Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stereophonic sound

View on Wikipedia

Stereophonic sound, commonly shortened to stereo, is a method of sound reproduction that recreates a multi-directional, 3-dimensional audible perspective. This is usually achieved by using two independent audio channels through a configuration of two loudspeakers (or stereo headphones) in such a way as to create the impression of sound heard from various directions, as in natural hearing.

Because the multi-dimensional perspective is the crucial aspect, the term stereophonic also applies to systems with more than two channels or speakers, such as quadraphonic and surround sound. Binaural sound systems are also stereophonic.

Stereo sound has been in common use since the 1970s in entertainment media such as broadcast radio, recorded music, television, video cameras, cinema, computer audio, and the Internet.

Etymology

[edit]The word stereophonic derives from the Greek στερεός (stereós, "firm, solid")[1] + φωνή (phōnḗ, "sound, tone, voice").[2]

Description

[edit]

Stereo sound systems can be divided into two forms: the first is true or natural stereo, in which a live sound is captured, with any natural reverberation present, by an array of microphones. The signal is then reproduced over multiple loudspeakers to recreate, as closely as possible, the live sound.

Secondly artificial or pan stereo, in which a single-channel (mono) sound is reproduced over multiple loudspeakers. By varying the relative amplitude of the signal sent to each speaker, an artificial direction (relative to the listener) can be suggested. The control that is used to vary this relative amplitude of the signal is known as a pan-pot (panoramic potentiometer). By combining multiple pan-potted mono signals, a complete, yet entirely artificial, sound field can be created.

In technical usage, true stereo means sound recording and sound reproduction that uses stereographic projection to encode the relative positions of objects and events recorded.[citation needed]

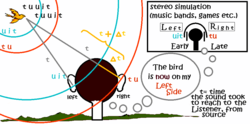

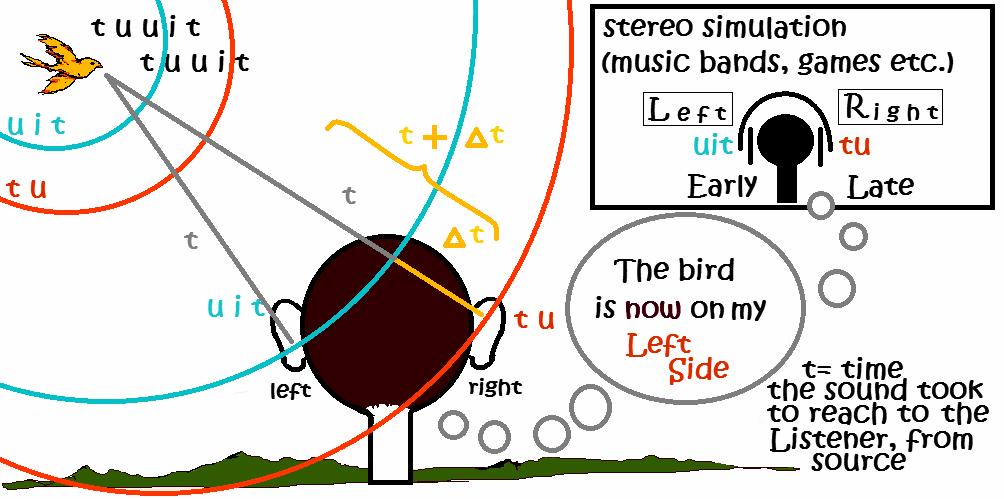

During two-channel stereo recording, two microphones are placed in strategically chosen locations relative to the sound source, with both recording simultaneously. The two recorded channels will be similar, but each will have distinct time-of-arrival and sound-pressure-level information. During playback, the listener's brain uses those subtle differences in timing and sound level to triangulate the positions of the recorded objects. Since each microphone records each wavefront at a slightly different time, the wavefronts are out of phase; as a result, constructive and destructive interference can occur if both tracks are played back on the same speaker. This phenomenon is known as phase cancellation. Coincident-pair microphone arrangements produce stereo recordings with minimal phase difference between channels.[3]

History

[edit]

Early work

[edit]Clément Ader demonstrated the first two-channel audio system in Paris in 1881, with a series of telephone transmitters connected from the stage of the Paris Opera to a suite of rooms at the Paris Electrical Exhibition, where listeners could hear a live transmission of performances through receivers for each ear. Scientific American reported:

Every one who has been fortunate enough to hear the telephones at the Palais de l'Industrie has remarked that, in listening with both ears at the two telephones, the sound takes a special character of relief and localization which a single receiver cannot produce... This phenomenon is very curious, it approximates to the theory of binauricular audition, and has never been applied, we believe, before to produce this remarkable illusion to which may almost be given the name of auditive perspective.[4]

This two-channel telephonic process was commercialized in France from 1890 to 1932 as the Théâtrophone, and in England from 1895 to 1925 as the Electrophone. Both were services available by coin-operated receivers at hotels and cafés, or by subscription to private homes.[5]

There have been cases in which two recording lathes (for the sake of producing two simultaneous masters) were fed from two separate microphones; when both masters survive, modern engineers have been able to synchronize them to produce stereo recordings from a time before intentional stereophonic recording technology existed.[6]

Modern stereophonic sound

[edit]Modern stereophonic technology was invented in the 1930s by British engineer Alan Blumlein at EMI, who patented stereo records, stereo films, and also surround sound.[7] In early 1931, Blumlein and his wife were at a local cinema. The sound reproduction systems of the early talkies invariably only had a single set of speakers – which could lead to the somewhat disconcerting effect of the actor being on one side of the screen whilst his voice appeared to come from the other. Blumlein declared to his wife that he had found a way to make the sound follow the actor across the screen. The genesis of these ideas is uncertain, but he explained them to Isaac Shoenberg in the late summer of 1931. His earliest notes on the subject are dated September 25, 1931, and his patent had the title "Improvements in and relating to Sound-transmission, Sound-recording and Sound-reproducing Systems". The application was dated December 14, 1931, and was accepted on June 14, 1933, as UK patent number 394,325.[8] The patent covered many ideas in stereo, some of which are used today and some not. Some 70 claims include:

- A shuffling circuit, which aimed to preserve the directional effect when sound from a spaced pair of microphones was reproduced via stereo headphones instead of a pair of loudspeakers;

- The use of a coincident pair of velocity microphones with their axes at right angles to each other, which is still known as a Blumlein pair;

- Recording two channels in the single groove of a record using the two groove walls at right angles to each other and 45 degrees to the vertical;

- A stereo disc-cutting head;

- Using hybrid transformers to matrix between left and right signals and sum and difference signals;

Blumlein began binaural experiments as early as 1933, and the first stereo discs were cut later the same year, twenty-five years before that method became the standard for stereo phonograph discs. These discs used the two walls of the groove at right angles in order to carry the two channels. In 1934, Blumlein recorded Mozart's Jupiter Symphony conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham at Abbey Road Studios in London using his vertical-lateral technique.[7] Much of the development work on this system for cinematic use did not reach completion until 1935. In Blumlein's short test films (most notably, "Trains at Hayes Station", which lasts 5 minutes 11 seconds, and, "The Walking & Talking Film"), his original intent of having the sound follow the actor was fully realized.[9]

In the United States, Harvey Fletcher of Bell Laboratories was also investigating techniques for stereophonic recording and reproduction. One of the techniques investigated was the wall of sound, which used an enormous array of microphones hung in a line across the front of an orchestra. Up to 80 microphones were used, and each fed a corresponding loudspeaker, placed in an identical position, in a separate listening room. Several stereophonic test recordings, using two microphones connected to two styli cutting two separate grooves on the same wax disc, were made with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra at Philadelphia's Academy of Music in March 1932. The first (made on March 12, 1932), of Scriabin's Prometheus: Poem of Fire, is the earliest known surviving intentional stereo recording.[10] The performance was part of an all-Russian program including Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition in the Ravel orchestration, excerpts of which were also recorded in stereo.[11]

