Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Superman

View on Wikipedia

| Clark Kent / Kal-El Superman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

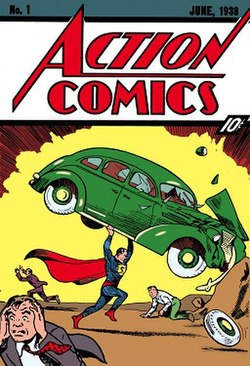

| First appearance | Action Comics #1 (cover-dated June 1938; published April 18, 1938) |

| Created by | Jerry Siegel (writer) Joe Shuster (artist) |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Kal-El (birth name; Krypton identity) Clark Kent (adopted name; civilian identity) |

| Species | Kryptonian |

| Place of origin | Krypton |

| Team affiliations | |

| Partnerships |

|

| Notable aliases |

|

| Abilities | See list

|

Superman is a superhero created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, first appearing in issue #1 of Action Comics, published in the United States on April 18, 1938.[1] Superman has been regularly published in American comic books since then, and has been adapted to other media including radio serials, novels, films, television shows, theater, and video games. Superman is the archetypal superhero: he wears an outlandish costume, uses a codename, and fights evil and averts disasters with the aid of extraordinary abilities. Although there are earlier characters who arguably fit this definition, it was Superman who popularized the superhero genre and established its conventions. He was the best-selling superhero in American comic books up until the 1980s;[2] it is also the best-selling comic book series in the world with 600 million copies sold.[3]

Superman was born Kal-El, on the fictional planet Krypton. As a baby, his parents Jor-El and Lara sent him to Earth in a small spaceship shortly before Krypton was destroyed in an apocalyptic cataclysm. His ship landed in the American countryside near the fictional town of Smallville, Kansas, where he was found and adopted by farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, who named him Clark Kent. The Kents quickly realized he was superhuman; due to the Earth's yellow sun, all of his physical and sensory abilities are far beyond those of a human, and he is nearly impervious to harm and capable of unassisted flight. His adoptive parents having instilled him with strong morals, he chooses to use his powers to benefit humanity, and to fight crime as a vigilante. To protect his personal life, he changes into a primary-colored costume and uses the alias "Superman" when fighting crime. Clark resides in the fictional American city of Metropolis, where he works as a journalist for the Daily Planet alongside supporting characters including his love interest and fellow journalist Lois Lane, photographer Jimmy Olsen, and editor-in-chief Perry White. His enemies include Brainiac, General Zod, and archenemy Lex Luthor.

Since 1939, Superman has been featured in both Action Comics and his own Superman comic. He exists within the DC Universe, where he interacts with other heroes including fellow Justice League members like Wonder Woman and Batman, and appears in various titles based on the team. Different versions of the character exist in alternative universes; the Superman from the Golden Age of comic books has been labeled as the Earth-Two version while the version appearing in Silver Age and Bronze Age comics is labeled the Earth One Superman. His persona has also inspired legacy characters such as Supergirl, Superboy and Krypto the Superdog.

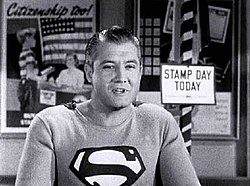

Superman has been adapted outside of comics. The radio series The Adventures of Superman ran from 1940 to 1951 and would feature Bud Collyer as the voice of Superman. Collyer would also voice the character in a series of animated shorts produced by Fleischer/Famous Studios and released between 1941 and 1943. Superman also appeared in film serials in 1948 and 1950, played by Kirk Alyn. Christopher Reeve would portray Superman in the 1978 film and its sequels, and define the character in cinema for generations. Superman would continue to appear in feature films, including a series starring Henry Cavill and a 2025 film starring David Corenswet. The character has also appeared in numerous television series, including Adventures of Superman, played by George Reeves, and Superman: The Animated Series, voiced by Tim Daly.

Development

[edit]

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster met in 1932 while attending Glenville High School in Cleveland and bonded over their admiration of fiction. Siegel aspired to become a writer and Shuster aspired to become an illustrator. Siegel wrote amateur science fiction stories, which he self-published as a magazine called Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization. His friend Shuster often provided illustrations for his work.[4] In January 1933, Siegel published a short story in his magazine titled "The Reign of the Superman". The titular character is a homeless man named Bill Dunn who is tricked by an evil scientist into consuming an experimental drug. The drug gives Dunn the powers of mind-reading, mind-control, and clairvoyance. He uses these powers maliciously for profit and amusement, but then the drug wears off, leaving him a powerless vagrant again. Shuster provided illustrations, depicting Dunn as a bald man.[5]

Siegel and Shuster shifted to making comic strips, with a focus on adventure and comedy. They wanted to become syndicated newspaper strip authors, so they showed their ideas to various newspaper editors. However, the newspaper editors were not impressed, and told them that if they wanted to make a successful comic strip, it had to be something more sensational than anything else on the market. This prompted Siegel to revisit Superman as a comic strip character.[6][7] Siegel modified Superman's powers to make him even more sensational. Like Bill Dunn, the second prototype of Superman is given powers against his will by an unscrupulous scientist, but instead of psychic abilities, he acquires superhuman strength and bullet-proof skin.[8][9] Additionally, this new Superman was a crime-fighting hero instead of a villain, because Siegel noted that comic strips with heroic protagonists tended to be more successful.[10] In later years, Siegel once recalled that this Superman wore a "bat-like" cape in some panels, but typically he and Shuster agreed there was no costume yet, and there is none apparent in the surviving artwork.[11][12]

Siegel and Shuster showed this second concept of Superman to Consolidated Book Publishers, based in Chicago.[13][a] In May 1933, Consolidated had published a comic book titled Detective Dan: Secret Operative 48.[14] It contained all-original stories as opposed to reprints of newspaper strips, which was a novelty at the time.[15] Siegel and Shuster put together a comic book in a similar format called The Superman. A delegation from Consolidated visited Cleveland that summer on a business trip and Siegel and Shuster took the opportunity to present their work in person.[16][17] Although Consolidated expressed interest, they later pulled out of the comics business without ever offering a book deal because the sales of Detective Dan were disappointing.[18][19]

Siegel believed publishers kept rejecting them because he and Shuster were young and unknown, so he looked for an established artist to replace Shuster.[20] When Siegel told Shuster what he was doing, Shuster reacted by burning their rejected Superman comic, sparing only the cover. They continued collaborating on other projects, but for the time being Shuster was through with Superman.[21]

Siegel wrote to numerous artists.[20] The first response came in July 1933 from Leo O'Mealia, who drew the Fu Manchu strip for the Bell Syndicate.[22][23] In the script that Siegel sent to O'Mealia, Superman's origin story changes: He is a "scientist-adventurer" from the far future when humanity has naturally evolved "superpowers". Just before the Earth explodes, he escapes in a time-machine to the modern era, whereupon he immediately begins using his superpowers to fight crime.[24] O'Mealia produced a few strips and showed them to his newspaper syndicate, but they were rejected. O'Mealia did not send to Siegel any copies of his strips, and they have been lost.[25]

In June 1934, Siegel found another partner, an artist in Chicago named Russell Keaton.[26][27] Keaton drew the Buck Rogers and Skyroads comic strips. In the script that Siegel sent Keaton in June, Superman's origin story further evolved: In the distant future, when Earth is on the verge of exploding due to "giant cataclysms", the last surviving man sends his three-year-old son back in time to the year 1935. The time-machine appears on a road where it is discovered by motorists Sam and Molly Kent. They leave the boy in an orphanage, but the staff struggle to control him because he has superhuman strength and impenetrable skin. The Kents adopt the boy and name him Clark, and teach him that he must use his fantastic natural gifts for the benefit of humanity. In November, Siegel sent Keaton an extension of his script: an adventure where Superman foils a conspiracy to kidnap a star football player. The extended script mentions that Clark puts on a special "uniform" when assuming the identity of Superman, but it is not described.[28] Keaton produced two weeks' worth of strips based on Siegel's script. In November, Keaton showed his strips to a newspaper syndicate, but they too were rejected, and he abandoned the project.[29][30]

Siegel and Shuster reconciled and resumed developing Superman together. The character became an alien from the planet Krypton. Shuster designed the now-familiar costume: tights with an "S" on the chest, over-shorts, and a cape.[31][32][33] They made Clark Kent a journalist who pretends to be timid, and conceived his colleague Lois Lane, who is attracted to the bold and mighty Superman but does not realize that he and Kent are the same person.[34]

