Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Italian Brazilians

View on Wikipedia

Italian Brazilians (Italian: italo-brasiliani, Portuguese: ítalo-brasileiros) are Brazilians of full or partial Italian descent,[6] whose ancestors were Italians who emigrated to Brazil during the Italian diaspora, or more recent Italian-born people who've settled in Brazil. Italian Brazilians are the largest number of people with full or partial Italian ancestry outside Italy, with São Paulo being the most populous city with Italian ancestry in the world.[7] Nowadays, it is possible to find millions of descendants of Italians, from the southeastern state of Minas Gerais to the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul, with the majority living in São Paulo state.[8] Small southern Brazilian towns, such as Nova Veneza, have as much as 95% of their population of Italian descent.[9]

Key Information

There are no official numbers of how many Brazilians have Italian ancestry, as the national census conducted by IBGE does not ask the ancestry of the Brazilian people. In 1940, the last census to ask ancestry, 1,260,931 Brazilians were said to be the child of an Italian father, and 1,069,862 said to be the child of an Italian mother. Italians were 285,000 and naturalized Brazilians 40,000. Therefore, Italians and their children were, at most, just over 3.8% of Brazil's population in 1940.[5]

The Embassy of Italy in Brazil, in 2013, reported the number of 32 million descendants of Italian immigrants in Brazil (about 15% of the population),[2][10] half of them in the state of São Paulo,[3] while there were around 450,000 Italian citizens in Brazil.[1] Brazilian culture has significant connections to Italian culture in terms of language, customs, and traditions. Brazil is also a strongly Italophilic country as cuisine, fashion and lifestyle has been sharply influenced by Italian immigration.

Italian immigration to Brazil

[edit]

According to the Italian government, there are 31 million Brazilians of Italian descent.[13] All figures relate to Brazilians of any Italian descent, not necessarily linked to Italian culture in any significant way. According to García,[14] the number of Brazilians with actual links to Italian identity and culture would be around 3.5 to 4.5 million people. Scholar Luigi Favero, in a book on Italian emigration between 1876 and 1976, pinpointed that Italians were present in Brasil since the Renaissance: Genoese sailors and merchants were among the first to settle in colonial Brazil since the first half of the 16th century,[15] and so, because of the many descendants of Italians who emigrated there from Columbus' times until 1860, the number of Brazilians with Italian roots should be increased to 35 million.[16]

Although they were victims of some prejudice in the first decades and in spite of the persecution during World War II, Brazilians of Italian descent managed to integrate and assimilate seamlessly into the Brazilian society.

Many Brazilian politicians, artists, footballers, models, and personalities are or were of Italian descent. Italian-Brazilians have been state governors, representatives, mayors and ambassadors. Four Presidents of Brazil were of Italian descent (but none of the first three directly elected to such a position): Pascoal Ranieri Mazzilli (Senate president who served as interim president), Itamar Franco (elected vice-president under Fernando Collor, whom he eventually replaced as the latter was impeached), Emílio Garrastazu Médici (third of the series of generals who presided over Brazil during the military regime, also of Basque descent) and Jair Messias Bolsonaro (elected in 2018).

Citizenship

[edit]

According to the Brazilian Constitution, anyone born in the country is a Brazilian citizen by birthright. In addition, many born in Italy have become naturalized citizens after they settled in Brazil. The Brazilian government used to prohibit multiple citizenship. However, that changed in 1994 by a new constitutional amendment.[17] After the changes, over half a million Italian-Brazilians have requested recognition of their Italian citizenship.[18]

According to Italian legislation, an individual with an Italian parent is automatically recognized as an Italian citizen. To exercise the rights and obligations of citizenship, individual must have all documents registered in Italy, which normally involves the local consulate or embassy. Some limitations are applied to the process of recognition such as the renouncement of the Italian citizenship by the individual or the parent (if before the child's birth), a second limitation is that women transferred citizenship to their children only after 1948.[19] After a constitutional reform in Italy, Italian citizens abroad may elect representatives to the Italian Chamber of Deputies and the Italian Senate. Italian citizens residing in Brazil elect representatives together with Argentina, Uruguay and other countries in South America. According to Italian Senator Edoardo Pollastri, over half-a-million Brazilians are waiting to have their Italian citizenship recognized.[18]

History

[edit]Italian crisis in late 19th century

[edit]

Italy did not become a unified national state until 1861. Before then, Italy was politically divided into several kingdoms, duchies, and other small states. The legacy of political fragmentation influenced deeply the character of the Italian migrant: "Before 1914, the typical Italian migrant was a man without a clear national identity but with strong attachments to his town or village or region of birth, to which half of all migrants returned."[20]

In the 19th century, many Italians fled the political persecutions in Italy led by the Imperial Austrian government after the failure of Italian unification movements in 1848 and 1861. Although very small in numbers, the well-educated and revolutionary group of emigrants left a deep mark where they settled.[21] In Brazil, the most famous Italian was then Líbero Badaró (died 1830). However, the mass Italian immigration tide that would only be second to the Portuguese and German migrant movements in shaping modern Brazilian culture started only after the 1848-1871 Risorgimento.

During the last quarter of the 19th century, the newly united Italy suffered an economic crisis. The more industrial northern half of Italy was plagued with high unemployment caused in part by the introduction of modern agricultural techniques, while southern Italy remained underdeveloped and almost untouched by agrarian modernization programs. Even in the North, industrialization was still in its initial stages and illiteracy remained common.[22] Thus, poverty and lack of jobs and income stimulated Northern (and Southern) Italians to emigrate. Most Italian immigrants were very poor rural workers (Italian: braccianti).[23]

Brazilian need of immigrants

[edit]

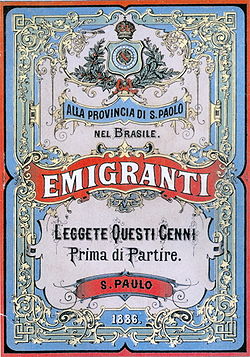

In 1850, under British pressure, Brazil finally passed a law that effectively banned transatlantic slave trade. The increased pressure of the abolitionist movement, on the other hand, made it clear that the days of slavery in Brazil were coming to an end. Slave trade was effectively suppressed, but the slave system still endured for almost four decades. Thus, Brazilian landowners claimed that such migrants were or would soon become indispensable for Brazilian agriculture. They would soon win the argument, and mass migration would begin in earnest.

An Agriculture Congress in 1878 in Rio de Janeiro discussed the lack of labor and proposed to the government the stimulation of European immigration to Brazil. Immigrants from Italy, Portugal, and Spain were considered the best ones because they were Latin-based and mainly Catholic. In particular, Italian immigrants settled mainly in the São Paulo region, where there were vast coffee plantations.[24]

At the end of the 19th century, the Brazilian government was influenced by eugenics theories.

Beginning of Italian settlement in Brazil

[edit]

The Brazilian government, with or following the Emperor's support, had created the first colonies of immigrants (colônias de imigrantes) in the early 19th century. The colonies were established in rural areas of the country, being settled by European families.

The first groups of Italians arrived in 1875, but the boom of Italian immigration in Brazil happened between 1880 and 1900, when almost one million Italians arrived.

Many Italians were naturalized Brazilian at the end of the 19th century, when the 'Great Naturalization' automatically granted citizenship to all the immigrants residing in Brazil prior to 15 November 1889 "unless they declared a desire to keep their original nationality within six months."[25]

During the end of the 19th century, denouncement of bad conditions in Brazil aggravated by the crisis in coffee plantations in São Paulo, increased in the press. Reacting to the public clamor, the Italian emigration inspector Adolfo Rossi undertook a investigation into the conditions faced by Italian emigrants on the fazendas, travelling undercover, disguised as a peasant. Rossi's report painted a dramatic picture of the semi-slavery conditions based on the testimonies collected: women raped, men whipped, discipline that "makes the fazenda look like a colony of convicts under compulsory residence," disease, failure to pay wages or delays in payment, misery.[26]

As a result the government of Italy issued in 1902 the Prinetti Decree forbidding subsidized immigration and withdrawing the permission given to Brazil for the free importation of Italians to the farms and plantations in that country.[26][27] In consequence, the number of Italian immigrants in Brazil fell drastically in the beginning of the 20th century, but the wave of Italian immigration continued until 1920.[28]

Over half of the Italian immigrants came from northern Italian regions of Veneto, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna, and from the central Italian region of Tuscany. About 30% emigrated from Veneto.[22] On the other hand, in the 20th century, southern Italians predominated in Brazil, coming from the regions of Campania, Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata and Sicily.