Bell Laboratories gave a demonstration of three-channel stereophonic sound on April 27, 1933, with a live transmission of the Philadelphia Orchestra from Philadelphia to Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. over multiple Class A telephone lines. Leopold Stokowski, normally the orchestra's conductor, was present in Constitution Hall to control the sound mix. Five years later, the same system would be expanded onto multichannel film recording and used from the concert hall in Philadelphia to the recording labs at Bell Labs in New Jersey in order to record Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940) in what Disney called Fantasound.[citation needed]

Later that same year, Bell Labs also demonstrated binaural sound, at the Chicago World's Fair in 1933 using a dummy with microphones instead of ears.[12] The two signals were sent out over separate AM station bands.[13]

Carnegie Hall demonstration

[edit]Utilizing selections recorded by the Philadelphia Orchestra, under the direction of Leopold Stokowski, intended for but not used in Walt Disney's Fantasia, the Carnegie Hall demonstration by Bell Laboratories on April 9 and 10, 1940, used three huge speaker systems. Synchronization was achieved by making the recordings in the form of three motion picture soundtracks recorded on a single piece of film with a fourth track being used to regulate volume expansion. This was necessary due to the limitations of dynamic range on optical motion picture film of the period; however, the volume compression and expansion were not fully automatic, but were designed to allow manual studio enhancement; i.e., the artistic adjustment of overall volume and the relative volume of each track in relation to the others. Stokowski, who was always interested in sound reproduction technology, personally participated in the enhancement of the sound at the demonstration.

The speakers produced sound levels of up to 100 decibels, and the demonstration held the audience "spellbound, and at times not a little terrified", according to one report.[14] Sergei Rachmaninoff, who was present at the demonstration, commented that it was "marvellous" but "somehow unmusical because of the loudness." "Take that Pictures at an Exhibition", he said. "I didn't know what it was until they got well into the piece. Too much 'enhancing', too much Stokowski."

Motion picture era

[edit]In 1937, Bell Laboratories in New York City gave a demonstration of two-channel stereophonic motion pictures, developed by Bell Labs and Electrical Research Products, Inc.[15] Once again, conductor Leopold Stokowski was on hand to try out the new technology, recording onto a special proprietary nine-track sound system at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, during the making of the movie One Hundred Men and a Girl for Universal Pictures in 1937, after which the tracks were mixed down to one for the final soundtrack.[16][17] A year later, MGM started using three tracks instead of one to record the musical selections of movie soundtracks, and very quickly upgraded to four. One track was used for dialogue, two for music, and one for sound effects. The very first two-track recording MGM made (although released in mono) was "It Never Rains But What It Pours" by Judy Garland, recorded on June 21, 1938, for the movie Love Finds Andy Hardy.

In the early 1940s, composer-conductor Alfred Newman directed the construction of a sound stage equipped for multichannel recording for 20th Century Fox studios. Several soundtracks from this era still exist in their multichannel elements, some of which have been released on DVD, including How Green Was My Valley, Anna and the King of Siam, The Day the Earth Stood Still and Sun Valley Serenade which, along with Orchestra Wives, feature the only stereophonic recordings of the Glenn Miller Orchestra as it was during its heyday of the Swing Era.

Fantasound

[edit]Walt Disney began experimenting with multichannel sound in the early 1930s as noted above.[18] The first commercial motion picture to be exhibited with stereophonic sound was Walt Disney's Fantasia, released in November 1940, for which a specialized sound process (Fantasound) was developed. As in the Carnegie Hall demonstrations six months earlier, Fantasound used a separate film containing four optical soundtracks. Three of the tracks were used to carry left, center and right audio, while the fourth track carried three tones which individually controlled the volume level of the other three.[19][20] The film was not initially a financial success, however, after two months of road-show exhibition in selected cities, its soundtrack was remixed into mono sound for general release. It was not until its 1956 re-release that stereo sound was restored to the film.

Cinerama

[edit]A Cinerama demonstration film by Lowell Thomas and Mike Todd titled This is Cinerama was released on September 30, 1952. The format was a widescreen process featuring three separate 35 mm motion picture films plus a separate sound film running in synchronization with one another at 26 fps, adding one picture panel each to the viewer's left and right at 45-degree angles, in addition to the usual front and center panel.

The Cinerama audio soundtrack technology, developed by Hazard E. Reeves, utilized seven discrete sound tracks on full-coat magnetic 35 mm film. The system featured five main channels behind the screen, two surround channels in the rear of the theater, plus a sync track to interlock the four machines, which were specially outfitted with aircraft servo-motors made by Ampex.

The advent of multitrack magnetic tape and film recording of this nature made high-fidelity synchronized multichannel recording more technically straightforward, though costly. By the early 1950s, all of the major studios were recording on 35 mm magnetic film for mixing purposes, and many of these so-called individual angles still survive, allowing for soundtracks to be remixed into stereo or even surround.

In April 1953, while This is Cinerama was still playing only in New York City, most moviegoing audiences heard stereophonic sound for the first time with House of Wax, an early 3-D film starring Vincent Price and produced by Warner Bros. Unlike the 4-track mag release-print stereo films of the period which featured four thin strips of magnetic material running down the length of the film, inside and outside the sprocket holes, the sound system developed for House of Wax, dubbed WarnerPhonic, was a combination of a 35 mm fully coated magnetic film that contained the audio tracks for left, center and right speakers, interlocked with the two dual-strip Polaroid system projectors, one of which carried a mono optical surround track and one that carried a mono backup track use in the event anything should go wrong.

Only two other films featured this unique hybrid WarnerPhonic sound: the 3-D production of The Charge at Feather River, and Island in the Sky. Unfortunately, as of 2012, the stereo magnetic tracks to both these films are considered lost forever. In addition, a large percentage of 3-D films carried variations on three-track magnetic sound: It Came from Outer Space; I, the Jury; The Stranger Wore a Gun; Inferno; Kiss Me, Kate; and many others.

Widescreen

[edit]Inspired by Cinerama, the movie industry moved quickly to create simpler and cheaper widescreen systems, the first of which, Todd-AO, was developed by Broadway promoter Michael Todd with financial backing from Rodgers and Hammerstein, to use a single 70 mm film running at 30 frames per second with 6 magnetic soundtracks, for their screen presentation of Oklahoma!. Major Hollywood studios immediately rushed to create their own unique formats, such as MGM's Camera 65, Paramount Pictures' VistaVision and Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation's CinemaScope, the latter of which used up to four separate magnetic soundtracks.

VistaVision took a simplified, low-cost approach to stereophonic sound; its Perspecta system featured only a monaural track, but through subaudible tones, it could change the direction of the sound to come from the left, right or both directions at once.

Because of the standard 35 mm-size film, CinemaScope and its stereophonic sound was capable of being retrofitted into existing theaters. CinemaScope 55 was created by the same company in order to use a larger form of the system (55 mm instead of 35 mm) to allow for greater image clarity onscreen, and was supposed to have had 6-track stereo instead of four. However, because the film needed a new, specially designed projector, the system proved impractical, and the two films made in the process, Carousel and The King and I, were released in 35 mm CinemaScope reduction prints. To compensate, the premiere engagement of Carousel used a six-track magnetic full-coat in an interlock, and a 1961 re-release of The King and I, featured the film printed down to 70 mm with a six-channel soundtrack.

Eventually, 50 complete sets of combination 55/35 mm projectors and penthouse reproducers were completed and delivered by Century and Ampex, respectively, and 55 mm release print sound equipment was delivered by Western Electric. Several samples of 55 mm sound prints can be found in the Sponable Collection at the Film and Television Archives at Columbia University. The subsequently abandoned 55/35 mm Century projector eventually became the Century JJ 70/35MM projector.