In June 1935 Siegel and Shuster finally found work with National Allied Publications, a comic magazine publishing company in New York owned by Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson.[36] Wheeler-Nicholson published two of their strips in New Fun Comics #6 (1935): "Henri Duval" and "Doctor Occult".[37] Siegel and Shuster also showed him Superman and asked him to market Superman to the newspapers on their behalf.[38] In October, Wheeler-Nicholson offered to publish Superman in one of his own magazines.[39] Siegel and Shuster refused his offer because Wheeler-Nicholson had demonstrated himself to be an irresponsible businessman. He had been slow to respond to their letters and had not paid them for their work in New Fun Comics #6. They chose to keep marketing Superman to newspaper syndicates themselves.[40][41] Despite the erratic pay, Siegel and Shuster kept working for Wheeler-Nicholson because he was the only publisher who was buying their work, and over the years they produced other adventure strips for his magazines.[42]

Wheeler-Nicholson's financial difficulties continued to mount. In 1936, he formed a joint corporation with Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz called Detective Comics, Inc. in order to release his third magazine, which was titled Detective Comics. Siegel and Shuster produced stories for Detective Comics too, such as "Slam Bradley". Wheeler-Nicholson fell into deep debt to Donenfeld and Liebowitz, and in early January 1938, Donenfeld and Liebowitz petitioned Wheeler-Nicholson's company into bankruptcy and seized it.[4][43]

In early December 1937, Siegel visited Liebowitz in New York, and Liebowitz asked Siegel to produce some comics for an upcoming comic anthology magazine called Action Comics.[44][45] Siegel proposed some new stories, but not Superman. Siegel and Shuster were, at the time, negotiating a deal with the McClure Newspaper Syndicate for Superman. In early January 1938, Siegel had a three-way telephone conversation with Liebowitz and an employee of McClure named Max Gaines. Gaines informed Siegel that McClure had rejected Superman, and asked if he could forward their Superman strips to Liebowitz so that Liebowitz could consider them for Action Comics. Siegel agreed.[46] Liebowitz and his colleagues were impressed by the strips, and they asked Siegel and Shuster to develop the strips into 13 pages for Action Comics.[47] Having grown tired of rejections, Siegel and Shuster accepted the offer. At least now they would see Superman published.[48][49] Siegel and Shuster submitted their work in late February and were paid US$130 (equivalent to $2,900 in 2024) for their work ($10 per page).[50] In early March they signed a contract at Liebowitz's request in which they gave away the copyright for Superman to Detective Comics, Inc. This was normal practice in the business, and Siegel and Shuster had given away the copyrights to their previous works as well.[51]

The duo's revised version of Superman appeared in the first issue of Action Comics, which was published on April 18, 1938. The issue was a huge success thanks to Superman's feature.[1][52][53]

Influences

[edit]Siegel and Shuster read pulp science-fiction and adventure magazines, and many stories featured characters with fantastical abilities such as telepathy, clairvoyance, and superhuman strength. One character in particular was John Carter of Mars from the novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs. John Carter is a human who is transported to Mars, where the lower gravity makes him stronger than the natives and allows him to leap great distances.[54][55] Another influence was Philip Wylie's 1930 novel Gladiator, featuring a protagonist named Hugo Danner who had similar powers.[56][57]

Superman's stance and devil-may-care attitude were influenced by the characters of Douglas Fairbanks, who starred in adventure films such as The Mark of Zorro and Robin Hood.[58] The name of Superman's home city, Metropolis, was taken from the 1927 film of the same name.[59] Popeye cartoons were also an influence.[59]

Clark Kent's harmless facade and dual identity were inspired by the protagonists of such movies as Don Diego de la Vega in The Mark of Zorro and Sir Percy Blakeney in The Scarlet Pimpernel. Siegel thought this would make for interesting dramatic contrast and good humor.[60][61] Another inspiration was slapstick comedian Harold Lloyd. The archetypal Lloyd character was a mild-mannered man who finds himself abused by bullies but later in the story snaps and fights back furiously.[62]

Kent is a journalist because Siegel often imagined himself becoming one after leaving school. The love triangle between Lois Lane, Clark, and Superman was inspired by Siegel's own awkwardness with girls.[63]

The pair collected comic strips in their youth, with a favorite being Winsor McCay's fantastical Little Nemo.[59] Shuster remarked on the artists who played an important part in the development of his own style: "Alex Raymond and Burne Hogarth were my idols – also Milt Caniff, Hal Foster, and Roy Crane."[59] Shuster taught himself to draw by tracing over the art in the strips and magazines they collected.[4]

As a boy, Shuster was interested in fitness culture[64] and a fan of strongmen such as Siegmund Breitbart and Joseph Greenstein. He collected fitness magazines and manuals and used their photographs as visual references for his art.[4]

The visual design of Superman came from multiple influences. The tight-fitting suit and shorts were inspired by the costumes of wrestlers, boxers, and strongmen. In early concept art, Shuster gave Superman laced sandals like those of strongmen and classical heroes, but these were eventually changed to red boots.[35] The costumes of Douglas Fairbanks were also an influence.[65] The emblem on his chest was inspired by heraldic crests.[66] Many pulp action heroes such as swashbucklers wore capes. Superman's face was based on Johnny Weissmuller with touches derived from the comic-strip character Dick Tracy and from the work of cartoonist Roy Crane.[67]

The word "superman" was commonly used in the 1920s and 1930s to describe men of great ability, most often athletes and politicians.[68] It occasionally appeared in pulp fiction stories as well, such as "The Superman of Dr. Jukes".[69] It is unclear whether Siegel and Shuster were influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of the Übermensch; they never acknowledged as much.[70]

Comics

[edit]Comic books

[edit]Since 1938, Superman stories have been regularly published in periodical comic books published by DC Comics. The first and oldest of these is Action Comics, which began in April 1938.[1] Action Comics was initially an anthology magazine, but it eventually became dedicated to Superman stories. The second oldest periodical is Superman, which began in June 1939. Action Comics and Superman have been published without interruption (ignoring changes to the title and numbering scheme).[72][73] Several other shorter-lived Superman periodicals have been published over the years.[74] Superman is part of the DC Universe, which is a shared setting of superhero characters owned by DC Comics, and consequently he frequently appears in stories alongside the likes of Batman, Wonder Woman, and others.

More Superman comic books have been sold in publication history than any other American superhero character.[75] Exact sales figures for the early decades of Superman comic books are hard to find because, like most publishers at the time, DC Comics concealed this data from its competitors and thereby the general public, but given the general market trends at the time, sales of Action Comics and Superman probably peaked in the mid-1940s and thereafter steadily declined.[76] Sales data first became public in 1960, and showed that Superman was the best-selling comic book character of the 1960s and 1970s.[2][77][78] Sales rose again starting in 1987. Superman #75 (Nov 1992) had over 23 million copies sold,[79] making it the best-selling issue of a comic book of all time, due to a media sensation over the death of Superman in that issue.[80] Sales declined from that point on. In March 2018, Action Comics sold just 51,534 copies, although such low figures are normal for superhero comic books in general (for comparison, Amazing Spider-Man #797 sold only 128,189 copies).[81] The comic books have become a niche aspect of the Superman franchise due to low readership,[82] though they remain influential as creative engines for the movies and television shows. Comic book stories can be produced quickly and cheaply, and are thus an ideal medium for experimentation.[83]

Whereas comic books in the 1950s were read by children, since the 1990s the average reader has been an adult.[84] A major reason for this shift was DC Comics' decision in the 1970s to sell its comic books to specialty stores instead of traditional magazine retailers (supermarkets, newsstands, etc.) — a model called "direct distribution". This made comic books less accessible to children.[85]

Newspaper strips

[edit]Beginning in January 1939, a Superman daily comic strip appeared in newspapers, syndicated through the McClure Syndicate. A color Sunday version was added that November. Jerry Siegel wrote most of the strips until he was conscripted into the United States Army in 1943. The Sunday strips had a narrative continuity separate from the daily strips, possibly because Siegel had to delegate the Sunday strips to ghostwriters.[86] By 1941, the newspaper strips had an estimated readership of 20 million.[87] Joe Shuster drew the early strips, then passed the job to Wayne Boring.[88] From 1949 to 1956, the newspaper strips were drawn by Win Mortimer.[89] The strip ended in May 1966, but was revived from 1977 to 1983 to coincide with a series of movies released by Warner Bros.[90]