Prince Umberto's visit in 1924

[edit]In 1924, Umberto, Prince of Piedmont (the future King Umberto II of Italy) came to Brazil as part of a state visit to various South American countries. That was part of the political plan of the new fascist government to link Italian people living outside of Italy with their mother country and the interests of the regime. The visit was disrupted considerably by the ongoing Tenente revolts, which made it impossible for Umberto to reach Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Nevertheless, he was hosted at Bahia, where members of the Italian colony in the city were very happy and proud about his visit, thus achieving some of the visit's purposes.

Statistics

[edit]1940 Brazilian census

[edit]The Brazilian census of 1940 asked Brazilians where their fathers came from. It revealed that at that time there were 3,275,732 Brazilians who were born to an immigrant father. Of those, 1,260,931 Brazilians were born to an Italian father. Italian was the main reported paternal immigrant origin, followed by Portuguese with 735,929 children, Spanish with 340,479 and German with 159,809 children.[29]

The census also revealed that the 458,281 foreign mothers of 12 or more years who lived in Brazil had 2,852,427 children, of whom 2,657,974 were born alive. Italian women had more children than any other female immigrant community in Brazil: 1,069,862 Brazilians were born to an Italian mother, followed by 524,940 who were born to a Portuguese mother, 436,305 to a Spanish mother and 171,790 to a Japanese mother.[29] The 6,809,772 Brazilian-born mothers of 12 or more years had 38,716,508 children, of whom 35,777,402 were born alive.

| Brazilians who were born to a foreign-born father (1940 Census)[29] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main place of birth of the father | Number of children | ||||

| Italy | 1,260,931 | ||||

| Portugal | 735,929 | ||||

| Spain | 340,479 | ||||

| Germany | 159,809 | ||||

| Syria- Lebanon- Palestine- Iraq - Middle-Eastern | 107,074 | ||||

| Japan-Korea | 104,355 | ||||

| Women over 12 years old who had offspring in Brazil and their children, by country of birth (1940 Census)[29] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of birth of the mother | Number of females over 12 years old who had children |

Number of children | |||

| Italy | 130,273 | 1,069,862 | |||

| Portugal | 99,197 | 524,940 | |||

| Spain | 66,354 | 436,305 | |||

| Japan | 35,640 | 171,790 | |||

| Germany | 22,232 | 98,653 | |||

| Brazil | 6,809,772 | 38,716,508 | |||

Others

[edit]On the other hand, in 1998, the IBGE, within its preparation for the 2000 Census, experimentally introduced a question about "origem" (ancestry) in its "Pesquisa Mensal de Emprego" (Monthly Employment Survey) to test the viability of introducing that variable in the census[30] (the IBGE ended by deciding against the inclusion of questions about it in the Census). The research interviewed about 90,000 people in six metropolitan regions (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Belo Horizonte, Salvador, and Recife).[30]

| Arrival of Italian immigrants to Brazil by periods (source: IBGE)[31] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1884-1893 | 1894–1903 | 1904–1913 | 1914–1923 | 1924–1933 | 1934–1944 | 1945–1949 | 1950–1954 | 1955–1959 | |

| 510,533 | 537,784 | 196,521 | 86,320 | 70,177 | 15,312 | N/A | 59,785 | 31,263 | |

| Italian population in Brazil[32] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Estimated Italian population (by Giorgio Mortara) | Year | Italian estimates | Year | Brazilian Census |

| 1880 | 50,000 | 1881* | 82,000 | ||

| 1890 | 230,000 | 1891* | 554,000 | ||

| 1900 | 540,000 | 1901** | 1,300,000 | ||

| 1902 | 600,000 | 1904** | 1,100,000 | ||

| 1930 | 435,000 | 1927* | 1,837,887 | 1920 | 558,405 |

| 1940 | 325,000 | 1940 | 325,283 | ||

.* Commissariato Generale dell'Emigrazione

.** Consulates

The 1920 census was the first one to show a more specific figure about the size of the Italian population in Brazil (558,405). However, since the 20th century, the arrival of new Italian immigrants to Brazil has been in steady decline. The previous censuses of 1890 and 1900 had limited information. In consequence, there are no official figures about the size of the Italian population in Brazil during the mass immigration period (1880–1900). There are estimates available, and the most reliable was done by Giorgio Mortara even though his figures may have underestimated the real size of the Italian population.[33] On the other hand, Angelo Trento believes that the Italian estimates are "certainly exaggerated"[33] and "lacking of any foundation"[33] since they found a figure of 1,837,887 Italians in Brazil for 1927. Another evaluation conducted by Bruno Zuculin found 997,887 Italians in Brazil in 1927. All of those figures include only people born in Italy, not their Brazilian-born descendants.[32]

Main Italian settlements in Brazil

[edit]Areas of settlement

[edit]Among all Italians who immigrated to Brazil, 70% went to the State of São Paulo. In consequence, São Paulo has more people with Italian ancestry than any region of Italy itself.[34] The rest went mostly to the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Minas Gerais.

Internal migration made many second- and third-generation Italians move to other areas. In the early 20th century, many rural Italian workers from Rio Grande do Sul migrated to the west of Santa Catarina and then farther north to Paraná.

More recently, third- and fourth-generation Italians have migrated to other areas and so people of Italian descent can be found in Brazilian regions in which the immigrants had never settled, such as in the Cerrado region of Central-West, in the Northeast and in the Amazon rainforest area, in the extreme North of Brazil.[36][37]

| Farms owned by a foreigner (1920) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrants | Farms[38] | ||

| Italians | 35.984 | ||

| Portuguese | 9.552 | ||

| Germans | 6.887 | ||

| Spanish | 4.725 | ||

| Russians | 4.471 | ||

| Austrians | 4.292 | ||

| Japanese | 1.167 | ||

Southern Brazil

[edit]

The main areas of Italian settlement in Brazil were the Southern and Southeastern Regions, namely the states of São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais.

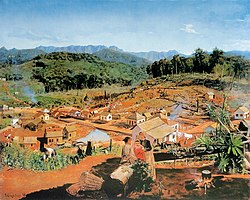

The first colonies to be populated by Italians were created in the highlands of Rio Grande do Sul (Serra Gaúcha). They were Garibaldi and Bento Gonçalves. The immigrants were predominantly from Veneto, in northern Italy. After five years, in 1880, the great numbers of Italian immigrants arriving caused the Brazilian government to create another Italian colony, Caxias do Sul. After initially settling in the government-promoted colonies, many Italian immigrants spread into other areas of Rio Grande do Sul, seeking better opportunities, and created many other Italian colonies on their own, mainly in highlands, because the lowlands were already populated by German immigrants and native gaúchos.

Italians established many vineyards in the region. The wine produced in those areas of Italian colonization in southern Brazil is much appreciated within the country, but little is available for export. In 1875, the first Italian colonies were established in Santa Catarina, which lies immediately to the north of Rio Grande do Sul. The colonies gave rise to towns such as Criciúma, and later also spread further north, to Paraná.

In the colonies of southern Brazil, Italian immigrants at first stuck to themselves, where they could speak their native Italian dialects and keep their culture and traditions. With time, however, they would become thoroughly integrated economically and culturally into the larger society. In any case, Italian immigration to southern Brazil was very important to the economic development and the culture of the region.

Southeastern Brazil

[edit]Imagine you travel eight thousand nautic miles, across the Mediterranean and the Atlantic and suddenly find yourself in Italy. That's São Paulo. It seems paradoxical, but it is a reality, because São Paulo is an Italian city.

Some of the immigrants settled in the colonies in Southern Brazil. However, most of them settled in Southeastern Brazil (mainly in the State of São Paulo). At first, the government was responsible for bringing the immigrants (in most cases, paying for their transportation by ship), but later, the farmers were responsible for making contracts with immigrants or specialized companies in recruiting Italian workers. Many posters were spread in Italy, with pictures of Brazil, selling the idea that everybody could become rich there by working with coffee, which was called by the Italian immigrants the green gold. Most coffee plantations were in the States of São Paulo and Minas Gerais, and in a smaller proportion also in the States of Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro.

Rio de Janeiro was declining in the 19th century as a farming producer, and São Paulo had already taken the lead as a coffee producer/exporter in the early 20th century, as well as big producer of sugar and other important crops. Thus, migrants were naturally more attracted to the State of São Paulo and the southern states.

