overhead lines for onshore wind integration projects and HVDC cables for offshore projects have been proposed in North America and Europe for both technical and economic reasons. DC grids with multiple VSCs are one of the technical solutions for pooling offshore wind energy and transmitting it to load centers located far away onshore.[24]

Cable systems

[edit]Long undersea or underground high-voltage cables have a high electrical capacitance compared with overhead transmission lines since the live conductors within the cable are surrounded by a relatively thin layer of insulation (the dielectric), and a metal sheath. The geometry is that of a long coaxial capacitor. The total capacitance increases with the length of the cable. This capacitance is in a parallel circuit with the load. Where alternating current is used for cable transmission, additional current must flow in the cable to charge this cable capacitance. Another way to look at this is to realize, that such capacitance causes a phase shift between voltage and current, and thus decrease of the transmitted power, which is a vector product of voltage and current. Additional energy losses also occur as a result of dielectric losses in the cable insulation. For a sufficiently long AC cable, the entire current-carrying ability of the conductor would be needed to supply the charging current alone. This cable capacitance issue limits the length and power-carrying ability of AC power cables.[25]

However, if direct current is used, the cable capacitance is charged only when the cable is first energized or if the voltage level changes; there is no additional current required. DC powered cables are limited only by their temperature rise and Ohm's law. Although some leakage current flows through the dielectric insulator, this effect is also present in AC systems and is small compared to the cable's rated current.

Overhead line systems

[edit]

The capacitive effect of long underground or undersea cables in AC transmission applications also applies to AC overhead lines, although to a much lesser extent. Nevertheless, for a long AC overhead transmission line, the current flowing just to charge the line capacitance can be significant, and this reduces the capability of the line to carry useful current to the load at the remote end. Another factor that reduces the useful current-carrying ability of AC lines is the skin effect, which causes a nonuniform distribution of current over the cross-sectional area of the conductor. Transmission line conductors operating with direct current suffer from neither constraint. Therefore, for the same conductor losses (or heating effect), a given conductor can carry more power to the load when operating with HVDC than AC.[26]

Finally, depending upon the environmental conditions and the performance of overhead line insulation operating with HVDC, it may be possible for a given transmission line to operate with a constant HVDC voltage that is approximately the same as the peak AC voltage for which it is designed and insulated. The power delivered in an AC system is defined by the root mean square (RMS) of an AC voltage, but RMS is only about 71% of the peak voltage. Therefore, if the HVDC line can operate continuously with an HVDC voltage that is the same as the peak voltage of the AC equivalent line, then for a given current (where HVDC current is the same as the RMS current in the AC line), the power transmission capability when operating with HVDC is approximately 40% higher than the capability when operating with AC.

Asynchronous connections

[edit]

Because HVDC allows power transmission between unsynchronized AC distribution systems, it can help increase system stability, by preventing cascading failures from propagating from one part of a wider power transmission grid to another. Changes in load that would cause portions of an AC network to become unsynchronized and to separate, would not similarly affect a DC link, and the power flow through the DC link would tend to stabilize the AC network. The magnitude and direction of power flow through a DC link can be directly controlled and changed as needed to support the AC networks at either end of the DC link.[27]

Disadvantages

[edit]The disadvantages of HVDC are in conversion, switching, control, availability, and maintenance.

HVDC is less reliable and has lower availability than alternating current (AC) systems, mainly due to the extra conversion equipment. Single-pole systems have availability of about 98.5%, with about a third of the downtime unscheduled due to faults. Fault-tolerant bipole systems provide high availability for 50% of the link capacity, but availability of the full capacity is about 97% to 98%.[28]

The required converter stations are expensive and have limited overload capacity. At smaller transmission distances, the losses in the converter stations may be bigger than in an AC transmission line for the same distance.[29] The cost of the converters may not be offset by reductions in line construction cost and power line loss.

Operating an HVDC scheme requires many spare parts to be kept, often exclusively for one system, as HVDC systems are less standardized than AC systems and technology changes more quickly.

In contrast to AC systems, realizing multi-terminal systems is complex (especially with line commutated converters), as is expanding existing schemes to multi-terminal systems. Controlling power flow in a multi-terminal DC system requires good communication between all the terminals; power flow must be actively regulated by the converter control system instead of relying on the inherent impedance and phase angle properties of an AC transmission line.[30] Multi-terminal systems are therefore rare. As of 2012[update] only two are in service: the Quebec – New England Transmission between Radisson, Nicolet and Sandy Pond[31] and the Sardinia–mainland Italy link which was modified in 1989 to also provide power to the island of Corsica.[32]

High-voltage DC circuit breaker

[edit]HVDC circuit breakers are difficult to build because of arcing: under AC, the voltage inverts and in doing so crosses zero volts dozens of times a second. An AC arc will self-extinguish at one of these zero-crossing points because there cannot be an arc where there is no potential difference. DC will never cross zero volts and never self-extinguish, so arc distance and duration is far greater with DC than the same voltage AC. This means some mechanism must be included in the circuit breaker to force current to zero and extinguish the arc, otherwise arcing and contact wear would be too great to allow reliable switching.

In November 2012, ABB announced the first ultrafast HVDC circuit breaker.[33][34] Mechanical circuit breakers are too slow for use in HVDC grids,[why?] although they have been used for years in other applications. Conversely, semiconductor breakers are fast enough but have a high resistance when conducting, wasting energy and generating heat in normal operation. The ABB breaker combines semiconductor and mechanical breakers to produce a hybrid breaker with both a fast break time and a low resistance in normal operation.

Costs

[edit]Generally, vendors of HVDC systems, such as GE Vernova, Siemens and Hitachi Energy, do not specify pricing details of particular projects; such costs are typically proprietary information between the supplier and the client. Costs vary widely depending on the specifics of the project (such as power rating, circuit length, overhead vs. cabled route, land costs, site seismology, and AC network improvements required at either terminal). A detailed analysis of DC vs. AC transmission costs may be required in situations where there is no obvious technical advantage to DC, and economical reasoning alone drives the selection.

However, some practitioners have provided some information:

For an 8 GW 40 km (25 mi) link laid under the English Channel, the following are approximate primary equipment costs for a 2000 MW 500 kV bipolar conventional HVDC link (excluding way-leaving, on-shore reinforcement works, consenting, engineering, insurance, etc.)

- Converter stations ~£110M (~€120M or $173.7M)

- Subsea cable + installation ~£1M/km (£1.6m/mile) (~€1.2M or ~$1.6M/km; €2m or $2.5m/mile)

So for an 8 GW capacity between the United Kingdom and France in four links, little is left over from £750M for the installed works. Add another £200–300M for the other works depending on additional onshore works required.[35][unreliable source?]