Editors

[edit]Initially, Jerry Siegel was allowed to write Superman more or less as he saw fit because nobody had anticipated the success and rapid expansion of the franchise.[91][92] But soon Siegel and Shuster's work was put under careful oversight for fear of trouble with censors.[93] Siegel was forced to tone down the violence and social crusading that characterized his early stories.[94] Editor Whitney Ellsworth, hired in 1940, dictated that Superman not kill.[95] Sexuality was banned, and colorfully outlandish villains such as Ultra-Humanite and Toyman were favored over gangsters as they were thought to be less frightening to young readers.[96]

Mort Weisinger was the editor on Superman comics from 1941 to 1970, his tenure briefly interrupted by military service. Siegel and his fellow writers had developed the character with little thought of building a coherent mythology, but as the number of Superman titles and the pool of writers grew, Weisinger demanded a more disciplined approach.[97] Weisinger assigned story ideas, and the logic of Superman's powers, his origin, the locales, and his relationships with his growing cast of supporting characters were carefully planned. Elements such as Bizarro, his cousin Supergirl, the Phantom Zone, the Fortress of Solitude, alternate varieties of kryptonite, robot doppelgangers, and Krypto were introduced during this era. The complicated universe built under Weisinger was beguiling to devoted readers but alienating to casuals.[98] Weisinger favored lighthearted stories over serious drama, and avoided sensitive subjects such as the Vietnam War and the American civil rights movement because he feared his right-wing views would alienate his left-leaning writers and readers.[99] Weisinger also introduced letters columns in 1958 to encourage feedback and build intimacy with readers.[100]

Weisinger retired in 1970 and Julius Schwartz took over. By his own admission, Weisinger had grown out of touch with newer readers.[101] Starting with The Sandman Saga, Schwartz updated Superman by making Clark Kent a television anchor, and he retired overused plot elements such as kryptonite and robot doppelgangers.[102] Schwartz also scaled Superman's powers down to a level closer to Siegel's depiction. These changes would eventually be reversed by later writers. Schwartz allowed stories with serious drama such as "For the Man Who Has Everything" (Superman Annual #11), in which the villain Mongul torments Superman with an illusion of happy family life on a living Krypton.

Schwartz retired from DC Comics in 1986 and was succeeded by Mike Carlin as an editor on Superman comics. His retirement coincided with DC Comics' decision to reboot the DC Universe with the companywide-crossover storyline "Crisis on Infinite Earths". In The Man of Steel, renowned artist and writer John Byrne rewrote the Superman mythos; again reducing Superman's powers, which writers had slowly re-strengthened, and revised many supporting characters, such as making Lex Luthor a billionaire industrialist rather than a mad scientist, and making Supergirl an artificial shapeshifting organism because DC wanted Superman to be the sole surviving Kryptonian.

Carlin was promoted to Executive Editor for the DC Universe books in 1996, a position he held until 2002. K.C. Carlson took his place as editor of the Superman comics.

Aesthetic style

[edit]In the earlier decades of Superman comics, artists were expected to conform to a certain "house style".[103] Joe Shuster defined the aesthetic style of Superman in the 1940s. After Shuster left National, Wayne Boring succeeded him as the principal artist on Superman comic books.[104] He redrew Superman taller and more detailed.[105] Around 1955, Curt Swan in turn succeeded Boring.[106] The 1980s saw a boom in the diversity of comic book art and now there is no single "house style" in Superman comics.[citation needed]

Copyright issues

[edit]Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster

[edit]In a contract dated March 1, 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster gave away the copyright to Superman to their employer, DC Comics (then known as Detective Comics, Inc.)[b] prior to Superman's first publication in April. Contrary to popular perception, the $130 that DC Comics paid them was for their first Superman story, not the copyright to the character — that, they gave away for free. This was normal practice in the comic magazine industry and they had done the same with their previous published works (Slam Bradley, Doctor Occult, etc.),[51] but Superman became far more popular and valuable than they anticipated and they much regretted giving him away.[107] DC Comics retained Siegel and Shuster, and they were paid well because they were popular with the readers.[108] Between 1938 and 1947, DC Comics paid them together at least $401,194.85 (equivalent to $7,550,000 in 2024).[109][110]

Siegel wrote most of the magazine and daily newspaper stories until he was conscripted into the United States Army in 1943, whereupon the task was passed to ghostwriters.[111][112] While Siegel was serving in Hawaii, DC Comics published a story featuring a child version of Superman called "Superboy", which was based on a script Siegel had submitted several years before. Siegel was furious because DC Comics did this without having bought the character.[113]

After Siegel's discharge from the Army, he and Shuster sued DC Comics in 1947 for the rights to Superman and Superboy. The judge ruled that Superman belonged to DC Comics, but that Superboy was a separate entity that belonged to Siegel. Siegel and Shuster settled out-of-court with DC Comics, which paid the pair $94,013.16 (equivalent to $1,230,374 in 2024) in exchange for the full rights to both Superman and Superboy.[114] DC Comics then fired Siegel and Shuster.[115]

DC Comics rehired Jerry Siegel as a writer in 1959.

In 1965, Siegel and Shuster attempted to regain rights to Superman using the renewal option in the Copyright Act of 1909, but the court ruled Siegel and Shuster had transferred the renewal rights to DC Comics in 1938. Siegel and Shuster appealed, but the appeals court upheld this decision. DC Comics fired Siegel once again, when he filed this second lawsuit.[116]

In 1975, Siegel and several other comic book writers and artists launched a public campaign for better compensation and treatment of comic creators. Warner Brothers agreed to give Siegel and Shuster a yearly stipend, full medical benefits, and credit their names in all future Superman productions in exchange for never contesting ownership of Superman. Siegel and Shuster upheld this bargain.[4]

Shuster died in 1992. DC Comics offered Shuster's heirs a stipend in exchange for never challenging ownership of Superman, which they accepted for some years.[114]

Siegel died in 1996. His heirs attempted to take the rights to Superman using the termination provision of the Copyright Act of 1976. DC Comics negotiated an agreement wherein it would pay the Siegel heirs several million dollars and a yearly stipend of $500,000 in exchange for permanently granting DC the rights to Superman. DC Comics also agreed to insert the line "By Special Arrangement with the Jerry Siegel Family" in all future Superman productions.[117] The Siegels accepted DC's offer in an October 2001 letter.[114]

Copyright lawyer and movie producer Marc Toberoff then struck a deal with the heirs of both Siegel and Shuster to help them get the rights to Superman in exchange for signing the rights over to his production company, Pacific Pictures. Both groups accepted. The Siegel heirs called off their deal with DC Comics and in 2004 sued DC for the rights to Superman and Superboy. In 2008, the judge ruled in favor of the Siegels. DC Comics appealed the decision, and the appeals court ruled in favor of DC, arguing that the October 2001 letter was binding. In 2003, the Shuster heirs served a termination notice for Shuster's grant of his half of the copyright to Superman. DC Comics sued the Shuster heirs in 2010, and the court ruled in DC's favor on the grounds that the 1992 agreement with the Shuster heirs barred them from terminating the grant.[114]

Under current US copyright law, Superman's first appearance in Action Comics #1 is due to enter the US public domain on January 1, 2034.[118][c] However, this will only apply (at first) to the character as he is depicted in 1938. In addition DC Comics retains trademarks on Superman's name, image and 'S' logo, and unlike copyrights, trademarks do not expire unless they cease to be used.[119]

Captain Marvel

[edit]Superman's success immediately begat a wave of imitations. The most successful from this period was Captain Marvel, first published by Fawcett Comics in December 1939. Captain Marvel had many similarities to Superman: Herculean strength, invulnerability, the ability to fly, a cape, a secret identity, and a job as a journalist. DC Comics filed a lawsuit against Fawcett Comics for copyright infringement.[120]

The trial began in March 1948 after seven years of discovery. The judge ruled that Fawcett had indeed infringed on Superman. However, the judge also found that the copyright notices that appeared with the Superman newspaper strips did not meet the technical standards of the Copyright Act of 1909 and were therefore invalid. Furthermore, since the newspaper strips carried stories adapted from Action Comics, the judge ruled that DC Comics had effectively abandoned the copyright to the Action Comics stories and Superman, and therefore forfeited its right to sue Fawcett for copyright infringement.[114]

DC Comics appealed this decision. The appeals court ruled that unintentional mistakes in the copyright notices of the newspaper strips did not invalidate the copyrights. Furthermore, Fawcett knew that DC Comics never intended to abandon the copyrights, and therefore Fawcett's infringement was not an innocent misunderstanding, and therefore Fawcett owed damages to DC Comics.[d] The appeals court remanded the case back to the lower court to determine how much Fawcett owed in damages.[114]

At that point, Fawcett Comics decided to settle out of court with DC Comics. Fawcett paid DC Comics $400,000 (equivalent to $4,701,000 in 2024) and agreed to stop publishing Captain Marvel. The last Captain Marvel story from Fawcett Comics was published in September 1953.[121]

DC Comics licensed Captain Marvel in 1972 and published crossover stories with Superman. By 1991, DC Comics had purchased Fawcett Comics and with it the full rights to Captain Marvel. DC eventually renamed the character "Shazam" to prevent disputes with Marvel Comics, who had created a character of their own named "Captain Marvel" back when the Fawcett character had been out of print.[122]

Character overview

[edit]Several elements of the Superman narrative have remained consistent in the myriad stories published since 1938.