Italians migrated to Brazil as families.[40] The colono, as a rural immigrant was called, had to sign a contract with the farmer to work in the coffee plantation for a minimum period of time. However, the situation was not easy. Many Brazilian farmers were used to command slaves and treated the immigrants as indentured servants.

In Southern Brazil, the Italian immigrants were living in relatively well-developed colonies, but in Southeastern Brazil they were living in semislavery conditions in the coffee plantations. Many rebellions against Brazilian farmers occurred, and public denouncements caused great commotion in Italy, forcing the Italian government to issue the Prinetti Decree, which established barriers to immigration to Brazil.

| Year | Italians | Percentage of the city[32] |

|---|---|---|

| 1886 | 5,717 | 13% |

| 1893 | 45,457 | 35% |

| 1900 | 75,000 | 31% |

| 1910 | 130,000 | 33% |

| 1916 | 187,540 | 37% |

In 1901, 90% of industrial workers and 80% of construction workers in São Paulo were Italians.[41]

| Year | Italians | Percentage of the city |

|---|---|---|

| 1886 | 1,050 | 6,5%[43] |

| 1920 | 8,235 | 15%[44] |

| 1934 | 4,185 | 8,1%[45] |

| 1940 | 2,467 | 5%[46] |

| Year | Italians | Percentage of the city |

|---|---|---|

| 1886 | 158 | 1,5%[43] |

| 1920 | 10,907 | 16%[47] |

| 1934 | 6,211 | 7,6%[48] |

| 1940 | 3,777 | 4,7%[49] |

São Carlos and Ribeirão Preto were two of the main coffee plantation centers. Both were respectively in the North-Central and Northeastern regions of São Paulo state, a zone known by its hot temperature and a fertile soil in which some of the richest coffee farms were and attracted most immigrants arriving in São Paulo, including Italians, between 1901 and 1940.[50]

| Year | Italians[32] |

|---|---|

| 1895 | 20,000 |

| 1901 | 30,000 |

| 1910 | 35,000 |

| 1920 | 31,929 |

| 1940 | 22,768 |

Other parts of Brazil

[edit]In the State of Mato Grosso do Sul, Italian descendants are 5% of the population.[51]

Decline of Italian immigration

[edit]

In 1902, the Italian immigration to Brazil started to decline. From 1903 to 1920, only 306,652 Italians immigrated to Brazil, compared to 953,453 to Argentina and 3,581,322 to the United States. This was mainly due to the Prinetti Decree in Italy, banning subsidized immigration to Brazil. The Prinetti Decree was issued because of the commotion in the Italian press about the poverty faced by most Italians in Brazil.

The end of slavery made most former slaves left the plantations and so there was a labour shortage on coffee plantations.[52] Moreover, "natural inequality of human beings", "hierarchy of races", Social Darwinism, Positivism and other theories were used to explain that the European workers were superior to the native workers. In consequence, passages were offered to Europeans (the so-called "subsidized immigration"), mostly to Italians, so that they could come to Brazil and work on the plantations.[32]

Those immigrants were employed in enormous latifundia (large-scale farms), formerly employing slaves. In Brazil, there were no labour laws (the first concrete labour laws appeared only in the 1930s, under President Getúlio Vargas) and so workers had almost no legal protection. Contracts signed by the immigrants could easily be violated by the Brazilian landowners who were accustomed to dealing with African slaves.

The remnants of slavery influenced how Brazilian landowners dealt with Italian workers: immigrants were often monitored, with extensive hours of work. In some cases, they were obliged to buy products that they needed from the landowner. Moreover, the coffee farms were located in rather isolated regions. If the immigrants became sick, they would take hours to reach the nearest hospital.

The structure of labor used on farms included the labor of Italian women and children. Keeping their Italian culture was also made more difficult: the Catholic churches and Italian cultural centers were far from farms. The immigrants who did not accept the standards imposed by landowners were replaced by other immigrants. That forced them to accept the impositions of landowners, or they would have to leave their lands. Even though Italians were considered to be "superior" to blacks by Brazilian landowners, the situation faced by Italians in Brazil was so similar to that of the slaves that farmers called them escravos brancos (white slaves in Portuguese).[32]

The destitution faced by Italians and other immigrants in Brazil caused great commotion in the Italian press, which culminated in the Prinetti Decree in 1902. Many immigrants left Brazil after their experience on São Paulo's coffee farms. Between 1882 and 1914, 1.5 million immigrants of different nationalities came to São Paulo, and 695,000 left the state, or 45% of the total. The high numbers of Italians asking the Italian consulate a passage to leave Brazil was so significant that in 1907, most Italian funds for repatriation were used in Brazil. It is estimated that, between 1890 and 1904, 223,031 (14,869 annually) Italians left Brazil, mainly after failed experiences on coffee farms. Most of the Italians who left the country were unable to add the money they wanted. Most returned to Italy, but others remigrated to Argentina, Uruguay or to the United States.

The output of immigrants concerned Brazilian landowners, who constantly complained about the lack of workers. Spanish immigrants began arriving in greater numbers, but soon, Spain also started to create barriers for further immigration of Spaniards to coffee farms in Brazil. The continuing problem of lack of labor in the farms was, then, temporarily resolved with the arrival of Japanese immigrants, from 1908.[32]

Despite the high numbers of immigrants leaving the country, most Italians remained in Brazil. Most of the immigrants remained only one year working on coffee farms and then left the plantations. A few earned enough money to buy their own lands and became farmers themselves. However, most migrated to Brazilian cities. Many Italians worked in factories (in 1901, 81% of the São Paulo's factory workers were Italians). In Rio de Janeiro, many the factory workers were Italians. In São Paulo, those workers established themselves in the center of the city, living in cortiços (degraded multifamily row houses). The agglomerations of Italians in cities gave birth to typically Italian neighborhoods, such as Mooca, which is until today linked to its Italian past. Other Italians became traders, mostly itinerant traders, selling their products in different regions.

A common presence on the streets of São Paulo were the Italian boys working as newspaper boys, as an Italian traveler observed: "In the crowd, we can see many Italian boys, shabby and barefoot, selling the newspapers from the city and from Rio de Janeiro, bothering the passersby with their offerings and their shouting of street roguish."[32]

Despite the poverty and even semi-slavery conditions faced by many Italians in Brazil, most of the population achieved some personal success and changed their lower-class situation. Even though most of the first generation of immigrants still lived in poverty, their children, born in Brazil, often changed their social status as they diversified their field of work, leaving the poor conditions of their parents and often becoming part of the local elite.[32]

Assimilation

[edit]Except for some isolated cases of violence between Brazilians and Italians, especially between 1892 and 1896, integration in Brazil was quick and peaceful. For Italians in São Paulo, scholars suggest that assimilation occurred within two generations. Research suggests that even first-generation immigrants born in Italy soon became assimilated in the new country. Even in Southern Brazil, where most of the Italians were living in isolated rural communities, with little contact with Brazilians, which kept the Italian patriarchal family structure, and therefore the father chose the wife or husband for their children, giving preference to Italians, assimilation was also quick.[32]

According to the 1940 census in Rio Grande do Sul, 393,934 people reported to speak German as their first language (11.86% of the state's population). In comparison, 295,995 reported to speak Italian, mostly dialects (8.91% of the state's population). Even though Italian immigration was larger and more recent than German immigration, the Italian group tended to be more easily assimilated due to the Latin cultural link. In the 1950 Census, the number of people in Rio Grande do Sul who reported to speak Italian dropped to 190,376.