An April 2010 announcement for a 2,000 MW, 64 km (40 mi) line between Spain and France is estimated at €700 million. This includes the cost of a tunnel through the Pyrenees.[36]

Conversion process

[edit]Converter

[edit]At the heart of an HVDC converter station, the equipment that performs the conversion between AC and DC is referred to as the converter. Almost all HVDC converters are inherently capable of converting from AC to DC (rectification) and from DC to AC (inversion), although in many HVDC systems, the system as a whole is optimized for power flow in only one direction. Irrespective of how the converter itself is designed, the station that is operating (at a given time) with power flow from AC to DC is referred to as the rectifier and the station that is operating with power flow from DC to AC is referred to as the inverter.

Early HVDC systems used electromechanical conversion (the Thury system) but all HVDC systems built since the 1940s have used electronic converters. Electronic converters for HVDC are divided into two main categories:

- Line-commutated converters

- Voltage-sourced converters

Line-commutated converters

[edit]Most of the HVDC systems in operation today are based on line-commutated converters (LCCs).

The basic LCC configuration uses a three-phase bridge rectifier known as a six-pulse bridge, containing six electronic switches, each connecting one of the three phases to one of the two DC rails. A complete switching element is usually referred to as a valve, irrespective of its construction. However, with a phase change only every 60°, considerable harmonic distortion is produced at both the DC and AC terminals when this arrangement is used.

An enhancement of this arrangement uses 12 valves in a twelve-pulse bridge. The AC is split into two separate three-phase supplies before transformation. One of the sets of supplies is then configured to have a star (wye) secondary, and the other a delta secondary, establishing a 30° phase difference between the two sets of three phases. With twelve valves connecting each of the two sets of three phases to the two DC rails, there is a phase change every 30°, and harmonics are considerably reduced. For this reason, the twelve-pulse system has become standard on most line-commutated converter HVDC systems built since the 1970s.

With line commutated converters, the converter has only one degree of freedom – the firing angle, which represents the time delay between the voltage across a valve becoming positive (at which point the valve would start to conduct if it were made from diodes) and the thyristors being turned on. The DC output voltage of the converter steadily becomes less positive as the firing angle is increased: firing angles of up to 90° correspond to rectification and result in positive DC voltages, while firing angles above 90° correspond to inversion and result in negative DC voltages. The practical upper limit for the firing angle is about 150–160° because above this, the valve would have insufficient turnoff time.

Early LCC systems used mercury-arc valves, which were rugged but required high maintenance. Because of this, many mercury-arc HVDC systems were built with bypass switchgear across each six-pulse bridge so that the HVDC scheme could be operated in six-pulse mode for short maintenance periods. The last mercury arc system, at the HVDC Inter-Island link, was decommissioned on 1 August 2012.[37]

The thyristor valve was first used in HVDC systems in 1972. The thyristor is a solid-state semiconductor device similar to the diode, but with an extra control terminal that is used to switch the device on at a particular instant during the AC cycle. Because the voltages in HVDC systems, up to 800 kV in some cases, far exceed the breakdown voltages of the thyristors used, HVDC thyristor valves are built using large numbers of thyristors in series. Additional passive components such as grading capacitors and resistors need to be connected in parallel with each thyristor in order to ensure that the voltage across the valve is evenly shared between the thyristors. The thyristor plus its grading circuits and other auxiliary equipment is known as a thyristor level.

Each thyristor valve will typically contain tens or hundreds of thyristor levels, each operating at a different (high) potential with respect to earth. The command information to turn on the thyristors therefore cannot simply be sent using a wire connection – it needs to be isolated. The isolation method can be magnetic but is usually optical. Two optical methods are used: indirect and direct optical triggering. In the indirect optical triggering method, low-voltage control electronics send light pulses along optical fibers to the high-side control electronics, which derives its power from the voltage across each thyristor. The alternative direct optical triggering method dispenses with most of the high-side electronics,[c] instead using light pulses from the control electronics to switch light-triggered thyristors (LTTs).

In a line-commutated converter, the DC current (usually) cannot change direction; it flows through a large inductance and can be considered almost constant. On the AC side, the converter behaves approximately as a current source, injecting both grid-frequency and harmonic currents into the AC network. For this reason, a line commutated converter for HVDC is also considered as a current-source inverter.

Voltage-sourced converters

[edit]Because thyristors can only be turned on (not off) by control action, the control system has only one degree of freedom – when to turn on the thyristor. This is an important limitation in some circumstances.

With some other types of semiconductor devices such as the insulated-gate bipolar transistor (IGBT), both turn-on and turn-off can be controlled, giving a second degree of freedom. As a result, they can be used to make self-commutated converters. In such converters, the electric polarity of DC voltage is usually fixed and the DC voltage, being smoothed by a large capacitance, can be considered constant. For this reason, an HVDC converter using IGBTs is usually referred to as a voltage-sourced converter. The additional controllability gives many advantages, notably the ability to switch the IGBTs on and off many times per cycle in order to improve the harmonic performance. Being self-commutated, the converter no longer relies on synchronous machines in the AC system for its operation. A voltage-sourced converter can therefore feed power to an AC network consisting only of passive loads, something which is impossible with LCC HVDC.

HVDC systems based on voltage-sourced converters normally use the six-pulse connection because the converter produces much less harmonic distortion than a comparable LCC and the twelve-pulse connection is unnecessary.

Most of the VSC HVDC systems built until 2012 were based on the two-level converter, which can be thought of as a six-pulse bridge in which the thyristors have been replaced by IGBTs with inverse-parallel diodes and the DC smoothing reactors have been replaced by DC smoothing capacitors. Such converters derive their name from the discrete, two voltage levels at the AC output of each phase that correspond to the electrical potentials of the positive and negative DC terminals. Pulse-width modulation (PWM) is usually used to improve the harmonic distortion of the converter.

Some HVDC systems have been built with three-level converters, but today most new VSC HVDC systems are being built with some form of multilevel converter, most commonly the modular multilevel converter (MMC), in which each valve consists of a number of independent converter submodules, each containing its own storage capacitor. The IGBTs in each submodule either bypass the capacitor or connect it into the circuit, allowing the valve to synthesize a stepped voltage with very low levels of harmonic distortion.

Converter transformers

[edit]

At the AC side of each converter, a bank of transformers, often three physically separated single-phase transformers, isolate the station from the AC supply, to provide a local earth, and to ensure the correct eventual DC voltage. The output of these transformers is then connected to the converter.

Converter transformers for LCC HVDC schemes are quite specialized because of the high levels of harmonic currents that flow through them, and because the secondary winding insulation experiences a permanent DC voltage, which affects the design of the insulating structure inside the tank.[d] In LCC systems, the transformers also need to provide the 30° phase shift required for harmonic cancellation.