Superman

[edit]In Action Comics #1 (1938), Superman is born on an alien world to a technologically advanced species that resembles humans. Shortly after he is born, his planet is destroyed in a natural cataclysm, but his scientist father foresaw the calamity and saves his baby son by sending him to Earth in a small spaceship. The ship is too small to carry anyone else, so Superman's parents are forced to stay behind and die in the cataclysm. The earliest newspaper strips name the planet Krypton, the baby Kal-L, and his biological parents Jor-L and Lora;[123] their names were changed to Jor-el, and Lara in a 1942 spinoff novel by George Lowther.[124] The ship lands in the American countryside, where the baby is discovered by the Kents, a farming couple.

The Kents name the boy Clark and raise him in a farming community. A 1947 episode of the radio serial places this yet unnamed community in Iowa.[125] It is named Smallville in Superboy #2 (June 1949). The 1978 Superman movie placed it in Kansas, as have most Superman stories since.[126] New Adventures of Superboy #22 (Oct. 1981) places it in Maryland.

In Action Comics #1 and most stories published before 1986, Superman's powers begin developing in infancy. From 1944 to 1986, DC Comics regularly published stories of Superman's childhood and adolescent adventures, when he called himself "Superboy". From 1986 on (beginning with Man of Steel #1), Superman's powers emerged more slowly and he began his superhero career as an adult.

The Kents teach Clark he must conceal his otherworldly origins and use his fantastic powers to do good. Clark creates the costumed identity of Superman so as to protect his personal privacy and the safety of his loved ones. As Clark Kent, he wears eyeglasses to disguise his face and wears his Superman costume underneath his clothes so that he can change at a moment's notice. To complete this disguise, Clark avoids violent confrontation, preferring to slip away and change into Superman when danger arises, and in older stories he would suffer occasional ridicule for his apparent cowardice.

In Superboy #78 (1960), Superboy makes his costume out of the indestructible blankets found in the ship he came to Earth in. In Man of Steel #1 (1986), Martha Kent makes the costume from human-manufactured cloth, and it is rendered indestructible by an aura that Superman projects. The "S" on Superman's chest at first was simply an initial for "Superman". When writing the script for the 1978 movie, Tom Mankiewicz made it the crest of Superman's Kryptonian family, the House of El.[127] This was carried over into some comic book stories and later movies, such as Man of Steel. In the comic story Superman: Birthright, the crest is described as an old Kryptonian symbol for hope.

Clark works as a newspaper journalist. In the earliest stories, he worked for The Daily Star, but the second episode of the radio serial changed this to the Daily Planet. In comics from the early 1970s, Clark worked as a television journalist, which was an attempt to modernize the character. However, for the 1978 movie, the producers chose to make Clark a newspaper journalist again because that was how most people outside of comic book readers knew him.[128]

The first story in which Superman dies was published in Superman #149 (1961), in which he is murdered by Lex Luthor by means of kryptonite. This story was "imaginary" and therefore was ignored in subsequent books. In Superman #188 (April 1966), Superman is killed by kryptonite radiation but is revived in the same issue by one of his android doppelgangers. In the 1990s The Death and Return of Superman story arc, after a deadly battle with Doomsday, Superman died in Superman #75 (Jan. 1993). He was later revived by the Eradicator using Kryptonian technology. In Superman #52 (May 2016) Superman is killed by kryptonite poisoning, and this time he is not resurrected, but replaced by the Superman of an alternate timeline.

Superman maintains a secret hideout called the "Fortress of Solitude", which is located somewhere in the Arctic. Here, Superman keeps a collection of mementos and a laboratory for science experiments. Action Comics #241 (1958) depicts the Fortress of Solitude as a cave in a mountain, sealed with a very heavy door that is opened with a gigantic key too heavy for anyone but Superman to use. In the 1978 movie, the Fortress of Solitude is a structure made of white crystal.

Clark Kent

[edit]Superman's secret identity is Clark Joseph Kent, a reporter for the Daily Planet. Although his name and history originate from his early life with his adoptive Earth parents, everything about Clark was staged for the benefit of his alternate identity: as a reporter for the Daily Planet, he receives late-breaking news before the general public, always has a plausible reason to be present at crime scenes, and need not strictly account for his whereabouts as long as he makes his publication deadlines. He sees his job as a journalist as an extension of his Superman responsibilities—bringing truth to the forefront and fighting for the little guy. He believes that everybody has the right to know what is going on in the world, regardless of who is involved.[129] In the Bronze Age of Comic Books, Clark Kent was featured in a series that appeared primarily in The Superman Family, "The Private Life of Clark Kent" where Superman dealt with various situations subtly while remaining Clark.

To deflect suspicion that he is Superman, Clark Kent adopted a mainly passive and introverted personality with conservative mannerisms, a higher-pitched voice, and a slight slouch. This personality is typically described as "mild-mannered", as in the opening narration of Max Fleischer's Superman animated theatrical shorts. These traits extended into Clark's wardrobe, which typically consists of a bland-colored business suit, a red necktie, black-rimmed glasses, combed-back hair, and occasionally a fedora. Clark wears his Superman costume underneath his street clothes, allowing easy changes between the two personae and the dramatic gesture of ripping open his shirt to reveal the familiar "S" emblem when called into action. His hair also changes with the clothing change, with Superman sporting a small curl or spit curl on his forehead. Superman usually stores his Clark Kent clothing compressed in a secret pouch within his cape,[130] though some stories have shown him leaving his clothes in some covert location (such as the Daily Planet storeroom)[131] for later retrieval.

As Superman's alter ego, the personality, concept, and name of Clark Kent have become synonymous with secret identities and innocuous fronts for ulterior motives and activities. In 1992, Superman co-creator Joe Shuster told the Toronto Star that the name derived from 1930s cinematic leading men Clark Gable and Kent Taylor, but the persona from bespectacled silent film comic Harold Lloyd and himself.[132] Clark's middle name is given variously as either Joseph, Jerome, or Jonathan, being allusions to creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, and to his adoptive father.

Personality

[edit]In the original Siegel and Shuster stories, Superman's personality is rough and aggressive. He often uses excessive force and terror against criminals, on some occasions even killing them. This came to an end in late 1940 when new editor Whitney Ellsworth instituted a code of conduct for his characters to follow, banning Superman from ever killing.[133] The character was softened and given a sense of humanitarianism. Ellsworth's code, however, is not to be confused with "the Comics Code", which was created in 1954 by the Comics Code Authority and ultimately abandoned by every major comic book publisher by the early 21st century.

In his first appearances, Superman was considered a vigilante by the authorities, being fired upon by the National Guard as he razed a slum so that the government would create better housing conditions for the poor. By 1942, however, Superman was working side-by-side with the police.[134][135] Today, Superman is commonly seen as a brave and kind-hearted hero with a strong sense of justice, morality, and righteousness. He adheres to an unwavering moral code instilled in him by his adoptive parents.[136] His commitment to operating within the law has been an example to many citizens and other heroes, but has stirred resentment and criticism among others, who refer to him as the "big blue boy scout". Superman can be rather rigid in this trait, causing tensions in the superhero community.[137] This was most notable with Wonder Woman, one of his closest friends, after she killed Maxwell Lord.[137] Booster Gold initially had an icy relationship with the Man of Steel but grew to respect him.[138]

Having lost his home world of Krypton, Superman is very protective of Earth,[139] and especially of Clark Kent's family and friends. This same loss, combined with the pressure of using his powers responsibly, has caused Superman to feel lonely on Earth, despite having his friends and parents. Previous encounters with people he thought to be fellow Kryptonians, Power Girl[140] and Mon-El,[141] have led to disappointment. The arrival of Supergirl, who has been confirmed to be his cousin from Krypton, relieved this loneliness somewhat.[142] Superman's Fortress of Solitude acts as a place of solace for him in times of loneliness and despair.[143]

Abilities and weaknesses

[edit]The catalog of Superman's abilities and his strength has varied considerably over the vast body of Superman fiction released since 1938.