In São Paulo, where more Italians settled, in the 1940 census 28,910 Italian-born people reported to speak Italian at home (only 13.6% of the state's Italian population). In comparison, 49.1% of the immigrants of other nationalities reported to keep speaking their native languages at home (with the exception of Portuguese). Thus, the prohibition of speaking Italian, German, and Japanese during World War II was not so serious to the Italian community as it was to the other two groups.[32]

A major measure of the government occurred in 1889, when Brazilian citizenship was granted to all immigrants, but the act had little influence on their identity or assimilation process. Both the Italian newspapers in Brazil and the Italian government were uncomfortable with the assimilation of Italians in the country, which occurred mostly after the Great Naturalization period. Italian institutions encouraged the entry of Italians in Brazilian politics, but the presence of immigrants was initially small. Italian dialects came to dominate the streets of São Paulo and in some Southern localities. Over time, languages based on Italian dialects tended to disappear, and their presence is now small.[32]

At first, especially in rural Southern Brazil, Italians tended to marry only other Italians. Over time and with the decrease of more immigrants arriving, in Southern Brazil they started to integrate themselves with Brazilians. About Italians in Santa Catarina, the Italian consul asserted:

The marriage between an Italian man and a Brazilian woman, between an Italian woman and a Brazilian man is very common, and it would be even more frequent if the majority of the Italians were not living segregated on the countryside.[32]

There is little information about this trend, but it was noticed a large process of integration since World War I. However, some more closed members of the Italian community saw this integration process as negative. Indigenous peoples in Brazil were often treated as savages, and conflicts between Italians and Indigenous peoples for the occupation of lands in Southern Brazil were common.[32]

Prosperity

[edit]Historically, Italians have been divided into two groups in Brazil. Those in Southern Brazil lived in rural colonies in contact with mostly other people of Italian descent. However, those in Southeast Brazil, the most populated region of the country, integrated into Brazilian society quite quickly.

After some years working in coffee plantations, some immigrants earned enough money to buy their own land and become farmers themselves. Others left the rural areas and moved to cities, mainly São Paulo, Campinas, São Carlos and Ribeirão Preto. A very few became very rich in the process and attracted more Italian immigrants. In the early 20th century, São Paulo became known as the City of the Italians,[53] because 31% of its inhabitants were of Italian nationality in 1900.[54] The city of São Paulo had the second-highest population of people with Italian ancestry in the world at this time, after only Rome.[34] In Campinas, street signs in Italian were common,[55] a large commercial and services sector owned by Italian Brazilians developed, and more than 60% of the population had Italian surnames.[56]

Italian immigrants were very important to the development of many big cities in Brazil, such as São Paulo, Porto Alegre, Curitiba and Belo Horizonte. Bad conditions in rural areas made thousands of Italians move there. Most of them became laborers and participated actively in the industrialization of Brazil in the early 20th century. Others became investors, bankers and industrialists, such as Count Matarazzo, whose family became the richest industrialists in São Paulo by holding more than 200 industries and businesses. In Rio Grande do Sul, 42% of the industrial companies have Italians roots.[36]

Italians and their descendants were also quick to organize themselves and establish mutual aid societies (such as the Circolo Italiano), hospitals, schools (such as the Istituto Colégio Dante Alighieri, in São Paulo), labor unions, newspapers as Il Piccolo from Mooca and Fanfulla (for the whole city of São Paulo), magazines, radio stations and association football teams such as: Clube Atlético Votorantim, the old Sport Club Savóia from Sorocaba, Clube Atlético Juventus of Italians Brazilians from Mooca (old worker quarter from city of São Paulo), Esporte Clube Juventude and the great clubs (which had the same name) Palestra Italia, later renamed to Sociedade Esportiva Palmeiras in São Paulo and Cruzeiro Esporte Clube in Belo Horizonte.

| Industries | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1907 | 1920 | ||

| Brazil[57] | 2.258 | 13.336 | |

| Owned by Italians[32] | 398 (17,6%) | 2.119 (15,9%) | |

| Owners of 204 largest industries in São Paulo (1962)[58] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | Percentage | ||

| Immigrant | 49,5% | ||

| Son of an immigrant | 23,5% | ||

| Brazilian (more than 3 generations) | 15,7% | ||

| Grandson of an immigrant | 11,3% | ||

| Ethnic origin | Percentage | ||

| Italians | 34,8% | ||

| Brazilians | 15,7% | ||

| Portuguese | 11,7% | ||

| Germans | 10,3% | ||

| Syrians and Lebanese | 9,0% | ||

| Russians | 2,9% | ||

| Austrians | 2,4% | ||

| Swiss | 2,4% | ||

| Other Europeans | 9,1% | ||

| Others | 2,0% | ||

| Industries owned by an Italian[32] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | 1907 | 1920 | |

| São Paulo | 120 | 1,446 | |

| Minas Gerais | 111 | 149 | |

| Rio Grande do Sul | 50 | 227 | |

| Rio de Janeiro (city + state) | 42 | 89 | |

| Paraná | 31 | 61 | |

| Santa Catarina | 13 | 56 | |

| Bahia | 8 | 44 | |

| Amazonas | 5 | 5 | |

| Pará | 5 | 10 | |

| Pernambuco | 3 | 3 | |

| Paraíba | 2 | 4 | |

| Espírito Santo | 1 | 18 | |

| Mato Grosso | 1 | 3 | |

| Other states | 5 | 4 | |

Characteristics of Italian immigration in Brazil

[edit]

| Italian immigration to Brazil (1876–1920)[59] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region of origin |

Number of immigrants |

Region of origin |

Number of immigrants |

| Veneto (North) | 365,710 | Sicily (South) | 44,390 |

| Campania (South) | 166,080 | Piedmont (North) | 40,336 |

| Calabria (South) | 113,155 | Apulia (South) | 34,833 |

| Lombardy (North) | 105,973 | Marche (Center) | 25,074 |

| Abruzzo-Molise (South) | 93,020 | Lazio (Center) | 15,982 |

| Tuscany (Center) | 81,056 | Umbria (Center) | 11,818 |

| Emilia-Romagna (North) | 59,877 | Liguria (North) | 9,328 |

| Basilicata (South) | 52,888 | Sardinia (South) | 6,113 |

| Total : 1,243,633 | |||

Areas of origin

[edit]

Most of the Italian immigrants to Brazil came from Northern Italy; however, they were not distributed homogeneously among the extensive Brazilian regions. In the State of São Paulo, the Italian community was more diverse including a large number of people from the South and the Center of Italy.[60] Even today, 42% of the Italians in Brazil came from Northern Italy, 36% from Central Italy regions, and only 22% from Southern Italy. Brazil is the only American country with a large Italian community in which Southern Italian immigrants are a minority.[36]

In the first decades, the vast majority of the immigrants came from the North. Since Southern Brazil received most of the early settlers, the vast majority of its immigrants came from the extreme North of Italy, mainly from Veneto and particularly from the provinces of Vicenza (32%), Belluno (30%) and Treviso (24%).[32] In Rio Grande do Sul, many came from Cremona, Mantua, from parts of Brescia, and also from Bergamo, in the region of Lombardy, close to Veneto. The regions of Trentino and of Friuli-Venezia Giulia also sent many immigrants to the South of Brazil. Of the immigrants in Rio Grande do Sul, 54% came from the Veneto, 33% from Lombardy, 7% from Trentino, 4.5% from Friuli-Venezia Giulia and only 1.5% from other parts of Italy.[61]

From the early 20th century, the agrarian crisis started to affect Southern Italy as well, and many people immigrated to Brazil, mostly to the state of São Paulo, since it needed workers to embrace the coffee plantations. The Italian immigrants in São Paulo came from mostly Veneto, Calabria, Campania.[62] After the end of World War II, a small number of Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians emigrated to Brazil during the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus, leaving their homelands, which were lost to Italy and annexed to Yugoslavia after the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947.[63]

| Italian immigration to Brazil (1870-1959)[64] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Italian Region | Percentage | ||

| North | 53.7% | ||

| South | 32.0% | ||

| Centre | 14.5% | ||

| Regional origins of Italian immigrants to Brazil (1870-1959) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Percentage | ||

| Veneto | 26.6% | ||

| Campania | 12.1% | ||

| Calabria | 8.2% | ||

| Lombardy | 7.7% | ||

| Tuscany | 5.9% | ||

| Friuli-Venezia Giulia | 5.8% | ||

| Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol | 5.3% | ||

| Abruzzo | 5.0% | ||

| Emilia-Romagna | 4.3% | ||

| Basilicata | 3.8% | ||

| Sicily | 3.2% | ||

| Piedmont | 2.8% | ||

| Apulia | 2.5% | ||

| Marche | 1.8% | ||

| Molise | 1.8% | ||

| Lazio | 1.1% | ||

| Umbria | 0.8% | ||

| Liguria | 0.7% | ||

| Sardinia | 0.4% | ||

| Aosta Valley | 0.2% | ||

| Main group of Italians immigrants living in São Paulo State (1936)[65] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Population | ||

| Veneto | 228,142 | ||

| Campania | 91,960 | ||

| Calabria | 72,686 | ||

| Lombardy | 51,338 | ||

| Tuscany | 47,874 | ||

| Main groups of Italians in some neighborhoods in São Paulo | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Neighborhood[32][66] | ||

| Calabria | Bixiga | ||

| Campania and Apulia | Brás | ||

| Veneto | Bom Retiro | ||

Italian influences in Brazil

[edit]Language

[edit]The Italian is more heard in São Paulo than in Turin, Milan or Naples, because while between us the dialects are spoken, in São Paulo all dialects merge under the Venetians' and Toscans' influx, who are the majority, and the natives adopted the Italian as an official language.