Converter transformers for VSC HVDC systems are usually simpler and more conventional in design than those for LCC HVDC systems.

Reactive power

[edit]A major drawback of HVDC systems using line-commutated converters is that the converters inherently consume reactive power. The AC current flowing into the converter from the AC system lags behind the AC voltage so that, irrespective of the direction of active power flow, the converter always absorbs reactive power, behaving in the same way as a shunt reactor. The reactive power absorbed is at least 0.5 Mvar/MW under ideal conditions and can be higher than this when the converter is operating at higher than usual firing or extinction angle, or reduced DC voltage.

Although at HVDC converter stations connected directly to power stations some of the reactive power may be provided by the generators themselves, in most cases the reactive power consumed by the converter must be provided by banks of shunt capacitors connected at the AC terminals of the converter. The shunt capacitors are usually connected directly to the grid voltage but in some cases may be connected to a lower voltage via a tertiary winding on the converter transformer. Since the reactive power consumed depends on the active power being transmitted, the shunt capacitors usually need to be subdivided into a number of switchable banks (typically four per converter) in order to prevent a surplus of reactive power being generated at low transmitted power. The shunt capacitors are almost always provided with tuning reactors and, where necessary, damping resistors so that they can perform a dual role as harmonic filters.

VSCs, on the other hand, can either produce or consume reactive power on demand, with the result that usually no separate shunt capacitors are needed (other than those required purely for filtering).

Harmonics and filtering

[edit]All electronic power converters generate some degree of harmonic distortion on the AC and DC systems to which they are connected, and HVDC converters are no exception.

With the recently developed MMCs, levels of harmonic distortion may be practically negligible, but with line-commutated converters and simpler types of VSCs, considerable harmonic distortion may be produced on both the AC and DC sides of the converter. As a result, harmonic filters are nearly always required at the AC terminals of such converters, and in HVDC transmission schemes using overhead lines, may also be required on the DC side.

Filters for line-commutated converters

[edit]The basic building block of a line-commutated HVDC converter is the six-pulse bridge. This arrangement produces very high levels of harmonic distortion. It is very costly to provide harmonic filters capable of suppressing such harmonics, so a variant known as the twelve-pulse bridge, consisting of two six-pulse bridges in series with a 30° phase shift between them, is nearly always used. The task of suppressing harmonics from this arrangement is still challenging, but manageable. Line-commutated converters for HVDC are usually include combinations of harmonic filters designed to deal with the 11th and 13th harmonics on the AC side, and 12th harmonic on the DC side. Sometimes, high-pass filters are included to deal with 23rd, 25th, 35th, 37th... on the AC side and 24th, 36th... on the DC side. Sometimes, the AC filters provide damping at lower-order, noncharacteristic harmonics such as 3rd or 5th harmonics.

The task of designing AC harmonic filters for HVDC converter stations is complex and computationally intensive, since in addition to ensuring that the converter does not produce an unacceptable level of voltage distortion on the AC system, it must be ensured that the harmonic filters do not resonate with some component elsewhere in the AC system. Detailed knowledge of the harmonic impedance of the AC system, at a wide range of frequencies, is needed in order to design the AC filters.[38]

DC filters are required only for HVDC transmission systems involving overhead lines. Voltage distortion is not a problem in its own right, since consumers do not connect directly to the DC terminals of the system, so the main design criterion for the DC filters is to ensure that the harmonic currents flowing in the DC lines do not induce interference in nearby open-wire telephone lines.[39] With the rise in digital mobile telecommunications systems, which are much less susceptible to this type of interference, and fiber optic communication which is immune, DC filters are becoming less important for HVDC systems.

Filters for voltage-sourced converters

[edit]Some types of voltage-sourced converters may produce such low levels of harmonic distortion that no filters are required. However, converter types such as the two-level converter, used with pulse-width modulation (PWM), still require some filtering, albeit less than on line-commutated converter systems.

In two-level converters, the harmonic spectrum is shifted to higher frequencies compared to line-commutated converters. The dominant harmonic frequencies are sidebands of the PWM frequency and multiples thereof. In HVDC applications, the PWM frequency is typically around 1 to 2 kHz.[citation needed] The higher frequencies allow the filter equipment to be smaller.

Configurations

[edit]Monopole

[edit]

In a monopole configuration, one of the terminals of the rectifier is connected to earth ground using an electrode. The other terminal, at high voltage relative to ground, is connected to a transmission line. With no metallic return conductor installed, return current flows in the earth (or water) between two stations. This arrangement is a type of single-wire earth return system.

The electrodes are usually located some tens of kilometers from the stations and are connected to the stations via a medium-voltage electrode line. The design of the electrodes themselves depends on whether they are located on land, on the shore or at sea. For the monopolar configuration with earth return, the earth current flow is unidirectional, which means that the design of one of the electrodes (the cathode) can be relatively simple, although the design of anode electrode is quite complex due to corrosion issues associated with electrochemistry.[40]

For long-distance transmission, earth return can be considerably cheaper than alternatives using a dedicated neutral conductor, but it can lead to problems such as:

- Electrochemical corrosion of long-buried metal objects such as pipelines

- Underwater earth-return electrodes in seawater may produce chlorine or otherwise affect water chemistry

- An unbalanced current path may result in a net magnetic field, which can affect magnetic navigational compasses for ships passing over an underwater cable.

These effects can be eliminated with installation of a metallic return conductor between the two ends of the monopolar transmission line. Since one terminal of the converters is connected to earth, the return conductor need not be insulated for the full transmission voltage, which makes it less costly than the high-voltage conductor. The decision of whether or not to use a metallic return conductor is based upon economic, technical and environmental factors.[41]

Modern monopolar systems for pure overhead lines typically carry 2 GW. If underground or underwater cables are used, the typical value is 1 GW.[42]

Most monopolar systems are designed for future bipolar expansion. Transmission line towers may be designed to carry two conductors, even if only one is used initially for the monopole transmission system. The second conductor is either unused, used as electrode line or connected in parallel with the other (as in case of Baltic Cable).[citation needed]

Symmetrical monopole

[edit]An alternative is to use two high-voltage conductors, operating at about half of the DC voltage, with only a single converter at each end. In this arrangement, known as the symmetrical monopole, the converters are earthed only via a high impedance and there is no earth current. The symmetrical monopole arrangement is uncommon with line-commutated converters (the NorNed interconnector being a rare example) but is very common with Voltage Sourced Converters when cables are used.

Bipolar

[edit]

In bipolar transmission a pair of conductors is used, each at a high potential with respect to ground, in opposite polarity. Since these conductors must be insulated for the full voltage, transmission line cost is higher than a monopole with a return conductor. However, there are a number of advantages to bipolar transmission which can make it an attractive option.