Todd-AO

[edit]After this disappointing experience with their proprietary CinemaScope 55 mm system, Fox purchased the Todd-AO system and re-engineered it into a more modern 24 fps system with new 65 mm self-blimped production cameras (Mitchell BFC, "Blimped Fox Camera"), new 65 mm MOS cameras (Mitchell FC, "Fox Camera") and new Super Baltar lenses in a wide variety of focal lengths, first employed on South Pacific. Essentially, although Todd-AO was also available to others, the format became Fox's premier origination and presentation apparatus, replacing the CinemaScope 55 mm system. Current DVDs of the two CinemaScope feature titles were transferred from the original 55 mm negatives, often including the separate 35 mm films as extras for comparison.

Back to mono

[edit]Beginning in 1957, films recorded in stereo (except for those shown in Cinerama or Todd-AO) carried an alternate mono track for theaters not ready or willing to re-equip for stereo.[21] From then until about 1975, when Dolby Stereo was used for the first time in films, most motion pictures – even some from which stereophonic soundtrack albums were made, such as Zeffirelli's Romeo and Juliet – were still released in monaural sound,[22] stereo being reserved almost exclusively for expensive musicals such as West Side Story,[23] My Fair Lady[24] and Camelot,[25] or epics such as Ben-Hur[26] and Cleopatra.[27] Stereo was also reserved for dramas with a strong reliance on sound effects or music, such as The Graduate.[28]

Dolby Stereo

[edit]The Westrex Stereo Variable-Area system was developed in 1977 for Star Wars, and was no more expensive to manufacture in stereo than it was for mono. The format employs the same Western Electric/Westrex/Nuoptix RA-1231 recorder, and coupled with QS quadraphonic matrixing technology licensed to Dolby Labs from Sansui, this system can produce the same left, center, right and surround sound of the original CinemaScope system of 1953 by using a single standard-width optical track. This important development, marketed as Dolby Stereo, finally brought stereo sound to so-called flat (non-anamorphic) widescreen films, most commonly projected at aspect ratios of 1.75:1 or 1.85:1.

70 mm projection

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2014) |

Producers often took advantage of the six magnetic soundtracks available for 70 mm film release prints, and productions shot in either 65 mm or to save money, in 35 mm and then blown up to 70 mm. In these instances, the 70 mm prints would be mixed for stereo, while the 35 mm reduction prints would be remixed for mono.

Some films shot in 35 mm, such as Camelot, featured four-track stereophonic sound and were then blown up to 70 mm so that they could be shown on a giant screen with six-track stereophonic sound. Unfortunately however, many of these presentations were only pseudo stereo, utilizing a somewhat artificial six-track panning method. A process known somewhat derogatorily as the Columbia Spread was often used to synthesize Left Center and Right Center from a combination of Left and Center and Right and Center, respectively, or, for effects, the effect could be panned anywhere across the five-stage speakers using a one-in/five-out pan pot. Dolby, who did not approve of this practice, which results in loss of separation, instead used the left center and right center channels for LFE (low-frequency effects), utilizing the bass units of the otherwise redundant intermediate front speakers, and later the unused HF capacity of these channels to provide for stereo surround in place of the mono surround.

Dolby Digital

[edit]Dolby Stereo was succeeded by Dolby Digital 5.1 in the cinema, which retained the Dolby Stereo 70 mm 5.1 channel layout, and more recently with the introduction of digital cinema, Dolby Surround 7.1 and Dolby Atmos in 2010 and 2012 respectively.

Modern home audio and video

[edit]

The progress of stereophonic sound was paced by the technical difficulties of recording and reproducing two or more channels in synchronization with one another and by the economic and marketing issues of introducing new audio media and equipment. A stereo system can cost up to twice as much as a monophonic system since a stereo system contains two preamplifiers, two amplifiers, and two speaker systems. In addition, the user would need an FM stereo tuner to upgrade any tape recorder to a stereo model and to have their phonograph fitted with a stereo cartridge. In the early days, it was unclear whether consumers would think the sound was so much better to be worth twice the price.

Stereo experiments on disc

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2014) |

Lateral and vertical recording

[edit]Thomas Edison had been recording in a hill-and-dale (vertically modulated) format on his cylinders and discs since 1877, and Berliner had been recording in a side-to-side (lateral) format since shortly thereafter. Each format developed on its own trajectory until the late 1920s, when electric recording on disc, utilizing a microphone, surpassed acoustic recording, which required a loud performance into what amounted to a megaphone in reverse.

At that time, AM radio had been around for roughly a decade, and broadcasters were looking for better materials from which to make phonograph records as well as a better format in which to record them to play over the narrow and thus inherently noisy radio channel. As radio had been playing the same shellac discs available to the public, it was found that, even though the playback system was now electric rather than acoustic, the surface noise on the disc would mask the music after just a few plays.

The development of acetate, bakelite, and vinyl, and the production of radio broadcast transcriptions, helped to solve this. Once these considerably quieter compounds were developed, it was discovered that the rubber-idler-wheel-driven turntables of the period had a great deal of low-frequency rumble – but only in the lateral plane. So, even though with all other factors being equal, the vertical plane of recording on disc had the higher fidelity, it was decided to record vertically to produce higher-fidelity recordings on these new materials, for two reasons, the increase in fidelity by avoiding the lateral rumble and to create incompatibility with home phonographs which, with their lateral-only playback systems, would only produce silence from a vertically modulated disc.

After 33+1⁄3 RPM recording had been perfected for the movies in 1927, the speed of radio program transcriptions was reduced to match, once again to inhibit playback of the discs on normal home consumer equipment. Even though the stylus size remained the same as consumer records at either 3 mils (76 μm) or 2.7 mils (69 μm), the disc size was increased from 12 inches (30 cm) to the same 16 inches (41 cm) as those used in early talking pictures in order to create further incompatibility. Now, not only could the records not be played on home equipment due to incompatible recording format and speed, they would not even fit on the player, which suited the copyright holders.

Two-channel high fidelity and other experiments

[edit]An experimental format in the 1920s split the signal into two parts, bass and treble, and recorded the treble on its own track near the edge of the disc in a lateral format, minimizing high-frequency distortion, and recorded the bass on its own track in a vertical fashion to minimize rumble. The overhead in this scheme limited the playing time to slightly longer than a single, even at 33+1⁄3 RPM on a 12-inch disc.

Another failed experiment in the late 1920s and early '30s involved recording the left channel on one side of the disc and recording the right channel on the other side of the disc. These were manufactured on twin film-company recording lathes which ran in perfect sync with one another, and were capable of counter-clockwise as well as conventional clockwise recording. Each master was run separately through the plating process, lined up to match, and subsequently mounted in a press. The dual-sided stereo disc was then played vertically, first in a system that featured two tonearms on the same post facing one another. The system had trouble keeping the two tonearms in their respective synchronous revolutions.

Five years later, Bell Labs was experimenting with a two-channel lateral-vertical system, where the left channel was recorded laterally and the right channel was recorded vertically, still utilizing a standard 3 mil 78 RPM groove, over three times larger than the modern LP stylus of the late 20th century. In this system all the low-frequency rumble was in the left channel and all the high-frequency distortion was in the right channel. Over a quarter of a century later, it was decided to tilt the recording head 45 degrees off to the right side so that both the low-frequency rumble and high-frequency distortion were shared equally by both channels, producing the 45/45 system we know today.

Emory Cook

[edit]In 1952, Emory Cook (1913–2002), who already had become famous by designing new feedback disk-cutter heads to improve sound from tape to vinyl, took the two-channel high-fidelity system described above and developed a binaural[note 1] record out of it. This consisted of two separate channels cut into two separate groups of grooves running next to each other, one running from the edge of the disc to halfway through and the other starting at the halfway point and ending up towards the label. He used two lateral grooves with a 500 Hz crossover in the inner track to try and compensate for the lower fidelity and high-frequency distortion on the inner track.