Most Brazilians with Italian ancestry now speak Brazilian Portuguese as their native language. During World War II, the public use of Italian, German, and Japanese was forbidden.[68][69]

Italian dialects have influenced the Portuguese spoken in some areas of Brazil.[70] Italian was so widespread in São Paulo that the Portuguese traveler Sousa Pinto said that he could not speak with cart drivers in Portuguese because they all spoke Italian dialects and gesticulated as Neapolitans.[71]

The Italian influence on Portuguese spoken in São Paulo is no longer as great as before, but the accent of the city's inhabitants still has some traces of the Italian accents common in the beginning of the 20th century like the intonation and such expressions as Belo, Ma vá!, Orra meu! and Tá entendendo?.[72] Other characteristic is the difficulty to speak Portuguese in plural, saying plural words as they were singulars.[73] The lexical influence of Italian on Brazilian Portuguese, however, has remained quite small.

A similar phenomenon occurred in the countryside of Rio Grande do Sul[70] but encompassing almost exclusively those of Italian origin.[61] On the other hand, is a different phenomenon: Talian, which emerged mostly in the northeastern part of the state (Serra Gaúcha). Talian is a variant of the Venetian language with influences from other Italian dialects and Portuguese.[2] In Southern Brazilian rural areas marked by bilingualism, even among the monolingual Portuguese-speaking population, the Italian-influenced accent is fairly typical.

Music

[edit]The Italian influence in Brazil affects also music with traditional Italian songs and the merging with other Brazilians music styles. One of the main results of the fusion is samba paulista, a samba with strong Italians influence.

Samba paulista was created by Adoniran Barbosa (born João Rubinato), the son of Italians immigrants. His songs translated the life of the Italian neighborhoods in São Paulo and merged São Paulo dialect with samba, which latter made him known as the "people's poet."[74]

One of the main example is Samba Italiano, which that has a Brazilian rhythm and theme but (mostly) Italian lyrics. Below, the lyrics of this song have the parts in (mangled) Portuguese in bold and the parts in Italian in a normal font:

| Original in São Paulo's pidgin

Gioconda, piccina mia,

Piove, piove,

Ti ricordi, Gioconda,

|

Free translation to English Gioconda, my little

It rains, it rains

Do you remember, Gioconda

|

Cuisine

[edit]

Italians brought new recipes and types of food to Brazil and also helped in the development of the cuisine of Brazil. Italian staple dishes like pizza and pasta are very common and popular in Brazil. Pasta is extremely common, either simple unadorned pasta with butter or oil or accompanied by a tomato- or bechamel-based sauce.

Aside from the typical Italian cuisine like pizza, pasta, risotto, panettone, milanesa, polenta, calzone, and ossobuco, Italians helped to create new dishes that today are typically considered Brazilian. Galeto (from the Italian galletto, little rooster), frango com polenta (chicken with fried polenta), Bife à parmegiana (a steak prepared with Parmigiano-Reggiano), Mortadella sandwich (a sandwich made of mortadella sausage, Provolone cheese, sourdough bread, mayonnaise and Dijon mustard), Catupiry cheese, new types of sausage like linguiça Calabresa and linguiça Toscana (literally Calabrian and Tuscan sausage),[76] chocotone (panettone with chocolate chips) and many other recipes were created or influenced by the Italian community.

The nhoque de 29 ("gnocchi of 29") defines the widespread custom in some South American countries of eating a plate of gnocchi, a type of Italian pasta, on the 29th of each month. The custom is widespread especially in the states of the Southern Cone such as Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay;[77][78][79] these countries being recipients of a considerable Italian immigration between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. There is a ritual that accompanies lunch with gnocchi, namely putting money under the plate which symbolizes the desire for new gifts. It is also customary to leave a banknote or coin under the plate to attract luck and prosperity to the dinner.[80]

The tradition of serving gnocchi on the 29th of each month stems from a legend based on the story of Saint Pantaleon, a young doctor from Nicomedia who, after converting to Christianity, made a pilgrimage through northern Italy. There Pantaleon practiced miraculous cures for which he was canonized. According to legend, on one occasion when he asked Venetian peasants for bread, they invited him to share their poor table.[81] In gratitude, Pantaleon announced a year of excellent fishing and excellent harvests. That episode occurred on 29 July, and for this reason that day is remembered with a simple meal represented by gnocchi.[80]

Other influences

[edit]

- Use of ciao ("tchau" in Brazilian-Portuguese) as a 'goodbye' salutation (all of Brazil)[82]

- Wine production (in the South)

- 218 loanwords (italianisms), such as agnolotti, rigatoni, sugo as regards gastronomy, ambasciata, cittadella, finta as regards sport, lotteria, tombola as regards games, raviolatrice, vasca as regards technology and stiva as regards the navy.[83]

- Early introduction of more advanced low-scale farming techniques (Minas Gerais, São Paulo and all Southern Brazil)

Education

[edit]Italian international schools in Brazil:

- Scuola Italiana Eugenio Montale - São Paulo

- Istituto Italo-Brasiliano Biculturale Fondazione Torino - Belo Horizonte

Current Italian emigration in Brazil

[edit]In 2019, 11,663 people with Italian nationality emigrated from Italy to Brazil according to the Italian World Report 2019, totaling 447,067 Italian citizens living in Brazil until 2019.[84]

Notable people

[edit]Arts and Entertainment

[edit]- André Abujamra, Brazilian score composer, musician, singer, actor and comedian

- Bruna Abdullah, Brazilian actress

- Fernanda Andrade, Brazilian actress, model and singer

- Laura Petracco, Brazilian-Italian theatre actor

- Lélia Abramo, Italian-Brazilian actress

- Morena Baccarin, Brazilian-born American actress

- Celly Campello, Brazilian singer and a pioneer in Brazilian rock

- Rodrigo Santoro, Brazilian actor

- Ísis Valverde, Brazilian actress

Politics and Economists

[edit]- Count Francesco Matarazzo (1854–1937), Italian-born Brazilian industrialist and businessman

- Carlos Bolsonaro (born 1982), Brazilian politician, Jair Bolsonaro's son

- Eduardo Bolsonaro (born 1984), Brazilian lawyer, federal police officer and politician; Jair Bolsonaro's son

- Flávio Bolsonaro (born 1981), Brazilian lawyer, entrepreneur and politician; Jair Bolsonaro's son

- Itamar Franco, Brazilian former politician, 33rd president of Brazil.

- Guido Mantega, Italian-born Brazilian economist and politician

- Jair Bolsonaro (born 1955), 38th President of Brazil

- Roger Agnelli, Brazilian investment banker and entrepreneur

- Romeu Zema, Brazilian businessman, administrator and politician

- Sergio Moro, Brazilian jurist, former federal judge, college professor and politician

Religious people

[edit]- Geraldo Agnelo, Brazilian prelate

Royal family

[edit]- Dom Afonso, Prince Imperial and heir apparent to the throne of the Empire of Brazil

Sports (football)

[edit]- Adam Adami, professional footballer

- Alex Meschini, football coach and former footballer

- Andre Anderson, professional footballer

- Amphilóquio Guarisi, former national footballer

- Angelo Sormani, former national footballer

- Dino da Costa, former national footballer

- Éder, former national footballer

- Emerson Palmieri, Italian national team footballer

- Gabriel Martinelli, Brazilian national team footballer

- Jorginho, Italian national team footballer

- José Altafini, former national footballer

- Luiz Felipe, Italian national team footballer

- Otávio Fantoni, former national footballer

- Raphinha, Brazilian national team footballer

- Rafael Tolói, Italian national team footballer

- Thiago Motta, Italian football manager and former national footballer

Sports (bull riding)

[edit]- Guilherme Marchi, Brazilian bull rider

Sports (mixed martial arts)

[edit]- Tabatha Ricci, UFC fighter

- Diego Nunes

See also

[edit]- Brazil–Italy relations

- Brazilians in Italy

- Italian Americans

- Italian Argentines

- Italian Australians

- Italian Canadians

- Italian Chileans

- Italian Colombians

- Italian Peruvians

- Italian Uruguayans

- Italo-Venezuelans

- Italian diaspora

- Italian immigration in Minas Gerais

- Demography of Brazil

- White Brazilians

- White Latin Americans

- List of Portuguese words of Italian origin

- Italian language in Brazil

- Memória do Bixiga Museum

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Rapporto Italiano Nel Mondo 2019 : Diaspora italiana in cifre" (PDF). Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ a b c Enciclopédia de Línguas do Brasil - Línguas de Imigração Européia - Talian (Vêneto Brasileiro). Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ a b "Personalidades da comunidade italiana recebem o troféu "Loba Romana"". Revista digital "Oriundi". 7 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ "República Italiana". www.itamaraty.gov.br. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ a b IBGE.Censo brasileiro de 1940.

