Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Khitan large script

View on Wikipedia| Khitan large script | |

|---|---|

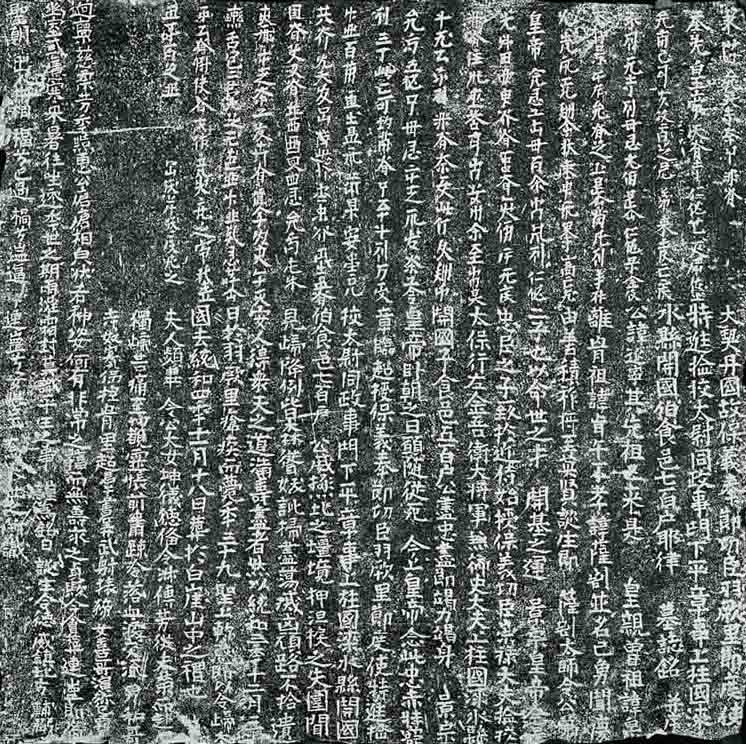

Memorial for Yelü Yanning dated 986 | |

| Script type | |

| Direction | Top-to-bottom and right-to-left |

| Languages | Khitan language |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Oracle bone script

|

Child systems | Jurchen script |

Sister systems | Simplified Chinese, Tangut script, Kanji, Hanja, Chữ Hán, Zhuyin |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Kitl (505), Khitan large script |

The Khitan large script (Chinese: 契丹大字; pinyin: qìdān dàzì) was one of two writing systems used for the now-extinct Khitan language (the other was the Khitan small script). It was used during the 10th–12th centuries by the Khitan people, who had created the Liao Empire in north-eastern China. In addition to the large script, the Khitans simultaneously also used a functionally independent writing system known as the Khitan small script. Both Khitan scripts continued to be in use to some extent by the Jurchens for several decades after the fall of the Liao dynasty, until the Jurchens fully switched to a script of their own. Examples of the scripts appeared most often on epitaphs and monuments, although other fragments sometimes surface.

History

[edit]Abaoji of the Yelü clan, founder of the Khitan, or Liao, dynasty, introduced the original Khitan script in 920 CE.[1] The "large script", or "big characters" (大字), as it was referred to in some Chinese sources, was established to keep the record of the new Khitan state. The Khitan script was based on the idea of the Chinese script.[2]

Description

[edit]The Khitan large script was considered to be relatively simple. The large script characters were written equally spaced, in vertical columns, in the same way as the Chinese has been traditionally written. Although the large script mostly uses logograms, it is possible that ideograms and syllabograms are used for grammatical functions. The large script has a few similarities to Chinese, with several words taken directly with or without modifications from the Chinese (e.g. characters 二, 三, 十, 廿, 月, and 日, which appear in dates in the apparently bilingual Xiao Xiaozhong muzhi inscription from Xigushan, Jinxi, Liaoning Province).[3] Most large script characters, however, cannot be directly related to any Chinese characters. The meaning of most of them remains unknown, but that of a few of them (numbers, symbols for some of the five elements and the twelve animals that the Khitans apparently used to designate years of the sexagenary cycle) has been established by analyzing dates in Khitan inscriptions.[4]

While there has long been controversy as to whether a particular monument belong to the large or small script,[5] there are several monuments (steles or fragments of stelae) that the specialists at least tentatively identify as written in the Khitan large script. However, one of the first inscriptions so identified (the Gu taishi mingshi ji epitaph, found in 1935) has been since lost, and the preserved rubbings of it are not very legible; moreover, some believe that this inscription was a forgery in the first place. In any event, the total of about 830 different large-script characters are thought to have been identified, even without the problematic Gu taishi mingshi ji; including it, the character count rises to about 1000.[6] The Memorial for Yelü Yanning (dated 986 CE) is one of the earliest inscriptions in the Khitan large script.

Direction

[edit]While the Khitan large script was traditionally written top-to-bottom, it can also be written left-to-right, which is the direction to be expected in modern contexts for the Khitan large script and other traditionally top-to-bottom scripts, especially in electronic text.