Since Action Comics #1 (1938), Superman has superhuman strength. The cover of Action Comics #1 shows him effortlessly lifting a car over his head. Another classic feat of strength on Superman's part is breaking steel chains. In some stories, he is strong enough to shift the orbits of planets[144] and crush coal into diamond with his hands.

Since Action Comics #1 (1938), Superman has a highly durable body, invulnerable for most practical purposes. At the very least, bullets bounce harmlessly off his body. In some stories, such as Kingdom Come, not even a nuclear bomb can harm him.

In the earliest stories, Superman's costume is made out of exotic materials that are as tough as he is, which is why it typically does not tear up when he performs superhuman feats. In later stories, beginning with Man of Steel #1 (1986), Superman's body is said to project an aura that renders invulnerable any tight-fitting clothes he wears, and hence his costume is as durable as he is even if made of common cloth.

In Action Comics #1, Superman could not fly. He traveled by running and leaping, which he could do to a prodigious degree thanks to his strength. Superman gained the ability to fly in the second episode of the radio serial in 1940.[145] Superman can fly faster than sound and in some stories, he can even fly faster than the speed of light to travel to distant galaxies.

Superman can project and perceive X-rays via his eyes, which allows him to see through objects. He first uses this power in Action Comics #11 (1939). Certain materials such as lead can block his X-ray vision.

Superman can project beams of heat from his eyes which are hot enough to melt steel. He first used this power in Superman #59 (1949) by applying his X-ray vision at its highest intensity. In later stories, this ability is simply called "heat vision".

Superman can hear sounds that are too faint for a human to hear, and at frequencies outside the human hearing range. This ability was introduced in Action Comics #11 (1939).

Since Action Comics #20 (1940), Superman possesses superhuman breath, which enables him to inhale or blow huge amounts of air, as well as holding his breath indefinitely to remain underwater or space without adverse effects. He has a significant focus of his breath's intensity to the point of freezing targets by blowing on them. The "freeze breath" was first demonstrated in Superman #129 (1959).

Action Comics #1 (1938) explained that Superman's strength was common to all Kryptonians because they were a species "millions of years advanced of our own". In the first newspaper strips, Jor-El is shown running and leaping like Superman, and his wife survives a building collapsing on her. Later stories explained they evolved superhuman strength simply because of Krypton's higher gravity. Superman #146 (1961) established that Superman's abilities other than strength (flight, durability, etc.) are activated by the light of Earth's yellow sun. This was shortly changed to all of his powers including strength being activated by yellow sunlight and deactivated by red sunlight similar to that of Krypton's sun.[146]

Weaknesses

[edit]Exposure to green kryptonite radiation nullifies Superman's powers and incapacitates him with pain and nausea; prolonged exposure will eventually kill him. Although green kryptonite is the most commonly seen form, writers have introduced other forms over the years: such as red, gold, blue, white, and black, each with peculiar effects.[147] Gold kryptonite, for instance, nullifies Superman's powers but otherwise does not harm him. Kryptonite first appeared in a 1943 episode of the radio serial.[148] It first appeared in comics in Superman #61 (Dec. 1949).[149]

Superman is also vulnerable to magic. Enchanted weapons and magical spells affect Superman as easily as they would a normal human. This weakness was established in Superman #171 (1964).

Like all Kryptonians, Kal-El is also highly susceptible to psychokinetic phenomena ranging along Telekinesis, Illusion casting, Mind control, etc., as shown in Wonder Woman Vol 2 # 219 (Sept. 2005). A powerful enough psionic can affect either the psyche or microbiology of Superman to induce strokes or mangle his internal organs, as well as disrupt his mind and perceptions of the world, something a young metahuman showcased in Superman #48 (Oct. 1990).

Many stories describe Superman as being vulnerable to radiation at wavelengths equal to the light of the "red sun" of the planet Krypton, which causes him to temporarily lose his powers.

Over the years, writers have invented many other weaknesses for Superman using various science fiction tropes, with some of these weaknesses only existing for a short period of time.

Occasional equipment

[edit]On occasion, Superman has made use of a special aeroplane called the Supermobile which has the same abilities as him and can protect him from the radiation of a red sun.[150]

Superman has used several fictional robots that resemble his appearance and have similar abilities. Superman robots played a particularly dominant role in the late 1950s and 1960s era Superman comics, when readers were first introduced to Superman possessing various robot duplicates. These robots each possessed a fraction of Superman's powers, and were sometimes used to substitute for him on missions or protect his secret identity.[151][152] One notable Superman robot was named Ajax, also known as Wonder Man.[153] Other Superman robots had other names, including Robot Z,[154] Robot X-3,[155] and MacDuff.[156]

The idea of Superman robots extended into Superboy and Supergirl stories of the period as well, with the two also possessing robotic duplicates.[157][158] In the early 1970s, the Superman comics largely abandoned the Superman robots as part of a change in tone and writing style. In-universe, the robots are rendered unusable by Earth's pollution levels and artificial radiation.[159] The notion of Superman robots was reintroduced for post-Crisis comic continuity in a late 1990s storyline. While under Dominus' control, Superman builds a series of robots to oversee the Earth. Unlike the original Superman robots, they possess a more mechanical appearance.[160] In Superman (vol. 2) #170, Krypto nearly kills Mongul and is confined to the Fortress of Solitude as punishment. A Superman robot nicknamed "Ned" is employed as Krypto's caretaker. In a later storyline, Brainiac 8 revived and increased the power to a forgotten Superman robot. The robot attacked the Teen Titans, killing Troia and Omen before it was defeated.[161]

Supporting characters

[edit]Superman's first and most famous supporting character is Lois Lane, introduced in Action Comics #1. She is a fellow journalist at the Daily Planet. As Jerry Siegel conceived her, Lois considers Clark Kent to be a wimp, but she is infatuated with the bold and mighty Superman, not knowing that Kent and Superman are the same person. Siegel objected to any proposal that Lois discover that Clark is Superman because he felt that, as implausible as Clark's disguise is, the love triangle was too important to the book's appeal.[162] However, Siegel wrote stories in which Lois suspects Clark is Superman and tries to prove it, with Superman always duping her in the end; the first such story was in Superman #17 (July–August 1942).[163][164] This was a common plot in comic book stories prior to the 1970s. In a story in Action Comics #484 (June 1978), Clark Kent admits to Lois that he is Superman, and they marry. This was the first story in which Superman and Lois marry that was not an "imaginary tale". Many Superman stories since then have depicted Superman and Lois as a married couple, but about as many depict them in the classic love triangle. In modern era comic books, Superman and Lois are a stable married couple, and the Superman supporting cast was further expanded with the introduction of their son, Jon Kent.

Other supporting characters include Jimmy Olsen, a photographer at the Daily Planet, who is friends with both Superman and Clark Kent, though in most stories he does not know that Clark is Superman. Jimmy is frequently described as "Superman's pal", and was conceived to give young male readers a relatable character through which they could fantasize being friends with Superman.

In the earliest comic book stories, Clark Kent's employer is George Taylor of The Daily Star, but the second episode of the radio serial changed this to Perry White of the Daily Planet.[165]

Clark Kent's foster parents are Jonathan and Martha Kent. In many stories, one or both of them have died by the time Clark becomes Superman. Clark's parents taught him that he should use his abilities for altruistic means, but that he should also find some way to safeguard his private life.

Antagonists

[edit]The villains Superman faced in the earliest stories were ordinary humans, such as gangsters, corrupt politicians, and violent husbands; but they soon grew more colorful and outlandish so as to avoid offending censors or scaring children. The mad scientist Ultra-Humanite, introduced in Action Comics #13 (June 1939), was Superman's first recurring villain. Superman's best-known nemesis, Lex Luthor, was introduced in Action Comics #23 (April 1940) and has been depicted as either a mad scientist or a wealthy businessman (sometimes both).[166] In 1944, the magical imp Mister Mxyzptlk, Superman's first recurring super-powered adversary, was introduced.[167] Superman's first alien villain, Brainiac, debuted in Action Comics #242 (July 1958). General Zod, who first appeared in Adventure Comics #283 (April 1961), is a fellow Kryptonian with similar powers. The monstrous Doomsday, introduced in Superman: The Man of Steel #17–18 (Nov.-Dec. 1992), was the first villain to evidently kill Superman in physical combat without exploiting Superman's critical weaknesses such as kryptonite.