- ^ A game of mirrors: the changing face of ethno-racial constructs and language in the Americas. Thomas M. Stephens. University Press of America, 2003. ISBN 0-7618-2638-6, ISBN 978-0-7618-2638-5. Retrieved on 2010-10-14.

- ^ "Brazil - the Country and its People" (PDF). www.brazil.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ "Italians - History of the Community". Milpovos.prefeitura.sp.gov.br. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Nova Veneza (in Portuguese)". Archived from the original on 19 August 2008.

- ^ "República Italiana". www.itamaraty.gov.br. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020.

- ^ "Veja 15/12/99". abril.com.br. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ "Notizie d'Italia - Cavalcanti é a maior família brasileira". italiaoggi.com.br.

- ^ "Migração - Cidadania Italiana - Dupla Cidadania - Encontro analisa imigração italiana em MG". italiaoggi.com.br.

- ^ Immigrazione Italiana nell’America del Sud (Argentina, Uruguay e Brasile). p. 36.

- ^ Clemente, Elvo.Italianos no Brazil p.231

- ^ Favero, Luigi; Graziano Tassello. Cent'anni di emigrazione italiana (1876–1976). p. 136.

- ^ Constitutional amendment ECR-000.003-1994

- ^ a b Desiderio, Peron (18 June 2007). "Pollastri confirma que o Parlamento italiano estuda restrições à cidadania por direito de sangue na terceira geração" [Pollastri confirms that the Italian Parliament is considering restrictions on citizenship by right of blood in the third generation]. Insieme (in Portuguese). insieme.com.br. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Roteiro para a obtenção do reconhecimento da cidadania Italiana" [Guideline for recognition of Italian citizenship]. Consulate General of Italy in Sao Paulo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ^ Gabaccia, Donna R.; Ottanelli, Fraser M. (2001). "Introduction". In Donna R. Gabaccia; Fraser M. Ottanelli (eds.). Italian Workers of the World: Labor Migration and the Formation of Multiethnic States. University of Illinois Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-252-02659-1.

- ^ Generations. Family Tree plus v.8,5. Software to design genealogical trees. Additional information of groups of immigrants that settled in the US.

- ^ a b IBGE. Brasil 500 anos - Italianos - Regiões de Origem Archived 30 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ DEL BOCA, Daniela; VENTURINI, Alessandra. Italian Migration. Working paper in CHILD Centre for Household, Income, Labor and Demographic Economics. 2001 Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Emigrazione Italiana in Brasile" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ Buckman, Kirk (2004). "VI. Italian Citizenship, Nationality Law and Italic Identities". In Piero Bassetti; Paolo Janni (eds.). Italic Identity in Pluralistic Contexts: Toward the Development of Intercultural Competencies. CRVP. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-56518-208-0.

- ^ a b Angelo Trento. Do outro lado do Atlântico: um século de imigração italiana no Brasil, p. 52–53, at Google Books

- ^ Italy wants her sons to stay at home, The New York Times, March 12, 1904

- ^ "Emigrazione italiana in Brasile per regione di origine (1876-1920)" (in Italian). Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d IBGE.Brazilian Census of 1940.

- ^ a b Schwartzman, Simon (November 1999). "Fora de foco: diversidade e identidades étnicas no Brasil" [Out of focus: diversity and ethnic identities in Brazil] (PDF). Novos Estudos (in Portuguese) (55). Brazilian Centre for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP): 3. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Do Outro Lado do Atlântico - Um Século de Imigração Italiana no Brasil, p. 100, at Google Books

- ^ a b c Angelo Trento. Do outro lado do Atlântico: um século de imigração italiana no Brasil, p. 67, at Google Books

- ^ a b Pereira, Liésio. "A capital paulista tem sotaque italiano" (in Portuguese). radiobras.gov.br. Archived from the original on 28 July 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c "Gli Italiani in Brasile" [The Italians in Brazil] (PDF) (in Italian). consultanazionaleemigrazione.it. October 2003. pp. 11, 19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ COLLI, Antonello. Italiani in Brasile, 36 milioni di oriundi. L'Italia nel'Mondo Website Archived 3 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Italianos no Brasil: "andiamo in 'Merica-", p. 252, at Google Books

- ^ Estados autoritários e totalitários e suas representações, p. 179, at Google Books

- ^ "IMIGRANTES ITALIANOS: Um portal de ajuda na pesquisa da origem dos ancestrais italianos". imigrantesitalianos.com.br.

- ^ Fazer a América: a imigração em massa para a América Latina, p. 318, at Google Books

- ^ Artes plásticas na Semana de 22, p. 76, at Google Books

- ^ a b Relatório Apresentado pela Comissão de Estatística ao Exmo. Presidente da Província de São Paulo, 1888, p. 24

- ^ "Recenseamento do Brazil. Realizado em 1 de Setembro de 1920. População (5a parte, tomo 2). População do Brazil, por Estados e municipios, segundo o sexo, a nacionalidade, a idade e as profissões". archive.org. Typ da Estatistica. 1930.

- ^ "p.177". Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Censo Demográfico 1940, pt. XVII, t. 1, SP, p. 103

- ^ "Recenseamento do Brazil. Realizado em 1 de Setembro de 1920. População (1a parte). População do Brazil por Estados, municipios e districtos, segundo o sexo, o estado civil e a nacionalidade". archive.org. Typ da Estatistica. 1926.

- ^ "p. 174". Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Censo Demográfico 1940, pt. XVII, t. 1, SP, p. 102

- ^ "p. 126". seade.gov.br.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Italians in Mato Grosso do Sul". geomundo.com.br. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ^ "Il Brasile dietro l'angolo" (in Italian). Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "L'operosità italiana all'estero. Le industrie riunite F. Matarazzo, in San Paulo del Brasile" (in Italian). Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "migrantes espanhois" (PDF). images.paulocel29.multiply.multiplycontent.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011.

- ^ J.M.Fantinatti (2006). "Pró-Memória de Campinas-SP". pro-memoria-de-campinas-sp.blogspot.com.

- ^ "Sobrenomes Italianos". imigrantesitalianos.com.br.

- ^ IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. "IBGE - Séries Estatísticas & Séries Históricas - atividade industrial - indústrias extrativa e de transformação - séries históricas e encerradas - inquéritos e Censos industriais - Estabelecimentos industriais nas datas dos Inquéritos Industriais e do Censo 1920 - 1907-1920". ibge.gov.br.

- ^ Bresser-Pereira, Luiz Carlos. "Origens Étnicas e Sociais do Empresário Paulista" [Ethnic and Social Origins of Entrepreneurship in São Paulo] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ IBGE. "IBGE - Brasil: 500 anos de povoamento - território brasileiro e povoamento - italianos - regiões de origem". ibge.gov.br.

- ^ Seyferth, Giralda. "Histórico da Imigração no Brasil: Italianos" [History of Immigration in Brazil: Italians] (in Portuguese). Dias Marques Advocacia. Archived from the original on 10 October 2004.

- ^ a b "Italianos: A maior parte veio do Vêneto" [Italians: A major portion came from Veneto] (in Portuguese). riogrande.com.br. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ MORILA, Aílton Pereira. "Pelos Cantos da Cidade: Música Popular em São Paulo na Passagem do Século XIX ao XX. Fênix – Revista de História e Estudos Culturais; January-February-March 2006; Vol. 3; Ano III; nº 1" (PDF). Fênix: Revista de História e Estudos Culturais (in Portuguese). ISSN 1807-6971. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2008.