Jurchen

[edit]Some of the characters of the Jurchen scripts have similarities to the Khitan large script. According to some sources, the discoveries of inscriptions on monuments and epitaphs give clues to the connection between Khitan and Jurchen.[7] After the fall of the Liao dynasty, the Khitan (small-character) script continued to be used by the Jurchen people for a few decades, until it was fully replaced with the Jurchen script and, in 1191, suppressed by imperial order.[8][9]

Corpus

[edit]

There are no surviving examples of printed texts in the Khitan language, and aside from five example Khitan large characters with Chinese glosses in a book on calligraphy written by Tao Zongyi (陶宗儀) during the mid 14th century, there are no Chinese glossaries or dictionaries of Khitan. However, in 2002 a small fragment of a Khitan manuscript with seven Khitan large characters and interlinear glosses in Old Uyghur was identified in the collection of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.[10] Then, in 2010 a manuscript codex (Nova N 176) held at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg was identified by Viacheslav Zaytsev as being written in the Khitan large script.[11]

The main source of Khitan texts are monumental inscriptions, mostly comprising memorial tablets buried in the tombs of Khitan nobility.[12] There are about 17 known monuments with inscriptions in the Khitan large script, ranging in date from 986 to 1176.

In addition to monumental inscriptions, short inscriptions in both Khitan scripts have also been found on tomb murals and rock paintings, and on various portable artefacts such as mirrors, amulets, paiza (tablets of authority given to officials and envoys), and special non-circulation coins. A number of bronze official seals with the seal face inscribed in a convoluted seal script style of Khitan characters are also known.

References

[edit]- ^ Gernet (1996), p. 353.

- ^ Gernet (1996), p. 34.

- ^ Kane (1989), p. 12.

- ^ Kane (1989), p. 11-13.

- ^ Kane (1989), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Kane (1989), pp. 6, 12.

- ^ Kiyose, Gisaburo N. (1985), "The Significance of the New Kitan and Jurchen Materials", Papers in East Asian Languages, pp. 75–87

- ^ Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (1996), The World's Writing Systems, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 230–234

- ^ Gernet (1996), p. 359.

- ^ Wang, Ding (2004). "Ch 3586 — ein khitanisches Fragment mit uigurischen Glossen in der Berliner Turfansammlung" (PDF). In Durkin-Meisterernst, Desmond; Raschmann, Simone-Christiane; Wilkens, Jens; Yaldiz, Marianne; Zieme, Peter (eds.). Turfan Revisited: The First Century of Research into the Arts and Cultures of the Silk Road. Dietrich Reimer Verlag. pp. 371–379. ISBN 978-3-496-02763-8. Archived from the original on 15 September 2025. Retrieved 15 September 2025.

- ^ O. A. Vodneva (О. А. Воднева) (2 June 2011). Отчет о ежегодной научной сессии ИВР РАН – 2010 [Report on the annual scientific session of the IOM – 2010] (in Russian). Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ Kane (2009), p. 4.

- Works cited

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Kane, Daniel (1989). "Khitan script". The Sino-Jurchen Vocabulary of the Bureau of Interpreters. Uralic and Altaic Series. Vol. 153. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. pp. 11–20. ISBN 0-933070-23-3.

- Kane, Daniel (2009). The Kitan Language and Script. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16829-9.

Further reading

[edit]- West, Andrew (8 June 2023) [16 October 2012]. "Khitan Seals". BabelStone Blog. Archived from the original on 21 July 2025. Retrieved 15 September 2025. Analysis of 25 Khitan large script seals, many of which are in the nine-fold seal script style.

- Shimunek, Andrew (2022). "Toward a morphological paradigm of the Kitan verb 'to give' in assembled script and linear script, with notes on Mongolic cognates". 알타이학보 [Altai Journal]. 32: 71–98. doi:10.15816/ask.2022..32.005. Glossed sentences in Khitan large ("linear") and small ("assembled") script.

- Bai, Yuanming (2022). "A Study on the Verb 'to marry' in Khitan Scripts" (PDF). Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 75 (4): 639–654. doi:10.1556/062.2022.00263. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2025. Retrieved 15 September 2025. Variants and inflections of the verb "to marry" in Khitan small and large script with proposed character readings.

- Wu, Yingzhe; Jiruhe; Peng, Daruhan (2017). "Interpretation of the epitaph of Changgun Yelü Zhun of Great Liao in Khitan large script" (PDF). Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 70 (2): 217–251. doi:10.1556/062.2017.70.2.5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2025. Retrieved 15 September 2025. Analysis of a Khitan epitaph with lists of Khitan large-small script correspondences, variants, semantic and phonetic readings.

- Liu Fengzhu 刘凤翥 (2014). Qìdān wénzì yánjiū lèibiān 契丹文字研究类编 [Collection of Research on the Khitan scripts] (in Chinese). Vol. 1–4. China Social Science Publishers 中国社会科学出版社.

- Liu Fengzhu 劉鳳翥; Wang Yunlong 王雲龍 (2004). "Qìdān dàzì "Yēlǜ Chāngyǔn mùzhìmíng" zhī yánjiū" 契丹大字《耶律昌允墓誌銘》之研究 [A study on the Epitaph for Yelü Changyun in Khitan large script]. 燕京學報 [Yenching Journal of Chinese Studies] (in Chinese). 17: 61–99. Analysis of a Khitan epitaph with a list of 189 Khitan large script characters, not including variants, with phonetic readings.

- Liu Fengzhu 劉鳳翥 (1998). "Qìdān dàzì liùshí nián zhī yánjiū" 契丹大字六十年之研究 [Sixty years of research on the Khitan large script] (PDF). 中國文化研究所學報 [Journal of Chinese Studies] (in Chinese). 7: 313–338. doi:10.29708/JCS.CUHK.199801_(7).0014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2025. Retrieved 15 September 2025. Contains copies of 6 Khitan large script texts with Chinese glosses and accompanying Chinese texts where available.