Alternative depictions

[edit]The details of Superman's origin story and supporting cast vary across his large body of fiction released since 1938, but most versions conform to the basic template described above. A few stories feature radically altered versions of Superman. An example is the graphic novel Superman: Red Son, which depicts a communist Superman who rules the Soviet Union.[168] DC Comics has on some occasions published crossover stories where different versions of Superman interact with each other using the plot device of parallel universes. For instance, in the 1960s, the Superman of "Earth-One" would occasionally feature in stories alongside the Superman of "Earth-Two", the latter of whom resembled Superman as he was portrayed in the 1940s.[169]

Impact and legacy

[edit]The superhero archetype

[edit]Superman is often considered the first superhero. This point can be debated: Ogon Bat, the Phantom, Zorro, and Mandrake the Magician arguably fit the definition of the superhero yet predate Superman. Nevertheless, Superman popularized this kind of character and established the conventions: a costume, a codename, extraordinary abilities, and an altruistic mission.[citation needed] Superman's success in 1938 begat a wave of imitations, which include Batman, Captain America, and Captain Marvel. This flourishing is today referred to as America's Golden Age of Comic Books, which lasted from 1938 to about 1950. The Golden Age ended when American superhero book sales declined, leading to the cancellation of many characters; but Superman was one of the few superhero franchises that survived this decline, and his sustained popularity into the late 1950s led to a revival in the Silver Age of Comic Books, when characters such as Spider-Man, Iron Man, and The X-Men were created.

After World War II, American superhero fiction entered Japanese culture. Astro Boy, first published in 1952, was inspired by Mighty Mouse, which in turn was a parody of Superman.[170] The Superman animated shorts from the 1940s were first broadcast on Japanese television in 1955, and they were followed in 1956 by the TV show Adventures of Superman starring George Reeves. These shows were popular with the Japanese and inspired Japan's own prolific genre of superheroes. The first Japanese superhero movie, Super Giant, was released in 1957. The first Japanese superhero TV show was Moonlight Mask in 1958. Other notable Japanese superheroes include Ultraman, Kamen Rider, and Sailor Moon.[171][172][173]

Fine art

[edit]Since the Pop Art period and the 1960s, the character of Superman has been "appropriated" by multiple visual artists and incorporated into contemporary artwork,[174][175] most notably by Andy Warhol,[176][177] Roy Lichtenstein,[178] Mel Ramos,[179] Dulce Pinzon,[180] Mr. Brainwash,[181] Raymond Pettibon,[182] Peter Saul,[183] Giuseppe Veneziano,[184] F. Lennox Campello,[185] and others.[181][186][187]

Literary analysis

[edit]Superman has been interpreted and discussed in many forms, with Umberto Eco noting that "he can be seen as the representative of all his similars".[188] Writing in Time in 1971, Gerald Clarke stated: "Superman's enormous popularity might be looked upon as signaling the beginning of the end for the Horatio Alger myth of the self-made man." Clarke viewed the comics characters as having to continuously update in order to maintain relevance and thus representing the mood of the nation. He regarded Superman's character in the early seventies as a comment on the modern world, which he saw as a place in which "only the man with superpowers can survive and prosper".[189] Andrew Arnold, writing in the early 21st century, has noted Superman's partial role in exploring assimilation, the character's alien status allowing the reader to explore attempts to fit in on a somewhat superficial level.

A.C. Grayling, writing in The Spectator, traces Superman's stances through the decades, from his 1930s campaign against crime being relevant to a nation under the influence of Al Capone, through the 1940s and World War II, a period in which Superman helped sell war bonds,[190] and into the 1950s, where Superman explored the new technological threats. Grayling notes the period after the Cold War as being one where "matters become merely personal: the task of pitting his brawn against the brains of Lex Luthor and Brainiac appeared to be independent of bigger questions", and discusses events post 9/11, stating that as a nation "caught between the terrifying George W. Bush and the terrorist Osama bin Laden, America is in earnest need of a Saviour for everything from the minor inconveniences to the major horrors of world catastrophe. And here he is, the down-home clean-cut boy in the blue tights and red cape".[191]

An influence on early Superman stories is the context of the Great Depression. Superman took on the role of social activist, fighting crooked businessmen and politicians and demolishing run-down tenements.[192] Comics scholar Roger Sabin sees this as a reflection of "the liberal idealism of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal", with Shuster and Siegel initially portraying Superman as champion to a variety of social causes.[193][194] In later Superman radio programs the character continued to take on such issues, tackling a version of the Ku Klux Klan in a 1946 broadcast, as well as combating anti-semitism and veteran discrimination.[195][196][197]

Scott Bukatman has discussed Superman, and the superhero in general, noting the ways in which they humanize large urban areas through their use of the space, especially in Superman's ability to soar over the large skyscrapers of Metropolis. He writes that the character "represented, in 1938, a kind of Corbusierian ideal. Superman has X-ray vision: walls become permeable, transparent. Through his benign, controlled authority, Superman renders the city open, modernist and democratic; he furthers a sense that Le Corbusier described in 1925, namely, that 'Everything is known to us'."[198]

Jules Feiffer has argued that Superman's real innovation lay in the creation of the Clark Kent persona, noting that what "made Superman extraordinary was his point of origin: Clark Kent." Feiffer develops the theme to establish Superman's popularity in simple wish fulfillment,[199] a point Siegel and Shuster themselves supported, Siegel commenting that "If you're interested in what made Superman what it is, here's one of the keys to what made it universally acceptable. Joe and I had certain inhibitions... which led to wish-fulfillment which we expressed through our interest in science fiction and our comic strip. That's where the dual-identity concept came from" and Shuster supporting that as being "why so many people could relate to it".[200]

Ian Gordon suggests that the many incarnations of Superman across media use nostalgia to link the character to an ideology of the American Way. He defines this ideology as a means of associating individualism, consumerism, and democracy and as something that took shape around WWII and underpinned the war effort. Superman, he notes was very much part of that effort.[201]

An allegory for immigrants

[edit]Superman's immigrant status is a key aspect of his appeal.[202][203][204] Aldo Regalado saw the character as pushing the boundaries of acceptance in America. The extraterrestrial origin was seen by Regalado as challenging the notion that Anglo-Saxon ancestry was the source of all might.[205] Gary Engle saw the "myth of Superman [asserting] with total confidence and a childlike innocence the value of the immigrant in American culture". He argues that Superman allowed the superhero genre to take over from the Western as the expression of immigrant sensibilities. Through the use of a dual identity, Superman allowed immigrants to identify with both of their cultures. Clark Kent represents the assimilated individual, allowing Superman to express the immigrants' cultural heritage for the greater good.[203] David Jenemann has offered a contrasting view. He argues that Superman's early stories portray a threat: "the possibility that the exile would overwhelm the country".[206] David Rooney, a theater critic for The New York Times, in his evaluation of the play Year Zero considers Superman to be the "quintessential immigrant story [...] [b]orn on an alien planet, he grows stronger on Earth, but maintains a secret identity tied to a homeland that continues to exert a powerful hold on him even as his every contact with those origins does him harm".[207] Junot Díaz argues that the character particularly resonates with the experiences of undocumented immigrants in the United States.[208] Throughout the depictions of Superman's archenemy Lex Luthor in comics, film, and television, Luthor has frequently expressed and exploited xenophobia against Superman.[209]

Religious themes

[edit]It is popularly believed that Superman took inspiration from Judaic mythology and there is some circumstantial evidence to support this. The British rabbi Simcha Weinstein notes that Superman's story has some parallels to that of Moses. For example, Moses as a baby was sent away by his parents in a reed basket to escape death and was adopted by a foreign culture. Weinstein also posits that Superman's Kryptonian name, "Kal-El", resembles the Hebrew phrase qōl ʾēl (קוֹל-אֵל) which can be taken to mean "Voice of God".[210] The historian Larry Tye suggests that this "Voice of God" is an allusion to Moses' role as a prophet.[211] The suffix "el", meaning "god", is also found in the name of angels (e.g. Gabriel, Ariel), who are airborne humanoid agents of good with superhuman powers. The Nazis also thought Superman was a Jew and in 1940 the Schutzstaffel (SS) newspaper Das Schwarze Korps denounced Superman and his creator Jerry Siegel.[212]