- Under normal load, negligible earth-current flows, as in the case of monopolar transmission with a metallic earth-return. This reduces earth return loss and environmental effects.

- When a fault develops in a line, with earth return electrodes installed at each end of the line, approximately half the rated power can continue to flow using the earth as a return path, operating in monopolar mode.

- Since for a given total power rating each conductor of a bipolar line carries only half the current of monopolar lines, the cost of the second conductor is reduced compared to a monopolar line of the same rating.

- In very adverse terrain, the second conductor may be carried on an independent set of transmission towers, so that some power may continue to be transmitted even if one line is damaged.

A bipolar system may also be installed with a metallic earth return conductor.

Bipolar systems may carry as much as 4 GW at voltages of ±660 kV with a single converter per pole, as on the Ningdong–Shandong project in China. With a power rating of 2,000 MW per twelve-pulse converter, the converters for that project were (as of 2010) the most powerful HVDC converters ever built.[43] Even higher powers can be achieved by connecting two or more twelve-pulse converters in series in each pole, as is used in the ±800 kV Xiangjiaba–Shanghai project in China, which uses two twelve-pulse converter bridges in each pole, each rated at 400 kV DC and 1,600 MW.

Submarine cable installations initially commissioned as a monopole may be upgraded with additional cables and operated as a bipole.

A bipolar scheme can be implemented so that the polarity of one or both poles can be changed. This allows the operation as two parallel monopoles. If one conductor fails, transmission can still continue at reduced capacity. Losses may increase if ground electrodes and lines are not designed for the extra current in this mode. To reduce losses in this case, intermediate switching stations may be installed, at which line segments can be switched off or parallelized. This was done at Inga–Shaba HVDC.

Back to back

[edit]A back-to-back station (or B2B for short) is a plant in which both converters are in the same area, usually in the same building. The length of the direct current line is kept as short as possible. HVDC back-to-back stations are used for

- coupling of electricity grids of different frequencies (as in Japan and South America; and the GCC interconnector between Saudi Arabia (60 Hz) and rest of GCC countries (50 Hz) completed in 2009)

- coupling two networks of the same nominal frequency but no fixed phase relationship (as until 1995/96 in Etzenricht, Dürnrohr, Vienna, and the Vyborg HVDC scheme).

- different frequency and phase number (for example, as a replacement for traction current converter plants)

The DC voltage in the intermediate circuit can be selected freely at HVDC back-to-back stations because of the short conductor length. The DC voltage is usually selected to be as low as possible, in order to build a small valve hall and to reduce the number of thyristors connected in series in each valve. For this reason, at HVDC back-to-back stations, valves with the highest available current rating (in some cases, up to 4,500 A) are used.

Multi-terminal systems

[edit]The most common configuration of an HVDC link consists of two converter stations connected by an overhead power line or undersea cable.

Multi-terminal HVDC links, connecting more than two points, are rare. The configuration of multiple terminals can be series, parallel, or hybrid (a mixture of series and parallel). Parallel configuration tends to be used for large capacity stations, and series for lower capacity stations. An example is the 2,000 MW Quebec - New England Transmission system opened in 1992, which is currently the largest multi-terminal HVDC system in the world.[44]

Multi-terminal systems are difficult to realize using line commutated converters because reversals of power are effected by reversing the polarity of DC voltage, which affects all converters connected to the system. With Voltage Sourced Converters, power reversal is achieved instead by reversing the direction of current, making parallel-connected multi-terminals systems much easier to control. For this reason, multi-terminal systems are expected to become much more common in the near future.

China is expanding its grid to keep up with increased power demand, while addressing environmental targets. China Southern Power Grid started a three terminals VSC HVDC pilot project in 2011. The project has designed ratings of ±160 kV/200 MW-100 MW-50 MW and will be used to bring wind power generated on Nanao island into the mainland Guangdong power grid through 32 km (20 mi) of combination of HVDC land cables, sea cables and overhead lines. This project was put into operation on December 19, 2013.[45]

In India, the multi-terminal North-East Agra project is planned for commissioning in 2015–2017. It is rated 6,000 MW, and it transmits power on a ±800 kV bipolar line from two converter stations, at Biswanath Chariali and Alipurduar, in the east to a converter at Agra, a distance of 1,728 km (1,074 mi).[46]

Other arrangements

[edit]Cross-Skagerrak consisted since 1993 of 3 poles, from which 2 were switched in parallel and the third used an opposite polarity with a higher transmission voltage. This configuration ended in 2014 when poles 1 and 2 again were rebuilt to work in bipole and pole 3 (LCC) works in bipole with a new pole 4 (VSC). This is the first HVDC transmission where LCC and VSC poles cooperate in a bipole.

A similar arrangement was the HVDC Inter-Island in New Zealand after a capacity upgrade in 1992, in which the two original converters (using mercury-arc valves) were parallel-switched feeding the same pole and a new third (thyristor) converter installed with opposite polarity and higher operation voltage. This configuration ended in 2012 when the two old converters were replaced with a single, new, thyristor converter.

A scheme patented in 2004[47] is intended for conversion of existing AC transmission lines to HVDC. Two of the three circuit conductors are operated as a bipole. The third conductor is used as a parallel monopole, equipped with reversing valves (or parallel valves connected in reverse polarity). This allows heavier currents to be carried by the bipole conductors, and full use of the installed third conductor for energy transmission. High currents can be circulated through the line conductors even when load demand is low, for removal of ice. As of 2012[update], no tripole conversions are in operation, although a transmission line in India has been converted to bipole HVDC (HVDC Sileru-Barsoor).

Corona discharge

[edit]Corona discharge is the creation of ions in a fluid (such as air) by the presence of a strong electric field. Electrons are torn from neutral air, and either the positive ions or the electrons are attracted to the conductor, while the charged particles drift. This effect can cause considerable power loss, create audible and radio-frequency interference, generate toxic compounds such as oxides of nitrogen and ozone, and bring forth arcing.

Both AC and DC transmission lines can generate coronas, in the former case in the form of oscillating particles, in the latter a constant wind. Due to the space charge formed around the conductors, an HVDC system may have about half the loss per unit length of a high voltage AC system carrying the same amount of power. With monopolar transmission the choice of polarity of the energized conductor leads to a degree of control over the corona discharge. In particular, the polarity of the ions emitted can be controlled, which may have an environmental impact on ozone creation. Negative coronas generate considerably more ozone than positive coronas, and generate it further downwind of the power line, creating the potential for health effects. The use of a positive voltage will reduce the ozone impacts of monopole HVDC power lines.