Each groove needed its own monophonic needle and cartridge on its own branch of the tonearm, and each needle was connected to a separate amplifier and speaker. This setup was intended to demonstrate Cook's cutter heads at a New York audio fair. It was not intended to promote the binaural process, but soon afterward, the demand for such recordings and the equipment to play them grew, and Cook's company, Cook Records, began to produce such records commercially. Cook recorded a vast array of sounds, ranging from railroad sounds to thunderstorms. By 1953, Cook had a catalog of about 25 stereo records for sale to audiophiles.[29]

Magnetic tape recording

[edit]The first stereo recordings using magnetic tape were made in Germany in the early 1940s using Magnetophon recorders. Around 300 recordings were made of various symphonies, most of which were seized by the Red Army at the end of World War II. The recordings were of relatively high fidelity, thanks to the discovery of AC bias. A 1944 recording of Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 8 directed by Herbert von Karajan and the Orchester der Berliner Staatsoper and a 1944 or 1945 recording of Walter Gieseking playing Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5 (with anti-aircraft fire audible in the background)[30] are the only recordings still known to exist.[citation needed]

In the US, stereo magnetic tape recording was demonstrated on standard 1/4-inch tape for the first time in 1952, using two sets of recording and playback heads, upside-down and offset from one another.[31] A year later, Remington Records began recording a number of its sessions in stereo, including performances by Thor Johnson and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra.[32]

Later in 1952, more experimental stereo recordings were conducted with Leopold Stokowski and a group of New York studio musicians at RCA Victor Studios in New York City. In February 1954, the label also recorded a performance of Berlioz' masterpiece The Damnation of Faust by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Charles Munch, the success of which led to the practice of regularly recording sessions in stereo.[citation needed]

Shortly afterward, RCA Victor recorded the last two NBC Blue Network broadcast concerts by famed conductor Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra, on stereophonic magnetic tape, however, they were never officially released, though they have long been available on pirated LPs and CDs.[citation needed] In the UK, Decca Records began recording sessions in stereo in mid-1954, and by that time even smaller labels in the US such as Concertapes, Bel Canto and Westminster along with major labels such as RCA Victor began releasing stereophonic recordings on two-track prerecorded reel-to-reel magnetic tape, priced at twice or three times the cost of monaural recordings, which retailed for around $2.95 to $3.95 apiece for a standard monaural LP. Even two-track monaural tape which had to be flipped over halfway through and carried exactly the same information as the monaural LP – but without the crackles and pops – were being sold for $6.95.[33]

Stereophonic sound came to at least a select few living rooms of the mid-1950s.[34]

Stereo on disc

[edit]

In November 1957, the small Audio Fidelity Records label released the first mass-produced stereophonic disc. Sidney Frey, founder and president, had Westrex engineers, owners of one of the two rival stereo disk-cutting systems, cut a disk for release before any of the major record labels could do so.[35][36] Side 1 featured the Dukes of Dixieland, and Side 2 featured railroad and other sound effects designed to engage and envelop the listener. This demonstration disc was introduced to the public on December 13, 1957, at the Times Auditorium in New York City.[37] Only 500 copies of this initial demonstration record were pressed and three days later, Frey advertised in Billboard Magazine that he would send a free copy to anyone in the industry who wrote to him on company letterhead.[38][39] The move generated such a great deal of publicity[40] that early stereo phonograph dealers were forced to demonstrate on Audio Fidelity Records.

Also in December 1957, Bel Canto Records, another small label, produced its own stereophonic demonstration disc on multicolored vinyl[41] so that stereo dealers would have more than one choice for demonstration. With the supplied special turntables featuring a clear platter lighted from underneath to show off the color as well as the sound, the stunt worked even better for Bel Canto, whose roster of jazz, easy listening and lounge music, pressed onto their trademark Caribbean-blue vinyl sold well throughout 1958 and early into 1959.

When Audio Fidelity released its stereophonic demonstration disc, there was no affordable magnetic cartridge on the market capable of playing it. After the release of other demonstration discs and the respective libraries from which they were culled, the other spur to the popularity of stereo discs was the reduction in price of a stereo cartridge, for playing the discs–from $250 to $29.95 in June 1958.[42] The first four mass-produced stereophonic discs available to the buying public were released in March 1958 – Johnny Puleo and his Harmonica Gang Volume 1 (AFSD 5830), Railroad – Sounds of a Vanishing Era (AFSD 5843), Lionel – Lionel Hampton and his Orchestra (AFSD 5849) and Marching Along with the Dukes of Dixieland Volume 3 (AFSD 5851). By the end of March, the company had four more stereo LPs available, interspersed with several Bel Canto releases.[43]

Although both monaural as well as stereo LP records were manufactured for the first ten years of stereo on disc, the major record labels issued their last monaural albums in 1968, relegating the format to 45 RPM singles, flexidiscs and radio promotional materials which continued until 1975.[44][45][46] In a sense, it was a sudden changeover: to discourage mono sales, in 1966 the record labels had generally eliminated the $1-cheaper pricing for mono LP. Also, even in 1967 stereo LP sales accounted for only 38.6% of the industry total, far outweighed by mono.[47]

Broadcasting

[edit]Radio

[edit]Early experimentation

[edit]The earliest approach to stereo (then commonly called binaural) radio used two separate transmissions to individually send the left and right audio channels, which required listeners to operate two receivers in order to hear the stereo effect. In 1924 Franklin M. Doolittle was issued US patent 1,513,973[48] for the use of dual radio transmissions to create stereo reception. That same year Doolittle began a year-long series of test transmissions, using his medium wave broadcasting station, WPAJ in New Haven, Connecticut, which was temporarily authorized to concurrently operate a second transmitter. Left and right audio was distributed to the two transmitters by dual microphones, placed about 7 inches (18 cm) apart in order to mimic the distance between a person's ears.[49][50] Doolittle ended the experiments primarily because a lack of available frequencies on the congested AM broadcast band which meant that it was not practical for stations to occupy two frequencies,[51] plus it was cumbersome and expensive for listeners to operate two radio receivers.[51]

In 1925 it was reported that additional experimental stereo transmissions had been conducted in Berlin, again with two mediumwave transmissions.[52] In December of that year the BBC's long wave station, 5XX in Daventry, Northamptonshire, participated in the first British stereo broadcast – a concert from Manchester, conducted by Sir Hamilton Harty – with 5XX transmitting nationally the right channel, and local BBC stations broadcasting the left channel on mediumwave.[53] The BBC repeated the experiment in 1926, using 2LO in London and 5XX at Daventry. On June 12, 1946, a similar experimental broadcast using two stations was conducted in Holland, which was mistakenly thought to be the first in Europe and possibly the world.[54]

1952 saw a renewed interest in the United States in stereo broadcasting, still using two stations for the two channels, in part in reaction to the development of two-channel tape recordings. The Federal Communications Commission's (FCC) duopoly rule limited station owners to one AM station per market. But many station owners now had access to a co-owned FM station, and most of these tests paired AM and FM stations. On May 18 KOMO and KOMO-FM in Seattle, Washington conducted an experimental broadcast,[55] and four days later Chicago AM radio station WGN and its sister FM station, WGNB, collaborated on an hourlong stereophonic demonstration.[56] On October 23, 1952, two Washington, D.C. FM stations, WGMS-FM and WASH, conducted their own demonstration.[57] Later that month New York City's WQXR, paired with WQXR-FM, initiated its first stereophonic broadcast, which was relayed to WDRC[note 2] and WDRC-FM.[58][59] By 1954, WQXR was broadcasting all of its live musical programs in stereophonic sound, using its AM and FM stations for the two audio channels.[60] Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute began a weekly series of live stereophonic broadcasts in November 1952 using two AM stations, WHAZ in conjunction with a very low-powered local carrier current station, which meant the stereo listening area did not extend beyond the college campus.[61]

The revived dual transmitter tests were of limited success, because they still required two receivers, and with AM-FM pairings the sound quality of the AM transmissions was generally significantly inferior to the FM signals.