All that said, historians such as Martin Lund and Les Daniels argue that the evidence for Judaic influence in Siegel and Shuster's stories is merely circumstantial. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were not practicing Jews and never acknowledged the influence of Judaism in any memoir or interview.[213][214]

Superman stories have occasionally exhibited Christian themes as well. Screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz consciously made Superman an allegory for Jesus Christ in the 1978 movie starring Christopher Reeve: baby Kal-El's ship resembles the Star of Bethlehem, and Jor-El gives his son a messianic mission to lead humanity into a brighter future.[215] This messianic theme was revisited in the 2013 movie Man of Steel, wherein Jor-El asks Superman to redeem the Kryptonian race, which corrupted itself through eugenics, by guiding humanity down a wiser path.[216]

In other media

[edit]Radio

[edit]The first adaptation of Superman beyond comic books was a radio show, The Adventures of Superman, which ran from 1940 to 1951 for 2,088 episodes, most of which were aimed at children. The episodes were initially 15 minutes long, but after 1949 they were lengthened to 30 minutes. Most episodes were done live.[217] Bud Collyer was the voice actor for Superman in most episodes. The show was produced by Robert Maxwell and Allen Ducovny, who were employees of Superman, Inc. and Detective Comics, Inc. respectively.[218][219]

Stage

[edit]In 1966 Superman had a Tony-nominated musical play produced on Broadway. It's a Bird... It's a Plane... It's Superman featured music by Charles Strouse, lyrics by Lee Adams and book by David Newman and Robert Benton. Actor Bob Holiday performed as Clark Kent/Superman and actress Patricia Marand performed as Lois Lane.

Film

[edit]- Paramount Pictures released a series of Superman theatrical animated shorts between 1941 and 1943. Seventeen episodes in total were made, each 8–10 minutes long. The first nine films were produced by Fleischer Studios and the next films were produced by Famous Studios. Bud Collyer provided the voice of Superman. The first episode had a production budget of $50,000 with the remaining episodes at $30,000 each[220] (equivalent to $641,000 in 2024), which was exceptionally lavish for the time; $9,000 – $15,000 was more typical for animated shorts.[221] Joe Shuster provided model sheets for the characters, so the visuals resembled the contemporary comic book aesthetic.[222]

- The first live-action adaptation of Superman was a movie serial released in 1948, targeted at children. Kirk Alyn became the first actor to portray the hero onscreen. The production cost up to $325,000[223] (equivalent to $4,253,000 in 2024). It was the most profitable movie serial in movie history.[224] A sequel serial, Atom Man vs. Superman, was released in 1950. For flying scenes, Superman was hand-drawn in animated form, composited onto live-action footage.

- The first feature film was Superman and the Mole Men, a 58-minute B-movie released in 1951, produced on an estimated budget of $30,000 (equivalent to $363,000 in 2024).[225] It starred George Reeves as Superman, and was intended to promote the subsequent television series.[226]

- The first big-budget movie was Superman in 1978, starring Christopher Reeve and produced by Alexander and Ilya Salkind. It was 143 minutes long and was made on a budget of $55 million (equivalent to $265,000,000 in 2024). It is the most successful Superman feature film to date in terms of box office revenue adjusted for inflation.[227] The soundtrack was composed by John Williams and was nominated for an Academy Award.

The success of the 1978 film arguably paved the way for later big-budget superhero movies like Batman (1989) and Spider-Man (2002).[228][229][230]

- The 1978 film spawned three sequels: Superman II (1980), Superman III (1983), Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1987).

- In 2006, Superman Returns was released, designed after the 1978–1987 film series. Superman was portrayed by Brandon Routh, who later reprised his role in the Arrowverse crossover Crisis on Infinite Earths (2019–2020).

- Superman has appeared in a series of direct-to-video animated films produced by Warner Bros. Animation called DC Universe Animated Original Movies, beginning with Superman: Doomsday in 2007. Many of these movies are adaptations of popular comic book stories.

- Superman appeared in the theatrical animated feature film Teen Titans Go! To the Movies (2018), voiced by Nicolas Cage.

- Superman appeared in the theatrical animated feature film DC League of Super-Pets (2022), voiced by John Krasinski.

DC Extended Universe

[edit]- In 2013, Man of Steel was released by Warner Bros. as a reboot of the film series, starring Henry Cavill as Superman.

- A sequel, Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016), featured Superman alongside Batman and Wonder Woman, making it the first theatrical film in which Superman appeared alongside other superheroes from the DC Universe.

- Cavill reprised his role in Justice League (2017) and its director's cut (2021).

- This version of Superman also makes cameos in Shazam! (2019) and in the first season finale of the TV series Peacemaker (2022) but portrayed by stand-ins for Cavill.

- Cavill makes an uncredited cameo appearance as Superman in the mid-credits scene of the film Black Adam (2022).

- Nicolas Cage makes a cameo appearance as an alternate version of Superman in the film The Flash (2023), Cage shooting his scenes through volumetric capture, before he was deaged with computer-generated imagery (CGI).[231] Cavill, George Reeves, and Christopher Reeve also cameo as their respective versions of Superman through the use of CGI representing their likenesses, Cavill having filmed additional scenes as the character for the film which were removed during post-production.

DC Universe

[edit]- A new reboot of the film series, Superman, is set in the DC Universe (DCU) franchise. The film was written and directed by James Gunn and stars David Corenswet as Superman.

Television

[edit]

- Adventures of Superman, which aired from 1952 to 1958, was the first television series based on a superhero. It starred George Reeves as Superman. Whereas the radio serial was aimed at children, this television show was aimed at a general audience,[232][233] although children made up the majority of viewers. Robert Maxwell, who produced the radio serial, was the producer for the first season. For the second season, Maxwell was replaced with Whitney Ellsworth. Ellsworth toned down the violence of the show to make it more suitable for children, though he still aimed for a general audience. This show was extremely popular in Japan, where it achieved an audience share rating of 74.2% in 1958.[234]

- His first animated television series was The New Adventures of Superman, which aired from 1966 to 1970. The show also feature a seven-minute part focused on Superboy named The Adventures of Superboy.

- Starting in 1974, Superman was one of the leading characters in the Hanna-Barbera-produced animated series Super Friends and all its sequels until 1986.

- To celebrate his 50th anniversary, Ruby Spears produced an animated series partially based on Superman (1978) and post-Crisis Superman comics created by John Byrne. The model sheets for Superman (1988) were drawn by legendary comics artist Gil Kane and most of the episodes were written by comics writer Marv Wolfman.

- Superboy aired from 1988 to 1992. It was produced by Alexander and Ilya Salkind, the same men who had produced the Superman films starring Christopher Reeve.

- Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman aired from 1993 to 1997. This show was aimed at adults and focused on the relationship between Clark Kent and Lois Lane as much as Superman's heroics.[226] Dean Cain played Superman, and Teri Hatcher played Lois.

- Smallville aired from 2001 to 2011. The show was targeted at young adults.[235][236] Played by Tom Welling, the series covered Clark Kent's life prior to becoming Superman, spanning ten years from his high school years in Smallville to his early life in Metropolis. Although Clark engages in heroics, he does not wear a costume, nor does he call himself Superboy. Rather, he relies on misdirection and his blinding speed to avoid being recognized. Later seasons find him becoming a public hero called the Red-Blue Blur, eventually shortened to the Blur, in a proto-Justice League before taking on the mantle of Superman.

- Superman: The Animated Series (with the voice of Tim Daly as the adult character) aired from 1996 to 2000. After the show's conclusion, this version of Superman appeared in the sequel shows Batman Beyond (voiced by Christopher McDonald) aired from 1999 to 2001 and Justice League and Justice League Unlimited (voiced by George Newbern), which ran from 2001 to 2006. All of these shows were produced by Bruce Timm. This was the most successful and longest-running animated version of Superman.[226]

- In the Arrowverse, Earth-38 Superman (played by Tyler Hoechlin), appears as a special guest star in several television series: Supergirl, The Flash, Arrow and Legends of Tomorrow.

- Hoechlin also played his Arrowverse doppelgänger on Superman & Lois that is set outside of Earth-Prime.