Applications

[edit]Overview

[edit]The controllability of a current-flow through HVDC rectifiers and inverters, their application in connecting unsynchronized networks, and their applications in efficient submarine cables mean that HVDC interconnectors are often used at national or regional boundaries for the exchange of power (in North America, HVDC connections divide much of Canada and the United States into several electrical regions that cross national borders, although the purpose of these connections is still to connect unsynchronized AC grids to each other). Offshore windfarms also require undersea cables, and their turbines are unsynchronized. In very long-distance connections between two locations, such as power transmission from a large hydroelectric power plant at a remote site to an urban area, HVDC transmission systems may appropriately be used; several schemes of these kind have been built. For interconnectors to Siberia, Canada, India, and the Scandinavian North, the decreased line-costs of HVDC also make it applicable, see List of HVDC projects. Other applications are noted throughout this article.

AC network interconnectors

[edit]AC transmission lines can interconnect only synchronized AC networks with the same frequency with limits on the allowable phase difference between the two ends of the line. Many areas that wish to share power have unsynchronized networks. The power grids of the UK, Northern Europe and continental Europe are not united into a single synchronized network. Japan has 50 Hz and 60 Hz networks. Continental North America, while operating at 60 Hz throughout, is divided into regions which are unsynchronized: East, West, Texas, Quebec, and Alaska. Brazil and Paraguay, which share the enormous Itaipu Dam hydroelectric plant, operate on 60 Hz and 50 Hz respectively. However, HVDC systems make it possible to interconnect unsynchronized AC networks, and also add the possibility of controlling AC voltage and reactive power flow.

A generator connected to a long AC transmission line may become unstable and fall out of synchronization with a distant AC power system. An HVDC transmission link may make it economically feasible to use remote generation sites. Wind farms located off-shore may use HVDC systems to collect power from multiple unsynchronized generators for transmission to the shore by an underwater cable.[48]

In general, however, an HVDC power line will interconnect two AC regions of the power-distribution grid. Machinery to convert between AC and DC power adds a considerable cost in power transmission. The conversion from AC to DC is known as rectification, and from DC to AC as inversion. Above a certain break-even distance (about 50 km; 31 mi for submarine cables, and perhaps 600–800 km; 370–500 mi for overhead cables), the lower cost of the HVDC electrical conductors outweighs the cost of the electronics.

The conversion electronics also present an opportunity to effectively manage the power grid by means of controlling the magnitude and direction of power flow. An additional advantage of the existence of HVDC links, therefore, is potential increased stability in the transmission grid.

Renewable electricity superhighways

[edit]

A number of studies have highlighted the potential benefits of very wide area super grids based on HVDC since they can mitigate the effects of intermittency by averaging and smoothing the outputs of large numbers of geographically dispersed wind farms or solar farms.[49] Czisch's study concludes that a grid covering the fringes of Europe could bring 100% renewable power (70% wind, 30% biomass) at close to today's prices. There has been debate over the technical feasibility of this proposal[50] and the political risks involved in energy transmission across a large number of international borders.[51]

The construction of such green power superhighways is advocated in a white paper that was released by the American Wind Energy Association and the Solar Energy Industries Association in 2009.[52] Clean Line Energy Partners is developing four HVDC lines in the U.S. for long-distance electric power transmission.[53]

In January 2009, the European Commission proposed €300 million to subsidize the development of HVDC links between Ireland, Britain, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden, as part of a wider €1.2 billion package supporting links to offshore wind farms and cross-border interconnectors throughout Europe. Meanwhile, the recently founded Union of the Mediterranean has embraced a Mediterranean Solar Plan to import large amounts of concentrated solar power into Europe from North Africa and the Middle East.[54] Japan-Taiwan-Philippines HVDC interconnector was proposed in 2020. The purpose of this interconnector is to facilitate cross-border renewable power trading with Indonesia and Australia, in preparation for the future Asian Pacific Super Grid.[55]

Advancements in UHVDC

[edit]UHVDC (ultrahigh-voltage direct-current) is shaping up to be the latest technological front in high voltage DC transmission technology. UHVDC is defined as DC voltage transmission of above 800 kV (HVDC is generally just 100 to 800 kV).

One of the problems with current UHVDC supergrids is that – although less than AC transmission or DC transmission at lower voltages – they still suffer from power loss as the length is extended. A typical loss for 800 kV lines is 2.6% over 800 km (500 mi).[56] Increasing the transmission voltage on such lines reduces the power loss, but until recently, the interconnectors required to bridge the segments were prohibitively expensive. However, with advances in manufacturing, it is becoming more and more feasible to build UHVDC lines.

In 2010, ABB built the world's first 800 kV UHVDC in China. The Zhundong–Wannan UHVDC line with 1100 kV, 3,400 km (2,100 mi) length and 12 GW capacity was completed in 2018. As of 2020, at least thirteen UHVDC transmission lines in China have been completed.

While the majority of recent UHVDC technology deployment is in China, it has also been deployed in South America as well as other parts of Asia. In India, a 1,830 km (1,140 mi), 800 kV, 6 GW line between Raigarh and Pugalur is expected to be completed in 2019.[57] In Brazil, the Xingu-Estreito line over 2,076 km (1,290 mi) with 800 kV and 4 GW was completed in 2017, and the Xingu-Rio line over 2,543 km (1,580 mi) with 800 kV and 4 GW was completed in 2019, both to transmit the energy from Belo Monte Dam. As of 2020, no UHVDC line (≥ 800 kV) exists in Europe or North America.

A 1,100 kV link in China was completed in 2019 over a distance of 3,300 km (2,100 mi) with a power capacity of 12 GW.[58][59] With this dimension, intercontinental connections become possible which could help to deal with the fluctuations of wind power and photovoltaics.[60]

See also

[edit]- DC-to-DC converter

- Electrode line

- European super grid

- Flexible AC transmission system

- High-voltage cable

- List of HVDC projects – list of HVDC projects in history, in current operation, and under construction

- Submarine power cable

- Transmission tower

- Valve hall

- Variable-frequency transformer

Notes

[edit]- ^ For a more detailed derivation, see Submarine power cable § High voltage or high current.

- ^ A modern battery storage power station includes transformers and inverters to change energy from alternating current to direct current forms at appropriate voltages.

- ^ A small monitoring electronics unit may still be required for protection of the valve

- ^ The valve side requires more solid insulation.

References

[edit]- ^ Arrillaga, Jos; High Voltage Direct Current Transmission, second edition, Institution of Electrical Engineers, ISBN 0 85296 941 4, 1998.

- ^ Hingorani, N.G. (1996). "High-voltage DC transmission: a power electronics workhorse". IEEE Spectrum. 33 (4): 63–72. Bibcode:1996IEEES..33d..63H. doi:10.1109/6.486634.