FM standards

[edit]

The Zenith-GE pilot-tone stereo system is used throughout the world by FM broadcasting stations.

It was eventually determined that the bandwidth assigned to individual FM stations was sufficient to support stereo transmissions from a single transmitter. In the United States, the FCC oversaw comparison tests, conducted by the National Stereophonic Radio Committee, of six proposed FM standards. These tests were conducted by KDKA-FM in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania during July and August 1960.[62] In April 1961 the FCC adopted stereophonic FM technical standards, largely based on a Zenith-General Electric proposal, with licensed regular stereophonic FM radio broadcasting set to begin in the United States on June 1, 1961.[63] At midnight in their respective time zones on June 1, General Electric's WGFM in Schenectady, New York, Zenith's WEFM in Chicago, and KMLA in Los Angeles became the first three stations to begin broadcasting using the new stereo standards.[64]

Following experimental FM stereo transmissions in the London area in 1958 and regular Saturday morning demonstration transmissions using TV sound and medium wave (AM) radio to provide the two channels, the first regular BBC transmissions using an FM stereo signal began on the BBC Third Programme network on August 28, 1962.[65]

In Sweden, Televerket invented a different stereo broadcasting system called the Compander System. It had a high level of channel separation and could even be used to broadcast two separate mono signals – for example for language studies (with two languages at the same time). But tuners and receivers with the pilot-tone system were sold so people in southern Sweden could listen to, for example, Danish radio. At last Sweden (the Televerket) decided to start broadcasting in stereo according to the pilot-tone system in 1977.

AM standards

[edit]Very few stations transmit in AM stereo. This is in part due to the limited audio quality afforded by the format, and the scarcity of AM stereo receivers. Various modulation schemes are used for AM stereo, of which the best-known is Motorola's C-QUAM, the official method for most countries in the world where AM stereo transmission is available. There has been experimental AM adoption of digital HD Radio, which also allows the transmission of stereo sound on AM stations;[66][67] HD Radio's lack of compatibility with C-QUAM along with other interference issues has hindered HD Radio's use on the AM dial.

Television

[edit]A December 11, 1952, closed-circuit television performance of Carmen from the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City to 31 theaters across the United States, included a stereophonic sound system developed by RCA.[68] The first several shows of the 1958–59 season of The Plymouth Show (also called The Lawrence Welk Show) on the ABC (America) network were broadcast with stereophonic sound in 75 media markets, with one audio channel broadcast via television and the other over the ABC radio network.[69][70] By the same method, NBC Television and the NBC Radio Network offered stereo sound for two three-minute segments of The George Gobel Show on October 21, 1958.[71] On January 30, 1959, ABC's Walt Disney Presents made a stereo broadcast of The Peter Tchaikovsky Story – including scenes from Disney's latest animated feature, Sleeping Beauty – by using ABC-affiliated AM and FM stations for the left and right audio channels.[72]

After the advent of FM stereo broadcasts in 1962, a small number of music-oriented TV shows were broadcast with stereo sound using a process called simulcasting, in which the audio portion of the show was carried over a local FM stereo station.[73] In the 1960s and 1970s, these shows were usually manually synchronized with a reel-to-reel tape recording mailed to the FM station (unless the concert or music originated locally). In the 1980s, satellite delivery of both television and radio programs made this fairly tedious process of synchronization unnecessary. One of the last of these simulcast programs was Friday Night Videos on NBC.

The BBC made extensive use of simulcasting between 1974 and around 1990. The first such transmission was in 1974 when the BBC broadcast a recording of Van Morrison's London Rainbow Concert simultaneously on BBC2 TV and Radio 2. After that it was used for many other music programs, live and recorded, including the annual BBC Promenade concerts and the Eurovision Song Contest. The advent of NICAM stereo sound with TV rendered this unnecessary.

Cable TV systems used simulcasting to deliver stereo programs for many years. One of the first stereo cable stations was The Movie Channel, though the most popular cable TV station that drove up the usage of stereo simulcasting was MTV.

Japanese television began stereo broadcasts in 1978,[74] and regular transmissions with stereo sound came in 1982.[75] By 1984, about 12% of the programming, or about 14 or 15 hours per station per week were broadcast in stereo. West Germany's second television network, ZDF, began offering stereo programs in 1984.[74]

In 1979, The New York Times reported, "What has prompted the [television] industry to embark on establishing high-fidelity [sound] standards now, according to engineering executives involved in the project, is chiefly the rapid march of the new television technologies, especially those that are challenging broadcast television, such as the video disk."[76]

For analog TV (PAL and NTSC), various modulation schemes are used in different parts of the world to broadcast more than one sound channel. These are sometimes used to provide two mono sound channels that are in different languages, rather than stereo. Multichannel television sound is used mainly in the Americas. NICAM is widely used in Europe, except in Germany, where Zweikanalton is used. The EIAJ FM/FM subcarrier system is used in Japan. For digital TV, MP2 audio streams are widely used within MPEG-2 program streams. Dolby Digital is the audio standard used for digital TV in North America, with the capability for anywhere between 1 and 6 discrete channels.

Multichannel Television Sound (MTS) is the method of encoding three additional audio channels into an NTSC-format audio carrier. It was adopted by the FCC as the United States standard for stereo television transmission in 1984. Sporadic network transmission of stereo audio began on NBC on July 26, 1984, with The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson – although at the time, only the network's New York City flagship station, WNBC-TV, had stereo broadcast capability.[77] Regular stereo transmission of programs began in 1985. ABC and CBS followed suit in 1986 and 1987.

Recording methods

[edit]A-B technique: time-of-arrival stereophony

[edit]

The A-B technique uses two omnidirectional microphones some distance apart and equidistant from the source. The technique captures time-of-arrival stereo information as well as some level difference information – especially if employed in close proximity to the source. At a distance of about 60 cm (24 in) between microphones, the time-of-arrival difference for a signal reaching the first microphone and then the other one from the side is approximately 1.75 ms. If you increase the distance between the microphones, you effectively decrease the pickup angle. At a 70 cm (28 in) distance, it is approximately equivalent to the pickup angle of the near-coincident ORTF setup.[citation needed]

This technique can produce phase issues when the stereo signal is mixed to mono.

X-Y technique: intensity stereophony

[edit]

Here, two directional microphones are colocated, typically pointing at an angle between 90° and 135° with respect to each other.[78] The stereo effect is achieved through differences in sound pressure level between two microphones. Due to the lack of differences in time-of-arrival/phase ambiguities, the sonic characteristic of X-Y recordings has less sense of space and depth when compared to recordings employing an A-B setup. When two figure-eight microphones are used, facing ±45° with respect to the sound source, the X-Y setup is called a Blumlein pair.

M/S technique: mid/side stereophony

[edit]

This coincident technique employs a bidirectional microphone facing sideways and another microphone at an angle of 90°, facing the sound source. The second microphone is generally a variety of cardioid, although Alan Blumlein described the usage of an omnidirectional transducer in his original patent.

The left and right channels are produced through a simple matrix: left = mid + side; right = mid − side (using a polarity-reversed version of the side signal). This configuration produces a completely mono-compatible signal and, if the mid and side signals are recorded (rather than the matrixed left and right), the stereo width can be manipulated after the recording has taken place by adjusting the magnitude of the side signal (a greater amplitude giving a greater perceived stereo field which can be made to exceed the distance between loudspeakers). This makes it especially useful for film-based projects.