- Superman appears as an ensemble character in the animated show Justice League Action. He also appears as a guest character in other animated shows such as Batman: The Brave and the Bold and Harley Quinn.

- The 2023 animated series My Adventures with Superman depicts a young Superman (played by Jack Quaid) at the start of his career, through the eyes of a reimagined Lois Lane, with elements of romantic comedy alongside the standard action-adventure and science fiction tropes.

Video games

[edit]- The first electronic game was simply titled Superman, and released in 1979 for the Atari 2600.

- The last game fully centered on Superman was the adaptation of Superman Returns in 2006.

- From 2006 to present, Superman appeared in a co-starring role, such as the Injustice game series (2013–present).

Merchandising

[edit]DC Comics trademarked the Superman chest logo in August 1938.[237] Jack Liebowitz established Superman, Inc. in October 1939 to develop the franchise beyond the comic books.[52] Superman, Inc. merged with DC Comics in October 1946.[238] After DC Comics merged with Warner Communications in 1967, licensing for Superman was handled by the Licensing Corporation of America.[239]

The Licensing Letter (an American market research firm) estimated that Superman licensed merchandise made $634 million in sales globally in 2018 (43.3% of this revenue came from the North American market). For comparison, in the same year, Spider-Man merchandise made $1.075 billion and Star Wars merchandise made $1.923 billion globally.[240]

The earliest paraphernalia appeared in 1939: a button proclaiming membership in the Supermen of America club. The first toy was a wooden doll in 1939 made by the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company.[241] Superman #5 (May 1940) carried an advertisement for a "Krypto-Raygun", which was a gun-shaped device that could project images on a wall.[242] The majority of Superman merchandise is targeted at children, but since the 1970s, adults have been increasingly targeted because the comic book readership has gotten older.[243]

During World War II, Superman was used to support the war effort. Action Comics and Superman carried messages urging readers to buy war bonds and participate in scrap drives.[244] Other superheroes became patriots who went to fight: Batman, Wonder Woman and Captain America.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Consolidated Book Publishers was also known as Humor Publishing. Jerry Siegel always referred to this publisher as "Consolidated" in all interviews and memoirs. Humor Publishing was possibly a subsidiary of Consolidated.

- ^ National Allied Publications was founded in 1934 by Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson. Due to financial difficulties, Wheeler-Nicholson formed a corporation with Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz called Detective Comics, Inc. In January 1938, Wheeler-Nicholson sold his stake in National Allied Publications and Detective Comics to Donenfeld and Liebowitz as part of a bankruptcy settlement. On September 30, 1946, these two companies merged to become National Comics Publications. In 1961, the company changed its name to National Periodical Publications. In 1967 National Periodical Publications was purchased by Kinney National Company, which later purchased Warner Bros.-Seven Arts and became Warner Communications. In 1976, National Periodical Publications changed its name to DC Comics, which had been its nickname since 1940. Since 1940, the publisher had placed a logo with the initials "DC" on all its magazine covers, and consequently "DC Comics" became an informal name for the publisher.

- ^ See USC Title 17, Chapter 3, § 304(b) and § 305. Because the copyright to Action Comics #1 was in its renewal term on October 27, 1998 (the date the Copyright Term Extension Act became effective), its copyright will expire 95 years after first publication and at the end of the calendar year.

- ^ See Copyright Act of 1909 § 20

References

[edit]- ^ a b c The copyright date of Action Comics #1 was registered as April 18, 1938.

See Catalog of Copyright Entries. New Series, Volume 33, Part 2: Periodicals January–December 1938. United States Library of Congress. 1938. p. 129. - ^ a b Dallas et al. (2013), American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1980s, p. 208

- ^ "Best-selling comic books of all time". Statista. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Ricca (2014) Super Boys

- ^ Jerry Siegel (under the pseudonym Herbert S. Fine). "The Reign of the Superman". Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization #3. January 1933

Summarized in Ricca 2014, pp. 70–72 Super Boys - ^ Jerry Siegel, quoted in Daniels (1998). Superman: The Complete History, p. 15: "When we presented different strips to the syndicate editors, they would say, 'Well, this isn't sensational enough.' So I thought, I'm going to come up with something so wild they won't be able to say that."

- ^ Jerry Siegel. Creation of a Superhero (unpublished memoir, written c.1978; Scans available from Dropbox and Scribd[permanent dead link]).:

"...one of the things which spurred me into creating a "Superman" strip was something a syndicate editor said to me after I had been submitting various proposed comic strips to him. He said, "The trouble with your stuff is that it isn't spectacular enough. You've got to come up with something sensational! Something more terrific than the other adventure strips on the market!"" - ^ Tye (2012), Superman, p. 17: "The version he was drafting would again begin with a wild scientist empowering a normal human against his will, but this time the powers would be even more fantastic, and rather than becoming a criminal, the super-being would fight crime 'with the fury of an outraged avenger'."

- ^ Jerry Siegel. Creation of a Superhero (unpublished memoir, c. 1978; Scans available from Dropbox and Scribd[permanent dead link]).:

p. 30: "The hero of 'THE SUPERMAN' comic book strip was also given super-powers against his will by a scientist. He gained fantastic strength, bullets bounced off him, etc. He fought crime with the fury of an outraged avenger."

50: "What, I thought, could be more sensational than a Superman who could fly through the air, who was impervious to flames, bullets, and a mob of enraged amok adversaries?" - ^ Siegel in Andrae (1983), p. 10: "Obviously, having him a hero would be infinitely more commercial than having him a villain. I understand that the comic strip Dr. Fu Manchu ran into all sorts of difficulties because the main character was a villain. And with the example before us of Tarzan and other action heroes of fiction who were very successful, mainly because people admired them and looked up to them, it seemed the sensible thing to do to make The Superman a hero. The first piece was a short story, and that's one thing, but creating a successful comic strip with a character you'll hope will continue for many years, it would definitely be going in the wrong direction to make him a villain."

- ^ Daniels (1998). Superman: The Complete History, p. 17: "... usually [Shuster] and Siegel agreed that no special costume was in evidence, and the surviving artwork bears them out."

- ^ Siegel and Shuster in Andrae (1983), p.9-10: "Shuster: [...] It wasn't really Superman: that was before he evolved into a costumed figure. He was simply wearing a T-shirt and pants; he was more like Slam Bradley than anything else — just a man of action. [...]

Siegel: In later years – maybe 10 or 15 years ago – I asked Joe what he remembered of this story, and he remembered a scene of a character crouched on the edge of a building, with a cape almost a la Batman. We don't specifically recall if the character had a costume or not. [...] Joe and I – especially Joe – seem to recall that there were some scenes in there in which that character had a bat-like cape." - ^ Daniels (1998). Superman: The Complete History, p. 17

- ^ The copyright date of Detective Dan Secret Operative 48 was registered as May 12, 1933.

See Catalog of Copyright Entries. New Series, Volume 30, For the Year 1933, Part 1: Books, Group 2. United States Library of Congress. 1933. p. 351. - ^ Scivally (2007). Superman on Film, Television, Radio and Broadway, p. 6: "Detective Dan—Secret Operative 48 was published by the Humor Publishing Company of Chicago. Detective Dan was little more than a Dick Tracy clone, but here, for the first time, in a series of black-and-white illustrations, was a comic magazine with an original character appearing in all-new stories. This was a dramatic departure from other comic magazines, which simply reprinted panels from the Sunday newspaper comic strips."

- ^ Jerry Siegel. Creation of a Superhero (unpublished memoir, written c.1978; Scans available from Dropbox and Scribd[permanent dead link]):

"I do recall, though, that when Mr. Livingston visited Cleveland, Joe and I showed THE SUPERMAN comic book pages to Mr. Livingston in his hotel room, and he was favorably impressed." - ^ Beerbohm, Robert (1996). "Siegel & Shuster Presents... The Superman". Comic Book Marketplace. No. 36. Gemstone Publishing Inc. pp. 47–50.:

"So this early Superman cover was done, replete with a "10¢" plug... and was placed on an entire comic book, written, drawn, inked, and shown to the Humor people by Jerry and Joe when they happened to come through Cleveland (trying to shop Detective Dan to the NEA newspaper syndicate)." - ^ Ricca 2014, pp. 97–98 Super Boys

- ^ Tye (2012), Superman, p. 17: "Although the first response was encouraging, the second made it clear that the comic book was so unprofitable that its publishers put on hold any future stories."