- ^ "均为世界之最!"一交一直"两大特高压工程投运_滚动新闻_中国政府网". www.gov.cn. Retrieved 2025-04-21.

- ^ Hughes, Thomas Parke (1993). Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society, 1880–1930. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80182-873-7, pages 120-121

- ^ a b Jos Arrillaga; Yonghe H. Liu; Neville R. Watson; Nicholas J. Murray (9 October 2009). Self-Commutating Converters for High Power Applications. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-74682-0. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Guarnieri, M. (2013). "The Alternating Evolution of DC Power Transmission". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 7 (3): 60–63. Bibcode:2013IIEM....7c..60G. doi:10.1109/MIE.2013.2272238. S2CID 23610440.

- ^ Donald Beaty et al, "Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers 11th Ed.", McGraw Hill, 1978

- ^ "ACW's Insulator Info – Book Reference Info – History of Electrical Systems and Cables".

- ^ R. M. Black The History of Electric Wires and Cables, Peter Perigrinus, London 1983 ISBN 0-86341-001-4 pages 94–96

- ^ Alfred Still, Overhead Electric Power Transmission, McGraw Hill, 1913 page 145, available from the Internet Archive

- ^ ""Shaping the Tools of Competitive Power"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2005.

- ^ Thomas P. Hughes, Networks of Power

- ^ Rissik, H., Mercury-Arc Current Converters, Pitman. 1941, chapter IX.

- ^ ""HVDC TransmissionF"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2008.

- ^ IEEE – IEEE History Center Archived March 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cogle, T.C.J, The Nelson River Project – Manitoba Hydro exploits sub-arctic hydro power resources, Electrical Review, 23 November 1973.

- ^ Dorf, Richard C. (1997). The electrical engineering handbook (illustrated). The electrical engineering handbook series (2 ed.). p. 1343. ISBN 978-0-8493-8574-2.

- ^ "Siemens overhauls 15 converter transformers at Cahora Bassa HVDC link in Mozambique". Press. 2019-06-27. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "HVDC Light® (VSC) | Hitachi Energy". www.hitachienergy.com. Retrieved 2025-03-09.

- ^ European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Institute for Energy Transport (2017-04-28). HVDC submarine power cables in the world: state-of-the-art knowledge (PDF). Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2790/023689. ISBN 978-92-79-52785-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-14. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- ^ Skog, J.E., van Asten, H., Worzyk, T., Andersrød, T., Norned – World's longest power cable, CIGRÉ session, Paris, 2010, paper reference B1-106.

- ^ "SAPEI | References | ABB". Archived from the original on 2017-04-15. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- ^ ABB HVDC Archived 2009-08-13 at the Wayback Machine website

- ^ [1] Archived 2015-09-04 at the Wayback Machine website

- ^ Donald G. Fink, H. Wayne Beatty, Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers 11th Edition, McGraw Hill, 1978, ISBN 0-07-020974-X, pages 15-57 and 15-58

- ^ "An In-depth Comparison of HVDC and HVAC". Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "Connecting the Country with HVDC".

- ^ "HVDC Classic reliability and availability". ABB. Archived from the original on March 30, 2010. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ^ Ghazal, Falahi (5 December 2014). "Design, Modeling and Control of Modular Multilevel Converter based HVDC Systems. - NCSU Digital Repository". www.lib.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-17.

- ^ Donald G. Fink and H. Wayne Beaty (August 25, 2006). Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 14–37 equation 14–56. ISBN 978-0-07-144146-9.

- ^ "The HVDC Transmission Québec–New England". ABB Asea Brown Boveri. Archived from the original on March 5, 2011. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

- ^ The Corsican tapping: from design to commissioning tests of the third terminal of the Sardinia-Corsica-Italy HVDC Billon, V.C.; Taisne, J.P.; Arcidiacono, V.; Mazzoldi, F.; Power Delivery, IEEE Transactions on Volume 4, Issue 1, Jan. 1989 Page(s):794–799

- ^ "ABB solves 100-year-old electrical puzzle – new technology to enable future DC grid". ABB. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Callavik, Magnus; Blomberg, Anders; Häfner, Jürgen; Jacobson, Björn (November 2012), The Hybrid HVDC Breaker: An innovation breakthrough for reliable HVDC grids (PDF), ABB Grid Systems, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2013, retrieved 18 November 2012

- ^ Source works for a prominent UK engineering consultancy but has asked to remain anonymous and is a member of Claverton Energy Research Group

- ^ Spain to invest heavily in transmission grid upgrades over next five years|CSP Today. Social.csptoday.com (2010-04-01). Retrieved on 2011-04-09.

- ^ "Pole 1 decommissioned | Transpower". www.transpower.co.nz. Archived from the original on 2021-10-03. Retrieved 2025-10-07.

- ^ Guide to the specification and design evaluation of AC filters for HVDC systems, CIGRÉ Technical Brochure No. 139, 1999.

- ^ DC side harmonics and filtering in HVDC transmission systems, CIGRÉ Technical Brochure No. 092, 1995.

- ^ "The Ultimate Guide to Anode vs. Cathode in Electrochemistry". Retrieved 2025-10-22.

- ^ Basslink project Archived September 13, 2003, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Comparing Power Transmission Capacities: Why Overhead HVDC Lines Carry More Power Than Underground Cables". fieldboss.com.

- ^ Davidson, C.C.; Preedy, R.M.; Cao, J.; Zhou, C.; Fu, J. (October 2010). Ultra-High-Power Thyristor Valves for HVDC in Developing Countries. 9th International Conference on AC/DC Power Transmission. London: IET. doi:10.1049/cp.2010.0974.

- ^ ABB HVDC Transmission Québec – New England website [dead link]

- ^ Three terminal VSC HVDC in China Archived February 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Developments in multterminal HVDC, retrieved 2014 March 17" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-08-03. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- ^ "Current modulation of direct current transmission lines - BARTHOLD LIONEL O." FPO IP Research & Communities. March 30, 2004. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Schulz, Matthias, "Germany's Offshore Fiasco North Sea Wind Offensive Plagued by Problems", Der Spiegel, September 04, 2012. "The HVDC converter stations are causing the biggest problems." Retrieved 2012-11-13.

- ^ Gregor Czisch (2008-10-24). "Low Cost but Totally Renewable Electricity Supply for a Huge Supply Area – a European/Trans-European Example –" (PDF). 2008 Claverton Energy Conference. University of Kassel. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2008-07-16. The paper was presented at the Claverton Energy conference in Bath, 24 October 2008. Paper Synopsis

- ^ Myth of technical un-feasibility of complex multi-terminal HVDC and ideological barriers to inter-country power exchanges – Czisch | Claverton Group. Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved on 2011-04-09.