If the mid/side technique is incorporated into a self-contained stereo microphone assembly that outputs only the final left and right stereo pair signals, the original mid and side signals may be recovered permitting the above-mentioned manipulation. The mid signal is recovered by adding the left and right signals (the in phase and antiphase side signals cancel - giving a true mono signal in the process). The side signal is recovered by subtracting the right signal from the left (the mid signal is present in both channels and therefore cancels leaving the side).

Near-coincident technique: mixed stereophony

[edit]

These techniques combine the principles of both A-B and X-Y (coincident pair) techniques. For example, the ORTF stereo technique of the Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française (Radio France) calls for a pair of cardioid microphones placed 17 cm apart at a total angle between microphones of 110°, which results in a stereophonic pickup angle of 96° (Stereo Recording Angle, or SRA).[79] In the NOS stereo technique of the Nederlandse Omroep Stichting (Dutch Broadcasting Organization), the total angle between microphones is 90° and the distance is 30 cm, thus capturing time-of-arrival stereo information as well as level information. It is noteworthy that all spaced microphone arrays and all near-coincident techniques use a spacing of at least 17 cm or more. 17 cm roughly equals the human ear distance and therefore provides the same interaural time difference (ITD) or more, depending on the spacing between microphones. Although the recorded signals are generally intended for playback over stereo loudspeakers, reproduction over headphones can provide remarkably good results, depending on the microphone arrangement.

Pseudo-stereo

[edit]

| 1. | A is a square wave and B is one thrice the frequency. |

| 2. | Different amounts of A and B are mixed into the left (L) and right (R) channels. |

| 3. | To widen the stereo effect, a fraction of the opposing channel is subtracted from each channel. |

| 4. | Normalized results show the signals A and B partly separated. |

In the course of restoration or remastering of monophonic records, various techniques of pseudo-stereo, quasi-stereo, or rechanneled stereo have been used to create the impression that the sound was originally recorded in stereo. These techniques first involved hardware methods (see Duophonic) or, more recently, a combination of hardware and software. Multitrack Studio, from Bremmers Audio Design (The Netherlands),[81] uses special filters to achieve a pseudo-stereo effect: the shelve filter directs low frequencies to the left channel and high frequencies to the right channel, and the comb filter adds a small delay in signal timing between the two channels, a delay barely noticeable by ear,[note 3] but contributing to an effect of widening original flattiness of mono recording.[82][83]

The special pseudo-stereo circuit – invented by Kishii and Noro, from Japan – was patented in the United States in 2003,[84] with already previously issued patents for similar devices.[85] Artificial stereo techniques have been used to improve the listening experience of monophonic recordings or to make them more "saleable" in today's market, where people expect stereo. Some critics have expressed concern about the use of these methods.[86]

Binaural recording

[edit]Engineers make a technical distinction between "binaural" and "stereophonic" recording. Of these, binaural recording is analogous to stereoscopic photography. In binaural recording, a pair of microphones is put inside a model of a human head that includes external ears and ear canals; each microphone is where the eardrum would be. The recording is then played back through headphones, so that each channel is presented independently, without mixing or crosstalk. Thus, each of the listener's eardrums is driven with a replica of the auditory signal it would have experienced at the recording location. The result is an accurate duplication of the auditory spatiality that would have been experienced by the listener had he or she been in the same place as the model head. Because of the inconvenience of wearing headphones, true binaural recordings have remained laboratory and audiophile curiosities. However, "loudspeaker-binaural" listening is possible with Ambiophonics.

Numerous early two-track-stereo reel-to-reel tapes as well as several experimental stereo disc formats of the early 1950s branded themselves as binaural, however they were merely different incarnations of the above-described stereo or two-track mono recording methods (lead vocal or instrument isolated on one channel and orchestra on the other sans lead.)

Playback

[edit]Stereophonic sound attempts to create an illusion of location for various sound sources (voices, instruments, etc.) within the original recording. The recording engineer's goal is usually to create a stereo "image" with localization information. When a stereophonic recording is heard through loudspeaker systems (rather than headphones), each ear, of course, hears sound from both speakers. The audio engineer may, and often does, use more than two microphones (sometimes many more) and may mix them down to two tracks in ways that exaggerate the separation of the instruments, in order to compensate for the mixture that occurs when listening via speakers.

Descriptions of stereophonic sound tend to stress the ability to localize the position of each instrument in space, but this would only be true in a carefully engineered and installed system, where speaker placement and room acoustics are taken into account. In reality, many playback systems, such as all-in-one boombox units and the like, are incapable of recreating a realistic stereo image. Originally, in the late 1950s and 1960s, stereophonic sound was marketed as seeming "richer" or "fuller-sounding" than monophonic sound, but these sorts of claims were and are highly subjective, and again, dependent on the equipment used to reproduce the sound. In fact, poorly recorded or reproduced stereophonic sound can sound far worse than well-done monophonic sound. Nevertheless, many record companies released stereo "demonstration" records to help promote stereo. These records often included instructions for setting up a stereo system, 'balancing' the speakers, and a variety of ambient recordings to show off the stereo effect.[87] When playing back stereo recordings, the best results are obtained by using two identical speakers, in front of and equidistant from the listener, with the listener located on a center line between the two speakers. In effect, an equilateral triangle is formed, with the angle between the two speakers around 60 degrees as seen from the listener's point of view. Many higher quality multichannel (two-channel and beyond) speaker systems, then and now, include detailed instructions specifying the ideal angles and distances between the speakers and the listening position to maximize the effect based on, often extensive, testing of the particular system's design.

Vinyl records

[edit]Although Decca recorded Ernest Ansermet's May 1954 conducting of Antar in stereo, it took four years for the first stereo LPs to be sold.[88] In 1958, the first group of mass-produced stereo two-channel vinyl records was issued, by Audio Fidelity in the US and Pye in Britain, using the Westrex "45/45" single-groove system. Whereas the stylus moves horizontally when reproducing a monophonic disk recording, on stereo records, the stylus moves vertically as well as horizontally. One could envision a system in which the left channel was recorded laterally, as on a monophonic recording, with the right channel information recorded with a "hill and dale" vertical motion; such systems were proposed but not adopted due to their incompatibility with existing phono pickup designs (see below).

In the Westrex system, each channel drives the cutting head at a 45-degree angle to the vertical. During playback, the combined signal is sensed by a left-channel coil mounted diagonally opposite the inner side of the groove and a right-channel coil mounted diagonally opposite the outer side of the groove.[89] The Westrex system provided for the polarity of one channel to be inverted: this way large groove displacement would occur in the horizontal plane and not in the vertical one. The latter would require large up-and-down excursions and would encourage cartridge skipping during loud passages.

The combined stylus motion is, in terms of the vector, the sum and difference of the two stereo channels. Effectively, all horizontal stylus motion conveys the L+R sum signal, and vertical stylus motion carries the L−R difference signal. The advantages of the 45/45 system are that it has greater compatibility with monophonic recording and playback systems.

Even though a monophonic cartridge will technically reproduce an equal blend of the left and right channels, instead of reproducing only one channel, this was not recommended in the early days of stereo due to the larger stylus (1.0 mil or 25 micrometres vs. 0.7 mils or 18 micrometres for stereo) coupled with the lack of vertical compliance of the mono cartridges available in the first ten years of stereo. These factors would result in the stylus 'digging into' the stereo vinyl and carving up the stereo portion of the groove, destroying it for subsequent playback on stereo cartridges. This is why one often notices the banner "PLAY ONLY WITH STEREO CARTRIDGE AND STYLUS" on stereo vinyl issued between 1958 and 1964.