- ^ "Il Giorno del Ricordo" (in Italian). 10 February 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ "Immigrazione Italiana nell'America del Sud (Argentina, Uruguay e Brasile)" [Italian Immigration in South America (Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil)] (PDF) (in Italian). immigrazione-altoadige.ne. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2011.

- ^ Do outro lado do Atlântico: um século de imigração italiana no Brasil at Google Books

- ^ Mérica, Mérica!: italianos no Brasil, p. 111, at Google Books

- ^ "Full text of "Nell' America meridionale (Brasile-Uruguay-Argentina)"". archive.org. 1908.

- ^ Thomé, Nilson (2008). "A Nacionalização do Ensino no Contestado, Centro-Oeste de Santa Catarina na Primeira Metade do Século XX" [The Nationalization of Education in the Contested, Center-West of Santa Catarina in the First Half of the 20th Century] (in Portuguese). revistas.udesc.br. pp. 85–86. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ Bolognini, Carmen Zink; Payer, Maria Onice (June 2005). "Línguas do Brasil - Línguas de Imigrantes" [Languages of Brazil - Languages of Immigrants] (PDF). Ciência e Cultura (in Portuguese). 57 (2). São Paulo: Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science: 42–46. ISSN 0009-6725. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ a b "La lingua italiana in Brasile" (in Italian). 27 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ Zink Bolognini, Carmen; de Oliveira, Ênio; Hashiguti, Simone (September 2005). "Línguas estrangeiras no Brasil: História e histórias" [Foreign Languages in Brazil: History and Narratives] (PDF). Language and Literacy in Focus: Teaching Foreign Languages (in Portuguese). Institute of Language Studies (IEL), Brazil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Domínio LocaWeb". uol.com.br.

- ^ "G1 - Sotaque da Mooca pode virar patrimônio histórico imaterial de SP - notícias em São Paulo". globo.com. 6 June 2011.

- ^ "Adoniran Barbosa, o Poeta do Povo" [Adoniran Barbosa, the Poet of the People]. globo.com (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 12 June 2008.

- ^ "Laticínios Catupiry: History". catupiry.com.br. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010.

- ^ "Linguiça calabresa" (in Portuguese). caras.uol.com.br. 13 January 2009. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012.

- ^ "¿Por qué los argentinos comen ñoquis el 29 de cada mes y qué tiene que ver eso con los empleados públicos?". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "Ñoquis el 29" (in Spanish). 3 May 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "El ñoquis de cada 29" (in Spanish). 29 November 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ a b Petryk, Norberto. "Los ñoquis del 29" (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ "Ñoquis del 29: origen de una tradición milenaria" (in Spanish). 29 July 2004. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "How to Say Goodbye in Portuguese". 6 August 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ "Gli italianismi nel portoghese brasiliano" (in Italian). Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ "Rapporto Italiano Nel Mondo 2019 : Diaspora italiana in cifre" (PDF). Retrieved 1 January 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Bertonha, João Fábio. Os italianos. Editora Contexto. São Paulo, 2005 ISBN 85-7244-301-0

- Cenni, Franco. Os italianos no Brasil. EDUSP. São Paulo, 2003 ISBN 85-314-0671-4

- Clemente, Elvo (et al.). Italianos no Brasil: contribuições na literatura e nas ciências, séculos XIX e XX EDIPUCRS. Porto Alegre, 1999 ISBN 85-7430-046-2

- Franzina, Emilio. Storia dell'emigrazione italiana. Donzelli Editore. Roma, 2002 ISBN 88-7989-719-5

- Favero, Luigi y Tassello, Graziano. Cent'anni di emigrazione italiana (1876–1976). Cser. Roma, 1978. OCLC 1192108952

- Trento, Ângelo. Do outro lado do Atlântico. Studio Nobel. São Paulo, 1988 ISBN 85-213-0563-X

External links

[edit]- oriundi.net, a site for descendants from Italians in Brazil

- Italianisms in Brazilian Portuguese (In Italian)

Italian Brazilians

View on GrokipediaHistorical Background

Economic and Social Crises in Italy Driving Emigration

Following the unification of Italy in 1861, the country encountered profound economic difficulties, particularly in the southern regions known as the Mezzogiorno, where archaic agrarian systems and rapid population growth fostered chronic poverty and land scarcity. Large latifundia estates dominated, leaving most peasants as landless laborers or sharecroppers under the mezzadria system, which offered minimal returns amid soil exhaustion and fragmented holdings.[11] Population pressures intensified these issues, as birth rates outpaced agricultural productivity, resulting in widespread underemployment and subsistence-level existence for rural families.[12] The liberalization of trade post-unification eliminated protective tariffs, flooding southern markets with cheap northern and foreign goods, which undermined local artisanal industries and small-scale farming. Heavy taxation to service national debt and fund northern infrastructure disproportionately burdened southern households, while fiscal policies neglected regional development, deepening North-South divides.[12] Agrarian crises peaked in the 1880s, triggered by global wheat price collapses from New World imports and the phylloxera epidemic that ravaged vineyards, slashing rural incomes and sparking unrest such as the 1891 Fasci Siciliani peasant revolts.[13] Social conditions compounded economic woes, with high illiteracy rates exceeding 70% in the South, endemic malaria, and frequent natural disasters like the 1883 Casamicciola earthquake and 1908 Messina-Reggio calamity that killed around 100,000, displacing survivors into destitution. Mandatory military conscription and feudal-like obligations further alienated the populace, framing emigration as an escape from oppression.[14] These push factors propelled mass outflows; from 1876 to 1915, approximately 14 million Italians emigrated, with over 9 million departing between 1900 and 1914 alone, many targeting Brazil's labor demands as a viable alternative to European destinations.[11] Southern provinces such as Calabria, Basilicata, and Sicily contributed disproportionately, seeking relief from cycles of poverty that unification had failed to alleviate.[12]Brazilian Post-Slavery Labor Demands and Recruitment Policies

The abolition of slavery through the Lei Áurea on May 13, 1888, abruptly ended Brazil's reliance on enslaved labor, which had underpinned the economy, particularly the coffee plantations of São Paulo province that produced over 50% of the nation's output by the 1880s.[15] Many freed individuals migrated to urban centers or returned to northeastern origins, exacerbating a severe labor shortage on rural estates where production volumes demanded sustained fieldwork.[16] Coffee planters, facing unprofitable stagnation without replacements, pressured provincial authorities to accelerate free labor importation, building on pre-abolition experiments but intensifying subsidies and recruitment to sustain export-driven growth.[15] São Paulo's government formalized a comprehensive immigration program by 1886, fully operational post-1888, featuring state-funded third-class steamship passages from European ports, rail transport to the interior, and temporary accommodations at the Hospedaria dos Imigrantes in the capital, which processed over 2.5 million arrivals by 1920.[17] Recruiters, often commissioned agents operating in Italian cities like Genoa and Naples, disseminated multilingual pamphlets and contracts promising family-head wages, housing, food rations, and a share of crop yields under the colonato sharecropping system, where immigrants bound themselves to planters for three-year terms on fazendas.[17] These incentives targeted rural Europeans amenable to agricultural toil, with Italians prioritized due to their availability from agrarian crises in southern Italy and lower recruitment costs compared to northern groups.[18] Federal and provincial laws, such as São Paulo's 1889 immigration code, allocated annual budgets exceeding 10 contos de réis (roughly equivalent to millions in modern terms) for subsidies, explicitly favoring non-Iberian Europeans to secure docile, productive workers while advancing demographic "whitening" aims articulated in elite discourse.[19] Italian inflows surged, accounting for the bulk of São Paulo's 100,000+ annual immigrant quotas in peak 1890s years, as private societies and fazendeiros supplemented state efforts with direct advances to secure labor contracts.[20] However, deceptive recruitment practices—overstating earnings and omitting debt traps from supply advances—prompted scrutiny, culminating in Italy's 1902 Prinetti Decree banning subsidized emigration to Brazil amid reports of exploitative conditions akin to servitude.[21]Major Waves of Immigration: 1870s–1920s Patterns and Volumes