- ^ European Super Grid and renewable energy power imports – "ludicrous to suggest this would make Europe more vulnerable" – ? | Claverton Group. Claverton-energy.com. Retrieved on 2011-04-09.

- ^ Green Power Superhighways: Building a Path to America's Clean Energy Future Archived 2017-04-20 at the Wayback Machine, February 2009

- ^ "HVDC Transmission Projects | Clean Line Energy Partners".

- ^ "David Strahan "Green Grids" New Scientist 12 March 2009".

- ^ Itiki, Rodney; Manjrekar, Madhav; Di Santo, Silvio Giuseppe; Machado, Luis Fernando M. (November 2020). "Technical feasibility of Japan-Taiwan-Philippines HVdc interconnector to the Asia Pacific Super Grid". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 133 110161. Bibcode:2020RSERv.13310161I. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110161. S2CID 224858553.

- ^ "HVDC Factsheet from Siemens" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-30.

- ^ "StackPath". 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Changji-Guquan ±1,100 kV UHV DC Transmission Project Starts Power Transmission". SGCC. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "ABB wins orders of over $300 million for world's first 1,100 kV UHVDC power link in China". ABB. 2016-07-19. Archived from the original on 2018-02-24. Retrieved 2017-03-13.

- ^ "The Future of Power Is Transcontinental, Submarine Supergrids". Bloomberg.com. 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2021-09-06.

External links

[edit]- China's Ambitious Plan to Build the World's Biggest Supergrid, IEEE Spectrum (2019)

- https://web.archive.org/web/ished by International Council on Large Electric Systems (CIGRÉ)

- World Bank briefing document about HVDC systems

- UHVDC challenges explained from Siemens Archived 2013-01-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Windpowerengineering.com article entitled "Report: HVDC converters globally to hit $89.6 billion by 2020" By Paul Dvorak, dated 18. September 2013

- Elimination of commutation failure by "Flexible LCC HVDC" explained

- Reactive power and voltage control by "Flexible LCC HVDC" explained

High-voltage direct current

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and principles

High-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission is a technology for delivering large amounts of electrical power over long distances using direct current at voltages typically exceeding 100 kV, in contrast to conventional alternating current (AC) systems that dominate most power grids.[10][11] This approach enables efficient bulk power transfer, particularly where AC transmission would incur excessive losses or instability. The core principles of HVDC revolve around the steady flow of direct current, governed by the power equation , where is the transmitted power, is the constant DC voltage, and is the DC current.[12] Unlike AC systems, HVDC eliminates reactive power components, which in AC transmission consume capacity without contributing to useful work and necessitate additional compensation equipment. Transmission losses in HVDC are reduced over long distances because DC avoids the skin effect—where AC current concentrates near the conductor surface, increasing effective resistance—and eliminates dielectric charging currents that cause capacitive losses in AC lines, especially in underground or submarine cables.[13] These attributes make HVDC particularly advantageous for spans beyond 600 km, where total losses can be 20-50% lower than equivalent AC lines.[2] HVDC insulation design differs fundamentally from AC systems due to the unidirectional electric field, which promotes space charge accumulation within dielectrics such as cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) used in extruded cables. Under DC stress, charges injected from electrodes or generated internally trap at material interfaces, distorting the field distribution and exacerbating local stresses, particularly with temperature gradients or polarity reversals in line-commutated converters. This contrasts with AC insulation, designed primarily for peak voltage and alternating fields without sustained charge buildup, necessitating DC-specific materials, additives to reduce charge mobility, and testing protocols like polarity reversal withstand to prevent premature aging, electrical treeing, and breakdown.[14][15] A typical HVDC system comprises a rectifier at the sending end to convert AC grid power to DC, a dedicated DC transmission line, and an inverter at the receiving end to reconvert DC to AC for local distribution.[12] Fundamentally, DC flow adheres to Ohm's law in its simplest form, , treating the line as purely resistive without the inductive and capacitive elements that introduce impedance in AC circuits and complicate voltage regulation.[1][16] HVDC voltage levels are classified as standard systems operating between ±100 kV and ±500 kV for most applications, while ultra-high voltage direct current (UHVDC) extends to ±800 kV or above, supporting capacities exceeding 6 GW over 2000 km with losses under 3% per 1000 km.[13]Comparison with AC transmission

High-voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission systems provide notable efficiency benefits over high-voltage alternating current (HVAC) systems, especially for long-distance applications. Unlike HVAC, where power transmission involves both active and reactive components leading to higher currents, HVDC transmits only active power (P = VI), resulting in lower current for equivalent power levels and thus reduced resistive (I²R) losses.[17] HVDC overhead lines also exhibit lower corona losses compared to HVAC equivalents, as the constant DC voltage produces less ionization in the surrounding air than the oscillating AC waveform.[12] Typical line losses for HVDC are approximately 3.5% per 1000 km, about half the 6.7% for comparable HVAC lines.[18] In underground and submarine cables, HVDC avoids the capacitive charging currents that plague HVAC systems, where a significant portion of the current is used to charge the cable capacitance rather than transmit usable power. This allows HVDC cables to carry 2-3 times the power capacity of equivalent AC cables without the need for intermediate compensation.[12] Overall, HVDC losses can be 20-50% lower than HVAC for long distances, making it preferable for bulk power transfer over extended routes.[2] HVDC enhances system stability in ways HVAC cannot, primarily through its ability to link asynchronous AC grids operating at different frequencies or phase angles, enabling controlled power flow without requiring synchronization. Voltage-source converter (VSC)-HVDC configurations further provide black-start capability, allowing the system to energize and restart a de-energized AC grid independently during blackouts, which improves overall grid resilience. HVDC proves more suitable for specific transmission scenarios, such as long overhead lines or submarine cables, where HVAC faces limitations from reactive power management and higher losses. The economic break-even distance—beyond which HVDC's lower operational losses outweigh the higher converter costs—is typically over 500 km for overhead lines and over 50 km for submarine applications.[2][19]| Aspect | HVDC Advantage | HVAC Equivalent | Key Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Line Losses (per 1000 km) | ~3.5% | ~6.7% | Due to lower current and no reactive losses; converter stations add ~1-3% total.[18] |

| Submarine/Underground Cable Capacity | 2-3x higher power rating | Limited by ~30-50% charging current loss | No capacitance charging in HVDC enables fuller utilization.[12] |

| Asynchronous Grid Linking | Full power transfer possible | Requires synchronization; limited or impossible | Enables regional interconnections without phase matching. |

| Black-Start Capability | Yes (VSC-HVDC) | No | Supports grid restoration from blackout. |