Conversely, and with the benefit of no damage to any type of disc even from the beginning, a stereo cartridge reproduces the lateral grooves of monophonic recording equally through both channels, rather than through one channel. Also, it gives a more balanced sound, because the two channels have equal fidelity as opposed to providing one higher-fidelity laterally recorded channel and one lower-fidelity vertically recorded channel. Overall, this approach may give higher fidelity, because the difference signal is usually of low power, and is thus less affected by the intrinsic distortion of hill and dale-style recording.

Additionally, surface noise tends to be picked up in a greater capacity in the vertical channel; therefore, a mono record played on a stereo system can be in worse shape than the same record in stereo and still be enjoyable. (See Gramophone record for more on lateral and vertical recording.)

Although this system was conceived by Alan Blumlein of EMI in 1931 and was patented in the UK the same year, it was not reduced to practice by the inventor as was a requirement for patenting in the US and elsewhere at that time. (Blumlein was killed in a plane crash while testing radar equipment during WW-II, and he, therefore, never reduced the system to actual practice through both a recording and a reproducing means.) EMI cut the first stereo test discs using this system in 1933, but it was not applied commercially until a quarter of a century later, and by another company entirely (Westrex division of Litton Industries Inc, as the successor to Western Electric Company), and dubbed StereoDisk. Stereo sound provides a more natural listening experience, since the spatial location of the source of a sound is (at least in part) reproduced.

In the 1960s, it was common practice to generate stereo versions of music from monophonic master tapes, which were normally marked "electronically reprocessed" or "electronically enhanced" stereo on track listings. These were generated by a variety of processing techniques to try to separate out various elements; this left noticeable and unsatisfactory artifacts in the sound, typically sounding "phasey". However, as multichannel recording became increasingly available, it has become progressively easier to master or remaster more plausible stereo recordings out of the archived multitrack master tapes.

Compact disc

[edit]The Red Book CD specification includes two channels by default, and so a mono recording on CD either has one empty channel, or else the same signal on both channels.

Common usage

[edit]

In common usage, a stereo is a two-channel sound reproduction system, and a stereo recording is a two-channel recording. This is cause for much confusion, since five (or more)-channel home theater systems are not popularly described as stereo, but instead as surround.[clarification needed (see talk)]

Most multichannel recordings are stereo recordings only in the sense that they are stereo "mixes" consisting of a collection of mono and/or true stereo recordings. Modern popular music, in particular, is usually recorded using close miking techniques, which artificially separate signals into several tracks. The individual tracks (of which there may be hundreds) are then "mixed down" into a two-channel recording. The audio engineers determine where each track will be placed in the stereo "image", by using various techniques that may vary from very simple (such as "left-right" panning controls) to more sophisticated and extensively based on psychoacoustic research (such as channel equalization, mid-side processing, and the use of delay to exploit the precedence effect). The end product using this process often bears little or no resemblance to the actual physical and spatial relationship of the musicians at the time of the original performance; indeed, it is not uncommon for different tracks of the same song to be recorded at different times (and even in different studios) and then mixed into a final two-channel recording for commercial release.

Classical music recordings are a notable exception. They are more likely to be recorded without having tracks dubbed in later as in pop recordings, so that the actual physical and spatial relationship of the musicians at the time of the original performance can be preserved on the recording.[citation needed]

Balance

[edit]Balance can mean the amount of signal from each channel reproduced in a stereo audio recording. Typically, a balance control in its center position will have 0 dB of gain for both channels and will attenuate one channel as the control is turned, leaving the other channel at 0 dB.[90]

See also

[edit]- 3D audio effect

- 5.1 surround sound

- Acoustic location

- Ambisonics – generalized MS-Stereo to three dimensions

- Joint encoding – Joining of several channels of similar information to allow more efficient encoding

- Sound localization – Biological sound detection process

- Stereoscopy – Technique for creating or enhancing the impression of depth in an image

- Subwoofer – Loudspeaker for low-pitched audio frequencies

- Summing localization

- Sweet spot (acoustics) – Ideal position for listening to speakers

- Wave field synthesis – the physical reconstruction of the spatial sonic field

Notes

[edit]- ^ The term "binaural" that Cook used should not be confused with the modern use of the word, where "binaural" is an inner-ear recording using small microphones placed in the ear. Cook used conventional microphones, but used the same word, "binaural", that Alan Blumlein had used for his experimental stereo records almost 20 years earlier.

- ^ Franklin Doolittle's former WPAJ, now located in Hartford, Connecticut

- ^ The comb filter allows range of manipulation between 0 and 100 milliseconds.

References

[edit]- ^ στερεός Archived August 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "φωνή". A Greek-English Lexicon on Perseus Digital Library. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021.

- ^ Lipschitz, Stanley (November 9, 1986). "Stereo Microphone Techniques: Are the Purists Wrong?" (PDF). Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 34 (9): 716–743.

- ^ "The Telephone at the Paris Opera" Archived February 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Scientific American, December 31, 1881, pages 422–23.

- ^ "Court Circular", The Times (London), November 6, 1895, p. 7. "Post Office Electrical Engineers. The Electrophone Service", The Times (London), January 15, 1913, p. 24. "Wired Wireless", The Times (London), June 22, 1925, p. 8.

- ^ Elgar Remastered, Somm CD 261, and Accidental Stereo, Pristine Classical CD PASC422).

- ^ a b "Early stereo recordings restored". BBC. August 1, 2008. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

Blumlein lodged the patent for 'binaural sound', in 1931, in a paper which patented stereo records, stereo films and also surround sound. He and his colleagues then made a series of experimental recordings and films to demonstrate the technology, and see if there was any commercial interest from the fledgling film and audio industry.

- ^ GB patent 394325, Alan Dower Blumlein, "Improvements in and relating to Sound-transmission, Sound-recording and Sound-reproducing Systems.", issued June 14, 1933, assigned to Alan Dower Blumlein and Musical Industries, Limited

- ^ Robert Alexander (2013). "The Inventor of Stereo: The Life and Works of Alan Dower Blumlein". p. 83. CRC Press,

- ^ Fox, Barry (December 24–31, 1981). "A hundred years of stereo: fifty of hi-fi". New Scientist. p. 911. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ Stokowski, Harvey Fletcher, and the Bell Labs Experimental Recordings Archived November 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, stokowski.org, accessed March 1, 2012.

- ^ B.B. Bauer, "Some Techniques Toward Better Stereophonic Perspective", IEEE Transactions on Audio, May–June 1963, p. 89.

- ^ "Radio Adds Third Dimension", Popular Science, Jan. 1953, p. 106.

- ^ "Sound Waves 'Rock' Carnegie Hall as 'Enhanced Music' is Played", The New York Times, April 10, 1940, p. 25.

- ^ "New Sound Effects Achieved in Film". The New York Times. October 12, 1937. p. 27.

- ^ Nelson B. Bell, "Rapid Strides are Being Made in Development of Sound Track", The Washington Post, April 11, 1937, p. TR1.

- ^ Motion Picture Herald, September 11, 1937, p. 40.

- ^ T. Holman, Surround Sound: Up and Running, Second Edition, Elsevier, Focal Press (2008), 240 pp.

- ^ Andrew R. Boone, "Mickey Mouse Goes Classical", Popular Science, January 1941, p. 65.

- ^ "Fantasound" by W.E, Garity and J.N.A.Hawkins. Journal of the SMPE Vol 37 August 1941

- ^ "The CinemaScope Wing 5". Widescreen Museum. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Romeo and Juliet". October 8, 1968. Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2017 – via IMDb.

- ^ "West Side Story". December 23, 1961. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2017 – via IMDb.

- ^ "My Fair Lady". December 25, 1964. Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved January 1, 2017 – via IMDb.

- ^ "Camelot". October 25, 1967. Archived from the original on December 16, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2017 – via IMDb.