The primary surge of Italian immigration to Brazil spanned from 1870 to 1920, during which an estimated 1.4 to 1.5 million Italians arrived, constituting about 42% of all immigrants entering the country in that era.[22] This volume reflected Brazil's aggressive recruitment policies to replace emancipated slave labor on coffee plantations, particularly in São Paulo, following the abolition of slavery in 1888.[10] Early arrivals in the 1870s were limited, with initial organized groups of around 1,500 Italians settling in rural colonies in southern Brazil, such as in Rio Grande do Sul, under government-subsidized programs aimed at agricultural colonization.[23] Immigration accelerated dramatically in the 1880s and peaked in the 1890s, driven by economic distress in Italy's northern and central regions—primarily Veneto, Emilia-Romagna, and Lombardy—and targeted recruitment by Brazilian coffee planters who subsidized voyages and contracts. Annual inflows reached tens of thousands, with over 50,000 Italians arriving in peak years like 1891, predominantly as temporary colonos bound to fazenda contracts for sharecropping coffee harvests.[1] Approximately 70% of these immigrants disembarked at the Port of Santos for São Paulo's plantations, while smaller contingents headed to southern states for independent farming colonies or to emerging urban centers.[24] Family units formed a significant portion of migrants, contrasting with more male-dominated flows to other destinations, though high return rates—estimated at 40-50%—indicated temporary sojourns rather than permanent settlement for many.[25] By the 1910s, volumes declined sharply due to Brazil's 1902 regulatory reforms curbing exploitative contracts, improved conditions in Italy post-unification, and competition from U.S. opportunities, with annual arrivals dropping below 10,000 by World War I.[26] Overall, São Paulo absorbed the bulk—around 1 million—of the 1.5 million total, fostering rapid demographic shifts but also social tensions from debt peonage and disease in labor camps.[1] These patterns underscored a causal link between Brazil's export agriculture demands and Italy's rural overpopulation, yielding a gross migration far exceeding net population gains due to repatriation and mortality.[22]Demographic Overview

Historical Census Figures: 1880s–1940s

The Brazilian censuses of 1890, 1900, 1920, and 1940 provide the primary empirical data on the Italian-born population, reflecting the peak and subsequent decline of the immigrant stock amid high arrival rates offset by return migration, naturalization, and mortality. These figures understate the full Italian-origin population, as most censuses focused on birthplace rather than ancestry until 1940, when parental nativity was queried to approximate descendants.[27]| Census Year | Italian-Born Population | Percentage of Total Brazilian Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 230,000 | Approximately 1.6% | Rapid growth from early 1880s arrivals; total Brazil population ~14.3 million.[27] |

| 1900 | 540,000 | 3.1% | Peak stock coinciding with mass immigration; total population ~17.4 million.[27] |

| 1920 | 558,405 | Approximately 1.8% | Slight increase despite slowing inflows; total population ~30.6 million.[18] |

| 1940 | 285,124 | Approximately 0.7% | Sharp decline due to aging cohort and naturalization; total population ~41.2 million; additionally, 1,260,931 reported an Italian father and 1,069,862 an Italian mother, indicating ~2.3 million with at least one Italian-born parent.[28] |

Contemporary Estimates: Descendants and Self-Identification

Estimates of Brazilians with Italian ancestry range from 25 to 32 million, comprising roughly 12-16% of the national population of approximately 203 million as of the 2022 census. Italian diplomatic sources, including consulates, consistently cite around 30 million descendants, reflecting the progeny of the 1.5 million immigrants who arrived mainly from 1870 to 1920, adjusted for demographic growth and intermarriage. These figures derive from historical immigration records cross-referenced with vital statistics and community registrations, rather than direct enumeration, as Brazil's official statistics do not track ancestry comprehensively.[29][30] Self-identification with Italian heritage remains elusive in quantitative terms, as the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) has not included ancestry questions in censuses since 1940, when about 1.3 million reported an Italian father and 1.1 million an Italian mother—figures representing recent immigrants and their immediate offspring rather than broader descent. In the absence of updated national data, analysts infer lower active self-identification rates due to widespread miscegenation, with multiple ancestries common; for instance, southern Brazilian states show high genetic European admixture, including Italian components, but individuals typically prioritize Brazilian national identity over specific ethnic origins. Community indicators, such as over 68,000 Italian citizenship recognitions for Brazilians in 2024 alone, suggest millions maintain ancestral awareness, particularly amid recent policy-driven interest in dual nationality, though this does not equate to primary self-identification.[31]Settlement Patterns and Regional Development

Southern Brazil: Rural Colonies and Agricultural Foundations

Italian rural colonies in Southern Brazil emerged in the mid-1870s, driven by provincial governments' efforts to settle underpopulated lands with European immigrants skilled in agriculture. In Rio Grande do Sul, the first colonies, Conde d’Eu and Dona Isabel, were founded in 1876, with settlers arriving as early as 1875 to establish communities like Bento Gonçalves and Caxias do Sul.[32] [18] Between 1875 and 1914, over 100,000 Italians, primarily from Veneto (54%) and Lombardia (33%), immigrated to Rio Grande do Sul, concentrating in rural colonies in the northern provinces and Serra Gaúcha uplands.[32] [33] These settlers received plots of 30 to 60 hectares, which they cleared using slash-and-burn techniques on Araucaria forests to cultivate subsistence crops such as corn, beans, wheat, rice, potatoes, and tobacco.[32] Agricultural practices evolved from polyculture for family sustenance to specialization in viticulture starting in the 1880s, leveraging the region's climate for grape cultivation. Italian colonos planted Isabella varieties—introduced decades earlier—and by 1914 had developed a burgeoning wine sector, bolstered by state initiatives like the 1898 distribution of 25,000 seedlings and railway expansions.[32] This shift addressed initial economic constraints and poor soil fertility, establishing the basis for commercial winemaking in Brazil.[32] In Santa Catarina, Italian colonies began forming in 1875, including sites like Criciúma, while Paraná saw similar settlements dominated by Veneto immigrants, promoting isolated, self-sufficient farming communities across the three states.[18] [33] Colonists endured challenges including severe winters, hailstorms, erosion, and skirmishes with indigenous Kaingang and Xokleng groups, yet their family-operated holdings transformed forested highlands into productive agricultural zones, reducing forest cover from 36% in 1850 to 25% by 1914.[32]Southeastern Brazil: Coffee Plantations and Urban Migration

Following the abolition of slavery in Brazil in 1888, the state of São Paulo, the epicenter of coffee production, urgently required labor to sustain its expanding plantations, leading to subsidized recruitment of Italian immigrants as colonos under a sharecropping system.[34] Approximately 1.5 million Italians arrived in Brazil between 1880 and 1930, with around 70% settling in São Paulo, where they comprised the bulk of the workforce on fazendas (plantations) dedicated to coffee cultivation.[1] These colonos, often arriving in family units, were allotted plots of land with coffee trees to tend, receiving payment primarily in subsistence goods, housing, and a share of the harvest, though the system frequently trapped them in cycles of debt due to high costs for tools, food, and transport charged by plantation owners.[34] Conditions on the fazendas were grueling, with long hours of manual labor under intense sun, rudimentary housing, and limited medical care, prompting investigations by Italian consular agents who described many operations as resembling penal colonies rather than agricultural enterprises.[35] High mortality rates from diseases like beriberi and malaria, coupled with exploitative contracts, led to widespread disillusionment; by the early 1900s, Italian government reports highlighted abuses, including withheld wages and physical coercion, fueling repatriation efforts and diplomatic tensions between Italy and Brazil.[36] Despite these hardships, the influx of Italian labor enabled São Paulo's coffee output to surge, with the state producing over 50% of Brazil's coffee by 1900, underpinning economic growth but at the cost of immigrant welfare.[34] Discontent with rural drudgery drove significant urban migration among Italian colonos starting in the late 1890s and accelerating through the 1910s, as former plantation workers sought opportunities in São Paulo city's burgeoning industries, including textiles, food processing, and construction.[37] By 1901, Italians accounted for 90% of the city's industrial workforce and formed dense communities in neighborhoods like Mooca and Bixiga, transforming peripheral areas into vibrant enclaves of Italian commerce and culture.[24] This shift contributed to São Paulo's rapid urbanization, with the city's population tripling between 1890 and 1920, as immigrants leveraged skills in masonry, baking, and entrepreneurship to escape agricultural dependency and fuel the state's industrialization. The urban influx not only diversified São Paulo's economy beyond monoculture coffee but also established patterns of social mobility, with second-generation Italian Brazilians entering white-collar professions and politics, though initial urban settlers faced overcrowding and low wages in factories that echoed plantation rigors.[37] By the 1920s, Italians and their descendants represented about 16% of São Paulo's total population, solidifying the region's demographic and developmental trajectory through this dual rural-urban dynamic.Dispersal to Other Regions and Urban Centers