Historical Development

Early systems

The earliest high-voltage direct current (HVDC) systems emerged in the late 19th century, relying on electromechanical conversion through motor-generator sets known as the Thury system, developed by Swiss engineer René Thury. These systems connected multiple DC generators in series to achieve higher voltages, typically ranging from 10 kV to 150 kV, for transmitting power over relatively short distances of up to 230 km. Designed primarily for hydroelectric applications, the Thury system avoided the need for electronic conversion by using mechanical rotation to maintain constant current, with series operation ensuring all machines ran at the same speed and current. At least 11 such installations operated between 1889 and 1911 across Europe, including a notable 1905 line from Moutiers to Lyon in France, which spanned 230 km and delivered power at around 58 kV for urban supply.[20][21] The transition to electronic conversion began in the 1930s with the advent of mercury arc valves, which enabled more efficient AC-to-DC rectification for larger-scale HVDC applications. Invented by Peter Cooper Hewitt in 1902 and refined through the 1920s, these valves operated on the principle of a mercury pool cathode and multiple anodes immersed in a vacuum envelope, where AC voltage applied to the anodes ionized the mercury vapor to conduct current unidirectionally during positive half-cycles. In HVDC setups, grids were added to the anodes for control, allowing precise timing of conduction, while commutation—turning off the valve—was achieved naturally via the AC grid's voltage reversal, eliminating the need for forced extinction. The first experimental mercury arc HVDC link, a 3 MW, 45 kV system, connected Laufenburg in Switzerland to Hagenacker in Germany in 1932, demonstrating feasibility but highlighting challenges in scaling.[20][22] Commercial deployment of mercury arc technology accelerated in the 1940s and 1950s, though initial power ratings remained below 100 MW due to valve limitations. An early example was the 1936 experimental 5 MW, 20 kV line between Mechanicville and Schenectady in New York, using mercury arc rectifiers to test short-distance transmission. In Europe, the Elbe Project in Germany, ordered in 1941 as a 60 MW, ±200 kV link from Vockerode to Berlin over 115 km and completed in 1945, was never commissioned due to World War II, with its components repurposed for the Moscow-Kashira line operational from 1951. A key milestone came in 1954 with the Gotland HVDC link in Sweden, the world's first commercial submarine HVDC system at 20 MW and 100 kV over 96 km, linking the mainland to Gotland island using mercury arc valves for reliable power supply to the isolated grid.[20][5][23] Despite these advances, mercury arc valves imposed significant limitations on early HVDC systems, including high maintenance requirements from the need to handle mercury vapor and frequent arc-backs—unintended reverse conduction that could damage equipment—and relatively low power ratings constrained by valve size and cooling needs. Each valve, often housed in large steel tanks weighing over 1,000 kg, required constant monitoring to prevent failures, contributing to operational costs and reliability issues that limited initial installations to under 100 MW. These challenges spurred ongoing refinements in valve design and control, paving the way for subsequent technological shifts while establishing HVDC's viability for specialized applications like undersea cables.[20][24]Solid-state evolution

The transition to solid-state technology in high-voltage direct current (HVDC) systems began in the late 1960s, with thyristor valves gradually replacing mercury-arc valves due to their superior ruggedness, reliability, lower maintenance requirements, and cost-effectiveness.[20] The first experimental use of a thyristor valve in an operational HVDC project occurred in 1967, when one mercury-arc valve in Sweden's Gotland link was substituted with a thyristor unit, marking the initial commercial application of semiconductor technology in HVDC transmission. By the early 1970s, thyristors had enabled the design of fully solid-state converters, eliminating the need for mercury and its associated environmental and operational hazards while allowing for more compact and efficient valve structures.[25] The world's first complete HVDC scheme based entirely on thyristor valves was the Eel River back-to-back station in New Brunswick, Canada, commissioned in 1972 with a rating of 320 MW at ±80 kV.[26] This project demonstrated the feasibility of all-solid-state conversion for asynchronous interconnections, transmitting power between the 60 Hz New Brunswick system and the 50 Hz Quebec network, and set the stage for broader adoption in the 1970s.[27] Throughout the decade, thyristor technology facilitated larger-scale deployments, such as the upgrade of the Gotland link in 1970 to 30 MW at 150 kV using series-connected thyristors alongside remaining mercury-arc units, which improved control and efficiency before full replacement.[28] These advancements addressed the limitations of mercury-arc systems, including high maintenance from vacuum seals and arc instability, enabling HVDC applications in more challenging environments with reduced downtime.[20] In the 1980s, thyristor-based systems expanded to ultra-high-voltage levels, exemplified by the Pacific DC Intertie in the United States, originally commissioned in 1970 with mercury-arc valves at ±400 kV and 1,440 MW but upgraded in 1985 with additional thyristor converters to reach ±500 kV and 2,000 MW capacity.[29] This retrofitting highlighted the scalability of thyristors for long-distance transmission, with the project's line extending 1,362 km from Oregon to California.[30] Concurrently, developments in capacitor-commutated converters (CCC) emerged to enhance commutation performance in weak AC networks, with early implementations like the 1985 Miles City back-to-back station in Montana, USA, rated at 200 MW and 82 kV, incorporating series capacitors to improve stability and reduce reactive power demands.[31] By the 1990s, thyristor technology reached its pinnacle in scale with Brazil's Itaipu project, featuring two bipoles at ±600 kV and 3,150 MW each (totaling 6,300 MW), commissioned starting in 1984 for bipole 1 and 1990 for bipole 2, transmitting hydroelectric power over 800 km to São Paulo. Thyristor valves offered significant advantages over mercury-arc predecessors, including the ability to handle higher power ratings—up to 6 GW in bipolar configurations like Itaipu—through series and parallel stacking of devices, while achieving lower overall transmission losses via improved efficiency in large-scale operations (typically 0.7-1% per 1,000 km compared to AC equivalents). The absence of mercury eliminated toxic material handling risks and vacuum maintenance issues, contributing to enhanced environmental safety and operational reliability with forced outage rates below 0.5% in mature systems.[25] Technically, thyristor firing is precisely controlled by applying a gate pulse to initiate conduction, with turn-off achieved via line commutation when the AC voltage reverses, allowing dynamic adjustment of the firing angle to regulate DC voltage and power flow.[32] To mitigate harmonics generated by the converter bridges—primarily the 11th, 13th, 23rd, and 25th orders—12-pulse configurations were standard, employing two six-pulse bridges phase-shifted by 30 degrees via star-delta transformer windings, which canceled lower-order harmonics (5th and 7th) and reduced filtering needs by up to 50% compared to six-pulse setups.[33] This evolution in the mid-to-late 20th century solidified thyristor-based HVDC as a reliable backbone for bulk power transfer, paving the way for global interconnections.Modern converter advancements