- ^ "Ben-Hur". January 29, 1960. Archived from the original on April 12, 2007. Retrieved January 1, 2017 – via IMDb.

- ^ "Cleopatra". July 31, 1963. Archived from the original on December 3, 2003. Retrieved January 1, 2017 – via IMDb.

- ^ "The Graduate". December 22, 1967. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2017 – via IMDb.

- ^ "Commercial Binaural Sound Not Far Off", Billboard, October 24, 1953, p. 15.

- ^ "Waler Gieseking plays Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C, Op. 15 & Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat, Op. 73, "Emperor"". Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "Adventures in Sound", Popular Mechanics, September 1952, p. 216.

- ^ "Thor Johnson (1913-1975)". Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ Tape Trade Group to Fix Standards. Billboard. July 10, 1954. p. 34.

- ^ "Hi-Fi: Two-Channel Commotion", The New York Times, November 17, 1957, p. XX1.

- ^ "Jazzbeat October 26, 2007". Jazzology.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Harry R. Porter history". Thedukesofdixieland.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2004. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Mass Produced Stereo Disc is Demonstrated," Billboard, December 16, 1957, p. 27.

- ^ Audio Fidelity advertisement, Billboard, December 16, 1957, p. 33.

- ^ "Mass Produced Stereo Disk is Demonstrated", Billboard, December 16, 1957, p. 27.

- ^ Alfred R. Zipser, "Stereophonic Sound Waiting for a Boom", The New York Times, August 24, 1958, p. F1.

- ^ "Bel Canto Stereophonic Demonstration Record". Discogs. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "Audio Fidelity Bombshell Had Industry Agog", Billboard, December 22, 1962, p. 36.

- ^ "CBS Discloses Stereo Step," Billboard, March 31, 1958, p. 9.

- ^ Sylvan Fox, "Disks Today: New Sounds and Technology Spin Long-Playing Record of Prosperity", The New York Times, August 28, 1967, p. 35.

- ^ RCA Victor Red Seal Labelography (1950–1967).

- ^ "Mfrs. Strangle Monaural Archived August 6, 2024, at the Wayback Machine", Billboard, January 6, 1968, p. 1.

- ^ "Record Preview." High Fidelity, 17:9 (September 1967), 64.

- ^ US 1513973 "Radiotelephony". Patent issued November 4, 1924, to Franklin M. Doolittle for application filed February 21, 1924.

- ^ "Binaural Broadcasting" Archived August 6, 2024, at the Wayback Machine by F. M. Doolittle, Electrical World, April 25, 1925, pages 867–870. The transmitting wavelengths of 268 and 227 meters correspond to frequencies of 1120 (WPAJ's normal frequency) and 1320 kHz respectively.

- ^ "Stereoscopic or Binaural Broadcasting in Experimental Use at New Haven" Archived January 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine (correspondence from Franklin M. Doolittle), Cincinnati (Ohio) Enquirer, March 22, 1925, Section 6, page 6.

- ^ a b "Binaural Broadcasting" by Franklin M. Doolittle, Broadcasting, November 3, 1952, page 97.

- ^ "Radio Stereophony" Archived June 25, 2024, at the Wayback Machine by Ludwig Kapeller, Radio News, October 1925, pages 416, 544–546. The transmitting wavelengths of 430 and 505 meters correspond to approximately 698 and 594 kHz respectively.

- ^ "Stereoscopic Broadcasting" Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine by Captain H. J. Round, Wireless, September 26, 1925, pages 55–56.

- ^ "Dutch Regard 'Stereophonic Broadcasting' Experiment as Significant for Future", Archived March 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Commerce Weekly, August 24, 1946, page 16.

- ^ "KOMO Binaural" Broadcasting, June 2, 1952, page 46.

- ^ "Binaural Feature at Parts Show", Broadcasting, May 26, 1952, page 73.

- ^ "2 Stations, 2 Mikes, 2 Radios Give Broadcast Realistic Sound" Archived March 16, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, October 24, 1952, page A-24.

- ^ "Two WDRC Stations Will Present 'Binaural' System Demonstrations", Hartford Courant, October 29, 1952, page 26.

- ^ "WDRC" (advertisement), Broadcasting, December 8, 1952, page 9.

- ^ Multiple sources:

- "News of TV and Radio", The New York Times, October 26, 1952, p. X-11.

- "Binaural Devices", The New York Times, March 21, 1954, p. XX-9.

- ^ "Binaural Music on the Campus", Archived August 6, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, Popular Science, April 1953, p. 20.

- ^ "Commentary: Dick Burden on FM Stereo Revisited". Radio World. February 1, 2007. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- ^ "Finally, FCC Okays Stereo", Broadcasting, April 24, 1961, pages 65–66.

- ^ "Three fms meet date for multiplex stereo", Broadcasting, June 5, 1961, page 58.

- ^ Start of experimental stereo broadcasting 28 August 1962 Archived November 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, BBC

- ^ "WWFD 820 AM becomes first all-digital AM station". Radio-Online. July 16, 2018.

- ^ "FCC authorizes all-digital AM radio" (PDF) (Press release). Federal Communications Commission. October 27, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "Theater to Have Special Sound System for TV", Los Angeles Times, December 5, 1952, p. B-8.

- ^ "A Television First! Welk Goes Stereophonic" (advertisement), Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1958, p. A-7.

- ^ "Dealers: Lawrence Welk Leads in Stereo!" (advertisement), Billboard, October 13, 1958, p. 23.

- ^ "Expect Giant TV Stereo Audience", Archived August 6, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, Billboard, October 20, 1958, p. 12.

- ^ Sedman, David. "The Legacy of Broadcast Stereo Sound". Journal of Sonic Studies. October 2012. Archived October 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ For example: Jack Gould, "TV: Happy Marriage With FM Stereo", The New York Times, December 26, 1967, p. 67.

- ^ a b "/"Japan's Stereo TV System", Archived July 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, June 16, 1984.

- ^ "1982". Chronomedia. Terra Media. Archived from the original on September 22, 2009.

- ^ Les Brown, "Hi-fi Stereo TV Coming in 2 to 4 Years", The New York Times, October 25, 1979, p. C-18.

- ^ Peter W. Kaplan, "TV Notes", New York Times, July 28, 1984, sec. 1, p. 46.

- ^ ""The Stereophonic Zoom" by Michael Williams" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 31, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Eberhard Sengpiel. "Forum für Mikrofonaufnahme und Tonstudiotechnik. Eberhard Sengpiel". Sengpielaudio.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Rick Snoman, Dance Music Manual – Tools, Toys, and Techniques, October 15, 2013, ISBN 9781135964092

- ^ "Pseudo-Stereo". Multitrackstudio.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Hyperprism-DX Stereo Processes—Quasi stereo". March 31, 2008. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008.

- ^ A Review and an Extension of Pseudo-Stereo... Archived December 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pseudo-stereo circuit—Patent 6636608". Freepatentsonline.com. October 21, 2003. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Psycho acoustic pseudo-stereo fold system". Patentstorm.us. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Pseudo Stereo, Time magazine, Jan. 20, 1961". Time. January 20, 1961. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Borgerson, Janet; Schroeder, Jonathan (December 12, 2018). "How stereo was first sold to a skeptical public". The Conversation. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Grammy pulse – Volumes 2–3 – Page vi National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences (U.S.) – 1984 "After all, stereo sound was developed in 1931, but it took until 1958 for the first stereo LPs to be sold. Keeping in mind corporate and bureaucratic red tape, we could easily be in for a long haul before stereo TV is as natural as having two ears."

- ^ "Stereo disc recording". Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2006.

- ^ "AES Professional Audio Reference Home". Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

External links

[edit] Media related to Stereophonic sound at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Stereophonic sound at Wikimedia Commons